1. Introduction

Selenium (Se), a metalloid element with atomic number 34, belongs to Group 16 (the chalcogens) of the periodic table and exhibits chemical properties similar to those of sulfur [

1]. Widely distributed in the Earth’s crust, selenium enters surface waters through both natural processes, such as volcanic activity, soil erosion, and forest fires, and anthropogenic activities, including mining, fossil fuel combustion, agricultural irrigation, and the discharge of wastewater and sewage sludge [

2]. In industrial contexts, selenium is primarily recovered as a by-product of electrolytic copper refining. It is utilized in the production of solar panels, as an additive in glass manufacturing, and as a dietary supplement for both humans and livestock [

3]. These uses contribute to Se release into the environment, raising concerns due to its dual role as an essential micronutrient and a potential toxicant. Se is required by mammals in trace amounts, largely due to its incorporation into selenoproteins such as formate dehydrogenase. However, excessive Se exposure can result in adverse health effects, necessitating the regulation of its concentration in aquatic ecosystems [

1].

Microbial processes are recognized as key drivers in the environmental transformation and mobility of Se [

4]. Under oxidizing conditions, Se predominantly exists as the oxyanions selenate (SeO₄²⁻; Se(VI)) and selenite (SeO₃²⁻; Se(IV)). Microorganisms capable of Se metabolism can reduce these soluble species to elemental Se (Se⁰) or transform them into volatile methylated compounds (e.g., dimethyl selenide [CH₃SeCH₃], dimethyl diselenide [CH₃SeSeCH₃]), significantly altering Se’s environmental fate and bioavailability [

5].

Numerous Se-metabolizing bacteria have been isolated and studied to elucidate their metabolic pathways [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12] .

Thauera selenatis, for example, was isolated from a bioreactor treating Se-laden wastewater [

6]. It reduces Se(VI) to Se(IV) via a periplasmic Se(VI) reductase complex (SerABC) [

7,

8], followed by non-specific reduction of Se(IV) to Se⁰ via nitrite reductase [

9]. This organism is a foundational model for understanding Se respiration at the molecular level. Other notable strains include

Enterobacter cloacae SLD1a-1, isolated from Se-contaminated waters in California’s San Joaquin Valley [

10], and

Stutzerimonas stutzeri NT-I, recovered from a Se smelting facility’s wastewater treatment plant [

11]. The latter not only performs reductive transformations but also produces methylated Se compounds under aerobic conditions [

12]. While the majority of Se-metabolizing bacteria have been isolated from environments heavily polluted with Se or other toxic elements, Se is also present at low concentrations in non-contaminated ecosystems. To gain a comprehensive understanding of Se’s biogeochemical cycle and the role of microbial communities in regulating its dynamics, it is essential to study Se-metabolizing bacteria from typical, non-polluted environments, which constitute the majority of the biosphere.

This study aims to isolate and characterize Se-metabolizing bacteria from urban environments in Japan that are not impacted by elevated levels of toxic elements. Environmental samples, including aquatic plants from home gardens, urban drainage ditches, and rivers, were collected from twelve distinct sites. Novel Se-metabolizing strains were successfully isolated, and representative bacteria were further analyzed to determine temporal changes in Se speciation. These findings offer new insights into Se cycling in typical urban freshwater ecosystems and expand our understanding of the ecological roles of Se-transforming bacteria in non-contaminated habitats.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Growth Medium

BactoTM Trypticase Soy Broth (TSB; Becton–Dickinson, NJ, USA) or low-concentration TSB with inorganic salts (TSB-MS) was used for the enrichment and the cultivation of Se-metabolizing microorganisms. The composition of TSB-MS is as follows; 1 g/L TSB, 1 g/L (NH4)2SO4, 0.5 g/L Sodium Citrate・2H2O, 0.1 g/L MgSO4・7H2O, 3.24 g/L Sodium Acetate (pH7.0), 10 mM HEPES (pH7.0), 0.14 g/L K2HPO4, 0.04 g/L KH2PO4. Both media were sterilized by autoclave (121°C, 20 min), and sodium selenate was added to a final concentration of 5 mM as needed. For static and aerobic cultivation, 20 mL of medium was added to a 50 mL vial and capped with a silicone sponge plug. The anaerobic culture medium was prepared by replacing the gas phase of the vial with nitrogen (99.99%) and then sealing it with a butyl rubber septum and an aluminum cap. The TSB and TSB-MS agar media were prepared by adding 20 g/L of Quality Agar BA-30 (INA Food Industry, Nagano, Japan) before autoclaving.

