1. Introduction

Tropospheric ozone (O3) is the most damaging air pollutant for plants (Fares et al., 2012; Wedow et al., 2021). Ozone damages ecosystem vegetation carbon sequestration, carbon allocation, nutrient supply, biodiversity and other aspects (Grulke and Heath, 2019; Li et al., 2016). As plants play a vital role in regulating the ambient environment, ozone-induced damage in plants may further accelerate environmental degradation, with severe consequences for human and ecosystem health. The few studies that have considered the effects of ozone on the carbon cycle still lack simulations of the interaction of ozone with various global change factors. As a result, we know little about the interaction of multiple global change factors on ecosystem carbon cycle.

The interaction mechanism of global change factors is very complex. Climate change affects the carbon cycle of terrestrial ecosystems directly or indirectly by changing temperature, precipitation and other factors (Hao et al., 2019; Hu et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2022; Xie et al., 2020; Xuejuan et al., 2017). CO2 fertilization not only increases the photosynthetic rate of plants but also reduces the risk of drought by reducing stomatal conductance (Jarvis, 1976; Schimel et al., 2015). Many previous studies have reported that CO2 fertilization offsets the possible negative effects of climate change (Porter et al., 2014). It is because the effect of CO2 fertilization increases the leaf intercellular concentration of carbon dioxide and stimulates the photosynthesis of plants (Haworth et al., 2023; Johansson et al., 2020). Although the fossil record and experiments showed that high concentrations of CO2 reduce stomatal pore size and total stomatal number per unit leaf area, this reduction in stomatal conductance does not affect the high intercellular CO2 concentration during vegetation photosynthesis, which is even higher than predicted by most models (Engineer et al., 2016; Azoulay Shemer et al., 2015; Keenan et al., 2013). However, emissions of CO2 are usually accompanied by O3 precursors, which have driven a rise in tropospheric ozone ([O3]) (IPCC, 2014). O3 forms reactive oxygen species (ROS) within cells, causing damage to plant tissues and reduced photosynthesis (Saxena et al., 2019; Pellegrini et al., 2019; Zapletal et al.,2018). In addition, ozone exposure altered the content of abscisic acid and K+ ions in plant stomatal cells, causing expansion pressure and abnormal signaling in plant guard cells (Calatayud et al.,2011; Paoletti and Grulke, 2005). Ozone disrupts plant photosynthesis, reduces gas exchange, induces early leaf senescence, and inhibits the growth of natural vegetation and crops (Feng et al., 2011; Fusaro et al., 2017; Hayes et al., 2021; Leung et al., 2020; Li et al., 2022; Li et al., 2022; Seltzer et al., 2020; Tai et al., 2014). It can be seen that the effects of [CO2] and [O3] on plants are very complex, although some scholars believe that the increase of [CO2] can reduce the impact of [O3] on vegetation(Tao et al., 2017).However, few models take the synergistic effects of CO2, O3 climate change and other factors into consideration in the simulation (Tai et al., 2021). Because the effects of different factors on vegetation are very complicated, it is difficult to express them by simple functions. The process-based ecosystem models considering process can help us understand the response and adaptation of vegetation under the influence of global change factors by simulating the physiological change process of vegetation and output intermediate variables (Mo et al., 2018; Feng et al., 2007). Therefore, it is necessary to consider multifactor modeling and reveal the interaction of global change factors based on the model.

In China, studies based on multiple variability factors have mostly focused on the effects of O3 and CO2 changes on crop yields (Tao et al., 2017), and research on carbon sinks in terrestrial ecosystems is lacking (Ren et al., 2007; Tian et al., 2011). (Ren et al., 2007; Ren et al., 2011) simulated the net primary productivity (NPP) and net carbon exchange (NCE) of terrestrial ecosystems in China and showed that the rise of O3 led to a 7.7% decrease in carbon storage in China and an average 4.5% decrease in national NPP. NCE (Pg C yr-1) decreases by 0.4-43.1% for different forest types, and carbon dioxide and nitrogen deposition will offset the damage to ecosystem productivity caused by ozone and climate change. With the increase in atmospheric emissions, the concentrations of CO2 and O3 are increasing. Given the response of vegetation to changing atmospheric conditions, previous findings may no longer be relevant in the current climate. It is necessary and urgent to simulate the carbon sink of terrestrial ecosystems with multifactor interactions. Revealing the interaction mechanism of multiple factors will help us understand the changing trend of terrestrial ecosystem productivity under future climate change.

In this study, we quantify the impacts of different global change factors on the ecosystem carbon cycle through the comparison of multi-scenario models, and try to find out the mechanism of their interaction. Therefore, the BEPS model was used to (1) calculate the GPP of woodland ecosystems in China under different scenarios from 2001 to 2020; (2) calculate the influence of ozone and different factors on GPP by comparing different scenarios; and (3) explore the interaction mechanism of different global change factors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Model Description

The boreal ecosystem productivity simulator (BEPS) is a process-based ecosystem model with half-hourly time steps developed by Liu and (Chen et al., 1999). The model consists of an energy transfer module, carbon cycle module, water cycle module and physiological regulation module. The two-leaf enzyme kinetic terrestrial ecosystem model included a module for leaf photosynthesis and stomatal conductance calculations to simulate GPP in the BEPS model (Chen et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2012). In BEPS, the canopy-level GPP is simulated as follows (Chen et al., 1999):

where

A is the leaf-level net photosynthesis rate (u mol/m

2 s). The sunlit LAI (LAI

sun) and shaded LAI (LAI

sh) are calculated as follows (Chen

et al., 1999):

where

is the solar zenith angle and L is the leaf area index (m

2 m

-2).

Following (Farquhar et al., 1982), the net carboxylation rate at the leaf level is calculated as the minimum of

and

where

Ac,i and

Aj,i are Rubiso-limited and RuBP-limited gross photosynthesis rates (μ mol/m

2 s), respectively.

Vcmax is the maximum carboxylation rate (μ mol/m

2 s);

J is the electron transport rate (μ mol/m

2 s);

Cc,i and

Oc,i are the intercellular CO

2 and O

2 mole fractions (mol/mol, respectively);

is the CO

2 compensation point without dark respiration (mol/mol;

Kc and Ko are Michaelis–Menten constants for CO

2 and O

2 (mol/mol), respectively.

To assess the effects of ozone on vegetation productivity, the photosynthesis module in the BEPS model was improved (ANAV et al., 2011; Anav et al., 2018; Oliver et al., 2018; Sitch et al., 2007).

where

A is the photosynthetic rate affected by ozone,

Ap is the original photosynthetic rate, and F represents the fractional reduction in plant production, which was calculated based on the

PODy flux index.

F can be expressed as:

where

PODy is the instantaneous leaf uptake of O

3 over a vegetation-specific threshold, y, in nmol/m

2 s. The fractional reduction in photosynthesis with O

3 uptake by leaves is represented by the vegetation type-specific parameter,

α. (

Table 1), and

PODy can be expressed as

where

R is the aerodynamic and boundary layer resistance between the leaf surface and reference level (s/m),

g is the leaf conductance for H

2O (m/s), and

kO3=1.67 is the ratio of leaf resistance for O

3 to leaf resistance for water vapor. The final

PODy is calculated by the two-leaf model at the leaf scale and then scaled to the canopy level. The NPP of vegetation is generally expressed as the difference between GPP and autotrophic respiration:

The autotrophic respiration (Ra) of vegetation is divided into two parts: respiration for growth (Rg) and respiration for maintenance of basic metabolism (Rh). Respiration for growth (Rg) is generally considered to be 20% of GPP, and respiration for basal metabolism (Rh) is temperature dependent.

