1. Introduction

CVD accounts for the highest mortality worldwide [

1]. While a major body of research focuses on how to best treat patients with established CVD, we must also prioritize prevention, which would benefit both our patients and healthcare system [

2].

A major subject with implications in the development and progression of CVD is nutrition [

3]. Unfortunately, this field lacks sufficient clarity, and many studies continue to contradict previous evidence [

4]. This is largely because much of the research relies on observational studies based on food questionnaires, which are highly prone to subject bias and depend heavily on self-recall. High-quality studies, such as clinical trials, are scarce and also difficult to implement in this context due to the costs and the challenge of maintaining adherence to a specific dietary pattern over a sufficiently long period [

5].

When we think of foods associated with CVD, we typically consider those high in saturated fats, cholesterol, and, more broadly, animal-based products, especially when consumed in excess [

6]. Historically, it was assumed that these components were responsible for the associations observed in numerous studies. However, while some research has contradicted the role of saturated fats and dietary cholesterol, more recent studies have revealed an entirely different perspective—one shaped by the gut microbiota [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Could the gut microbiome represent the missing link between animal-based foods and CVD? For decades, we overlooked the bidirectional relationship between food and the gut microbiome. Studies investigating the connection between diet, the microbiome, and gastrointestinal disorders have confirmed that this field represents a valuable area of research [

11]. While the connection between food and gut bacteria was somewhat anticipated due to their local interactions, the discovery of clear links between the gut microbiome, its metabolites, and the functioning of organs beyond the gastrointestinal system was a completely new concept [

12].

Gut dysbiosis has been associated with inflammatory, autoimmune, oncologic, cardiovascular, endocrine, neurological, and even psychiatric disorders [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Time and time again, this myriad of organisms has surprised us, influencing physiological processes that do not necessarily have a direct connection with the gastrointestinal tract. Microorganisms do not just passively reside in the intestines—they are actively involved in the digestion of undigested food, producing metabolites [

20]. While individual strains of bacteria might have specific functions, in general, changes in the microbiome influence homeostasis through these gut-derived metabolites [

21]. Beneficial bacteria are associated with increased production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and decreased production of trimethylamine (TMA), while harmful bacteria are associated with the opposite [

20,

22,

23].

The aim of this review is to contribute to a better understanding of the complex relationship between the gut microbiome and CVD through the lens of TMAO, a gut metabolite. Understanding this relationship may enable the use of gut metabolites such as TMAO to assess the microbial composition of individuals and also as a potential biomarker for CVD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Strategy

Keywords such as “gut microbiome,” “TMAO,” “cardiovascular disease,” “hypertension,” “metabolic diseases,” “atherosclerosis,” “heart failure,” and their combinations were used to conduct a comprehensive search across databases including PubMed and Google Scholar, as well as journals such as MDPI, the American Heart Journal, ScienceDirect, and Frontiers. Both animal and human studies published within the last ten years were included to ensure the novelty of the research, with the timeframe extended in a few cases to incorporate studies offering valuable insights into underexplored factors. The first section of this review presents information on TMAO biochemistry and its involvement in the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying CVD, while the second section explores specific associations between TMAO levels and individual cardiovascular conditions. This review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines.

References were organized using Zotero, and artificial intelligence tools were employed to check grammar and ensure clarity and coherence of the text.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Study selection was conducted according to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Only peer-reviewed studies addressing TMAO, the gut microbiome, and CVD were considered. Exclusion criteria included non-peer-reviewed sources, duplicate publications, and those with incomplete data. Also, studies with major limitations and older than the specified period that did not provide additional information were excluded.

2.3. Study Selection

The initial search generated 3,793 results. After screening titles and abstracts, 106 studies were selected for inclusion based on their relevance and novelty. However, certain key information remained absent. To fill these gaps, the search timeframe was extended by six years (2009–2025), leading to the addition of eight more studies, the earliest of which being published in 2009.

3. Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO)

3.1. Origin and Metabolism of TMAO

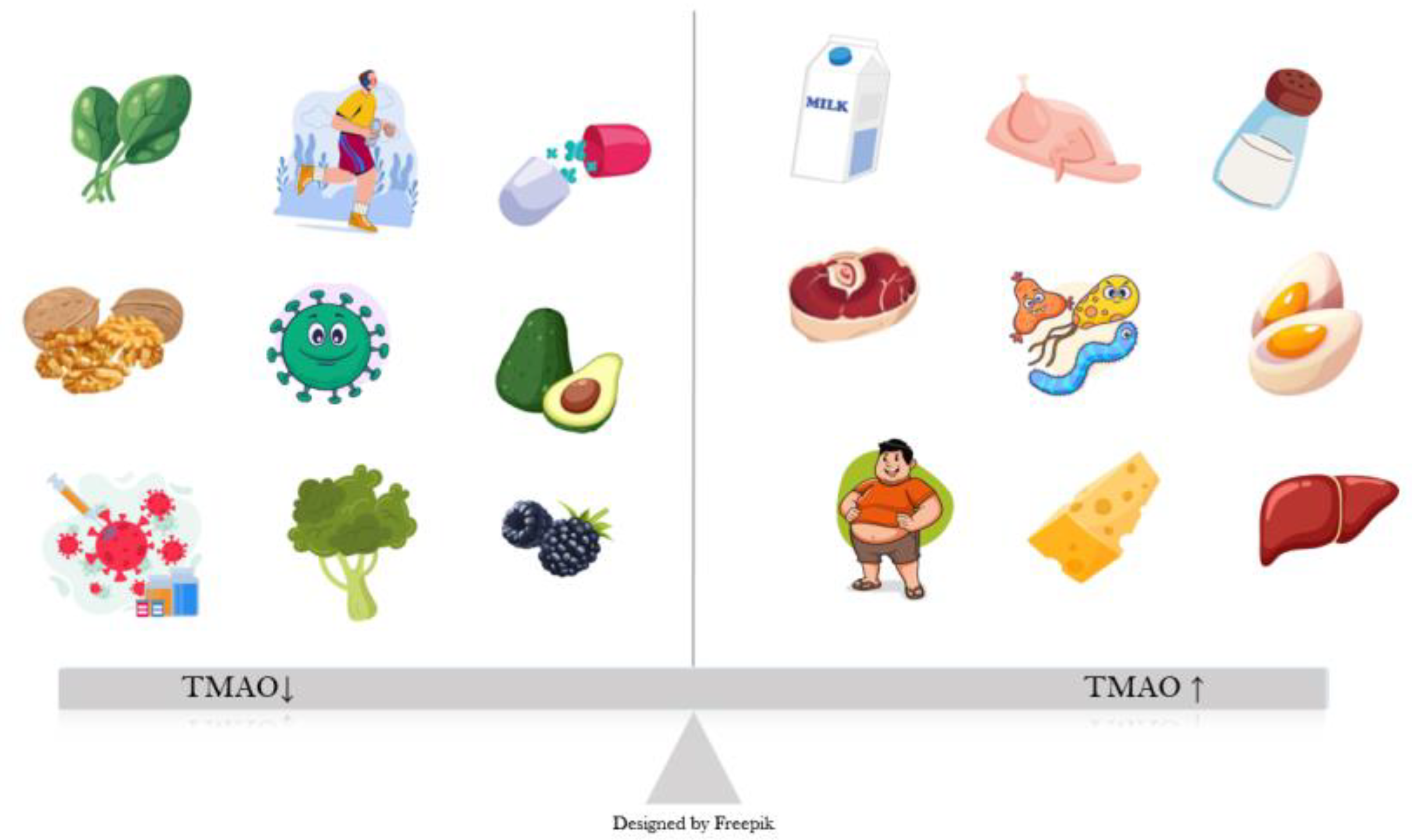

TMAO is a dietary-derived amine oxide, formed as an oxidized product of TMA. In the gut, choline, betaine, and L-carnitine are converted by the bacteria into TMA, which is absorbed into the bloodstream and directed mostly towards the liver, where it gets oxidized through hepatic flavin monooxygenases (FMO) to TMAO [

