1. Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease [IBD] is a group of intestinal disorders that cause prolonged inflammation of the digestive tract. The main types of IBD are ulcerative colitis [UC] and Crohn's disease [CD], and their incidence is increasing worldwide [

1,

2]. IBD is thought to occur in people with a genetic predisposition following environmental exposures; gut epithelial barrier defects, the microbiota, and a dysregulated immune response are strongly implicated. Patients usually present with bloody diarrhea, and the diagnosis is based on a combination of clinical and laboratory findings, while endoscopy is the diagnostic gold standard. Medical treatment aims to induce a rapid clinical response and to maintain clinical remission. Management of IBD has changed considerably in parallel with newly available therapies, consisting of immunosuppressive agents as well as biologicals. In some patients, surgical treatment may still be required [

1,

2].

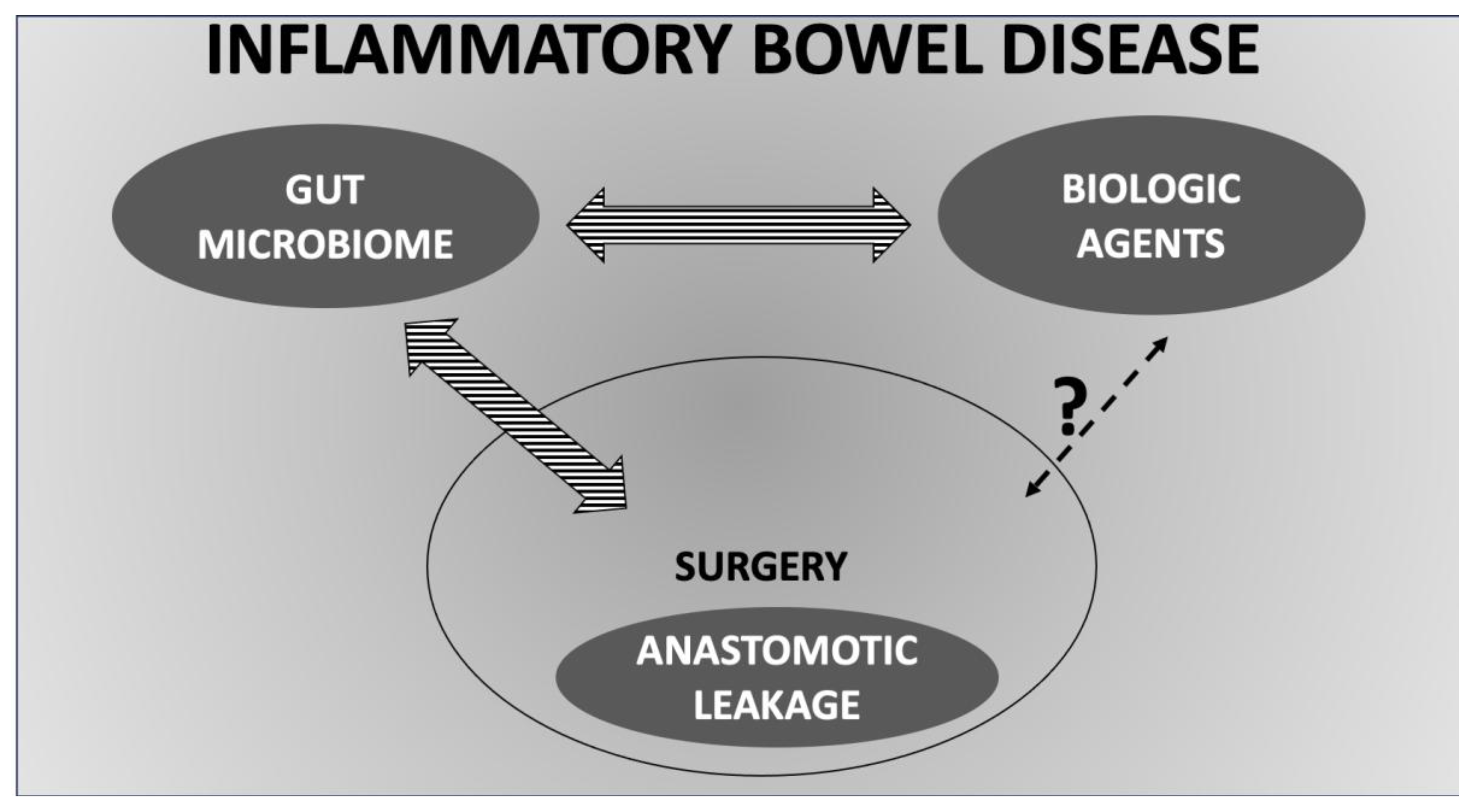

The gut microbiome is considered to play a key role in the pathogenesis of IBD as well as in the prediction and follow-up of treatment response. In this review, we aim to summarize current available evidence on the interplay of gut microbiome with biologic agents, surgery and surgical complications in patients with IBD.

