1. Introduction

Chronic pain is a complex condition characterized by a dynamic interplay among neuronal, immune, and vascular systems [

1,

2]. Affecting a substantial portion of the global population, its prevalence is increasing in parallel with global aging, posing significant therapeutic challenges and adversely impacting quality of life [

3]. Beyond peripheral and central sensitization, chronic pain is sustained by maladaptive synaptic remodelling, including long-term potentiation in the spinal dorsal horn [

4], structural reorganization of limbic circuits [

5], and prolonged glial neuroinflammation mediated by Interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β), Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha (TNF-α), and chemokines that amplify nociceptive signalling [

6].

Modern perspectives on chronic pain emphasize profound plastic reorganization at both functional and structural levels within the peripheral and central nervous systems [

7]. This maladaptive plasticity underpins the shift from acute nociception—a protective physiological mechanism—to chronic pain, a pathological condition [

1]. Central sensitization, a form of synaptic plasticity, drives this transition by enhancing excitability and response of nociceptive pathways in the spinal cord and supraspinal structures [

8]. Clinically, this manifests as allodynia and hyperalgesia, symptoms closely linked to neuroinflammation [

8,

9].

Neuroinflammation is orchestrated by glial cells—primarily microglia and astrocytes—which, upon activation by persistent nociceptive input or injury, release pro-inflammatory mediators, neurotransmitters, and neuromodulators [

10]. These molecules influence synaptic transmission and perpetuate the chronic pain state [

9,

11]. Notably, the emotional and cognitive dimensions of chronic pain, such as anxiety and depression, are associated with maladaptive plasticity in areas like the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), amygdala, and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) [

9,

12]. Mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and epigenetic alterations in nociceptors further sensitize pain pathways, while microvascular changes facilitate immune cell infiltration [

8].

Conventional pharmacological strategies—including opioids, NSAIDs, and anticonvulsants—often provide incomplete and unsustainable relief, and are burdened by adverse effects: opioids pose a high risk of addiction, NSAIDs cause gastrointestinal toxicity with prolonged use, and anticonvulsants may induce sedation and cognitive impairment [

13,

14].

In this context, phytochemicals—bioactive plant-derived compounds—are emerging as promising modulators of pain signalling [

15]. Belonging to diverse chemical classes such as flavonoids, terpenoids, and alkaloids, these compounds, though non-essential for plant growth, play key ecological roles and exhibit extensive pharmacological activity [

16].

Preclinical studies demonstrate that various phytochemicals can modulate neuronal excitability via interaction with ion channels critical to pain signalling (Nav, Cav, Kv, TRPV1) [

17,

18] and can inhibit inflammatory pathways by targeting enzymes like COX-2, modulating glial responses, and can influence transcription factors such as NF-κB [

19]. Agents such as curcumin, resveratrol, and capsaicin have shown analgesic potential through cytokine modulation, oxidative stress reduction, and direct receptor interactions [

15].

Among phytochemicals, those derived from Cannabis sativa are of growing relevance to pain management. The plant contains over 500 compounds, notably cannabinoids (e.g., THC, CBD) and a wide range of terpenes [

20,

21]. Cannabinoids, especially via CB1 and CB2 receptors, exert analgesic effects, but THC-related side effects limit their use [

22]. Terpenes, responsible for the plant’s aroma, are increasingly recognized for their pharmacological activity and potential to enhance cannabinoid effects through the so-called “entourage effect” [

23,

24].

Notably, terpenes may also act independently of cannabinoids, targeting distinct molecular pathways involved in nociception and neuroinflammation. Mounting evidence suggests they possess pleiotropic mechanisms of action, potentially contributing autonomously or synergistically to analgesia [

21].

This review critically examines the scientific literature on the role of Cannabis sativa terpenes in nociceptive modulation, with an emphasis on chronic pain syndromes. Its aims are to: identify the most prevalent terpenes and their pharmacodynamics; evaluate preclinical efficacy in chronic pain models; explore molecular mechanisms including cannabinoid-independent pathways; assess therapeutic profiles, safety, and pharmacokinetics; highlight research gaps; and propose directions for future investigation.

2. Phytochemical Modulation of Nociception: General Mechanisms

The use of phytochemicals as modulators of pain sensitivity rests on their ability to interfere with the complex network of molecular components involved in nociceptive transmission and neuroinflammation. These plant-derived compounds act concertedly on voltage-gated ion channels, transient receptor potential (TRP) receptors, regulatory pathways of pro-inflammatory transcription factors, and, not least, targets within the endocannabinoid system, outlining a multi-target profile that transcends the conventional pharmacological approach [

25].

Pre-clinical evidence in recent years has confirmed that flavonoids such as quercetin and myricetin directly inhibit Nav1.7 and Nav1.8 sodium channels and L-type Cav channels. Quercetin binds with high affinity to the voltage-sensor domains of Nav channels, dose-dependently reducing sodium currents while simultaneously suppressing COX-2 expression, thereby lowering prostaglandin synthesis and attenuating peripheral sensitization [

17]. Simultaneously, myricetin inhibits p38 MAPK phosphorylation and PKC-dependent signalling, limiting glutamate release in the spinal dorsal horn and normalising aberrant neuronal excitability levels, as demonstrated in murine models of peripheral neuropathy [

26].

Modulation of TRP receptors constitutes another mechanism through which phytochemicals exert antinociceptive effects [

27]. Limonene, a monoterpene commonly found in citrus fruits, acts as an antagonist at TRPV1 [

28] and TRPA1 [

29], reducing sensitivity to thermal and mechanical stimuli. In addition, limonene allosterically enhances the opening of GABAA channels [

30,

31], increasing neuronal inhibition and helping to suppress allodynia and hyperalgesia in formalin and hot-plate tests, with results comparable to some NSAIDs [

32].

Regarding inflammation, phytochemicals focus on COX-2 inhibition and attenuation of NF-κB signalling. These compounds hinder IκBα phosphorylation, preventing its degradation and the subsequent nuclear translocation of NF-κB, resulting in decreased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [

33]. In primary microglial and astrocyte cultures, flavonoid-enriched extracts reduce the up-regulation of activation markers such as CD11b and Iba-1, suggesting a protective effect against the chronic pro-inflammatory state typical of neuropathies [

34].

The endocannabinoid system provides an additional axis of modulation: BCP acts as a selective CB2 agonist and inhibits the enzyme MAGL, leading to increased 2-AG levels and reduced inflammatory and neuropathic pain responses [

35]. Complementary analyses have also shown that other terpenes, such as linalool and β-myrcene, modulate A

2A receptors and interact with serotonin transport, further expanding their analgesic potential [

36,

37].

Beyond their effects as monotherapies, co-administration of phytochemicals with standard analgesics has revealed significant therapeutic synergies. For example, the combination ofBCP oxide and paracetamol, tested in animal models, improves antinociceptive efficacy compared with either compound alone and mitigates the gastrointestinal side effects typical of NSAIDs, outlining a more favourable safety profile and opening avenues for combination-drug approaches [

38]. Pre-clinical and clinical studies on standardized mixtures of terpenes extracted from Cannabis sativa, administered orally, have shown efficacy comparable to morphine in controlling neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia, with good tolerability and low dependence potential [

39]. These results justify the initiation of randomized controlled clinical trials to validate therapeutic protocols based on highly pure, high-concentration phytochemical extracts.

3. Cannabis Terpenes: Prevalence and Pharmacological Properties

Terpenes are volatile isoprenoid compounds found in many plants—including

Cannabis sativa L.—and are responsible for their distinctive aromas. Recent scientific interest has focused on their possible role in cannabis’s medicinal properties, particularly their potential to modulate analgesia and contribute to the “entourage effect” alongside THC and CBD [

40]. Over 100 terpenes have been identified in

Cannabis, with profiles varying according to cultivar (chemovar), plant genetics, environmental conditions, and curing processes [

41]. Generally, monoterpenes predominate in “sativa” varieties, while “indica” types are richer in earthy sesquiterpenes [

42]. Terpene content in dried female inflorescences averages around 1% by weight, though highly aromatic chemovars can reach up to 3% [

43].

The terpenes most abundantly represented in

Cannabis are myrcene, limonene, pinene (α and β isomers), linalool, BCP, humulene, and terpinolene. Chemical-analytical studies show that myrcene can constitute up to 40–65% of a cultivar’s total terpene content, typically corresponding to concentrations of about 0.3–0.8%, while BCP—also ubiquitous and abundant—is often present at 0.1–0.5% [

44]. Other monoterpenes such as limonene, pinene, and linalool, and the sesquiterpene α-humulene, vary more widely according to the chemovar [

45].

