Submitted:

19 June 2025

Posted:

20 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

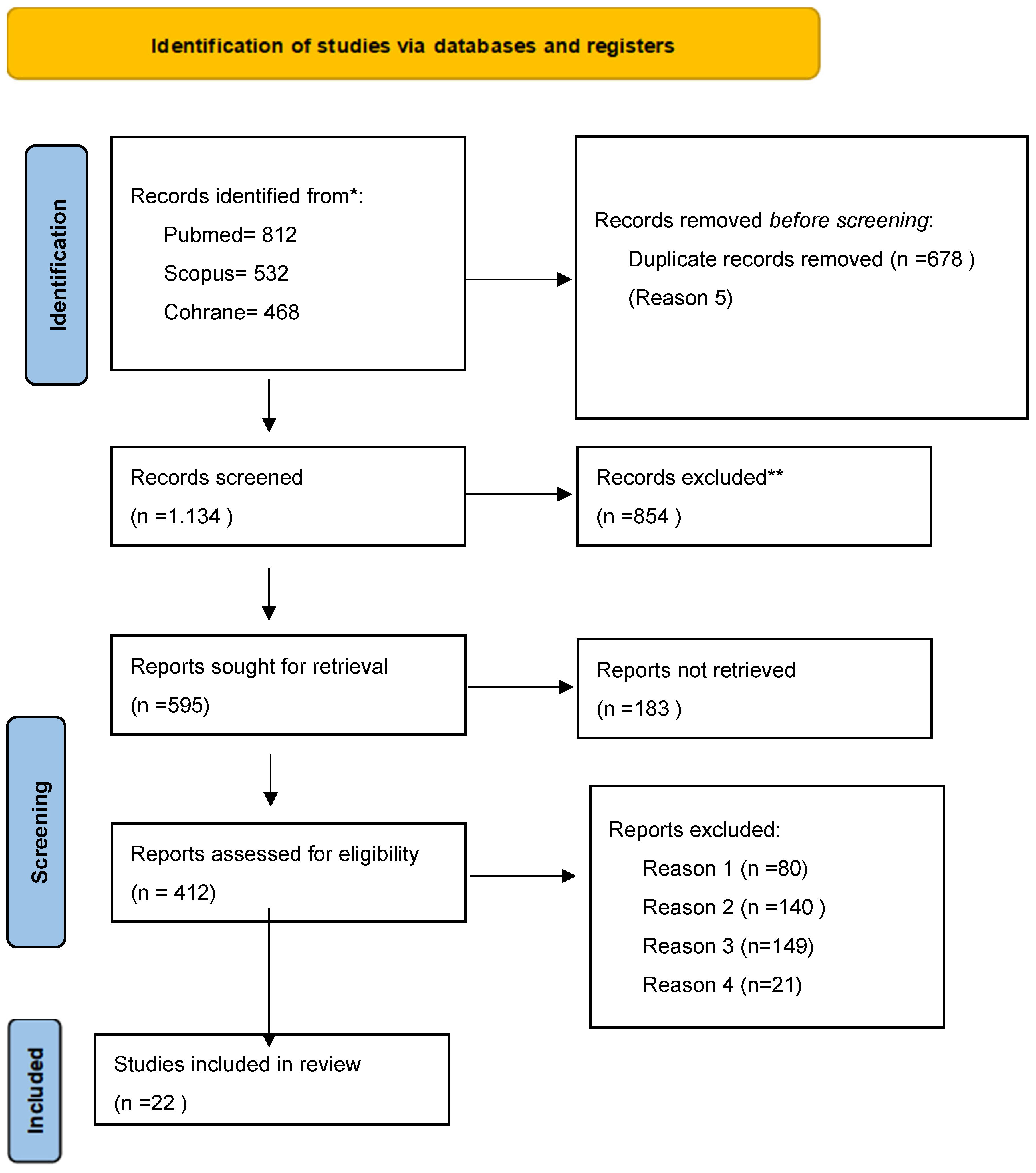

2. Materials and Methods

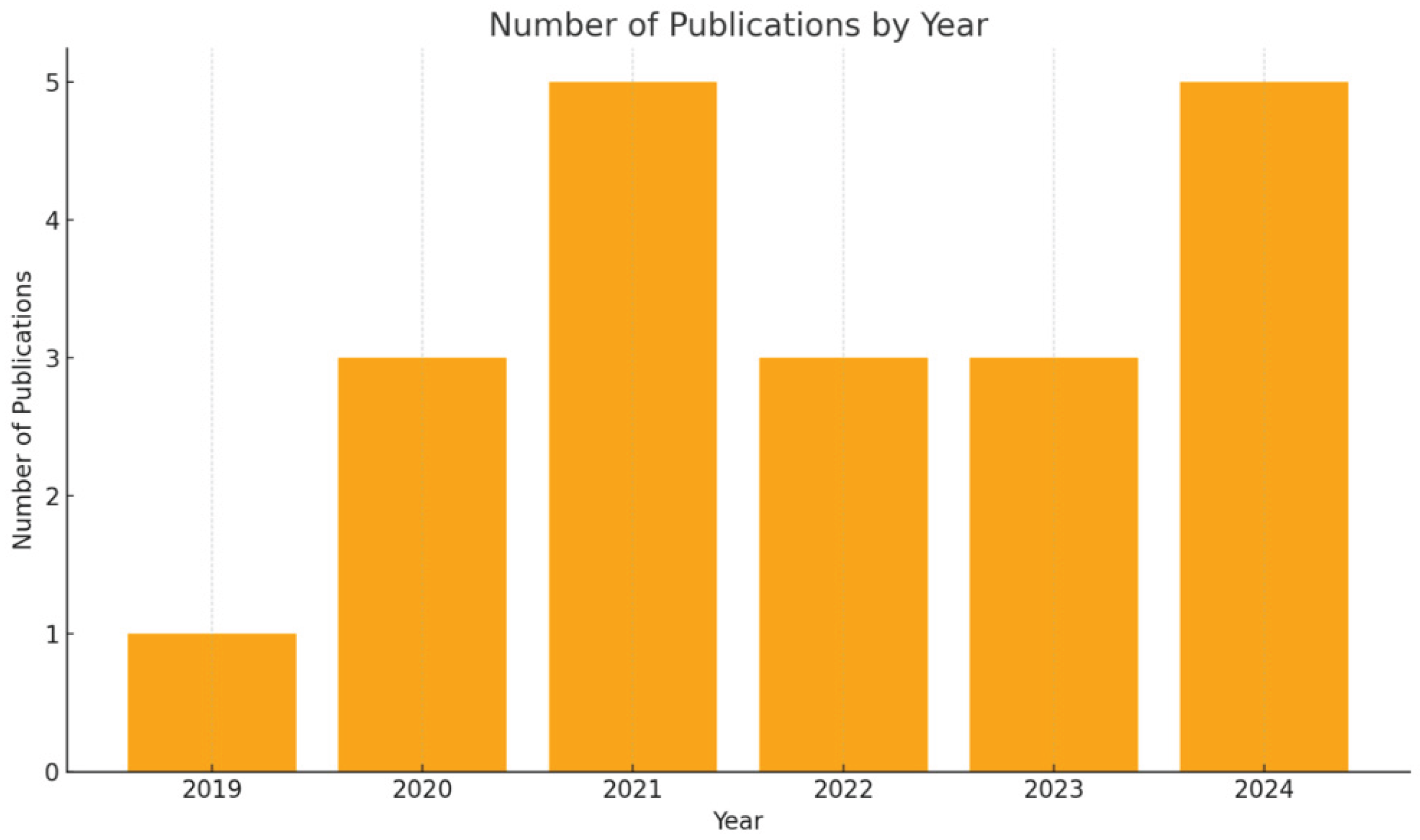

3. Results

Summary of Included Studies

Type of Study and Study Design

Population and Sample Size

Data Collection Methods

Statistical Methodology, Analyses and Recommendations

Limitations Reported In the Reviewed Studies

Comparative and Cross-Cultural Analysis

Overall Implications

4. Discussion

Nutrition Policy, Consumer Practices, and Sustainability in Dietary Choices

Health-Promoting and Sustainable Dietary Patterns

Implications for Dentists' Health and Practice

Psychological Impact of Poor Dietary Habits on Dentists

Shift Work and Its Impact on Dentists' Eating Habits

Interventions to Improve Dietary Habits in Dentists

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

Future Research Directions

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Antoniadou, M. Estimation of Factors Affecting Burnout in Greek Dentists before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 108. [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M.; Mangoulia, P.; Myrianthefs, P. Quality of Life and Wellbeing Parameters of Academic Dental and Nursing Personnel vs. Quality of Services. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2792. [CrossRef]

- Melnyk BM, Kelly SA, Stephens J, Dhakal K, McGovern C, Tucker S, et al. Interventions to improve mental health, well-being, physical health, and lifestyle behaviors in physicians and nurses: A systematic review. Am J Health Promot. 2020;34(8):929–41.

- Negucioiu, M.; Buduru, S.; Ghiz, S.; Kui, A.; Șoicu, S.; Buduru, R.; Sava, S. Prevalence and Management of Burnout Among Dental Professionals Before, During, and After the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2366. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty T, Subbiah GK, Damade Y. Psychological distress during COVID-19 lockdown among dental students and practitioners in India: A cross-sectional survey. Eur J Dent. 2020;14(Suppl 1):S70–8.

