1. Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are a class of carcinogenic organic pollutants that are widely distributed globally. They are composed of two or more fused benzene rings, characterized by stable chemical structures and low biodegradability. Over 90% of PAHs in the environment accumulate in the topsoil, where they are easily absorbed and accumulated by crops such as vegetables and grains. These compounds pose significant risks to human health through dietary intake and other exposure pathways [

1,

2]. Sixteen PAHs, including phenanthrene (PHE), pyrene, and benzo(a)pyrene, have been listed as priority pollutants by environmental agencies in China, Europe, and the United States [

3,

4]. Among the various remediation methods for PAH-contaminated soil, bioremediation has garnered widespread attention owing to its advantages of being environmentally friendly, cost effective, and scalable. Various types of bioremediation include phytoremediation, microbial remediation, and phytomicrobial remediation [

5,

6].

Plants not only absorb, transport, and accumulate PAHs in contaminated soil but also stimulate the growth of PAH-degrading microorganisms in the rhizosphere, thereby synergistically enhancing the degradation of PAHs in soil [

7,

8]. However, to date, plants capable of hyperaccumulating PAHs have not been identified. Additionally, the microbial degradation of PAHs is inhibited by the competition between plants and microorganisms for soil nutrients. Multiple studies have reported extremely low remediation efficiency of plants in in situ remediation experiments of PAH-contaminated sites [

9,

10,

11,

12], limiting the application prospects of plants in PAH-contaminated soil remediation. Therefore, identifying appropriate assisted methods to enhance the PAH removal capacity of remediation plants and unlock their PAH biodegradation or hyperaccumulation potential could help overcome the bottlenecks in plant-based remediation of PAH-contaminated soils [

13].

The plant-white rot fungus co-remediation system is a feasible and efficient biological remediation strategy for PAH-contaminated soils [

11,

14]. García-Sánchez et al. [

11] found that the corn (

Zea mays)-white rot fungus co-remediation system not only enhances the overall PAH removal rate but also significantly improves the removal efficiency of recalcitrant, carcinogenic high-molecular-weight PAHs. Inoculation with white rot fungi significantly increases the biomass and activity of corn rhizospheric microorganisms. Some studies speculate that the proliferation and metabolism of rhizospheric microorganisms depend on nutrients transported by plants to the roots and that root exudates released by plants provide reaction substrates for microbial growth and the co-metabolic degradation of PAHs [

15,

16].

Salix viminalis alleviates the antagonistic effects of

Crucibulum laeve and indigenous microbial communities and synergistically increases the relative abundance of indigenous degradation microbial communities and PAH degradation genes with

C. laeve, thereby enhancing PAH removal efficiency [

14,

17]. White rot fungi can promote absorption of phosphorus and other mineral elements through roots, thereby enhancing plant stress resistance [

17]. Therefore, plant–white rot fungus interactions in the rhizosphere offer an ecologically friendly approach to enhance PAH removal in soil and promote rhizospheric phosphorus cycling [

18,

19,

20].

Microbial communities are ubiquitous and extremely complex, exhibiting unparalleled physiological and phylogenetic diversity [

21]. The fungal mycelium harbors unique microbial communities that can be regarded as the fungus’s second genome [

22]. Inorganic phosphates, which are highly available forms of phosphorus, are the primary form of phosphorus absorbed by root systems. Soil microorganisms colonizing fungal hyphal interfaces release various enzymes that can strongly degrade soil organic phosphorus, greatly accelerating soil phosphorus turnover and facilitating plant uptake and utilization of difficult-to-utilize phosphorus forms, such as phytate [

23]. The extracellular enzymes or organic acids secreted by white rot fungi can alter the mycelium interface and rhizospheric microenvironments. Hence, white rot fungi may influence the species and abundance of phosphorus cycle-related members of the mycelium interface or rhizospheric soil microbial communities, thereby enhancing the activation capacity of phosphorus-solubilizing bacteria for organic phosphorus and improving soil phosphorus turnover and availability [

14]. However, the extent to which these processes influence soil phosphorus turnover and PAH degradation remain unclear because of the complex interactions among indigenous microbial communities, white rot fungi, and plant rhizosphere in plant–white rot fungus remediation of PAH-contaminated soils [

11]. Longitudinal characterization of soil microbial communities is necessary to understand the microbial characteristics driving nutrient uptake and PAH removal interactions between plants and microbes, as well as between microbes themselves [

17,

24].

Despite significant progress in plant–white rot fungus remediation of PAH-contaminated soils, the impact of phosphorus availability on soil microbial community dynamics during this process remains unclear. Thus, this study aimed to investigate the effects of different phosphorus addition forms on soil microbial community composition, function, and PAH removal in various bioremediation strategies.

S. viminalis and

C. laeve were selected as experimental materials for bioremediation because of their excellent PAH removal efficiencies in soil [

17,

25]. Microbial community composition and diversity were analyzed using 16S rDNA and ITS marker gene amplicon sequencing. Additionally, soil physicochemical factors were measured, and the relationships between microbial communities and environmental factors such as phosphorus form, white rot fungus inoculation, and PAHs were explored. The abundance of PAH degradation genes was predicted using Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States (PICRUSt) software. The results of high-throughput sequencing were integrated using co-occurrence network methods, providing novel insights into the organizational structure and biological interactions of soil microbial communities during plant–white rot fungus remediation [

26]. The findings of this study contribute to understanding the impact of phosphorus availability on plant–white rot fungus remediation and provide theoretical references for optimizing this method.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

PHE was purchased from Aldrich-Frederick Company (USA). PHE, potassium dihydrogen phosphate, calcium phytate, and other chemical reagents used in this study were all of analytical grade or higher purity.

2.2. Spiked Soil

The experimental soil, classified as a leached soil (yellowish-brown soil) according to the soil classification system of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, was collected at the 0–20 cm depth from a farm located in the suburbs of Beijing (40°10′59″N; 116°27′21″E). After being transported to the laboratory, the soil samples were mixed thoroughly, air-dried at room temperature, and then sieved through a 2 mm mesh screen. The physical and chemical properties of the soil samples were as follows: pH 7.44, 10.8 g·kg-1 organic matter, 11.3 g·kg-1 total nitrogen, 968.0 mg·kg-1 total phosphorus, 20.0 μg·kg-1 phyllanthus, 15.9 mg·kg-1 nitrate nitrogen, 70.0 mg·kg-1 ammonium nitrogen, 15.0 mg·kg-1 available phosphorus, and 134.0 mg·kg-1 available potassium. High-purity PHE was dissolved in acetone, added to 10% of the total soil, stirred thoroughly in a small bucket, and then placed in a fume hood until the acetone completely evaporated. The contaminated soil was uniformly mixed with the remaining 90% uncontaminated soil to achieve an initial PHE concentration of approximately 4000 μg·kg-1. It was then placed in plastic boxes, aged at room temperature for 6 weeks, and sieved through a 2 mm mesh screen.

