1. Introduction

Deep learning has achieved significant success in a wide range of fields [

1,

2]. Credits for these accomplishments largely go to the so-called scaling law, wherein fundamental computational units such as convolutions and attention mechanisms are designed and scaled per an optimized architecture. Prominent examples include ResNet [

3], Transformer [

4], and Mamba [

5]. Recently, motivated by neuroscience’s paramount contributions to AI, an emerging field called

NeuroAI has garnered significant attention, which draws upon the principles of biological circuits in the human brain to catalyze the next revolution in AI [

6]. The ambitious goal of NeuroAI is rooted in the belief that the human brain, as one of the most intelligent systems, inherently possesses the capacity to address complex challenges in AI development [

7]. Hence, it can always serve as a valuable source of inspiration for guiding practitioners, despite the correspondence between biological and artificial neural networks sometimes being implicit.

Following NeuroAI, let us analyze the scaling law through the lens of brain computation. It is seen that the human brain generates complex intellectual behaviors through the cooperative activity of billions of mutually connected neurons with varied morphologies and functionalities [

8]. This suggests that the brain simultaneously benefits from scale at the macroscopic level and neuronal diversity at the microscopic level. The latter is a natural consequence of stem cells’ directed programming in order to facilitate the task-specific information processing. Inspired by this observation, extensive research has shown that incorporating neuronal diversity into artificial neural networks can markedly enhance their capabilities [

7]. For instance, researchers have transitioned beyond traditional inner-product neurons by integrating diverse nonlinear aggregation functions, such as quadratic neurons [

9], polynomial neurons [

10], and dendritic neurons [

11]. Such networks have achieved superior performance in tasks like image recognition and generation, underscoring the promise and practicality of innovating a neural network at the neuronal level.