24]. Sources of dietary carnitine and choline include animal products, especially eggs, red meat, fish, and dairy (

Figure 1) [

25]. A small percentage of TMA is also converted locally, in the intestine, to ammonia, methylamine, and dimethylamine [

26]. TMAO is mostly excreted through urine, with a very small percentage from sweat, stool, and respiration [

27].

3.2. Physiological Functions of TMAO

TMAO counteracts the negative effects that elevated hydrostatic and osmotic pressure exert on the structure of different proteins. Mechanisms through which TMAO protects these proteins are insufficiently investigated, and this role seems more important in sea animals, especially those that submerge, when the pressure increases considerably [

28]. In humans, TMAO accumulates in kidney medulla, where high osmolarity is essential for urine concentration. Pathological states like diabetes, hyperglycemia increases osmotic stress, which alters intracellular osmolyte levels, this represents one of the reasons why high TMAO levels are associated with diabetes [

29].

At first glance TMAO may appear to be merely a gut-derived metabolite, suggesting that its effects are limited to the digestive system. However, similar to other metabolites—such as SCFAs —TMAO has significant implications for various organ systems, including the heart, blood vessels, kidneys, and brain [

30,

31]. Many mechanisms have been proposed, but none have been fully validated. Regarding the cardiovascular system, evidence shows that TMAO influences hypertension, atherosclerosis, metabolic disorders, and heart failure [

32,

33]. Previous studies have demonstrated that an increased risk of one of these pathologies often translates into a higher likelihood of developing another, as these conditions are not isolated but rather components of a broader spectrum [

34].