2.2. Data Sources

2.2.1. Gridded Meteorological Data

The hourly gridded reanalysis meteorological data (ERA5) were downloaded from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) (10.24381/cds.e2161bac) and included air temperature, precipitation, wind speed, humidity ratio, downward solar radiation and ozone concentration. ERA5 is based on the Integrated Forecasting System (IFS) Cy41r2, which was operational in 2016. ERA5 thus benefits from a decade of developments in model physics, core dynamics and data assimilation (Hersbach et al., 2020). In addition to a significantly enhanced horizontal resolution of 31 km, compared to 80 km for ERA-Interim, ERA5 has hourly output throughout and an uncertainty estimate from an ensemble (3-hourly at half the horizontal resolution) (Bell et al., 2021). The gridded meteorological data are at 0.25° spatial resolution, and they were resampled to 0.1° spatial resolution in this study by bilinear interpolation.

2.2.2. China-Wide LAI Map

The LAI data were retrieved from the GLOBMAP leaf area index (LAI) dataset (Version 3), which can be downloaded from the Zenodo website (

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4700264) (Liu et al., 2012). The GLOBMAP LAI was a consistent long-term global LAI product (1981–2020) derived by quantitative fusion of Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) and historical Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) data. The GLOBMAP LAI dataset has been validated with field measurements, which have an error of 0.81 LAI on average (Liu et al., 2012). The LAI data were resampled from 8 km to 0.1° spatial resolution in this study.

2.2.3. Land Cover Map

The land cover map was obtained from the National Earth System Science Data Center (

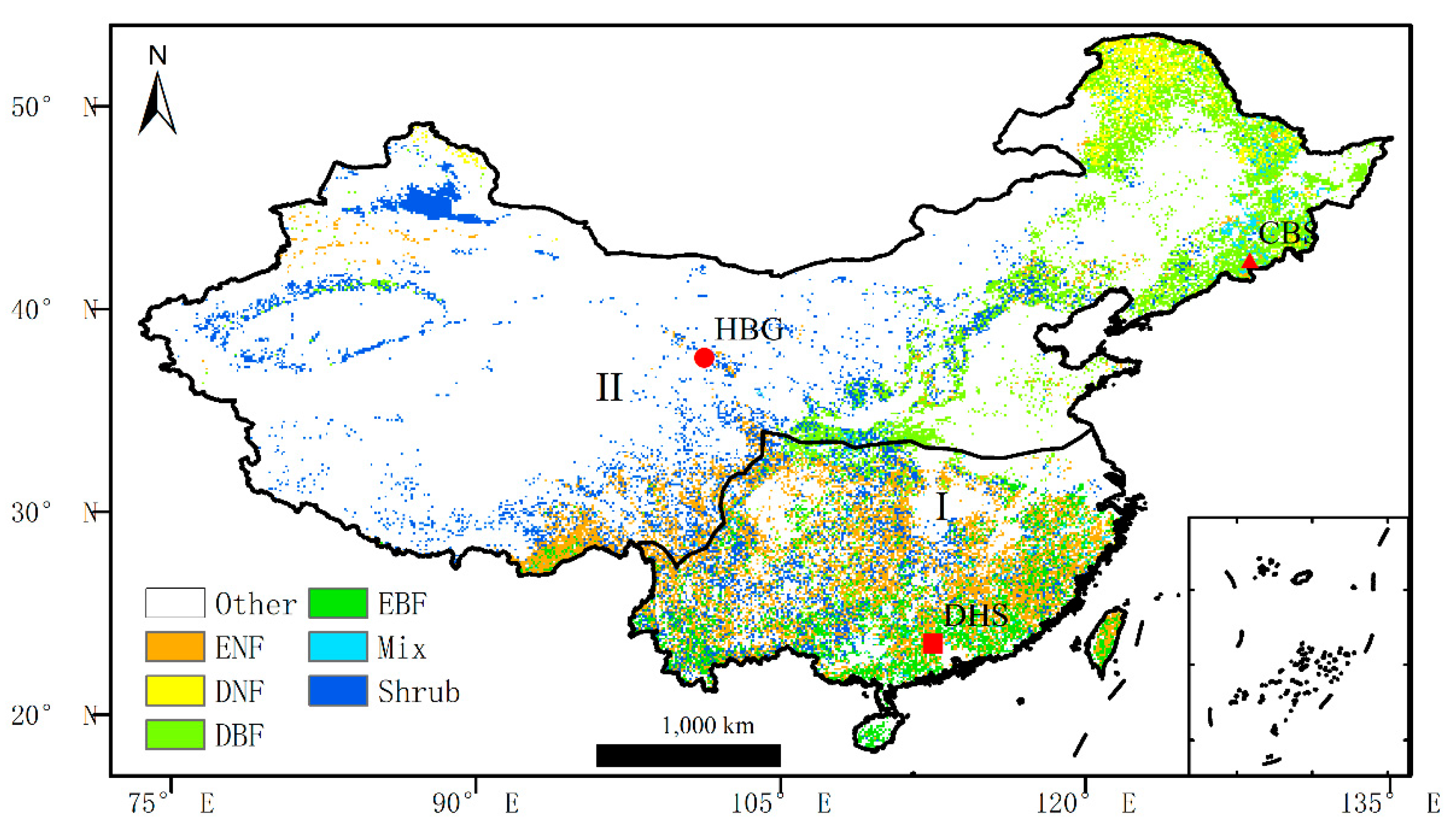

http://www.geodata.cn/) by (Bo et al., 2014). The vegetation cover of China has been divided into 38 types, and we reclassified the land cover map into seven vegetation types, including evergreen needleleaf forest (ENF), deciduous needleleaf forest (DNF), deciduous broadleaf forest (DBF), evergreen broadleaf forest (EBF), mixed forest (MIX) and shrub (Fig. 1). Considering the differences in the sensitivity of temperate and subtropical plants to ozone, we distinguished between subtropical and temperate vegetation. In this study, we did not consider the change in land use, so only the land cover map drawn in 2000 was used.

2.2.4. Site Verification

Three flux sites were used to validate the GPP simulated by the BEPS_O

3 model. The three stations are HaiBei Station (shrub-HBG), Changbaishan Station (conifer-CBS) and Dinghushan Station (hardleaf -DHS). GPP data for all three sites came from ChinaFlux.

Figure 1 shows the locations of the three sites, and

Table 1 shows the basic information about the three sites.

2.3. Simulation Protocol

The validated BEPS_O

3 model was applied to simulate the interaction effects of climate change, [CO

2] and [O

3] on the GPP of woodland ecosystems during 2001-2020. Through model simulation experiments, the interactive effects of [CO

2] and [O

3] on the woodland ecosystem GPP under the background of historical climate change were studied. The relative effects of climate change, [CO

2] and [O

3] on the woodland ecosystem GPP were also clarified. As a model simulation experiment scheme (

Table 2), (E1) studied productivity under historical climate change conditions. Model simulation Experiment 2 (E2) studied productivity under historical climate, [O

3] and [CO

2] conditions. Model simulation Experiment 3 (E3) studied productivity under historical O

3 and climatic conditions. Model simulation Experiment 4 (E4) examined productivity under historical climatic conditions and CO

2 conditions.

