1. Introduction

During adolescence, the development of visuomotor skills, such as the coordination between what is seen and how one reacts, is key for functional performance in school, sports, and daily activities. However, factors such as sedentary behavior, excessive screen time, and limited physical stimulation are contributing to the progressive deterioration of these abilities in young people, especially in school settings in Latin America. This situation represents a growing public health challenge, since visuomotor deficits affect not only motor performance but also cognitive processes, such as attention, planning, and postural control [

1,

2,

3].

Visuomotor integration, defined as the ability to coordinate visual perception with motor responses, is essential for the development of functional skills. Research has shown that deficits in this area not only impair handwriting, sports performance, and play but also affect complex cognitive processes such as attention and working memory [

4,

5]. Additionally, there is a documented relationship between low visual acuity and impaired visuomotor abilities, including eye-hand coordination, dynamic stimulus perception, and bilateral responses [

6,

7].

In countries like Chile, more than 36.86% of university students are overweight, and at least 42.2% report low levels of physical activity [

8,

9]. In Colombia, sedentary behavior among students reaches 42.77% [

10]. These factors, along with excessive screen time, often surpassing three hours daily among adolescents [

11,

12], increase the risk of neurosensory deficits. Multiple ystematic reviews have linked prolonged screen exposure to adverse cognitive, motor, and neurological outcomes in children and adolescents [

1,

2,

13].

While technologies such as Dynavision D2 and FITLIGHT Trainer have demonstrated effectiveness in training visuomotor responses within sports and clinical contexts [

14,

15], their high cost, technical demands, and limited portability hinder their application in school and community settings. In response, recent studies have explored more accessible alternatives, including augmented reality, based stimuli [

16], gamified perceptual visual training [

17], microcontroller-based biomechanical systems [

18], and mobile sensors for motor response quantification [

19].

Furthermore, the literature underscores the potential for visuomotor neuroplasticity during adolescence and young adulthood, opening a window for targeted interventions to strengthen neural circuits involved in sensorimotor integration [

20]. Notably, short-duration dynamic visual stimulation programs have shown measurable improvements in reaction time and selective visual processing [

21]. Advances in non-invasive neuromodulation such as transcutaneous spinal stimulation have also shown promising effects on postural and locomotor control [

22,

23,

24].

From a public health standpoint, there remains a significant gap in accessible visuomotor evaluation and training tools that can be integrated into educational settings. According to the Pan American Health Organization, visual disorders among children and adolescents remain underdiagnosed in Latin America, with limited access to timely detection and intervention programs [

25]. Although some school-based prevention initiatives exist, their scope and coverage are often insufficient [

26].

In this context, the development of affordable, portable, robust, and adaptable technologies becomes essential. This study presents the design and preliminary validation of ENVISO, a bilateral visuomotor training system based on an ESP32 microcontroller. Programmed to generate dynamic visual stimuli and record real-time motor responses, ENVISO aims to provide a functional, durable, and low-cost tool with features that facilitate its implementation in both educational and community settings. Its development responds to the need for accessible and long-lasting solutions for the early detection and enhancement of visuomotor skills in adolescents across Latin America.

2. Materials and Methods

This section is organized to detail the key aspects of the electronic trainer for improving visual-motor coordination (ENVISO) to provide a comprehensive understanding. It includes components, a block diagram, software architecture, and operational mechanisms.

2.1. Components

The ergonomic buttons and LED matrices optimized for visibility significantly enhance the user experience by providing both tactile comfort and visual clarity. This design not only improves the usability of the oculo-manual trainer but also ensures that users can concentrate fully on their training sessions, maximizing the effectiveness of the device's various training modes [

27].

The trainer incorporates 16 light-feedback buttons, eight of which are allocated to each user. On the upper front panel, LED matrices display the scores of both users, and an additional matrix shows the timer. Meanwhile, the lower front panel houses a liquid-crystal display (LCD) screen, enabling users to configure and customize training modes easily.

Figure 1.

Distribution of components and dimensions.

Figure 1.

Distribution of components and dimensions.

To ensure durability and resilience, the trainer's casing was constructed using high-quality materials, including 9 mm thick wood coated with a matte gray laminate. The internal components were strategically positioned to minimize the risk of damage, and transportability was enhanced by incorporating sturdy handles. Moreover, the score and timer display panel were designed to fold inward, providing additional protection against impacts. A layer of smoke acrylic was applied to safeguard the components while maintaining clear visibility for users.

2.2. System Start-Up

The previous components facilitate initial functionality tests, visuomotor agility assessments, user interface evaluations, and integrated system testing, as detailed in the following sections:

2.2.1. Initial Tests

Initial tests were conducted on the electronic components to validate the power stage and signal conditioning functionality. The system chassis includes a 3P male AC power plug with an integrated toggle switch and a fuse holder for enhanced safety. The power system is a 12V switched power supply [

28], which features advanced safety protocols, including protections against short circuits, overload, overvoltage, and overheating. The power supply supports an input voltage range of 110-220V, delivers an output current of 30A, and has a power rating of 360W, with an integrated cooling fan to ensure temperature regulation. Regarding power consumption, each LED matrix requires a maximum of 2A, resulting in a total current demand of 6A for all matrices.

