1. Introduction

Historical documents contain valuable and helpful information in all scientific and literary fields. However, these documents can suffer damage because of many factors: the quality of the documents themselves may be poor, the preservation methods may expose them to external moisture, and the ink used may also be of poor quality. All of these factors can cause problems in determining who wrote the document.

In historical documents, identifying the writer provides valuable insights into the origins and authenticity of the text, as well as contributes to our understanding of historical writing practices and cultural exchanges.

Writer identification is the process of determining the writer’s name attributing documents written by an unknown writer to a well-known writer [

11].

This process can be done in two main ways:

1. Text Dependent: These methods rely on specific text samples provided by the writer. Features are extracted based on the content of the text, such as characters, words, or phrases. These methods achieve good identification accuracy, especially when the provided text samples are rich and varied.

2. Text Independent: These methods do not rely on specific text samples; instead, they analyze general characteristics of handwriting style. Features are extracted based on overall handwriting patterns, such as curvature, strokes, or texture. This approach is more applicable for large and diverse datasets, as they don’t require specific text samples. It is advantageous when dealing with historical documents or situations where specific text samples are unavailable [

1].

In this paper, we adopted a text-independent approach since we lack exact samples of the authors handwriting for direct comparison. However, this method is not always precise, as it relies on general writing styles, which can vary significantly. Individuals exhibit diverse handwriting patterns depending on context, content, and personal habits, leading to substantial variability in writing styles

The writer’s Identification of Arabic Historical documents presents two challenges [

1].

First, the challenge due to Arabic Script: The Arabic script has 28 letters, is cursive, and is written from right to left. Each letter can have up to four fundamental shapes as shown in

Table 1.

Second, the challenge due to the nature of historical documents arises from degradation over time, such as:

Chemical deteriorations occur due to temperature changes.

Biodegradation is caused by living organisms.

Human degradations such as scratches occur.

Degradation is brought on by the digitizing process.

In this study, we propose a deep learning-based approach for writer identification in Arabic historical documents using two Convolutional Neural network models: DeepWriter and Half DeepWriter. We employed a subset of the WAHD dataset comprising 16,491 images and applied data augmentation techniques to enhance model generalization. The main contributions of this work include the application of dual-path and single-path CNN architectures tailored for Arabic script, a systematic evaluation of learning rates to optimize performance, and the use of additional unseen data to test model generalization, which enhances the robustness and applicability of our method for real-world historical document analysis.

To achieve this idea, we posed this research questions:

Q1: How effective is the DeepWriter model in identifying authors in Arabic historical documents?

Q2: How effective is the Half DeepWriter model in identifying authors in Arabic historical documents?

Q3: How does the performance of the DeepWriter and Half DeepWriter models compare in the author identification task?

Q4: How does the performance of the two models compare with the latest paper versions used in analyzing Arabic historical documents?

Q5: What is the impact of different repetition rate (learning rate) values on the performance of the DeepWriter and Half DeepWriter models?

Q6: What are the challenges and findings related to identifying unknown authors in Arabic historical documents? And how can we adapt to developments in this type of data?

The main Contributions of this Study:

Two deep learning-based models (DeepWriter and Half DeepWriter) are used to identify authors in Arabic historical documents.

Apply correlations to a portion of the WAHD database with a 60% distribution of known authors and 40% of unknown authors.

Perform a comparative analysis of the scripts using different designs to determine the best training settings.

Evaluate the results using precision, precision, recall, and mean (F1-score) criteria, including data from authors on which the training model is tested.

Ensure good results for scripts based on convolutional networks, including degraded documents and unknown writings.

Identify digital details by supporting author identifiers for the absence of cultural heritage in historical Arabic documents.

The related works cited in this paper were selected based on their relevance to writer identification. Preference was given to recent and widely cited studies. This paper was included to show all Arabic historical studies in writer identification field.

2. Related Work

In Asi. and Abdalhaleem [

5] for data preprocessing used Gabor-based coarse segmentation with Markov random fields and then produce a binarized version. For feature extraction, a number of features are computed, such as CBF ( Contour-Based Feature); M-CBF (Modified Contour-Based Feature); OBI (Oriented Basic Image); G-SIFT (GPU Scale-Invariant Feature Transform); G-SURF (GPU Speeded Up Robust Features); HR-SIFT (High-Resolution Scale-Invariant Feature Transform); and HE-SIFT (Histogram Equalized Scale-Invariant Feature Transform) on a part of WAHD from IHP. Many schemes are used in classification, such as Voting, Weighted Voting (W-Voting), Averaging, and the Nearest Neighbor (NN) classifier. The best results are as follows: CBF with W-Voting: 48.22, M-CBF with W-Voting 76.0, OBI with W-voting: 76.0, G-SIFT with w-voting:81, G-SURF with voting:76, HR-SIFT with w-voting:76, HE-SIFT with th W-voting:79.

Deep CNN in Writer Identification

CNN is used to extract features from handwritten and historical images.

A Deep CNN is a type of CNN with a deep architecture, meaning it contains a large number of layers. There are many types of Deep CNN.

Here is a review of the types used in writer identification for Arabic historical documents:

1.ResNet20 is a type of deep convolutional neural network with a depth of 20 layers known as a Residual Network.

Figure 1 shows the ResNet20 structure

In M. Chammas [

3] a feature extraction system was built using SIFT and then PCA (+Whitening) is applied. The random samples from the SIFT vectors processed by PCA, which stands for Principal Component Analysis, are clustered into 5000 clusters using the k-means algorithm. Then, they trained using ResNet20. After training, VLAD encoding, which stands for Vector of Locally Aggregated Descriptors is used to convert the clusters into vectors. Cosine distance and SVM are used to determine the similarity. Additionally, a private database for historical Arabic manuscripts was built called Balamand. The model achieved a result of 99.11% in the Balamand data set.

2. AlexNet64 is a type of deep convolutional neural network consisting of multiple convolutional layers followed by max-pooling layers and fully connected layers.

Durou, Amal M and Aref [

4] used Alex-Net as the feature extraction phase. Then, for classification, an SVM (Support Vector Machine) is used. This model is applied to two Arabic historical datasets (IHP and Clusius). It achieves 99% accuracy on IHP and 91% on Clusius.