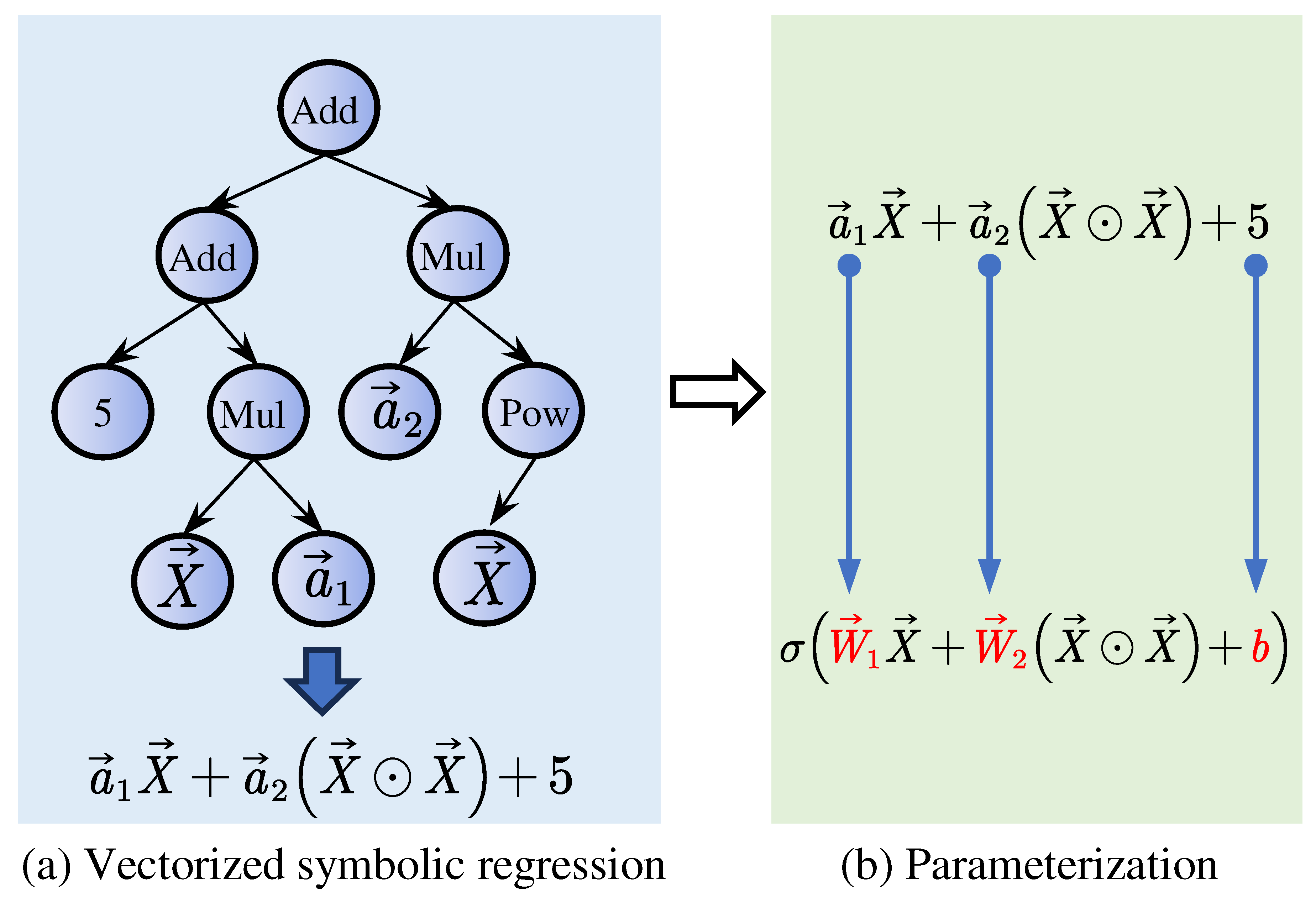

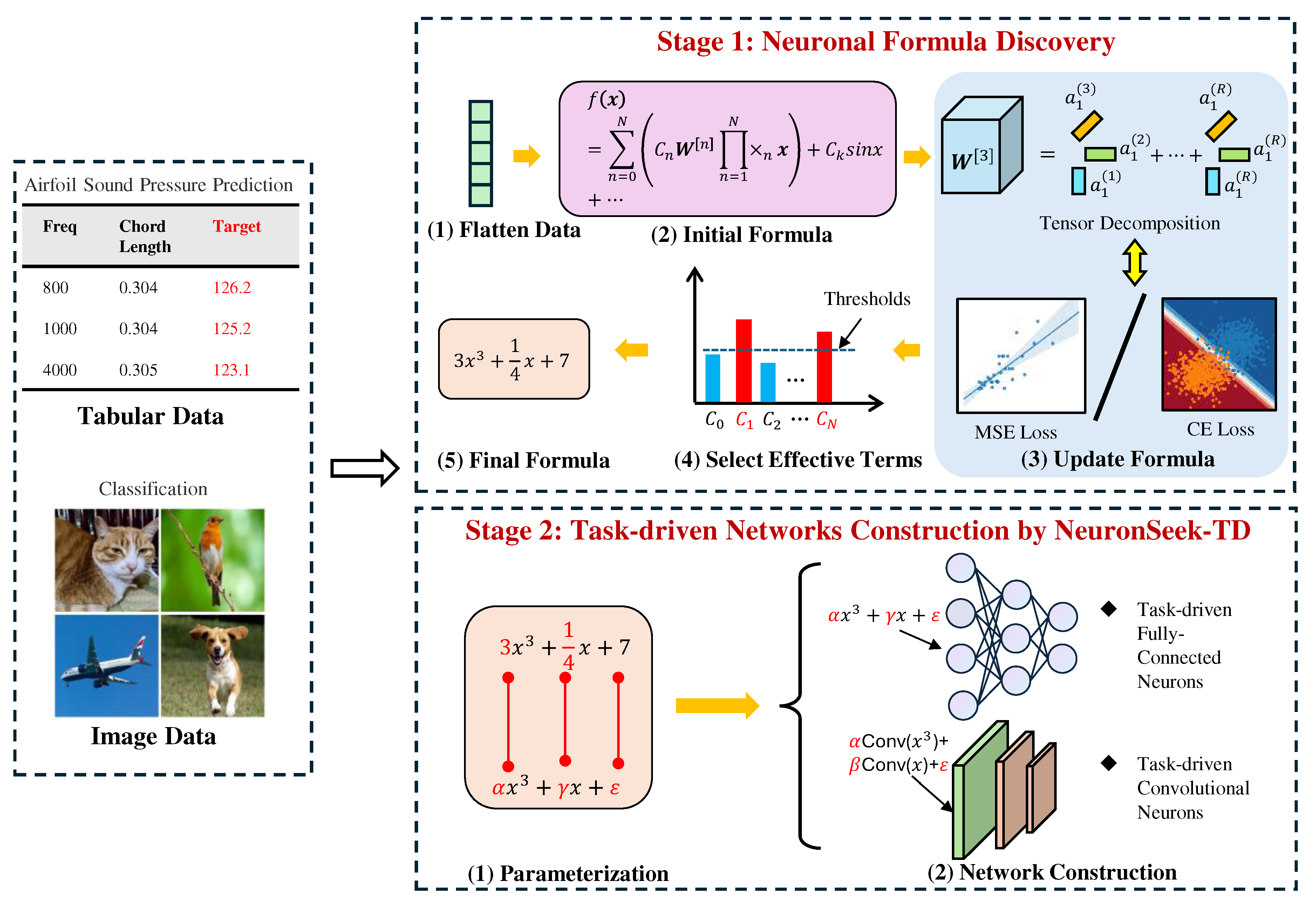

Along this direction, driven by the task-specific nature of neurons in our brain, recent research [

12] introduced a systematic framework for task-driven neurons. Hereafter, we refer to prototyping task-driven neurons as

NeuronSeek. This approach assumes that there is no single type of neurons that can perform universally well. Therefore, it enables neurons to be tailored for specific tasks through a two-stage process. As shown in

Figure 1, in the first stage, the vectorized symbolic regression (SR)—an extension of symbolic regression [

13,

14] that enforces uniform operations for all variables—identifies the optimal homogeneous neuronal formula from data. Unlike traditional linear regression and symbolic regression, the vectorized SR searches for coefficients and homogeneous formulas at the same time, which can facilitate parallel computing. In the second stage, the derived formula serves as the neuron’s aggregation function, with learnable coefficients. Notably, activation functions remain unmodified in task-driven neurons. At the neuronal level, task-driven neurons are supposed to have superior performance than those one-size-fits-all units do, as it imbues the prior information pertinent to the task. More favorably, task-driven neurons can still be connected into a network to fully leverage the power of

connectionism. Hereafter, we refer to task-driven neurons using symbolic regression as NeuronSeek-SR. NeuronSeek considers in tandem neuronal importance and scale. From design to implementation, it systematically integrates three cornerstone AI paradigms:

behaviorism (the genetic algorithm runs symbolic regression),

symbolism (symbolic regression distills a formula from data), and

connectionism.

Despite this initial success, the following two major challenges remain unresolved in prototyping task-driven neurons.

Non-deterministic and unstable convergence. While symbolic regression employs modified genetic programming (GP) to discover polynomial expressions [

15,

16], its tree-based evolutionary approach struggles to converge in high-dimensional space. The resulting formulas demonstrate acute sensitivity to certain hyperparameters, such as initialization conditions, population size, and mutation rate. This may confuse users about whether the identified formula is truly suitable for the task or due to the random perturbation, therefore hurting the legibility of task-driven neurons.

Necessity of task-driven neurons. In the realm of deep learning theory, it was shown [

17,

18,

19] that certain activation functions can empower a neural network using a fixed number of neurons to approximate any continuous function with an arbitrarily small error. These functions are termed “super-expressive" activation functions. Such a unique and desirable property allows a network to achieve a precise approximation without increasing structural complexity. Given the tremendous theoretical advantages of adjusting activation functions, it is necessary to address the following issue:

Can the super-expressive property be achieved via revising the aggregation function while retaining common activation functions?

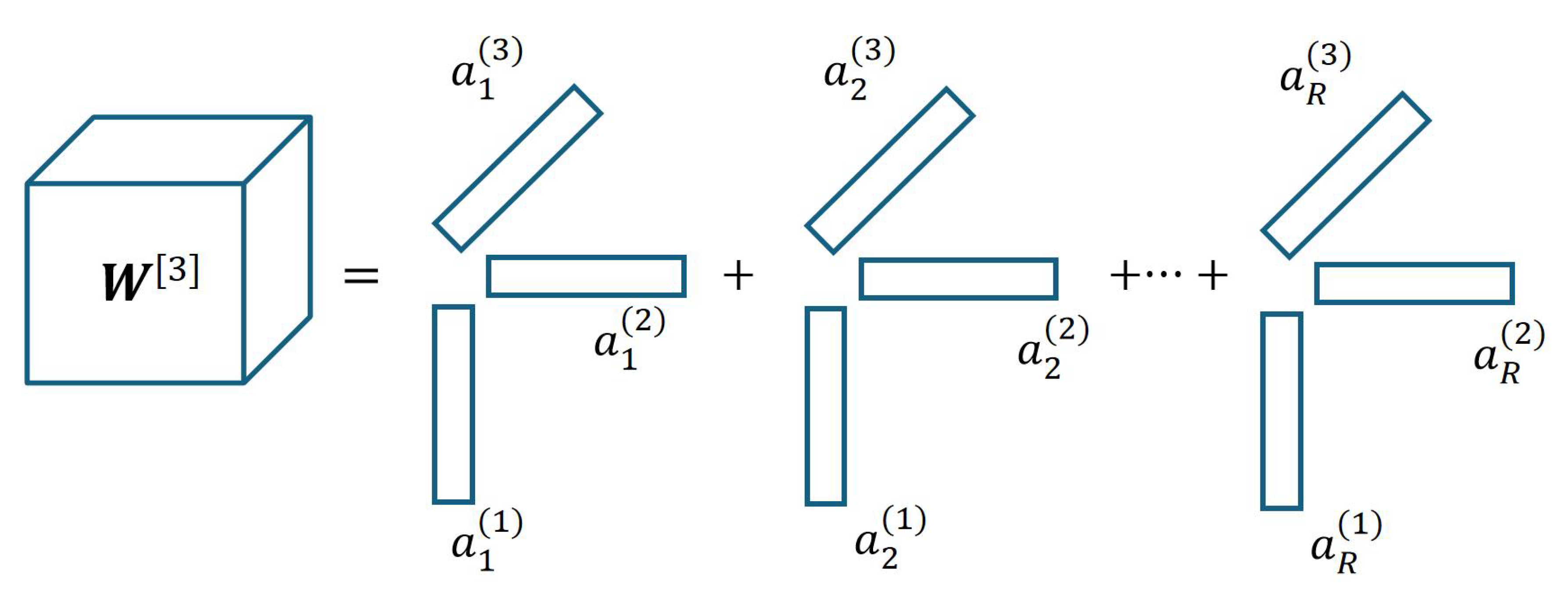

In this study, we address the above two issues satisfactorily. On one hand, in response to the instability of NeuronSeek-SR, we propose a tensor decomposition (TD) method referred to as NeuronSeek-TD. This approach begins by assuming that the optimal representation of data is encapsulated by a high-order polynomial coupled with trigonometric functions. We construct the basic formulation and apply TD to optimize its low-rank structure and coefficients. Therefore, we reformulate the unstable formula search problem (NeuronSeek-SR) into a stable low-rank coefficient optimization task. To enhance robustness, we introduce the sparsity regularization in the decomposition process, automatically eliminating insignificant terms while ensuring the framework to identify the optimal formula. Additionally, rank regularization is employed to derive the simplest possible representation. The improved stability of our method stems from two key factors: i) Unlike conventional symbolic regression which suffers from complex hyperparameter tuning in genetic programming [

20], NeuronSeek-TD renders significantly fewer tunable parameters. ii) It has been proven that tensor decomposition with rank regularization tends to yield a unique solution [

21], thereby effectively addressing the inconsistency issues inherent in symbolic regression methods.