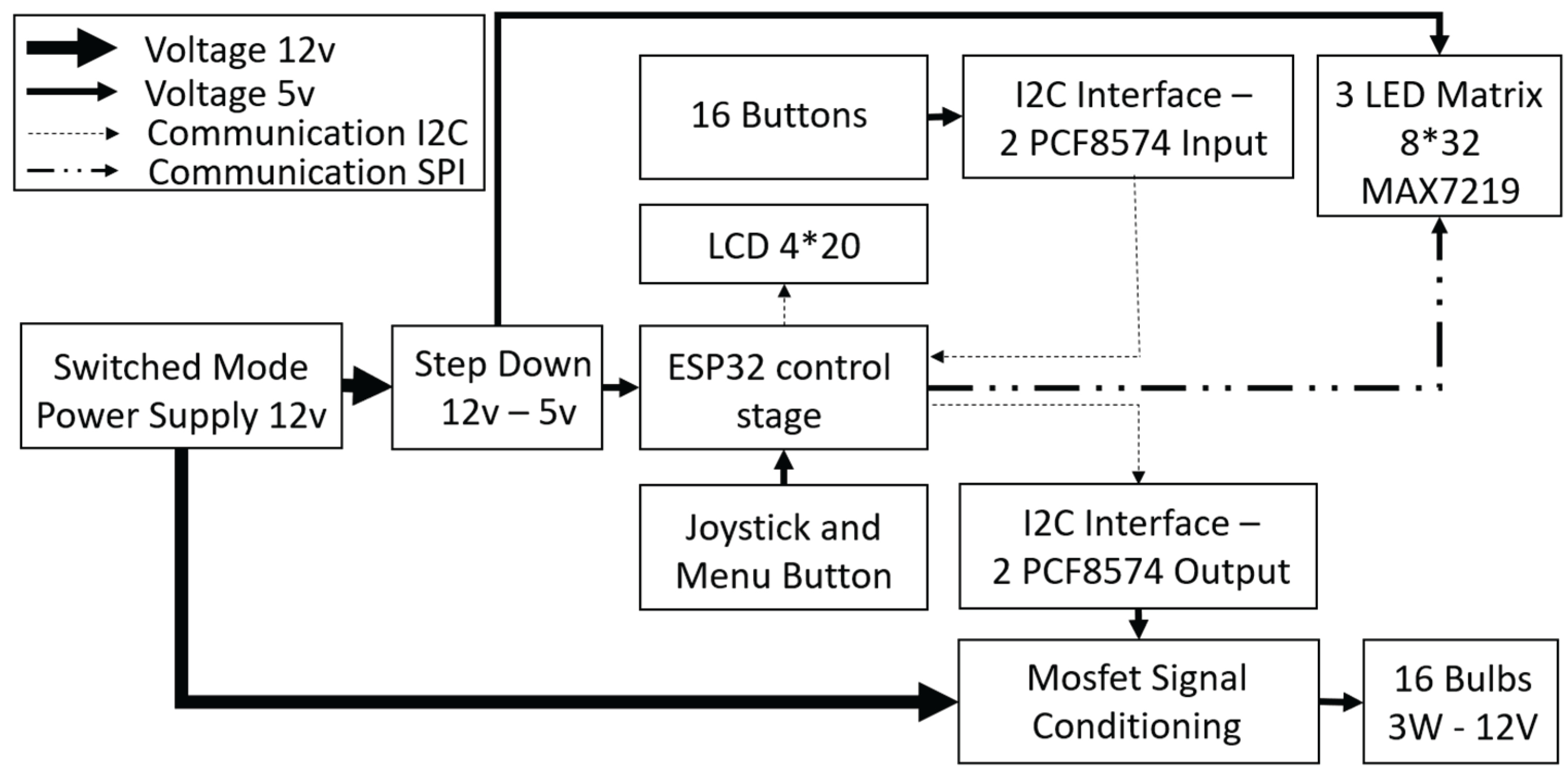

2.2.2. Power Supply and Interconnectivity of Components

The ENVISO system is powered by a switched power supply, which provides energy to power stages. These stages utilize metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistors (MOSFETs) [

29] to activate the lights embedded in the buttons. A voltage converter (STEP DOWN) [

30] reduces the voltage from 12V to 5V, supplying power to both the ESP32 microcontroller board and the LED arrays. The integrated 3.3V regulator within the ESP32 module also provides the necessary power for other input signals, including buttons, a joystick, and additional project components. This design ensures stable operation across all embedded system components.

The ESP32 microcontroller facilitates communication through the Inter-Integrated Circuit (I2C) protocol, interfacing with four 8-bit expanders [

30]. These expanders manage the signal control required to operate the 16 buttons and 3W lights. Additionally, the ESP32 handles communication with three 8x32 common cathode LED matrices dedicated to displaying the user scores and the timer during training sessions.

Furthermore, the I2C protocol interfaces with a 4x20 character LCD display [

31], which presents the user-configured settings. Adjustments to these configurations are seamlessly achieved by an intuitive interface consisting of a joystick and a button. This integrated design enhances user interaction while maintaining efficient control of the system's components.

Figure 2.

ENVISO - Block Diagram.

Figure 2.

ENVISO - Block Diagram.

2.2.3. Display System Test

For visualization tests, various button types were evaluated, with the arcade-style button (featuring a 50 mm diameter and illuminated translucent red plastic) identified as the most user-friendly. To optimize the user experience, buttons were spaced 5 cm apart, ensuring comfortable access during training sessions.

The system incorporates flexible setup options, allowing users to adjust the lighting duration and the maximum score for each training mode. These settings accommodate users' varying physical abilities, enhancing adaptability and inclusivity.

For tactile responsiveness, a debounce time of 50 ms was established for button presses, based on specific user interface testing, to ensure reliable input recognition. Visual perception tests included sequences of random lights, with 3W bulbs exhibiting a diffuse intensity compared to LED lights, improving visibility and user interaction during training.

To enhance usability, the LCDs an initial message for two seconds before going to the navigation controls. This delay ensures that users have sufficient time to familiarize themselves with the system's start-up sequence. Red LED matrices were selected due to their brightness and clarity for time and score information. Communication with these matrices is managed through the Serial Peripheral Interface (SPI) protocol [

32].

