1. Introduction

Lung transplantation represents the standard therapy for end-stage lung disease; however, a persistent gap remains between the number of lung transplants each year and the increasing number of patients on the waiting list. Expanding the organ donor pool is therefore a major priority in lung transplantation. Despite efforts to increase donor availability, the utilisation rate of potential lung donors remains relatively low. Optimising donor lung management could improve lung utilisation rates in both donors after brain death (DBD) and donors after circulatory death (DCD), including both uncontrolled (uDCD) and controlled (cDCD) donation [

1,

2]. Currently, there is no widely accepted standardised protocol for the management of potential lung donors.

This narrative review aims to summarise current knowledge on lung management in donors across all categories (DBD, uDCD, and cDCD) with the goal of improving lung utilisation rates and addressing the ongoing shortage of transplantable lungs.

2. Materials and Methods

A systematic literature search was conducted in PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library using the keywords “lung transplantation and uncontrolled donation after circulatory death,” “lung transplantation and controlled donation after circulatory death,” and “lung transplantation and donors after brain death.” The search was limited to studies published in English and excluded case reports, animal studies, and studies lacking original data.

Studies were included if they investigated donor management strategies aimed at improving lung utilisation, such as protective ventilation strategies, lung recruitment manoeuvres, fluid management, hormonal resuscitation, and ex vivo lung perfusion (EVLP). The primary outcomes of interest were lung function, lung suitability for transplantation, and post-transplant complication rates.

Relevant data from the eligible studies were synthesised narratively to highlight best practices for lung preservation in DBD, uDCD, and cDCD donors.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Brain Death on Lung Physiology

3.1.1. Inflammatory Cascade and Its Consequences: “Double-Hit Model”

The impairment of lung function following brain death (BD) is primarily related to haemodynamic alterations that affect heart-lung interactions. The massive sympathetic nervous system activation triggered by BD increases left atrial pressure and pulmonary capillary pressure, resulting in pulmonary vasoconstriction and endothelial damage [

4]. Consequently, pulmonary capillary permeability increases, contributing to lung dysfunction [

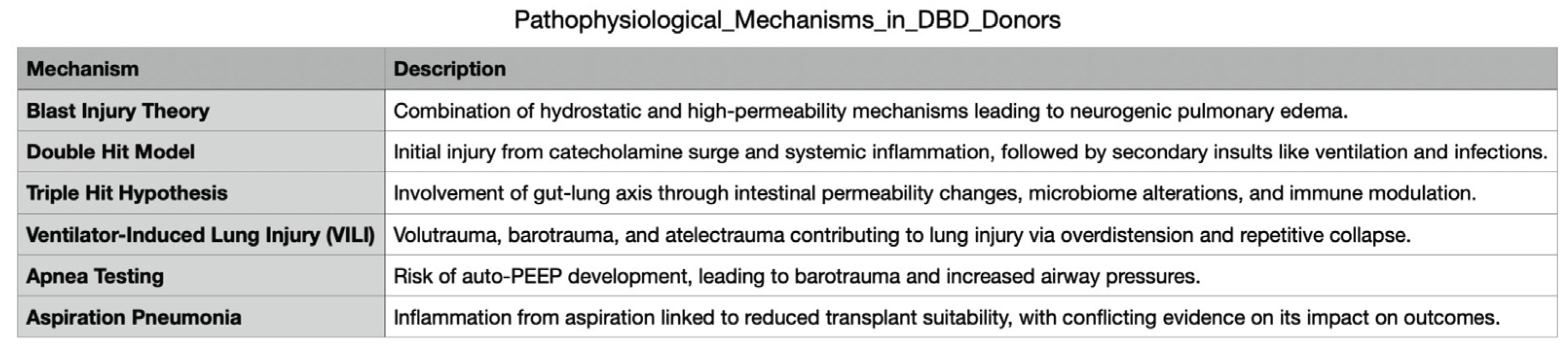

5]. These pathophysiological changes are explained by the so-called "blast injury theory," which proposes that a combination of hydrostatic and high-permeability mechanisms leads to the development of neurogenic pulmonary oedema (

Figure 1) [

6]. Additionally, the intense coronary vasoconstriction induced by the catecholamine storm, without a proportional increase in myocardial oxygen delivery, may result in sub-endocardial ischaemia, further impairing pulmonary function [

4,

5].

Recent evidence challenges the “blast injury theory," suggesting that systemic inflammation plays an additional and amplifying role in post-brain death pulmonary dysfunction. Following brain death, intracranial production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α, ICAM-1) increases, releasing inflammatory mediators into the systemic circulation [

6].

. Notably, DBD donors display significantly higher systemic inflammation compared to DCD donors, as evidenced by elevated cytokine plasma levels in pre-transplant samples. Specifically, IL-6 levels are higher in DBD donors, along with increased IL-10 and IL-8 7 [

3,

7]. Moreover, elevated TNF-α plasma levels in donors have been associated with a greater incidence of primary graft dysfunction post-transplantation [

7].

This intricate biochemical cascade following brainstem death has led to the formulation of the "double-hit model." The first hit is driven by the catecholamine surge and the systemic inflammatory response. This inflammatory environment renders the lung more vulnerable to subsequent injurious stimuli, constituting the second hit. Among these second-hit factors, mechanical ventilation plays a pivotal role. Particularly, the use of high tidal volumes to maintain normocapnia combined with inadequate positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) to correct hypoxemia can exacerbate lung injury. Additional contributing factors include infections, transfusions, and surgical interventions, all of which may worsen lung function in DBD donors. The interplay of these insults can create a vicious cycle of lung injury [

6]. Furthermore, the abnormal activation of the coagulation system due to the systemic inflammatory response leads to a prothrombotic state characterised by increased fibrin formation, reduced fibrinolysis, and heightened platelet activation. This prothrombotic condition promotes the formation of microthrombi within the donor lungs, potentially leading to further deterioration in lung function [

8].

