Part I: Muscle Weakness as a Psychoneurokinesiological Disorder

1. The Cost of Musculoskeletal Disorders

Musculoskeletal conditions affect about 1.7 billion people worldwide [

2] with far-reaching consequences. For individuals, pain and reduced function may lead to work, financial, and family hardships, opiate addiction [

3] along with diminished well-being and quality of life. Employers in the US spend

$353 billion on musculoskeletal care [

4], with productivity losses averaging

$3,105 per affected employee annually [

5]. This contributes to an overall economic burden approaching

$1 trillion (5.6% of GDP) [

6]. Incidence is expected to increase as the population ages. Pain is the primary complaint in most musculoskeletal conditions.

1.1. Non-Specific Musculoskeletal Dysfunction; a Major, Poorly Addressed Problem

An estimated 75-95% of musculoskeletal patients have non-specific musculoskeletal disorders (nsMSDs) — conditions lacking specific nociceptive, anatomical, or organic lesions that could induce pain [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. This creates what O’Sullivan calls "a diagnostic and management vacuum," resulting in treatment of signs and symptoms "without consideration for the underlying basis or mechanism for the pain disorder" ([

9] p. 243).

Although the term "non-specific" is most often used to describe idiopathic low back pain [

3,

6,

7,

10,

11,

12], the designation also has been applied to the temporomandibular joint and neck [

2], knees [

8], and shoulders or arms ([

5], but nsMSDs may manifest in any area of the body.

A “biopsychosocial model” for nsMSDs has been proposed, holding that thoughts, emotions, beliefs, and social factors may contribute to these conditions, particularly non-specific low back pain [

7,

13,

14,

15], with related constructs offered for conditions including function weakness (FW) [

16] and kinesiophobia [

17].

This review affirms the biopsychosocial model — with a critical twist. While we often think of thoughts, emotions, beliefs, and social interactions as conscious experiences, these entities also operate in the dark, in ways unavailable to conscious awareness. We are therefore addressing a problem that is rarely put into words: ‘how can we clinically address processes that are hidden from the clinician as well as the patient — which cannot be directly that cannot be directly observed, felt, or expressed?’

1.2. Motor Control, Muscle Weakness, and nsMSDs

To explore these hidden mechanisms, we turn to models of learning and motor control that explain how the brain may predict and adapt movements in ways that may ultimately cause more problems than it corrects — all outside of conscious awareness.

Muscle weakness appears to be ubiquitous nsMSD patients, whether their symptoms are active or in remission [

7,

9,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. This weakness is usually subclinical, unknown to the patient until it is revealed with manual muscle testing (MMT), which assesses muscles one at a time. Throughout this paper, “Mw” signifies the clinical finding of “muscle weakness” and/or “maladaptive weakness” — its assumed neural origin.

Individual muscle weakness may be the most easily evaluated tip of an iceberg of aberrant muscle activation. In many musculoskeletal conditions, muscles or subsets of motor units display altered force, timing, and coordination in conjunction with pain [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Attributed to motor control alterations, a complex feedback loop is established [

28], making unclear when or if pain triggers Mw or Mw leads to pain [

29,

30]; it is likely to be both. Delayed activation is sometimes noted [

31,

32,

33,

34], and perhaps a common denominator in muscles testing weak [

35].

Larger patterns of alteration may include co-contraction of opposing muscles leading to stiffness [

36], excessive or overly limited variability in muscle function [

37], and protective postures or guarding behaviors [

38,

39]. As a secondary effect of pain, kinesiophobia — the fear and avoidance of moments or activities the individual believes will be painful or harmful — causes avoidance of associated organized motor actions and activities [

40,

41,

42].

A “pain adaptation model” holds that inhibition is the primary response of muscles in response to nociception and pain [

23,

43]. A “vicious cycle model” speculates that increased muscle activity (spasm) prevails [

44]. The theories explored in this review will support the pain adaptation model as primary. More importantly for people in pain however, the clinical side of this review will argue that, out of all the abnormal motor expressions, Mw is the easiest to assess and treat. In addition to this ease being borne out in the clinical experience of this author and others, we observe that when Mw is corrected, larger patterns of abnormal motor function appear to be normalized as well, though more study is needed to validate this.

The treatments for muscle weakness we will describe may be curative, not compensatory, because they putatively remove the underlying lesion. This review will conclude that that the generative lesion of Mw is outdated, distorted or invalid information retained from painful or traumatic encounters in conjunction with using particular muscles. This leads to ongoing predictions of pain or trauma when using those muscles and avoidance of reliance on those muscles. When tested, these muscles display a particular quality: they are unable achieve an isometric plateau or lock. We can call this “maladaptive weakness”, giving “Mw” dual meaning.

Tight connections between mechanism, assessment, and treatment of Mw exist, the explanation of which requires the presentation of diverse concepts, theories, and evidence.

1.3. Clinically Interacting with Muscle Weakness and Motor Control

During an injury, the body may respond with inherent defensive and withdrawal movements or reactions to the specifics of the trauma. These patterns of reaction might become locked in as ongoing responses [

45,

46,

47]. According to Levine (and others, in related explorations), at least one form of this response may be caused by the inherent impulse to complete unresolved defensive responses [

48,

49,

50,

51]. These patterns might be understood as “positive” or active responses to trauma that continue beyond their time of need.

The “negative”, inhibitory, passive, or avoidance responses we will be discussing may have the primary effect of muscle inhibition. Avoidance represents different mechanisms, though it is possible that the finding of Mw could also represent a reciprocally-induced shadow of the (positive) trauma response. Based on the ‘law’ of reciprocal inhibition, we would expect muscles opposing those that are continually (tonically) or periodically (phasically) activated to be similarly inhibited, due to spinal processes [

52].

A variety of tests or evaluations have been developed to assess the efficacy of motor control. These include electromyography [

53,

54], balance and center of pressure measures [

29,

55,

56], evaluation of joint position sense, motion analysis, and functional movement control tests [

57,

58]. Though at times difficult to compare, some of these tests have shown good interrater reliability, but as noted by Schulz, Vitt & Niemier and Brandt et al., validity data — does the test measure what it is supposed to measure in a clinically useful way — remains questionable [

59,

60]. Much of the literature does not differentiate Mw from other forms of motor control deficits.

Current treatment approaches for motor control dysfunction are inconclusive about long-term effectiveness. A 2016 meta-analysis showed that motor control exercises (MCEs), which focus on retraining of specific dysfunctional patterns, are no more effective than other exercise modalities or manual therapies [

61], but a more recent study found MCEs to be effective at reducing pain and disability [

59]. In combination with musculoskeletal therapies like massage and spinal manipulation MCEs were found to be significantly more effective [

62]. Spinal manipulation alone has been shown to evoke short term improvements in factors of motor control [

63,

64,

65].

It is apparent, however, that Mw (alone or as part of larger motor control changes) is not considered a reversible condition in most literature. In physical therapy and orthopedic literature, weakness found following pain or injury in the absence of organic conditions is often referred to as ‘arthrogenic muscle inhibition’ (AMI). Although therapies exist that temporarily suspend the weakness [

66,

67,

68,

69,

70], muscles affected by AMI are well known to be resistant to trophic development with exercise, so atrophy (hypotrophy) may be a secondary effect of AMI [

22,

68,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76]. Atrophy is not a feature of all muscle inhibition ([

77] p.7). Weakness resulting from AMI and concomitant atrophy are therefore likely to persist beyond functional and symptomatic recovery [

22,

78,

79,

80].

Crucially, we treat Mw as reversible. Since 1964, practitioners of Applied Kinesiology (AK) and related disciplines have developed and honed a protocol applying reflex and spinal manipulative therapies that can immediately reverse Mw, one muscle at a time [

81,

82,

83,

84,

85]. In a study central to this review, a psychotherapeutic method, accepted for the treatment of PTSD, was found to produce similar, immediate, and lasting resolution of Mw — supporting a unified model of its cause and correction [

86]. Immediate recovery of function in individual muscles is a keynote of successful therapies, suggesting memory updating, not tissue healing or development.

Mw assessment via MMT also needs reappraisal. The defining features of the MMT response — the objective phenomenology of MMT — become fully evident only when force and motion over time (FM/T) are recorded. Phenomenological approaches aim to capture the essential features of experience or events [

87].

FM/T data have only recently been collected, and their implications have not been integrated into the broader MMT literature. As

Section 6.1 will show, FM/T analyses — especially when paired with insights into muscle physiology — suggest that certain key aspects of MMT may have been misinterpreted or overlooked for over a century. These findings, along with evidence we will show suggesting that MMT results directly reflect the underlying pathology of motor control causing Mw, highlight a gap between clinical assessments, treatments, and underlying mechanisms of muscle weakness in both Mw and AMI.

