Introduction

According to the Central Statistical Agency [

1], the Ethiopian agricultural community keep cattle primarily for milk, draught power, breeding, and beef production. The same source states that livestock producers hold a larger population of local breeds, which account for 96.8% of all cattle in the nation, and the remaining are the crossbreds and exotic ones accounted for about 2.71 and 0.41 percent, respectively. About 12.8 million milking cows consisting of indigenous, exotic and their crosses are used for dairying purpose [

1].

Despite the technical, institutional, and socio-economic factors affecting its productivity, the dairy sector still significantly contributes to the national economy because of climate favorable locations with lower animal disease stress [

2]. Despite their extremely low productivity per animal as compared to the exotic and their crosses, that the indigenous dairy cattle breeds are also substantially contributing to the national dairy development of Ethiopia [

3]. To benefit from the genetic variations of the combination effect of exotic and indigenous cattle breeds through crossbreeding, the country has been importing different exotic cattle breeds of which the main being the Holstein-Friesian cattle breed [

4,

5].

Genetic variation has been studied via blood protein analysis as one of the biochemical approaches to investigate the polymorphism occurring at the protein level [

6,

7]. Due to the significance of biochemical polymorphic character studies in the improvement of farm animals as well as the possibility that certain polymorphic alleles tend to be linked to economically important traits through general heterozygosity or the pleiotropic effect, studies focusing on these polymorphic traits have become vital [

8]. Haemoglobin is a blood protein that has been defined as “an evergreen red protein” known to exhibit polymorphism at its globin portion in various livestock species [

9].

The detection of biochemical polymorphisms in gene products at structural loci provides a precise procedure to localize and prove their reliability as genetic markers for some economic traits and livestock diseases [

10]. Haemoglobin polymorphism is one of the biochemical markers, which is a gene-controlled diversity in the different farm animals due to variation in the amino acid sequence in the polypeptide chains of haemoglobin [

8].

Accordingly, haemoglobin has been proven to have biochemical, biophysical, and physiological properties, and its polymorphic variants have been reported to be associated with morphological, performance, and adaptation traits in cattle [

11,

12]. Despite of studying cattle biochemical variants of proteins (Haemoglobin) is relatively affordable in Ethiopian conditions, only a few research works have been conducted on cattle haemoglobin (Hb) polymorphism [

13,

11]. For example, limited studies have revealed the existence of three haemoglobin genotypes namely Hb

AA, Hb

AB, and Hb

BB in Ogaden cattle of Southeastern Ethiopia and Bunja cattle of Nigeria [

14].

According to [

15] and [

16], the Shashemene-Dilla milkshed is a highly contributing region with a significant number of crossbred dairy cattle with unknown genetic composition. Consequently, keeping a dairy herd with unknown genetic makeup might lead to the deterioration of the future performance of the diary sector due accumulation of inbreeding and other negative effects. This calls for a study on the genetic diversity of the dairy cattle population in the region. Unlike the DNA -based technologies, protein polymorphism studies are easier to implement due to their utility, cost, and amount of genetic information accessed [

10]. Given that genetic research in many African nations like Ethiopia is not advanced, the significance of this alternative approach in studying animal genetic diversity would be highly beneficial [

17]. Therefore, this study aimed at investigating the biochemical polymorphism at haemoglobin locus of different blood levels of Holstein-Zebu crosses reared in Shashemene-Dilla milkshed dairy farms. It has been hypothesized that the haemoglobin allelic and genotypic frequencies of different blood levels of Holstein-Zebu crosses is under Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