Several cannabis terpenes exhibit antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activity in pre-clinical models through heterogeneous yet complementary mechanisms. BCP stands out for its “cannabinoid-like” action, selectively activating CB₂ receptors. Monoterpenes such as myrcene, linalool, and limonene act on central and peripheral targets—including opioid, α₂-adrenergic, and cholinergic receptors, TRP channels, and serotonergic pathways—thereby modulating pain perception and inflammation [

40]. Evidence from neuropathic animal models shows that cannabis-like terpene mixtures can match the analgesic efficacy of standard doses of morphine or synthetic cannabinoids without inducing typical side effects (i.e., no reward/addiction behaviour in conditioned place preference tests) [

46].

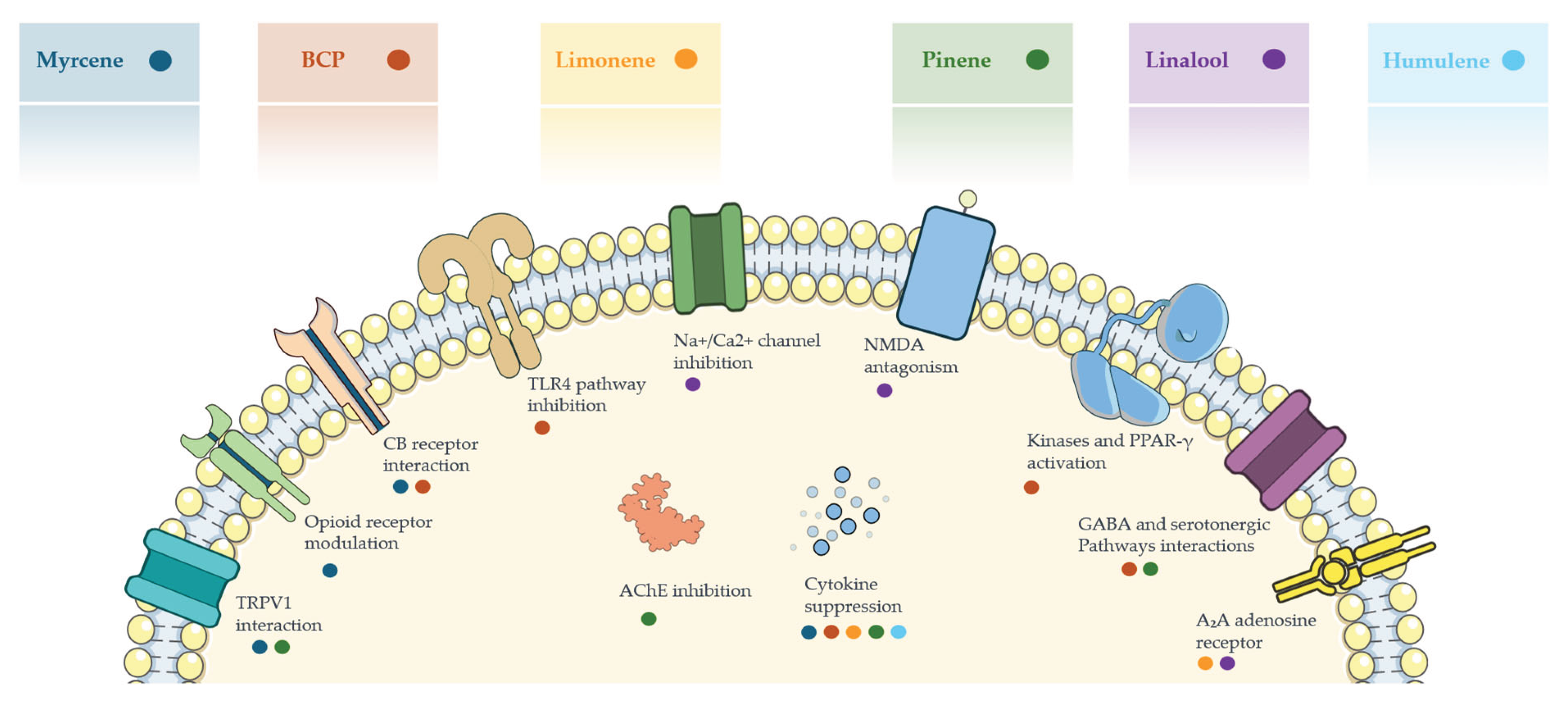

Figure 1 summarizes the principal mechanisms of action through which major cannabis-derived terpenes modulate nociception.

Figure 1.

Illustration summarizing the main molecular targets and mechanisms of action of selected cannabis-derived terpenes involved in analgesic and anti-inflammatory pathways. Each colored dot corresponds to a specific terpene and its associated interaction or effect on cellular signaling pathways. Abbreviations: BCP: β-Caryophyllene, TRPV1: Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1, CB: Cannabinoid, TLR4: Toll-Like Receptor 4, Na⁺/Ca²⁺: Sodium/Calcium channels, NMDA: N-Methyl-D-Aspartate receptor, AChE: Acetylcholinesterase, PPAR-γ: Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor gamma, GABA: Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid, A₂A: Adenosine receptor subtype A2A.

Figure 1.

Illustration summarizing the main molecular targets and mechanisms of action of selected cannabis-derived terpenes involved in analgesic and anti-inflammatory pathways. Each colored dot corresponds to a specific terpene and its associated interaction or effect on cellular signaling pathways. Abbreviations: BCP: β-Caryophyllene, TRPV1: Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1, CB: Cannabinoid, TLR4: Toll-Like Receptor 4, Na⁺/Ca²⁺: Sodium/Calcium channels, NMDA: N-Methyl-D-Aspartate receptor, AChE: Acetylcholinesterase, PPAR-γ: Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor gamma, GABA: Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid, A₂A: Adenosine receptor subtype A2A.

3.1. Myrcene

Myrcene is an acyclic monoterpene (C₁₀H₁₆) and one of the most abundant terpenes in cannabis—especially in indica-dominant chemovars. It lends an earthy, musky aroma (it is also found in hops, lemongrass, and mangoes). In many modern cannabis varieties, myrcene accounts for > 20 % of the total terpene fraction. Typical dried-flower levels range from roughly 0.1 % to 0.5 % w/w, although highly aromatic cultivars can reach ~1–2 %; in extreme cases, myrcene has been reported to make up as much as ~65 % of the total terpene profile.

The analgesic mechanisms of myrcene are not fully clarified, but several hypotheses have been proposed. A striking finding is that myrcene can act on TRP ion channels: Jansen et al. showed that micromolar concentrations of myrcene activated the TRPV1 (vanilloid) channel in rat cells, causing a Ca²⁺ influx—an effect blocked by the TRPV1 antagonist capsazepine [

47]. However, a subsequent study by Heblinski et al. failed to reproduce myrcene-induced TRPV1 activation in human TRPV1-expressing cells [

48], so the data on the TRP ion channels remain species or context-specific.

Beyond TRP channels, myrcene appears to engage opioid pathways: in several rodent studies, naloxone partially reversed the antinociceptive effect of myrcene, implicating endogenous opioid receptors. Early work noted that myrcene’s analgesia resembles that of peripheral opioids (without central side effects) and might be mediated by endogenous opioid release or indirect modulation of opioid receptors [

49].

Myrcene also exerts anti-inflammatory effects, relieving pain indirectly, by inhibiting inflammatory hyperalgesia driven by prostaglandin E₂ and other mediators. While myrcene seems to act chiefly through non-cannabinoid routes, [

50] it has been shown to interact with local cannabinoid receptors (likely CB₂) in murine models of joint inflammation, reducing pain and swelling, though without synergy with CBD [

51]. Overall, myrcene’s analgesic action probably involves a combination of peripheral opioid-receptor engagement, reduction of inflammatory sensitization, and possibly TRPV1 modulation, although its precise molecular targets remain undefined.

Clarifying these mechanisms is particularly important given the prevalence of myrcene in cannabis chemovars and its potential to modulate multiple pain-related pathways. A deeper understanding could support its rational use in therapeutic formulations for chronic pain, where multifactorial modulation is often required.

