Submitted:

14 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Proposed Method

2.1. Bayesian Formulation

2.1.1. Likelihood Function

2.1.2. Prior Distribution

2.1.3. Posterior Distribution

2.2. Singularity Treatment

2.3. Posterior Approximation and Reconstruction

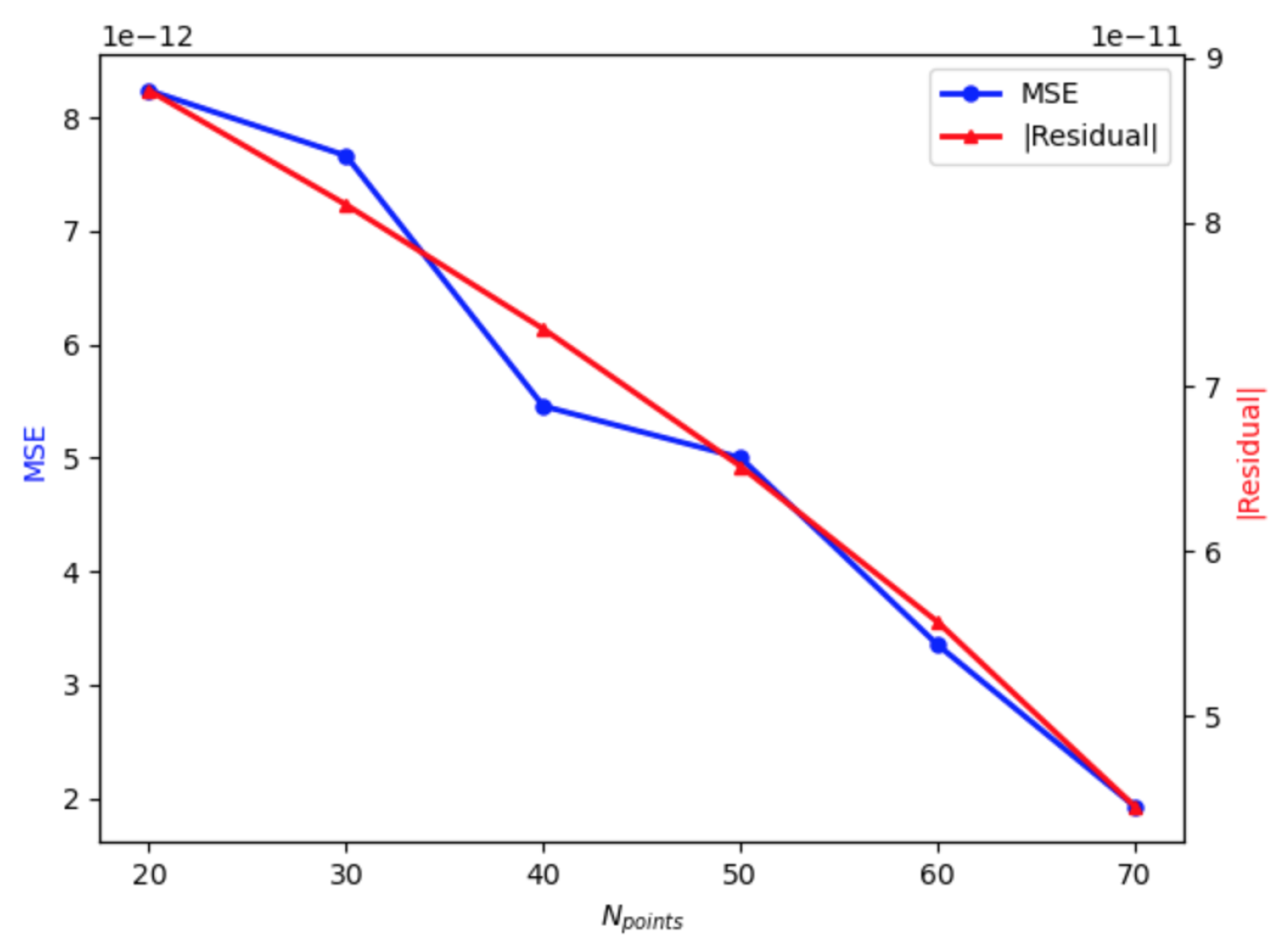

2.3.1. Convergence Assessment

2.3.2. Proposed Algorithm

- Initialization: Set up the GP prior with chosen hyperparameters and discretization grid .

- Prior Sampling: Generate N function samples from the GP prior.