- Antoniadou, M. Quality of Life and Satisfaction from Career and Work–Life Integration of Greek Dentists before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9865. [CrossRef]

- Wirth MD, Meyer J, Jessup A, Dawson RM. Barriers and facilitators of diet, physical activity levels, and sleep among nursing undergraduates and early-career nurses: A qualitative descriptive study. Am J Health Promot. 2023;37(6):821–9.

- Kris-Etherton PM, Petersen KS, Hibbeln JR, Hurley D, Kolick V, Peoples S, et al. Nutrition and behavioral health disorders: Depression and anxiety. Nutr Rev. 2021;79(3):247–60.

- Canuto R, Garcez A, Spritzer PM, Olinto MTA. Associations of perceived stress and salivary cortisol with the snack and fast-food dietary pattern in women shift workers. Stress. 2021;24(6):763–71.

- Sert E, Kendirkiran G. Effects of emotional eating behaviour and burnout levels of nurses on job performance: A cross-sectional descriptive study. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2024.

- Antoniadou, M.; Manta, G.; Kanellopoulou, A.; Kalogerakou, T.; Satta, A.; Mangoulia, P. Managing Stress and Somatization Symptoms Among Students in Demanding Academic Healthcare Environments. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2522. [CrossRef]

- Kalogerakou T, Antoniadou M. The role of dietary antioxidants, food supplements and functional foods for energy enhancement in healthcare professionals. Antioxidants. 2024;13(12):1508.

- Mentzelou M, Papadopoulou SK, Jacovides C, Dakanalis A, Alexatou O, Vorvolakos T, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic increased the risk of eating disorders and emotional eating symptoms: A review of the current clinical evidence. COVID. 2024;4(11):1704–18.

