1. Muscle Weakness: The Overlooked Pathological Finding

Musculoskeletal conditions affect approximately 1.7 billion people worldwide [

2], with far-reaching consequences. For individuals, pain and reduced function may lead to work, financial, and family hardships, along with diminished well-being and quality of life, and in some cases, opiate addiction [

3]. Employers in the US spend

$353 billion on musculoskeletal care [

4], with productivity losses averaging

$3,105 per affected employee annually [

5]. This contributes to an overall economic burden approaching

$1 trillion (5.6% of GDP) [

6]. The incidence is expected to increase as the population ages. Pain is a primary complaint in many musculoskeletal disorders.

1.1. Non-specific musculoskeletal disorders

An estimated 75-95% of patients with musculoskeletal complaints have non-specific musculoskeletal disorders (nsMSDs) — conditions lacking an “organic” lesion: a specific disease, pathology, or structural abnormality that could induce pain [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. This establishes what O’Sullivan calls "a diagnostic and management vacuum," resulting in treatment of signs and symptoms "without consideration for the underlying basis or mechanism for the pain disorder" ([

9] p. 243).

Although ‘non-specific’ most often refers to idiopathic low back pain [

3,

6,

7,

10,

11,

12], the designation is also applied to other areas, including the temporomandibular joint, neck [

2], knees [

8], shoulders or arms [

5], but it can be applied to any condition in which no organic cause is found.

1.2. Motor Control, Muscle Weakness and Non-Specific Conditions

Over the last 30 years, aberrant motor control has been discussed as a factor in nsMSDs, whether active or in remission [

9,

11,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Motor control refers to the nervous system’s coordination of muscle activation to produce purposeful movement and maintain posture. Clinically, muscle weakness, an indicator of aberrant motor control, is discussed as a factor in a wide range of non-specific conditions. These include non-specific chronic low back pain [

9,

18,

24], whiplash-associated disorders [

25], knee pain syndromes [

23,

26,

27], ankle instability [

28,

29], plantar fasciitis [

30], headaches [

31], and various "overuse" injuries [

32,

33]. Muscle weakness impairs rehabilitation outcomes [

34,

35,

36], but long-term restoration remains a challenge, as discussed in later sections.

Once organic causes of weakness — e.g., stroke, inflammatory myopathies, nerve impingement, or disuse atrophy — have been ruled out, a healthy muscle’s ability to contract depends on the activation level of its alpha motor neuron (αMN) pool. When contraction is insufficient, it reflects a diminished ‘central integrative state’ of the αMN pool; the net effect of its excitatory and inhibitory inputs [

37,

38,

39].

In physical therapy and orthopedic literature, the finding of weakness in otherwise healthy muscles is often called “arthrogenic muscle inhibition” (AMI). AMI theories posit that inhibition begins as a reflex mediated by spinal inhibitory interneurons. In response to excess mechanoreceptor activation in joints during or following injury, these interneurons presynaptically inhibit αMNs [

40,

41,

42] by moving the central integrative state of the αMNs further away from their firing threshold. AMI researchers have suggested that inhibition is a mechanism that protects the affected region from further injury. More recently, studies outlining supraspinal changes, particularly in the motor cortex, have described altered motor control associated with AMI. In seeming contradiction, studies have found that the motor cortex is more excitable when muscle inhibition is present. This suggests that the motor control system has to do more work to stabilize the region when muscles are inhibited [

27,

35,

43], but it is not evidence of supraspinal involvement in AMI [

44].

Most reporting on AMI has emerged from studies of knee pain and injury, particularly following anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture and reconstruction, with quadriceps inhibition garnering the most attention [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53].

Several decades of experiments by Wolpaw and colleagues at the University at Albany have demonstrated that behavioral adaptations, the result of operant (instrumental) conditioning, can change the function of muscles [

54]. Using Hoffman (H)-reflex biofeedback, they found that a functional analog of AMI — downregulation of αMNs in humans and animals induced by operant conditioning — alters spinal and αMN morphology and function, but is ultimately sustained by cerebellar plasticity [

55,

56,

57,

58,

59]. The H-reflex measures motoneuron pool excitability and is analogous to the stretch reflex. H-reflex biofeedback electrically evokes this monosynaptic spinal reflex and provides visual or auditory feedback that allows subjects to monitor and potentially modulate reflex strength. Insufficient H-reflex amplitude is a common finding in muscles affected by AMI [

60].

Assuming that the participant is exerting full effort, muscle activation deficits, organic or not, can be caused by functional alterations occurring anywhere in a pathway from the sensorimotor cortices and cerebellum to the motor neuron or muscle itself. This includes the possibility of altered function of gamma motor neurons [

61,

62], which modulate the force of contraction in active muscles. Pain is known to trigger diverse alterations in movement patterns, including inhibition of muscles [

17,

24,

63,

64,

65].

1.3. Foundations of this Review

To the clinician discovering a weak muscle using manual muscle testing (MMT) or MMT with handheld dynamometry (HHD) on patients without organic conditions, the mechanisms that underlie the diminished contraction are a black box. ‘Idiopathic weakness’, would be an appropriate term for persistently weak muscles in these patients, but we will use the term “non-organic weakness” (NOw). Weakness that might be called AMI is a form of NOw. Unless otherwise specified, throughout this document, any mention of muscle weakness, its treatment, or MMT refers to weakness without a determinable organic cause.

In the relative absence of other theories accounting for the persistence of NOw, this may prove to be more than a designation of convenience. The hypotheses presented in this paper suggest that it represents a distinct pathological entity, characterized by maladaptive neuroplastic changes in motor control. A working definition of NOw is muscle weakness resulting from disturbances of motor control caused by maladaptive learning (neuroplasticity). As shown by AMI studies, affected muscles may exhibit deficits on tests including H-reflex and burst superimposition (described later); however, functional motor control deficits are concisely revealed through MMT. Specifically, these deficits are observed during the MMT “break test,” or through objective recordings of force and motion (F/M), alone or traced over time (FM/T) during MMT. Unique among all other muscle evaluations, the break test tracks a muscle’s response to increasing external force, which is dictated by motor control functions. Importantly, the designation also implies the potential for remediation, as these adaptations may be normalized by interventions that putatively alter or eliminate maladaptive motor learning. These corrections represent a potential method for remediation of motor control dysfunction.