-

Likelihood Evaluation: For each sample :

- Compute using adaptive quadrature with graded mesh transformation

- Apply singularity regularization:

- Evaluate using the likelihood formula

- Weight Computation: Calculate importance weights with log-space stabilization:

-

Posterior Approximation: Normalize weights and compute posterior statistics:

- Posterior mean:

- Posterior variance:

- Reconstruction: Output the posterior mean as the solution estimate along with pointwise credible intervals for uncertainty quantification.

2.4. Convergence and Stability

2.4.1. Monte Carlo Estimation and Stability Analysis

2.4.2. Stability with Respect to Data Perturbations

2.4.3. Minimax Risk Analysis

3. Numerical Examples

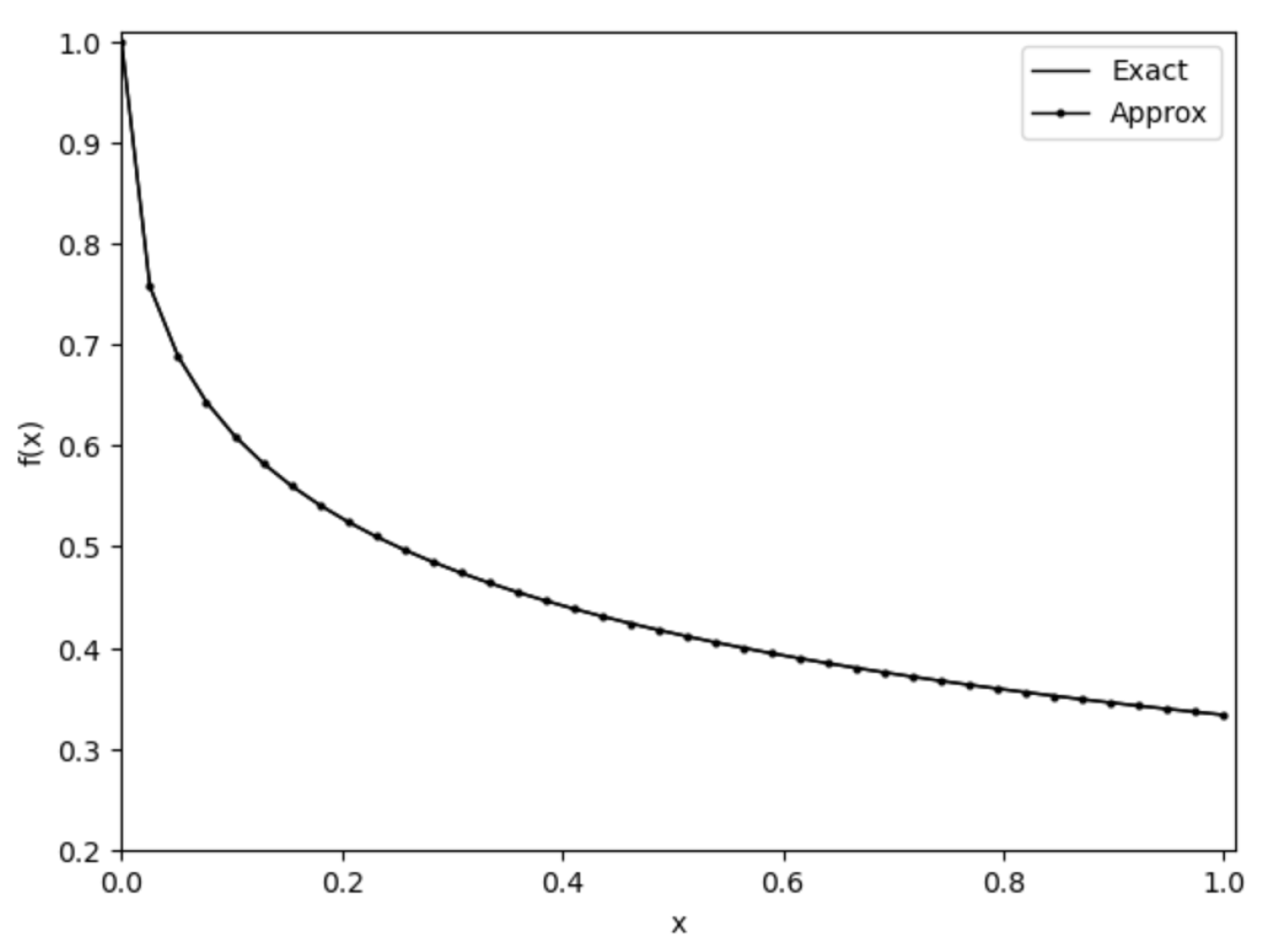

3.1. Example 1: Abel Integral Equation

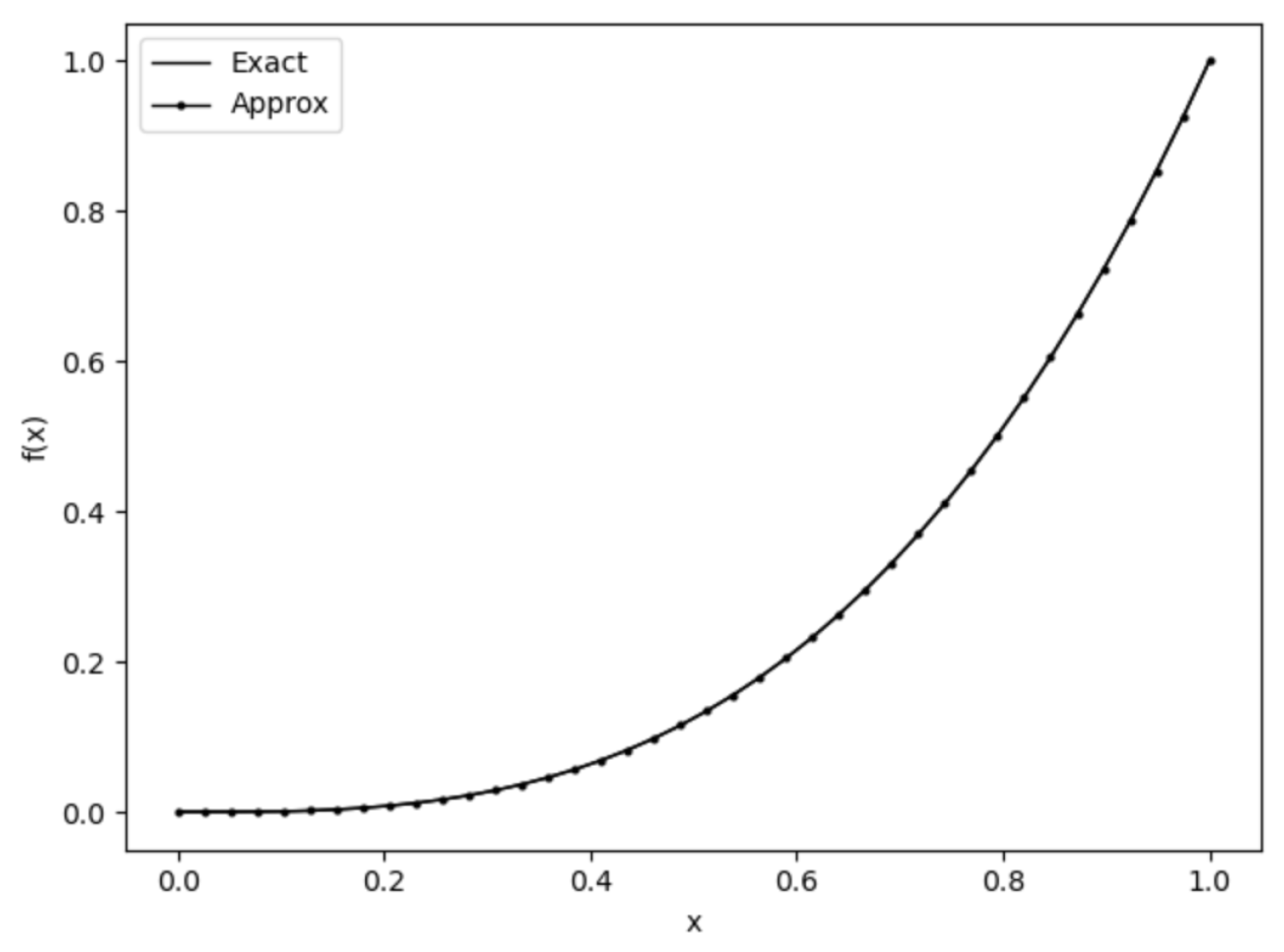

3.2. Example 2: Nonlinear Volterra Equation with Polynomial Right-Hand Side

3.3. Limitations

4. Conclusions

References

- Volterra, V. Leçons sur la théorie mathématique de la lutte pour la vie; Gauthier-Villars, 1931.

