1. Introduction

Contemporary scientific evidence implicates inflammatory processes in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia [

1,

2,

3] with CRP representing one of the most frequently investigated biomarkers for systemic inflammation [

4,

5]. CRP is a nonspecific acute phase protein that is primarily generated by liver cells, in both acute and chronic inflammation, in response to inflammatory cytokines [

6]. A multitude of cross-sectional studies have evidenced increased CRP levels in schizophrenia patients compared to controls [

7,

8,

9] and longitudinal studies have demonstrated that higher CRP levels at baseline may increase the risk of schizophrenia at follow-up [

10,

11]. However, while observational data show a positive association between CRP and schizophrenia risk, Mendelian Randomization (MR) analyses support that genetically elevated CRP protects against schizophrenia risk [

12,

13,

14]. A deficient immune response hypothesis early in life that could lead to chronic infection and the subsequent increased risk of schizophrenia has been proposed as a plausible explanation to reconcile this controversy [

15,

16], but no definite conclusion to disentangle this discrepancy has been reached [

17].

Multiple studies evidenced that CRP levels in patients with schizophrenia are increased during acute phases [

18,

19], as well as in cases with more severe psychopathology [

20,

21], in treatment- resistant [

22] and in antipsychotic- free disorder [

23] and are associated with positive [

24] and negative symptoms [

25,

26], cognitive deficits [

27] and risk of metabolic syndrome [

28]. Metabolic disturbances and obesity are highly prevalent among schizophrenic patients [

29,

30,

31], with obesity affecting more than 50% of these patients [

29]. BMI is frequently used as an index of obesity and its predictive utility for the occurrence of metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia has been confirmed [

32]. According to a research in drug-naïve patients with schizophrenia the levels of BMI and rates of obesity increase in parallel with the duration of the disorder, along its course [

33]. Many factors contribute to elevated BMI in patients with schizophrenia, including disorder-specific symptoms, lifestyle elements and socioeconomic issues, such as negative symptoms, social withdrawal, lack of physical activity, insufficient exercise, inadequate sleep, unhealthy diet and psychotropic medications [

34,

35,

36]. The correlation between schizophrenia and BMI has been investigated in genetic and epidemiological studies [

37,

38,

39,

40] and a recent research, through an MR framework, has revealed a significant causal association between genetically predicted childhood BMI and the subsequent risk of schizophrenia in adulthood [

41].

The positive association between BMI and CRP levels in the general population has been established [

42,

43] and the raised CRP values observed in individuals with an increased BMI are linked to a condition of low-grade systemic inflammation that affects overweight and obese individuals [

44,

45]. Research findings support that being overweight significantly raises the likelihood of clinically relevant increases in CRP, particularly pronounced in individuals with obesity [

46,

47]. MR studies evidence a directional relationship from BMI to CRP levels, whereas the bidirectional association has not been confirmed [

43,

48]. Among patients with schizophrenia many studies have documented the positive association between BMI and CRP levels; however, the directional relationship between these biomarkers remains elusive due to the cross-sectional nature of most of these studies [

28,

49]. A recent longitudinal research indicated a bidirectional relationship between BMI and CRP, with the effect of CRP on future BMI being more potent than vice versa [

50]. More specifically, research findings support that assuming equal adiposity, patients with schizophrenia may have higher inflammation compared to healthy controls [

11]. Thus, inflammation and the metabolic syndrome in schizophrenia have been the focus of scientific interest and individuals with schizophrenia consistently show several metabolic disruptions and have increased systemic inflammation both having effects on the brain and contributing to higher morbidity and premature mortality associated with the disorder [

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56].

Research evidence suggests that the inflammatory response may serve as the final common pathway through which environmental risk factors are implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia [

57,

58,

59]. Social support from relationships with family and significant others, possibly through beneficial influences on immune-mediated inflammatory processes, has been identified as a protective factor associated with lower rates of morbidity and mortality [

60,

61]. Perceived social support which is assumed to be a more representative aspect, appraising the quality of support received, protects against the risks of inflammation [

62]. Perceived family support is considered an essential element of social support and refers to how an individual views the assistance provided by the other family members. Most people with schizophrenia live with their family members and even for those who live separately, their families are actively involved in their relative’s life providing care and support [

63,

64]. Parental support significantly influences the development of coping strategies for individuals with schizophrenia [

65]. Existing literature reveals associations between parenting behaviors and child inflammatory markers, suggesting that positive parenting is associated with lower levels of inflammation, while negative parenting is linked to higher levels of inflammation [

66]. Also, a higher level of parental support was associated with decreased child inflammation especially when medical conditions were present [

67]. Concerning the role of parent – child attachment in obesity, a meta-analytic review demonstrated that BMI was negatively related with secure attachment [

68]. Moreover, insecure and disorganized attachment in early infancy has been associated with higher levels of CRP levels in early childhood and predicted later obesity, compared to children with secure attachment [

69]. Also, elevated CRP levels and BMI were documented in adults with schizophrenia and positive records for childhood maltreatment [

70].

