1. Introduction

Mental health difficulties disproportionately affect young people in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) compared to other global regions [

1]. A recent systematic review found that adolescents (10–19 years) in SSA experience mental health conditions at higher rates than global and other low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) averages, with a prevalence of 26.9% for depression, 29.8% for anxiety disorders, 40.8% for emotional and behavioural problems, and 20.8% for suicidal ideation [

2]. Globally, approximately 35% of mental health disorders onset by the age of 14 and 75% before the age of 25 years [

3,

4,

5], making adolescence and young adulthood critical periods for the promotion of positive mental health and early intervention.

Increasing mental health awareness and enhancing mental health literacy are important strategies for promoting mental health and well-being among young people. Mental health literacy refers to “knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders that aid their recognition, management, or prevention” [

6]. Greater mental health literacy is associated with more positive attitudes toward mental health professionals and increased help-seeking behaviors [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Conversely, limited mental health literacy has been linked to lower help-seeking and higher rates of anxiety and depression [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Adolescents and young adults have been identified as particularly important target groups for initiating and improving mental health awareness and literacy [

15] to support young people in developing social and emotional foundations for mental well-being.

Despite its significance, mental health literacy among young people remains low worldwide [

16], and SSA has some of the lowest levels of mental health awareness, especially among children and adolescents, who also report low confidence in mental health services [

17]. There is a lack of population-level data on mental health awareness and limited mental health education campaigns for young people in SSA, contributing to ongoing stigma and limited help-seeking [

17]. Low levels of mental health literacy and persistent stigma are compounded by limited access to services and inadequate investment in mental health systems, particularly in rural areas [

18,

19]. Public health sectors in SSA lack sufficient funding, management, and services for mental health, with estimates that up to 90% of individuals with mental conditions in these regions do not receive any treatment [

1].

Faced with a high mental health disease burden and a severe shortage of mental health workers, SSA has become a promising region for digital health innovation, increasingly turning to digital solutions for prevention and health system strengthening [

20]. A meta-analysis of 144 digital mental health interventions found positive effects on mental health outcomes, especially when digital tools were combined with in-person components [

21]. These tools can help scale mental health support where in-person infrastructure is limited, especially in rural areas [

22,

23,

24].

Digital health solutions designed with young people offer promising opportunities due to their wide reach, cost-effectiveness, and potential for anonymity [

25], but the evidence base for digital mental health interventions in SSA remains limited. While millions of mental health applications exist globally, few are evidence-based, and even fewer have been evaluated in SSA [

26]. Much of the current digital mental health evidence is from internet-based interventions often requiring smartphone access, which is a challenge in SSA, where smartphone penetration was only 55% in 2023, compared to 71% globally [

27]. Among youth 15-24 in Africa, only an estimated 40% use the internet, and the percentage is lower in low-income countries in the region [

28], and rural populations remain particularly disadvantaged in accessing digital healthcare services due to barriers such as limited connectivity and the high cost of data [

17].

To be effective, digital health interventions not only need to leverage the appropriate technology but must be tailored to the local context, designed in local languages, and co-created with communities to ensure acceptability and uptake [

29]. One promising approach is

gamification, incorporating game-like elements into initiatives, which several studies have found to increase engagement among young people [

30,

31]. Such features are not only important for uptake but can also enhance learning and retention. There is a growing opportunity to develop and evaluate digital mental health interventions for young people, particularly in rural areas, that are accessible on basic mobile phones, provide relevant information using engaging strategies, and reflect the realities of connectivity, affordability, and technology access.

Recognizing the opportunity for digital mental health interventions targeting youth in SSA, Grassroot Soccer (GRS) and Viamo partnered to develop Digital MindSKILLZ, an interactive voice response (IVR) mental health game accessible through Viamo’s platform. GRS is an adolescent health organization that uses a positive youth development approach, play-based education, and near-peer mentors to improve health and promote well-being. Since its founding in 2002, GRS has reached over 20 million young people with its evidence-based SKILLZ programs that use football (soccer) language and activities to convey critical health messages. GRS has demonstrated program effects through numerous studies on such topics as HIV prevention, gender-based violence, and substance use [

32,

33,

34]. Viamo is a global social enterprise founded in 2012, specializing in leveraging mobile technology to deliver impactful information and services to underserved populations. Through its platform, Viamo has reached over 25 million people across 25 countries, utilizing voice-based technologies like IVR and SMS. By partnering with local telecom providers, Viamo ensures that its services are accessible on basic mobile phones, making it possible to reach remote and digitally disconnected communities.

The current paper presents an evaluation of the initial seven-month phase of the Digital MindSKILLZ intervention. The goal of the evaluation was to inform the future delivery of the intervention by addressing two aims:

Assess the reach, feasibility, and acceptability of the intervention (i.e., the digital game) by country and user demographics;

Assess knowledge of mental health topics among users based on responses during users’ engagement with the intervention.