Myrcene is popularly believed to produce sedative and anxiolytic effects (the so-called “couch-lock” associated with high-myrcene cannabis [

52]). Controlled studies are scarce, but one mouse study found that myrcene produced anxiolysis with marked sexual dimorphism [

53]. The putative anxiolysis may stem from its sedative action or mild muscle-relaxant effect. To date there are no direct human data on myrcene’s anxiolytic or antidepressant effects. Nevertheless, because chronic pain often co-exists with anxiety and poor sleep, the sedative–anxiolytic properties observed in animals could be clinically relevant for pain patients who are anxious and have difficulty sleeping.

3.2. β-Caryophyllene

BCP is a bicyclic sesquiterpene (C₁₅H₂₄) with a spicy, peppery aroma, found in high concentrations in black pepper and cloves. In cannabis, BCP is often one of the dominant sesquiterpenes. It is detected in most sampled chemovars, although—compared with monoterpenes—it generally makes up a smaller share of the total terpene content [

54]. Many medicinal cannabis varieties contain 0.1 – 0.5 % BCP by weight, and in some (especially certain CBD-rich chemovars) it can be the primary terpene.

BCP engages numerous molecular targets and receptors, but it is best known as a selective agonist of the CB₂ cannabinoid receptor [

55]. BCP can also inhibit the TLR4 pathway and reduce the release of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α from activated microglia [

21,

56]. These immunomodulatory actions contribute to analgesia by dampening inflammation and neuro-inflammation along pain pathways.

Additional targets have been reported: BCP activates kinases (ERK1/2, JNK) and the nuclear receptor PPAR-γ, which is involved in metabolic and anti-inflammatory signalling [

57]. BCP-induced analgesia is likewise sensitive to opioid antagonists in some peripheral-pain assays, suggesting crosstalk with the opioid system. In one study, locally injected BCP attenuated capsaicin-evoked pain through combined CB₂ and peripheral-opioid mechanisms [

58].

Pre-clinical evidence for BCP as an analgesic and anti-inflammatory agent is robust, particularly in chronic-pain models. Rodent studies consistently show that systemic or local BCP reduces pain behaviours in diverse paradigms: inflammatory pain (formalin test, acetic-acid writhing), neuropathic pain (nerve injury or chemotherapy-induced), and visceral pain [

21]. Prophylactic BCP even prevented neuropathic-pain development in an antiviral-induced model [

59].

Beyond pain and inflammation, BCP has shown benefits in models of anxiety, spasms, seizures, depression, alcohol dependence, and Alzheimer’s disease [

60]. In an experimental study on mice, BCP produced anxiolytic, antidepressant, and anticonvulsant effects by modulating benzodiazepine/GABA

A receptors, serotonergic pathways, and the L-arginine/nitric-oxide pathway; its anxiolysis was abolished by flumazenil and bicuculline, while co-administration of L-arginine blunted all three effects, confirming a mechanism dependent on reduced nitric-oxide synthesis [

61].

These data broaden BCP’s pharmacological profile, suggesting clinical potential as a multisystem modulator of anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and epilepsy.

Human data, though still limited, are encouraging. In the musculoskeletal field, Farì et al. reported that 45 days of supplementation with hemp-seed oil enriched in BCP, myrcene, and ginger extract significantly reduced pain and improved functional scores in 38 patients with knee osteoarthritis versus an isocaloric terpene-free control [

62]. In gynaecology, Ou et al. (2012) showed that daily abdominal massage with an aromatherapy cream containing 2.7 % BCP shortened the duration and intensity of primary dysmenorrhoea in 48 women, outperforming a synthetic-fragrance placebo [

63]. In a placebo-controlled crossover study of 125 insomnia patients, Wang et al. found that a THC-free oral formulation composed of 300 mg CBD plus micro-doses (1 mg each) of eight terpenes, including BCP, increased deep-sleep proportion by an average of 1.3%, with gains of up to 48 minutes per night in participants with low baseline values and no adverse effects. These preliminary studies—coupled with BCP’s favourable safety profile—suggest that adding BCP to phytotherapeutic formulations may be a promising strategy for improving sleep quality and alleviating various forms of pain and anxiety, warranting larger-scale clinical trials.

3.3. Limonene

Limonene is a cyclic monoterpene (C₁₀H₁₆) with a strong citrus aroma, abundantly present in the peels of citrus fruits. In cannabis it is a common monoterpene, although its levels vary widely by cultivar. In a survey of North American cannabis, limonene ranked among the eight most prevalent terpenes and is often dominant in sativa-type chemovars [

64]. Typical limonene content in dried flowers is 0.1–0.3 %, but it can exceed 0.5% in lemon-scented varieties [

65].

Limonene is known for centrally mediated anxiolytic and anti-stress effects, yet its direct antinociceptive targets are less well characterised. It binds neither cannabinoid nor opioid receptors with high affinity. Its analgesic actions appear to derive from anti-inflammatory and neuromodulatory effects. Limonene has been shown to lower pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β in animal models [

66]. A 2024 pre-clinical study found that d-limonene dramatically reduced post-operative peritoneal adhesion formation in rats by suppressing TGF-β1, TNF-α, and VEGF, restoring antioxidant enzymes, indicating marked anti-fibrotic and anti-angiogenic activity [

67].

Araújo-Filho

et al. (2020) demonstrated in a mouse sciatic-nerve-injury model that 28 days of daily limonene administration accelerated nerve regeneration, lessened mechanical hyperalgesia, and reduced spinal astrogliosis; these effects were linked to suppression of IL-1β/TNF-α and increased GAP-43, NGF, and p-ERK in the spinal cord [

68]. Limonene also modulates the adenosinergic system: a recent study showed its anxiolytic effect in mice is mediated by A₂

A adenosine receptors [

30], notable because A₂

A signalling also influences pain processing [

46].

Clinically, a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial found that a topical terpene formulation containing 1% limonene as a skin-permeation enhancer produced ≥ 85% pain reduction in over 78% of plantar-fasciitis patients within ten days, whereas placebo yielded no significant improvement [

69]. Additional data reinforce this profile: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 56 patients with irritable-bowel syndrome showed that 30 days of supplementation with menthol, limonene, and gingerol (1.5% limonene) lowered the symptom score from “moderately ill” to “borderline” with no adverse events and no significant microbiota changes, suggesting low oral doses of limonene can enhance Irritable Bowel Syndrome therapy [

70]. Neuro-behaviourally, a crossover study in 20 healthy volunteers found that co-vaporising limonene with THC, selectively blunted the cannabinoid’s anxiogenic and paranoid effects, while leaving other pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic parameters unchanged [

71].

Taken together, the evidence indicates that limonene confers analgesic efficacy chiefly in inflammatory and neuropathic pain models—likely by damping cytokine-driven hyperalgesia—while it is ineffective for acute nociceptive pain and can be irritant at high local doses. Its greatest clinical promise may lie in adjuvant use, improving mood and the immune milieu in chronic-pain patients rather than serving as a stand-alone analgesic.

3.4. Pinene

Pinene is a bicyclic monoterpene (C₁₀H₁₆) with the characteristic resinous scent of pine, found in pine resin, rosemary, and many other evergreen conifers. Cannabis often contains both α-pinene and β-pinene isomers. Pinene is common across cannabis chemovars—a survey detected α-pinene in nearly every sample, albeit usually as a minor constituent (often < 0.1 – 0.5%) [

72]. Certain cultivars—particularly some “sativa” types or hybrids—reach higher pinene levels and display a distinct pine aroma (e.g., Jack Herer, which can contain ~1 % total pinene). Pinene has attracted interest for potential cognitive benefits: it may counteract THC-induced memory deficits by inhibiting acetylcholinesterase [

40].

Pinene is a bronchodilator; both α- and β-isomers may improve airflow to the lungs [

73]. These compounds can cross the blood-brain barrier and, at high doses, exhibit mild sedative or anxiolytic effects, possibly through GABA

A modulation [

74].

The analgesic mechanisms of pinene are not fully elucidated. The incomplete known of its mechanism of action partly due to the limited number of studies employing pure pinene; many utilize essential oils rich in pinene. [

75]

α-Pinene has demonstrated significant anti-inflammatory properties in various preclinical models [

76]. It is believed to inhibit the NF-κB pathway and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6. The study conducted by Fakhri et al indicated that α-pinene may exert antinociceptive effects through interaction with the opioid system, as its effects were partially blocked by naloxone [

77]. Additionally, a possible modulation of TRPV1 channels has been suggested, although evidence is less direct compared to other terpenes [

78].