On the other hand, we close the theoretical deficit by showing that task-driven neurons that use common activation such as ReLU can also achieve the super-expressive property. Earlier theories like [

17,

18,

19] first turn the approximation problem into the point-fitting problem, and then uses the dense trajectory to realize the super-expressive property. The key message is the existence of a one-dimensional dense trajectory to cover the space of interest. In this study, we highlight that dense trajectory can also be achieved by adjusting aggregation functions. Specifically, we integrate task-driven neurons into a discrete dynamical system defined by the layer-wise transformation

, where

T is the mapping performed by one layer of the task-driven network. There exists some initial point

that can be taken by

T to the neighborhood of any target point

. To approximate

, our construction does not need to increase the values of parameters in

T and the network, and we just compose the transformation module

T different times. This means that we realize “super-super-expressiveness": not only the number of parameters but also the magnitudes remain fixed. In summary, our contributions are threefold:

We introduce tensor decomposition to prototype stable task-driven neurons by enhancing the stability of the process of finding a suitable formula for the given task. Our study is a major modification to NeuronSeek.

We theoretically show that task-driven neurons with common activation functions also enjoy the “super-super-expressive” property, which puts the task-driven neuron on a solid theoretical foundation. The novelty of our construction lies in that it fixes both the number and values of parameters, while the previous construction only fixes the number of parameters.

Systematic experiments on public datasets and real-world applications demonstrate that NeuronSeek-TD achieves not only superior performance but also stability compared to NeuronSeek-SR. Moreover, its performance is also competitive compared to other state-of-the-art baselines.

4. Super-Expressive Property Theory of Task-Driven Neuron

In this section, we formally prove that task-driven neurons that modify the aggregation function can also achieve the super-expressive property. Our theory is established based on the chaotic theory. Mathematically, we have the following theorem:

Theorem 1.

Let be a continuous function. Then, for any , there exists a function h generated by a task-driven network with a fixed number of parameters, such that

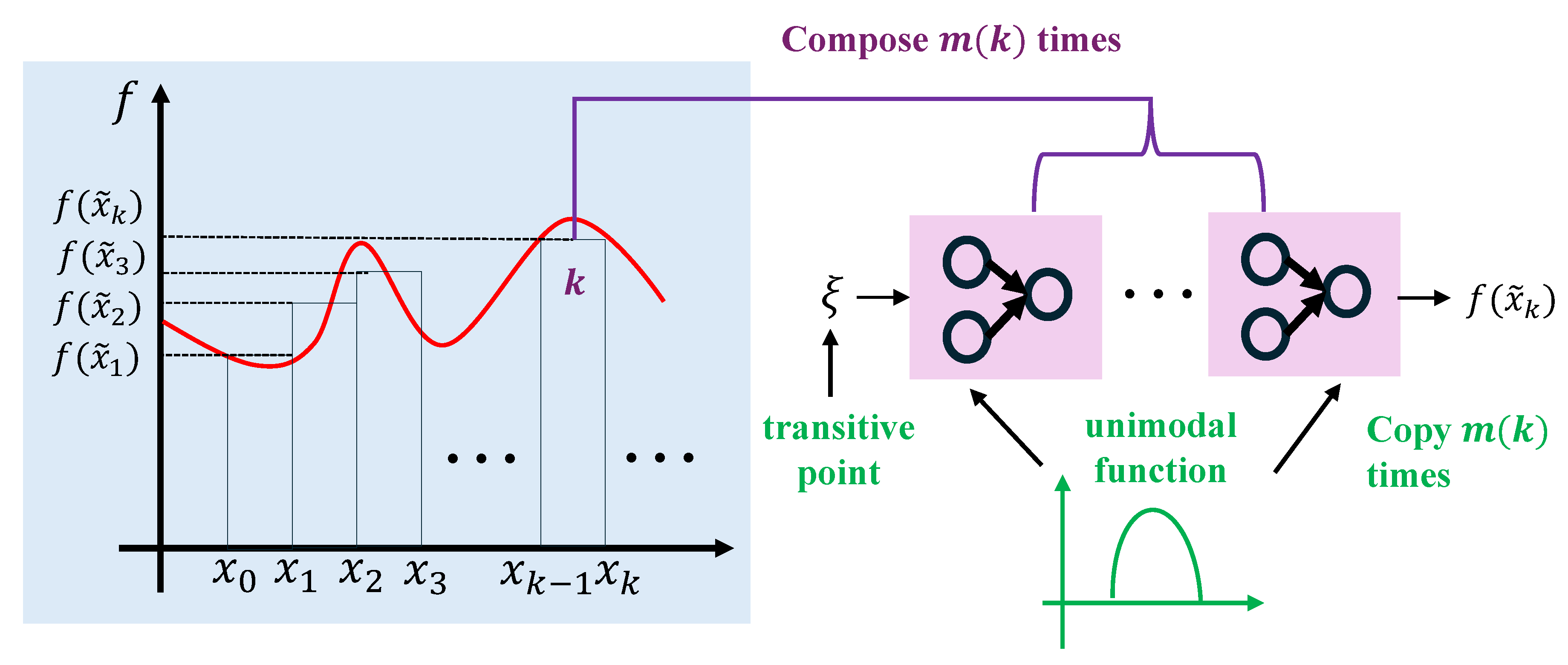

Proof sketch: Our proof leverages heavily the framework of [

18] that turns via the interval partition the function approximation into the point-fitting problem. Hence, for consistency and readability, we inherit their notations and framework. The proof idea is divided into three steps:

Step 1. As

Figure 4 shows, in equal distance, divide

into small intervals

for

, where

K is the number of intervals. The left endpoint of

is

. A higher

K leads to a smaller approximation error. We construct a piecewise constant function

h to approximate

f. The error can be arbitrarily small as long as the divided interval goes tiny. Based on the interval division, we have

where

is a point from

.

Step 2. As

Figure 4 shows, use the function

mapping all

x in the interval

to

k, where

is the flooring function. There exists a one-to-one correspondence between

k and

. Thus, via dividing intervals and applying the floor function, the problem of approximation is simplified into a point-fitting problem. Therefore, we just need to construct a point-fitting function to map

k to

.

Step 3. In [

18], the point-fitting function is constructed as

based on Proposition 1. In contrast, we solve it with a discrete dynamic system that is constructed by a network made of task-driven neurons. We design a sub-network to generate a function

mapping

k approximately to

for each

k. Then

for any

and

, which implies

on

.

is

based on Lemma 1, where

T is a unimodal function from

that can also induce the dense trajectory.

Proposition 1 ([

56]).

For any given set and , there exists a value , such that

where .

Definition 1 ([

57]).

A map is said to be unimodal if there exists a turning point such that the map f can be expressed as

where and are continuous, differentiable except possibly at finite points, monotonically increasing and decreasing, respectively, and onto the unit-interval in the sense that and .

Lemma 1 (Dense Trajectory).

There exists a measure-preserving transformation T, generated from a network with task-driven neurons, such that there exists ξ with dense in . In other words, for any x and , there exist ξ and the corresponding composition times m, such that Particularly, we refer to ξ as a transitive point.

Proof. Since we extensively apply polynomials to prototyping task-driven neurons, we prove that a polynomial of any order can fulfill the condition. The proof can be easily extended to other functions with minor twists.

