1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning techniques, has led to significant advancements in numerous fields, including veterinary medicine, human medicine, and forensic sciences in recent years. Deep learning architectures such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have been successfully applied in medical imaging with high accuracy, contributing to fracture detection, organ segmentation, and tumor classification (Kim & MacKinnon, 2018; Prasson et al., 2013). In veterinary medicine, AI-based systems have begun to be used for the analysis of radiographic images, enabling fracture diagnosis, abnormality detection, and early identification of certain internal diseases (BulutVet, 2023; Zoetis Diagnostics, 2023).

Emerging technologies such as augmented reality (AR) have been shown to enrich anatomical education by offering interactive and spatially intuitive experiences. Jiang et al. (2024) developed an AR-based canine skull model that effectively supported veterinary students' learning without compromising comprehension when compared to traditional methods.

However, the use of AI in the classification and automated identification of animal bones remains limited. Most existing studies have focused on human medicine, often addressing deformation analysis of human bones (Garvin et al., 2023). In studies concerning animal bones, research has predominantly centered on fracture analysis via tomographic imaging, with few efforts devoted to direct species identification or anatomical bone classification (Brett et al., 2009). Some local studies on the classification of long bones in dogs have demonstrated the potential of AI in this field (Yıldız et al., 2020); nonetheless, a comprehensive osteological classification system based on a multi-species dataset is lacking in the literature.

The emergence of conversational AI tools such as ChatGPT has opened new horizons for interactive learning in veterinary anatomy, providing instant explanatory feedback to students (Choudhary et al., 2023). These chatbots have been shown to enhance anatomical knowledge retention while highlighting the continuing importance of hands-on dissection practices.

Recent developments in deep learning have led to significant improvements in bone detection and classification tasks, particularly through the use of YOLO-based object detection algorithms. Tariq and Choi (2025) demonstrated that an enhanced YOLO11 architecture could detect and localize wrist fractures in X-ray images with high precision, underscoring the diagnostic power of real-time convolutional networks in skeletal image analysis.

In veterinary anatomical education, osteology holds critical importance for enabling students to learn bone structures and species-specific anatomical features. However, limitations in hands-on laboratory instruction and the dependency on instructor availability may hinder the learning process. It has been reported that receiving real-time feedback can improve retention in learning by up to 40% (Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006). AI-supported mobile applications address this need by promoting individualized learning and facilitating digital transformation in educational environments (Pires et al., 2018; Mayfield et al., 2013).

The proliferation of mobile applications in anatomy education has opened new avenues for student engagement; however, the pedagogical rigor and scientific credibility of these tools vary widely. Rivera García et al. (2025) emphasized that while many anatomy apps are popular, few are developed within academic contexts or validated through structured evaluation methods.

The integration of mobile platforms into anatomical education has gained traction due to their accessibility and potential for self-directed learning. Little et al. (2021) developed a canine musculoskeletal anatomy app that was well-received by veterinary students, highlighting the feasibility and effectiveness of mobile-based anatomical instruction in species-specific contexts.

Recent advancements in computer vision have led to the development of cloud-based web applications such as ShinyAnimalCV, which facilitate object detection, segmentation, and 3D visualization of animal data (Wang et al., 2023). This tool integrates pre-trained vision models and user-friendly interfaces to democratize access to image analysis methods for educators and students alike.

The growing use of mobile applications in human anatomy education has prompted critical evaluations of their pedagogical effectiveness. Rivera García et al. (2025) emphasize that while such apps enhance accessibility, their anatomical accuracy and scientific validation often remain questionable.

Recent large-scale studies have shown that screen-based 3D and augmented reality tools can significantly improve student engagement and learning experience in anatomy education (Barmaki et al., 2023). These tools provide spatial understanding and interactivity, which are especially useful in visual-heavy disciplines like anatomy.

Latest developments in veterinary imaging have adopted self-supervised AI methods, such as the VET-DINO framework, to enhance anatomical understanding from radiographic datasets (Dourson et al., 2025). These models demonstrate the capacity of AI to capture nuanced anatomical features even without human-labeled training data.

In disciplines such as forensic science, archaeology, and crime scene investigation, the rapid and accurate determination of whether a bone belongs to a human or an animal is of paramount importance. However, the absence of experts in field situations can delay the process and increase the likelihood of errors (Saulsman, 2010; Huffman & Wallace, 2012). In such cases, AI-based systems may serve as supportive tools that augment expert decision-making without replacing human specialists.