Materials and Methods

Description of the Study Area

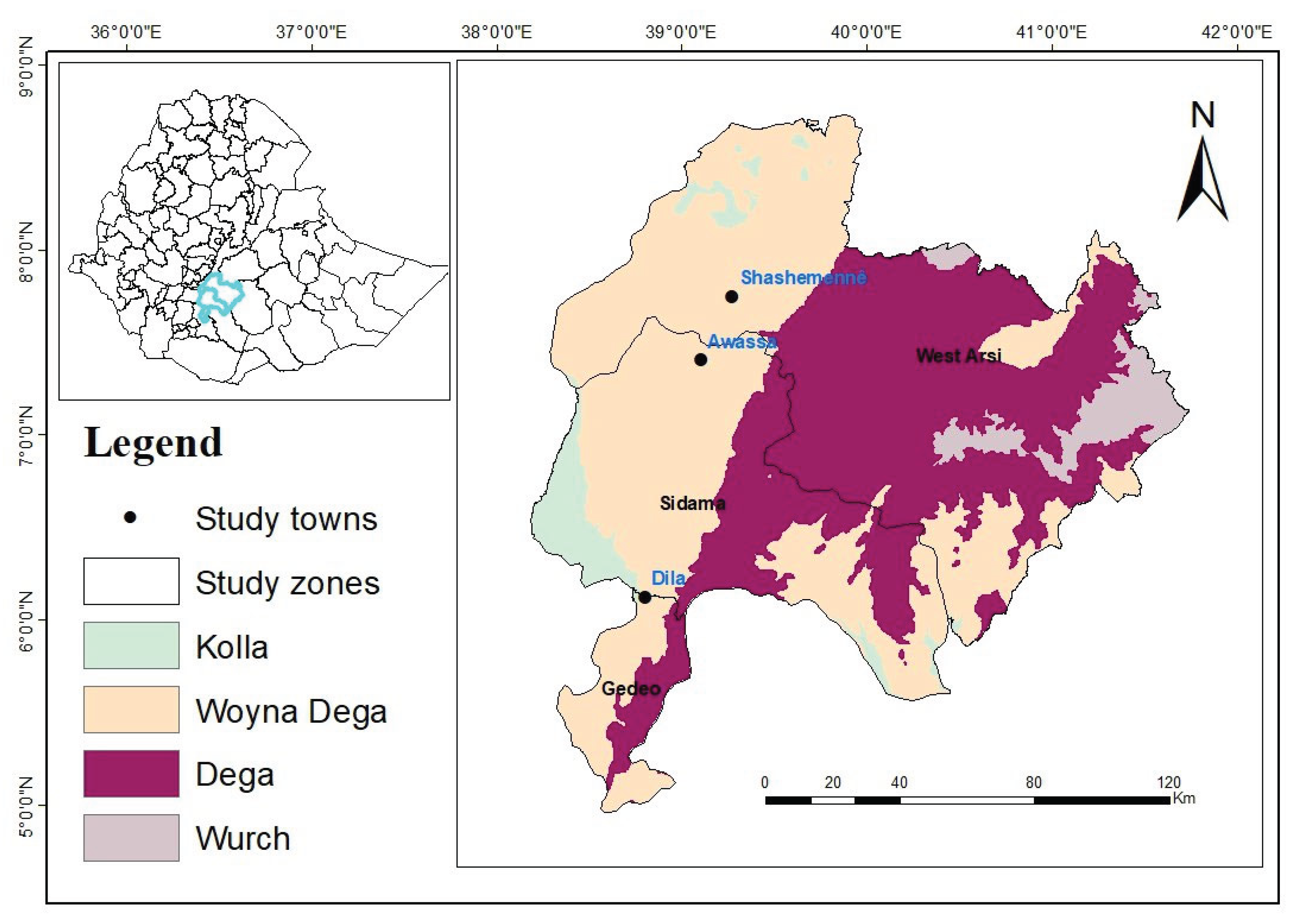

This research was carried out in milkshed dairy farms located in the area extending from Shashemene to Dilla, which is one of the high milk-producing areas in the Rift Valley of Ethiopia. It is located between 250 and 375 kilometers south of Addis Ababa, on the Addis Ababa–Moyale route. Shashemene-Dilla milkshed is chosen for the study based on the existence of dairy farms maintaining crossbred dairy cattle breeds; each of these locations has its distinct agricultural and social customs (

Figure 1).

