1. Introduction:

1.1. Importance of Underground Hydrogen Storage (UHS):

Energy production from fossil fuels has greatly impacted global warming and climate change as a result of increasing anthropogenic CO2 emissions. Achieving a successful transition into a low-carbon energy industry requires adequate utilization of renewable energy resources. Currently, several regions have established long-term goals of achieving net-zero CO2 emissions by 2050, and as a result, much attention has been directed to exploring alternatives to replace fossil fuel energies. Hydrogen is regarded as a clean energy source, because hydrogen production has almost zero CO2 emissions (Giacomo Rivolta1*, 2024). Low density of the substance, which indicates more volumetric capacity than other gases like CH4 and lower temperatures to suit storage facilities, has caused storage problems, nevertheless. This has demanded investigating substitutes such underground hydrogen storage in porous media (UHSP), basically taken from exhausted hydrocarbon reserves and saline aquifers. Many depleted shale basins throughout the United States have great volumetric capacity perhaps fit for hydrogen storage (Elie Bechara*1, 2022). Large-scale, long-term storage is thought to be best accomplished by geological storage. Underground geological formations include aquifers, rock caves, depleted oil and gas reserves can all have hydrogen.

The role of hydrogen storage is crucial in improving the stability of electricity systems, facilitating the integration of renewable energy sources, and promoting decarbonization initiatives. This solution offers sustained energy storage, bolsters energy security, and fuels both industries and transportation (Kwamena Opoku Duartey 1, 2025). Underground natural gas storage exhibits numerous parallels with underground hydrogen storage. From a geological perspective, underground space presents an ideal option for hydrogen storage. This hydrogen can serve as an energy carrier during periods of surplus energy production, allowing it to be released back into the electrical grid during peak demand, when its value is maximized (Tarkowski, 2019). Different methods of storage for hydrogen are evaluated, including porous rocks such as depleted natural gas and oil deposits, aquifers, as well as artificial underground spaces like salt caverns and abandoned mine workings.

1.2. Role of Shale and Tight Reservoirs in Energy Storage:

A good reservoir for a hydrogen storage system should possess appropriate porosity and permeability along with a strong caprock seal. Depth deposits, lithology of the site storage, storage capacity, geological tightness, recent experience, availability of structures, and current infrastructure define different techniques of geological storage development. Site selection depends critically on geological, technological, environmental, and financial aspects as well as on site location (Kwamena Opoku Duartey 1, 2025). Shale and tight reservoirs refer to types of rock formations that are less permeable compared to conventional reservoirs, which makes extracting hydrocarbons (like oil and gas) from them more challenging. Shale is a fine-grained sedimentary rock that often contains significant amounts of organic material. Over millions of years, this organic material can transform into hydrocarbons, making shale a common source rock for oil and gas. However, shale itself is typically low in permeability (the ability of fluids to flow through the rock), meaning oil and gas are not easily extracted without advanced techniques. Hydraulic fracturing (fracking) is commonly used to release hydrocarbons from shale reservoirs. Shale reservoirs, like the Bakken Formation or the Eagle Ford Shale, have become major sources of oil and gas production in the U.S. due to advances in drilling and fracking technologies.

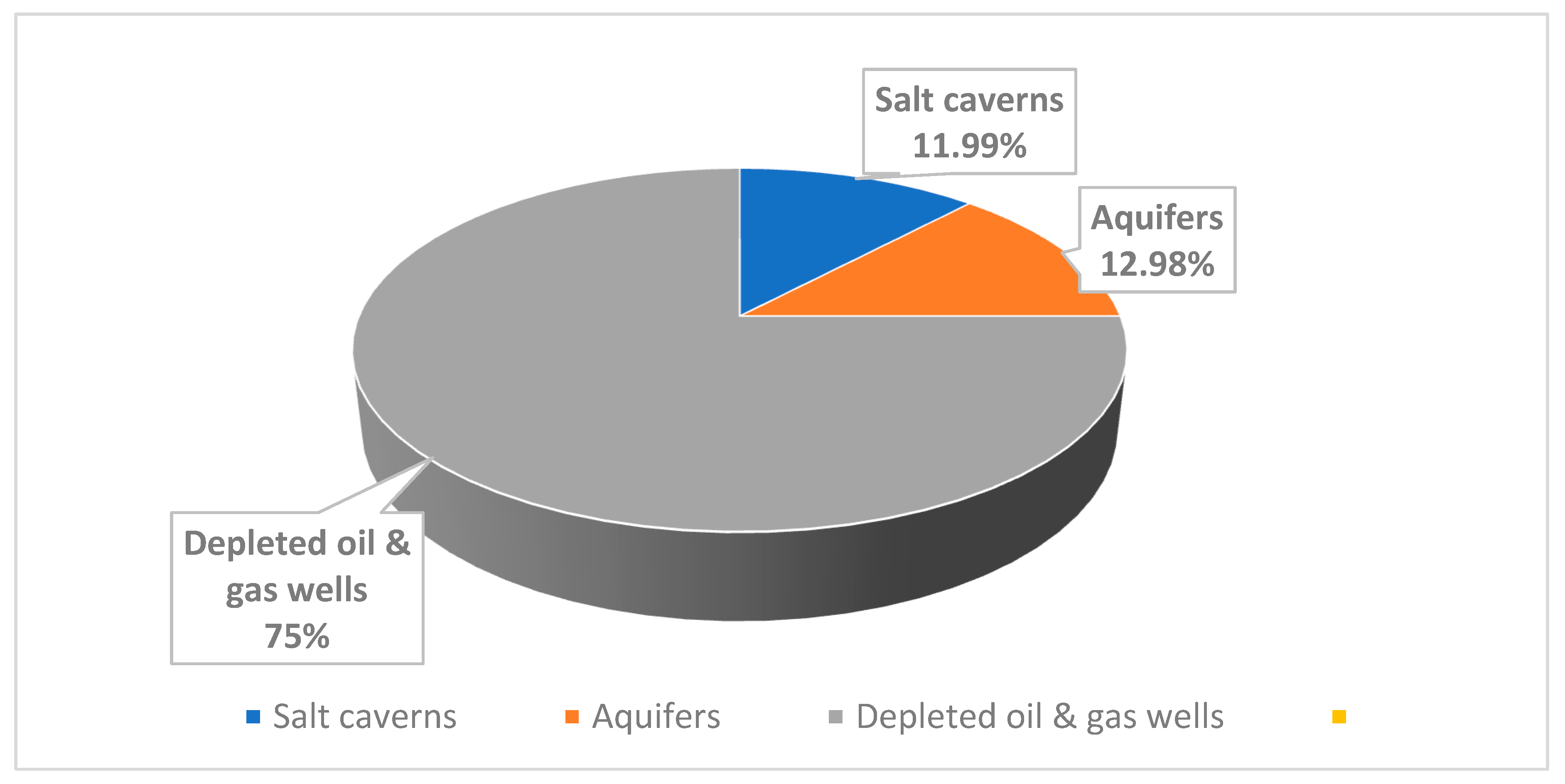

Tight reservoirs are similarly low-permeability rock formations, often made up of sandstone, limestone, or shale that are compacted tightly, preventing oil or gas from flowing easily. These reservoirs are “tight” because the pores or fractures in the rock are so small and not well connected, making it difficult for hydrocarbons to move through them naturally. Nonetheless, the long-term storage of substantial quantities of hydrogen as an auxiliary energy source has proven to be a complex issue. To tackle this challenge, traditional underground geological storage options like depleted oil and gas reservoirs, aquifers, or caverns present viable possibilities. Primarily, depleted gas reservoirs are viewed as the most feasible option due to their technological advantages (significant storage capacity) and economic benefits. Furthermore, the depleted shale gas reservoirs present a promising option for hydrogen storage in conjunction with traditional storage reservoirs. Their tight porosity and permeability, extensive distribution, and elevated capillary pressures could either hinder the escape of hydrogen or considerably impede its movement, along with accommodating its substantial volume. Shale gas reservoirs represent complex heterogeneous porous materials, consisting of two primary components: organic matter (carbonaceous kerogen) and inorganic minerals (Hussein*, 2023). The below graph 1 shows the data of the various UGS storage types in the world (Tarkowski, 2019).

Figure 1.

Distribution of underground gas storage by type globally (2010).

Figure 1.

Distribution of underground gas storage by type globally (2010).

This research employs a multidisciplinary approach, integrating geological, geochemical, and engineering viewpoints to provide a thorough understanding of UHS in tight and shale formations. The procedure starts with an evaluation of reservoir attributes, examining the storage potential of shale and tight reservoirs compared to conventional storage sites such as depleted gas fields and salt caverns. The analysis subsequently explores geomechanical and geochemical issues, scrutinizing elements like fracture dynamics, containment hazards, and hydrogen-induced changes in rock characteristics. Additionally, the investigation examines the dynamics of hydrogen flow within low-permeability formations, tackling the complexities related to injection and withdrawal cycles. Findings from experimental studies, numerical modeling, and field-scale applications are compiled to highlight significant limitations, technological progress, and optimal practices for enhancing hydrogen storage.

This research focuses on identifying key challenges that currently hinder the industrial use of underground hydrogen storage (UHS) in unconventional reservoirs, such as data gaps, scale-up difficulties, and long-term monitoring risks. It also takes a closer look at important factors like sustainability, regulatory frameworks, and economic viability to ensure that any proposed storage solutions align with broader goals of energy security and environmental protection. Overall, this study aims to serve as a strategic guide, offering a clear and practical roadmap for advancing safe, efficient, and scalable hydrogen storage systems in shale and tight formations.

2. Geological and Reservoir Characteristics:

2.1. Features of Shale and Tight Reservoirs:

A significant challenge involves the geochemical reactions among rock, hydrogen, and formation brine, which may lead to mineral dissolution or precipitation and modifications in petrophysical properties, consequently impacting storage capacity and withdrawal efficiency. Carbonate reservoirs are often suitable for UHS owing to their pronounced hydrophilic wettability and specific rock-fluid interfacial tension properties. In the geological storage of hydrogen, in addition to the hydrogen solubility or trapping in the formation fluids, it is also essential to understand the hydrogen-mineral geochemical reactions in the subsurface condition and evaluate the implications on other parameters (Ahmed Al-Yaseri, 2024).