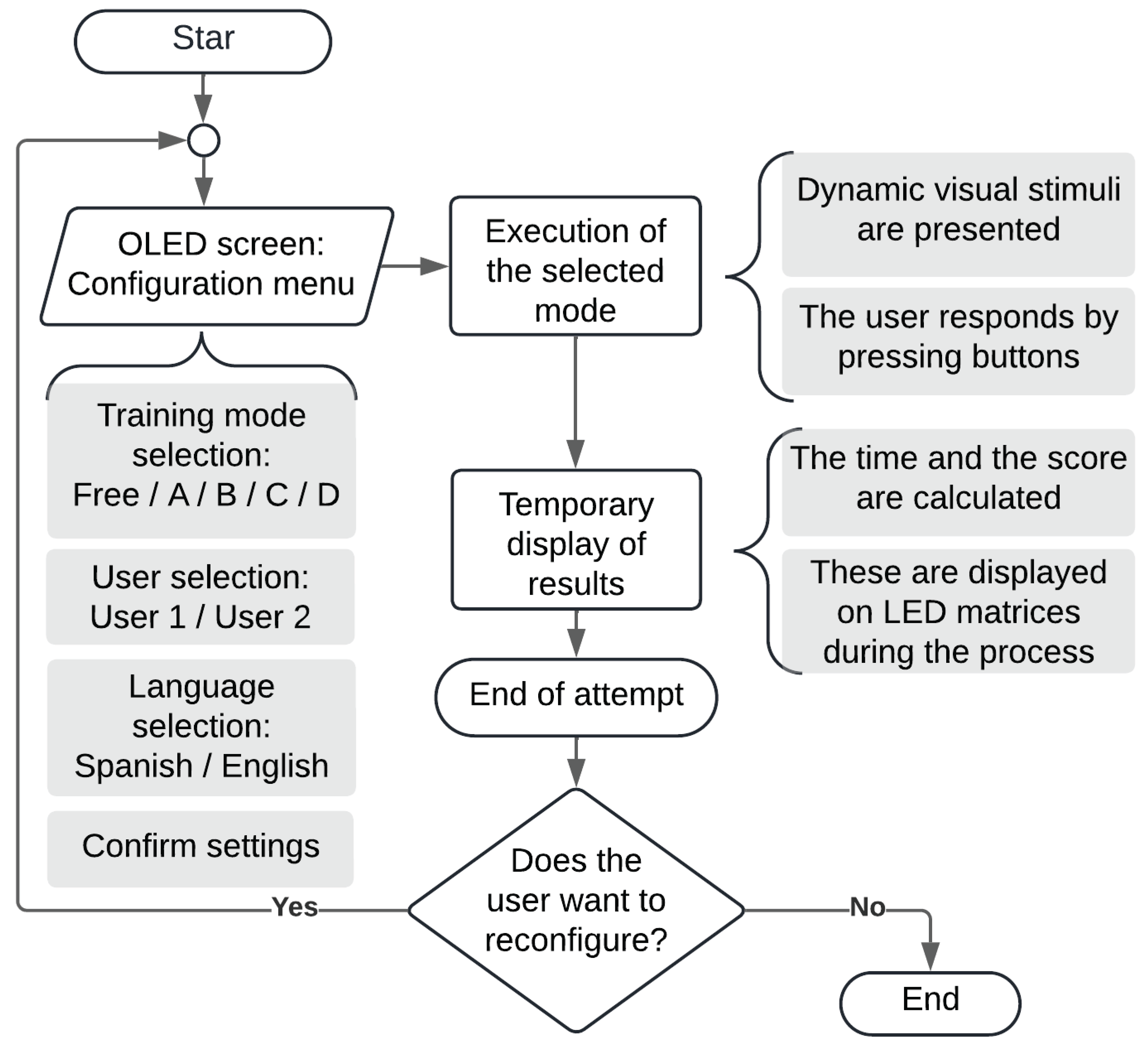

2.3. Software Implementation

In the flowchart, the functions handling the LCD screen, buttons, and LED matrices can be observed.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of ENVISO.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of ENVISO.

The implemented software is structured to manage devices efficiently through serial communication protocols, SPI, and I/O expander chip modules (PCF8574). Key features of the design include:

Initialization and Libraries: Essential libraries are imported at the beginning of the program to establish reliable communication and control over peripherals. These libraries facilitate the integration and interaction with the hardware components.

Global Variable Definitions: The software includes global variables for configuring the LED matrices and the LCD screen. These variables define the system's visual output parameters and enable dynamic updates during operation.

Interruption Management: Interrupt-driven programming ensures responsive system behavior, especially for handling user inputs and real-time updates.

2.3.1. Core Functionalities:

The main functions of the ENVISO system control user interaction, visual stimulus presentation, and system response. The following subsections describe three key functions: LCD(), Pushbuttons(), and Matrices(), responsible for managing the interface, buttons, and LED matrices, respectively.LCD() Function: This function manages the joystick and ENTER button inputs, using a switch-case structure to modify and display menu options on the LCD screen dynamically. That serves as a central element for user interaction and configuration.

These interconnected modules establish system control, monitoring, and interactive user experience. The design's modularity and adaptability facilitate future enhancements, ensuring the system remains scalable and efficient.

2.4. Operation

This section outlines the training modes available in the system, which are selectable through the menu interface:

The randomness in the system is based on the use of the platform's pseudo-random number generator. The method used, randomSeed() [

3], initializes this generator with values taken from an analog pin, which introduces variability from electrical noise or natural fluctuations in the pin (This is a feature of the ESP32). During execution, LEDs are selected using random(), which generates numbers within a specified range, allowing one to determine which LEDs will be lit in each iteration of the training.

2.4.1. Training Modes

The ENVISO system offers five training modes, each targeting different aspects of visuomotor coordination. These modes vary in stimuli, timing, and motor demands. Below, each mode is described with its specific purpose and mechanics.

Free Mode (Points): In this mode, the user sets a target number of points to achieve ASAP. Points are earned by pressing the buttons corresponding to lights that illuminate randomly and individually. The default target is set to 20 points, though this can be adjusted. User scores (points1, points2) and performance metrics (e.g., successRate) are calculated using basic counters. Variables such as correct rounds and incorrect rounds are used to record statistics per session. This mode incorporates a personal challenge element, encouraging users to set and exceed individual goals in successive sessions, thereby fostering continuous improvement and engagement [

35].

Mode A (Agile Response): In this mode, a light is randomly and individually illuminated for a predetermined duration. The user must press the corresponding button as quickly as possible. The faster the user reacts, the more lights are sequentially activated, allowing for the accumulation of maximum points. A timer (hw_timer_t) is used to generate periodic interrupts [

36], controlling events such as light changes or point counting.

The start time is recorded, and values are compared against the time limits defined for each mode (e.g., the 750 ms limit in Speed mode). This progressive design seeks to optimize both the speed and accuracy of motor responses, serving as a valuable tool for improving visuo-motor coordination and reducing reaction times [

37,

38].

Mode B (Two hands): In this mode, two lights are illuminated randomly for a user-configured maximum time. Both corresponding buttons must be pressed simultaneously within the allotted time to earn points. This mode is specifically designed to train and enhance bilateral coordination, making it particularly valuable for activities or tasks that demand synchronized use of both hands or limbs [

39,

40].

Mode C (Timed Reaction): In this mode, 16 lights are illuminated individually and randomly, with each light remaining active for a maximum of 750 ms. If the user fails to press the corresponding button within this time, the system automatically activates a different light. The objective is to score the highest number of points within a user-defined time limit, with the default duration set to 60 seconds. This mode is particularly effective for training rapid responses under time pressure, simulating scenarios where quick decision-making and reaction speed are critical [

41,

42,

43].

Mode D (Button detection disabled): In this mode, 15 lights remain constantly illuminated, with one light randomly turning off for a specified duration. The user must quickly identify and press the button corresponding to the deactivated light to score points. The objective is to achieve the highest score within a set time limit, with the default duration configured to 60 seconds. This mode reverses the conventional dynamic of light activation, emphasizing the recognition of negative stimuli (the absence of light) and fostering heightened attention and perceptual agility [

44,

45].

Each training mode offers options for two users, dividing the 16 buttons into eight for User One and eight for User Two. This allows simultaneous participation, fostering competition and collaboration. The inclusion of two user modes expands the device's applicability to 10 distinct training options. At the end of each session, the LCD screen displays performance statistics for both users, detailing the number of hits and errors. This feedback mechanism is crucial for tracking progress and identifying areas for improvement.

The design and development of ENVISO are focused on optimizing user interaction and system reliability. The ergonomic buttons and LED matrices were chosen by their capacity to enhance interaction, minimize fatigue, and improve precision in visuo-motor training systems [

46,

47]. Similarly, durable materials were selected for the device's casing to ensure longevity and safeguard internal components, particularly in demanding environments [

48]. Furthermore, the implementation of specialized software employing standard communication protocols such as I2C and SPI facilitates seamless and accurate device communication, which is essential for the efficient operation of embedded systems [

49].

2.5. Participants

The inclusion criteria established for this study were: age between 18 and 30 years, no neurological, orthopedic, or sensory diagnoses that would affect the motor control of the upper limbs, normal or corrected vision, and being in appropriate physical condition to perform bilateral wrist and finger movements. Additionally, all participants signed an informed consent approved by the institutional ethics committee.

Individuals who reported musculoskeletal limitations, uncontrolled cardiovascular conditions, or a history of neuromotor disorders were excluded.

Based on these criteria, a total sample of 26 participants was formed. The subjects were classified into four categories according to their body mass index (BMI): underweight, normal, overweight, and obesity.

Table 1.

presents a summary of their demographic characteristics.