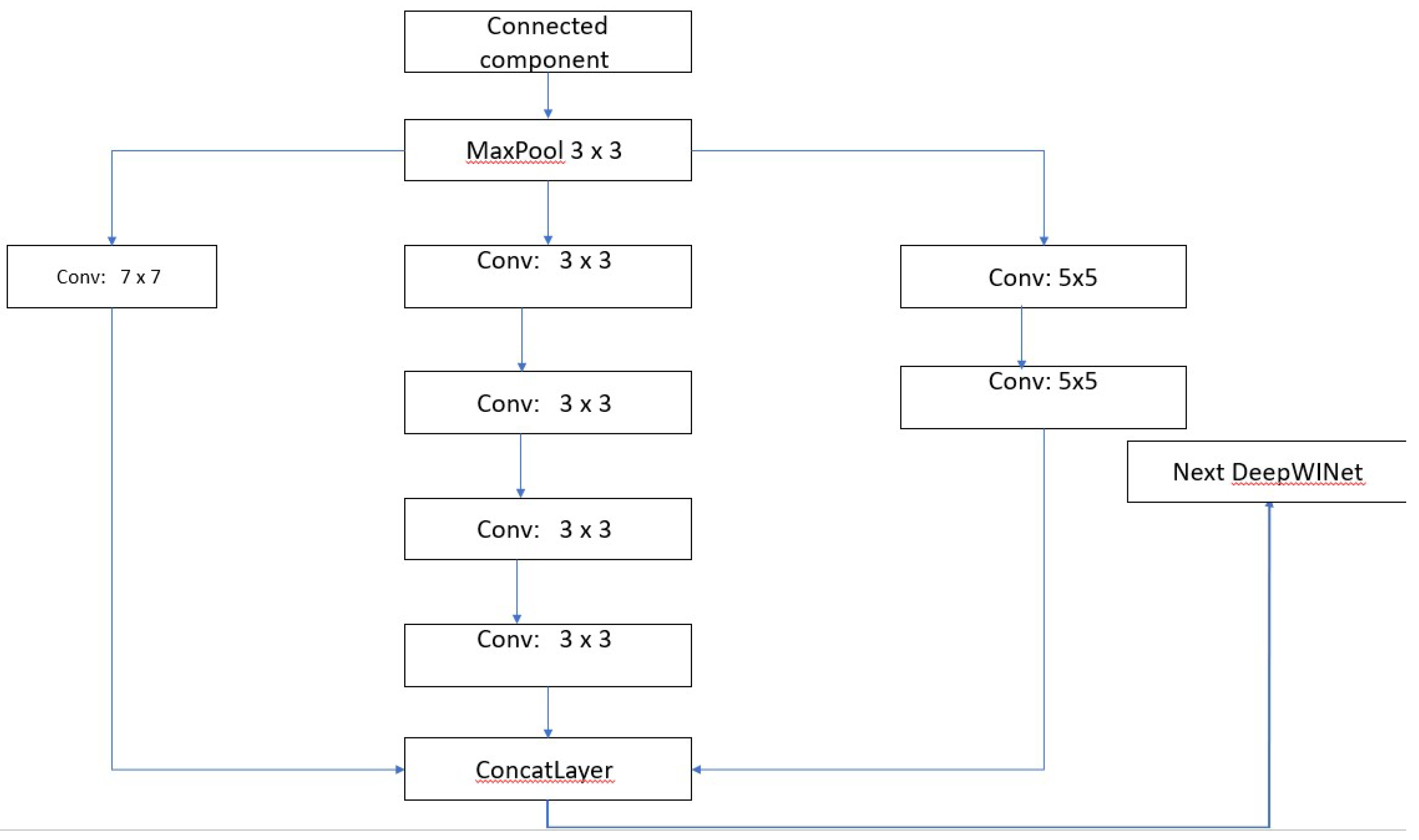

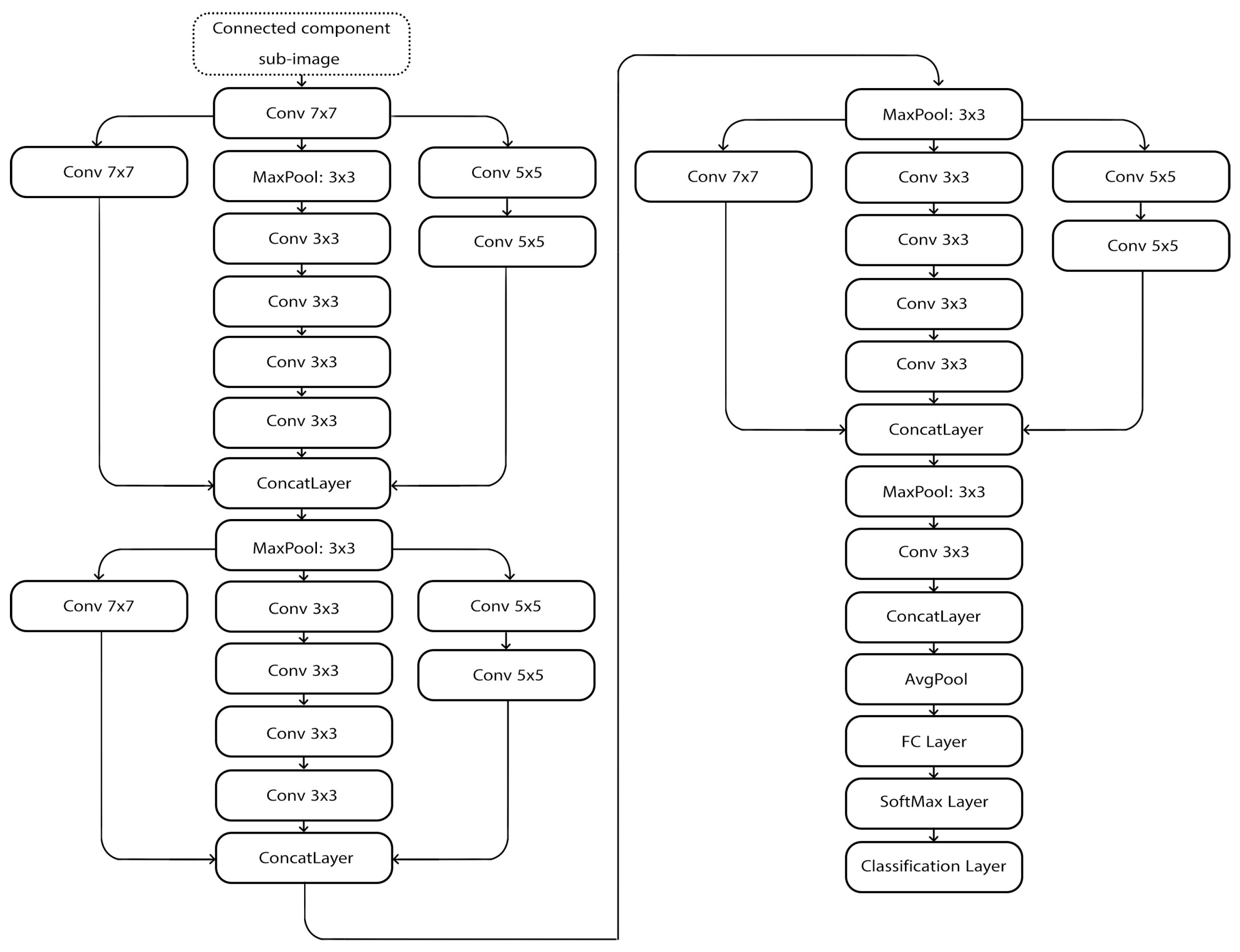

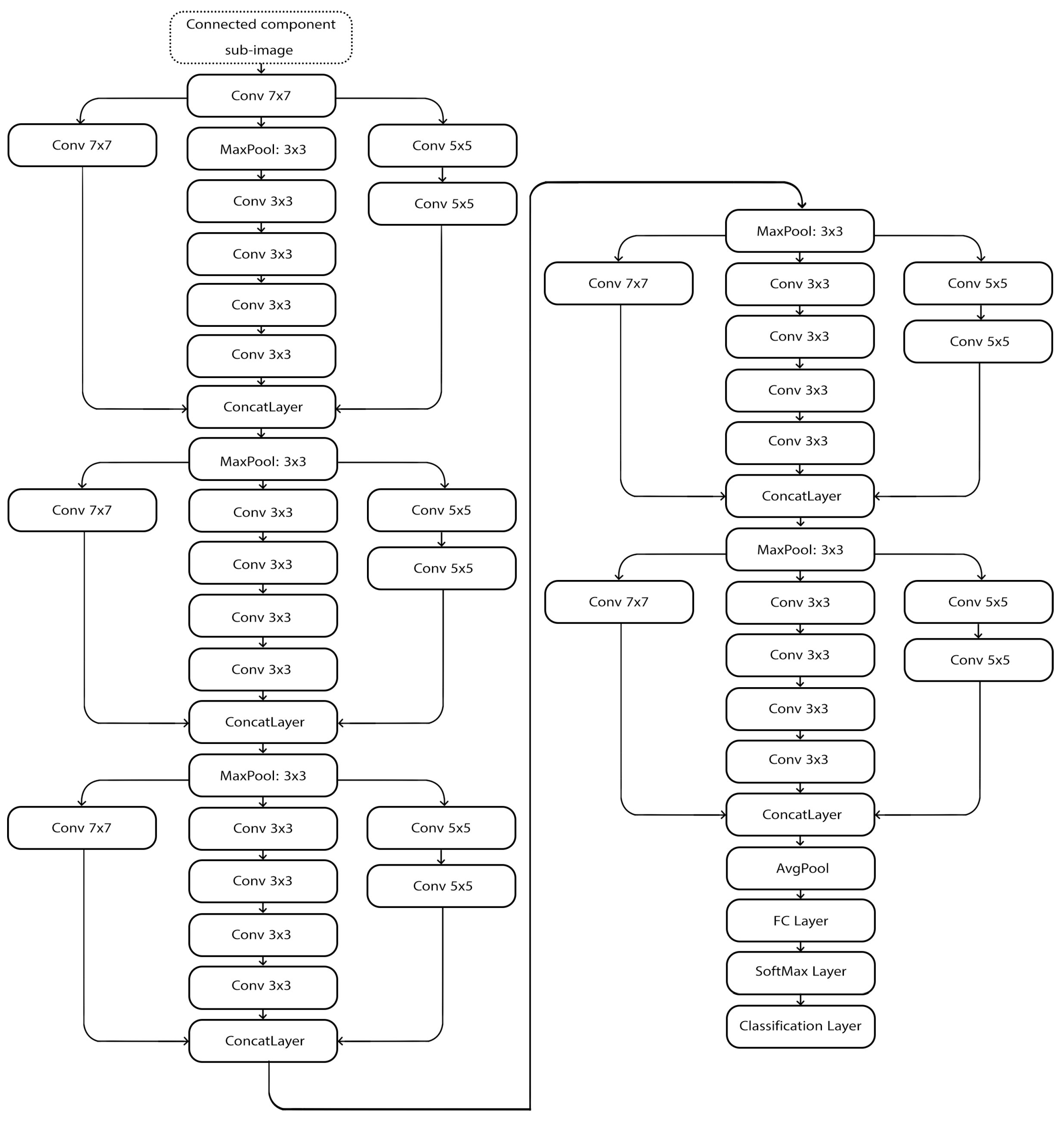

3.DeepWINet is a type of deep convolutional neural network stand for Deep Writer Identification Network. It has two type : Full and Light .