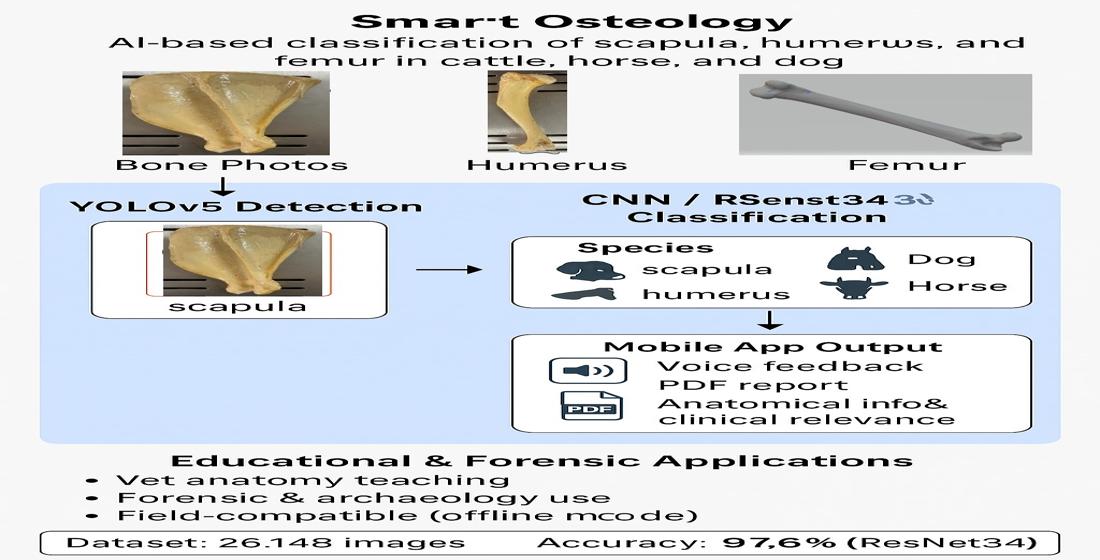

The aim of this study was to train an artificial intelligence system using image processing methods to recognize the scapula, humerus, and femur bones of cattle, horses, and dogs, and to evaluate the system’s performance in identifying these bones through a custom-developed application.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Collection

In this study, the scapula, humerus, and femur bones belonging to cattle (Bos taurus), horses (Equus caballus), and dogs (Canis familiaris) were utilized. The bone images were obtained from specimens available in the Anatomy Laboratory of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at Erciyes University, as well as from open-access online sources. A total of 26,148 bone images were collected. Of these, 24,700 images were used for training and testing the model, while the remaining images were reserved for external validation.

All images were captured at 720p resolution and were subsequently cleaned to remove outliers. Care was taken to balance the dataset according to bone type and species. To enhance model performance and generalizability, data augmentation techniques such as brightness adjustment, rotation, cropping, and horizontal flipping were applied.

