Submitted:

18 June 2025

Posted:

18 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

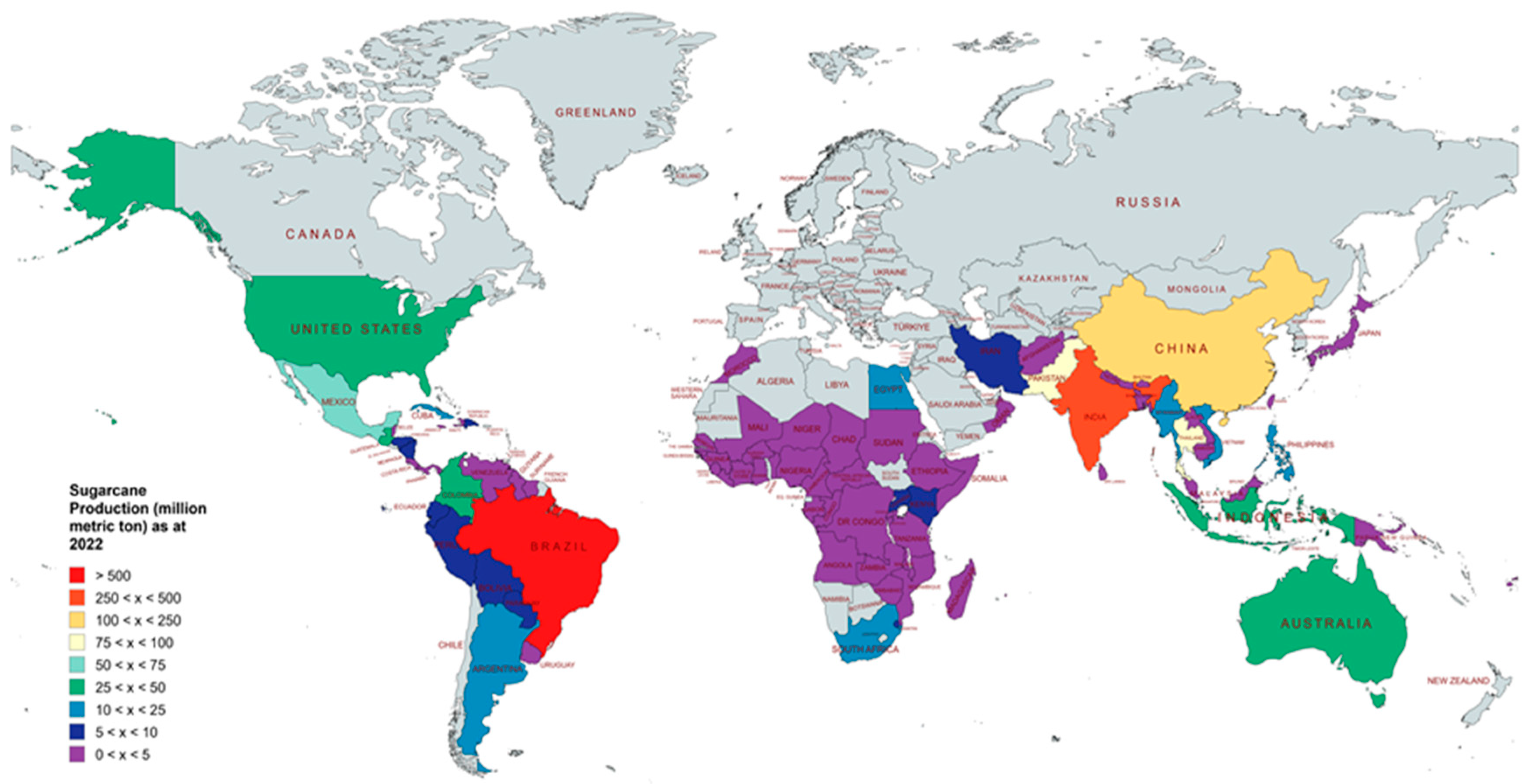

2. Overview of Global Sugarcane Cultivation and Production

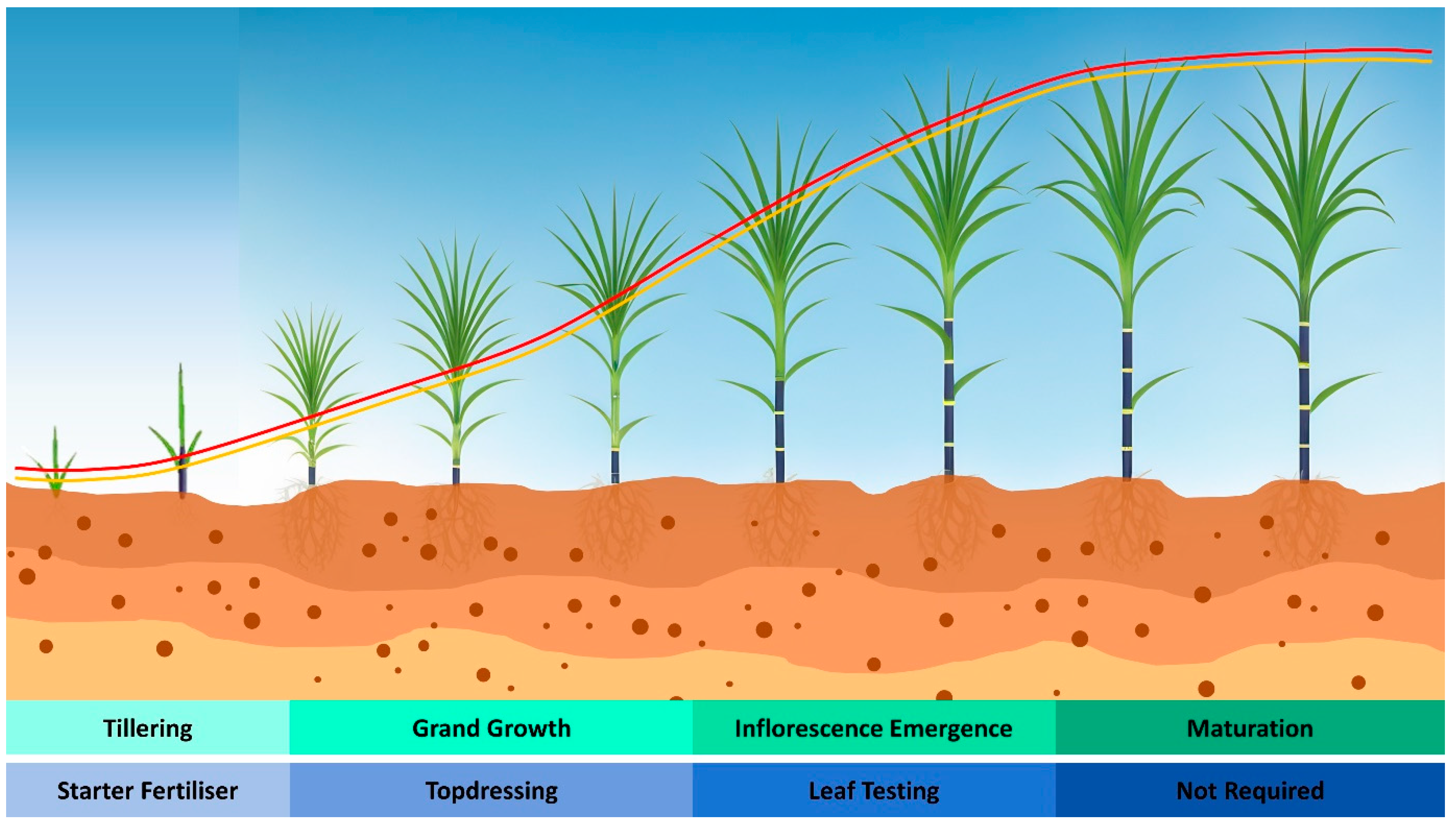

3. Nitrogen Requirement of Sugarcane

4. N Fertiliser Recommendations

5. Challenges in Nitrogen Management Within Sugarcane Farming

5.1. Nitrogen Losses to the Environment

5.2. Causes for Nitrogen Losses

5.3. Environmental and Health Consequences of N Losses

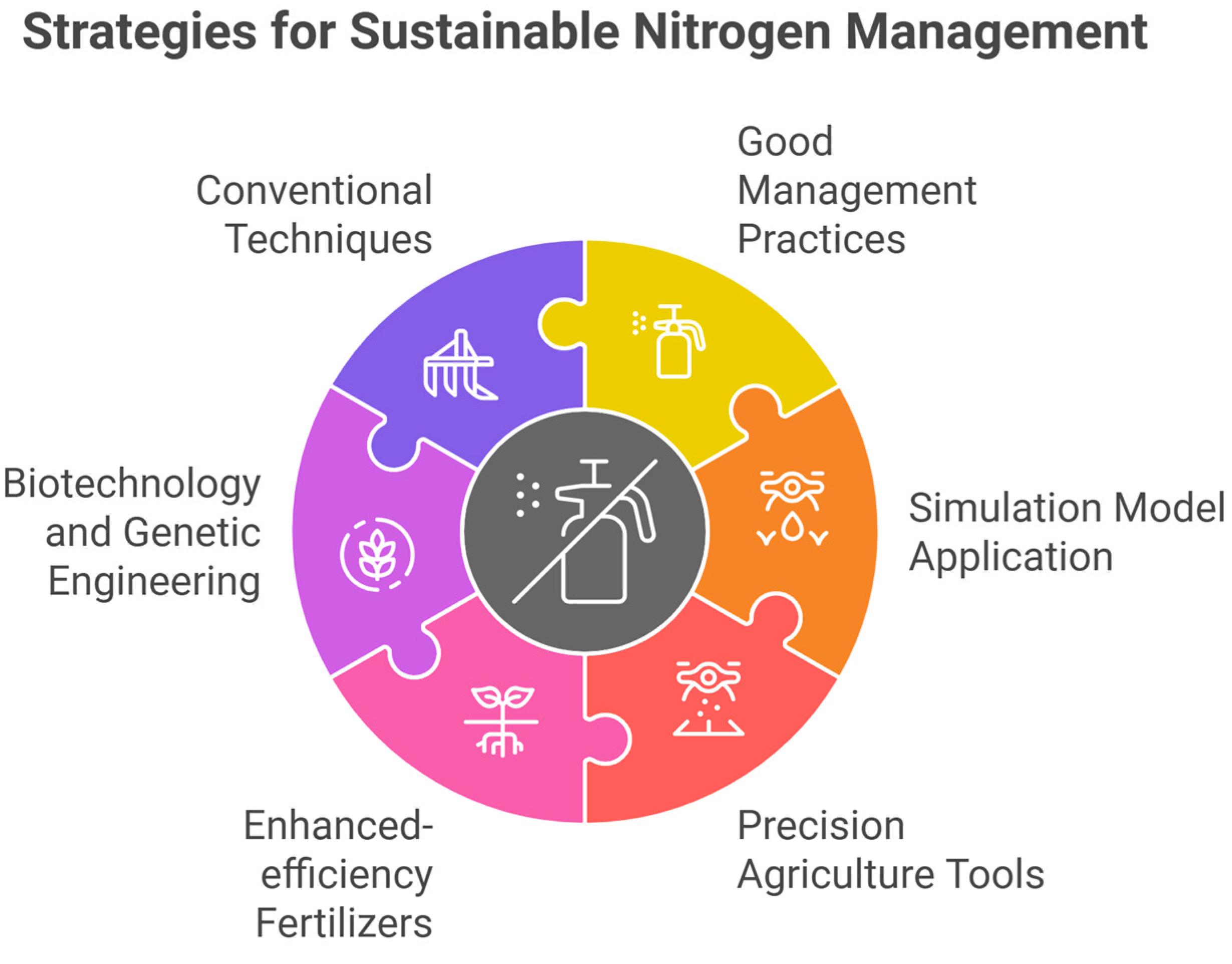

6. Sustainable Nitrogen Management Practices

6.1. Split Nitrogen Application

| Country | No. of Splits | Split levels | Main finding/s | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 2 | 50% of recommendation | Increase in yield | Tenelli et al [69] |

| 4 | 75%, 13%, 7% & 5% of recommendation | Increase in sucrose level | Franco et al [74] | |

| India | 3 | 30, 60 & 90 days after planting | Enhance the quality and quantity of sugarcane for jaggery production | TNAU [75] |

| 4 | 100% (at planting, 30, 60 & 90 DAP) | Improved shoot population at 120 DAP, stalk population at 240 DAP and millable cane population at harvest | Lakshmi et al [77] | |

| 7 | 18.99 and 1.64% higher than the recommended level | 23.9 % increase in millable stalk count, 10.7% increase in internode length, 82.9% increase in cane-to-top ratio | Bhilala et al [76] | |

| 5 | Normal farmer application, 4, 6, 8 & 10 splits | 6 splits N application showed an increase in yield (6 splits > 8 splits > 10 splits > 4 splits > farmer’s practice under drip irrigation) | Singh et al [70] | |

| Pakistan | 2 | 252 kg N ha-1 in 2 equal splits | Higher N rates (336 kg ha-1) also enhanced crop growth rate and leaf area but had lower nitrogen use efficiency. | Ghaffar et al [78] |

| Iran | 2 or 3 | 92 kg N ha-1 and an application pattern of 30-30-40% | Increase the juice purity at 90% application | Koochekzadeh et al [79] |