Depth deposits, lithology of the site storage, storage capacity, geological tightness, recent experience, availability of structures, and current infrastructure define different techniques of geological storage development. Site choosing depends critically on geological, technological, environmental, and financial aspects. Key mitigating strategies used include selective technology, increasing the number of storage cycles, improving the layout of extraction wells, and limiting the injection rate (Kwamena Opoku Duartey 1, 2025). Storage is much troubled by hydrogen’s low density, tiny molecular size, and viscosity. A good reservoir for a hydrogen storage system should have suitable permeability and porosity with a great caprock seal. Porosity and permeability are the fundamental properties for the reservoir evaluation and production control. Besides, total organic carbon content (TOC) is another key property for the evaluation of shale reservoirs. The higher the TOC, the higher is the potential for hydrocarbons production (Xingye Liu, 2023). Therefore, porosity, permeability, and TOC are crucial parameters to characterize shale gas reservoirs and evaluate production potential. For conventional reservoirs, geologists usually set up this relationship depending on petrophysical modeling. However, shale gas reservoirs are more complex due to low permeability and porosity. Besides, as the organic matter has been deposited in shale rocks, the properties and composition of shale formations is distinguished from other stones. The major marine shale oil reservoirs in the U.S. are dominated by Type-II kerogen with relatively high abundance of TOC of generally greater than 3%, and relatively high maturity with

Ro values of 0.6%-1.5% (Zaixing Jiang 1, 2017). The below

Table 1 organic geochemical parameters of continental shale oil.

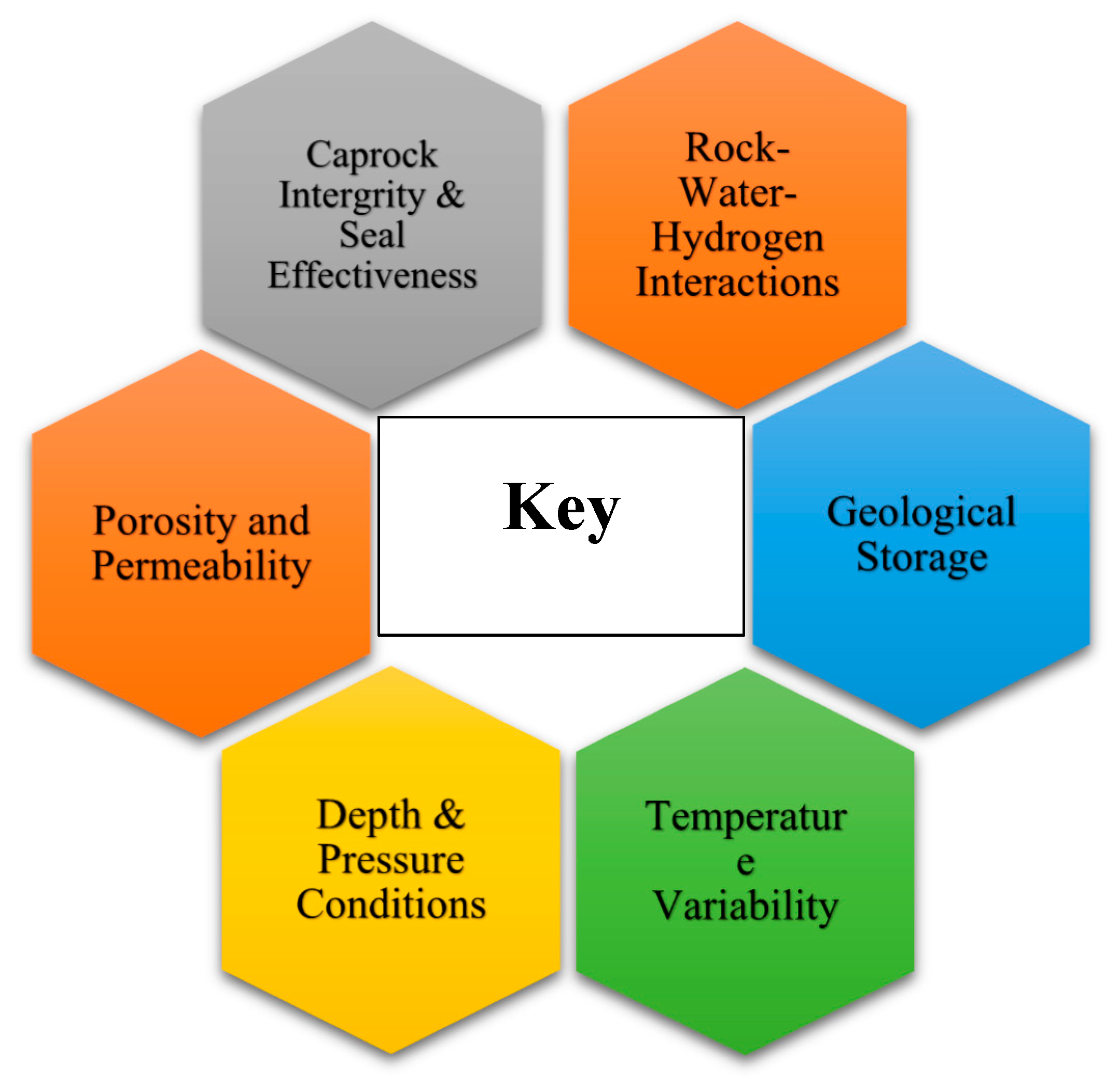

2.2. Essential Factors Affecting Hydrogen Storage Capability:

Underground hydrogen storage (UHS) in geological formations is only feasible when key conditions are met ones that determine how much hydrogen can be stored, how well it’s contained, and how efficiently it can be retrieved.

2.2.1. Porosity and Permeability:

The amount of hydrogen that can be stored in a rock formation largely depends on its porosity higher porosity means more space to hold hydrogen. Permeability, on the other hand, affects how easily hydrogen can be injected into and withdrawn from the formation. In denser rocks with low permeability, it may be necessary to use artificial stimulation techniques to improve flow and make storage more effective.

2.2.2. Caprock Integrity and Seal Effectiveness:

A low-permeability caprock, like shale or salt formations, plays a crucial role in inhibiting hydrogen migration and leakage. The integrity of the seal must endure cyclic injection and withdrawal without exhibiting any fractures.

2.2.3. Rock-Water-Hydrogen Interactions:

The interaction of hydrogen with reservoir minerals and formation water has the potential to influence storage efficiency. Specific minerals, including iron oxides, can facilitate hydrogen consumption via redox reactions, which may hinder recoverability.

2.2.4. Depth and Pressure Conditions:

Shallow formations, particularly those less than 500 meters deep, are susceptible to hydrogen loss as a result of microbial activity. Deeper formations exceeding 1000 meters offer enhanced pressure, which boosts hydrogen density, yet this also leads to increased operational expenses.

2.2.5. Temperature Variability:

Elevated temperatures could potentially improve hydrogen diffusivity and lead to higher loss rates. Consistent temperature conditions in deep saline aquifers or depleted gas fields create an improved environment for storage.

2.2.6. Geological Storage Types and Suitability:

Exhausted oil and gas reservoirs; thoroughly analyzed, with established infrastructure in place. Deep saline aquifers present significant storage potential; however, there is considerable uncertainty regarding their sealing capacity. Salt caverns demonstrate exceptional containment capabilities owing to their impermeable salt formations, making them a preferred choice for hydrogen storage.

Figure 2.

This pertains to all the essential parameters of the UHS Formations.

Figure 2.

This pertains to all the essential parameters of the UHS Formations.