2. Methods

2.1. Digital Game Overview

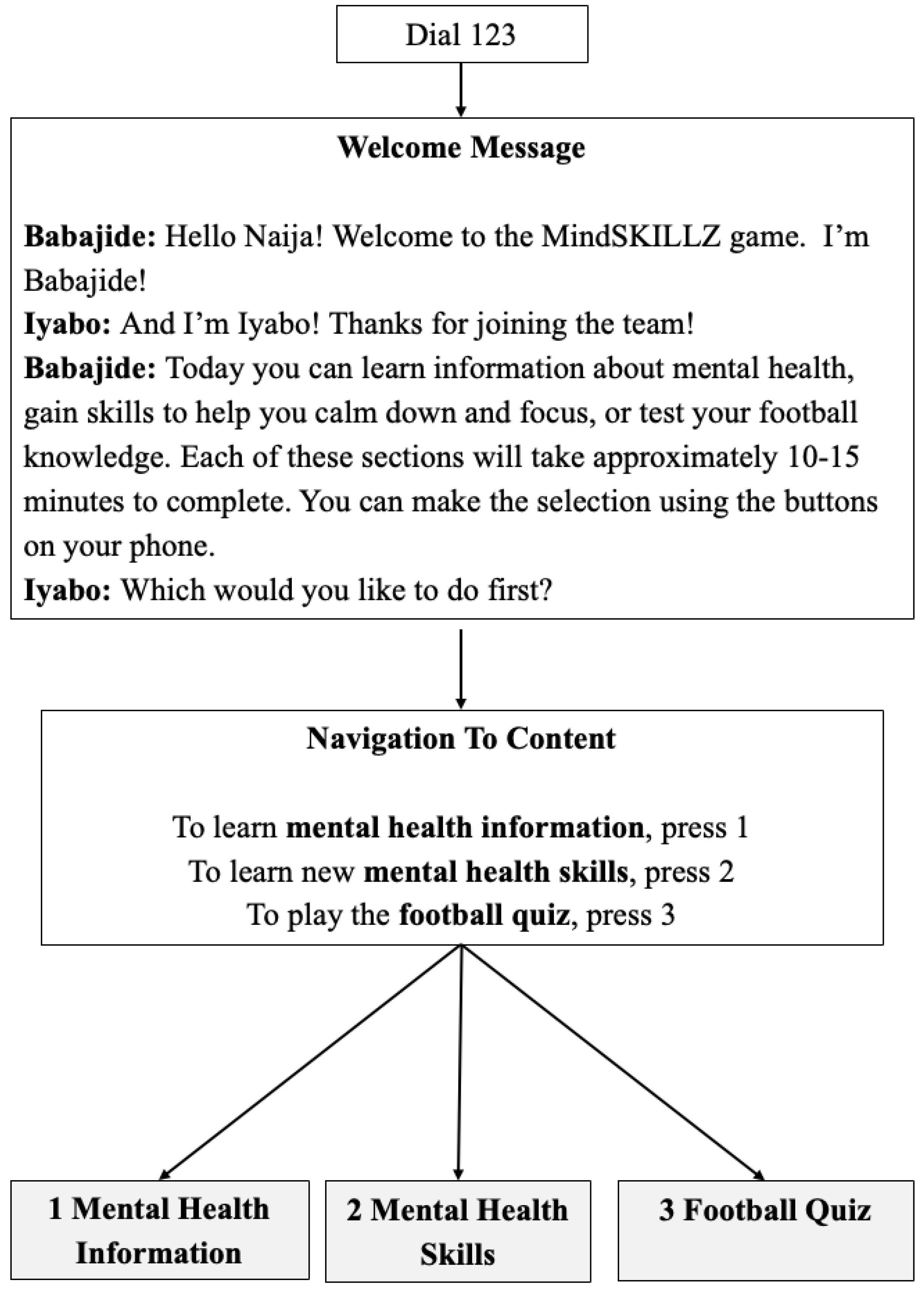

Digital MindSKILLZ is an IVR-adapted version of GRS’s MindSKILLZ program, an in-person mental health promotion intervention for adolescents. Viamo’s IVR platform is an automated telephone system that allows users to interact with pre-recorded audio content using their mobile phone keypad. When a user dials in, they are greeted with a menu of options and navigate the experience by pressing keys corresponding to different choices. Each selection triggers a specific voice recording, creating a branching, choose-your-own-adventure experience. Digital MindSKILLZ includes three main branches that users select from: mental health information, mental health skills (interactive coping strategies like guided breathing), and football-themed quizzes. The entire experience is accessible on even the most basic mobile phones, making it ideal for low-resource settings. An overview of the game’s storyboard is provided (

Figure 1), along with sample audio clips from the game (See Multimedia Appendix 1-3).

Figure 1 is a visual representation of the main menu and overview of the user journey and game structure, including branching decision points and interactive elements. The text is from the game in Nigeria before translation into local languages.

Each of the three branches of the intervention is structured as a menu-driven experience, with approximately 45 minutes of voice-recorded messaging across the entire game. In the mental health information branch, users can select one of four topic areas: "Me and My Mental Health," "Keeping Good Mental Health," "Know the Facts," or "Getting Support." Each topic leads to a series of short, voice-recorded messages covering key concepts such as the definition of mental health, identifying stressors, debunking myths, and strategies for seeking help. The full branch takes approximately 20 minutes to complete, with users able to return to the main menu, continue to the next branch, or exit the game after completing each topic. In the mental health skills branch, users choose from five mental health skills focused on relaxation techniques, emotional regulation, and strengths identification. Users learn the skill via guided instructions (1.5 to 3 minutes per skill, 10-15 minutes in total). The football quiz branch of the game provides options for answering local and international questions about football, with 5-6 questions in each (5-10 minutes in total).

2.2. Intervention Development

Digital MindSKILLZ was developed using an iterative, youth-centered framework for designing digital health interventions [

35], including the following steps:

Step 1: Logic Model, Storyboard, and Scripts. The foundation of the Digital MindSKILLZ game was established through the development of a structured logic model and scripted content. The logic model defined the intervention's intended outcomes, including improved mental health knowledge, awareness of coping skills, and reduced stigma around mental health. The storyboard provided a visual representation of the user journey, mapping the flow of the game and key decision points. Finally, GRS drafted scripts that a group of “Coaches” (near-peer lay mental health providers) reviewed to ensure they were engaging, culturally relevant, and age-appropriate;

Step 2: Preliminary Audio-Recording and Youth Engagement. Once the scripts were finalized, preliminary voice recordings were produced using youth voice actors. A pilot evaluation of the draft game was conducted with young people in Lagos, Nigeria [

36]. Participants (n=25) played the game and then participated in focus group discussions to evaluate the content's clarity, relevance, and impact. The pilot results informed key revisions, particularly in ensuring that mental health concepts were clearly defined and relatable, and including a broader range of mental health topics;

Step 3: Refinement and Re-Recording. Based on user feedback, the game underwent content refinement. Additional mental health information and coping strategies were incorporated, including explanations of the differences between mental health and mental illness. The football quiz was expanded to include internationally relevant questions. Following these updates, the scripts were re-recorded to enhance clarity and engagement;

Step 4: Contextualization and Translation. The Digital MindSKILLZ game was adapted for deployment in multiple countries, including the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Nigeria, Rwanda, Uganda, and Zambia. Local Viamo teams reviewed the content and facilitated translations into local languages. To further improve appropriateness, youth voice actors from each country recorded the localized versions.

2.3. Deployment and User Onboarding

Digital MindSKILLZ is deployed through Viamo’s IVR platform. Viamo’s platform delivers accessible, voice-based content known widely as the 3-2-1 Service. Accessible on any mobile phone, without requiring internet access, the platform leverages partnerships with Mobile Network Operators (MNOs) to provide toll-free or low-cost access to users, including those in remote or underserved communities. These partnerships also enable proactive promotion of the platform via daily digests, SMS, voice blasts, and USSD push messages. In addition to these digital outreach methods, platform visibility is further amplified through co-promotion efforts by validated content partners such as UNICEF and various government agencies. These partners support awareness campaigns through radio spots, community events, posters, and targeted SMS campaigns, helping drive platform uptake. In some instances, grassroots users themselves facilitate onboarding within their communities by hosting listening parties and encouraging referrals, further extending the platform’s organic reach.

First-time callers are welcomed in their preferred language, introduced to the IVR system, and guided through a streamlined onboarding process. They are then invited to explore a menu of available content, including educational programs, entertainment, news, and games. After initial exposure to the platform’s offerings, users are prompted to opt in and optionally register by sharing demographic data (e.g. Do you agree to be contacted occasionally to receive information and to participate in surveys to share your opinion on matters important to you?). Returning users follow an adaptive journey tailored to their preferences and interaction history, receiving personalized content such as daily news, weather updates, or direct access to their most-used programs.

Viamo users opt into the Digital MindSKILLZ game and can return directly to the game in future sessions. The game was rolled out in phases by country.