β-Pinene, although less studied than its α-isomer for analgesia, shares anti-inflammatory properties and has been shown to inhibit PGE₂ production [

79].

Studies on animal models of inflammatory pain have shown that essential oils containing pinene as a major component can reduce edema and leukocyte migration [

80]. The anti-inflammatory activity of pinene has also been associated with its ability to reduce oxidative stress [

81]. Despite promising preclinical activities, robust clinical studies on the analgesic efficacy of isolated pinene in humans are lacking. Its role in the "entourage effect" is often cited, particularly for its ability to mitigate some adverse effects of THC, such as short-term memory impairment, due to its inhibitory activity on acetylcholinesterase [

82]. Inhibition of acetylcholinesterase can enhance cholinergic neurotransmission, but its contribution to analgesia is uncertain [

83].

3.5. Linalool

Linalool is a linear monoterpenic alcohol (C₁₀H₁₈O) with a delicate floral fragrance. It is a minor terpene in most cannabis strains, typically present at 0.01–0.5%. Only some specialized strains (often indica-dominant) feature linalool as the dominant terpene (1); in most chemovars, it contributes only marginally to the terpene profile [

72]. Despite low concentrations, linalool's aroma is easily perceptible and pharmacologically potent. Linalool is notably found in lavender and is a key component of lavender essential oil, used for centuries as a calming agent [

84,

85].

Linalool acts on various neurochemical targets, and for this reason it is among the terpenes with the broadest spectrum of action. It has been shown to modulate glutamatergic transmission by non-competitively inhibiting the MK-801 site of the NMDA receptor and competitively reducing glutamate binding, without interfering with direct GABAergic activity [

86]. This action contributes to the reduction of neuronal hyperexcitability associated with central sensitization. Additionally, it inhibits specific voltage-dependent sodium and calcium channels, further limiting nociceptive transmission [

87]. This means that linalool can reduce excitatory neurotransmission, crucial in the central sensitization of pain. Batista et al. demonstrated that the antinociceptive effect of linalool in a glutamate-induced pain model was due to interference with ionotropic glutamate receptors (NMDA, AMPA, kainate) [

88].

Some studies suggest involvement of adenosine A₁/A₂

A receptors, likely through an increase in extracellular levels induced by inhibition of nitric oxide production and activation of the NO–cGMP pathway [

36]. At high concentrations, it may act as a GABA

A antagonist in vitro, but in vivo it shows enhancement of inhibitory tone, probably through indirect mechanisms [

89,

90].

Centrally, linalool exerts sedative, anxiolytic, and hypnotic effects, with modulation also mediated by the olfactory pathway [

91]. Inhalation in rodents induces analgesia and sedation dependent on the integrity of the olfactory bulb and the hypothalamic orexinergic system, suggesting an interaction between sensory inputs and limbic circuits [

92]. This supports the hypothesis of an olfactory-limbic mechanism justifying the efficacy of aromatherapy in certain pain syndromes.

Numerous animal models support the antinociceptive efficacy of linalool. In acute thermal nociception, Peana et al. demonstrated a significant increase in pain threshold in mice with systemic doses of 50–100 mg/kg, comparable or superior to those of morphine [

36]. It has been proved that linalool may even reduce behavioural responses to irritating chemical stimuli (acetic acid, capsaicin, glutamate) [

93].

In models of chronic inflammatory hyperalgesia and neuropathic pain (e.g., spinal nerve ligation), linalool has shown robust analgesic effects, with significant reduction of mechanical allodynia [

94].

Linalool exhibits marked anxiolytic activity, potentially useful in clinical contexts where pain is accompanied by psycho-emotional distress. Clinical studies on lavender oil, containing about 30% linalool, have documented anxiety reduction comparable to lorazepam [

95]. These results are particularly relevant for conditions like fibromyalgia, where anxiety and insomnia coexist with chronic pain. Proposed mechanisms include modulation of dopaminergic D₂ and muscarinic M₂ receptors, as well as involvement of the orexinergic system [

75].

Controlled studies on patients with knee osteoarthritis demonstrated significant pain reduction after massages with lavender oil [

96]. This effect has also been reported for dysmenorrhea and postherpetic pain [

63,

97]. Although large-scale randomized controlled clinical trials are lacking, preliminary evidence justifies further investigation into its use in chronic pain treatment, particularly in disorders with high affective or central components.

3.2. Humulene

Humulene, or α-caryophyllene, is a monocyclic sesquiterpene with the molecular formula C

15H

24, a structural isomer of the better-known BCP. Its presence is documented in various aromatic and medicinal plants, including hops, sage, and ginseng, where it contributes to characteristic aromatic profiles, such as the hoppy note of beer [

98]. In Cannabis sativa chemovars, α-humulene is frequently co-expressed with BCP, sharing part of its biosynthesis, and its concentration in dried flowers generally ranges between 0.01% and 0.3%. Some varieties with high BCP content also show significant co-expression of humulene, contributing to a more complex terpene profile with woody and earthy nuances [

72].

From a pharmacological standpoint, α-humulene is less characterized than its isomer, especially regarding its role in pain mechanisms. Its anti-inflammatory activity is well documented, particularly in essential oil preparations containing this sesquiterpene [

99]. Proposed mechanisms include inhibition of the NF-κB-mediated inflammatory cascade and reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β, despite the absence of direct interaction with CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors [

100]. A pharmacologically relevant action, distinct from that of BCP, involves inhibition of the cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) enzyme, responsible for the biosynthesis of inflammatory prostaglandins, as demonstrated by Fernandes et al., who observed reduced PGE2 levels in animal models treated with humulene-containing extracts [

99]. These findings suggest an activity like that of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) but mediated by a terpene with a profoundly different chemical structure.

Although systematic studies on isolated α-humulene in pain management are not available, numerous works on oils and plant extracts containing it provide indirect data on its analgesic potential. The essential oil extracted from

Peperomia serpens, containing approximately 11.5% humulene, has demonstrated efficacy in reducing pain and inflammation in murine models, with effects only partially antagonized by naloxone, suggesting the involvement of non-opioid analgesic pathways [

101]. Studies conducted on extracts from

Cordia verbenacea and

Pterodon pubescens, rich in humulene and BCP, have reported significant antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activity, likely synergistic, with reductions in edema and hyperalgesia in models of acute inflammation, primarily through inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis [

102,

103]. Furthermore, hop extracts with substantial humulene concentrations (approximately 15%) have been associated with reduced adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats, along with decreased expression of TNF-α and COX-2, further supporting the compound’s anti-inflammatory role [

104]. The topical use of humulene in analgesic creams—although currently supported more by anecdotal evidence than by robust clinical data—suggests potential utility in the treatment of localized pain, particularly when formulated in combination with other anti-inflammatory compounds such as BCP [

23].

Centrally, humulene is not commonly associated with anxiolytic or sedative effects, in contrast to other terpenes such as linalool or myrcene. Its action appears to be primarily focused on the peripheral inflammatory component of pain.

From a clinical standpoint, documentation on α-humulene remains extremely limited. No published clinical studies currently explore its analgesic or anti-inflammatory efficacy in human subjects. Therefore, future investigations should aim to isolate α-humulene and evaluate its effects in well-designed human trials, particularly in chronic pain syndromes. Such studies would help clarify its individual therapeutic potential and determine whether it offers clinically meaningful advantages either as a stand-alone agent or in synergistic phytocomplexes.

Table 1 summarizes the terpenes discussed in this review, highlighting their main characteristics, mechanisms of action, and potential therapeutic applications

4. Discussion

Authors This review highlights the therapeutic potential of cannabis-derived terpenes in pain management, while also pointing out significant gaps in the scientific literature—particularly concerning the translation of preclinical findings to the clinical context. The overwhelming majority of evidence arises from animal models or in vitro studies, with a marked scarcity of rigorously conducted randomized controlled trials in humans. A major concern is the discrepancy between the doses used in preclinical research and those realistically achievable in humans. Indeed, doses administered to rodents (50–100 mg/kg) are substantially higher than those attainable through cannabis flower consumption (≤20 mg total), potentially leading to an overestimation of antinociceptive effects. Moreover, the pharmacokinetic profile of terpenes is characterized by low bioavailability, high lipophilicity, rapid hepatic metabolism, and short half-life, complicating the identification of effective concentrations at target sites. The lack of systematic and comparative pharmacokinetic studies further limits the development of a reliable therapeutic rationale.