2.3. Comparison with Conventional Storage Reservoirs:

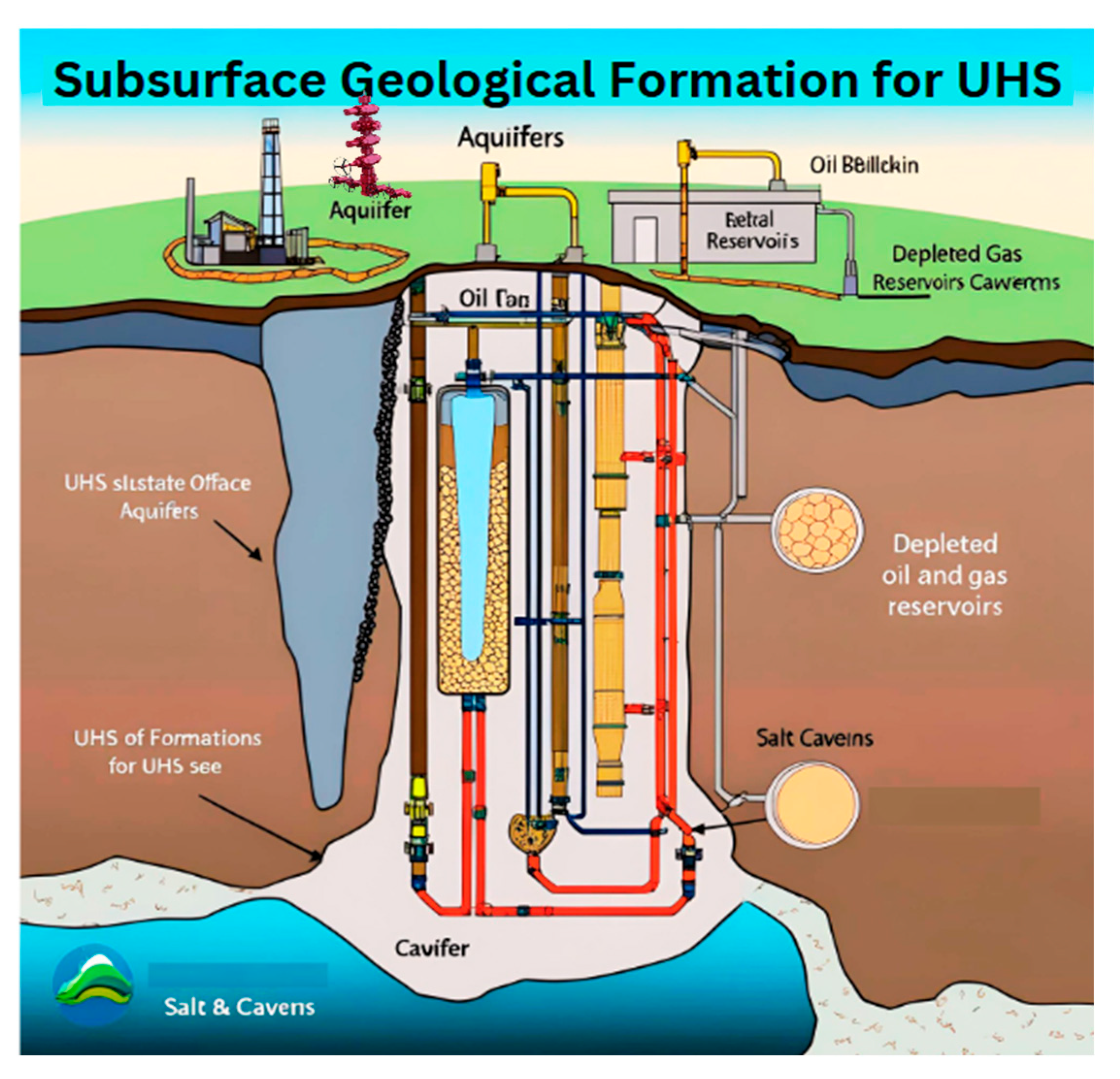

Geological formations with naturally high porosity and permeability that is, conventional storage reservoirs are perfect for storing and recovering fluids, including hydrocarbons and gases including hydrogen. Usually well-characterised, these reservoirs have been extensively exploited in the oil and gas sector. Still, the great diffusivity and corrosive properties of hydrogen provide unique difficulties for subterensive storage. Underground hydrogen storage is the confinement of high-pressure hydrogen within geological formations comprising aquifers, caverns, abandoned mines, depleted natural gas and oil reserves (P. Muthukumar a, 2023). Apart from the usual gas losses resulting from microbial activity or mineral interactions in geological formations, hydrogen could also be lost by trapping in pore-scale capillaries. Still, our main emphasis right now is on carefully evaluating the storage facility. The below depicted

Figure 3 gives us a better understanding about UHS types.

2.3.1. Utilization of Depleted Oil and Gas Reservoirs for Storage:

An impermeable caprock reinforces depleted oil and gas fields; aquifers on the sides and underneath them as well. The current hydrocarbon reserves show that caprock integrity is fully known. Consideration of elements like formation storage capacity, storage depth, and caprock formation thickness helps one choose a storage site. Mostly by reversible trapping processes comprising structural/stratigraphic, capillary trapping, and solubility/dissolution in fluids, hydrogen is maintained in geological formations. UHS in depleted reservoirs must satisfy certain criteria if it is to operate consistently over a long period (Kwamena Opoku Duartey 1, 2025). Hydrogen present in oil fields could react with leftover oil to produce methane and therefore a decrease in stored gas level.

On the other hand, hydrogen storage in natural gas fields has advantages as the leftover gas can act as a cushion, thereby maintaining the suitable pressure and guaranteeing enough deliverability (P. Muthukumar a, 2023). In the presence of pollutants like methanogenic and sulfate-reducing bacteria, there can be significant hydrogen depletion. Particularly in depleted oil and gas reservoirs, the prospective of clathrate hydrate for hydrogen storage presents an interesting possibility for subterranean storage. There is already a lot of data about the location as comprehensive geological studies are carried out before the exploration and exploitation from a gas field. For hydrogen storage, this offers a significant financial benefit as well. Maintaining low porosity and permeability is vital to prevent leakage; a hydraulic fracture threshold advised to be below 10−8 ms−1. The location should show resistance to hydraulic fracturing, guaranteeing temperature stability between 4 ◦C and 80 ◦C, and simultaneously sustain a storage lifetime spanning 28–30 years (Shree Om Bade, 2024). The described requirements are absolutely necessary to guarantee the efficient and safe usage of depleted reservoirs for long-term storage needs.

2.3.2. Storage in Aquifers:

Aquifers, or groundwater reservoirs lying in porous rock formations, have historically served as safe natural gas storage locations. This property makes them a feasible alternative for hydrogen storage as well. To transfer hydrogen efficiently through an aquifer, the overlying rock must have high porosity and permeability. Simultaneously, the existence of a low-permeability cap rock above the aquifer is required to prevent gas leakage. However, due to the unique chemical properties of hydrogen, research must focus on certain geological formations. In contrast to depleted oil and gas resources, iron or sulfur-rich aquifers may not be ideal for hydrogen storage. Furthermore, aquifers typically require around 80% cushion gas for stable storage, compared to just 50-60% in depleted fields (Kwamena Opoku Duartey, 2025).

Thus, choosing an appropriate gas type for cushioning is absolutely important for aquifer storage projects. Given the physiochemical characteristics of hydrogen, major financing for subsurface infrastructure—including wells and injection systems—is needed to convert from subterranean gas storage to hydrogen storage in aquifers, hence improving its economic viability (Katz & Tek, 1970). Aquifers’ underground hydrogen storage has to be sensible and reasonably affordable. To do this, one must solve problems like to those encountered in the storage utilizing of depleted reservoirs. While the storage development should have a porosity more than 10%, a thickness of at least 300 m, and a vertical closure at least 10 m, optimal storage depth varies from 200 to 2000 m. To keep reservoir integrity and storage performance, the discovery pressure should also fall between 2 and 8 MPa. UES’s effective application in saline aquifers depends on these criteria (Shree Om Bade, 2024).

2.3.3. Salt Caverns Storage:

Salt caverns are pits produced in subterranean salt reservoirs by solution mining. Solution mining is the method of producing salt by means of high-pressure water injection into subterranean salt reservoirs. Two forms of salt deposits allow caverns to develop: salt domes and bedded salts. Salt domes are homogenous, thick heaps of salt that make building a stable cavern for normal activities simple. Still, even with a well-designed cavern, if the depth is more than 6000 feet below the ground, excessive pressure and temperature might cause the salt to distort (Shree Om Bade, 2024). The gas finds an impenetrable layer inside the cavern walls. From 100,000 to 1,000,000m3 (P. Muthukumar a, 2023), the actual volume of salt caves might vary Various strata of cavernous lithology have unique characteristics that affect sliding behavior, deformation, and creep rates along the bedding planes.

With its ability to reach depths of over two kilometers and retain as much as one million cubic meters of working gas, caverns are fascinating. Reaching depths of 900 to 1100 meters, the 60.5 km² Jintan salt mine in Jiangsu province, China, For large-scale hydrogen storage systems, this offers a rather exciting alternative. Usually, the maximum pressure is kept between 75 and 85% of the original vertical beginning stress component (Kwamena Opoku Duartey 1, 2025) to reduce structural loss resulting from salt hydraulic fracturing and possible collapse of the cemented well casing. With a 30 to 50 year expected storage lifetime, salt caverns provide a consistent and efficient option for subterranean hydrogen storage. Salt caverns are unique from other storage choices including drained reservoirs and aquifers, each with their own set of advantages and drawbacks.

Table 2 depicts the comparison with Unconventional storage reservoirs.