- Yaman GB, Hocaoğlu Ç. Examination of eating and nutritional habits in health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrition. 2022;105:111839.

- Wolska A, Stasiewicz B, Kaźmierczak-Siedlecka K, Ziętek M, Solek-Pastuszka J, Drozd A, et al. Unhealthy food choices among healthcare shift workers: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients. 2022;14(20):4327.

- Ramachandran S, Shayanfar M, Brondani M. Stressors and mental health impacts of COVID-19 in dental students: A scoping review. J Dent Educ. 2022.

- Maragha T, Donnelly L, Schuetz C, von Bergmann H, Brondani M. Students' resilience and mental health in the dental curriculum. Eur J Dent Educ. 2023;27(1):174–80.

- Mangoulia P, Kanellopoulou A, Manta G, Chrysochoou G, Dimitriou E, Kalogerakou T, et al. Exploring the levels of stress, anxiety, depression, resilience, hope, and spiritual well-being among Greek dentistry and nursing students in response to academic responsibilities two years after the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare. 2025;13(1):54.

- Gómez-Polo C, Martín Casado AM, Montero J. Burnout syndrome in dentists: Work-related factors. J Dent. 2022;121:104143.

- Long H, Li Q, Zhong X, Yang L, Liu Y, Pu J, et al. The prevalence of professional burnout among dentists: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Health Psychol. 2023;28(13):1767–82.

- Schliemann D, Woodside JV. The effectiveness of dietary workplace interventions: A systematic review of systematic reviews. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22(5):942–55.

- Rachmah Q, Martiana T, Mulyono M, Paskarini I, Dwiyanti E, Widajati N, et al. The effectiveness of nutrition and health intervention in workplace setting: A systematic review. J Public Health Res. 2021;11(1):2312.

- Crespo-Escobar P, Vázquez-Polo M, van der Hofstadt M, Nuñez C, Montoro-Huguet MA, Churruca I, et al. Knowledge gaps in gluten-free diet awareness among patients and healthcare professionals: A call for enhanced nutritional education. Nutrients. 2024;16(15):2512.

- Hobby J, Parkinson J, Ball L. Exploring health professionals' perceptions of how their own diet influences their self-efficacy in providing nutrition care. Psychol Health. 2024;39(2):252–67.

- Lieffers JR, Vanzan AGT, de Mello JR. Nutrition care practices of dietitians and oral health professionals for oral health conditions: A scoping review. Nutrients. 2021;13(10):3588.

- Tantimahanon A, Sipiyaruk K, Tantipoj C. Determinants of dietary behaviors among dental professionals: Insights across educational levels. BMC Oral Health. 2024;24:724.

- Riznik P, De Leo L, Dolinsek J, Gyimesi J, Klemenak M, Koletzko B, et al. The knowledge about celiac disease among healthcare professionals and patients in Central Europe. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2021;72(4):552–7.

- Akbar Z, Shi Z. Unfavorable Mealtime, Meal Skipping, and Shiftwork Are Associated with Circadian Syndrome in Adults Participating in NHANES 2005-2016. Nutrients. 2024 May 23;16(11):1581. [CrossRef]

- Tosoratto J, Tárraga López PJ, López-González ÁA, Vallejos D, Martínez-Almoyna Rifá E, Ramirez-Manent JI. Association of Shift Work, Sociodemographic Variables and Healthy Habits with Obesity Scales. Life (Basel). 2024 Nov 18;14(11):1503. [CrossRef]

- Sejbuk M, Siebieszuk A, Witkowska AM. The role of gut microbiome in sleep quality and health: Dietary strategies for microbiota support. Nutrients. 2024;16(14):2259.

- Mohd Azmi, N.A.S.; Juliana, N.; Mohd Fahmi Teng, N.I.; Azmani, S.; Das, S.; Effendy, N. Consequences of Circadian Disruption in Shift Workers on Chrononutrition and their Psychosocial Well-Being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2043. [CrossRef]

- Bouillon-Minois JB, Thivel D, Croizier C, Ajebo É, Cambier S, Boudet G, et al. The negative impact of night shifts on diet in emergency healthcare workers. Nutrients. 2022;14(4):829.

- Shiri R, Nikunlaakso R, Laitinen J. Effectiveness of workplace interventions to improve health and well-being of health and social service workers: A narrative review of randomised controlled trials. Healthcare. 2023;11(12):1792.

- Etz RS, Solid CA, Gonzalez MM, Reves SR, Britton E, Green LA, et al. Is primary care ready for a potential new public health emergency in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, now subsided? Fam Pract. 2024;41(5):732–9.

- Chen M, Xu X, Liu Y, Yao Y, Zhang P, Liu J, et al. Association of eating habits with health perception and diseases among Chinese physicians: A cross-sectional study. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1226672.

- Abouelezz NF, Ahmed WSE, Elhussieny DM, Ahmed GS, Zaky MSME. Dietary habits and perceived barriers of healthy eating among healthcare workers in a tertiary hospital in Egypt: A cross-sectional study. QJM. 2024;117(Suppl 2):hcae175.884.