Recently, a "triple-hit hypothesis" has been proposed, with the third hit represented by alterations in the gut-lung axis. In DBD donors, damage to the intestinal mucosa and increased intestinal permeability have been observed, leading to gut microbiota dysbiosis [

9]. Changes in gut microbiome composition appear to be linked to altered immune responses and airway homeostasis, potentially contributing to new or worsening lung injury [

10].

3.1.2. Effects of Mechanical Ventilation

The role of mechanical ventilation in worsening lung function in DBD donors can be summarised as follows:

a) The presence of pulmonary oedema and a pro-inflammatory environment in the DBD lung reduces its tolerance to the mechanical stress imposed by injurious ventilatory strategies. In particular, the use of high tidal volumes and high respiratory rates, combined with a low PaO

2/FiO

2 ratio, has been identified as an independent predictor of early acute lung injury (ALI) within the first 72 hours of mechanical ventilation. These factors, along with major underlying risk factors such as aspiration, pneumonia, and lung contusion, as well as certain treatment variables, increase susceptibility to lung injury in patients with severe brain injury [

11].

b) The three primary mechanisms contributing to the development of ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI) include volutrauma and barotrauma from excessive lung overdistension during mechanical ventilation, increasing alveolar-capillary permeability. Another mechanism is atelectrauma, which occurs due to the repeated recruitment and derecruitment of collapsed alveoli, further exacerbating lung injury. Additionally, biotrauma plays a crucial role, as mechanical ventilation induces an inflammatory response, amplifying pulmonary dysfunction and further damaging tissue [

6].

c) Apnoea testing may represent an additional harmful stimulus for lung injury, particularly when performed using passive air insufflation inside the endotracheal tube, which can lead to auto-PEEP. The presence of auto-PEEP and air trapping is well known to increase the risk of barotrauma and further compromise lung function [

12]. In patients with severe traumatic brain injury, the incidence of ALI is notably high, estimated at 20–30%. Its occurrence follows a bimodal distribution, with an early peak around days 2–3 after the initiation of mechanical ventilation and a late peak around days 7–8, the latter often associated with the development of concurrent pneumonia [

6].

3.1.2. Aspiration Pneumonia

Aspiration pneumonia is a common concern in potential lung donors and is typically assessed through bronchoscopy or CT imaging, particularly by identifying infiltrates in the right lower lobe. Recent studies have proposed the measurement of bile acids in airway bronchial wash samples as a potential marker of aspiration, with higher levels correlating with lower transplant suitability, reduced performance during EVLP, and worse post-transplant outcomes [

13]. Due to concerns that aspiration may negatively impact recipient allograft function, the use of lungs from donors affected by aspiration is generally discouraged. However, conflicting evidence exists. Nunley et al. reported that the presence of bile salts in donor lungs does not significantly compromise allograft function and does not increase mortality within the first year post-transplantation [

14]. Given these discrepancies, further research is needed to establish clear recommendations regarding the transplant suitability of lungs affected by aspiration.

3.2. Management of the DBD Lung

3.2.1. Protective Mechanical Ventilation

A lung management strategy in DBD donors can be established based on available evidence and pathophysiological mechanisms, as summarised in

Figure 2.

The adoption of a lung-protective ventilatory strategy is now considered essential, as it helps prevent alveolar overstretch and end-expiratory collapse while promoting alveolar recruitment and maintaining lung integrity. A protective ventilatory approach, characterised by tidal volumes of 6–8 mL/kg of predicted body weight, PEEP of 8–10 cm H

2O, apnea tests performed using positive airway pressure, a closed circuit for airway suction, and recruitment manoeuvres performed by doubling ventilation with low tidal volumes for 10 breaths after any disconnection, has been shown to increase the number of lung donors meeting eligibility criteria for transplantation compared to a conventional ventilatory strategy (which involves tidal volumes of 10–12 mL/kg PBW, PEEP of 3–5 cmH

2O, apnea tests performed by ventilator disconnection, and a closed circuit for airway suction) [

15]. The optimal PEEP level in lung donors remains uncertain. The Spanish consensus document on lung donor management recommends a minimum PEEP of 5 cm H

2O, though a value of ≥8 cm H

2O is suggested as ideal [

16].

Meyfroidt et al. have proposed a protective ventilatory strategy bundle, which includes a tidal volume of 6–8 mL/kg PBW, PEEP of 8–10 cm H

2O, a closed circuit for tracheal suction, alveolar recruitment manoeuvres after any disconnection, and the use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) during apnoea testing. This approach has been shown to increase the number of eligible and transplanted lungs without negatively affecting the procurement of other organs [

4].

To prevent oxygen toxicity, the minimum FiO

2 necessary to maintain a PaO

2 above 100 mmHg should be used. Additionally, respiratory targets should include a physiological pH (7.35–7.45), oxygen saturation (SpO

2) above 95%, and partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO

2) between 35–40 mmHg [

4].

3.2.2. Recruitment Manoeuvres

Recruitment manoeuvres should be routinely performed in donors when PaO

2/FiO

2 remains below 300 mmHg, or in the presence of atelectasis or pulmonary oedema of any origin [

17].

Currently, one of the most widely adopted ventilatory protocols for DBD donors is the one proposed by Minambres et al. in 2014, which includes apnoea testing with the ventilator in CPAP mode, mechanical ventilation with PEEP set between 8 and 10 cm H

2O, and tidal volumes of 6–8 mL/kg. Additionally, this protocol recommends performing recruitment manoeuvres once per hour and after any disconnection from the ventilator, as well as alveolar recruitment through controlled ventilation with decremental PEEP [

18].