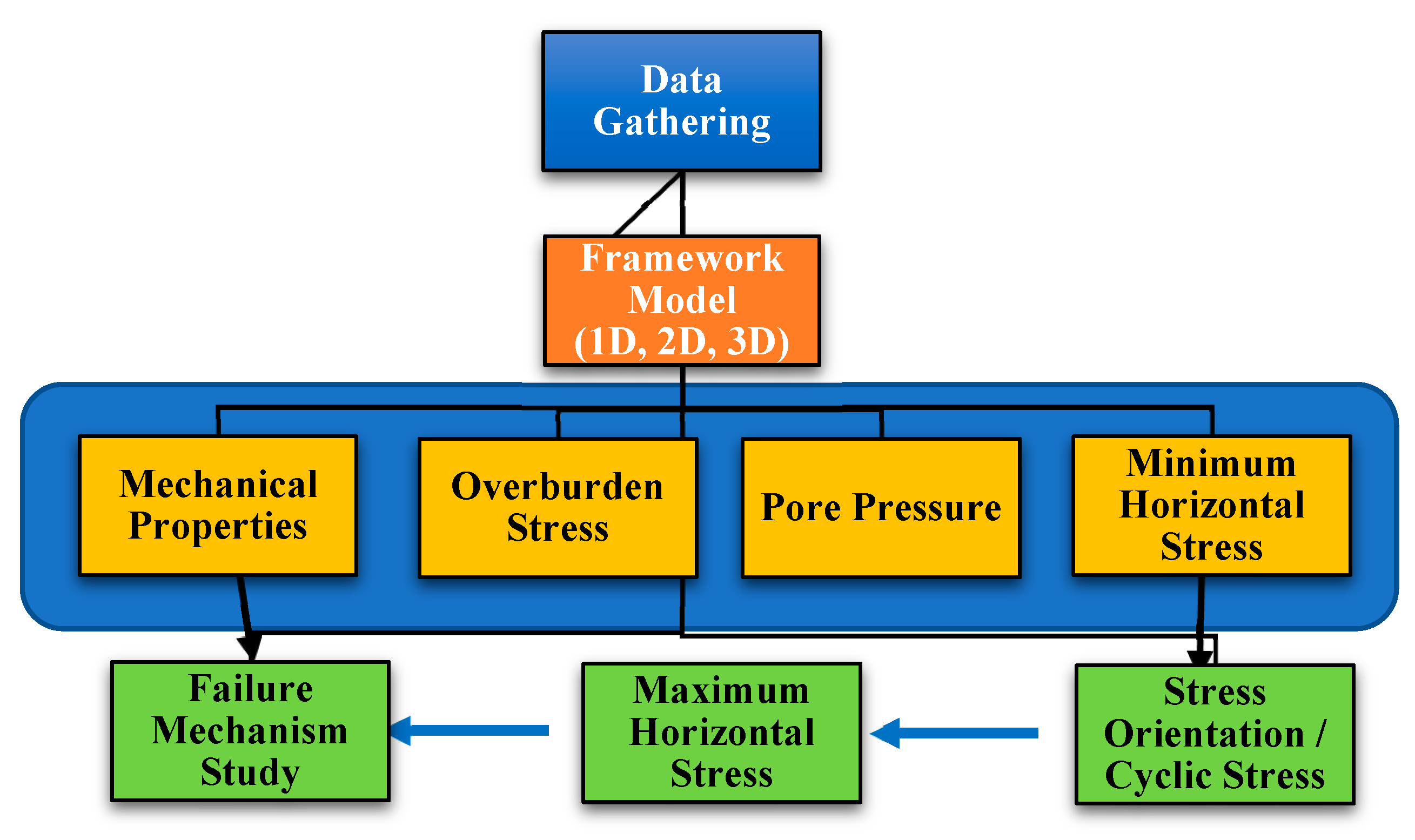

3. Geomechanical Connsiderations:

The geomechanical factors that primarily influence subsurface hydrogen storage include inject and production rates, wellbore shape, rock tensile strength, and the presence of fractures or faults (Taofik H. Nassan, 2025). Geomechanical modeling examines the impacts of geomechanics, such as the potential for reservoir fractures, the stability of wellbores and cap rocks, and the reactivation of faults. The ongoing processes of gas input and withdrawal in hydrogen storage affect the effective stress due to variations in pore pressure, thereby jeopardizing the integrity of both the reservoir and the caprock. When hydrogen is repeatedly supplied and withdrawn, the pressure inside the reservoir varies. These pressure shifts might cause existing fissures or weak places in the rock to reopen, increasing the risk of leaks and gas loss (Kwamena Opoku Duartey, 2025). To determine how effectively a reservoir can manage this, consider how the rock reacts to stress. That includes understanding its strength, how far it can bend without breaking, and how it responds to various stresses. This type of knowledge is critical for ensuring the storage site’s stability and safety throughout hydrogen activities.

Figure 4, illustration explaining the basics of geomechanical studies.

3.1. Stress Distribution and Reservoir Integrity:

Especially in unconventional reservoirs such shale formations and depleted reservoirs, the viability of underground storage depends on the evaluation of stress distribution and reservoir integrity. Mechanical stability, permeability variations, and general integrity of containment are strongly influenced by the interaction of in-situ forces with the reservoir rock. Three main stressors define the stress situation inside a reservoir most importantly. The weight of the rock strata above determines vertical stress (σv). Tectonic forces together with the surrounding geological setting produce the maximum horizontal stress (σH). Determination of hydraulic fracturing behavior and fluid flow depends critically on the minimum horizontal stress (σh). The balance of these stresses determines the ability of a reservoir to safely store gases like hydrogen or hydrocarbons, therefore reducing the possibility for leakage or structural damage (Stefan Bachu, 2007).

When fluid input, withdrawal, or geomechanical disturbances change the stress distribution, reservoir rock fractures and causes rock failure that results in: Induced fractures raise permeability, but they also run a danger of accidental leaking. Shear failure results from applied stresses exceeding the intrinsic strength of the rock, therefore compromising structural integrity. Caprock integrity failure can result from the overburden rock losing its capacity to seal, therefore enabling trapped gas to move to shallower strata or perhaps escape to the surface.

Reservoir integrity depends on considerations for mechanical and hydraulic parameters being stable throughout storage operations. Geomechanical modeling is the simulation of stress changes brought on by injection and depletion cycles. Seismic monitoring is the identification of microseismic occurrences indicating cracks brought on by stress. Evaluating caprock’s sealing capability with an eye on its potential to stop fluid migration from the underlying formations. Especially in avoiding injection pressures from exceeding the fracture gradient, pressure management is absolutely vital.

3.2. Fracture Behavior and Containment Risks:

Gases include hydrogen, natural gas, and CO₂ are stored underground; complex geomechanical mechanisms control their stability and confinement inside geological formations. The behavior of fractures, hazards related to containment, and the impact of cyclic loading on the stability of the storage system are essential elements determining the feasibility and safety of underground gas storage. The recognized hazards include probable declines in rock strength, ground subsidence or uplift, impaired well integrity, continuous hydrogen leaking, caprock seal efficacy lost, and seismic activity resulting from fault reactivation (Kwamena Opoku Duartey 1, 2025).

By changing permeability, gas movement, and general confinement of stored gases, fractures in subsurface rocks can significantly impact subterranean storage. Natural geological events spanning millions of years or human operations including hydraulic fracturing and gas injection can also cause fractures (Selena Baldana*, 2024). Different elements affect the formation and distribution of fractures: mechanical characteristics of the rock, current stress conditions, and fluid pressure applied during gas storage operations.

The injection of gas into a subsurface reservoir leads to an increase in pressure within the formation, which may result in the widening of pre-existing fractures or the formation of new fractures. This can improve the rock’s permeability, facilitating gas movement, which can be advantageous in certain scenarios. Nonetheless, excessive fracturing may lead to significant containment challenges by establishing routes for gas to migrate into unintended formations or potentially reach the surface. This is especially important for hydrogen storage, given that hydrogen molecules are smaller than those of methane or CO₂, which makes them more susceptible to diffusive leakage through microfractures. Studies of fracture behavior give great attention to the integrity of the caprock, which serves as the primary barrier preventing trapped gasses from rising. Should the caprock show pre-existing flaws or endure notable pressure variations, its capacity to seal might be weakened, therefore allowing probable gas escape. Moreover, some fractured formations might experience shear failure, causing rock layers to slide along a fault line and hence compromise storage security (Jonny Rutqvist, 2015). In regions with tectonic activity, the possibility of seismic events caused by fluid injection might aggravate containment issues, therefore emphasizing the need of careful geomechanical study before the choice of a storage site.

Comprehensive reservoir characterization is therefore required for the identification of fracture networks, assessment of caprock integrity, and prediction of fracture behavior under different storage circumstances, thereby addressing these difficulties. More knowledge of the evolution of pressure-induced cracks over time is made possible by advanced geomechanical modeling approaches including microseismic monitoring and finite element simulations. By carefully controlling injection pressures and closely observing fracture development, operators may maximize gas storage and protect reservoir sustainability and safety over time.

3.3. Cyclic Loading Effects and Storage Stability:

Geomechanical changes can be modeled more precisely to ensure reservoir integrity throughout UHS operations. During underground hydrogen storage, injection and withdrawal cycles cause reservoir pore pressure and temperature to vary, which can introduce significant risks during and after operations. Because both depleted reservoirs and salt caverns rely on wells for hydrogen injection and withdrawal, maintaining wellbore integrity is essential to prevent hydrogen leakage and ensure the safety and efficiency of the storage system (Kwamena Opoku Duartey 1, 2025). In underground gas storage systems, cyclic loading, the repetitive injection and evacuation of gas causes alternate stress and strain on the reservoir rock. The mechanical stability of the storage development can be much influenced by these cycles, therefore causing reservoir compaction, changes in permeability, and structural collapse over time. Cyclic loading, the repetitive injection and removal of gas that results from underground gas storage activities stresses and strains the reservoir rock alternately. The mechanical stability of the storage formation can be greatly altered by these cycles, therefore causing reservoir compaction, changes in permeability, and perhaps structural failure over time.

While withdrawal results in decompression and contraction, higher pressure during gas injection causes the rock to softly expand. Particularly in strata with high clay content or weakly cemented grains, constant cycles of expansion and contraction might compromise rock structural integrity. The fatigue impact might consolidate microcracks into bigger fractures over time, thereby altering the porosity and permeability of the storage development. Under extreme conditions, constant cyclic loading can cause permanent rock deformation, hence reducing storage efficiency and the effectiveness of following injections.

One major obstacle with cyclic loading is how it affects caprock integrity. The caprock acts as a barrier preventing gas migration; yet, constant pressurization might cause stress variations compromising its capacity to seal sufficiently. In rocks marked by naturally occurring fractures, these stress variations might progressively widen already present cracks, increasing the gas leakage risk. Cystic loading may cause fault reactivation in the presence of discontinuities such as faults in the caprock, therefore enabling the evacuation of trapped gasses into the formations above. Apart from mechanical aspects, cyclic stress significantly influences the hydraulic features of the reservoir. Variations in pore pressure and rock compaction cause permeability variations with every injection cycle. Permeability hysteresis is a phenomena whereby, following each withdrawal cycle, permeability does not entirely revert to its natural condition (Kyung Won Chang, 2025, Kishan Ramesh Kumar, 2023). This can lead to declining gas deliverability over time, therefore influencing the efficiency of storage operations.

Perfect storage stability under cyclic loading circumstances depends on careful reservoir management. To lower unexpected pressure variations that can affect the stability of the rock formation, operators must adjust injection and withdrawal rates. Early warning of reservoir strain or fault movement is much aided by geomechanical monitoring, which combines microseismic surveys with pressure sensors. Moreover, by means of core samples from possible storage locations, laboratory studies on cyclic stress on rock behavior in a controlled setting might provide crucial new perspectives. The results of cyclic loading studies have major ramifications for many worldwide subsurface storage projects. For example, salt caverns used for storing hydrogen are known to handle repeated stress quite well, mainly because they can naturally seal up small cracks over time. On the other hand, depleted oil and gas reservoirs—often reused for storing methane or hydrogen—can experience slow changes in how easily fluids move through them after several injection and withdrawal cycles (Kyung Won Chang, 2025). In a similar vein, observing CO₂ storage sites is essential for comprehending the impact of repeated pressure fluctuations on the caprock and determining if the injected gas remains securely contained. Through the integration of geomechanical analysis, real-time monitoring, and intelligent operational strategies, one can effectively address the impacts of these pressure cycles. This contributes to the stability and efficiency of underground storage systems for extended periods.