6.2. Use of Slow-Release or Controlled-Release Nitrogen Fertilizers

6.3. Use of Urease Inhibitors

6.4. Use of Nitrification Inhibitors

6.5. Incorporating Biochar

6.6. Precision Agriculture Tools

6.7. Legume Inter or Rotational Cropping

6.8. Application of Biofertilizers

6.9. Site-Specific N Application

6.10. Use of Nitrogen-Efficient Sugarcane Genotypes

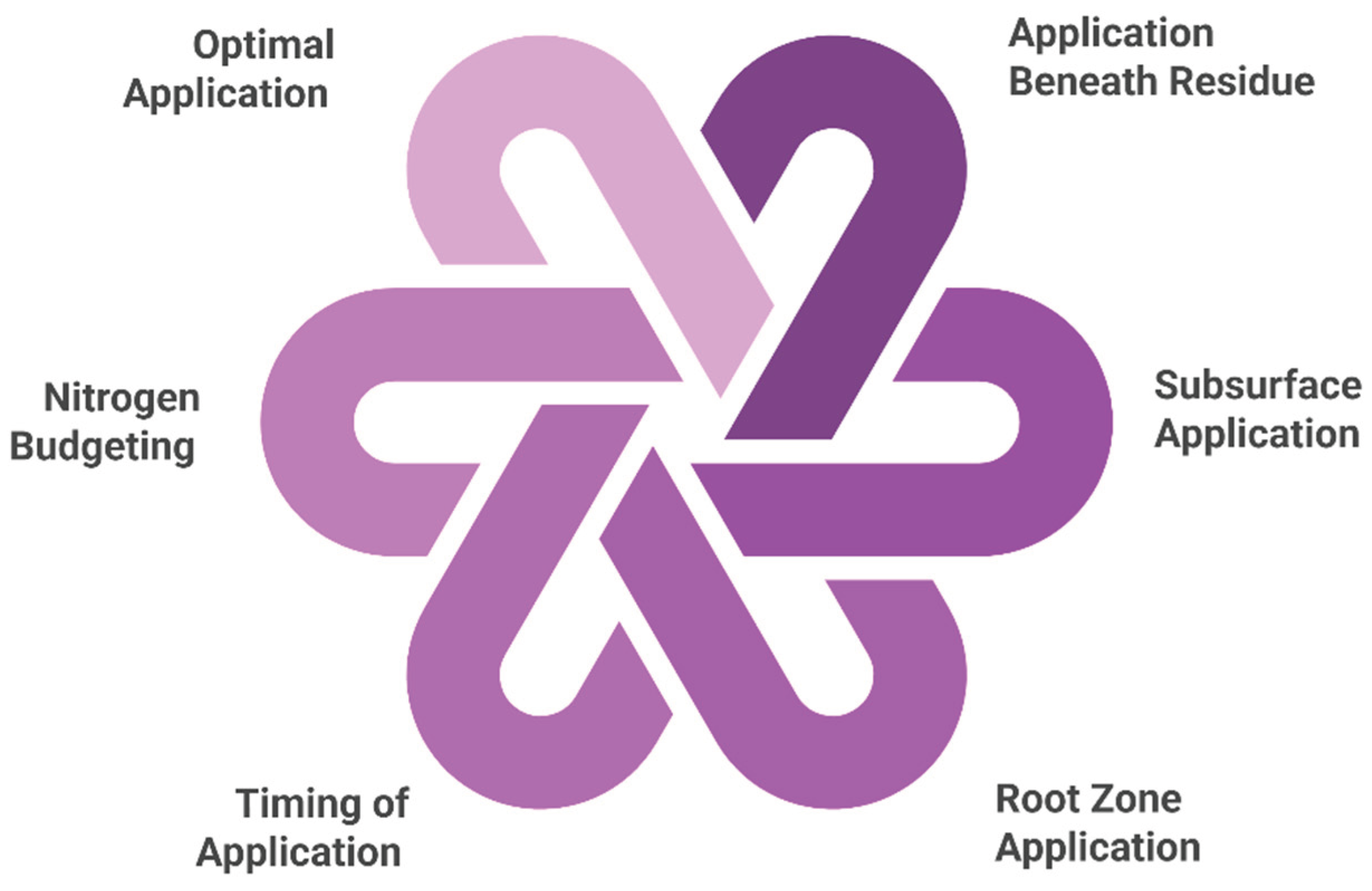

7. Good Management Practices in Nitrogen Management for Sustainable Sugarcane Cultivation

7.1. Fertiliser Application Beneath the Residue

7.2. Subsurface Fertiliser Application

7.3. Application Closer to the Root Zone

7.4. Timing of Fertiliser Application

7.5. Nitrogen Budgeting

7.6. Optimum N Application Rate

8. Adopting Simulation Models for N Management

9. Conclusion and Perspectives

- While limited studies have utilized simulation models to aid N management in sugarcane cultivation, such simulation studies have significant potential to serve as supportive tools in nitrogen management, as evidenced by their application in other plantation crops. Therefore, there is a need for further simulation studies to be conducted to bolster decision-making processes regarding nitrogen management.

- The utilization of Enhanced Efficiency Fertilizers (EEFs), including Slow-Release Fertilizers (SRFs) as well as urease and nitrification inhibitors, remains relatively uncommon within sugarcane agricultural systems. While these methodologies are widely embraced in various other cropping systems, there exists a necessity for further investigations employing recently developed environmentally sustainable EEFs to deepen comprehension of their efficacy within the context of sugarcane cultivation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vandenberghe, L.; Valladares-Diestra, K.; Bittencourt, G.A.; Torres, L.Z.; Vieira, S.; Karp, S.G.; Sydney, E.; de Carvalho, J.C.; Soccol, V.T.; Soccol, C.R. Beyond sugar and ethanol: The future of sugarcane biorefineries in Brazil. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 167, 112721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. FAOSTAT. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Skocaj, D.M.; Everingham, Y.L.; Schroeder, B.L. Nitrogen management guidelines for sugarcane production in Australia: can these be modified for wet tropical conditions using seasonal climate forecasting? Springer Science Reviews 2013, 1, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Singh, S.; Chand, M. Nutrient and water management for higher sugarcane production, better juice quality and maintenance of soil fertility-A review. Agricultural Reviews 2014, 35, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajari, E.; Snyman, S.J.; Watt, M.P. Nitrogen use efficiency of sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) varieties under in vitro conditions with varied N supply. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC) 2015, 122, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCurdy, M.; Davies, C.; Gunaratnam, A.; Grafton, M.; Bishop, P.; Jeyakumar, P. Instrumentation of a bank of lysimeters: Sensors and sensibility. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Chemeca; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gnaratnam, A.; McCurdy, M.; Grafton, M.; Jeyakumar, P.; Bishop, P.; Davies, C. Assessment of nitrogen fertilizers under controlled environment–a lysimeter design. 2019.

- de Castro, S.G.Q.; Decaro, S.T.; Franco, H.C.J.; Graziano Magalhães, P.S.; Garside, A.; Mutton, M.A. Best practices of nitrogen fertilization management for sugarcane under green cane trash blanket in Brazil. Sugar Tech 2017, 19, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Meng, B.; Zhan, J.; Xi, M.; Deng, Y.; Wu, W.; Lakshmanan, P.; Chen, X.; Zhang, F. High sugarcane yield and large reduction in reactive nitrogen loss can be achieved by lowering nitrogen input. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2024, 369, 109032. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Z.; Yin, J.; Eeswaran, R.; Gunaratnam, A.; Wu, J.; Zhang, H. Interacting effects of water and compound fertilizer on the resource use efficiencies and fruit yield of drip-fertigated Chinese wolfberry (Lycium barbarum L.). Technology in Horticulture 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhiram, G.; Eeswaran, R. Legumes for efficient utilization of summer fallow. In Advances in Legumes for Sustainable Intensification; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, S.-Y.; He, K.-H.; Lin, K.-T.; Fan, C.; Chang, C.-T. Addressing nitrogenous gases from croplands toward low-emission agriculture. Npj Climate and Atmospheric Science 2022, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formann, S.; Hahn, A.; Janke, L.; Stinner, W.; Sträuber, H.; Logroño, W.; Nikolausz, M. Beyond sugar and ethanol production: value generation opportunities through sugarcane residues. Frontiers in Energy Research 2020, 8, 579577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA. Production - Sugar. 2025. Available online: https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/production/commodity/0612000.