2.2. Image Processing and Annotation

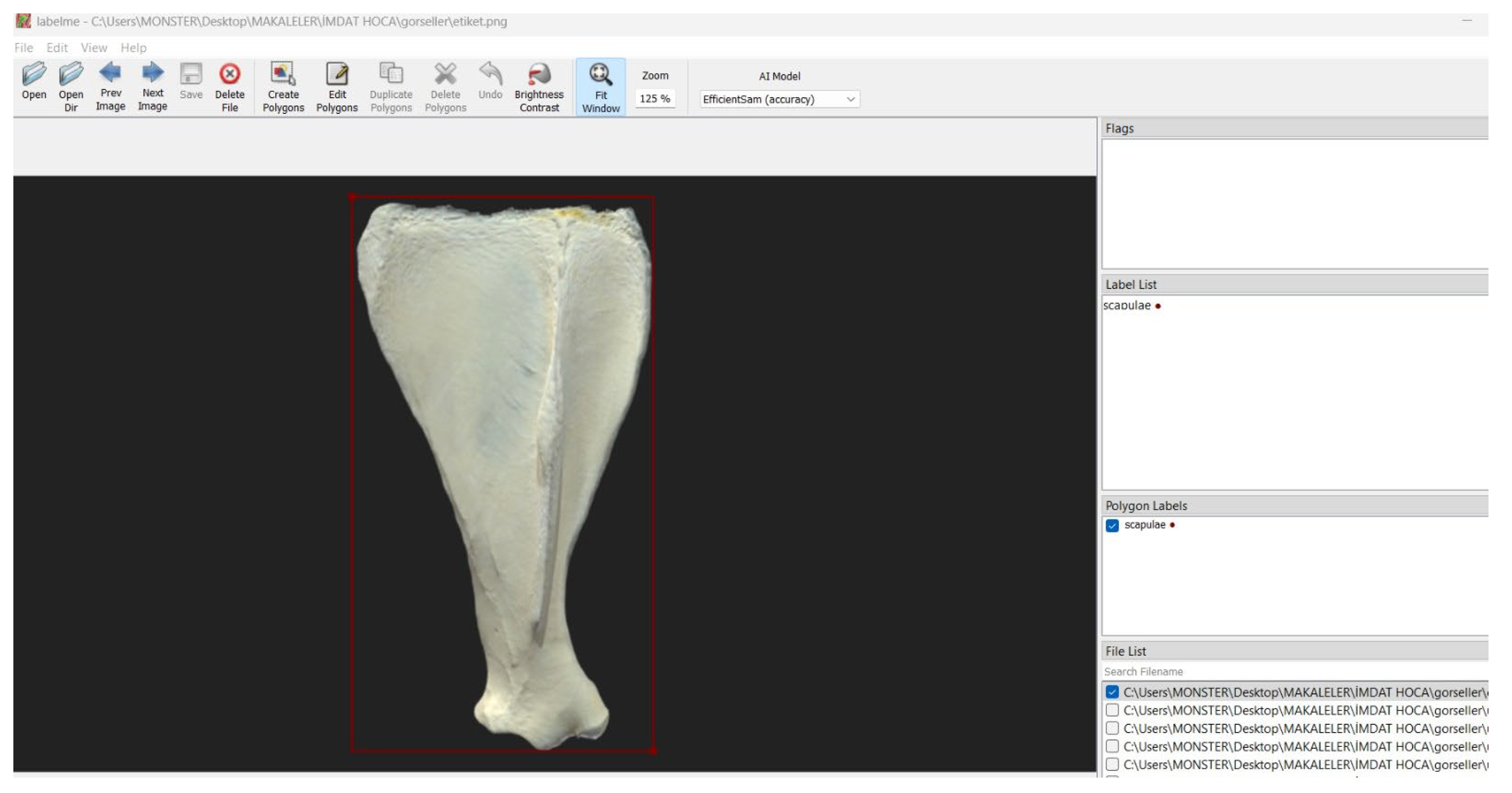

The bone images were initially processed using the YOLOv5 algorithm, which automatically detected the relevant regions of interest. For the annotation process, the Labelme platform was utilized (

Figure 1), and distinct anatomical features of each bone (e.g.,

processus hamatus) were manually marked. The annotated data were exported in COCO JSON format for further use.

2.3. Deep Learning Architecture and Model Training

The dataset was divided into three subsets: training (85%), testing (10%), and validation (5%). Model training was conducted using the Python programming language and the PyTorch framework. In the initial stage, bone detection was performed using the YOLO algorithm. Subsequently, bone name and species classification were carried out using CNN and ResNet34 architectures. The training process lasted approximately seven hours in total.

2.4. Model Evaluation

The model’s performance was evaluated not only based on accuracy but also using precision, recall, and F1-score metrics. These metrics provided more reliable insights, particularly in the context of imbalanced datasets. To account for variations in sample size among species, class-weighted F1-scores were calculated. Additionally, the model’s accuracy was assessed using an independent test dataset.

2.5. Student Surveys

The surveys included questions related to the study topic, a brief section providing information about the research, participants’ feedback on learning outcomes after using the application, and informed voluntary consent forms. The data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows 22.0 statistical software. Statistical analyses were conducted using the Pearson Chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, Mann–Whitney U test, and Spearman’s correlation analysis. P< 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Operational Workflow of the Mobile Application