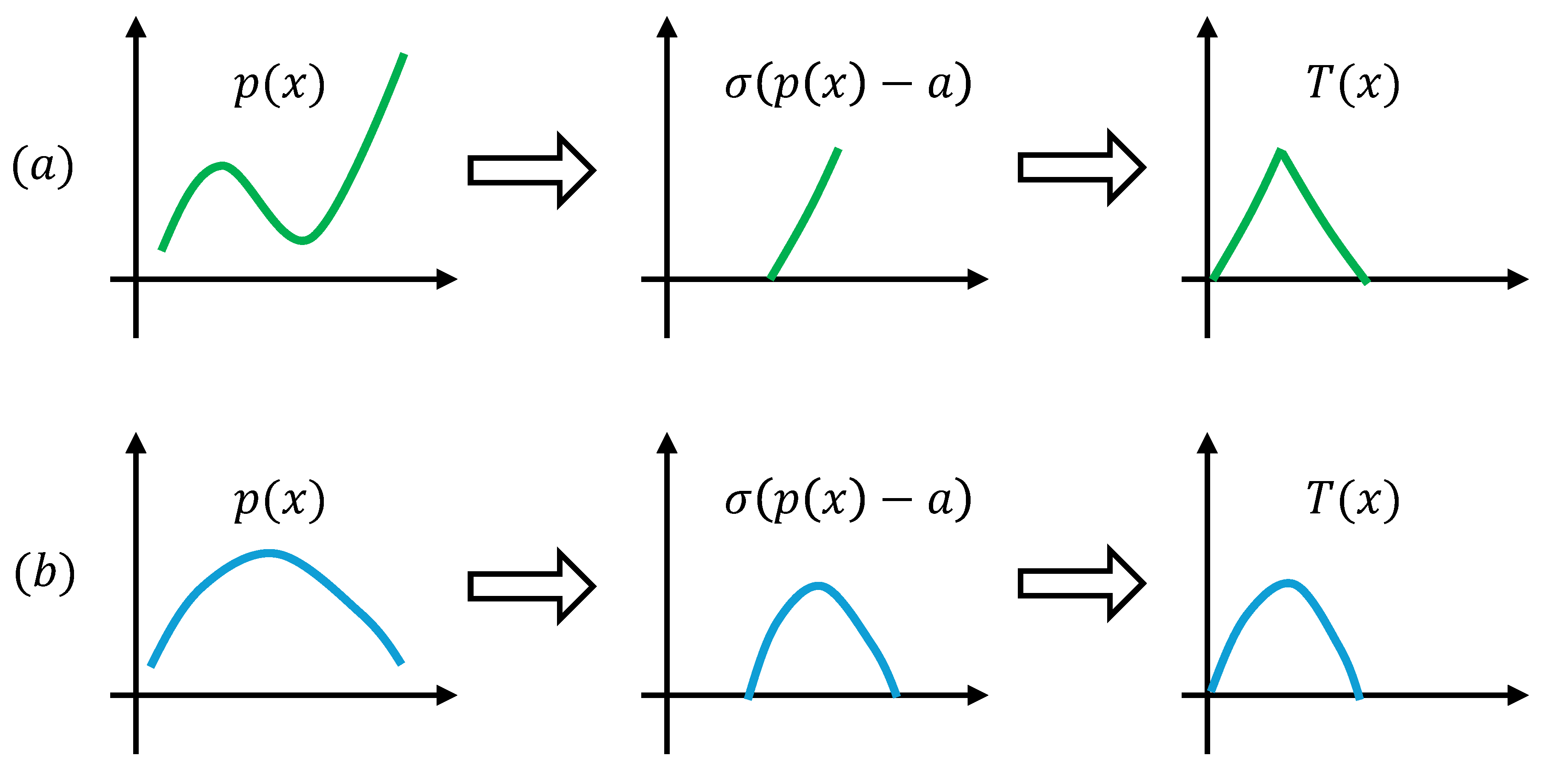

i) Given a polynomial of any order, as shown in

Figure 5, through cutting, translation, flipping, and scaling, we can construct a unimodal map

.

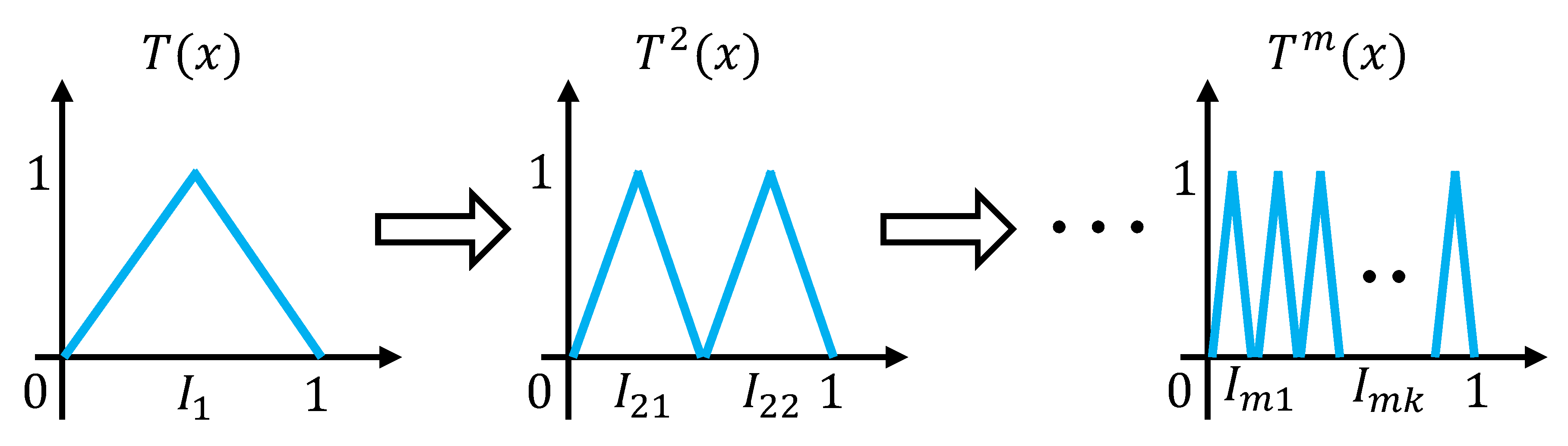

ii) For a unimodal map

T, we can show that for any two non-empty sets

with

, there exists an

m such that

. As

Figure 6 shows, this is because a set

U with

will always contain a tiny subset

such that

. Then, naturally

due to

.

iii) The above property can lead to a dense orbit, combining that

is with a countable basis, according to Proposition 2 of [

58]. For the sake of self-sufficiency, we include their proof here.

Let be a countable base for X. For , the set is open by continuity of f. This set is also dense in X. To see this let U be any non-empty open set. Because of topological transitivity there exists a with . This gives and . Thus is dense. By the Baire category theorem, the set is dense in X. Now, the orbit of any point is dense in X.

Because, given any non-empty open , there is an with and with . This means . Thus the orbit of enters any U.

□

Proof of Theorem 1. Now, we are ready to prove Theorem 1. First, the input x is mapped into an integer k, whereas k corresponds to the composition time . Next, a network module representing T is copied times and composed times such that . Since can approximate well, also approximates well.

Theorem 1 can be easily generalized into multivariate functions by using the Kolmogorov-Arnold theorem.

Proposition 2.

For any , there exist continuous functions for and such that any continuous function can be represented as

where is a continuous function for each .

Remark 2. Our construction saves the parametric complexity. In [

18], though the number of parameters remains unchanged, the values of parameters

increase as long as

n increases. Therefore, the entire parametric complexity goes up. In contrast, in our construction, the parameter value of

T is also fixed for different

. Yet,

T is copied and composed

times. The overall parametric complexity remains unchanged. What increases herein is computational complexity. Therefore, we call for brevity our construction “super-super-expressive”.

5. Comparative Experiments on NeuronSeek

This section presents a comprehensive experimental evaluation of our proposed method and the previous NeuronSeek-SR [

12]. First, we systematically demonstrate the superior performance and enhanced stability of NeuronSeek-TD compared to the previous NeuronSeek-SR. The results demonstrate that pursuing stability in NeuronSeek-TD does not hurt the representation power of the resultant task-driven neurons and even present better results.

5.1. Experiment on Synthetic Data

Here, we adopt the synthetic data to compare the performance of NeuronSeek-TD and NeuronSeek-SR. The synthetic data are generated by adding noise perturbations to the known ground-truth functions. We then measure the regression error (MSE) of the formulas of NeuronSeek-SR and NeuronSeek-TD on the synthetic data.

5.1.1. Experimental Settings

Eight multivariate polynomials are constructed as shown in

Table 2. For simplicity and conciseness, we prescribe:

where

denotes a constant vector,

represents the input vector, and ⊙ denotes the Hadamard product. The elements of

are uniformly sampled from the interval

. We set

to simulate multi-dimensional inputs.

