Introduction

Rabies, a zoonotic disease documented for over 4000 years, remains a serious public health threat in over 150 countries and regions worldwide. Children under the age of 15 account for 40% of cases [

1]. Once clinical symptoms emerge, rabies exhibits an almost 100% case fatality rate, with no effective treatment approved even in the 21st century, with an annual mortality rate of 59,000 (95% CI, 25,000-159,000) [

2].

Rabies is vaccine-preventable. The active immune response induced by the rabies vaccine typically merges within approximately 7 to 10 days and reaches a peak neutralizing antibody level around Day 28 [

3]. As early as 1955, it was observed that neutralizing antibody, by the combination of anti-rabies serum and vaccine which was produced early in and throughout the treatment period, was more effective in rabies prevention after severe exposure than the vaccine alone [

4].

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) proposed a post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) schedule in 2008, which included wound cleansing, infiltration of wounds with immunoglobulin (not vaccinated previously), and administration of rabies vaccines [

5]. In 2018 and 2024, the WHO further recommended monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) as an alternative to immunoglobulin [

6,

7]. Prompt neutralization of the virus in the wound area through passive antibody is crucial within the first 7 days, before the vaccine-induced active immune response has been fully developed. Notably, the neutralizing antibody levels through immunoglobulin within the 7-day window are generally lower than 0.5 IU/mL, whereas the WHO recommends a minimum level of 0.5 IU/ml as seroprotective against rabies [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Despite the effectiveness of timely and thorough PEP in preventing rabies, fatal breakthrough infection cases have still been reported globally [

14,

15,

16,

17]. These cases include one American case of PEP immune failure, one Canadian case of PEP immune unresponsiveness, both published in 2023; and 122 cases of fatal PEP breakthrough infections published between January 1, 1980 and June 1, 2022. Among them, some cases developed clinical symptoms of rabies as early as 5-9 days after the bite. Similarly, in China, a 3-year-old child from Anyang City, Henan Province, was bitten by a dog with multiple wounds. Despite prompt PEP, the child unfortunately passed away on May 9, 2024, only 18 days after the bite [

18]. Other PEP failure cases in China include a 32-year-old female in 2017 [

19,

20], a 6-year-old boy in 2017 [

21], and another 6-year-old boy in 2018 [

22]. These deaths have drawn significant media attention and public concerns regarding the potential increased risk of PEP failure.

The goal of this review was to propose the optimal solution for preventing PEP failure. In this review, we introduced a concept of “circulating antibody”, which is induced early with a high concentration; we also discussed its role in PEP, and its potential for preventing future PEP failures in the context of rabies management.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

We conducted a comprehensive search in PubMed, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), and reviewed references from relevant articles using the search terms “rabies”, “antibody”, “post-exposure prophylaxis” or “breakthrough infection” in titles or abstracts. The search covered the period from the inception of the databases to Jul 08, 2024. We included articles written both in English and Chinese. Additionally, we visited the WHO homepage to include relevant recommendations and guidance from 1990 to 2024. Given that PEP failure cases were not published in academic journal, we also included relevant news. For any disagreements regarding the inclusion of articles, final decisions were made through discussion between Chuanlin Wang, Zhenggang Zhu and Wenwu Yin.

Review

Epidemiology and Global Disease Burden

The estimated annual human mortality caused by canine rabies in Africa and Asia is 55,000 deaths (90% confidence interval (CI): 24,000-93,000), with a mortality rate of 1.38 per 100,000 (90% CI: 0.60-2.33) and an annual cost of US

$ 583.5 million (90% CI: 540.1-626.3). Without PEP, the estimated number of deaths would increase to 327,160 (95% CI: 166,904-525,427) [

23]. Another research estimated an annual number of death was 59,000 (95% CI: 25,000-159,000) and an annual cost was US

$8.6 billion (95% CI: 2.9-21.5) [

2]. The latest global burden report in 2023, covering 204 countries, estimated an annual death toll of 13,743.44 (95% CI: 6,019.13-17,938.53) with top 5 countries of India, Nigeria, Pakistan, Ethiopia, and China. The age group of teenagers (under 14 years old) had the highest incidence. Notably, although the global total incidence rate has dropped from 45.99/10,000,000 (95% UI: 17.74-75.23) to 18.45/10,000,000 (95% UI: 7.89-28.18) over the past 30 years, the incidence rate for those over 70 years old has remained almost the same at 1,100 cases per year, indicating that both teenagers and elderly people over 70 years old are more likely to be attacked due to reduced self-defense ability [

24].

Pathogenesis

The clinical stages of rabies are: incubation, prodrome, acute neurological signs, coma, and death [

25]. The most efficient route of transmission of the rabies virus (RABV) is through the saliva of an infected animal, typically via a bite. The virus infects the motor endplates in the muscle, binds to the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at the neuromuscular junction, and promotes neural cell adhesion, ultimately spreading to the brain (rarely through blood circulation) [

26].

Passive Immunity in PEP

Rabies is uniformly fetal once symptoms develop, and the only hope for rabies prevention lies in effective PEP. Passive immunity in PEP, demonstrable early, is more effective in rabies prevention after severe exposure than vaccine alone, as it offers immediate protection while vaccine-induced active immune response takes 7 days or longer [

4]. However, animal-derived anti-rabies serum, primarily from horses, brought an unacceptably high incidence of side effects. For instance, Karliner et al. observed serum sickness in 16.3% of 526 severely exposed patients treated with horse serum in a single center between 1959 and 1964, with a higher incidence of 46.3% in the subgroup aged over 15 [

27]. In 1974, human rabies immune globulin (HRIG) produced by Cutter Laboratories was approved and gradually replaced horse serum in regions, such as the United States. At a dose of 20 IU/kg, interference with vaccine-induced neutralizing antibody levels is minimal [

28,

29].

However, rabies immunoglobulin derived from the blood plasma of horses or humans has several limitations relating to supply, cost, quality, shelf life, efficacy, and ethical concerns [

30].