2. Materials and Methods

Search was conducted across MEDLINE [PubMed] on 1 June 2025 under the terms: "Surgical Procedures, Colorectal"[Mesh], "Anastomosis, Surgical"[Mesh], “gut microbio*”, “faecalibacterium”, “dysbiosis”, “infliximab”, “adalimumab”, “ustekinumab”, “vedolizumab” about studies published in English without publication time restriction. The search was performed by two independent authors and the same authors assessed all articles generated from the electronic search, by title, abstract, and complete text to find those meeting the eligibility criteria. Publications retrieved from electronic databases were imported into reference management software [EndNoteX6, Thomson Reuters, New York, U.S.A.], and duplicates were removed. The search strategy is shown in

Figure 1.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Gut Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

3.1.1. Dysbiosis

The gut microbiota, as the endogenous gastrointestinal microbial flora is called, plays a fundamentally important role in health and disease; yet not completely defined and understood. There is significant intersubject variability and differences between stool and mucosa community composition partially attributed to variations in time, diet, and health status [

3]. In IBD, major changes in the composition of gut microbiota have already been described compared to healthy individuals. Frank et al investigated gastrointestinal tissue samples from CD and UC patients, as well as non-IBD controls [

4]. Microbiota of IBD patients has been characterized by depletion of commensal bacteria, in particular Bacteroidetes and the Lachnospiraceae subgroup of Firmicutes and concomitantly increase of Proteobacteria and the Bacillus subgroup of Firmicutes. Moreover, the small-intestine samples, as a whole, contain less overall phylogenetic diversity of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes than does the large intestine. These changes reflect a decrease in microbial diversity, both alpha and beta diversity whereas other studies support a concomitant decrease in health-promoting bacteria like Faecalibacterium and Roseburia [

5,

6]. Both bacteria of the Firmicutes phylum are producers of the short-chain fatty acid [SCFA], butyrate, and in the presence of butyrate, tissue macrophages differentiate and display enhanced antimicrobial activity [

7].

Disruption of the composition of microbiota resulting in pathogenicity is known as dysbiosis and it is hypothesized that this may be mediated by the interaction with environmental stressors in an individual with genetic potential to develop IBD [

8]. As the intestinal epithelial layer is vital for sustaining microbiota-to-host symbiosis and preventing the generation of unwanted immune and inflammatory responses, this relationship is impaired in IBD. The mucosal barrier becomes leaky due to the alteration of epithelial tight junctions, apoptosis, and ulceration of the intestinal lining so pathogenic microorganism invasion is allowed in a dysbiotic environment [

8].

3.1.2. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii

F. prausnitzii is one of the largest butyrate producers. Initially classified as Bacteroides prausnitzii in 1937, it was reclassified as

Fusobacterium prausnitzii in 1974 and then as

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in 2002 [

9]. It is imperative for sustaining health and luminal homeostasis and its abundance has been found to be altered across a wide range of diseases and disorders; in IBD it tends to diminish.

F. prausnitzii consists of two main phylogroups; phylogroup I found in 87% of healthy subjects but in under 50% of IBD patients. In contrast, phylogroup II is detected in>75% of IBD patients and in only 52% of healthy subjects. Consequently, even though the main members of the

F. prausnitzii population are present in both healthy and IBD, richness is reduced in the latter and an altered phylotype distribution exists [

10]. Such reductions in

Faecalibacterium abundance have been linked to the decreased circulation of CCR6 + CSCR6 + DP8α regulatory T [Treg] leukocytes and increased values of disease activity metrics [

11]. Moreover, butyrate production by

F. prausnitzii inhibits the enzyme HDAC1 in CD4+ T cells resulting in the downregulation of some proinflammatory cytokines, while also promoting Forkhead box P3 [Foxp3] which induces Th17/Treg balance via encouraging Th17 cells to differentiate [

12]. Considering all the above, it is understood that alterations in the composition and function of the gut microbiota may lead to alterations in gut microbiota-derived metabolites, such as bile acids, short- chain fatty acids and tryptophan metabolites, also implicated in the pathogenesis of IBD [

13].

In a cross-sectional study of 116 UC patients in remission, 29 first-degree relatives and 31 healthy controls,

F. prausnitzii was reduced in patients but also their relatives compared to controls. Low abundance of

F. prausnitzii was also associated with less than 12 months of remission.

F. prausnitzii increased steadily until reaching similar levels to those of controls if remission persisted, whereas it remained low if patients relapsed [

14]. Similarly, in a cohort of UC patients naïve to biological therapy before anti-tumor necrosis factor [TNF] therapy,

F. prausnitzii was in higher abundance in responders compared with non-responders at baseline and abundance of

F. prausnitzii increased during induction therapy in responders [

15]. Beneficial bacteria such as

F. prausnitzii and

Roseburia have been consistently linked to favorable clinical outcomes [

16].