3.2.3. Fluid Strategy in Potential Lung Donors

Donor management guidelines emphasise the importance of preventing or immediately correcting hypovolaemia to maintain adequate organ perfusion and ensure the viability of transplantable organs. Euvolemia is the primary therapeutic goal, achieved through volume replacement therapy, in which isotonic crystalloid solutions are the preferred choice [

4,

19]. Among these, balanced salt solutions, such as Ringer’s lactate, may be superior to normal saline, as they do not induce hyperchloraemic acidosis [

19].

Conversely, starch-based synthetic colloids should be avoided due to their adverse effects in critically ill patients especially on renal epithelial cells, which may contribute to early graft dysfunction in transplanted kidneys [

4,

19].

It has long been recognised that when lungs are considered for transplantation, fluid administration should be carefully controlled [

20]. Maintaining a neutral or slightly negative fluid balance, achieved through judicious administration of crystalloids and diuretics, is associated with improved oxygenation and better lung donor outcomes [

1]. Tight regulation of fluid status is essential to prevent pulmonary oedema while ensuring adequate systemic perfusion [

2]. In this regard, restrictive fluid management strategies have been shown to enhance lung graft harvesting [

19].

Similarly, donor blood transfusion has been identified as a potential risk factor for primary graft dysfunction, likely due to mechanisms similar to those of transfusion-related acute lung injury [

2]. However, there are no current universal recommendations on transfusion targets in donor management [

4].

3.2.4. Bronchoscopy

Fiberoptic bronchoscopy is an essential tool in assessing lung suitability in potential donors [

2,

18]. Bronchoscopic evaluation allows confirmation of airway integrity and anatomy, which is crucial for successful surgical anastomosis of the major bronchi. Additionally, it facilitates the exclusion of aspiration of gastric contents, neoplasia, or foreign materials in the airways and enables the screening of potentially harmful microorganisms in respiratory secretions. However, airway erythema or secretions alone do not preclude organ retrieval, and bronchoalveolar lavage should be routinely performed to guide antimicrobial treatment for lower respiratory tract infections and improve oxygenation by removing airway obstructions [

1,

2,

18,

21].

Bronchoscopy at ICU admission is recommended for potential lung donors, as well as for critically ill patients when aspiration pneumonia is suspected. Patients with acute brain injury requiring mechanical ventilation are at high risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), and this protocol could potentially be extended to DBD donors, although further studies are needed [

22].

According to current literature, lungs from donors colonised with multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria can be safely transplanted, provided that recipients receive prompt, preventive, and tailored antibiotic therapy, including both systemic and nebulised antibiotics [

23,

24]. However, caution is advised in cases of MDR Klebsiella pneumoniae, as active infection with MDR organisms, invasive fungal infections, or mycobacterial infections remains a relative contraindication to lung transplantation. In contrast, active Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection is considered an absolute contraindication [

2,

24]. Donor bacteremia or sepsis should not be regarded as an absolute contraindication to organ donation unless strongly supported by microbiological and imaging evidence of uncontrolled infection. In such cases, lungs may still be considered for transplantation if appropriate antibiotic therapy has been administered for at least 48 hours prior to procurement [

2,

25].

3.2.5. Endotracheal Tube Management and Imaging

To prevent lung derecruitment, clamping the endotracheal tube (ETT) is a common practice in many transplant centres. ETT clamping at end-inspiration, with tidal volume reduced by half, can help minimise airway pressure loss under PEEP and reduce the risk of high alveolar pressures upon ventilator reconnection [

26]. Among available methods, the Extra Corporeal Membrane Oxygenation clamp has been identified as the most effective in maintaining alveolar recruitment and improving oxygenation. For this reason, endotracheal tube clamping is recommended in potential DBD lung donors [

27].

In terms of lung imaging, a clear chest X-ray is considered a prerequisite for donor lung acceptability. However, an abnormal chest X-ray alone should not exclude a lung from recovery, as it may still be suitable for transplantation. Chest X-rays are useful in estimating total lung capacity and detecting vascular congestion, oedema, infiltrates, and contusions, which may indicate the need for further imaging, such as a CT scan. Current practices in the USA and EU involve performing at least one CT scan to assess donor lungs and identify abnormalities not visible on chest X-ray [

2].

3.2.6. PaO2/FiO2 Ratio and the "40-100 Test" in Donor Lung Assessment

The PaO2/FiO2 ratio is a well-validated criterion in donor scoring systems and plays a crucial role in assessing lung suitability for transplantation. To evaluate lung function, each DBD donor should undergo the "40-100 test," which involves comparing PaO2/FiO2 ratios obtained from two different arterial blood gas analyses. The first sample is taken at FiO2 40% (representing the basal oxygenation status), while the second is collected at FiO2 100% (reflecting maximal oxygenation).

The rationale behind this test is to detect and quantify the presence of an intrapulmonary shunt, which represents a significant functional impairment in ALI. Shunting occurs when pulmonary blood flow bypasses non-ventilated alveoli, leading to impaired oxygenation despite increased inspired oxygen concentration. The 40-100 test helps to unmask this condition, providing critical information for lung donor evaluation and guiding the decision-making process regarding lung suitability for transplantation.

3.2.7. Pronation

Atelectasis is one of the primary reversible causes of hypoxemia following brain death. Ventilation in the prone position has been shown to effectively reverse atelectasis and rapidly improve oxygenation in hypoxic DBD donors [

28].

In DBD donors, atelectasis often develops due to the absence of spontaneous respiration, cough reflex, and respiratory drive, leading to ventilation-perfusion mismatch and hypoxemia. Additional donor-related risk factors, including mechanical ventilation, prolonged supine positioning, and obesity, further contribute to atelectasis [

29]. To counteract this, aggressive lung management strategies incorporating recruitment manoeuvres, bronchoscopy, chest percussion, and lung-protective ventilation can be employed to improve donor lung suitability for transplantation.