Table 3: Comparison of Natural gas, CO2 and H2 Storage perpective in geomechanics (Kishan Ramesh Kumar, 2023).

4. Geochemical Considerations:

Hydrogen’s reactivity can produce dangerous gasses that can compromise the wellbore, soil, and atmosphere. Geochemical interactions among reservoir fluids, cushion gas, hydrogen gas, and reservoir minerals may occur during UHS. By means of conversion into hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and methane (CH4), the processes cause hydrogen to be depleted. The geochemical reactions taking on in UHS might cause minerals to dissolve or precipitate, hence altering permeability and porosity. This modification could cause structural collapse or defects in the integrity of the cap rock (Shree Om Bade, 2024). Geochemical processes include both biotic and abiotic interactions among a spectrum of reactions. The abiotic processes especially entail the interaction of non-living molecules such hydrogen (Saeed & Jadhawar, 2024), oil, gas, brine, rock minerals, and so on.

Figure 5, depitcts interactions between hydrogen and geological minerals.

4.1. Hydrogen-Mineral Interactions:

Evaluation of the feasibility and safety of subterranean hydrogen storage depends on interactions between hydrogen and geological materials. The interactions could compromise the efficiency of hydrogen containment (Zaid Jangda, 1, 2023) or the integrity of storage reservoirs. Geochemical reactivity of hydrogen with sandstone formations has been investigated recently. The results imply that abiotic geochemical events in sandstone reservoirs have minimal probability of causing hydrogen loss or degradation of reservoir integrity. This suggests that formations of sandstone might be appropriate for subsurface hydrogen storage (Aliakbar Hassanpouryouzband*, 2022).

The presence of clay minerals in sandstone significantly influences hydrogen-sandstone geochemistry. Investigations into the influence of clay on hydrogen interactions in specific conditions revealed that the concentration of clay plays a crucial role in these interactions following extended exposure. Understanding the long-term behavior of hydrogen in these geological conditions requires a comprehensive awareness of its role.

Studies on the interactions between basalt, hydrogen, and water under geo-storage conditions have demonstrated that basaltic minerals exhibit minimal reactivity to hydrogen-water injections. The noted low reactivity suggests that basalt formations may serve as suitable candidates for hydrogen storage, offering a promising alternative to traditional sedimentary reservoirs (Ahmed Al-Yaseri*, 2023). Investigations have been conducted on the interactions of hydrogen with particular minerals, such as kaolinite, muscovite, and α-quartz, utilizing ab-initio methods. The results of these investigations reveal that hydrogen exhibits minimal interactions through van der Waals forces with these minerals, implying that under typical storage conditions, hydrogen is improbable to participate in chemical reactions with them. The results of these investigations show that the possible hydrogen storage capacity of a geological formation depends much on its mineralogical makeup. While those defined by inert mineralogy, such as particular sandstones and basalts seem more ideal for keeping hydrogen integrity over extended times, formations abounding in reactive minerals might provide challenges due of probable geochemical interactions. One may improve the safety and effectiveness of subsurface hydrogen storage systems by means of careful choice of storage sites marked by favorable mineral compositions and a complete awareness of the interactions between hydrogen and reservoir minerals.

4.2. Adsorption, Diffusion and Wettability Mechanisms:

The mechanics of adsorption, diffusion, and wettability are critical for maximizing subsurface hydrogen storage. These activities have a substantial impact on the efficiency and safety of hydrogen confinement in geological formations.

4.2.1. Adsorption Mechanism:

The process of hydrogen adsorption on mineral surfaces significantly impacts storage capacity and retention dynamics. Physisorption, characterized by the influence of weak van der Waals forces, functions as the primary mechanism for hydrogen’s interaction with earth minerals. Studies show that hydrogen molecules attach to mineral surfaces, potentially enhancing the effectiveness of subsurface hydrogen storage (Hesham Abdulelah, 2023). The presence of minerals like kaolinite in clay-rich formations can greatly influence hydrogen adsorption behavior. Investigations indicate that hydrogen molecules have the capacity to adsorb within the slit-like pores of kaolinite, thereby affecting the overall storage mechanisms in these porous media (Zhenxiao Shang, 2024).

4.2.2. Diffusion and Wettability Mechanisms:

The movement of hydrogen through geological formations is crucial for evaluating leakage risks and understanding transport dynamics in storage reservoirs. Molecular dynamics simulations indicate that hydrogen self-diffusion coefficients rise with temperature in different mineral substrates, such as calcite, hematite, and quartz. The dependence of temperature highlights the significance of reservoir conditions in forecasting hydrogen mobility (Zheng, Germann, & Gross, 2024).

In the context of hydrogen storage, the idea of wettability—that which describes the predisposition of a fluid to stick to a solid surface when additional immiscible fluids are present—is fundamental. Hydrogen trapping, migration, and possible leakage paths are strongly influenced by the wettability properties of reservoir rocks. Research in molecular dynamics have revealed that the wettability of quartz may be influenced by its surface chemistry and pressure conditions, therefore influencing hydrogen storage efficiency (Mehana, 2024). Moreover, investigations on the wetting preferences of silica surfaces have provided important new perspectives on fluid displacement mechanisms during hydrogen injection. The findings emphasize the importance of comprehending mineral-fluid interactions to maintain the integrity and functionality of hydrogen storage systems (Ghasemi, 2024). The mechanisms of adsorption, diffusion, and wettability are crucial for the effective design and management of subsurface hydrogen storage facilities. It is essential to meticulously evaluate factors like mineral composition, temperature, pressure, and surface chemistry to enhance storage capacity and reduce the risks linked to hydrogen migration or leakage. Ongoing investigation in these domains will improve our capacity to forecast and manage hydrogen dynamics within geological formations, thus facilitating the advancement of secure and effective energy storage options.

4.3. Microbial and Bio-Chemical Reactions:

Hydrogen has the potential to induce embrittlement in the auxiliary components of rock caverns, including compressors, pipes, and steel linings. Identifying significant shortcomings at each site is essential, especially regarding hydrogen utilization via homoacetogenesis, sulfate reduction, and methanogenesis (Kwamena Opoku Duartey 1, 2025). Subsurface microorganisms have the potential to interact with stored hydrogen, resulting in a range of outcomes that could influence both storage efficiency and the integrity of the reservoir (Rana Al Homoud, 2025). In subsurface environments, specific microorganisms harness hydrogen as a source of energy. The consumption of microbes can lead to a decrease in stored hydrogen, consequently diminishing the efficiency of UHS operations. For instance, hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria may break down hydrogen, therefore reducing it within the storage reservoir. One of the main problems with UHS is sulfate-reducing bacteria producing hydrogen sulfide (H₂S). Among the various risks involved in the manufacturing of H₂S include toxicity, possible infrastructure damage, and the possibility of polluting stored hydrogen. The honesty of these systems could compromise the financial viability and safety of hydrogen storage projects (Nicole Dopffel, 2023). For UHS, iron-rich strata offer a more appropriate choice as they suggest that the current storage facilities in rock cavernues might need changes. Steering clear of rocks like sulfide, carbonate, or sulfate is advised.

Initial results indicated that within a pH range of 6–7.5 sulfate reducers, homoacetogens, methanogens, and iron (III) reducing bacteria flourish. These bacteria thrive under salinity levels less than 60, less than 100, and less than 40 g/L−1 in turn. Whereas iron (III) reducing bacteria thrive at 0–30 ◦C, sulfate reducers and homoacetogens flourish at 20–30 ◦C, methanogens like 30–40 ◦C (Dopffel, Jansen, & Gerritse, 2021). The variations in these interactions are influenced by the type of geological storage, with depleted hydrocarbon reservoirs and saline aquifers exhibiting a higher susceptibility to these effects compared to salt caverns. The study emphasizes the need of microbial activity; yet, it does not provide quantitative information about the consequences of higher H2 levels in saline and alkaline environments (Shree Om Bade, 2024).

For example, hydrogen may be metabolized by oxidizing hydrogen-consuming bacteria, hence reducing the storage reservoir. An key issue for UHS is how sulfate-reducing bacteria generate hydrogen sulfide (H₂S). H₂S generates several hazards, including toxicity, probable facility corrosion, and the possibility of contaminating stored hydrogen. The dependability of these procedures might endanger the financial feasibility and safety of hydrogen storage systems (Nicole Dopffel, 2023). Iron-rich layers present a more suitable substitute for UHS as they imply that the present storage sites in rock caverns would need changes. One should steer clear of rocks with sulfide, carbonate, or sulfate.

Methanogenic archaea have the capability to transform hydrogen and carbon dioxide into methane, a process referred to as methanogenesis. This biochemical reaction not only causes hydrogen loss but also leads to the production of methane, which may be undesirable in the context of hydrogen storage. The presence of methane introduces challenges in the extraction and purity of the stored hydrogen. The activity of microorganisms can result in the development of biofilms in the porous structures of storage reservoirs. Biofilms can obstruct pore spaces, which in turn reduces the permeability of the reservoir. The decrease in permeability may impede the rates of hydrogen injection and withdrawal, thereby influencing the overall efficiency of the storage process (Qi Gao, 2024). A thorough understanding of subsurface microbial ecology and biochemical processes is essential to grasp the interactions between microorganisms and stored hydrogen. It is essential to address these microbial and biochemical reactions for the effective execution of UHS projects.

5. Storage Injectivity and Withdrawal Efficiency:

The effectiveness of underground hydrogen storage is mainly influenced by two key aspects: the injectivity of the storage site and the efficiency of hydrogen retrieval. The efficacy of hydrogen injection and extraction from underground reservoirs is influenced by these factors, which in turn determines the feasibility of large-scale hydrogen storage (Fünfschilling, 2023).