2.3. Plant and Fungal Inoculum Preparation

Salix viminalis was selected as the plant-based remediation material in this study owing to its excellent PAH removal capacity, rapid growth rate, and high biomass. One-year-old branches of S. viminalis clonal lines grown at the Shenyang Creative Agriculture Research Institute (Shenyang, China) were selected. The branches were divided into cuttings with a length of 12 cm and diameter of 1.0±0.2 cm. The cuttings were placed in clean water to absorb sufficient moisture and then planted in nutrient pots with dimensions of φ8 cm × 10 cm. The cultivation medium was a mixture of peat moss and perlite in a ratio of 6:1 (v/v), with regular watering. After germination, the plants were further cultivated in a greenhouse for 4 weeks, and S. viminalis cuttings with consistent growth were selected for the experiment.

Previous studies reported that a system combining different functional groups of plants, such as willow and corn, improves the removal rate of PAHs. Crucibulum laeve was selected as a representative white rot fungus species. C. laeve strain no. 5.1205 was obtained from the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (Beijing, China), stored at 4 °C, and then pre-cultured at 24 °C on 2% malt extract agar plates for 2 weeks to obtain fresh inoculum. Subsequently, barley seeds were selected as the lignocellulosic substrate carrier. In a 1000 mL conical flask, 72 g of barley seeds and 120 mL of sterile water were autoclaved. Four fungal agar plates were mixed with 80 mL of sterile water (55% v/w), and 40 mL of the fungal inoculum was inoculated into the barley medium and incubated at 24 °C for 4 weeks. Prior to inoculation, the fungal inoculum was placed in a plastic bucket and mixed thoroughly. The dosage of fungal inoculum or barley seeds applied to the contaminated soil was 0.6:10 (w/w).

2.4. Experiment Setup

Remediation of the PAH-contaminated soil was conducted in a greenhouse at Shandong Agriculture and Engineering University under a temperature of 20–30 °C and a 16/8 h light/dark cycle. Uniformly sized polypropylene pots with a total volume of 5 L were used, each containing approximately 5 kg of contaminated soil and cultivated with S. viminalis. Soil without treatment served as the control (CK). The other soil samples were subjected to the following treatments:

(1) N: No fungi were inoculated into the soil, and no fertilizers were added;

(2) MR: Soil was inoculated with C. laeve;

(3) KR: Soil was added with potassium dihydrogen phosphate;

(4) KM: Soil was added with potassium dihydrogen phosphate and inoculated with C. laeve;

(5) CR: Soil was added with calcium phytate;

(6) CM: Soil was added with calcium phytate and inoculated with C. laeve.

Soil moisture was maintained at 60% of field capacity, requiring regular weighing and distilled water addition. The pots were randomly repositioned once a week during the experiment to ensure consistency. On days 0, 15, 30, and 60 of the experiment, five small soil samples were collected from the soil profiles of each treatment by using a spiral soil corer. The soil samples were mixed and sieved through a 2 mm mesh screen. They were then divided into two subsamples: one was stored at 4 °C for testing of soil physical and chemical properties, including soluble organic carbon (SOC), available phosphorus (AP), available potassium (AK), nitrate nitrogen (NO3--N), ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N), and pH; the other was stored at –80 °C for extraction of total soil DNA.

2.5. Determination of Soil Physicochemical Properties

SOC, AP, AK, NO

3--N, NH

4+-N, and pH in the soil samples were determined following the methods described by Bao et al. [

24,

27]. PAH content in the soil samples was analyzed using standard methods published by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. For PAH extraction in soil, 15 g of soil sample was ultrasonically extracted with 30 mL of hexane/acetone (2:1, v/v). The sample purification and detection methods were based on previous studies [

11]. The PAH content in the soil samples was measured using high-performance liquid chromatography as previously described by Xue et al. [

19]. The recovery rate of PHE was 108.3%, which met the standard; thus, no correction was applied to the samples. All PAH concentrations were expressed in terms of sample dry weight.

2.6. Soil DNA Extraction and Illumina NovaSeq Sequencing

Soil total DNA was extracted using the E.Z.N.A. stool DNA Kit (Omega Biotek, Norcross, GA, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted DNA was used for 16S rDNA/ITS high-throughput sequencing. The V3–V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rDNA gene of eukaryotic ribosomal RNA was sequenced using the primer pair 341F/806R (

Table S1); the ITS2 region of the ITS gene of eukaryotic ribosomal RNA was sequenced using the primer pair ITS3_KYO2F and ITS4R (

Table S1). The same reaction system and PCR amplification conditions were used for each primer pair. The 50 μL reaction system contained 5 μL of 10×KOD buffer, 5 μL of 2.5 mM dNTP, 1.5 μL of each forward and reverse primer (5 μM), 1 μL of KOD polymerase, and 100 ng of template DNA. PCR amplification conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 2 min, 27 cycles of 98° C for 10 s, 62 °C for 30 s, and 68 °C for 30 s, and a final extension at 68 °C for 10 min. All samples were amplified in triplicate, with a no-template control included. The PCR products were detected using a 2% agarose gel and purified using the AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen Biosciences, Union City, CA, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantification was performed using QuantiFluor-ST (Promega, USA). The purified PCR products were mixed at equal concentrations and sequenced using the standard procedure on the Illumina platform (2×250).

After obtaining raw data through sequencing, low-quality data were removed through multiple data processing steps, including raw data filtering, tag assembly, tag filtering, and tag de-chimerization. Redundant tag sequences were removed using the Mothur software package to obtain unique tag sequences—representatives of a set of identical tag sequences. Each unique tag represents a varying number of tag sequences, and the number of tags represented by each unique tag is its abundance. The sequence similarity relationships among effective tags were used as a basis to cluster different tags into operational taxonomic units (OTUs). The specific steps are as follows: all effective tag sequences from all samples were clustered using the Uparse software, with a consistency threshold set at 97%. Based on the clustering results, the absolute abundance and relative information of each OTU in each sample were calculated, enabling further analysis of species composition and diversity across samples.