3.2. Fluctuation of Gut Microbiota and Implications for Treatment Response Prediction

Recently, it has been acknowledged that gut microbiota in IBD fluctuates more than that of healthy individuals periodically visiting the pattern of healthy individuals and deviating away from it. Some fluctuations of the gut microbiota correlate with disease severity and some other have been associated with intensified medication due to a flare of the disease implying a future direction of microbiota composition guided therapies [

17,

18,

19]. In a recent systematic review of biomarkers of response to advanced therapies in IBD, a total of 1232 individuals had baseline microbial analysis as well as data on therapeutic response, accounting for 46% of the study population [

20]. Parameters evaluated as biomarkers for treatment response in the individual studies were: diversity, abundance of specific microbial taxa, presence of opportunistic organisms, SCFA-producing organisms and butyrate synthesis pathways, and other metabolomic analysis [

20]. Evidence from individual studies suggests that dysbiosis, characterized by a decrease in Firmicutes, and/or enterotyping correlate with the risk and time to relapse after anti-TNF treatment [

21,

22,

23]. Moreover, a range of metabolic biomarkers involving lipid, bile acid and amino acid pathways may contribute to prediction of response to anti-TNF therapy in IBD [

24]. In a proof-of-concept study, Busquets et al analyzed the predictive ability to identify anti-TNF treatment responders. The RAID algorithm consisting in the combination of 4 bacterial markers was developed showing a high capacity to discriminate between responders and non- responders with sensitivity and specificity values of 93.33% and 100% respectively, a positive predictive value of 100% and a negative predictive value of 75% [

25].

3.3. Longitudinal Changes of Gut Microbiota in IBD Patients Treated with Biologic Agents

As dysbiosis is considered to play a key role in IBD, several studies so far have investigated possible changes in the composition of gut microbiota during and/or after treatment with biologic agents compared to baseline; these studies are summarized in

Table 1 [

15,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. Evidence concerns mainly microbiota changes under treatment with TNF inhibitors but also other drugs discussed below in more detail.

3.3.1. Adalimumab

Adalimumab is a TNF-blocker used in the treatment of IBD. In a prospective study in Italy, microbiota of 20 patients with CD under adalimumab was investigated before start and after 6 months of treatment [

26]. In the whole population, there was a trend of an increased abundance of some main phyla such as Firmicutes and Bacteroides and a decreased abundance of Proteobacteria. These differences reached statistical significance only in patients with treatment success suggesting that response to adalimumab may be associated with reversal of dysbiosis. No significant changes have been observed in abundance of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. Similar results have been also reported by others in both CD [

25,

27] and UC [

28,

29].

3.3.2. Infliximab

Infliximab is another anti-TNF for the treatment of IBD. In a German study among patients with IBD, rheumatic diseases and healthy controls, Aden et al reported significant baseline differences among the three groups; dysbiosis was present in both IBD and rheumatic group [

30]. Interestingly, treatment with infliximab shifted the diversity of fecal microbiota in patients with IBD, but not with rheumatic disease, toward that of controls, suggesting that other factors may interfere with biologicals as well to induce clinical remission. Ditto et al focused on microbiota changes under treatment with TNF-inhibitors [TNFi] in a small cohort of patients with enteropathic spondylarthritis. Although no differences were observed in α- or β-diversity, abundance of Lachnospiraceae and Coprococcus increased and there was a decreasing trend in Proteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria [

31]. Similar studies confirm the restoration of gut dysbiosis in IBD patients under infliximab treatment reflected in the increase of α-diversity, increased abundance of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes, decreased abundance of Enterobacterales as well as increased abundance of SCFA-producing taxa such as Lachnospira, Roseburia and Blautia [family Lachnospiraceae] [

32]. These changes are more pronounced in treatment-responders and specific alterations like the ratio F. prausnitzii/ E. coli are accurate biomarkers to predict clinical remission performing even better than calprotectin and Harvey-Bradshaw index [

15,

33,

34].

3.3.3. Ustekinumab

Ustekinumab is a fully humanized IgG1κ monoclonal antibody that binds to the common p40 subunit of interleukin [IL]-12 and IL-23. This prevents these cytokines from binding to their receptors, thereby reducing the maturation and proliferation of Th-1 and Th-17 cells. In a small study of patients with IBD, no significant longitudinal effect of ustekinumab therapy was found neither on alfa and beta diversity nor on abundances of other phyla and/ or genera [

36]. In a secondary analysis of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b clinical trial among 306 anti-TNF-refractory CD patients, a high relative abundance of Faecalibacterium was associated with remission 6 weeks after induction. The median α-diversity of responders after ustekinumab induction significantly changed over time having increased from baseline to 4 weeks after ustekinumab induction, decreased from 4 to 6 weeks after induction, and was significantly higher than baseline at 22 weeks after induction, suggesting that microbiota changes may be a surrogate for treatment response [

37]. Xu et al, have reported even about changes of oral microbiota under ustekinumab treatment in responders and non-responders; oral samples are easier than faecal samples to obtain for follow-up of treatment response [

38]

3.3.4. Vedolizumab

Vedolizumab is a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody against α4β7 integrin, which selectively blocks the trafficking of the leukocytes into the gastrointestinal tract through its binding with the α4β7 integrin. In a small study of 29 participants, patients with remission under anti-integrin therapy had higher abundance of the phylum Verrucomicrobiota and metabolomic analysis showed higher levels of two SCFA, namely butyric acid and isobutyric acid, in these patients compared to non-responders [

39]. Ananthakrishnan et al, studied longitudinally the gut microbiota of 85 patients with IBD under vedolizumab and observed very few changes in microbial composition under treatment [

40].