Since 1990, the WHO has advocated for the development of mAb cocktail as an alternative of immunoglobulin, considering highly specific targets, closely controlled production, and easily monitored quality. The WHO also emphasized that cocktail, instead of single antibody, should be considered to avoid the risk of viral escape variants [

31]. After 26 years, in 2016, the first single-component monoclonal antibody Rabishhield (SII RMAb) was approved for use in India. In 2024, Zamerovimab and Mazorelvimab Injection (SYN023), the first cocktail therapy that met the WHO recommendations, was approved in China.

Up to now, passive immunity options, from the initial discovery to the practical application, became gradually enriched for clinician use, including rabies immunoglobulin (ERIG), human rabies immunoglobulin (HRIG) and monoclonal antibody cocktail therapies.

Circulating Antibody

The recommended local infiltration dose of HRIG is 20 IU/kg body weight. If calculated based on the 50kg body weight and 4,000mL blood volume, the circulating antibody level in the distal muscles would only be 0.25 IU/mL, which is far below the protective threshold of 0.5 IU/mL, observed in multiple clinical trials, with circulating antibody levels of 0.14-0.47 IU/mL during Day 0 - 7 [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. In 2018, WHO did not recommend the use of rabies immunoglobulin (RIG) at a site distant from the wound because of its limited benefits [

6].

PEP Failure, Non-Response, Fatal Breakthrough Infection, and Possible Attribution

Nicholson estimated that the failure rate of using modern rabies vaccines in developed countries is approximately 1/80,000, while 1/12,000-30,000 in developing countries [

32]. We searched PubMed by using the terms “((failure) or (fail) or (false breakthrough infection) or (non-response)) and (rabies [Title/Abstract]) and (post-exposure pathway [Title/Abstract])”, and 23 articles were identified. We also searched CNKI using terms “Rabies (Abstract)” and “Immunity Failure (Title)”, and 18 Chinese articles were identified. Chinese publications about PEP failure were mainly from 1989 to 2008, before the issuance of trial batch of rabies vaccine for human use in China in 2005.

Case 1: An 84-year-old male from the United States woke up from a bat bite on his right hand. Three days later, virus lab test was positive; and then, PEP, including HRIG and a full four-dose series of vaccine, was administered. Rabies symptoms appeared 5 months later, and the patient died 15 days thereafter. The autopsy specimens tested by the CDC confirmed rabies virus infection. No neutralizing antibodies were detected in the cerebrospinal fluid and blood samples through the rapid immunofluorescence focal inhibition test (RFFIT method). The PEP failure in this case is suspected to be due to an unrecognized immune dysfunction [

14].

Case 2: An 87-year-old male from Canada was bitten by a bat, received HRIG and three series of rabies vaccine. The patient had no detectable rabies antibodies after the first two intramuscular (IM) series, and only achieved a level of 1.28 IU/mL after the third intradermal (ID) series. The PEP failure in this case is suspected to be his aging [

15].

Case 3-124: In a review of 122 fatal rabies breakthrough infection cases, 54% of cases involved severe wounds to the head, neck, or face, significantly higher than the historic data of 2-6%; 30% of cases involved multiple bites, higher than the historic data of 3-18%. The median time from exposure to symptom onset was 20 days (9-61 days), shorter than the historic data of 1-3 months. Although most patients (77%) sought medical attention within 2 days, rabies illness onset occurred so rapid that half of the patients (62/122) could not complete the full vaccine series, suggesting rapid transportation of rabies virus to the central nervous system (CNS) [

16].

Eighteen Chinese articles reported that PEP failure cases that developed symptoms as short as 5 days after a bite, and as late as 396 days. Most cases were involved multiple bites and severe wounds to the head or neck.

Guidelines for Clinical Trial Design

Since 1990, the WHO has advocated mAb for the development of mAb cocktails as an alternative to RIG [

31]. Subsequent meetings, including consultation meetings held in Geneva in 2002, the second (2012) and the third (2017) expert consultations, consistently recommended developing mAb cocktails which contain monoclonal antibodies targeting two or more non-overlapping antigenic epitopes of the rabies virus envelope glycoprotein G [

33,

34]. In 2021 and 2022, the FDA and China CDE released guidance to assist sponsors in the development of mAb cocktails as an alternative to RIG, as the passive immunization component of PEP for the prevention of rabies when administered immediately after a bite. Currently, two mAb cocktails have been approved globally. Zamerovimab and Mazorelvimab Injection was developed in accordance with the following guidance.

In July 2021, the FDA released a technical guidance, which provided specific recommendations for the clinical trial design. The superiority trials of mAb cocktails versus placebo are unacceptable, and adequately powered non-inferiority trials of mAb cocktails versus RIG are logistically infeasible. A multicenter, double-blind, randomized controlled trial of the mAb cocktail plus vaccine versus RIG and plus vaccine is recommended, to enroll at least 750 subjects with WHO category III exposure in rabies-endemic countries and follow them for at least one year. The endpoint is to demonstrate a rabies-free survival rate >99.5%, to support the use of mAb cocktails as a second-line indication (when HRIG is not available). Other efficacy endpoints are rabies virus neutralizing antibody (RVNA) levels up to 7 days post-exposure, before RVNAs produced by the vaccine become predominant, and vaccine interference of RVNA levels at Day 14 or after five half-lives. To transition from a second-line to a first-line indication, additional clinical trialss are required to include data from at least 6,000 subjects receiving mAb cocktails after WHO category III rabies virus exposure in rabies-endemic countries [

35].

In January 2022, China CDE released technical guidance, which required similar principles as those from the FDA with additional recommendations for future research in patients with immune suppression, concomitant HIV infections, hepatic decompensation, and renal insufficiency [

36].

Approved and Under Developing mAb (Cocktails)

There are four approved mAbs (including cocktail therapies) globally (

Table 1), two under clinical development, and four in pre-clinical stage (

Table 2).