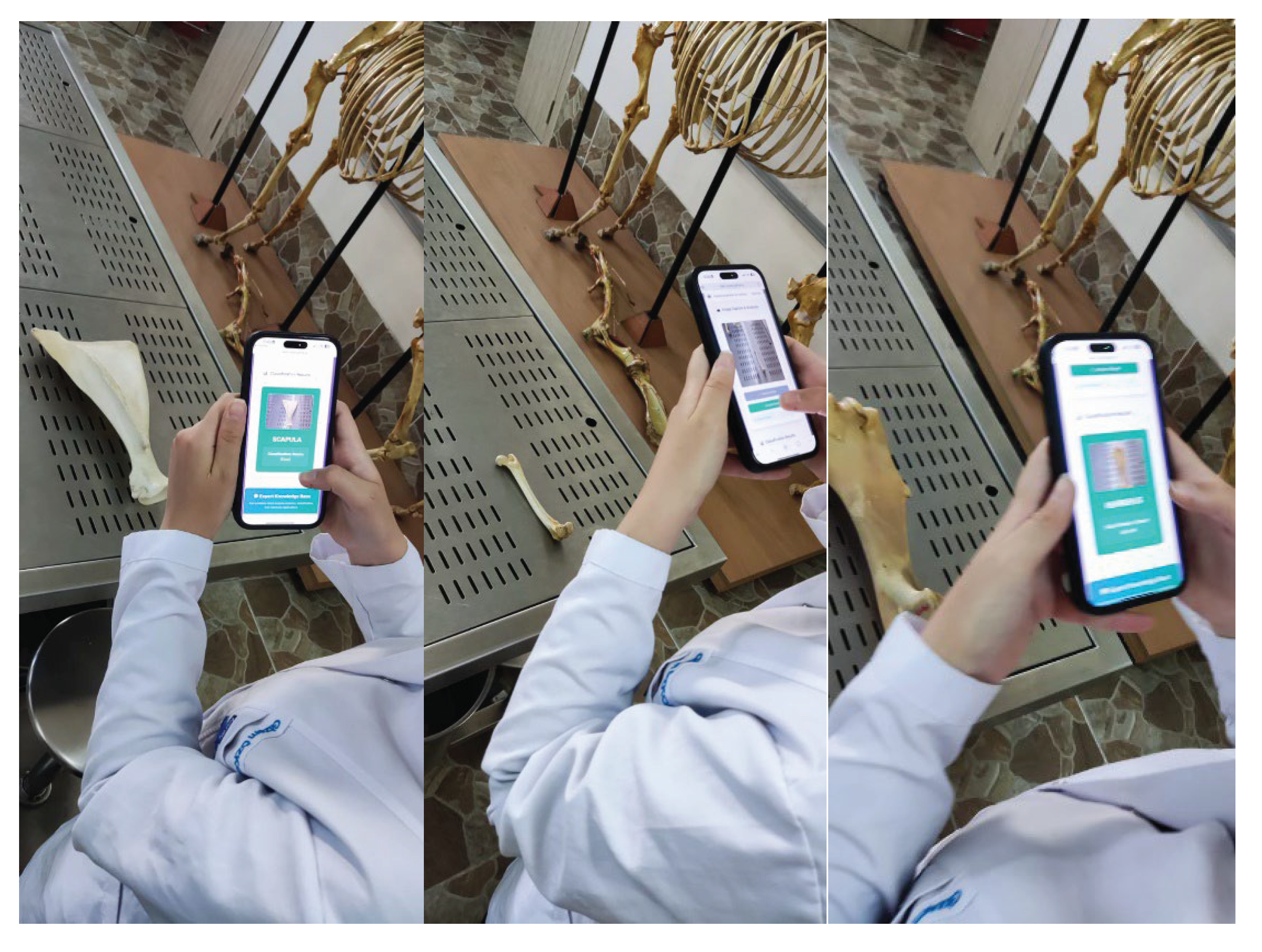

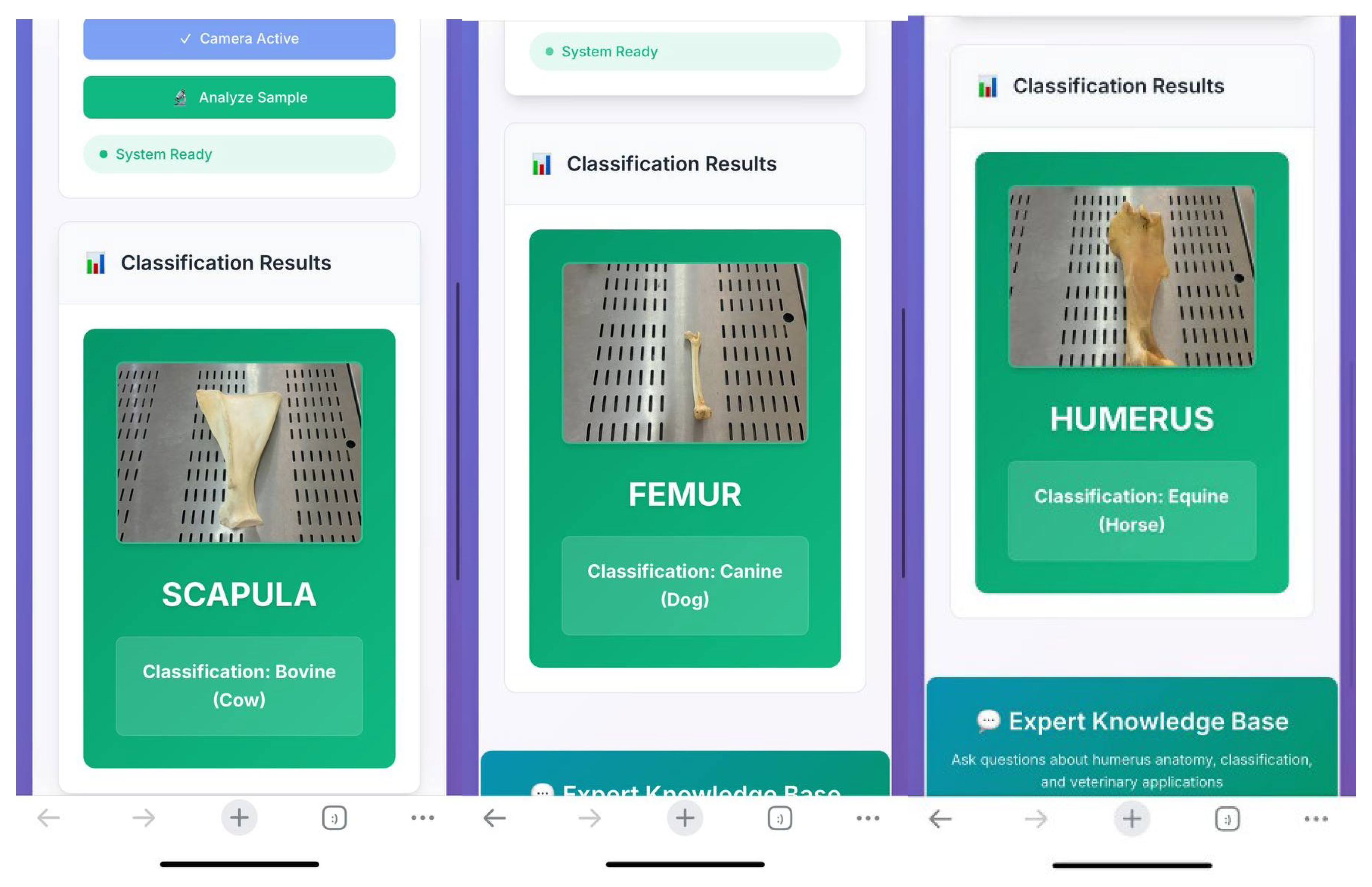

The trained system was used by students in the laboratory setting (

Figure 2). Through a web link accessible via mobile phones, students uploaded photographs of bones, which were then rapidly analyzed by the system (

Figure 3).