3.3. Gut Microbiota, TMAO, and Cardiovascular Disease

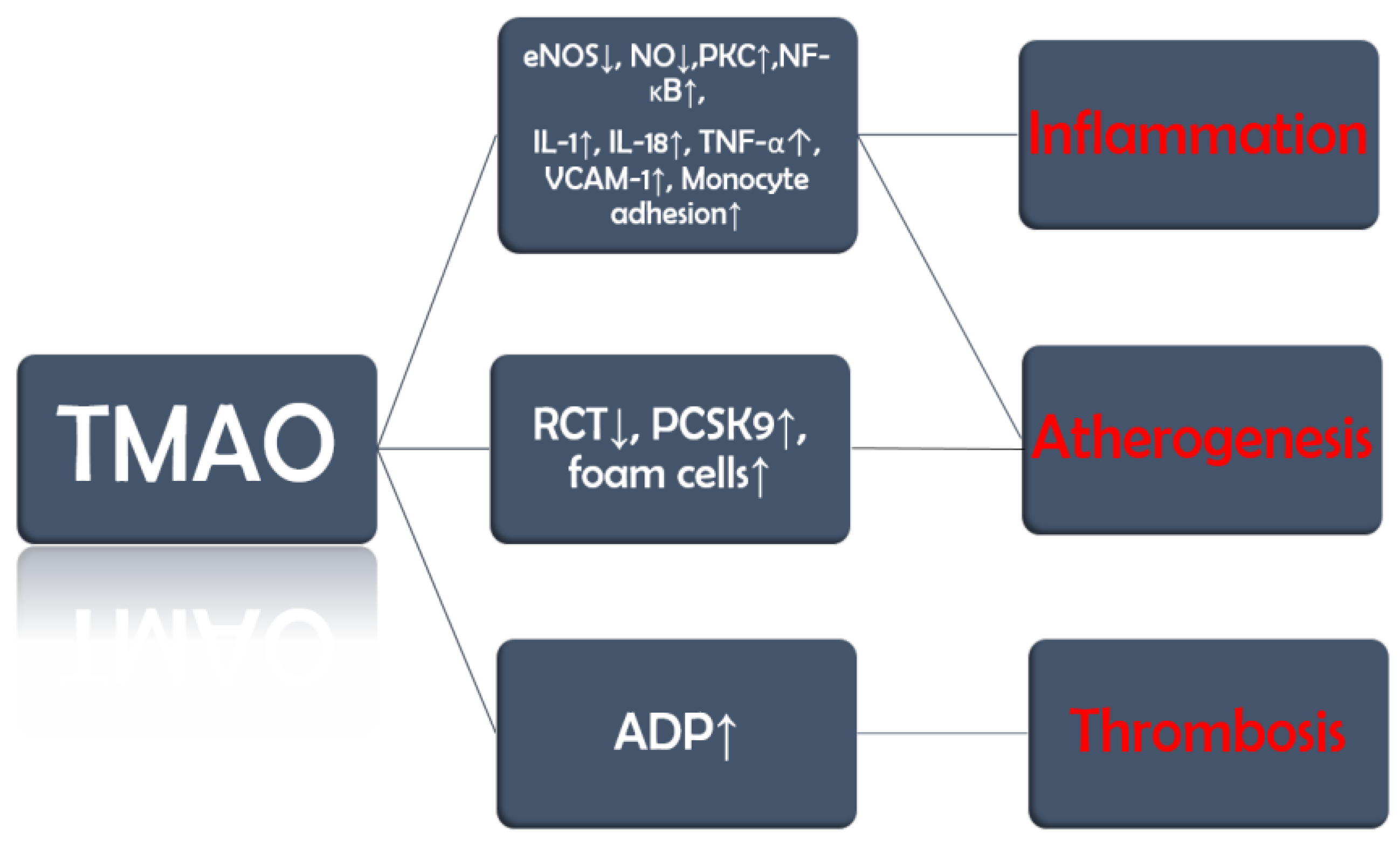

TMAO promotes endothelial dysfunction by reducing the activity of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and the production of nitric oxide (NO) (

Figure 2). Furthermore, it also activates protein kinase C (PKC), which further stimulates the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) pathway [

35]. These changes lead to the release of inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-18, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), and upregulation of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), which increases monocyte adhesion [

35,

36].

TMAO is also involved in three other processes that set the ground not only for the development but also for the progression of vascular inflammation, atherosclerosis, and its complications. Firstly, TMAO inhibits reverse cholesterol transport (RCT), by which excess cholesterol is normally removed from peripheral tissues and returned to the liver for excretion, and upregulates proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9), an enzyme that degrades low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol receptors. The consequence of these two processes is a decrease in the liver uptake of cholesterol leading to an increase in circulating LDL cholesterol [

37,

38]. Secondly, TMAO promotes the expression of scavenger receptors such as cluster of differentiation 36 (CD36) on macrophages, which increases their cholesterol uptake and leads to the development of foam cells [

39,

40] Last but not least, TMAO increases adenosine diphosphate (ADP)–induced platelet reactivity [

41]. Moreover, a study on mice published in 2023 demonstrated that TMAO interferes with clopidogrel, a P2Y12 inhibitor and antiplatelet drug used in the treatment of acute coronary syndromes. Although the obvious limitation of this study is the biological differences between mice and humans, clopidogrel resistance is a well-documented clinical issue. This finding may serve as a starting point for future studies investigating the interaction between P2Y12 inhibitors and TMAO. [

42].