- Zhao, D.; Li, Y.-R. Climate change and sugarcane production: potential impact and mitigation strategies. International Journal of Agronomy 2015, 2015, 547386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desalegn, B.; Kebede, E.; Legesse, H.; Fite, T. Sugarcane productivity and sugar yield improvement: Selecting variety, nitrogen fertilizer rate, and bioregulator as a first-line treatment. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lofton, J.; Tubaña, B. Effect of nitrogen rates and application time on sugarcane yield and quality. Journal of Plant Nutrition 2015, 38, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschiero, B.N.; Mariano, E.; Torres-Dorante, L.O.; Sattolo, T.M.; Otto, R.; Garcia, P.L.; Dias, C.T.; Trivelin, P.C. Nitrogen fertilizer effects on sugarcane growth, nutritional status, and productivity in tropical acid soils. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 2020, 117, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira-Megda, M.X.; Mariano, E.; Leite, J.M.; Franco, H.C.J.; Vitti, A.C.; Megda, M.M.; Khan, S.A.; Mulvaney, R.L.; Trivelin, P.C.O. Contribution of fertilizer nitrogen to the total nitrogen extracted by sugarcane under Brazilian field conditions. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 2015, 101, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.-P.; Zhu, K.; Lu, J.-M.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, L.-T.; Xing, Y.-X.; Li, Y.-R. Long-term effects of different nitrogen levels on growth, yield, and quality in sugarcane. Agronomy 2020, 10, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingler, A.; Henriques, R. Sugars and the speed of life—Metabolic signals that determine plant growth, development and death. Physiologia Plantarum 2022, 174, e13656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, R. Resources management for sustainable sugarcane production. Resources use efficiency in agriculture 2020, 647–693. [Google Scholar]

- Rozeff, N. A survey of south Texas sugarcane nutrient studies and current fertilizer recommendations derived from this survey. 1990.

- Meyer, J. Sugarcane nutrition and fertilization. Good management practices for the cane industry 2013, 117–168. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, B.; Hurney, A.; Wood, A.; Moody, P.; Allsopp, P. Concepts and value of the nitrogen guidelines contained in the Australian sugar industry's' SIX EASY STEPS'nutrient management program. 2010.

- Tenelli, S.; Otto, R.; de Castro, S.A.Q.; Sánchez, C.E.B.; Sattolo, T.M.S.; Kamogawa, M.Y.; Pagliari, P.H.; Carvalho, J.L.N. Legume nitrogen credits for sugarcane production: implications for soil N availability and ratoon yield. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 2019, 113, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, M.; Garside, A. Growth and yield responses to amending the sugarcane monoculture: interactions between break history and nitrogen fertiliser. Crop and Pasture Science 2014, 65, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overdahl, C.J.; Rehm, G.W.; Meredith, H.L. Fertilizer urea; Minnesota Extension Service, University of Minnesota: 1991.

- Templeman, W. Urea as a fertilizer. The Journal of Agricultural Science 1961, 57, 237–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimohammadi, M.; Panahpour, E.; Naseri, A. Assessing the effects of urea and nano-nitrogen chelate fertilizers on sugarcane yield and dynamic of nitrate in soil. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 2020, 66, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Sharma, L.; Awasthi, S.; Pathak, A. Sugarcane in India. Package of practices for different agro–climatic zones, All Indian Coordinated Research Project on Sugarcane, IISR Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, 2017; 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, R.; Franco, H.C.J.; Faroni, C.E.; Vitti, A.C.; de Oliveira, E.C.A.; Sermarini, R.A.; Trivelin, P.C.O. The role of nitrogen fertilizers in sugarcane root biomass under field conditions. Agricultural Sciences 2014, 5, 1527–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; XiaoZhou, Z.; LiTao, Y. Biological nitrogen fixation in sugarcane and nitrogen transfer from sugarcane to cassava in an intercropping system. 2013.

- Viator, H.P.; Johnson, R.M.; Tubana, B.S. How much fertilizer nitrogen does sugarcane need? Sugar Journal 2013, 76, 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- SRI. 2024. Fertiliser recommendation for sugarcane. ed. CN Division: Sugarcane Research Institute of Sri Lanka.

- DOAFF. 2014. Production guideline, Sugarcane. ed. FaF Department of Agriculture: Agriculture, forestry & Fisheries.

- Yanai, J.; Nakata, S.; Funakawa, S.; Nawata, E.; Katawatin, R.; Kosaki, T. Effect of NPK application on growth, yield and nutrient uptake by sugarcane on a sandy soil in Northeast Thailand. Tropical Agriculture and Development 2010, 54, 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- ell M, Moody P. 2014. Fertilizer N use in the sugarcane industry–an overview and future opportunities. In ‘A review of nitrogen use efficiency in sugarcane, SRA Research Report’.(Ed. MJ Bell) pp. 305-320.(Sugar Research Australia….

- Gravois, K. 2024. Sugarcane soil fertility recommendations for 2024. ed. ARSSR Unit, pp. 1-5: LSU AgCenter.

- CRI. 2024. Sugarcane Nutrition. ed. P Sugar Crop Research Institute (SCRI).

- Armour, J.; Nelson, P.; Daniells, J.; Rasiah, V.; Inman-Bamber, N. Nitrogen leaching from the root zone of sugarcane and bananas in the humid tropics of Australia. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2013, 180, 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Abhiram, G. Contributions of Nano-Nitrogen Fertilizers to Sustainable Development Goals: A Comprehensive Review. Nitrogen 2023, 4, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhiram, G.; Grafton, M.; Jeyakumar, P.; Bishop, P.; Davies, C.E.; McCurdy, M. Iron-rich sand promoted nitrate reduction in a study for testing of lignite based new slow-release fertilisers. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 864, 160949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Suter, H.; Islam, A.; Edis, R.; Freney, J.; Walker, C. Prospects of improving efficiency of fertiliser nitrogen in Australian agriculture: a review of enhanced efficiency fertilisers. Soil Research 2008, 46, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorburn, P.J.; Meier, E.A.; Probert, M.E. Modelling nitrogen dynamics in sugarcane systems: Recent advances and applications. Field crops research 2005, 92, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpare, F.V.; Zotelli, L.d.C.; Barizon, R.; Castro, S.G.Q.d.; Bezerra, A.H.F. Leaching Runoff Fraction for Nitrate and Herbicides on Sugarcane Fields: Implications for Grey Water Footprint. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denmead, O.; Freney, J.; Jackson, A.; Smith, J.; Saffigna, P.; Wood, A.; Chapman, L. Volatilization of ammonia from urea and ammonium sulfate applied to sugarcane trash in North Queensland. Proc. Proc. Austr. Soc. Sugar Cane Technol 1990, 12, 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Freney, J.; Denmead, O.; Wood, A.; Saffigna, P. Ammonia loss following urea addition to sugar cane trash blankets. 1994.