- Brunner, H. Volterra Integral Equations: An Introduction to Theory and Applications; Cambridge University Press, 2017.

- Volterra, V. Sulla teoria delle equazioni differenziali lineari. Memorie della Società Italiana delle Scienze 1896, 6, 3–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volterra, V. Leçons sur les équations intégrales et les équations intégro-différentielles; Gauthier-Villars, 1913.

- Lalescu, T. Sur les équations de Volterra. Annali di Matematica Pura ed Applicata 1911, 20, 1–133. [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm, E.I. Sur une classe d’équations fonctionnelles. Acta Mathematica 1903, 27, 365–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbert, D. Grundzüge einer allgemeinen Theorie der linearen Integralgleichungen. Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen 1904, pp. 49–91.

- Wiener, N. Tauberian theorems; Annals of Mathematics, 1931.

- Hopf, E. Ergodentheorie; Springer, 1939.

- Taylor, A.E. Introduction to functional analysis; Wiley, 1958.

- Kato, T. Perturbation theory for linear operators; Springer, 1966.

- Abel, N.H. Solution de quelques problèmes à l’aide d’intégrales définies. Magazin for Naturvidenskaberne 1823, 1, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, H. Collocation Methods for Volterra Integral and Related Functional Differential Equations; Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Gorenflo, R.; Vessella, S. Abel integral equations: analysis and applications; Springer, 1991.

- Tricomi, F.G. Integral equations; Interscience Publishers, 1957.

- Muskhelishvili, N.I. Singular integral equations; Noordhoff, 1953.

- Erdélyi, A. Tables of integral transforms; McGraw-Hill, 1954.

- Arfken, G.B.; Weber, H.J.; Harris, F.E. Mathematical Methods for Physicists; Academic Press, 2013.

- Debnath, L.; Bhatta, D. Integral transforms and their applications; CRC Press, 2014.

- Adomian, G. A review of the decomposition method in applied mathematics. Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications 1988, 135, 501–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomian, G. Solving frontier problems of physics: the decomposition method; Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1994.

- Picard, É. Mémoire sur la théorie des équations aux dérivées partielles et la méthode des approximations successives. Journal de Mathématiques Pures et Appliquées 1890, 6, 145–210. [Google Scholar]

- Press, W.H.; Teukolsky, S.A.; Vetterling, W.T.; Flannery, B.P. Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing; Cambridge University Press, 1986.

- Stoer, J.; Bulirsch, R. Introduction to numerical analysis; Springer, 2002.

- de Boor, C. A practical guide to splines; Springer, 1978.

- Trefethen, L.N. Approximation theory and approximation practice; SIAM, 2013.

- Bownds, J.M.; Wood, B. On Numerically Solving Non-linear Volterra Equations with Fewer Computations. SIAM Journal on Numerical Analysis 1976, 13, 705–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canuto, C.; Hussaini, M.Y.; Quarteroni, A.; Zang, T.A. Spectral methods in fluid dynamics; Springer, 2006.

- Brunner, H.; van der Houwen, P.J. The Numerical Solution of Volterra Equations; North-Holland, 1986.

- Lubich, C. Runge-Kutta theory for Volterra and Abel integral equations of the second kind; Vol. 41, 1983; pp. 87–102.

- Young, A. The numerical solution of integral equations. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London 1954, 224, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, K.E. A survey of numerical methods for the solution of Fredholm integral equations of the second kind; SIAM, 1976.

- Robert, C.P.; Casella, G. Monte Carlo statistical methods; Springer, 2004.

- Higham, N.J. Accuracy and stability of numerical algorithms; SIAM, 2002.

- Dehbozorgi, R.; Nedaiasl, K. Numerical Solution of Nonlinear Abel Integral Equations. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2001.06240. [Google Scholar]

- Ramazanova, M.I.; Gulmanova, N.K.; Omarova, M.T. On solving a singular Volterra integral equation. Filomat 2025, 39, 3647–3656. [Google Scholar]

- Dashti, M.; Stuart, A.M. The Bayesian Approach To Inverse Problems. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1302.6989. [Google Scholar]

- Randrianarisoa, T.; Szabo, B. Variational Gaussian Processes For Linear Inverse Problems. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.00663. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, T.; Teckentrup, A.L.; Zygalakis, K.C. Gaussian processes for Bayesian inverse problems associated with PDEs. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.08343. [Google Scholar]

- Titsias, M. Variational Learning of Inducing Variables in Sparse Gaussian Processes. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2009.