The major locations considered in the study are Shashemene, Hawassa, and Dilla. Shashemene is in Oromia Regional State, West Arsi Zone, 250 km south of the capital Addis Ababa. (

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/shashemene). The town lies within at an altitude ranging from 1900 to 1950 meters above sea level. It receives an annual rainfall of 879 mm. The average annual temperature is 26℃. The warmest month of the year is March, with an average temperature of 28℃. In Shashemene, July is the coldest month with an average temperature of 23°C and an annual temperature range of 12–27°C. (

https://www.accuweather.com/en/et/shashemene).

Dilla is another area considered in this study. It is located 90 km south of the Sidama regional town Hawassa. It is located at 6

o 22’ to 6

o 42’ N and 38

o 21’ to 38

o 41’ E and at an altitude range of 1300–2500 masl (

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/dilla). It receives an annual rainfall of 850 mm and the annual average minimum and maximum temperatures of 12.5

oC and 28.0

oC, respectively (

https://www.accuweather.com/en/et/dilla).

Blood Sample Collection and Analysis

Blood samples were taken from three distinct blood levels (i.e., 50%, 75%, and 87.5%) of Ethiopian Zebu x Holstein Friesian (HF) crosses that were kept in intensive dairy farms located at Shashemene-Dilla milkshed and whose lineage could be traced back. The total sampled population was 117 from which 39 were drawn from each location namely Shashemene, Hawassa, and Dilla. The sample size of crossbred cows from each blood level in the three locations of the study milkshed was 13.

Blood was collected using a 5ml EDTA-coated tube during the morning period by puncturing the jugular vein. Blood collection was done in the morning to have enough time to centrifuge the whole blood sample and wash the RBCs for further haemolysate preparation. During sample collection, two senior veterinarians and 6 assistants were involved in restraining the animal during sampling. Blood samples were immediately put into an ice-box and transported to the Hawassa University molecular biotechnology laboratory and stored at -20 °C until used for the analysis.

Blood analysis and haemolysate preparation was carried out according to the method described by [

18,

11] with slight modification by keeping the blood samples collected via veno-puncture in a 5ml vacutainer tube coated with anti-coagulant EDTA.

Haemolysate Preparation

The analysis took place at Hawassa University's Biotechnology Laboratory in the School of Animal and Range Sciences. The whole blood sample was centrifuged immediately after collection at 3000rpm/4co for 5 minutes. The upper liquid portion (supernatant plasma and buffy coat) was removed from the centrifuged EDTA blood and cells were washed with saline solution three times. Saline solution (9.0g of NaCl in 1-liter deionized water) was discarded from the last centrifuge. An equal volume of distilled water and 1/2 volume of carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) was added to the RBC sample and then shaken vigorously. The cells with distilled water and carbon tetrachloride were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 1500 G. After the centrifugation, three layers (upper haemolysate, middle RBC leftover and carbon tetrachloride at the bottom) were formed. The upper portion (haemolysate) was used for the determination of agarose gel electrophoretic haemoglobin polymorphism while the remaining was discarded.

Haemoglobin Electrophoretic Analysis

To examine the inherent biochemical variations in haemoglobin (Hb), gel electrophoresis was performed with 1% agarose gel and separated using Tris-EDTA-Borate at pH 8.6. Then, the electrophoresis was carried out for 2 hours at 120 volts [

11].

Identification of Haemoglobin Polymorphisms

Based on how quickly the haemoglobin (Hb) bands moved towards the cathode, different Hb phenotypes were distinguished [

19]. After the electrophoretic run was completed, the hemoglobin bands were visualized using direct observation and a gel documentation system (Alpha imager Mini Gel Documentation System, For Colorimetric, UV Fluorescent) without discoloration. The Hb polymorphism was detected based on differential speed of migration. A single fast-moving band is designated as a "BB homozygote" (HbBB), whereas a single slow-moving band is indicated by the term "AA homozygote" (HbAA). The existence of both slow- and fast-moving bands was denoted as AB heterozygote (HbAB).

