1. Introduction

Older adults living in residential aged care homes experience a multitude of risk factors like comorbidities, concomitant disabilities and age-related immunosenescence [

1]. These factors make them more vulnerable to infections and at increased risk of severe infectious disease, which can result in hospitalisation and death [

1]. Outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases in aged care homes can have major health and economic consequences [

2]. Reducing the burden of vaccine-preventable diseases in Australian aged care homes provides an opportunity to promote positive ageing, prevent suffering and improve quality of life, and is consistent with the Immunization Agenda 2030 that ‘

all people benefit from recommended immunizations throughout the life course, effectively integrated with other essential health services’ [

3].

In Australia the National Immunisation Program (NIP) recommends influenza vaccination for all adults annually; pneumococcal vaccination is funded for people aged 70 years and over, and for those with additional medical risk conditions; and herpes zoster vaccination is funded for people aged 65 years and over and for people with additional medical risk conditions (given as a single dose prior to 1 November 2023) [

4,

5]. These provide protection both to the individual and the community (including other aged care residents) from these diseases. Vaccines on the NIP are provided by the Australian Government for free to people who are eligible for Medicare. However, there are significant barriers to the vaccination of older adults which include access to care, mobility, multiple providers, lack of provider confidence in adult vaccination, and a culture of paediatric-only immunisation [

2]. An additional barrier may be the location of the aged care homes relative to a general medical practice. This impacts on the time to deliver care and has previously been highlighted as a barrier to receiving general practice services in aged care [

6].

The Australian Immunisation Register (AIR) is the national register that records all vaccines administered to all people living in Australia under the NIP, through school programs or privately (such as for influenza or travel) [

7]. For adults, influenza vaccinations have been recorded since March 2021 and other NIP vaccinations since July 2021 [

8]. The data so far show that the uptake of influenza vaccine in Australians aged 65 years or older is 46%, and the uptake of zoster vaccine in the 70 to 79-year age group is 31% [

9]. However, there are currently no reliable data on the uptake of pneumococcal vaccination in older Australians due to the complexity of the dosage regimens [

9]. Further, vaccination figures presented are likely to substantially underestimate true uptake, due to the identification of major gaps between the number of doses distributed and those recorded on AIR [

9].

Even less is known about the vaccination rates of people living in aged care homes. A small study conducted in four aged care homes in Sydney reported an influenza vaccination rate of 84%, however this study was not representative of the Australian aged care population, primarily due to small sample size [

10]. There is no publicly available information regarding uptake of the other recommended vaccines in Australian aged care homes.

The purpose of this study was to determine vaccination rates for influenza, pneumococcal and herpes zoster vaccinations, and to determine if there are any predictors of vaccination uptake for people living in residential aged care facilities.

This article is a revised and expanded version of a paper which was presented at the Communicable Diseases & Immunisation Conference 2025 in Adelaide, South Australia [

11].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This was a retrospective cohort study examining the medical records of residents of 31 aged care facilities in Australia. Data were extracted from the medical records during the period March 2023 to September 2023 (sample selection window), with a look-back period to 1 January 2017. The study was conducted in accordance with legal and regulatory requirements, as well as with scientific purpose, value and rigour and followed generally accepted research practices described in the Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices (GPP) issued by the International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology (ISPE). The study was overseen by internal ethics from Embedded Health Solutions.

2.2. Participants

To be included in the study, participants needed to reside in an Australian registered aged care facility; and be eligible (by age) to receive Australian Government funded vaccinations; and have provided written informed consent. Resident records were excluded if the resident was deceased at the time of data extraction. They were not excluded if they died during the sampling period.

2.3. Variables

Any influenza, pneumococcal or herpes zoster vaccination that was documented in the resident's medical notes during the study period was recorded, regardless of the date of administration of that vaccination. This is important for those vaccinations that are given as ‘once in a lifetime’, or with two doses administered in close succession, without the requirement for booster vaccination.

The data collection timeframe represented a reasonable historical review and coincides with when Australia transitioned from the Australian Childhood Immunisation Register (ACIR) to the AIR, although mandatory recording for vaccines on the NIP was not introduced until 2021. Pneumococcal vaccines (PPV23 or PCV13, or both) and herpes zoster vaccines given at any time were recorded. Influenza vaccines given within the last 2 years only were recorded.