Image segmentation involves extracting sub-images, which are then input into DeepWINet to classify the documents under two distinct scenarios.

Scenario 1: DeepWINet is used to extract features. The deep features are passed to a chi-squared nearest neighbor classifier to identify the author.

Scenario 2: DeepWINet is used as a full end-to-end CNN, and a CC(Connected Components) decision combiner is used to classify the documents. In this approach, the trained DeepWINet predicts all similarity values and, based on these, identifies the author.

In the IAM dataset, under the first scenario, DeepWINet achieves 98.32% for Full version and 98.02% for Light version. In second scenario, DeepWINet achieves achieves 97.41% for Full and 96.95% for Light. In IFN/ENIT dataset, which is for Arabic, in the first scenario, it achieves 99.27% for Full and 99.02% for Light. In the second scenario, it achieves 98.78% for Full and 98.78% for Light. In CVL dataset, which is for English/German, in the first scenario, DeepWINet achieves 100% accuracy for both Full and Light. In the second scenario, DeepWINet achieves 100% for Full and 100% for Light. In Firemaker dataset, whcih is for Dutch, in the first scenario, DeepWINet achieves 98.4% for Full. In the second scenario, it achieves 97.6% for Full. In ICDAR2013 dataset, which is for English/Greek, in the first scenario, DeepWINet achieves 99.8% for Full and 99.2% for Light. In the second scenario, it achieves 99% for Full and 99% for Light. In CERUG-EN dataset, which is for English, in the first scenario, DeepWINet achieves 100% for Full and 100% for Light. In the second scenario, it achieves 100% for Full and 100% for Light. In CERUG-CN dataset, which is for Chinese, in the first scenario, DeepWINet achieves 94.28% for Full and 93.33% for Light. In the second scenario, it achieves 94.28% for Full and 94.28% for Light. In CERUG-MIXED dataset, which is for English/Chinese, in the first scenario, DeepWINet achieves 100% for Full and 100% for Light. In the second scenario, it achieves 100% for Full and 100% for Light.

Figure 3 shows DeepWINet structure.

Figure 4 shows DeepWINet light structure.

Figure 5 shows DeepWINet full structure.