Statistical Analysis

The allele and genotype frequencies (observed and expected) were calculated using GeneAlEx6.503. It was performed from the data obtained in the hemoglobin electrophoretic determination analysis. The observed Hb allele and genotype frequencies were subjected to PopGene 1.32 software to execute a chi-square test for goodness of fit for the observed and expected frequencies under Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium [

20].

Heterozygosity (HE), Homozygosity (HO), effective number of alleles (ne), and Summary of F-statistics (Fixation indices) were also computed using the same software to detect the existence of genetic variability in the crossbred dairy cattle populations. Estimates of heterozygosity between different blood levels of the Holstein crosses were measured as the unbiased estimate of mean heterozygosity [

21].

Results

Allele and Genotype Frequencies

The allele and genotype frequencies in three different blood level HF crosses are presented in

Table 1. The three distinct hemoglobin genotypes of AA (slow-moving band), AB (both slow and fast-moving band), and BB (fast-moving band) were observed in agarose gel electrophoresis.

Table 1 and

Table 2 represents the genotype and allele frequencies at the haemoglobin locus, as well as the observed and expected numbers of hemoglobin genotypes along with the Chi-square test for the HF crossbred population divided into three groups according to different blood levels and locations. The HbA was the most predominant allele in the studied population (

Table 1).

Higher gene and genotypic frequency variations were found among the population categorized in the blood level group rather than in three different locations of the studied milkshed (

Table 1 and

Table 2).

The Chi-square test revealed that except for 87.5% exotic blood levels, the sampled subpopulations were not under Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium for haemoglobin locus (

Table 1). The HF crosses at Hawassa (HAW) dairy farms on the other hand were under Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium from the population grouped into locations (

Table 2). Haemoglobin was found to be polymorphic across location and level of exotic gene inheritance of cows. The blood level and location also had a significant association (P <0.05) with the occurrence of Hb types except for 87.5% exotic blood level and HF crosses at HAW location.

The Genetic Diversity Measurements

The percentage of polymorphic loci and measurements of genetic variation at haemoglobin locus between dairy cows of various levels of exotic gene inheritance are shown in

Table 3. Both the observed (HO) and expected heterozygosity (HE) at the haemoglobin locus showed that 50% crosses had higher HO and HE while the HO, the HE as well as the homozygosity estimates were similar for 87.5% HF crosses (

Table 3).

The observed and expected homozygosity estimates on the other hand showed that the HF crosses with 87.5% and 50% exotic genes had the highest and lowest homozygosity estimates, respectively. The 50% HF crosses had a better effective number of alleles per locus. As shown in

Table 4, the highest observed homozygosity was noted in SHA and DIL milk shades with comparable values. However, the lowest expected homozygosity estimate was found in DIL while the highest was in the SHA location. The HF crosses at the Dilla location had a relatively higher effective number of alleles per locus than the SHA and HAW locations.

A measure of Nei’s genetic closeness and distance between different blood levels HF crosses is presented in

Table 5. The closest genetic relationship was observed between 50% and 75% exotic gene inheritance (D=0.01), while the farthest genetic distance was found between 50% and 87.5% crosses (D=0.03).

The highest genetic identity of HF crosses reared in SHA was observed with those of HAW and SHA (

Table 6). Similarly, the highest genetic similarity was observed between HF crosses reared in HAW and DIL milkshed locations. On the other hand, the Nei’s measurement for genetic divergence between HF crossbred populations at three study locations revealed no genetic distance between populations reared in different locations.