However, there were significantly greater metagenomic alterations in microbial function. In CD, 17 pathways were significantly reduced on follow-up at week 14 compared to baseline, of which 15 were noted only in patients achieving remission. These included a decrease in several tricarboxylic acid cyclic [TC] pathways and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide [NAD] salvage pathway, suggesting decreased oxidative stress in patients achieving remission. The changes were less striking in UC.

3.4. Surgery in Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Surgical Complications and Gut Microbiota

3.4.1. Surgery and the Role of Gut Microbiota

Over the last two decades several advancements have improved IBD course and outcomes, like earlier diagnosis, introduction of disease-modifying immunosuppressive therapy and biologic agents, earlier detection and endoscopic management of colorectal neoplasia, there is still a considerable 5-year cumulative risk of surgery for such patients reaching 7% in UC and 18.0% in CD [

42]. Recently, Lewis et al described an association of dysbiosis and surgery for CD. They identified patients with a prior surgery in two different cohorts, namely the Study of a Prospective Adult Research Cohort with Inflammatory Bowel Disease [SPARC IBD] and the Diet to Induce Remission in Crohn’s Disease [DINE-CD] study, and reported that intestinal resection was associated with reduced alpha diversity and altered beta diversity with increased Proteobacteria and reduced Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes.

Additionally, the potentially beneficial Egerthella lenta, Adlercreutzia equalofaciens, and Gordonibacter pamelaeae were lower in abundance among patients with prior surgery in both cohorts [

43]. In another study investigating microbiota and metabolome changes after different surgeries for IBD, intestinal surgery seems to reduce the diversity of the gut microbiota and metabolome, and these changes may persist up to 24 months. Escherichia coli in particular expanded dramatically in relative abundance in patients undergoing surgery. Colectomy had a larger effect compared with ileocolonic resection and type of surgery explained more variation in the microbiota data than any other variable, followed by disease subtype, antibiotic use, and disease activity [

44].

3.4.2. Anastomotic Leakage and the Role of Gut Microbiota

Complications after intestinal surgery occur in approximately a third of patients. Infection and ileus are the most common short-term complications, and pouchitis and faecal incontinence the most frequent in the long term [

45]. Anastomotic leakage is a major complication leading to high morbidity and mortality. Anastomotic leakage is quite common after colorectal surgical procedures with an incidence of 2–20%, depending on the location of the anastomosis; highest rates are observed in low rectal anastomoses. Common predisposing factors are mainly host-derived [male gender, increasing age, comorbidities, malnutrition] but operation characteristics [duration of surgery, small distance of the anastomosis from the anal verge, positive intraoperative leak test] [

46]. Mechanical bowel preparation and antimicrobial prophylaxis may decrease the risk [

47]. The underlying pathophysiology is yet unclear; microbiota changes have been proposed as a potential contributor.

A growing body of evidence suggests that surgery itself can cause a significant change in the composition of the gut microbiota as a result of ischemia-reperfusion injury caused by ligation of intestinal blood vessels during surgery [

48]. Briefly, after colorectal surgery relative abundance of oral anaerobes, such as Parvimonas micra, Peptoanaerobacter stomatis, Peptostreptococcus anaerobius, Dorea longicatena, Porphyromonas uenonis, and obligate anaerobes, such as bifidobacteria, are dramatically reduced. In contrast, the number of pathogenic bacteria, such as Enterobacteriaceae, Enterococcus, Staphylococcus, and Pseudomonas, increases significantly after surgery [

49]. Anastomotic leakage is considered to be associated with gut microbiota changes; this has already been shown in various animal models suggesting common pathogens like Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterococcus faecalis as contributing factors of leakage [

50,

51,

52]. A recent study on a mice model suggests that gut microbiota influence anastomotic healing in colorectal surgery through modulation of mucosal proinflammatory cytokines such as mucosal MIP-1α, MIP-2, MCP-1 and IL-17A/F [

53], so that biopsy samples from surgical margins, rather than faecal samples, may be appropriate to explore the contribution of the intestinal microbiota to leakage [

54].

In a small cohort of 21 colon cancer patients, 5 developed anastomotic leak and showed an array of bacterial species which promoted dysbiosis, such as Acinetobacter lwoffii and Hafnia alvei. Patients with appropriate mucosal healing had an abundant microbiota of species with protective function like Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Barnesiella intestinihominis [

55]. Lehr et al concluded that after colorectal surgery, overall bacterial diversity and the abundance of some genera such as Faecalibacterium or Alistipes decreased over time, while the genera Enterococcus and Escherichia_Shigella increased.

