Scientific Significance Statement: Advances in brain organoid, assembloid, and organ-on-chip technologies have revolutionized how we model human neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders. By mimicking key aspects of human brain architecture and function, these stem cell-derived platforms offer unprecedented insights into disease mechanisms in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. They enable more accurate studies of amyloid aggregation, neuronal degeneration, and neuroinflammation, while also enhancing drug discovery. Despite challenges like variability and limited vascularization, ongoing innovations are rapidly increasing their fidelity and translational potential, marking a new era in human neuroscience research

Introduction

The human brain's intricate structure and sophisticated operations give rise to our most advanced mental capabilities, from abstract reasoning to consciousness [

1]. When this delicate neural machinery becomes disrupted - whether through developmental issues, injury, or disease - it can manifest as devastating neurological and psychiatric conditions [

2]. Research continues to reveal that many of these disorders originate during early brain development when crucial neural circuits and connections are first established [

3]. Despite extensive research into these neurodevelopmental origins, scientists can only identify the specific causes in about 20% of cases. This substantial knowledge gap underscores how much remains to be discovered about the intricate processes of brain development and their role in neurological and psychiatric conditions. As a result, alternative experimental systems that are accessible, morally just, and closely resemble the human environment must be used. And that's when the emergence of human pluripotent stem cell (hiPSCs) technologies revolutionized our ability to study human biology in controlled laboratory settings [

4]. By harnessing both embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells, researchers can now generate authentic human neural tissue, opening unprecedented windows into brain development and disease [

5]. The transformation of ordinary human cells into pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) enables the examination of how specific genetic profiles, both healthy and pathological, influence neural development [

6]. This powerful system is further enhanced by precision genetic engineering tools like CRISPR-Cas9, allowing researchers to deliberately introduce or repair disease-causing mutations, creating customized cellular models illuminating the roots of neurological conditions [

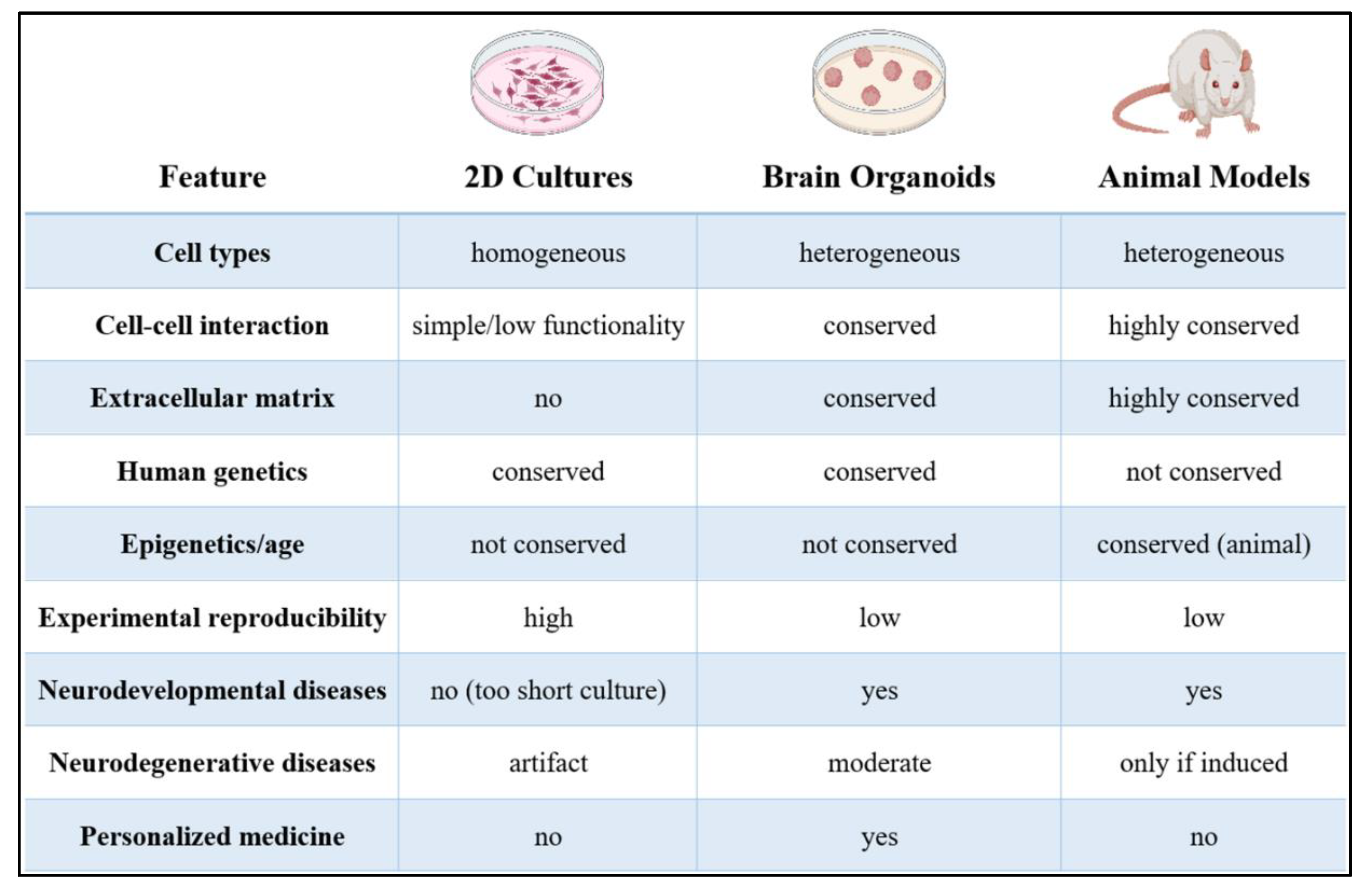

7]. Traditional monolayer cultures, while valuable, fail to capture the complex tissue architecture needed to fully model disease states [

8]. This limitation spurred the development of advanced 3D culture techniques, including neural organoids, assembloids, and microfluidic chips, which better mimic the organization and environment of the human nervous system [

9]. However, even these 3D models have limitations in replicating the intricate interactions between different brain regions, cell types, and the progression of diseases [

10]. Despite the tremendous promise of brain organoids, it is important to understand the limitations of organoid models. Therefore, this review aims to provide a balanced view of the advantages and disadvantages of brain organoids, focusing on sophisticated approaches that merge multiple neural tissues and microfluidic chip technologies to better replicate the intricate neural circuitry of the human brain [

11,

12].

2. Advances in Brain Organoid Methodologies

A growing body of research has established that the origins of many neurological disorders can be traced back to early neurodevelopment [

13,

14]. While animal models have long been integral to neuroscience research, their ability to replicate human neurodegenerative disease mechanisms remains limited due to interspecies differences and ethical constraints [

15]. This has driven the scientific community toward developing human-based in vitro systems. One of the most transformative breakthroughs in this area was the introduction of brain organoids by Lancaster et al. (2013) [

5], which enabled the recapitulation of early human brain development in a three-dimensional format using human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs).

Early brain organoid models were primarily unguided and relied on the inherent differentiation capacity of hPSCs to self-organize into neural structures [

5,

16]. These initial constructs were instrumental in understanding cortical layering and neural progenitor expansion, but they lacked structural complexity and reproducibility. Over time, the methodologies evolved into two principal approaches: guided and unguided organoid formation. Guided protocols incorporate specific extrinsic patterning factors to direct stem cells toward defined regional identities, while unguided protocols allow spontaneous morphogenesis based on intrinsic cues [

5,

17].