The analgesic effects reported for individual terpenes are highly dependent on the experimental model employed. For example, limonene exhibits efficacy in inflammatory pain models [

91], whereas BCP appears more effective against mechanical allodynia. However, the absence of meta-analyses and the prevalence of studies reporting positive outcomes raise concerns about publication bias. The limited number of direct comparisons with conventional analgesics (NSAIDs, opioids) restricts comparative evaluation of efficacy, although some estimates suggest that myrcene may reach up to 60% of morphine’s effect and that BCP may exhibit potency comparable to acetylsalicylic acid [

99]. Nonetheless, these estimates lack independent validation.

The so-called “entourage effect”—whereby terpenes are thought to synergize with phytocannabinoids to enhance analgesic outcomes—remains insufficiently supported by experimental data. In vitro studies have failed to demonstrate direct modulation of CB1 or CB2 receptors by terpenes, and clinical trials suggest that the antinociceptive activity of cannabis is primarily attributable to THC. Nevertheless, certain combinations of terpenes with each other or with cannabinoids such as CBD have shown additive or synergistic effects on alternative targets, including inflammatory pathways, oxidative stress, and non-cannabinoid neurotransmitter systems [

23]. A more comprehensive evaluation would require the inclusion of affective, functional, and biomolecular endpoints to capture the nuances of such interactions.

Another issue concerns the generalization of data obtained using synthetic terpenes or extracts from non-cannabis plant sources, which may contain co-active constituents or impurities absent from cannabis phytocomplexes. Cannabis terpene profiles are highly heterogeneous and shaped by complex interactions among multiple bioactive molecules. Preclinical studies, however, tend to evaluate isolated terpenes under conditions that do not reflect real-world exposure. Furthermore, terpene interactions with metabolic pathways may significantly affect the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of co-administered phytocompounds.

Many studies focus exclusively on reflexive responses to mechanical or thermal stimuli [

94], overlooking core aspects of chronic pain, including spontaneous pain, affective and cognitive components, and functional impact. The use of advanced animal models incorporating affective-motivational behavioural scales could yield a more realistic assessment of therapeutic efficacy [

23]. Additionally, the possibility that observed antinociceptive effects are due to sedation or motor impairment rather than true analgesia necessitates the systematic application of motor control assays and pain biomarkers.

The increasing commercial interest in the production and promotion of cannabis-based preparations exposes the scientific literature to potential conflicts of interest. Ensuring rigorous transparency in research funding and author disclosures is essential to prevent the enthusiasm surrounding the entourage effect or the “natural” use of terpenes from overshadowing an objective appraisal of the available evidence.

In summary, while biological data support a potential analgesic role for terpenes, the current body of clinical evidence is insufficient to warrant their systematic integration into therapeutic practice. Future research must advance toward robust experimental protocols, active comparators, and in-depth exploration of specific mechanisms of action for each terpene. Only through well-designed, randomized clinical trials will it be possible to definitively establish the role of cannabis terpenes in the treatment of chronic pain.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, a thorough analysis of the current literature reveals that, despite their structural and functional heterogeneity, cannabis-derived terpenes represent a promising frontier in analgesic research. Compounds such as BCP, myrcene, limonene, linalool, and α-humulene have demonstrated significant antinociceptive activity in preclinical models, mediated by multiple mechanisms of action often distinct from those of classical cannabinoids. Their effects span both peripheral and central levels, encompassing the modulation of inflammatory pathways (COX, NF-κB), neurotransmitter receptors (adenosinergic, opioid, GABAergic), and neurotrophic signalling cascades (ERK, NGF), with possible synergistic effects when administered in combination or within complex phytochemical matrices.

However, the enthusiasm generated by the pharmacological activity observed in animal models must be tempered by an awareness of the numerous methodological limitations that still affect the field. The lack of controlled clinical trials, the scarcity of terpene-specific pharmacokinetic data, the use of non-translatable dosing regimens, and the absence of direct comparisons with standard analgesics all restrict the generalizability of current findings. Moreover, while the "entourage effect" remains an appealing hypothesis, it requires rigorous validation through multifactorial experimental designs and the identification of clinically meaningful endpoints that extend beyond basic nociceptive behavioural metrics.

Looking ahead, the path toward genuine clinical applicability of analgesic terpenes will necessarily depend on randomized trials, the development of optimized-bioavailability formulations, pharmacological interaction studies with cannabinoids and conventional drugs, and a refinement of preclinical models to incorporate affective and functional dimensions of pain. Only through an integrated, methodologically robust, and clinically oriented approach will it be possible to determine whether terpenes can evolve from promising bioactive molecules into validated therapeutic agents for the management of chronic pain.

6. Future Perspectives

In the coming decade, it will be essential to systematically translate preclinical evidence on terpenes into clinical applications through the development and implementation of advanced phase randomized clinical trials. These studies should employ standardized terpene formulations delivered via optimized bioavailability systems—such as pressurized inhalers or titratable oral matrices. Such trials must integrate pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analyses, including validated pain assessment scales, quantification of inflammatory and neurochemical biomarkers, and evaluations of functional outcomes.

Concurrently, it will be critical to initiate mechanistic investigations at both the molecular and systemic levels, leveraging state-of-the-art technologies such as CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing, integrated omics analyses (transcriptomics and proteomics), and advanced functional neuroimaging. These tools will enable precise mapping of terpene targets—including non-canonical pathways—and inform the rational design of novel terpene analogues with optimized pharmacological profiles in terms of efficacy, selectivity, and metabolic stability.