By comparing E1 and E2, the comprehensive effects of past climate change, carbon dioxide and ozone on vegetation can be obtained. The combined effects of ozone and climate change on vegetation can be obtained by comparing E1 and E3. The combined effects of carbon dioxide fertilization and climate change on vegetation can be obtained by comparing E1 and E4. The separate effects of ozone on vegetation can be determined by comparing E2 and E4.

In scenarios E1 and E3, we used the fixed CO2 concentration in 2001 as the CO2 input data of the model.

2.4. Causality Analysis-SURD

The SURD analysis method was used for the simulation results. SURD is a component that decomposes causal relationships into collaborative relationships, uniqueness, and redundancy(Martínez-Sánchez et al., 2024). SURD quantifies causality as the increments of redundant(R), unique(U), and synergistic(S) information gained about future events from past observations. It is conducive to exploring the influence process of factors such as ozone-meteorological factors and carbon dioxide on the productivity of the woodland ecosystem over a long time series.

The original SURD component was only used for analyzing the site. The SURD component was compiled based on Python to be used for temporal causal analysis of region-scale raster data. The time series of each meteorological variable is constructed in a single grid to analyze the causal relationship between GPP. In result presentation, since each variable will generate R, U and S causal relationships with other variables, fully presenting the causal relationships of the data is a huge and complex process.

This study focuses on demonstrating the causal relationship between O3 and CO2 and GPP. Firstlly, obtain the causal relationship analysis of all variables through SURD; Secondly, split into R, U and S relationships; Thirdly, extract the variable combinations with the maximum values in R, U and S respectively to determine whether the ids corresponding to CO2 and O3 exist among them. If ids exist, pass out the values. The causal relationship of the specified variable is presented through filtering, eliminating the complex process of plotting and data filtering.

3. Result

3.1. Site Verification of the GPP Simulated by the BEPS_O3 Model

For information about parameter acquisition and parameter verification, see the supplementary materials section. Based on limited site data, we verify the GPP simulated by the BEPS_O3 model at the site scale. Validation results are mainly from previous studies (Wang et al., 2023). We obtained GPP observational flux data from ChinaFlux at HaiBei Station (shrub-HBG), Changbaishan Station (conifer-CBS) and Dinghushan Station (hardleaf -DHS) to verify the simulation results of the model (Figure S1, Figure S2). The results of GPP simulated by BEPS_O3 are similar to GPP simulated by BEPS model at site scale, but still show a slight improvement. Especially in summer, it restrains the overestimation of GPP. At Haibei Station (HBG), BEPS_O3 decreased the slope from 1.26 to 1.05, R2 increased by 0.02, and RMSE decreased by 0.26. Although both models underestimated GPP at Dinghushan Station (DHS), BEPS_O3 reduced the intercept from 2.3 to 1.2. The improvement at Changbaishan (CBS) was demonstrated by a decrease in slope and 0.01 increase in R2. The BEPS_O3 model shows good correlation with GPP at the site scale and can reflect the seasonal variation in GPP.

3.2. Individual and Synergistic Effects of Climate Change, CO2 and O3

Daytime ozone concentrations have maintained a gradual increasing trend over the past two decades (we averaged the ozone concentrations for all periods with radiation greater than 50 w/m2 per hour step per day for each grid to find the annual average time distribution of ozone concentrations) (Figure S3). The average ozone concentration in the study area increased from 62 ppb in the 2001s (2001-2010) to 65 ppb in the 2010s (2010-2020). The Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and northern regions showed the largest increase in ozone concentration, with the eastern coastal region increasing by approximately 6% and the southwestern region by approximately 2%. Changes in atmospheric CO2 concentrations are derived from IPCC historical CO2 concentration data, with mean CO2 concentrations increasing from 371 ppm in 2000 to 412 ppm in 2020 (Figure S4). Under the historical climate change scenario, compared with the 2001s the average daily temperature in the 2010s will generally increase by 0.5-2 ℃, and the radiation will change by -2.5-3%, relative humidity by -1-3.8%, and precipitation by -40-50% (Figure S5).