Table 1.

presents a summary of their demographic characteristics.

| BMI Group |

N participants |

Mean age (years) |

% Women |

% Men |

Average BMI (kg/m²) |

| Underweight |

3 |

21,33 |

33,33 |

66,67 |

17,75 |

| Normal weight |

14 |

19,21 |

28,57 |

71,43 |

21,24 |

| overweight |

6 |

25 |

16,67 |

83,33 |

28,1 |

| obesity |

3 |

22 |

0 |

100 |

32,47 |

| Total |

26 |

21,12 |

23,08 |

76,92 |

23,72 |

3. Results

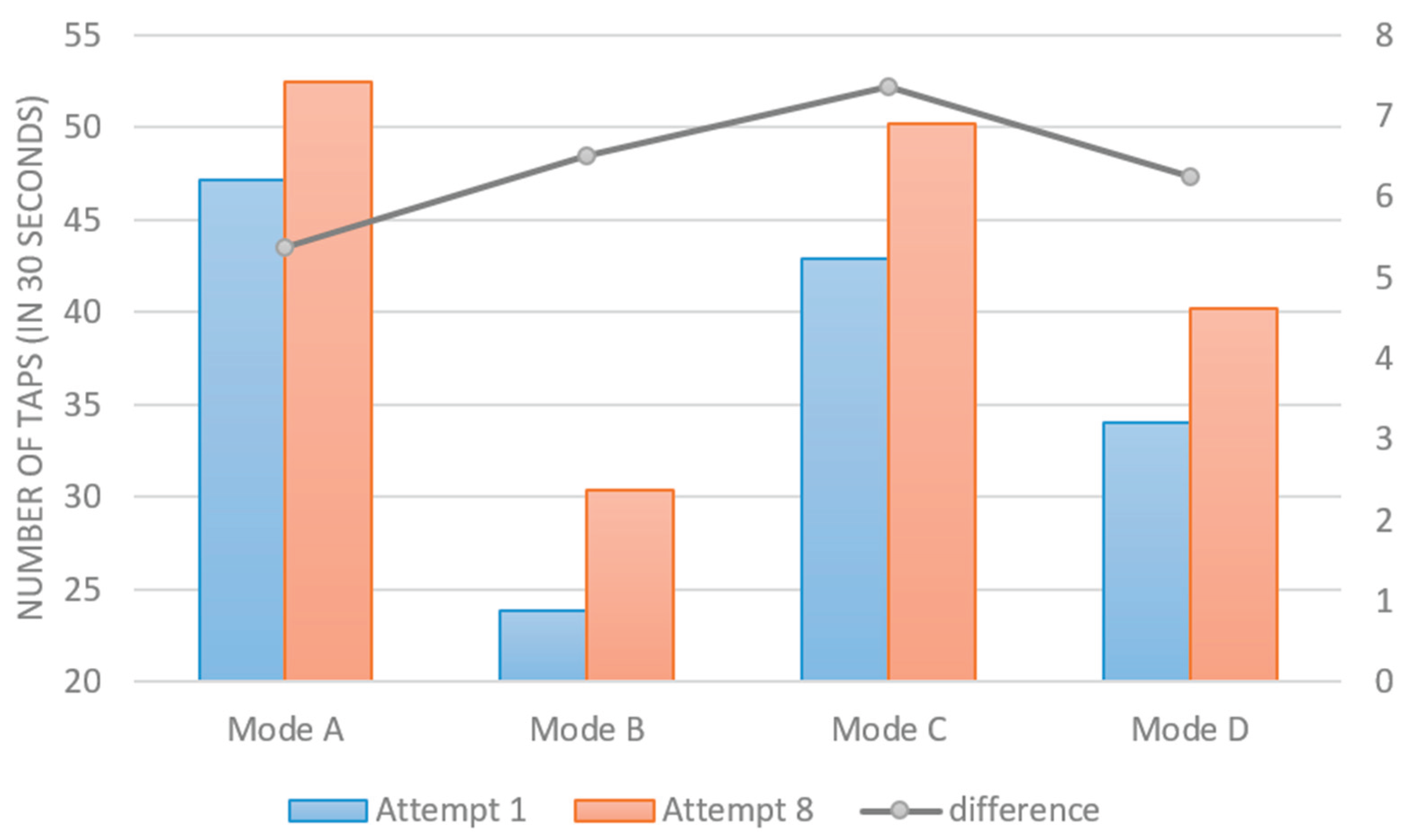

3.1. Comparison Between Interaction Modes (30 s)

As part of an exploratory phase prior to the detailed analysis of Mode C, a visomotor training intervention was conducted over four weeks, with a frequency of two sessions per week. This phase involved eight young adults, equally composed of four women and four men, aged between 18 and 30 years. Each session included practice in the four interaction modes available in the ENVISO system (Modes A, B, C, and D), with a duration of 30 seconds per trial for each mode.

The objective of this phase was to identify which training mode offered the greatest benefits in terms of increased successful responses (taps) over repeated attempts. To achieve this, eight attempts per mode were performed throughout the intervention period. The results showed that Mode C produced the greatest average increase in successful responses between the first and eighth attempts (average improvement = 7.38 taps), significantly outperforming the other modes. This superior performance is attributed to the combination of random visual stimuli, time pressure (750 ms per stimulus), and the requirement for bilateral responses, which generates a high cognitive and motor load. These results justify the choice of Mode C as the primary condition for the subsequent phase of the study.

Figure 4.

Average Increases Between Attempt 1 and Attempt 8 for Modes A, B, C, and D.

Figure 4.

Average Increases Between Attempt 1 and Attempt 8 for Modes A, B, C, and D.