Accordingly, research expanding MMT’s capacity to over 600 muscles — introduced around 1980 — enables quantitative clinical assessment of motor control at both regional and global levels.

1.4 Disambiguating terminology

Having introduced Mw as both the clinical finding of muscle weakness and its maladaptive neural origin, we can now distinguish it from related terms in the literature.

“Muscle inhibition” typically refers to acute or chronic weakness induced by neural processes, while AMI signifies weakness linked to joint trauma, alongside broader neurological explanations for its persistence. AMI, however, has no formal diagnostic criteria, and the International Classification of Diseases lacks a code specifying AMI or other references to diffuse weakness of individual muscles [

88]. Consequently, it remains unclear whether a particular muscle weakness is due to AMI or other causes [

77].

Perhaps because of diagnostic ambiguity, the absence of restorative treatments, and educational deficits, AMI and its short-term interventions are often overlooked by clinicians [

69].

Mw and AMI describe the same observable phenomenon: subclinical weakness in individual muscles. Their mechanistic explanations are complementary, not mutually exclusive. In this regard, AMI and Mw are largely synonymous. They diverge in their evidence base, and how it is used to understand mechanisms, assessments, and treatment strategies.

Muscle “weakness” describes a determination agnostic regarding cause. We will use it in the same way here, referring to amorphous clinical findings or when discussing literature that may refer to weakness from various or unnamed causes.

1.5. Maladaptive Neuroplasticity, a Missing Link in Motor Dysfunction?

The diagnostic and therapeutic challenge of addressing nsMSDs necessitates a re-evaluation of current models of musculoskeletal care. Central sensitization, a well-documented form of maladaptive neuroplasticity, involves structural, functional, and chemical changes that make the central nervous system (CNS) hypersensitive to sensory stimuli, particularly pain [

89]. Through processes similar to associative learning, normally non-noxious stimuli become linked to pain pathways, leading to persistent pain states that extend beyond tissue healing [

90]. These altered neural patterns represent a form of implicit memory where the nervous system "remembers" and anticipates pain, even in its absence. According to Bonin and De Koninck, spinal memories that might induce pain via this mechanism, may be subject to erasure through memory reconsolidation [

91] which will be covered in more detail later.

With more emphasis on motor function, Pelletier, Higgins, and Bourbonnais argue that maladaptive neuroplasticity in the CNS is a key factor in nsMSDs. This challenges the prevailing "structural-pathology paradigm" which assumes that the cause of symptoms can be found locally at the site of pain or injury. They propose that these changes result from associative learning which links movements with pain or trauma, affecting sensory processing, motor control, and pain perception. They identify the failure to address these maladaptive neuroplastic changes as a "missing link" in musculoskeletal care, and call for a new paradigm to fill that gap [

92]. Just as central sensitization represents maladaptive learning in pain processing, this review will argue that Mw represents maladaptive learning in motor function — both potentially sharing mechanisms of maladaptive neuroplasticity.

Like PTSD, we will argue, Mw is a behavioral adaptation, encoded into memory in a two-stage learning process that can be treated by elimination of its maladaptive learning. Instead of operating on parameters often described as “emotional”, these principles may specifically affect motor function, here examined at the level of single muscles.

A high-level description posits a simple progression through which muscle weakness is acquired and resolved:

Pain, stress, or trauma, occurring in temporal proximity to the contraction of a muscle, associates the sensory and motor events.

The association leads to a prediction that use of the muscle will re-engage the experience of pain/trauma. Thus, use of the muscle is avoided, the first stage of the response.

In the second stage, new combinations of muscles (muscle synergies) are developed. These new synergies, which avoid using muscles associated with pain or trauma, tend to be less efficient and potentially maladaptive, yet they become the preferred choice for functional activities.

As in two-stage avoidance learning models often applied to PTSD, the habitual use of avoidance patterns prevents exposure to corrective experiences that could reintegrate the avoided muscles, once “healing” has occurred.

The mechanism of action for (putatively) successful treatments for Mw is the elimination of muscle-pain/trauma associations through the blockage of memory reconsolidation.

1.6. Muscle, Motor, or Movement PTSD and Psychoneurokinesiology

To understand the underlying mechanisms of Mw, this review advances the 'muscle, motor, or movement post-traumatic stress disorder' (mPTSD) Model, derived from a hypothesis validated by Weissfeld (2021). This will be further examined in

Section 5.

This paper further proposes psychoneurokinesiology (PNK) as an overarching designation for the study of how psychological factors, mediated by the nervous system, affect movement and motor function. Like psychoneuroimmunology [

93] studies the effects of behavioral conditioning on immune and endocrine systems, PNK investigates how learning processes may lead to enduring changes in motor behavior.

Psychological influences on movement are already implicated in conditions such as chronic pain, kinesiophobia, and functional weakness (FW), and they may play a role in other conditions: e.g. focal dystonia [

94] and cognitive-motor interference patterns [

95]. While these studies typically address the coordination of multiple muscles, the mPTSD Model adds a complementary perspective by proposing a mechanism for altered function at the level of individual muscles. Framing these diverse observations under the umbrella of PNK may support the development of a shared theoretical foundation for understanding the role of psychological learning in movement disorders.

Developing in response to pain, injury, or trauma, normal brain processes — prediction and reinforcement learning — can produce maladaptive outcomes when they operate based on internal models that are outdated, distorted, or no longer relevant. Maladaptive responses may persist long after the initial triggers have ceased.

Integrating three concepts — Mw as a clinical manifestation, mPTSD as a possible underlying mechanism, and PNK as a broader framework — offers a novel paradigm for understanding, assessing, and treating functional movement disorders; nsMSDs in particular. While further empirical validation is needed, this perspective invites interdisciplinary dialogue and may help bridge existing gaps between psychological theory, neurophysiology, and clinical practice.

1.7. Aims and Methods of This Theoretical Review

This review has two core aims: 1) to define learning processes underlying Mw, and 2) to show how these processes can inform clinical practice. We approach this through two complementary frameworks: reinforcement learning (RL) and predictive processing (PP). Each offers a distinct view of maladaptive motor control.

Our methodology is integrative and transdisciplinary drawing from musculoskeletal medicine, neuroscience, psychology, physiology, motor control, and trauma research. The non-systematic review enables synthesis across domains that are rarely combined but provides new insights when integrated within the mPTSD Model.

The key hypotheses for which supporting evidence is provided are:

Mw is a binary dysfunction.

MMT outcomes reflect this binary nature.

MMT directly assesses motor control integrity.

Mw is a central feature of motor dysfunction in nsMSDs.

Disruption of memory reconsolidation may resolve Mw.

The mPTSD Model elucidates potential mechanisms underlying the development and resolution of Mw by connecting RL, PP, maladaptive neuroplasticity, and memory reconsolidation. These mechanisms are speculative, offering several ways these behavioral principles might be applied to explain a cause for Mw. Other interpretations may also be possible.