In December 2016, the world's first rabies mAb product, Rabishield

® (SII RMab/17C7, humanized IgG) was approved in India, and was recommended by the WHO as an alternative to HRIG in 2018. In September 2019, Twinrab (RabiMabs/docaravimab and miromavimab, murine mAb cocktail), the first mAb cocktail, was approved in India. Subsequently, Ormutivimab (NM57, recombinant humanized mAb) was in China in January 2022 (adults) and May 2024 (child). In June 2024, Zamerovimab and Mazorelvimab Injection (SYN023, zamerovimab/CTB011 and mazorelvimab/CTB012, humanized IgG1κ mAb cocktail), developed by Synermore Co., Ltd., was approved in China, representing the first WHO guideline-compliant humanized monoclonal antibody cocktail for rabies post-exposure prophylaxis. It specifically binds to non-overlapping antigen sites of rabies virus glycoprotein Ⅲ and G5, and effectively neutralize more than 15 contemporary clinical isolates of rabies viruses collected from China and 10 predominant strains in the USA [

37].

Immunoglobulin was measured in international units (IU), mainly considering that ERIG and HRIG are mixtures of multiple antibodies, differences in antibody components among different donors, and differences in different batches from the same donor. Therefore, a biological experimental method by comparing standard samples was used to determine the relative potency of HRIG/ERIG. Unlike immunoglobulins, mAb has a defined and stable molecular structure, allowing more accurate mass measurement and thus dosing in mg/kg is used [

38].

Early phase I and II trials of four approved mAbs all explored safety and efficacy data among different dose levels through dose escalation studies. Rabishield dose escalation explored 1 IU/kg, 3 IU/kg, 10 IU/kg, and 20 IU/kg [

8], and ultimately conducted phase II/III studies at a dose of 10 IU/kg [

9]. Twinrab explored doses up to 40 IU/kg [

39] and further observed the efficacy and safety between two dose levels, 20 IU/kg and 40 IU/kg in a phase III trial [

10]. Ormutivimab explored doses at 10, 20, and 40 IU/kg [

11,

40,

41]. The confirmatory Phase III study used 20 IU/kg [

42]. SYN023 explored doses at 0.3, 1.0, and 2.0 mg/kg [

43,

44,

45]. The Phase IIb and III studies used 0.3 mg/kg [

12,

13].

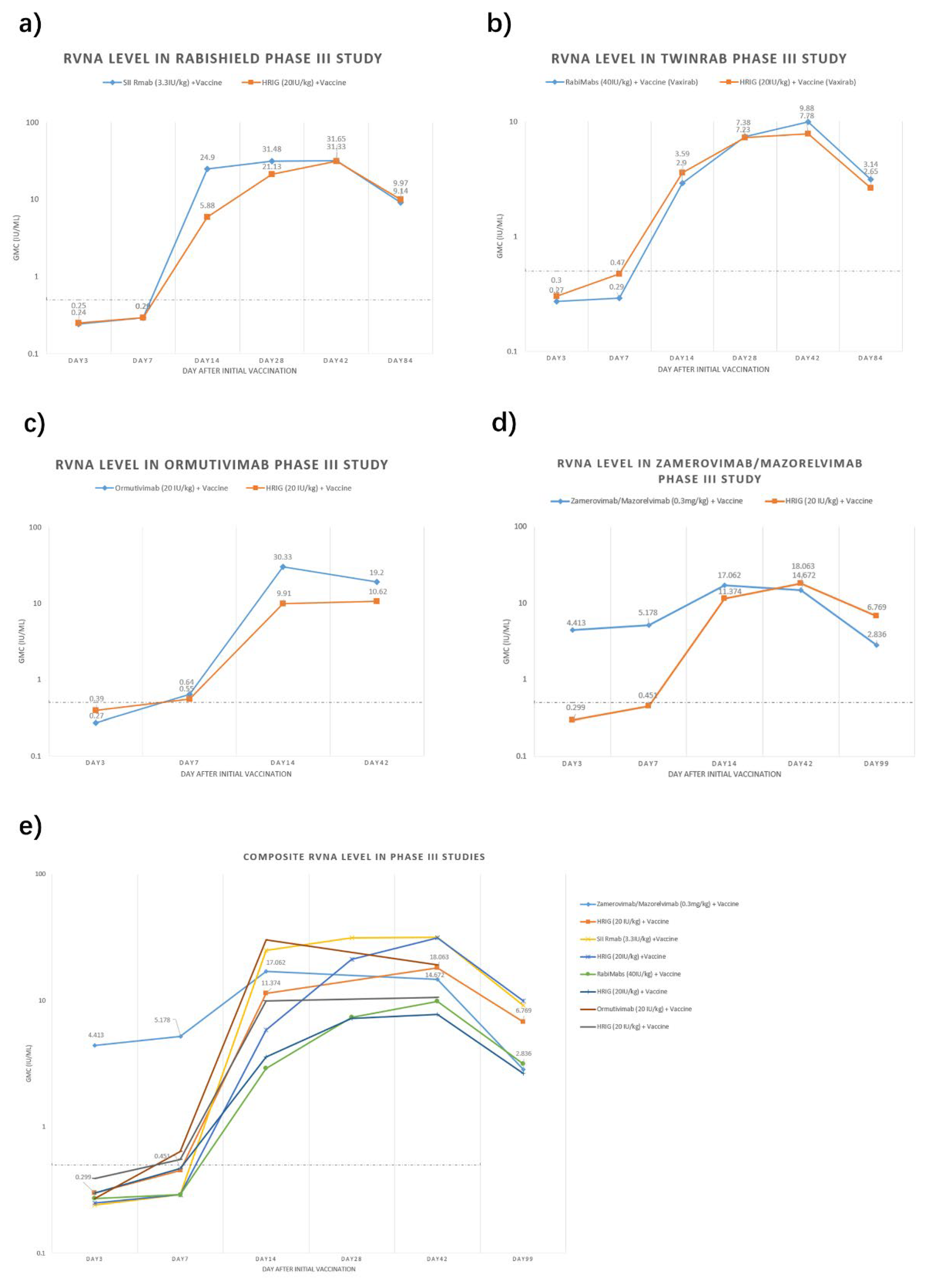

mAbs Rapidly Attain Higher Post-Exposure Circulating Antibody Levels

We have summarized the circulating antibody geometric mean concentration (GMC) from key Phase III registration studies of the four approved mAbs [