- Panchbhaya A, Baldwin C, Gibson R. Improving the Dietary Intake of Health Care Workers through Workplace Dietary Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv Nutr. 2022 Mar;13(2):595-620. Epub 2023 Feb 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mancin S., Reggiani F., Calatroni M., Morenghi E., Andreoli D., Mazzoleni B.Enhancing clinical nutrition education for healthcare professionals: Engagement through active learning methodologies. Clinical Nutrition Open Science, 2023, 52, 49-57. [CrossRef]

- Breanna Lepre, Helena Trigueiro, Jørgen Torgerstuen Johnsen, Ali Ahsan Khalid, Lauren Ball, Sumantra Ray - Global architecture for the nutrition training of health professionals: a scoping review and blueprint for next steps: BMJ Nutrition, Prevention & Health 2022;5. [CrossRef]

- Prajapati AS, Kulkarni PR, Shah HG, Shah DB, Sodani V, Doshi P. Attitude, practices and experience of dental professionals during COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey from Gujarat, India. Adv Hum Biol. 2021;11(3):266–72. [CrossRef]

- Dhillon CN, Ortenzi F. Potential for Impact of Workforce Nutrition Programmes on Nutrition, Health and Business Outcomes: a Review of the Global Evidence and Future Research Agenda. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(9):5733. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal M, Ospina NS, Kazory A, Joseph I, Zaidi Z, Ataya A, et al. The mismatch of nutrition and lifestyle beliefs and actions among physicians: A wake-up call. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2020;14(3):304–15.

- Valizadeh A, Moassefi M, Nakhostin-Ansari A, Hosseini Asl SH, Saghab Torbati M, Aghajani R, Maleki Ghorbani Z, Faghani S. Abstract screening using the automated tool Rayyan: results of effectiveness in three diagnostic test accuracy systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2022 Jun 2;22(1):160. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Olesińska, W.; Biernatek, M.; Lachowicz-Wiśniewska, S.; Piątek, J. Systematic Review of the Impact of COVID-19 on Healthcare Systems and Society—The Role of Diagnostics and Nutrition in Pandemic Response. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2482. [CrossRef]

- Di Prinzio RR, Dosi A, Arnesano G, Vacca ME, Melcore G, Maimone M, Vinci MR, Camisa V, Santoro A, De Falco F, De Maio F, Dalmasso G, Di Brino E, Pieri V and Zana S (2025) Eectiveness of a Food Education Program for healthcare workers: a pilot study in a Total Worker Health© approach. Front. Public Health 13:1523131.

- Vivarelli S, Fenga C. Workplace health promotion program: An integrated intervention to promote well-being among healthcare workers. Public Health Toxicol. 2024;4(3):12.

- Gilbert A, Eyler A, Cesarone G, Harris J, Hayibor L, Evanoff B. Exploring university and healthcare workers' physical activity, diet, and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. SAGE Open Med. 2023;11:21650799221147814.

- Moro JS, Soares JP, Massignan C, Oliveira LB, Ribeiro DM, Cardoso M, et al. Burnout syndrome among dentists: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2022;22(2):101724.

- Panchbhaya A, Baldwin C, Gibson R. Improving the Dietary Intake of Health Care Workers through Workplace Dietary Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv Nutr. 2022 Mar;13(2):595-620. Epub 2023 Feb 10. [CrossRef]

- Søvold LE, Naslund JA, Kousoulis AA, Saxena S, Qoronfleh MW, Grobler C, et al. Prioritizing the mental health and well-being of healthcare workers: An urgent global public health priority. Front Public Health. 2021;9:679397.

- Mehrotra A, Mehrotra A, Babu AK, Ji P, Mapare SA, Pawar RO. Oral health knowledge, attitude, and practices among healthcare professionals: A questionnaire-based survey. J Pharm Bioall Sci. 2021;13(Suppl 2):S1452–7.

- Özarslan M, Caliskan S. Attitudes and predictive factors of psychological distress and occupational burnout among dentists during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. Curr Psychol. 2021;40(7):3113-3124. Epub 2021 Apr 29. [CrossRef]

- Peixoto KO, de Resende CMBM, de Almeida EO, Almeida-Leite CM, Conti PCR, Barbosa GAS, et al. Association of sleep quality and psychological aspects with reports of bruxism and TMD in Brazilian dentists during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Appl Oral Sci. 2021;29:e20201089.

- Pai S, Patil V, Kamath R, Mahendra M, Singhal DK, Bhat V. Work-life balance amongst dental professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic—A structural equation modelling approach. PLoS One. 2021;16(8):e0256663.

- Hassani B, Amani R, Haghighizadeh MH, Araban M. A priority oriented nutrition education program to improve nutritional and cardiometabolic status in the workplace: A randomized field trial. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2020;15(1).

- Tenelanda-López D, Valdivia-Moral P, Castro-Sánchez M. Eating Habits and Their Relationship to Oral Health. Nutrients. 2020 Aug 27;12(9):2619. [CrossRef]

- Potthoff S, Rasul O, Sniehotta FF, Marques M, Beyer F, Thomson R. The relationship between habit and healthcare professional behaviour in clinical practice: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev. 2019;13(1):73–90.

- Rosmiati R, Haryana NR, Firmansyah H, Fransiari ME. Workplace nutrition interventions: A systematic review of their effectiveness. Media Publikasi Promosi Kesehatan Indonesia. 2025;8(3):151–66.

- Kuswari M, Rimbawan R, Hardinsyah H, Dewi M, Gifari N. Effect of tele-exercise versus combination of tele-exercise with tele-counselling on obese office employee’s weight loss. Arsip Gizi Pangan. 2021;6(2):131–9.

- Raudenská J, Steinerová V, Javůrková A, Urits I, Kaye AD, Viswanath O, et al. Occupational burnout syndrome and post-traumatic stress among healthcare professionals during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2020;34(3):553–60.

- Hashem K, et al. Outcomes of sugar reduction policies, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Bull World Health Organ. 2024;102(6):432–9.

- Topaloglu S. Navigating Nutrition Labeling Choices: Latest News on Nutri-Score and Alternative Systems in Europe. Accessed on 15 June 2025 from https://www.foodchainid.com/resources/navigating-nutrition-labeling-choices-latest-news-on-nutri-score-and-alternative-systems-in-europe/.