Despite their promise, traditional brain organoids were limited by poor vascularization, restricted maturation, and a lack of functional long-range neuronal circuits [

6]. These limitations inspired the development of assembloids, an innovative approach introduced by Pasca and colleagues [

18,

19]. Assembloids are created by fusing multiple region-specific brain organoids or integrating different cell types, such as cortical, subpallial, or spinal cord-like tissues, into a single construct. This facilitates inter-regional communication and the development of more complex, functional neural networks that better mimic human brain architecture and activity. Recent studies have demonstrated assembloids' ability to model migration patterns, synaptic connectivity, and circuit dysfunction relevant to disorders like epilepsy, autism, and schizophrenia [

20,

21].

The fabrication of assembloids employs various techniques. One common method is co-culturing, where distinct organoids are placed nearby within the same matrix to allow spontaneous fusion and interaction [

22]. Another strategy uses microfluidic technologies, such as micropillar and tunable microhole arrays, to guide spatial assembly and promote the integration of human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) into brain region-specific constructs [

12,

23]. Additionally, guided differentiation within a single culture system enables the generation of diverse neuronal populations without the need for post hoc fusion, increasing scalability and reproducibility [

24].

In parallel, organ-on-chip platforms have emerged to enhance physiological relevance by replicating mechanical forces, fluid shear stress, and biochemical gradients found in vivo [

25]. These devices use microfabrication techniques—most commonly soft lithography with polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)—to produce microchannels that simulate vascular flow and tissue interfaces [

26]. Photolithography first patterns the channel design onto silicon wafers, and PDMS is cast and bonded onto glass to create enclosed structures. These platforms support the incorporation of primary cells, immortalized cell lines, and stem cell-derived neurons, enabling studies of neurovascular interactions, blood-brain barrier integrity, and drug permeability [

27,

28].

More recently, 3D bioprinting and genetic engineering technologies have been integrated into organoid and organ-on-chip systems to further refine spatial organization and cell-type specificity [

29,

30]. These advancements have allowed researchers to model previously inaccessible brain processes, such as corticospinal tract development and electrophysiological dynamics [

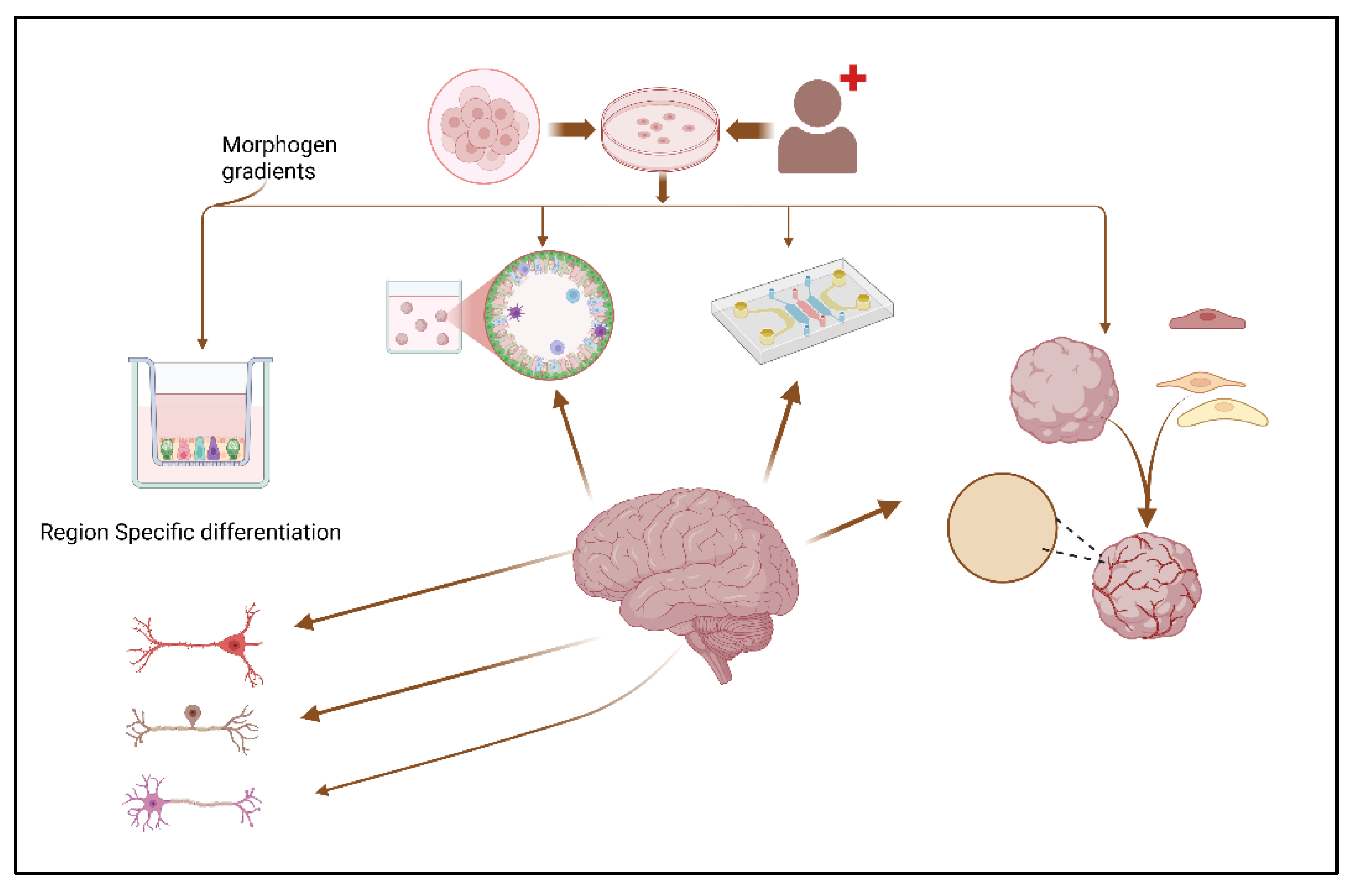

31]. (

Figure 1) Moreover, integration with biosensors and electrophysiological recording systems is enabling real-time monitoring of neuronal activity and response to external stimuli [

32,

33].

While these emerging technologies have significantly enhanced the fidelity of in vitro brain models, challenges such as high production costs, reproducibility, and long-term viability remain [

5,

17]. Nonetheless, the combination of brain organoids, assembloids, and organ-on-chip technologies is reshaping neuroscience research, offering unprecedented insights into neurodevelopmental processes and disease mechanisms that were previously out of reach [

8,

34].

3. Unravelling Alzheimer's and Parkinson's: Innovations Through Organoids and Organs-on-a-Chip

The quest to decipher the complexities of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's have historically been constrained by the limits of traditional research models. The inadequacy has spurred the development of more sophisticated models—organoids, assembloids, and organs-on-a-chip—that embody the three-dimensional complexity and interactive milieu of neural tissues. These advanced systems have revolutionized our approach to understanding the pathophysiology of neurodegenerative diseases and exploring novel therapeutic avenues. Now, let's delve deeper into how these sophisticated tools are shedding light on diseases, providing unprecedented insights into their complex pathology, and offering new possibilities for therapeutic intervention. [

35,

36]

3.1. Parkinson’s Disease: Insights from Organoids and beyond

Parkinson’s Disease (PD) is characterized by the progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra, leading to motor symptoms such as bradykinesia, rigidity, and resting tremor. However, PD is also a multisystem disorder that includes non-motor symptoms like autonomic dysfunction, cognitive decline, and sleep disturbances [

37]. Organoid-based models have been instrumental in elucidating the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying PD, including dopaminergic neuron loss, alpha-synuclein aggregation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and lysosomal impairment [

38]. Genetic studies using patient-derived iPSC models have identified mutations in genes such as LRRK2, PINK1, PARK7, and SNCA, which contribute to dopaminergic degeneration and disrupt cellular homeostasis. These models have also facilitated the investigation of protein misfolding and intracellular trafficking defects, particularly regarding Lewy body pathology [

39]. Organoid platforms have supported drug screening efforts by enabling the testing of compounds targeting mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and endolysosomal degradation—three contributors to neuronal loss in PD [

38]. The application of CRISPR-based gene editing in PD organoids has allowed for mechanistic studies, revealing regulatory networks involved in neurodegeneration [

40].