9,

10,

13,

42] (

Figure 1). Among them, three mAbs reported 3-month data (84 or 99 days) and Ormutivimab reported 42-day data only. Generally, RVNA level of HRIG + vaccine groups in each trial were low within 7 days (0.25-0.55 IU/mL), then gradually increased and peaked at Day 42. For mAb + vaccine groups, RVNA levels increased more rapidly and reached higher levels within the first 14 days. Notably, the Zamerovimab and Mazorelvimab Injection achieved remarkably high RVNA levels early post-administration, reaching 4.413 IU/mL by Day 3 and peaking at 17.062 IU/mL on Day 14. For the other three mAbs, the RVNA levels in the mAb groups were similarly low as those in the HRIG groups within 7 days post-administration. By Day 14, all mAb and HRIG groups demonstrated significantly increased RVNA titers, with the mAb groups consistently exceeding those of the HRIG controls. All mAb and HRIG groups sustaining protective titers (>0.5 IU/mL) through Day 99.

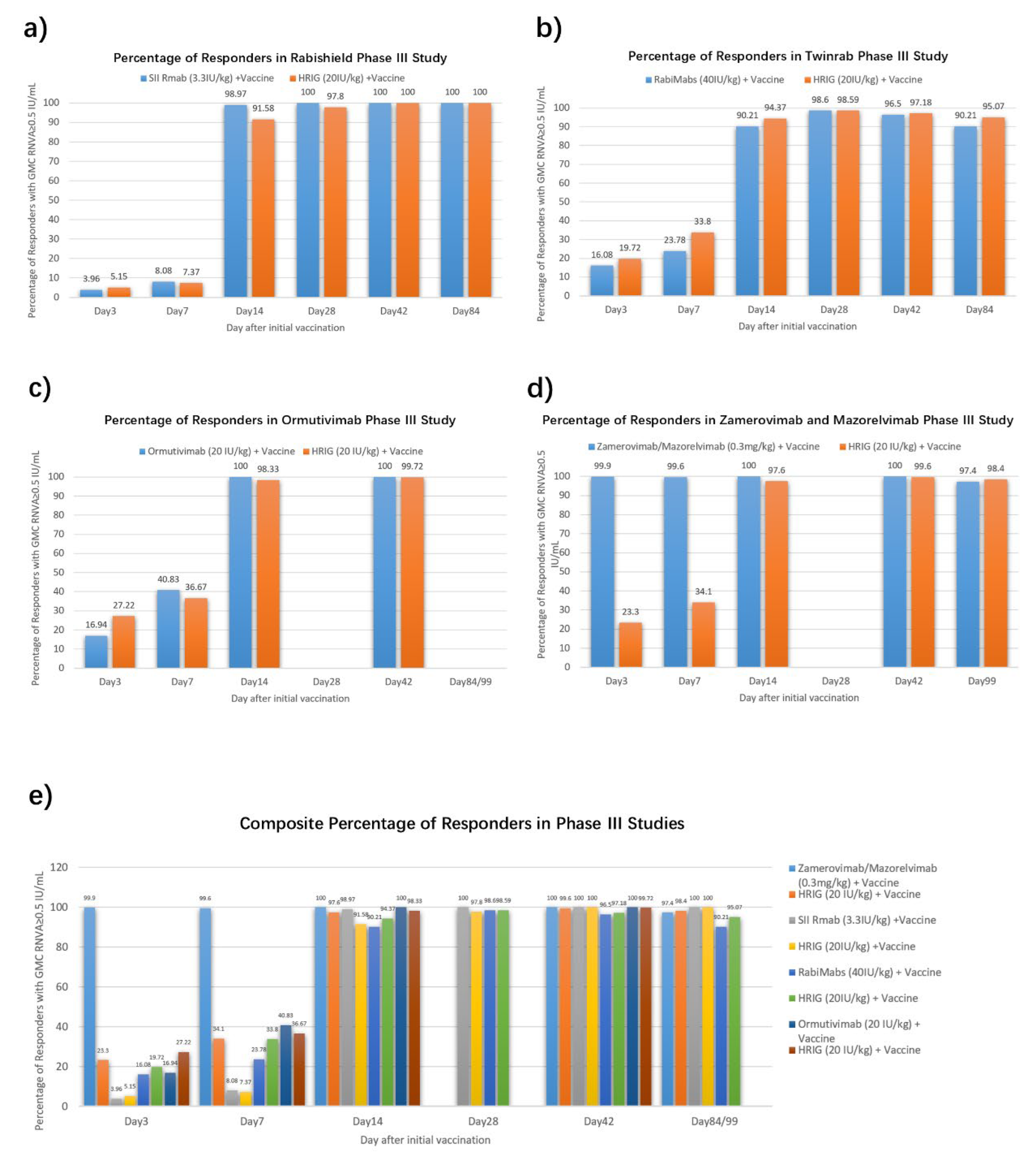

The positive rates of RVNA (identified as RVNA ≥0.5 IU/mL) in Phase III studies of four approved mAbs were also summarized [

9,

10,

13,

42] (

Figure 2). Low early-phase seroconversion (7.37%-36.67% at 7 days post-administration) was observed in HRIG + vaccine recipients, substantiating that HRIG + vaccine establish limited protective RVNA titers during the critical early phase. On Day 14, both HRIG and mAbs achieved positivity rate over 90%. It is noteworthy that Zamerovimab and Mazorelvimab Injection reached high positive rate (≥99% on Day 3 and Day 7), far higher than the other three mAbs (3.96%~16.94% at Day 3 and 8.08%~40.83% at Day 7), illustrating that Zamerovimab and Mazorelvimab Injection is capable to protect mostly in the early stage, before active protection produced by vaccine predominate.

Discussion

Vaccine doses and schedules for PEP have been recommended and decreased over time, from initially 90 days with 6 injections to 21 days with 4 doses. Circulating neutralizing antibody is induced to be seroprotective within 7-14 days after the first injection. Recently, a novel three-dose recombinant nanoparticle-based rabies G protein vaccine (Thrabis®), prepared by using Virus Like Particle technology (VLP), was developed in India to shorten PEP duration. However, a seroprotecting rate of 99.24% on Day 14 and 98.69% on Day 42 seems barely satisfactory for early protection in the first 14 days [

46,

47].