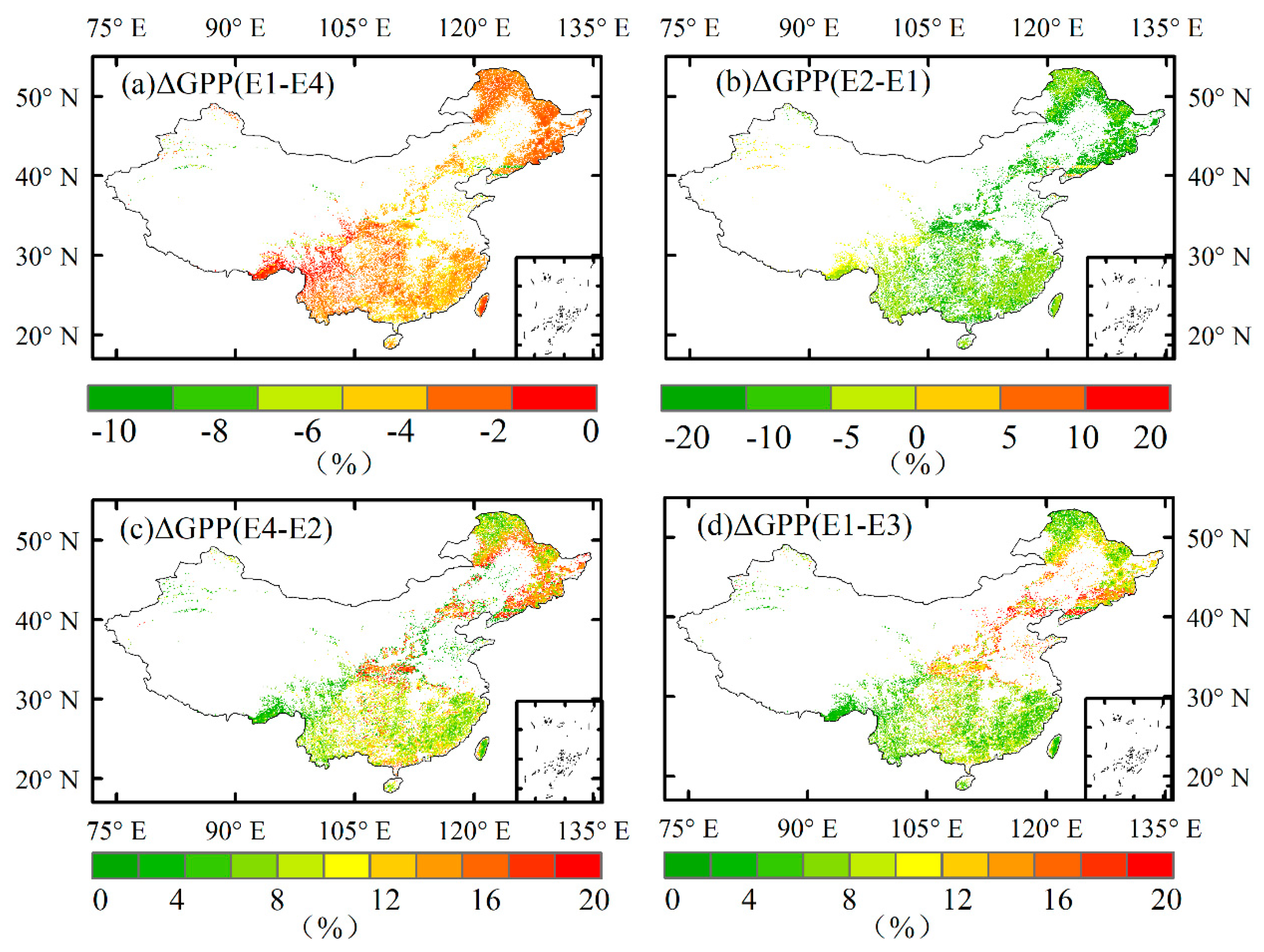

In the historical climate change scenario, excluding the effects of [O

3] and [CO

2], climate change will lead to a -10-20% change in forest GPP. The forest GPP showed a downward trend in some subtropical regions, while the other regions showed an increase in GPP. Under historical climate conditions, the GPP loss caused by single [O

3] is approximately 0-22%, and the synergistic effect of [O

3] and [CO

2] is relatively small, approximately 0-18%, which is 2-4% smaller than the effect of single [O

3] in the study area (

Figure 2c, d). With the increase in ozone concentration, the GPP loss under the influence of single [O

3] was 1.9-13.2% in the 2001s and 1.9-11.9% in the 2010s (Figure S6). The GPP loss under the synergistic action of [O

3] and [CO

2] is 3.1-17% and 3.2-15%, respectively. CO

2 mitigated the effect of O

3 to a certain extent. The effect of O

3 on the ecosystem may be greater than the GPP gain of the forest ecosystem caused by CO

2 fertilization (Figure. S7).

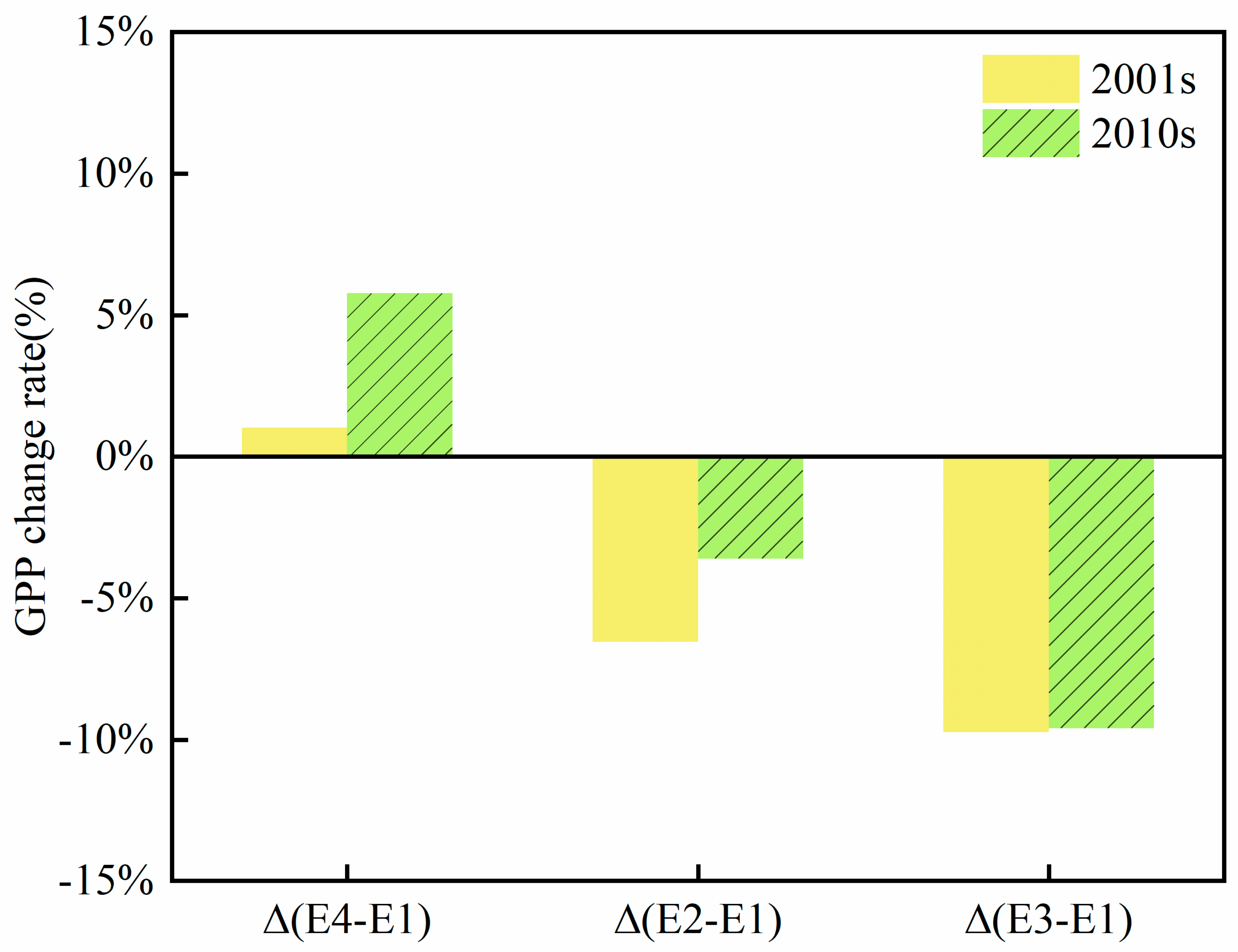

As the BEPS_O

3 model is a process model driven by remote sensing data, the leaf area index (LAI), as input data, includes the promoting effect of climate change and some carbon dioxide fertilization on vegetation (Chen et al., 2007; Li et al., 2018). Therefore, we cannot obtain the impact of climate change on GPP by comparing the 2001s and 2010s GPP. However, it is still possible to calculate the synergistic effects of climate change and other factors on vegetation. The synergistic effect of [O

3] and climate change will lead to more severe GPP reductions across the study area, with average annual GPP losses in the 2010s higher than those in the 2001s (0.9% and 1%). [CO

2] and climate change significantly increased forest GPP by 1% and 5%, respectively. Under the synergistic effect of [O

3], [CO

2] and climate change, the effect of [O

3] offset the enhancement of [CO

2] on photosynthesis and still led to the decline in GPP, but the elevated [CO

2] mitigated the loss of GPP caused by [O

3] to a large extent (

Figure 3).

Overall, although the GPP loss rate caused by ozone pollution from 2001-2020 decreased, the GPP loss amount showed an increasing trend. This may be due to the overall increase in the total amount of GPP between 2001 and 2020.In terms of regional variation, GPP changes caused by [O3] and [CO2] are controlled by climate. Subtropical regions are rich in temperature and precipitation, and vegetation is mainly limited to [CO2] and [O3]. The single effect of [O3] and [CO2] has a great influence in regions with abundant precipitation and high temperature. The stomatal conductance of vegetation in northern China is limited by temperature and precipitation, and ozone uptake is low. Thus, the synergistic effect of [O3] and [CO2] still shows an increase in GPP (Launiainen et al., 2022).