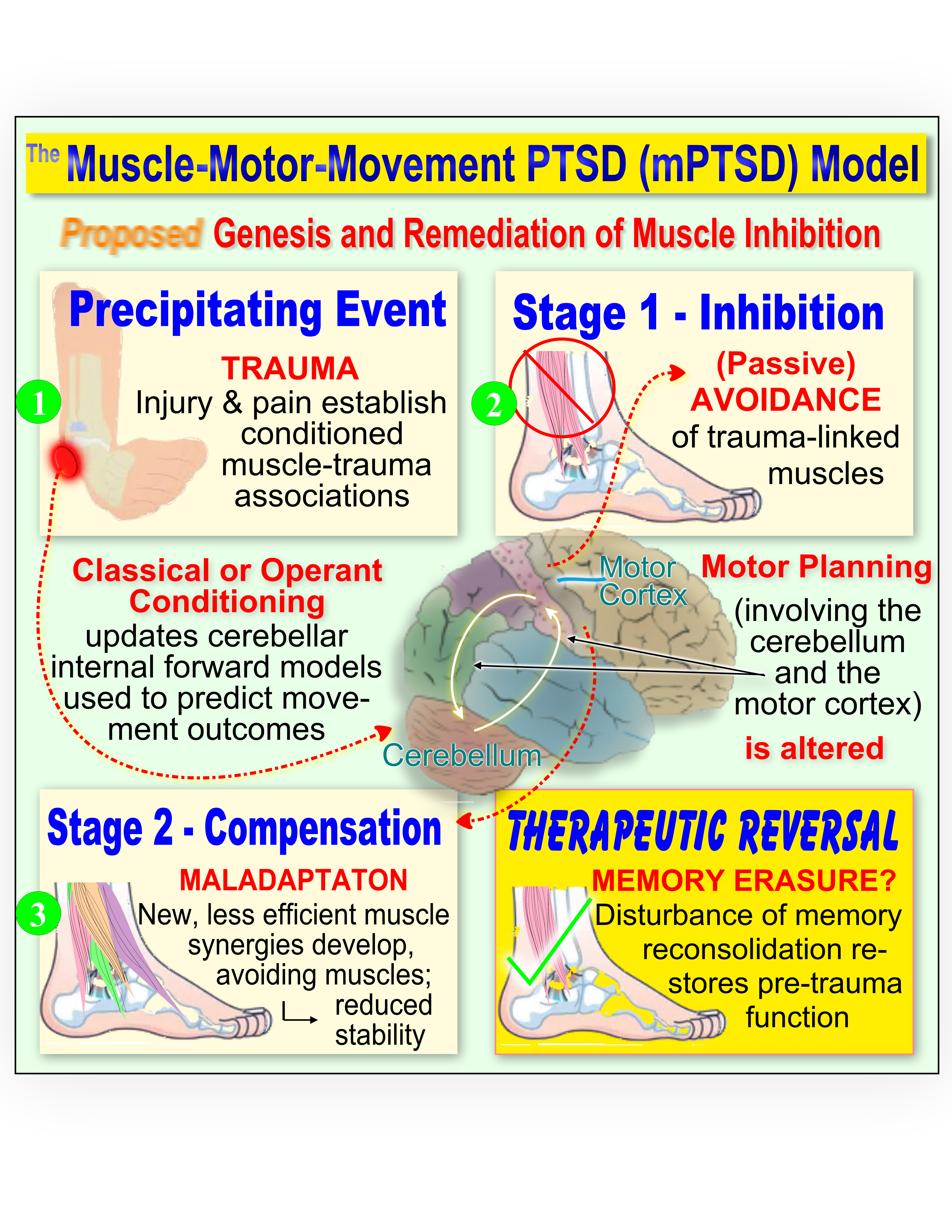

Part I summarizes current knowledge of NOw, its relationship to motor control, and reviews existing treatments. Part II presents objective data that refine methods and interpretations of MMT. Part III expands on the “muscle-motor-movement post-traumatic stress disorder” (mPTSD) model, proposing a hypothetical mechanism for NOw. Part IV suggests clinical applications of these concepts, introducing additional theory grounded in clinical observation. Part V presents conclusions, limitations, and directions for future research.

1.4. The MMT “Break Test”

“Weakness”, applied to an individual muscle tested with MMT, is usually subclinical: patients complain of hamstring pain or tightness for example, not semimembranosus weakness. MMT, as we use the term here, is the “break test” performed without instrumentation. The following description of the break test, the most widely used form of MMT, essentially coincides with narrative descriptions from Kendall’s

Muscles, Testing, and Function. Now in its 6th edition, “Kendall” is one of two classic textbooks of MMT [

66]. The other, Daniels & Worthingham’s, emphasizes a different methodology not addressed here.

The MMT break test evaluates a muscle’s ability to maintain an isometric (unmoving) plateau under gradually increasing force. In this test, the examiner instructs the participant to hold the limb steady while resisting the examiner’s ramping force. As stated by several authors, once the muscle “breaks” — that is, when the limb begins to move — the test is considered complete and the muscle is classified as weak [

67,

68,

69,

70,

71].

Objective recordings of FM/T, however, reveal two distinct breaks. In our terminology, “Break 1” marks the onset of eccentric contraction, where the muscle lengthens while still resisting. “Break 2” represents complete failure, when resistance force falls to zero and the limb gives way entirely.

Several authors have argued that Break 2, which includes the force produced during eccentric contraction, should be considered part of the test [

67,

71]. HHD, which usually relies on peak force to estimate maximum voluntary (isometric) contraction (MVC), is also likely to capture eccentrically produced force, which exceeds isometric force [

72].

FM/T tracings, combined with current understanding of muscle physiology and mechanisms of weakness, suggest that MMT should generally be concluded at Break 1. With one exception, quality FM/T analyses have only been available since 2015, and their implications have not yet been incorporated into standard knowledge about muscle testing. This issue is examined further in Part II.

1.5. Expanding the Biopsychosocial Model; Mind-Body Treatment for Muscles

A “biopsychosocial model” for nsMSDs, holding that thoughts, emotions, beliefs, and social factors may contribute to non-specific conditions, particularly low back pain [

7,

19,

73,

74], has been gaining support. Similar constructs have been offered for potentially related conditions, including kinesiophobia — fear and avoidance of movement [

75] — and functional weakness (FW) — clinical paresis or paralysis that is considered a subset of functional motor or neurologic disorders [

76].

This review affirms and extends the biopsychosocial model by introducing a motor-specific mechanism through which psychological and sensorimotor experiences may directly alter movement patterns. While most biopsychosocial models focus on conscious beliefs, the mPTSD model highlights non-conscious influences on individual muscle activation and coordination. These include conditioned associations and sensorimotor predictions, responses guided by unconscious information processing [

77,

78,

79].

By integrating motor control and learning theory, this review outlines a new treatment paradigm that aligns with — but extends beyond — current mind-body approaches. Rather than focusing on broad functional activities, however, the mPTSD model focuses on muscle-by muscle testing and interventions.

1.6. Hypotheses and Methods

In the aftermath of musculoskeletal injury or in the presence of pain, the finding of treatment-resistant muscle weakness (NOw as we call it) has puzzled clinicians for centuries [

80,

81]. Guided by a desire to understand the etiology of unexplained weakness and its treatments, this review proposes three hypotheses linking its etiology, diagnosis, and treatment.

1.6.1. Hypotheses of Etiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of mPTSD

Hodges and Moseley (2003) posited that anticipation of pain leads to delayed muscle activation, and that this finding represents a change in motor planning, a product of fear-avoidance learning [

82]. Neige et al. (2018) further connected this effect to conditioned learning, wherein learned associations between pain and particular movements would lead to adaptations in movement patterns. These adaptations may delay or avoid particular movements. Although protective movement strategies may initially reduce pain, they can have adverse long-term effects and contribute to the development of chronic pain [

83,

84,

85].

A mPTSD hypothesis was preliminarily supported in a 2021 proof-of-concept study, which showed that muscle weakness (NOw) could be immediately reversed by side-to-side eye movements — a key element in the trauma therapy Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) [

86]. This review expands on the mPTSD Model, exploring maladaptive learning as a potential mechanism underlying NOw. We also examine how recent theoretical and phenomenological insights into MMT may improve the identification of affected muscles, and consider potential mechanisms by which certain therapies may resolve these maladaptive motor adaptations. These themes essentially combine models or theories from three sources:

Two-stage maladaptive learning, a novel hypothesis presented here for the first time. In stage 1, adaptive learning associates the use of specific muscles with prior trauma (e.g., pain, stress, or injury). These associations are encoded into internal models (mental representations of how the body moves and responds) used during predictive motor planning [

87,

88,

89]. In stage 2, compensatory strategies shift the load to unaffected muscles. These inefficient patterns persist, preventing re-integration of inhibited muscles. (See Part III.)

“Adaptive force” as an assessment of motor control, a pre-existing theory. At the level of individual muscles, the inability to sustain isometric holding — representing the failure of the muscle to adapt to changing pressure — is the key indicator of a motor control deficit, not reduced force. Failure to recognize this distinction may lead to false negatives with peak-force dynamometry. (

Section 3.4).

Maladaptive memories can be eliminated, a pre-existing theory. Building on memory reconsolidation theories, maladaptive motor memories — here, memories sustaining NOw — can be erased once reactivated. Therapies that reverse muscle inhibition may do so by engaging these reconsolidation mechanisms. (

Section 7.1.)

1.6.2. Methodology: Non-Systematic Review of Existing Literature

This non-systematic, integrative review draws from musculoskeletal medicine, neuroscience, psychology, physiology, motor control, and trauma research, synthesizing concepts rarely combined. It is, in part, an effort to understand the clinical outcomes presented in Appendix A — outcomes that would be considered improbable by conventional thinking — and to share long-observed phenomena in a form accessible to clinicians outside alternative practice spheres.

This format contains several limitations. First, the lack of formal inclusion and exclusion criteria introduces potential selection bias [

90]. Second, the transdisciplinary scope, while a strength in exploring novel models, makes it difficult to establish uniform standards of evidence across domains [

91]. Third, some proposed interpretations — particularly involving theories of adaptive force, predictive processing and reinforcement learning — rely on theoretical extrapolations rather than empirical validation. This necessitates further research. Finally, given the controversial nature of some source material, including case reports and observational data, conclusions are best viewed as provisional and hypothesis-generating rather than confirmatory.

Integrating data from diverse domains, some of which are themselves not empirically validated, this review blends established findings with hypothesis-driven interpretations. While every effort has been made to distinguish speculation from evidence, readers are encouraged to regard the proposed mechanisms as provisional models rather than definitive conclusions.

2. Current Knowledge and Practices

Before developing these concepts, we review the current baseline of knowledge and practice regarding the evaluation and treatment of aberrant motor control and muscle weakness.

