Submitted:

18 June 2025

Posted:

19 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

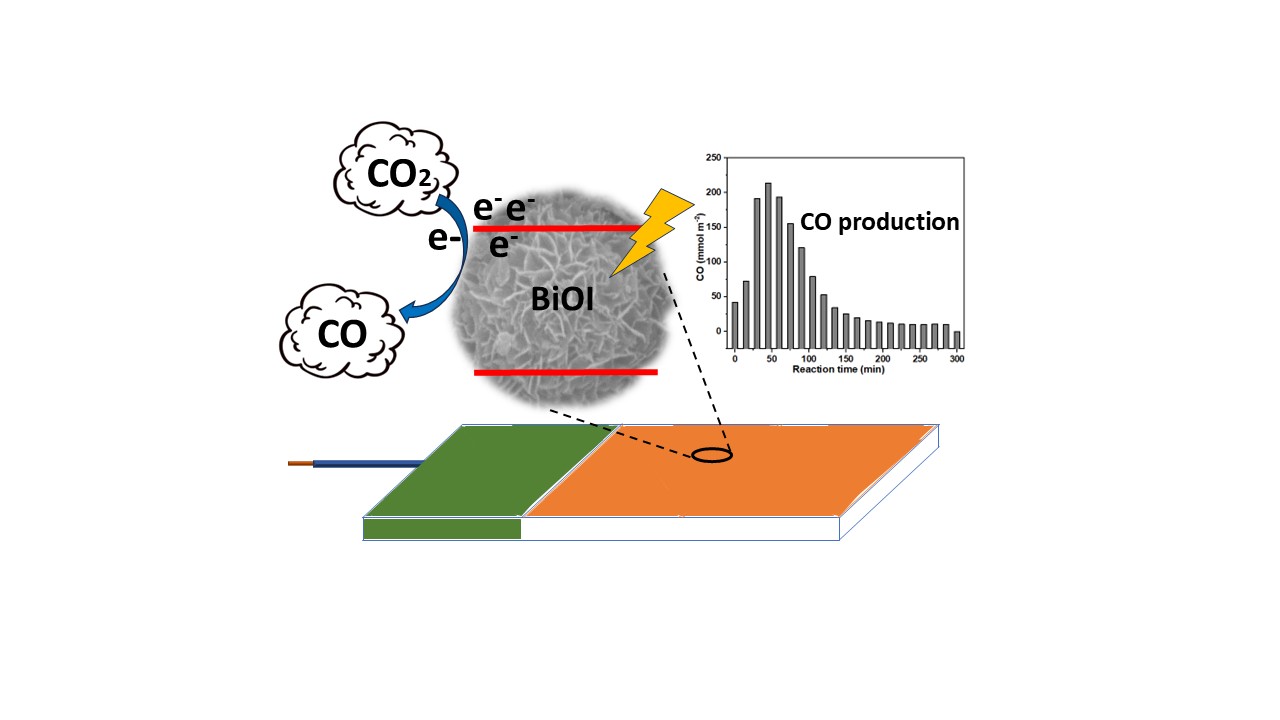

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of Bismuth Oxyiodide

2.2. Preparation of the Electrodes with a Conductive Support

2.3. Preparation of the Electrodes with a Non-Conductive Support

2.4. Instrumentation

3. Results and Discussion

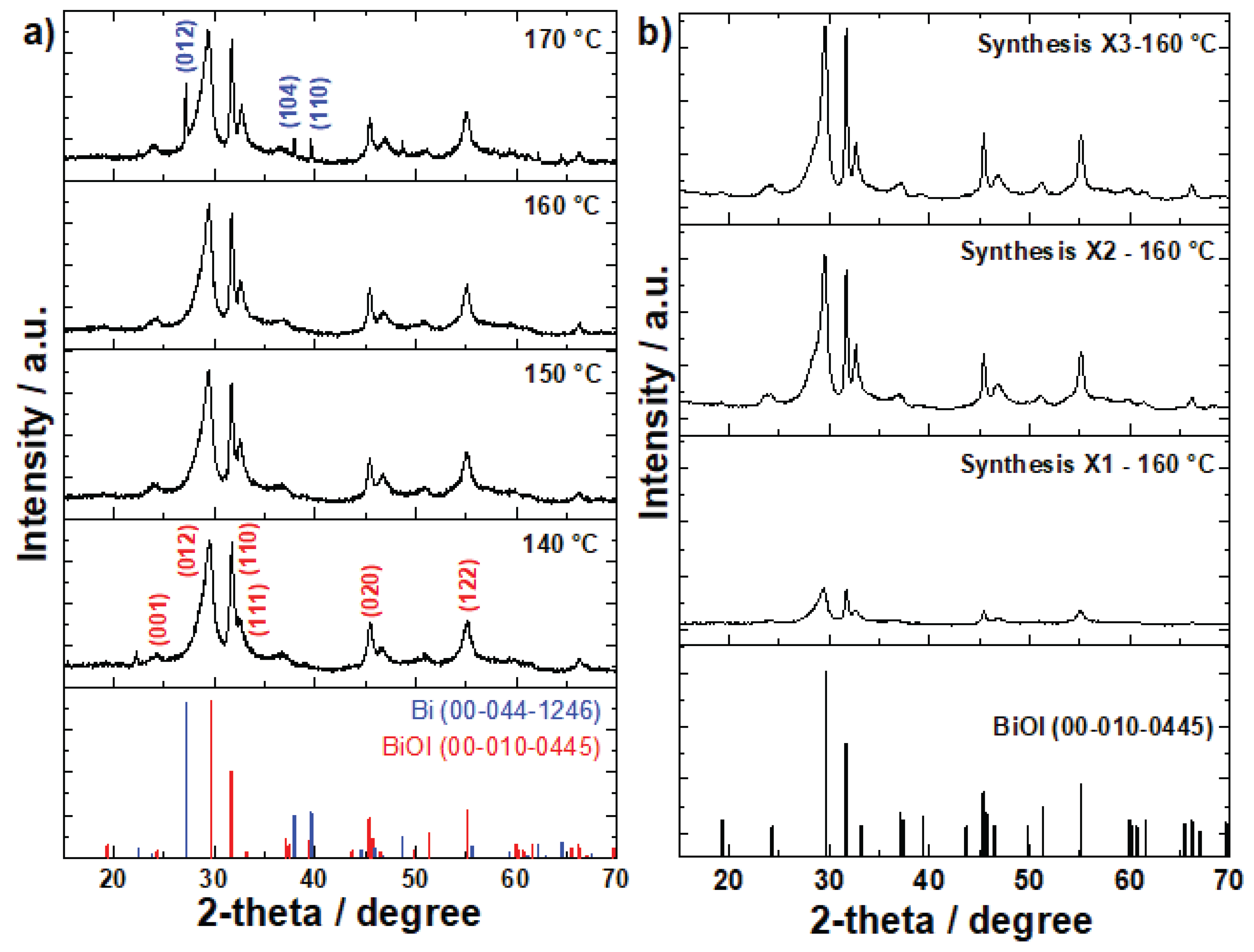

3.1. X-ray Diffraction Analysis

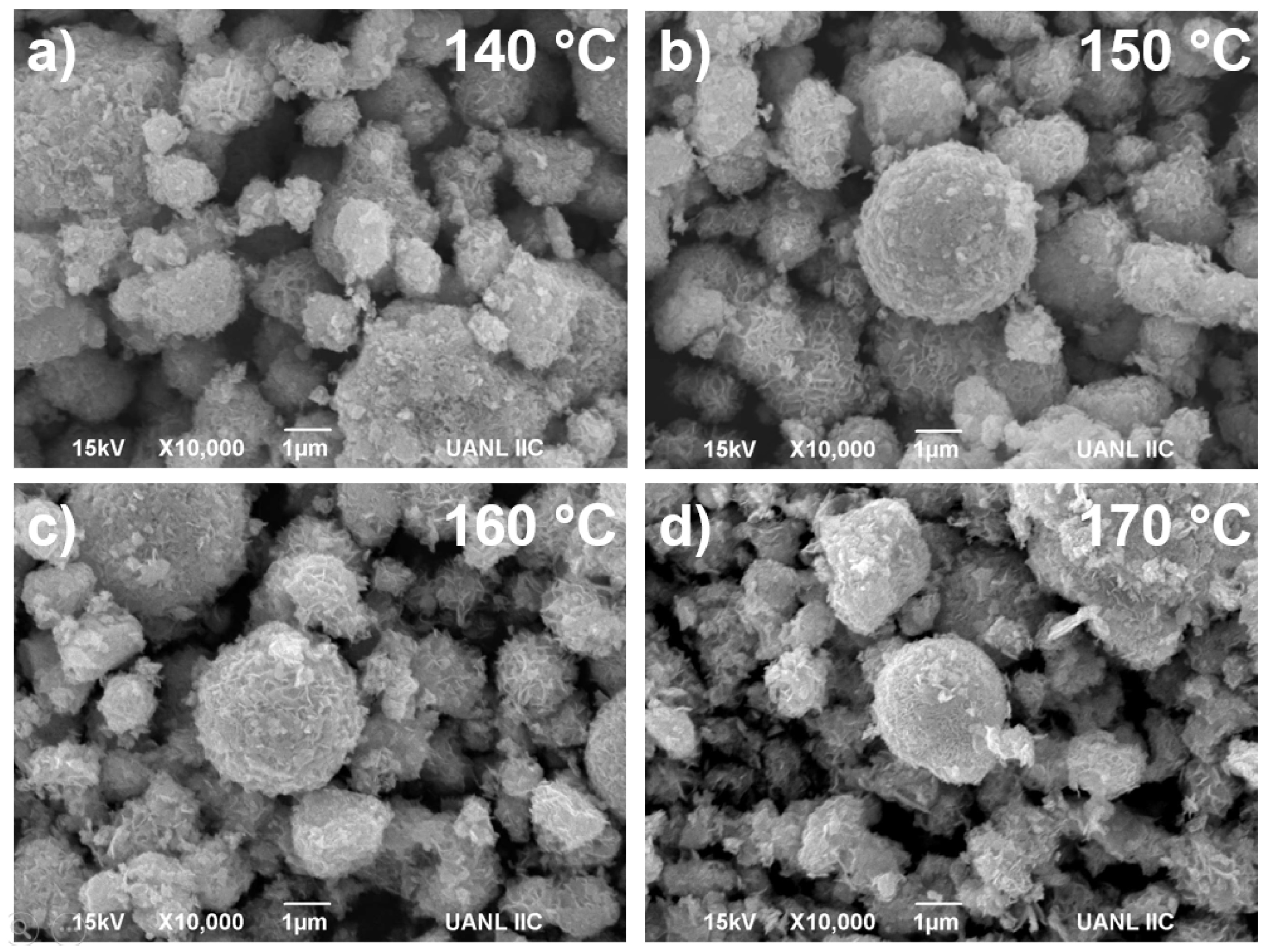

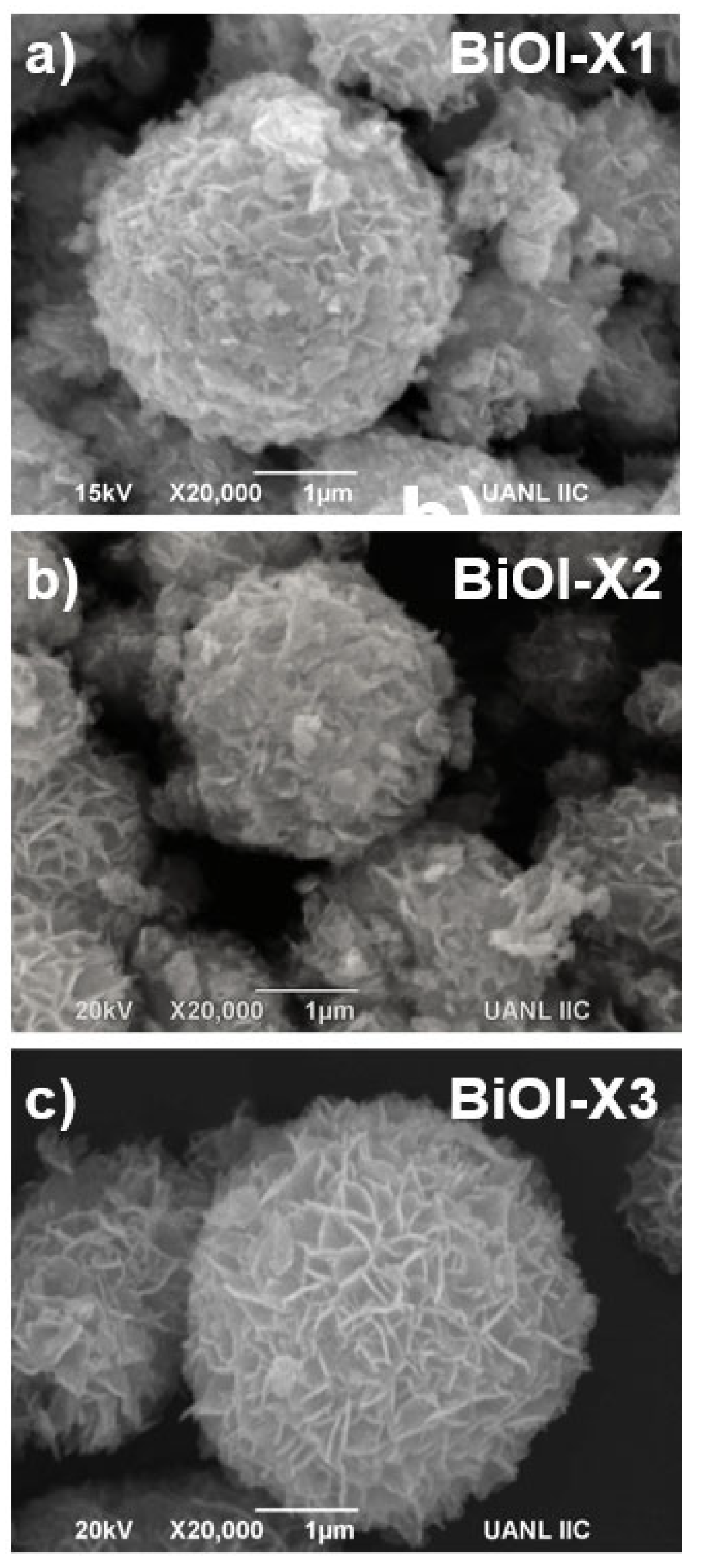

3.2. Microscopy Characterization

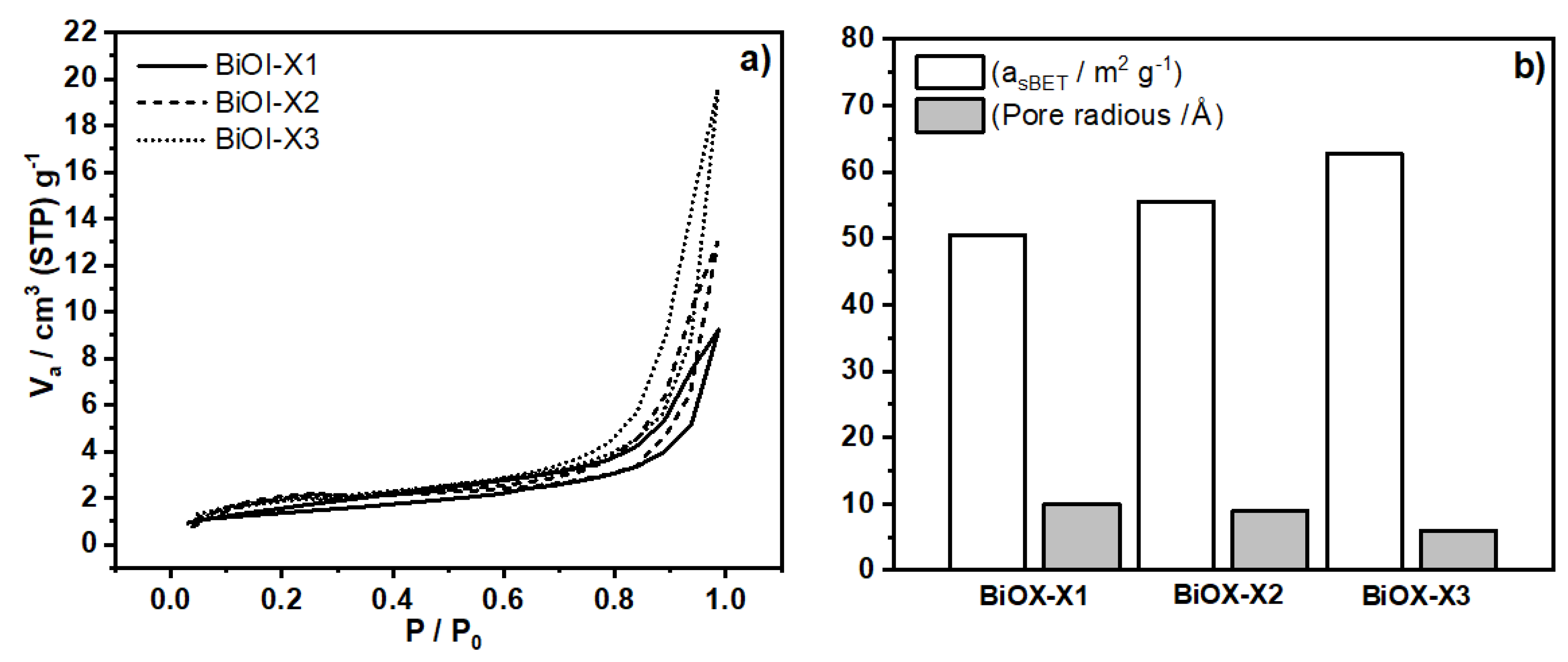

3.3. BET Area (Asbet) and Pore Radius Estimations

3.4. Electrochemical Characterization

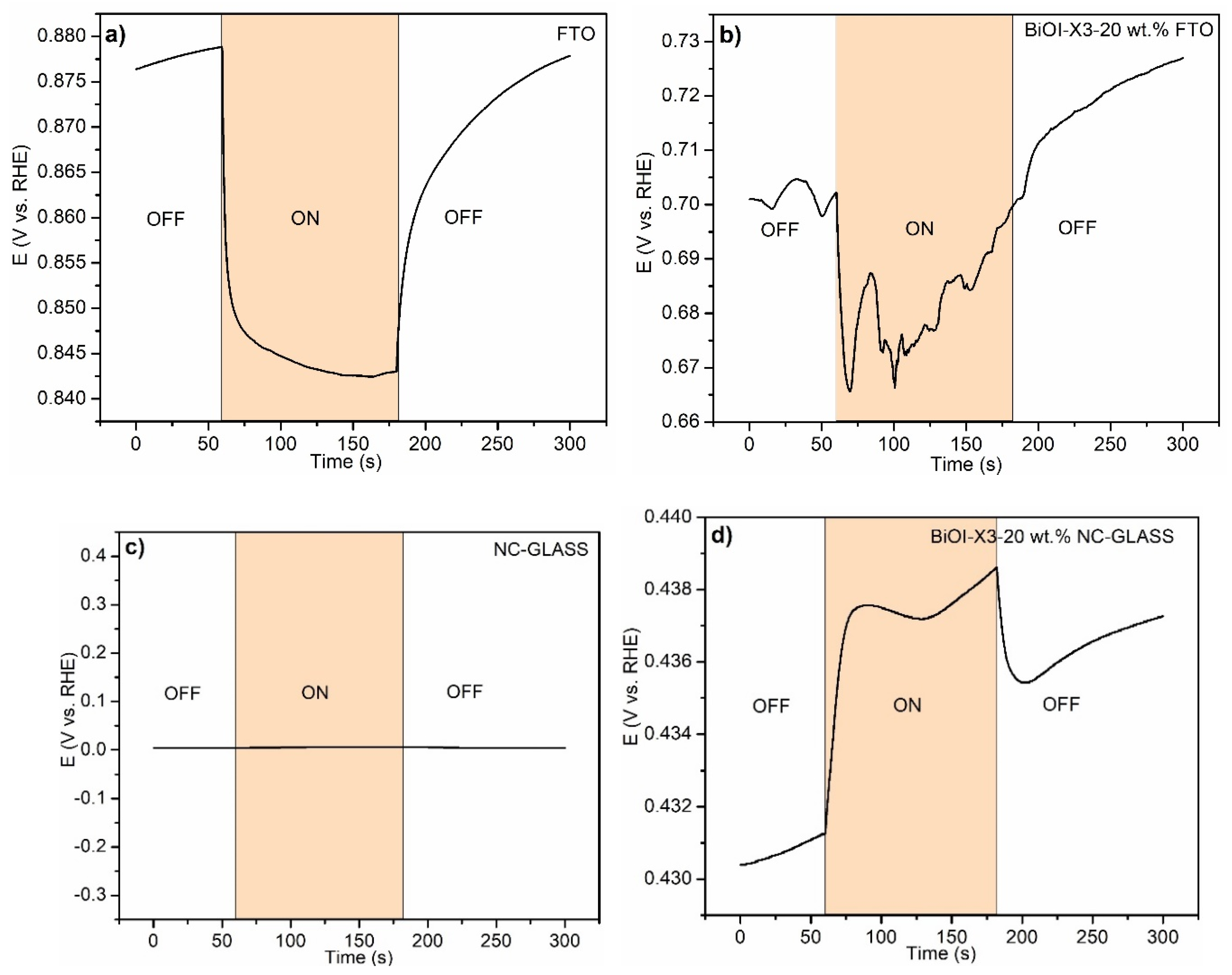

3.4.1. Open Circuit Potential Transients

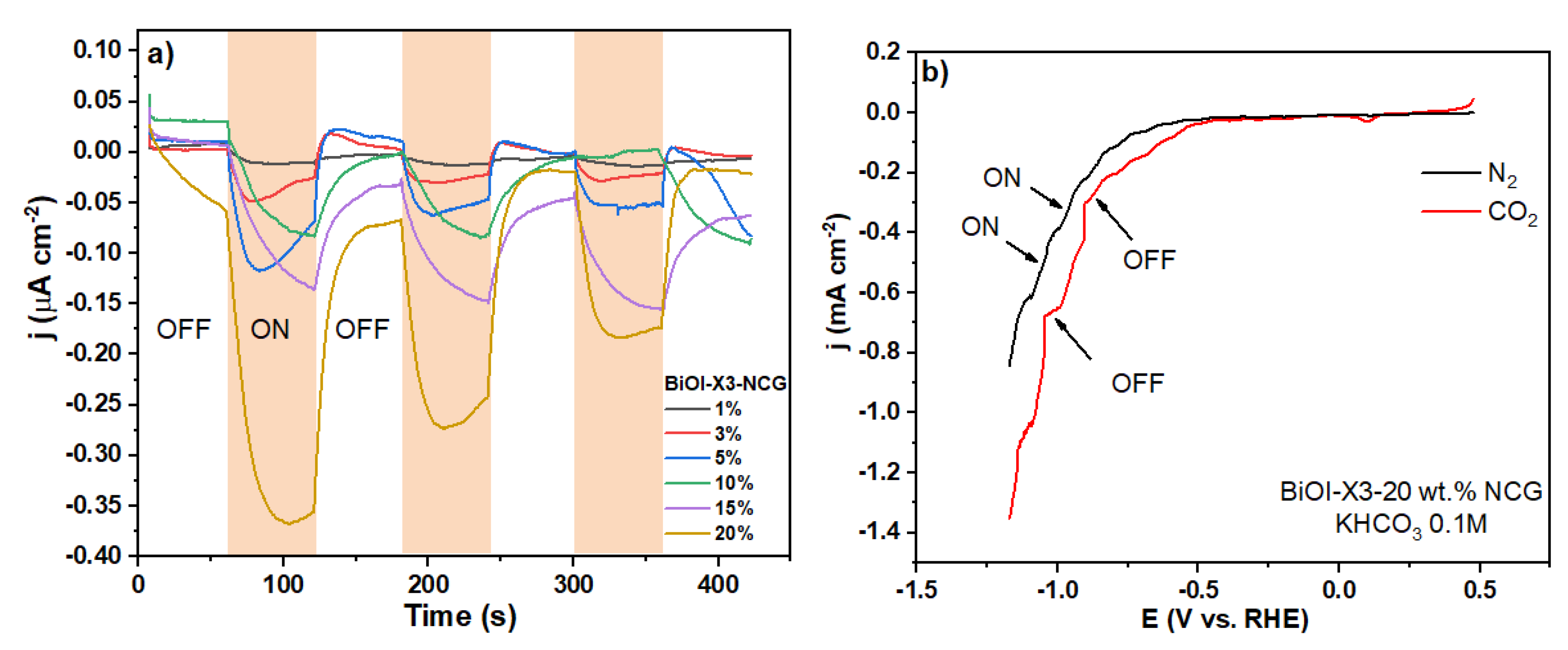