4. Discussion

4.1. The Synergistic Effect of O3 and CO2

Based on the previous statistical results, we found that there is a significant difference between [CO2] and [O3] on woodland GPP singly and in combination. Woodland GPP showed a significant upward trend under the synergistic action of climate and [CO2]. This is because the promotion of vegetation photosynthesis by [CO2] increases forest GPP, and this effect continues to increase with increasing CO2 (Sun 2019; Piao 2013; Zhu, 2017). The effect of CO2 fertilization increases GPP by 1-5% over 20 years, which is close to the results of Piao et al. (2013) based on multiple model comparisons. In contrast, observations based on global carbon flux sites (0.138 ± 0.007% ppm−1; percentile per rising ppm of CO2) were slightly higher than those in our study (Ueyama et al., 2020). This may be because the input LAI recorded the increase in vegetation leaf area caused by the CO2 fertilization effect.

Without considering the elevated [CO2], the GPP loss caused by [O3] and climate change showed a slow increasing trend, while the loss rate showed a slow decrease. This is consistent with the findings of Sitch (2007) and Oliver (2018). O3 concentrations have increased over the past 20 years, but mainly in temperate regions of China. Woodland in temperate areas may be stressed by drought, O3 and other factors at the same time, and the decrease in stomatal conductance caused by drought stress may limit ozone uptake by vegetation (Otu-Larbi et al., 2020; Ren et al., 2007).

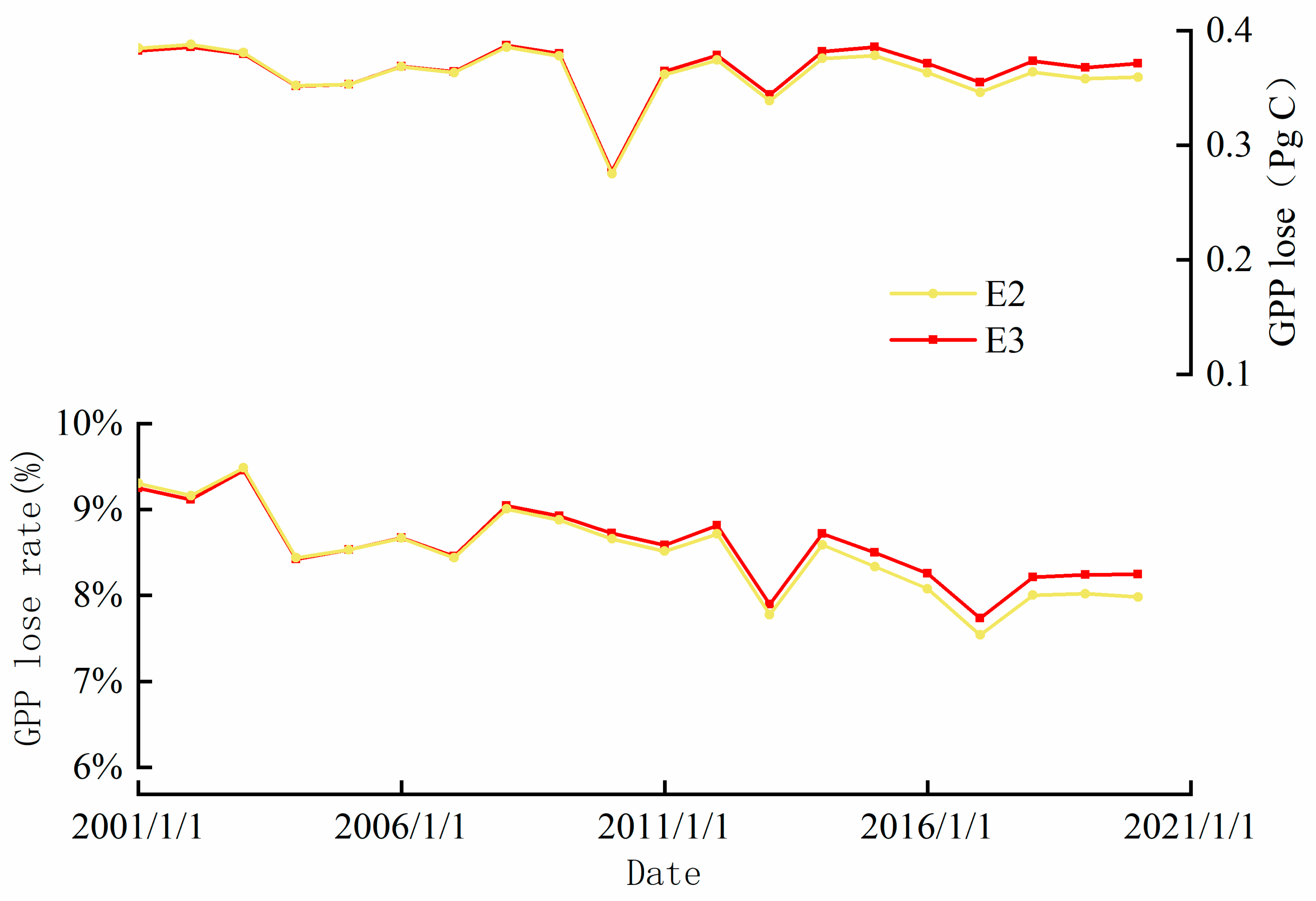

In contrast, the synergistic effect of [CO

2] and [O

3] on GPP decreased more slowly. After 2006, the loss of GPP caused by [O

3] alone exceeded the loss of GPP caused by the synergistic action of [O

3] and [CO

2] (

Figure 4). Therefore, we compared the mean ozone uptake by vegetation stomata under single [O

3] and [CO

2+O

3] scenarios (Figure S10a). With the increase in CO

2 concentration, ozone uptake by vegetation stomata gradually decreased (Figure S8b). This indicates that the synergistic effect of [CO

2] and [O

3] may cause a decrease in canopy conductance and prevent O

3 uptake by vegetation stomata (Engineer et al., 2016; Keenan et al., 2013; Tao et al., 2017). Field observation experiments have proven the adaptability of vegetation photosynthesis to the increase in CO

2, and the change in stomatal conductance cannot affect the intercellular CO

2 concentration of vegetation, but the adaptation of stomata to [CO

2] has not been found (Ainsworth and Long, 2005; Azoulay Shemer et al., 2015). This result is supported by Oliver et al. (2018), whose estimates of GPP in European ecosystems demonstrate that elevated [CO

2] offsets [O

3] damage to GPP. The studies of Tao (2017) and Tai (2021) on crop yield also reached a similar conclusion. Although the damage of [O

3] on ecosystem GPP was greater than the gain of the CO

2 fertilization effect on the ecosystem, CO

2 gradually weakened the effect of ozone.