Increased physical morbidity and premature mortality among patients with schizophrenia, mostly due to the higher prevalence of cardiometabolic disorders, have extensively been studied [

71,

72]. These disorders are associated with increased levels of circulating inflammatory markers, such as CPR [

73]. This low-grade inflammation and the metabolic alterations observed among patients with schizophrenia have also been consistently reported [

74,

75,

76] and both inflammatory and metabolic indexes may serve as predictors of clinical outcome [

52,

77]. Recent research confirmed that the metabolic disturbances recorded in patients with schizophrenia are mainly attributed to schizophrenia - induced obesity [

78]. A large-scale multicenter study provided evidence that individuals with both obesity and schizophrenia exhibited more pronounced neurostructural brain alterations than people with only one of these conditions [

51]. Research findings have identified a shared genetic liability between binge eating behaviors and schizophrenia, with impaired social cognition as an intermediate phenotype [

79]. Also, disordered eating behaviors, such as emotional eating and loss of control eating are prevalent among patients with schizophrenia and are linked with both obesity and inflammation [

80,

81,

82,

83]. In search for a favorable factor that would counteract these adverse conditions, family support emerged and several studies evidenced that the active involvement and systematic engagement of family members in the care of schizophrenic patients predicted positive outcomes, by enhancing adaptation resources, improving treatment adherence and ultimately the quality of life of patients with schizophrenia [

84]. However, schizophrenia has a tendency to cause cognitive deficits in various domains, including social cognition [

85,

86], which could affect the ability to perceive family support [

87], and possibly undermine its protective influence [

88].

The theoretical framework of this study was that the perceived presence of supportive family relationships has the ability to protect individuals with schizophrenia from the adverse inflammatory and metabolic pathophysiological processes, while the perceived absence of such relationships increases disease risks. A literature review did not retrieve any study that explored the association between CRP and perceived family support and further examined whether this association differed along the BMI spectrum in a sample of outpatients with schizophrenia, leaving a knowledge gap we sought to address. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore the interrelations between CRP, BMI and perceived family support among individuals with schizophrenia in outpatient treatment. More specifically, elucidating the extent to which the association between CRP and family support is stratified by BMI could improve our understanding about the role of perceived family support and provide opportunities for psychotherapeutic and psychosocial interventions. The abovementioned assumptions give rise to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. BMI is positively associated with and predicts CRP.

Hypothesis 2. Perceived Family Support is negatively related to and predicts CRP.

Hypothesis 3. BMI interacting with Perceived Family Support serves as a moderator in the association between CRP and Perceived Family Support. The moderator effect of the BMI is assumed to be focused on obese individuals who have higher levels of low-grade inflammation due to their increased BMI.

2. Subjects and Methods

2.1. Research Design

A cross-correlation study was conducted to address the above hypothetical statements. Participants were outpatients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia who received treatment at the Outpatient Psychiatric Department of ‘’Sotiria” General Hospital from October 2022 to March 2024. After the approval from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of ‘’Sotiria” General Hospital (Approval Number: 26741/21-10-2021), the researchers explained the research objectives to the participants who provided both written and verbal informed consent. This study was performed in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki (1975, revised 2008), following the ethical principles outlined in the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR - 2016/679) of the European Union, and the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Prior to the performance of any procedures related to this study and according to the ethical considerations, patients were assured that any information obtained would remain confidential, that participation in the survey was completely voluntary and that at any point potential volunteers could opt to withdraw from the study. Once each participant had received comprehensive information on the study procedure and recruited, an appointment was arranged the following morning between 8:00 and 9:00 a.m. to collect the demographic and clinical data, weight and height measurements and then proceed to the laboratory examinations. Before venous blood was drawn, patients were requested to fast for more than eight hours and to maintain a normal diet the night before, avoid alcohol consumption and refrain from strenuous exercise. At the end, each participant was required to complete a semi-structured form created by research staff to gather demographic information and to respond to a self-report questionnaire to evaluate their perception of family support.