Significant differences have been found in abundance of genera such as Prevotella, Faecalibacterium and Phocaeicola. Ruminococcus2 and Blautia showed significant ifferences in abundance even between preoperative samples indicating that they may be also predictive of postoperative complications [

56]. A recent systematic review on the role of the gut microbiota in anastomotic leakage after colorectal resection summarized results from 7 clinical and 5 experimental studies. The authors conclude that patients suffering from anastomotic leakage exhibit a diminished α-diversity of the gut microbiota and specific microbe genera, such as Lachnospiraceae, Bacteroidaceae, Bifidobacterium, Acinetobacter, Fusobacterium, Dielma, Elusimicronium, Prevotella, and Faecalibacterium, seem to be associated, whereas others like Streptococcus, Eubacterium, Enterobacteriaceae, Klebsiella, Actinobacteria, Gordonibacter, Phocaeicola, and Ruminococcus2, seem to be protective [

57].

3.4.3. Anastomotic Leakage and the Role of Biologic Agents

As TNF plays a role in angiogenesis and collagen synthesis, both essential in the wound healing process, there are some concerns that pre-operative anti-TNF treatment may influence the surgical stress response and increase the risk of surgical complications. In a prospective, multi-center cohort pilot study, 46 IBD patients undergoing major abdominal surgery were included, of which 18 received anti-TNF treatment pre-operatively. Concentration of immunological and other biomarkers of the surgical stress response [TNF, IL-6, IL-10, IL-8, IL-17A, C-reactive protein, white blood cells, cortisol, transferrin, ferritin, and D-Dimer] were measured and no difference in the concentrations was found between anti-TNF treated and anti-TNF naïve patients post-operatively.

Moreover, no difference in the rate of post-operative complications or length of stay was observed [

58]. In a retrospective study of 282 IBD patients, of which 73 patients were treated with anti-TNF therapy within 8 weeks of surgery, 30-day anastomotic leak, intra-abdominal abscess, wound infection, extra-abdominal infection, readmission, and mortality rates did not differ significantly [

59]. Similar results have been reported by others [

60,

61]. In a cohort of 417 surgically treated patients with CD in Demark in 2000-2007 however, prednisolone, contrary to biologic agents, had a negative impact on post-surgical anastomotic leak rates [

60]. In a meta-analysis of 6 studies including 1159 patients among whom 413 complications were identified, there was no significant difference in the major complication rate [OR, 1.59; 95% CI, 0.89-2.86], minor complication rate [OR,1.80; 95% CI, 0.87-3.71], reoperation rate [OR, 1.33; 95%CI, 0.55-3.20] or 30-day mortality rate [OR, 3.74; 95%CI, 0.56-25.16] between the infliximab-treated and control groups [

62]. Importantly, timing of last dose of anti-TNF agents does not affect the rate of postoperative complications in patients with IBD [

63].

4. Conclusions

Dysbiosis is key in the pathogenesis of IBD. Treatment with biologic agents has changed the natural course of disease improving patient outcomes. Changes in gut microbiota occur under treatment and specific gut microbiota signatures may be predictive of treatment response towards precision medicine. Despite advancement in treating patients with IBD, some still are at risk for surgery and subsequent complications like anastomotic leakage. Anastomotic leakage has been associated with microbiota alterations. In a mouse model of colon resection and anastomosis, infliximab-treated mice demonstrated an increase in epithelial apoptosis, consistent with the expected drug effect. Infliximab modified the perianastomotic microbiota but did not promote the emergence of collagenolytic bacteria or impair anastomotic healing [

64]. To the best of our knowledge, no other study so far has focused on the association of gut microbiota with anastomotic leakage specifically in patients with IBD.

Considering all the evidence discussed above, treatment with biologic agents in IBD may be beneficial even in patients needing surgery, preventing the development of anastomotic leakage by prior modulation of a symbiotic microbiota towards eubiosis [

Figure 2]. This is a topic of future investigation and the interplay between gut microbiota, biologic agents and postoperative anastomotic leakage in IBD remains to be answered in future animal and human studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K. and AE.M.; methodology, G.T and EV.K.; software, G.T.; validation, EL.K., AE.M. and E.F.; formal analysis, AE.M.; investigation, EV.K.; resources, EL.K.; data curation, E.F.; writing—original draft preparation, AE.M and EV.K.; writing—review and editing, EV.K.; visualization, E.F.; supervision, K.K.; project administration, K.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Acknowledgments

The Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Stem Cell Medicine is supported by a Novo Nordisk Foundation grant (NNF21CC0073729).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IBD |

Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

| SCFA |

short-chain fatty acids |

| CD |

Crohn’s Disease |

| UC |

Ulcerative Colitis |

References

- Dolinger M, Torres J, Vermeire S. Crohn's disease. Lancet. 2024; 403: 1177-1191.

- Le Berre C, Honap S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2023; 402: 571-584.

- Eckburg PB, Bik EM, Bernstein CN, Purdom E, Dethlefsen L, Sargent M, et al. Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science. 2005; 308: 1635-8.

- Frank DN, St Amand AL, Feldman RA, Boedeker EC, Harpaz N, Pace NR. Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial community imbalances in human inflammatory bowel diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 ;104: 13780-5. [CrossRef]

- Pisani A, Rausch P, Bang C, Ellul S, Tabone T, Marantidis Cordina C, et al. Dysbiosis in the Gut Microbiota in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease during Remission. Microbiol Spectr. 2022; 10: e0061622. [CrossRef]

- Machiels K, Joossens M, Sabino J, De Preter V, Arijs I, Eeckhaut V, et al. A decrease of the butyrate-producing species Roseburia hominis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii defines dysbiosis in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2014; 63: 1275-83.