Given the lack of clinical criteria and differential guidelines, distinguishing AMI from other potential causes of NOw is not currently possible, but alternative theories are few. Reports of resolution of weakness via treatment of trigger points [

92,

93], spinal manipulation [

94,

95,

96,

97,

98], reflex treatments [

39,

99,

100] and therapeutic eye movements and other dissimilar therapies imply a mechanism that has yet to be considered. Speculation on that mechanism is a central thrust of this review, covered in Part III.

2.1. Motor Priming, Learned Responses, MMT Outcomes, and Defensive Action

Two essentially opposing theories describe motor responses to pain and nociception. The “pain adaptation model” holds that inhibition is the primary response [

83,

101,

102], while the ‘vicious cycle theory’ holds that pain increases muscle activity [

2,

103,

104,

105]. Paul Hodges, a primary researcher of motor control in the context of musculoskeletal disorders, suggests instead that pain induces a redistribution of muscle activity, varying across tasks, individuals, and contexts [

106]. In

Section 7.6, we amend this view based on clinical observations.

A theory of muscle response supported by clinical observation and experiments is that there are at least three states of muscle facilitation or priming: 1) positively primed (just “primed” in most uses), 2) inhibited or negatively primed, and 3) normally facilitated or unprimed. In cognitive and motor neuroscience, both positive and negative motor priming (the unconscious preparation for motor responses) have been demonstrated in response to preceding stimuli, including subliminal or masked cues. For instance, motor responses can be facilitated (as shown by shorter reaction time and greater excitability) when congruent motor plans or positively valanced sensory inputs are unconsciously pre-activated [

107,

108,

109]. Motor responses are inhibited or negatively primed (showing slower, delayed or reduced excitability) when incongruent plans or negatively valenced sensory inputs are presented [

107,

109,

110].

Though it remains unstudied to our knowledge, delayed activation may be a common denominator in negative motor priming, motor control abnormalities found in musculoskeletal conditions, and MMT outcomes. Delayed activation has been observed in patients with musculoskeletal pain, even in remission [

22,

24,

82,

83,

111]. A related partially supported theory is that muscle weakness found with MMT represents muscles that are delayed in their activation [

112]. When specific MMT technique is used (see

Section 3.7), the failure of a muscle to respond is evident within the first milliseconds of force application [

113]. This generally supports the pain adaptation model.

Supporting the vicious cycle theory, pain and trauma are known to induce specific defensive and withdrawal movements as reactions to the details of the experience. These muscle responses may become habituated or learned as ongoing patterns [

114,

115,

116]. According to Levine (and others, in related explorations), one form of this response may be caused by the inherent impulse to complete unresolved defensive responses during trauma [

117,

118,

119,

120]. This persistent response, which may be equivalent to positive priming, contributes to symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). If this is the case, antagonists of positively primed muscles may be negatively primed — weak, if tested — due to mechanisms of spinal reciprocal inhibition [

121] or supraspinal processes [

122,

123].

In this framing, negatively primed muscles test weak with MMT — unable to form a stable isometric plateau — while unprimed muscles test ‘strong’ or normal. Positive motor priming is more complex to detect. Clinicians identify a phasic state called

over-facilitation, evident only during voluntary contraction (e.g., MMT). Over-facilitated muscles may feel normal when tested but fail to weaken in response to stimuli that should transiently inhibit contraction, such as manual compression of muscle spindles, which in normal muscles produces temporary weakening on immediate retest [

124,

125]; ([

100] pp. 81–83). Clinically, these muscles may sometimes feel rigid from the outset of testing or even express as an aggressive, concentric push against the examiner’s hand, rather than isometric resistance. This can occur in single muscles or, in some cases, systemically, affecting all muscles. Later, we relate MMT outcomes to the “defense cascade,” in which weakness may reflect a freeze response and over-facilitation a second stage, priming for fight or flight [

126,

127,

128]. In

Section 7.5, we suggest a clinical strategy for remediating locally over-facilitated muscles.

2.1.1. Current Treatments for AMI

In the previous section, we noted that various therapies might be successful in reversing NOw. These will be explored in more detail shortly.

Although not a feature of all muscle inhibition ([

92] p. 7), atrophy (hypotrophy) is stated to be a common secondary effect of AMI. Muscles presumed to be affected by AMI often fail in hypertrophic development despite exercise and physiotherapy [

18,

36,

60,

129,

130,

131,

132,

133]. A scoping review of physiotherapy strategies for AMI concluded that “[p]ersistent impairments have been detected despite increases in [muscle] function.” … “Thus, it is probable that the present therapeutic approaches are failing.” ([

134] p. 2611) Exercising while in pain is discouraged by several authors, as it risks training (learning) of abnormal biomechanics which could make the altered function more indelible [

92,

135]. The validity of this assertion may be assessed by testing muscles in previously injured, now asymptomatic regions.

Therapies that block afferent output from joints, including transcutaneous neuromuscular stimulation (TENS), transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), and cryotherapy [

27,

35,

129,

134,

136,

137], can temporarily suspend weakness, enabling effective hypertrophic muscle training [

35,

48,

129,

137,

138]. Even with this therapy, AMI-related neural activation deficits often persist beyond both symptom resolution and functional recovery [

18,

134,

136,

139,

140,

141].

Electromyographic (EMG) biofeedback has shown some promise in the diagnosis and treatment of AMI [

142,

143]. Transforming physiological variables into visual or auditory signals, EMG biofeedback allows patients to learn to more precisely control individual muscles. Richaud et al. describe applying this method with AMI patients, showing how several weeks of therapy can improve or normalize function of both hypertonic and inhibited muscles [

144]. In

Section 6.5, we look at the possible neuroplastic mechanisms involved in this method.

2.2. Effects of Muscle Weakness on the Body

The term ‘muscle weakness’ is used here as may be used in the literature; often without clear etiology or standardized assessment criteria. Muscle weakness negatively affects coordination, stability, and overall function.

Key consequences include:

Altered movement patterns: To avoid inhibited muscles, patients adopt compensatory movements that reduce biomechanical and functional efficiency [

84,

145,

146,

147].

Joint instability: Weak stabilizers compromise joint function and may accelerate degeneration [

51,

148].

Reduced performance: Weakness impairs athletic performance and increases reinjury risk [

149,

150,

151].

Chronicity and recurrence: Unresolved weakness may promote the transition from acute to chronic conditions and increase the risk of recurrence, even in asymptomatic individuals [

85].

Kinetic chain dysfunction: Weakness in one region can disrupt proprioception and stability throughout the body, particularly when it affects the lower extremities [

152,

153].

Persistent pain: Muscle weakness and other motor control alterations are correlated with the presence of pain [

112,

154]. This may create a self-perpetuating loop, with pain and motor control abnormalities reinforcing one another [

11,

17,

82,

106].

Muscles are essential for joint mobility, stability, and shock absorption [

72]. Even in asymptomatic individuals, muscle weakness may contribute to functional impairment [

155,

156], ankle instability [

28,

157], gait disturbance [

49,

158], and osteoarthritis [

148,

159,

160]. Roos et al. (2010) noted that muscle function correlates more closely with joint pain than joint-space narrowing [

160]. Weakness, which may undermine the supportive role of muscles, might be a better predictor of disability than pain and structural findings [

161,

162]. Pain may not reflect actual tissue damage; it may act as a warning signal to impaired motor control or joint instability [

163,

164].

In occupational and athletic contexts, undetected (subclinical) weakness after apparent recovery poses a significant — but potentially correctable — risk for repetitive stress injuries, ongoing pain, and reinjury.

This underscores the utility of implementing comprehensive testing and correction methods that we will be discussing, practical tools that can help clinicians identify and resolve these hidden vulnerabilities

2.2.1. Muscle Weakness and Central Pain — A Vicious Cycle?

Nociception is the detection of potentially harmful stimuli — e.g., heat, cold, mechanical, or chemical inputs — by specialized peripheral receptors. Pain is the subjective experience that may accompany nociception. Either may occur without the other [

165].

The mechanisms for weakness proposed here are similar to those theorized for central pain sensitization or nociceptive pain. Cerritelli et al. describe how maladaptive predictive processing (which we cover later) can generate and maintain pain sensitization through persistent error signaling [

166]. This may create a vicious cycle: nociception and pain alter motor control [

17,

84], with muscle weakness as a key feature [

101,

102].

Biomechanical compromise resulting from weakness and other factors of altered motor control may increase nociceptive activity through altered joint loading patterns [

84] and abnormal tissue stress [

167]. This bidirectional relationship — where pain leads to weakness and weakness aggravates nociceptive inputs — highlights the need to address weakness to improve motor function and potentially interrupt persistent pain states.