- Skretkowicz, Yvette and Perret, Jens Kai, Nutri-Score – A Review of the Literature (February 19, 2024). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4731637 or or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4731637. [CrossRef]

- Song J, Brown MK, Tan M, MacGregor GA, Webster J, Campbell NRC, Trieu K, Ni Mhurchu C, Cobb LK, He FJ. Impact of color-coded and warning nutrition labelling schemes: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2021 Oct 5;18(10):e1003765. [CrossRef]

- Song J, Brown MK, Tan M, et al. Impact of color-coded and warning nutrition labelling schemes: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2021;18:e1003765.

- European Commission. Food 2030 Research and Innovation – Pathways for action 2.0. Brussels: European Commission; 2023.

- Moore Heslin A, McNulty B. Adolescent nutrition and health: characteristics, risk factors and opportunities of an overlooked life stage. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2023;82(2):142-156. [CrossRef]

- EAT–Lancet Commission. Healthy diets from sustainable food systems – Food planet health. Summary report. 2019.

- EU. Questions and Answers on the EU budget: the Common Agricultural Policy and Common Fisheries Policy. Accessed on 15 June 2025 from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_20_985.

- EU. EU4Health programme 2021-2027 – a vision for a healthier European Union. Accessed on 15 June 2025 from https://health.ec.europa.eu/funding/eu4health-programme-2021-2027-vision-healthier-european-union_en.

- Guasch-Ferré M., W. C. Willett WC. The Mediterranean diet and health: a comprehensive overview. J internal med. 2021, 290, 549-566. [CrossRef]

- Zupo R, Castellana F, Piscitelli P, Crupi P, Desantis A, Greco E, Severino FP, Pulimeno M, Guazzini A, Kyriakides TC, Vasiliou V, Trichopoulou A, Soldati L, La Vecchia C, De Gaetano G, Donati MB, Colao A, Miani A, Corbo F, Clodoveo ML. Scientific evidence supporting the newly developed one-health labeling tool "Med-Index": an umbrella systematic review on health benefits of mediterranean diet principles and adherence in a planeterranean perspective. J Transl Med. 2023 Oct 26;21(1):755. [CrossRef]

- Krznarić Ž, Karas I, Ljubas Kelečić D, Vranešić Bender D. The Mediterranean and Nordic Diet: A Review of Differences and Similarities of Two Sustainable, Health-Promoting Dietary Patterns. Front Nutr. 2021 Jun 25;8:683678. [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, C.C.; Pitsillides, M.; Hadjisavvas, A.; Zamba-Papanicolaou, E. Dietary Intake, Mediterranean and Nordic Diet Adherence in Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 336. [CrossRef]

- Woodside J, Young IS, McKinley MC. Culturally adapting the Mediterranean Diet pattern - a way of promoting more 'sustainable' dietary change? Br J Nutr. 2022 Aug 28;128(4):693-703. Epub 2022 Jun 23. [CrossRef]

- Ridoutt BG, Hendrie GA, Noakes M. Dietary Strategies to Reduce Environmental Impact: A Critical Review of the Evidence Base. Adv Nutr. 2017 Nov 15;8(6):933-946. [CrossRef]

- van Dooren C, Loken B, Lang T, Meltzer HM, Halevy S, Neven L, Rubens K, Seves-Santman M, Trolle E. The planet on our plates: approaches to incorporate environmental sustainability within food-based dietary guidelines. Front Nutr. 2024 Jul 5;11:1223814. [CrossRef]

- Mills A, Berlin-Broner Y, Levin L. Improving Patient Well-Being as a Broader Perspective in Dentistry. Int Dent J. 2023 Dec;73(6):785-792. Epub 2023 Jun 19. [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, P., Madanian, S. & Marshall, S. Investigating the link between oral health conditions and systemic diseases: A cross-sectional analysis. Sci Rep 15, 10476 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulou, M.; Antoniadou, M.; Amargianitakis, M.; Gortzi, O.; Androutsos, O.; Varzakas, T. Nutritional Factors Associated with Dental Caries across the Lifespan: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13254. [CrossRef]

- Varzakas T, Antoniadou M. A Holistic Approach for Ethics and Sustainability in the Food Chain: The Gateway to Oral and Systemic Health. Foods. 2024 Apr 17;13(8):1224. [CrossRef]

- Tantimahanon, A., Sipiyaruk, K. & Tantipoj, C. Determinants of dietary behaviors among dental professionals: insights across educational levels. BMC Oral Health 24, 724 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Barranca-Enríquez A, Romo-González T. Your health is in your mouth: A comprehensive view to promote general wellness. Front Oral Health. 2022 Sep 14;3:971223. [CrossRef]

- Tohary IA, Jan AS, Alotaibi MA, Alosaimi TB, Alotaibi AEA, Alshayb AA, et al. The impact of diet and nutrition on oral health: A systematic review. Migr Lett. 2022;19(S5):338–46.

- Antoniadou M, Varzakas T. Breaking the vicious circle of diet, malnutrition and oral health for the independent elderly. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2021;61(19):3233-3255. Epub 2020 Jul 20. [CrossRef]

- Dekker J, Sears SF, Åsenlöf P, Berry K. Psychologically informed health care. Transl Behav Med. 2023 May 13;13(5):289-296. [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M.; Varzakas, T. Diet and Oral Health Coaching Methods and Models for the Independent Elderly. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4021. [CrossRef]

- Kataoka M, Adam LA, Ball LE, Crowley J, McLean RM. Nutrition Education and Practice in University Dental and Oral Health Programmes and Curricula: A Scoping Review. Eur J Dent Educ. 2025 Feb;29(1):64-83. Epub 2024 Oct 29. [CrossRef]

- Rentas González L. Wellness Programs: Strategies for Increasing Employees’ Wellness Programs: Strategies for Increasing Employees’ Productivity and Reducing Health Care Costs. Walden University, 2022. Accessed on 15 June 2025 from chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=15723&context=dissertations.

