1. Introduction

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TCM) is a reversible form of cardiomyopathy primarily observed in postmenopausal women. TCM, often referred to as broken heart syndrome, stress cardiomyopathy, or apical ballooning syndrome, was first documented in Japan in 1990. It represents 1–2% of patients with acute coronary syndrome, with an overwhelming female predominance (89.8%) and a mean age of 66.8 years [

1]. TCM has attracted significant attention in the field of cardiovascular diseases. Despite various proposed hypotheses, no specific etiology has been identified to explain its occurrence in this population. Contemporary literature suggests that the neurocardiac axis plays a crucial role in TCM pathophysiology.

Adrenal insufficiency (AI) is characterized by an inadequate production of glucocorticoids, primarily cortisol, which are essential for the body's response to stress. Cortisol plays a pivotal role in modulating the cardiovascular system by maintaining vascular tone and regulating catecholamine sensitivity. Cortisol deficiency can disrupt this balance, potentially leading to cardiovascular manifestations. Emerging evidence suggests a link between AI and TCM. While TCM is often associated with acute stressors that lead to a surge in catecholamines, the absence of adequate cortisol may exacerbate the myocardial response to these catecholamines, resulting in transient left ventricular dysfunction, a characteristic of TCM. Reports of TCM in patients with AI highlight their potential relationship [

2,

3].

Given the limited data on TCM outcomes in patients with AI, we analyzed a comprehensive national administrative claims database to better understand the clinical outcomes in this specific patient population. We hypothesized that AI would be associated with poor cardiovascular outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials, Methods, and Ethics Statement

This study examined records from the Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD) covering 5 years from January 1, 2016, to December 31, 2020. The NRD, which is part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project overseen by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality in the US, contains publicly accessible, de-identified information, eliminating the need for institutional review board approval [

4,

5]. We included patients aged ≥18 years who were hospitalized primarily for TCM, as indicated by the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) code I51.81. The patients were categorized into two groups depending on AI status (ICD-10-CM codes E271, E273, E2740, E2749) or not. In-hospital mortality was the primary outcome measure. The secondary outcomes included all-cause readmission within 90 days, acute kidney injury (AKI), mechanical ventilation use, vasopressor administration, cardiogenic shock, average hospital stay duration, and overall hospitalization expenses. Additionally, we identified baseline demographic and clinical characteristics using specific ICD-10-CM codes. These included the prevalence of type 1 and 2 diabetes, heart failure, dyslipidemia, hypertension, prior acute myocardial infarction (AMI), stroke, and hypothyroidism.

2.2. Study Population

Adult patients (>18 years) in the NRD database diagnosed with TCM (ICD-10 Code I51.81, referring to Takotsubo Syndrome) in 2024 were selected. Patients with a secondary diagnosis of AI [ICD-10 codes E27.1 [Primary adrenocortical insufficiency], E27.2 [Addisonian crisis], and E27.4 [Other and unspecified adrenocortical insufficiency]) were selected. The patients were grouped according to age, as shown in

Table 1.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

The survey weights, strata, and clustering variables from the NRD were incorporated into the analysis to produce nationally representative estimates with accurate standard errors. The patient demographic profiles were summarized using descriptive statistical methods. We calculated both unadjusted odds ratios (uORs) and adjusted odds ratios (aORs) to examine the association between adrenal insufficiency and outcome measures. The unadjusted ORs were determined using univariate logistic regression. Subsequently, we constructed multivariate logistic regression models to derive aORs, controlling for potential confounders, including age, sex, insurance coverage type, average household income by zip code, and comorbidity burden (assessed using the Deyo-modified Charlson Comorbidity Index [CCI]). For statistical comparisons between groups, continuous variables were analyzed using Student's t-test, while categorical variables were evaluated using the Rao-Scott chi-square test. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 18.0, with p<0.05 considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using Stata Corp. 2025. Stata Statistical Software: Release 18.0. College Station, TX, StataCorp, LLC.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

Among the 30,987 patients admitted with a primary diagnosis of TCM, 0.59% (183 patients) had a secondary diagnosis of AI. Patients with AI were younger (mean age: 66.1 years vs. 67.0 years) and had a significantly higher CCI (mean: 2.67 vs. 1.78, p<0.001). Patients with AI were also more likely to have hypothyroidism (30% vs. 19%, p=0.017), diabetes type 1 (1.9% vs. 0.37%, p=0.011), diabetes type 2 (31% vs. 20%, p=0.018), all-cause anemia (16.2% vs. 6.7%, p<0.001), and heart failure (50.1% vs. 33.3%, p=0.001) than those without AI. Hyperthyroidism, prior AMI, prior stroke, alcohol use, hypertension, dyslipidemia, tobacco use, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD_ did not differ between the groups. The baseline characteristics of patients with TCM stratified by the presence or absence of AI are shown in

Table 2.