The Fixation Indices

The summary of F-statistics (Fixation Indices) results revealed that the inbreeding coefficient value within individuals relative to their subpopulations (FIS) grouped in the three different exotic blood levels and three locations were 0.38 and 0.41, respectively. Genetic differentiation among subpopulations was significant (FST = 0.01) for the subpopulations grouped in three different locations. The subpopulations grouped in the three different exotic gene inheritance levels had non-significant (FST=0.06) genetic differentiation value. The inbreeding coefficient value of individual crossbred dairy cow relative to the total population (FIT) was 0.42.

Discussion

The electrophoresis result of the current study showed the existence of three types of haemoglobin phenotypes namely, a slow-moving (AA), a fast-moving (BB), and a combination of both slow + fast-moving bands (AB). The complex molecules that make up hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying component of blood, are composed of a protein part, the globin, and an effective haeme part. While the haeme part of the haemoglobin molecule is relatively constant, the globin part, a combination of two sets of polypeptide chains that makes up to 96% of the haemoglobin molecule, varies considerably from species to species and within a species [

22].

Since the haemoglobin polymorphism is mostly due to the β-chain variant, the - βB shows a Mendelian mode of inheritance presenting 3 phenotypes Hb

A, Hb

B, and Hb

AB, though the rare α-chain variants are also reported in Podolian cattle [

11]. The first to describe two electrophoretically different components of haemoglobin in cattle were [

23], which were reported in Algerian cattle [

11]. The Hb

C, a third component, and Hb

D, a fourth component were discovered following the start of the starch gel electrophoresis. The Hb

C variant has been regarded as a typical "African" haemoglobin, because of its relatively high frequency in the breeds and types of African cattle [

24].

The Italian Podolic cattle, which is native to Southern Europe, were reported to have two new alpha and one-beta globin variants around the end of the 20th century [

25]. Researchers of haemoglobin polymorphism in Grey Alpine cattle formulated the hypothesis of the hemoglobin system as a signature of a past common origin between Grey Alpine and Italian Podolic cattle after they found out the existence of the Y alpha-globin variant (HbAY) and the Zebu beta-globin variant in Grey Alpine cattle [

26].

In the present study, the frequency of haemoglobin variant A was highest in cows with higher level of exotic inheritance (87.5%) while the highest frequency Hb

B was observed in the HF crosses of 50%. This finding agrees with those reported for crosses of HF cattle with different local cattle breeds [27-30]. In earlier studies, [

31] reported a significantly higher frequency of Hb

B in

Bos indicus type cattle compared to

Bos taurus type breeds. The Hb

B exhibited a notably elevated frequency in Zebu cattle, demonstrating a decline in frequency of 3/8 to 7/8 in European-Zebu hybrids [

32].The gene and genotypic frequency of the current study is consistent with earlier study results, which revealed a high prevalence of Hb

A in

Bos taurus cattle [33-34].

The current study's findings regarding the predominance of Hb

AA type is consistent with those reported for Friesian x Bunaji cattle crosses [

28] and Ogaden cattle [

11]. As the altitude of the terrain increases in the current milkshed locations, the frequency of Hb

A tends to increase which is consistent with the reports of [

35]. Research by [

36] reported that the Hb

A variant is more prevalent in areas with stressful production environments such as frequent drought and extreme temperatures. In another study, [

22] reported the predominance of Hb

A variant in cows and buffaloes with allelic frequencies of 0.51.

The haemoglobin locus genotypic frequencies, in the tested population of HF crosses in the studied milkshed were not under Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. The methods of mating, evolutionary influences over time, sample size, migration and artificial selection could be some of the reasons behind this observation [

37,

38].

The present study revealed an average heterozygosity of 0.1, which indicates the presence of a relatively low genetic variation at the hemoglobin locus in the studied crossbred dairy cattle. Nonetheless, there was variation in the heterozygosity values among the three genotypes and locations. Although, genetic differences and similarities within and between breeds are important raw materials for the genetic improvement of farm animals, estimates of mean heterozygosity (HE) obtained in this study were lower than the recommended range, which should be between 0.3 and 0.8 in the population to be used in measuring genetic variation [

39]. Low mean heterozygosity than expected could suggest a higher inbreeding rate, which might be caused by population size, scarcity of breeding males, and restricted geographic dispersion [

40].