- Ottaviani JI, Sagi-Kiss V, Schroeter H, Kuhnle GGC. Reliance on self-reports and estimated food composition data in nutrition research introduces significant bias that can only be addressed with biomarkers. Elife. 2024 Jun 19;13:RP92941. [CrossRef]

- Savitz DA, Wellenius GA. Can Cross-Sectional Studies Contribute to Causal Inference? It Depends. Am J Epidemiol. 2023 Apr 6;192(4):514-516. [CrossRef]

- Faber J, Fonseca LM. How sample size influences research outcomes. Dental Press J Orthod. 2014 Jul-Aug;19(4):27-9. [CrossRef]

- Thomas TW, Cankurt M. Influence of Food Environments on Dietary Habits: Insights from a Quasi-Experimental Research. Foods. 2024 Jun 26;13(13):2013. [CrossRef]

- Edú-Valsania S, Laguía A, Moriano JA. Burnout: A Review of Theory and Measurement. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Feb 4;19(3):1780. [CrossRef]

- Dempsey M, Rockwell MS, Wentz LM. The influence of dietary and supplemental omega-3 fatty acids on the omega-3 index: A scoping review. Front Nutr. 2023 Jan 19;10:1072653. [CrossRef]

| Authors | Type of study- | Population | Exposure | Comparators | Statistical significance | Limitations | confounders | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Olesinska et al 2025 [44] | Systematic review – Multi-study analysis | healthcare staff from 10 studies | Workplace nutrition interventions (Mediterranean diet, telehealth, education, counseling) | No intervention, usual routine, or standard programs in original studies | Significant improvements in weight, LDL cholesterol, food literacy, and dietary adherence in most studies | Small sample sizes in some studies, high heterogeneity, limited long-term data, few studies with blinding | Variability in design, participant demographics, and adherence levels | Improvements in BMI, diet quality, cardiometabolic markers, food literacy, and quality of life |

| 2. Mangoulia et al 2025 [18] | Cross-sectional – Single-center (National and Kapodistrian University of Athens) | 271 undergraduate and postgraduate dentistry and nursing students in Greece | Psychological well-being: stress, anxiety, depression, resilience, hope, spiritual well-being | Comparisons between nursing and dentistry students, as well as subgroups based on gender, education level, income | Yes – significant differences found across departments and demographic factors; hierarchical regression showed hope as predictor of resilience | Limited generalizability (single institution); predominance of females; different academic levels per department; low response rate; cross-sectional design | Gender, income, educational level, department | High prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression; dentistry students showed higher stress/anxiety; hope strongly predicted resilience; need for targeted interventions identified |

| 3. Di Prinzio et al. 2025 [45] |

Pilot intervention study (pre-post design) | Healthcare workers in an Italian hospital | Food education program based on Total Worker Health© approach | Baseline (pre-intervention) vs. post-intervention comparisons | Yes, significant improvements in dietary behaviors and knowledge (p < 0.05) | Small sample size (pilot), short follow-up, single-center, lack of control group | Gender, age, baseline health status, occupation | Improved dietary knowledge, increased fruit/vegetable intake, reduced intake of sugary snacks and processed foods, positive changes in self-reported eating habits |

| 4.Vivarelli & Fenga 2024 [46] |

Systematic review (multi-country) | 37 studies on dentists | Prevalence of burnout in dentists via MBI subscales | Not applicable (meta-analysis of observational studies) | Pooled prevalence estimates with 95% CI and heterogeneity (I²); Stata 13.0 used | High heterogeneity (I²>90%), variable study quality, no study met all Joanna Briggs criteria | Study design, population differences | Burnout affected 13% of dentists overall, with high emotional exhaustion in 25%, high depersonalization in 18%, and low personal accomplishment in 32%, making emotional exhaustion the most common dimension. |

| 5.Hobby et al 2024 [24] |

Cross-sectional – Single-center (Australia, qualitative study via interviews) | 22 health professionals (including dietitians) with patient contact | Personal dietary behaviors and self-efficacy in providing nutrition care | No direct comparators; thematic contrasts drawn across narratives | Not applicable (qualitative study); thematic saturation reached | Small sample size; self-selection bias; only Australian participants; qualitative limits to generalizability | Life experiences, social interactions, role modeling | Personal diet and lived experiences influence confidence in providing nutrition care; social support and environment impact self-efficacy |

| 6. Gilbert et al 2023 [47] |

Prospective observational – Single-center (University Hospital ‘G. Martino’, Messina, Italy) | Healthcare workers (20–65 years), with or without night shift work | Night shift work (NSW), occupational stress, sleep quality, diet, physiological biomarkers | HCWs without night shifts | Yes – significant associations (e.g., stress, sleep, diet, biomarkers; p<0.05) | Self-report bias, confounding variables (lifestyle), resource-intensive protocol, only one center | Age, sex, smoking, comorbidities, work conditions | Improved well-being, dietary habits, stress, and sleep patterns; physiological biomarkers monitored; 12-month follow-up planned |