To evaluate the noise robustness of the proposed methods, we introduce three noise levels through

where

y denotes the noise-free polynomial output,

is the noisy observation,

is a standard normal random vector,

controls the relative noise level, and

represents the root mean square (RMS) of the data:

Here, specifies the number of data points. For NeuronSeek-SR, we configure a population size of 1,000 with the maximum of 50 generations. NeuronSeek-TD is optimized using Adam for 50 epochs. The noise levels are set to respectively. We quantify the regression performance using the mean squared error (MSE) of the discovered neuronal formulae. Lower MSE values indicate better preservation of the underlying data characteristics.

5.1.2. Experimental Results

The performance comparison on the synthetic data is presented in

Table 2. Our proposed NeuronSeek-TD demonstrates consistent superiority over NeuronSeek-SR across all generated data, with particularly notable improvements on the data derived from the function

. This performance advantage remains robust under varying noise levels.

To assess computational efficiency, we measure the average execution time for both methods. NeuronSeek-TD achieves substantial computational savings, requiring less than half the execution time of the SR-based approach while maintaining comparable solution quality. These results collectively demonstrate that our method achieves both superior accuracy and greater computational efficiency.

5.2. Experiments on Uniqueness and Stability

Here, we demonstrate that NeuronSeek-SR exhibits instability in terms of resulting in divergent formulas under minor perturbations in initialization, while NeuronSeek-TD maintains good consistency.

5.2.1. Experimental Settings

Our experimental protocol consists of two benchmark datasets: the phoneme dataset (a classification task classifying nasal and oral sounds) and the airfoil self-noise dataset (a regression task modeling self-generated noise of airfoil). These public datasets are chosen from the OpenML website to represent both classification and regression tasks, ensuring a comprehensive evaluation across different problem types. For each dataset, we introduce four levels of Gaussian noise () to simulate real-world perturbations. We train 10 independent instances of each method under identical initialization. For comparison, NeuronSeek-SR based on GP uses a population of 3,000 candidates evolved over 20 generations, whereas NeuronSeek-TD methods—employing CP decomposition and Tucker decomposition—rely on a model optimized via Adam over 20 epochs.

To quantify the uniqueness of SR and TD methods, we track two diversity metrics:

Epoch-wise diversity represents the number of different formulas within each epoch (or generation) across all initializations. For instance, and are considered identical, whereas and are distinct.

Cumulative diversity measures the average number of unique formulas identified per initialization as the optimization goes on.