However, in cases in which severe haemodynamic instability, abdominal injuries, or multiple trauma are absent, prone positioning may not be an option to be carefully considered [

29]. As an alternative, lateral rotation therapy—which involves positioning the donor intermittently or continuously from side to side using a programmable bed—may be considered.

In DBD donors, the implementation of a rotational positioning protocol has been shown to significantly increase the PaO

2/FiO

2 ratio and improve the rate of successful lung donations, making it a safer and more feasible alternative when the donor is haemodynamically unstable [

30].

3.3. Lung Transplantation from Donors After Controlled Cardiac Death (cDCD)

According to the Maastricht classification, class III cDCD refers to patients for whom the withdrawal of life support is a planned decision based on diagnostic and prognostic considerations. These donors are commonly referred to as controlled DCD donors [

31].

Current evidence suggests that lung transplant recipients from cDCD donors experience similar outcomes to those receiving lungs from DBD donors, both in terms of survival rates and graft function [

32,

33].

3.3.1. Lung Injury in cDCD—Potential Mechanisms

3.3.1.1. Warm Ischaemia

Warm ischaemia is defined as the time interval from the cessation of circulation until cold perfusion is initiated. During this period, pulmonary blood vessels remain filled with warm, non-circulating blood, which can form a thrombus within the lung vasculature. This process contributes to increased vascular resistance, reduced vascular compliance, and impaired gas exchange, potentially affecting lung viability for transplantation [

32,

34].

3.3.1.2. Prolonged Mechanical Ventilation

In cDCD donors, the overall period of mechanical ventilation is typically longer compared to DBD donors, regardless of the underlying cause of death [

35]. While prolonged ventilation alone is not an exclusion criterion for lung donation [

21], cDCD donors are considered at higher risk for complications related to extended mechanical ventilation, including VILI and VAP.

Prolonged hospitalisation also represents an additional risk factor due to prolonged intensive care procedures, increasing susceptibility to infections [

14]. However, an important distinction exists: unlike DBD donors, cDCD donors do not experience the inflammatory cascade triggered by brain death. The absence of systemic inflammatory mediators may actually be advantageous for lung transplantation, potentially reducing the severity of ischaemia-reperfusion injury and improving post-transplant graft function [

36].

3.4. Management of Lungs from cDCD

3.4.1. Protective Mechanical Ventilation

A key difference between death following cardiac arrest after life support withdrawal (cDCD) and death due to neurological criteria (DBD) is the longer period typically spent before the decision to withdraw life support in cDCD donors. This extended period offers an opportunity to optimise lung recovery from concomitant injuries and enhance the effects of protective ventilation strategies, potentially improving organ suitability for transplantation. However, limited literature exists on the specific management of cDCD donor lungs, though the principles of protective mechanical ventilation remain similar to those applied in DBD donors.

Beyond the pre-mortem phase, mechanical ventilation remains crucial even post-mortem, as ventilated lungs can better tolerate prolonged circulatory arrest while maintaining cellular viability. This situation is made possible by passive oxygen diffusion through the alveolar wall, which continues to provide oxygen to pulmonary epithelial cells even after circulatory arrest [

36].

To minimise infectious risks, general recommendations for donor management include performing blood cultures and respiratory secretion Gram stains at organ retrieval. In cases of active bacterial infections, antimicrobial therapy should be administered for at least 48 hours before procurement to optimise lung suitability [

37].

3.4.2. Recruitment Manoeuvres

cDCD donors can benefit from applying recruitment manoeuvres and tend to tolerate them well, similarly to DBD donors. A recent experimental study by Niman et al. demonstrated that recruitment manoeuvres in the absence of circulation may protect against atelectasis. These findings suggest that inflation procedures in cDCD donors can be safely executed even after cardiac arrest, potentially optimising lung recruitment and preservation [

38].

3.4.3. Pronation

In cases in which oxygenation parameters remain unsatisfactory, DCD donors might theoretically benefit from prone positioning, although no clinical data currently support this approach. As an alternative, lateral positioning could serve as a viable option for improving lung aeration and reducing atelectasis.

Experimental evidence from animal models suggests that prone positioning during warm ischaemia can significantly enhance lung quality and graft preservation, even under conditions of absent perfusion and ventilation. These findings indicate a potential application of this technique in human DCD donors, though further studies are needed to confirm its clinical feasibility [

39].

3.4.4. Bronchoscopy

The rationale for bronchoscopy in cDCD donors is similar to that in DBD donors, primarily to exclude major anatomical abnormalities, detect macroscopic aspiration, and identify potentially harmful pathogens in respiratory secretions. Bronchoscopy should be conducted as early as possible to allow sufficient time for diagnostic results to become available and to adjust antimicrobial therapy if necessary. However, at a minimum, bronchoscopy should be performed at the time the donor enters the operating room to ensure adequate airway assessment and preparation for lung procurement [

33].

3.4.5. Endotracheal Tube Management

The practice of clamping the ETT to prevent lung derecruitment and monitoring cuff pressure to minimise aspiration is advisable in DCD donors. This strategy should be implemented not only after cardiac arrest but also throughout the entire ICU care period to optimise lung preservation. Following the declaration of death, the ETT should remain in place and be inspected to ensure it remains inflated. If necessary, re-insertion may be performed to facilitate lung ventilation and reduce aspiration risk. Once the donor reaches the operating room, they should be reconnected to the ventilator, and mechanical ventilation should be resumed to optimise lung function before procurement [

33].