Alleles of the Hb locus were polymorphic in the studied HF crossbred dairy cattle population and locations. From the F-statistics results, values of the inbreeding coefficient (FIS) within populations grouped in the three different exotic blood levels and three locations were 0.38 and 0.41, respectively. Genetic differentiation among populations was significant (FST = 0.01) and non-significant (FST=0.06) for the effect of location and exotic blood levels, respectively. The inbreeding coefficient value of individuals relative to the total population (FIT) was 0.42.

Conclusion

The preponderance of HbAA over the other Hb genetic types in different blood levels of crossbred cows may suggest that cattle carrying this type of genetic variant are being favored by tropical environments. The observed genetic diversity among different inheritance of exotic genes (HF 50%, HF 75%, and HF 87.5%) reared in the three different milkshed locations might be associated with their genetic adaptation to the production environment in which they have been managed. The current study further revealed that the tested population was not under Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Moreover, the study revealed the existence of a relatively higher level of similarity within the sampled population. The present study will provide baseline information to design cost-effective and sustainable genetic improvement programs for crossbred dairy herds in the study milkshed. The current genetic diversity study can also be a way out of keeping a dairy herd with an unknown genetic makeup, which might lead to the deterioration of the future performance of the crossbred cows due to negative genetic effects.

Author Contributions

The corresponding author contributed to the implementation of the experiment, processed the experimental data, performed the analysis and drafted the manuscript. Each author has contributed to the conceptual idea and design of this work, participated in the editing and review of the article, made decision regarding the submission for publication, and was involved in all stages of the process.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Permission was obtained from Hawassa University Research Ethics Review Committee to carry out the present work (HURERC-REC016/23). Two senior veterinary doctors with great experience in standard protocol for animal care and welfare were engaged during sample collection.

Data Availability Statement

Upon reasonable request, the datasets of this study can be available from the corresponding author.

Authors Contributions

Conceptualization: Eyerusalem Tesfaye, Aberra Melesse, Simret Betsha; Data curation: Eyerusalem Tesfaye; Formal analysis: Eyerusalem Tesfaye; Methodology: Eyerusalem Tesfaye; Software: Eyerusalem Tesfaye; Validation: Aberra Melesse, Simret Betsha, Dereje Andualem; Investigation: Eyerusalem Tesfaye; Writing – original draft: Eyerusalem Tesfaye; Writing- review and editing: Eyerusalem Tesfaye, Aberra Melesse, Simret Betsha, Dereje Andualem

Declaration of Generative AI

No AI tools were used in this article.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dilla University and Ethiopian ministry of education for providing the opportunity to implement this research work. We would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to Hawassa University School of Animal and Range Sciences for paving the way for ease implementation of laboratory experiment. Finally yet importantly, authors would like to thank those commercial dairy producers in each location for providing their animal free for blood sample collection and the veterinarians in the studied milkshed for their cooperation during blood sample collection

References

- CSA. Federal democratic republic of Ethiopia central statistical agency volume II report on livestock and livestock characteristics (private peasant holdings) 589. Statistical bulletin 2021/2022;589.

- Mihret T, Mitku F, Guadu T. Dairy Farming and its Economic Importance in Ethiopia: A Review. World J Dairy Food Sci 2017;12(1):42–51. [CrossRef]

- Gebrehiwet BH. Dairy cattle crossbreeding in Ethiopia: Challenges and Opportunities: A Review. Asian J Dairy Food Res 2020;39(3):180-186. [CrossRef]

- Mengistie AA. Challenges, Opportunities and Prospects of Dairy Farming in Ethiopia: A Review. Article in Intl J Food Sci Nutr;2016. [CrossRef]

- Feleke A, Ayza A, Bena BE. Characterization of Dairy Cattle Production Systems in and around Wolaita Sodo Town, Southern Ethiopia Onfarm performance of Dorper sheep crosses View project Productive Performance of dorpersheep crosses View project. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308624549; 2016.