In addition to vaccination status, participant demographics were collected from the resident’s medical record for use in univariate and multivariate modelling. Clinically relevant risk factors or comorbidities that were associated with worse outcomes were chosen. These included age, race, sex, socioeconomic status of the facility location (Socioeconomic Indexes for Areas [SEIFA] decile), geographical region, recent hospitalization (within 30 days), length of stay at the aged care home, comorbidities, smoking and alcohol consumption (drinks/day), and use of oral corticosteroid in the last 3 months [

10,

12,

13]. Chronic steroid use was chosen as a confounding variable as it predisposes residents to viral or bacterial infection due to its immunosuppressive effects. Information on confounders was collected from administrative data available at the residential care home.

All data collected were deidentified. Residential care homes were chosen and intended to represent a maximally diverse, wide demographic sample encompassing socioeconomic, ethnic, religious and other demographic considerations.

The study was not designed to collect safety data. Any adverse events that were detected by the credentialed pharmacist who was assigned to the aged care home on review of medical records were reported as per local practice.

2.4. Statistical Methods

The study planned to include up to 1,500 residents. To reduce bias, random sampling of aged care facilities from 350 aged care homes serviced by Embedded Health Solutions occurred during routine clinical pharmacist medication review visits. Homes were stratified by SEIFA, and then randomly selected using a random allocator, ensuring that homes within each SEIFA category was represented.

Data are summarised descriptively. A univariate logistic regression model was built to examine the influence of SEIFA decile, age at data collection, comorbidity burden, sex, other vaccination status, alcohol consumption, smoking, recent hospitalisation and corticosteroid use on the uptake of vaccination. Covariates that were significant at p<0.20 were entered into a multivariate logistic regression model (

Table 3).

Analyses were conducted using R version 4.0.1 (2020-06-06) and Stata MP v18 for Mac (StataCorp, Texas Station, USA).

This study has been reported according to RECORD-PE [

14].