2.3. Muscle Weakness, an Often-Unnoticed Gap in Treatment of nsMSDs

AMI literature focuses on objective tests for muscle inhibition, including EMG [

150], H-reflex testing [

145,

168,

169], and burst superimposition (interpolated twitch) testing, in which MVC is compared to electrically enhanced contraction [

28,

29,

46,

63,

170,

171]. High cost, time demands, and the limited number of muscles that can be tested mean these methods are rarely used clinically. Meanwhile, the most common clinical tools — MMT and MMT with HHD — receive little attention in AMI research.

Although EMG is considered the gold standard for the analysis of muscle activation [

172], it is not equivalent to MMT, particularly when MMT is applied according to the protocols reviewed here. The most easily used form in clinical settings, surface EMG (sEMG), has significant accuracy limitations, potentially suffering from artifact, cross-talk, and signal cancellation, particularly when sampling from deeper or nearby muscles. This limits its sensitivity and specificity [

173]. Intramuscular (needle) EMG offers greater precision but is invasive, painful, and logistically challenging for routine or large-scale testing [

174]. Leisman et al. (1995) showed that EMG amplitude can be elevated even in muscles that test weak on MMT, revealing possible dissociation between activation and functional muscle response [

175]. Nonetheless, as demonstrated earlier, sEMG has shown some promise as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool for AMI.

AMI is often overlooked by athletic trainers and physiotherapists, perhaps due to educational deficits [

137]. However, the subclinical nature of AMI, the scarcity of treatments that reverse it, and the lack of clinical diagnostic criteria may also discourage considering the role of muscle weakness in patients’ conditions. With most muscle testing texts listing tests for only ~200 of the 600 muscles of the body [

66,

176] even if MMT were accepted as a valid test for AMI, the extent of the condition would still be undetected. Despite the observation, discussed in

Section 2.5, that correction of muscle weakness can reduce musculoskeletal symptoms, clinical observation also suggests that the number of weak muscles does not necessarily correlate with the level of pain or disability. This means that MMT may not be a useful medico-legal tool for establishing levels of disability.

2.4. Motor Control, a Clinically Confounding Concept

Although the field has progressed in the last 20 years, Latash and Anson’s statement (2006, p. 1152) remains essentially true:

“In order to study a phenomenon, one has to be able to define it and to have tools that can identify the phenomenon or, even better, the tools to quantify it. In the area of the control and coordination of movements, including atypical movements that may be performed by patients seeking help from physical therapists, such tools and definitions are commonly absent.” [

177]

Latash reiterated the comment in 2021, noting the lack of diagnostic tools and the difficulty translating findings into clinical practice [

178].

Motor control deficits — including weakness of individual muscles — are consistently observed in nsMSDs, even during remission [

7,

9,

18,

21,

22,

23,

179]. In response to pain, muscles or subsets of motor units display altered force, timing, and coordination [

17,

27,

84,

102,

150,

180,

181]. Reflexive or supraspinal mechanisms may delay activation or disrupt normal muscle recruitment patterns [

24,

83,

111,

112,

182].

Abnormalities in individual muscles, detectable through sEMG or MMT, often accompany broader dysfunctional motor patterns in response to pain. These include co-contraction of antagonists [

183], reciprocal inhibition of opposing muscles [

121], abnormal variability in muscle function (excessive or overly limited) [

184], and compensatory hypertonicity, rigidity, or guarding when pain is anticipated or muscles are inhibited [

17,

20,

179,

185,

186].

Several clinical methods have been developed to assess motor control. These include sEMG [

187], balance and center-of-pressure measurements [

188,

189,

190], joint position sense evaluation, motion analysis, and functional movement control tests [

191,

192]. In clinical settings, however, efforts to treat symptoms linked to aberrant motor control face several challenges:

High individual variability in aberrant motor control presentation, and a lack of methods to identify and categorize these patterns [

187,

193].

A shortage of clinical studies and evidence-based treatments showing consistent improvement from motor control interventions [

187,

193].

A shortage of trained clinicians familiar with procedures (e.g., sEMG) and the interdisciplinary knowledge to integrate them [

187].

Limited effectiveness of motor control exercises and poor long-term compliance with prescribed routines [

160,

187,

194].

Uncertain clinical relevance of motor control changes: Ongoing debate regarding whether such changes are causal, compensatory, or merely associated with pain and disability [

177,

178,

195,

196,

197,

198,

199].

2.4.1. Persistent Motor Patterns as Learned Behavior

Motor control alterations acquired through pain or trauma often persist even after symptoms resolve. Learning theory and neuroplasticity studies suggest that new motor skills typically overlay, rather than erase, earlier patterns; new memories are built on the foundation of prior learning [

200,

201]. If muscle inhibition is a form of learned behavior, new movement patterns established during rehabilitation may still avoid using inhibited muscles [

202,

203]. In particular, motor inhibition learned through pain or trauma can persist and therefore shape subsequent motor learning [

204,

205,

206,

207].

Evidence shows that although motor control exercises may reduce symptoms, they often do not outperform other exercise therapies. Benefits are typically modest, and residual deficits may remain [

18,

21,

22,

179,

197,

208,

209]. Approaches to determine the personalized application of motor control interventions remain undeveloped [

184,

187,

197].

This review posits that MMT can serve as a valid clinical tool for pre- and post-treatment evaluation of motor control impairments, particularly when paired with the treatment principles introduced later. Although more studies on motor control metrics are needed, clinical observations of gait, posture, range of motion, muscle tone, and phasic over-facilitation suggest that correcting muscle weakness may improve key aspects of motor control [

39,

100,

210,

211,

212,

213,

214,

215].

2.5. Is NOw Reversible?

Some evidence cited here comes from Applied Kinesiology (AK), a field encompassing diverse methods that use novel applications of MMT. Over 60 years, clinicians practicing AK have produced thousands of case reports and clinical studies, including time-series outcomes covering >10,000 patients. Some reports contain detailed anatomical, physiological, and neurological analyses and innovative, though unproven, therapeutic approaches [

216,

217]. In addition, there is a growing body of peer-reviewed research (e.g., [

31,

113,

175,

218,

219,

220,

221,

222,

223]), along with several comprehensive textbooks [

39,

100] covering aspects of AK. Rigorous studies needed to establish evidence-based status have been lacking, however, adding to AK’s controversial history.

AK has been sharply attacked in non-peer-reviewed articles that did not address most of its existing literature [

224,

225,

226], though better founded criticisms also exist (including [

227,

228,

229]).

Part of the problem is that, over the years, the name “AK” has been colloquialized — applied to a wide variety of practices that use MMT in different ways and for different purposes, even by unlicensed practitioners [

69]. Against that backdrop, in its original context, AK holds that MMT can be used for functional neurologic assessment, particularly to gauge the integrity of neural circuits involved in motor execution [

37]. Today, an estimated 1 million practitioners worldwide use methods derived from the basic principles or findings of “AK”, centering around DCs, but including MDs, DOs, PTs, and DDSs [

230].

Among the many AK-based methods and procedures, however, this review relies on only one claim: the immediate reversibility of muscle weakness (which we have labeled NOw). Other claims of AK are unnecessary to the generation of our central hypotheses, and beyond our scope to address. (Nonetheless, certain evidence we examine, though not necessarily derived from AK, supports observations typically attributed to AK.)

2.5.1. The History and Current Uses of AK Inhibition Reversal Methods

The reversibility of NOw was discovered in 1964 by George Goodheart, founder of AK. Goodheart used Kendall’s testing methodology to determine whether the muscle was normal or weak — he did not attempt to estimate strength by grade. (

Section 3 shows that muscles capable of offering resistance yield a result best interpreted as binary.) He went on to discover that each muscle was associated with a unique set of reflexes thought to relate to the vascular, lymphatic, neurological, and acupuncture meridian supplies to the muscle. With 60 years of history and extensive individual experience, it is taken as fact by AK practitioners that manual treatment of these reflexes, along with manipulation of specific vertebrae and massaging the muscle’s origin and insertion, will immediately restore normal function to muscles in patients without organic causes for the weakness. [

39,

99,

100,

231] Although the reliability of these methods has not been rigorously studied, multiple case reports from the AK repository (e.g., [

86,

210,

211,

212,

213,

214,

215,

232,

233,

234,

235]) demonstrate functional restoration by various means.

As put forth by Suvvari (2024), case reports, though often discounted, “are indispensable in evidence-based medicine, offering crucial insights into rare cases and innovative treatments. While they are not as robust as randomized controlled trials or observational studies, case reports provide essential information that can guide clinical decision-making and stimulate further research. Embracing the significance of case reports can enrich medical education and improve patient outcomes [

236] (p. 5452).” Case reports can also be valuable for generating hypothesis [

236,

237], which is how they are used in this review.