Advances in microfluidic technologies have led to the development of brain-on-a-chip platforms, facilitating studies of interactions among dopaminergic neurons, astrocytes, microglia, and endothelial cells [

41]. The creation of vascularized PD organoids has further enabled the study of blood-brain barrier permeability and its role in disease progression. The gut-brain axis is increasingly recognized as a key factor in PD, where dysbiosis in the gut microbiome may trigger alpha-synuclein misfolding and aggregation in the enteric nervous system, which can propagate to the central nervous system. Organoid models incorporating enteric neurons and gut epithelium have provided insights into these interactions and identified potential therapeutic targets [

42].

3.1.1. Parkinson's Disease Drug Discovery

Midbrain organoids have become a cornerstone of neuroprotective drug discovery for PD, particularly in testing mitochondrial-stabilizing compounds that show promise in preserving dopaminergic neuron survival [

37]. Additionally, CRISPR-based gene-editing techniques have enabled the correction of pathogenic mutations in LRRK2 and PINK1, opening avenues for gene therapy. Studies also explore small molecules and biologics targeting alpha-synuclein aggregation, with several candidates advancing to preclinical evaluation [

43].

3.2. Alzheimer’s Disease: A Closer Look Through Advanced Models

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder, is characterized by the accumulation of tau tangles, amyloid-beta plaques, neuroinflammation, and synaptic dysfunction. Organoid models have provided an environment for studying AD progression, yielding insights into these pathological features [

5]. Patient-derived iPSC models have been instrumental in elucidating the genetic underpinnings of familial and sporadic AD, particularly mutations in APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 [

44]. Organoids have also proven valuable for drug screening, recapitulating aspects of AD pathophysiology, including amyloid-beta aggregation and tau hyperphosphorylation. Advances in co-culturing brain organoids with microglia have shed light on the role of neuroinflammation in disease progression [

40]. The integration of vascular networks into AD organoid models has addressed previous limitations by enhancing nutrient delivery and supporting long-term viability. 3D organoid cultures also enable the study of cell-cell interactions that drive neurodegeneration, such as astrocyte-mediated regulation of amyloid-beta toxicity, revealing signaling networks that influence neuronal health [

45]. Single-cell transcriptomic analyses of AD organoids have identified gene expression changes associated with disease pathogenesis, offering biomarkers for diagnosis and intervention. Efforts to better replicate the cellular heterogeneity of the human brain have led to the incorporation of additional cell types, such as oligodendrocytes and endothelial cells, expanding our understanding of white matter degeneration. AI-driven analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing data from AD organoids has uncovered molecular signatures linked to disease onset, paving the way for targeted therapeutic strategies.

The gut-brain axis has also emerged as a key area of investigation in AD research. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota has been implicated in exacerbating neuroinflammation and amyloid-beta aggregation via systemic inflammatory mediators. Researchers use organoid models to study these interactions to identify intervention points for slowing neurodegeneration. Multi-omics profiling, high-throughput drug screening, and the integration of AI-driven analysis represent future directions for AD modeling. These approaches will accelerate the development of precision medicine strategies tailored to individual genetic and molecular profiles, while enhancing our understanding of disease heterogeneity.

3.2.1. Alzheimer's Disease Drug Discovery

Organoid-based platforms have accelerated the discovery of therapeutics for AD. High-throughput screening has identified small molecules that reduce tau pathology and amyloid-beta accumulation. Testing neuroinflammation-targeting compounds in microglia-organoid co-cultures has yielded candidates for modulating disease progression. Monoclonal antibodies such as

Aducanumab and

Lecanemab have been evaluated in organoid models, demonstrating efficacy in reducing amyloid plaque burden [

46]. Organoid-based screens have also identified tau aggregation inhibitors as potential disease-modifying agents [

47].

4. Technical Innovations in Organoid Systems

The human brain's complexity and neuronal diversity, crucial for maintaining functional and structural integrity, are modeled in 3D brain organoids derived from iPSCs and ESCs, enabling advanced studies on neurodegenerative disease mechanisms and brain architecture; additionally, technical innovations focus on the 3D microenvironment and reprogramming patient somatic cells with disease genes to replicate essential brain functions such as differentiation, synaptic connectivity, neuronal migration, and cell-matrix interactions. [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]

Recent advances in organoid technology extend from assemblies to microfluidic and organ-on-a-chip systems, which precisely control fluid dynamics to nourish organoids crucial for modeling neurodegenerative diseases. (

Figure 2) Furthermore, organoid intelligence (OI) technologies like microelectrode arrays and brain-machine interfaces are being integrated with high-throughput platforms, enhancing the ability to monitor neural activity and efficiently test potential treatments for neurodegenerative disorders. [

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58]

4.1. Incorporation of Neuronal Diversity and Complexity

The human brain architecture comprises complex intricacies and region-specific neuronal subtypes arising from structural variations, gene expression changes, and electrical properties representing crucial neural microcircuits. In the case of neurodegenerative disorders, specific neuronal subtypes of the brain become selectively vulnerable, exposing abnormal protein interactions and faulty neural networks to disease progression [

17,

59,

60]. Throughout the ongoing research on brain architecture, research studies have explored using in vitro models for recapitulating neural tissues. However, due to the inaccessibility of brain tissue and the inability to capture progressive brain patterning and neural cell migration observed using in vivo rodent models, emphasis has been placed on region-specific brain organoids. For instance, the human neocortex and cerebellum serve as effective brain disease models due to factors such as inside-out neurogenesis, neural maturation, migration, laminar organization, and cortical patterning [

17]. Therefore, with the rise of region-specific brain organoids, research has advanced in mimicking the spatial organization of the human brain.

Traditionally, brain organoids are developed using serum-free culture media with components like Advanced Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (AdDMEM), HEPES, N-acetyl-l-cysteine, and EGF. However, these early organoids lacked the neuronal diversity seen in vivo, with limited cellular maturation and underrepresented neuronal subtypes. Recent protocols have refined organoid generation by incorporating region-specific morphogens such as Wnt-3a, R-spondin, FGF, noggin, N2, B27 supplements, and retinoic acid, enhancing cellular maturation and the development of diverse neuronal subtypes. Despite these advances, the longevity of organoids remains constrained by internal necrotic factors that hinder further maturation and migration. [

61,

62]

To enhance the regional specificity of brain organoids, various methods have been employed, focusing on structures like the dorsal telencephalon, dorsal forebrain, and midbrain. Techniques include Dual SMAD inhibition, WNT inhibition and treatment (from early to late pulses), and EGF treatment in minimalistic media to guide the transition from neural plate to unpatterned and patterned neural tube stages, influencing the formation of diverse neural subtypes, including glial cells and progenitors. Additionally, cortical organoids are refined through the addition of Noggin and recombinant human Dkk-1 protein, promoting gene expression relevant to PAX6 and GABAergic neurons. For cerebellar organoids, methods incorporate TGF-β and BMP inhibitors, along with insulin, FGF2, FGF19, and stromal cell-derived factor 1 in the induction medium, facilitating the development of granule cells, rhombic lip progenitors, and Purkinje neurons. [

36,

63,

64]

Other methods of organoid development explore the growth of human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), their dissociation, and reaggregation into embryoid bodies (EBs) or spheroids in the presence of rho kinase inhibitors in the hPSC culture medium. These spheroids are essential for neural induction, and when combined with an extracellular matrix-rich gel known as Matrigel, they give birth to neuroectodermal connections. Neuroectodermal connections create a "neural rosette" arrangement that promotes neuronal maturation and the formation of outer radial glial cells. [

65,

66,

67]

Moreover, microarray-based gene expression studies performed by introducing specific transcription factors in mouse models can confirm the proto-map hypotheses of corticogenesis, which enables researchers to develop spatially-organized brain organoids that can recapitulate the in vivo patterning and development of neuronal subtypes. [

9] Compared to monolayer cultures, the cell density in these 3D models is significantly higher and comparable to the in vivo cell density. The majority of the brain organoids exhibit sensitivity to electrical stimulation and spontaneous electrophysiological activity. Further, most of these organoids show significant myelination of axons.