3.4.2. Photo(Electro)Chemical Response

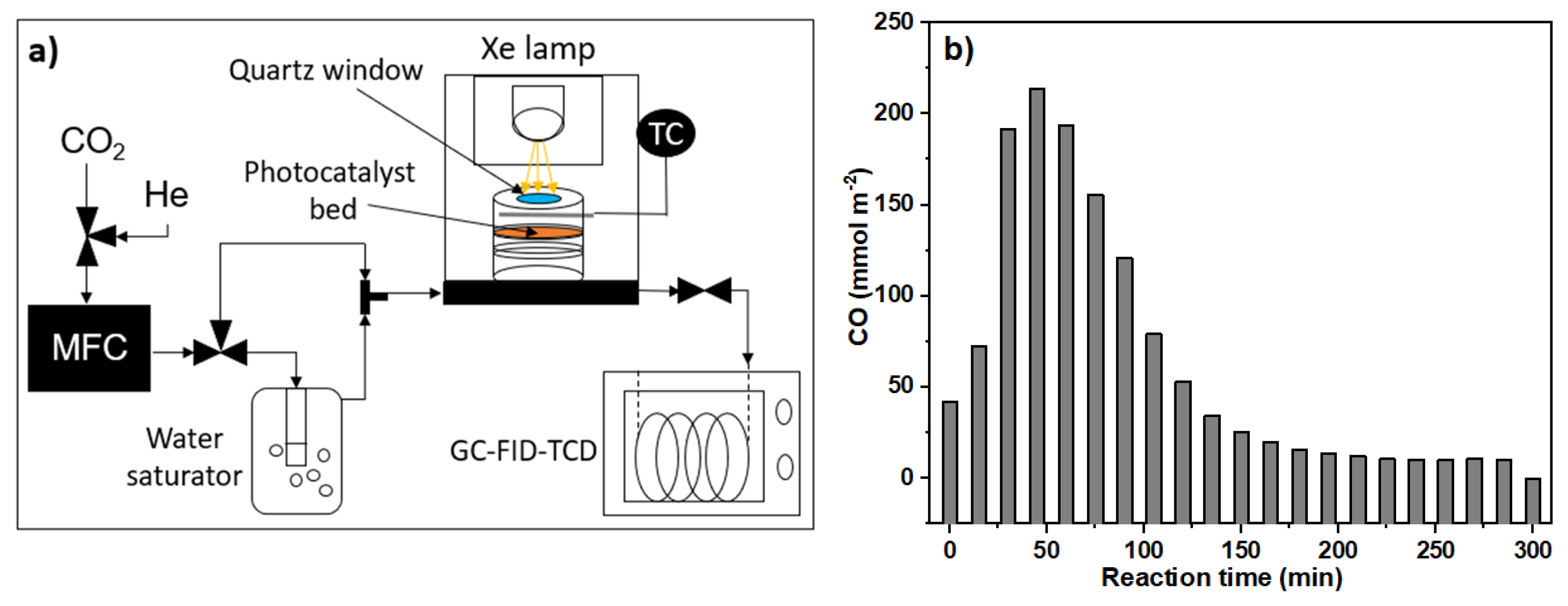

3.4.3. Photocatalytic Activity in Gaseous Media

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

References

- Fernandez-Guzman, D.; et al. A scoping review of the health co-benefits of climate mitigation strategies in South America. The Lancet Regional Health - Americas 2023, 26, 100602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filonchyk, M.; et al. Greenhouse gases emissions and global climate change: Examining the influence of CO2, CH4, and N2O. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 935, 173359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prăvălie, R. Major perturbations in the Earth's forest ecosystems. Possible implications for global warming. Earth-Science Reviews 2018, 185, 544–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.