- Schulthess J, Pandey S, Capitani M, Rue-Albrecht KC, Arnold I, Franchini F, et al. The Short Chain Fatty Acid Butyrate Imprints an Antimicrobial Program in Macrophages. Immunity. 2019; 50: 432-445.e7.

- Khalaf R, Sciberras M, Ellul P. The role of the fecal microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024; 36: 1249-1258. [CrossRef]

- Martín R, Rios-Covian D, Huillet E, Auger S, Khazaal S, Bermúdez-Humarán LG, et al. Faecalibacterium: a bacterial genus with promising human health applications. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2023; 47: fuad039.

- Lopez-Siles M, Martinez-Medina M, Abellà C, Busquets D, Sabat-Mir M, Duncan SH, et al. Mucosa-associated Faecalibacterium prausnitzii phylotype richness is reduced in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015; 81: 7582-92. [CrossRef]

- Touch S, Godefroy E, Rolhion N, Danne C, Oeuvray C, Straube M, et al. Human CD4+CD8α+ Tregs induced by Faecalibacterium prausnitzii protect against intestinal inflammation. JCI Insight. 2022; 7: e154722.

- Zhou L, Zhang M, Wang Y, Dorfman RG, Liu H, Yu T, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii Produces Butyrate to Maintain Th17/Treg Balance and to Ameliorate Colorectal Colitis by Inhibiting Histone Deacetylase 1. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018; 24: 1926-1940.

- Lavelle A, Sokol H. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites as key actors in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Apr;17[4]:223-237. [CrossRef]

- Varela E, Manichanh C, Gallart M, Torrejón A, Borruel N, Casellas F, et al. Colonisation by Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and maintenance of clinical remission in patients with ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013; 38: 151-61.

- Magnusson MK, Strid H, Sapnara M, Lasson A, Bajor A, Ung KA, et al. Anti-TNF Therapy Response in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis Is Associated with Colonic Antimicrobial Peptide Expression and Microbiota Composition. J Crohns Colitis. 2016; 10: 943-52. [CrossRef]

- Alexandrescu L, Nicoara AD, Tofolean DE, Herlo A, Nelson Twakor A, et al. Healing from Within: How Gut Microbiota Predicts IBD Treatment Success-A Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2024; 25: 8451.

- Schierova D, Roubalova R, Kolar M, Stehlikova Z, Rob F, Jackova Z, et al. Fecal Microbiota Changes and Specific Anti-Bacterial Response in Patients with IBD during Anti-TNF Therapy. Cells. 2021; 10: 3188. [CrossRef]

- Halfvarson J, Brislawn CJ, Lamendella R, Vázquez-Baeza Y, Walters WA, Bramer LM, et al. Dynamics of the human gut microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Microbiol. 2017; 2: 17004. [CrossRef]

- Eckenberger J, Butler JC, Bernstein CN, Shanahan F, Claesson MJ. Interactions between Medications and the Gut Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Microorganisms. 2022; 10: 1963.

- Meade S, Liu Chen Kiow J, Massaro C, Kaur G, Squirell E, Bressler B, et al. Gut microbiota-associated predictors as biomarkers of response to advanced therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Gut Microbes. 2023; 15: 2287073. [CrossRef]

- Rajca S, Grondin V, Louis E, Vernier-Massouille G, Grimaud JC, Bouhnik Y, et al. Alterations in the intestinal microbiota [dysbiosis] as a predictor of relapse after infliximab withdrawal in Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014; 20: 978-86.

- Caenepeel C, Falony G, Machiels K, Verstockt B, Goncalves PJ, Ferrante M, et al. Dysbiosis and Associated Stool Features Improve Prediction of Response to Biological Therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology. 2024; 166: 483-495.

- Zhou Y, Xu ZZ, He Y, Yang Y, Liu L, Lin Q, et al. Gut Microbiota Offers Universal Biomarkers across Ethnicity in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Diagnosis and Infliximab Response Prediction. mSystems. 2018; 3: e00188-17. [CrossRef]

- Ding NS, McDonald JAK, Perdones-Montero A, Rees DN, Adegbola SO, Misra R, et al. Metabonomics and the Gut Microbiota Associated with Primary Response to Anti-TNF Therapy in Crohn's Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2020; 14: 1090-1102.

- Busquets D, Mas-de-Xaxars T, López-Siles M, Martínez-Medina M, Bahí A, Sàbat M, et al. Anti-tumour Necrosis Factor Treatment with Adalimumab Induces Changes in the Microbiota of Crohn's Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2015; 9:899-906. [CrossRef]

- Ribaldone DG, Caviglia GP, Abdulle A, Pellicano R, Ditto MC, Morino M, et al. Adalimumab Therapy Improves Intestinal Dysbiosis in Crohn's Disease. J Clin Med. 2019; 8: 1646.