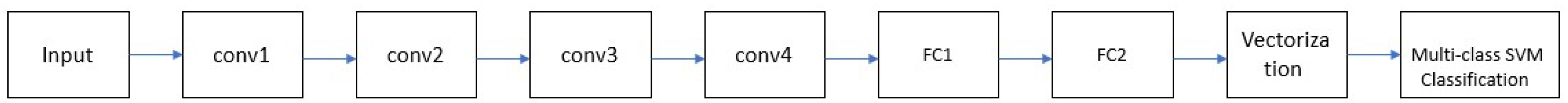

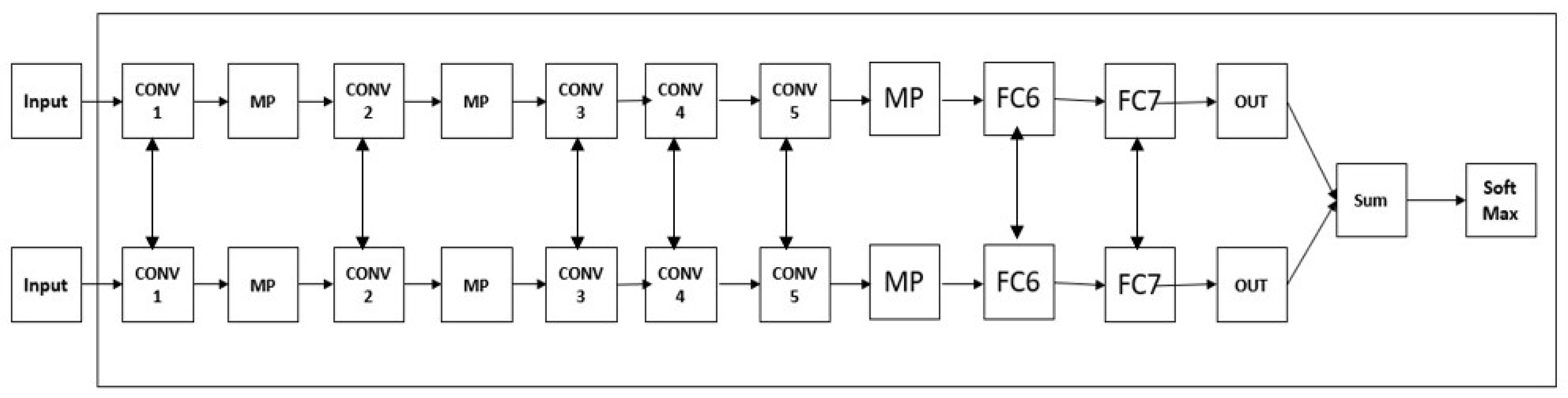

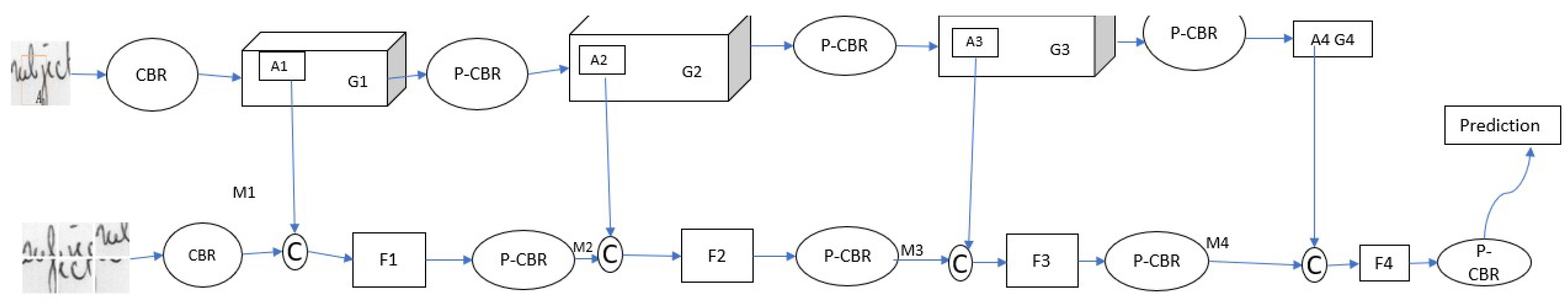

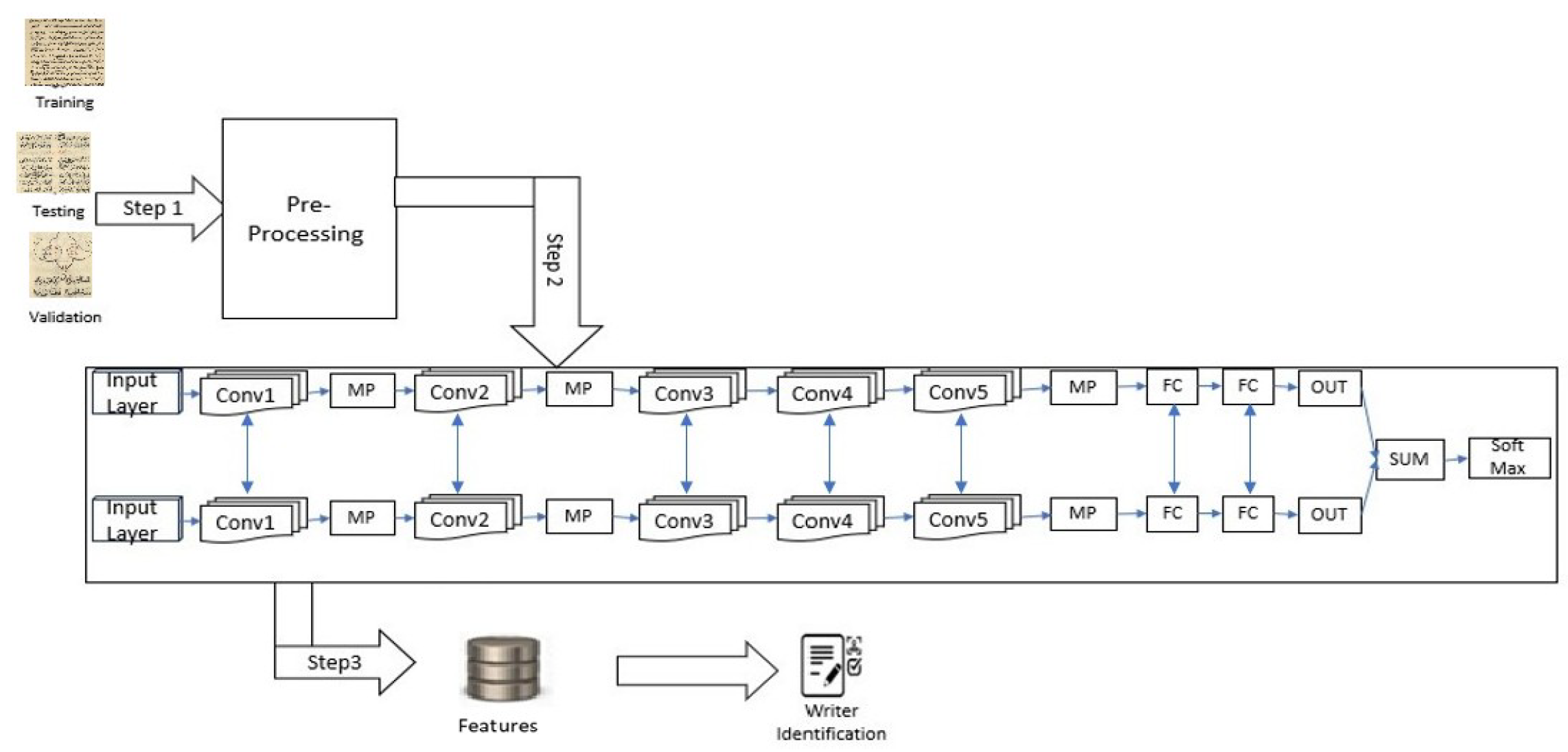

4.DeepWriter is a type of deep multi-stream convolutional neural network, and this model receives local image patches as input and uses SoftMax classification.

Figure 6 shows the Deep Writer structure.

The boxes with ConvX denote convolutional layers, which are responsible for extracting features.

The boxes with MP denote Max-Pooling layers, which can be used to reduce the spatial dimensions of the features.

The boxes with FCX denote fully connected layers, which are used to learn non-linear combinations of the high-level features extracted by the convolutional layers.

The Softmax denotes the soft-max classifier used to transform the output into a probability distribution over the target classes [

7].

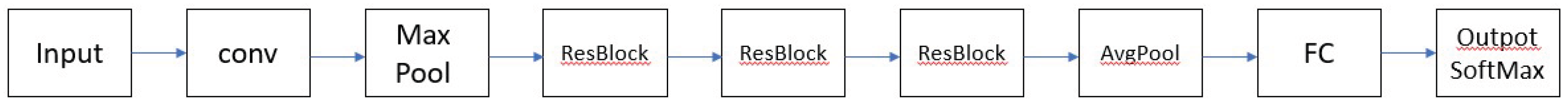

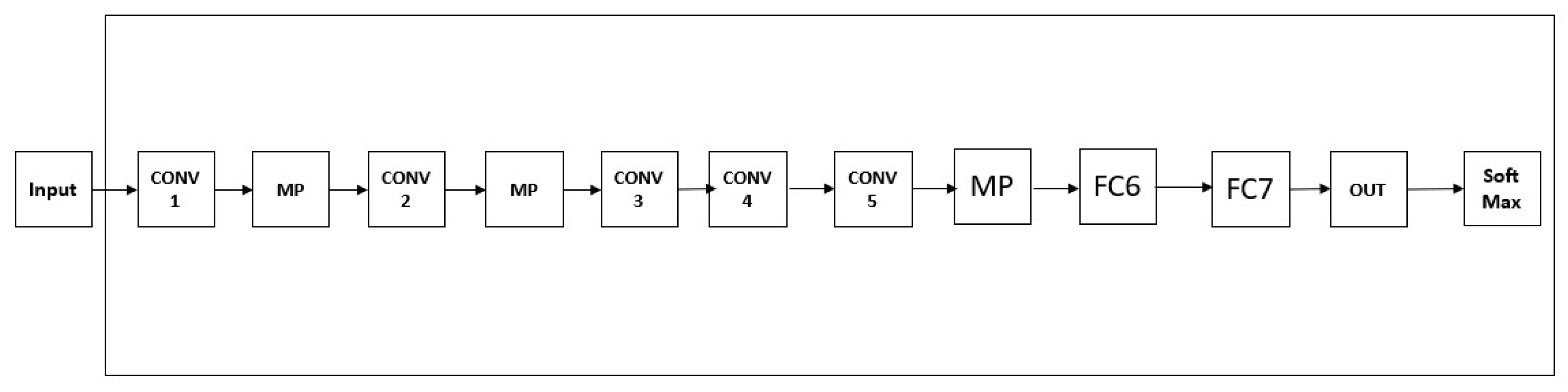

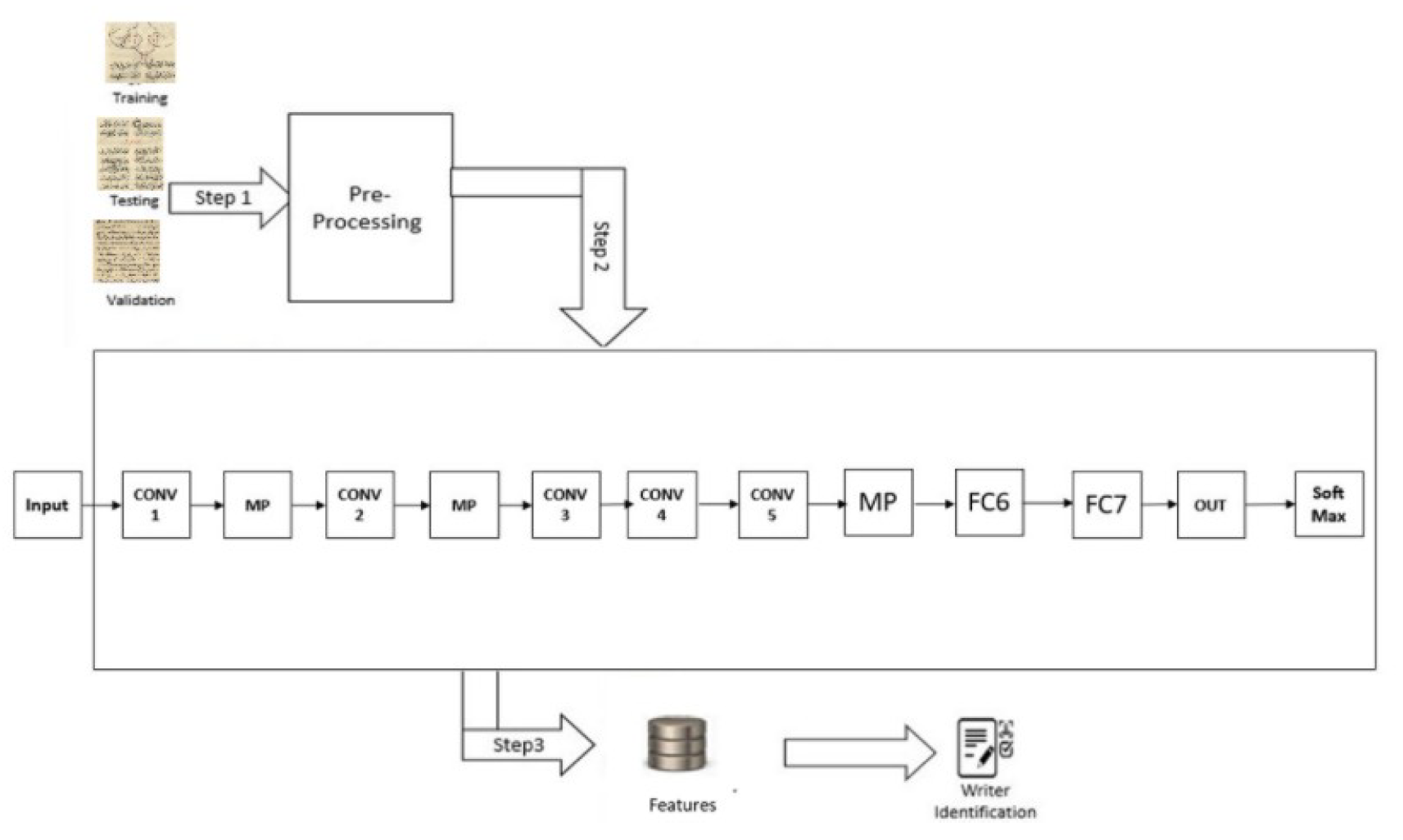

5.Half Deep Writer is a type of deep CNN, it’s different from Deep Writer it’s not multi-stream, one stream.