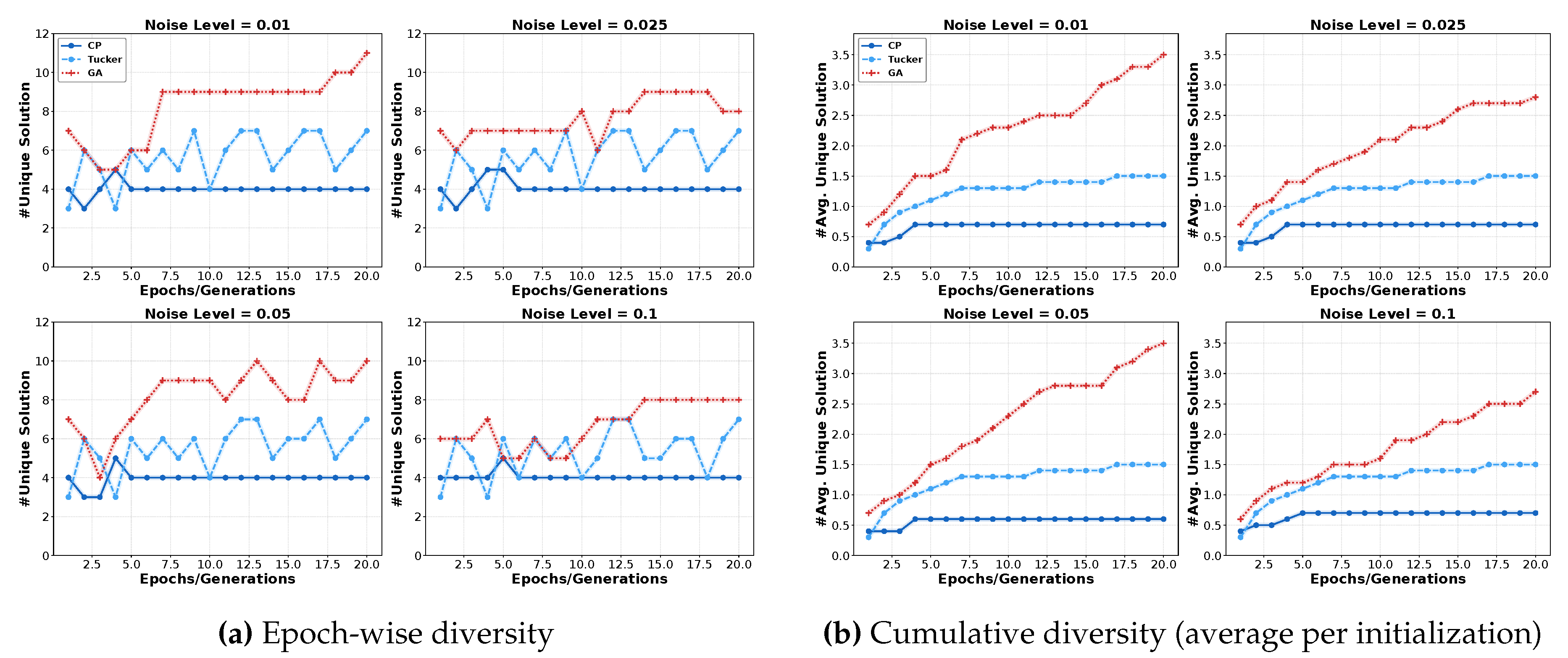

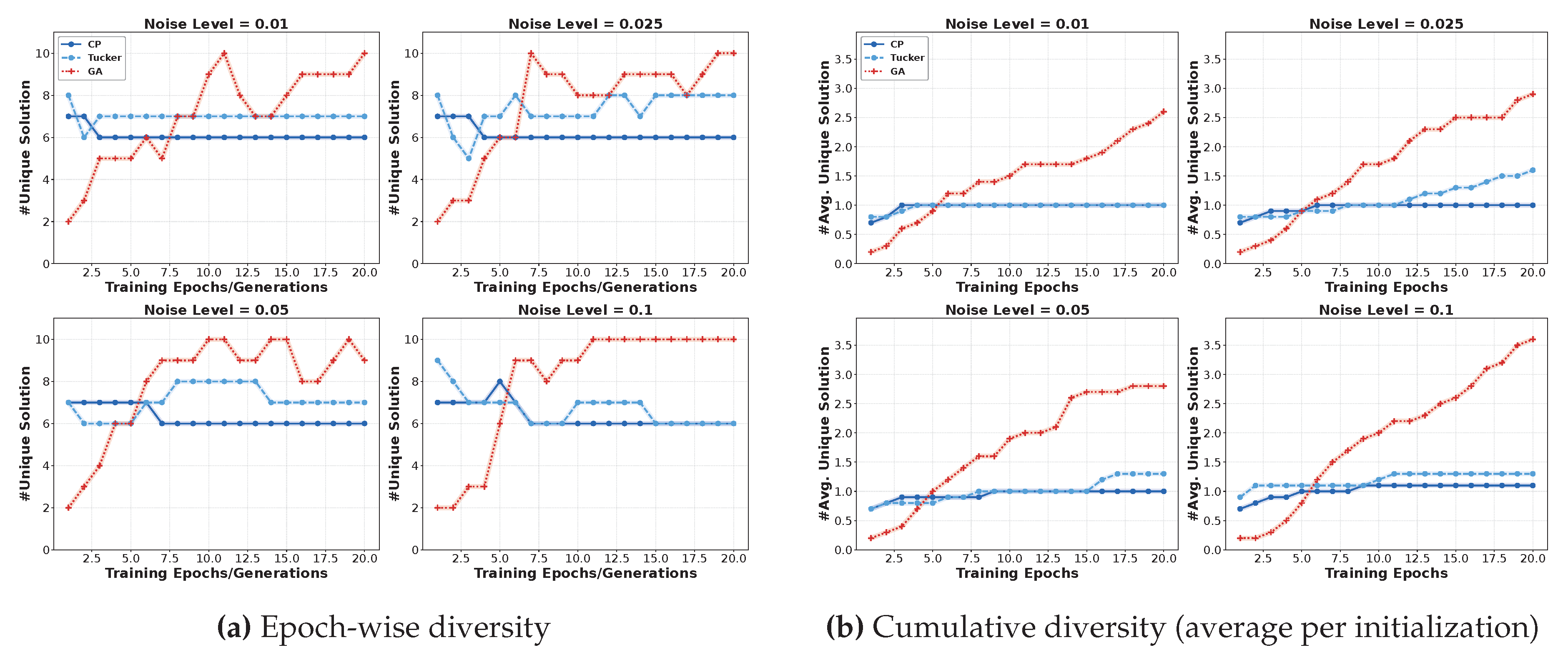

5.2.2. Experimental Results

The results of

phoneme and

airfoil self-noise datasets are depicted in

Figure 8 and

Figure 7, respectively. From the epoch-wise diversity (

Figure 8 (a) and

Figure 7 (a)), we have several important observations: Firstly, GP-based SR demonstrates a rapid increase in the number of discovered formulas within each epoch. After training, it produces more unique formulas compared to TD-based methods (CP and Tucker). This indicates that SR is sensitive to initialization conditions. Secondly, as noise levels increase, the GP method discovers nearly 10 distinct formulas across 10 initializations. With higher noise, every initialization produces a completely different formula structure. These behaviors highlight the instability of GP-based SR when dealing with noisy data, as minor perturbations in initialization or data noise can lead to substantially different symbolic expressions.

Furthermore, regarding cumulative diversity (

Figure 8(b) and

Figure 7(b)), we can observe that GP-based SR constantly discovers an increasing number of different formulas, while TD methods tend to stabilize during training. This indicates that the GP algorithm struggles to converge to a consistent symbolic formula. In contrast, the asymptotic behavior exhibited by TD-based methods demonstrates their superior stability and convergence properties when identifying symbolic expressions. Moreover, the CP-based method suggests the best resilience against initialization variability.

5.3. Superiority of NeuronSeek-TD over NeuronSeek-SR

To validate the superior performance of NeuronSeek-TD over NeuronSeek-SR, we conduct experiments across 16 benchmark datasets—8 for regression and 8 for classification—selected from scikit-learn and OpenML repositories. First, we use NeuronSeek-TD and NeuronSeek-SR simultaneously to search for the optimal formula. Second, we construct fully connected networks (FCNs) with neurons taking these discovered formulas as their aggregation functions. To verify the ability of NeuronSeek-TD, the structures of neural networks are carefully set, such that NeuronSeek-TD has equal or fewer parameters than NeuronSeek-SR.

Comprehensive implementation details and test results are provided in

Table 3. For regression tasks, the dataset is partitioned into training and test sets in an 8:2 ratio. The activation function is

with MSE as the loss function and

as the optimizer. For classification tasks, the same train-test split is applied, using the

activation function. The loss function and optimizer are set to CE and

, respectively. All experiments are repeated 10 times and reported by mean and standard deviation, with MSE for regression and accuracy for classification.

The regression results in

Table 3 demonstrate that NeuronSeek-SR exhibits larger fitting errors compared to NeuronSeek-TD, along with higher standard deviations in MSE values. A notable example is the

airfoil self-noise dataset, where NeuronSeek-TD outperforms NeuronSeek-SR by a significant margin, achieving a 9% reduction in MSE. Furthermore, NeuronSeek-TD shows superior performance on both the

California housing and

abalone datasets while utilizing fewer parameters. These results collectively indicate that NeuronSeek-TD possesses stronger regression capabilities than NeuronSeek-SR.

This performance advantage extends to classification tasks, where NeuronSeek-TD consistently achieves higher accuracy than NeuronSeek-SR. Particularly in the HELOC and orange-vs-grapefruit datasets, NeuronSeek-TD attains better classification performance with greater parameter efficiency. The observed improvements across both regression and classification tasks suggest that NeuronSeek-TD offers superior modeling capabilities compared to NeuronSeek-SR.