- Chen L, Lu Z, Kang D, Feng Z, Li G, Sun M, et al. Distinct alterations of fecal microbiota refer to the efficacy of adalimumab in Crohn's disease. Front Pharmacol. 2022; 13: 913720. [CrossRef]

- Oh HN, Shin SY, Kim JH, Baek J, Kim HJ, Lee KM, et al. Dynamic changes in the gut microbiota composition during adalimumab therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis: implications for treatment response prediction and therapeutic targets. Gut Pathog. 2024; 16: 44. [CrossRef]

- Sakurai T, Nishiyama H, Sakai K, De Velasco MA, Nagai T, Komeda Y, et al. Mucosal microbiota and gene expression are associated with long-term remission after discontinuation of adalimumab in ulcerative colitis. Sci Rep. 2020; 10: 19186.

- Aden K, Rehman A, Waschina S, Pan WH, Walker A, Lucio M, et al. Metabolic Functions of Gut Microbes Associate with Efficacy of Tumor Necrosis Factor Antagonists in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology. 2019; 157: 1279-1292.e11. [CrossRef]

- Ditto MC, Parisi S, Landolfi G, Borrelli R, Realmuto C, Finucci A, et al. Intestinal microbiota changes induced by TNF-inhibitors in IBD-related spondyloarthritis. RMD Open. 2021; 7: e001755.

- Zhuang X, Tian Z, Feng R, Li M, Li T, Zhou G, et al. Fecal Microbiota Alterations Associated With Clinical and Endoscopic Response to Infliximab Therapy in Crohn's Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020; 26: 1636-1647. [CrossRef]

- Sanchis-Artero L, Martínez-Blanch JF, Manresa-Vera S, Cortés-Castell E, Valls-Gandia M, Iborra M, et al. Evaluation of changes in intestinal microbiota in Crohn's disease patients after anti-TNF alpha treatment. Sci Rep. 2021; 11: 10016. [CrossRef]

- Seong G, Kim N, Joung JG, Kim ER, Chang DK, Chun Jet al. Changes in the Intestinal Microbiota of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease with Clinical Remission during an 8-Week Infliximab Infusion Cycle. Microorganisms. 2020; 8: 874.

- Tamburini FB, Tripathi A, Gold MP, Yang JC, Biancalani T, McBride JM, et al. Gut Microbial Species and Endotypes Associate with Remission in Ulcerative Colitis Patients Treated with Anti-TNF or Anti-integrin Therapy. J Crohns Colitis. 2024; 18: 1819-1831. [CrossRef]

- Rob F, Schierova D, Stehlikova Z, Kreisinger J, Roubalova R, Coufal S, et al. Association between ustekinumab therapy and changes in specific anti-microbial response, serum biomarkers, and microbiota composition in patients with IBD: A pilot study. PLoS One. 2022; 17: e0277576.

- Doherty MK, Ding T, Koumpouras C, Telesco SE, Monast C, Das A, et al. Fecal Microbiota Signatures Are Associated with Response to Ustekinumab Therapy among Crohn's Disease Patients. mBio. 2018; 9: e02120-17. [CrossRef]

- Xu F, Xie R, He L, Wang H, Zhu Y, Yang X, Yu H. Oral Microbiota Associated with Clinical Efficacy of Ustekinumab in Crohn's Disease. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2025 Jan 13. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Fang H, Hong N, Lv C, Zhu Q, Feng Y, et al. Gut Microbiota and Metabonomic Profile Predict Early Remission to Anti-Integrin Therapy in Patients with Moderate to Severe Ulcerative Colitis. Microbiol Spectr. 2023; 11: e0145723.

- Ananthakrishnan AN, Luo C, Yajnik V, Khalili H, Garber JJ, Stevens BW, et al. Gut Microbiota Function Predicts Response to Anti-integrin Biologic Therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Cell Host Microbe. 2017; 21: 603-610.e3. [CrossRef]

- Hu Y, Wu Z, Yang X, Ding J, Wang Q, Fang H, et al. Reduced gut microbiota diversity in ulcerative colitis patients with latent tuberculosis infection during vedolizumab therapy: insights on prophylactic anti-tuberculosis effects. BMC Microbiol. 2024; 24: 543.

- Tsai L, Ma C, Dulai PS, Prokop LJ, Eisenstein S, Ramamoorthy SL, et al. Contemporary Risk of Surgery in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn's Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Population-Based Cohorts. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021; 19: 2031-2045.e11.

- Lewis JD, Daniel SG, Li H, Hao F, Patterson AD, Hecht AL, et al. Surgery for Crohn's Disease Is Associated With a Dysbiotic Microbiota and Metabolome: Results From Two Prospective Cohorts. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024; 18: 101357. [CrossRef]

- Fang X, Vázquez-Baeza Y, Elijah E, Vargas F, Ackermann G, Humphrey G, et al. Gastrointestinal Surgery for Inflammatory Bowel Disease Persistently Lowers Microbiota and Metabolome Diversity. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021; 27: 603-616.