Results from previous studies have depicted a complex relationship between gut microbiota, TMAO, and CVD. A study by Koeth et al. [

43] in which broad-spectrum antibiotics were used to suppress gut microbiota demonstrated that TMAO production from dietary L-carnitine was nearly eliminated in both plasma and urine, confirming the essential role of intestinal microbes in this metabolic pathway. Upon cessation of antibiotics and microbial recolonization, TMAO formation resumed, reinforcing the dependency of TMAO synthesis on gut microbiota activity. Increases in TMAO are associated with negative alterations in gut microbiota, particularly in the ratio of beneficial to harmful bacteria, as well as with a higher incidence of CVD [

44,

45,

46,

47]. At the other end of the spectrum, studies in which TMAO levels decreased—either through dietary restriction or probiotic supplementation—have shown improvements in both the gut microbiome and cardiovascular outcomes [

48,

49]. While studies have attempted to isolate the effects of TMAO, we are still far from fully understanding its role in CVD [

32]. At this point, it can only be viewed as part of a broader picture. The possibility that TMAO may serve as a bridge between gut dysbiosis and CVD suggests its potential use as an accessible biomarker for both gut microbial composition and cardiovascular risk.

4. Hypertension

4.1. Dietary Patterns and Blood Pressure

Hypertension is the primary contributor to cardiovascular disease and early mortality on a global scale [

50]. The relationship between blood pressure, individual foods, and dietary patterns—such as the Mediterranean or the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet—has been explored in many studies, with most showing similar results: diet is one of the most impactful elements in blood pressure regulation [

51,

52,

53,

54]. Initial studies established only a link between salt intake and hypertension, but more recent research suggests that polyphenols, fiber, and omega-3 fatty acids also play important roles in regulating blood pressure [

55,

56,

57]. While these factors and TMAO have each shown the potential to increase blood pressure, there also appears to be a direct connection between them—for example, individuals with high salt and low fiber intake tend to have elevated TMAO levels [

58,

59].

Khalesi et al. [

60] conducted a meta-analysis in which they included studies that investigated the effect of probiotics on blood pressure, and it came to the conclusion that, indeed, blood pressure can be reduced, especially in subjects with hypertension, with an appropriate duration and quality of the supplement. While we might be tempted to assume that the mere shift in bacterial strains within the gut is sufficient to trigger such responses, this perspective fails to capture the full picture. Alterations in the bacterial composition lead to changes in the metabolite profile, subsequently affecting downstream physiological processes. This process explains why these metabolites need to be assessed in future studies, as they offer a means to quantify the functional impact of microbial changes, not just the compositional shifts.

4.2. Animal Models: Angiotensin-II, Aging and Vascular Stiffness

Do we have evidence that TMAO increases blood pressure? Owing to their more invasive nature, animal models can offer valuable pathologic pathways and may lay the foundation for further research. Jiang et al. [

61] showed through plasma samples, imagistic and histopathologic tests that, in mice, TMAO worsens angiotensin II (AT-II)–induced hypertension by aggravating mesenteric and afferent arteriole vasoconstriction, which also led to a decrease in glomerular filtration rate (

Table 1). These changes were reversed after the administration of antibiotics. In other words, this study suggested a potential link between TMAO, high blood pressure, and AT-II. But are elevated TMAO levels alone enough to raise blood pressure? Brunt et al. [

62] showed that in both humans and mice, TMAO levels increase with age and are positively associated with rising blood pressure. It is well known that aging contributes to vascular stiffening and hypertension, so these findings cannot offer a definitive answer regarding causality [

63]. Importantly, the study extended its analysis by supplementing mice with dietary TMAO and monitoring aortic stiffness. TMAO supplementation increased aortic stiffness in young mice and exacerbated it in older ones, effects that were partially mediated by the accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and superoxide-induced oxidative stress. These findings suggest that dietary TMAO may contribute to hypertension, at least in part through its effects on vascular stiffening.

4.3. Human Studies and Genetic Evidence

A meta-analysis of eight studies, published in 2020, comprised of 11750 subjects from multiple geographical areas, confirmed an association between TMAO and hypertension but could not conclude on the underlying mechanisms involved, instead postulating several pathways involving inflammation, atherosclerosis, and the microbiome. While the authors selected high-quality studies, information regarding dietary intake was lacking. Furthermore, all included studies were conducted in populations with high cardiovascular risk, which differs from healthy individuals—limiting the ability to apply these findings on the general population, who would arguably benefit the most from preventive strategies [

64].