Cortical organoids, once developed, can be immunostained to study the diversity of excitatory and inhibitory GABAergic neurons through synaptic oscillatory waves, using electron microscopy and electrophysiological tests over specific periods. [

68]

In the case of cerebellar organoids, they can be patterned in insulin and growth factor-reduced media (gfCDM) and other morphogen gradients such as

ATOH1, BARHL1, and SKOR 2+ to enhance their reproducibility and cellular diversity to mimic the developmental regions of the human cerebellum. Furthermore, single-cell RNA sequencing and single-cell epigenomic studies of region-specific brain organoids using Drop-seq data analysis and transcription-factor motif enrichment analysis can reveal critical insights into chromatin state and neurogenesis related to disease progression in neurodegenerative disorders [

69,

70,

71,

72].

Other innovations that enhance neuronal diversity and promote their longevity utilize spatial-temporal dynamics that expose organoids to a hypoxic state in spinning bioreactors and rotary cell culture systems (RCCS) that are operated at 50 RPM to 60 RPM (as organoids grow) and 10 RPM to 15 RPM (as organoids grow) to exert the influence of microgravity on their functional activity [

73]. Additionally, region-specific organoids can be grown in air-liquid interface (ALI) cultures using a serum-free slice culture medium (SFSCM). The growth of region-specific organoids can be followed by live image analysis using patch-clamp recordings and single-cell RNA sequencing studies upon diazepam induction to monitor the firing patterns of neurons in organoids. Air-liquid interface (ALI) cultures are reported to significantly improve the drawbacks of cell necrosis and limited cell maturation of brain organoids under cell stresses by promoting their longevity up to 2 months [

74]. Cryopreservation using methylcellulose, ethylene glycol, DMSO, and Y27632 (termed MEDY) culture is another emerging technology to preserve the neural architecture and neural networks of region-specific brain organoids [

75].

Advancements in brain organoids include the development of fusion organoids, or assembloids, from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). These assembloids, representing forebrain and ventral-dorsal regions, are cultivated in Advanced Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (AdDMEM) supplemented with N2 and B27. Growth and patterning are directed by morphogenic gradients such as Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) for ventral patterning, Wnt signaling for dorsal aspects, dual SMAD inhibition via Bone Morphogenic Protein (BMP) and Transforming Growth Factor-beta (TGF-beta) inhibitors for neuroectodermal lineage, and Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) and retinoic acid to enhance caudal neuroectodermal lineages. [

76,

77]. Neural progenitor cells (NPCs) may need extrinsic signals or self-organization to facilitate the development of fusion organoids. These organoids can differentiate into various subtypes, such as medial ganglionic eminence (MGE), lateral ganglionic eminence (LGE), and cortical progenitors, by integrating Sonic Hedgehog (SHH)-expressing aggregates into forebrain organoids and regulating dorsal-ventral axis specification. These advancements in assembloid generation offer a platform to study interactions between specific brain regions and the impact of neuronal migration during cellular pathology in neurodegenerative disorders.

Organoid-on-a-chip systems represent further advancements, utilizing a microfluidic platform made from polymers like Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, SYLGARD 184) to mimic complex brain vasculature. Designed with CAD software, these systems integrate brain organoids with culture, perfusion, and medium channels to manage controlled laminar fluid flow with lower shear stress. This setup enhances brain organoid development and differentiation, particularly into microglial cell diversity, by facilitating nutrient and gas diffusion, and allows real-time monitoring of neurogenesis and neurotoxicity [

73]. Despite these advances, challenges in replicating the brain’s full structural and functional diversity persist. Future developments aim to address the lack of functional blood flow—a critical therapeutic determinant for organoid health—by incorporating vascularized organoids, marking the next stage of evolution. In this field [

25,

78,

79].

4.2. Achievements in Vascularization

The human brain vasculature comprises an intricate network of blood vessels totalling 400 miles, including up to 100 billion capillaries [

80], and though the brain makes up only 2% of body mass, it receives 20% of cardiac output. Beyond mere blood supply, neuro-vasculature is crucial for neurogenesis and neuronal communication, facilitating rapid vasodilation and increased local cerebral blood flow (CBF) in response to neural activity, essential for maintaining neuronal function [

81]. Furthermore, vascular dysgenesis and blood vessel dysfunction have been linked to the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases, with early signs in cerebral blood flow shortfalls and blood-brain barrier (BBB) dysfunction observed in both human and animal models [

82]. These complexities present significant challenges in replicating accurate vasculature in brain organoid modeling, underscoring a critical area for advancements in the field [

6].

Vascularized brain organoids (fVBOrs) were created using a co-culture method, where vascular progenitors (VPs), derived from guided mesodermal induction of H9 human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), were co-embedded with neuroepithelial (NE) property embryoid bodies (EBs) after neural ectoderm induction [

83,

84]. These VPs gradually wrapped around the brain organoids, leading to an integrated and fused vasculature. The developed fVBOrs demonstrated blood-brain barrier (BBB)-like features, which were confirmed by the expression of tight junction proteins and functionality assessed through their permeability and selectivity. This was evaluated by incubating the fVBOrs with rhodamine-labeled Angiopep-2, a peptide ligand of the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 (LRP1) receptor. Although this innovative model includes branched vessels, it currently lacks active blood flow, a challenge that could potentially be addressed with microfluidic techniques and further verification by in vivo grafting [

85].

Building upon previous research, another study developed vascularization in fused cortical-blood vessel organoids (fCBOs) by merging blood vessel organoids (BVOs), composed of endothelial cells (ECs), pericytes, and a basement membrane, with cortical organoids (COs) during the cortical differentiation phase [

86]. This fusion occurred in U-bottom wells, characterized by the expression of endothelial markers and perfusion capabilities. While the fusion significantly enhanced vascularization, the study noted challenges in maintaining the stability and functionality of the vascular network over time [

87]. The research underscores the potential of fCBOs to explore the impacts of neurodegenerative diseases, particularly focusing on how enhanced vascularization influences disease progression and overall brain health. [

88].

Gage and his team developed an in vivo engraftment model of hPSC-derived brain organoids integrated into the NON-SCID mouse brain, which exhibited progressive neuronal differentiation and functional vasculature system through host vasculature infiltration [

83]. They used a cranial glass window for optical tracing vessel growth and Immunostaining for the human and mouse endothelial cell markers Endoglin and CD31, confirming the growth of blood vessels. This study highlighted the importance of using an in vivo environment in promoting vascularization, survival, and function, and emphasized observing organoid behavior in situ as vascularization was a natural process in the host microenvironment.