Storage injectivity is related to the efficiency of injecting hydrogen into a subterranean reservoir while guaranteeing maintained regulated pressure conditions. Reservoir permeability, pore throat diameters, fluid properties, and formation pressure mostly determine injectivity. Because their linked pore networks enable efficient hydrogen transport, high permeability formations like salt caverns and depleted gas reservoirs show better injectivity. Restricted pore connectivity and capillary pressures that hinder hydrogen migration cause the injectivity to be often greatly reduced in low permeability formations like as shales or tight sandstones (Carden, 2022.). One must give much thought to the integrity of the wellbored. Either poor well design, damaged casings, or cement degradation can cause hydrogen leaks during injection. Furthermore explaining the drop in injectivity during numerous injection cycles might be chemical reaction degradation, fine migration, or gas-induced cracks in the formation. Advanced stimulation methods frequently employed include hydraulic fracturing, acidizing, and pressure cycling, which are designed to enhance permeability and, consequently, injectability.

On the other hand, withdrawal efficiency refers to how effectively stored hydrogen can be extracted from the reservoir for various applications. The management of reservoir pressure, mechanisms of hydrogen diffusion and retention, as well as capillary trapping, all influence the efficiency of extraction. Minimizing constraints on gas transport within reservoirs characterized by elevated porosity and permeability typically leads to enhanced extraction efficiency. Irregular flow patterns, such as gas fingering, can lead to ineffective extraction in fractured formations, resulting in the entrapment of residual hydrogen within the rock matrix (Berta, 2021).

5.1. Hydrogen Movement in Low-Permeability Formations:

The existing literature indicates that the intrinsic permeability of intact halite (pure rock salt) ranges from 10⁻20 to 10⁻22 m² (Ph. Cosenza, 1999), demonstrating a notable sealing capacity, particularly for hydrogen. However, the presence of impurities can elevate salt permeability to a magnitude of 10−16 m2. Calculations of permeability for hydrogen storage in salt caverns suggest that diffusion serves as the main mechanism in salt rocks exhibiting a permeability of under roughly 3 × 10⁻21 m². The high level of permeability significantly minimizes the losses of hydrogen over time. Their observations indicate that the primary regions of potential leakage are the cavern roof and the wellbore cement (Taofik H. Nassan *, 2024). Shale gas is a form of unconventional natural gas that is generated and stored within high-carbon shale and its interlayer. Unlike conventional gas reservoirs, shale generally demonstrates permeability levels that align with the Nadarcy range. The permeability of the shale matrix ranges from 10−9 to 10−5 mD, while in the naturally occurring fractures, it spans from 10−3 to 10−1 mD. The typical porosity of shale reservoirs varies between 3% and 8.4% (Mingqiang Wei, 2023).

The subsurface storage of hydrogen (H₂) in formations characterized by low permeability involves intricate interactions between geological attributes and fluid dynamics. The formations being analyzed, such as tight sandstones, shales, and specific carbonate reservoirs, demonstrate limited permeability, which constrains the efficiency of hydrogen injection, storage, and withdrawal operations. The behavior of hydrogen in these reservoirs is influenced by various transport mechanisms, such as Darcy and non-Darcy flow, molecular diffusion, adsorption, and capillary trapping. Grasping these mechanisms is essential for assessing storage viability and enhancing operational strategies. The storage of hydrogen in porous formations is greatly influenced by the inherent characteristics of the reservoir, such as porosity, permeability, wettability, and geomechanical stability. The small molecular size of hydrogen results in a higher diffusion rate compared to other gases like methane, which may elevate leakage risks and complicate the maintenance of long-term storage efficiency (Heinemann, 2021).

Figure 6 illustrates the storage of hydrogen within a reservoir characterized by low permeability.

5.1.1. Mechanisms Governing Hydrogen Flow:

A variety of transport and retention processes shapes hydrogen’s behaviour in low permeability rocks. The efficiency of hydrogen storage and recovery is highly influenced by the methods used. The basic element controlling hydrogen transport in porous materials is the dynamics controlled by pressure gradients. Darcy’s law exactly explains fluid flow in highly permeable rocks. In low permeable reservoirs, when pore throats are much narrower, Non-Darcy Flow becomes clearly important. In these cases, Knudsen diffusion is quite important as gas molecules interact more often with the pore walls than with one another, therefore changing their transport properties (Fünfschilling, 2023).. Furthermore, molecular diffusion influences the movement of hydrogen in tightly packed arrangements. The high diffusion coefficient of hydrogen molecules depends critically on their small size, which also helps them to flow efficiently via nanoscale pore structures. This function becomes somewhat crucial in situations where diffusive transport predominates over advective flow and permeability is rather low. Fick’s diffusion depends much on concentration gradients, which also affect the hydrogen diffusing mechanism. Fick’s diffusion also influences surface diffusion, in which molecules travel the surfaces of mineral grains inside the rock matrix.

The adsorption and retention inside the pore network is a crucial determinant of hydrogen transport. Van der Waals forces cause some of the gas molecules in injected hydrogen into a reservoir to stick to mineral surfaces. This procedure is quite important in shales and clay-rich formations as adsorption can greatly reduce the free hydrogen availability for extraction. The extent of adsorption is influenced by the mineral composition of the reservoir, with clay-rich deposits exhibiting greater hydrogen retention compared to those predominantly composed of quartz (Heinemann, 2021). The efficiency of hydrogen injection and withdrawal is fundamentally influenced by the interplay between capillarity, wettability, and adsorption. Capillary forces can trap hydrogen within pore spaces in a formation largely water-saturated, therefore limiting its flow. The conditions of wettability play a crucial role in determining the interaction of hydrogen with reservoir fluids and mineral surfaces, which in turn impacts its relative permeability and overall storage efficiency (Fünfschilling, 2023). Moreover, comprehending the impact of geomechanical factors on flow is essential for assessing reservoir performance throughout its entire lifespan. The processes of hydrogen injection and withdrawal result in fluctuations in reservoir pressure, which may influence the structural integrity of the rock. Low-permeability formations demonstrate a notable sensitivity to stress, suggesting that changes in pressure can lead to the closure of existing fractures, which in turn reduces permeability. Conversely, high-pressure injection may create new microfractures, potentially increasing permeability and enhancing injectivity. However, these changes necessitate careful supervision to avoid unintentional leakage paths that might compromise storage security (Amin, 2022).

5.1.2. Exploring the Challenges of Hydrogen Storage in Low-Permeability Reservoirs:

Low permeability formations for hydrogen storage provide various technological issues that have to be addressed if effective storage and retrieval are to be made possible. One main problem found is insufficient injectivity. The limited permeability of the rock requires higher pressure gradients for hydrogen injection at reasonable flow rates, thereby maybe causing fractures and compromising reservoir integrity. This can improve permeability by creating fissures or, occasionally, cause compaction and a drop-in permeability (Sheinemann, 2021). Important problems needing addressed include retention and entrapment. Among other things, trapping of hydrogen molecules, capillary pressures, adhesion to mineral surfaces, and molecular migration into nanopores can all lower effective withdrawal rates. This phenomenon raises operating expenses and reduces storage efficiency.(Fünfschilling, 2023).

Hydrogen increases the likelihood of leakage in low-permeability materials due to its relatively small molecular size. Even the smallest microfractures and overlooked defects that can serve as conduits may lead to gradual hydrogen leakage. Thorough reservoir characterization and continuous monitoring are essential for mitigating these risks. Another factor being examined is geochemical interactions, as they could potentially undermine the storage integrity of the formation. Hydrogen’s interaction with minerals such as carbonates and clays can lead to the formation of secondary minerals, alterations in porosity, and potential reductions in permeability. The interactions enhance microbial activity, leading subterranean organisms to metabolize hydrogen (Amin, 2022), which results in increased gas depletion and biofilm growth that could obstruct pore spaces.

5.2. Difficulties in Injection and Retrieval Cycles:

A significant challenge to withdrawal efficiency is the retention of hydrogen caused by both adsorption and diffusion processes. The adsorption of hydrogen molecules onto mineral surfaces or their migration into smaller pore spaces within porous media may account for the observed decrease in gas recovery volume during successive withdrawal cycles. The relevance of this problem rises dramatically when capillary forces vary between rock strata in different forms, trapping of hydrogen results. Furthermore, affecting the efficiency of withdrawal is the consequences of cyclic loading. Using cycles of injection and withdrawal will help to produce induced microfractures, lower permeability, or change in pore structure deformation by altering the stress conditions in the reservoir. Among the notable challenges include changes in permeability, phase behavior, erosion of formations, and interactions between rocks and fluids (Heinemann, 2021).

The primary challenges faced during hydrogen injection relate to formation damage, specifically the reduction in permeability resulting from changes in reservoir conditions. The damage to formation results from a range of processes. The migration of small particles and the resulting obstruction of pore throats within the reservoir can lead to a decrease in injectivity over several cycles. This presents significant challenges for sandstone formations characterized by elevated clay content (Amin, 2022). Hydrogen-Induced Mineral Changes: Significant effects of precipitation or dissolution may arise from the interactions between hydrogen and specific minerals. In formations abundant in carbonate, the dissolution process may enhance porosity while concurrently influencing the integrity of the rock matrix, thereby prompting inquiries about stability (Fünfschilling, 2023). Hydrogen effectively substitutes water in the injection process; however, capillary forces may lead to residual water being trapped in the pore spaces, thereby decreasing the effective pore volume available for gas storage (Heinemann, 2021).

5.2.1. Pressure and Stress Changes Affecting Injectivity:

The introduction of hydrogen into subterranean formations leads to notable fluctuations in pressure, potentially modifying the stress conditions within the reservoir. The alterations in stress levels can yield both beneficial and detrimental outcomes. Decrease in Permeability As a result of heightened sensitivity to stress: Numerous low-permeability reservoirs exhibit sensitivity to stress, indicating that elevated pressure during injection can lead to rock compression, which in turn decreases permeability and complicates future hydrogen extraction (Fünfschilling, 2023).Induced Fracturing and Potential Leakage: The process of high-pressure injection can generate new fractures, potentially enhancing injectivity while simultaneously posing risks of hydrogen leakage via unintended pathways (Amin, 2022). Rock Compaction and Creep: In salt caverns and soft rock formations, extended hydrogen storage may result in rock compaction over time, which can decrease available storage capacity and modify flow dynamics during retrieval (Heinemann, 2021).