Reversal of muscle weakness is further supported by the author’s clinical experience restoring function to thousands of muscles over decades (with short case reports in Appendix A), as well as textbooks and studies on AK practice [

31,

39,

100,

238]. Weissfeld (2021), described in detail in

Section 3.2.2, is a small study that confirmed the same finding using methodology not derived from AK.

The potential benefits of muscle weakness reversal were broadened in the late 1970s, when Alan Beardall, a student of Goodheart’s, enlarged upon Kendall’s catalog of documented muscle tests, bringing the number of testable muscles to nearly 600 bilaterally, while also presenting the set of reflexes to treat for each [

239]. In 2013 Buhler and Williams published

Muscles of the Neck, further expanding that number [

240]. To be considered definitive for each muscle, these extended test protocols need to be compared with other measures like EMG to confirm test specificity. Even without such confirmation however, they still comprise an enlarged survey of possible force vectors of the tested limb, assuming that a limb should be able to effectively resist incoming force from any vector.

Beginning in 1979, Buhler actualized this protocol as a team doctor for the National Basketball Association’s (NBA’s) Utah Jazz for more than two decades, eventually naming the method Advanced Muscle Integration Technique (AMIT

®). A retrospective analysis (1990–2010) showed Jazz players missed less than half as many games as the league average from 1990–2000, the period that overlapped Buhler’s tenure. [

241]. These findings, along with case reports, news articles, and interviews with players and team staff [

242,

243,

244,

245], suggest that this method may provide unexpectedly beneficial outcomes, though high quality evidence is lacking.

2.6. The Limitations of MMT as It Is Practiced

MMT is the most widely used clinical method for assessing muscle function [

219,

246,

247,

248], but reports on its reliability and validity vary. Reliability is supported in some studies [

221,

249,

250,

251], particularly when fixed or handheld dynamometers are used [

70,

247,

252,

253]. However, other studies report poor reliability [

247,

249,

254], and, particularly when performed without instrumentation, MMT’s subjectivity, insensitivity to small

-to

-moderate force changes, and uneven grading [

248,

250,

255,

256,

257,

258,

259], have led some to question whether MMT is adequate for making clinical judgments [

248,

254]. These concerns have likely limited MMT’s use in research, including AMI studies, hindering translation to clinical practice.

Not concerned with movement, most studies focused on force-related aspects of break tests, monitoring peak force to discover MVC. “Until a formal time-and-motion [FM/T] study of muscle testing has been performed for these methods,” Caruso and Leisman (2000 p. 683) argued, “claims of subjectivity or objectivity must be regarded as premature. [

113]” In Part II, we examine FM/T research that reveals a different model of MMT.

While the term “muscle weakness” is well used, researchers often state that the brain “thinks” in terms of movements, not individual muscles [

260]. Stimulation of specific motor cortex zones has been shown to trigger complex, naturalistic movements involving multiple muscles and joints [

261]. Clinicians performing MMT typically test “individual muscles,” but the number of possible distinct test vectors is vast; even slight changes in position or force direction can alter recruitment. Highlighting specific muscles is a practical convention for sampling representative movements. Joints with fewer degrees of freedom (e.g., knee or ankle) yield a more representative sample of all possible movements than highly mobile joints like the shoulder and hip.

The findings of this review argue that weakness is the most actionable of all abnormal motor expressions to assess and treat.

3. Motor Activation as a Binary Phenomenon

Conventional interpretations of MMT generally imply that its purpose is to measure or estimate voluntary strength (force resisted or produced) on a graded continuum. Kendall notes (p. 18): “Grading strength involves a subjective evaluation based on the amount of pressure applied. [

66]” Given the evidence in

Section 2.6 showing that MMT is insensitive to force increments, a better approach is to focus on movement — whether the tested muscle locks or unlocks.

Muscles can exert a range of force from a slight nudge to MVC — an analog capacity that is accurate but incomplete as a description. While voluntary activation is largely analog in execution (though not initiation), binary function plays a major role in muscle function and dysfunction. Here in Part II, we present an approach that frames muscle testing and function as fundamentally binary.

3.1. The Binary Nature of Muscle Function

The binary nature of muscle function can be illustrated by established principles of motor control. In Go/No-Go tasks, motor action is either initiated or inhibited in response to specific stimuli [

262]. Motor priming experiments show that stimuli — whether consciously perceived or subliminal — can instantly flip a binary switch affecting motor response accuracy and speed [

263,

264,

265]. Similarly, approach-avoidance and freeze responses are functionally binary, though their outward expressions can be complex and context-dependent [

126,

266]. Across these examples, immediate change in functional priming is a hallmark of binary responses.

The binary nature of muscle response is evident when comparing muscle performance before and after specific sensory inputs. Schaefer et al. (2022) (

Section 3.4,

Figure 1) showed that focusing on unpleasant imagery can trigger an immediate shift from isometric holding to eccentric yielding [

33] in normal muscles. Rosner et al. (2015) [

220] and Caruso and Leisman (2000, 2001) [

113,

267] found that muscles show similar binary changes when tested before and after exposure to certain cutaneous stimuli.

Binary facilitation extends to inputs from other sensory modalities, including: visceral [

39,

100,

268,

269,

270], olfactory [

271,

272], visual [

273], and various cutaneous inputs [

102,

168,

220,

270,

274,

275,

276], as well as emotional stressors such as making counterfactual statements (lying) [

218,

223]). These show that a muscle’s capacity to activate may be conditional, based on interpretations of the current internal and external environment. Although this review is focused on chronically, not transiently inhibited muscles, these findings regarding the conditionality of muscle activation support a key contention of AK [

37,

39,

100,

113,

220,

267].

NOw muscles may be understood to be chronically conditionally inhibited, as if there were a persistent interpretation that use of the muscle would lead to a noxious outcome. Additionally, as mentioned earlier, instead of being conditionally inhibited, a muscle can become conditionally over-facilitated in response to the presentation of a noxiously-interpreted stimulus; the muscle will not weaken to stimuli otherwise expected to induce weakness.

3.2. The Binary Nature of Muscle Dysfunction

Clinical evidence from treatments for NOw supports this model. Interventions addressing muscle weakness consistently produce a binary shift from dysfunction to normal function, not gradual improvement. This shift is seen in two categories of treatment: those that temporarily suspend AMI, and those that produce lasting normalization of muscle weakness (potentially including AMI).

3.2.1. Reversal of NOw Implies a Binary Functional Deficit

As noted in

Section 2.2.1, decreasing afferent output from associated joints can temporarily reverse muscle activation deficits. This supports a binary model of motor control pathology: muscles shift from inhibited to facilitated states, then return to inhibition when the effect wears off.

Treatments from AK, reviewed in

Section 2.5, also show this binary pattern, with muscle function restored immediately after treatment, but typically not reverting to weakness.

3.2.2. Experimental Evidence of Immediate Recovery

In addition to introducing the mPTSD concept, Weissfeld (2021) provides evidence for the binary nature of muscle dysfunction and suggests a role for maladaptive learning in muscle weakness. In the study, side-to-side eye movements, thought to work by eliminating maladaptive learning, are borrowed from EMDR [

277,

278].

Section 7.1 discusses potential mechanisms for this elimination.

EMDR has consistently demonstrated efficacy in treating PTSD and depression, with recent meta-analyses confirming significant reductions in symptom severity [

279,

280,

281]. It is generally considered safe when delivered by trained practitioners, though some clients may experience temporary emotional distress or resurgence of traumatic memories during or after sessions [

282]. Controversy persists regarding EMDR’s mechanism of action: Is bilateral stimulation is essential, or do benefits primarily derive from common therapeutic elements of exposure and processing. Also questioned are EMDR’s safety and efficacy across a wide variety of patients and conditions, when compared to other methods [

281,

283].

Encompassing both sexes, and ages ranging from their 20s to 60s, Weissfeld study recruited generally healthy individuals without major musculoskeletal complaints. Experienced MMT practitioners first identified and recorded a variety of muscles testing weak (by binary measure) in each participant. Each weak muscle was then retested, followed immediately by 15 seconds of EMDR-style eye movements. Muscles were tested again immediately afterward.

Immediately after eye movements, 91% of weak muscles tested normal. On retest about 15 days later, over 84% remained normal. In some cases, multiple muscles normalized after a single application, suggesting muscle weakness can resolve — in multi-muscle patterns. In a crossover control group evaluating 42 weak muscles, 88% remained weak without treatment over a similar period. When treated, these muscles showed similar improvement.

The study also included a case report of a patient who, 15 years earlier, had a skiing accident causing an ACL tear and other ligament damage. Although surgery was functionally successful, minor pain persisted. MMT revealed multiple subclinical weaknesses in the knee and ankle, consistent with typical AMI findings. After correction using the eye movement protocol, the muscles remained normal one month later, with pain resolved.