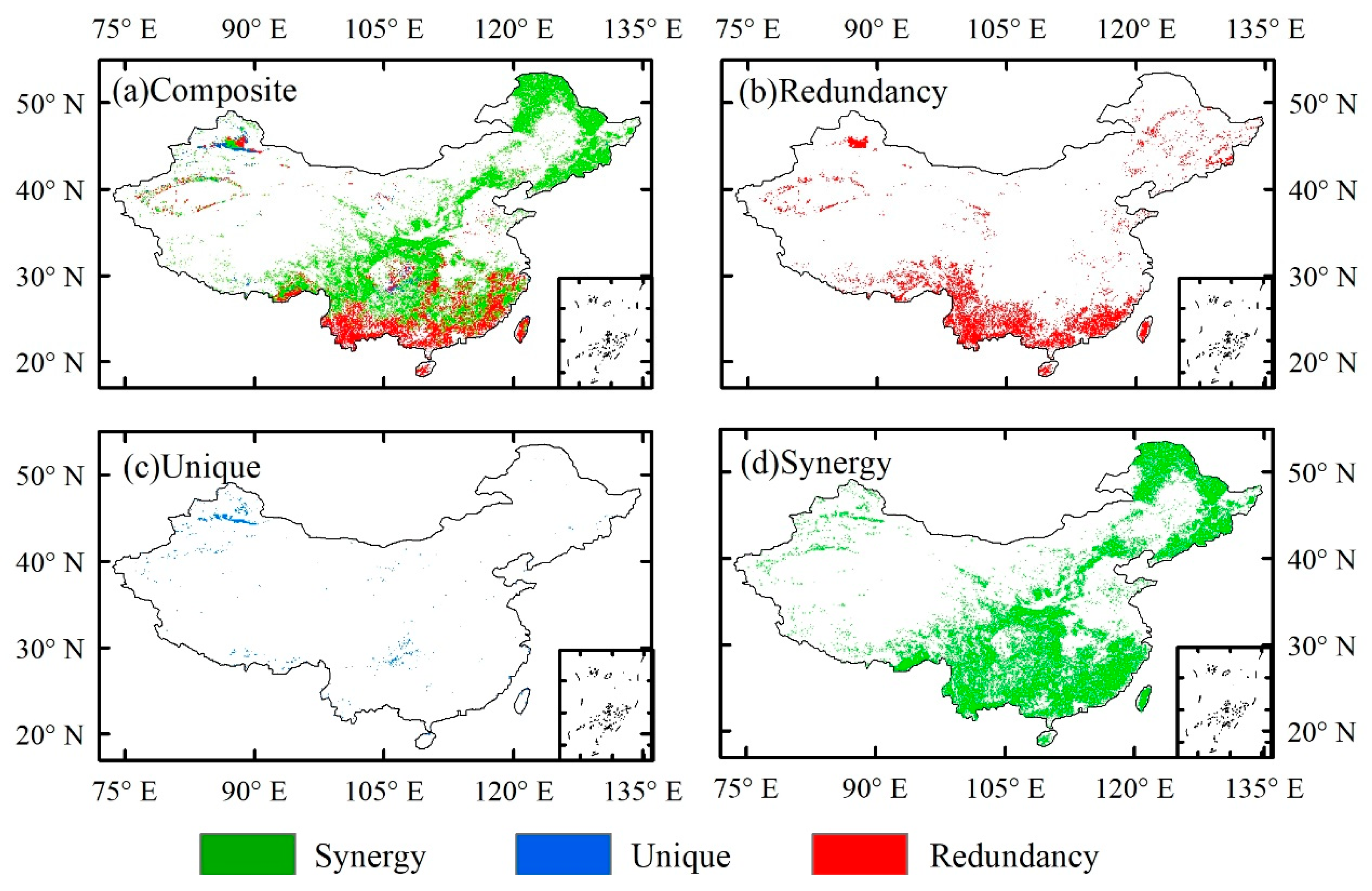

The results of causal analysis also well reveal the synergistic effect of O

3 and CO

2, as shown in

Figure 5. Most forest areas show a synergistic effect of O

3 and CO

2, some areas show a redundant effect of CO

2 and O

3, and only a few grids show uniqueness. This indicates that among the combination of meteorological factors that have the greatest impact on GPP, CO

2 and O

3 play a major role. Although subtropical regions are affected by ozone pollution, the better water and heat conditions result in the fact that the impact of ozone on GPP is not obvious. Therefore, the redundant effects of O

3 and CO

2 on GPP are mainly concentrated in subtropical regions. With the changes of water and heat conditions, O

3 and CO

2 show obvious synergistic regulatory effects in temperate regions.

4.2. Discussion on the Synergistic Mechanism of O3 and CO2

The effect of CO2 fertilization was mainly caused by the higher affinity of Rubisco for CO2. Because lacking of the CO2 concentration mechanism C3 plant cells, more photorespiration products were invested in the production of Rubisco (Tcherkez et al., 2006; Ainsworth and Rogers, 2007), as [CO2] rises, control of Asat by Rubisco (Vcmax) decreases and control by the capacity for RubP regeneration (Jmax) increases (Long et al., 2006). Rubisco is usually fully active and carbamylated at current [CO2] under steady-state high light conditions (Portis, 2003; VON Caemmerer, 2003). As [CO2] increases, carbon fixation increases; there is an increasing demand for ATP (required for RubP regeneration), and control of photosynthesis shifts from being limited by Rubisco to being limited by the capacity for RubP regeneration (Long and Drake 1992; von Caemmerer and Quick 2000). Succinctly, when the supply of photosynthate from chloroplasts exceeds the capacity for export and utilization by sink tissue, the imbalance in supply and demand is sensed in mesophyll cells by a mechanism that possibly involves hexokinase acting as a flux sensor (Ainsworth and Rogers, 2007; Long et al., 2004). It further leads to the decrease of stomatal conductance and the saturation of photosynthesis. However, the CO2 concentration in most areas is not enough to reach the maximum limit of Rubisco, so the increase of CO2 decreases the stomatal conductance while still enhancing the photosynthesis of vegetation.

Generally, the increase of O3 decreased the content of Rubisco enzyme and nitrogen per unit area. It led to the decrease of Vcmax and Jmax and affect the change of stomatal conductance of vegetation (Goumenaki et al., 2010). The decrease in stomatal conductance of plants leads to a decrease in ozone absorption, preventing plants from being further affected by ozone. recently, some studies have shown that mesophyll conductance may be more significant than stomatal conductance. Ma (2022) et al., based on fumigation experiments, found that ozone significantly reduced the mesophyll conductance of four woody plants, but did not significantly reduce the stomatal conductance of all species. Therefore, the decrease of mesophyll conductance of ozone-controlled plants may be the main reason for the decrease of photosynthesis. However, the reciprocal mesophyll conductance (gm) of CO2 resistance during its propagation from cellular interstitium to photosynthetic carboxylation site is similar to stomatal conductance (Flexas et al.,2008; Flexas et al.,2012). We believe that ozone reduces mesophyll conductance while reducing stomatal conductance, thus reducing the propagation resistance of CO2 in cells. Though, this explanation lacks more solid physiological evidence, it gives us a very important implication that ignoring the Vcmax and Jmax estimated by gm will accumulate the negative effect of O3 on gm on its effect on photosynthetic biochemical capacity (Ma et al.,2022). In addition, gm is a key parameter of photosynthesis models, and its inclusion in vegetation models can significantly improve the simulation accuracy of carbon and water fluxes (Knauer et al., 2019).