3.5. uDCD

uDCD represents a valuable source of donor lungs, and since Steen’s 2001 landmark case in Sweden, lungs from uDCD donors have been successfully transplanted in several European countries, including France, the Netherlands, Spain, and Italy, with promising outcomes [

40]

. The lung’s unique physiology allows it to tolerate periods of circulatory arrest, as it does not rely solely on blood perfusion for aerobic metabolism but rather on passive oxygen diffusion through the alveoli [

41]. Unlike other organs, the lung has relatively low metabolic demands and retains a local oxygen reserve within the alveoli. Egan et al. [

42] experimentally demonstrated the feasibility of transplanting donor lungs after cardiac arrest with an absence of circulation for up to two hours. In contrast to brain-dead and controlled DCD donors, lung function in uDCD donors cannot be assessed before death, though viability can be effectively evaluated post-mortem using EVLP. Valenza et al. [

43] reported in 2016 that lung was preserved in uDCD donors through recruitment manoeuvres, CPAP, and protective mechanical ventilation, followed by EVLP. In contrast, the Spanish experience favoured lung maintenance via topical cooling. The rationale behind these strategies is supported by experimental models, which have identified the prevention of alveolar collapse as a critical factor in mitigating reperfusion injury, independent of continuous oxygen supply [

43,

44]. While in situ lung cooling may provide superior protection, its application in uDCD settings is logistically challenging and time-consuming. Conversely, the "protective ventilation technique" is simpler, more widely applicable, and could facilitate the broader use of uDCD lung donors [

40]. To date, clinical evidence regarding lung transplantation following protective ventilation as a preservation strategy remains limited but encouraging. All reported protocols include a witnessed cardiac arrest as an inclusion criterion, with notable differences in preservation times (240 vs. 180 minutes) and donor age thresholds (<55 years in Spanish protocols and <65 years in Toronto protocols) [

45,

46,

47,

48]. Despite these protocol variations, uDCD lungs have yielded promising transplant outcomes, and further optimisation of EVLP techniques may enhance their utilisation, potentially expanding the available donor pool.

4. Discussion

There is a clinical need to improve the utilisation rate from donors. In the absence of a standardised and widely accepted protocol on lung maintenance and considering available evidence and our own experience, we have elaborated a strategy according to the different types of donor as depicted in

Figure 1.

The optimisation of lung donor management is crucial to maximising graft viability and expanding the available donor pool. Each type of donation—DBD, cDCD, and uDCD—presents distinct physiological challenges that require tailored preservation strategies. While DBD donors allow for controlled interventions from ICU admission, cDCD donors require a delicate balance between ventilatory support and ischaemia prevention before the withdrawal of life support. uDCD donors, on the other hand, undergo a period of uncontrolled ischaemia, necessitating post-mortem assessment and rescue strategies such as EVLP. In all cases, a structured planned approach incorporating bronchoscopy, positioning strategies, and infection surveillance plays a fundamental role in optimising lung function and ensuring transplant success.

While protective ventilation and recruitment manoeuvres should be performed in all types of donors, there are differences among the various donor types.

In potential DBD lung donors, bronchoscopy should be performed upon ICU admission to assess airway integrity and clear secretions. Protective ventilation should be initiated early to prevent alveolar damage and atelectasis, with adherence to standardised protocols where feasible. Given the high risk of VAP, routine microbiological surveillance should be implemented to enable early infection detection and guide targeted antimicrobial therapy. Prone positioning may aid in lung recruitment, though its feasibility should be carefully evaluated considering haemodynamic stability. If contraindicated, lateral rotation therapy may serve as an alternative. All interventions should be integrated into an organised donor management strategy to optimise lung function before procurement.

In potential cDCD donors, serial bronchoscopy should be carefully assessed and lateral positioning considered to facilitate lung recruitment and secretion clearance. Before death certification, optimising lung function remains a priority, as prolonged ventilatory support increases the risk of atelectasis and ischaemia. Prone positioning has demonstrated benefits in experimental models, improving oxygenation and mitigating ischaemic injury, suggesting its potential role in clinical practice [

39]. Bronchoscopy plays a fundamental role in airway evaluation, aspiration prevention, and microbiological surveillance, and should be performed early, ideally before procurement

33. Infection control strategies require routine blood cultures and respiratory secretion analysis, with antimicrobial therapy reserved for confirmed infections [

37]. A structured donor management approach integrating positioning strategies, bronchoscopy, and infection surveillance is critical to ensuring optimal lung viability while minimising unnecessary interventions.

The management of uDCD donor lungs is complex due to uncontrolled warm ischaemia and the need for post-mortem viability assessment. Before death certification, minimising alveolar collapse may improve outcomes, while bronchoscopy at retrieval helps assess airway integrity [

41,

43]. Microbiological surveillance is crucial, with antimicrobial therapy guided by post-procurement findings [

43]. After death certification, preservation strategies vary, with protective ventilation and topical cooling both employed. EVLP enables functional graft assessment and optimisation. Proper endotracheal tube management and lung recruitment remain essential to maximising uDCD lung viability [

43].

5. Conclusions

Potential lung DBD donors benefit from the ability to implement lung-protective strategies early, minimising ischaemia and optimising oxygenation before procurement. cDCD donors introduce challenges due to the need for lung protection during the withdrawal phase, requiring a careful balance between recruitment and preventing prolonged ventilatory exposure. In contrast, uDCD donors face the greatest ischaemic burden, making rapid retrieval and post-mortem assessment critical. Despite these differences, incorporating all three types of lung donation into clinical practice significantly expands the donor pool. The growing success of EVLP has further increased the feasibility of utilising lungs from cDCD and uDCD donors, reinforcing the importance of a comprehensive donor management strategy that integrates all available sources to meet the increasing demand for lung transplantation.