-M.; et al. Co-benefits of greenhouse gas mitigation: a review and classification by type, mitigation sector, and geography. Environmental Research Letters 2017, 12, 123001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravorty, A.; Roy, S. A review of photocatalysis, basic principles, processes, and materials. Sustainable Chemistry for the Environment 2024, 8, 100155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atacan, K.; Güy, N.; Özacar, M. Recent advances in photocatalytic coatings for antimicrobial surfaces. Current Opinion in Chemical Engineering 2022, 36, 100777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichat, P. 4.16 - Photocatalytic Coatings, in Comprehensive Materials Processing, S. Hashmi; et al. Editors. 2014, Elsevier: Oxford. p. 413-423.

- Brattich, E.; et al. The effect of photocatalytic coatings on NOx concentrations in real-world street canyons. Building and Environment 2021, 205, 108312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandolfo, A.; et al. The impact of photocatalytic paint porosity on indoor NOx and HONO levels. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2020, 22, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; et al. Facile one-step synthesis of BiOCl/BiOI heterojunctions with exposed {001} facet for highly enhanced visible light photocatalytic performances. Inorganic Chemistry Communications 2016, 71, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagt, R.A.; et al. Controlling the preferred orientation of layered BiOI solar absorbers. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 2020, 8, 10791–10797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shi, J.; Deng, H. Current status of research on BiOX-based heterojunction photocatalytic systems: Synthesis methods, photocatalytic applications and prospects. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2023, 11, 110311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; et al. A universal method for the preparation of functional ITO electrodes with ultrahigh stability. Chemical Communications 2015, 51, 6788–6791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Cruz, P.T.S.; et al. Preparation of FTO/CU2O Electrode Protected by PEDOT:PSS and Its Better Performance in the Photoelectrocatalytic Reduction of CO2 to Methanol. Electrocatalysis 2020, 11, 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriwong, C.; Choojun, K.; Sriwong, S. High photocatalytic performance of 3D porous-structured TiO2@natural