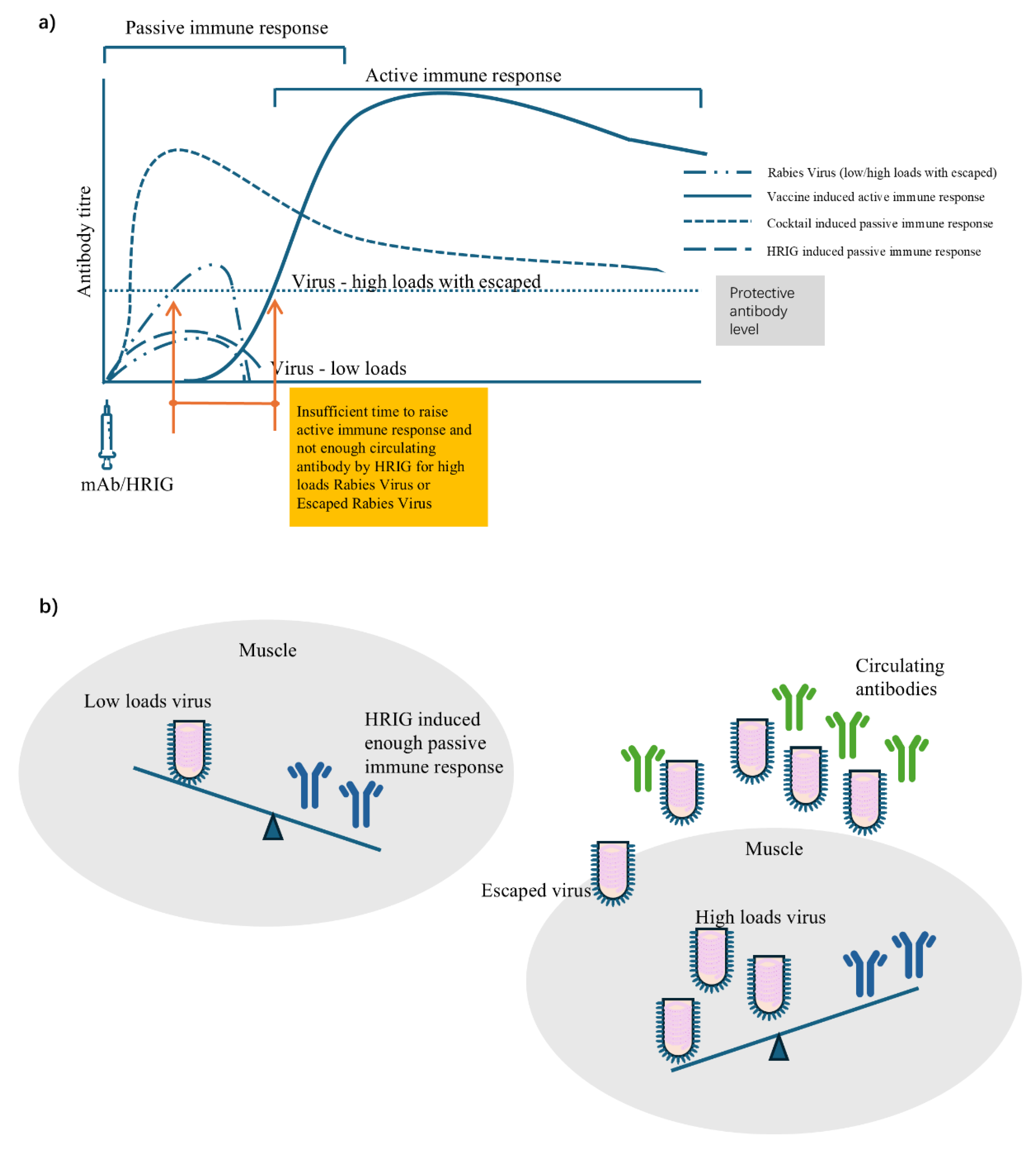

The circulating antibody cannot be early induced by vaccine active immunization before 7-14 days, and thus passive immunization is recommended to be administered into or around the wound site, ideally encircling and neutralizing the virus early. By using methylene blue solution for a visual infiltration effect, it was observed that a complete infiltration was difficult due to manual operation and special anatomy (eyelid) [

48]. Although methylene blue solution was used in Liu’s study to visualize the initial infiltration status after injection, it is likely that some virus may still escape, especially in cases of high viral loads from multiple, severe, deep bites and/or virus released by infected apoptotic neuron (

Figure 3). HRIG might be not sufficient to neutralize all viruses at the wound site, especially as some may enter the peripheral blood over time. In theory, HRIG (20IU/kg) can induce a circulating antibody of only 0.25 IU/mL (<0.5 IU/mL protective threshold), if calculated based on 50 kg body weight and 4,000 ml blood, which was further confirmed in trials of 0.14-0.47 IU/mL on Days 0-7 [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Low concentrated circulating antibodies induced by HRIG plus incompletely encircling virus and locally escaped virus cannot be ruled out for contributing PEP failures. Zhu explored to solve it by using high-dose HRIG (33.3 IU/kg) in combination with a vaccine and successfully prevented rabies in a four-year-old Chinese girl who was severely bitten by a confirmed rabid dog [

49]. The girl remains healthy 17 years after exposure. However, due to disadvantages of ERIG and HRIG as summarized in this review, the WHO has advocated for the development of mAbs (cocktails) as an alternative to RIG. Two of four approved antibodies, mAb Rabishield

® and cocktail Zamerovimab and Mazorelvimab Injection, have demonstrated a significantly earlier achievement of the rabies virus neutralizing antibody (RVNA) (≥ 0.5 IU/mL on Day 1-3) protective threshold, compared to 14 days for HRIG (≥ 0.5 IU/mL on Day 14) [