5.2.2. Retrieval Challenges and Loss of Hydrogen:

Once hydrogen is stored, the efficient retrieval process becomes essential for maintaining economic viability. Nonetheless, multiple mechanisms contribute to hydrogen loss or reduced withdrawal efficiency. Adsorption and Retention in Reservoir Rock: The adherence of hydrogen to mineral surfaces occurs through van der Waals forces, which subsequently diminishes the volume of free gas that can be extracted. Reduced retrieval efficiency (Amin, 2022) results from clearly higher adsorption rates shown by shale and clay-rich strata. Particularly in water-wet reservoirs, capillary trapping and residual saturation point to some of the injected hydrogen perhaps becoming immobilized due to capillary forces. The presence of gas saturation restricts the quantity of hydrogen that can be harvested (Heinemann, 2021). Defensive Losses in Low-Permeability Formations: The diminutive molecular size of hydrogen facilitates its infiltration into microfractures and nanopores, complicating recovery efforts. The influence is particularly evident in formations characterized by notable micro-porosity (Fünfschilling, 2023).

6. Experimental and Modeling Methodologies:

The interactions among geochemical, geomechanical, and hydrodynamic factors play a significant role in UHS, a complex process that impacts the injection, storage, and generation of hydrogen gas. Anticipating UHS performance necessitates an understanding of these pathways. Geochemical factors are crucial for understanding and replicating the various processes associated with underground hydrogen storage (UHS). The models should accurately represent equilibrium processes along with precipitation and mineral dissolution reactions. The rates of these kinetic reactions are influenced by several factors, including temperature, pressure, and salinity (Hassanpouryouzband, et al., 2022).

6.1. Experimental Investigations and Computational Modeling:

Understanding hydrogen storage behavior in subterranean reservoirs necessitates both numerical simulations and laboratory experiments. These approaches aid in assessing critical parameters such as geomechanical stability, geochemical interactions, injectivity, and withdrawal efficiency. Combining computational and experimental methodologies yields valuable information for improving the long-term viability of subterranean hydrogen storage (UHS). To imitate the subsurface environment, laboratory studies are conducted under controlled conditions (Dutta, 2021). The evaluation of rock-hydrogen interactions is based on core flooding tests, permeability testing, and geochemical reactions. The primary experimental techniques are:

Core Flooding Experiments: The experiments involve relative permeability, flow dynamics, and trapping mechanisms being analyzed by injecting hydrogen into rock cores. Their results provide important new perspectives on the behavior of hydrogen as it replaces other fluids and passes through low permeable formations (Katz M. &., 2022).

Geochemical Interaction Studies: The interactions of hydrogen with minerals present in reservoir rocks can lead to alterations in both porosity and permeability. The study of the mechanisms involved in mineral dissolution, precipitation, and microbial activity that can influence storage integrity (Ji, 2021) is experimental.

Hydrogen Sorption and Diffusion Tests: Investigating adsorption and diffusion is essential for evaluating hydrogen retention within porous materials. The conducted experiments are instrumental in assessing possible losses resulting from capillary trapping or chemical reactions (Wang, 2020).

Mechanical Integrity Tests: Cycles of repeated injection and withdrawal can lead to variations in stress, which may impact the stability of rock formations. Triaxial compression tests are employed to investigate rock deformation, fracture propagation, and fatigue under cyclic hydrogen injection conditions (Zhang, 2023).

Numerical simulations provide prediction models evaluating long-term performance in several operating environments, therefore enhancing laboratory research by means of these models. Mathematical frameworks intended for geomechanical, geochemical, and fluid flow are used in construction of the models.

Reservoir Simulation Models: The models provide simulations of hydrogen migration, pressure accumulation, and potential leakage hazards within subsurface reservoirs. Forecasting storage efficiency (Z Zhou, 2021) with real-world data gleaned from lab tests and field observations.

Geomechanical Modeling: Coupled hydro-mechanical models evaluate stress changes in the storage reservoir, therefore predicting probable fracture, fault reactivation, and subsidence brought about by the cyclic hydrogen injection and withdrawal.

Reactive Transport Models: This set of simulations combines fluid dynamics with geochemical processes, allowing for the forecasting of mineral dissolution, precipitation, and the impact of microbial activity on hydrogen stability.

Multiphase Flow Simulations: One of the subterranean reservoirs is hydrogen; it is a multiphase fluid coexisting with water or others gasses. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) models are fundamental instruments for exploring hydrogen distribution, phase behavior, and the effects of capillary entrapment.

Integrating laboratory findings with numerical simulations improves the precision of models for underground hydrogen storage. Data gathered from experiments serve to fine-tune simulation parameters, thereby minimizing uncertainties in forecasting long-term storage performance. The combination of both methods enhances decision-making in site selection, operational strategies, and risk assessment (Kwamena Opoku Duartey 1, 2025).

Table 4 presents a comparison of the strengths and limitations associated with laboratory studies and numerical simulations (Dutta, 2021; Tarkowski R., 2019; Kruck, 2013).

Software tools such Eclipse, DuMux, CMG-GEM, TOUGH, and COMSOL are routinely used in underground hydrogen storage to replicate hydrogen flow and apply fluid flow concepts. Oil and gas reservoir modeling makes extensive use of SLB’s Eclipse program (100 and 300); although Eclipse 100 uses a black oil model, CMG-GEM and Eclipse 300 employ compositional models to control phase behavior variations in fluid compositions. Perfect for hydrogen and cushion gas injection, TOUGH, created to replicate gas injection and reactive transport (Kwamena Opoku Duartey 1, 2025) is outstanding.

6.2. Field-Scale Applications and Case Studies:

The shift towards extensive underground hydrogen storage is essential for incorporating hydrogen into energy frameworks and maintaining supply reliability. Field-scale applications offer crucial understanding of practical challenges and viability, enhancing laboratory experiments and numerical models. A number of case studies from around the globe have illustrated the capabilities of different geological formations, including salt caverns, depleted hydrocarbon reservoirs, and deep saline aquifers, for extensive hydrogen storage solutions. These applications evaluate essential parameters, such as injectivity, withdrawal efficiency, containment integrity, and long-term stability.

6.2.1. Existing Field-Scale Hydrogen Storage Projects:

Salt caverns are the most typically employed construction form for hydrogen storage with its higher containment integrity and reduced leak risk. For instance, the Texas Gulf Coast Salt Dome Storage has been running since the 1970s, keeping significant volumes of hydrogen for use in the petrochemical and refining industries especially (Lord, 2014). In a similar vein, the Teesside hydrogen storage site in the UK has been utilized by industrial entities for many years, employing salt caverns for the efficient storage and distribution of hydrogen (Caglayan, 2020). On the other hand, for hydrogen storage depleted gas reservoirs and saline aquifers stay in the pilot state. Launched by Gasunie, the HyStock project in the Netherlands looks at issues related with geochemical interactions, microbiological activity, and the impacts of cyclic injection and withdrawal in a depleted gas reservoir (Reitenbach, 2015).

6.2.2. Obstacles in Practical Implementations:

Although laboratory experiments and simulations establish essential understanding, practical applications encounter further intricacies. Significant obstacles consist of:

Hydrogen Containment and Losses: In contrast to natural gas, hydrogen possesses a smaller molecular size, which heightens the potential for diffusion and leakage through caprock and fault structures (Kruck, 2013).

Geochemical and Microbial Reactions: Hydrogen could interact with minerals and natural bacteria in deep reservoirs, leading to hydrogen consumption and raising questions about reservoir integrity (Tarkowski R., 2019).

Cyclic Injection and Withdrawal Effects: Variations in pressure conditions during major activities might affect the mechanical integrity of the storage site, therefore influencing the permeability and maybe causing induced seismicity (Heinemann, 2021).

Numerous extensive initiatives currently in progress are undergoing examination across Asia, North America, and Europe. Germany’s HyPSTER project is exploring hydrogen storage in salt caverns under practical conditions, while the H21 Leeds City Gate Project in the UK is examining the potential of utilizing natural gas infrastructure for hydrogen storage. These projects provide important new perspectives on UHS’s ongoing performance and financial viability. Understanding field-scale applications via case studies will help us to progress the development of safe, efficient, and scalable storage solutions given the growing relevance of hydrogen in the energy transition. To increase operating efficiency, future research should focus on improving reservoir characterization, resolving hydrogen loss processes, and improving injection and withdrawal techniques.

7. Challenges and Knowledge Gaps:

The security and stability of long-term storage rely heavily on the comprehensive enhancement of existing research gaps in underground hydrogen storage, particularly concerning geomechanical impacts, geochemical interactions, and the implementation of real-time leakage detection systems. As underground hydrogen storage expands to support a hydrogen-based electricity system, it is essential to prioritize long-term stability and safety. The storage of hydrogen in underground formations involves distinct challenges, including chemical interactions, the need to maintain the integrity of confinement, and the risk of leaks occurring over prolonged durations. Maintaining the integrity of the caprock, which serves as a barrier to inhibit hydrogen migration, is a vital issue in the realm of long-term hydrogen storage. (a) The integrity of caprock and the potential for leakages are critical considerations. Due to hydrogen’s minuscule molecular size, it can navigate through existing cracks and porous formations, thereby heightening the risk of leaks (Heinemann, 2021). Additionally, the stress alterations induced by cyclic injection and withdrawal could lead to microfractures in the storage formation, consequently compromising containment as time progresses (Tarkowski R., 2019).

(b) Geochemical and microbial reactions indicate that hydrogen can interact with reservoir minerals, leading to alterations in rock properties and possibly resulting in structural weakening. Interactions with iron-bearing minerals can lead to the generation of hydrogen sulfide (H₂S), a corrosive gas that poses a risk to wellbore integrity (Reitenbach et al., 2015). Moreover, the role of microorganisms in storage reservoirs can lead to the utilization of hydrogen, converting it into methane or other byproducts, potentially reducing the efficiency of storage operations (Sherwood, 2017). (c) Induced Seismicity and Geomechanical Alterations; The ongoing cycle of hydrogen injection and withdrawal over prolonged durations leads to the persistent pressurization and depressurization of the storage formation. Changes in geomechanical stress brought about by variations in pressure may set off seismic events in geologically sensitive areas (Kruck, 2013). The evolution of induced seismicity could compromise infrastructure and affect public perceptions of large-scale hydrogen storage facilities.