- Ukwu HO, Gwaza DS, Apav PM. Preliminary assessment of genetic diversity at the haemoglobin locus in the Bunaji cattle. J Res Rep Genet 2017;1(1): 32-35.

- Rashamol VP, Sejian V, Bagath M, Krishnan G, Archana PR, Bhatta R. Physiological adaptability of livestock to heat stress: an updated review. J Anim Behav Biometeorol 2020: 6(3):62-71. [CrossRef]

- Egena SSA, Alao RO. Haemoglobin polymorphism in selected farm animals: A review. Biotechnol Anim Husb 2014;30(3):377–390. [CrossRef]

- Alphonsus C, Akpa GN, Usman N, Barje PP Byanet O. Haemoglobin Polymorphism and its Distribution in Smallholder Goat Herds of Abuja Nigeria. Glob J Mol Sci 2012; 7(1): 11-14. [CrossRef]

- Akinyemi MO, Salako AE. Genetic relationship among Nigerian indigenous sheep populations using blood protein polymorphism. J Agric Sci Technol 2012;4(2):107-112.

- Pal SK, Mummed Y. Investigation of haemoglobin polymorphism in Ogaden cattle. Vet World 2014;7(4):229–233. [CrossRef]

- Shettima MM, Alade NK, Raji AO. Haemoglobin types and their effects on morphometric traits of indigenous cattle, sheep and goats in Nigeria. Niger J Anim Prod 2019;46(2), 22- 26. [CrossRef]

- Gezahegn S. Characterization of some indigenous cattle breeds of Ethiopia using blood protein polymorphisms. MSc thesis, Alemaya University of Agriculture (Haramaya University), Ethiopia; 1996.

- Essien IC, Askpa GN, Barje PP, Alphonsus C. Haemoglobin types in Bunaji cattle and their Friesian crosses in Shika, Zaria-Nigeria. Afr J Anim Biomed Sci 2011;6(1):ien122-126.

- Yigrem S, Beyene F, Tegegne A, Gebremedhin B. Dairy production, processing and marketing systems of Shashemene-Dilla area, South Ethiopia. IPMS Working Paper; 2008.

- Tegegne A, Gebremedhin B, Hoekstra D, Belay B, Mekasha Y. Smallholder dairy production and marketing systems in Ethiopia: IPMS experiences and opportunities for market-oriented development; 2013.

- Gifford-Gonzalez D, Hanotte O. Domesticating Animals in Africa: Implications of Genetic and Archaeological Findings. J World Prehist 2011;24 (1): 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Huntsman RG, Lehmann H. Man's Haemoglobins: Including the Haemoglobinopathies and their Investigation. Published by J Biotechnol 1974; Lippincott, Philadelphia, PA.ISBN 10: 0397581483ISBN 13: 9780397581481.

- Agaviezo BO, Ajayi FO, Benneth HN. Hemoglobin polymorphism in Nigerian indigenous goats in the Niger delta region, Nigeria. Int J Sci Nat 2013;4:3.

- Gwaza DS, Ukwu HO, Ogbole PA. Assessment of haemoglobin polymorphism as a potential protein marker in selection for genetic improvement of the West African Dwarf Goat population in Nigeria. Int J Biotechnol 2019;8(1):pp.38 https://ideas.respec.org/a/pkp/tijobi/v8y2019i1p38-47id1555.html.

- Nei M. Genetic distance between populations. Am Nat 1972;106: 283-292. https://wwwjstor.org/stable/2459777.

- Ahmed MH, Ghatge MS, Safo MK. Hemoglobin: Structure, Function and Allostery. Vertebrate and invertebrate respiratory proteins, lipoproteins and other body fluid protein. Subcell Biochem 2020;94:345-382. [CrossRef]

- Cabannes R, Serain C. Heterogeneite de lhemoglobine des bovides-identification electrophoretique de deux hemoglobines bovines. Comptes rendus des seances de la societe de biologie et de ses filiales 1955;149(1-2):7-10.