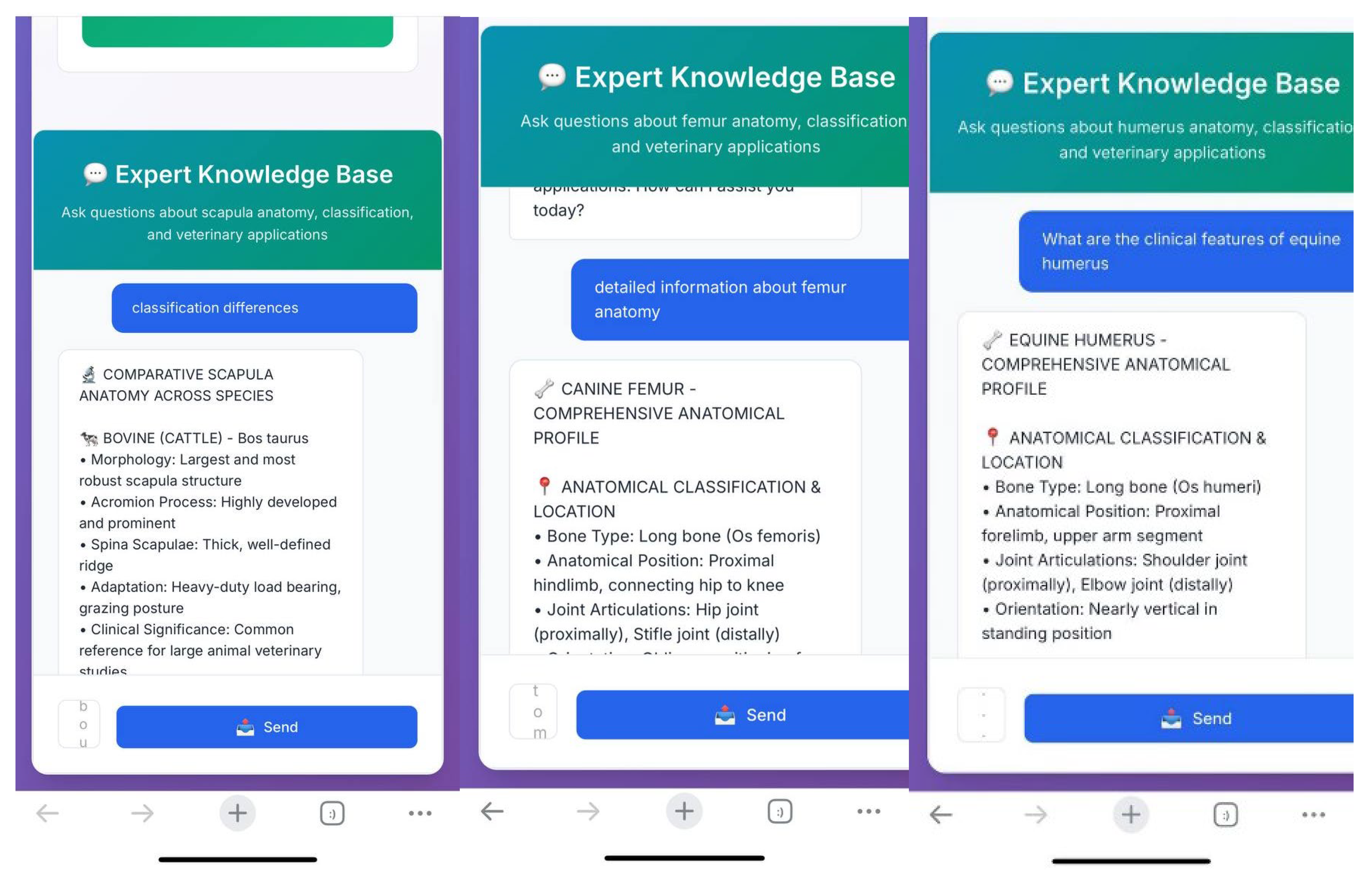

Following the analysis, the integrated quick-response system enabled access to additional information regarding the identified bone. Students were able to obtain answers to various questions such as detailed anatomical features of the detected bone, interspecies differences, and the clinical anatomical relevance of the region with pdf format and voice answer (

Figure 4).

3.2. Model Performance Comparison

Among the various deep learning architectures trained in this study, the highest classification accuracy was achieved with the ResNet34 model, reaching 97.6%. The alternatively developed SmallCNN architecture achieved an accuracy of 95%. These results indicate that more complex architectures tend to yield higher classification performance (

Table 1).

In terms of bone types, the system demonstrated higher accuracy in recognizing larger bones such as the scapula and femur. This suggests that the model was able to distinguish these structures more easily due to their prominent morphological features.

In mobile phone–based applications, the system successfully identified the species of the bones. Notably, it was also able to correctly recognize bones that were not included in the training dataset, demonstrating its ability to generalize to previously unseen samples.

3.3. User Experience and Survey Results

The prototype of the developed mobile application was tested by a total of 45 students at Erciyes University. In the post-test survey, 98% of the participants rated the application as either “useful” or “very useful.”

Table 2.

Student satisfaction survey results.

Table 2.

Student satisfaction survey results.

| Survey Question |

Positive Response (%) |

| The application was easy to use |

96.4 |

| Voice and text-based queries functioned accurately enough. |

95.1 |

| The application's presentation of anatomical information was satisfactory. |

97.7 |

| The PDF export feature was useful. |

94.2 |

| I was satisfied with the overall performance of the application. |

98.0 |

Other prominent satisfaction factors identified in the survey results can be summarized as follows:

Ease of Use: The majority of participants stated that the application was extremely easy to use.

Query Accuracy: The voice and text-based search functions were reported to have worked accurately as expected.

Information Delivery: The anatomical content provided by the application was found to be satisfactory by the students.

Export Features: The ability to generate PDF reports was considered another useful feature by the users.

Overall, these feedback results indicate that the application is user-friendly and can positively contribute to the educational process. The high satisfaction rates reported by students suggest that the system is a valuable tool both for learning purposes and for practical applications.