- Brunner, H. Volterra Integral Equations: An Introduction to Theory and Applications; Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Khani, A.; Belalzadeh, N. Numerical solution of volterra integral equations with weakly singular kernel using legendre wavelet method. Mathematics and Computational Sciences 2025, 6, 160–169. [Google Scholar]

- Cardone, A.; Conte, D.; D’Ambrosio, R.; Beatrice, P. Collocation Methods for Volterra Integral and Integro-Differential Equations: A Review. Axioms 2018, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| x | Exact | Approx | Abs Err | Collocation [43] | Abs err | Wavelet [42] | Abs err |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 0.612930 | 0.612933 | 0.608684 | 0.614358 | |||

| 0.2 | 0.528031 | 0.528032 | 0.527864 | 0.527519 | |||

| 0.3 | 0.477326 | 0.477325 | 0.477226 | 0.477342 | |||

| 0.4 | 0.441583 | 0.441582 | 0.441518 | 0.441461 | |||

| 0.5 | 0.414257 | 0.414255 | 0.414214 | 0.414252 | |||

| 0.6 | 0.392310 | 0.392309 | 0.392281 | 0.392246 | |||

| 0.7 | 0.374085 | 0.374083 | 0.374067 | 0.374108 | |||

| 0.8 | 0.358581 | 0.358583 | 0.358570 | 0.358509 | |||

| 0.9 | 0.345146 | 0.345145 | 0.345141 | 0.345250 | |||

| 1.0 | 0.333333 | 0.333333 | 0.333322 | 0.333251 |

| MSE | Max Abs Err | Runtime (s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.01 | 1.425 | ||

| 0.05 | 1.205 | ||

| 0.10 | 1.218 | ||

| 0.20 | 1.186 | ||

| 0.30 | 0.983 | ||

| 0.50 | 1.299 |

| MSE | Max Abs Err | Runtime (s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 1.660 | ||

| 5.0 | 1.726 | ||

| 10.0 | 2.222 | ||

| 15.0 | 2.472 | ||

| 20.0 | 2.165 | ||

| 30.0 | 1.730 |

| C | MSE | Max Abs Err | Runtime (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 1.084 | ||

| 5.0 | 1.006 | ||

| 10.0 | 1.913 | ||

| 15.0 | 1.296 | ||

| 20.0 | 1.735 | ||

| 30.0 | 2.030 |

| x | Exact | Approx | Abs Err | Collocation [43] | Abs err | Wavelet [42] | Abs err |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 0.001017 | 0.001072 | 0.002087 | 0.000956 | |||

| 0.2 | 0.008061 | 0.008061 | 0.012741 | 0.007956 | |||

| 0.3 | 0.027123 | 0.027121 | 0.037091 | 0.026956 | |||

| 0.4 | 0.064189 | 0.064188 | 0.079570 | 0.063956 | |||

| 0.5 | 0.125247 | 0.125247 | 0.144281 | 0.124956 | |||

| 0.6 | 0.216285 | 0.216285 | 0.235123 | 0.215956 | |||

| 0.7 | 0.343291 | 0.343291 | 0.355847 | 0.342956 | |||

| 0.8 | 0.512254 | 0.512254 | 0.510098 | 0.511956 | |||

| 0.9 | 0.729161 | 0.729163 | 0.701431 | 0.728956 | |||

| 1.0 | 1.000000 | 0.999999 | 0.933333 | 0.999956 |

| MSE | Max Abs Err | Runtime (s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.01 | 1.839 | ||

| 0.05 | 0.768 | ||

| 0.10 | 0.970 | ||

| 0.20 | 0.860 | ||

| 0.30 | 0.922 | ||

| 0.50 | 1.181 |

| C | MSE | Max Abs Err | Runtime (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 1.396 | ||

| 5.0 | 0.952 | ||

| 10.0 | 1.608 | ||

| 15.0 | 1.351 | ||

| 20.0 | 0.809 | ||

| 30.0 | 1.915 |

| MSE | Max Abs Err | Runtime (s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 1.563 | ||

| 5.0 | 1.105 | ||

| 10.0 | 1.142 | ||

| 15.0 | 0.880 | ||

| 20.0 | 1.396 | ||

| 30.0 | 2.390 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).