A Mendelian randomization study published in 2022 investigated the causal relationship between TMAO, its precursors (choline, carnitine, and betaine) and blood pressure using genetic data from 2076 European subjects. The results suggested that higher genetically predicted levels of TMAO and carnitine were associated with an increase in systolic blood pressure. However, this association did not reach statistical significance in MR-Egger analyses, indicating potential bias possibly due to horizontal pleiotropy. Additional limitations of the study include its relatively narrow geographic scope, as the data is representative only to individuals of European ancestry, which contradicts the known genetic and ethnic variability in hypertension mechanisms [

65,

66].

5. Metabolic Diseases

5.1. Diet, Gut Microbiota, and Obesity

Metabolic diseases such as obesity and diabetes are major cardiovascular risk factors [

67]. These conditions are among the most likely to be influenced by food intake, as they are typically associated with a caloric surplus. However, is the caloric excess the only mechanism through which diet promotes weight gain and insulin resistance? The differences in gut microbial composition between normal-weight and obese individuals suggest that additional mechanisms may be involved. Both obese mice and humans have shown a decrease in

Bacteroidetes and an increased presence of

Firmicutes in the gut, which have been associated with a lower energy expenditure [

68]. Bacteria exert their effects locally—by modulating caloric absorption through metabolites and influencing digestive enzyme secretion—and systemically, through neurohormonal pathways that affect fat deposition and even appetite regulation [

69]. Moreover, reductions in beneficial bacteria such as

Akkermansia muciniphila impair mucus production by goblet cells, favoring bacterial translocation and endotoxemia, both of which are linked to obesity and weight gain [

70,

71].

5.2. TMAO and Obesity: Clinical Evicence

Evidence from cross-sectional observational studies suggests a potential link between TMAO and obesity. Barrea et al. [

72] reported a positive association between circulating TMAO levels and increased body weight, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in 137 adult subjects. Similarly, Mihuta et al. [

73] observed comparable results in obese children, indicating a potential role for TMAO as an early biomarker of metabolic disturbances. However, the lack of data on gut microbiota composition, detailed nutrient intake, inflammatory markers, and TMAO precursors limits the ability to fully explore the underlying mechanisms involved.

Pescari et al. [

74] conducted a study on 60 subjects to investigate the relationship between TMAO, obesity, and cardiovascular risk. Body composition was assessed through body mass index (BMI) and bioimpedance parameters, evidence of subclinical atherosclerosis was evaluated using carotid ultrasound, and blood markers indicative of metabolic disease—such as fasting blood glucose, hemoglobin A1C, and lipid profile—were analyzed. Although limited by the small sample size and geographic restriction, TMAO was strongly correlated with increased intima-to-media thickness (IMT) in subjects with obesity, a marker of subclinical atherosclerosis. Additionally, the study found an association between TMAO levels and a family history of metabolic diseases, suggesting possible genetic mechanisms influencing its concentration. Higher TMAO levels were also observed in individuals more prone to sedentary behaviors. While the findings are promising, the study does not conclusively determine whether TMAO contributes causally to increased cardiovascular risk or simply reflects a state of low-grade chronic inflammation, which is typical in patients with obesity.

5.3. TMAO and Diabetes: A Controversial Relationship

While the association between TMAO levels and obesity appears more consistent, the evidence linking TMAO to diabetes remains inconclusive [

75]. Zhuang et al. [

76] reported a positive, dose-dependent relationship between circulating TMAO levels and the risk of developing diabetes. Several other studies have yielded similar findings, suggesting that TMAO may contribute to diabetes by disrupting insulin signaling, impairing glucose tolerance, and inducing β-cell dysfunction [

77,

78]. However, some studies have not only failed to confirm this association but have even proposed a potential protective role of TMAO in diabetes [

79,

80].