3. Results

3.1. Participants

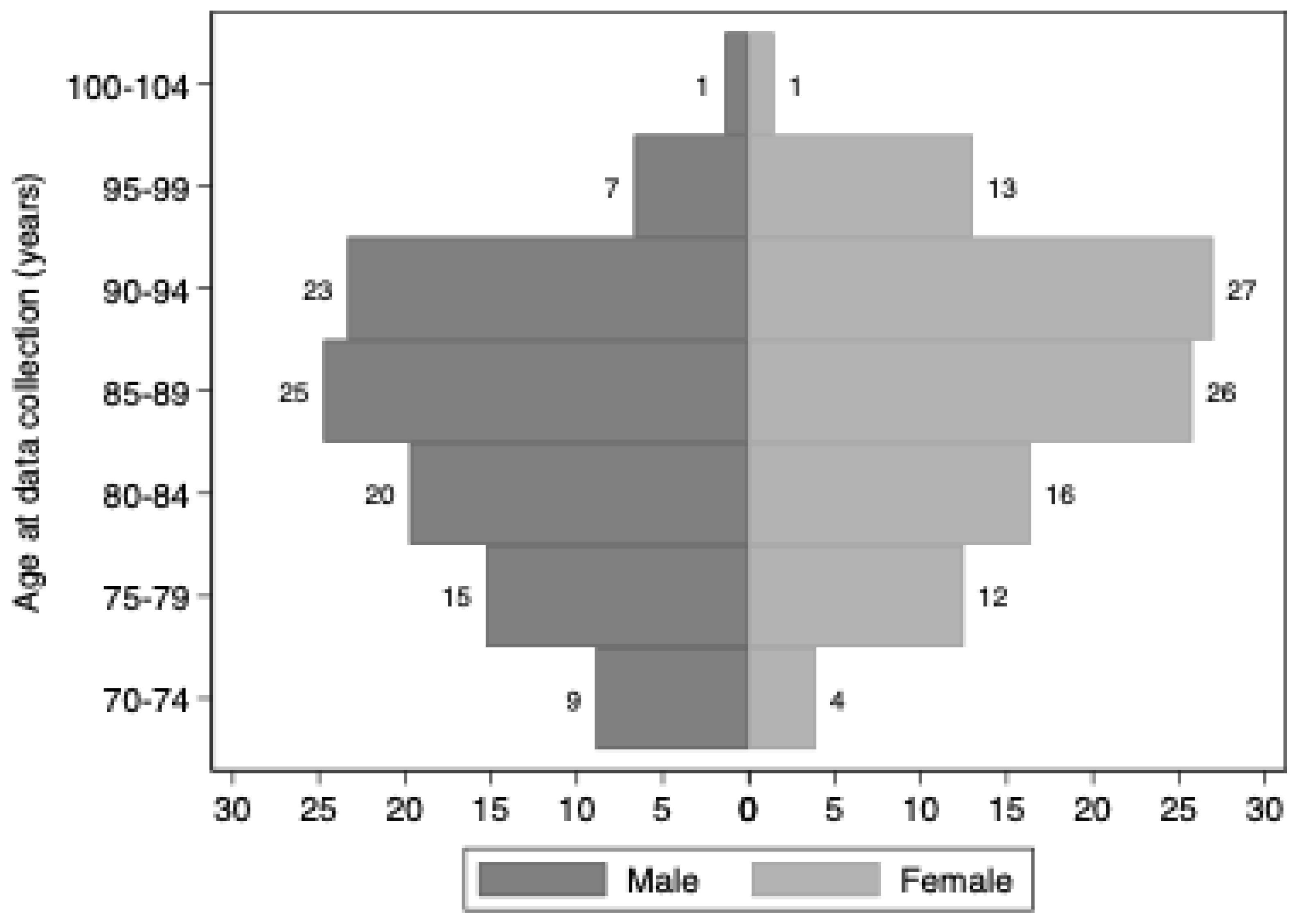

There were 1,108 residents from 31 residential aged care facilities included in the study. Facilities were located in New South Wales (n=10), Victoria (n=7), Queensland (n=7) and South Australia (n=7). Two-thirds (68%) of included residents were female and the median (range) age was 87 years (71 to 107 years) (

Table 1 and

Appendix A,

Figure A1).

Residents in NSW were considered the most disadvantaged, and those in Victoria, the most advantaged (

Table 1). Just over 1 in 10 had used corticosteroids in the last 3 months, but rates were higher in Victoria, at 19.2%. Approximately 8% had been hospitalised in the last 30 days (

Table 1).

All residents had one or more comorbidities. The most commonly reported comorbidities were mental and behavioural disorders (927/1108, 83.7%), diseases of the circulatory system (924/1108, 83.4%), and diseases of the musculoskeletal and connective tissue (802/1108, 72.6%). Respiratory conditions, including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or bronchiectasis affected 262 residents (23.6%). The median number of comorbidities was 10 (range 3, 30).