4. Discussion

The deep learning-based bone classification system developed in this study demonstrated high accuracy in identifying both bone type and the corresponding animal species. The achieved accuracy rate of 97.6% represents a superior performance compared to previous studies conducted on human bones (Kim & MacKinnon, 2018; Garvin et al., 2023). In particular, the performance attained with the ResNet34 architecture exceeds the commonly reported accuracy range of 90–95% in the literature (Saulsman, 2010; Yıldız et al., 2020).

Existing systems in the literature typically focus solely on human bone analysis and do not address interspecies comparative classification. Although projects such as OsteoID have reported high accuracy, these systems were usually tested on a limited number of species and did not provide publicly accessible datasets (Garvin et al., 2023). In contrast, the use of a large and diverse dataset comprising bones from different species in the present study enhanced the model’s robustness in real-world applications, where a wide variety of samples may be encountered.

In our study, the implementation of YOLOv5 for detecting bone regions prior to classification builds on this principle, offering reliable and fast identification of anatomical structures from photographs. Similar to the success achieved by Tariq and Choi (2025) in clinical radiology, our findings confirm that modern YOLO-based models are highly suitable for veterinary osteological applications where accurate localization is essential.

The 98% satisfaction rate obtained from student surveys further highlights the educational potential of the system. Previous studies, such as those by Mayfield et al. (2013), have shown that mobile technologies can effectively support anatomical education. This study not only reinforces those findings but also demonstrates the potential of creating active learning environments that support individualized learning.

Echoing the insights of Choudhary et al. (2023), our system embraces AI-assisted feedback by delivering written and spoken anatomical explanations, yet it augments this with image-based bone identification to provide multimodal educational support. By balancing automated instruction with practical application, Smart Osteology addresses both the engagement benefits and limitations of virtual assistants noted by Choudhary et al.

Our mobile application responds directly to the concerns raised in this review by providing a scientifically grounded, academically developed system with demonstrable accuracy and user satisfaction. Unlike many commercially produced tools, our app was purpose-built for veterinary anatomical education and forensic support, bridging the gap between innovation and pedagogical reliability as advocated by Rivera García et al. (2025).

While Little et al. (2021) successfully demonstrated the educational benefits of a mobile application focused on canine anatomy, the current study extends this concept by incorporating deep learning models to enable automated identification across multiple species and bone types. This advancement not only supports individual learning but also introduces diagnostic and forensic utility, marking a significant evolution in mobile-assisted anatomy education.

Our mobile system extends this concept beyond livestock farming applications by enabling offline bone classification for multiple species directly from device cameras, without the need for internet or cloud infrastructure. While ShinyAnimalCV demonstrates the utility of web-based platforms in academic settings, Smart Osteology prioritizes field-readiness and data privacy through a locally executable, AI-powered app.

While our current system does not yet integrate AR technology, it shares the same goal of enhancing anatomy education through accessible, student-centered digital tools. In line with Jiang et al. (2024), our approach also prioritizes learner engagement and real-world usability—especially by providing portable, offline functionality and intelligent anatomical feedback.

Unlike many commercially available anatomy apps, our AI-based system was trained on verified anatomical data and rigorously evaluated, ensuring content reliability. This adds scientific value and bridges the gap noted in Rivera García et al.'s assessment of unregulated mobile tools.

While our application does not utilize 3D or augmented reality technologies, it offers interactivity through real-time image analysis, speech-based queries, and dynamic feedback. These features align with the educational benefits highlighted by Barmaki et al. (2023), who emphasized that screen-based tools significantly improve student engagement and spatial understanding in anatomy learning.

Our supervised deep learning model, based on photographic datasets, offers a more accessible approach for veterinary anatomy education compared to radiographic imaging. However, the potential advantages of multi-view or self-supervised frameworks, as demonstrated by Dourson et al. (2025) in their VET-DINO study, highlight possible directions for enhancing model robustness and versatility in future work.

5. Conclusions

This study successfully demonstrated the applicability of deep learning techniques in classifying certain long bones from selected domestic animal species. Bone detection was performed using the YOLO algorithm, and species and bone name classification were achieved with high accuracy through CNN and ResNet34 architectures. The obtained accuracy rate of 97.6% confirms that the developed system is a reliable tool for both educational and forensic purposes.