2.2. Study Participants

Purposive sampling method was used to perform the study which included 206 outpatients, with a confirmed psychiatric diagnosis of schizophrenia, based on the International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10), who were receiving ongoing treatment at the Psychiatric Outpatients Department. Participants had to fulfill the following inclusion and exclusion criteria: (i) being between 18 and 65 years old, (ii) being in a stable psychiatric condition, in clinical remission, and not having been hospitalized or had changes in psychotropic medication or psychosocial status within 90 days before joining the study, (iii) having been hospitalized for psychiatric issues at least twice before (for diagnostic accuracy), iv) having coherent verbal rapport during the completion of data questionnaire. Participants were excluded if they had untreated visual or hearing impairments, neurological disorders or damage to the central nervous system, developmental disabilities, signs of intellectual disability, severe cognitive and neuropsychological impairment, personality disorders, psychotic disorders associated with clinical medical conditions or substance use, substance addiction and history of substance use in the last six months, and a record of current substance or alcohol abuse. Included participants were prior assessed by a physician to determine the presence of any clinically significant or unstable medical disorder or chronic general medical condition. In this sense, patients with past or present cardiovascular disease, chronic lung disease, liver, kidney disease, arthritis or rheumatoid arthritis, autoimmune, blood diseases, diabetes mellitus and/or HbA1C levels above 5.7%, pregnancy or lactation were excluded. Also, any active infectious illness or primary inflammatory disease; current use of corticosteroids or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; recent or ongoing use of warfarin or anticoagulant medications; recent or current use of antidepressants; antibiotics or probiotics in the past three months; urine drug screen positive for psychoactive drugs; smoking habits (more than 1 cigarette per day) and drinking habits (more than 1 unit alcohol per week), were excluded from the study. To confirm the above criteria, upon study enrollment, a thorough health assessment and clinical evaluation were performed.

2.3. Minimal Sample Size Calculation

The sample size calculation for the statistical analysis of the binary logistic regression was carried out using G-Power 3.1 software [

89]. To compute the required sample size, for the most influential independent variable which is BMI, the significance level was set at 0.05, the statistical power at 0.95, R

2 for the other x variables at 0.218 (which is the value calculated by regressing the independent variable of prime interest on all the other independent variables, using multiple linear regression) [

90], selecting the normal distribution type for BMI, with 28.8493 as mean value and 4.86474 as the standard deviation, 1.293 as the odds ratio and the probability of y = 1 under H0 as 0.0000689541, which is estimated by using the formula EXP(B)/(1+EXP(B)), with B being the constant intercept estimate B (see results section). The total sample size determined by this calculation was 115, with the actual power of 0.95, thus the sample size in this study was deemed adequate. G-Power software was also used to verify sample adequacy for moderation analysis. To compute the required sample size, in regression with the R square increase, the significance level was set at 0.05, the statistical power at 0.95, with the number of tested predictors at 1, total number of predictors 3 and the effect size determined with the formula: f

2 = R

2² - R

1²/ 1- R

2²= 0.08. The total sample size determined by this calculation was 152, with the actual power of 0.95, thus the sample size in this study was also deemed adequate.

2.4. Measurement Tools

Participants in this study provided demographic data and clinical information such as age, gender and illness duration.

2.4.1. BMI

BMI measurements were conducted by trained nurse personnel. Based on a standard formula, each participant’s weight (in kilograms) was divided by their height (in squared meters) to determine their BMI. These measurements were performed with the SECA 769, Electronic scale with height measuring rod (SECA, Hamburg, DE). In this way and according to the World Health Organization criteria, the sample was grouped into underweight with BMI<18.5 kg/m2, normal weight with 18.5≤BMI<25 kg/m2, overweight with 25≤BMI<30 kg/m2 and obese participants with BMI≥30 kg/m2.

2.4.2. CRP

Serum CRP levels were determined using a quantitative turbidimetric test (CRP-turbilatex) with the latex agglutination immuno-turbidimetric method. The lowest detectable limits were 0.11mg/dl and the normal reference values were up to 0.6mg/dl, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (SPINREACT 2021, Spain) and the laboratory reference range. The maximum reference level for CRP was set at 1mg/dl because values above this threshold most likely indicate a suspected infection [

91]. The analysis was performed at the clinical biochemistry laboratory of ‘’Sotiria” General Hospital.