(d) Pressure and gas flow Tracking; Identification of anomalies relies on constant downhole sensor pressure monitoring; tracer gases including helium enable to follow hydrogen transport (Caglayan, 2020).(e) Seismic and geophysical surveillance; microseismic monitoring identifies stress-induced fractures, whereas 4D seismic imaging offers insights into reservoir changes over time (Booth, 2021). (f) Geochemical & Microbial Activity Analysis: Systematic gas sampling and chromatography-based analysis facilitate the monitoring of gas composition variations, enabling the identification of potential reactions that could impact storage integrity (Tarkowski R., 2019).

8. Future Research Directions:

Exploring novel sealing materials for wellbores, enhancing reservoir evaluation techniques, and developing microbial-resistant storage environments concentrates efforts on augmenting the reliability of long-term hydrogen storage. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into monitoring systems significantly improves predictive modeling and data analysis, allowing a more proactive approach to risk management. As global underground hydrogen storage proliferates, it is imperative to address long-term hazards through advanced monitoring systems to ensure its viability as a sustainable energy storage solution.

Especially for low-permeability formations, future research should focus on improving reservoir characterisation techniques to get a better knowledge of hydrogen migration and confinement behavior. Advanced sealing materials with more resistance to hydrogen diffusion will help to maintain storage system integrity and stop leakage. Moreover required for correct forecast of stress fluctuations and hazard mitigation including produced seismicity and caprock collapse are advances in geomechanical modeling and real-time monitoring systems. Identification of possible geochemical changes affecting reservoir stability depends on an analysis of hydrogen-mineral interactions. Moreover, preventing unintentional hydrogen consumption and gas pollution depends on an awareness of the function of subsurface microbial activity.

Ultimately, it is essential to broaden pilot-scale field tests and case studies to confirm the results obtained from laboratory experiments and numerical simulations. Partnerships among academic institutions, industry players, and government bodies will be essential in developing standardized regulations and best practices for the safe storage of hydrogen at a commercial level. The exploration of these avenues will play a crucial role in advancing the worldwide shift to hydrogen-based energy systems.

9. Conclusions:

This review has explored the geomechanical and geochemical factors influencing underground hydrogen storage (UHS), emphasizing its viability, challenges, and future advancements. The study examined stress distribution, fracture behavior, containment risks, adsorption-diffusion mechanisms, microbial interactions, and cyclic loading effects, all of which critically impact storage integrity and efficiency.The findings of our study emphasized the importance of low-permeability formations, which provide advantages for long-term containment despite presenting challenges due to restricted flow. Furthermore, advancements in numerical simulations and laboratory investigations have enhanced our understanding of hydrogen dynamics in subsurface environments, thereby refining prediction models for injection and withdrawal processes.

This review provides valuable insights by examining storage injectivity and retrieval efficiency. This work highlights the limitations in hydrogen mobility and suggests solutions by employing advanced well stimulation techniques and optimizing reservoir selection. Furthermore, field-scale applications and case studies provide insights into practical implementation, offering valuable lessons for large-scale hydrogen storage initiatives.The continuous monitoring of risks, including hydrogen leakage and caprock integrity, underscores the necessity for robust surveillance technologies and regulatory frameworks.

The future of UHS will be shaped by the evolution of innovative storage techniques targeted on enhancing injectivity, maximizing withdrawal efficiency, and maintaining long-term stability. Recent studies on hybrid storage systems—which combine built caverns with porous media storage—show a possible route for maximum operating flexibility. Moreover, the improvement of monitoring precision, the enabling of predictive analysis of hydrogen flow, stress fluctuations, and possible failure sites depends on the development of artificial intelligence systems for reservoir management.

This review is unique as it provides a whole knowledge of subsurface hydrogen storage by combining geomechanical and geochemical points of view. This work distinguishes from other studies by combining reservoir mechanics with chemical interactions, therefore providing a whole perspective required for the evolution of safe and efficient storage solutions. Emphasizing emergent research areas such hydrogen-mineral interactions, microbial impacts, and the use of machine learning in reservoir models, this study lays a basis for future development in the topic.. As the world moves to hydrogen-based solutions, constant research and technical developments will be necessary for full realization of subterranean hydrogen storage potential. Cooperation among educational institutions, businesses, and regulatory authorities will help to influence future developments in sustainable, safe, and scalable hydrogen storage systems thereby enabling their seamless integration into the future energy grid.

References

- Ahmed Al-Yaseri*, A. F. Basalt–Hydrogen–Water Interactions at Geo-Storage Conditions. ACS Publications 2023, 15138–15152. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed Al-Yaseri, *. A.-Q. Subsurface Hydrogen Storage in Limestone Rocks: Evaluation of Geochemical Reactions and Gas Generation Potential. Energy & Fuels 2024, 9923–9932.

- Aliakbar Hassanpouryouzband*, K. A. Geological Hydrogen Storage: Geochemical Reactivity of Hydrogen with Sandstone Reservoirs. ACS Energy Letters 2022, 2203–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, M. S. Hydrogen flow dynamics in tight formations: Experimental and numerical insights. Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Berta, M. R. Geomechanical effects on cyclic hydrogen injection and withdrawal in underground storage. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2021, 18972–18986. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, M. G. Geological containment and monitoring strategies for underground hydrogen storage. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2021, 17310–17325. [Google Scholar]

- Caglayan, D. G. Technical potential of salt caverns for hydrogen storage in Europe. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2020, 6793–6805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carden, P. &. Physical, chemical, and engineering challenges of underground hydrogen storage. Applied Energy 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dopffel, N. , Jansen, S., & Gerritse, J. Microbial Side Effects of Underground Hydrogen Storage—Knowledge Gaps, Risks and Opportunities for Successful Implementation. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2021, 8594–8606. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, T. P. Underground hydrogen storage: Influence of geomechanics and geochemistry on containment integrity. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2021, 29708–29726. [Google Scholar]

- Elie Bechara*1, T. G. Effect of Hydrogen Exposure on Shale Reservoir Properties and Evaluation of Hydrogen Storage Possibility in Depleted Unconventional Formations. Unconventional Resources Technology Conference 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fünfschilling, L. S. Assessing injectivity and withdrawal performance in hydrogen storage reservoirs. Energy & Fuels 2023, 37, 1045–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi, M. A. Wetting Preference of Silica Surfaces in the Context of Underground Hydrogen Storage: A Molecular Dynamics Perspective. Langmuir 2024, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Giacomo Rivolta1*, M. M. Evaluating the Impact of Biochemical Reactions on H2 Storage in Depleted Gas Fields. SPE Journal 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hassanpouryouzband, A. , Adie, K., Cowen, T., Thaysen, E., Heinemann, N., Butler, I.,... Edlmann, K. Geological Hydrogen Storage: Geochemical Reactivity of Hydrogen with Sandstone Reservoirs. ACS Energy Letter 2022, 2405–2410. [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann, N. B. Hydrogen storage in porous subsurface formations: A geomechanical perspective. Geomechanics for Energy and the Environment 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hesham Abdulelah, A. K. Hydrogen physisorption in earth-minerals: Insights for hydrogen subsurface storage. Journal of Energy Storage 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein*, A. A.-H.-M. Hydrogen Underground Storage in Silica-Clay Shales: Experimental and Density Functional Theory Investigation. ACS Publications 2023, 8, 45906–45913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y. L. Experimental study of geochemical interactions affecting hydrogen storage in porous media. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2021, 17392–17404. [Google Scholar]

- Jonny Rutqvist, A. P. Modeling of fault activation and seismicity by injection directly into a fault zone associated with hydraulic fracturing of shale-gas reservoirs. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2015, 377–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D. , & Tek, M. Storage of Natural Gas in Saline Aquifers. Water Resources Research 1970, 6, 1515–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, M. &. Hydrogen injection in sedimentary formations: Laboratory insights and field implications. Energy & Fuels 2022, 8925–8938. [Google Scholar]

- Kishan Ramesh Kumar, H. H. Comprehensive review of geomechanics of underground hydrogen storage in depleted reservoirs and salt caverns. Journal of Energy Storage 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruck, O. C. (2013). Assessment of the potential, performance and costs of underground hydrogen storage in depleted oil and gas reservoirs and saline aquifers. HyUnder Project Report. Retrieved from https://www.hyunder.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/D3.1_Assessment-of-the-potential-performance-and-costs-of-underground-storages.

- Kwamena Opoku Duartey 1, 2. Kwamena Opoku Duartey 1, 2.,. Underground Hydrogen Storage: Transforming Subsurface Science into Sustainable Energy Solutions. Energies 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kyung Won Chang, T. S. Cyclic loading–unloading impacts on geomechanical stability of multiple salt caverns for underground hydrogen storage. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, A. S. Geologic storage of hydrogen: Scaling up to meet city transportation demands. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2014, 15570–15582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehana, R. Z. Molecular Insights into the Impact of Surface Chemistry and Pressure on Quartz Wettability: Resolving Discrepancies for Hydrogen Geo-storage. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2024, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Mingqiang Wei, S. W. Blasingame decline theory for hydrogen storage capacity estimation in shale gas reservoirs. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 13189–13201. [Google Scholar]

- Nicole Dopffel, B. A.-S. Microbiology of underground hydrogen storage. Hydrogen Storage and Production 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Muthukumar a, *. A. Review on large-scale hydrogen storage systems for better sustainability. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 33223–33259.

- Ph. Cosenza, M. G.-S. In situ rock salt permeability measurement for long term safety assessment of storage. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences 1999, 509–526. [Google Scholar]

- Qi Gao, J. L. Phenomenal study of microbial impact on hydrogen storage in aquifers: A coupled multiphysics modelling. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 79, 883–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]