Similarly, another study engineered cortical organoids from human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) by inducing the ectopic expression of human ETS variant 2 (ETV2) within the cells. This expression led to the differentiation of ETV2-expressing cells into endothelial cells, forming a complex vascular-like network within the human cortical organoids (hCOs) [

89,

90] The optimal conditions for this process involved using hCOs composed of 20% ETV2-infected cells, with ETV2 expression induced on day 18 of organoid development. The resulting vascularized hCOs demonstrated enhanced functional maturation, acquiring blood-brain barrier characteristics such as increased tight junctions, nutrient transporters, and trans-endothelial electrical resistance. Furthermore, these organoids developed perfused blood vessels when tested in vivo. The presence of these vascular-like structures significantly supported increased oxygen diffusion, reduced cell death, and promoted neuronal maturation within the organoids [

91].

Vascularized brain assembloids were created by co-culturing hiPSC-derived forebrain organoids with hiPSC-derived common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) and VeraVecs™ (engineered HUVECs) in AggreWell plates. Organoids were generated via dual SMAD inhibition, VeraVecs™ introduced a durable endothelial component, and CMPs matured into microglia-like cells. These assembloids exhibited improved neuroepithelial proliferation, advanced astrocytic maturation, and increased synapse numbers compared to standard organoids, enhancing the model's complexity and utility for studying neurodegenerative diseases (

Table 1) [

92,

93].

Also, researchers developed a blood-brain barrier model using spheroids derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) [

94]. These spheroids were co-cultured with primary human brain microvascular endothelial cells, creating a 3D in vitro BBB model. The advanced methodology employed involved integrating a microfluidic system to assess the permeability of the BBB spheroids to various molecules, providing a platform for high-throughput screening of brain-penetrating agents [

95].

5. Limitations

Organoids mimic human neural cell types; however, their gene expression is flawed; some important marker genes are either completely absent or drastically decreased [

96]. Although the magnitude of this effect is still unknown, these differences hold across many organoid models and could affect how accurately they can be used to research brain development and disease. Organoids exhibit chronic cellular stress, including metabolic and endoplasmic reticulum stress, unlike primary tissues, which regulate these processes dynamically [

97].

This persistent stress may disrupt normal development, affecting cell fate, maturation, and connectivity. Neural organoids lack vascularization, limiting nutrient delivery and neurogenesis. Strategies like adding endothelial cells or inducing vascular genes help, but mainly affect the periphery [

98]. Glial cells play essential roles in neural function and disease. In organoids, astrocytes form readily, but oligodendrocytes (OLGs) are rare; modified protocols now enable OLG maturation and axon myelination [

99].

Microglia, the CNS's immune cells, rarely arise in directed organoids but can develop in undirected cerebral organoids, displaying primary microglia-like properties [

100]. iPSC-derived microglia, when transplanted into organoids or mouse brains, show immune responses and neuron interactions, making organoids valuable for studying glial function, inflammation, and neurological diseases [

101]. Because there are no established procedures, variability is a major obstacle in the ongoing evolution of human organoid culture. Inconsistencies arise because different techniques are used to create organoids from stem cells. Efficiency and diversity have increased as a result of recent changes in cultural conditions. Single-cell profiling technology and standardized protocols may assist in lowering variability and make comparisons with in vivo counterparts possible. Variability resulting from individual variations, such as age and genetics, may also provide information about individual differences in human biology [

102].

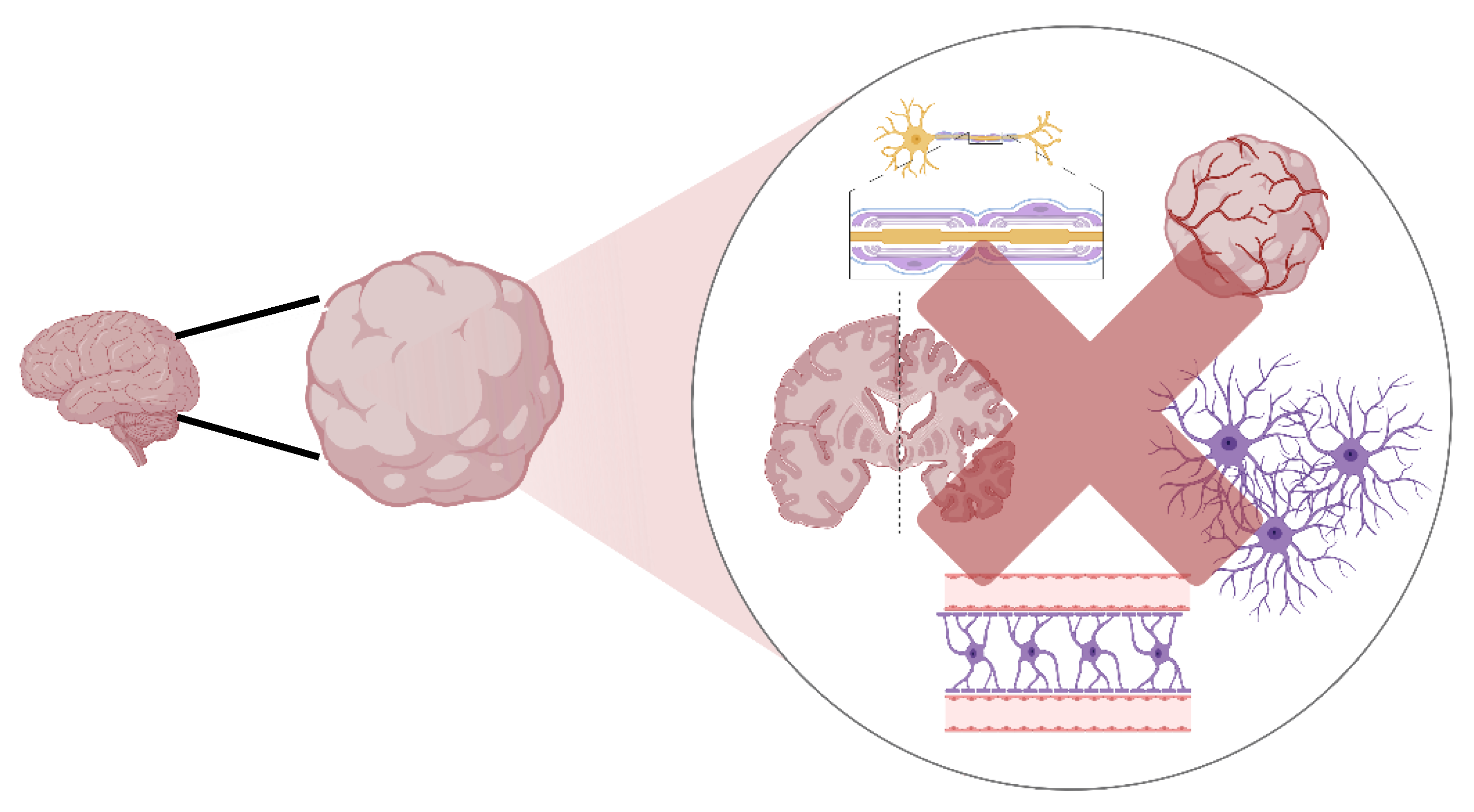

Although they are still in the early stages of development, brain assemblies have great potential for researching intricate neuronal circuitry and the causes of disease. Multiple brain-region organoids can be made more sophisticated by combining them, but there are still issues, such as the lack of an immune system, immature neuronal projections, and the requirement for vascularization to prevent necrosis [

103].

Organ-on-a-chip (OOC) and multi-organ-chip (MOC) technologies face several challenges despite their potential. A key issue is developing a universal blood-mimetic medium that supports diverse cell types, which becomes more complex in advanced MOCs [

104]. Additionally, the lack of standardized manufacturing protocols and materials limits reproducibility and scalability, making large-scale production difficult [

105]. Achieving physiologically relevant conditions requires precise control over organ size, inter-organ transport, and liquid-to-cell ratios to replicate dynamic interactions and responses accurately. (

Figure 3) Due to such complexity in the system, it has a high production cost and certain reproducibility issues. Despite these hurdles, OOC technology is advancing rapidly.