2.7. Data Analyses

One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test (

P < 0.05) were performed using GraphPad Prism 7.0 software. Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) analysis, redundancy analysis, heatmap generation, linear regression analysis, and correlation analysis were conducted using R v.3.1.0 software. Mantel test was employed to assess the correlation and significance between the microbial community distance matrix and the environmental variable distance matrix. Genes associated with PAH degradation were predicted using PICRUSt software. The metagenome was annotated using homology analysis based on the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG,

http://www.kegg.jp/) to obtain predictive information from different databases, and then PAH-related degradation genes were screened from each treatment based on the KEGG database. Co-occurrence network analysis was used to explore the interactions between soil microbial communities during bioremediation. Microbial OTU with total tags number greater than 40 were selected, and Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated between pairs of selected OTU. The threshold was set as Pearson correlation coefficient ρ > 0.7, P < 0.05, to construct the co-occurrence network. Nodes represented the selected OTU, and edges represented the correlation relationships between nodes. The topological structure properties of the network were described using a series of parameters, including node number, edge number, network density, positive/negative correlation, centralize betweenness, mean degree, modularity index. The network diagram was generated using SparCC.

4. Discussion

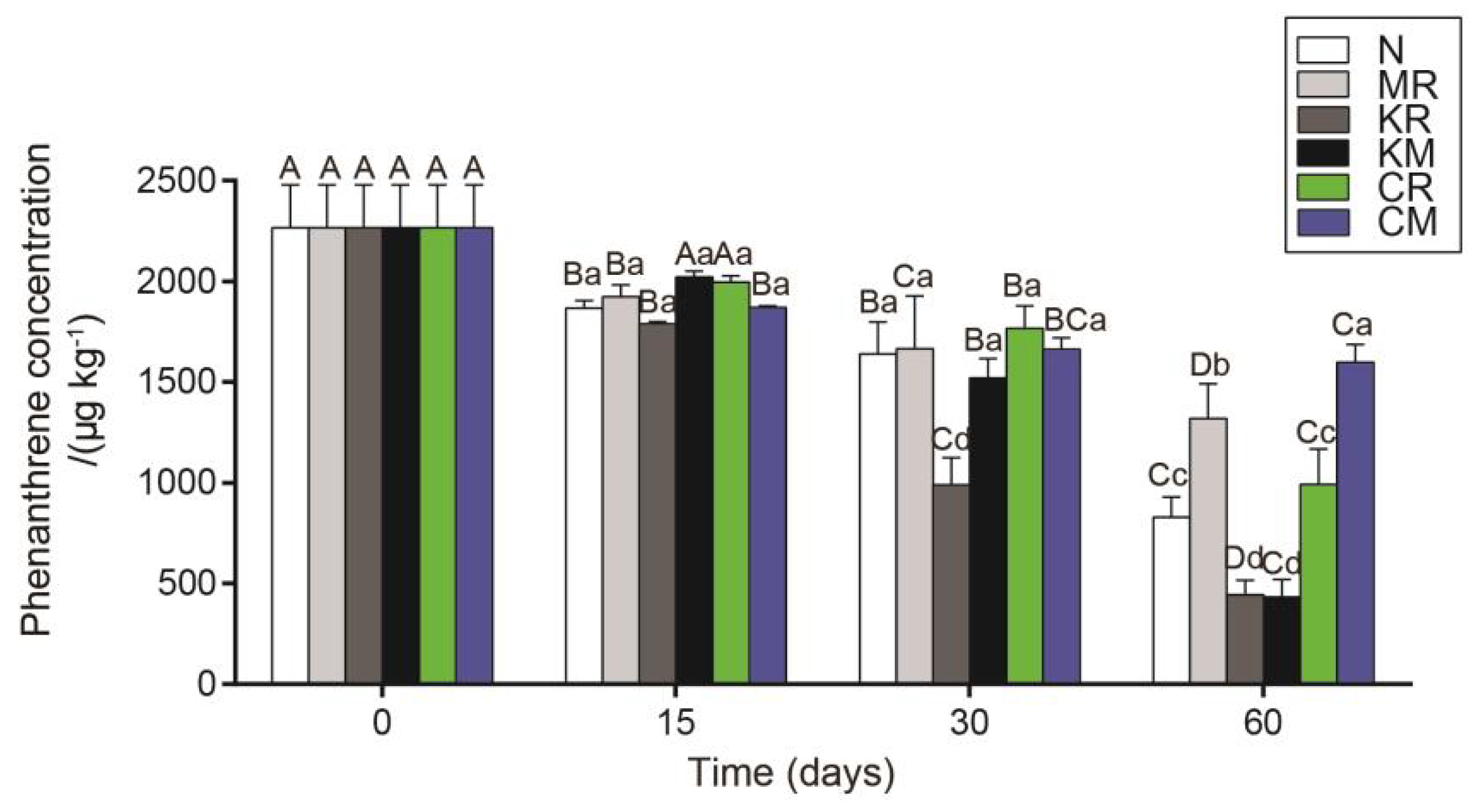

The PHE removal rate under N treatment represents the natural purification capacity of

S. viminalis, a plant species used in phytoremediation, for PAHs [

31]. Overall, the PHE removal rate showed a steady upward trend throughout the remediation process. Multiple studies [

14,

32,

33] demonstrated that

S. viminalis exhibits strong removal capacity for PAHs, including PHE. However, other studies [

9,

12] suggested that other willow species, such as

S. nigra, hinder the microbial degradation of PHE in the rhizosphere due to nutrient competition between plants and rhizospheric microorganisms, thereby reducing PHE removal rates in sediments. Therefore, the species specificity of trees is crucial for PAH removal [

34]. The PAH removal capacity of

S. viminalis in PAH-contaminated soil was weakened after inoculation with

C. laeve. This result agrees with the report of Ma et al. [

14] that

C. laeve exerts a toxic effect on

S. viminalis growth, thereby reducing its ability to remove low-molecular-weight PAHs. Interestingly, in the present study, the removal rates of PHE in the soil samples with the KR and KM treatments were significantly higher than those in the soil samples with the other treatments throughout the experiment, indicating that soluble phosphorus addition significantly enhanced the PHE removal capacity of

S. viminalis, mitigated the toxic effects of

C. laeve on

S. viminalis, and enhanced the synergistic effects between the two. After 30 days of soil cultivation, we detected an extremely strong PHE removal capacity in the KM-treated soil. This result is consistent with previous findings suggesting that phosphorus addition can mitigate fungal toxicity to plants by promoting phosphorus turnover [

20]. By contrast, soluble phosphorus addition (CR and CM treatments) did not significantly affect

C. laeve PHE removal capacity or the antagonistic effect between

S. viminalis and

C. laeve. This result indicates that different phosphorus forms have varying effects on enhancing the restoration efficacy of the plant–white rot fungus symbiotic system. Additionally, compared with the soil samples with N treatment, the soil samples with soluble phosphorus addition treatments showed significantly higher pH, AP, and AK while lower ammonium nitrogen content. The insoluble phosphorus addition treatment significantly improved soil AP, and inoculation with

C. laeve significantly increased nitrate nitrogen in the soil. The above results indicate that adding different phosphorus forms and inoculating fungi may enhance the phytoremediation efficacy of PAH-contaminated soils by altering the structure and function of microbial communities, adjusting soil nutrient cycling, and improving plant nutrient uptake and utilization [

18,

35].