Intensive care strategies for lung maintenance are essential to improving lung suitability for transplantation and must account for the distinct pathophysiological mechanisms of lung injury in each type of donor. In DBD and cDCD donors, lung injury prevention is paramount, with infection surveillance and protective ventilation serving as fundamental components that should be initiated upon ICU admission. Bronchoscopy should be a mandatory practice in all patients with acute cerebral lesions, particularly those at high risk for brain death, and should be prioritised when aspiration pneumonia is suspected. In uDCD, where warm ischaemia is unavoidable, rapid lung retrieval and post-mortem assessment, including EVLP, are critical to maximising graft viability. A comprehensive and tailored approach to each donor type is essential to expanding the lung donor pool and improving transplant outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.F. and C.L.; methodology, F.F. and C.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.P., C.L. and F.F.; writing—review and editing, D.M., C.B., C.C., F.D.R.G., S.S., L.L., E.B., D.B., C.I., F.M., AP.; supervision, A.P., S.S.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DBD |

Donor after brain death |

| DCD |

Donor after circulatory death |

| EVLP |

Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion |

References

- Courtwright, A.; Cantu, E. Evaluation and Management of the Potential Lung Donor. Clin Chest Med. 2017 Dec;38(4):751-759. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Arjuna, A.; Mazzeo, A.T.; Tonetti, T.; Walia, R.; Mascia, L. Management of the Potential Lung Donor. Thorac Surg Clin. 2022 May;32(2):143-151. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, C.H.; Anraku, M.; Cypel, M.; Sato, M.; Yeung, J.; Gharib, S.A.; Pierre, A.F.; de Perrot, M.; Waddell, T.K.; Liu, M.; Keshavjee, S. Transcriptional signatures in donor lungs from donation after cardiac death vs after brain death: a functional pathway analysis. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011 Mar;30(3):289-98. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyfroidt, G.; Gunst, J.; Martin-Loeches, I.; Smith, M.; Robba, C.; Taccone, F.S.; Citerio, G. Management of the brain-dead donor in the ICU: general and specific therapy to improve transplantable organ quality. Intensive Care Med. 2019 Mar;45(3):343-353. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Smith, M. Physiologic changes during brain stem death--lessons for management of the organ donor. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004 Sep;23(9 Suppl):S217-22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascia, L. Acute lung injury in patients with severe brain injury: a double hit model. Neurocrit Care. 2009 Dec;11(3):417-26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandiumenge, A.; Bello, I.; Coll-Torres, E.; Gomez-Brey, A.; Franco-Jarava, C.; Miñambres, E.; Pérez-Redondo, M.; Mosteiro, F.; Sánchez-Moreno, L.; Crowley, S.; Fieira, E.; Suberviola, B.; Mazo, C.A.; Agustí, A.; Pont, T. Systemic Inflammation Differences in Brain-vs. Circulatory-Dead Donors: Impact on Lung Transplant Recipients. Transpl Int. 2024 Jun 3;37:12512. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lisman, T.; Leuvenink, H.G.; Porte, R.J.; Ploeg, R.J. Activation of hemostasis in brain dead organ donors: an observational study. J Thromb Haemost. 2011 Oct;9(10):1959-65. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hang, C.H.; Shi, J.X.; Li, J.S.; Wu, W.; Yin, H.X. Alterations of intestinal mucosa structure and barrier function following traumatic brain injury in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2003 Dec;9(12):2776-81. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ziaka, M.; Exadaktylos, A. Pathophysiology of acute lung injury in patients with acute brain injury: the triple-hit hypothesis. Crit Care. 2024 Mar 7;28(1):71. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mascia, L.; Zavala, E.; Bosma, K.; Pasero, D.; Decaroli, D.; Andrews, P.; Isnardi, D.; Davi, A.; Arguis, M.J.; Berardino, M.; Ducati, A. Brain IT group. High tidal volume is associated with the development of acute lung injury after severe brain injury: an international observational study. Crit Care Med. 2007 Aug;35(8):1815-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denny, J.T.; Burr, A.; Tse, J.; Denny, J.E.; Chyu, D.; Cohen, S.; Patel, A.N. A new technique for avoiding barotrauma-induced complications in apnea testing for brain death. J Clin Neurosci. 2015 Jun;22(6):1021-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramendra, R.; Sage, A.T.; Yeung, J.; Fernandez-Castillo, J.C.; Cuesta, M.; Aversa, M.; Liu, M.; Cypel, M.; Keshavjee, S.; Martinu, T. Triaging donor lungs based on a microaspiration signature that predicts adverse recipient outcome. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2023 Apr;42(4):456-465. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunley, D.R.; Gualdoni, J.; Ritzenthaler, J.; Bauldoff, G.S.; Howsare, M.; Reynolds, K.G.; van Berkel, V.; Roman, J. Evaluation of Donor Lungs for Transplantation: The Efficacy of Screening Bronchoscopy for Detecting Donor Aspiration and Its Relationship to the Resulting Allograft Function in Corresponding Recipients. Transplant Proc. 2023 Sep;55(7):1487-1494. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascia, L.; Pasero, D.; Slutsky, A.S.; Arguis, M.J.; Berardino, M.; Grasso, S.; Munari, M.; Boifava, S.; Cornara, G.; Della Corte, F.; Vivaldi, N.; Malacarne, P.; Del Gaudio, P.; Livigni, S.; Zavala, E.; Filippini, C.; Martin, E.L.; Donadio, P.P.; Mastromauro, I.; Ranieri, V.M. Effect of a lung protective strategy for organ donors on eligibility and availability of lungs for transplantation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010 Dec 15;304(23):2620-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo. Organización Nacional de Trasplantes. Protocolo de manejo del donante torácico: estrategias para mejorar el aprovechamiento de órganos. Available at: http://www.ont.es/infesp/ DocumentosDeConsenso/donantetoracico.pdf. Accessed June 2013.