- Murphy PB, Khot Z, Vogt KN, Ott M, Dubois L. Quality of Life After Total Proctocolectomy With Ileostomy or IPAA: A Systematic Review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015; 58: 899-908.

- McDermott FD, Heeney A, Kelly ME, Steele RJ, Carlson GL, Winter DC. Systematic review of preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative risk factors for colorectal anastomotic leaks. Br J Surg. 2015; 102: 462-79. [CrossRef]

- Hansen RB, Balachandran R, Valsamidis TN, Iversen LH. The role of preoperative mechanical bowel preparation and oral antibiotics in prevention of anastomotic leakage following restorative resection for primary rectal cancer - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2023; 38: 129.

- Liu Y, Li B, Wei Y. New understanding of gut microbiota and colorectal anastomosis leak: A collaborative review of the current concepts. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022; 12: 1022603. [CrossRef]

- Shi Y, Cui H, Wang F, Zhang Y, Xu Q, Liu D, et al. Role of gut microbiota in postoperative complications and prognosis of gastrointestinal surgery: A narrative review. Medicine [Baltimore]. 2022; 101: e29826.

- Olivas AD, Shogan BD, Valuckaite V, Zaborin A, Belogortseva N, Musch M, et al. Intestinal tissues induce an SNP mutation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa that enhances its virulence: possible role in anastomotic leak. PLoS One. 2012; 7: e44326. [CrossRef]

- Shogan BD, Belogortseva N, Luong PM, Zaborin A, Lax S, Bethel C, et al. Collagen degradation and MMP9 activation by Enterococcus faecalis contribute to intestinal anastomotic leak. Sci Transl Med. 2015; 7: 286ra68.

- Schardey HM, Kamps T, Rau HG, Gatermann S, Baretton G, Schildberg FW. Bacteria: a major pathogenic factor for anastomotic insufficiency. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994; 38: 2564-7. [CrossRef]

- Hajjar R, Gonzalez E, Fragoso G, Oliero M, Alaoui AA, Calvé A, et al. Gut microbiota influence anastomotic healing in colorectal cancer surgery through modulation of mucosal proinflammatory cytokines. Gut. 2023; 72: 1143-1154.

- Hernández-González PI, Barquín J, Ortega-Ferrete A, Patón V, Ponce-Alonso M, Romero-Hernández B, et al. Anastomotic leak in colorectal cancer surgery: Contribution of gut microbiota and prediction approaches. Colorectal Dis. 2023; 25: 2187-2197. [CrossRef]

- Palmisano S, Campisciano G, Iacuzzo C, Bonadio L, Zucca A, Cosola D, et al. Role of preoperative gut microbiota on colorectal anastomotic leakage: preliminary results. Updates Surg. 2020; 72: 1013-1022.

- Lehr K, Lange UG, Hipler NM, Vilchez-Vargas R, Hoffmeister A, Feisthammel J, et al. Prediction of anastomotic insufficiency based on the mucosal microbiota prior to colorectal surgery: a proof-of-principle study. Sci Rep. 2024; 14: 15335. [CrossRef]

- Lianos GD, Frountzas M, Kyrochristou ID, Sakarellos P, Tatsis V, Kyrochristou GD, et al. What Is the Role of the Gut Microbiota in Anastomotic Leakage After Colorectal Resection? A Scoping Review of Clinical and Experimental Studies. J Clin Med. 2024; 13: 6634.

- El-Hussuna A, Qvist N, Zangenberg MS, Langkilde A, Siersma V, Hjort S, et al. No effect of anti-TNF-α agents on the surgical stress response in patients with inflammatory bowel disease undergoing bowel resections: a prospective multi-center pilot study. BMC Surg. 2018; 18: 91.

- Shwaartz C, Fields AC, Sobrero M, Cohen BD, Divino CM. Effect of Anti-TNF Agents on Postoperative Outcomes in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients: A Single Institution Experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016; 20: 1636-42. [CrossRef]

- El-Hussuna A, Andersen J, Bisgaard T, Jess P, Henriksen M, Oehlenschlager J, et al. Biologic treatment or immunomodulation is not associated with postoperative anastomotic complications in abdominal surgery for Crohn's disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012; 47: 662-8.

- Kunitake H, Hodin R, Shellito PC, Sands BE, Korzenik J, Bordeianou L. Perioperative treatment with infliximab in patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis is not associated with an increased rate of postoperative complications. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008; 12: 1730-6; discussion 1736-7. [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld G, Qian H, Bressler B. The risks of post-operative complications following pre-operative infliximab therapy for Crohn's disease in patients undergoing abdominal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2013; 7: 868-77.

- Alsaleh A, Gaidos JK, Kang L, Kuemmerle JF. Timing of Last Preoperative Dose of Infliximab Does Not Increase Postoperative Complications in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2016; 61: 2602-7. [CrossRef]

- Gaines S, Hyoju S, Williamson AJ, van Praagh JB, Zaborina O, Rubin DT, et al. Infliximab Does Not Promote the Presence of Collagenolytic Bacteria in a Mouse Model of Colorectal Anastomosis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020; 24: 2637-2642. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).