6. Conclusion

The integration of brain organoids, assembloids, and organ-on-a-chip technologies has redefined the landscape of neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disease modeling by offering human-specific, three-dimensional systems that capture key aspects of brain architecture, cellular diversity, and circuit functionality. Advances such as region-specific differentiation, vascularization strategies, microfluidic perfusion, and real-time electrophysiological monitoring have significantly enhanced the physiological relevance of these models, enabling detailed investigations into complex processes underlying disorders like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. The convergence of genetic engineering, biomaterials science, and high-throughput analysis platforms has further expanded the utility of these systems for mechanistic studies, drug discovery, and precision medicine applications.

Nevertheless, substantial technical challenges persist, including limited maturation, chronic cellular stress, absence of fully functional vasculature, and batch-to-batch variability. Addressing these limitations will require the development of standardized protocols, improved bio fabrication techniques, and integration of vascularized and immune components to more accurately recapitulate the in vivo microenvironment. As organoid and organ-on-a-chip technologies continue to evolve, their strategic refinement and interdisciplinary optimization will be critical for unlocking deeper mechanistic insights into human brain physiology, pathology, and therapeutic response with translational significance.

Authorship Contribution Statement

Soupayan Banerjee: Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, P. Chandu: Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision. M. Sarkar: Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization. T. K. Soni: Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization. F. Muhammad L: Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization. M. Saha: Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization. B. Chatterjee: Writing - Original Draft. U. Das: Validation, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

The writing of this review paper involved the use of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies only to enhance the clarity, coherence, and overall quality of the manuscript. The authors acknowledge the contributions of AI in the writing process while ensuring that the final content reflects the author's insights and interpretations of the literature. All interpretations and conclusions drawn in this manuscript are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The author(s) report no conflict of interest.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

References

- Bassett DS, Sporns O (2017) Network neuroscience. Nat Neurosci 20:353–364. [CrossRef]

- Insel TR (2010) Rethinking schizophrenia. Nature 468:187–193. [CrossRef]

- Marín O (2016) Developmental timing and critical windows for the treatment of psychiatric disorders. Nat Med 22:1229–1238. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, et al (2007) Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Adult Human Fibroblasts by Defined Factors. Cell 131:861–872. [CrossRef]

- Lancaster MA, Renner M, Martin C-A, et al (2013) Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature 501:373–379. [CrossRef]

- Di Lullo E, Kriegstein AR (2017) The use of brain organoids to investigate neural development and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 18:573–584. [CrossRef]

- Bassett AR (2017) Editing the genome of hiPSC with CRISPR/Cas9: disease models. Mamm Genome 28:348–364. [CrossRef]

- Amin ND, Paşca SP (2018) Building Models of Brain Disorders with Three-Dimensional Organoids. Neuron 100:389–405. [CrossRef]

- Quadrato G, Nguyen T, Macosko EZ, et al (2017) Cell diversity and network dynamics in photosensitive human brain organoids. Nature 545:48–53. [CrossRef]

- Kelava I, Lancaster MA (2016) Dishing out mini-brains: Current progress and future prospects in brain organoid research. Dev Biol 420:199–209. [CrossRef]

- Sloan SA, Andersen J, Pașca AM, et al (2018) Generation and assembly of human brain region–specific three-dimensional cultures. Nat Protoc 13:2062–2085. [CrossRef]

- Park SE, Georgescu A, Huh D (2019) Organoids-on-a-chip. Science 364:960–965. [CrossRef]

- Stiles J, Jernigan TL (2010) The Basics of Brain Development. Neuropsychol Rev 20:327–348. [CrossRef]

- Silbereis JC, Pochareddy S, Zhu Y, et al (2016) The Cellular and Molecular Landscapes of the Developing Human Central Nervous System. Neuron 89:248–268. [CrossRef]

- Dawson TM, Golde TE, Lagier-Tourenne C (2018) Animal models of neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Neurosci 21:1370–1379. [CrossRef]

- Eiraku M, Watanabe K, Matsuo-Takasaki M, et al (2008) Self-Organized Formation of Polarized Cortical Tissues from ESCs and Its Active Manipulation by Extrinsic Signals. Cell Stem Cell 3:519–532. [CrossRef]

- Qian X, Song H, Ming G (2019) Brain organoids: advances, applications and challenges. Development 146:dev166074. [CrossRef]

- Paşca SP (2019) Assembling human brain organoids. Science 363:126–127. [CrossRef]

- Das U, Chandramouli L, Uttarkar A, et al (2025) Discovery of natural compounds as novel FMS-like tyrosine kinase-3 (FLT3) therapeutic inhibitors for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia: An in-silico approach. Asp Mol Med 5:100058. [CrossRef]

- Trujillo CA, Gao R, Negraes PD, et al (2019) Complex Oscillatory Waves Emerging from Cortical Organoids Model Early Human Brain Network Development. Cell Stem Cell 25:558-569.e7. [CrossRef]

- Miura Y, Li M-Y, Birey F, et al (2020) Generation of human striatal organoids and cortico-striatal assembloids from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol 38:1421–1430. [CrossRef]

- Bagley JA, Reumann D, Bian S, et al (2017) Fused cerebral organoids model interactions between brain regions. Nat Methods 14:743–751. [CrossRef]

- Osaki T, Uzel SGM, Kamm RD (2020) On-chip 3D neuromuscular model for drug screening and precision medicine in neuromuscular disease. Nat Protoc 15:421–449. [CrossRef]

- Xiang Y, Tanaka Y, Patterson B, et al (2017) Fusion of Regionally Specified hPSC-Derived Organoids Models Human Brain Development and Interneuron Migration. Cell Stem Cell 21:383-398.e7. [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Ning X, Zhao F, et al (2024) Human organoids-on-chips for biomedical research and applications. Theranostics 14:788–818. [CrossRef]

- Huang D, Zhu X, Ye S, et al (2024) Tumour circular RNAs elicit anti-tumour immunity by encoding cryptic peptides. Nature 625:593–602. [CrossRef]

- Maoz BM, Herland A, FitzGerald EA, et al (2018) A linked organ-on-chip model of the human neurovascular unit reveals the metabolic coupling of endothelial and neuronal cells. Nat Biotechnol 36:865–874. [CrossRef]

- Vatine GD, Barrile R, Workman MJ, et al (2019) Human iPSC-Derived Blood-Brain Barrier Chips Enable Disease Modeling and Personalized Medicine Applications. Cell Stem Cell 24:995-1005.e6. [CrossRef]

- Nzou G, Wicks RT, Wicks EE, et al (2018) Human Cortex Spheroid with a Functional Blood Brain Barrier for High-Throughput Neurotoxicity Screening and Disease Modeling. Sci Rep 8:7413. [CrossRef]

- Skylar-Scott MA, Uzel SGM, Nam LL, et al (2019) Biomanufacturing of organ-specific tissues with high cellular density and embedded vascular channels. Sci Adv 5:eaaw2459. [CrossRef]

- Corrò C, Novellasdemunt L, Li VSW (2020) A brief history of organoids. Am J Physiol-Cell Physiol 319:C151–C165. [CrossRef]

- Shin H, Jeong S, Lee J-H, et al (2021) 3D high-density microelectrode array with optical stimulation and drug delivery for investigating neural circuit dynamics. Nat Commun 12:492. [CrossRef]

- Das U, Banerjee S, Sarkar M, et al (2024) Circular RNA vaccines: Pioneering the next-gen cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Pathog Ther S2949713224000892. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Lopez-Berestein G, Sood AK, Calin GA (2016) Profiling Long Noncoding RNA Expression Using Custom-Designed Microarray. In: Feng Y, Zhang L (eds) Long Non-Coding RNAs. Springer New York, New York, NY, pp 33–41.