Table 1 provides information about the launch date and number of days the game was “live” in each country during the evaluation period, along with the MNO and the game’s available languages.

Table 1 details the launch date, duration of availability, MNO, and game language for each country where Digital MindSKILLZ was deployed. The number of days active was calculated as the number of days from the launch date to March 20, 2025, the period of data collection used for this evaluation.

2.4. Evaluation Design

This evaluation employed a descriptive, multi-country, cross-sectional design. The evaluation was conducted during the first seven months following the phased rollout across six countries: the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Nigeria, Rwanda, Uganda, and Zambia. We drew on the implementation outcomes framework [

37] to look at three implementation outcomes (Aim 1), which we defined as follows:

Reach: The number, proportion, and characteristics of individuals who access Digital MindSKILLZ. We substituted the IOF’s outcome of penetration [

37] with Glasgow’s definition for reach [

38], given its greater applicability for delivery in community versus service settings.

Feasibility: The extent to which Digital MindSKILLZ can be successfully implemented across countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

Acceptability: The perception that Digital MindSKILLZ is agreeable, palatable, or satisfactory.

We also examined mental health knowledge based on users’ engagement with the mental health information branch of the game, specifically via users’ responses to true-false statements about mental health (Aim 2).

2.5. Measures

Demographics: We measured participants’ age using the following age categories: under 18, 18-24, 25-34, 35-44, 45 years and above. We measured gender (female or male), language, and geographic location using county and sub-county information as captured by mobile metadata or self-report. Geographic data, collected as Counties or Districts, were categorized as either urban or rural based on publicly available geographic data.

Reach: We measured the number of callers who dialed the platform and reached the main menu and the number of unique users—i.e., the number of individuals who accessed at least one voice recording during the game.

Feasibility: We examined participant engagement as the average number of voice recordings accessed by each unique user. We also measured the number of unique users per full calendar month, disaggregated by country. We measured adherence as the number and proportion of messages completed in each of the three branches of the game (i.e., 18 messages in the information branch, 5 in the skills branch, and 11 in the football branch).

Acceptability: We included three measures of acceptability: 1) comprehension: post-game user-reported understanding of the content, with three response options: "Understood all messages", "Understood some messages", and "Did not understand the messages”; 2) helpfulness: post-game user feedback on the most helpful aspect of the game, with the three response options: "Mental health information", "Mental health skills", and "Football quiz”; and 3) overall satisfaction: post-game rating of likelihood to recommend the game to a friend, with three response options: "Very likely", "Not sure", and "Very unlikely."

Mental health knowledge: We measured mental health knowledge based on users’ responses to 18 true-or-false statements embedded within the mental health information branch of the game. The statements were developed by GRS to align with the intervention’s content and objectives.

2.6. Data Collection Procedures

The evaluation dataset included all users who accessed the game between 1 September 2024 and 20 March 2025 and engaged with at least one voice-recorded message. The game platform enabled the real-time capture of user interaction and demographic data. Once a caller accessed the platform, the system automatically captured key behavioral and technical data points—including the caller’s phone number, unique contact ID, date and time of call, menu selections, content accessed, listening duration, and the user’s journey through the system. This real-time, passive data collection was embedded within the IVR experience, requiring no additional effort from the user and enabling seamless analytics across millions of interactions. All passively collected data were initially stored locally on Delivery Nodes (DNs), which were securely hosted within the data centers of MNOs in each country. Periodically, data were synchronized with Viamo’s centralized Cloud Node (CN), where the data were aggregated and reviewed to inform platform enhancements, monitor engagement patterns, and support partner reporting needs.

In parallel with passive data collection procedures, Viamo incorporated an optional, active user-friendly registration process to gather demographic information (as described above). Prompts were presented at carefully selected intervals to avoid fatigue and preserve the user experience. Before collecting these data, users had to provide their consent. Using event-based analytics combined with user-consented data collection provided a high standard of data privacy.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

This evaluation was determined not to involve human subjects research by the Office for the Protection of Research Subjects at the University of Illinois Chicago (Submission ID: STUDY2025-0614; determination issued June 12, 2025). No identifiable private information was accessed or analyzed, and no interaction with users occurred. All data collection adhered to Viamo’s user consent procedures and data privacy protocols.

2.8. Analyses

De-identified data were exported from Viamo’s centralized Cloud Node (CN) dashboard in Excel and CSV formats and shared with GRS for analysis. Descriptive and comparative analyses were conducted using SPSS (Version 30). Metrics were disaggregated by country, gender, and age group (i.e., under 18 and 18-24 years) to examine patterns and variations in user reach and engagement. To examine mental health knowledge (Aim 2), a filter was used to identify users of the mental health information branch of the intervention. An individual-level dataset (n=130,486) with unique IDs was generated and exported from Viamo’s cloud database. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize mental health knowledge data.

