1. Introduction

The Momentum-First (M-First) framework has recently been shown to provide unified, quantitative resolutions to a range of anomalies in physics, from cosmological observations to celestial mechanics [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Its success has been based on a small set of rules governing particle kinematics and their modification by gravity. However, for any new framework to be considered fundamental, its rules must not be arbitrary postulates but should instead be derivable from a deeper, accepted theory.

The critical question is: what is the origin of the M-First principles? This paper provides the answer by demonstrating that the M-First framework is a direct consequence of M-Theory, in its conjectured non-perturbative formulation as the Banks-Fischler-Shenker-Susskind (BFSS) matrix model [

6,

7]. The BFSS model—a

-dimensional

gauge theory—is conjectured to capture eleven-dimensional supergravity in the light-cone frame. Throughout this paper we work in the strict large-

N limit where the duality to 11D supergravity is manifest and planar diagrams dominate.

This work presents two central derivations:

We derive the M-First kinematic framework—including its core conservation law and the unique form of its directional momentum operators—directly from the conservation of the 16 supercharges in the BFSS model (

Section 4).

We show that the M-First treatment of gravity, where the interaction enters quadratically (

), is mandated by non-perturbative supersymmetry constraints on the effective theory of interacting D0-branes (

Section 5).

By starting only with the established principles of the BFSS model, we derive the M-First rules, thereby elevating the framework from a phenomenological model to a consistent and testable consequence of M-Theory.

2. The Conceptual Bridge: Mapping BFSS to M-First

Before proceeding with the formal derivations, it is instructive to establish the conceptual mapping between the elements of the BFSS matrix model and the physical principles of the M-First framework. This correspondence serves as a "Rosetta Stone," translating the abstract degrees of freedom of matrix quantum mechanics into the tangible kinematic and dynamic quantities that M-First employs to describe particle physics. The core assertion of this paper is that this mapping is not an analogy, but a direct physical identification that emerges from the underlying theory.

In the large-N limit, a single particle is described by the full set of matrices. The M-First framework interprets the distinct mathematical roles of the bosonic and fermionic matrices as corresponding to distinct physical aspects of a particle’s momentum structure.

Table 1.

The correspondence between BFSS matrix model elements and their physical interpretation within the Momentum-First framework.

Table 1.

The correspondence between BFSS matrix model elements and their physical interpretation within the Momentum-First framework.

| BFSS Matrix Model Element |

M-First Physical Interpretation |

| The Matrices () |

The complete internal state of a single particle (in the large-N

limit). |

| Bosonic Matrices,

|

The External Momentum Structure. The dynamics of these matrices govern the

particle’s observable motion and external momentum, . |

| Fermionic Matrices,

|

The Internal Momentum Structure. These purely quantum degrees of freedom

are the source of the intrinsic Fermic Momentum, . |

| Commutator Potential,

|

Gauge Interactions. A direct potential term arising from the

interaction of D0-branes via open strings. |

| One-Loop Effective Action |

Gravitational Interaction. Gravity emerges from quantum effects; this is

the microscopic origin of the Kinetic Modifier, . |

| The BFSS Hamiltonian,

|

The total Core Momentum, (times c). It is the sum of

all internal, external, and emergent gravitational momentum contributions. |

| Supersymmetry Algebra,

|

The Fundamental Conservation Law. It algebraically binds the

internal () and external () momentum structures. |

This paper will substantiate this correspondence through two central proofs. In

Section 4, we will demonstrate that the supersymmetry algebra rigorously dictates the M-First kinematic conservation law. In

Section 5, we will show that the emergence of gravity from the one-loop effective action, combined with the constraints of supersymmetry, mandates the quadratic form of the M-First gravitational rule. This elevates the M-First framework from a set of phenomenological postulates to a derived effective theory of M-Theory.

3. The Foundational Principle: Supercharge Conservation in BFSS

The BFSS action is given by [

6,

8]:

The crucial feature is its

supersymmetry, implying 16 conserved supercharges,

. The supersymmetry algebra relates these to the kinematic operators

:

3.1. Conventions and Assumptions

We use a mostly-minus metric signature

. The Clifford algebra is defined by

. Traces of products of gamma matrices are evaluated in the representation where

with

for the eleven-dimensional Majorana spinor. We restrict our analysis to the sector of the theory with vanishing two-form and five-brane charges, where central charges in Eq. (

2) are zero for asymptotic states. The free core momentum operator is

, with eigenvalue

M. For a particle at rest, this eigenvalue is its intrinsic mass scale,

.

4. Derivation of Absolute Directional Momentum Conservation

We now derive the foundational kinematic rule of the M-First framework. The proof demonstrates that this law, and the specific form of the operators involved, is a necessary consequence of supercharge conservation.

The conservation of the total supercharge,

, in any scattering process implies the conservation of the total asymptotic kinematic operator:

To extract the directional content of this law, we project it using the operator

. The coefficient

is not arbitrary; as proven in

Appendix B, it is uniquely fixed by the requirements of the supersymmetry algebra and consistency with the rest frame.