rubber hybrid sheet on the removal of indigo carmine dye in water. SN Applied Sciences 2019, 1, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, A.W.; et al. On the estimation of average crystallite size of zeolites from the Scherrer equation: A critical evaluation of its application to zeolites with one-dimensional pore systems. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2009, 117, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandiyanto, A.B.D.; Zaen, R.; Oktiani, R. Correlation between crystallite size and photocatalytic performance of micrometer-sized monoclinic WO3 particles. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2020, 13, 1283–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Sierra, J.C.; et al. Promoting multielectron CO2 reduction using a direct Z-scheme WO3/ZnS photocatalyst. Journal of CO2 Utilization 2022, 63, 102122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chico-Vecino, M.; et al. Preparation of WO3/In2O3 heterojunctions and their performance on the CO2 photocatalytic conversion in a continuous flow reactor. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2023, 11, 110372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttersack, C. Modeling of type IV and V sigmoidal adsorption isotherms. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2019, 21, 5614–5626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gediz Ilis, G. Influence of new adsorbents with isotherm Type V on performance of an adsorption heat pump. Energy 2017, 119, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthik, P.; et al. Synthesis of highly visible light active TiO2-2-naphthol surface complex and its application in photocatalytic chromium(VI) reduction. RSC Advances 2015, 5, 39752–39759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, M.; et al. Evolution of rough-surface geometry and crystalline structures of aligned TiO2 nanotubes for photoelectrochemical water splitting. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 10870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad Kafle, B. Effect of Precursor Fluorine Concentration Optical and Electrical Properties of Fluorine Doped Tin Oxide thin Films. Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 47, 6389–6397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Hernandez, J.M.; et al. An enhanced photo(electro)catalytic CO2 reduction onto advanced BiOX (X = Cl, Br, I) semiconductors and the BiOI–PdCu composite. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).