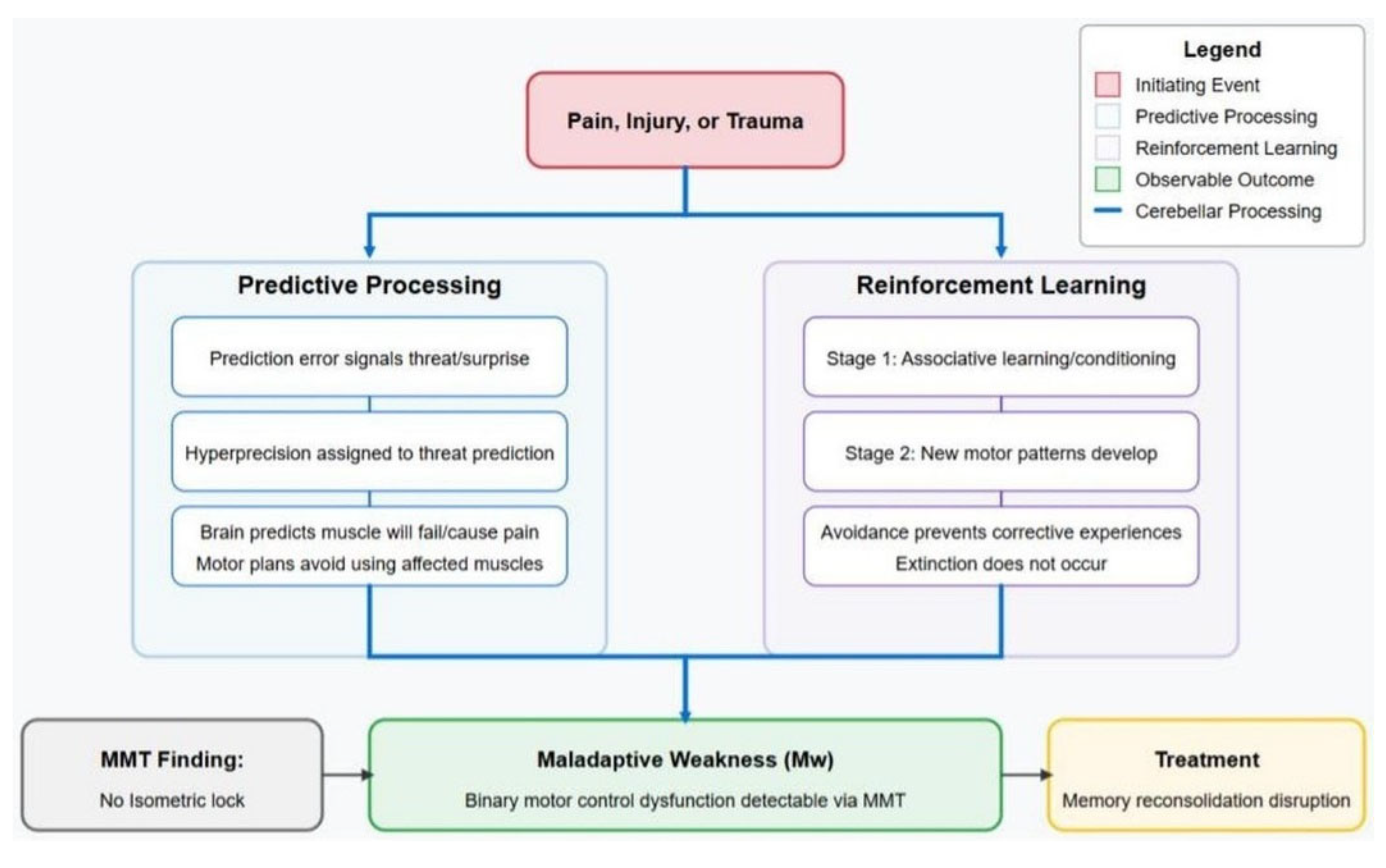

Figure 1 illustrates that the mPTSD Model can be understood through complementary frameworks of PP and RL, both explaining how Mw develops, is detected through MMT, and potentially resolved through interventions that disrupt memory reconsolidation.

2. Prevalence and Impact of Mw in nsMSDs

Muscle weakness is frequently documented across a wide range of conditions, including non-specific chronic low back pain [

9,

22,

32] whiplash-associated disorders [

96], and lower extremity conditions such as patellofemoral and other knee pain syndromes [

21,

27,

97], and ankle instability [

98,

99]. Weakness is also seen in plantar fasciitis [

100], headaches [

101], and various "overuse" injuries [

102,

103].

2.1. The Functional Impact of Muscle Weakness

Muscle weakness also disrupts coordination, stability, and functional performance. Key consequences include:

Altered movement patterns: To avoid loading inhibited muscles, patients adopt compensatory movements that may reduce biomechanical efficiency [

30,

104].

Joint instability: Weak stabilizing muscles can undermine joint function, accelerating degeneration [

105,

106].

Reduced performance: Weakness impairs athletic performance and raises susceptibility to reinjury [

26,

107,

108].

Chronicity and recurrence: Unresolved weakness may contribute to the progression from acute to chronic conditions and predispose to recurrence, even in asymptomatic individuals. [

54].

Kinetic chain dysfunction: Weakness in one region can disrupt proprioception and stability throughout the body, particularly the lower extremities [

109,

110].

Persistent pain: Weakness and pain may form a self-sustaining loop—each reinforcing the other [

11,

111].

Even in asymptomatic individuals, muscle weakness may induce functional impairment [

112,

113], ankle instability [

98,

114], gait disturbance [

115,

116], and osteoarthritis [

105,

117,

118]. Roos et al. (2010) noted that muscle function correlates more closely with joint pain than joint-space narrowing. Muscles play a crucial role in maintaining joint mobility, stability, and shock absorption. Mw, which may undermine the protective role of muscles, may therefore be a better predictor of disability than structural findings alone. Pain may not reflect actual tissue damage, but instead act as a warning signal in response to impaired motor control or joint instability [

119,

120,

121].

In occupational and athletic settings, undetected (subclinical) Mw, remaining after apparent recovery, therefore represents a significant yet potentially addressable risk factor for repetitive stress injuries, ongoing pain, and reinjury. This underscores the utility of implementing the comprehensive testing and correction methods that we will be discussing, practical tools that could allow clinicians to better identify and resolve these hidden vulnerabilities.

2.2. Muscle Weakness and Chronic Pain

Potential relationships between persistent Mw and central pain sensitization suggests potential clinical implications beyond motor control. Biomechanical inefficiency resulting from Mw may increase nociceptive input through altered joint loading patterns [

30] and abnormal tissue stress [

122]. Maladaptive learning mechanisms underlying Mw may simultaneously facilitate central sensitization. Cerritelli et al. describe how maladaptive predictive processing (which we cover next) can generate and maintain pain sensitization through persistent error signaling [

123]. This bidirectional relationship—with pain creating Mw through associative learning, which then perpetuates nociceptive input — underscores the importance of addressing Mw both for improved motor function and potentially as an intervention to interrupt persistent pain states.

3. Predictive Processing; the First Theoretical Framework of Mw

As stated above, PP and RL comprise two frameworks using different models to describe the same outcome: muscle weakness.

PP, including the free energy principle (FEP) and active inference (AInf) present a view of how the brain interprets sensory information and generates movements. Predictive processing frameworks offer explanatory power that traditional models lack, particularly in explaining how transient pain events may lead to persistent motor changes.

3.1. Core Concepts of Predictive Processing

The brain continuously generates predictions based on prior experiences. These predictions form internal or generative models of the body and environment that guide perception and action. The FEP suggests that the brain actively seeks to minimize "free energy" — a proxy for surprise, uncertainty, or prediction error. [

124]. Prediction error is the difference between the expected state of the body (interoceptive sensations) and the world (exteroceptive sensations) and its actual state. Prediction errors represent potential threats to homeostasis and survival.

AInf describes how organisms minimize surprise by adjusting either their internal predictions or their actions to align with incoming sensory input [

125].

Generative models represent prior knowledge the brain holds about possible states of the body and world, which constrain the range of possible predictions. (While I might fondly imagine it, prior experience does not allow me to predict that I will dunk the basketball I am holding.) The brain's goal is to offer predictions that keep the organism operating within these bounded states, thereby minimizing surprise (free energy) [

126,

127].

3.2 Precision weighting and perceptual bias

A crucial aspect of PP is precision weighting — the confidence assigned to either prior (top-down) beliefs or (bottom-up) sensory inputs. When there is high precision (confidence) in prior beliefs, perception is biased more toward expectations than actual sensory evidence. Placebo effects for instance, may be related to the weighted top-down prediction of a positive result from a treatment [

128]. The capacities we believe we have affect perception: babies who could crawl showed fear when placed next to a fake cliff, while non-crawling babies showed none [

129].

Conversely, when there is high confidence in sensory input, perception is biased toward the sensory information rather than expected outcomes [

130,

131]. For instance, individuals who are fatigued or carrying heavy packs estimate upcoming distances to be longer and hills to be steeper [

129].

3.3. Trauma, Pain, and Predictive Processing

In PTSD, the brain may develop hyperprecise priors (generative models biased toward predicting adverse outcomes) that override contradictory input, causing benign stimuli to trigger defensive responses [

132,

133]. A door slamming shut may evoke predictions of adverse consequences in a combat veteran, despite cognitive knowledge and sensory cues indicating a safe environment.

In response to these predictions, the brain invokes physiological defenses - preparations to fight, flee, or freeze [

134,

135]. In a vicious cycle, even unconscious interoceptive feedback may reinforce maladaptive responses: physiological arousal becomes evidence that the threat is real, entrenching the original prediction [

136,

137,

138]. This interoceptive feedback may be consciously interpreted as fear, anxiety, or other emotional states [

139].

A similar process may occur in chronic pain, where past experiences lead the brain to predict pain despite the absence of noxious stimuli [

138,

140,

141].

3.4. Motor Control and Active Inference

In the AInf model, rather than issuing commands, the motor system is said to generate predictions of the desired sensory outcomes (e.g., joint position, and the feeling of grasping a cup). Comparing these predictions to actual input, mismatches (prediction errors) drive reflexive adjustments in the spinal cord to achieve the predicted state. This challenges our intuitions about movement, which we typically understand as commands to contract muscles.