3.2. Primary and Secondary Outcomes

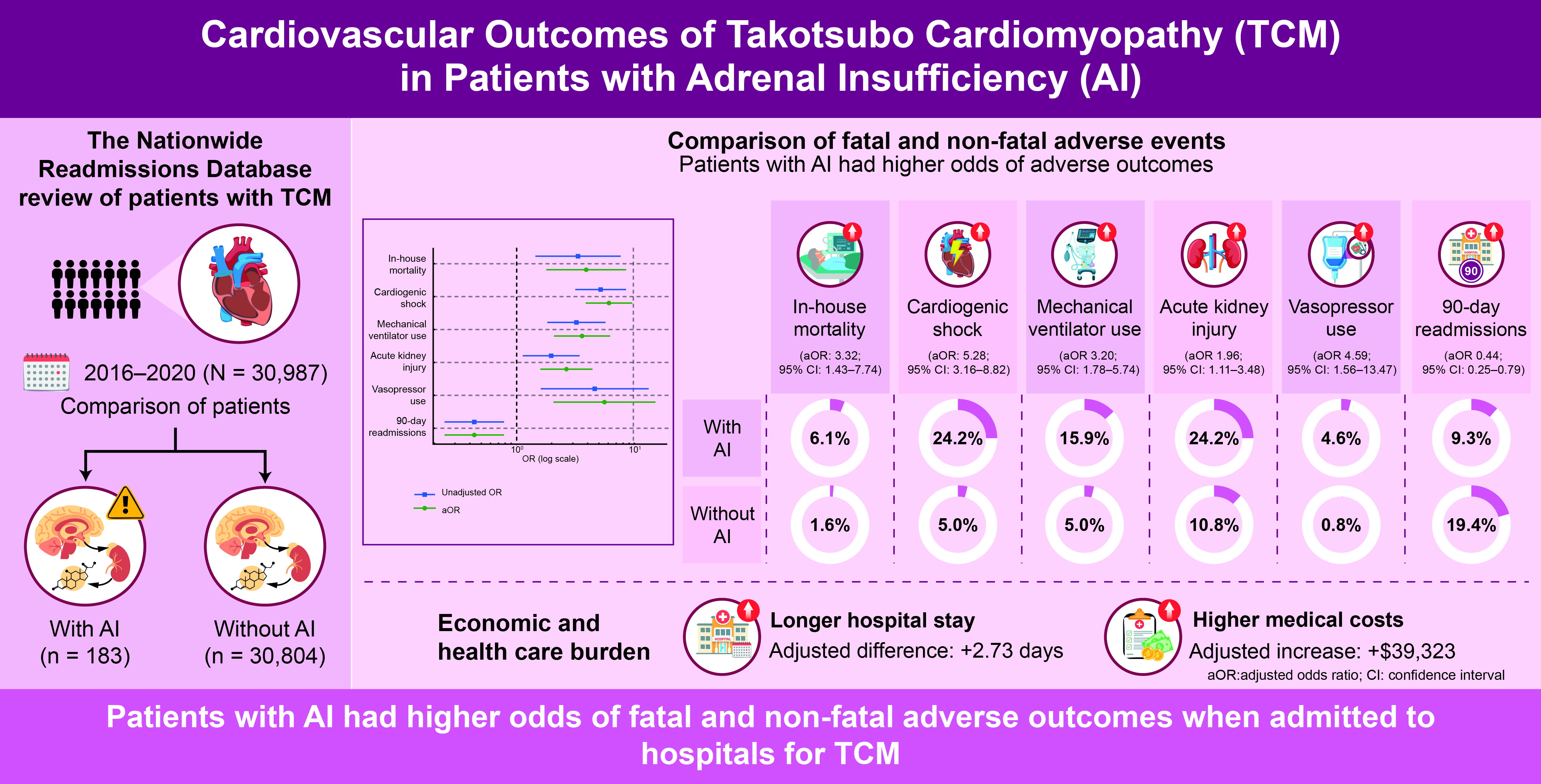

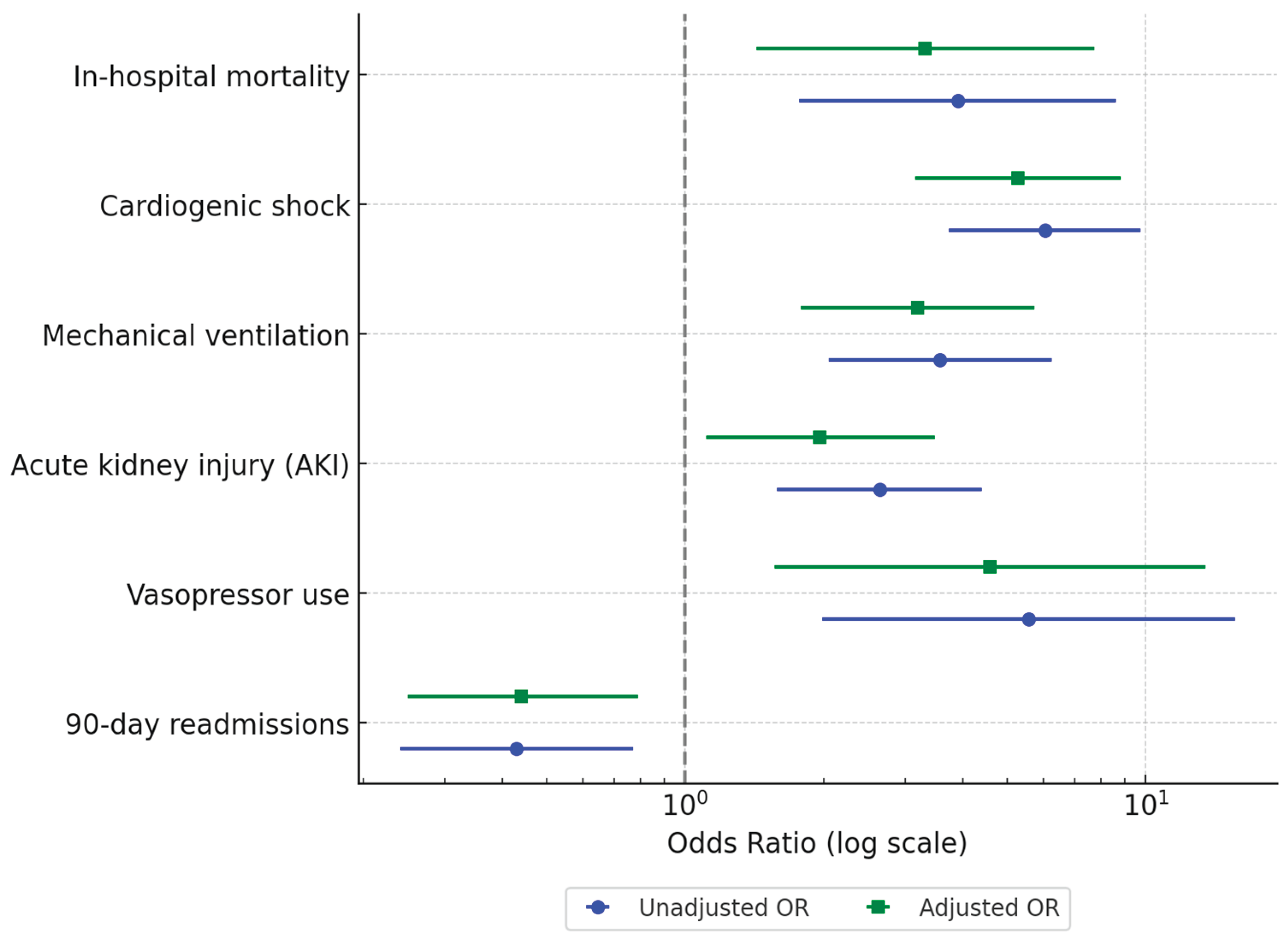

In the unadjusted analysis, patients with AI had significantly higher odds of experiencing adverse outcomes than those without AI. Specifically, AI was associated with increased in-hospital mortality (6.1% vs. 1.6%; unadjusted OR [uOR] 3.91, 95% CI 1.77–8.63, p=0.001), cardiogenic shock (24.2% vs. 5.0%; uOR 6.04, 95% CI 3.74–9.75, p<0.001), and mechanical ventilation use (15.9% vs. 5.0%; uOR 3.57, 95% CI 2.05–6.24, p<0.001). AKI was also more frequent in the AI group (24.2% vs. 10.8%; uOR 2.64, 95% CI 1.58–4.40, p<0.001), as was vasopressor use (4.6% vs. 0.8%; uOR 5.56, 95% CI 1.98–15.65, p=0.001). Interestingly, all-cause 90-day readmissions were significantly lower in the AI group (19.4% vs. 9.3%; uOR 0.43, 95% CI 0.24–0.77, p=0.004) (

Table 3).