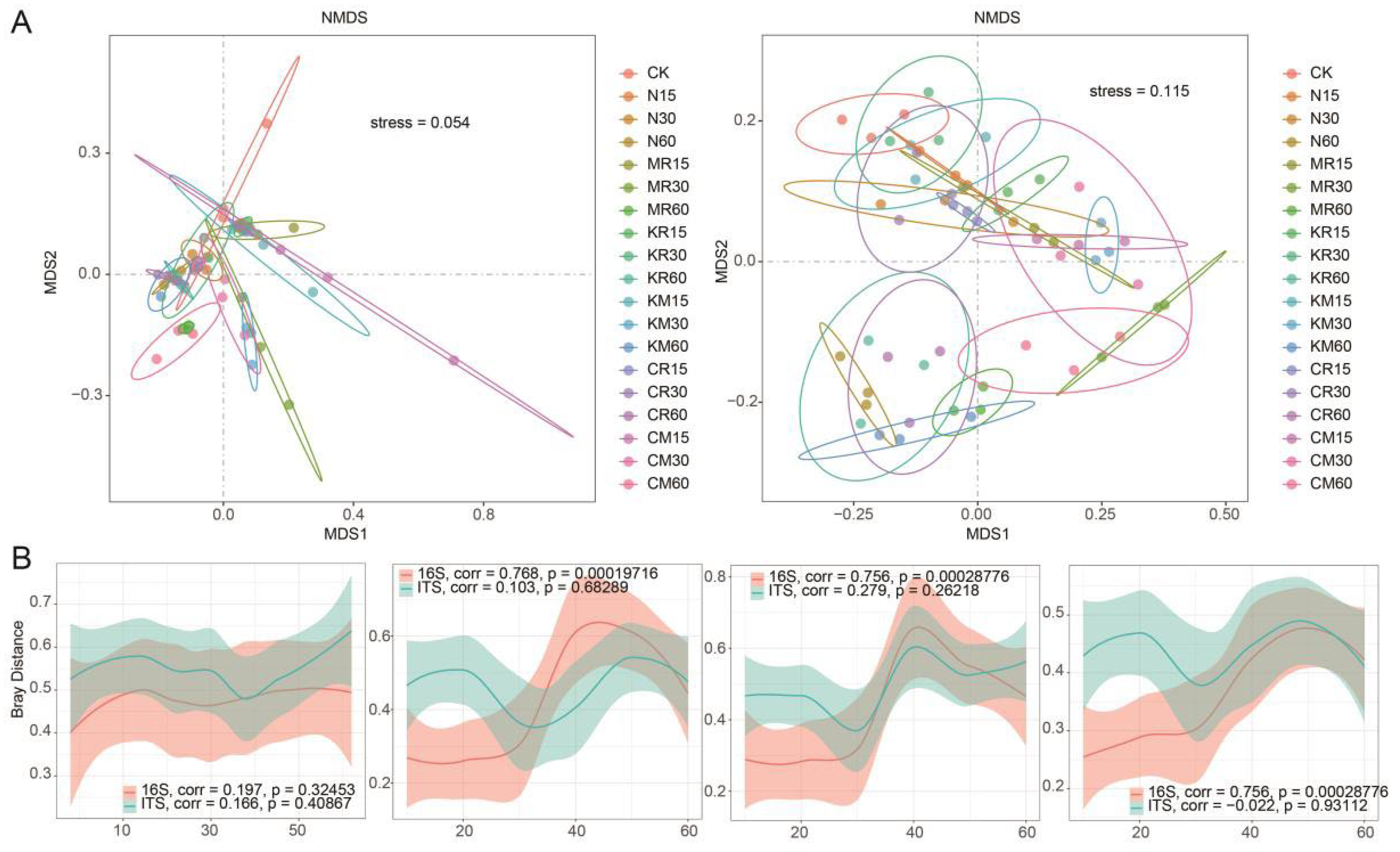

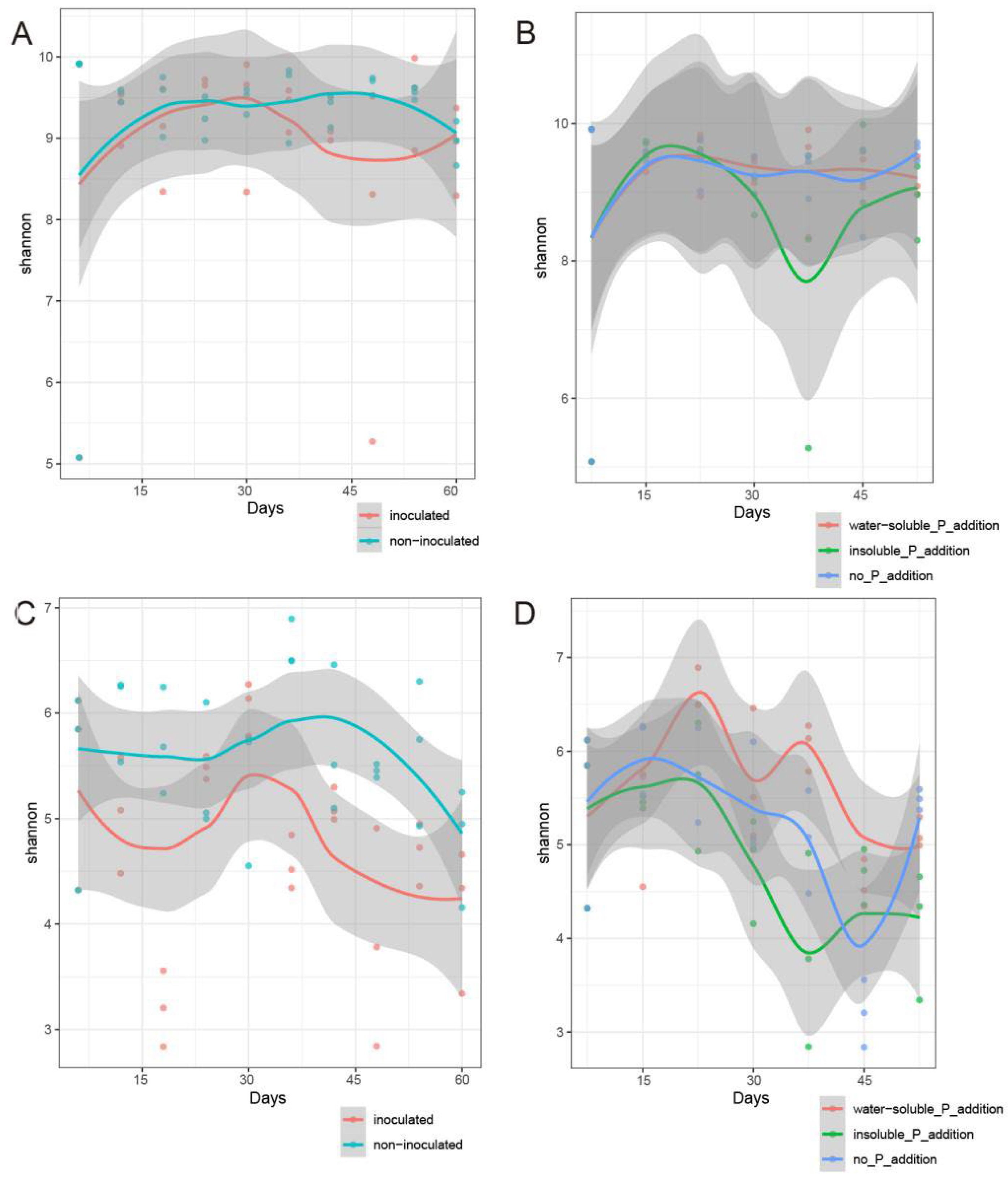

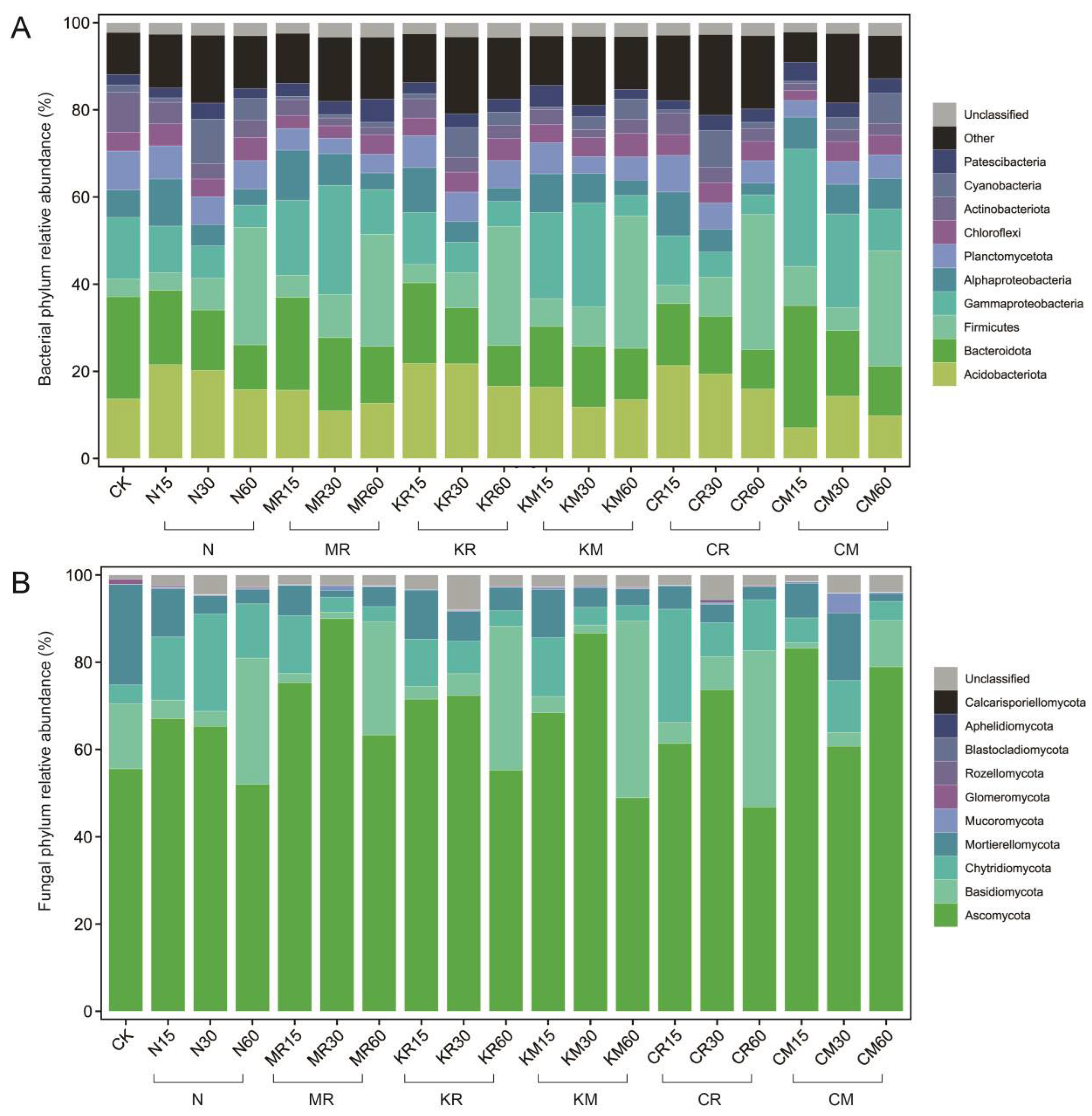

Exogenous organisms and additional nutrients can alter the structure and function of microbial communities in PAH-contaminated soils. A previous study demonstrated that introducing exogenous organisms or adding nutrients can induce bacterial community resilience [