As intentions, predictions are top-down, and errors, determined by sensory differences proceed from the bottom-up. To reach for an object, the prefrontal cortex forms the intention or goal, which prompts the premotor cortex to generate predictions about trajectory and hand positioning. These predictions are translated into a motor plan by the primary motor cortex (M1) [

125]. Emerging from M1 via the corticospinal tract, the predicted proprioceptive end state (goal) of the movement acts as an attractor that the motor system fulfills. In the spine, predictions are compared to current proprioceptive input from sensory receptors. The mismatch generates a prediction error, which activates spinal memories and reflexes to contract muscles and move the limb to minimize the error [

124,

125,

126,

142].

3.5. Arthrogenic Muscle Inhibition as Predictive Processing

The phenomenon of chronic muscle weakness following injuries has been discussed for centuries [

143,

144], but it was not until the 1980s that it was called arthrogenic muscle inhibition (AMI) [

145]. In physical therapy and orthopedic literature, functional isolated muscle inhibition is usually classified as AMI. Most reporting on AMI has emerged from studies of knee pain and injury, particularly following anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture and reconstruction, with quadriceps inhibition garnering the most attention [

67,

106,

116,

146,

147,

148,

149,

150,

151].

AMI is generally assumed to be an adaptive defense to protect already injured tissues from further injury [

80]. To whatever extent this is true, if muscles remain inhibited, the defense becomes maladaptive. Weakness called AMI is often found bilaterally in unilateral conditions, an indication of CNS involvement [

21,

80,

113,

152]. Research now suggests that AMI begins with local joint injury or pain, but later, or perhaps in addition, central, and perhaps peripheral plasticity establishes maladaptive neuronal patterns that sustain activation deficits in otherwise healthy muscles [

27,

70,

153].

For reasons of cost, speed, efficiency, and flexibility in testing a wide variety of muscles, MMT and hand-held dynamometry (HHD) are the most common forms of muscle assessment in clinical practice [

154,

155,

156], but AMI research tends to employ other methods including: H-reflex testing [

104,

157,

158], electromyography (EMG) [

26], and burst superimposition (aka interpolated twitch) testing, in which a muscle's maximum voluntary (isometric) contraction (MVC or MVIC) is compared to its electrically enhanced contraction [

98,

99,

147,

159,

160,

161]. This may present an obstacle to translation of these results to clinical practice.

AMI may be described through the lens of PP. We can presume that pain and injuries are always surprising when they first occur. Injuries in particular arise as errors in prediction. For instance, the prediction that my foot will smoothly transition from one step to the next is violated when my ankle inverts as I step on the edge of a curb. The mismatch between what is expected and what occurs updates my brain’s generative model, adding a new possibility of failure or pain when performing the common action [

162,

163,

164,

165]. Pain or fear may accelerate and reinforce that learning [

166,

167,

168,

169].

Even after successful recovery, the generative model may still hold the prediction of failure for the muscles that failed during the initial injury. In an ankle inversion injury, the peroneus muscles, which evert the foot, have failed to do their job. In PP terminology, the brain may now hold a hyper-precise prediction that the peroneus muscles will fail, so it produces motor predictions (traditionally called motor plans) that rely as little as possible on those muscles. Indeed, the peroneus muscles are often chronically weak after ankle inversion sprains [

98,

99,

114]

Alternatively, or perhaps in addition, the sensory prediction error arising from the joint during the injury (accompanied by nociceptive signals and pain) may lead to an over-weighting of proprioceptive output from that joint, again tied to prediction of its failure. In research that led to the “arthrogenic” designation, the (over) activation of joint mechanoreceptors during injuries was found to trigger inhibitory spinal interneurons that presynaptically inhibit alpha motor neurons of muscles around the joint [

25,

26,

80,

170].

In the PP model this response might manifest as a prediction that proprioceptive afferents emerging from the joint will inhibit alpha motor neurons. This bottom-up, hyper-precise prediction may lead to avoidance of use of muscles predicted to fail, and consequent failure of the muscles when assessed with MMT. If weakness is predicted to occur when afferent signals arise from a joint, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. This possibility is reinforced by evidence showing that blockage of afferent signals arising from joints temporarily ablates the weakness of AMI, allowing inhibited muscles to be responsive to exercise, potentially reducing atrophy [

67,

70,

153].

3.6. Kinesiophobia, Mw, and Predictive Processing

Kinesiophobia — fear of movement due to expected pain or damage to the body — can similarly be defined as stemming from maladaptive predictions. Kinesiophobia contains consciously available beliefs about the pain; for instance, that the pain signifies further damage will occur in an affected joint [

142,

171,

172]. This may lead to avoidance of gross (e.g. whole joint or limb) movements or activities like walking, bending, or lifting [

41,

42,

173].

Conscious awareness, however, also allows individuals to countermand the avoidance. This has brought forth cognitive therapies that are used to overcome kinesiophobia [

89,

174,

175,

176], allowing patients to engage in targeted exercises or activities.

Mw, on the other hand, is subclinical and unconscious. Patients who are only aware of the pain, stiffness, and/or decreased range of motion are often surprised at the number of muscles that test weak, when first tested. Normally, humans are only able to choose the goal of a movement and the trajectory of our limbs as they move toward that goal. We cannot choose the order, timing and relative force of each muscle. That said, EMG biofeedback, which allows an individual to become conscious of the activity of a given muscle, has shown some promise in treatment of AMI [

177,

178].

Muscle and joint imbalances brought about by unresolved Mw could contribute to the development and maintenance of kinesiophobia. Rather than just a simple fear of pain, the ankle instability that accompanies peroneal weakness, for instance, presents an actual increased risk of injury. This may fuel an unconscious but essentially rational distrust of reliance on the ankle.

Because most literature is unaware of methods that restore function to inhibited muscles, this possibility has been overlooked. In my own clinical experience, kinesiophobia is often reduced or eliminated after restoring muscle function, though some patients may still need encouragement to resume activity.

3.7. Functional Weakness, Mw and Predictive Processing

A potentially related movement disorder is called functional weakness (FW). FW is often classified as a variety of "functional motor disorder" (FMD) or "functional neurologic disorder" (FND). FW denotes clinical weakness: observable paresis or (rarely) complete paralysis in a particular limb or region of the body that may present as the chief complaint of the patient in the absence of organic causes [

179]. Historically, FW has been called a conversion disorder, meaning a somatic or visceral expression of unconscious psychogenic stress [

180].

Regarding FMD or FW, several authors have discussed overlapping "sense of agency" and "intentional binding" theories. These describe a decreased capacity of individuals to experience their motor actions as being self-initiated. Decreased functional connectivity between the right temporo-parietal junction (TPJ) and bilateral sensorimotor regions has been noted in patients with FMD. The TPJ is thought to compare actual external events with internal predictions of movements, allowing for a feeling of self-agency [

181,

182]. The cerebellum has also been implicated in both movement and self-agency in its role as both a predictor of motor activity, and a comparator of motor outcomes [

183]. Its possible role in FW has apparently not been investigated.

(Interestingly, decreased sense of ownership of the affected limb has also been noted in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) a condition of chronic pain and dysautonomia affecting one or more limbs. Often developing after mild to moderate trauma, the symptoms are disproportionate to the triggering event [

184,

185].)

FW can also be expressed as a PP model in which hyper-precise predictions of weakness or failure of movement override sensory input of efficacy. This mismatch between intention and perception may create the sense that movements are not under voluntary control. Kozlowska (2015) argues that two innate evolutionary defenses — the freeze response and appeasement behaviors — may be involved in some conditions. Freeze responses inhibit muscles, and appeasement defensive responses may manifest as feigned injury or immobility. These defenses, singly or in combination, engaged in response to adverse childhood experiences, may become predicted responses to pain or trauma. Musculoskeletal conditions or injuries are a frequent precursor to FW.

Overly certain generative models predicting weakness may override contradictory proprioceptive or interoceptive sensory evidence of actual muscular efficacy. Bennett compares this to phantom limb syndrome, in which the brain predicts that an amputated limb is still present, leading to sensations attributed to the absent limb. In FW, the prediction may be opposite, predicting that the limb is absent or at least ‘not my limb’. [

186]

Like the fear of movement in kinesiophobia, the lack of agency in FW could be caused or reinforced by Mw. With the unconscious awareness that muscles will not fully respond to intentions to contract, an individual’s sense of agency may be diminished.

4. Reinforcement Learning: The Second Theoretical Framework of Mw

While predictive processing accounts for the immediate suppression of maladaptive movements based on expected outcomes, reinforcement learning frameworks — including both classical (Pavlovian) and operant (instrumental) conditioning — may explain the longer-term persistence of these patterns.