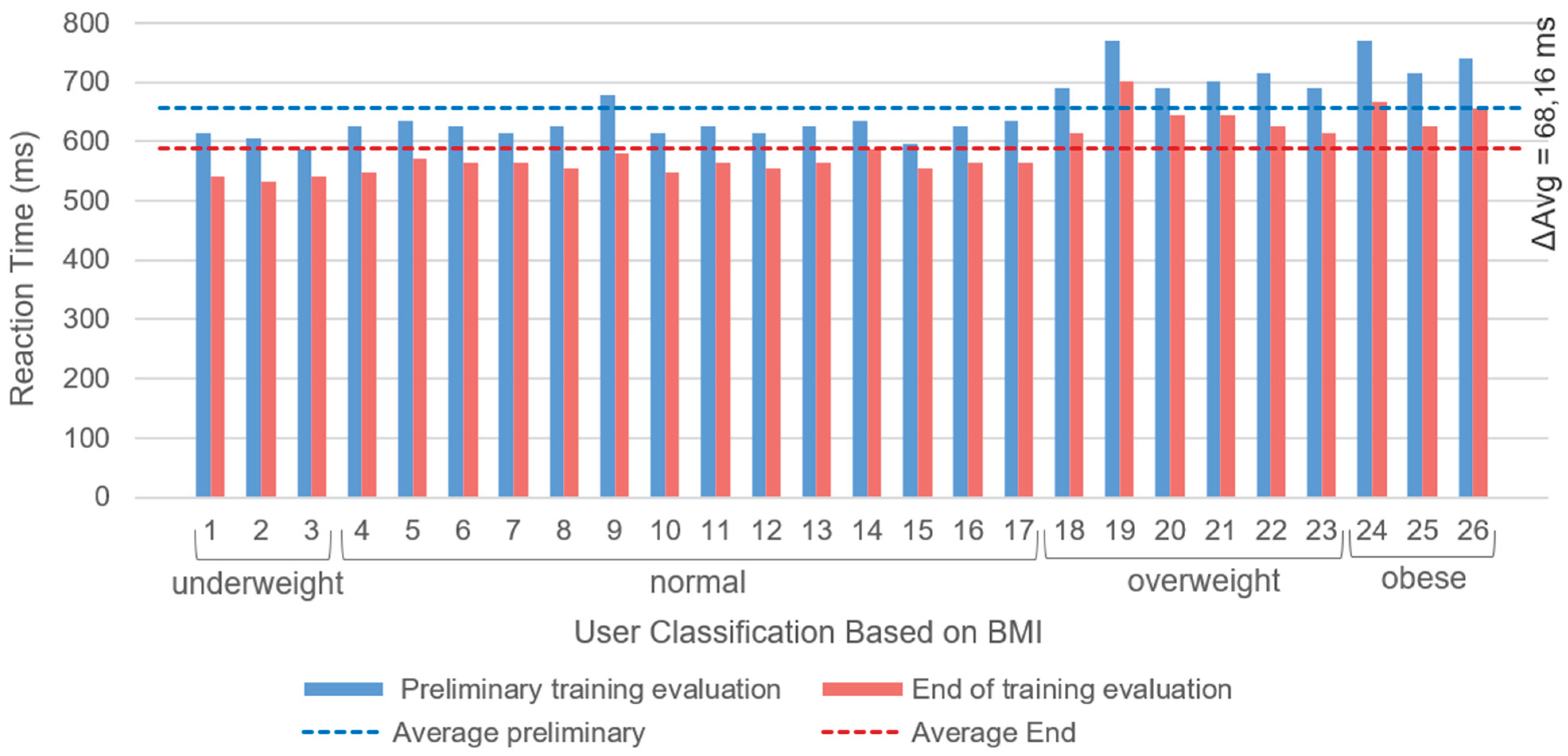

3.2. Detailed Analysis of Mode C (40 s)

After identifying Mode C as the most effective during the comparative phase, a specific intervention was designed focusing exclusively on this mode with an expanded sample of 26 young adults (aged 18 to 30 years). The intervention lasted four weeks, with a frequency of two sessions per week, replicating the initial conditions but focusing solely on Mode C.

During each trial, participants were required to respond to the random activation of 16 lights, each visible for a maximum of 750 milliseconds. If the corresponding button was not pressed within that time, the system automatically moved to the next stimulus. The duration of each trial was extended to 40 seconds, aiming to capture a larger volume of data per session and improve the sensitivity of the measurements.

Before the start of the program, a preliminary performance assessment was conducted for each participant, followed by a final evaluation at the end of the training. Additionally, each participant's body mass index (BMI) was recorded to explore potential relationships between nutritional status and the magnitude of the progress achieved. Participants were classified into four categories based on their BMI: underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obesity.

Figure 5 shows the average reaction times obtained in the preliminary and final assessments, grouped by nutritional status. In general, an average reduction of 68.16 ms in reaction time was observed after the training program, decreasing from an initial average of 656.31 ms (SD = 51.83) to a final average of 588.15 ms (SD = 44.86). This difference reflects a significant improvement in the visuomotor response speed of the participants.

Figure 5.

Reaction times from the preliminary and final training evaluations, classified by the participant's weight.

Figure 5.

Reaction times from the preliminary and final training evaluations, classified by the participant's weight.

When breaking down the results by BMI group, it was evident that all nutritional categories showed improvements in reaction times, although with differences in the magnitude of the change. The group classified as underweight showed an average improvement of 65.09 ms (n = 3), while the normal weight group showed an average reduction of 63.83 ms (n = 14). The overweight group showed an improvement of 67.73 ms (n = 6), and the obesity group achieved an average reduction of 92.28 ms (n = 3). These results indicate that visomotor training using Mode C of the ENVISO system is effective across all BMI profiles evaluated. However, the variability observed in the improvement magnitudes could be influenced by both individual physiological factors and the small size of some subgroups, particularly in the case of obesity. In this regard, the importance of considering nutritional status as an analysis variable in future research is highlighted, as well as the need for more balanced samples to validate and generalize the effects of the training.

Table 2.

Reaction times of participants by BMI group.

Table 2.

Reaction times of participants by BMI group.

| BMI Group |

N participants |

Average Preliminary Time (ms) |

Average Final Time (ms) |

Average Improvement (ms) |

| Underweight |

3 |

603,23 |

538,14 |

65,09 |

| Normal weight |

14 |

626,85 |

563,02 |

63,83 |

| overweight |

6 |

709,04 |

641,31 |

67,73 |

| obesity |

3 |

741,42 |

649,13 |

92,28 |

3.3. Influence of Nutritional Status on Performance

Previous studies have demonstrated that body mass index (BMI) can affect various aspects of motor performance and neuromotor response, including coordination, postural balance, aerobic capacity, and, in some cases, brain structures associated with movement control. [

39,

41,

44,

50,

51]. Considering these antecedents, in the present study, participants were classified into four nutritional status categories: underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obesity. For each subject, the difference between the score obtained in Attempt 8 and Attempt 1 of Mode C of the ENVISO system was calculated to estimate individual progress during training.

To determine if there were significant differences in performance improvement between the different BMI groups, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied. The results showed no statistically significant differences (F = 1.84; p = 0.169 > 0.05), suggesting that, although all groups showed improvements, the magnitude of the change did not vary significantly between nutritional categories.

Despite this lack of statistical significance, it is important to consider that the sample size was small in some subgroups, especially in the underweight and obesity categories (n = 3 in both cases), which may have limited the power of the analysis. However, these results align with recent research indicating that, while BMI may have an effect on motor performance and brain structure, these effects do not always translate into observable differences in the short term in practical interventions. [

44,

50].

3.4. Performance Variability Analysis

3.4.1. Preliminary Evaluation (Standard Deviation)

In the initial evaluation, an average reaction time of 656.31 ms (SD = 51.83 ms) was recorded, with a reference range from 604.48 ms to 708.14 ms. Of the 26 participants, 16 fell below the mean. A higher concentration of responses was observed between 615 ms and 635 ms. Five subjects exceeded the upper limit and two fell below the lower limit, suggesting variability in neuromotor performance.