Figure 7 shows the Half Deep Writer structure.

Linjie, Qiao [

7] employs Deep Writer and Half Deep Writer for feature extraction. This DeepWriter takes handwritten patches from the English IAM and Chinese HWDB datasets as input and is subsequently trained and classified using Softmax classification. The accuracy of Deep Writer in IAM is 99.01%, the accuracy of Half Deep Writer in IAM is 98.23% while the accuracy of Half Deep Writer in HWDB is 93.85%.

6. FragNet is a deep neural network designed for writer identification based on small text samples, such as word or text block images. It is a dual-pathway architecture.

Figure 8 shows the FragNet structure.

Sheng He, Lambert Schomarker [

6] Sheng He, Lambert Schomarker [13] Employ FragNet for feature extraction. This model is applied to four datasets: IAM, CVL, CERUG-EN, and Firemaker. The accuracy of IAM is 96.3%, CVL is 99.1%, CERUG-EN is 100.0%, and FIREMAKER is 97.6%. FragNet’s limitation derives from its dependence on word image or region segmentation, which causes significant challenges for manuscripts featuring extensive cursive writing.

In [

15] The methodology relies on segmenting the text into patches using a sliding window and feeding it to pre-trained models such as ResNet, VGG, and DenseNet to extract multiple features from each passage. After extraction, the features are combined using multidimensional feature fusion techniques. The Euclidean distance is then calculated to determine similarity. It was observed that combining features extracted from multiple different models improved the system’s performance compared to using only one model. The results confirmed that metric techniques such as Euclidean distance were effective in distinguishing between writers at the passage level and then at the entire document level. The method was applied to a Chinese dataset. The method achieved a high accuracy rate of over 90% in the best-case scenario, demonstrating the feasibility of using feature fusion with pre-trained models.

In [

16] aims to identify authors based on analyzing the linguistic and writing style of texts, rather than relying on direct textual content. This method uses traditional machine learning using the Support Vector Machine (SVM) algorithm. A set of text-derived features was developed in this paper , such as:Word frequency, Lexical richness ,Sentence length ,POS tagging and Sequence patterns Data was collected from Google Scholar, and in the end, 400 papers were selected. The model was tested on three subsets (A, B, and C) to ensure balance and diversity in style. The model achieved high classification accuracy, in some cases exceeding 90%, especially when the model was trained on balanced data, where the number of writers and the number of papers per writers were balanced.

Zhao, Cao and Zhang[

17] present a new model called CompNET, which aims to improve classification accuracy without the need for large and pretrained datasets. The basic idea is to combine the top-k results from multiple models and then analyze the intersections between these models. Since the top-k results often contain the correct class, CompNET intersects the different outputs to isolate the correct class, even if it is not the Top-1. Combining CompNET with existing models improved classifica- tion accuracy comparing with individual methods, such as ResNet or EfficientNet. For example, the top-1 accuracy without CompNET was 88.3%; with CompNET, it raise to 94.1%.

The related works cited in this paper were selected based on their relevance to writer identification. Preference was given to recent and widely cited studies. This paper was included to show all Arabic historical studies in writer identification field. Following

Table 2 and

Table 3 shows the summary of arabic and other labguage studies.

Our inspiration comes from the research and projects discussed, leading us to leverage the WAHD dataset. This dataset stands out for its vast collection of historical documents spanning various time periods and locations.

3. Research Methodology

Choosing of DeepWriter and Half DeepWriter was motivated by their architecture’s proven effectiveness in writer identification tasks across various languages demonstrated the best performance on the IAM dataset. First, Deep Writer, a unique model set apart from traditional Deep CNNs by two distinct paths, each comprising multiple layers. These paths converge into a single unified path, culminating in a dependable and accurate outcome. Second , Half-deep writer It has a design of half structure of deep writer with a single path.

In contrast, while models like ResNet and Inception are powerful general-purpose CNNs, they are not specifically designed for author identification. For example, ResNet20 was used to extract features from specialized datasets like Balamand, not for end-to-end author classification. Our approach integrates classification directly into the pipeline, specifically for this task.

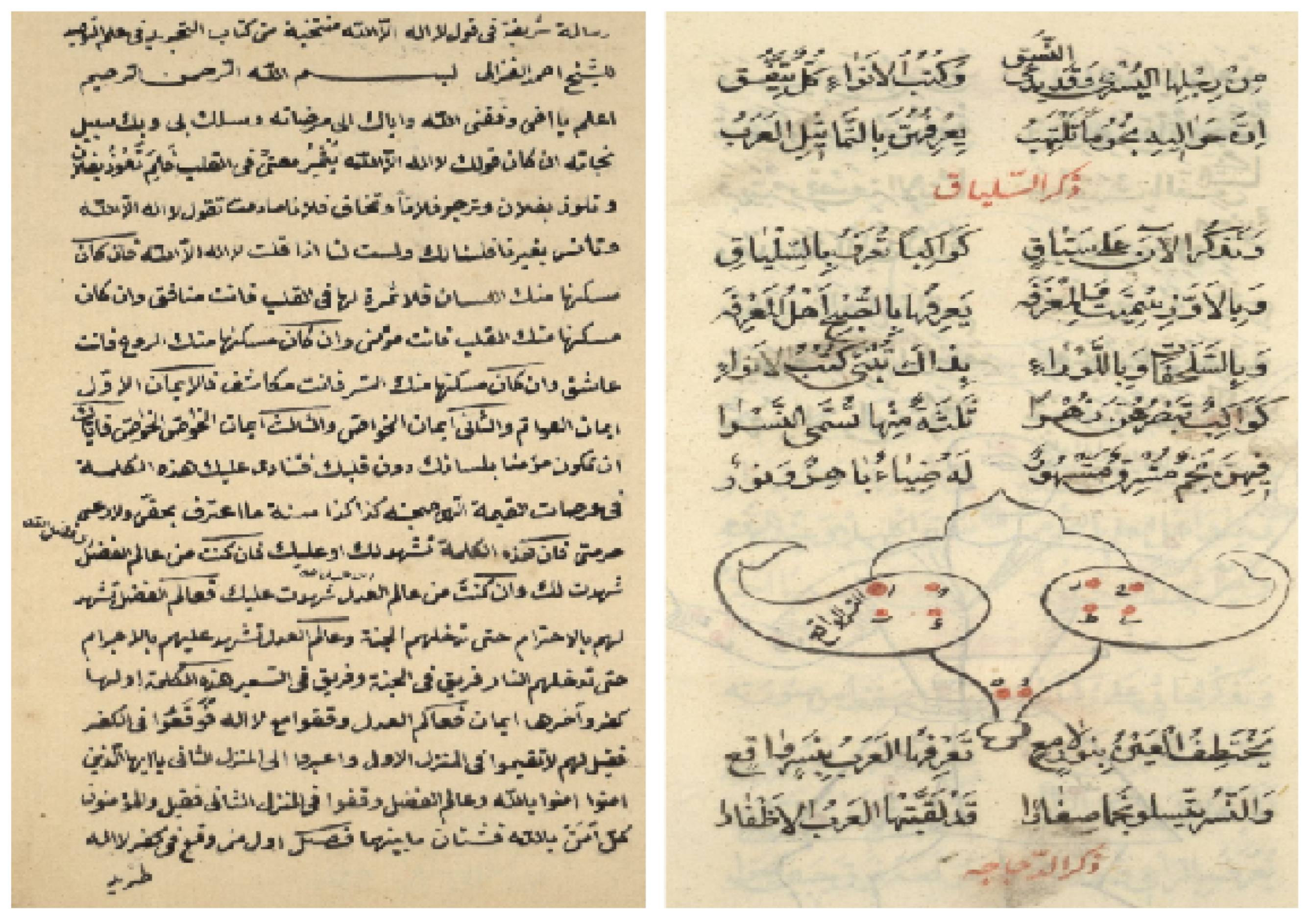

3.1. Datasets

WAHD stands for Writer’s Identification of Arabic Historical Document[

5]. This data set can be used for the writer’s identification of Arabic historical documents. This contains historical Arabic manuscripts produced by multiple known and unknown writers, which include a range of time periods. Manuscripts have been gathered from the National Library in Jerusalem (NLJ) and the Islamic Heritage Project (IHP). The dataset includes 353 manuscripts from 322 different writers, comprising a total of 43,976 pages. Specifically, the IHP contributes manuscripts from 302 writers, amounting to 36,969 pages, with 23 of those writers being known. Meanwhile, the NLJ contributes manuscripts from 20 authors, containing 7,007 pages.