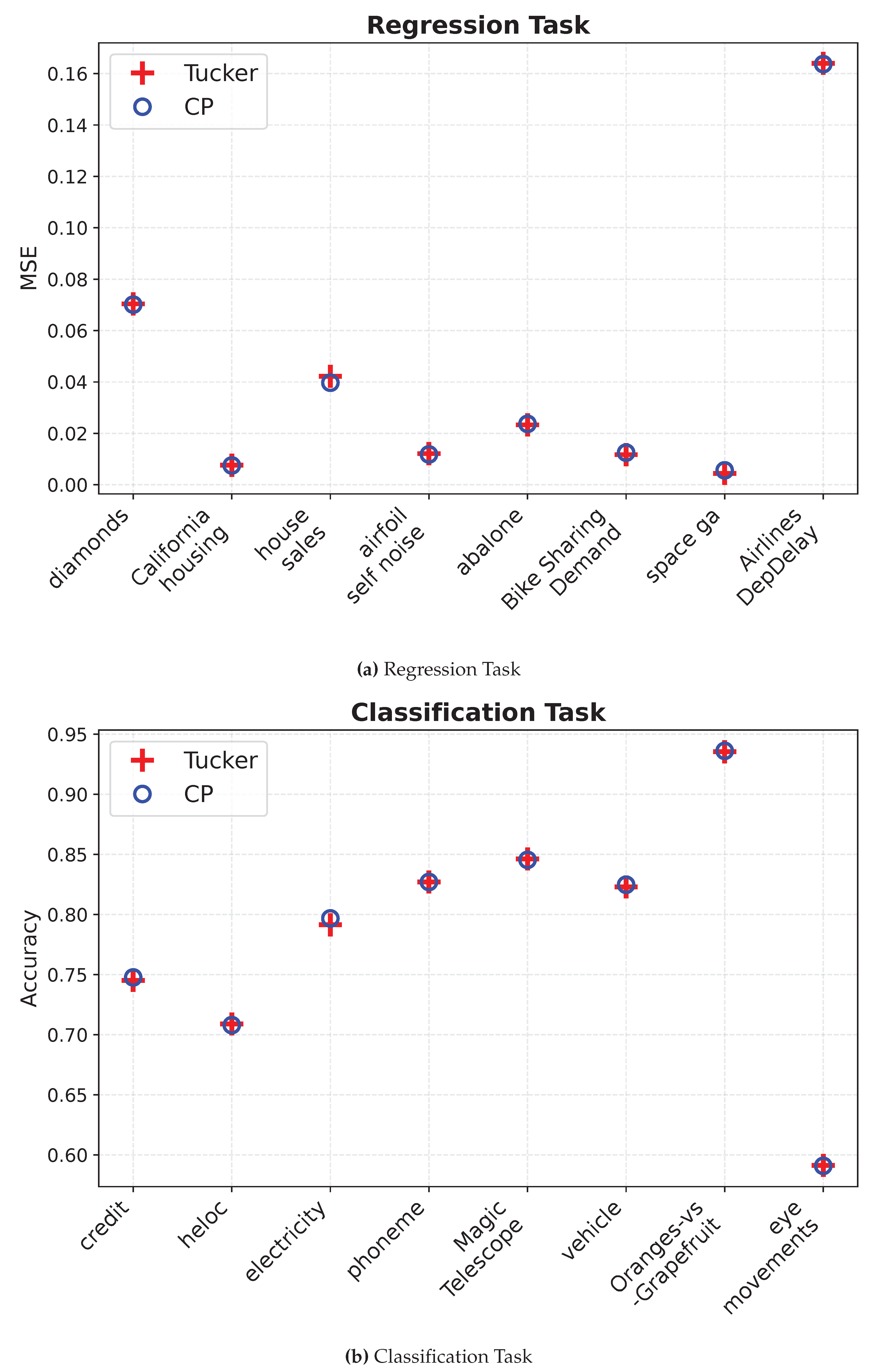

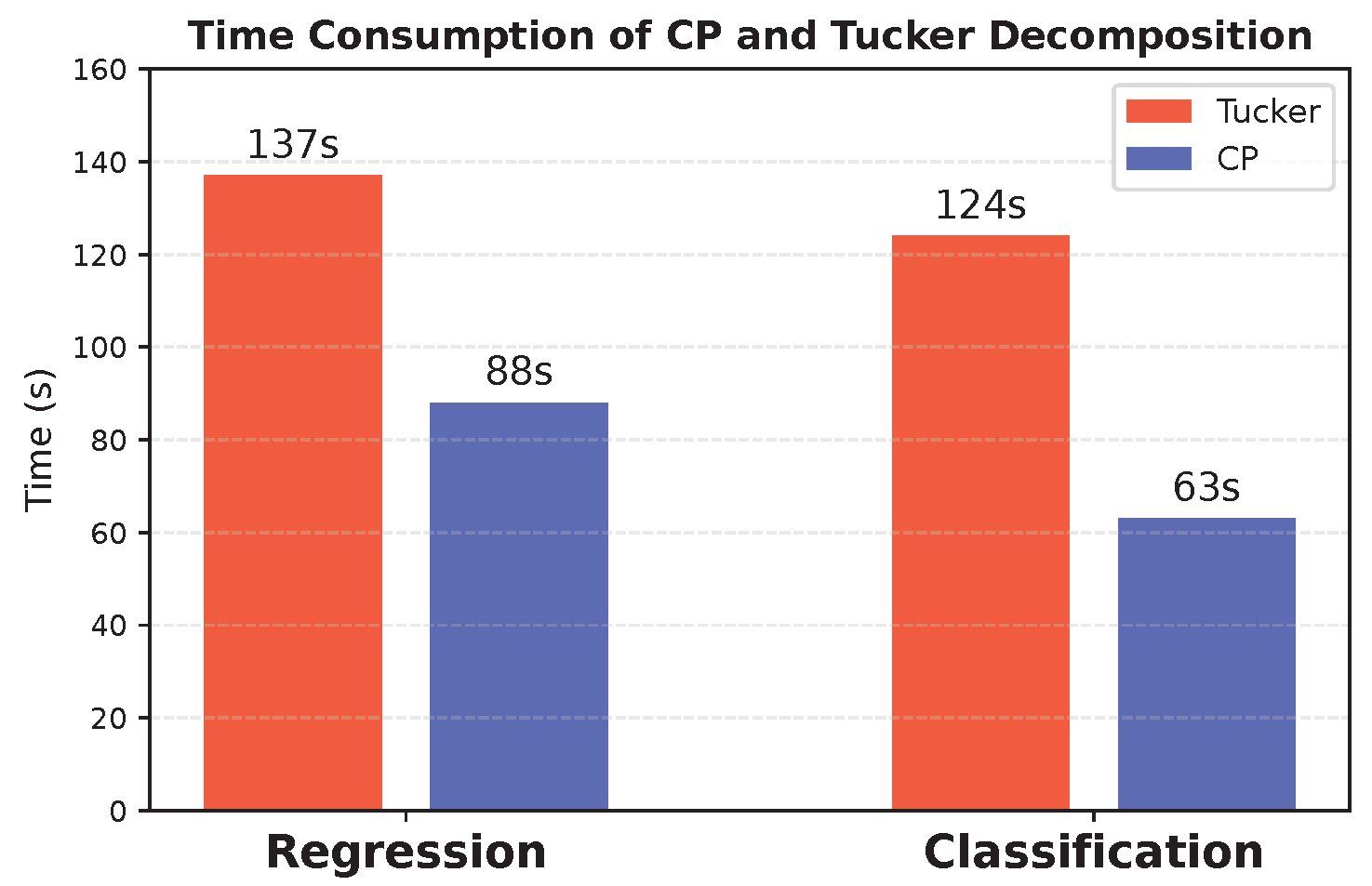

5.4. Comparison of Tensor Decomposition Methods

Our framework employs the CP decomposition for neuronal discovery. To empirically validate this choice, we conduct a comparative analysis of some tensor decomposition methods used in NeuronSeek-TD.

5.4.1. Experimental Settings

Generally, we follow the previous experimental settings in

Section 5.3: 16 tabular datasets and the same network structures as described in

Table 3. We adopt CP decomposition and Tucker decomposition respectively for tensor processing in NeuronSeek-TD. We employ MSE for regression tasks, while classification accuracy is utilized for classification tasks.

5.4.2. Experimental results

First,

Figure 9 illustrates that, for most datasets, the two decomposition methods exhibit comparable performance. Exceptions include

airfoil Self-Noise and

electricity datasets, where the two methods show slight performance differences. This observation suggests that variations in TD methods do not substantially impact the final results. Second, as shown in

Figure 10, the CP-based method achieves a 42% reduction in computational time. This result verifies that the CP method offers a computational advantage over the Tucker method.

Figure 1.

Task-driven neuron based on the vectorized symbolic regression (NeuronSeek-SR).

Figure 1.

Task-driven neuron based on the vectorized symbolic regression (NeuronSeek-SR).

Figure 2.

The overall framework of the proposed method. In the first stage, the input data, regardless of tables and images, are flattened into a vector representation and processed using an initial formula for neuronal search. A stable formula is then generated through CP decomposition. In the second stage, the neuronal formula is parameterized and integrated into various neural network backbones for task-specific applications.

Figure 2.

The overall framework of the proposed method. In the first stage, the input data, regardless of tables and images, are flattened into a vector representation and processed using an initial formula for neuronal search. A stable formula is then generated through CP decomposition. In the second stage, the neuronal formula is parameterized and integrated into various neural network backbones for task-specific applications.

Figure 4.

A sketch of our proof. In Steps 1 and 2, through interval partition, the approximation problem is transformed into a point-fitting problem. In Step 3, we use task-driven neurons to construct a unimodal function that can induce the dense trajectory. Then, composing the unimodal function can solve the point-fitting problem.

Figure 4.

A sketch of our proof. In Steps 1 and 2, through interval partition, the approximation problem is transformed into a point-fitting problem. In Step 3, we use task-driven neurons to construct a unimodal function that can induce the dense trajectory. Then, composing the unimodal function can solve the point-fitting problem.

Figure 5.

A polynomial can be transformed into a unimodal map.

Figure 5.

A polynomial can be transformed into a unimodal map.

Figure 6.

Given a set U with , it will always contain a tiny subset such that . Then, naturally , since .

Figure 6.

Given a set U with , it will always contain a tiny subset such that . Then, naturally , since .

Figure 7.

The uniqueness experiment on phoneme data.

Figure 7.

The uniqueness experiment on phoneme data.

Figure 8.

Uniqueness experiment on airfoil self-noise data.

Figure 8.

Uniqueness experiment on airfoil self-noise data.

Figure 9.

Comparison between CP and Tucker decomposition. (a) Performance comparison on regression tasks measured by MSE. (b) Performance comparison on classification tasks measured by accuracy.

Figure 9.

Comparison between CP and Tucker decomposition. (a) Performance comparison on regression tasks measured by MSE. (b) Performance comparison on classification tasks measured by accuracy.

Figure 10.

Comparison between CP and Tucker decomposition

Figure 10.

Comparison between CP and Tucker decomposition

Table 1.

A summary of the recently-proposed neurons. is the nonlinear activation function. ⊙ denotes Hadamard product. , , and the bias terms in these neurons are omitted for simplicity.

Table 1.

A summary of the recently-proposed neurons. is the nonlinear activation function. ⊙ denotes Hadamard product. , , and the bias terms in these neurons are omitted for simplicity.

| Works |

Formulations |

| Zoumponuris et al. (2017) [25] |

|

| Fan et al. (2018) [30] |

|

| Jiang et al. (2019) [26] |

|

| Mantini & Shah (2021) [27] |

|

| Goyal et al. (2020) [28] |

|

| Bu & Karpante (2021) [29] |

|

| Xu et al. (2022) [9] |

|

| Fan et al. (2024) [12] |

Task-driven polynomial |

Table 2.