3. Results

3.1. Reach

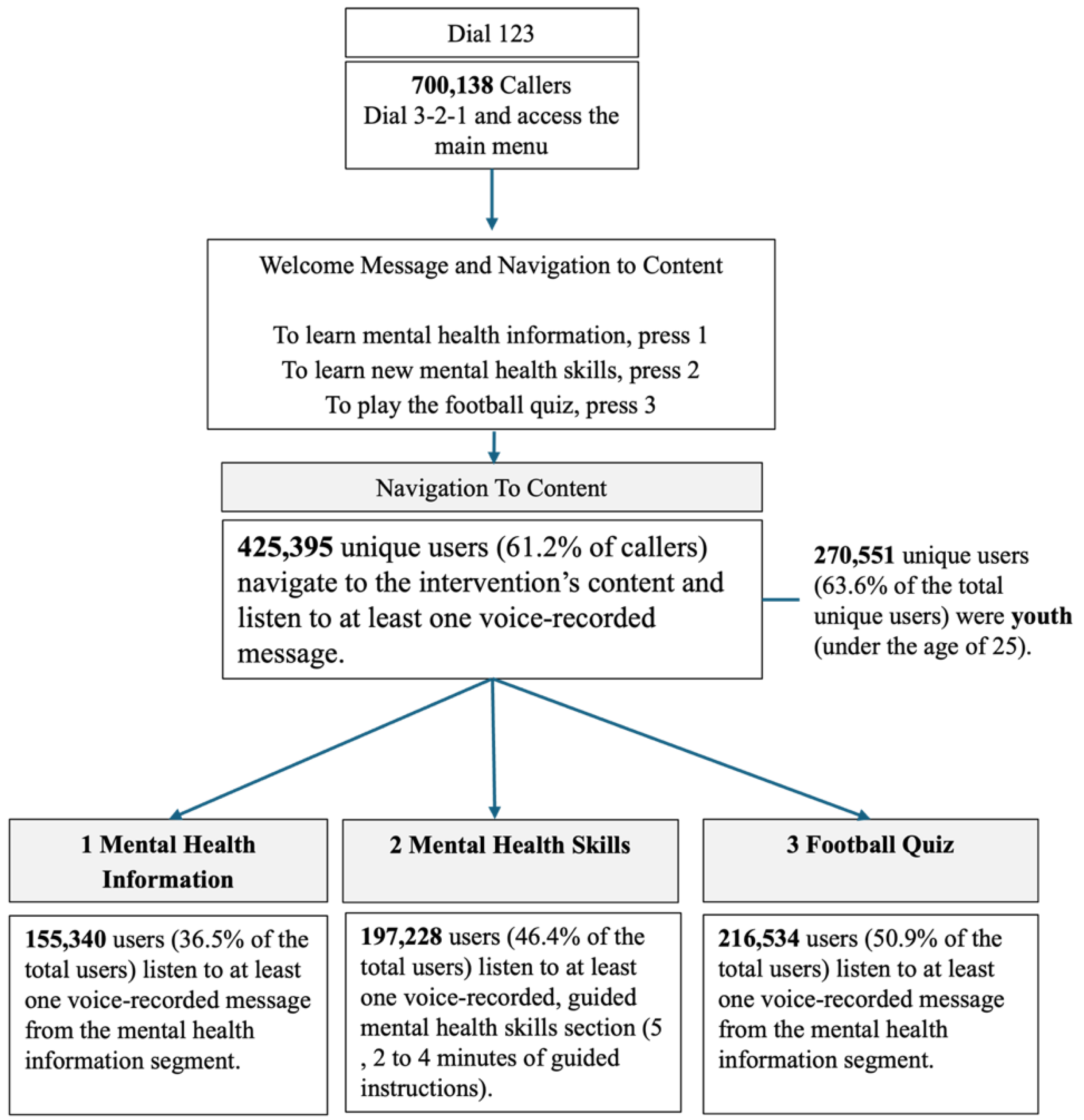

Regarding the reach of the Digital MindSKILLZ intervention, 700,138 individuals called in to the platform (i.e., “callers”). Of these, 425,395 individuals (61.2%) navigated to at least one of the three branches of content and listened to at least one voice-recorded message (i.e., “unique users”). Among these unique users, 270,551 (63.6%) were youth under the age of 25 years. The flow and progressive narrowing from callers to unique users engaging with the specific components of the intervention is illustrated in the top half of

Figure 2.

The figure presents a flow diagram summarizing reach and engagement with the IVR intervention. It illustrates the sequence from calling the service to selecting among three content options: mental health information, mental health skills, and a football quiz. The visual quantifies the number of total callers, the proportion who became unique users by accessing content, and the distribution of users across different content areas.

Uganda accounted for nearly 60% of all users (

Table 2). The gender distribution was generally balanced (46.4% female, 52.5% male), though country-specific differences were pronounced; for instance, only 22% of users in DRC identified as female compared to 66% in Rwanda. Despite being designed for youth, the intervention also reached adults aged 25 and older (n=154, 844 or 36.4% of the total users). The age distribution varied notably across countries: Rwanda had the youngest audience (80% under 25), while Uganda had the oldest, with 44% of users aged 25 or older. Of note, almost three-quarters of users were from rural areas, ranging from 62.6% in Uganda to 82.4% in Rwanda.

Table 2 presents disaggregated demographic data—gender, age, and rurality—of unique users by country who accessed the Digital MindSKILLZ game.

3.2. Feasibility

Participant engagement varied across the game’s three branches: 36.5% accessed mental health information, 46.4% engaged with guided mental health skills, and 50.9% participated in the football quiz (bottom of

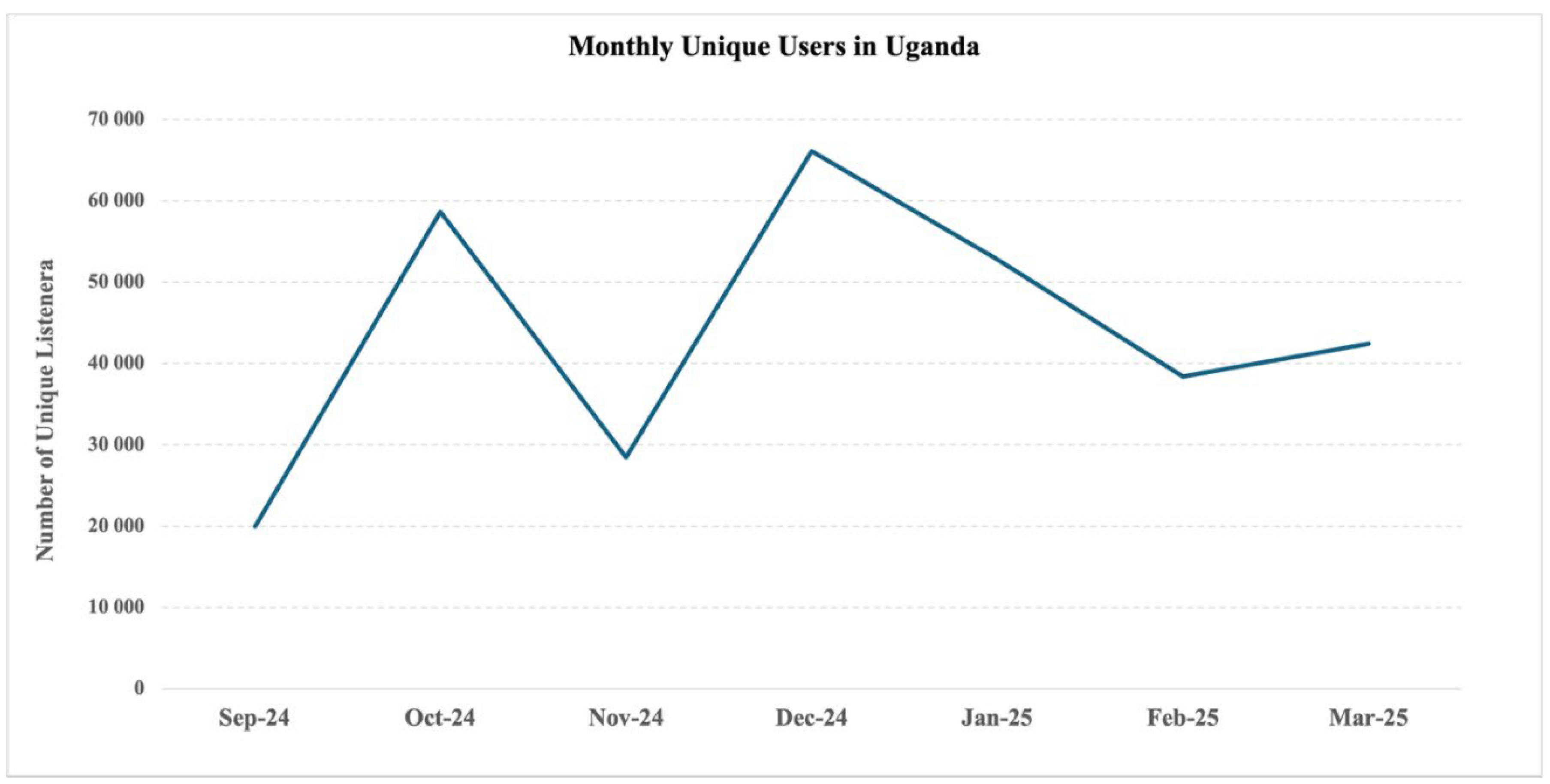

Figure 2). Among unique users, the average number of voice recordings completed was 5.4, equating to approximately 5–15 minutes of content. Country-level variation was substantial, with Nigeria demonstrating the highest average engagement and DRC the lowest (8.1 versus 3.7 recordings per user). Monthly trends revealed differing trajectories in unique users. In Uganda, the number of unique users fluctuated monthly but increased overall (