2.4.3. Family Support Scale (FSS)

The Greek version of the Family Support Scale is designed to measure the sense of support individuals receive from family members, with whom they reside. The scale is self-administered and includes 13 items on Likert ratings, with 1 denoting 'strongly disagree' to 5 indicating 'strongly agree'. All items revolve around the relationships among cohabiting individuals [

92,

93,

94]. A greater sense of family support is displayed by higher ratings on the scale. People living independently were not required to complete the scale [

92]. Cronbach's alpha for this study’s internal reliability was 0.786.

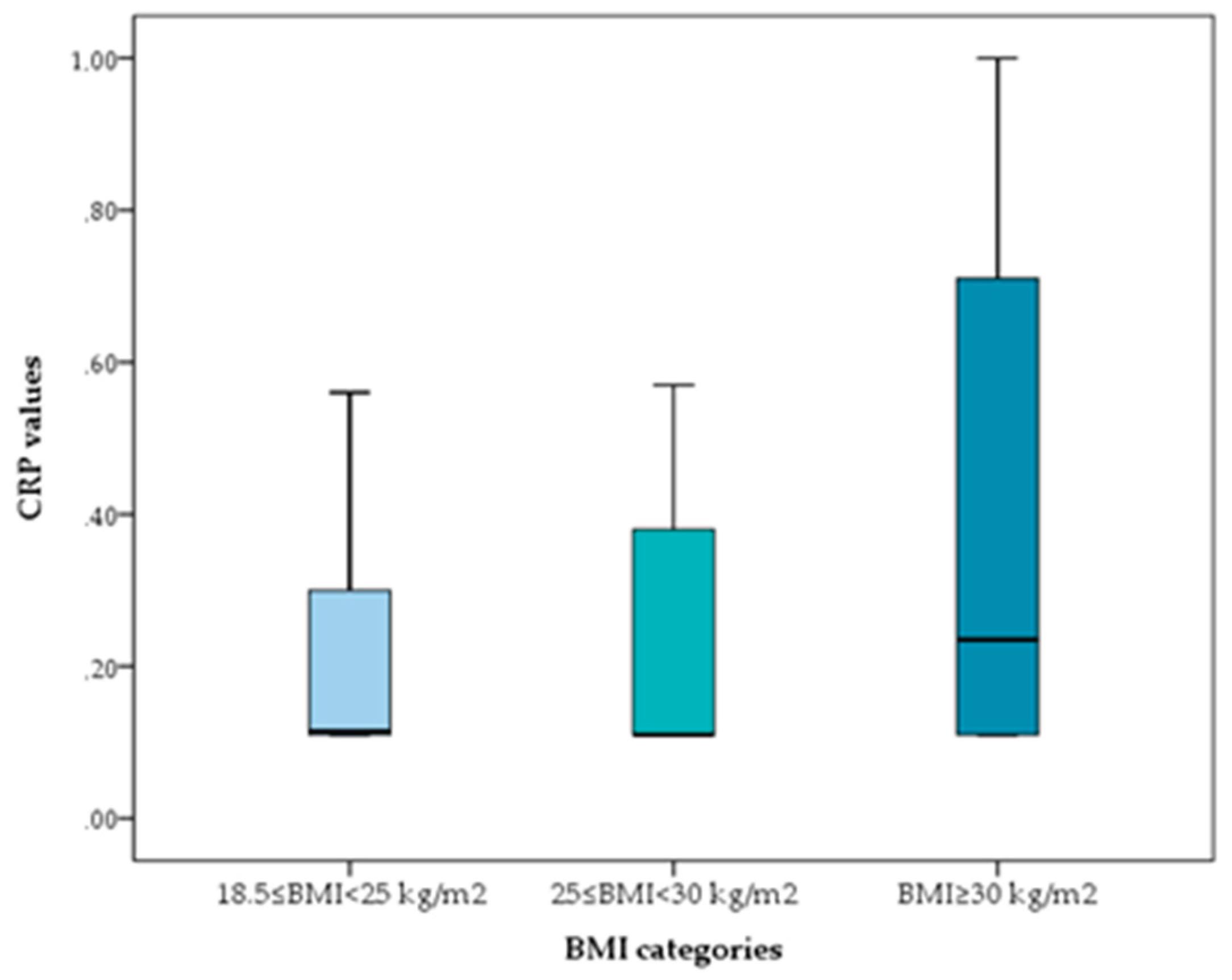

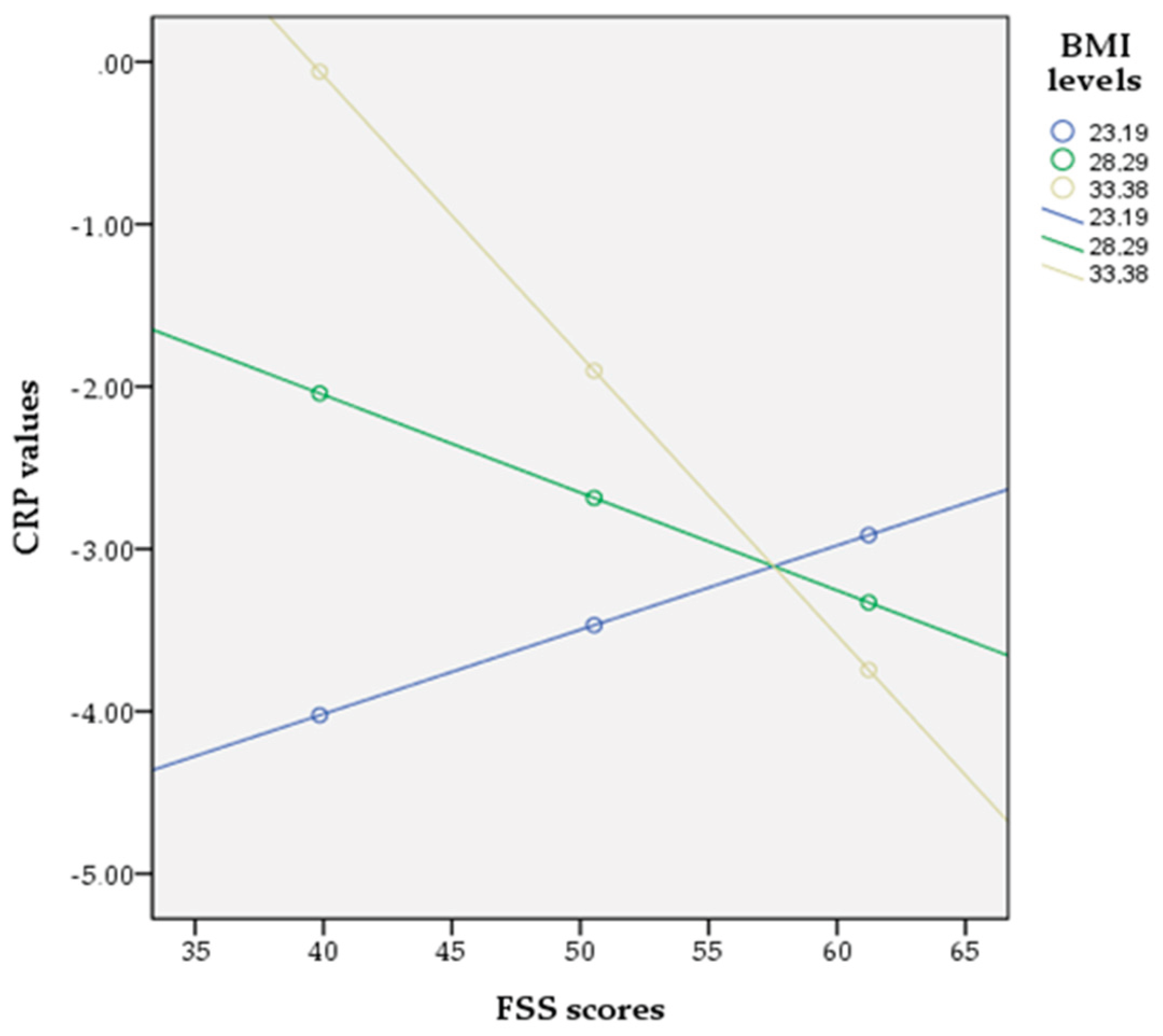

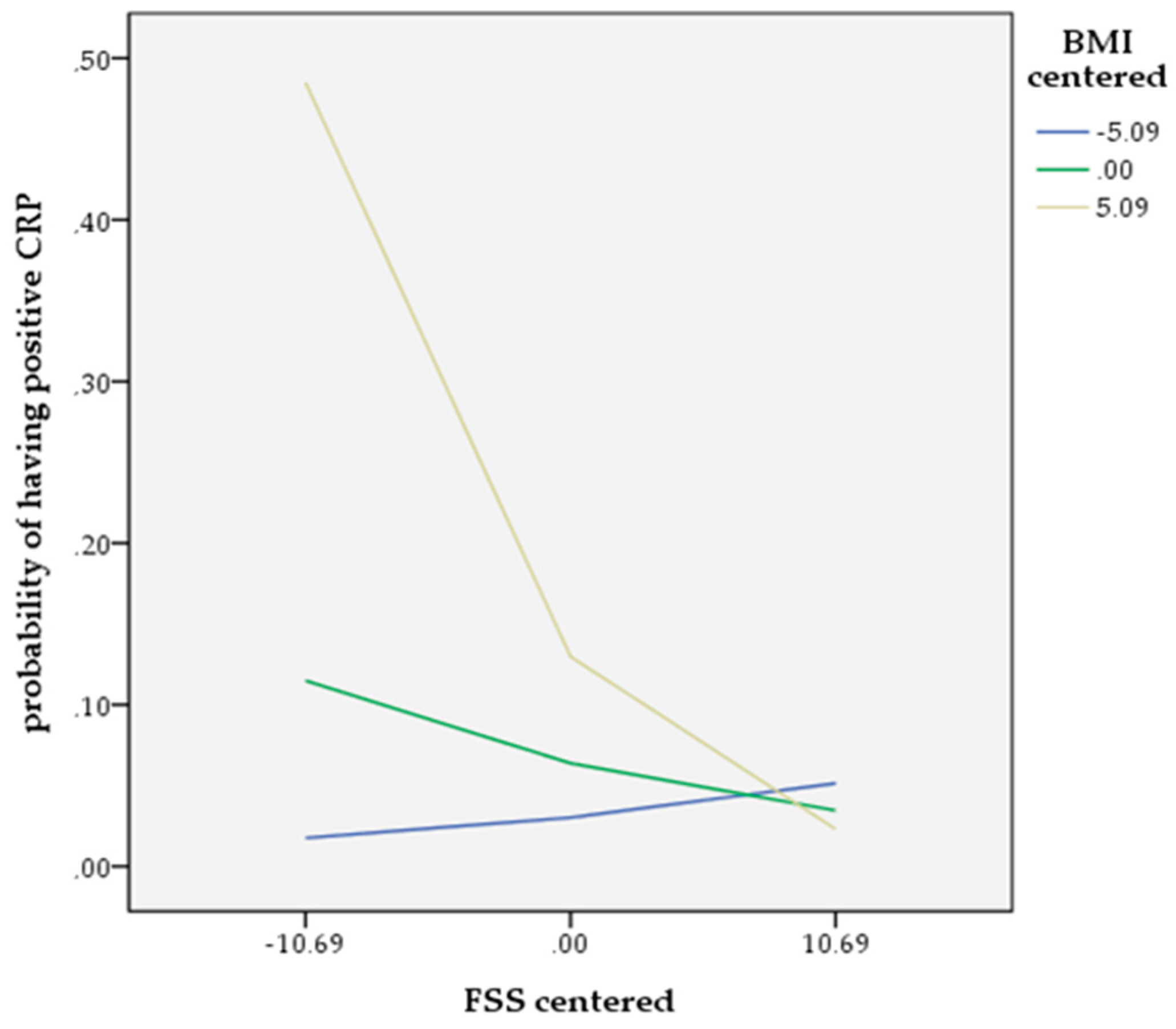

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Initially descriptive analysis was carried out. Means and standard deviations were used to express the continuous variables and percentages were used to report the categorical variables. A Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the distribution of data. Skewed variables (illness duration, BMI and scores on FSS) were transformed to normal with the two-step approach [