| 7.Shiri et al 2023 [33] | Narrative Review of 108 RCTs – Multi-country | Health and social service workers (various roles and countries) | Workplace interventions (mindfulness, ergonomics, coaching, exercise, nutrition, scheduling, resilience) | No intervention or alternative workplace programs | Yes – modest but statistically significant effects across multiple RCTs | Review limited to PubMed; no quality appraisal of studies; short follow-up; clustering effects not always accounted for; small samples in some RCTs | Various (e.g., age, gender, occupation, baseline stress levels) | Modest improvements in burnout, job satisfaction, work ability, well-being; limited effect on occupational injuries; barriers to participation include workload, lack of support, off-hours scheduling |

| 8.Chen et al 2023 [35] | Cross-sectional – Multi-center (Mainland China, 31 regions) | In-service physicians working in Chinese hospitals (N=9,196) | Unhealthy eating habits (e.g., eating too fast, irregular meals, frequent out-of-home meals) | Comparisons made across groups with and without specific eating habits | Significant associations between unhealthy eating habits and suboptimal health/disease (p<0.05) | Self-report bias, gender imbalance (83.3% women), online survey format, possible information bias | Age, sex, working time, sleep quality, exercise, sedentary time, smoking, alcohol consumption | Unhealthy eating habits significantly associated with subhealth and metabolic/micronutrient-related diseases |

| 9.Mancin et al. 2023 [38] |

Educational intervention study (pre-post design, single center) | Healthcare professionals (physicians, nurses, dietitians) in Italy | Active learning–based clinical nutrition education program (interactive workshops, case-based learning) | Baseline (pre-intervention) vs. post-intervention comparisons | Yes — significant improvement in nutrition knowledge scores and self-reported confidence (p < 0.001) | Small sample size, single center, no long-term follow-up, no control group | Baseline knowledge, profession (nurse/doctor/dietitian), prior training | Improved nutrition knowledge, higher confidence in delivering nutrition advice, greater engagement in nutrition-related clinical practice |

| 10. Moro et al 2022 [48] |

Single-center, randomized controlled field trial | 104 male petrochemical workers | Priority-oriented nutrition education program based on Theory of Planned Behavior | Control group received no intervention | Significant improvements in knowledge, FBS, Hcy (all p<0.001), and BMI (p<0.05). | Short intervention duration (3 months), only male participants, possible recall bias via FFQ, no family evaluation | Smoking, alcohol use, medication use excluded; groups balanced on demographics | Improved nutritional knowledge, dietary behavior, BMI, FBS, and homocysteine levels in the intervention group compared to control group; no significant change in hs-CRP |

| 11.Yaman 2022 [14] | Single-center (online nationwide sample via snowball technique) | 405 healthcare workers in Turkey (aged 19–67) | Perceived stress, emotional eating, and changes in nutritional habits during COVID-19 | Participants with vs. without changes in eating habits | Statistical significance found (e.g., P < 0.001 for stress and dietary changes) | Self-report bias, cross-sectional design, no causality, online sampling bias | Psychiatric history, COVID experience, socioeconomic concerns | 58% changed eating habits, 51% gained weight, significant associations with stress and emotional eating |

| 12. Panchbhaya et al, 2022 [49] | Systematic Review & Meta-analysis | Healthcare workers (various professions) from 26 studies | Workplace dietary interventions (education, environment, behavior change) | No intervention or usual care | Yes, significant improvements in fruit & vegetable intake (+0.49 servings/day), small but significant reduction in energy intake and body weight | Heterogeneity in intervention types, duration, and outcomes; publication bias possible; limited long-term follow-up in primary studies | Variability in study design, population characteristics, workplace settings | Increased fruit/vegetable intake, reduced energy intake and body weight, improved overall diet quality |

| 13.Rachmah et al 2021 [22] | Systematic review of 11 intervention studies from multiple countries | Workers aged 19–64 in various settings (industrial, manufacturing, garment, etc, healthcare sector.) | Nutrition and health interventions: education, behavioral change, physical activity, meal/supplement interventions, or combinations | Mostly RCTs or controlled trials; 2 studies without control groups | Most studies reported significant improvements in BMI, blood markers, self-efficacy, knowledge, diet, and behaviors (e.g., more fruit/veg, less alcohol/fat). | Heterogeneity in methods and duration, 2 studies lacked control groups, no risk of bias assessment, English-only studies included | Population/worksite heterogeneity; differences in baseline characteristics and implementation | Improved BMI, biochemical indices (e.g., cholesterol, fasting blood sugar), nutrition knowledge, physical activity, reduced risky behavior, increased fruit/vegetable intake |

| 14.Sovold et al 2021 [50] | Systematic Review – Multi-source, not center-based | General population; focus on public health, diagnostic, and nutrition data | Diagnostic, nutritional deficiencies (Vitamin D, C, E, zinc, selenium), psychosocial impact | Not applicable (multiple studies compared) | Significance varies per included study (some RCTs, some observational); mixed results | Heterogeneity in study designs, inconsistent RCT outcomes, lack of long-term data, many observational designs, regional bias (many Polish studies) | Potential variability across populations and designs included in review | Combined assessment of diagnostics, immune-nutritional status, mental health effects, and pandemic preparedness strategies. |

| 15. Mehrotra et al 2021 [51] | Single-center (Riobamba, Ecuador) | 380 students in healthcare | Eating habits (fruits, vegetables, dairy, snacks, etc.) | Frequency of consumption | Significant association between DMFT and fruit (p=0.049), vegetables (p=0.028) | Single age group, geographic limitation, outdated national data | None adjusted statistically (e.g., brushing habits, socio-economic status) | DMFT index; associations with eating habits |