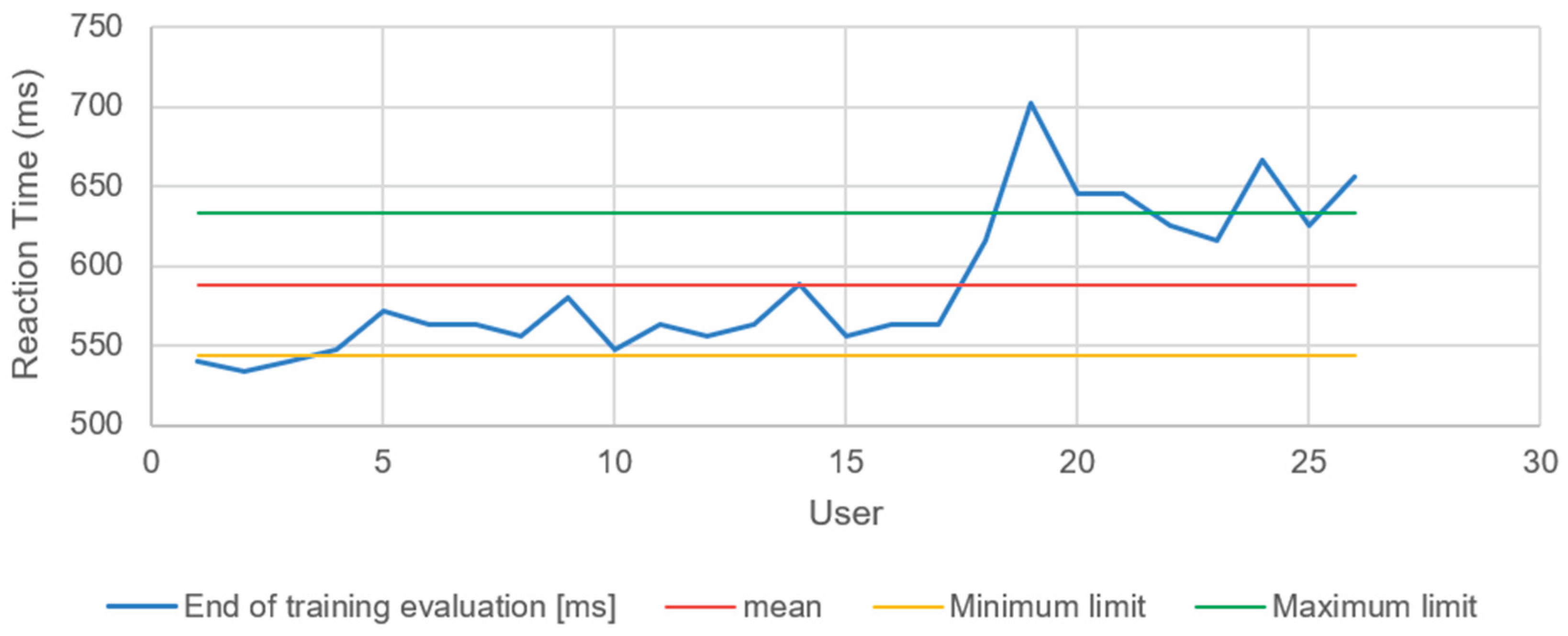

Figure 6 clearly illustrates the reduction in performance variability between the initial and final evaluations.

3.4.2. Final Evaluation (Standard Deviation)

After the training, the average reaction time decreased to 588.15 ms (SD = 44.86 ms), with a range between 543.29 ms and 633.01 ms. The percentage of participants below the average remained the same (61.5%), with a higher concentration between 540 ms and 580 ms, indicating greater consistency and homogeneity.

Figure 7 clearly illustrates the reduction in performance variability between the initial and final evaluations.

The data presented confirm measurable improvements in visuomotor performance following the ENVISO training protocol, with Mode C showing the highest effectiveness. Consistent reductions in reaction time and intra-subject variability were observed across all BMI categories, indicating a stable response to the intervention regardless of anthropometric differences. These outcomes serve as a basis for further interpretation in the discussion section.

4. Discussion

The results obtained indicate that visomotor training with the ENVISO system, applied over four weeks, led to a significant improvement in reaction time and motor response score, regardless of the participants' nutritional status. Although the ANOVA analysis did not reveal statistically significant differences between the BMI groups (F = 1.84; p = 0.169) [

52], all participants experienced improvements in their times and scores, supporting the effectiveness of the applied protocol.

These findings are consistent with recent studies showing that motor plasticity can be effectively developed even in individuals with overweight or obesity, as long as the training is structured and adapted [

53]. Furthermore, short-duration interventions have been shown to produce significant improvements in motor control and response speed, particularly in young adults [

54,

55].

An interesting finding was that, despite baseline differences between groups (e.g., higher BMI in the overweight and obesity categories), the overall improvement suggests that the ENVISO system could serve as an inclusive and effective tool for rehabilitation or motor education programs. Recent research has documented how adaptive visual systems can elicit functional changes even in overweight contexts through multisensory stimulation and visual feedback [

56,

57].

However, the limitations of the present study must be considered. The small number of participants in some subgroups (n = 3 for obesity and underweight) reduces statistical power and limits the generalization of the results. Additionally, there was no control group, which prevents attributing the effects solely to the intervention. Furthermore, lateralization and prior physical activity levels were not controlled, factors that could have influenced the results.

5. Conclusions

This study provides preliminary evidence that ENVISO, a bilateral visuomotor training system, significantly improves reaction time and motor performance in young adults after a short-term intervention. Mode C—based on time-constrained, randomly presented visual stimuli—was identified as the most effective training configuration, enabling the implementation of a cognitively demanding protocol that yielded measurable improvements. After four weeks of training (two sessions per week), participants showed an average reduction of 68.16 ms in reaction time, decreasing from 656.31 ms (SD = 51.83) to 588.15 ms (SD = 44.86). This was accompanied by a decrease in intra-subject variability, suggesting enhanced neuromotor consistency.

Although no statistically significant differences were observed across BMI groups, all categories—underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obesity—showed improvements, with average reductions ranging from 63.83 ms to 92.28 ms. These findings suggest the protocol is effective across diverse anthropometric profiles, positioning ENVISO as a potentially inclusive tool for visuomotor enhancement, regardless of nutritional status or baseline motor ability. The system’s modular architecture, robustness, and adaptability support its integration into educational and rehabilitative environments, particularly those with infrastructure limitations. These features make ENVISO a promising candidate for scalable deployment in public health and academic programs targeting cognitive-motor development in youth.

Future research should involve larger and more diverse samples, include control groups, and incorporate longitudinal designs to assess sustained effects. The addition of biometric or neurophysiological measures could further elucidate the mechanisms underlying the observed improvements.

6. Future Recommendations

Based on the findings of this preliminary study, future research should consider the following directions:

Clinical validation: Apply ENVISO to populations with clinically diagnosed visuomotor impairments (e.g., developmental coordination disorders, neurological injuries, eye–hand coordination deficits) to assess therapeutic effectiveness.

Larger and more diverse samples: Expand sample size, especially in vulnerable or underrepresented groups, to improve statistical power and generalizability.

Control and comparison groups: Incorporate randomized control groups or placebo conditions to isolate the specific effects of ENVISO training.

Long-term evaluation: Conduct longitudinal studies to assess retention of gains and possible transfer to real-world motor or cognitive tasks.

Neurophysiological insights: Integrate biometric or neural indicators (e.g., EMG, EEG, motion capture) to investigate underlying mechanisms of improvement.

Technological enhancements: Explore features such as wireless data logging, adaptive difficulty levels, and haptic or VR integration to increase usability and ecological validity.