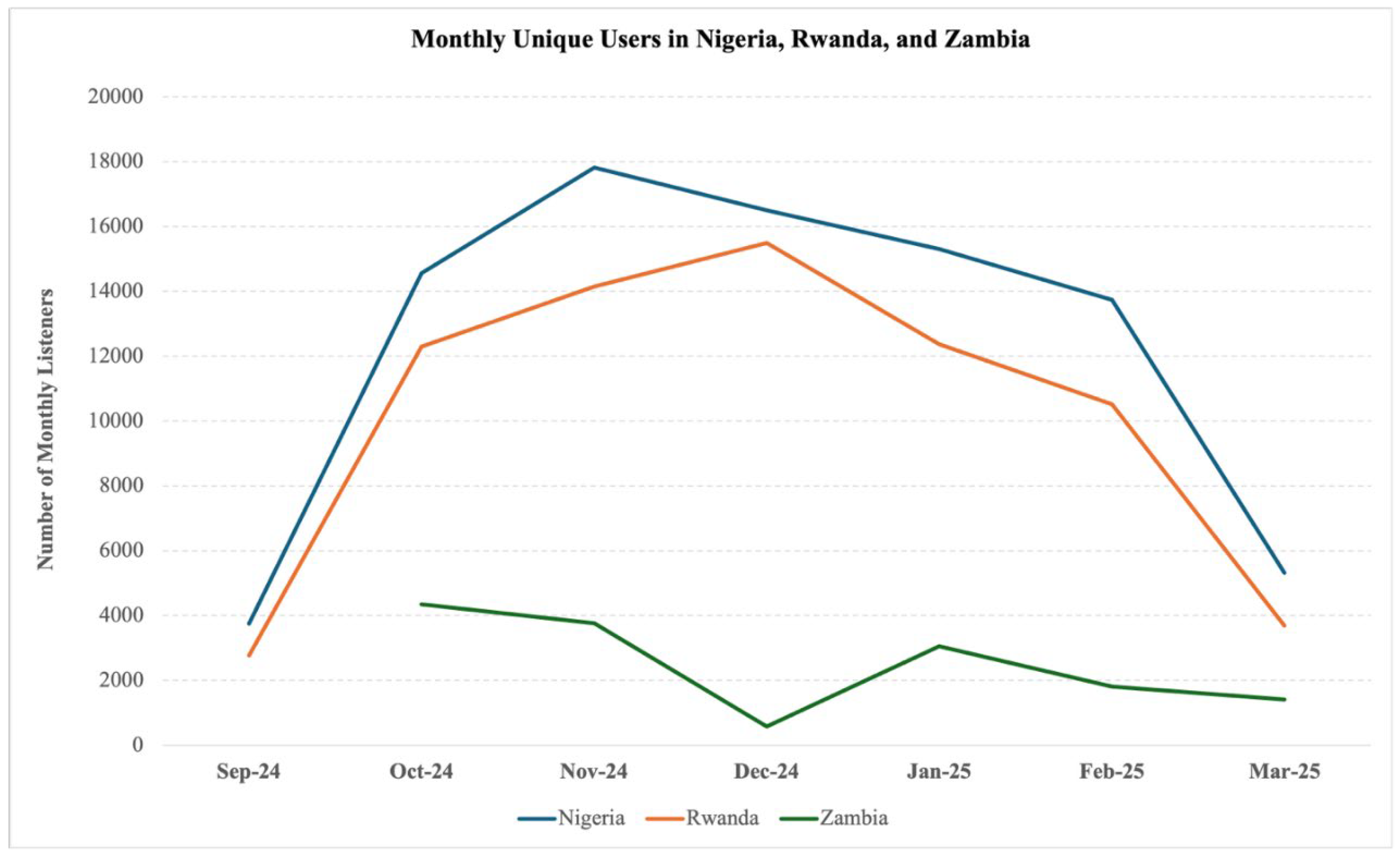

Figure 3), whereas Nigeria and Rwanda saw peak engagement during months 3–4, followed by a steady decline, while the number of unique users in Zambia declined continuously after the launch (

Figure 4), and Ghana had consistently low uptake. Although DRC was live for only two months at the time of data extraction, unique users nearly tripled from February to March.

Figure 3 displays the number of unique users accessing the game in Uganda per month during the evaluation period.

Figure 4 compares monthly trends in unique user engagement across Nigeria, Rwanda, and Zambia following the game’s launch in each country, and during the evaluation period

3.3. Participant Engagement with Different Content Areas (Branches)

Among users who interacted with the mental health information branch, the average number of mental health messages completed was 7.6. Country-level engagement was highest in Uganda (mean = 7.9 messages). Engagement did not differ significantly by age group or gender. However, a consistent attrition pattern was observed, with a minor but steady (-2% to -5%) decline in completion across the message sequence. Regarding adherence, 25,778 (16.7%) of unique users completed at least two-thirds of the mental health information segment (≥12 messages), while 3,948 (2.5%) users completed all 18 messages. The mental health skills branch consists of five, guided relaxation, emotional regulation, and strength identification techniques.

The entertainment component of the game, the football quiz, comprises 11 voice-recorded messages with true-or-false questions about local and international football trivia. On average, users listened to 4.4 messages (40% of the available content), with country-level averages ranging from 3.6 in Zambia to 5.7 in Rwanda. Engagement with the quiz did not vary meaningfully by age or gender. When given the option to choose between local and international football trivia, nearly 85% of users selected the local quiz. The mental health skills branch was popular, with 46% of all users listening to at least one of the five voice-recorded message. These voice-recorded messages were structured differently (e.g., longer, guided instructions) and limited analysis and comparisons with the other two branches.

The entertainment component of the game, the football quiz, comprises 11 voice-recorded messages featuring true-or-false questions about local and international football trivia. On average, users listened to 4.4 messages (40% of the available content), with country-level averages ranging from 3.6 in Zambia to 5.7 in Rwanda. Engagement with the quiz did not differ meaningfully by age or gender. When offered a choice between local and international trivia, nearly 85% of users selected the local quiz. The mental health skills branch also attracted considerable interest, with 46% of all users listening to at least one of the five voice-recorded messages. However, the structure of these messages, longer and more instructional, limited direct comparison with the other two branches.