- Osterhoff DR. Haemoglobin types in African cattle. J S Afr Vet Assoc 1975;46(2):185-189.

- Pieragostini E, Alloggio I, Petazzi F. Insights into hemoglobin polymorphism and related functional effects on hematological pattern in Mediterranean cattle, Goat and Sheep. Diversity 2010 2(4):679–700. [CrossRef]

- Ciani ELENA, Alloggio I, Pieragostini E. Intriguing hemoglobin polymorphism in Grey Alpine cattle and functional effect. Large Anim Rev 2014;20(1):41-44.

- Avila R AG, Acosta RR, Velazquez EA, Atilano LD, Perez RH. Genetic polymorphism in the albumin, haemoglobin and transferrin systems in Holstein x zebu-crossbred cattle in the humid tropics. Vet Mex 1994;25(3): 255-259.

- Pano Barje P, Alphonsus C, Essien I, Askpa G, Barje P, Alphonsus C. Haemoglobin types in Bunaji cattle and their Friesian crosses in Shika, Zaria-Nigeria 1. Intl Biomed Sci 2011; 6(1). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277565759.

- Gaikwad US, Ulmek BR, Fulpagare YG. Haemoglobin polymorphism in Gir crossbred cattle. Res J Anim Husb Dairy Sci 2012;3(2):50-52. https://researchjournal.co.in/online/RJAHDS/RJAHDS%203(2)/3_A-50-52.

- Umar DSB, Nwagu BI, Umar UA, Rufina OO, Saleh I. Studies on the Productive Traits and Relationship between Breeds of Cattle (Friesian Bunaji Cross, Bunaji and Sokoto Gudali) Using Blood Biochemical Polymorphism. Asian J Biochem Genet Mol Bio 2020;3(1):13–21. [CrossRef]

- Bachmann AW, Campbell RS, Yellowlees D. Haemoglobins in cattle and buffalo. Haemoglobin types of Bos taurus, Bos indicus, Bos banteng and Bubalis in northern Australia. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci 1978;56(5):523-9. [CrossRef]

- Panepucci L. A study of biochemical polymorphisms in european/zebu dairy crossbred cattle and of their relationship with European and zebu cattle. Braz J Genet 1989;(12).

- Braend M. Studies on the relationship between cattle breeds in Africa, Asia and Europe: Evidence obtained by studies of blood groups and protein polymorphism. World Rev Anim Prod 1972; 8: 9-14. [CrossRef]

- Tejedor T, Rodellar C, Zaragosa P. Analysis of genetic variation in cattle breeds using electrophoresis indigenous studies. Archivos de Zootecnia (Spain) 1986;35: 225–237.

- Ibrahim AO. Haemoglobin polymorphism and body mensuration characteristics of Red Sokoto goats (Doctoral dissertation, M. Sc. Thesis Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria); 2010.

- Hrinca G. Haemoglobin types in the Carpathian breed and their relevance for goat adaptation. Lucrări Ştiinţifice 2010;54, Seria Zosotehnie. cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/pdf/10.5555/20113241886.

- Mitchell-Olds T, Willis JH, Goldstein DB. Which evolutionary processes influence natural genetic variation for phenotypic traits? Nat Rev Genet 2007;8(11):845-856.

- Sun L, Gan J, Jiang L, Wu R. Recursive test of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in tetraploids. Trends in genet 2021;37(6):504-513. [CrossRef]

- Takezaki N, Nei M. Genetic distances and reconstruction of phylogenetic Tree from microsatellite DNA. Genet 1996;144: 389-399. [CrossRef]

- Unal EO, Isik R, Sen A, Kus EG, Soysal Mİ. Evaluation of genetic diversity and structure of Turkish water buffalo population by using 20 microsatellite markers. Anim 2021;11(4). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).