After adjusting for baseline characteristics, AI remained independently associated with adverse in-hospital outcomes. The aORs indicated higher odds of in-hospital mortality (aOR 3.32, 95% CI 1.43–7.74, p=0.005), cardiogenic shock (aOR 5.28, 95% CI 3.16–8.82, p<0.001), and mechanical ventilation use (aOR 3.20, 95% CI 1.78–5.74, p<0.001). Adjusted analyses also confirmed increased odds of AKI (aOR 1.96, 95% CI 1.11–3.48, p=0.021) and vasopressor use (aOR 4.59, 95% CI 1.56–13.47, p=0.006). Additionally, AI was associated with significantly lower odds of all-cause 90-day readmissions (aOR 0.44, 95% CI 0.25–0.79, p=0.006) (

Table 4,

Figure 1).

3.3. Length of Stay and Hospital Charges

Among patients with TCM, the mean hospital length of stay (LOS) was 6.84 days for patients with AI vs. 3.67 days for those without AI (p<0.001). The adjusted LOS was significantly longer in patients with AI compared to those without AI (adjusted LOS increase: 2.73 days, 95% CI 1.39–4.06 days, p<0.001). The mean total hospital charges were $97,419 and $54,574 for patients with and without AI, respectively (p<0.001). The adjusted total charges were significantly higher in patients with AI than in those without AI (adjusted charge increase: $39,323, 95% CI $14,083–$64,563, p=0.002).

4. Discussion

TCM remains a diagnosis of exclusion and is commonly identified in postmenopausal women presenting with acute coronary syndrome. Typical presentations include acute coronary syndrome and systolic dysfunction without evidence of epicardial coronary artery disease. Although various morphological patterns exist, the most typical presentation includes apical hypokinesis coupled with hyperkinesis in the basal segments. Typically, wall motion abnormalities extend beyond the perfusion territory of epicardial coronary arteries. Although various hypotheses have been proposed, no confirmatory evidence has been proposed to explain the pathophysiology of TCM. Catecholamine excess, microvascular dysfunction, and impaired myocardial calcium handling have been widely discussed in the context of current research aimed at identifying their mechanistic etiologies. A paradoxical relationship exists between cortisol levels and myocardial function. Although the concept of a catecholamine surge leading to TCM has been increasingly reported, AI involves adrenergic receptor upregulation, especially myocardial beta receptors, in the absence of cortisol, which can lead to increased sensitivity to normal or low catecholamine levels [

2]. Additionally, the neuroendocrine feedback mechanism is impaired, resulting in excessive sympathetic stimulation in stressful situations. Cortisol exerts cardioprotective effects by regulating calcium homeostasis, thereby preventing the undue impact of catecholamine surges. However, this protective effect is abolished in the absence of cortisol, leading to myocardial injury and dysfunction [

3].

The results of the analysis in the present study revealed that, among patients hospitalized for TCM, those with AI were younger and had a significantly higher comorbidity burden. Additionally, among TCM hospitalizations, AI was associated with a higher prevalence of hypothyroidism, type 1 diabetes (1.9% vs. 0.37%, p=0.011), type 2 diabetes, anemia, and heart failure. These findings align with existing literature suggesting that patients with AI often present with complex metabolic and cardiovascular comorbidities, contributing to poorer outcomes [

2,

3]. Type 2 diabetes and hypothyroid disorders have shown independent worse outcomes in such scenarios, which can be explained partially by shared immunological patterns in AI, diabetes, and hypothyroidism as known in type 2 polyglandular syndrome [

6]. The occurrence of anemia in patients with AI can be attributed to impaired erythropoiesis [

7]. Additionally, heart failure often manifests as a lack of vasomotor response, direct myocardial inhibition, and electrolyte imbalance [

8,

9].

Among patients hospitalized for TCM, AI was associated with higher odds of in-hospital mortality, cardiogenic shock, mechanical ventilation, vasopressor use, and AKI. These findings align with those of previous studies demonstrating that AI strongly predicts poor outcomes in critically ill patients [

10,

11]. Despite higher in-hospital complication rates, the 90-day readmission rates in the AI group were unexpectedly lower in the present study. This could reflect a high in-hospital mortality rate, limiting subsequent readmissions, or more comprehensive outpatient follow-up care for patients with AI.