3.4. Acceptability

Data revealed high acceptability of the game. Among the 134,439 respondents to the post-game comprehension question, “Did you understand the game’s content?” over 91% reported they understood some or all of the content. When asked, “What aspect of the game did you find most helpful?”, 38% selected mental health information, 33% the football-themed quiz, and 27% the mental health (coping) skills activities. When asked, “How likely are you to recommend the game to a friend?”, 85% of users (n=110,185) reported that they were “very likely” to recommend it. While sub-group analyses by age and gender revealed minimal variation in game acceptability, country comparisons revealed an that users DRC were noticeably less likely to recommend the game to a friend (57.6%) compared to other countries.

3.5. Mental Health Knowledge

An average of 55,000 responses was received across the 18 items in the mental health information branch. Analysis of the 18 mental health knowledge items revealed an overall correct response rate of 62%, indicating moderate awareness among users (

Table 3). However, the proportion of correct responses varied considerably by item. Users demonstrated a high understanding of basic mental health practices and support-seeking behaviors, with correct responses reaching 93% for the item, “When a friend asks for help with a mental health problem, listening carefully is a great first step” (Item 16), and 89% for “getting enough sleep is one of the best things we can do for good mental health” (Item 7). In contrast, misconceptions were observed around emotional expression, stigma, and the distinction between mental health and mental illness. For instance, 79% incorrectly equated good mental health with “being happy all the time” (Item 1), while only 23% correctly disagreed with the statement, “Feeling sad means you have depression” (Item 14), and only 36% correctly rejected the idea that “keeping feelings inside helps others understand what you need” (Item 4). Additionally, 66% of users agreed with the statement, “People with mental health problems are weak” (Item 11). When categorized by the thematic areas used within the game, users scored highest on “Keeping Good Mental Health” (mean = 76.2%) and “Getting Support” (65.0%), followed by “Know the Facts” (56.4%) and “Me and My Mental Health” (50.8%).

Table 3 shows the percentage of users who correctly answered each true-or-false mental health knowledge item, organized by thematic category from the game content. *Percentage of respondents providing the desired response.

4. Discussion

Despite an increasing global interest in digital mental health tools, particularly among youth, most evidence comes from high-income countries and internet-based interventions that require smartphones or consistent internet access [

21,

26]. This evaluation presents data collected over a seven-month period on a large-scale, voice-based, gamified mental health intervention for young people in sub-Saharan Africa. We found very high reach, with over 700,000 people from six countries reaching the platform, and 425,000 people (270,551 under 25 years) listening to at least one voice-recorded message. The game’s reach among rural users, who comprised three-quarters of all users, was particularly notable given recognized challenges of engaging rural youth in mental health interventions, including digital health [

39].

Regarding feasibility, giving users self-directed options may have increased overall engagement with the platform but adherence to the intervention’s mental health branch was still low, with users listening to an average of 7.6 of the 18 messages (42.2% of the branch’s messages), mimicking challenges identified in other studies in digital mental health with wide variability in user adherence and engagement [

25,

40,

41]. To better contextualize these results, internal data from Viamo’s broader IVR platform suggests that users typically engage with 3–4 audio messages per session. In comparison, Digital MindSKILLZ users completed an average of 5.4 messages, rising to 7.6 among those engaging with the mental health branch of the game, above platform-wide averages reported by Viamo. However, completion of all 18 messages in the mental health branch remained low (2.5%), consistent with known challenges in sustaining attention in digital interventions [

41,

42,

43]. While no exact benchmarks for IVR-based mental health interventions exist, these figures suggest that the intervention performed at or above engagement norms for the platform. The high reported acceptability is encouraging, as it is a strong predictor of future uptake [

44]. The evaluation also revealed critical gaps in mental health knowledge among users, highlighting the potential for mental health literacy initiatives in the region.

In line with our goal of informing the future delivery of the Digital MindSKILLZ game, we generated the following recommendations for improving the game:

1. Optimize Onboarding to Improve Early Engagement and Adherence. Drop-off rates (i.e., call but do not listen to a voice recording) ranged from 34% to 69% across countries, underscoring the need for further investigation into user expectations, onboarding processes, and early-stage game design, as well as barriers and facilitators to participant engagement [

25,

45,

46]. It remains unclear whether users disengaged due to technological factors (e.g., poor connectivity or delays), misalignment between expectations and content, or insufficient motivation to proceed beyond the main menu. Optimizing user onboarding and restructuring the initial game flow may enhance early engagement and reduce attrition [

47]. The impact of segmentation and branching, of providing user-driven exploration of the intervention, on engagement and adherence also remains unclear. Conducting A/B testing is recommended to compare this approach with a linear experience where users follow a shorter, fixed path.

Ensure Entertainment is a Bridge to Learning. User preferences point to a need for a better understanding of the balance between entertainment and educational content. More users engaged with the football quiz than with mental health information. While this suggests the quiz effectively engaged users, it also raises questions about whether it acted primarily as an entry point or a distraction from the game’s mental health objectives. There is a need to explore whether entertainment components serve as meaningful bridges to health content or a distraction.

Strengthen Mental Health Measures Embedded in the Game. Correct responses to the 18 true/false items ranged widely, from 17% to 93%. Scores from over 130,000 respondents, mostly young people from rural communities who are typically underrepresented in mental health research [

48,

49], revealed low knowledge in key areas, including the distinction between mental health and mental illness, signs of common disorders, stigma, and emotional literacy. Future iterations should incorporate validated measures where possible and explore including a post-game questionnaire. Comparing positively and negatively worded versions of in-game statements may help deepen understanding of gaps in key mental health knowledge areas. Future iterations should further involve youth in determining what they want to know about mental health (e.g., developing content based on users’ mental health questions).

Adapt Content and Delivery to Country-Specific Realities. Participant engagement varied widely by country. For example, Nigerian users listened to more than twice as many voice recordings on average (mean = 8.1) compared to those in DRC (mean = 3.7). Uganda showed not only the highest number of total users but also the most sustained month-on-month growth in the number of users. There is a need to explore the factors contributing to the variable levels of engagement.

Addressing the Digital Gender Gap. Overall, gender distribution among the game’s users was balanced (45.9% female), but gender disparities existed in some countries, most notably DRC, where only 22% of users identified as female, and these mirror broader digital inequities in SSA. These disparities are shaped by a mix of structural, economic, and social factors, including access to phones, household norms, and digital literacy [

50,

51]. To promote equitable reach, future versions should include intentional strategies to engage girls and young women, such as girl-focused outreach, content co-creation, and collaboration with women-led community structures.

Develop Models for Long-Term Engagement and Game Sustainability. Monthly unique user trends raise important questions about the game’s long-term engagement and sustainability. Nigeria, Rwanda, and Zambia have experienced steady declines in participant engagement after peaking in the first few months after the game’s launch, while Uganda’s monthly engagement was more sustained, with higher-than-average engagement in month seven. These dynamics raise questions about the necessary steps to maintain user engagement over time, such as periodic promotion, content updates, or integration with other platforms or initiatives. Addressing these questions will be essential for sustaining the game’s impact.