- Solidoro, P.; Schreiber, A.; Boffini, M.; Braido, F.; Di Marco, F. Improving donor lung suitability: from protective strategies to ex-vivo reconditioning. Minerva Med. 2016 Jun;107(3 Suppl 1):7-11. [PubMed]

- Miñambres, E.; Coll, E.; Duerto, J.; Suberviola, B.; Mons, R.; Cifrian, J.M.; Ballesteros, M.A. Effect of an intensive lung donor-management protocol on lung transplantation outcomes. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014 Feb;33(2):178-84. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, L. Brain death and care of the organ donor. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2016 Apr-Jun;32(2):146-52. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pennefather, S.H.; Bullock, R.E.; Dark, J.H. The effect of fluid therapy on alveolar arterial oxygen gradient in brain-dead organ donors. Transplantation. 1993 Dec;56(6):1418-22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, U.; Rahulan, V.; Kumar, P.; Dutta, P.; Attawar, S. Donor lung management: Changing perspectives. Lung India. 2021 Sep-Oct;38(5):466-473. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dahyot-Fizelier, C.; Lasocki, S.; Kerforne, T.; Perrigault, P.F.; Geeraerts, T.; Asehnoune, K.; Cinotti, R.; Launey, Y.M.; Cottenceau, V.; Laffon, M.; Gaillard, T.; Boisson, M.; Aleyrat, C.; Frasca, D.; Mimoz, O. PROPHY-VAP Study Group and the ATLANREA Study Group. Ceftriaxone to prevent early ventilator-associated pneumonia in patients with acute brain injury: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, assessor-masked superiority trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2024 May;12(5):375-385. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunsow, E.; Los-Arcos, I.; Martin-Gómez, M.T.; Bello, I.; Pont, T.; Berastegui, C.; Ferrer, R.; Nuvials, X.; Deu, M.; Peghin, M.; González-López, J.J.; Lung, M.; Román, A.; Gavaldà, J.; Len, O. Donor-derived bacterial infections in lung transplant recipients in the era of multidrug resistance. J Infect. 2020 Feb;80(2):190-196. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulqawi, R.; Saleh, R.A.; Alameer, R.M.; Aldakhil, H.; AlKattan, K.M.; Almaghrabi, R.S.; Althawadi, S.; Hashim, M.; Saleh, W.; Yamani, A.H.; Al-Mutairy, E.A. Donor respiratory multidrug-resistant bacteria and lung transplantation outcomes. J Infect. 2024 Feb;88(2):139-148. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotloff, R.M.; Blosser, S.; Fulda, G.J.; Malinoski, D.; Ahya, V.N.; Angel, L.; Byrnes, M.C.; DeVita, M.A.; Grissom, T.E.; Halpern, S.D.; Nakagawa, T.A.; Stock, P.G.; Sudan, D.L.; Wood, K.E.; Anillo, S.J.; Bleck, T.P.; Eidbo, E.E.; Fowler, R.A.; Glazier, A.K.; Gries, C.; Hasz, R.; Herr, D.; Khan, A.; Landsberg, D.; Lebovitz, D.J.; Levine, D.J.; Mathur, M.; Naik, P.; Niemann, C.U.; Nunley, D.R.; O'Connor, K.J.; Pelletier, S.J.; Rahman, O.; Ranjan, D.; Salim, A.; Sawyer, R.G.; Shafer, T.; Sonneti, D.; Spiro, P.; Valapour, M.; Vikraman-Sushama, D.; Whelan, T.P. Society of Critical Care Medicine/American College of Chest Physicians/Association of Organ Procurement Organizations Donor Management Task Force. Management of the Potential Organ Donor in the ICU: Society of Critical Care Medicine/American College of Chest Physicians/Association of Organ Procurement Organizations Consensus Statement. Crit Care Med. 2015 Jun;43(6):1291-325. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulleri, E.; Fusi, C.; Bambi, S.; Pisani, L.; Galesi, A.; Rizzello, E.; Lucchini, A.; Merlani, P.; Pagnamenta, A. Efficacy of endotracheal tube clamping to prevent positive airways pressure loss and pressure behavior after reconnection: a bench study. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2023 Jun 30;11(1):36. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Turbil, E.; Terzi, N.; Schwebel, C.; Cour, M.; Argaud, L.; Guérin, C. Does endo-tracheal tube clamping prevent air leaks and maintain positive end-expiratory pressure during the switching of a ventilator in a patient in an intensive care unit? A bench study. PLoS One. 2020 Mar 11;15(3):e0230147. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Marklin, G.F.; O'Sullivan, C.; Dhar, R. Ventilation in the prone position improves oxygenation and results in more lungs being transplanted from organ donors with hypoxemia and atelectasis. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021 Feb;40(2):120-127. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, E.; Jang, J.; Cho, W.H.; Kim, D.; Yeo, H.J. Successful lung transplantation after prone positioning in an ineligible donor: a case report. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021 Sep;69(9):1352-1355. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mendez, M.A.; Fesmire, A.J.; Johnson, S.S.; Neel, D.R.; Markham, L.E.; Olson, J.C.; Ott, M.; Sangha, H.; Vasquez, D.G.; Whitt, S.P.; Wilkins, H.E. 3rd, Moncure M. A 360° Rotational Positioning Protocol of Organ Donors May Increase Lungs Available for Transplantation. Crit Care Med. 2019 Aug;47(8):1058-1064. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministero della Salute, protocolli e linee di indirizzo trapianti. Available online: https://www.trapianti.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_cntPubblicazioni_545_allegato.pdf.