- Takeda, N.; Friedl, J.; Kirkby, R.; Rowlings, D.; De Rosa, D.; Scheer, C.; Grace, P. Interaction between soil and fertiliser nitrogen drives plant nitrogen uptake and nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions in tropical sugarcane systems. Plant and Soil 2022, 477, 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denmead, O.T.; Macdonald, B.; Bryant, G.; Naylor, T.; Wilson, S.; Griffith, D.W.; Wang, W.; Salter, B.; White, I.; Moody, P. Emissions of methane and nitrous oxide from Australian sugarcane soils. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2010, 150, 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedl, J.; Warner, D.; Wang, W.; Rowlings, D.W.; Grace, P.R.; Scheer, C. Strategies for mitigating N2O and N2 emissions from an intensive sugarcane cropping system. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 2023, 125, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degaspari, I.A.M.; Soares, J.R.; Montezano, Z.F.; Del Grosso, S.J.; Vitti, A.C.; Rossetto, R.; Cantarella, H. Nitrogen sources and application rates affect emissions of N 2 O and NH 3 in sugarcane. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 2020, 116, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhiram, G.; McCurdy, M.; Davies, C.E.; Grafton, M.; Jeyakumar, P.; Bishop, P. An innovative lysimeter system for controlled climate studies. Biosystems Engineering 2023, 228, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, A.L.S.; Cherubin, M.R.; Cerri, C.E.; Feigl, B.J.; Reis, A.F.B.; Siqueira-Neto, M. Sugarcane residue and N-fertilization effects on soil GHG emissions in south-central, Brazil. Biomass and Bioenergy 2022, 158, 106342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, N.; Friedl, J.; Rowlings, D.; De Rosa, D.; Scheer, C.; Grace, P. No sugar yield gains but larger fertiliser 15N loss with increasing N rates in an intensive sugarcane system. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 2021, 121, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-R.; Yang, L.-T. Sugarcane agriculture and sugar industry in China. Sugar tech 2015, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasertsak, P.; Freney, J.; Denmead, O.; Saffigna, P.G.; Prove, B.; Reghenzani, J. Effect of fertilizer placement on nitrogen loss from sugarcane in tropical Queensland. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 2002, 62, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quassi de Castro, S.G.; Costa, V.E.; Quassi de Castro, S.A.; Carvalho, J.L.N.; Borges, C.D.; de Castro, R.A.; Kölln, O.T.; Franco, H.C.J. Fertilizer Application Method Provides an Environmental-Friendly Nitrogen Management Option for Sugarcane. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorburn, P.J.; Biggs, J.S.; Weier, K.L.; Keating, B.A. Nitrate in groundwaters of intensive agricultural areas in coastal Northeastern Australia. Agriculture, ecosystems & environment 2003, 94, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud, K.; Panday, D.; Mergoum, A.; Missaoui, A. Nitrogen losses and potential mitigation strategies for a sustainable agroecosystem. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorburn, P.J.; Dart, I.K.; Biggs, I.M.; Baillie, C.P.; Smith, M.A.; Keating, B.A. The fate of nitrogen applied to sugarcane by trickle irrigation. Irrigation Science 2003, 22, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayment, G. Water quality in sugar catchments of Queensland. Water Science and Technology 2003, 48, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, I.; Wicke, B.; Hilst, F.v.d. Spatial variation in environmental impacts of sugarcane expansion in Brazil. Land 2020, 9, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Dai, L.; Guo, H.; Huang, Z.; Chen, T.; Huang, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, C.; Abegunrin, T.P. Control of sugarcane planting patterns on slope erosion-induced nitrogen and phosphorus loss and their export coefficients from the watershed. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2022, 336, 108030. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Wang, J.; Hu, M.; Jia, L. Geographical detection of groundwater pollution vulnerability and hazard in karst areas of Guangxi Province, China. Environmental Pollution 2019, 245, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.; Li, C.; Wang, Z.; Qi, C.; Chen, G.; Fu, Y.; Su, Q.; Xu, X.; Liu, W.; Yu, H. Hydrochemical characteristics and quality assessment of groundwater in Guangxi coastal areas, China. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2023, 188, 114564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, D.; Meng, X.; Wen, X.; Wu, J.; Yu, H.; Wu, M.; Zhou, T. Hydrochemical characteristics, quality and health risk assessment of nitrate enriched coastal groundwater in northern China. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 403, 136872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowers, K.E.; Pan, W.L.; Miller, B.C.; Smith, J.L. Nitrogen use efficiency of split nitrogen applications in soft white winter wheat. Agronomy Journal 1994, 86, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenelli, S.; Otto, R.; Bordonal, R.O.; Carvalho, J.L.N. How do nitrogen fertilization and cover crop influence soil CN stocks and subsequent yields of sugarcane? Soil and Tillage Research 2021, 211, 104999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Singh, R.; Meena, R.; Kumar, V. Nitrogen fertigation schedule and irrigation effects on productivity and economics of spring sugarcane. Indian Journal of Agricultural Research 2019, 53, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gao, S.; Jiang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Luo, J.; Li, M.; Guo, J.; Su, Y.; Xu, L.; Que, Y. The physiological and agronomic responses to nitrogen dosage in different sugarcane varieties. Frontiers in Plant Science 2019, 10, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, H.C.J.; Otto, R.; Faroni, C.E.; Vitti, A.C.; de Oliveira, E.C.A.; Trivelin, P.C.O. Nitrogen in sugarcane derived from fertilizer under Brazilian field conditions. Field Crops Research 2011, 121, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingston, G.; Anink, M.; Allen, D. Acquisition of nitrogen by ratoon crops of sugarcane as influenced by waterlogging and split applications. 2008.

- Franco, H.C.J.; Otto, R.; Vitti, A.C.; Faroni, C.E.; Oliveira, E.C.d.A.; Fortes, C.; Ferreira, D.A.; Kölln, O.T.; Garside, A.L.; Trivelin, P.C.O. Residual recovery and yield performance of nitrogen fertilizer applied at sugarcane planting. Scientia Agricola 2015, 72, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TNAU. Nutrient Management: Sugarcane. 2024. Available online: https://agritech.tnau.ac.in/agriculture/agri_nutrientmgt_sugarcane.html.

- Bhilala, S.; Rana, L.; Kumar, N.; Kumar, A.; Meena, S.K.; Singh, A. Yield and juice quality in sugarcane influenced by split application of nitrogen and potassium under subtropical climates. 2023.

- Lakshmi, M.B.; Srilatha, T.; Ramanamurthy, K.; Devi, T.C.; Gouri, V.; Kumari, M. Response of sugarcane to split application of N and K under seedling cultivation. International Journal of Bio-resource and Stress Management 2020, 11, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffar, A.; Anjum, S.A.; Cheema, M. Effect of nitrogen on growth and yield of sugarcane. J. Am. Soc Sugar Cane. Technol 2012, 32, 75. [Google Scholar]

- Koochekzadeh, A.; Fathi, G.; Gharineh, M.; Siadat, S.; Jafari, S.; Alarni-Saeid, K. Impacts of Rate and Split Application ofN Fertilizer on Sugarcane Quality. International Journal of Agricultural Research 2009, 4, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhiram, G.; Grafton, M.; Jeyakumar, P.; Bishop, P.; Davies, C.E.; McCurdy, M. The nitrogen dynamics of newly developed lignite-based controlled-release fertilisers in the soil-plant cycle. Plants 2022, 11, 3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathnappriya, R.; Sakai, K.; Okamoto, K.; Kimura, S.; Haraguchi, T.; Nakandakari, T.; Setouchi, H.; Bandara, W. Examination of the effectiveness of controlled release fertilizer to balance sugarcane yield and reduce nitrate leaching to groundwater. Agronomy 2022, 12, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, P.C.R.; Paiva, P.E.B.; Charlo, H.C.d.O.; Coelho, V.P.d.M. Slow release fertilizers or fertigation for sugarcane and passion fruit seedlings? Agronomic performance and costs. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 2020, 20, 2175–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, J.R.; Cantarella, H.; Vargas, V.P.; Carmo, J.B.; Martins, A.A.; Sousa, R.M.; Andrade, C.A. Enhanced-efficiency fertilizers in nitrous oxide emissions from urea applied to sugarcane. Journal of environmental quality 2015, 44, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhiram, G.; Bishop, P.; Jeyakumar, P.; Grafton, M.; Davies, C.E.; McCurdy, M. Formulation and characterization of polyester-lignite composite coated slow-release fertilizers. Journal of Coatings Technology and Research 2023, 20, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, K.P.; Saggar, S.; Hanly, J.A.; Guinto, D.F. Urease inhibitors reduced ammonia emissions from cattle urine applied to pasture soil. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 2020, 117, 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, A.; Cantarella, H.; Souza-Netto, G.J.M.d.; Moreira, L.; Kamogawa, M.Y.; Otto, R. Optimizing urease inhibitor usage to reduce ammonia emission following urea application over crop residues. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2017, 248, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, L.A.; Otto, R.; Cantarella, H.; Junior, J.L.; Azevedo, R.A.; de Mira, A.B. Urea-versus ammonium nitrate–based fertilizers for green sugarcane cultivation. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 2021, 21, 1329–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallucci, A.D.; Natera, M.; Moreira, L.A.; Nardi, K.T.; Altarugio, L.M.; de Mira, A.B.; de Almeida, R.F.; Otto, R. Nitrogen-enriched vinasse as a means of supplying nitrogen to sugarcane fields: Testing the effectiveness of N source and application rate. Sugar Tech 2019, 21, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, R.; de Freitas Júnior, J.C.M.; Zavaschi, E.; de Faria, I.K.P.; Paiva, L.A.; Bazani, J.H.; de Mira, A.B.; Kamogawa, M.Y. Combined application of concentrated vinasse and nitrogen fertilizers in sugarcane: strategies to reduce ammonia volatilization losses. Sugar tech 2017, 19, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerri, C.C.; Maia, S.M.F.; Galdos, M.V.; Cerri, C.E.P.; Feigl, B.J.; Bernoux, M. Brazilian greenhouse gas emissions: the importance of agriculture and livestock. Scientia agricola 2009, 66, 831–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, D.; Valencia, A.; Ordonez, D.; Chang, N.-B.; Wanielista, M. Comparative nitrogen removal via microbial ecology between soil and green sorption media in a rapid infiltration basin for co-disposal of stormwater and wastewater. Environmental Research 2020, 184, 109338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Chen, D.; Wang, C.; Chen, D.; Wang, Q. Reduced nitrification by biochar and/or nitrification inhibitor is closely linked with the abundance of comammox Nitrospira in a highly acidic sugarcane soil. Biology and Fertility of Soils 2020, 56, 1219–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorati, M.D.A.; Parton, W.J.; Bell, M.J.; Wang, W.; Grace, P.R. Soybean fallow and nitrification inhibitors: Strategies to reduce N2O emission intensities and N losses in Australian sugarcane cropping systems. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2021, 306, 107150. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Park, G.; Reeves, S.; Zahmel, M.; Heenan, M.; Salter, B. Nitrous oxide emission and fertiliser nitrogen efficiency in a tropical sugarcane cropping system applied with different formulations of urea. Soil Research 2016, 54, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, W.; Tang, L.; Heenan, M.; Xu, Z. Effects of nitrification inhibitor and herbicides on nitrification, nitrite and nitrate consumptions and nitrous oxide emission in an Australian sugarcane soil. Biology and Fertility of Soils 2018, 54, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shinogi, Y.; Taira, M. Influence of biochar use on sugarcane growth, soil parameters, and groundwater quality. Soil Research 2010, 48, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, K.; Nakamura, S.; Kanda, T.; Takahashi, M. Effects of biochar application depth on nitrate leaching and soil water conditions. Environmental Technology 2024, 45, 4848–4859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafti, N.; Wang, J.; Gaston, L.; Park, J.H.; Wang, M.; Pensky, S. Agronomic and environmental performance of biochar amendment in alluvial soils under subtropical sugarcane production. Agrosystems, Geosciences & Environment 2021, 4, e20209. [Google Scholar]

- Eykelbosh, A.J.; Johnson, M.S.; Couto, E.G. Biochar decreases dissolved organic carbon but not nitrate leaching in relation to vinasse application in a Brazilian sugarcane soil. Journal of Environmental Management 2015, 149, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, T.; Lin, Z.; Liu, G.; Wang, X.; Ma, J.; Wang, H.; Jin, H. Biochar application as a tool to decrease soil nitrogen losses (NH 3 volatilization, N2O emissions, and N leaching) from croplands: Options and mitigation strength in a global perspective. Global Change Biology 2019, 25, 2077–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbruzzini, T.F.; Zenero, M.D.O.; de Andrade, P.A.M.; Andreote, F.D.; Campo, J.; Cerri, C.E.P. Effects of biochar on the emissions of greenhouse gases from sugarcane residues applied to soils. Agricultural Sciences 2017, 8, 869–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butphu, S.; Rasche, F.; Cadisch, G.; Kaewpradit, W. Eucalyptus biochar application enhances Ca uptake of upland rice, soil available P, exchangeable K, yield, and N use efficiency of sugarcane in a crop rotation system. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science 2020, 183, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhiram, G. Slow-Release Fertilisers Control N Losses but Negatively Impact on Agronomic Performances of Pasture: Evidence from a Meta-Analysis. Nitrogen 2024, 5, 1058–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, M.M.; Wei, L. perspectives on the roles of real time nitrogen sensing and IoT integration in smart agriculture. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 2024, 171, 027526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, L.R.; Molin, J.P.; Portz, G.; Finazzi, F.B.; Cortinove, L. Comparison of crop canopy reflectance sensors used to identify sugarcane biomass and nitrogen status. Precision Agriculture 2015, 16, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portz, G.; Molin, J.P.; Jasper, J. Active crop sensor to detect variability of nitrogen supply and biomass on sugarcane fields. Precision Agriculture 2012, 13, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Trujillo, A.; Daza-Torres, M.C.; Galindez-Jamioy, C.A.; Rosero-García, E.E.; Muñoz-Arboleda, F.; Solarte-Rodriguez, E. Estimating canopy nitrogen concentration of sugarcane crop using in situ spectroscopy. Heliyon 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.A.; Fiorio, P.R.; Silva, C.A.A.C.; Demattê, J.A.M.; Silva Barros, P.P.d. Application of vegetative indices for leaf nitrogen estimation in sugarcane using hyperspectral data. Sugar Tech 2024, 26, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond Hunt Jr, E.; Daughtry, C.S. Chlorophyll meter calibrations for chlorophyll content using measured and simulated leaf transmittances. Agronomy Journal 2014, 106, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, T.H.; Watanabe, K.; Takaragawa, H.; Nakabaru, M.; Kawamitsu, Y. Photosynthetic response and nitrogen use efficiency of sugarcane under drought stress conditions with different nitrogen application levels. Plant Production Science 2017, 20, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, G.; Santos, M.; Marchiori, P.; Silveira, N.; Machado, E.; Ribeiro, R. Leaf nitrogen supply improves sugarcane photosynthesis under low temperature. Photosynthetica 2019, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.A.; Masoudi, H.; Sajjadiyeh, S.M.; Abdanan Mehdizadeh, S. The determination of Nitrogen Content and Chlorophyll of Sugarcane Crop using Regression Modelling from Color Indices of Aerial Digital Images. Agricultural Engineering 2019, 42, 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- You, H.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, J.; Peng, W.; Sun, C. Sugarcane nitrogen nutrition estimation with digital images and machine learning methods. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 14939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.E.; Webster, T.J.; Horan, H.L.; James, A.T.; Thorburn, P.J. A legume rotation crop lessens the need for nitrogen fertiliser throughout the sugarcane cropping cycle. Field Crops Research 2010, 119, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K. Sustainable sugarcane cultivation: the impact of biological nitrogen fixation on reducing fertilizer use. Field Crop 2024, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Gebrewold, A.Z. Review on integrated nutrient management of tea (Camellia sinensis L.). Cogent Food & Agriculture 2018, 4, 1543536. [Google Scholar]

- Misra, G. Response of sugarcane to green manuring under North Indian conditions. 1971.

- Otto, R.; Pereira, G.L.; Tenelli, S.; Carvalho, J.L.N.; Lavres, J.; de Castro, S.A.Q.; Lisboa, I.P.; Sermarini, R.A. Planting legume cover crop as a strategy to replace synthetic N fertilizer applied for sugarcane production. Industrial Crops and Products 2020, 156, 112853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandagave, R. Agronomic management of intercropping in sugarcane and its economic implications. 2010.

- Bhander, P.; Bhuiya, M.; Salam, M. Effect of Sesbania rostrata biomass and nitrogen fertilizer on the yield and yield attributes of transplant Amam rice. Progressive Agriculture 1998, 9, 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, S.; Solomon, S.; Sharma, L.; Jaiswal, V.; Pathak, A.; Singh, P. Green technologies for improving cane sugar productivity and sustaining soil fertility in sugarcane-based cropping system. Sugar Tech 2019, 21, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herridge, D.F.; Peoples, M.B.; Boddey, R.M. Global inputs of biological nitrogen fixation in agricultural systems. Plant and soil 2008, 311, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viaud, P.; Heuclin, B.; Letourmy, P.; Christina, M.; Versini, A.; Mansuy, A.; Chetty, J.; Naudin, K. Sugarcane yield response to legume intercropped: A meta-analysis. Field Crops Research 2023, 295, 108882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garside, A.; Bell, M. Fallow legumes in the Australian sugar industry: review of recent research findings and implications for the sugarcane cropping system. 2001.

- Ambrosano, E.J.; Cantarella, H.; Ambrosano, G.M.B.; Schammas, E.A.; Dias, F.L.F.; Rossi, F.; Trivelin, P.C.O.; Muraoka, T.; Sachs, R.C.C.; Azcón, R. Productivity of sugarcane after previous legumes crop. Bragantia 2011, 70, 810–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Paungfoo-Lonhienne, C.; Ye, J.; Garcia, A.G.; Petersen, I.; Di Bella, L.; Hobbs, R.; Ibanez, M.; Heenan, M.; Wang, W. Biofertilizers can enhance nitrogen use efficiency of sugarcane. Environmental Microbiology 2022, 24, 3655–3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, K.K.; Smritikana Sarkar, S.S. Biofertilizers, impact on soil fertility and crop productivity under sustainable agriculture. 2019.

- Aguado-Santacruz, G.A.; Arreola-Tostado, J.M.; Aguirre-Mancilla, C.; García-Moya, E. Use of systemic biofertilizers in sugarcane results in highly reproducible increments in yield and quality of harvests. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mendonça, H.V.; Martins, C.E.; da Rocha, W.S.D.; Borges, C.A.V.; Ometto, J.P.H.B.; Otenio, M.H. Biofertilizer replace urea as a source of nitrogen for sugarcane production. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution 2018, 229, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Fageria, N.K.; Baligar, V.C. Fertility management of tropical acid soil for sustainable crop production. In Handbook of soil acidity; CRC Press, 2003; pp. 373–400. [Google Scholar]

- Lofton, J.; Tubana, B.S.; Kanke, Y.; Teboh, J.; Viator, H.; Dalen, M. Estimating sugarcane yield potential using an in-season determination of normalized difference vegetative index. Sensors 2012, 12, 7529–7547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches, G.M.; Magalhães, P.S.; Kolln, O.T.; Otto, R.; Rodrigues Jr, F.; Cardoso, T.F.; Chagas, M.F.; Franco, H.C. Agronomic, economic, and environmental assessment of site-specific fertilizer management of Brazilian sugarcane fields. Geoderma Regional 2021, 24, e00360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landell, M.G.d.A.; Prado, H.d.; Vasconcelos, A.C.M.d.; Perecin, D.; Rossetto, R.; Bidoia, M.A.P.; Silva, M.d.A.; Xavier, M.A. Oxisol subsurface chemical attributes related to sugarcane productivity. Scientia Agricola 2003, 60, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwali, A.; Gascho, G. Soil testing, foliar analysis, and DRIS as guides for sugarcane fertilization 1. Agronomy Journal 1984, 76, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyman, S.; Hajari, E.; Watt, M.; Lu, Y.; Kridl, J. Improved nitrogen use efficiency in transgenic sugarcane: phenotypic assessment in a pot trial under low nitrogen conditions. Plant Cell Reports 2015, 34, 667–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, R.; Trivelin, P.C.O.; Franco, H.C.J.; Faroni, C.E.; Vitti, A.C. Root system distribution of sugar cane as related to nitrogen fertilization, evaluated by two methods: monolith and probes. Revista Brasileira de Ciência do Solo 2009, 33, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, N.; Brackin, R.; Vinall, K.; Soper, F.; Holst, J.; Gamage, H.; Paungfoo-Lonhienne, C.; Rennenberg, H.; Lakshmanan, P.; Schmidt, S. Nitrate paradigm does not hold up for sugarcane. PloS one 2011, 6, e19045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcino, D.; Makepeace, P. Fertiliser placement on green cane trash blanketed ratoons in north Queensland. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Australian Society of Sugar Cane Technologists, 1988.

- Agrawal, S.; Saikanth, D.; Mangaraj, A.; Jena, L.; Boruah, A.; Talukdar, N.; Bahadur, R.; Ashraf, S. Impact of crop residue management on crop productivity and soil health: a review. Int. J. Stat. Appl. Math. 2023, SP-8, 599–605. [Google Scholar]

- Madala, H.V.; Lesmes-Vesga, R.A.; Odero, C.D.; Sharma, L.K.; Sandhu, H.S. Effects of planting pre-germinated buds on stand establishment in sugarcane. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Chen, S.; Qian, W.; He, M.; Chen, P.; Zhou, X.; Qi, Z. Nitrogen losses from soil as affected by water and fertilizer management under drip irrigation: Development, hotspots and future perspectives. Agricultural Water Management 2024, 296, 108791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadu, C.O.; Ezema, C.A.; Ekwueme, B.N.; Onu, C.E.; Onoh, I.M.; Adejoh, T.; Ezeorba, T.P.C.; Ogbonna, C.C.; Otuh, P.I.; Okoye, J.O. Enhanced efficiency fertilizers: Overview of production methods, materials used, nutrients release mechanisms, benefits and considerations. Environmental Pollution and Management 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindasamy, P.; Muthusamy, S.K.; Bagavathiannan, M.; Mowrer, J.; Jagannadham, P.T.K.; Maity, A.; Halli, H.M.; GK, S.; Vadivel, R.; TK, D. Nitrogen use efficiency—a key to enhance crop productivity under a changing climate. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1121073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorburn, P. Review of nitrogen fertiliser research in the Australian sugar industry. 2004.

- Skocaj, D.M.; Everingham, Y.L.; Schroeder, B.L. Nitrogen Management Guidelines for Sugarcane Production in Australia: Can These Be Modified for Wet Tropical Conditions Using Seasonal Climate Forecasting? Springer Science Reviews 2013, 1, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Bharati, R.; Chandra, N.; Sushil Dimree, S.D. Integrated nutrient management system: smart way to improve cane production from sugarcane ratoon. 2015.

- Yadav, V.K.; PratheeshKumar, P.M.; Sivaprasad, V. Effect of nitrification inhibitors on physio-chemical properties, growth and yield attributes of Mulberry (Morusspp.). Environment Conservation Journal 2016, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raun, W.R.; Johnson, G.V. Improving nitrogen use efficiency for cereal production. Agronomy journal 1999, 91, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches, G.M.; Otto, R. A novel approach for determining nitrogen requirement based on a new agronomic principle—sugarcane as a crop model. Plant and Soil 2022, 472, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fageria, N.K.; Baligar, V.C. Enhancing Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Crop Plants. In Advances in Agronomy; Academic Press, 2005; Volume 88, pp. 97–185. [Google Scholar]

- Colasante, A.; Alfarano, S.; Camacho-Cuena, E.; Gallegati, M. Long-run expectations in a learning-to-forecast experiment: a simulation approach. Journal of Evolutionary Economics 2020, 30, 75–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, L.; Charlesworth, P.; Bristow, K.; Thorburn, P. Estimating deep drainage and nitrate leaching from the root zone under sugarcane using APSIM-SWIM. Agricultural Water Management 2006, 81, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Laan, M.; Miles, N.; Annandale, J.; Du Preez, C. Identification of opportunities for improved nitrogen management in sugarcane cropping systems using the newly developed Canegro-N model. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 2011, 90, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorburn, P.J.; Biggs, J.S.; Collins, K.; Probert, M. Using the APSIM model to estimate nitrous oxide emissions from diverse Australian sugarcane production systems. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2010, 136, 343–350. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, M.E.D.; Moraes, S.O. Modeling approaches for agricultural N2O fluxes from large scale areas: A case for sugarcane crops in the state of São Paulo-Brazil. Agricultural Systems 2017, 150, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Liu, E.; Tian, Q.; Yan, C.; Zhang, Y. Soil nitrogen dynamics and crop residues. A review. Agronomy for sustainable development 2014, 34, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquel, D.; Roux, S.; Richetti, J.; Cammarano, D.; Tisseyre, B.; Taylor, J.A. A review of methods to evaluate crop model performance at multiple and changing spatial scales. Precision Agriculture 2022, 23, 1489–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellocchi, G.; Rivington, M.; Donatelli, M.; Matthews, K. Validation of biophysical models: issues and methodologies. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2010, 30, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donatelli, M.; Magarey, R.D.; Bregaglio, S.; Willocquet, L.; Whish, J.P.; Savary, S. Modelling the impacts of pests and diseases on agricultural systems. Agricultural systems 2017, 155, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Country | Major N Source | N Fertilizer Recommendations | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Crop (kgN/ha) | Ratoon Crop (kgN/ha) | |||

| Brazil | Urea | 40–80 | 100–150 | Otto et al [32] |

| India | Urea, Ammonium Sulphate | 135 - 250 | 200 | Shukla et al [31] |

| Thailand | 200-300 | N/A | Yanai et al [37] | |

| Australia | Urea, Controlled- release N | 120–160 | 140–180 | Bell and Moody [38] |

| South Africa | Urea, Ammonium Nitrate | 80 - 200 | 100 - 140 |

DOAFF [36] |

| China | Urea | >500 | >500 | Zeng et al [20] |

| Mexico | Urea, Ammonium Nitrate | 67-112 | 90-135 | Gravois [39] |

| United States | Urea, Ammonium Nitrate, N Solutions | 45 - 90 | 112 - 180 | Viator et al [34] |

| Pakistan | Urea | 173 - 222 | 173 - 222 | SCRI [40] |

| Colombia | Urea, Ammonium Nitrate | 67-112 | 90-135 | Gravois [39] |

| Sri Lanka | Urea | 250-300 | 275-325 | SRI [35] |

| Simulation Model | Prediction | Key Finding | Challenge | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APSIM-SWIM | NO3- leaching | Prediction was reasonable | Preferential flow minimises the accuracy | Stewart et al [152] |

| CANEGRO | NO3- leaching | Prediction accuracy ranged between 0.95-0.98 | - | van der Laan et al [153] |

| APSIM | N2O emission | Close relationship between observed and predicted values | Lower concentrations of N2O highly impact the results | Thorburn et al [154] |

| DNDC | N2O emission | The IPCC method underestimates the emission compared to the DNDC model | Data availability | de Oliveira and Moraes [155] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).