95]. The distribution of CRP was markedly rightly-skewed and was thus treated as a non-normally distributed variable which was assessed with non parametric methods. Using the Kruskal-Wallis test, differences in CRP levels across BMI groups were evaluated. The independent samples t-test was employed to compare illness duration, scores on FSS and BMI differences as to gender. To compare CRP values as to gender we used the Mann–Whitney U test. The correlation of continuous variables was done using the Spearman's correlation test for nonparametric bivariate correlations analyses (including CRP) or using Pearson correlations for normally distributed continuous variables (except CRP). Further, CRP was categorized as a dichotomous variable; with detectable but normal CRP values (≥0.11mg/dl) and positive CRP values (>0.6mg/dl). Unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for detectable and positive CRP values for obese participants were estimated using logistic regression. To assess the risk factors of positive CRP values in patients with schizophrenia a binary logistic regression analysis was performed, adjusted for the effects of possible confounding variables (age, gender, illness duration, BMI and scores on FSS). Moderation by BMI was assessed through the introduction of a BMI*FSS interaction term in the logistic regression analysis. Simple slopes analysis was performed using Hayes' SPSS Process Macro Model 1, to report the moderating effect at different levels of BMI. The data analyses were conducted using SPSS software (Version 24.0). For all statistical analyses, statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

4. Discussion

This study investigates the association between perceived family support, circulating CRP and BMI and the results from the correlation analysis, the binary logistic regression and moderation analysis provide strong evidence confirming the research hypotheses. More specifically, concerning the first hypothesis, the positive correlation between circulating CRP and measured BMI and the role of BMI as a risk factor increasing the likelihood of having positive CRP values is consistent with findings from previous studies conducted with participants from the general population and among patients with schizophrenia [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. Most of these studies suggest that the observed correlation between CRP and BMI is attributed to BMI increase, with CRP being an index of elevated adiposity [

45,

47,

48,

96,

97,

98]. In particular, the pathophysiological process in obesity and metabolic dysregulation implicates systemic inflammation through the activation of macrophages in the adipose tissue, which release inflammatory cytokines causing hyperlipidemia and insulin resistance, further worsening the metabolic status, which in turn promotes the production of cytokines by the adipose tissue, thus contributing to chronic inflammation [

99,

100,

101].

The investigation of the second and third research hypotheses produced the main findings of this study which highlight the protective role of perceived family support among outpatients with schizophrenia, being able to counteract the low-grade inflammation by reducing the likelihood of positive CRP values. Most individuals with schizophrenia, due to the disabilities of the disorder, rely on family members who are their primary caregivers. Clinical evidence suggests that the vast majority of patients with schizophrenia are unable to maintain basic social functions and only a minority retain regular employment [

102,

103]. In this sense, the existence of a supportive family network is of outmost importance. Supportive family relationships, beyond safeguarding treatment adherence, may motivate healthy behaviors that promote good health and improve overall well-being. Healthy diet and physical exercise are well known anti-inflammatory factors [

104,

105], frequently encouraged by a protective family environment, whereas pro-inflammatory diets [

106], smoking and/or drug abuse are usually deterred.

Evidence from a large general adult population study documented that social/family strain significantly increased the risk of inflammation and most importantly the association of social/family strain with inflammation was stronger than the relationship of social/family support and inflammation [

107]. These results are in accordance with our findings and provide a plausible explanation for the steeper slope in the relationship between the odds of having positive CRP values and expressing lower than average perceived family support, while a less steep slope accounts for the relationship between the odds of having positive CRP values and scoring above average on the FSS (

Figure 3). Another finding from this study that needs to be clarified is that the protective anti-inflammatory effect of family support is significant only for obese patients. In accordance with other studies with participants from the general population [

108,

109] and among patients with schizophrenia [

28,

52,

110], obese participants in this study were significantly more likely to have positive CRP values compared to non-obese individuals. In these cases, where beyond metabolic complications inflammatory processes have already been established; family support has the ability to attenuate this low-grade inflammation. Yet, because this study is cross-sectional, precluding the direction of causality, these findings could signify that low perceived family support as experienced by patients in strenuous and adverse family backgrounds may have resulted in increased levels of inflammation.

Studies support that greater social strain is linked to higher levels of inflammation [

111,

112]. Meanwhile, a meta-analysis suggested that social support and social integration are significantly associated with lower levels of inflammation [

113,

114]. Research indicates that individuals with schizophrenia have lower perceived social support than those without schizophrenia [

88] and frequently early life adversities force them to withdraw and isolate themselves from other family members [

115]. However, due to the highly prevalent social cognitive deficits among these patients, their families are the main, if not the only, social network [

116]. Their role is to compensate for key social stressors, to protect the emotional health of their vulnerable relatives by combating stigma, enhancing self-esteem and coping strategies, reducing feelings of isolation, increasing social engagement, and promoting a sense of belonging. On the other hand, family strain derived from high levels of expressed emotion, conflictual family relationships, stigma, emotional and financial burdens significantly impact the mental health of individuals with schizophrenia who experience higher levels of distress effectuating increases in pro-inflammatory responses which ultimately lead to poorer treatment outcomes [

117,

118].