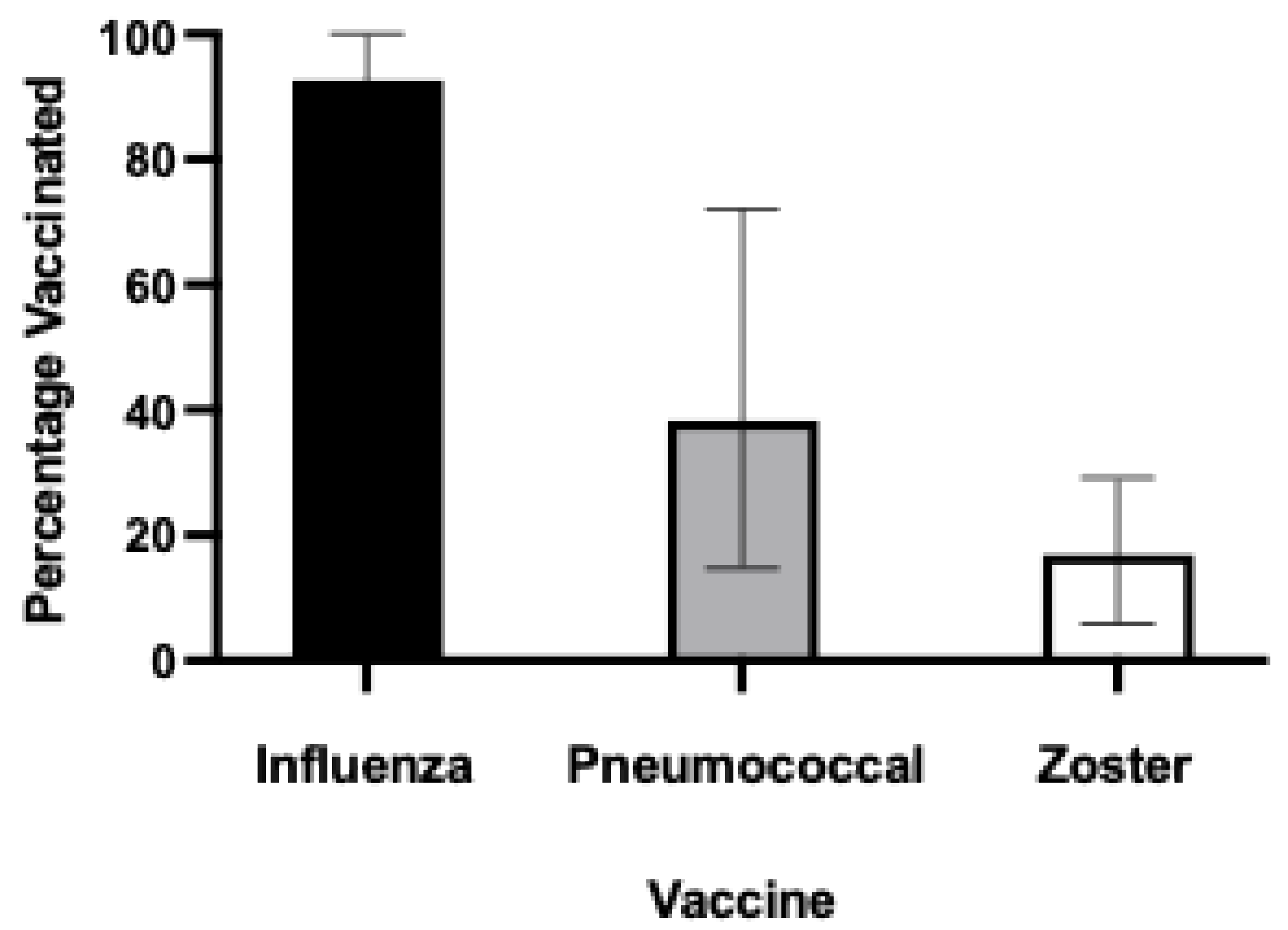

3.2. Vacination Rates

Overall, 1026 / 1108 (92.6%) aged care residents had received an influenza vaccine within the prior two years (

Table 2 and

Figure 1). However, the rate of uptake of other recommended vaccinations was much lower – only 424 (38.3%) had ever received a pneumococcal vaccine and 184 residents (16.8%) had ever received herpes zoster vaccination. Only 11.5% of the residents had received all three vaccines, with 31.5% receiving two vaccines, and 50.1% receiving one of the vaccines. Just under 7% had received no vaccinations at all. There was a difference in vaccine uptake by state, with zoster vaccination less likely in Victoria, and pneumococcal vaccination less likely in NSW or Victoria compared to other states (

Table 2). While there was no difference in vaccination rates by the number of reported comorbidities for influenza vaccine and zoster vaccine, those with higher numbers of comorbidities were more likely to receive vaccination (HR 1.03, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.06, p=0.04).

3.3. Univariate

Significant variables in the univariate model (at p<0.20) for influenza vaccination included SEIFA decile, pneumococcal vaccination status, zoster vaccination status, alcohol use, recent hospitalisation and corticosteroid use (

Table 3). There was no difference in vaccination rates by sex. Specifically, for every 1 unit increase in SEIFA decile, the odds of receiving an influenza vaccine were 9% lower (OR 0.91; CI 0.84 to 0.98). If a resident had received a pneumococcal vaccine, they were more than 10 times more likely to have also received an influenza vaccine (OR 10.63; 95% CI 4.27 to 26.49). Similarly, if a resident had received a herpes zoster vaccine, they were nearly 9 times more likely to have also received an influenza vaccine (OR 8.77; 95% CI 2.14 to 36.01).

Significant variables in the univariate logistic regression models for pneumococcal vaccination uptake (at p<0.20) were age, influenza vaccination status, and zoster vaccination status (

Table 3). There was no difference in vaccination rates by sex. If a resident had been vaccinated for influenza, they were more than 10 times more likely to have also received a pneumococcal vaccine (OR 10.63; 95% CI 4.27, 26.49) and if a resident had received a herpes zoster vaccine, they were five times more likely to have also received a pneumococcal vaccine (OR 5.01; 95% CI 3.55, 7.08).