36]. Consistent with this view, the bacterial communities in the present study exhibited resilience patterns after phosphorus addition possibly because of the stable interactions between fungal hyphae and functional groups such as phosphorus-solubilizing bacteria and PAH-degrading bacteria. Under increased phosphorus levels, the abundance of these fungal groups and corresponding microbial groups changes accordingly and recovers to their original levels as phosphorus is consumed [

18,

23]. At the bacterial phylum level (Proteobacteria), inoculation with

C. laeve during the early stages of soil cultivation led to the preferential proliferation of Gammaproteobacteria and Bacteroidetes in the soil bacterial community. These are nutrient-rich bacteria (r-strategists) involved in many important ecological and metabolic processes, such as nutrient cycling and oxidation reactions of various compounds [

21,

37]. At 60 days of soil cultivation, we observed a significant proliferation of K-strategist bacteria such as Firmicutes [

38,

39]. The aforementioned phyla/classes are associated with the degradation of aromatic hydrocarbons [

17,

40]. At the fungal phylum level,

C. laeve promotes the proliferation of Ascomycota in the soil bacterial community, whereas phosphorus addition favors the proliferation of Basidiomycota and other groups. These results highlight the interactive relationships and nutrient preference differences among different fungal groups [

41].

In general, the lower the taxonomic level of microorganisms, the more conservative their ecological functions tend to be [

42]. At the genus level, indigenous PAH-degrading bacteria such as

Pseudomonas are enriched using fungal mycelium as a dispersing carrier [

11,

43]. However,

C. laeve exhibits antagonistic effects on the growth of indigenous PAH-degrading bacteria, such as

Sphingomonas, RB41, and

Lactobacillus, among other indigenous PAH-degrading bacteria. Such antagonistic effects hinder the biodegradation of PAHs [

44]. Phosphorus addition can mitigate this antagonistic effect to some extent depending on the microbial genus.

C. laeve may enhance the plant root absorption of phosphorus in soil by stimulating the activation capacity of phosphorus-solubilizing bacteria toward organic phosphorus, thereby promoting plant association with rhizospheric microorganisms through the secretion of root exudates into the rhizospheric soil and increasing the bioavailability of PAHs, thus facilitating the growth of PAH-degrading bacteria [

18,

22,

45,

46]. The above results indicate the synergistic effect of phosphorus addition and

C. laeve inoculation on the growth of indigenous PAH-degrading bacteria. We also found that

C. laeve inoculation and phosphorus addition increased the abundance of

Fusarium fungi, many of whose members have been associated with PAH degradation capacity [

29,

44]. Furthermore, the relative abundances of

Coprinellus,

Mortierella, and

Humicola were only influenced by phosphorus levels in the soil. These genera are particularly abundant in the rhizospheric soils of plants such as fire phoenix trees and are capable of effectively degrading PAHs [

5].

CCA was applied to investigate the correlation between microbial community structure and environmental factors [

47]. Under different treatment conditions, environmental factors in the soil significantly influenced the composition of microbial communities, and the structural changes in bacterial and fungal communities were generally similar. Based on soil chemical factors such as ammonium nitrogen, the microbial communities in the soil samples with the N and CR treatments could be roughly separated from those in the soil samples with the other treatments by the CCA2 axis (27.2%). Based on environmental factors such as pH, soluble phosphorus, AP, and plant characteristics, the microbial communities in the soil samples with the KR and KM treatments were completely separated from those in the soil samples with the MR and CM treatments by the CCA1 axis (65.03%). Notably, the microbial communities in the soil samples with the CM treatment were completely separated from those in the soil samples with the other treatments and were relatively distant. The above results indicate that the phosphorus cycling functional groups in the indigenous microbial community have limited capacity to utilize insoluble phosphorus; thus, the CR treatment has a less pronounced effect on microbial community structure than the N treatment [

20]. The addition of soluble phosphorus has a direct positive impact on soil pH and AP content, accelerating plant phosphorus absorption and utilization and growth. By releasing more root exudates, it enhances the bioavailability of PAHs and recruits rhizospheric PAH-degrading microbial communities, facilitating the degradation of PHE [

18,

48]. The MR treatment also provides additional nutrients to the soil, primarily in the form of nitrate nitrogen, AK, and SOC, enriching microbial functional groups distinct from those in the KR or KM treatment, thereby resulting in different microbial community structures compared with the latter two [

17]. Therefore, compared with the N or CR treatment, the KR, KM, and MR treatments altered the microbial community composition by influencing soil nutrient content. Interestingly, the CM treatment, which combines

C. laeve and insoluble phosphorus addition, induced a microbial community composition completely distinct from those induced by the other treatments. As previously anticipated, the specialized mycorrhizal microbial communities enriched in the rhizosphere promote soil microbial phosphorus cycling functions, thereby enhancing the activation capacity of organic phosphorus [

18,

45]. Thus, the organic phosphorus stress and dual rhizosphere-mycorrhizal space of the CM treatment shaped a unique microbial community structure and function, but it did not benefit PHE removal within the frame time of the experiment. Previous studies also showed that adding nutrients can enhance the bioavailability of PAHs and promote their biodegradation in soil by enhancing co-metabolic pathways [

49,

50]. In the present study, the addition of soluble phosphorus may benefit PHE biodegradation in soil more than the addition of other forms or types of nutrients.

The abundance and composition of PAH degradation-related genes reflect the intensity of PAH biodegradation. Among the seven high-abundance PAH degradation genes predicted using the PICRUSt software, 3,4-dioxygenase α-subunit of protocatechuic acid (K00449), 3,4-dioxygenase of 3-hydroxy-o-aminobenzoic acid (K00452), 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase (K00457), catechol 4,5-dioxygenase β chain (K04101), and NADP-dependent aldehyde dehydrogenase (K14519) primarily encode bacterial dehydrogenases and dioxygenases. These enzymes, along with salicylic acid hydroxylase (K00480), are key enzymes involved in PAH biodegradation. Catechol is an important substrate for the microbial degradation of PAHs [

17,

51]. The average ratio of the above seven genes is related to the indigenous microbial degradation capacity of PAHs in soil [

3]. At 60 days of soil cultivation, the average ratio of the seven genes in all treatment was higher than that of the treatments at the other time points, indicating that the indigenous microbial community had the strongest PAH biodegradation capacity after 60 days of soil cultivation.