Economically, patients with AI experienced a significantly longer hospital length of stay (LOS) (6.84 vs. 3.67 days, p < 0.001) and higher hospital charges (

$97,419 vs.

$54,574, p<0.001). The adjusted LOS was 2.73 days longer (95% CI 1.39–4.06 days, p<0.001), and hospital charges were

$39,323 higher (95% CI

$14,083–

$64,563, p=0.002). These findings underscore the economic burden associated with managing stress-related cardiovascular diseases and the healthcare burden associated with adrenal insufficiency, consistent with previous studies showing higher costs for patients with complex comorbidities [

9,

12].

This study has several limitations. First, this study relied on database analysis and diagnostic codes to retrospectively identify patients, which introduces the potential for diagnostic bias. Consequently, the population may have been under- or over-diagnosed. Second, owing to the presence of other covariates that may confound the outcomes, establishing causality is difficult. Third, recurrent hospitalizations of the same patient may be counted as separate cases, leading to an overrepresentation of the pathology. Fourth, we were unable to confirm whether AI was a primary or secondary diagnosis, which may have influenced prognostic outcomes. Finally, we could not assess AI severity as this information was not included in the database.

5. Conclusions

Despite the abovementioned limitations, the results of this study highlight the significant association between poorer cardiovascular outcomes and longer hospital stays in patients with AI linked to TCM. Further randomized controlled trials and other investigations in this population are essential to explore additional strategies for managing these patients and improving their health metrics.

Author Contributions

NJ, SA, GM and NA have contributed to the manuscript's conception, drafting, and reading. NA performed statistical analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

None of the authors received any financial support for this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the use of publicly accessible, anonymized patient data.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the use of publicly accessible, anonymized patient data.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Professional services were hired through the Hennepin Healthcare for finalizing the article and edit the graphical abstract. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors has any relationship with industry.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACS |

acute coronary syndrome |

| AE |

adverse events |

| AI |

adrenal insufficiency |

| AKI |

acute kidney injury |

| aOR |

adjusted odds ratio |

| CI |

confidence interval |

| LOS |

length of stay |

| NRD |

Nationwide Readmissions Database |

| TCM |

takotsubo cardiomyopathy |

| THC |

total hospitalization charges |

| uOR |

unadjusted odds ratio |

References

- Krittanawong, C.; Qadeer, Y.K.; Ang, S.P.; Wang, Z.; Alam, M.; Sharma, S.; et al. Incidence and in-hospital mortality among women with acute myocardial infarction with or without SCAD. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2025, 50, 102921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidari, A.; Ghorbani, M.; Hassanzadeh, S.; Rahmanipour, E. A review of the interplay between Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and adrenal insufficiency: Catecholamine surge and glucocorticoid deficiency. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2024, 87, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Templin, C.; Ghadri, J.R.; Diekmann, J.; Napp, L.C.; Bataiosu, D.R.; Jaguszewski, M.; et al. Clinical features and outcomes of Tako-tsubo (Stress) cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Introduction to the HCUP National Inpatient Sample (NIS). December 2020. Available online: https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/NIS_Introduction_2020.jsp (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Elixhauser, A.; McCarthy, E. Clinical Classifications for Health Policy Research, Version 2: Hospital Inpatient Statistics; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research: Rockville, MD, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Husebye, E.S.; Anderson, M.S.; Kämpe, O. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1132–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charmandari, E.; Nicolaides, N.C.; Chrousos, G.P. Adrenal insufficiency. Lancet 2014, 383, 2152–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahner, S.; Allolio, B. Management of adrenal insufficiency in different clinical settings. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2005, 6, 2407–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bancos, I.; Hazeldine, J.; Chortis, V.; Hampson, P.; Taylor, A.E.; Lord, J.M.; et al. Primary adrenal insufficiency is associated with impaired natural killer cell function: a potential link to increased mortality. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2017, 176, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Téblick, A.; Peeters, B.; Langouche, L.; Van Den Berghe, G. Adrenal function and dysfunction in critically ill patients. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalegrave, D.; Silva, R.L.; Becker, M.; Gehrke, L.V.; Friedman, G. Insuficiência adrenal relativa como preditora de gravidade de doença e mortalidade do choque séptico. Rev. Bras. Ter. Intensiva 2012, 24, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slavin, S.D.; Khera, R.; Zafar, S.Y.; Nasir, K.; Warraich, H.J. Financial burden, distress, and toxicity in cardiovascular disease. Am. Heart J. 2021, 238, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).