Moreover, terpenes must be incorporated into personalized and multimodal therapeutic strategies, tailored to the phenotypic profile of pain and the patient's pharmacogenetic background. The objective is to maximize clinical benefit, reduce adverse events, and solidify the foundation of an innovative therapeutic paradigm—one grounded in replicable evidence and methodologically rigorous research—for the management of chronic pain.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AA and SDF.; Methodology, AA; Software, AA; Validation, SDF, AA and MF; Investigation, AA; Writing—original draft preparation, AA; Writing—review and editing, SDF; Visualization, AA, VM and PS; Supervision, MBP, AA, MF; Project administration, MCP, AAAll authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ren, K.; Dubner, R. Interactions between the immune and nervous systems in pain. Nat Med 2010, 16, 1267–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P.P.; Zhang, L.; He, L.; Zhao, N.; Guan, Z. The Role of Neuro-Immune Interactions in Chronic Pain: Implications for Clinical Practice. J Pain Res 2022, 15, 2223–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domenichiello, A.F.; Ramsden, C.E. The silent epidemic of chronic pain in older adults. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2019, 93, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, J.D.; Shafritz, K.M. An Integrative Neuroscience Framework for the Treatment of Chronic Pain: From Cellular Alterations to Behavior. Front Integr Neurosci 2018, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Gewandter, J.S.; Geha, P. Brain Imaging Biomarkers for Chronic Pain. Front Neurol 2021, 12, 734821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, R.R.; Berta, T.; Nedergaard, M. Glia and pain: is chronic pain a gliopathy? Pain 2013, 154 Suppl 1, S10–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latremoliere, A.; Woolf, C.J. Central sensitization: a generator of pain hypersensitivity by central neural plasticity. J Pain 2009, 10, 895–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarberg, B.; Peppin, J. Pain Pathways and Nervous System Plasticity: Learning and Memory in Pain. Pain Med 2019, 20, 2421–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, R.R.; Nackley, A.; Huh, Y.; Terrando, N.; Maixner, W. Neuroinflammation and Central Sensitization in Chronic and Widespread Pain. Anesthesiology 2018, 129, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuner, R.; Flor, H. Structural plasticity and reorganisation in chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci 2016, 18, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliss, T.V.; Collingridge, G.L.; Kaang, B.K.; Zhuo, M. Synaptic plasticity in the anterior cingulate cortex in acute and chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci 2016, 17, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamauchi, N.; Sato, K.; Sato, K.; Murakawa, S.; Hamasaki, Y.; Nomura, H.; Amano, T.; Minami, M. Chronic pain-induced neuronal plasticity in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis causes maladaptive anxiety. Sci Adv 2022, 8, eabj5586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaechi, O.; Huffman, M.M.; Featherstone, K. Pharmacologic Therapy for Acute Pain. Am Fam Physician 2021, 104, 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Alorfi, N.M. Pharmacological Methods of Pain Management: Narrative Review of Medication Used. Int J Gen Med 2023, 16, 3247–3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sic, A.; Manzar, A.; Knezevic, N.N. The Role of Phytochemicals in Managing Neuropathic Pain: How Much Progress Have We Made? Nutrients 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, A.; Khan, A.; Ahmad, I.; Alghamdi, S.; Rajab, B.S.; Babalghith, A.O.; Alshahrani, M.Y.; Islam, S.; Islam, M.R. Fla-vonoids a Bioactive Compound from Medicinal Plants and Its Therapeutic Applications. Biomed Res Int 2022, 2022, 5445291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, M.; Sashide, Y.; Toyota, R.; Ito, H. The Phytochemical, Quercetin, Attenuates Nociceptive and Pathological Pain: Neurophysiological Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. Molecules 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, Y.; Uta, D.; Furue, H.; Tominaga, M. Pain-enhancing mechanism through interaction between TRPV1 and anoctamin 1 in sensory neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, 5213–5218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, R.H.; Wang, C.Y.; Yang, C.M. NF-kappaB Signaling Pathways in Neurological Inflammation: A Mini Review. Front Mol Neurosci 2015, 8, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, M.M.; Chandra, S.; Gul, S.; ElSohly, M.A. Cannabinoids, Phenolics, Terpenes and Alkaloids of Cannabis. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liktor-Busa, E.; Keresztes, A.; LaVigne, J.; Streicher, J.M.; Largent-Milnes, T.M. Analgesic Potential of Terpenes Derived from Cannabis sativa. Pharmacol Rev 2021, 73, 98–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuckovic, S.; Srebro, D.; Vujovic, K.S.; Vucetic, C.; Prostran, M. Cannabinoids and Pain: New Insights From Old Molecules. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaVigne, J.E.; Hecksel, R.; Keresztes, A.; Streicher, J.M. Cannabis sativa terpenes are cannabimimetic and selectively enhance cannabinoid activity. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 8232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferber, S.G.; Namdar, D.; Hen-Shoval, D.; Eger, G.; Koltai, H.; Shoval, G.; Shbiro, L.; Weller, A. The "Entourage Effect": Terpenes Coupled with Cannabinoids for the Treatment of Mood Disorders and Anxiety Disorders. Curr Neurophar-macol 2020, 18, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, M. Neurophysiological Mechanisms Underlying the Attenuation of Nociceptive and Pathological Pain by Phytochemicals: Clinical Application as Therapeutic Agents. Progress in Neurobiology 2024, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Chida, R.; Utugi, S.; Sashide, Y.; Takeda, M. Systemic Administration of the Phytochemical, Myricetin, Attenuates the Excitability of Rat Nociceptive Secondary Trigeminal Neurons. Molecules 2025, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitjean, H.; Heberle, E.; Hilfiger, L.; Lapies, O.; Rodrigue, G.; Charlet, A. TRP channels and monoterpenes: Past and current leads on analgesic properties. Front Mol Neurosci 2022, 15, 945450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-f.; Ding, Y.-y.; Guan, H.-r.; Zhou, C.-j.; He, X.; Shao, Y.-t.; Wang, Y.-b.; Wang, N.; Li, B.; Lv, G.-y.; et al. The Pharmacological Effects and Potential Applications of Limonene From Citrus Plants: A Review. Natural Product Communications 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaimoto, T.; Hatakeyama, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Imagawa, T.; Tominaga, M.; Ohta, T. Involvement of transient receptor potential A1 channel in algesic and analgesic actions of the organic compound limonene. Eur J Pain 2016, 20, 1155–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Seo, S.; Lamichhane, S.; Seo, J.; Hong, J.T.; Cha, H.J.; Yun, J. Limonene has anti-anxiety activity via adenosine A2A receptor-mediated regulation of dopaminergic and GABAergic neuronal function in the striatum. Phytomedicine 2021, 83, 153474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.; Song, Y.; Gu, S.M.; Min, H.K.; Hong, J.T.; Cha, H.J.; Yun, J. D-limonene Inhibits Pentylenetetrazole-Induced Seizure via Adenosine A2A Receptor Modulation on GABAergic Neuronal Activity. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Almeida, A.A.; Silva, R.O.; Nicolau, L.A.; de Brito, T.V.; de Sousa, D.P.; Barbosa, A.L.; de Freitas, R.M.; Lopes, L.D.; Medeiros, J.R.; Ferreira, P.M. Physio-pharmacological Investigations About the Anti-inflammatory and Antinocicep-tive Efficacy of (+)-Limonene Epoxide. Inflammation 2017, 40, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurindo, L.F.; Santos, A.; Carvalho, A.C.A.; Bechara, M.D.; Guiguer, E.L.; Goulart, R.A.; Vargas Sinatora, R.; Araujo, A.C.; Barbalho, S.M. Phytochemicals and Regulation of NF-kB in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: An Overview of In Vitro and In Vivo Effects. Metabolites 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Peng, F.; Xing, Z.; Chen, J.; Peng, C.; Li, D. Beneficial effects of natural flavonoids on neuroinflammation. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1006434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klawitter, J.; Weissenborn, W.; Gvon, I.; Walz, M.; Klawitter, J.; Jackson, M.; Sempio, C.; Joksimovic, S.L.; Shokati, T.; Just, I.; et al. beta-Caryophyllene Inhibits Monoacylglycerol Lipase Activity and Increases 2-Arachidonoyl Glycerol Levels In Vivo: A New Mechanism of Endocannabinoid-Mediated Analgesia? Mol Pharmacol 2024, 105, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peana, A.T.; Rubattu, P.; Piga, G.G.; Fumagalli, S.; Boatto, G.; Pippia, P.; De Montis, M.G. Involvement of adenosine A1 and A2A receptors in (-)-linalool-induced antinociception. Life Sci 2006, 78, 2471–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; Xu, D.; Zhang, N.; Chen, Y.; Yang, J.; Sun, L. Beta-Myrcene as a Sedative-Hypnotic Component from Lavender Essential Oil in DL-4-Chlorophenylalanine-Induced-Insomnia Mice. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa-Juarez, J.V.; Arrieta, J.; Briones-Aranda, A.; Cruz-Antonio, L.; Lopez-Lorenzo, Y.; Sanchez-Mendoza, M.E. Synergistic Antinociceptive Effect of beta-Caryophyllene Oxide in Combination with Paracetamol, and the Corre-sponding Gastroprotective Activity. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seekins, C.A.; Welborn, A.M.; Schwarz, A.M.; Streicher, J.M. Select terpenes from Cannabis sativa are antinociceptive in mouse models of post-operative pain and fibromyalgia via adenosine A(2a) receptors. Pharmacol Rep 2025, 77, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, E.B. Taming THC: potential cannabis synergy and phytocannabinoid-terpenoid entourage effects. Br J Pharmacol 2011, 163, 1344–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuutinen, T. Medicinal properties of terpenes found in Cannabis sativa and Humulus lupulus. Eur J Med Chem 2018, 157, 198–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Sun, N.; Hill, J.E. Comprehensive Profiling of Terpenes and Terpenoids in Different Cannabis Strains Using GC × GC-TOFMS. Separations 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raz, N.; Eyal, A.M.; Zeitouni, D.B.; Hen-Shoval, D.; Davidson, E.M.; Danieli, A.; Tauber, M.; Ben-Chaim, Y. Selected cannabis terpenes synergize with THC to produce increased CB1 receptor activation. Biochem Pharmacol 2023, 212, 115548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanus, L.O.; Hod, Y. Terpenes/Terpenoids in Cannabis: Are They Important? Med Cannabis Cannabinoids 2020, 3, 25–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, E.A.; Wang, M.; Radwan, M.M.; Wanas, A.S.; Majumdar, C.G.; Avula, B.; Wang, Y.H.; Khan, I.A.; Chandra, S.; Lata, H.; et al. Analysis of Terpenes in Cannabis sativa L. Using GC/MS: Method Development, Validation, and Ap-plication. Planta Med 2019, 85, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, A.M.; Keresztes, A.; Bui, T.; Hecksel, R.J.; Pena, A.; Lent, B.; Gao, Z.G.; Gamez-Rivera, M.; Seekins, C.A.; Chou, K.; et al. Terpenes from Cannabis sativa Induce Antinociception in Mouse Chronic Neuropathic Pain via Activation of Spinal Cord Adenosine A(2A) Receptors. bioRxiv 2023. [CrossRef]