8,

9,

12,

13,

43,

44,

45]. As the first approved cocktail therapy in China, Zamerovimab and Mazorelvimab Injection not only acts more rapidly, but also induces a higher concentration of circulating antibodies. In Phase II trials, Zamerovimab and Mazorelvimab Injection quickly reached a higher concentration of circulating antibodies, 10 times higher than that of HRIG (1.32 vs 0.11 IU/mL) on Day 1 [

44,

45]. In IIb phase trials, the concentration of circulating antibodies for Zamerovimab and Mazorelvimab Injection was 23 times higher than that of HRIG (3.30 vs 0.14 IU/mL) on Day 3, and remained above the 0.5 IU/mL level for up to 99 days [

12]. In Phase III clinical trials, Zamerovimab and Mazorelvimab Injection reached a circulating antibody concentration 14 times higher than that of HRIG (4.413 vs 0.299 IU/mL) on Day 3, and remained above the 0.5 IU/mL level for up to 99 days [

13]. Based on these inspiring clinical data, Zamerovimab and Mazorelvimab Injection demonstrates superior performance in inducing high-concentration protective circulating antibodies as early as one day after administration. This capacity allows to neutralize most viruses and minimize escaped virus, a feat that neither vaccines nor HRIG can achieve alone.

PEP failure, non-response, and fatal breakthrough infections have been reported worldwide [

14,

15,

16,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Among them, high viral loads from multiple bites, severe wounds to the head, neck, or face, and incubation periods as short as 9 days are more frequent observed and significantly shorter than historic average data. Scholand had suggested adding a WHO exposure category IV for extremely severe exposures to improve the care of these high-risk patients and highlight the global health urgency of this neglected disease [

50].

In addition to incomplete infiltration and low-concentration circulating antibodies failing to neutralize escaped viruses, timely administration of PEP is also critical. Once clinical symptoms appear, it is rarely successful to avoid a fatal outcome. In a failure case in the US, the patient waited to receive HRIG and vaccine until positive lab virus test was issued, which was already 3 days after the exposure [

14]. The delay is a core practice violation, especially in high-risk population, which is undoubtedly an avoidable error. The 2018 WHO position file suggested that the first dose of rabies vaccine should be administered as soon as possible after exposure [

6].

Facing up to the global challenges of human aging, we need to increase attention on the older people over 70, as rabies incidence has remained unchanged over the past 30 year, despite a decrease in the whole population incidence [

24]. Most elderly individuals are accompanied by complex chronic comorbidities and immunological dysfunction, posing significant challenges for the immune response of PEP, as demonstrated in the two cases mentioned above [

14,

15]. Real-world studies from Serbia have shown that the elderly population in Serbia is a risk factor for low seropositivity after rabies vaccination, after 13 years of rabies vaccine inoculation experience according to WHO recommendations [

51]. Registration trials lack data generated from such elderly population and more real-world data are needed to observe the circulating antibodies induced by mAbs to optimize PEP procedures.

There are two limitations in this review. Although Phase III clinical trials cited were conducted in patients with suspected WHO category III rabies exposures, they lack laboratory virus data and thus it is not clear whether the biting animals were truly infected by rabies virus street strains. In addition, 40% of the rabies cases in the real world come from children, we look forward to more pediatric data.

Additionally, another two mAbs (GR801, CBB1) are currently under development. GR801 plans to enroll 1200 subjects in its Phase III study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of GR1801 + vaccine compared to HRIG + vaccine in subjects with suspected WHO category III exposure (NCT05846568, CTR20222502). CBB1 is under Phase I trials involving 152 healthy adult subjects to evaluate the safety and determine the optimal dosage. With more research and mAb development, we are looking forward to an improvement of passive immunization to provide higher antibody titer, earlier onset of circulating antibodies, and longer-lasting duration.

Conclusions

Early and high-concentration circulating antibodies are of utmost importance to prevent PEP failure, which cannot be well achieved by either vaccine or HRIG at the early stage. The development and approval of the first mAb cocktail product (Zamerovimab and Mazorelvimab Injection) that meets WHO recommendations for binding two or more non-overlapping antigenic epitopes on the envelope glycoprotein G of rabies virus, which has brought a better alternative to HRIG as passive component in PEP. Zamerovimab and Mazorelvimab Injection followed 2021 FDA guidance and conducted well designed clinical registration studies, the data shows that a higher concentration of protective circulating antibody level was achieved as early as Day 1, over 10 times higher than that of HRIG, and maintaining levels above 0.5 IU/mL for up to 99 days. For extremely severe cases, such as those involving high viral loads, the rapid passive protection offered by Zamerovimab and Mazorelvimab Injection is particularly needed. In addition to ongoing improvement in mAb/cocktail development to reduce mortality rates, broader societal involvement is crucial in addressing this neglected disease, further to finally solve this global health urgency as towards to WHO’s goal of “zero by 30”.

Authors’ contributions

Qingjun Chen, Li Cai,Xinjun Lvand Si Liu conducted literature searches, figures, data interpretation and writing. Cheng Liu, Jiayang Liu, Xiaoqiang Liu, Chuanlin Wang, Zhenggang Zhu and Wenwu Yin reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors had responsibility for submission decision with access to the final manuscript.

Declaration of interests

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Funding source is not involved.

References

- WHO. Rabies. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rabies.

- Hampson, K.; Coudeville, L.; Lembo, T.; Sambo, M.; Kieffer, A.; Attlan, M.; Barrat, J.; Blanton, J.D.; Briggs, D.J.; Cleaveland, S.; et al. Estimating the global burden of endemic canine rabies. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015, 9, e0003709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupprecht, C.E.; Briggs, D.; Brown, C.M.; Franka, R.; Katz, S.L.; Kerr, H.D.; Lett, S.; Levis, R.; Meltzer, M.I.; Schaffner, W.; et al. Evidence for a 4-dose vaccine schedule for human rabies post-exposure prophylaxis in previously non-vaccinated individuals. Vaccine 2009, 27, 7141–7148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habel, K.; Koprowski, H. Laboratory data supporting the clinical trial of anti-rabies serum in persons bitten by a rabid wolf. Bull World Health Organ 1955, 13, 773–779. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, S.E.; Rupprecht, C.E.; Fishbein, D.; Hanlon, C.A.; Lumlertdacha, B.; Guerra, M.; Meltzer, M.I.; Dhankhar, P.; Vaidya, S.A.; Jenkins, S.R.; et al. Human rabies prevention--United States, 2008: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep 2008, 57, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Health, O. Rabies vaccines: WHO position paper, April 2018 - Recommendations. Vaccine 2018, 36, 5500–5503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Protocol for a well-performed rabies post-exposure prophylaxis delivery: to read along with the decision trees 1- Wound risk assessment and 2 - PEP risk assessment. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/B09018.