Regression results (MSE) on synthetic data. represents the noise level.

Table 2.

Regression results (MSE) on synthetic data. represents the noise level.

| Ground Truth Formula |

|

|

|

Time (s) |

| |

SR |

TD |

SR |

TD |

SR |

TD |

SR |

TD |

|

0.0013 |

0.0008 |

0.0108 |

0.0120 |

0.0232 |

0.0138 |

13.94 |

4.46 |

|

0.0007 |

0.0006 |

0.0163 |

0.0095 |

0.0191 |

0.0166 |

12.75 |

6.69 |

|

0.0235 |

0.0028 |

0.2489 |

0.0102 |

0.1905 |

0.1706 |

28.77 |

7.73 |

|

0.0016 |

0.0012 |

0.0139 |

0.0101 |

0.0147 |

0.0116 |

22.01 |

8.82 |

|

0.0095 |

0.0067 |

0.0116 |

0.0086 |

0.0495 |

0.0064 |

15.16 |

5.80 |

|

0.0011 |

0.0002 |

0.0230 |

0.0165 |

0.0561 |

0.0193 |

24.77 |

9.44 |

|

0.0055 |

0.0014 |

0.0125 |

0.0104 |

0.0416 |

0.0109 |

15.80 |

8.21 |

|

0.0102 |

0.0062 |

0.0134 |

0.0111 |

0.0170 |

0.0126 |

13.30 |

8.24 |

Table 3.

Comparison of the network built by neurons using formulas generated by NeuronSeek-SR and NeuronSeek-TD. The number means that this network has k hidden layers, each with neurons. For example, 5-3-1 means this network has two hidden layers with 5 and 3 neurons respectively in each layer.

Table 3.

Comparison of the network built by neurons using formulas generated by NeuronSeek-SR and NeuronSeek-TD. The number means that this network has k hidden layers, each with neurons. For example, 5-3-1 means this network has two hidden layers with 5 and 3 neurons respectively in each layer.

| Datasets |

Instances |

Features |

Classes |

Metrics |

Structure |

Test results |

| |

|

|

|

|

TN |

NeuronSeek-TD |

NeuronSeek-SR |

NeuronSeek-TD |

| California housing |

20640 |

8 |

continuous |

MSE |

6-4-1 |

6-3-1 |

0.0720 ± 0.0024 |

0.0701 ± 0.0014 |

| house sales |

21613 |

15 |

continuous |

|

6-4-1 |

6-4-1 |

0.0079 ± 0.0008 |

0.0075 ± 0.0004 |

| airfoil self-noise |

1503 |

5 |

continuous |

|

4-1 |

3-1 |

0.0438 ± 0.0065 |

0.0397 ± 0.0072 |

| diamonds |

53940 |

9 |

continuous |

|

4-1 |

4-1 |

0.0111 ± 0.0039 |

0.0102 ± 0.0015 |

| abalone |

4177 |

8 |

continuous |

|

5-1 |

4-1 |

0.0239 ± 0.0024 |

0.0237 ± 0.0027 |

| Bike Sharing Demand |

17379 |

12 |

continuous |

|

5-1 |

5-1 |

0.0176 ± 0.0026 |

0.0125 ± 0.0146 |

| space ga |

3107 |

6 |

continuous |

|

2-1 |

2-1 |

0.0057 ± 0.0029 |

0.0056 ± 0.0030 |

| Airlines DepDelay |

8000 |

5 |

continuous |

|

4-1 |

4-1 |

0.1645 ± 0.0055 |

0.1637 ± 0.0052 |

| credit |

16714 |

10 |

2 |

ACC |

6-2 |

6-2 |

0.7441 ± 0.0092 |

0.7476 ± 0.0092 |

| heloc |

10000 |

22 |

2 |

|

18-2 |

17-2 |

0.7077 ± 0.0145 |

0.7089 ± 0.0113 |

| electricity |

38474 |

8 |

2 |

|

5-2 |

5-2 |

0.7862 ± 0.0075 |

0.7967 ± 0.0087 |

| phoneme |

3172 |

5 |

2 |

|

8-5 |

7-5 |

0.8242 ± 0.0207 |

0.8270 ± 0.0252 |

| MagicTelescope |

13376 |

10 |

2 |

|

6-2 |

6-2 |

0.8449 ± 0.0092 |

0.8454 ± 0.0079 |

| vehicle |

846 |

18 |

4 |

|

10-2 |

10-2 |

0.8176 ± 0.0362 |

0.8247 ± 0.0354 |

| Oranges-vs-Grapefruit |

10000 |

5 |

2 |

|

8-2 |

7-2 |

0.9305 ± 0.0160 |

0.9361 ± 0.0240 |

| eye movements |

7608 |

20 |

2 |

|

10-2 |

10-2 |

0.5849 ± 0.0145 |

0.5908 ± 0.0164 |

Table 4.

Details of real-world tabular datasets.

Table 4.

Details of real-world tabular datasets.

| Dataset |

Task |

Data Size |

Features |

| Electron Collision Prediction |

Regression |

99,915 |

16 |

| Asteroid Prediction |

Regression |

137,636 |

19 |

| Heart Failure Detection |

Classification |

1,190 |

11 |

| Stellar Classification |

Classification |

100,000 |

17 |

Table 5.

The test results of different models on real-world datasets.

Table 5.

The test results of different models on real-world datasets.

| Method |

electron collision (MSE) |

asteroid prediction (MSE) |

heartfailure (F1) |

Stellar Classification (F1) |

| XGBoost |

0.0094 ± 0.0006 |

0.0646 ± 0.1031 |

0.8810 ± 0.02 |

0.9547 ± 0.002 |

| LightGBM |

0.0056 ± 0.0004 |

0.1391 ± 0.1676 |

0.8812 ± 0.01 |

0.9656 ± 0.002 |

| CatBoost |

0.0028 ± 0.0002 |

0.0817 ± 0.0846 |

0.8916 ± 0.01 |

0.9676 ± 0.002 |

| TabNet |

0.0040 ± 0.0006 |

0.0627 ± 0.0939 |

0.8501 ± 0.03 |

0.9269 ± 0.043 |

| TabTransformer |

0.0038 ± 0.0008 |

0.4219 ± 0.2776 |

0.8682 ± 0.02 |

0.9534 ± 0.002 |

| FT-Transformer |

0.0050 ± 0.0020 |

0.2136 ± 0.2189 |

0.8577 ± 0.02 |

0.9691 ± 0.002 |

| DANETs |

0.0076 ± 0.0009 |

0.1709 ± 0.1859 |

0.8948 ± 0.03 |

0.9681 ± 0.002 |

| NeuronSeek-SR |

0.0016 ± 0.0005 |

0.0513 ± 0.0551 |

0.8874 ± 0.05 |

0.9613 ± 0.002 |

| NeuronSeek-TD (ours) |

0.0011 ± 0.0003 |

0.0502 ± 0.0800 |

0.9023 ± 0.03 |

0.9714 ± 0.001 |

Table 6.

Accuracy of compared methods on small-scale image datasets.

Table 6.

Accuracy of compared methods on small-scale image datasets.

| |

CIFAR10 |

CIFAR100 |

SVHN |

STL10 |

| ResNet18 |

0.9419 |

0.7385 |

0.9638 |

0.6724 |

| NeuronSeek-ResNet18 |

0.9464 |

0.7582 |

0.9655 |

0.7005 |

| DenseNet121 |

0.9386 |

0.7504 |

0.9636 |

0.6216 |

| NeuronSeek-DenseNet121 |

0.9399 |

0.7613 |

0.9696 |

0.6638 |

| SeResNet101 |

0.9336 |

0.7382 |

0.9650 |

0.5583 |

| NeuronSeek-SeResNet101 |

0.9385 |

0.7720 |

0.9685 |

0.6560 |

| GoogleNet |

0.9375 |

0.7378 |

0.9644 |

0.7241 |

| NeuronSeek-GoogleNet |

0.9400 |

0.7519 |

0.9658 |

0.7298 |