Significant variables in the univariate logistic regression model for herpes zoster vaccination uptake (at p<0.20) were SEIFA decile, age, sex, influenza vaccination status, pneumococcal vaccination status, alcohol use, and hospitalisation in the last month (

Table 3). The strongest predictors of herpes zoster vaccination were younger age and having received a pneumococcal vaccine.

Corticosteroid use did not seem to influence pneumococcal or zoster vaccination rates.

Table 3.

Univariate and Multivariate Modelling.

Table 3.

Univariate and Multivariate Modelling.

| Model |

|

Univariate |

|

|

Multivariate |

|

| Covariate |

Influenza

n=1,108 |

Pneumococcal

n=1,108 |

Herpes zoster

n=1,108 |

Influenza

n=990* |

Pneumococcal

n=1,094* |

Herpes zoster

n=990* |

| SEIFA decile |

OR 0.91

[95%CI 0.84, 0.98]

p=0.013 |

OR 1.00

[95%CI 0.96 1.04]

p=0.846 |

OR 0.94

[95%CI 0.89, 1.00]

p=0.038 |

OR 0.93

[95%CI 0.85, 1.00]

p=0.062 |

- |

OR 0.95

[95%CI 0.89, 1.01]

p=0.095 |

| Age (years) |

OR 1.00

[95%CI 0.97, 1.03]

p=0.955 |

OR 0.98

[95%CI 0.97, 1.00]

p=0.052 |

OR 0.88

[95%CI 0.86, 0.91]

p<0.001 |

- |

OR 1.01

[95%CI 0.99, 1.03]

p=0.348 |

OR 0.88

[95%CI 0.85, 0.90]

p<0.001 |

| Gender |

OR 1.02

[95%CI 0.63, 1.65]

p=0.930 |

OR 1.11

[95%CI 0.85, 1.43]

p=0.447 |

OR 0.77

[95%CI 0.56, 1.07]

p=0.123 |

- |

- |

- |

| Influenza vaccination |

- |

OR 10.63

[95%CI 4.27, 26.49]

p<0.001 |

OR 8.77

[95%CI 2.14, 36.01]

p=0.003 |

- |

OR 8.60

[95%CI 3.43, 21.56]

p<0.001 |

OR 10.19

[95%CI 1.36, 76.32]

p=0.024 |

| Pneumococcal vaccination |

OR 10.63

[95%CI 4.27, 26.49]

p<0.001 |

- |

OR 5.01

[95%CI 3.55, 7.08]

p<0.001 |

OR 14.35

[95%CI 4.46, 46.13]

p<0.001 |

- |

OR 4.44

[95%CI 3.01, 6.55]

p<0.001 |

| Herpes zoster vaccination |

OR 8.77

[95%CI 2.14, 36.01]

p=0.003 |

OR 5.01

[95%CI 3.55, 7.08]

p<0.001 |

- |

OR 8.73

[95%CI 1.18, 64.36]

p=0.033 |

OR 4.85

[95%CI 3.36, 7.01]

p<0.001 |

- |

| Alcohol use |

OR 0.58

[95%CI 0.32, 1.03]

p=0.076 |

OR 1.18

[95%CI 0.81, 1.70]

p=0.387 |

OR 1.65

[95%CI 1.06, 2.57]

p=0.026 |

OR 0.51

[95%CI 0.27, 0.97]

p=0.039 |

- |

OR 1.62

[95%CI 0.97, 2.69]

p=0.065 |

| Hospitalization in last 30 days |

OR 0.61

[95%CI 0.30, 1.23]

p=0.165 |

OR 0.79

[95%CI 0.50, 1.25]

p=0.316 |

OR 0.47

[95%CI 0.22, 0.98]

p=0.044 |

OR 0.64

[95%CI 0.29, 1.38]

p=0.253 |

- |

OR 0.53

[95%CI 0.24, 1.19]

p=0.122 |

| Corticosteroid use in last 3 months |

OR 1.79

[95%CI 0.76, 4.19]

p=0.181 |

OR 1.12

[95%CI 0.77, 1.62]

p=0.555 |

OR 0.99

[95%CI 0.61, 1.61]

p=0.960 |

OR 1.59

[95%CI 0.66, 3.84]

p=0.306 |

- |

- |

3.4. Multivariate

In the multivariate logistic regression model for influenza vaccine uptake those with pneumococcal vaccination were 14.4 times more likely, and those with herpes zoster vaccination were 8.7 times more likely, to receive influenza vaccination than those who had not received these other vaccinations. Residents who consume alcohol were 49% less likely to receive influenza vaccination (

Table 3).