2.2. Environmental Samples

Water, soil, and plant samples were collected from general environments with no known history of Se contamination and used in the experiment. The samples A to L used in this study are shown in

Table 1. For soil samples, 1 g-wet was suspended in 10 mL of sterile saline (8 g/L NaCl) and allowed to stand for 1 minute, and the supernatant was used. For plants, an appropriate amount was suspended in 10 mL of sterile saline, and the supernatant was used after allowing to stand for 1 minute.

2.3. Enrichment and Isolation of Se-Metabolizing Microorganisms

One mL of the pretreated sample A was inoculated into TSB-MS and cultured under static condition at 30°C for 2 weeks. 1 mL of the resulting culture was inoculated into a fresh medium of the same composition and cultured under the same conditions repeatedly for 1 week to enrich for Se-metabolizing microorganisms. The aliquot of the enriched culture of the seventh batch was then diluted appropriately and spread onto TSB-MS agar containing 5 mM of Se(VI). Samples B to L were appropriately diluted and spread onto TSB agar containing 5 mM of Se(VI) without enrichment. The agar plates were cultivated at 30°C, and red colonies, indicating the production of Se⁰ in amorphous form, were isolated. The isolated microorganisms were stored at −80°C in 25% glycerol until use.

2.4. Evaluation of the Se Metabolic Potential of the Isolates

One colony of each isolated selenium-metabolizing microorganism was inoculated into TSB medium and cultured aerobically at 180 rpm for 24 hours in the rotary-shaking incubator at 30°C. 200 μL of the culture was inoculated into TSB medium containing 5 mM sodium selenate and cultured anaerobically at 30°C, 180 rpm for 1 week. Aliquot of the culture medium was taken as a sample before and after the cultivation and centrifuged (10,000 xg, 4°C, 15 minutes) to measure total Se in the supernatant, denoted as ”soluble Se“ hereafter.

2.5. Detailed Analysis of the Se Metabololism of the Representative Strains

One colony of the five representative strains, Citrobacter freundii K21-1, Scandinavium hiltneri K24-1, Citrobacter braakii K24-2, Klebsiella aerogenes K24-4, and Citrobacter freundii K24-5, was inoculated into 20 mL of TSB medium and cultivated aerobically at 30°C and 180 rpm for 24 hours using a rotary-shaking incubator, respectively. 200 μL of the resulting culture was inoculated into a new medium of the same composition and cultivated under the same conditions for 24 hours. 200 μL of the resulting culture was inoculated into 20 mL of TSB medium containing 5 mM Se(VI) and cultivated under anaerobic conditions with rotary shaking (30°C, 180 rpm). Individual vials were periodically sacrificed for analysis. The collected samples were centrifuged (10,000 xg, 4°C, 15 minutes) to separate the supernatant and precipitate, which were then stored at −20°C until analysis.

2.5. Analytical Procedures

The Se(VI) and Se(IV) concentrations in the supernatant were analyzed using an ion chromatograph (ICS-1100, Thermo Fischer Scientific, MA, USA). The samples were appropriately diluted with 2 mM Na2CO3, filtered using a syringe filter (DISMIC 03CP045AN, Advantec, Tokyo, Japan), and subjected to analysis. A Dionex IonPac AG12A 4 x 50 mm (Thermo Fischer Scientific) was used as the guard column, a Dionex IonPac AS12A 4 x 200 mm (Thermo Fischer Scientific) was used as the separation column, and 2 mM Na2CO3 at 1.5 mL/min was used as the eluent. Other conditions were as recommended for the Dionex IonPac AS12A. Sodium selenate (≧98%; Nacalai Tesque, Inc., Kyoto, Japan) and sodium selenite (≧97%; Nacalai Tesque) were dissolved in ultrapure water to prepare 5 mM Se(VI) and Se(IV) solutions, which were used as standard solutions.