Projecting Eq. (

3) with

and taking a normalized trace yields independent conservation laws along each half-axis:

Here,

M and

are eigenvalues of the operators

and

. This is the explicit mathematical statement of Absolute Directional Momentum Conservation, derived from first principles. The detailed calculation of the expectation values is provided in

Appendix A.

5. Derivation of the M-First Gravitational Rule

We now derive the M-First treatment of gravity. In the BFSS model, gravity emerges from quantum loops between D0-branes. The low-energy effective theory describing these interactions must preserve the full

supersymmetry of the parent theory [

9,

10]. This requirement rigidly constrains the algebraic form of the effective Hamiltonian operator,

.

The algebra of supersymmetric quantum mechanics implies a BPS positivity bound, where the operator must be positive semi-definite and expressible as a sum of squares of local operators from the theory. Any proposed Hamiltonian must respect this structure.

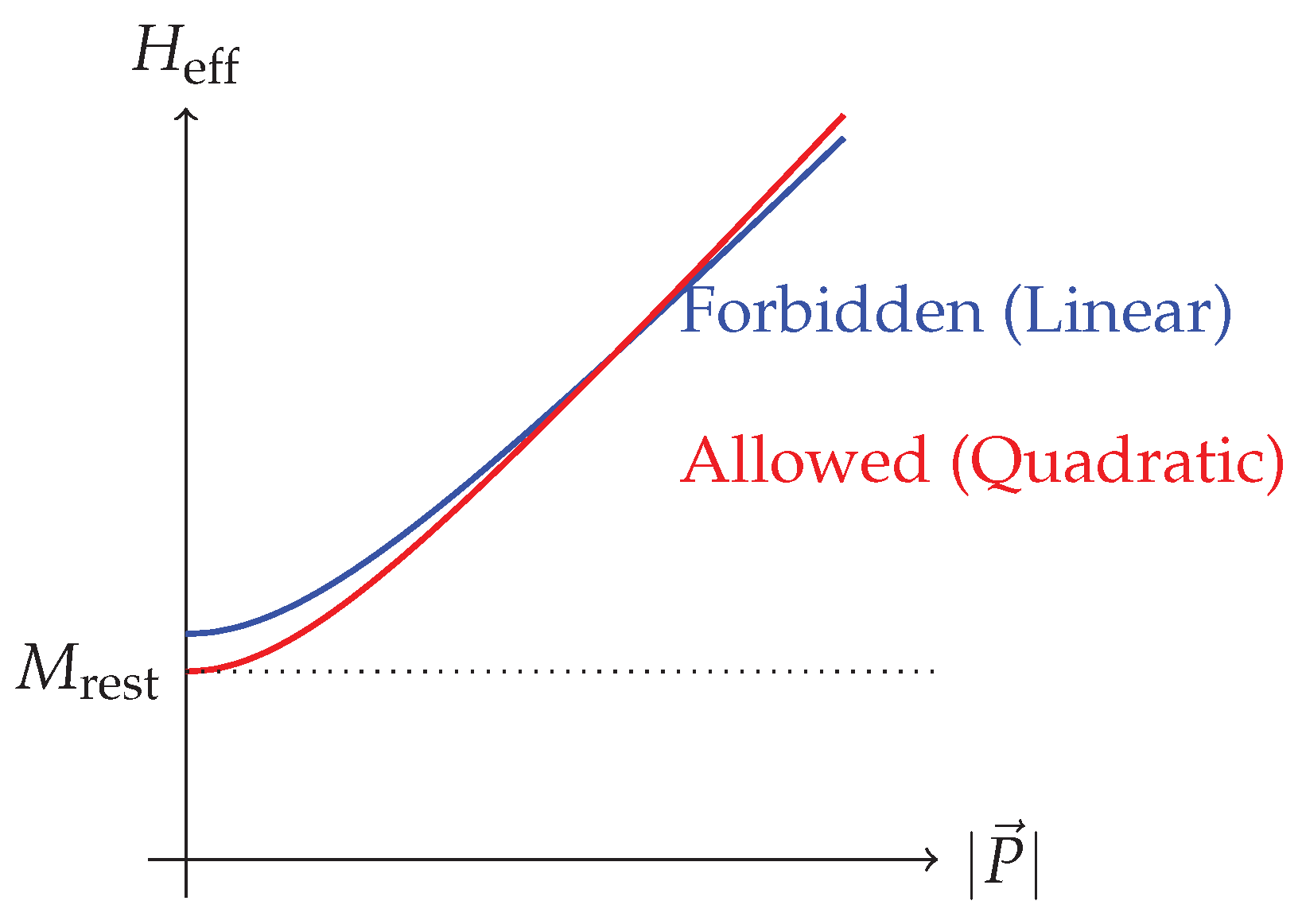

5.1. Hypothesis 1: The Linear Potential (Additive Model)

Consider the model where the interaction potential,

V, is added linearly to the free core momentum operator,

. The operator relevant to the supersymmetry constraint becomes:

As rigorously shown by Paban, Sethi, and Stern in the two-body sector [

9], the final "cross-term" is forbidden. Its non-analytic dependence on the momentum operator

cannot be recast as a sum of squares of local operators. In the planar large-

N limit, the same algebraic obstruction rules out such cross-terms for any finite number of interacting bodies.