- Wang Y, Chang RYK, Britton WJ, Chan H-K (2022) Advances in the development of antimicrobial peptides and proteins for inhaled therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 180:114066. [CrossRef]

- Benito-Kwiecinski S, Lancaster MA (2020) Brain Organoids: Human Neurodevelopment in a Dish. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 12:a035709. [CrossRef]

- Prager BC, Xie Q, Bao S, Rich JN (2019) Cancer Stem Cells: The Architects of the Tumor Ecosystem. Cell Stem Cell 24:41–53. [CrossRef]

- Kang UJ, Boehme AK, Fairfoul G, et al (2019) Comparative study of cerebrospinal fluid α-synuclein seeding aggregation assays for diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 34:536–544. [CrossRef]

- Yemini E, Lin A, Nejatbakhsh A, et al (2021) NeuroPAL: A Multicolor Atlas for Whole-Brain Neuronal Identification in C. elegans. Cell 184:272-288.e11. [CrossRef]

- Chortos A (2022) High current hydrogels: Biocompatible electromechanical energy sources. Cell 185:2653–2654. [CrossRef]

- Wu S, Wagner G (2021) Deep computational analysis details dysregulation of eukaryotic translation initiation complex eIF4F in human cancers. Cell Syst 12:907-923.e6. [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya M, Tachibana N, Nagao K, et al (2023) Organelle-selective click labeling coupled with flow cytometry allows pooled CRISPR screening of genes involved in phosphatidylcholine metabolism. Cell Metab 35:1072-1083.e9. [CrossRef]

- Shin AE, Giancotti FG, Rustgi AK (2023) Metastatic colorectal cancer: mechanisms and emerging therapeutics. Trends Pharmacol Sci 44:222–236. [CrossRef]

- Gleeson P, Cantarelli M, Marin B, et al (2019) Open Source Brain: A Collaborative Resource for Visualizing, Analyzing, Simulating, and Developing Standardized Models of Neurons and Circuits. Neuron 103:395-411.e5. [CrossRef]

- Ackerman SD, Perez-Catalan NA, Freeman MR, Doe CQ (2021) Astrocytes close a motor circuit critical period. Nature 592:414–420. [CrossRef]

- Ameen TB, Kashif SN, Abbas SMI, et al (2024) Unraveling Alzheimer’s: the promise of aducanumab, lecanemab, and donanemab. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatry Neurosurg 60:72. [CrossRef]

- Park J-C, Jang S-Y, Lee D, et al (2021) A logical network-based drug-screening platform for Alzheimer’s disease representing pathological features of human brain organoids. Nat Commun 12:280. [CrossRef]

- Jusop AS, Thanaskody K, Tye GJ, et al (2023) Development of brain organoid technology derived from iPSC for the neurodegenerative disease modelling: a glance through. Front Mol Neurosci 16:1173433. [CrossRef]

- Wray S (2021) Modelling neurodegenerative disease using brain organoids. Semin Cell Dev Biol 111:60–66. [CrossRef]

- Hofer M, Lutolf MP (2021) Engineering organoids. Nat Rev Mater 6:402–420. [CrossRef]

- Zheng L, Zhan Y, Wang C, et al (2024) Technological advances and challenges in constructing complex gut organoid systems. Front Cell Dev Biol 12:1432744. [CrossRef]

- Das U, Banerjee S, Sarkar M (2025) Bibliometric analysis of circular RNA cancer vaccines and their emerging impact. Vacunas 500391. [CrossRef]

- Huang S, Huang F, Zhang H, et al (2022) In vivo development and single-cell transcriptome profiling of human brain organoids. Cell Prolif 55:e13201. [CrossRef]

- Kathuria A, Lopez-Lengowski K, Vater M, et al (2020) Transcriptome analysis and functional characterization of cerebral organoids in bipolar disorder. Genome Med 12:34. [CrossRef]

- Brémond Martin C, Simon Chane C, Clouchoux C, Histace A (2021) Recent Trends and Perspectives in Cerebral Organoids Imaging and Analysis. Front Neurosci 15:629067. [CrossRef]

- Sandoval SO, Cappuccio G, Kruth K, et al (2024) Rigor and reproducibility in human brain organoid research: Where we are and where we need to go. Stem Cell Rep 19:796–816. [CrossRef]

- Smirnova L, Caffo BS, Gracias DH, et al (2023) Organoid intelligence (OI): the new frontier in biocomputing and intelligence-in-a-dish. Front Sci 1:1017235. [CrossRef]

- Wadan A-HS (2025) Organoid intelligence and biocomputing advances: Current steps and future directions. Brain Organoid Syst Neurosci J 3:8–14. [CrossRef]

- Mansour AA, Schafer ST, Gage FH (2021) Cellular complexity in brain organoids: Current progress and unsolved issues. Semin Cell Dev Biol 111:32–39. [CrossRef]

- Acharya P, Choi NY, Shrestha S, et al (2024) Brain organoids: A revolutionary tool for modeling neurological disorders and development of therapeutics. Biotechnol Bioeng 121:489–506. [CrossRef]

- Rauth S, Karmakar S, Batra SK, Ponnusamy MP (2021) Recent advances in organoid development and applications in disease modeling. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Rev Cancer 1875:188527. [CrossRef]

- Das U, Chanda T, Kumar J, Peter A (2024) Discovery of Natural MCL1 Inhibitors using Pharmacophore modelling, QSAR, Docking, ADMET, Molecular Dynamics, and DFT Analysis.

- Atamian A, Birtele M, Hosseini N, et al (2024) Human cerebellar organoids with functional Purkinje cells. Cell Stem Cell 31:39-51.e6. [CrossRef]

- Uzquiano A, Kedaigle AJ, Pigoni M, et al (2022) Proper acquisition of cell class identity in organoids allows definition of fate specification programs of the human cerebral cortex. Cell 185:3770-3788.e27. [CrossRef]

- Sidhaye J, Knoblich JA (2021) Brain organoids: an ensemble of bioassays to investigate human neurodevelopment and disease. Cell Death Differ 28:52–67. [CrossRef]

- Molnár Z, Clowry GJ, Šestan N, et al (2019) New insights into the development of the human cerebral cortex. J Anat 235:432–451. [CrossRef]

- Das U, Uttarkar A, Kumar J, Niranjan V (2025) In silico exploration natural compounds for the discovery of novel dnmt3a inhibitors as potential therapeutic agents for acute myeloid leukaemia. Silico Res Biomed 100006. [CrossRef]

- Camp JG, Badsha F, Florio M, et al (2015) Human cerebral organoids recapitulate gene expression programs of fetal neocortex development. Proc Natl Acad Sci 112:15672–15677. [CrossRef]

- Lu Y, Shiau F, Yi W, et al (2020) Single-Cell Analysis of Human Retina Identifies Evolutionarily Conserved and Species-Specific Mechanisms Controlling Development. Dev Cell 53:473-491.e9. [CrossRef]

- Zou W, Lv Y, Zhang S, et al (2024) Lysosomal dynamics regulate mammalian cortical neurogenesis. Dev Cell 59:64-78.e5. [CrossRef]

- Ziffra RS, Kim CN, Ross JM, et al (2021) Single-cell epigenomics reveals mechanisms of human cortical development. Nature 598:205–213. [CrossRef]

- Lu T, Wang M, Zhou W, et al (2024) Decoding transcriptional identity in developing human sensory neurons and organoid modeling. Cell 187:7374-7393.e28. [CrossRef]

- Saglam-Metiner P, Devamoglu U, Filiz Y, et al (2023) Spatio-temporal dynamics enhance cellular diversity, neuronal function and further maturation of human cerebral organoids. Commun Biol 6:173. [CrossRef]

- Giandomenico SL, Mierau SB, Gibbons GM, et al (2019) Cerebral organoids at the air–liquid interface generate diverse nerve tracts with functional output. Nat Neurosci 22:669–679. [CrossRef]

- Xue W, Li H, Xu J, et al (2024) Effective cryopreservation of human brain tissue and neural organoids. Cell Rep Methods 4:100777. [CrossRef]

- Jacob F, Schnoll JG, Song H, Ming G (2021) Building the brain from scratch: Engineering region-specific brain organoids from human stem cells to study neural development and disease. In: Current Topics in Developmental Biology.