Usability and implementation: Evaluate user experience, adherence, and feasibility in educational, clinical, and community-based environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Oscar Becerra, Javier Suárez and Manny Villa; methodology, Javier Suárez and Jhon Linares; software and Arnulfo Lizcano; validation, Arnulfo Lizcano, Oscar Becerra, Manny Villa, Jhon Linares, Javier Suárez; formal analysis, Manny Villa; investigation, Oscar Becerra, Manny Villa, Javier Suárez and Arnulfo Lizcano; resources, Javier Suárez; data curation, Manny Villa; writing—original draft preparation, Jhon Linares and Javier Suárez; writing—review and editing, Javier Suárez, Manny Villa, Oscar Becerra and Arnulfo Lizcano; visualization, Javier Suárez and Jhon Linares; supervision, Javier Suárez; project administration, Javier Suárez; funding acquisition, Javier Suárez and Manny Villa. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Universidad de Investigación y Desarrollo (UDI, Bucaramanga-Colombia).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- LeBlanc, A.G.; Gunnell, K.E.; Prince, S.A.; Saunders, T.J.; Barnes, J.D.; Chaput, J.-P. The Ubiquity of the Screen: An Overview of the Risks and Benefits of Screen Time in Our Modern World. Transl. J. Am. Coll. Sports Med. 2017, 2, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, M.S.; Aubert, S.; Barnes, J.D.; Saunders, T.J.; Carson, V.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Chastin, S.F.M.; Altenburg, T.M.; Chinapaw, M.J.M.; Altenburg, T.M.; et al. Sedentary Behavior Research Network (SBRN) – Terminology Consensus Project Process and Outcome. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reference-En/Language/Functions/Random Numbers/randomSeed.Adoc at Master · Arduino/Reference-En. Available online: https://github.com/arduino/reference-en/blob/master/Language/Functions/Random%20Numbers/randomSeed.adoc (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Carames, C.N.; Irwin, L.N.; Kofler, M.J. Is There a Relation Between Visual-Motor Integration and Academic Achievement in School-Aged Children with and without ADHD? Child Neuropsychol. J. Norm. Abnorm. Dev. Child. Adolesc. 2022, 28, 224–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, L.M.; Arvaneh, M.; Carton, S.; O’Keeffe, F.; Delargy, M.; Dockree, P.M. Impaired Metacognition and Reduced Neural Signals of Decision Confidence in Adults with Traumatic Brain Injury. Neuropsychology 2022, 36, 776–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, L. Relationships between Motor Skills and Academic Achievement in School-Aged Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Children 2024, 11, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinero-Pinto, E.; Romero-Galisteo, R.P.; Sánchez-González, M.C.; Escobio-Prieto, I.; Luque-Moreno, C.; Palomo-Carrión, R. Motor Skills and Visual Deficits in Developmental Coordination Disorder: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 7447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardones H, M.A.; Olivares C, S.; Araneda F, J.; Gómez F, N. Etapas del cambio relacionadas con el consumo de frutas y verduras, actividad física y control del peso en estudiantes universitarios chilenos. Arch. Latinoam. Nutr. 2009, 59, 304–309. [Google Scholar]

- García-Puello, F.; Herazo-Beltrán, Y.; Vidarte-Claros, J.A.; García-Jiménez, R.; Crissien-Quiroz, E. Evaluación de los niveles de actividad física en universitarios mediante método directo. Rev. Salud Pública 2020, 20, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Bayona, J.A. Niveles de Sedentarismo En Estudiantes Universitarios de Pregrado En Colombia. Rev. Cuba. Salud Pública 2018, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Foundation, S.P.R. Study Links Excessive Screen Time to Psychological Distress in Adolescents. Available online: https://www.news-medical.net/news/20250221/Study-links-excessive-screen-time-to-psychological-distress-in-adolescents.aspx (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Werneck, A.O.; Hallgren, M.; Stubbs, B. Prospective Association of Sedentary Behavior With Psychological Distress Among Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2025, 76, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, V.; Hunter, S.; Kuzik, N.; Gray, C.E.; Poitras, V.J.; Chaput, J.-P.; Saunders, T.J.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Okely, A.D.; Connor Gorber, S.; et al. Systematic Review of Sedentary Behaviour and Health Indicators in School-Aged Children and Youth: An Update. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, S240–S265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Occupational/Physical RehabilitationEvaluation & Training Device – Dynavision International.

- Hassan, A.K.; Alhumaid, M.M.; Hamad, B.E. The Effect of Using Reactive Agility Exercises with the FITLIGHT Training System on the Speed of Visual Reaction Time and Dribbling Skill of Basketball Players. Sports Basel Switz. 2022, 10, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, K.-E.; Zhang ,Jia; Huang ,Yang-Sheng; Liu ,Tzu-Chien; and Sung, Y.-T. Applying Augmented Reality in Physical Education on Motor Skills Learning. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 28, 685–697. [CrossRef]

- Theofilou, G.; Ladakis, I.; Mavroidi, C.; Kilintzis, V.; Mirachtsis, T.; Chouvarda, I.; Kouidi, E. The Effects of a Visual Stimuli Training Program on Reaction Time, Cognitive Function, and Fitness in Young Soccer Players. Sensors 2022, 22, 6680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sistema Biomecánico para Entrenamiento de Reflejos Deportivos - Artículo - Studocu. Available online: https://www.studocu.com/es-mx/document/instituto-tecnologico-de-tijuana/higiene-y-seguridad-industrial/sistema-biomecanico-para-entrenamiento-de-reflejos-deportivos-articulo/126753361 (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- LeMoyne, R.; Mastroianni, T. Implementation of a Smartphone as a Wireless Gyroscope Application for the Quantification of Reflex Response. In Proceedings of the 2014 36th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society; August 2014; pp. 3654–3657.

- Suh, J.H.; Han, S.J.; Choi, S.A.; Yang, H.; Park, S. Tablet Computer-Based Cognitive Training for Visuomotor Integration in Children with Developmental Delay: A Pilot Study. BMC Pediatr. 2024, 24, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reigal, R.E.; Barrero, S.; Martín, I.; Morales-Sánchez, V.; Juárez-Ruiz de Mier, R.; Hernández-Mendo, A. Relationships Between Reaction Time, Selective Attention, Physical Activity, and Physical Fitness in Children. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omofuma, I.; Carrera, R.; King-Ori, J.; Agrawal, S.K. The Effect of Transcutaneous Spinal Cord Stimulation on the Balance and Neurophysiological Characteristics of Young Healthy Adults. Wearable Technol. 2024, 5, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera, R.M.; Omofuma, I.; Yasin, B.; Agrawal, S.K. The Effect of Transcutaneous Spinal Cord Stimulation on Standing Postural Control in Healthy Adults. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 8268–8275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Tharu, N.S.; Gustin, S.M.; Zheng, Y.-P.; Alam, M. Trans-Spinal Electrical Stimulation Therapy for Functional Rehabilitation after Spinal Cord Injury: Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashadhana, A.; Serova, N.; Lee, L.; Casas Luque, L.; Ramirez, L.; Carlos Silva, J.; M Burnett, A. Access to School-Based Eye Health Programs: A Qualitative Case Study, Bogotá, Colombia. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 2021, 45, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Report on Vision. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241516570 (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Ruiz-Perez, L.M.; Barriopedro-Negro, M.I.; Ramón-Otero, I.; Palomo-Nieto, M.; Rioja-Collado, N.; García-Coll, N.; Navia-Manzano, J.A. Evaluar La Coordinación Motriz Global En Educación Secundaria: El Test Motor SportComp. [Motor Co-Ordination Assessment in Secondary Education: The SportComp Test]. RICYDE Rev. Int. Cienc. Deporte 2017, 13, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, J.; Dürbaum, T. An Overview of Saturable Inductors: Applications to Power Supplies. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 10766–10775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreas; Aldawira, C.R.; Putra, H.W.; Hanafiah, N.; Surjarwo, S.; Wibisurya, A. Door Security System for Home Monitoring Based on ESP32. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 157, 673–682. [CrossRef]

- Byamukama, M.; Bakkabulindi, G.; Pehrson, B.; Nsabagwa, M.; Akol, R. Powering Environment Monitoring Wireless Sensor Networks: A Review of Design and Operational Challenges in Eastern Africa. EAI Endorsed Trans. Internet Things 2018, 4, e1–e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusni Maulana, M.; Pratama, R.; Niswatin, C. Alat Perbaikan Faktor Daya Induktif Portabel; 2019.