Plan Future Study of Game Effectiveness. Building on results from this evaluation, further study using a more rigorous design and additional data collected is recommended. A study is planned to examine the game’s effectiveness in improving the mental health literacy of young people in Malawi. GRS and Viamo aim to investigate questions raised by this evaluation and build on the initial findings.

4.1. Limitations

This evaluation had several limitations. The cross-sectional evaluation design limits our ability to assess the game’s effectiveness in imparting mental health knowledge and skills, given our inability to examine changes in user knowledge post-game. Future studies are needed to address this limitation. Although the platform passively captured engagement and basic demographic data, it did not capture insights into user motivation or qualitative feedback. These insights could have deepened our understanding of the user experience with the game and barriers and facilitators to access and engagement. The mental health knowledge items were not drawn from validated measures of mental health literacy or related constructs, which may limit their construct validity and reliability, though they were customized to align with the game content.

5. Conclusions

The evaluation of Digital MindSKILLZ demonstrates the reach of an IVR-based game in delivering mental health information to large numbers of youth in low-resource settings across six sub-Saharan African countries. Despite high initial drop-off and variable adherence, over 425,000 users engaged with the game, most of them under 25 and from rural areas. High acceptability and user feedback highlight the promise of the intervention for building mental health literacy. This evaluation’s insights provide a strong foundation for improving the game’s design and reach. Additionally, this evaluation will provide critical information that will inform the future study of the Digital MindSKILLZ game in Malawi, which is currently being planned.

Author Contributions

CB: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, visualization, writing (original draft). CN: Writing (original draft). KK: data curation, formal analysis. PN: Project administration, writing (review and editing). DL: Writing (review and editing). AD: Conceptualization, supervision. PO: supervision. DKA: Formal analysis, writing (original draft). KM: Methodology, visualization, writing (review and editing).

Funding

This research received no external funding. It was supported by Grassroot Soccer’s internal unrestricted funding, consisting of numerous private donations from individuals to support the organization’s mission.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This evaluation was determined not to involve human subjects research by the Office for the Protection of Research Subjects at the University of Illinois Chicago (Submission ID: STUDY2025-0614; determination issued June 12, 2025). The analysis was limited to de-identified data collected by Grassroot Soccer (GRS) and Viamo as part of routine program monitoring. No identifiable private information was accessed or analyzed, and no interaction with users occurred. All data collection adhered to Viamo’s user consent procedures and data privacy protocols.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all users who voluntarily provided demographic data or participated in optional surveys on the platform. All passive interaction data were de-identified and collected in accordance with Viamo’s user consent procedures and data privacy protocols.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions and data-sharing agreements with Grassroot Soccer, Viamo and Mobile Network Operators.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the staff, youth actors, and communities who made this project possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no declarations of interest to disclose.

Abbreviations

GRS: Grassroot Soccer

IVR: Interactive Voice Response

LMIC: Low- and Middle-Income Countries

MHL: Mental Health Literacy

MNO: Mobile Network Operator

SSA: Sub-Saharan Africa

References

- Hart C, Norris SA. Adolescent mental health in sub-Saharan Africa: crisis? What crisis? Solution? What solution? Global Health Action 2024;17:2437883. [CrossRef]

- Jörns-Presentati A, Napp A-K, Dessauvagie AS, Stein DJ, Jonker D, Breet E, et al. The prevalence of mental health problems in sub-Saharan adolescents: A systematic review. PLOS ONE 2021;16:e0251689. [CrossRef]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:593–602. [CrossRef]

- Solmi M, Radua J, Olivola M, Croce E, Soardo L, Salazar de Pablo G, et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Molecular Psychiatry 2022;27:281–95. [CrossRef]

- Uhlhaas PJ, Davey CG, Mehta UM, Shah J, Torous J, Allen NB, et al. Towards a youth mental health paradigm: a perspective and roadmap. Mol Psychiatry 2023;28:3171–81. [CrossRef]

- Sodi T, Quarshie EN-B, Oppong Asante K, Radzilani-Makatu M, Makgahlela M, Nkoana S, et al. Mental health literacy of school-going adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa: a regional systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2022;12:e063687. [CrossRef]

- Calear AL, Batterham PJ, Torok M, McCallum S. Help-seeking attitudes and intentions for generalised anxiety disorder in adolescents: the role of anxiety literacy and stigma. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2021;30:243–51. [CrossRef]

- Fung AWT, Lam LCW, Chan SSM, Lee S. Knowledge of mental health symptoms and help seeking attitude in a population-based sample in Hong Kong. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 2021;15:39. [CrossRef]

- Jung H, Von Sternberg K, Davis K. The impact of mental health literacy, stigma, and social support on attitudes toward mental health help-seeking. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2017;19:252–67. [CrossRef]

- Lindow JC, Hughes JL, South C, Minhajuddin A, Gutierrez L, Bannister E, et al. The Youth Aware of Mental Health Intervention: Impact on Help Seeking, Mental Health Knowledge, and Stigma in U.S. Adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health 2020;67:101–7. [CrossRef]

- Dadgarinejad A, Nazarihermoshi N, Hematichegeni N, Jazaiery M, Yousefishad S, Mohammadian H, et al. Relationship between health literacy and generalized anxiety disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic in Khuzestan province, Iran. Front Psychol 2024;14:1294562. [CrossRef]

- Guo C, Cui Y, Xia Z, Hu J, Xue Y, Huang X, et al. Association between health literacy, depressive symptoms, and suicide-related outcomes in adolescents: A longitudinal study. Journal of Affective Disorders 2023;327:15–22. [CrossRef]

- Radez J, Reardon T, Creswell C, Lawrence PJ, Evdoka-Burton G, Waite P. Why do children and adolescents (not) seek and access professional help for their mental health problems? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2021;30:183–211. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Yang R, Li D, Wan Y, Tao F, Fang J. Association of health literacy and sleep problems with mental health of Chinese students in combined junior and senior high school. PLOS ONE 2019;14:e0217685. [CrossRef]

- Mansfield R, Patalay P, Humphrey N. A systematic literature review of existing conceptualisation and measurement of mental health literacy in adolescent research: current challenges and inconsistencies. BMC Public Health 2020;20:607. [CrossRef]

- Freţian AM, Graf P, Kirchhoff S, Glinphratum G, Bollweg TM, Sauzet O, et al. The Long-Term Effectiveness of Interventions Addressing Mental Health Literacy and Stigma of Mental Illness in Children and Adolescents: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Public Health 2021;66:1604072. [CrossRef]

- Renwick L, Pedley R, Johnson I, Bell V, Lovell K, Bee P, et al. Mental health literacy in children and adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: a mixed studies systematic review and narrative synthesis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2024;33:961–85. [CrossRef]

- Saxena S, Saraceno B, Granstein J. Scaling up mental health care in resource-poor settings. Improving Mental Health Care, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2013, p. 12–24. [CrossRef]