Eleven writers who authored multiple manuscripts (S-Multi) contribute 2,313 pages. Twelve writers who wrote only one manuscript (S-Single) account for 2,108 pages. Two hundred seventy-nine manuscripts by unknown authors (S-Unknown) comprise 32,548 pages. Two hundred one manuscripts are of unknown provenance. The books cover six subjects: religion, mathematics, physics, agriculture, literature, and science.

The manuscripts were written between the 15th and 20th centuries. The manuscripts in the database come from 13 different countries, including: Egypt (8 manuscripts), Syria (34 manuscripts), Turkey (18 manuscripts), India (55 manuscripts), Morocco (5 manuscripts), Other countries: China, Iran, Pakistan, Lebanon, Uzbekistan, Greece, and Serbia. [

2].

In chammas, Makhoul, Demerjian, Dannaoui [

3] put a percentage of known writers at 60% and unknown writers at 40% to create a balance between them. Number of all images in all data is 11,619. Here, we do the same. We take 60% known writers, equivalent to 54 manuscripts of known writers, and 40%, equivalent to 34 manuscripts of unknown writers.

The number of data in the WAHD database is unbalanced, so we apply data augmentation to improve the balance between classes to solve the problem of overfitting and improve the generalization of the model.

The data was split into 70% training and 30% (test + validation). This 30% of the total data was then divided into 20% of the total data for the validation set and 10% of the total data for the test set. We address the problem of rare classes in training using data augmentation, then upload additional data to test unknown categories. In the end, data is splitting to training size: 11,543 images , validation size: 3,315 images, test size: 1,633 images. Training size after augmentation: 27,838 images Test size after adding new classes: 2,189 images.

Figure 9 shows an example of WAHD:

3.2. Methodology

In this section, we discuss the whole experiment.

Here, a number of improvements and changes enhanced the model’s efficiency.

Resizing Images: Each image resized to 128x128 pixels.

Binary Thresholding: Pixels meeting the condition are set to 255 (white) and others to 0 (black). This step helps in reducing the complexity.

Label Encoding: Each image label is encoded in a numerical format and is obtained from the folder names.

Split data using StratifiedShuffleSplit to maintain the appropriate distribution of the different categories in the sets and reducing bias.

-

Data augmentation is applied only to the training set: New images are generated using techniques such as

- –

Crop (Cut a small portion of the image).

- –

Multiply (Slightly change the contrast).

- –

Affine (Rotate the image between -10 and +10 degrees).

HeNormal Initialization with convolutional layers: helps resolve the ReLU activation functions issue.

L1 and L2 regularization in the fully connected layer: Punishing huge weights to increase the model’s generalization capacity. The alues are L1=0.0001, L2=0.0001

Early Stopping: Automatically ends training after a specified amount of epochs, if the detected metric does not improve.

Reduce Learning Rate: When the monitored measure does not improve for a predetermined amount of epochs, the learning rate is automatically decreased.

Model checkpoint: This tool saves the model when the validation data performance improves. This guarantees that even if training goes on long after optimal performance is reached, you can still get the best version of the model.

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 shows the Pipelines of this Paper.

In this paper, we apply two models Deep Writer and Half Deep Writer on a subset of the WAHD dataset. Here, images are converted to black and white using Binarization, classes are converted to numbers using LabelEncoder, and data is split using StratifiedShuffleSplit to ensure class balance. Augmentation is performed for rare classes in training only. After applying the models, validation and testing are computed. New classes are loaded for testing to ensure they do not overlap with the original classes, and testing is calculated after merging with the new classes. F1-score, recall, and precision are computed for all models.

4. Result

As a result, selecting evaluation metrics appropriate for the models, including precision, recall, and the F1-Score. To measure the effectiveness of our model, we calculate these metrics as follows:

1. Precision: It estimates the accuracy of the model’s positive predictions.

2. The Recall measures the model’s ability to find all the positive instances. It is calculated as:

True Positives (TP) are the number of correct positive predictions.

False Positives (FP) are the number of incorrect positive predictions.

False Negatives (FN) are the number of positive instances that were incorrectly predicted as negative.

3. The F1-Score is the harmonic average of Precision and Recall. It is calculated as:

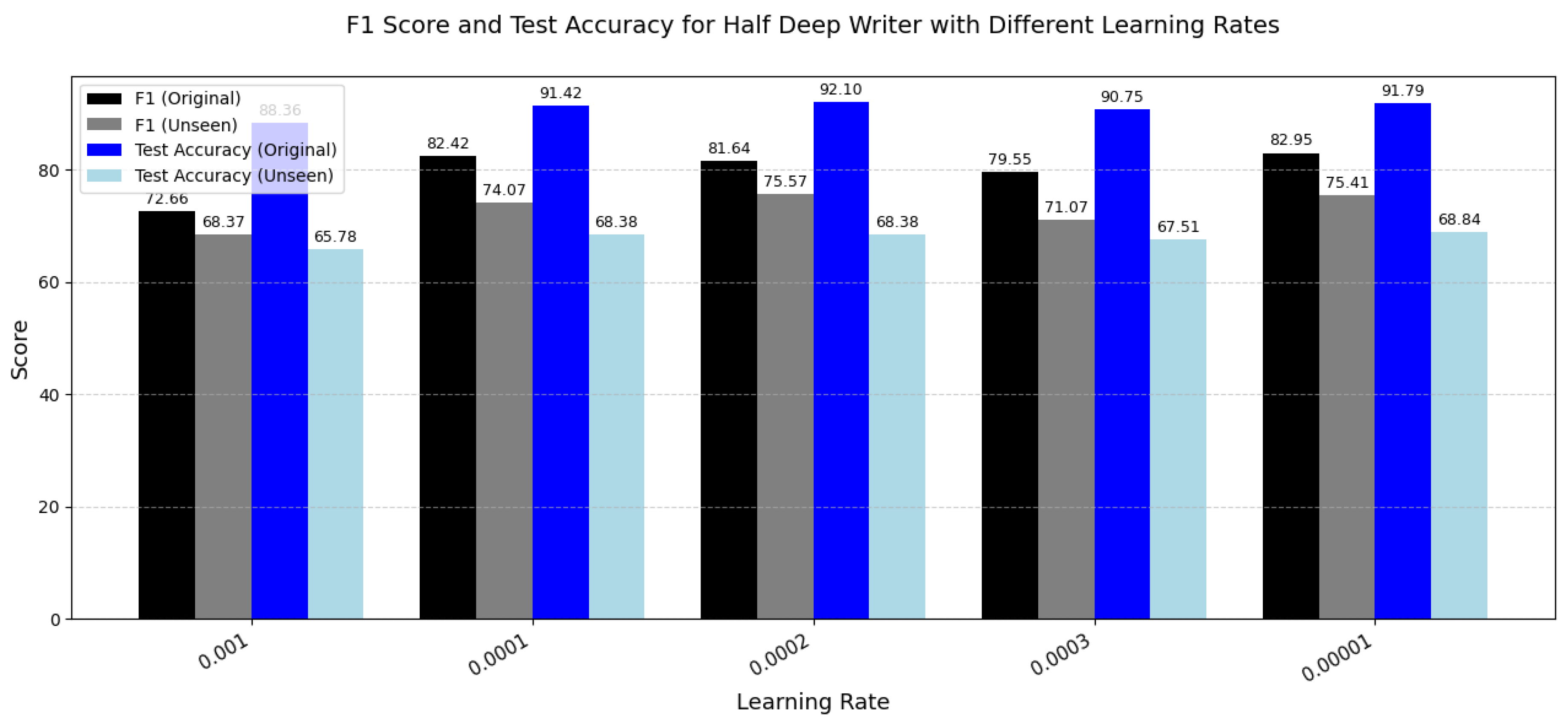

4.1. Half Deep Writer Result

Table 4 presents the training and validation results of the Half DeepWriter model under different learning rates. The results indicate that the learning rate has a significant impact on model performance.