Reinforcement learning (RL) describes how temporally linked events become associated, forming persistent behavioral patterns [

187,

188,

189]. The neural remodeling underlying associative learning, Hebbian plasticity, is often stated as "neurons that fire together wire together" [

190]. Thus, “neuroplasticity” is sometimes used as a non-specific synonym for associative learning. While predictive processing explains how sensory expectations shape motor suppression, RL may account for how these patterns persist through conditioning mechanisms. Given its role in motor learning and sensory prediction, the cerebellum may play a key role in this process.

In classical conditioning, a neutral sensory input (e.g. a bell) repeatedly temporally paired with an unconditioned stimulus (US; e.g. a puff of air in the eye that normally causes a blink) is called a conditioned stimulus (CS), once the pairing is complete. Thereafter, the CS (bell) elicits the response caused by the US (blink). [

191,

192]

4.1. How the Cerebellum Predicts Danger and Suppresses Movement

Although much of the research on muscle inhibition focuses on the motor cortex, emerging evidence suggests that the cerebellum is integral to muscular responses we are examining here.

Operating completely outside of conscious awareness [

193] the cerebellum is involved in multiple levels of motor processing, including development and expression of classical and operant conditioning [

194,

195], and the adaptation of movements based on prediction [

195]. Research suggests that these properties are part of the acquisition of and responses to memories leading to PTSD [

196,

197,

198], but also, we propose, mPTSD.

The cerebellum plays a crucial role in online (real-time) motor control and error correction. It fine-tunes ongoing movements by comparing predicted and actual sensory feedback, helping to adapt motor output. In motor control theories, in response to the intent to move, the motor cortices establish a motor plan. A copy of this plan (the "efference copy") is sent to the cerebellum, which predicts the sensory consequences of the proposed movement — proprioceptive feedback, tactile input, expected joint angles, forces, etc. This is called the forward model [

199,

200].

If a proposed motor plan has previously resulted in nociceptive prediction errors — tissue damage or pain occurred when a similar motor plan was enacted — the cerebellum may identify it as potentially threatening and suppress or modify it prior to execution. This suppression serves two functions: immediate protection and long-term learning. The latter involves updating internal models through cerebellar-based associative learning [

200,

205,

206]. Importantly, pain without tissue damage can also serve as a salient signal sufficient to drive this form of learning [

169,

207]. The revised motor plan may be returned to the motor cortex via cerebello-thalamocortical circuits [

199,

201,

202,

203,

204] updating long-term learning in the motor cortex as well.

These cerebellar predictive mechanisms extend beyond individual movement plans to broader defensive responses, including freeze reactions. Freeze responses, enacted in response to threats, trigger widespread temporary inhibition of muscles. [

135,

209] Typically processed unconsciously, transient nociceptive stimuli lead to both immediate and longer-term inhibition of the motor cortex. Inhibition, induced by short-term nociceptive stimuli to muscles, can persist for hours after the stimulus is removed. [

23].

Threat recognition may begin in the amygdala, which is closely connected to the periaqueductal grey (PAG) which mediates behavioral responses to threat (e.g. fight-flight-freeze). Research indicates that the cerebellum, in conjunction with the PAG, plays an important role in coordinating physiological responses to threat including blood pressure and heart rate [

210]. Co-operating with the PAG, both conditioned and innate fear-evoked freeze behavior are moderated by cerebellar connections to the spinal cord [

208]. As will be discussed on in

Section 6.2, these responses may be observed with MMT [

103,

211,

212].

Applying classical conditioning terminology more specifically to muscle inhibition, nociception and pain may act as unconditioned stimuli (US), triggering a conditioned response (CR) of motor inhibition. The conditioned stimulus (CS) may be any contemporaneously occurring sensory stimulus, including proprioceptive signals from an injured joint (aligning with AMI theory), other sensory inputs coinciding with the original nociceptive event, or even muscle spindle activity from an inhibited muscle itself [

213,

214].

Activation of the CS by movements may cause the cerebellum to predict an adverse sensory consequence, leading to avoidance of movements that might trigger the CS, which previously was a neutral stimulus. In other words, because of the prediction that they will lead to pain, cerebellar processes may lead to avoidance of harmless movements.

4.2. Implications of Maladaptive Motor Plasticity for Rehabilitation.

In theories of central pain sensitization, movements that are predicted to cause pain based on prior experience may generate pain signals even without nociceptive input. We propose that this maladaptive learning extends to motor function as well: harmless movements (or contraction of muscles that enable those movements) may themselves be inhibited. This motor suppression renders key movements unavailable, necessitating development of alternative motor strategies, though these require time to develop and learn.

Given its roles in nociception and somatotopic connections with individual body area [

205,

215,

216], links to immune function and inflammation [

217], and hypothalamic connectivity [

218], the cerebellum may also modulate local inflammatory responses. This speculative connection is supported by observations we report on later.

This may define the process typically called rehabilitation as the development of new compensatory patterns that allow avoidance of pain/trauma associated muscles. Dedicated rehabilitative practices may speed up the gain of function, and perhaps allow the replacements to be more effective, but even the best compensations are likely to be less stable and efficient than fully integrated motor patterns.

4.3. Freeze Responses and Passive Learning: Why Muscles Shut Down After Pain

While most forms of learning require repetition, passive avoidance learning — the suspension of motor activity in response to a perceived threat — can be established in a single trial [

219,

220]. In a common example, a young child, burned when they touch a hot stove, may thereafter, without additional experiences, avoid touching the stove again. This difference arises in part because avoidance — suspension of action—is simpler than active responses, which require coordinated execution.

By default, the freeze or immobility response, which inhibits muscular action, is the first response to threats that do not induce immediate active protective reactions [

135,

209] like inherent defensive and withdrawal movements [

45,

46,

47].

The freeze response is differentiated from a response sometimes called “tonic immobility”, “playing dead” or a “fright” response, which may ensue when fighting or fleeing are not possible [

135,

221].

In this model, Mw could represent an associatively learned freeze response [

222,

223]. Although freeze responses are generally described as systemic (inhibiting all muscles), a freeze response initiated during preparation for a particular movement may focus on inhibiting the muscles active in that movement [

135,

209].

Again, the inhibition of peroneus muscles in ankle inversion injuries provides a possible example. If the ankle is rapidly inverting, it may be a biologically sound decision to inhibit lateral ankle muscles that would, due to spindle activation if nothing else, be likely to strongly contract, potentially leading to mechanical injury in those muscles. This inhibition, acquired from a single painful event, may persist as a conditioned response [

169].

4.4. Why Muscle Inhibition Persists: How New Movement Patterns Are Learned

In RL theory, when a CS is repeatedly presented without the US, the CR gradually weakens and eventually extinguishes. For instance, if the bell (CS, from our earlier example) is repeatedly presented, (causing a blink, CR) without at least occasionally reinforcing the learning with a puff of air to the eye (US) — eventually the bell will not cause the blink. The conditioning is then said to be extinct. Extinction does not mean the original association is erased. Instead, it is the creation of a new memory (bell ≠ impending air puff) that overlays and suppresses the original CR [

188,

224].

In Mw, extinction might be expected to occur as part of normal recovery, as movements become pain-free. Several factors may prevent this from occurring. The RL model of Mw argues that inhibition of muscles used to perform particular movements is the result of muscle-pain/trauma associations. As suggested earlier, these associations may first be encoded in the cerebellum, which then predicts adverse outcomes if these movements, or the muscles which cause them, are used.

The pain that may come from continuing attempts to use these muscles, whether it is from warnings of potential injury or actual tissue damage, leads to the development of new motor synergies that omit or minimize the use of pain/trauma associated muscles. New synergies may develop through operant (instrumental) learning, the gain of new motor skills through reward-based trial and error processes [

104,

225]. The cerebellum, which is involved in generating and testing predictions about movement, plays a major role in operant learning of motor patterns [

104,

226,

227].

Developed with practice in a second stage of learning, these new synergies replace the synergies that utilized pain/trauma-associated muscles. [

104] Two-stage processes are well documented in avoidance learning, contributing to the persistence of conditions such as agoraphobia and anxiety disorders [

228,

229,

230]. The second stage provides reinforcement with a reward; the reward of avoiding the use of muscles associated with pain or trauma. This distinction between extinction and erasure helps explain why traditional exposure therapies may not permanently resolve Mw, while reconsolidation-based approaches might.

Possibly analogous to the learning-induced inhibition proposed here, the activity of individual muscles can be modified through operant conditioning protocols in both humans and animals. When biofeedback makes muscle activity consciously accessible, subjects can learn to reduce contractile output in response to reward. This learning has been shown to depend on the cerebellum for both acquisition and maintenance. [

231,

232,

233]

5. Experimental Evidence for mPTSD and Its Treatment Principles

In addition to introducing the concept of mPTSD, Weissfeld (2021) provides evidence for the role of maladaptive learning in Mw. The study employed a therapy derived from Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), an accepted treatment for PTSD [

234,

235]. This preliminary evidence suggests that Mw behaves like other conditioned responses, supporting an overlap between psychological and motor learning.