Soluble Se was analyzed by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES; Avio200, PerkinElmer, MA, USA) or flame atomic absorption spectrometry (FAAS; iCE3500, Thermo Fischer Scientific) with air-acetylene flame. Total Se in the precipitate, denoted as ”Solid Se“ hereafter, was analyzed after oxidative decomposition treatment with mixed acid (63.0% nitric acid: 96.0% sulfuric acid = 20:1). 4 mL of mixed acid was added to the precipitate recovered from 20 mL of culture medium by centrifugation (10,000 xg, 4°C, 15 min). The mixture in the centrifugation tube was tightly sealed and heated at 100°C for 10 min. After cooling, 16 mL of ultrapure water was added and mixed, and the mixture was analyzed by ICP-OES or FAAS. A 1,000 mg/L Se standard solution (Kanto Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) was used as the standard for ICP-OES and FAAS.

2.5. DNA Extraction and 16S rRNA Gene Sequence Analysis

Cells were harvested from 1 mL of Se-metabolizing microorganism culture by centrifugation (20,000 x

g, 4°C, 1 min) and stored at −20°C until use. Genomic DNA was extracted from the cells using NucleoSpin Microbial DNA (TaKaRa Bio, Shiga, Japan). The 16S ribosomal RNA gene was amplified by polymerase chain reaction using genomic DNA as a template, Tks Gflex™ DNA Polymerase (TaKaRa Bio), and primers 27F (5’-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3) and 1492R (5’-GGCTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3’). The PCR products were purified using NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-up (TaKaRa Bio), and entrusted to Macrogen Japan (Tokyo, Japan) for the Sanger sequencing. The obtained 16S rRNA gene sequence was analyzed using EzBioCloud (

https://www.ezbiocloud.net/) [

13] to identify the most homologous microorganism.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Isolation of Se-Metabolizing Microorganisms