Learning Rate 0.0001: When using learning rate of 0.0001, training and validation accuracy improved to 96.73 and 93.03% respectively, with a decrease in loss of 0.4015 and 0.6667, indicating improved overall model performance.

Learning Rate 0.0002: When increasing the learning rate to 0.0002, training and validation accuracy increased slightly to 96.99 and 93.12% with a continued decrease in loss 0.3335 and 0.5987, indicating that it may be one of the best values chosen to achieve a balance between accuracy and loss.

4.1.1. Half Deep Writer Test Result

Table 5 presents the the test accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score results of the Half DeepWriter model under different learning rates.

Learning Rate 0.0001: At this rate, the test accuracy was 91.42%, and the test loss was 0.7188, The precision reached 84.74% and recall was 83.22%, giving an F1-score of 82.42%, indicating improved generalization and the model’s ability to learn better.

Learning Rate 0.0002: At this rate, the test accuracy was 92.10%. This represents the high performance, and the test loss dropped to 0.674, making it one of the best values chosen for this model. Precision and recall were 85.60% and 81.47%, respectively, resulting in the highest F1-score of 81.635%, reflecting the model’s ability to classify data with high accuracy.

4.1.2. Half Deep Writer Result with Adding Unseen Data to Test Set

Table 6 presents the Test accuracy after adding new data to test set that model was not trained on, along with precision, recall, F-1 score results under different learning rates.

Learning Rate 0.0001: This achieved a higher accuracy of 68.38%, with a lower test loss of 5.30. Precision and recall were 75.16% and 80.64%, resulting in an improved F1-score of 74.07%. These results suggest that this learning rate is not suitable under the increased complexity of the test data, likely due to poor generalization and convergence instability.

Learning Rate 0.00002: At his learning rate, it achieved a test accuracy of 68.84% with a slightly higher loss of 5.74, but it achieved the highest precision 79.14% and strong recall of 80.32% respectively, resulting in F1-score of 75.57%. This indicates acceptable performance but may suffer from some instability due to the difficulty of achieving faster optimizations.

4.2. Deepwriter Result

Table 7 presents the performance of the DeepWriter model with different learning rates, focusing on the training and validation phases, using accuracy and loss metrics to assess generalization and model stability.

Learning Rate 0.0001: For this rate, the training accuracy increased to 98.34% and validation accuracy reached to 93.15%, which was higher than achieved at a learning rate of 0.001. The training and validation losses were 0.2216 and 0.6570, meaning the model learned more stably.

Learning Rate 0.0002: At this learning rate, it achieved a maximum learning efficiency, with a training accuracy 98.18%, validation accuracy of 93.21%, training loss of 0.1857, and validation loss 0.6071, making this the most suitable learning rate for the DeepWriter model.

This learning rate produced the lowest training accuracy of 87.65% and the highest losses of 1.7201 in train and 1.8310 in validation. Although the validation accuracy was 88.96%, this indicates that the model did not learn sufficiently due to the low rate and was therefore unable to effectively reduce the loss.

4.2.1. Deep Writer Test Result

Table 8 presents the Test accuracy, precision, recall and F-1 score results of the DeepWriter model under different learning rates.

Learning Rate 0.0001: At this rate, test accuracy of 91.91% and test loss of 0.7295 was achieved. Precision was 84.26% and recall was 82.556%, leading to an F1-score of 82.33%. This has the highest recall rate, indicating that the model was able to identify the majority of correct cases and this rate produced very strong results in terms of the balance between class recall and accurate classification.

Learning Rate 0.0002: This rate showed a highest test accuracy of 92.28% and lowest test loss of 0.7065. Precision was 85.50%, and recall reached 80.10%. These values reflect strong generalization and a balanced ability to correctly identify positive samples, making this the optimal learning rate for the model.

4.2.2. Deep Writer Result with Adding Unseen Data to Test Set

Table 9 presents the Test accuracy after adding new data to test set that the model was not trained on, along with precision, recall and F1 score results under different learning rates.

Learning rate 0.0001: This rate produced a test accuracy of 68.93% with a high test loss of 6.526. Precision was 78.523%, and recall 80.66%, resulting in the highest F1-score of 75.46%. Despite the high loss, these results indicate that the model performs well in terms of detecting relevant samples and achieving strong class balance.

Learning Rate 0.0002: This rate achieved a test accuracy of 68.38% and a test loss of 5.664. Precision was 77.40% and recall was 79.42%, with an F1-score of 74.74%. These values reflect strong and stable performance, making this learning rate a balanced choice between accuracy and consistency.

To optimize model performance, a structured hyperparameter tuning strategy was implemented. The Adam optimizer (Adaptive Moment Estimation) was used, as it adaptively adjusts the learning rate for each parameter. Multiple learning rates were tested: 0.001, 0.0003, 0.0002, 0.0001, and 0.00001. Among these, 0.0002 and 0.0001 performed best, offering a good balance between training stability and generalization. A learning rate scheduler (ReduceLROnPlateau) was also employed, which reduces the learning rate when validation loss fails to improve, helping to stabilize training. Additionally, early stopping was used to halt training when performance plateaued, reducing the risk of overfitting. The model checkpointing strategy ensured that the best-performing model based on validation accuracy was saved [

14].

Figure 12.

Comparison of F1 Score and Test Accuracy for the Deep Writer model using different learning rates. This chart illustrates performance on original and unseen datasets.

Figure 12.

Comparison of F1 Score and Test Accuracy for the Deep Writer model using different learning rates. This chart illustrates performance on original and unseen datasets.

Figure 13.

Comparison of F1 Score and Test Accuracy for the Half Deep Writer model using different learning rates. This chart illustrates performance on original and unseen datasets.

Figure 13.

Comparison of F1 Score and Test Accuracy for the Half Deep Writer model using different learning rates. This chart illustrates performance on original and unseen datasets.

4.3. The Impact of Learning Rate (LR) on Model Performance

Choosing the learning rate is a key factor contributing to the performance of large-scale learning models. This study found that values of 0.0002 and 0.0001 were the most efficient for both the DeepWriter and Half DeepWriter models. This is because these values provide a good balance between the convergence speed and model stability during training. In contrast, values as low as 0.001 are difficult to achieve. Very low values, such as 0.00001, were weak points in learning, causing the model to stall at a local minimum without improving performance. Thus, the results confirms that choosing the appropriate learning rate is an important part of improving the model and reducing error.

Previous work on similar tasks often used fixed learning rates without much experimentation. In contrast, this study systematically varied learning rates to identify an optimal range, emphasizing the importance of LR tuning for improved performance. The deep Convolutional Neural Network architecture used in this study required LR tuning due to its depth and complexity, which benefit significantly from careful adjustment to ensure stable and efficient convergence during training. Instead of using automated tools like grid search or LR finder, multiple learning rates were tested manually, and their performance was evaluated to determine the most effective one. It was also observed that selecting an appropriate learning rate not only improved accuracy but also reduced training time by enabling faster convergence and avoiding unnecessary epochs.

While previous research has primarily focused on author identification using manuscripts in other languages, there has been comparatively less emphasis on Arabic manuscripts. Many studies analyzing Arabic texts have used unpublished databases, limiting the generalizability of the results. This research, on the other hand, used a published online database covering several historical periods and geographical regions. Previous studies have primarily used old and generic algorithms. Recent studies have begun using neural networks, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs). However, they often rely on simple and unfamiliar structures. Our research, on the other hand, used two complex models: Deep Writer and Semi-Deep Writer, which utilize a Deep Neural Network architecture. Additionally, we tested different learning rates to achieve optimal performance. The results of previous studies are either less accurate, limited to unpublished databases, or even lack generalizability. Here, we tested the two models on a portion of the dataset the model had not been trained on before, increasing generalizability.

5. Comparing with Similar Studies

Table 10,

Table 11 helps us to to know the effectiveness and generalizability of DeepWriter and Half DeepWriter by comparing them against existing datasets. Although the recall is high, the precision and F1-score are very low, indicating many false positives. This highlights the poor model precision in other approaches. Dataset results for KHATT can be seen in the following

Table 10:

Table 11 (Balamand dataset) reports high accuracy but significantly low recall and F1-score, suggesting that the model performs well on a small set of frequent classes while failing to generalize across less-represented writers.

Table 12 clearly shows that DeepWriter and Half DeepWriter outperform previous models in terms of balanced precision, recall, and F1-score, especially when evaluated with new unseen writers.