- Jansen, C.; Shimoda, L.M.N.; Kawakami, J.K.; Ang, L.; Bacani, A.J.; Baker, J.D.; Badowski, C.; Speck, M.; Stokes, A.J.; Small-Howard, A.L.; et al. Myrcene and terpene regulation of TRPV1. Channels (Austin) 2019, 13, 344–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heblinski, M.; Santiago, M.; Fletcher, C.; Stuart, J.; Connor, M.; McGregor, I.S.; Arnold, J.C. Terpenoids Commonly Found in Cannabis sativa Do Not Modulate the Actions of Phytocannabinoids or Endocannabinoids on TRPA1 and TRPV1 Channels. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res 2020, 5, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, V.S.; Menezes, A.M.; Viana, G.S. Effect of myrcene on nociception in mice. J Pharm Pharmacol 1990, 42, 877–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alayoubi, M.; Rodrigues, A.; Wu, C.; Whitehouse, E.; Nguyen, J.; Cooper, Z.D.; O'Neill, P.R.; Cahill, C.M. Elucidating interplay between myrcene and cannabinoid receptor 1 receptors to produce antinociception in mouse models of neuropathic pain. Pain 2025, undefined. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, J.J.; McKenna, M.K. Anti-Inflammatory and Analgesic Properties of the Cannabis Terpene Myrcene in Rat Adjuvant Monoarthritis. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surendran, S.; Qassadi, F.; Surendran, G.; Lilley, D.; Heinrich, M. Myrcene-What Are the Potential Health Benefits of This Flavouring and Aroma Agent? Front Nutr 2021, 8, 699666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, J.K.; Gambell, E.; Gibbons, T.; Martin, T.J.; Kaplan, J.S. Sex Differences in the Anxiolytic Properties of Common Cannabis Terpenes, Linalool and beta-Myrcene, in Mice. NeuroSci 2024, 5, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudge, E.M.; Brown, P.N.; Murch, S.J. The Terroir of Cannabis: Terpene Metabolomics as a Tool to Understand Can-nabis sativa Selections. Planta Med 2019, 85, 781–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzantini, C.; El Bourji, Z.; Parisio, C.; Davolio, P.L.; Cocchi, A.; Pellegrini-Giampietro, D.E.; Landucci, E. Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Cannabidiol and Beta-Caryophyllene Alone or Combined in an In Vitro Inflammation Model. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, L.F.B.; Oliveira, H.B.M.; das Neves Selis, N.; Morbeck, L.L.B.; Santos, T.C.; da Silva, L.S.C.; Viana, J.C.S.; Reis, M.M.; Sampaio, B.A.; Campos, G.B.; et al. beta-caryophyllene and docosahexaenoic acid, isolated or associated, have potential antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects in vitro and in vivo. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 19199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandiffio, R.; Geddo, F.; Cottone, E.; Querio, G.; Antoniotti, S.; Gallo, M.P.; Maffei, M.E.; Bovolin, P. Protective Effects of (E)-beta-Caryophyllene (BCP) in Chronic Inflammation. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klauke, A.L.; Racz, I.; Pradier, B.; Markert, A.; Zimmer, A.M.; Gertsch, J.; Zimmer, A. The cannabinoid CB(2) recep-tor-selective phytocannabinoid beta-caryophyllene exerts analgesic effects in mouse models of inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2014, 24, 608–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, E.; Khajah, M.A.; Masocha, W. beta-Caryophyllene, a CB2-Receptor-Selective Phytocannabinoid, Suppresses Mechanical Allodynia in a Mouse Model of Antiretroviral-Induced Neuropathic Pain. Molecules 2019, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, K.D.C.; Islam, M.T.; Ali, E.S.; Rouf, R.; Uddin, S.J.; Dev, S.; Shilpi, J.A.; Shill, M.C.; Reza, H.M.; Das, A.K.; et al. A systematic review on the neuroprotective perspectives of beta-caryophyllene. Phytother Res 2018, 32, 2376–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Oliveira, G.L.; da Silva, J.; Dos Santos, C.L.d.S.A.P.; Feitosa, C.M.; de Castro Almeida, F.R. Anticonvulsant, Anxiolytic and Antidepressant Properties of the beta-caryophyllene in Swiss Mice: Involvement of Benzodiaze-pine-GABAAergic, Serotonergic and Nitrergic Systems. Curr Mol Pharmacol 2021, 14, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fari, G.; Megna, M.; Scacco, S.; Ranieri, M.; Raele, M.V.; Chiaia Noya, E.; Macchiarola, D.; Bianchi, F.P.; Carati, D.; Panico, S.; et al. Hemp Seed Oil in Association with beta-Caryophyllene, Myrcene and Ginger Extract as a Nutraceutical In-tegration in Knee Osteoarthritis: A Double-Blind Prospective Case-Control Study. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, M.C.; Hsu, T.F.; Lai, A.C.; Lin, Y.T.; Lin, C.C. Pain relief assessment by aromatic essential oil massage on outpatients with primary dysmenorrhea: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2012, 38, 817–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertsch, J.; Pertwee, R.G.; Di Marzo, V. Phytocannabinoids beyond the Cannabis plant - do they exist? Br J Pharmacol 2010, 160, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, K.D.; McKernan, K.; Pauli, C.; Roe, J.; Torres, A.; Gaudino, R. Genomic characterization of the complete terpene synthase gene family from Cannabis sativa. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0222363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathem, S.H.; Nasrawi, Y.S.; Mutlag, S.H.; Nauli, S.M. Limonene Exerts Anti-Inflammatory Effect on LPS-Induced Je-junal Injury in Mice by Inhibiting NF-kappaB/AP-1 Pathway. Biomolecules 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razazi, A.; Kakanezhadi, A.; Raisi, A.; Pedram, B.; Dezfoulian, O.; Davoodi, F. D-limonene inhibits peritoneal adhesion formation in rats via anti-inflammatory, anti-angiogenic, and antioxidative effects. Inflammopharmacology 2024, 32, 1077–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araujo-Filho, H.G.; Pereira, E.W.M.; Heimfarth, L.; Souza Monteiro, B.; Santos Passos, F.R.; Siqueira-Lima, P.; Gandhi, S.R.; Viana Dos Santos, M.R.; Guedes da Silva Almeida, J.R.; Picot, L.; et al. Limonene, a food additive, and its active metabolite perillyl alcohol improve regeneration and attenuate neuropathic pain after peripheral nerve injury: Ev-idence for IL-1beta, TNF-alpha, GAP, NGF and ERK involvement. Int Immunopharmacol 2020, 86, 106766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, B.E.; Baillie, J.E. Randomized placebo controlled trial of phytoterpenes in DMSO for the treatment of plantar fasciitis. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 17621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivashkin, V.T.; Kudryavtseva, A.V.; Krasnov, G.S.; Poluektov, Y.M.; Morozova, M.A.; Shifrin, O.S.; Beniashvili, A.G.; Mamieva, Z.A.; Kovaleva, A.L.; Ulyanin, A.I.; et al. Efficacy and safety of a food supplement with standardized menthol, limonene, and gingerol content in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: A double-blind, randomized, place-bo-controlled trial. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0263880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spindle, T.R.; Zamarripa, C.A.; Russo, E.; Pollak, L.; Bigelow, G.; Ward, A.M.; Tompson, B.; Sempio, C.; Shokati, T.; Klawitter, J.; et al. Vaporized D-limonene selectively mitigates the acute anxiogenic effects of Del-ta9-tetrahydrocannabinol in healthy adults who intermittently use cannabis. Drug Alcohol Depend 2024, 257, 111267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casano, S.; Grassi, G.; Martini, V.; Michelozzi, M. Variations in terpene profiles of different strains of Cannabis Sativa L. 2011; pp. 115-121.