Co-occurrence network analysis is widely used to reveal complex microbial interactions [

52]. In this study, the microbial networks of all six treatments exhibited a “small-world” topological structure formed by interactions among numerous closely connected nodes. Among these, the KR-network exhibited greater nodes number compared to other treatments, but reduced network density and mean degree, indicating simple and loose interactions between microbial communities. This suggests that exogenous phosphorus addition alleviated negative interactions such as competition between the members survived in microbial communities, thereby enhancing beneficial cooperation among them. The MR-network exhibited the highest network density and average degree compared to other treatments, indicating that the selective pressure from allochthonous fungal inoculation strengthened the connections between microbial communities (including degrading bacteria), thereby forming a more complex and compact network. Interestingly, compared to the other three phosphorus addition treatments, the KM-network exhibited the highest network density and mean degree in microbial networks, with the most complex and tightly connected microbial interactions, yet the lowest centralize betweenness and modularity index. Based on the conclusions from CCA, it is speculated that the KM treatment combines the selective pressure of various environmental factors such as the introduction of allochthonous organisms, soil pollutants, and nutrient addition. The rapid proliferation of certain functional groups, such as phosphorus-solubilizing bacteria, within the hyphosphere microbial community may have influenced the co-occurrence patterns among microorganisms in the community [

53]. Therefore, multiple pressures enriched specific microbial groups and formed networks with unique functional and structural characteristics. Therefore, the enhanced phosphorus availability in the

S. viminalis-

C. laeve remediation may strengthen the synergistic effects among degrading microbial communities, which has a positive impact on the biodegradation of PAHs [

54].

Figure 1.

Effect of N, MR, KR, KM, CR and CM treatments on degradation percentage of soil-borne PHE after 0, 15, 30 and 60 days of soil incubation. Means (±SD) were calculated from three replications (n=3) for each treatment and two-way ANOVA was applied. Lowercase letters above the error bars indicate no significant differences between treatments, while uppercase letters indicate no significant differences between different time points within each treatment.

Figure 1.

Effect of N, MR, KR, KM, CR and CM treatments on degradation percentage of soil-borne PHE after 0, 15, 30 and 60 days of soil incubation. Means (±SD) were calculated from three replications (n=3) for each treatment and two-way ANOVA was applied. Lowercase letters above the error bars indicate no significant differences between treatments, while uppercase letters indicate no significant differences between different time points within each treatment.

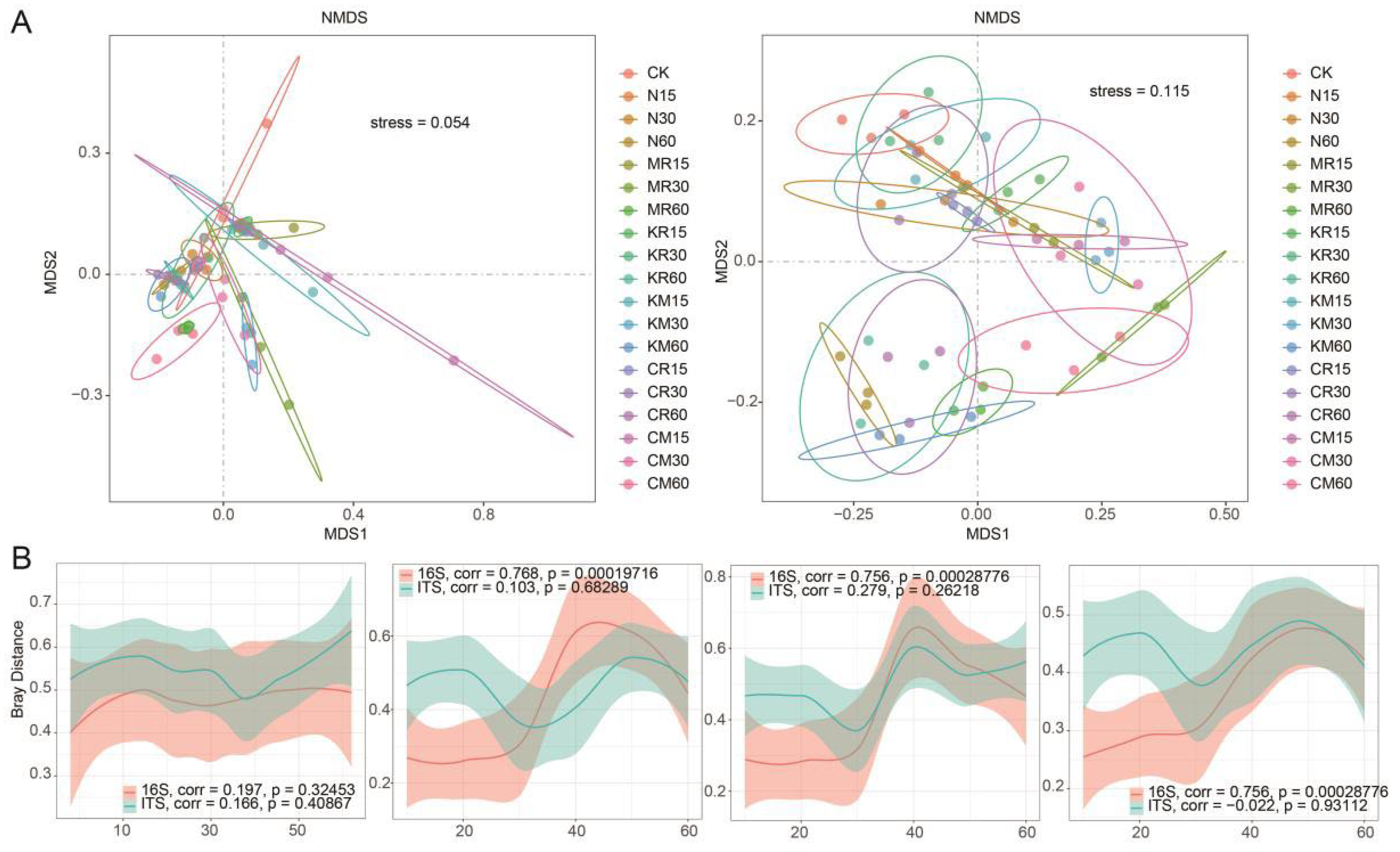

Figure 2.