Se-metabolizing microorganisms were isolated from environmental samples A–L (

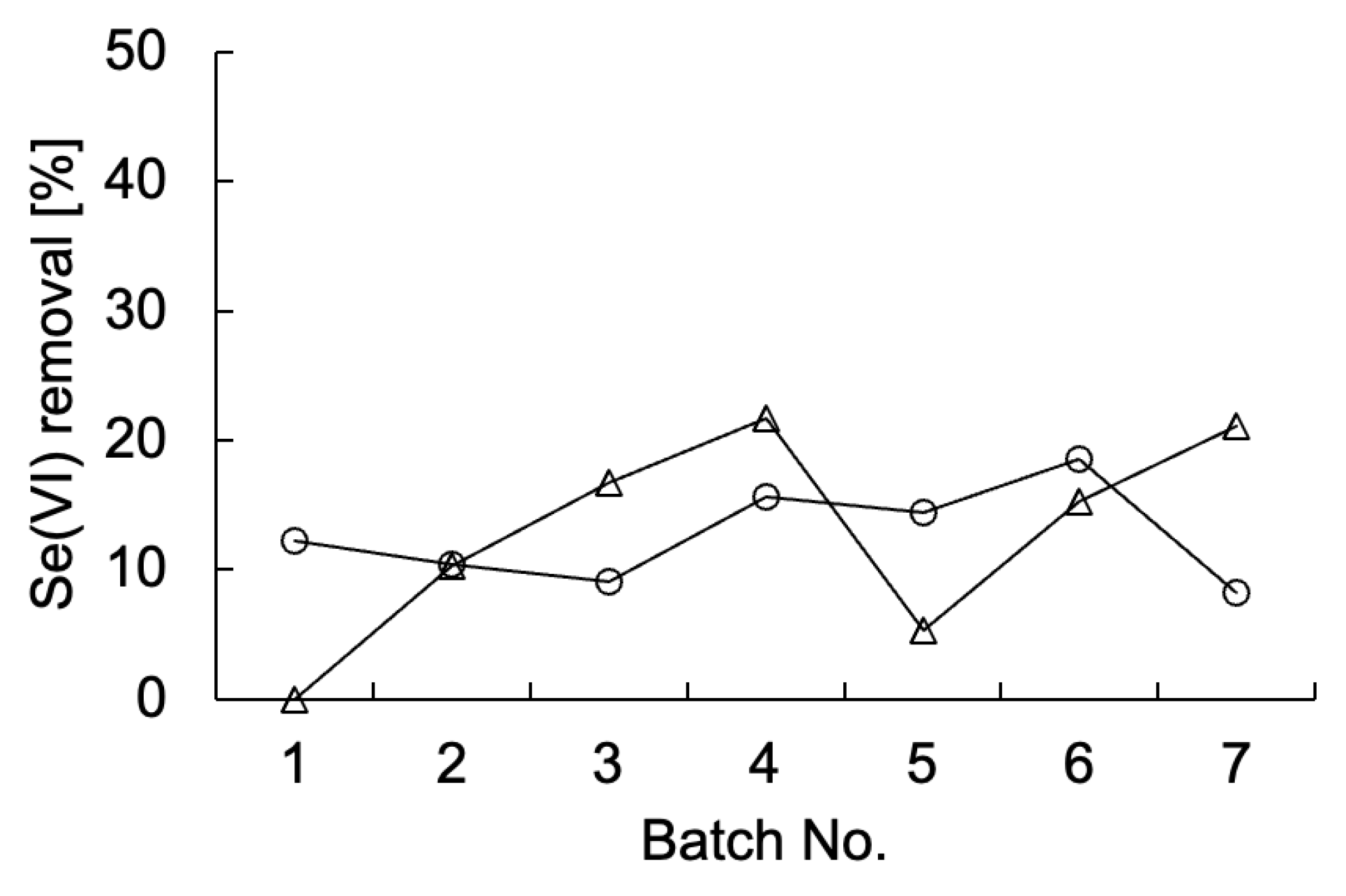

Table 1), none of which were known to be contaminated with Se. First, the enrichment of Se-metabolizing microorganisms in tape grass grown in Tomoe River, Shizuoka, Japan (sample A) was conducted. The sample was cultured repeatedly under static conditions in TSB-MS medium supplemented with 5 mM Se(VI). Duplicate enrichment cultures (designated as tape grass 1 and 2) were prepared under the same condition. Se(VI) removal was assessed at the end of each batch culture (

Figure 1). Both enrichment cultures consistently removed approximately 10–20% of the Se(VI) over seven successive batch cultures, suggesting sustained growth of Se(VI)-reducing microorganisms likely associated with the surface of the tape grass. Because these cultures were maintained under static conditions, oxygen availability was limited to diffusion from the air above the culture medium. Thus, it is plausible that the enriched microorganisms were capable of Se(VI) reduction under microaerobic or aerobic conditions. Ion chromatography analysis failed to detect Se(IV), and a light red coloration was observed in the culture fluid at the end of each batch (data not shown), implying that any Se(IV) generated was rapidly reduced to Se⁰. The final enrichment culture was plated onto TSB-MS agar containing 5 mM Se(VI) and incubated under anaerobic conditions. A dense red colony indicative of Se⁰ production was isolated from the enrichment tape grass 2 and designated strain K21-1.

For samples B–L, appropriate pretreatment was conducted prior to direct plating onto TSB agar containing 5 mM Se(VI). From each sample, one colony displaying a distinct red coloration was selected, resulting in the isolation of strains K24-1 through K24-11.

All 12 isolates were subjected to 16S rRNA gene sequencing (

Table 2). Sequence homology analyses revealed that all isolates were bacterial. Strains K24-1, K24-2, and K24-4 showed >99% sequence identity with type strains of

Scandinavium hiltneri,

Citrobacter braakii, and

Klebsiella aerogenes, respectively. The remaining nine isolates were identified as

Citrobacter freundii.