| 16. Kris-Etherton et al 2021 [8] | Narrative Review – Multi-study based | Global population, all ages | Dietary patterns, specific nutrients (e.g., omega-3s, B-vitamins, zinc, magnesium) | No direct comparator; studies compared various diets/nutrients with behavioral health outcomes | Statistically significant in many included studies; RCTs show benefit of Mediterranean diet | Narrative nature, no meta-analysis; possible residual confounding and reverse causation | Nutritional status, comorbidities, lifestyle factors, socioeconomic status | Improved mood, reduced depression and anxiety with healthy diets; recommendation for dietary guidelines inclusion |

| 17. Özarslan & Caliskan 2021 [52] | Single center | 473 HCWs (doctors, nurses, pharmacists, technicians, interns) | Oral health knowledge, attitude, and practices (questionnaire-based survey) | Differences among HCW groups, gender, education level | Yes (p < 0.05 in multiple comparisons) | Cross-sectional design, limited sample size, self-reporting bias | Gender, profession, education level | Knowledge scores, attitudes (e.g., dental visit frequency), hygiene practices |

| 18. Peixoto et al 2021 [53] | Multicenter, Cross-sectional | 706 dentists in Turkey (FP & FN) | Working in filiation service vs not during COVID-19 | Dentists not involved in filiation (FN group) | Yes (p<0.05 for many variables) | Internet-based survey, self-reported data, single timepoint, possible selection bias | Confounders: age, gender, academic degree; Outcomes: MBI scores, stress, burnout | Habits etc |

| 19. Pai et al 2021 [54] | Single-center, cross-sectional | 641 Brazilian dentists (G1: quarantine, G2: outpatient care, G3: frontline) | COVID-19 pandemic-related psychosocial factors, sleep quality, TMD and bruxism symptoms | Groups based on work status during the pandemic (quarantine, outpatient, frontline) | Yes (p<0.016 for Bonferroni adjusted; p<0.001 for regressions) | Small sample of frontline dentists, self-reported data, cross-sectional design | Working status, pandemic concerns, psychological symptoms | Significant correlation between sleep and depression, stress, anxiety; poor sleep is associated with TMD and bruxism |

| 20. Hassani et al 2020 [55] | Single-center, cross-sectional | 180 dentists across India | COVID-19 lockdown's effect on work-life balance | Gender, relationship status, workplace factors | SEM showed significant associations (e.g., R² = 0.627; p-values < 0.05) | Self-report bias, low response rate (37.5%), limited geographical representation | Non-inclusion of dentists from all states; self-reporting; limited stress scale use | Work-life balance affected by mental/physical health, relationships, workplace; more imbalance in females |

| 21. Tenelanda-Lopez et al 2020 [56] |

Observational – Single-center (Washington University) | 1,994 employees (university & medical center), with ≥2 responses across 3 survey waves | Self-reported physical activity, diet, and mental well-being during COVID-19 | Clinical vs. nonclinical roles; working from home vs. onsite | Yes – maintained/increased PA and diet significantly linked to better well-being outcomes (p<0.05); multivariate regressions used | Self-reported data; limited generalizability; no baseline pre-pandemic data; recall and perception bias | Age, race, gender, income, ethnicity, clinical role | Participants maintaining or improving health behaviors had lower odds of moderate/severe depression, anxiety, and stress; onsite clinical workers reported worse well-being |

| 22. Schliemann & Woodside 2019 [21] | Systematic review of systematic reviews (multi-study, international) | Adult employees across healthcare sectors; general and “at risk” populations in workplace settings | Dietary workplace interventions (education, environmental changes, multicomponent programs) | Usual care, no intervention, or non-diet-focused interventions | Small but positive effects: improved FV intake (+0.2–0.7 portions), reduced fat intake, weight loss (−4.4 to −1.0 kg), HDL increase (+0.06 mmol/L), cholesterol reduction | High heterogeneity, self-reporting bias, lack of long-term data, limited economic outcome reporting, generalizability concerns | Inconsistent population/workplace reporting; unclear effect of dietary component in multicomponent interventions | Improvements in FV and fat intake, BMI, cholesterol; mixed/limited results on productivity, absenteeism, and economic outcomes |

| Country / Region | Freq. (n) | Percent (%) | Cumulative (%) | Sector | Freq. (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | 3 | 13.6% | 13.6% | Dental / Dentists | 6 | 27.3% |

| Greece | 1 | 4.5% | 18.1% | Physicians | 2 | 9.1% |

| Turkey | 3 | 13.6% | 31.7% | Healthcare workers (mixed) | 7 | 31.8% |

| China | 1 | 4.5% | 36.2% | Nurses | 1 | 4.5% |

| India | 1 | 4.5% | 40.7% | Public health / community health | 1 | 4.5% |

| Ecuador | 1 | 4.5% | 45.2% | Students (healthcare) | 1 | 4.5% |

| Brazil | 1 | 4.5% | 49.7% | Petrochemical workers (industrial) | 1 | 4.5% |

| USA | 1 | 4.5% | 54.2% | Academic medical staff | 1 | 4.5% |

| Australia | 1 | 4.5% | 58.7% | Dietitians & healthcare professionals | 1 | 4.5% |

| Poland | 1 | 4.5% | 63.2% | Public health | 1 | 4.5% |

| UK | 1 | 4.5% | 67.7% | Mixed HCWs | 1 | 4.5% |

| Multi-country (Europe, Global) | 6 | 27.3% | 95% | Multi-sector (systematic reviews) | 6 | 27.3% |

| Finland | 1 | 4.5% | 100% | Multi-professional (health sector) | 1 | 4.5% |

| Total | 22 | 100% | 100% | Total | 22 | 100% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).