As stated, strain from family relationships may play an important role in inflammatory processes, because relationships with family members are likely to last through significant periods of life and are not a matter of choice, as in other relationships. When family relationships are particularly stressful, the need to maintain them over time may increase the strain experienced by these relationships, making family tension detrimental to health, which is manifested through inflammatory processes. In turn, immune dysregulation may lead to the cluster of chronic metabolic disorders [

119]. For instance, research has shown that inflammation can interfere with insulin production and may also cause hypothalamic dysfunction, both of which are involved in weight gain [

120,

121]. Furthermore, changes in lipid and lipoprotein metabolism linked to inflammation lead to raised triglyceride levels and lowered HDL cholesterol synthesis [

122]. From another perspective, the literature suggests that disordered eating behaviours often co-exist with psychotic disorders and social cognitive deficits are particularly prevalent among these patients [

79], rendering them less able to appreciate family support. In addition, research studies have already documented cognitive deficits and related neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with obesity, as well as emotional eating behaviors in an attempt to regulate negative emotions [

81,

123].

More than one third of participants in this study were obese. Findings from other studies among schizophrenic outpatients report comparable or even higher prevalence rates of obesity [

29,

124,

125]. The relationship of schizophrenia and obesity has gained attention due to the high risk of associated comorbidities, such as cardiovascular diseases and metabolic syndrome, increasing all cause morbidity and mortality and reducing life expectancy [

126,

127]. Several studies have reported associations between obesity and negative symptoms, insomnia and night-eating and a decrease in quality if life among individuals with schizophrenia [

128,

129,

130,

131]. An understanding of the clinical factors that predict obesity risk is critical for targeting patients with psychotic disorders who are more prone to weight gain and metabolic syndrome [

132]. Patients with schizophrenia are frequently characterized by lack of control over eating behaviors and are more likely to consume unhealthy foods [

133]. Several risk factors are implicated in these problematic eating behaviors and include tobacco smoking, type 2 diabetes, sleep disturbances, adverse effects of psychotropics, anxiety and depression [

134,

135,

136,

137], and lack of psychosocial rehabilitation [

80,

138].

The above mentioned findings hold practical implications. The fact that obesity and associated metabolic abnormalities are present even in the early stages of psychotic disorders, suggest the need for early interventions. Standard protocols include effective metabolic monitoring guidelines and preventive measures for patients with schizophrenia, especially for patients on psychiatric medications, upon discharge from psychiatric hospitalization and during follow-up [

139,

140]. Lifestyle interventions, dietary manipulation and aerobic physical intervention programs effectuate improvements in addressing obesity and preventing weight gain [

141,

142,

143,

144]. The most important finding from this study supports family involvement during the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [

145] incorporated Family Therapy in clinical guidelines when drafting psychiatric treatment plans, in order to provide psychoeducation, enable families to manage emotions effectively by reducing family strain, improve their communication and problem solving skills [

146,

147].

This study exhibits certain limitations. Due to the cross-sectional design conclusions about the direction of causality cannot be drawn. Moreover, the generalizability of the overall results is limited because it was a single-center study in a specific geographic area. Another drawback was the lack of control sample to compare the laboratory findings, but the aim of this study was to conduct a correlation and not a comparative analysis. Additionally, data on nutrition and activity measures were not available. Similarly, although we had data on the prescribed antipsychotics and knowing about their differential effects on the immune system, the sample size prevented subgroup analysis by antipsychotic types. Also, there were no underweight participants to be included in the study in order to identify possible differences in results as to other participants. Finally, the results of this study might have been influenced by potential confounding factors, such as incidental psychosocial events, or unknown medications administered to participants during the research period.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P., A.T.; methodology, A.P., A.T., E.K,; software, A.T., I.I., A.P.; validation, A.P., A.T., S.B.; formal analysis, A.P., A.T., S.B.; investigation, A.P., A.T.; resources, A.P., N.S., D.K., C.S.; data curation, A.P., D.K., C.S,; writing—original draft preparation, A.P., I.I.; writing—review and editing, A.P., I.I; supervision, A.P., A.T; project administration, A.P., A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript