1. Introduction

Alcohol is a toxic substance with psychoactive and dependence-producing effects, potentially leading to a wide spectrum of significant diseases and increased health risks and injuries, as well as a significant health, social, and economic burden [

1].

Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) is a chronic pathological condition that is characterized by the uncontrolled and compulsive use of alcohol, despite adverse consequences, often in the presence of negative emotional states, especially during withdrawal periods of abstinence. Moreover, AUD is associated with an impact on the psycho-physical state of individuals suffering from addiction, resulting in altered information processing and maladaptive behaviours. [

2,

3]. According to the World Health Organization, preventing and treating substance abuse, including harmful alcohol use, through specific interventions based on the best available global evidence, is fundamental to improving the quality of human life [

1].

Despite the effectiveness of the current pharmacological treatments, the ongoing issues with AUD and the high relapse rates necessitate the exploration of novel therapies as well as innovative therapeutic applications of alternative substances, including the use of psychedelic drugs, which have shown promising initial research results [

4].

In a complex and turbulent evolution throughout the world, many cultures used psychedelic compounds for mystical and ritualistic reasons and for curing illnesses [

5]. In the 1950s and 1960s, a great deal of scientific interest encouraged researchers to conduct a range of studies targeting psychological and mental health conditions, including anxiety, depression, and substance abuse disorders. However, in the following decade in the USA, the Controlled Substances Act established drug categorization schedules and requirements within the legal framework for clinical practice. It ended therapeutic research on psychedelics by classifying them as drugs with high potential for abuse and no medical use [

6,

7]. Nevertheless, there has been a resurgence of interest in these substances for medical purposes in the government regulatory bodies, including those in Israel, Australia, the USA, and Canada, which have now permitted the use of psychedelics [

8]. Although some countries continue to prohibit the use of psychedelics, others are at the forefront of introducing those substances to treat mental health disorders, with a significant change in both societal attitudes and the scientific community toward them [

9].

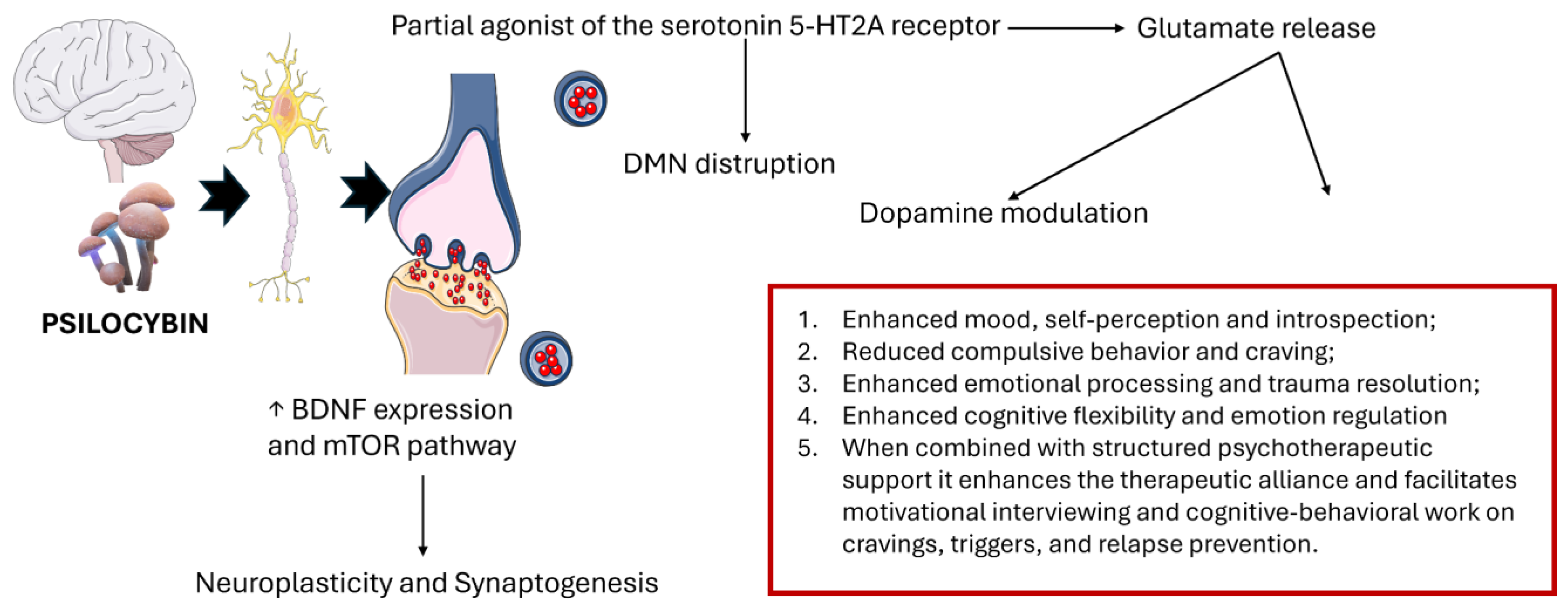

More than 100 species of mushrooms, commonly called "magic mushrooms", worldwide produce psilocybin, a classic hallucinogen with a high affinity for several serotonin receptors. Psilocybin modulates neuroplasticity through multiple neurobiological pathways (

Figure 1). The 5-HT2A receptor reduces thalamic activity, causing sensory changes such as hallucinations [

10]. The 5-HT2A and 5-HT1A receptors are crucial for the regulation of the dopamine-controlled reward system, and psilocybin may help to normalize this imbalance and induce a rapid tolerance to serotonergic input within these circuits by limiting the over-activation of the reward system, ultimately reducing craving symptoms [

11]. In addition, these receptors indirectly modify the release of glutamate, a crucial factor in the pathology of AUD, which is linked to craving and relapse, and contributes to neurotoxicity. A further neuroplasticity mechanism involves postsynaptic activity related to the activation of AMPA receptors, triggered by the release of glutamate, which in turn activates the BDNF-TrkB and mTOR signaling pathways essential for synaptic remodeling and long-term neuroadaptation. Psilocybin may also affect the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocorticoid (HPA) axis, which controls the stress response, a crucial trigger for relapse in AUD [

12].

Beyond these molecular actions, neuroimaging studies have shown how the use of classical psychedelics leads to disruption of the brain's usual network organization, reducing the compartmentalization of the brain and reconfiguring the way information flows. In addition, Psilocybin modifies the key areas of the Default Mode Network (DMN), which plays a key role in various behavioral aspects of addiction and withdrawal [

11,

13,

14].

In addition, psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy (PAT) intervention has been acknowledged for its therapeutic promise and tolerability by the US FDA, as clinical studies highlighted a strong emphasis on the central role of individual experience and the process of subjective interpretation in outcome formation based on the concept of "set and setting". This momentum has been the trigger for investment by various venture capitalists from 2017 to 2021, increasing funding in psychedelic research driven by the progress in clarifying the mechanisms of action of psychedelics and their potential therapeutic application to address unfulfilled clinical needs [

8,

15].

An important goal of pharmacological research is to convert basic biological research findings into useful medical treatments to improve the clinical management of diseases. In drug discovery and development, understanding the molecular mechanisms and the effects of substances on their neurobiological pathways is crucial, as this requires a continuous process of innovation supported by a strategic and managerial framework [

16]. In the current study, we propose a scoping review of the literature to map the existing evidence on the use of psilocybin and its potential efficacy as a promising innovative treatment option for AUD. The study aims to produce a useful synthesis of the literature for policymakers, researchers, and healthcare professionals, highlighting gaps in knowledge and suggesting areas for improvement in future research opportunities, as well as addressing pharmaceutical legislation that regulates the marketing authorization framework [

9].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Processes

This scoping review complied with the PRISMA guidelines, alongside recognized methodological frameworks and optimal procedures for performing scoping reviews [

17,

18,

19]. A comprehensive literature search was conducted on PubMed, CINAHL (via EBSCOhost), and PsycINFO (via EBSCOhost) databases on February 24, 2025, using the following key terms: ‘’Alcohol*’’ OR ‘’Ethanol*’’ OR ‘’drink*’’ OR ‘’liquor*’’ OR ‘’beer*’’ OR ‘’wine*’’ AND "psilocybin" OR "psilocybine" OR "indocybin" OR "psychedelic" OR ‘’dimethyltryptamine’’ OR ‘’4-PO-DMT’’. Articles were screened based on their titles and abstracts; the whole text was reviewed if the title or abstract pertained to treating AUD with Psilocybin.

2.2. Selection of Studies

Articles were included in the review according to the inclusion criteria: article type (i.e., primary research articles), English language, publication in peer-reviewed journals, and articles about studies performed on humans treating AUD with psilocybin.

Eligibility criteria were defined using the PCC (Population, Concept, Context) framework in accordance with the objectives of the scoping review.

Articles were selected by title, abstract, or full text if they lacked relevance to the topic under consideration. Further exclusion criteria were articles not fully written in the English language, unpublished dissertations and theses, and other non-peer-reviewed material.

2.3. Data Extraction

After removing duplicate articles, two researchers conducted preliminary screening, independently evaluating and selecting references according to the established inclusion and exclusion criteria. Another researcher resolved disagreements or controversies during the selection process. The data extraction process was performed, including research author names, publication titles, publication years, study types and designs, demographic characteristics, psilocybin usage types, therapeutic associations, and setting factors highlighting healthcare professionals (

Table S1 Supplementary Material). Data were synthesized in tabular form to summarize key study characteristics, while thematic analysis was carried out through an iterative process and categorization of textual content. A summary of the general characteristics of the included studies was conducted, identifying recurrent patterns and overarching themes. highlighting the most significant observations [

20].

3. Results

A total of 757 records were identified through database searching (PubMed n = 441; CINAHL n = 157; APA PsycINFO n = 159).

Figure 2 presents the PRISMA flow diagram, illustrating the study selection process. Following the removal of 221 duplicates, 536 records underwent screening based on title and abstract. Of these, 470 were excluded due to failure to meet the inclusion criteria. Full texts of 66 potentially relevant articles were retrieved for review, but 4 were not accessible. In total, 62 articles were assessed for eligibility, and 50 were excluded for the following reasons: irrelevant population (n = 17), irrelevant concept (n = 26), or irrelevant context (n = 7). Ultimately, 12 studies were included in the scoping review.

The 12 selected studies, published between 1968 and 2025, investigated the use of psilocybin in the treatment of alcoholism or alcohol use disorder. These studies exhibited heterogeneity in terms of methodological design, sample size, pharmacological dosages, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and outcome measures (

Table 1). Overall, seven randomized controlled trials, four open-label studies, and one case report were included.

Two preliminary open-label studies, conducted between 1968 and 1970 at the Military Medical Academy in Poland, explored the use of psilocybin and other psychedelic stimulants in the treatment of male chronic alcoholics [

21,

33]. In the first study, 14 patients were treated with 6-30 doses of psychedelic stimulants (including psilocybin 9 mg), resulting in a remission of alcohol craving [

21]. The second study, a 6-year follow-up, involving 31 patients with antisocial psychopathic personality, reported satisfactory therapeutic effects in 58% of cases after an average of 15 doses of psilocybin (6-30 mg) and LSD (100-800 µg) [

22]. In both cases, all included patients were adult males.

The remaining included studies were conducted in the United States between 2015 and 2025. Except for a case report on a male patient [

26] and an article that did not specify the demographic characteristics of the sample [

27], the other studies included both men and women in varying proportions.

The majority of the research was conducted in hospital settings or university departments of psychiatry. However, three studies were carried out in clinical settings [

21,

22,

27], while one study did not specify either the setting or the composition of the multidisciplinary team [

29]. Physicians and psychologists were present in all studies, while specialized psychotherapists [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

30,

32] and radiologists [

27,

30] were also involved in some cases.

Generally, most studies involve the combination of one or more administrations of psilocybin with non-pharmacological psychotherapy sessions (e.g., MET, preparation, debriefing, counseling, Visual Healing). However, the four studies did not include any psychotherapeutic support [

21,

22,

29,

31].

Two open-label studies published by the same group in 2015 and 2018 demonstrated that, in a sample of 10 rigorously selected patients (including psychiatric disorders, medical conditions, and prior hallucinogen use), the administration of 2 doses of psilocybin combined with 12 sessions of non-pharmacological psychotherapy led to a mean reduction of 61% in heavy drinking days (26.0% in weeks 5-12), and a mean reduction of 27.2% in the number of drinks consumed per day during the same period. The administered doses were 0.3 mg/kg at week four and 0.4 mg/kg at week eight.

Six randomized clinical trials compared psilocybin with diphenhydramine [

24,

26,

27,

30,

32]. The most commonly used therapeutic regimen involved two sessions: the first at week four with psilocybin 25 mg/70 kg vs. diphenhydramine 50 mg, and the second at week eight with psilocybin 25–40 mg/70 kg vs. diphenhydramine 50–100 mg. Participants who met safety criteria could receive an additional open-label dose of psilocybin at the end of the double-blind treatment. Although the sample sizes were limited, the results indicate that, compared to placebo, psilocybin reduces alcohol craving, alcohol-related problems, anxiety, and depression [

24,

30,

31]. Specifically, the percentage of heavy drinking days in weeks 5–36 decreased to 9.7% in the psilocybin group, compared to 23.6% in the diphenhydramine group (mean reduction: 13.9%) [

26].

A randomized trial conducted in California on 20 patients with moderate to severe alcohol use disorder (DSM-5) compared two groups: one received two 25 mg doses of psilocybin four weeks apart, while the other received the same treatment integrated with the Visual Healing program. Both groups showed a reduction in the average number of weekly drinking days, but the environmentally supported group experienced less peak variation in blood pressure before and after administration [

28].

Finally, a recent case report from a Minnesota group highlighted a severe relapse in alcohol consumption (up to 5 drinks per day for several days) in a patient who, after three months of sobriety, relapsed within two weeks of psilocybin treatment. This finding underscores the importance of long-term follow-up in the evaluation of this therapeutic approach [

29].

4. Discussion

This scoping review synthesized available evidence regarding the use of psilocybin as a pharmacological intervention for AUD, identifying a total of 12 studies published between 1968 and 2025. The selected studies varied significantly in terms of design, sample size, dosing regimens, inclusion criteria, and outcome measures, reflecting both the historical evolution and contemporary resurgence of interest in psychedelic-assisted therapy.

The early open-label studies from Poland (1968–1970) represent some of the first documented uses of psilocybin in alcohol dependence, showing encouraging long-term remission rates. Despite methodological limitations and the inclusion of psychedelic co-interventions, these studies provided early empirical support for the potential of psilocybin in reducing alcohol cravings and promoting behavioral change, even among individuals with severe psychiatric comorbidities.

More rigorous modern trials, predominantly conducted in the United States from 2015 onward, employed standardized dosing protocols (e.g., 0.3 mg/kg, 0.4 mg/kg with a maximum of 2-3 administration sessions), structured psychotherapy integration, and controlled conditions. Across the randomized controlled trials (RCTs), psilocybin was consistently associated with clinically meaningful reductions in heavy drinking days, overall alcohol consumption, and symptoms of depression and anxiety (commonly co-occurring conditions in individuals with AUD). For instance, an interesting RCT showed a reduction in heavy drinking days to 9.7% in the psilocybin group compared to 23.6% in the diphenhydramine group, with a corresponding 13.9% mean reduction over time [

26]. These findings suggest that psilocybin may exert both direct and indirect therapeutic effects by modulating affective and cognitive pathways implicated in addictive behavior. Importantly, psilocybin administration was typically paired with structured psychotherapy, often comprising multiple preparatory and integration sessions. This combination appears to be critical in facilitating the therapeutic potential of psilocybin, promoting insight, emotional processing, and behavior change. A study comparing psilocybin alone versus psilocybin combined with a supportive setting (Visual Healing) indicated superior safety and tolerability outcomes in the latter, underscoring the importance of context, setting, and setting in psychedelic therapy [

28]. Despite overall positive trends, the evidence remains preliminary. Sample sizes were often small, and follow-up durations were generally limited to a few months post-treatment. The recent case report of relapse shortly after psilocybin administration highlights the importance of long-term monitoring and the potential for inter-individual variability in treatment response [

29]. Additionally, the lack of diversity in participant demographics and geographic concentration of recent studies in the U.S. limits the generalizability of findings.

Another critical gap in the literature concerns the mechanisms underlying psilocybin’s efficacy. Psilocin primarily acts as a partial agonist at the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor, which is believed to be central to its psychedelic effects. It also affects 5-HT1A and 5-HT2C receptors. While serotonergic modulation, especially via 5-HT2A receptor activation, has been implicated in altering reward and cognitive control networks, the precise neurobiological pathways mediating sustained reductions in alcohol use remain incompletely understood. Furthermore, safety data, particularly in individuals with psychiatric comorbidities or poly-substance use, require further elucidation. Actually, the various articles partially evaluated safety data by monitoring vital signs (mostly blood pressure and heart rate, sometimes ECG, C-SSRS, urine drug test and alcohol breathalyzer) during psilocybin sessions but there is a lack of systematic data on the safe use of psilocybin especially in individuals with complex psychiatric comorbidities, polysubstance dependence, or chronic medical conditions.

Psilocybin has shown promising effects also in other psychiatric and substance use disorders, including depression [

33] and anxiety [

34], obsessive-compulsive disorder [

35], and tobacco addiction [

36]. In addition, it should be taken into consideration that if on one hand psilocybin seems to be not associated with addiction or overdose, on the other hand there are still psychological risks such as acute anxiety, panic, or “bad trips” (usually transient and manageable in controlled settings) with the potential for triggering psychosis or mania in predisposed individuals (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar I).

5. Conclusions

Psilocybin has emerged as one of the most extensively researched classic psychedelics in the context of modern psychiatry and the treatment of addiction. Current evidence, although limited, suggests that psilocybin-assisted therapy holds promise as a novel and potentially transformative and investigational treatment modality for AUD, associated with reductions in alcohol consumption. However, this field remains in an early experimental phase, meriting cautious optimism but requiring further scientific scrutiny before broad clinical implementation. There is a critical need for larger, multicenter RCTs with longer follow-up periods, diverse populations, and standardized protocols to validate the specific therapeutic efficacy and safety of psilocybin in AUD.

Future research should aim to disentangle the pharmacological effects of psilocybin from the psychotherapeutic context. A significant challenge is related to the complexity of keeping participants unaware of whether they received psilocybin, as its strong effects on thinking and perception may modify the observed effect.

Ongoing innovation, backed by extensive and rigorous testing of new pharmacological treatments with a multi-professional approach, requires a strategic framework that supports drug development for AUD and addresses pharmaceutical legislation regarding safe therapeutic algorithms.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.M. and D.D.; methodology: A.M. and G.G.; software: A.M. and D.D.; Data collection: D.D., F.D., A.M. and S.T.; Formal analysis and writing—original draft preparation: AM; DD; F.D. S.T. and G.G.; writing—review and editing: G.G., A.M and S.T; supervision: S.T.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AUD |

Alcohol Use Disorder |

| DMN |

Default Mode Network |

| PAT |

Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy |

References

- Alcohol Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/alcohol (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Alcohol’s Effects on Health | National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Available online: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohols-effects-health (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Peters J; Olson DE Engineering Safer Psychedelics for Treating Addiction. Neurosci. Insights 2021, 16, 26331055211033847. [CrossRef]

- Jensen ME; Stenbæk DS; Juul TS; Fisher PM; Ekstrøm CT; Knudsen GM; Fink-Jensen A Psilocybin-Assisted Therapy for Reducing Alcohol Intake in Patients with Alcohol Use Disorder: Protocol for a Randomised, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled 12-Week Clinical Trial (The QUANTUM Trip Trial). BMJ Open 2022, 12, e066019. [CrossRef]

- Geyer, M.A. A Brief Historical Overview of Psychedelic Research. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2024, 9, 464–471. [CrossRef]

- Hall W Why Was Early Therapeutic Research on Psychedelic Drugs Abandoned? Psychol. Med. 2022, 52, 26–31. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, N.R.; Preuss, C.V. Controlled Substance Act. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025.

- Adams, D.R.; Allen, H.; Nicol, G.E.; Cabassa, L.J. Moving Psychedelic-Assisted Therapies from Promising Research into Routine Clinical Practice: Lessons from the Field of Implementation Science. Transl. Behav. Med. 2024, 14, 744–752. [CrossRef]

- Soylemez, K.K.; de Boo, E.M.; Lusher, J. Regulatory Challenges of Integrating Psychedelics into Mental Health Sector. Psychoactives 2025, 4, 11. [CrossRef]

- Sharma R; Batchelor R; Sin J Psychedelic Treatments for Substance Use Disorder and Substance Misuse: A Mixed Methods Systematic Review. J. Psychoactive Drugs 2023, 55, 612–630. [CrossRef]

- DiVito AJ; Leger RF Psychedelics as an Emerging Novel Intervention in the Treatment of Substance Use Disorder: A Review. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 9791–9799. [CrossRef]

- Szafoni S; Gręblowski P; Grabowska K; Więckiewicz G Unlocking the Healing Power of Psilocybin: An Overview of the Role of Psilocybin Therapy in Major Depressive Disorder, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Substance Use Disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1406888. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Romeu A; Davis AK; Erowid F; Erowid E; Griffiths RR; Johnson MW Cessation and Reduction in Alcohol Consumption and Misuse after Psychedelic Use. J. Psychopharmacol. Oxf. Engl. 2019, 33, 1088–1101. [CrossRef]

- Bogenschutz MP; Johnson MW Classic Hallucinogens in the Treatment of Addictions. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2016, 64, 250–258. [CrossRef]

- Andrews CM; Hall W; Humphreys K; Marsden J Crafting Effective Regulatory Policies for Psychedelics: What Can Be Learned from the Case of Cannabis? Addict. Abingdon Engl. 2025, 120, 201–206. [CrossRef]

- Gribkoff, V.K.; Kaczmarek, L.K. The Need for New Approaches in CNS Drug Discovery: Why Drugs Have Failed, and What Can Be Done to Improve Outcomes. Neuropharmacology 2017, 120, 11–19. [CrossRef]

- Khalil, H.; Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.M.; McInerney, P.; Soares, C.B.; Parker, D. An Evidence-Based Approach to Scoping Reviews. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2016, 13, 118–123. [CrossRef]

- Parums, D.V. Editorial: Review Articles, Systematic Reviews, Meta-Analysis, and the Updated Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 Guidelines. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2021, 27, e934475. [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Soobiah, C.; Antony, J.; Cogo, E.; MacDonald, H.; Lillie, E.; Tran, J.; D’Souza, J.; Hui, W.; Perrier, L.; et al. A Scoping Review Identifies Multiple Emerging Knowledge Synthesis Methods, but Few Studies Operationalize the Method. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 73, 19–28. [CrossRef]

- Mak, S.; Thomas, A. Steps for Conducting a Scoping Review. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2022, 14, 565–567. [CrossRef]

- Rydzyński, Z.; Cwynar, S.; Grzelak, L.; Jagiello, W. Prelminary Report on the Experience with Psychosomimetic Drugs in the Treatment of Alcobolism. Act. Nerv. Super. (Praha) 1968, 10, 273.

- Rydzyński, Z.; Gruszczyński, W. Treatment of Alcoholism with Psychotomimetic Drugs. A Follow-up Study. Act. Nerv. Super. (Praha) 1978, 20, 81–82.

- Bogenschutz, M.P.; Forcehimes, A.A.; Pommy, J.A.; Wilcox, C.E.; Barbosa, P.C.R.; Strassman, R.J. Psilocybin-Assisted Treatment for Alcohol Dependence: A Proof-of-Concept Study. J. Psychopharmacol. Oxf. Engl. 2015, 29, 289–299. [CrossRef]

- Bogenschutz, M.P.; Podrebarac, S.K.; Duane, J.H.; Amegadzie, S.S.; Malone, T.C.; Owens, L.T.; Ross, S.; Mennenga, S.E. Clinical Interpretations of Patient Experience in a Trial of Psilocybin-Assisted Psychotherapy for Alcohol Use Disorder. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 100. [CrossRef]

- Nielson, E.M.; May, D.G.; Forcehimes, A.A.; Bogenschutz, M.P. The Psychedelic Debriefing in Alcohol Dependence Treatment: Illustrating Key Change Phenomena through Qualitative Content Analysis of Clinical Sessions. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 132. [CrossRef]

- Bogenschutz, M.P.; Ross, S.; Bhatt, S.; Baron, T.; Forcehimes, A.A.; Laska, E.; Mennenga, S.E.; O’Donnell, K.; Owens, L.T.; Podrebarac, S.; et al. Percentage of Heavy Drinking Days Following Psilocybin-Assisted Psychotherapy vs Placebo in the Treatment of Adult Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2022, 79, 953–962. [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.C.; Mennenga, S.E.; Owens, L.T.; Podrebarac, S.K.; Baron, T.; Rotrosen, J.; Ross, S.; Forcehimes, A.A.; Bogenschutz, M.P. Psilocybin for Alcohol Use Disorder: Rationale and Design Considerations for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2022, 123, 106976. [CrossRef]

- Heinzerling, K.G.; Sergi, K.; Linton, M.; Rich, R.; Youssef, B.; Bentancourt, I.; Bramen, J.; Siddarth, P.; Schwartzberg, L.; Kelly, D.F. Nature-Themed Video Intervention May Improve Cardiovascular Safety of Psilocybin-Assisted Therapy for Alcohol Use Disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1215972. [CrossRef]

- Frye, M.A.; Singh, B.; Breitinger, S.A.; Oesterle, T.S. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Discontinuation for Psilocybin Treatment and Contributions to Alcohol Addiction Relapse: A Cautionary Tale. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2024, 85, 24cr15378. [CrossRef]

- Pagni, B.A.; Petridis, P.D.; Podrebarac, S.K.; Grinband, J.; Claus, E.D.; Bogenschutz, M.P. Psilocybin-Induced Changes in Neural Reactivity to Alcohol and Emotional Cues in Patients with Alcohol Use Disorder: An fMRI Pilot Study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3159. [CrossRef]

- Agin-Liebes, G.; Nielson, E.M.; Zingman, M.; Kim, K.; Haas, A.; Owens, L.T.; Rogers, U.; Bogenschutz, M. Reports of Self-Compassion and Affect Regulation in Psilocybin-Assisted Therapy for Alcohol Use Disorder: An Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis. Psychol. Addict. Behav. J. Soc. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2024, 38, 101–113. [CrossRef]

- Pagni, B.A.; Zeifman, R.J.; Mennenga, S.E.; Carrithers, B.M.; Goldway, N.; Bhatt, S.; O’Donnell, K.C.; Ross, S.; Bogenschutz, M.P. Multidimensional Personality Changes Following Psilocybin-Assisted Therapy in Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder: Results From a Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 2025, 182, 114–125. [CrossRef]

- Wall, M.B.; Demetriou, L.; Giribaldi, B.; Roseman, L.; Ertl, N.; Erritzoe, D.; Nutt, D.J.; Carhart-Harris, R.L. Reduced Brain Responsiveness to Emotional Stimuli With Escitalopram But Not Psilocybin Therapy for Depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2025, appiajp20230751. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, R.R.; Johnson, M.W.; Carducci, M.A.; Umbricht, A.; Richards, W.A.; Richards, B.D.; Cosimano, M.P.; Klinedinst, M.A. Psilocybin Produces Substantial and Sustained Decreases in Depression and Anxiety in Patients with Life-Threatening Cancer: A Randomized Double-Blind Trial. J. Psychopharmacol. Oxf. Engl. 2016, 30, 1181–1197. [CrossRef]

- Geiger, H.A.; Wurst, M.G.; Daniels, R.N. DARK Classics in Chemical Neuroscience: Psilocybin. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 2438–2447. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.W.; Garcia-Romeu, A.; Cosimano, M.P.; Griffiths, R.R. Pilot Study of the 5-HT2AR Agonist Psilocybin in the Treatment of Tobacco Addiction. J. Psychopharmacol. Oxf. Engl. 2014, 28, 983–992. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).