In the multivariate logistic regression model for pneumococcal uptake those who had received influenza vaccination or herpes zoster vaccination were 8.6 times and 4.9 times more likely to have also received pneumococcal vaccination (

Table 3).

In the multivariate logistic regression model for herpes zoster vaccination for every year increase in age, residents were 12% less likely to have received herpes zoster vaccination. However, residents who had received influenza vaccination or pneumococcal vaccination were 10.2 times or 4.4 times more likely to have also received herpes zoster vaccination, respectively (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

Of the 1,108 residents from a broad cross-section of Australian aged care facilities reviewed, 1026 (92.6%) had received influenza vaccination in the past two years. Only 424 (38.3%) had ever received a pneumococcal vaccine, and 184 residents (16.8%) had ever received herpes zoster vaccination. Our findings are supported by Victorian data from 2022, which showed the median uptake for influenza, pneumococcal and herpes zoster vaccines was 86.8%, 32.8% and 19.3% respectively [

15].

In all the multivariate models in our study, receipt of another vaccination was a significant predictor for vaccination. Our analysis might suggest that vaccine use is behavioural and receiving one vaccine reflects willingness to receive multiple vaccines. Alternatively, it may be related to the aged care home’s or GP’s motivation, behaviours, or practices and policies. As such, low rates of vaccination for pneumococcal disease or herpes zoster, despite willingness to receive influenza vaccine highlights an opportunity for programs to increase awareness of the availability and benefits of these recommended vaccines under the NIP. Accredited Clinical Pharmacists are well placed to lead such a program in Australian aged care, as they are credentialled to immunise. The Australian Government ‘My Health Record’ now includes a direct link to the Australian Immunisation Register to obtain the immunisation status of an individual, which facilitates further audits of vaccination status.

Interestingly, socioeconomic decile was not significant in any of the multivariate regression models, despite its association in univariate model influenza and herpes zoster vaccination, with more disadvantaged and more remote residents more likely to receive vaccination. The reasons for this are unclear, but suggest there may be interactions between SEIFA decile and other explored and non-explored covariates. Elsewhere, higher socioeconomic status is positively associated with vaccine uptake in the elderly [

16]. In other regions of the world greater influenza vaccine uptake has been reported in female residents, and those who did not smoke; but also reported significant variability in uptake by facility [

17]. Other reasons cited in the literature for poor uptake of recommended vaccinations in the general population include poor health literacy, a lack of understanding of the criteria for receiving immunisations, general practitioners (GPs) not having a reminder system in place for eligible patients, low awareness of personal susceptibility, perceived side effects, and lack of awareness of a residents’ vaccination status [

18,

19,

20].

The apparent willingness for aged care residents to be vaccinated, is evidenced by the high uptake rates for the influenza vaccine. However, there needs to be a campaign to raise awareness as to the benefits of being vaccinated against pneumococcal disease and herpes zoster for the older population. In the general population, over the 3-year period from 2014-2016 there were 10,613 hospitalisations and 337 deaths related to influenza, 2,219 hospitalisations and 20 deaths for invasive pneumococcal disease and for shingles an average of 2,473 hospitalisations and 28 deaths per year [

21]. Given this burden, it is important that the barriers and facilitators to vaccine uptake are urgently explored and addressed, particularly on how to operationalise pneumococcal and herpes zoster vaccinations in this setting. In addition, better surveillance of vaccine preventable infections, such as that has been implemented in Victoria [

22], may improve awareness, and highlight the importance of vaccination in this vulnerable population.

There are solutions. Firstly, vaccination of the elderly needs not to be viewed with the same lens as childhood vaccination: there are important differences in immune system functioning between children and the elderly; as there are with regards to vaccine efficacy [

23]. Once this paradigm shift has occurred, it opens avenues for implementing novel programs that increase vaccine uptake. For example, GP software programs could include capacity to identify eligible patients for these, and other vaccines. It may also be prudent to trial an intervention where residents and their families are informed of the benefit of recommended vaccinations; and then offered on-site vaccination, perhaps via a community pharmacy which supplies medications to the aged care facilities; or as part of a wider resident and employee vaccination program. Employee vaccination programs must also be considered to protect vulnerable residents in aged care, especially given that outbreaks are usually linked with the pathogen being introduced to the facility from employees or visitors [

24]. This is also important given the low influenza vaccination uptake by aged care workers (especially in the pre-COVID-19 era) [

25]. Pharmacist-led employee vaccination programs have been successful in improving vaccination rates for aged care health workers [

26], although whether such programs serve to prevent vaccine-preventable disease in residents, is still a matter of debate [

27].