A number of studies have indicated that using well-validated ecophysiological mechanism models to assess surface-atmosphere feedbacks is a better and more relevant approach (Anav et al., 2012; Anav et al., 2018; Tao et al., 2017), although it is challenging and requires further development. In addition, we also emphasize the careful consideration of model coupling using environmental factor feedback. For example, Oliver et al. (2018) showed that although CO2 fertilization effects are ubiquitous in global terrestrial ecosystems, the protective effect of CO2 on O3 damage to all species at all growth stages cannot be assumed under a wide range of environmental conditions. In addition, in our study, the leaf area index, as the input data, greatly affects the carbon allocation of vegetation, which leads to the possible underestimation of the model when responding to climate change. To further improve the modeling system, we need to continue to refine the species parameter base of the model and refine the physiological process of surface-atmosphere feedback by collecting more observational experiments.

5. Conclusion

In this study, climate change, CO2 and O3 are integrated into the ecological process model. The single and combined effects of [CO2] and [O3] on the GPP of woodland ecosystems in China under historical climate change scenarios were investigated by model setting. Our results suggest that CO2 fertilization is widespread and increasing in woodland ecosystems in China. While ozone damage may currently outweigh the gains of carbon dioxide to forest productivity, rising carbon dioxide and climate change are gradually reducing ozone damage to woodland. Particularly in boreal forest areas, where ozone concentrations are low, there has been a significant increase in GPP. However, simply reducing carbon dioxide emissions could still cause a sustained increase in O3 damage. This study demonstrates the superiority of ecological process models for assessing the interactive responses to climate change. The importance of considering multiple factors in simulation research is emphasized. In addition, the comparison of individual and combined models will provide an important basis for national emission reduction strategies as well as O3 regulation and climate adaptation in different regions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

CRediT

Qinyi Wang: Conceptualization, Software, Writing - Original draft preparation; Shaoqiang Wang: Writing - Review and Editing, Supervision, Project administration; Zhenhai Liu: Software, Validation, Data Curation; Shiliang Chen: Validation, Data Curation; Tingyu Li: Validation, Data Curation; Bin Chen: Review and Editing; Yuelin Li: Data Curation; Mei Huang: Writing - Review and Editing, Supervision, Project administration; Leigang Sun: Data Curation.

Acknowledgments

This study used eddy covariance data acquired and shared by ChinaFLUX, AsiaFlux and FLUXNET. The GLOBMAP-V3 LAI datasets and SoilGrids dataset are provided by Yang Liu and Tomislav Hengl. We greatly offer our profound appreciation to all the providers of the freely available data. This research was supported by Science and Technology Planning Project of Hebei Academy of Sciences (25103) and China University of Geosciences Fund (2019004).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Open Research

The BEPS model (site scale) for the coupled ozone module used in this article can be downloaded at the following link. DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.25476388. Meteorological data are collected from ERA5_Land. DOI: 10.24381/cds.e2161bac. LAI dataset products can be downloaded from this link.

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4700264. Due to the confidentiality of some data acquisition, observation flux data need to be obtained through the ChinaFlux website. Here are the links for data retrieval and application.

http://www.chinaflux.org/general/index.aspx?nodeid=25.

References

- Ainsworth, E. A., Long, S. P., 2005. What have we learned from 15 years of free-air CO2 enrichment (FACE)? A meta-analytic review of the responses of photosynthesis, canopy properties and plant production to rising CO2. New Phytologist. 165, 351-372.

- Ainsworth, E. A., Rogers, A., 2007. The response of photosynthesis and stomatal conductance to rising [CO2]: mechanisms and environmental interactions. Plant, Cell & Environment. 30, 258-270. [CrossRef]

- Anav, A., et al., 2011. Impact of tropospheric ozone on the Euro-Mediterranean vegetation. Global Change Biology. 17, 2342-2359. [CrossRef]

- Anav, A., et al., 2012. A comparison of two canopy conductance parameterizations to quantify the interactions between surface ozone and vegetation over Europe. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences. 117, n/a-n/a. [CrossRef]

- Anav, A., et al., 2018. The role of plant phenology in stomatal ozone flux modeling. Global Change Biology. 24, 235-248. [CrossRef]

- Azoulay Shemer, T., et al., 2015. Guard cell photosynthesis is critical for stomatal turgor production, yet does not directly mediateCO2 and induced stomatal closing. The Plant Journal. 83, 567-581. [CrossRef]

- Bell, B., et al., 2021. The ERA5 global reanalysis: Preliminary extension to 1950. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 147, 4186-4227. [CrossRef]

- Bo, Z., et al., 2014. Land cover mapping using time series HJ-1 / CCD data. Science in China: Earth Science English., 1790-1799.

- Chen, B., et al., 2007. Remote sensing-based ecosystem–atmosphere simulation scheme (EASS)—Model formulation and test with multiple-year data. Ecological Modelling. 209, 277-300. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B., et al., 2019. Including soil water stress in process-based ecosystem models by scaling down maximum carboxylation rate using accumulated soil water deficit. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology. 276-277, 107649. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. M., et al., 1999. Daily canopy photosynthesis model through temporal and spatial scaling for remote sensing applications. Ecological modelling. 124, 99-119. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. M., et al., 2012. Effects of foliage clumping on the estimation of global terrestrial gross primary productivity. Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 26, n/a-n/a. [CrossRef]

- Engineer, C. B., et al., 2016. CO2 Sensing and CO2 Regulation of Stomatal Conductance: Advances and Open Questions. Trends in Plant Science. 21, 16-30. [CrossRef]

- Fares, S., et al., 2012. Ozone deposition to an orange orchard: Partitioning between stomatal and non-stomatal sinks. Environmental Pollution. 169, 258-266. [CrossRef]

- Farquhar, G., et al., 1982. On the Relationship Between Carbon Isotope Discrimination and the Intercellular Carbon Dioxide Concentration in Leaves. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology. 13, 281-292. [CrossRef]

- Flexas, J., et al., 2008. Mesophyll conductance to CO2: current knowledge and future prospects. Plant, Cell & Environment. 31, 602-621. [CrossRef]

- Feng, X., et al., 2007. Net primary productivity of China's terrestrial ecosystems from a process model driven by remote sensing. Journal of Environmental Management. 85, 563-573. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z., et al., 2011. Differential responses in two varieties of winter wheat to elevated ozone concentration under fully open-air field conditions. Global Change Biology. 17, 580-591. [CrossRef]

- Flexas, J., et al., 2012. Corrigendum to ‘Mesophyll diffusion conductance to CO2: An unappreciated central player in photosynthesis’ [Plant Sci. 193–194 (2012) 70–84]. Plant Science. 196, 31.

- Fusaro, L., et al., 2017. Functional indicators of response mechanisms to nitrogen deposition, ozone, and their interaction in two Mediterranean tree species. PLOS ONE. 12, e0185836. [CrossRef]

- Goumenaki, E., et al., Eleni Goumenaki, Tahar Taybi, Anne Borland and Jeremy Barnes, 2010. Mechanisms underlying the impacts of ozone on photosynthetic performance Environmental and Experimental Botany 69: 259-266. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 69, 259-266.

- Grulke, N. E., Heath, R. L., 2019. Ozone effects on plants in natural ecosystems. Plant Biology. 22, 12-37. [CrossRef]

- Hao, M., et al., 2019. Crustal movement and strain distribution in East Asia revealed by GPS observations. Scientific Reports. 9. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, F., et al., 2021. Ozone critical levels for (semi-)natural vegetation dominated by perennial grassland species. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 28, 15090-15098. [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H., et al., 2020. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 146, 1999-2049.