In each case, changes in muscle function were immediate and binary: muscles were either weak or normal, with no intermediate gradations.

Future studies could incorporate sham-control conditions (e.g., visual fixation without bilateral saccades) to rule out expectancy or examiner bias. Such controls would allow clearer attribution of immediate muscle normalization to the therapy’s effects. Other therapies — e.g., spinal manipulation, acupuncture, or other sham treatments — could be substituted for eye movements to assess the generalizability of these treatments.

3.3. Updating a Century of Criteria for MMT Interpretations

Originating in the 1910s to assess polio patients, MMT techniques and interpretations were designed for muscles with lower motor neuron compromise causing severe deficits [

66,

176]. MMT typically uses the Medical Research Council (MRC) scale, grading muscle strength from 0 (no contraction) to 5 (full isometric resistance against submaximal examiner force). Grades 0–2 indicate muscles unable to lift against gravity; Grade 3 can lift against gravity but not resist pressure; Grade 4 can resist pressure but cannot maintain isometric contraction [

66,

284]. Only Grades 4 and 5 produce measurable resistance to incoming force, as applied in the break test.

Beyond polio, MMT is used to assess total body involvement in Duchenne muscular dystrophy [

285] and is accepted as valid for other organic conditions, including myasthenia gravis, inflammatory myopathy [

71,

286], amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [

287,

288,

289], post-polio syndrome [

255,

289,

290], chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy [

291], dermatomyositis, polymyositis, nerve impingements (disk, foraminal, or other), and atrophy from disuse or other causes [

176,

246,

253,

286,

288,

292,

293,

294,

295,

296].

In patients with nsMSDs, severe weakness (Grades 0-2) is not part of the usual symptom picture. Most muscles in these patients, when not directly affected by pain, test as either Grade 4 or 5, and occasionally Grade 3, though this observation has not been empirically validated. Because studies have shown that clinicians lack the capacity to accurately subdivide grades (e.g., 3+, 4-, 4, 4+) [

255,

257,

258,

297,

298], this leaves only two applicable grades in most cases, 4 or 5, effectively mandating a binary determination. Detailed analysis, however, suggests that binarity is more than just an artifact of the grading system; it may be built into the physiology and mechanics of the MMT break test and, our eventual hypothesis holds, the pathophysiology of NOw.

3.4. The Hidden Phenomenology of MMT

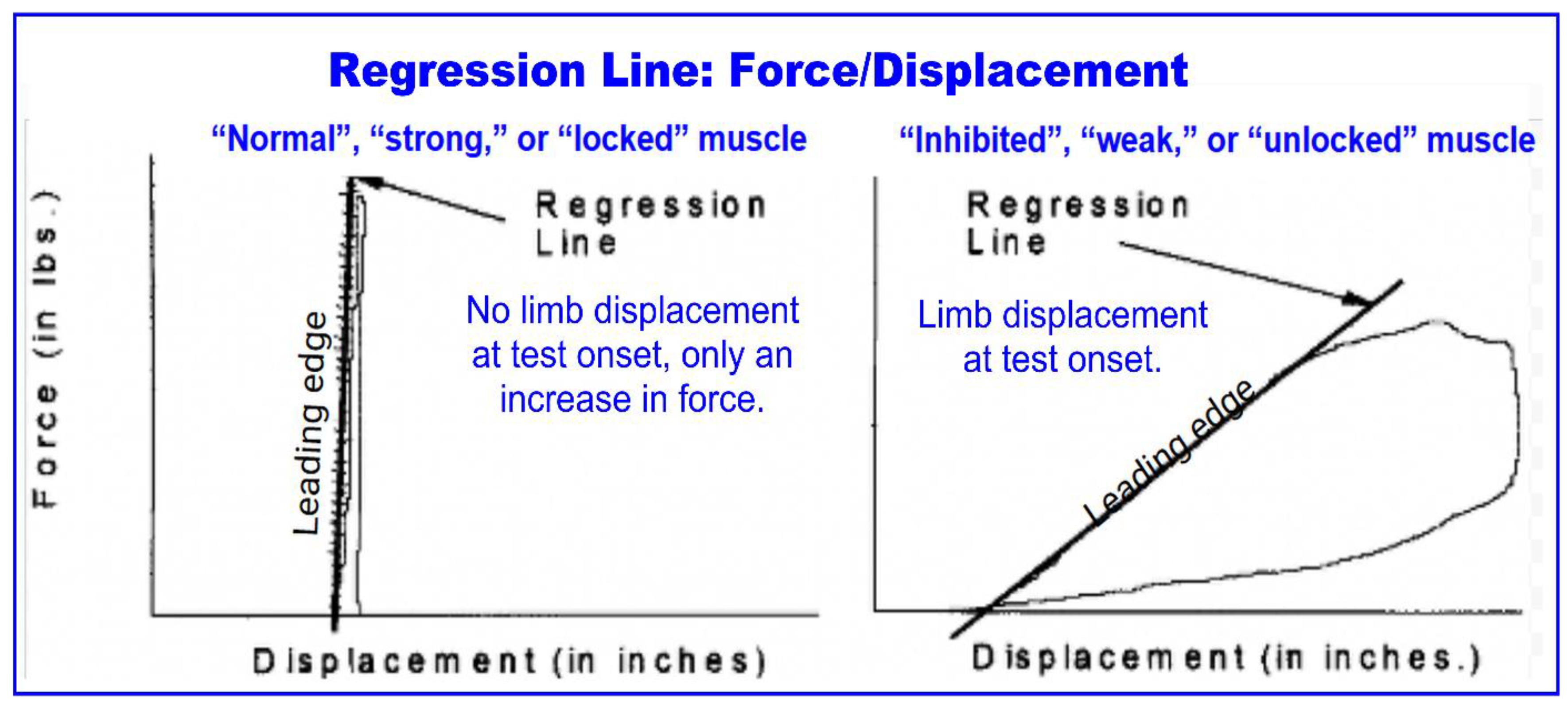

The break test is controlled by the examiner. After instructing the subject to resist their force, the examiner determines when to exert force, how quickly ramp that force, the maximal level of force to exert against a muscle that is not yielding to pressure, and how long to apply that pressure. Findings from FM/T analyses performed since 2000 suggest that rather than force estimation, muscles in patients without organic conditions can, and perhaps should be graded based solely on movement — their ability to maintain an isometric plateau.

Kendall’s

Muscles, Testing and Function is one of the two most respected MMT texts. The break test is Kendall’s recommended test. (The other, Daniels and Worthingham, emphasizes a method sometimes called the “make test” in which the subject is instructed to press into the hand of the examiner [

176]. We will not be deeply examining this form of testing.) Kendall (p.22) states that “normal” refers to a muscle that “can [isometrically] hold the test position against gravity and strong [though submaximal] pressure.” A normal muscle has “strength that is adequate for ordinary functional activities.” In performing the test, Kendall instructs a gradual initial force application that allows the subject to “get set and hold” ([

66] pp. 16, 18). This is referred to as “coupling” by Bittmann (2020). In Bittmann’s interpretation of MMT, coupling, and initial gradual increase in pressure during which the subject is allowed to adjust to the examiner’s pressure, can last several seconds [

299].

Figure 1, adopted from Schaefer et al. (2022) shows an overlay of three tests of the same muscle, each assessed while the subject is holding a differently valanced mental focus: unpleasant (red tracing), pleasant imagery (blue tracing), and a baseline test with no specific imagery (gray tracing). The top box shows force over time (F/T) and the bottom box movement over time (M/T).

Figure 1 has been slightly modified from the original. Some labels, unnecessary for the scope of this review, have been removed and others added to emphasize particular points. The key experimental finding in Schaefer — that normal muscle function can be disturbed by noxious neurological activation, mental focus in this case — is a theme that we will return to later. For now, we are interested in the phenomenological characteristics of the malfunction.

The first, and most striking difference between tracings is seen in the bottom box, which shows significant angular velocity (movement) in the red tracing beginning at just over 2.5 seconds. We are calling the moment of loss of isometric stability “Break 1.” The other two tracings, while significantly oscillating (the rapid small up and down movements of the tracings), do not show angular movement; they are isometrically stable or locked as indicated by the lack of vertical movement. The moment of complete loss of resistive capacity of the weak muscle we have labeled as “Break 2”. The blue and grey movement tracings do not break; they end when the examiner ends the test.

Second, in the top box all tracings reach similar peaks of force, between about 160 and 180 Newtons, but only the blue and grey can sustain the peak. Even as the muscle is giving way eccentrically following Break 1, the red force tracing is spiking, rising to a peak and then falling. Other FM/T studies show similar patterns of spiking force at normal levels [

220,

272]. A study showing F/T-only graphs of break tests taken to MVC also shows the same phenomenon [

71].