- Gautam, M.; Gabrani, R. Comparative analysis of alpha-pinene alone and combined with temozolomide in human glioblastoma cells. Nat Prod Res 2024, 38, 3657–3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafie, F.; Kooshki, R.; Abbasnejad, M.; Rahbar, I.; Raoof, M.; Nekouei, A.H. alpha-Pinene Influence on Pulpal Pain-Induced Learning and Memory Impairment in Rats Via Modulation of the GABAA Receptor. Adv Biomed Res 2022, 11, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weston-Green, K.; Clunas, H.; Jimenez Naranjo, C. A Review of the Potential Use of Pinene and Linalool as Ter-pene-Based Medicines for Brain Health: Discovering Novel Therapeutics in the Flavours and Fragrances of Cannabis. Front Psychiatry 2021, 12, 583211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, O.V.; Silverio, M.S.; Del-Vechio-Vieira, G.; Matheus, F.C.; Yamamoto, C.H.; Alves, M.S. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of the essential oil from Eremanthus erythropappus leaves. J Pharm Pharmacol 2008, 60, 771–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhri, S.; Jafarian, S.; Majnooni, M.B.; Farzaei, M.H.; Mohammadi-Noori, E.; Khan, H. Anti-nociceptive and an-ti-inflammatory activities of the essential oil isolated from Cupressus arizonica Greene fruits. Korean J Pain 2022, 35, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepetkin, I.A.; Kushnarenko, S.V.; Ozek, G.; Kirpotina, L.N.; Sinharoy, P.; Utegenova, G.A.; Abidkulova, K.T.; Ozek, T.; Baser, K.H.; Kovrizhina, A.R.; et al. Modulation of Human Neutrophil Responses by the Essential Oils from Ferula akitschkensis and Their Constituents. J Agric Food Chem 2016, 64, 7156–7170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.T.; He, Y.H.; Lo, Y.H.; Chiang, Y.T.; Wang, S.Y.; Bezirganoglu, I.; Kumar, K.J.S. Essential Oil from Glossogyne tenuifolia Inhibits Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammation-Associated Genes in Macro-Phage Cells via Suppression of NF-kappaB Signaling Pathway. Plants (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E.S.; Abrantes Coelho, G.L.; Saraiva Fontes Loula, Y.K.; Saraiva Landim, B.L.; Fernandes Lima, C.N.; Tavares de Sousa Machado, S.; Pereira Lopes, M.J.; Soares Gomes, A.D.; Martins da Costa, J.G.; Alencar de Menezes, I.R.; et al. Hypoglycemic, Hypolipidemic, and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Beta-Pinene in Diabetic Rats. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2022, 2022, 8173307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, K.; Zalaghi, M.; Shehnizad, E.G.; Salari, G.; Baghdezfoli, F.; Ebrahimifar, A. The effects of alpha-pinene on inflammatory responses and oxidative stress in the formalin test. Brain Res Bull 2023, 203, 110774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavala-Ocampo, L.M.; Aguirre-Hernandez, E.; Lopez-Camacho, P.Y.; Cardenas-Vazquez, R.; Dorazco-Gonzalez, A.; Basurto-Islas, G. Acetylcholinesterase inhibition and antioxidant activity properties of Petiveria alliacea L. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldufani, J.; Blaise, G. The role of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors such as neostigmine and rivastigmine on chronic pain and cognitive function in aging: A review of recent clinical applications. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2019, 5, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Nam, E.S.; Lee, Y.; Kang, H.J. Effects of Lavender on Anxiety, Depression, and Physiological Parameters: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci) 2021, 15, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donelli, D.; Antonelli, M.; Bellinazzi, C.; Gensini, G.F.; Firenzuoli, F. Effects of lavender on anxiety: A systematic re-view and meta-analysis. Phytomedicine 2019, 65, 153099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brum, L.F.; Elisabetsky, E.; Souza, D. Effects of linalool on [(3)H]MK801 and [(3)H] muscimol binding in mouse cortical membranes. Phytother Res 2001, 15, 422–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narusuye, K.; Kawai, F.; Matsuzaki, K.; Miyachi, E. Linalool suppresses voltage-gated currents in sensory neurons and cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2005, 112, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista, P.A.; Werner, M.F.; Oliveira, E.C.; Burgos, L.; Pereira, P.; Brum, L.F.; Santos, A.R. Evidence for the involvement of ionotropic glutamatergic receptors on the antinociceptive effect of (-)-linalool in mice. Neurosci Lett 2008, 440, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanos, S.; Elsharif, S.A.; Janzen, D.; Buettner, A.; Villmann, C. Metabolic Products of Linalool and Modulation of GABA(A) Receptors. Front Chem 2017, 5, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phuong, T.N.T.; Jang, S.H.; Rijal, S.; Jung, W.K.; Kim, J.; Park, S.J.; Han, S.K. GABA- and Glycine-Mimetic Responses of Linalool on the Substantia Gelatinosa of the Trigeminal Subnucleus Caudalis in Juvenile Mice: Pain Management through Linalool-Mediated Inhibitory Neurotransmission. Am J Chin Med 2021, 49, 1437–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agatonovic-Kustrin, S.; Kustrin, E.; Gegechkori, V.; Morton, D.W. Anxiolytic Terpenoids and Aromatherapy for Anxiety and Depression. Adv Exp Med Biol 2020, 1260, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashiro, S.; Yamaguchi, R.; Ishikawa, S.; Sakurai, T.; Kajiya, K.; Kanmura, Y.; Kuwaki, T.; Kashiwadani, H. Odour-induced analgesia mediated by hypothalamic orexin neurons in mice. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 37129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, M.; Takahashi, K.; Ohta, T. Inhibitory effects of linalool, an essential oil component of lavender, on no-ciceptive TRPA1 and voltage-gated Ca(2+) channels in mouse sensory neurons. Biochem Biophys Rep 2023, 34, 101468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berliocchi, L.; Russo, R.; Levato, A.; Fratto, V.; Bagetta, G.; Sakurada, S.; Sakurada, T.; Mercuri, N.B.; Corasaniti, M.T. (-)-Linalool attenuates allodynia in neuropathic pain induced by spinal nerve ligation in c57/bl6 mice. Int Rev Neurobiol 2009, 85, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, W.S.; Dolzhenko, A.V.; Jalal, Z.; Hadi, M.A.; Khan, T.M. Efficacy and safety of lavender essential oil (Silexan) capsules among patients suffering from anxiety disorders: A network meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 18042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasiri, A.; Mahmodi, M.A.; Nobakht, Z. Effect of aromatherapy massage with lavender essential oil on pain in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2016, 25, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, J.; Shin, Y.K.; Seol, G.H. Alleviating effect of lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) and its major components on postherpetic pain: a randomized blinded controlled trial. BMC Complement Med Ther 2024, 24, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistelli, L.; Ferri, B.; Cioni, P.L.; Koziara, M.; Agacka, M.; Skomra, U. Aroma profile and bitter acid characterization of hop cones (Humulus lupulus L.) of five healthy and infected Polish cultivars. Industrial Crops and Products 2018, 124, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, E.S.; Passos, G.F.; Medeiros, R.; da Cunha, F.M.; Ferreira, J.; Campos, M.M.; Pianowski, L.F.; Calixto, J.B. Anti-inflammatory effects of compounds alpha-humulene and (-)-trans-caryophyllene isolated from the essential oil of Cordia verbenacea. Eur J Pharmacol 2007, 569, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, D.; Hwang, S.J.; Song, Y.S.; Lee, H.J. Humulene Inhibits Acute Gastric Mucosal Injury by Enhancing Mucosal Integrity. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, B.G.; Silva, A.S.; Souza, G.E.; Figueiredo, J.G.; Cunha, F.Q.; Lahlou, S.; da Silva, J.K.; Maia, J.G.; Sousa, P.J. Chemical composition, antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects in rodents of the essential oil of Peperomia serpens (Sw. ) Loud. J Ethnopharmacol 2011, 138, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basting, R.T.; Spindola, H.M.; Sousa, I.M.O.; Queiroz, N.C.A.; Trigo, J.R.; de Carvalho, J.E.; Foglio, M.A. Pterodon pubescens and Cordia verbenacea association promotes a synergistic response in antinociceptive model and improves the anti-inflammatory results in animal models. Biomed Pharmacother 2019, 112, 108693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martim, J.K.P.; Maranho, L.T.; Costa-Casagrande, T.A. Review: Role of the chemical compounds present in the es-sential oil and in the extract of Cordia verbenacea DC as an anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial and healing product. J Ethnopharmacol 2021, 265, 113300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hougee, S.; Faber, J.; Sanders, A.; Berg, W.B.; Garssen, J.; Smit, H.F.; Hoijer, M.A. Selective inhibition of COX-2 by a standardized CO2 extract of Humulus lupulus in vitro and its activity in a mouse model of zymosan-induced arthritis. Planta Med 2006, 72, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).