Figure 1.

A schematic comparison of the two hypotheses for incorporating a gravitational potential. The linear model (blue, dashed-like) is forbidden by supersymmetry constraints, while the quadratic M-First model (red, solid) is algebraically consistent.

Figure 1.

A schematic comparison of the two hypotheses for incorporating a gravitational potential. The linear model (blue, dashed-like) is forbidden by supersymmetry constraints, while the quadratic M-First model (red, solid) is algebraically consistent.

5.2. Hypothesis 2: The Quadratic Potential (M-First Model)

Now consider the M-First model, where the gravitationally influenced core momentum operator,

, is defined by:

The operator relevant to the supersymmetry constraint is simply:

This expression is free of the forbidden cross-term. The term

, being the result of integrating out supersymmetric degrees of freedom, is itself composed of terms (like squares of fermion bilinears) guaranteed to be consistent with the "sum of squares" structure [

11,

12]. The quadratic incorporation of gravity is therefore mandated by non-perturbative supersymmetry.

6. Synthesis and Conclusion

The derivations in

Section 4 and

Section 5 establish that the M-First framework is a direct expression of M-Theory’s fundamental principles in the large-

N BFSS limit. From the single concept of supercharge conservation, we have derived the two pillars of M-First: its unique kinematic conservation law and its quadratic rule for gravitational interactions.

This quadratic rule also ensures consistency with known supergravity results. For example, the leading one-loop potential between two D0-branes in the BFSS model gives rise to the correct Newtonian potential in the appropriate classical limit [

10]. The quadratic incorporation of this potential via

into the energy relation is precisely what is required to reproduce the standard gravitational dynamics of DLCQ supergravity from the matrix model.

This work thus elevates M-First from a phenomenological model to a derived, falsifiable framework. Its ability to resolve physical anomalies can be understood as a direct reflection of the underlying dynamics of M-Theory itself.

Appendix A Calculation of the Directional Momentum Components

This appendix details the calculation for the M-First directional momentum components. The expectation value for a state with momentum eigenvalues

M and

is:

Expanding the trace and applying the identities from

Section 3.1:

Normalizing by gives the final result: .

Appendix B Uniqueness of the Directional Projection Operator

Here we demonstrate that the coefficient

in the projection operator

is uniquely fixed. Let

be an arbitrary real constant. The trace calculation from

Appendix A with this general operator yields:

The framework requires two consistency conditions:

-

Net Momentum Condition: The difference between the directional components must yield the net external momentum component

.

For this to equal , we must have , which implies .

Rest Frame Condition: For a particle at rest (), the directional components must equal the core momentum eigenvalue, M. With , we find , satisfying the condition.

Any other choice for would violate the fundamental requirement that the operator differences recover the net momentum vector components. Thus, the coefficient is uniquely determined.

References

- Klaveness, A. Momentum Is All You Need. Authorea Preprint, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Klaveness, A. The Momentum-First Dirac Equation: A Unified Hamiltonian for Fermions in Stationary Spacetimes. Authorea Preprint, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Klaveness, A. Enhanced Pycnonuclear Reactions in Neutron Star Crusts from Momentum-First Gravity. Brief Communication, manuscript in preparation.

- Klaveness, A. A First Principles Derivation of the Earth Fly-by Velocity Shift. Authorea Preprint, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Klaveness, A. A First-Principles Resolution of the Pioneer Anomaly from Kinematic Cosmological Drag. Brief Communication, manuscript in preparation.

- Banks, T.; Fischler, W.; Shenker, S.H.; Susskind, L. M theory as a matrix model: A conjecture. Phys. Rev. D 1997, 55, 5112–5128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkgraaf, R.; Verlinde, E.; Verlinde, H. Matrix String Theory. Nucl. Phys. B 1997, 500, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, W. M(atrix) theory: Matrix quantum mechanics as a fundamental theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2001, 73, 419–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paban, S.; Sethi, S.; Stern, M. Constraints from extended supersymmetry in quantum mechanics. Nucl. Phys. B 1998, 534, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat, D.; Taylor, W. Linearized supergravity from Matrix theory. Phys. Lett. B 1998, 426, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, P. Supersymmetry, Duality and Deconfinement in Matrix Quantum Mechanics. Phys. Rev. D 2001, 64, 106006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanada, M.; Nishimura, J.; Sekino, Y.; Yoneya, T. Direct test of gauge-gravity duality for matrix theory correlation functions. JHEP 2011, 12, 020–1108.5153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).