The observation, from these tracings, is that both normal and weak muscles are capable of producing equivalent force. This suggests that peak-force HHD, which adjudicates muscle function by its recording of the maximum force a muscle is capable of producing (MVC), may result in false negatives when testing weak muscles, though this proposition has never been directly studied. (This is seen in F/T-only tracings as well [

71]) presented Furthermore, since peak force is nearly equivalent in both weak and normal tests, the ability to attain an isometric lock is the primary finding that differentiates a weak muscle from a normal one.

This hypothesis of equivalent force in normal and weak muscles might be tested by comparing FM/T-based break test outcomes (binary lock vs unlock) with conventional peak-force dynamometry. If muscles that unlock under FM/T nevertheless generate normal peak force with HHD, this would confirm that the true deficit lies in adaptive force — the ability to sustain isometric stability — rather than in force generation. Such findings would indicate that dynamometry may miss clinically important motor control deficits.

3.5. Eccentric Action: Mechanical and Reflex Driven Force

The force produced or resisted during eccentric contractions is mechanically and neurologically distinct from force produced during isometric action in striated (voluntary) muscles. Eccentric contractions generate greater force with lower neural activation, recruit fewer motor units, and display a lower motor unit discharge rate compared to isometric or concentric actions. Like a stretching rubber band, during eccentric lengthening, elastic elements of the muscle and tendon convert kinetic energy into elastic energy, meaning incoming force is absorbed and resistance is greater. [

72,

300,

301,

302].

Continuing the test to full failure (Break 2) may be favored in research or athletic settings where maximal eccentric strength or endurance is of interest. Clinically, however, for treatment of nsMSD patients, our analysis will suggest that equal or greater diagnostic utility, efficiency, and accuracy will come from concluding the test at Break 1, with the conclusion that Beak 1, or its absence, is what establishes or rules out the presence of a motor control deficit affecting the muscle.

3.6. Adaptive Force, a New Way of Understanding MMT

Emerging perspectives regarding a capacity known as “adaptive force” are providing a basis for updating our views of MMT and its relationship to muscle function. As put forth by Schaefer et al. (2023 p. 1), “the adaptation of the neuromuscular system to external loads is usually not investigated in sports or movement sciences. Strength is commonly measured by pushing against resistance without considering the adaptive component. Adaptive force has been defined as "the neuromuscular capacity to adapt to external loads during holding [isometric] muscle actions similar to motions in real life and sports" ([

303]).

Clinically, adaptive force refers to the ability of a muscle to maintain isometric stability in response to changing force, as it is applied in the MMT break test [

33,

245,

246,

247]. Making the point that this is a major departure from conventional testing, Bittmann (2020 pp. 22-23) concludes that during MMT, "the aim is not to test the maximal strength of the patient or to ‘demonstrate’ that the patient is not able to resist the external force. The aim is to assess if the adaptation capacity of the neuromuscular system functions in a normal way. [

299]"

Reflecting the CNS’ ability to predict and adapt to changing force demands [

299], adaptive force arises from properties of ‘motor prediction, planning, and control’, a finer specification of what is usually referred to as motor control. This conceptual point is a bridge that will take us to the mPTSD model in Part III.

When adaptive force is intact, the tested muscle remains isometrically locked to the examiners full (though submaximal) pressure. When adaptive force is not effective, the muscle unlocks, yielding to eccentric motion even while force continues to rise as documented in

Figure 1. The dual possible outcome of the MMT break test, then, is locking vs. unlocking; a clear binary result.

Among currently available clinical tools for muscle assessment, only the MMT break test, which applies force that can measurably displace the limb causing eccentric contraction, directly challenges, and thereby evokes adaptive force. The H-reflex test, or any of the other aforementioned tests for AMI can induce and therefore measure the integrity of isometric holding. sEMG or EMG may differentiate between isometric and eccentric actions [

304], but they have not been studied in relation to adaptive force, and, as stated in

Section 2.3, their outcomes may not align with MMT outcomes.

Physiological oscillations observed during MMT offer further support for this interpretation. Oscillatory activity of about 10 Hz accompanies successful isometric contractions. Weak muscles typically have deficient or missing oscillations [

33,

305,

306].

This coincides with oscillations originating from the inferior olive, which are transmitted to cerebellar Purkinje cells via climbing fibers. Organizing movements and perhaps enabling the use of individual muscles [

307,

308,

309], these oscillations also coordinate timing between the cerebellum and motor cortex, supporting predictive and feedforward motor control, [

310,

311,

312], cortical motor learning, movement planning, and execution. [

313,

314]. Notably, individuals with PTSD exhibit reduced motor oscillations [

315], suggesting a common thread between PTSD and motor inhibition.

These findings challenge traditional interpretations of MMT and establish adaptive force as a binary, predictive control variable. When a muscle unlocks under load, the CNS has failed to maintain the necessary forward model of resistance. In short, this provides a basis for the hypothesis that NOw is a functional motor control disorder, and takes a step towards tying it to mechanisms of PTSD.

3.7. Another Way to Perform a Break Test?

In

Figure 1, we observe that the M/T tracing of the weak muscle (red tracing, bottom box) shows an isometric plateau during the first 2.5 seconds. This implies that weak muscles attain isometric locking for some period of time before beginning eccentric movement. These results are defined by examiners who are following a particular protocol for force application which generally coincides with Kendall’s narrative instructions. The initial seconds of the test are dedicated to slowly introducing the subject to the forces of the test. This can lead to tests taking 3-6 seconds to complete [

33,

299].

The initial isometric period may actually be an artifact of the examiner’s technique, however. For decades, AK practitioners have asserted that they determine the binary state of the muscle at the onset or “leading edge” of the test — the initial pressure applied to the limb — not after several seconds. The binary assessment, along with this style of testing has been called AK-MMT. Tracking FM/T, Caruso and Leisman (2000, 2001) set out to test this notion, producing an objective, verifiable visual and numerical record of these tests. The study focused on first milliseconds of the test, where the limb either remains steady or it gives way, a binary outcome.

Figure 2 (from Caruso 2001) is a “force-displacement” graph which shows the leading edge or initial thrust of the test. The left tracing shows a normal muscle, which resists force without movement. The right tracing shows a weak muscle, which is immediately displaced with the onset of force.

A binary test might simply reinterpret Grades 5 and 4 as “strong” and “weak” respectively, but AK-MMT represent an alternative testing technique. Although it has not been explicitly delineated as such in the literature, this form of testing omits the “get set and hold” or “coupling” steps. The examiner increases force without the interplay that would allow the subject to catch up at the beginning of the test. The valid concern offered by Kendall and Caruso (2000) is that applying to much force too rapidly risks overpowering the subject. In fact, Caruso observed that experienced practitioners, utilizing this method, applied less force to weak muscles. Perhaps, they reasoned, these practitioners immediately sensed the muscle was giving way and therefore found it unnecessary to apply additional force.

This protocol might be called the “door handle” test. A quick press on a levered door handle reveals that it either gives way or it doesn’t. Extended pressure is unnecessary, making the test highly efficient in terms of both time and energy for both the examiner and the subject.

Comparing the subjective judgement of practitioners to objective outcomes, those with 5 or more years of experience had 98% agreement. That dropped to 64% for those with less than 5 years’ experience.

Several caveats exist regarding the door handle test, however. First, FM/T tracings of persistently weak (NOw) muscles have not been performed, to our knowledge. Like in

Figure 1, muscles depicted in

Figure 2 were weakened by stressful stimulus; in this case reflex points on the foot, so equivalence with NOw muscles is hypothetical. Further, a pilot study has shown that extending the time force is applied isometrically stable muscles may reveal weakness after several seconds, so the shorter test may miss hidden defects [

316]. More study is needed to pin down these variables. Finally, the door handle test works best for repeated tests of the same muscle as various stimuli are presented, as is done in AK. In Part IV, we show a hybrid technique that this author, at least has found beneficial for systematically testing many different muscles.

3.8. Clinical Utility of Binary MMT and the Case for Widespread Implementation

Despite the limitations of MMT noted in

Section 2.6, and the availability of other objective assessments, we argue that MMT — when applied using the methodology described here — offers unique advantages for evaluating motor control in clinical practice.

In addition to the aforementioned finding of 98% accuracy when used by experienced practitioners, Bohannan (2018) found near-perfect test-retest and inter-rater agreement was possible for most muscle actions when binary assessment was used [

250]. Applied as a binary test, MMT outperforms well-accepted clinical tools including deep tendon reflex testing [

317,

318], palpation [

319,

320,

321,

322,

323], and radiological evaluations [

324,

325,

326,

327]. Although to our knowledge FM/T devices are not yet commercially available, these findings suggest that such tools might improve training and accelerate proficiency.