As a preliminary study, this work offers a novel and versatile digital solution applicable to fields such as veterinary anatomy education, forensic science, archaeology, and biological anthropology. Future studies aim to expand the scope of the system by increasing the diversity of bone types and animal species, comparing various AI architectures, and integrating interactive technologies such as augmented reality. Additionally, to enhance field applicability, it is planned to further refine user interfaces and establish collaborations with official institutions to develop modules tailored to specific needs.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Permission

"All materials reproduced from other sources in this publication are used with permission. Appropriate credit has been given to the original sources where applicable."

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

References

- Barmaki, R., Chen, J., & Patel, V. L. (2023). Large-scale feasibility study of screen-based 3D and AR tools in anatomy instruction. Medical Education Research International, 41(3), 209–217. [CrossRef]

- Brett, A., Ching, M., & Lam, E. (2009). Skeletal segmentation and classification in pigs using artificial neural networks. Journal of Veterinary Radiology, 50(3), 123–130.

- BulutVet. (2023). The use of artificial intelligence in veterinary medicine. https://bulutvet.com/blog/veteriner-hekimlikte-yapay-zekanin-kullanimi.

- Choudhary, O. P., Saini, J., & Challana, A. (2023). ChatGPT for veterinary anatomy education: An overview of the prospects and drawbacks. International Journal of Morphology, 41(4), 1198–1202.

- Dourson, M., He, Y., & Hammer, S. (2025). VET-DINO: Multi-view learning enhances AI interpretation of veterinary radiographs. Veterinary Artificial Intelligence, 3(1), 22–36. [CrossRef]

- Garvin, H., Green, R., & Schmitt, S. (2023). OsteoID: A new forensic tool to help identify the species of skeletal remains. National Institute of Justice. https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/osteoid.

- Huffman, J. E., & Wallace, J. R. (2012). Wildlife forensics: Methods and applications. John Wiley & Sons.

- Jiang, L., Tang, Y., & Zhou, Q. (2024). Development and evaluation of an AR-based canine skull anatomy learning tool for veterinary students. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 51(2), 198–207. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D. H., & MacKinnon, T. (2018). Artificial intelligence in fracture detection: Transfer learning using Inception V3. Radiology: Artificial Intelligence, 1(1), e180010.

- Little, C. J., Bröker, L. E., Hennessey, M. A., Hodgson, D. R., & Dart, A. J. (2021). Development and usability testing of a mobile app for learning canine musculoskeletal anatomy. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 48(4), 460–468. [CrossRef]

- Mayfield, C. H., Ohara, P. T., & O’Sullivan, P. S. (2013). Perceptions of a mobile technology on learning strategies in the anatomy laboratory. Anatomical Sciences Education, 6(2), 81–89.

- Nicol, D. J., & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199–218.

- Pires, L., Leite, T., Júnior, A., Babinski, M., & Chagas, C. A. (2018). Anatomical apps and smartphones: A pilot study with 100 graduation students. SM Journal of Clinical Anatomy, 2(1), 1007.

- Prasson, A., Tsai, M. C., & Liao, W. C. (2013). Detection of skeletal abnormalities using deep convolutional neural networks. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 43(12), 2066–2074.

- Rivera García, E., Muñoz-Rodríguez, J. M., & Cordero, C. A. (2025). Systematic review of mobile applications used for anatomy learning based on MARS criteria. Anatomical Sciences Education, 18(1), 14–29. [CrossRef]

- Rivera García, C., Palacios, G. M., Isern-Fortuny, J., & González, J. (2025). Reviewing mobile apps for teaching human anatomy: A need for evidence-based content. Journal of Medical Education Technology, 34(2), 87–94. [CrossRef]

- Saulsman, B. (2010). Long bone morphometrics for human from non-human discrimination (Master’s thesis, University of Western Australia).

- Tariq, A., & Choi, H. (2025). YOLO11-driven deep learning approach for enhanced detection and visualization of wrist fractures in X-ray images. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 163, 107419. [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, M., Demir, F., & Kara, Y. (2020). Classification of long bones in dogs using convolutional neural networks. Veteriner Bilimleri Dergisi, 36(3), 234–240.

- Wang, J., Hu, Y., Xiang, L., Morota, G., Brooks, S. A., Wickens, C. L., Miller-Cushon, E. K., & Yu, H. (2023). Technical note: ShinyAnimalCV: Open-source cloud-based web application for object detection, segmentation, and three-dimensional visualization of animals using computer vision. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.14487.

- Zoetis Diagnostics. (2023). Bringing the power of artificial intelligence to the world of diagnostics. https://www.zoetisdiagnostics.com/tr/virtual-laboratory/artificial-intelligence.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).