Our study has several limitations. Data were collected from several sources. Possible explanations for missing records of vaccination include lack of documentation in the handover letter to the aged care home, residents being unaware as to their vaccination status, and information not being recorded on the AIR before it was made a mandatory requirement. The presumption was made that if it was not recorded in any of those sources, then the vaccine had not been given. Therefore, rates of vaccination may be underestimated, particularly for vaccines that are given infrequently (for example, pneumococcal and herpes zoster vaccines). Further, data collection for this study occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, when awareness of and uptake of the influenza vaccine was high [

28]. Vaccine uptake was being strongly encouraged for all aged care residents, and reporting of influenza vaccination is mandatory. This may partially explain the very high proportion of aged care residents vaccinated against influenza.

5. Conclusions

These data show that while there is high uptake of influenza vaccines, there is a low uptake of both pneumococcal and herpes zoster vaccine in residents of aged care facilities. Further research into the barriers and enablers of vaccine uptake should be undertaken, with the goal of increasing vaccination uptake in this vulnerable population.

Author Contributions

All authors have made a substantial contribution to the conception or design of the work, or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; and have assisted in drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content; and have provided final approval of the version to be published. Finally, all authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work, and will ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This was a quality improvement program which did not require formal ethical approval under the National Health and Medical Research Council’s Ethical Considerations in Quality Assurance and Evaluation Activities, however oversight was provided by internal ethics at Ward Medication Management (Ward Medication Management is now known as Embedded Health Solutions). Only deidentified information was collected.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, SW, following appropriate ethical review and approval. The data are not publicly available as participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Ardi Mirzaei, School of Pharmacy, The University of Sydney for his suggestions on the manuscript. The authors thank Belinda Butcher BSc(Hons) MBiostat PhD CMPP AStat of WriteSource Medical Pty Ltd, Sydney, Australia, for providing medical writing support funded by Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP2022) guidelines (

https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M22-1460); and for conducting additional statistical analyses associated with this project.

Conflicts of Interest

SW and YL are employees of Pfizer, who manufacture Prevenar 13 and Prenevar 20 vaccines. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACIR |

Australian Childhood Immunisation Register |

| AIR |

Australian Immunisation Register |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| GP |

General Practitioner |

| GPP |

Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices |

| ISPE |

International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology |

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| NIP |

National Immunisation Program |

| OR |

Odds Ratio |

| SEIFA |

Socioeconomic Indexes for Areas |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Age distribution of included residents by sex.

Figure A1.

Age distribution of included residents by sex.

References

- Hashan, M.R., et al., Protocol on establishing a prospective enhanced surveillance of vaccine preventable diseases in residential aged care facilities in Central Queensland, Australia: an observational study. BMJ Open, 2022. 12(6): p. e060407. [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, R.C., et al., Equity in disease prevention: Vaccines for the older adults - a national workshop, Australia 2014. Vaccine, 2016. 34(46): p. 5463–5469. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, Immunization Agenda 2030. Available from https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/immunization/strategy/ia2030/ia2030-draft-4-wha_b8850379-1fce-4847-bfd1-5d2c9d9e32f8.pdf?sfvrsn=5389656e_69&download=true. 2020.

- Department of Health and Aged Care. National Immunisation Program Schedule. 2023 [cited 2024 26 March]; Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/topics/immunisation/when-to-get-vaccinated/national-immunisation-program-schedule.

- Department of Health and Aged Care. Australian Immunisation Handbook. Available from https://immunisationhandbook.health.gov.au/. 2022 [cited 2024 4 July]; Available from: https://immunisationhandbook.health.gov.au/.

- Hillen, J.B., A. Vitry, and G.E. Caughey, Trends in general practitioner services to residents in aged care. Aust J Prim Health, 2016. 22(6): p. 517–522. [CrossRef]

- Services Australia. Australian Immunisation Register. What the register is. Available from https://www.servicesaustralia.gov.au/what-australian-immunisation-register?context=22436. 2022 [cited 2024 26 March]; Available from: https://www.servicesaustralia.gov.au/what-australian-immunisation-register?context=22436.