In the experiment, generally healthy individuals without major musculoskeletal complaints were selected. An experienced muscle testing practitioner tested muscles in areas of their choosing, documenting all muscles that tested weak. One at a time, the weak muscles were retested, followed immediately by fifteen seconds of bilateral alternating (side-to-side) eye movements performed by the participant, who followed the examiner's finger movements with their eyes. The muscle was again tested immediately after the procedure. The eye movement procedure employed in this study is based on established EMDR protocols, which have been extensively studied and shown to have a favorable safety profile across numerous clinical populations [

236,

237].

Following the eye movements, 91% of weak muscles tested as normal. When retested an average of 15 days later, over 84% remained normal. In some cases, multiple muscles were normalized following a single application of the eye movements, suggesting that muscle weakness may occur in coordinated patterns. In a crossover control group with 42 weak muscles tested, 88% remained weak over a similar time period. When treated, these muscles responded with similar outcomes.

The study included a case report of a patient who, 15 years prior, had suffered a skiing accident resulting in an ACL tear and other ligament damage. While the surgical repair was functionally successful, some minor pain remained. MMT examination showed multiple subclinical muscle weaknesses persisted in the knee and ankle, as would be expected. The weak muscles were corrected using the eye movement protocol, and one month later, those muscles remained normal, with elimination of pain.

5.1. Disruption of Memory Reconsolidation as a Treatment Mechanism

Memory reconsolidation refers to the process by which previously consolidated memories return to a labile (changeable) and unstable state when reactivated. They must be restabilized — consolidated again — to persist, a process taking up to 6 hours to complete. This labile period is known as the reconsolidation window [

163,

238,

239]. During this window, reactivated memories can be modified by new information. If the consolidation process itself is disrupted, the memory might be eliminated (apparently erased). [

162,

163].

In the context of mPTSD, muscle testing may activate the associative pain or trauma memory, or the motor memory associated with inhibition. Eye movements (or potentially, other interventions) may then disrupt the reconsolidation of this memory.

EMDR has been suggested to operate through several potential mechanisms. Bilateral eye movements may tax working memory resources, potentially interfering with reconsolidation processes [

240]. Alternating bilateral stimulation may enhance communication between cerebral hemispheres, facilitating integration of emotional and sensorimotor information [

241]. Additionally, eye movements may trigger an investigatory reflex that temporarily overrides the freeze response associated with muscle inhibition [

242].

Within predictive processing models, these interventions may create prediction errors — mismatches between expected and actual sensory input during movement [

243,

244]. These prediction errors challenge the brain's maladaptive predictions, potentially disrupting the reconsolidation of traumatic motor memories. This may effectively erase the associative memories that hold predictions of pain and trauma [

162,

163,

245], allowing pre-trauma functional motor patterns to resume.

We propose that AK-related therapies that normalize muscle function may operate through similar mechanisms to the eye-movements — activating maladaptive motor memories with the muscle test before correction is done and then providing novel sensory inputs that disrupt their reconsolidation. Each displays what seems to be the hallmark of this kind of correction by reconsolidation disruption: immediate normalization of weak muscles after the therapy is applied.

Part II: MMT as a Neuropsychological Test

6. Adaptive Force and Its Relationship to Motor Control

The concept of adaptive force (AF) offers a crucial principle for understanding the mechanisms underlying Mw. First introduced by researchers at Universität Potsdam [

246] and further examined over a number of studies [

103,

247,

248,

249], adaptive force has been defined as "the neuromuscular capacity to adapt to external loads during holding [isometric] muscle actions... similar to motions in real life and sports" ([

250] p. 1).

AF is a capacity that arises from properties of ‘motor prediction, planning, and control’ (motorPPC), a finer specification of what is usually referred to as motor control. It is assessed through the capacity of a muscle to maintain an isometric position in response to an externally applied force, reflecting the CNS' ability to predict and adapt to changing force demands [

251]. This describes the MMT.

Bittmann ([

251] pp. 22–23) emphasizes that during MMT, "the aim is not to test the maximal strength of the patient or to 'demonstrate' that the patient is not able to resist the external force. The aim is to assess if the adaptation capacity of the neuromuscular system functions in a normal way." In the context of the break test, this reframes muscle weakness as a motor control prediction failure rather than a force production deficit, a clue to why traditional strengthening approaches may yield suboptimal results. The break test evaluates the integrity of the motorPPC system's ability to predict and adapt to incoming force.

As such Mw can be conceptualized as the failure of adaptive force — an inability to maintain isometric holding against incoming force. Adaptive force is a binary quality; either the muscle successfully adapts or it doesn't.

Coinciding with physiological oscillations in the cerebellum [

252,

253,

254], oscillations of about 10 Hz are seen in normal muscle responses during MMT [

211,

255,

256]. These oscillations may represent periodic updates in cerebellar prediction updating that characterize normal motor control. Motor oscillations are reduced in both individuals with PTSD [

257] and in the responses of weak muscles, as they are being tested with MMT [

211,

251], another overlap between PTSD and mPTSD. The presence or absence of appropriate oscillatory activity in muscles is a primary indication that weakness manifests as a binary; muscle responses are either normal or not, without gradations.

6.1. When Does the Muscle Break? The Unengaged Controversy.

As mentioned earlier, the break test is the most commonly performed MMT test. When we examine its objective phenomenology through FM/T graphs, we discover crucial insights that put into question common ideas about muscle testing. Traditionally, break tests are performed without the use of instruments such as a dynamometer (force gauge). In the break test, the examiner ramps up force against the subject's isometrically contracting muscle to a level of force judged by the examiner to represent “strength that is adequate for ordinary functional activities.” ([

155] p.22). This is a submaximal test, not an attempt to determine MVC, the maximum force the muscle can resist.

Originally developed in the 1910s to assess patients with poliomyelitis, MMT protocols focused on detecting more severe weakness, not the subtle motor control dysfunctions that may be critical in patients without identifiable organic disease or anatomical pathology. [

155,

156]

Some studies [

258], and practitioners of AK [

35,

259], use MMT to identify the presence of weakness; they do not attempt to determine gradations of force. This essentially makes the test binary, and seems to coincide with an adage echoed by a number of authors: ‘when the muscle breaks (i.e., when limb moves, and the muscle is exhibiting eccentric action), the test is over’ [

256,

260,

261,

262,

263].

Despite the above assertion, several of those authors declare that force produced during eccentric action is part of the test [

260,

263]. Eccentric action is known to resist more force than either isometric or concentric action. This apparent contradiction is puzzling, until we realize that “weak” muscles actually break twice. This can only be observed by simultaneously tracing movement as well as force. At the time of these authors’ declarations, the requisite research did not exist. FM/T graphs reveal the objective phenomenology of muscle responses using MMT.

The earliest clearly graphed FM/T analyses we could find were performed in 2000 and 2015 [

211,

264], but the preponderance of available data comes from the Universität Potsdam researchers mentioned in the previous section. Unfortunately, these findings have not found their way into most literature.