Overall pattern of microbial community β-diversity among treatments. (A) Clustering of microbial diversity in samples from each treatment based on Bray-Curtis distance NMDS (left 16S and right ITS), with 80% confidence ellipses enclosing each treatment at different time points. (B) Patterns of inter-sample differences in microbial communities (16S and ITS) during the succession process caused by fungi under uninoculated and inoculated smooth white egg nest fungus conditions; patterns of inter-sample differences in microbial communities (16S and ITS) during the succession process caused by soluble phosphorus under phosphorus-free and soluble phosphorus addition conditions; patterns of inter-sample differences in microbial communities (16S and ITS) during the succession process caused by insoluble phosphorus under phosphorus-free and insoluble phosphorus addition conditions under insoluble phosphorus addition; and the patterns of inter-sample differences in microbial communities (16S and ITS) during succession processes caused by different phosphorus forms under soluble phosphorus addition and insoluble phosphorus addition. Points represent individual samples, trend lines are smoothed moving averages of means, and shaded areas indicate standard errors.

Figure 2.

Overall pattern of microbial community β-diversity among treatments. (A) Clustering of microbial diversity in samples from each treatment based on Bray-Curtis distance NMDS (left 16S and right ITS), with 80% confidence ellipses enclosing each treatment at different time points. (B) Patterns of inter-sample differences in microbial communities (16S and ITS) during the succession process caused by fungi under uninoculated and inoculated smooth white egg nest fungus conditions; patterns of inter-sample differences in microbial communities (16S and ITS) during the succession process caused by soluble phosphorus under phosphorus-free and soluble phosphorus addition conditions; patterns of inter-sample differences in microbial communities (16S and ITS) during the succession process caused by insoluble phosphorus under phosphorus-free and insoluble phosphorus addition conditions under insoluble phosphorus addition; and the patterns of inter-sample differences in microbial communities (16S and ITS) during succession processes caused by different phosphorus forms under soluble phosphorus addition and insoluble phosphorus addition. Points represent individual samples, trend lines are smoothed moving averages of means, and shaded areas indicate standard errors.

Figure 3.

Changes in the Shannon index of bacterial (A) and fungal (C) communities in PAH-contaminated soil under inoculated and non-inoculated C. laeve treatments over time; changes in the Shannon index of bacterial (B) and fungal (D) communities in PAH-contaminated soil under water-soluble phosphorus addition, insoluble phosphorus addition, and no phosphorus addition treatments over time.

Figure 3.

Changes in the Shannon index of bacterial (A) and fungal (C) communities in PAH-contaminated soil under inoculated and non-inoculated C. laeve treatments over time; changes in the Shannon index of bacterial (B) and fungal (D) communities in PAH-contaminated soil under water-soluble phosphorus addition, insoluble phosphorus addition, and no phosphorus addition treatments over time.

Figure 4.

Changes in the relative abundance of bacteria (classes of Proteobacteria) (A) and fungi (B) at the phylum level during the succession of microbial communities in PAH-contaminated soil under different treatments.

Figure 4.

Changes in the relative abundance of bacteria (classes of Proteobacteria) (A) and fungi (B) at the phylum level during the succession of microbial communities in PAH-contaminated soil under different treatments.

Figure 5.

Changes in the relative abundance of selected microbial genera during the succession of microbial communities in PAH-contaminated soils under different treatments. The trend lines are smoothed moving averages of the means.

Figure 5.

Changes in the relative abundance of selected microbial genera during the succession of microbial communities in PAH-contaminated soils under different treatments. The trend lines are smoothed moving averages of the means.

Figure 6.

Redundancy analysis (CCA) of the relationship between microbial communities and environmental factors in PAH-contaminated soil under different treatments (day 60).

Figure 6.

Redundancy analysis (CCA) of the relationship between microbial communities and environmental factors in PAH-contaminated soil under different treatments (day 60).

Figure 7.

Predictions based on PICRUSt software: Changes in microbial function during 60 days of soil incubation under different treatments.

Figure 7.

Predictions based on PICRUSt software: Changes in microbial function during 60 days of soil incubation under different treatments.

Figure 8.

Correlation coefficients (r) between microbial communities, PAH removal rates, and functional genes in PAH-contaminated soils under different treatments.

Figure 8.

Correlation coefficients (r) between microbial communities, PAH removal rates, and functional genes in PAH-contaminated soils under different treatments.

Figure 9.

Co-occurrence network diagram at the OTU level. ○represents 16S nodes, □represents ITS nodes.

Figure 9.

Co-occurrence network diagram at the OTU level. ○represents 16S nodes, □represents ITS nodes.

Table 1.

Effect of each treatment on soil physical and chemical properties (on day 60).

Table 1.

Effect of each treatment on soil physical and chemical properties (on day 60).

| Treatment |

pH |

NO3−-N

(mg·kg-1) |

NH4+-N

(mg·kg-1) |

AK

(mg·kg-1) |

AP

(mg·kg-1) |

SOC

(%) |

| N |

7.53±0.09b |

13.47±0.67c |

11.83±0.21a |

205.70±10.02e |

4.07±0.19c |

44±0.05a |

| MR |

7.73±0.06ab |

50.73±1.50b |

5.38±0.04c |

338.70±5.13bc |

4.04±0.19c |

49.33±0.03a |

| KR |

7.99±0.06a |

5.68±0.19d |

4.59±0.19d |

321.30±2.51c |

18.67±1.50a |

52.67±0.09a |

| KM |

7.93±0.07a |

47.87±1.47b |

3.78±0.07e |

386.30±9.71ab |

17.93±0.90a |

43.33±0.02a |

| CR |

7.83±0.11ab |

14.57±0.76c |

6.66±0.20b |

245.30±8.62d |

9.84±0.14b |

43.67±0.06a |

| CM |

7.75±0.07ab |

74.97±1.17a |

5.1±0.25c |

430.30±46.61a |

8.47±0.19b |

52.67±0.08a |

Table 2.

Topological characteristics of each treatment network diagram.

Table 2.

Topological characteristics of each treatment network diagram.

| Treatment |

Node |

Edge |

Network density |

Positive

correlation |

Negative

correlation |

Centralize betweenness |

Mean degree |

Modularity |

| N |

806 |

8257 |

0.025 |

0.474 |

0.526 |

0.035 |

20.489 |

0.096 |

| MR |

670 |

9756 |

0.044 |

0.450 |

0.550 |

0.043 |

29.122 |

0.121 |

| KR |

848 |

7580 |

0.021 |

0.453 |

0.547 |

0.046 |

17.877 |

0.165 |

| KM |

734 |

7623 |

0.028 |

0.336 |

0.664 |

0.041 |

20.771 |

0.193 |

| CR |

788 |

7947 |

0.026 |

0.427 |

0.573 |

0.051 |

20.170 |

0.214 |

| CM |

603 |

7333 |

0.040 |

0.388 |

0.612 |

0.033 |

24.322 |

0.095 |