- Ghimessy, Á.K.; Farkas, A.; Gieszer, B.; Radeczky, P.; Csende, K.; Mészáros, L.; Török, K.; Fazekas, L.; Agócs, L.; Kocsis, Á.; Bartók, T.; Dancs, T.; Tóth, K.K.; Schönauer, N.; Madurka, I.; Elek, J.; Döme, B.; Rényi-Vámos, F.; Lang, G.; Taghavi, S.; Hötzenecker, K.; Klepetko, W.; Bogyó, L. Donation After Cardiac Death, a Possibility to Expand the Donor Pool: Review and the Hungarian Experience. Transplant Proc. 2019 May;51(4):1276-1280. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egan, T.M.; Haithcock, B.E.; Lobo, J.; Mody, G.; Love, R.B.; Requard, J.J. 3rd; Espey, J.; Ali, M.H. Donation after circulatory death donors in lung transplantation. J Thorac Dis. 2021 Nov;13(11):6536-6549. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cantador, B.; Moreno, P.; González, F.J.; Ruiz, E.; Fernández, A.M.; Álvarez, A. Influence of Donor Type-Donation After Brain Death Versus Donation After Circulatory Death-on Lung Transplant Outcomes. Transplant Proc. 2023 Dec;55(10):2292-2294. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampson, B.G.; O'Callaghan, G.P.; Russ, G.R. Is donation after cardiac death reducing the brain-dead donor pool in Australia? Crit Care Resusc. 2013 Mar;15(1):21-7. [PubMed]

- Elgharably, H.; Shafii, A.E.; Mason, D.P. Expanding the donor pool: donation after cardiac death. Thorac Surg Clin. 2015;25(1):35-46. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Len, O.; Garzoni, C.; Lumbreras, C.; Molina, I.; Meije, Y.; Pahissa, A.; Grossi, P. ESCMID Study Group of Infection in Compromised Hosts. Recommendations for screening of donor and recipient prior to solid organ transplantation and to minimize transmission of donor-derived infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014 Sep;20 Suppl 7:10-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niman, E.; Miyoshi, K.; Shiotani, T.; Toji, T.; Igawa, T.; Otani, S.; Okazaki, M.; Sugimoto, S.; Yamane, M.; Toyooka, S. Lung recruitment after cardiac arrest during procurement of atelectatic donor lungs is a protective measure in lung transplantation. J Thorac Dis. 2022 Aug;14(8):2802-2811. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Watanabe, Y.; Galasso, M.; Watanabe, T.; Ali, A.; Qaqish, R.; Nakajima, D.; Taniguchi, Y.; Pipkin, M.; Caldarone, L.; Chen, M.; Kanou, T.; Summers, C.; Ramadan, K.; Zhang, Y.; Chan, H.; Waddell, T.K.; Liu, M.; Keshavjee, S.; Del Sorbo, L.; Cypel, M. Donor prone positioning protects lungs from injury during warm ischemia. Am J Transplant. 2019 Oct;19(10):2746-2755. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazzeri, C.; Bonizzoli, M.; Di Valvasone, S.; Peris, A. Uncontrolled Donation after Circulatory Death Only Lung Program: An Urgent Opportunity J Clin Med 2023 Oct 12;12(20):6492.

- Egan, T.M.; Lambert, C.J.Jr.; Reddick, R.; Ulicny, K.S.Jr.; Keagy, B.A.; Wilcox, B.R. A strategy to increase the donor pool: Use of cadaver lungs for transplantation. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1991;52:1113–1120.

- Egan, T.M.; Requard, J.J. 3rd Uncontrolled donation after circulatory determination of death donors (uDCDDs) as a source of lungs for transplant. Am. J. Transpl. 2015;15:2031–2036.

- Valenza, F.; Citerio, G.; Palleschi, A. ; Vargiolu, A; Safaee Fakhr, B.; Confalonieri, A.; Nosotti, M.; Gatti, S.; Ravasi, S.; Vesconi, S. et al. Successful transplantation of lungs from an uncontrolled donor after circulatory death preserved in situ by alveolar recruitment maneuvers and assessed by ex vivo lung perfusion. Am. J. Transpl. 2016;16:1312–1318.

- Suzuki, Y.; Tiwari, J.L.; Lee, J.; Diamond, J.M.; Blumenthal, N.P.; Carney, K.; Borders, C.; Strain, J.; Alburger, G.W.; Jackson, D.; et al. Should we reconsider lung transplantation through uncontrolled donation after circulatory death? Am. J. Transpl. 2014;14:966–971.

- Gamez, P.; Cordoba, M.; Usetti, P.; Carreno, M.C.; Alfageme, F.; Madrigal, L.; Nunez, J.R.; Ramos, M.; Salas, C.; Varela, A. Lung Transplantation from Out-of-Hospital Non-Heart-Beating Lung Donors. One-Year Experience and Results. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2005, 24, 1098–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suberviola, B.; Mons, R.; Ballesteros, M.A.; Mora, V.; Delgado, M.; Naranjo, S.; Iturbe, D.; Minambres, E. Excellent long-term outcome with lungs obtained from uncontrolled donation after circulatory death. Am. J. Transpl. 2019, 19, 1195–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-de-Antonio, D.; Campo-Cañaveral, J.L.; Crowley, S.; Valdivia, D.; Cordoba, M.; Moradiellos, J.; Naranjo, J.M.; Ussetti, P.; Varela, A. Clinical lung transplantation from uncontrolled non-heart-beating donors revisited. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2012, 31, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healey, A.; Watanabe, Y.; Mills, C.; Stoncious, M.; Lavery, S.; Johnson, K.; Sanderson, R.; Humar, A.; Yeung, J.; Donahoe, L.; et al. Initial lung transplantation experience with uncontrolled donation after cardiac death in North America. Am. J. Transplant. 2020, 20, 1574–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).