- Department of Health and Aged Care. Using the Australian Immunisation Register. Available from https://www.health.gov.au/topics/immunisation/immunisation-information-for-health-professionals/using-the-australian-immunisation-register#mandatory-reporting. 2024 [cited 2024 26 March]; Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/topics/immunisation/immunisation-information-for-health-professionals/using-the-australian-immunisation-register#mandatory-reporting.

- Hull, B., et al., Exploratory analysis of the first 2 years of adult vaccination data recorded on AIR. 2019, National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance (NCIRS).

- Tan, H.Y., et al., Prevalence and predictors of influenza vaccination among residents of long-term care facilities. Vaccine, 2019. 37(43): p. 6329–6335. [CrossRef]

- Wiblin, S. and N. Soulsby, Vaccination in aged care: a study of influenza, zoster & pneumococcal vaccination, in Communicable Diseases & Immunisation Conference 10 to 12 June 2025. Adelaide, South Australia.

- Ridda, I., et al., Predictors of pneumococcal vaccination uptake in hospitalized patients aged 65 years and over shortly following the commencement of a publicly funded national pneumococcal vaccination program in Australia. Hum Vaccin, 2007. 3(3): p. 83–6. [CrossRef]

- Frank, O., et al., Pneumococcal vaccination uptake among patients aged 65 years or over in Australian general practice. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2020. 16(4): p. 965–971. [CrossRef]

- Langan, S.M., et al., The reporting of studies conducted using observational routinely collected health data statement for pharmacoepidemiology (RECORD-PE). BMJ, 2018. 363: p. k3532. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N., et al., An evaluation of influenza, pneumococcal and herpes zoster vaccination coverage in Australian aged care residents, 2018 to 2022. Infect Dis Health, 2023. 28(4): p. 253–258. [CrossRef]

- Okoli, G.N., et al., Determinants of Seasonal Influenza Vaccine Uptake Among the Elderly in the United States: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gerontol Geriatr Med, 2019. 5: p. 2333721419870345. [CrossRef]

- Mulla, R.T., et al., Prevalence and predictors of influenza vaccination in long-term care homes: a cross-national retrospective observational study. BMJ Open, 2022. 12(4): p. e057517. [CrossRef]

- Lorini, C., et al., Health Literacy, Vaccine Confidence and Influenza Vaccination Uptake among Nursing Home Staff: A Cross-Sectional Study Conducted in Tuscany. Vaccines (Basel), 2020. 8(2). [CrossRef]

- Eilers, R., P.F. Krabbe, and H.E. de Melker, Factors affecting the uptake of vaccination by the elderly in Western society. Prev Med, 2014. 69: p. 224–34. [CrossRef]

- Kan, T. and J. Zhang, Factors influencing seasonal influenza vaccination behaviour among elderly people: a systematic review. Public Health, 2018. 156: p. 67–78. [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, The burden of vaccine preventable diseases in Australia. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Watson, E., et al., Evaluation of an Infection surveillance program in residential aged care facilities in Victoria, Australia. BMC Public Health, 2024. 24(1): p. 254. [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, C.R., Elderly vaccination—The glass is half full. Health, 2013. 05(12): p. 80–85. [CrossRef]

- Guy, R.J., et al., Influenza outbreaks in aged-care facilities: staff vaccination and the emerging use of antiviral therapy. Med J Aust, 2004. 180(12): p. 640–2. [CrossRef]

- Lai, E., et al., Influenza vaccine coverage and predictors of vaccination among aged care workers in Sydney Australia. Vaccine, 2020. 38(8): p. 1968–1974. [CrossRef]

- McDerby, N.C., et al., Pharmacist-led influenza vaccination services in residential aged care homes: A pilot study. Australas J Ageing, 2019. 38(2): p. 132–135. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.E., T. Jefferson, and T.J. Lasserson, Influenza vaccination for healthcare workers who care for people aged 60 or older living in long-term care institutions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2016. 2016(6): p. CD005187. [CrossRef]

- Beard, F., A. Hendry, and K. Macartney, Influenza vaccination uptake in Australia in 2020: impact of the COVID-19 pandemic? Commun Dis Intell, 2021. 45. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).