- Gogtay, N.; Thatte, U.; Kshirsagar, N.; Leav, B.; Molrine, D.; Cheslock, P.; Kapre, S.V.; Kulkarni, P.S. Safety and pharmacokinetics of a human monoclonal antibody to rabies virus: a randomized, dose-escalation phase 1 study in adults. Vaccine 2012, 30, 7315–7320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogtay, N.J.; Munshi, R.; Ashwath Narayana, D.H.; Mahendra, B.J.; Kshirsagar, V.; Gunale, B.; Moore, S.; Cheslock, P.; Thaker, S.; Deshpande, S.; et al. Comparison of a Novel Human Rabies Monoclonal Antibody to Human Rabies Immunoglobulin for Postexposure Prophylaxis: A Phase 2/3, Randomized, Single-Blind, Noninferiority, Controlled Study. Clin Infect Dis 2018, 66, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansagra, K.; Parmar, D.; Mendiratta, S.K.; Patel, J.; Joshi, S.; Sharma, N.; Parihar, A.; Bhoge, S.; Patel, H.; Kalita, P.; et al. A Phase 3, Randomized, Open-label, Noninferiority Trial Evaluating Anti-Rabies Monoclonal Antibody Cocktail (TwinrabTM) Against Human Rabies Immunoglobulin (HRIG). Clin Infect Dis 2021, 73, e2722–e2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, Y.; Bai, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, J.; Yang, L.; Zhao, W.; Zhao, W.; Luo, F.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Neutralizing antibody activity, safety and immunogenicity of human anti-rabies virus monoclonal antibody (Ormutivimab) in Chinese healthy adults: A phase Ⅱb randomized, double-blind, parallel-controlled study. Vaccine 2022, 40, 6153–6162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiambao, B.P.; Payumo, R.A.; Roa, C.; Borja-Tabora, C.F.; Emmeline Montellano, M.; Reyes, M.R.L.; Zoleta-De Jesus, L.; Capeding, M.R.; Solimen, D.P.; Barez, M.Y.; et al. A phase 2b, Randomized, double blinded comparison of the safety and efficacy of the monoclonal antibody mixture SYN023 and human rabies immune globulin in patients exposed to rabies. Vaccine 2024, 42, 126018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- XQ, W.; YX, Z.; ZX, W. Effects of Zamerovimab / Mazorelvimab on the rabies virus neutralizing antibody level in the grade Ⅲ rabies post exposure subjects. Chinese J Exp Clin Virol 2024, 38, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Holzbauer, S.M.; Schrodt, C.A.; Prabhu, R.M.; Asch-Kendrick, R.J.; Ireland, M.; Klumb, C.; Firestone, M.J.; Liu, G.; Harry, K.; Ritter, J.M.; et al. Fatal Human Rabies Infection With Suspected Host-Mediated Failure of Post-Exposure Prophylaxis Following a Recognized Zoonotic Exposure-Minnesota, 2021. Clin Infect Dis 2023, 77, 1201–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, R.; Nguyen, C.; Taha, M.; Taylor, R.S. Older adults and non-response to rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: Challenges and approaches. Can Commun Dis Rep 2023, 49, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehouse, E.R.; Mandra, A.; Bonwitt, J.; Beasley, E.A.; Taliano, J.; Rao, A.K. Human rabies despite post-exposure prophylaxis: a systematic review of fatal breakthrough infections after zoonotic exposures. Lancet Infect Dis 2023, 23, e167–e174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GJ, Z.; RQ, L. Analysis of the reasons for immunization failure of rabies vaccine in 67 cases. Journal of Jining Medical College 1992, 15, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Weekly, T.W.o.a.o.C.N. A 3-year-old boy passed away after being bitten by a dog, and the dog's owner has not been found to this day. 2024.

- Qing, R.; Huang, L. Xi'an Woman, 32, Succumbs to Rabies After Dog Bite Despite Receiving Four Vaccine Shots. Huashang Newspaper 2017.

- Wu, Y. Xi'an Health Commission Claims Rabies Vaccine Administered in Fatal Case Was Compliant, Family to Sue Hospital. News Peach Uptide 2017.

- Wuhu Boy Dies of Rabies After Being Bitten by Dog. Legal Daily 2018.

- Boy Dies 13 Days After Dog Bite Despite Three Vaccine Doses: Why Did Rabies Still Strike? CCTV.com 2018.

- Knobel, D.L.; Cleaveland, S.; Coleman, P.G.; Fèvre, E.M.; Meltzer, M.I.; Miranda, M.E.; Shaw, A.; Zinsstag, J.; Meslin, F.X. Re-evaluating the burden of rabies in Africa and Asia. Bull World Health Organ 2005, 83, 360–368. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, H.; Hou, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, G.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Lin, R.; Xue, M.; Hu, H.; Liu, M.; et al. Global burden of rabies in 204 countries and territories, from 1990 to 2019: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Int J Infect Dis 2023, 126, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemachudha, T.; Laothamatas, J.; Rupprecht, C.E. Human rabies: a disease of complex neuropathogenetic mechanisms and diagnostic challenges. Lancet Neurol 2002, 1, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemachudha, T.; Ugolini, G.; Wacharapluesadee, S.; Sungkarat, W.; Shuangshoti, S.; Laothamatas, J. Human rabies: neuropathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Neurol 2013, 12, 498–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karliner, J.S.; Belaval, G.S. INCIDENCE OF REACTIONS FOLLOWING ADMINISTRATION OF ANTIRABIES SERUM; STUDY OF 526 CASES. Jama 1965, 193, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafkin, B.; Alls, M.E.; Baer, G.M. Human rabies globulin and human diploid vaccine dose determinations. Dev Biol Stand 1978, 40, 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, K.G.; Turner, G.S. Studies with human diploid cell strain rabies vaccine and human antirabies immunoglobulin in man. Dev Biol Stand 1978, 40, 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow, E.; Torvaldsen, S.; Newall, A.T.; Wood, J.G.; Sheikh, M.; Kieny, M.P.; Abela-Ridder, B. Recent advances in the development of monoclonal antibodies for rabies post exposure prophylaxis: A review of the current status of the clinical development pipeline. Vaccine 2019, 37 Suppl 1, A132–a139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Report of the Sixth WHO Consultation on Monoclonal Antibodies in Rabies Diagnosis and Research, The Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA, 2-3 April 1990; 1990.