- Susaimanickam PJ, Kiral FR, Park I-H (2022) Region Specific Brain Organoids to Study Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Int J Stem Cells 15:26–40. [CrossRef]

- Castiglione H, Vigneron P-A, Baquerre C, et al (2022) Human Brain Organoids-on-Chip: Advances, Challenges, and Perspectives for Preclinical Applications. Pharmaceutics 14:2301. [CrossRef]

- Saglam-Metiner P, Yildirim E, Dincer C, et al (2024) Humanized brain organoids-on-chip integrated with sensors for screening neuronal activity and neurotoxicity. Microchim Acta 191:71. [CrossRef]

- Zlokovic BV, Zlokovic BV, Apuzzo MLJ (1998) Strategies to Circumvent Vascular Barriers of the Central Nervous System. Neurosurgery 43:877–878. [CrossRef]

- Dunn KM, Nelson MT (2014) Neurovascular signaling in the brain and the pathological consequences of hypertension. Am J Physiol-Heart Circ Physiol 306:H1–H14. [CrossRef]

- Sweeney MD, Kisler K, Montagne A, et al (2018) The role of brain vasculature in neurodegenerative disorders. Nat Neurosci 21:1318–1331. [CrossRef]

- Mansour AA, Gonçalves JT, Bloyd CW, et al (2018) An in vivo model of functional and vascularized human brain organoids. Nat Biotechnol 36:432–441. [CrossRef]

- Vodyanik MA, Yu J, Zhang X, et al (2010) A Mesoderm-Derived Precursor for Mesenchymal Stem and Endothelial Cells. Cell Stem Cell 7:718–729. [CrossRef]

- Sun X-Y, Luo Z-G (2022) Vascularizing the brain organoids. J Mol Cell Biol 14:mjac040. [CrossRef]

- Shi Y, Sun L, Wang M, et al (2020) Vascularized human cortical organoids (vOrganoids) model cortical development in vivo. PLOS Biol 18:e3000705. [CrossRef]

- Kong D, Park KH, Kim D-H, et al (2023) Cortical-blood vessel assembloids exhibit Alzheimer’s disease phenotypes by activating glia after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell Death Discov 9:32. [CrossRef]

- Sun X-Y, Ju X-C, Li Y, et al (2022) Generation of vascularized brain organoids to study neurovascular interactions. eLife 11:e76707. [CrossRef]

- Patsch C, Challet-Meylan L, Thoma EC, et al (2015) Generation of vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Cell Biol 17:994–1003. [CrossRef]

- Morita R, Suzuki M, Kasahara H, et al (2015) ETS transcription factor ETV2 directly converts human fibroblasts into functional endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci 112:160–165. [CrossRef]

- Cakir B, Xiang Y, Tanaka Y, et al (2019) Engineering of human brain organoids with a functional vascular-like system. Nat Methods 16:1169–1175. [CrossRef]

- Kofman S, Sun X, Ogbolu VC, et al (2023) Vascularized Brain Assembloids with Enhanced Cellular Complexity Provide Insights into The Cellular Deficits of Tauopathy.

- Das U (2025) Emerging trends and research landscape of the tumor microenvironment in head-and-neck cancer: A comprehensive bibliometric analysis. Cancer Plus 0:025060008. [CrossRef]

- Bagchi S, Chhibber T, Lahooti B, et al (2019) In-vitro blood-brain barrier models for drug screening and permeation studies: an overview. Drug Des Devel Ther Volume 13:3591–3605. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Helm MW, Van Der Meer AD, Eijkel JCT, et al (2016) Microfluidic organ-on-chip technology for blood-brain barrier research. Tissue Barriers 4:e1142493. [CrossRef]

- Bhaduri A, Andrews MG, Mancia Leon W, et al (2020) Cell stress in cortical organoids impairs molecular subtype specification. Nature 578:142–148. [CrossRef]

- Short PJ, McRae JF, Gallone G, et al (2018) De novo mutations in regulatory elements in neurodevelopmental disorders. Nature 555:611–616. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Wang L, Guo Y, et al (2018) Engineering stem cell-derived 3D brain organoids in a perfusable organ-on-a-chip system. RSC Adv 8:1677–1685. [CrossRef]

- Marton RM, Miura Y, Sloan SA, et al (2019) Differentiation and maturation of oligodendrocytes in human three-dimensional neural cultures. Nat Neurosci 22:484–491. [CrossRef]

- Ormel PR, Vieira De Sá R, Van Bodegraven EJ, et al (2018) Microglia innately develop within cerebral organoids. Nat Commun 9:4167. [CrossRef]

- Lin Y-T, Seo J, Gao F, et al (2018) APOE4 Causes Widespread Molecular and Cellular Alterations Associated with Alzheimer’s Disease Phenotypes in Human iPSC-Derived Brain Cell Types. Neuron 98:1141-1154.e7. [CrossRef]

- Kim J, Koo B-K, Knoblich JA (2020) Human organoids: model systems for human biology and medicine. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 21:571–584. [CrossRef]

- Ene HM, Karry R, Farfara D, Ben-Shachar D (2023) Mitochondria play an essential role in the trajectory of adolescent neurodevelopment and behavior in adulthood: evidence from a schizophrenia rat model. Mol Psychiatry 28:1170–1181. [CrossRef]

- Sung JH, Wang YI, Narasimhan Sriram N, et al (2019) Recent Advances in Body-on-a-Chip Systems. Anal Chem 91:330–351. [CrossRef]

- Wang F, Liu Y, Fu C, et al (2021) Paper-Based Bipolar Electrode Electrochemiluminescence Platform for Detection of Multiple miRNAs. Anal Chem 93:1702–1708. [CrossRef]

- Lu X, Stepanov P, Yang W, et al (2019) Superconductors, orbital magnets and correlated states in magic-angle bilayer graphene. Nature 574:653–657. [CrossRef]

- Birey F, Andersen J, Makinson CD, et al (2017) Assembly of functionally integrated human forebrain spheroids. Nature 545:54–59. [CrossRef]

- Berg J, Sorensen SA, Ting JT, et al (2021) Human neocortical expansion involves glutamatergic neuron diversification. Nature 598:151–158. [CrossRef]

- Abud EM, Ramirez RN, Martinez ES, et al (2017) iPSC-Derived Human Microglia-like Cells to Study Neurological Diseases. Neuron 94:278-293.e9. [CrossRef]

- Wang YI, Abaci HE, Shuler ML (2017) Microfluidic blood–brain barrier model provides in vivo-like barrier properties for drug permeability screening. Biotechnol Bioeng 114:184–194. [CrossRef]

- Choi YJ, Heo K, Park HS, et al (2016) The resveratrol analog HS-1793 enhances radiosensitivity of mouse-derived breast cancer cells under hypoxic conditions. Int J Oncol 49:1479–1488. [CrossRef]

- Studer L, Vera E, Cornacchia D (2015) Programming and Reprogramming Cellular Age in the Era of Induced Pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell 16:591–600. [CrossRef]

- Lancaster MA, Knoblich JA (2014) Organogenesis in a dish: Modeling development and disease using organoid technologies. Science 345:1247125. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).