In summary, these points argue for more widespread use of binary MMT for patients without organic conditions:

Only binary MMT directly evaluates the efficacy of adaptive force.

Focus on movement, not force, reduces limitations of sensitivity and subjectivity.

High concordance with objective FM/T tests, in experienced hands.

Highly scalable; >600 muscles can be assessed.

The binary state can be identified in tests taking well under 1 second, making it time-effective and less effortful.

These findings support the integration of binary MMT into standard musculoskeletal evaluation. As the following sections show, such weakness may represent not just a mechanical deficit but a learned, reversible motor inhibition — one that reflects the nervous system’s ongoing prediction and avoidance of negative outcomes.

4. Maladaptive Neuroplasticity, a Missing Link in Motor Dysfunction?

The diagnostic and therapeutic challenge of addressing nsMSDs requires understanding the top-down drivers of pain and motor dysfunction — i.e., maladaptive neuroplasticity or learning — and employing methods that target them.

Central sensitization, a well-documented condition often attributed to maladaptive neuroplasticity, involves structural, functional, and chemical changes that make the central nervous system (CNS) hypersensitive to sensory stimuli, particularly pain [

328]. Normally non-noxious stimuli become linked to pain pathways, leading to persistent pain states that extend beyond tissue healing [

329]. Past experiences of injury may intensify and prolong even unrelated pain responses [

330]. These altered neural patterns represent a form of implicit memory where the nervous system "remembers" and anticipates pain, even in its absence.

If maladaptive neuroplasticity is a central driver of pain, elimination of implicit pain memories may offer a solution to pain. According to Bonin and De Koninck (2014), spinal memories that might induce pain via this mechanism may be subject to erasure through processes related to memory reconsolidation [

331]. In

Section 7 and 7.1, we review similar possibilities for maladaptive motor memories.

Focusing on motor function, Pelletier, Higgins, and Bourbonnais (2015) argue that maladaptive neuroplasticity is a key factor in nsMSDs. This challenges the stated “structural-pathology paradigm,” which assumes symptoms originate locally at the pain or injury site. They propose that associative learning links movements with pain or trauma, altering sensory processing, motor control, and pain perception. They identify the failure to address these changes as a “missing link” in musculoskeletal care and call for a new paradigm [

332].

Similarly, Ablin et al. (2024) report that nociplastic pain — altered CNS pain modulation without clear tissue pathology — can involve functional and structural changes in motor networks [

333]. This suggests maladaptive motor learning may interact with central sensitization, compounding pain and motor dysfunction.

Changes in muscle function — including inhibition as part of maladaptive motor plasticity — may aggravate nociplastic pain or central sensitization, adding muscle and joint dysfunction to already altered CNS pain modulation.

Like PTSD and chronic anxiety, NOw may be a behavioral adaptation driven by maladaptive learning. It may be encoded through conditioned muscle- or movement–trauma associations and sustained by avoidance learning in a two-stage process [

334,

335,

336]. Instead of focusing on “emotional” parameters, as in PTSD, these mechanisms may specifically affect motor function, detectable in individual muscles with MMT. The mPTSD model describes how muscle weakness may be acquired, sustained, and resolved, as shown in the graphical summary (of mPTSD) presented at the beginning of this paper of this paper.

Trauma (pain, stress or injury), occurring in temporal proximity to movements (contraction of muscles), associates the sensory and motor events. Persistent antalgic movements may add to or cause similar associations.

Th associations create ongoing predictions that using the muscle will (re)trigger the trauma, so it is avoided during movement planning — the first stage of the response.

In the second stage, new synergies are developed to avoid using affected muscles. These are likely to be less efficient and maladaptive, yet become the preferred choice for functional activities [

337]. (A muscle or motor synergy is a coordinated activation pattern in which muscles cooperate with specific timing and force to produce a segment or module of movement. Multiple synergies combine to achieve complex goals [

338,

339].)

As in two-stage avoidance learning models of PTSD or anxiety disorders, habitual avoidance prevents corrective experiences that could reintegrate the muscles once healing has occurred.

With avoidance encoded in cerebellar internal models via error-based learning, its interactions with the motor cortex establish new synergies that reformat future movements.

Successful treatments for mPTSD may work by eliminating muscle–pain/trauma associations through the disruption of memory reconsolidation.

These points will be elaborated upon in succeeding sections.

4.1. Psychoneurokinesiology: A Broad Framework for Motor Conditioning

We propose psychoneurokinesiology (PNK) as a framework for studying how psychological factors, mediated by the nervous system, influence movement and motor function. Like psychoneuroimmunology and psychoneuroendocrinology with the immune and endocrine systems, PNK considers how learning processes (behavioral conditioning) can shape motor behavior. In later sections, we return to PNK as a way to integrate potential causative factors of mPTSD with conditions like FW and kinesiophobia.

4.2. The Mechanism of mPTSD; Theoretical Background

Focused on prediction and learning mechanisms, the mPTSD model builds on the relationship between fear-avoidance and aberrant motor control. Hodges and Moseley (2003) proposed that changes in motor function can originate during movement planning, when the prediction (fear) of pain leads to predictive avoidance of activating certain muscles [

82]. This occurs upstream of the motor cortex’s dispersion of control signals to the spine. Neige et al. (2018) suggested that once such changes are acquired, they may persist, delaying muscle activation. While both center on potential changes in the motor cortex, evidence reviewed here suggests a larger role for the cerebellum, whose predictions modulate motor cortex activity [

340].

Focusing on the lumbopelvic area, Hodges and Moseley summarize a number of potential mechanisms by which pain and nociceptive signals might interfere with harmonious muscle function, potentially leading to further pain. Pain may evoke cortical inhibition, delayed central transmission, and motor neuron inhibition either directly or through reflex inhibition (AMI). Pain and nociception, which may alter motor output, also alter afferent (proprioceptive and somatic) signals, potentially leading to mismatches (prediction errors) with existing internal models of the body and its potential actions, managed by the cerebellum [

341]. Pain also evokes stress responses and fear, utilizing attentional resources. This may increase latencies and errors in movements.

Hodges and Moseley give particular focus to the importance of the “fear-avoidance model”, a behavioral theory with considerable support in the literature. They cite a number of examples in which motor control — the unconscious selection of motor patterns — is affected by fear. Fear-avoidance is also described in kinesiophobia, the outward behavioral response of avoiding movements or activities that have been associated with pain [

342,

343].

In one example that offers direct support for our thesis, they point to delayed contractions in the transverse abdominis frequently seen in patients with a history of low back pain. As suggested earlier, weak-testing muscles may exhibit delayed activation in MMT, and, as was shown in

Section 3.7 muscle weakness can be demonstrated in the immediate onset of MMT, implying the presence of delayed activation [

112,

113]. Although confirming evidence is needed, this logically connects fear-avoidance to MMT outcomes.

Hodges and Moseley further draw the association that (p. 365), “if fear of pain can disrupt the normal control of the trunk muscles, this may provide a link between psychosocial factors and physiological changes that lead to recurrence of pain. It could also be interpreted that these changes in motor control are an adaptation to limit loading and prevent recurrence.” Moreover, they state, “these adaptive strategies may provide a short-term solution with long-term [maladaptive] sequelae” that may result from reorganization of control through motor learning strategies.

Pointing to the relatively consistent finding of reduced activity of deep spinal muscles (and increased activity of superficial muscles) in patients — a pattern that has also been observed in the jaw and trunk — they note that this phenomenon supports the “pain adaptation model” introduced in

Section 2.1.

4.3. Predictive Processing and Reinforcement Learning, Intertwined Models

In the next two sections, we will be elaborating on two broad, intertwined paradigms of behavioral adaptation, predictive processing (PP) and reinforcement learning (RL), focusing on how they may be affecting movement to cause delayed activation or inhibition of muscles.

In psychology and behavioral sciences, RL is an umbrella term including theories of associative learning, classical (Pavlovian) conditioning, operant (instrumental) conditioning, extinction, counter-conditioning, and two-stage passive avoidance learning, all of which involve the cerebellum [

57,

344,

345,

346,

347,

348,

349]. In computational modeling, RL may specifically describe learning guided by reward prediction errors, with the basal ganglia playing a central role [

350]. Use of RL here is a reference to the behavioral science usage.

Arising in part as a reaction to Freud’s introspective psychology, early 20th century behavioral conditioning and modification theories from Pavlov, Thorndike, Watson, Skinner, and others were precursors to what is now called RL [

351]. Though the two paradigms certainly cooperate, RL is arguably more useful than PP for constructing an account of these two-stage learning processes.