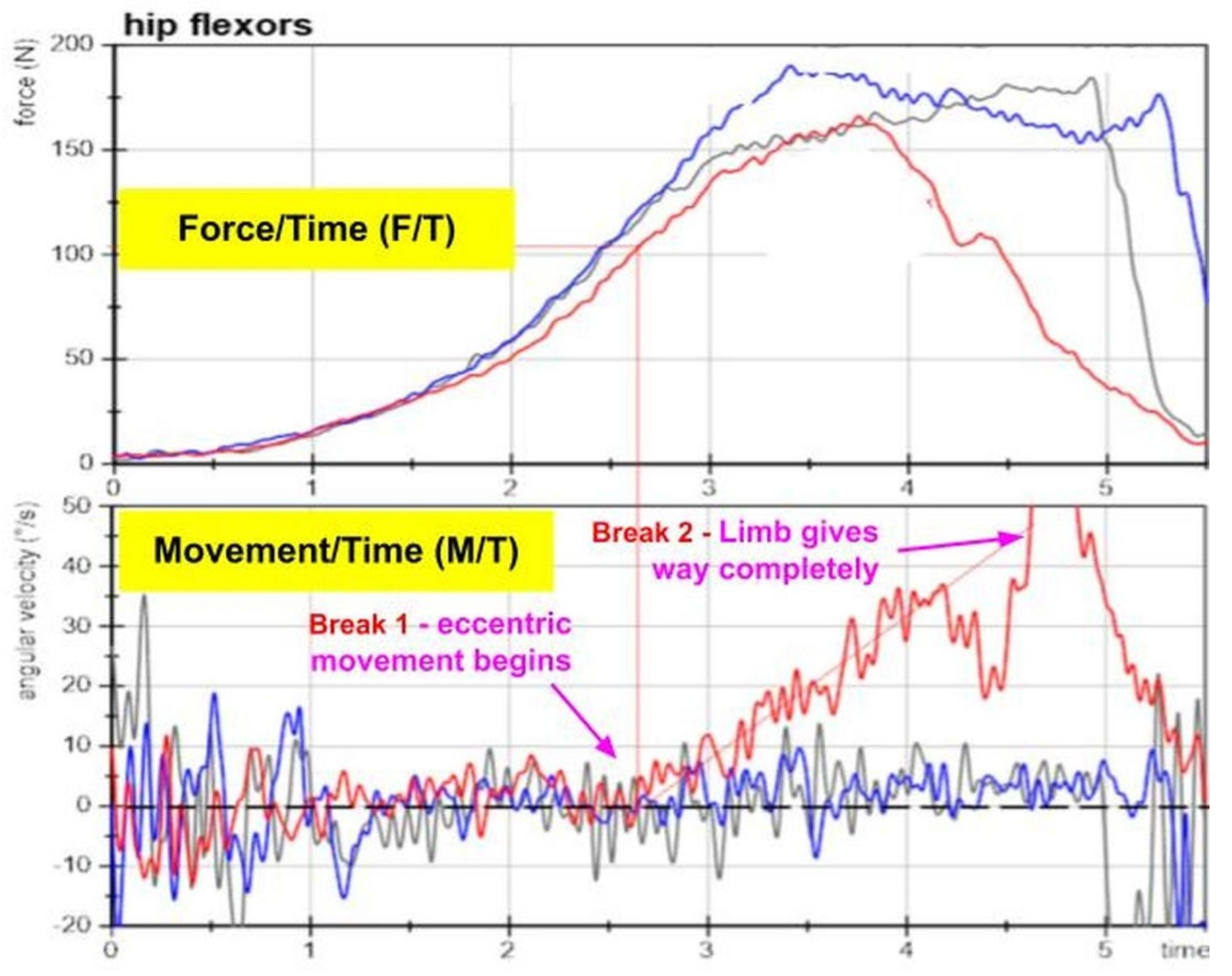

Figure 2, (from Schaefer, (2022)), shows the phenomena of transient change in normal hip flexors tested in the presence of various mental stimuli. We have altered the original to add the markings of Break 1 and Break 2, and removed descriptive text that is beyond our scope to cover.

The top box indicates F/T. The bottom box indicates simultaneous M/T. The different colored tracings show the response to the presence of various forms of mental imagery. The gray tracing is the control (no imagery) and the blue tracing the response to pleasant imagery, which has little apparent effect on the muscle test. The red tracing is the response to unpleasant imagery, which “weakens” the muscle.

Looking at movement (bottom box), we notice that:

All tracings in the bottom (movement) box show periodic oscillations — small up and down movements — but the blue and grey tracings are more regular than the red tracing.

The blue and grey lines (neutral and positive imagery) maintain a flat trajectory, indicating isometric activity.

Beginning at about 2.75 seconds, the red line (unpleasant imagery) begins to ascend. This represents the onset of eccentric movement. We call this Break 1.

Between 4 and 5 seconds, more rapid movement temporarily brings the red line off the chart, as the limb completely gives way. We call this Break 2.

The blue and grey tracings do not break at all.

If MMT outcomes are based on the absence or presence of an isometric plateau, the test is essentially binary, and that binary outcome can be discerned at Break 1 based on movement; it is not necessary to take the test all the way to Break 2.

Combining that with force tracings (top box), we observe that:

The peak force of the red tracing is almost equal to that of the grey and blue tracings.

The peak force of the grey and blue tracings is roughly sustained; peak force of the red tracing is more of a spike.

The force of resistance of the red tracing continues to increase after the onset of eccentric movement.

Studies have not questioned if clinicians take Break 1 Break 2 to be the end of the test. Based on the physiology of eccentric resistance, taken in the context of adaptive force, we believe that tests of “weak” muscles should be concluded at Break 1, for the following reasons:

Eccentric resistance (force) is not primarily produced by active contraction. Instead, as the muscle is eccentrically lengthening, like a stretching rubber band, elastic elements of the muscle and tendon absorb the incoming force [

265,

266]. Moreover, the spinal reflex response to muscle spindle stretch as the muscle lengthens adds activation to the muscle independent of incoming motor commands (or predictions). [

267]. If chronic muscle weakness is due to motor control deficits that limit active contraction, as we have posited, the force produced by passive or reflex functions is moot.

Hand-held dynamometry (HHD) is often clinically used to detect the peak force (MVC) produced by a muscle using MMT. This could result in false negatives if the test continues to Break 2, since peak force of normal and weak muscles can be equivalent before Break 2 is reached.

The concept of adaptive force implies that a muscle’s capacity to adapt is binary.

While

Figure 2 shows a long, slow break test, Caruso and Leisman found that using alternative techniques, “weak” muscles begin to give way milliseconds after the onset of the test, allowing for the binary determination of “normal” or “weak” can be made in .5 s or less. [

264,

268]

For most clinical purposes, we assert that MMT should conclude at the onset of Break 1. These are typical results for FM/T graphs, so this conclusion may be generalized to all MMT break tests performed according to the aforementioned guidelines.

6.2. The Binary Nature of Muscle Function

Analysis of muscle function during break tests reveals binary characteristics. Muscles either maintain an isometric “lock” against increasing force (normal function) or they “unlock”; they fail to maintain position and yield eccentrically (dysfunction). This pattern has been observed in multiple studies [

103,

211,

264,

269].

The binary nature of muscle function in Mw can be understood through established principles of motor control. The Go/No-Go principle shows that motor action is either initiated or inhibited based on specific stimuli [

270]. Stimuli, whether consciously noticed or subliminal, can effectively flip a binary switch affecting the accuracy and speed of motor responses [

172,

271,

272]. Similarly, approach-avoidance and freeze responses are functionally binary, though their outward expressions can be complex and context-dependent [

273,

274].

The binary nature of muscle response is particularly evident when observing muscles before and after exposure to various sensory inputs. Rosner et al. (2015) demonstrated that muscles exhibit this binary response pattern when tested before and after exposure to noxious cutaneous stimuli. Similarly, Schaefer et al. (2022) as seen in

Figure 2, revealed that unpleasant imagery induced the same binary shift from isometric holding to eccentric yielding.

This pattern extends to other sensory modalities including visceral [

82,

84,

275,

276,

277], olfactory [

248,

278], visual [

279], and various cutaneous inputs [

23,

157,

211,

277,

280,

281,

282], as well as emotional stressors including unpleasant imagery [

103] and making counterfactual statements [

212,

283].

This binary response to diverse stimuli suggests that MMT functions beyond its traditional role as a musculoskeletal assessment. In essence, MMT appears to operate as a neuropsychological test. When a stimulus (whether exteroceptive, interoceptive, or cognitive-emotional) receives focus, the immediate binary shift in muscle function reveals whether the CNS interprets that stimulus as a threat. MMT essentially becomes a sensitive detector of the brain's threat assessment processing, with inhibition potentially representing a localized expression of the freeze response. This perspective helps explain why seemingly unrelated stimuli can consistently affect muscle function, beginning to providing a mechanistic explanation some of the more controversial applications of AK [

261].

While this reconceptualization of MMT requires further empirical validation, it offers a coherent explanation for the observed phenomena and may bridge the gap between psychological processing and motor output in clinical assessment. Even when evaluating musculoskeletal dysfunction, the psychological roots of Mw suggest that MMT fundamentally operates as a neuropsychological evaluation.

6.3. The Binary Nature of Muscle Dysfunction

Having established the binary nature of muscle function, we now examine the clinical evidence supporting this model. Interventions addressing Mw or AMI consistently produce an immediate binary shift from dysfunction to normal function, rather than gradual improvement. This binary response is observed in two distinct treatment categories: those that temporarily suspend AMI, and those that produce lasting normalization of Mw (putatively including AMI).

6.3.1. Temporary Reversal of AMI

Treatments recommended within physical therapy literature successfully but temporarily reverse muscle activation deficits by decreasing afferent output from associated joints. This intervention confirms a binary model of motor control pathology, as muscles transition from inhibited to facilitated states, returning to inhibition when the treatment effect wears off. The temporary alleviation of Mw creates an opportunity for exercise to reduce atrophy. Treatments that may be effective for this include: cryotherapy, transcutaneous neuromuscular stimulation (TENS), transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), and neuromuscular stimulation [

27,

68,

69,

70,

80,

284].