3.2. Evaluation of Se Metabolic Potential in Isolates

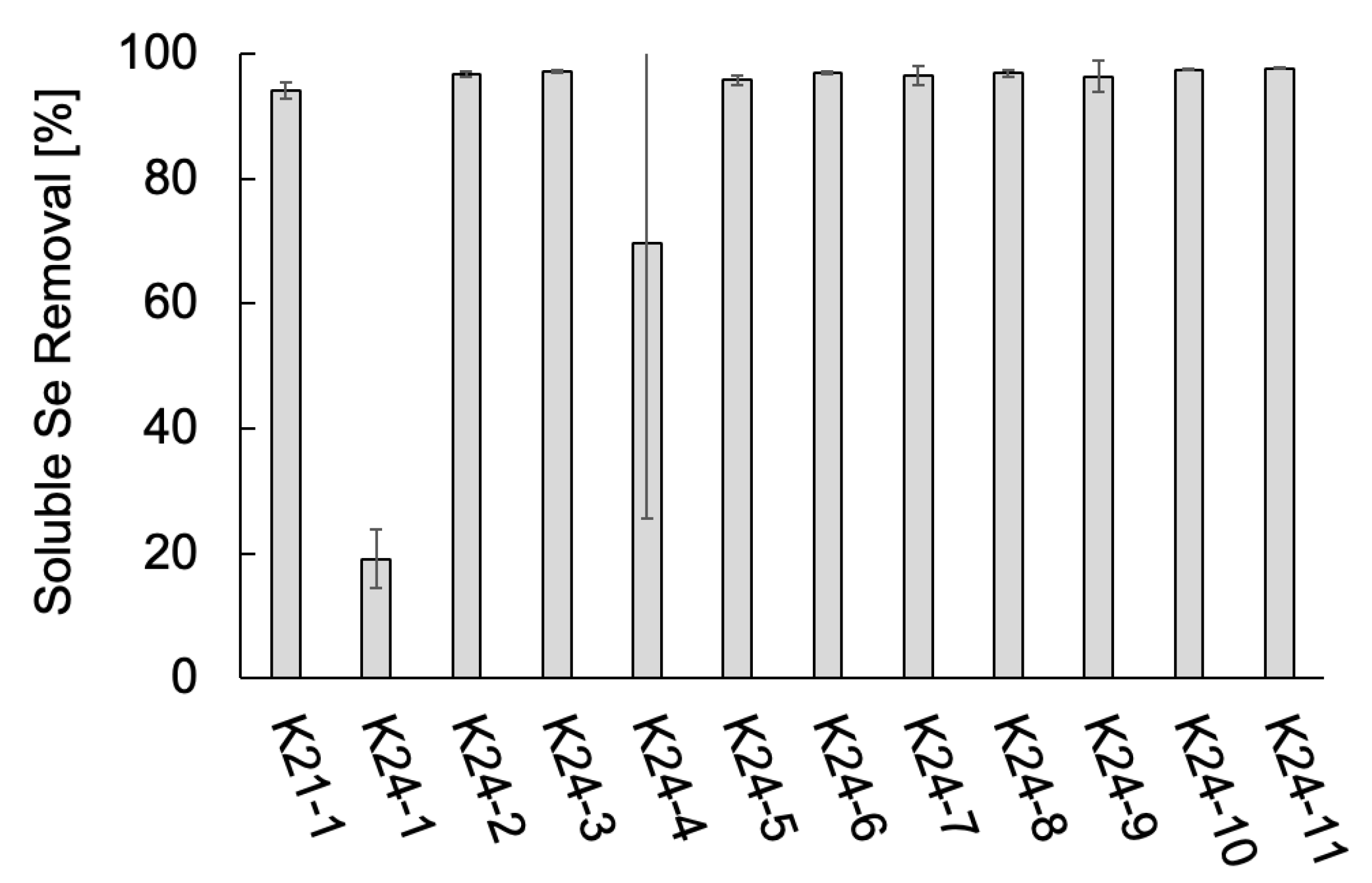

The Se metabolic capabilities of the 12 isolates were assessed by comparing their ability to reduce soluble Se species. The soluble Se removal of the 12 isolates are shown in

Figure 2. All isolates exhibited some level of Se removal. Ten isolates, all identified as

Citrobacter spp. (K21-1, K24-2, K24-3, K24-5 through K24-11), removed over 95% of the supplemented Se. In contrast, strain K24-1 demonstrated the lowest removal efficiency (19%). Two cultures of K24-4 exhibited removal rates exceeding 90%, although that of the other culture was 19%, resulting in 69% on average. These results confirm that all 12 isolates possess Se metabolic capabilities. In particular, the

Citrobacter strains demonstrated high Se removal efficiency, suggesting robust Se-metabolizing activity.

3.3. Se Metabolism in Selected Strains: K21-1, K24-1, K24-2, K24-4, and K24-5

To further characterize Se metabolism, five representative strains,

Citrobacter freundii K21-1,

Scandinavium hiltneri K24-1,

Citrobacter braakii K24-2,

Klebsiella aerogenes K24-4, and

Citrobacter freundii K24-5, were analyzed in detail. Each was cultured in TSB medium containing 5 mM Se(VI), and changes in Se speciation were monitored (