- Hu, L., et al., 2021. Spatiotemporal Variation of Vegetation Productivity and Its Feedback to Climate Change in Northeast China over the Last 30 Years. Remote Sensing. 13, 951. [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, P. G., 1976. The interpretation of the variations in leaf water potential and stomatal conductance found in canopies in the field. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. B, Biological Sciences. 273, 593-610. [CrossRef]

- Keenan, T. F., et al., 2013. Increase in forest water-use efficiency as atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations rise. Nature. 499, 324-327. [CrossRef]

- Knauer, J., et al., 2019. Effects of mesophyll conductance on vegetation responses to elevated CO2 concentrations in a land surface model. Global Change Biology. 25, 1820-1838. [CrossRef]

- Launiainen, S., et al., 2022. Does growing atmospheric CO2 explain increasing carbon sink in a boreal coniferous forest? Global Change Biology. 28, 2910-2929.

- Leung, F., et al., 2020. Evidence of Ozone-Induced Visible Foliar Injury in Hong Kong Using Phaseolus Vulgaris as a Bioindicator. Atmosphere. 11, 266. [CrossRef]

- Li, D., et al., 2022. Surface ozone impacts on major crop production in China from 2010 to 2017. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 22, 2625-2638. [CrossRef]

- Li, L., et al., 2022. Growth reduction and alteration of nonstructural carbohydrate (NSC) allocation in a sympodial bamboo (Indocalamus decorus) under atmospheric O3 enrichment. Science of The Total Environment. 826, 154096. [CrossRef]

- Li, P., et al., 2016. Differences in ozone sensitivity among woody species are related to leaf morphology and antioxidant levels. Tree Physiology. 36, 1105-1116. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., et al., 2018. Leaf area index identified as a major source of variability in modeled CO2 fertilization. Biogeosciences. 15, 6909-6925. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., et al., 2012. Retrospective retrieval of long-term consistent global leaf area index (1981-2011) from combined AVHRR and MODIS data. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences. 117, n/a-n/a. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., et al., 2022. Quantifying the contributions of climate change and human activities to vegetation dynamic in China based on multiple indices. Science of The Total Environment. 838, 156553. [CrossRef]

- Long, S.P. and Drake, B.G., 1992. Chapter 4-Photosynthetic CO2 assimilation and rising atmospheric CO2 concentrations. In: N.R. Baker and H. Thomas (N.R. Baker and H. Thomas), Crop Photosynthesis. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 69-103.

- Long, S. P., et al., 2004. RISING ATMOSPHERIC CARBON DIOXIDE: Plants FACE the Future. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 55, 591-628. [CrossRef]

- Long, S. P., et al., Long-Term Responses of Photosynthesis and Stomata to Elevated [CO2] in Managed Systems. In: J. Nösberger, et al., Eds.), Managed Ecosystems and CO2: Case Studies, Processes, and Perspectives. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2006, pp. 253-270.

- Martínez-Sánchez, Á., et al., 2024. Decomposing causality into its synergistic, unique, and redundant components. Nature Communications. 15, 9296. [CrossRef]

- MA, Yanze; et al., 2022. Response of key parameters of leaf photosynthetic models to increased ozone concentration in four common trees. Chinese Journal of Plant Ecology, 2022, 46 (3): 321-329. [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R. J., et al., 2018. Large but decreasing effect of ozone on the European carbon sink. Biogeosciences. 15, 4245-4269. [CrossRef]

- Otu-Larbi, F., et al., 2020. Current and future impacts of drought and ozone stress on Northern Hemisphere forests. Glob Chang Biol. 26, 6218-6234. [CrossRef]

- Porter, J. R., et al., 2014. Food security and food production systems.

- Portis, A. R., 2003. Rubisco activase-Rubisco's catalytic chaperone. Photosynthesis Research. 75, 11-27. [CrossRef]

- Ren, W., et al., 2007. Effects of tropospheric ozone pollution on net primary productivity and carbon storage in terrestrial ecosystems of China. Journal of Geophysical Research. 112. [CrossRef]

- Ren, W., et al., 2007. Influence of ozone pollution and climate variability on net primary productivity and carbon storage in China's grassland ecosystems from 1961 to 2000. Environmental Pollution. 149, 327-335. [CrossRef]

- Ren, W., et al., 2011. Impacts of tropospheric ozone and climate change on net primary productivity and net carbon exchange of China's forest ecosystems. Global Ecology and Biogeography. 20, 391-406. [CrossRef]

- Schimel, D., et al., 2015. Effect of increasing CO2 on the terrestrial carbon cycle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112, 436-441. [CrossRef]

- Seltzer, K. M., et al., 2020. Magnitude, trends, and impacts of ambient long-term ozone exposure in the United States from 2000 to 2015. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 20, 1757-1775. [CrossRef]

- Sitch, S., et al., 2007. Indirect radiative forcing of climate change through ozone effects on the land-carbon sink. Nature. 448, 791-794. [CrossRef]

- Tai, A. P. K., et al., 2014. Threat to future global food security from climate change and ozone air pollution. Nature Climate Change. 4, 817-821. [CrossRef]

- Tai, A. P. K., et al., 2021. Impacts of Surface Ozone Pollution on Global Crop Yields: Comparing Different Ozone Exposure Metrics and Incorporating Co-effects of CO2. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems. 5. [CrossRef]

- Tcherkez, G. G. B., et al., 2006. Despite slow catalysis and confused substrate specificity, all ribulose bisphosphate carboxylases may be nearly perfectly optimized. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, PNAS. 103, 7246-7251. [CrossRef]

- Tao, F., et al., 2017. Effects of climate change, CO2 and O3 on wheat productivity in Eastern China, singly and in combination. Atmospheric Environment. 153, 182-193. [CrossRef]

- Tian, H., et al., 2011. China's terrestrial carbon balance: Contributions from multiple global change factors. Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 25, n/a-n/a. [CrossRef]

- Ueyama, M., et al., 2020. Inferring CO2 fertilization effect based on global monitoring land-atmosphere exchange with a theoretical model. Environmental research letters. 15. [CrossRef]

- Von Caemmerer, S., 2003. C4 photosynthesis in a single C3 cell is theoretically inefficient but may ameliorate internal CO2 diffusion limitations of C3 leaves. Plant, Cell & Environment. 26, 1191-1197.

- von Caemmerer, S., et al., 2000. Rubisco, physiology in vivo. In Photosynthesis: Physiology and Metabolism (edseds R.C. Leegood, T.D. Sharkey & S. von Caemmerer), Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.pp. 85–113.

- Wang, Qinyi., et al., 2023. Evaluation of the impacts of ozone on the vegetation productivity of woodland and grassland ecosystems in China. Ecological Modelling. 483, 110426.

- Wedow, J. M., et al., 2021. Plant biochemistry influences tropospheric ozone formation, destruction, deposition, and response. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 46, 992-1002. [CrossRef]

- Xie, S., et al., 2020. Contributions of climate change, elevated atmospheric CO2 and human activities to ET and GPP trends in the Three-North Region of China. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology. 295, 108183. [CrossRef]

- Xuejuan, C., et al., 2017. Contributions of climate change and human activities to ET and GPP trends over North China Plain from 2000 to 2014. Chinese Journal of Geography., 680.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).