A scoping review of physiotherapy strategies for AMI concluded that “[p]ersistent impairments have been detected despite increases in quadriceps function.” … “Thus, it is probable that the present therapeutic approaches are failing.” ([

80] p. 2611)

Nevertheless, the fact that the weakness can be effectively suspended for a period suggests that its expression is binary in nature.

6.3.2. Applied Kinesiology and Related Systems

The mPTSD hypothesis was inspired by decades of observing muscle corrections through various AK practices.

In 1964, referencing Kendall’s Muscles, Testing and Function, a primary MMT text, Goodheart discovered that weak-testing muscles (which probably could be classified as AMI) might be corrected by certain treatments. He found that each muscle corresponded to a specific set of reflexes, unvarying from patient to patient. Thought to affect lymphatic, vascular, and acupuncture meridian flow, these reflexes, when treated along with spinal manipulation, immediately and persistently normalized muscle function [

81,

82,

83,

84].

While AK encompasses other practices that have been subject to much debate [

261], the easily verified muscle inhibition treatment protocols are widely regarded as fundamental and effective within the AK community. Unfortunately, despite being used by an estimated 1 million health professionals worldwide, [

285] AK muscle treatment protocols have not been sufficiently evaluated to attain an “evidenced-based” designation.

An offshoot of AK, Clinical Kinesiology (CK) and its descendant Advanced Muscle Integration Technique (AMIT®), further developed and refined Goodheart's basic protocol, applying it to 300 bilateral muscles [

286,

287].

AMIT® was used with the National Basketball Association’s Utah Jazz for over 2 decades, beginning in 1979. According to a retrospective analysis of some of that time period, Jazz players missed over 50% fewer games than the rest of the league’s players over the same period. [

288,

289] Further, according to reports of players and team officials, AMIT’s treatments achieved unprecedented results in injury recovery. Team doctor for the Jazz Craig Buhler, the founder of AMIT®, found that when muscles were normalized promptly following mild to moderate sprain/strain injuries, injuries that seemingly would have kept players out for weeks were sometimes resolved on the spot or over the next several days. One surprising result was that expected swelling was often prevented with timely treatment [

288,

289,

290,

291,

292].

This supports the speculation that these treatments are addressing cerebellar internal models, which may also, as earlier suggested promote local swelling. From the PP perspective it also supports the supposition that treatments are altering generative models that hold the belief that the area is damaged. In a self-reinforcing cycle, Mw may (falsely) signal to the brain that the muscles are injured, triggering both swelling and pain warnings when use is attempted.

With recovery evidenced by immediate reductions in pain, decreased local muscle tension, and increased range of motion, those who use these protocols find they almost unfailingly restore normal muscle function on a muscle-by-muscle basis when complicating features like nerve, bone, or joint degeneration or damage are absent. Unfortunately, despite clinical success, these practices lack sufficient validation to gain acceptance as "evidence-based" in the broader research and therapeutic communities.

The immediate, binary nature of these responses further validates our theoretical framework of Mw as a conditioned response rather than a progressive pathology. This binary behavioral pattern mirrors what we see in other conditioned responses that can be eliminated through appropriate interventions targeting memory reconsolidation.

6.4“. High Resolution” Muscle Testing; an Index of Motor Control Dysfunction?

Out of the 300-plus bilateral muscles in the body [

293], classical MMT texts document tests for about 90-100 muscles [

155,

156]. As noted earlier, tests for approximately 300 bilateral muscles were developed by Beardall [

286], and updated by Buhler and Williams [

287]. This high resolution (HR) set typically addresses 20-25 muscles in each major joint or region of the body and twice as many for each shoulder complex. Performing “HR regional testing” on areas of past or present pain, those of us who utilize this system commonly find >30% of muscles testing weak, and sometimes far more.

Although the number of weak muscles may not match the severity of symptoms, HR testing becomes an index of the extent of motor control dysfunction in a region based on the percentage of muscles found weak. If 25 muscles were tested, and 5 were found to be weak, a 20% deficiency is indicated.

While testing for weakness is a reasonable baseline, it does not tell the entire story of muscle facilitation. An apparently “strong” muscle may be ‘over-facilitated’ or ‘hyperreactive’, a condition of phasic muscle action which renders a muscle unresponsive to stimuli that should cause it to weaken. One naturally weakening stimulus is manual compression of a muscle’s spindle cells, an action which has the opposite effect of inducing the stretch reflex. If spindle compression is performed on a normal muscle, an immediately subsequent test will find the muscle weak ([

84] pp. 81–83). An over-facilitated muscle will not weaken following spindle compression. Over-facilitation, which may represent compensatory attempts to stabilize joints affected by inhibition of other muscles, is not discussed in most literature.

In my own experience, the correction of inhibited muscles will frequently address those that are over-facilitated. Once this is accomplished, the over-facilitated muscles often test weak on a second pass, suggesting layered compensatory patterns where muscles adopt different roles in each layer. They can then be addressed like other weak muscles.

6.5. Clinical Replication of These Results

The validation of mPTSD hypothesis by Weissfeld (2021) presented a 4-step protocol for restoring function to weak muscles that might be used by researchers attempting to validate the study or clinicians seeking to improve patient outcomes.

Step 1: Scan a subject for weak muscles using MMT according to the criteria set forth in

Section 6.1, and create a list including each one found. These muscles do not all need to cross the same joint, so for instance, one might test ankle, knee, and hip muscles when attempting to address symptoms in any of the areas, though testing can be performed in asymptomatic areas as well. (In order to document symptomatic changes that could accompany muscle corrections, record symptoms and positive orthopedic tests before any testing is done.)

Step 2: Starting from the top of the list, retest and immediately treat each muscle, one at a time using the following procedure: Within 7 seconds of (re)testing each muscle, have the subject follow your index finger from right to left and back with their eyes at about 1 complete cycle per second. Continue for 15 seconds (15 reps). Some weak muscles may have strengthened by the time they are reached on the list; this ‘spontaneous’ recovery should be noted as well.

Step 3: Following Step 2, retest each muscle, noting whether it remains weak or strengthens. When all muscles have been addressed, previously noted symptoms or tests can be repeated, documenting changes.

Step 4: At least 24 hours later, retest all muscles that were originally found to be weak. Also review symptoms and tests from Step 1.

Potentially, testing many weak muscles before treatment is attempted may activate, and thereby more effectively destabilize memories that may be affecting more than one muscle. The therapeutic intervention, in these cases, may be eliminating a larger pattern of muscle weakness.

Over decades of experience, I have found that many different therapies might be substituted for the eye movements. Reflecting “a common principle of change” [

294], other therapies that beneficially alter CNS function, including spinal manipulation [

64] or acupuncture [

295], may produce similar results when applied after testing many muscles. From the perspective of principles of memory reconsolidation, these therapies may be establishing broad neurological states that are contradictory (mismatched) to the states induced by testing muscles unconsciously associated with pain or trauma, a necessary condition of inducing memory change in reconsolidation models [

162,

163,

245].

It can be instructive, and clinically useful, to retest muscles that appeared to be normal on the first pass. If a new pattern of weakness exists after the first round of treatment, it can be assumed to suggest the existence of layered compensatory patterns of weakness. These successive patterns can be addressed using the same process.

In my clinical experience, and that of colleagues who perform HR regional testing, superior results can only be regularly achieved when at least most muscles in a region are functionally restored. A single remaining weak muscle could be the tip of an iceberg of a hidden pattern of adaptation that symptomatically manifests when the individual is under stress.

Although I studied with Beardall (who delineated most of the 300+ muscle tests) in the 1980s, I missed out on courses in which the tests were directly taught. I found them difficult to learn from the manuals alone, so I ended up taking Buhler’s training. References and video or classroom instruction for testing and treating based on Beardall’s and AK principles may be available from ClinicalKinesiology.com [

296] or AMITseminars.com [

297]

7. Summary and Conclusion

The mPTSD Model integrates the clinical observations and theoretical frameworks presented throughout this paper to offer a transformative understanding of muscle weakness, particularly pertaining to non-specific musculoskeletal disorders, but perhaps impacting functional weakness (FW) and kinesiophobia. This theoretical and clinical review has demonstrated 1) how conditioned and predictive learning processes can create chronic maladaptive muscle weakness (Mw); 2) how Mw is clinically discerned by the manual muscle testing (MMT) “break test”; and 3) how maladaptive learning may be eliminated using existing alternative methods and novelly-applied psychotherapeutic methods. In total, this review offers a new clinical paradigm for a long-standing challenge in musculoskeletal care.