- Wainberg ML, Scorza P, Shultz JM, Helpman L, Mootz JJ, Johnson KA, et al. Challenges and Opportunities in Global Mental Health: a Research-to-Practice Perspective. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2017;19:28. [CrossRef]

- Holst C, Sukums F, Radovanovic D, Ngowi B, Noll J, Winkler AS. Sub-Saharan Africa—the new breeding ground for global digital health. The Lancet Digital Health 2020;2:e160–2. [CrossRef]

- Yeo G, Reich SM, Liaw NA, Chia EYM. The Effect of Digital Mental Health Literacy Interventions on Mental Health: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Med Internet Res 2024;26:e51268. [CrossRef]

- Faria M, Zin STP, Chestnov R, Novak AM, Lev-Ari S, Snyder M. Mental Health for All: The Case for Investing in Digital Mental Health to Improve Global Outcomes, Access, and Innovation in Low-Resource Settings. JCM 2023;12:6735. [CrossRef]

- Giebel C, Gabbay M, Shrestha N, Saldarriaga G, Reilly S, White R, et al. Community-based mental health interventions in low- and middle-income countries: a qualitative study with international experts. Int J Equity Health 2024;23:19. [CrossRef]

- McGorry PD, Mei C, Chanen A, Hodges C, Alvarez-Jimenez M, Killackey E. Designing and scaling up integrated youth mental health care. World Psychiatry 2022;21:61–76. [CrossRef]

- Borghouts J, Eikey E, Mark G, De Leon C, Schueller SM, Schneider M, et al. Barriers to and Facilitators of User Engagement With Digital Mental Health Interventions: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res 2021;23:e24387. [CrossRef]

- Lehtimaki S, Martic J, Wahl B, Foster KT, Schwalbe N. Evidence on Digital Mental Health Interventions for Adolescents and Young People: Systematic Overview. JMIR Ment Health 2021;8:e25847. [CrossRef]

- Statista. Global smartphone penetration rate as share of population from 2016 to 2024. 2025.

- International Telecommunication Union. Global Connectivity Report 2022. Geneva, Switzerland: International Telecommunication Union; 2022.

- World Health Organization. WHO guideline: recommendations on digital interventions for health system strengthening. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

- Garrido S, Millington C, Cheers D, Boydell K, Schubert E, Meade T, et al. What Works and What Doesn’t Work? A Systematic Review of Digital Mental Health Interventions for Depression and Anxiety in Young People. Front Psychiatry 2019;10:759. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi A, Panahi S, Sayarifard A, Ashouri A. Identifying the prerequisites, facilitators, and barriers in improving adolescents’ mental health literacy interventions: A systematic review. J Edu Health Promot 2020;9:322. [CrossRef]

- Clark TS, Friedrich GK, Ndlovu M, Neilands TB, McFarland W. An adolescent-targeted HIV prevention project using African professional soccer players as role models and educators in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. Aids and Behavior 2006;10:S77–83. [CrossRef]

- Kaufman ZA, DeCelles J, Bhauti K, Hershow RB, Weiss HA, Chaibva C, et al. A Sport-Based Intervention to Increase Uptake of Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision Among Adolescent Male Students: Results From the MCUTS 2 Cluster-Randomized Trial in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. Jaids-Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 2016;72:S297–303.

- Merrill KG, Merrill JC, Hershow RB, Barkley C, Rakosa B, DeCelles J, et al. Linking at-risk South African girls to sexual violence and reproductive health services: A mixed-methods assessment of a soccer-based HIV prevention program and pilot SMS campaign. Eval Program Plann 2018;70:12–24. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Youth-centred digital health interventions: a framework for planning, developing and implementing solutions with and for young people. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2020.

- Ndlovu P, Lee D, Kuthyola K, Odusolu B, Sekoni A. Pilot Evaluation of Digital MindSKILLZ in Lagos, Nigeria: An Interactive Voice Response Game to Improve Mental Wellbeing of Adolescents 2024.

- Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for Implementation Research: Conceptual Distinctions, Measurement Challenges, and Research Agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health 2011;38:65–76. [CrossRef]

- Glasgow RE, Harden SM, Gaglio B, Rabin B, Smith ML, Porter GC, et al. RE-AIM Planning and Evaluation Framework: Adapting to New Science and Practice With a 20-Year Review. Front Public Health 2019;7:64. [CrossRef]

- Mindu T, Mutero IT, Ngcobo WB, Musesengwa R, Chimbari MJ. Digital Mental Health Interventions for Young People in Rural South Africa: Prospects and Challenges for Implementation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023;20:1453. [CrossRef]

- Fleming T, Bavin L, Lucassen M, Stasiak K, Hopkins S, Merry S. Beyond the Trial: Systematic Review of Real-World Uptake and Engagement With Digital Self-Help Interventions for Depression, Low Mood, or Anxiety. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2018;20:e9275. [CrossRef]

- Giebel GD, Speckemeier C, Abels C, Plescher F, Börchers K, Wasem J, et al. Problems and Barriers Related to the Use of Digital Health Applications: Scoping Review. J Med Internet Res 2023;25:e43808. [CrossRef]

- Baumel A, Muench F, Edan S, Kane JM. Objective User Engagement With Mental Health Apps: Systematic Search and Panel-Based Usage Analysis. J Med Internet Res 2019;21:e14567. [CrossRef]

- Torous J, Nicholas J, Larsen ME, Firth J, Christensen H. Clinical review of user engagement with mental health smartphone apps: evidence, theory and improvements. Evid Based Mental Health 2018;21. [CrossRef]

- Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis JJ. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Services Research 2017;17:88. [CrossRef]

- Damschroder LJ, Reardon CM, Opra Widerquist MA, Lowery J. Conceptualizing outcomes for use with the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR): the CFIR Outcomes Addendum. Implement Sci 2022;17:7. [CrossRef]

- Weiner BJ, Lewis CC, Stanick C, Powell BJ, Dorsey CN, Clary AS, et al. Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implementation Science 2017;12:108. [CrossRef]

- Lipschitz JM, Pike CK, Hogan TP, Murphy SA, Burdick KE. The engagement problem: A review of engagement with digital mental health interventions and recommendations for a path forward. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry 2023;10:119–35. [CrossRef]

- Perowne R, Rowe S, Gutman LM. Understanding and Defining Young People’s Involvement and Under-Representation in Mental Health Research: A Delphi Study. Health Expectations 2024;27:e14102. [CrossRef]

- Warraitch A, Wacker C, Bruce D, Bourke A, Hadfield K. A rapid review of guidelines on the involvement of adolescents in health research. Health Expect 2024;27:e14058. [CrossRef]

- GSMA. The Mobile Gender Gap Report. GSMA; 2024.

- Peláez-Sánchez IC, Glasserman-Morales LD. Gender Digital Divide and Women’s Digital Inclusion: A Systematic Mapping. Multidisciplinary Journal of Gender Studies 2023;12:258–82. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).