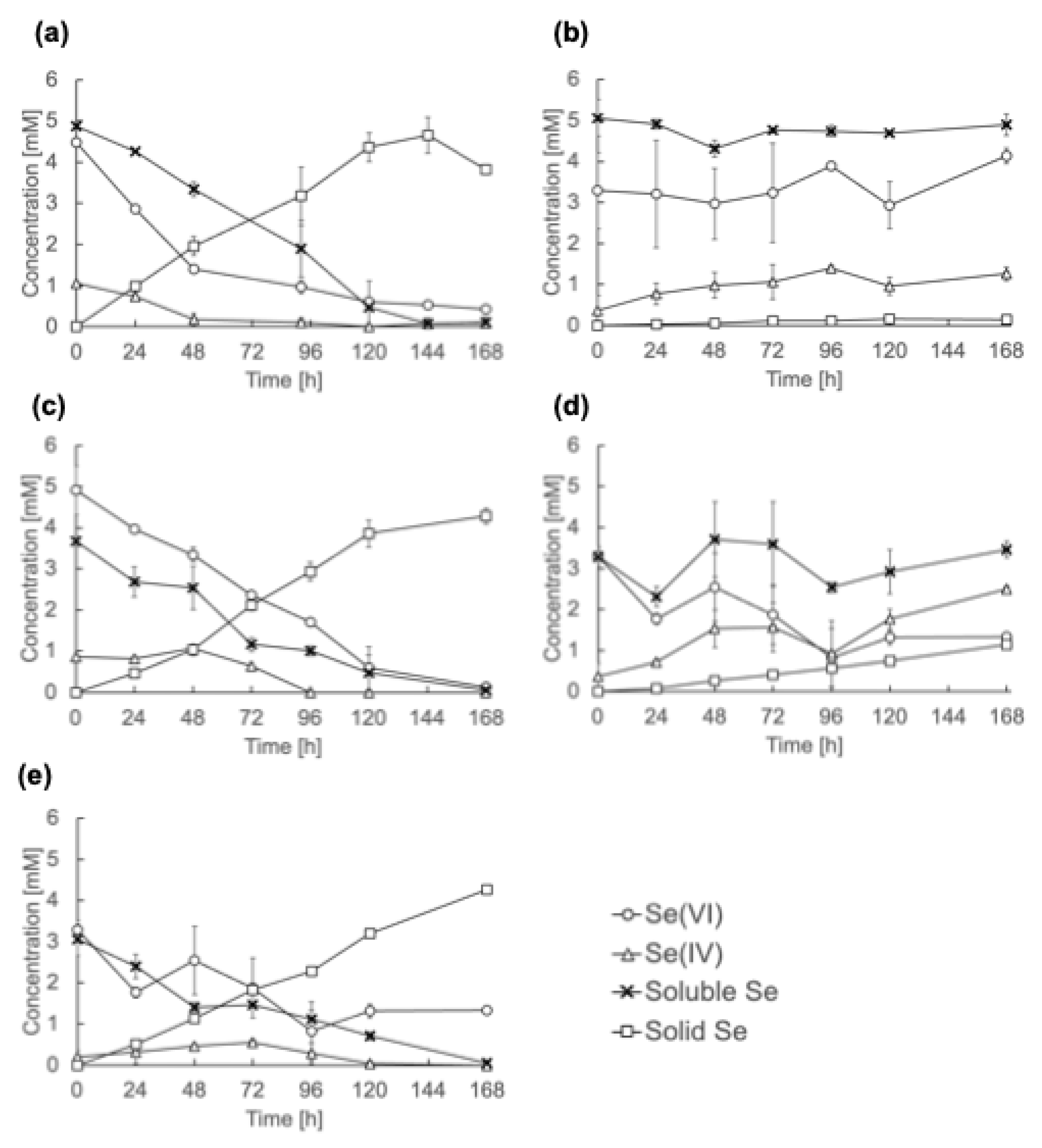

Figure 3).

Strains K21-1, K24-2, and K24-5 (

Figure 3A,

Figure 3C, and

Figure 3E, respectively) displayed similar Se reduction profiles. Se(VI) concentrations declined steadily and fell below 0.5 mM by the end of the cultivation period. Se(IV) concentrations remained consistently below 1 mM, while solid Se accumulated over time. These observations indicate efficient reduction of Se(IV) to Se⁰, without significant intermediate accumulation. This contrasts with many previously described Se(VI)-reducing bacteria, which often display limited Se(IV)-reducing activity (9, 14). The findings suggest that these

Citrobacter strains are highly efficient Se reducers.

In contrast,

S. hiltneri K24-1 showed an increase in Se(IV) concentration to 1.3 mM by the end of cultivation (

Figure 3B), with no appreciable reduction in overall soluble Se or increase in solid Se. Notably, the initial Se(VI) concentration was 3.3 mM, lower than the supplemented 5 mM, indicating rapid adsorption or partial uptake. These results suggest limited Se metabolic activity, despite the ability to reduce Se(VI) to Se(IV).

K. aerogenes K24-4 reduced Se(VI) to 1.3 mM, produced 2.5 mM Se(IV), and generated 1.1 mM solid Se (

Figure 3D). This profile indicates Se metabolic activity, although with limited efficiency under the tested conditions.

Citrobacter spp. are widespread in aquatic ecosystems, and their involvement in Se cycling is well documented. For instance,

C. freundii Iso Z7 was isolated from a Se-impacted lake sediment, and its efficient Se(VI) to Se⁰ reduction was demonstrated [

15].

C. braakii was isolated from a Se-remediation facility, where its Se-removal capacity was enhanced by zero-valent iron [

16]. The Se metabolism in

Citrobacter sp. JSA isolated from freshwater sediment was characterized [

17]. The genome analysis of

C. freundii RLS1 predicted the involvement of the

ynfEGH in Se(VI) reduction [

18].

While the reduction of Se(VI) to Se⁰ by

Citrobacter spp. is well-established, the simultaneous isolation of multiple Se(VI)-reducing

Citrobacter strains from diverse, Se-uncontaminated environments is notable. This contrasts with previous research, which has predominantly focused on Se-metabolizing bacteria from contaminated habitats [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. The presence of such organisms in pristine environments has implications for understanding natural Se biogeochemistry. It remains unclear whether Se metabolism is a universal trait within

Citrobacter spp.. However, Theisen and Yee (2014) noted that the putative Se(VI) reductase operon

ynfEGH is conserved across the genus [

18], warranting further molecular ecological studies to elucidate its distribution and functional significance.

Additionally, this study provides the first indication of Se metabolism in

S. hiltneri under laboratory conditions.

S. hiltneri, a newly described species within Enterobacteriaceae [

19], has not been previously associated with Se transformation.

Klebsiella strains from river sediments also demonstrated Se reduction, although at lower efficiencies [

20]. These observations suggest that, despite relatively lower activity under artificial conditions, these species may contribute to Se speciation in natural ecosystems.

4. Conclusions

To gain a deeper understanding of Se-metabolizing microorganisms, which play a key role as mediators in the biogeochemical cycling of Se, this study elucidated the Se metabolism of 12 bacterial strains isolated from urban environmental samples. Notably, 10 of these strains, identified as members of the genus Citrobacter, demonstrated the ability to rapidly reduce high concentrations of Se(VI). Despite originating from environments not contaminated with Se, these bacteria exhibited pronounced Se-metabolizing activity, suggesting that such metabolic capacity is an inherent characteristic of Citrobacter sp.. Consequently, the presence of Citrobacter may indicate Se metabolic potential in environmental microbial communities. Future research should clarify the molecular biological mechanisms underlying Se metabolism in Citrobacter, thereby facilitating a more detailed understanding of the ecology of Se-metabolizing microorganisms in natural environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K.; methodology, M.K., Y.T.; formal analysis, M.K.; investigation, M.K., I.I., T.K., R.S., H.T., H.Y., Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K., I.I., T.K., R.S., H.T., H.Y., Y.W.; writing—review and editing, M.K., Y.T.; visualization, M.K.; supervision, M.K.; project administration, M.K.; funding acquisition, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI, grant number 22K12434.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Se(VI) |

Selenate |

| Se(IV) |

Selenite |

| Se0

|

Elemental selenium |

| ICP-OES |

Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry |

| FAAS |

Flame atomic absorption spectrometry |

References

- Young, T.F.; Finley, K.; Adams, W.; Besser, J.; Hopkins, W.A.; Jolley, D.; McNaughton, E.; Presser, T.S.; Shaw, D.P.; Unrine, J. What you need to know about selenium. In Ecological Assessment of Selenium in the Aquatic Environment; Chapman, P.M., Adams, W.J., Brooks, M.L., Delos, C.G., Luoma, S.N., Maher, W.A., Ohlendorf, H.M., Presser, T.S., Shaw, D.P., Eds.; CRC Press: Fl, USA, 2010; pp. 7–45. [Google Scholar]

- Maher, W.; Roach, A.; Doblin, M.; Fan, T.; Foster, S.; Garrett, R.; Möller, G.; Oram, L.; Wallschläger, D. Environmental sources, speciation, and partitioning of selenium. In Ecological Assessment of Selenium in the Aquatic Environment; Chapman, P.M., Adams, W.J., Brooks, M.L., Delos, C.G., Luoma, S.N., Maher, W.A., Ohlendorf, H.M., Presser, T.S., Shaw, D.P., Eds.; CRC Press: Fl, USA, 2010; pp. 47–92. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Geological Survey. Selenium. In Mineral Commodity Summaries; 2025; pp. 158–159.

- Stolz, J.F.; Basu, P.; Santini, J.M.; Oremland, R.S. Arsenic and selenium in microbial metabolism. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2006, 60, 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenz, M.; Lens, P.N.L. The essential toxin: the changing perception of selenium in environmental sciences. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 3620–3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macy, J.M.; Michel, T.A.; Kirsch, D.G. Selenate reduction by a Pseudomonas species: a new mode of anaerobic respiration. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1989, 61, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, I.; Rech, S.; Krafft, T.; Macy, J.M. Purification and characterization of the selenate reductase from Thauera selenatis. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 23765–23768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krafft, T.; Bowen, A.; Theis, F.; Macy, J.M. Cloning and sequencing of the genes encoding the periplasmic-cytochrome B-containing selenate reductase of Thauera selenatis. DNA Seq. 2000, 10, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMoll-Decker, H.; Macy, J.M. The periplasmic nitrite reductase of Thauera selenatis may catalyze the reduction of selenite to elemental selenium. Arch. Microbiol. 1993, 160, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losi, M.E.; Frankenberger Jr, W.T. Reduction of selenium oxyanions by Enterobacter cloacae SLD1a-1: Isolation and growth of the bacterium and its expulsion of selenium particles. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 3079–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuroda, M.; Notaguchi, E.; Sato, A.; Yoshioka, M.; Hasegawa, A.; Kagami, T.; Narita, T. : Yamashita, M.; Sei, K.; Soda, S.; Ike, M. Characterization of Pseudomonas stutzeri NT-I capable of removing soluble selenium from the aqueous phase under aerobic conditions. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2011, 112, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kagami, T.; Narita, T.; Kuroda, M.; Notaguchi, E.; Yamashita, M.; Sei, K.; Soda, S.; Ike, M. Effective selenium volatilization under aerobic conditions and recovery from the aqueous phase by Pseudomonas stutzeri NT-I. Water Res. 2013, 47, 1361–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalita, M.; Kim, Y.O.; Park, S.; Oh, H.S.; Cho, J.H.; Moon, J.; Baek, N.; Moon, C.; Lee, K.; Yang, J.; Nam, G.G.; Jung, Y.; Na, S.I.; Bailey, M.J.; Chun, J. EzBioCloud: a genome-driven database and platform for microbiome identification and discovery. Int J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2024, 74, 006421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, M.; Ike, M.; Nishimoto, S.; Takahashi, K.; Kashiwa, M. Isolation and characterization of a novel selenate-reducing bacterium, Bacillus sp. SF-1. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 1997, 83, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Siddique, T.; Wang, J.; Frankenberger Jr., W. T. Selenate reduction in river water by Citrobacter freundii isolated from a selenium-contaminated sediment. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 1594–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Frankenberger Jr., W. T. Removal of selenate in river and drainage waters by Citrobacter braakii enhanced with zero-valent iron. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakagushi, T.; Nakano, T.; Kimura, Y.; Nogami, S.; Kubo, I.; Morita, Y. Development of a genetic transfer system in selenate-respiring bacterium Citrobacter sp. strain JSA which was isolated from natural freshwater sediment. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2011, 111, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theisen, J.; Yee, N. The molecular basis for selenate reduction in Citrobacter freundii. Geomicrobiol. J. 2014, 31, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddock, D.; Kile, H.; Denman, S.; Arnold, D.; Brady, C. Description of three novel species of Scandinavium: Scandinavium hiltneri sp. nov., Scandinavium manionii sp. nov. and Scandinavium tedordense sp. nov., isolated from the oak rhizosphere and bleeding cankers of broadleaf hosts. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1011653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Okeke, B.C.; Frankenberger Jr, W.T. Bacterial reduction of selenate to elemental selenium utilizing molasses as a carbon source. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 1267–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).