- Atmajaya, D.; Kurniati, N.; Salim, Y.; Astuti, W.; Purnawansyah, P. Sistem Kontrol Timbangan Sampah Non Organik Berbasis Load Cell Dan ESP32. Semin. Nas. Teknol. Inf. Dan Komun. SEMNASTIK 2018, 1, 434–443. [Google Scholar]

- GitHub - Mongoose-Os-Libs/Arduino-Md-Parola. Available online: https://github.com/mongoose-os-libs/arduino-md-parola (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Seaton, G. JemRF/Max7219 2025.

- Gråstén, A.; Kolunsarka, I.; Huhtiniemi, M.; Jaakkola, T. Developmental Associations of Actual Motor Competence and Perceived Physical Competence with Health-Related Fitness in Schoolchildren over a Four-Year Follow-Up. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2022, 63, 102279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Software/Arduino-ESP32-IDE/Hardware/Espressif/Esp32/Cores/Esp32/Esp32-Hal-Timer.h at Master · LilyGO/Software. Available online: https://github.com/LilyGO/software/blob/master/Arduino-ESP32-IDE/hardware/espressif/esp32/cores/esp32/esp32-hal-timer.h (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Nobre, G.C.; Nobre ,F. S. S.; and Valentini, N.C. Effectiveness of a Mastery Climate Cognitive-Motor Skills School-Based Intervention in Children Living in Poverty: Motor and Academic Performance, Self-Perceptions, and BMI. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagogy 2024, 29, 259–275. [CrossRef]

- Nobre, F.S.S.; Valentini ,Nadia Cristina; and Rusidill, M.E. Applying the Bioecological Theory to the Study of Fundamental Motor Skills*. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagogy 2020, 25, 29–48. [CrossRef]

- Santayana de Souza, M.; Nobre, G.C.; Valentini, N.C. Effect of a Motor Skill-Based Intervention in the Relationship of Individual and Contextual Factors in Children with and without Developmental Coordination Disorder from Low-Income Families. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2023, 67, 102406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.L.A.; Cattuzzo, M.T.; Stodden, D.F.; Ugrinowitsch, H. Motor Competence in Fundamental Motor Skills and Sport Skill Learning: Testing the Proficiency Barrier Hypothesis. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2021, 80, 102877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.; Ali, M.F. Determining the Dynamic Balance, Maximal Aerobic Capacity, and Anaerobic Power Output of University Soccer and Rugby Players: A Cross-Sectional Comparative Study. Int. J. Hum. Mov. Sports Sci. 2021, 9, 1486–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J. ; Phys.org Visual Resistance Training for Athletes Improves Reaction Times, Study Finds. Available online: https://medicalxpress.com/news/2024-12-visual-resistance-athletes-reaction.html (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Zwierko, M.; Jedziniak, W.; Popowczak, M.; Rokita, A. Effects of Six-Week Stroboscopic Training Program on Visuomotor Reaction Speed in Goal-Directed Movements in Young Volleyball Players: A Study Focusing on Agility Performance. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2024, 16, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Li, G.; Zhang, M.; Xu, J.; Qi, H.; Ji, W.; Wu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, F.; Hu, Y.; et al. Associations between Body Mass Index, Sleep-Disordered Breathing, Brain Structure, and Behavior in Healthy Children. Cereb. Cortex 2023, 33, 10087–10097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahissar, M.; Hochstein, S. Task Difficulty and the Specificity of Perceptual Learning. Nature 1997, 387, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hastürk, G.; Akyıldız Munusturlar, M. The Effects of Exergames on Physical and Psychological Health in Young Adults. Games Health J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yuan, T.; Peng, J.; Deng, L.; Chen, C. Impact of Sports Vision Training on Visuomotor Skills and Shooting Performance in Elite Skeet Shooters. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1476649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggioni, S.; Stucki, S.; Lünenburger, L.; Riener, R.; Melendez-Calderon, A. A Bio-Inspired Robotic Test Bench for Repeatable and Safe Testing of Rehabilitation Robots. In Proceedings of the 2016 6th IEEE International Conference on Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics (BioRob); June 2016; pp. 894–899.

- Yamamoto, N.; Nishida, K.; Itoyama, K.; Nakadai, K. Detection of Ball Spin Direction Using Hitting Sound in Tennis.; SCITEPRESS, November 5 2020; Vol. 2, pp. 30–37.

- Hassan, A.K.; Bursais, A.K.; Ata, S.N.; Selim, H.S.; Alibrahim, M.S.; Hammad, B.E. The Effect of TRX, Combined with Vibration Training, on BMI, the Body Fat Percentage, Myostatin and Follistatin, the Strength Endurance and Layup Shot Skills of Female Basketball Players. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Chua, K.Y.; Ng, F.L.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Yuan, J.-M.; Khor, C.-C.; Heng, C.-K.; Dorajoo, R.; Koh, W.-P. Increased BMI and Late-Life Mobility Dysfunction; Overlap of Genetic Effects in Brain Regions. Int. J. Obes. 2023, 47, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estadistica aplicada: conceptos y ejercicios a través de excel de Pérez, César: New (2012) | AG Library. Available online: https://www.iberlibro.com/9788415452058/Estad%C3%ADstica-Aplicada-Conceptos-ejercicios-trav%C3%A9s-8415452055/plp (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- (PDF) Motor Skills and Cognitive Benefits in Children and Adolescents: Relationship, Mechanism and Perspectives. ResearchGate. [CrossRef]

- Visual-Motor Processing Speed and Reaction Time Differences between Medically-At-Risk Drivers and Healthy Controls | Request PDF. ResearchGate 2025.

- Kouhbanani, S.S.; Arabi, S.M.; Zarenezhad, S.; Khosrorad, R. The Effect of Perceptual-Motor Training on Executive Functions in Children with Non-Verbal Learning Disorder. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2020, 16, 1129–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeriani, F.; Protano, C.; Marotta, D.; Liguori, G.; Romano Spica, V.; Valerio, G.; Vitali, M.; Gallè, F. Exergames in Childhood Obesity Treatment: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 4938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, J.T.; Collins, P.F.; Luciana, M. Higher Adolescent Body Mass Index Is Associated with Lower Regional Gray and White Matter Volumes and Lower Levels of Positive Emotionality. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).