- Nicholson, K.G. Modern vaccines. Rabies. Lancet 1990, 335, 1201–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Expert Consultation on Rabies. Second report. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 2013, 1-139, back cover.

- WHO. WHO Expert consultation on rabies: Third report.; 2018.

- FDA. Rabies: Developing Monoclonal Antibody Cocktails for the Passive Immunization omponent of Post-Exposure ProphylaxisGuidance for Industry. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/151102/download.

- NMPA. Technical Guidelines for Clinical Trials of New Monoclonal Antibody Drugs Against Rabies Virus. Available online: https://www.cde.org.cn/zdyz/domesticinfopage?zdyzIdCODE=b8d20904bd51aa02b508c87fb81af65d.

- Chao, T.Y.; Ren, S.; Shen, E.; Moore, S.; Zhang, S.F.; Chen, L.; Rupprecht, C.E.; Tsao, E. SYN023, a novel humanized monoclonal antibody cocktail, for post-exposure prophylaxis of rabies. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017, 11, e0006133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, X.J.; Dong, G.M.; Liu, X.Q.; Liu, S.; Liu, C.; Chen, Q.J.; Yin, W.W.; Wang, C.L. [Progress and prospect of clinical application of anti-rabies virus monoclonal antibody preparation]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2023, 103, 2475–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled multicentric Phase I/II study to evaluate the safety, tolerability and neutralizing activity of Rabimabs (A murine anti-rabies monoclonal antibody cocktails)against rabies virus in healthy subjects (CTRI/2012/12/003225). Available online: https://ctri.nic.in/Clinicaltrials/pmaindet2.php?EncHid=NTcxNg==&Enc=&userName=CTRI/2012/12/003225.

- MX, W.; M, J.; M, J. Safety of a single injection with recombinant human rabies immunoglobin at various dosages in humans. Chin. J. Biolog 2013, 26, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.N.; Meng, Y.J.; Bai, Y.H.; Li, Y.F.; Yang, L.Q.; Shi, N.M.; Han, H.X.; Gao, J.; Zhu, L.J.; Li, S.P.; et al. Rabies Virus Neutralizing Activity, Safety, and Immunogenicity of Recombinant Human Rabies Antibody Compared with Human Rabies Immunoglobulin in Healthy Adults. Biomed Environ Sci 2022, 35, 782–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Zhou, J.; Guo, J.; Pu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Shu, Q.; et al. Comparing recombinant human rabies monoclonal antibody (ormutivimab) with human rabies immunoglobulin (HRIG) for postexposure prophylaxis: A phase III, randomized, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Int J Infect Dis 2023, 134, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Wu, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, X.; Hu, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Tsao, E.; Liu, M.; Li, C. Safety, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of SYN023 alone or in combination with a rabies vaccine: An open, parallel, single dose, phase 1 bridging study in healthy Chinese subjects. Antiviral Res 2020, 184, 104956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClain, J.B.; Chuang, A.; Moore, S.M.; Tsao, E. Safety, Pharmacokinetics, and Neutralizing Activity of SYN023, a Mixture of Two Novel Antirabies Monoclonal Antibodies Intended for Use in Postrabies Exposure Prophylaxis. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev 2021, 10, 807–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClain, J.B.; Chuang, A.; Reid, C.; Moore, S.M.; Tsao, E. Rabies virus neutralizing activity, pharmacokinetics, and safety of the monoclonal antibody mixture SYN023 in combination with rabies vaccination: Results of a phase 2, randomized, blinded, controlled trial. Vaccine 2021, 39, 5822–5830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, A. Rabies Vaccines: Duration Of Pep From 90 Days To 7 Days. International Journal of Clinical Reports and Studies 2024, 3. [Google Scholar]

- H, S.R.; Khobragade, A.; Satapathy, D.; Gupta, M.; Kumar, S.; Bhomia, V.; V, R.; Desai, M.; Agrawal, A.D. Safety and Immunogenicity of a novel three-dose recombinant nanoparticle rabies G protein vaccine administered as simulated post exposure immunization: A randomized, comparator controlled, multicenter, phase III clinical study. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2021, 17, 4239–4245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, L.; Cheng, Z.; Cheng, L.; Kun, X.; Yan, L.; Haichao, L. A study on the outcome-based training method of rabies passive immunization injection. Chin J Emerg Resusc Disaster Med 2021, 16, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Huang, S.; Lu, S.; Zhang, M.; Meng, S.; Hu, Q.; Fang, Y. Severe multiple rabid dog bite injuries in a child in central China: Continuous 10-year observation and analysis on this case. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2020, 16, 904–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholand, S.J.; Quiambao, B.P.; Rupprecht, C.E. Time to Revise the WHO Categories for Severe Rabies Virus Exposures-Category IV? Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banović, P.; Mijatović, D.; Simin, V.; Vranješ, N.; Meletis, E.; Kostoulas, P.; Obregon, D.; Cabezas-Cruz, A. Real-world evidence of rabies post-exposure prophylaxis in Serbia: Nation-wide observational study (2017-2019). Travel Med Infect Dis 2024, 58, 102697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).