This demonstrates that the proposed models are not only accurate, but also generalize better across diverse datasets and offer a better balance between identifying the correct samples (precision) and finding all relevant samples (recall). These models maintain high F1 scores, indicating robustness across all classes, and maintain consistent performance even when used with new, uninformed writers, a key factor in their real-world applicability.

The KHATT dataset results suffer from significantly low precision and F1-score, despite high recall, indicating problems with the balance between true and false positives.

The Balamand dataset showed very high accuracy, but a low F1-score, especially on the test set, indicating that the model recognizes a small number of writers but with high accuracy.

The DeepWriter and Half DeepWriter models demonstrated more balanced results in terms of precision and F1 score compared to the other models. This means that these models not only recognized a large number of writers, but were also more accurate at distinguishing between different writers, resulting in fewer prediction errors.

Using a stratified split to maintain class distribution, and data augmentation (cropping, affine rotation, contrast adjustment), helped to mitigate class imbalance and overfitting. DeepWriter uses a multi-stream CNN structure, which allows it to capture more complex features from different patches of handwriting. Half DeepWriter simplifies this architecture while still preserving performance. Using L1 and L2 regularization (both at 0.0001) helps prevent overfitting by penalizing large weights. HeNormal initialization is particularly effective with ReLU activations, leading to faster convergence. The model was tested on entirely new writers, demonstrating generalization beyond seen classes.

We observed that using a small learning rate of 0.0002 and 0.0001 significantly improved performance, as it helped the models learn gradually and steadily, reducing the likelihood of fluctuations in results or missing some classes during training.

Overall, it can be said that DeepWriter and Half DeepWriter provided more stable and balanced performance.

6. Conclusion

This paper presented the Deep Writer model and Half Deep Writer to address the writer’s identification of Arabic historical documents. Deep Writer is a type of deep multi-stream Convolutional Neural Network. Half Deep Writer is similar to DeepWriter but it differs in that it’s single-stream rather than multi-stream. This models uses advanced techniques such as convolutional layers and regularization methods such as L1 AND L2 regularization to increase accuracy and reduce overfitting. By using subset of the WAHD dataset, consisting of 54 manuscripts for known writers (equivalent to 60%), and 34 manuscripts from unknown writers (equivalent to 40%) the model was evaluated accordingly. Number of all images in this subsets data is 16491. The two models were then tested by adding a new data to the test set. We analyzed how the learning rate affected the model’s performance. Our study showed that learning rate is a critical factor in enhancing the model’s overall efficiency and accuracy. This learning rate enables the model to achieve high accuracy while avoiding overfitting issues. The results of this study offer an improved understanding of how the learning rate directly impacts the effectiveness and quality of models in deep learning applications. It also highlights the need to find the optimal learning rate . This study improves historical understanding and archiving by identifying the document’s author. It enhances academic cooperation and cultural interaction by improving the accessibility and understanding of historical Arabic documents for various research communities.

For future work, DeepWriter and Half DeepWriter can be applied to arabic hand written data sets such as KHATT and IFN/ENIT as well as English datasets .

In the future, we will use CompNET with DeepWriter and Half DeepWriter. The integration aims to leverage the advantages of CNN architectures, in addition to CompNET’s ensemble-based decision refinement. We expect that applying CompNET to the outputs of DeepWriter models will improve top-1 and top-k accuracy, particularly in challenging cases involving visually similar handwriting or limited training data.

Author Contributions

The author conducted the entire research and the supervisors participated through academic guidance.

Funding

There is no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the supervisors for their support and guidance.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing |

| VLAD |

Vector of Locally Aggregated Descriptors. |

| PCA |

Principal Component Analysis |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| WAHD |

Writer’s Identification of Arabic Historical Documents |

| CBF |

Contour-Based Feature |

| M-CBF |

Modified Contour-Based Feature |

| OBI |

Oriented Basic Image |

| SIFT |

Scale-Invariant Feature Transform |

| G-SIFT |

GPU-based Scale-Invariant Feature Transform |

| G-SURF |

GPU-based Speeded-Up Robust Features |

| HR-SIFT |

High-Resolution Scale-Invariant Feature Transform |

| HE-SIFT |

Histogram Equalized Scale-Invariant Feature Transform |

| SVM |

Support Vector Machine |

| NN |

Nearest Neighbor |

| VLAD |

Vector of Locally Aggregated Descriptors |

| ReLU |

Rectified Linear Unit |

| L1/L2 Regularization |

Regularization to prevent overfitting |

| MP |

Max Pooling |

| FC |

Fully Connected Layer |

| Softmax |

Softmax Classification Function |

| Adam Optimizer |

Adaptive Moment Estimation Optimizer |

| StratifiedShuffleSplit |

Data split method preserving class distribution |

| S1 |

Scenario 1 |

| S2 |

Scenario 2 |

| ResNet |

Residual Network |

| VGG |

Visual Geometry Group Network |

| DenseNet |

Densely Connected Convolutional Network |

| SVM |

Support Vector Machine |

| POS |

Part of Speech |

| CompNET |

Complementary Neural Network |

| Top-k |

Top-k Ranking Results |

References

- Ibn Khedher, M.; Jmila, H.; El-Yacoubi, M.A. Automatic processing of Historical Arabic Documents: A comprehensive Survey. Pattern Recognition 2020, 100, 107144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhaleem, A.; Droby, A.; Asi, A.; Kassis, M.; Al Asam, R.; El-sanaa, J. WAHD: A database for writer identification of Arabic historical documents. In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Arabic Script Analysis and Recognition (ASAR); 2017; pp. 64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Chammas, M.; Makhoul, A.; Demerjian, J.; Dannaoui, E. A Deep Learning based System for Writer Identification in Handwritten Arabic Historical Manuscripts. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durou, A.M.; Aref, I.A.; Erateb, S.; El-Mihoub, T.A.; Ghalut, T.; Emhemmed, A.S. Offline Writer Identification using Deep Convolution Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Maghreb Meeting of the Conference on Sciences and Techniques of Automatic Control and Computer Engineering (MI-STA); 2022; pp. 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Asi, A.; Abdalhaleem, A.; Fecker, D.; Märgner, V.; El-Sana, J. On writer identification for Arabic historical manuscripts. International Journal on Document Analysis and Recognition 2017, 20, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Schomaker, L. FragNet: Writer Identification Using Deep Fragment Networks. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2020, 15, 3013–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohi, Q. DeepWriter: A deep learning-based writer identification system. 2021. Available online: https://github.com/QuwsarOhi/DeepWriter (accessed on February 2025).

- Chahi, A.; El-merabet, Y.; Ruichek, Y.; Touahni, R. An effective DeepWINet CNN model for off-line text-independent writer identification. Pattern Analysis and Applications 2023, 26, 1539–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedher, M.I.; Jmila, H.; El-Yacoubi, M.A. Automatic processing of Historical Arabic Documents: a comprehensive survey. Pattern Recognition 2020, 100, 107144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, S.A.; Ahmad, I.; Alshayeb, M.; Al-Khatib, W.G.; Parvez, M.T.; Fink, G.A.; Märgner, V.; El Abed, H. Khatt: Arabic offline handwritten text database. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Frontiers in Handwriting Recognition; 2012; pp. 449–454. [Google Scholar]

- Awaida, S.M. Text independent writer identification of Arabic manuscripts and the effects of writers increase. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Vision and Image Analysis Applications; 2015; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Awaida, S.M.; Mahmoud, S.A. Writer identification of Arabic text using statistical and structural features. Cybernetics and Systems 2013, 44, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asi, A.; Abdalhaleem, A.; Fecker, D.; Märgner, V.; El-Sana, J. On writer identification for Arabic historical manuscripts. International Journal on Document Analysis and Recognition (IJDAR) 2017, 20, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayyat, M.M.; Elrefaei, L.A. Towards author recognition of ancient Arabic manuscripts using deep learning: A transfer learning approach. International Journal of Computing and Digital Systems 2020, 90, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y. Text Independent Writer Identification Based on Pre-training Model and Feature Fusion. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2022, 2363, 012015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Asad, M.; Asif, H.; Ali, A.; Jamil, M.A. Author Identification Using Machine Learning. Journal of Computing & Biomedical Informatics 2024. Used SVM on 400 papers; Subsets A, B, C.

- Zhao, B.; Cao, X.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Miao, Q.; Li, Y. CompNET: Boosting Image Recognition and Writer Identification via Complementary Neural Network Post-processing. Pattern Recognition 2025, 157, 110880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).