6. Atherosclerosis

6.1. Atherosclerosis, TMAO and Inflammation

Atherosclerosis is a systemic, progressive condition responsible for the majority of cardiovascular-related deaths worldwide [

81]. Genetic factors influence individual susceptibility, disease progression, and outcomes [

82]. While dyslipidemia remains a key risk factor, emerging evidence underlines the role of inflammation in its pathogenesis [

83]. The gut microbiota, together with its metabolites, may play a significant role in modulating the course of atherosclerosis through their influence on cholesterol metabolism and inflammatory pathways. [

84].

Wang et al. [

85] demonstrated that, in a mouse model of atherosclerosis, dietary supplementation with choline or TMAO significantly increased aortic plaque size without affecting plasma lipids, glucose, or hepatic fat. Elevated TMAO levels, rather than choline, correlated strongly with plaque burden in both male and female mice, with females showing higher baseline TMAO levels. These findings suggest a potential causal role for TMAO in atherosclerosis, independent of traditional lipid parameters.

In humans, TMAO levels have demonstrated a dose-dependent association with plaque burden, independent of gender [

85]. In patients newly diagnosed with coronary artery disease (CAD)—most often resulting from atherosclerosis—TMAO levels were found to correlate with the SYNTAX score, a widely used marker of plaque burden and disease severity [

86].

6.2. TMAO and Plaque Instability

While there is evidence linking TMAO to the development of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), it is equally important to explore its potential role in disease progression, particularly given that atherosclerosis is a continuous process, with its clinical manifestations closely tied to plaque stability [

87,

88]. You and Gao [

89] conducted a study involving 90 patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) and 90 healthy controls to investigate the relationship between the gut microbiome, circulating biomarkers, and plaque stability. Blood samples were collected to assess levels of TMAO, phenylacetylglutamine (PAGln), and standard lipid parameters. Coronary plaques were evaluated using coronary angiography and intravascular ultrasound, while fecal samples were analyzed to characterize gut microbiota composition. As anticipated, patients with CHD exhibited elevated levels of total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, and triglycerides, along with significantly higher concentrations of TMAO and PAGln. Notably, a positive association was observed between TMAO levels and plaque vulnerability. Furthermore, TMAO was also associated with plaque rupture in a study by Tan et al. [

90], which utilized optical coherence tomography (OCT) to characterize the culprit lesion in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The authors also suggested that TMAO could serve as a biomarker for plaque rupture in such patients; however, the urgency of invasive management represents a significant limitation to its practical application in this context.

6.3. TMAO and Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events (MACE)

Tang et al. studied the relationship between TMAO levels and the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events during 3 years of follow-up in 4007 patients who underwent elective cardiac catheterization. The study found that higher fasting plasma levels of TMAO were associated with an increased risk MACE). Participants in the highest TMAO quartile had a significantly greater event risk compared to those in the lowest quartile. A clear, graded relationship was observed between rising TMAO levels and cardiovascular risk [

48].

7. Heart Failure

7.1. Heart Failure and TMAO: A Vicious Cycle

Heart failure (HF) is a complex clinical syndrome associated with high morbidity and mortality, reduced functional capacity and quality of life, and substantial healthcare costs [

91]. It is not a disease in itself but rather the final common pathway of various cardiovascular conditions, such as ASCVD, cardiomyopathies, and other systemic disorders [

92]. While the association between TMAO and the aforementioned conditions may contribute to an increased cardiovascular risk and potentially to the development of HF, it is also important to explore the direct relationship between TMAO and HF itself. Notably, systemic congestion—a hallmark of HF—leads to increased intestinal permeability, which facilitates bacterial translocation and enhanced TMAO reabsorption, creating a vicious cycle that allows elevated TMAO levels to exert further detrimental effects [

93].

Trøseid et al. [

94] found higher circulating levels of choline, betaine, and TMAO in individuals with chronic heart failure. Although all three metabolites showed associations with clinical, haemodynamic, and neurohormonal markers of disease severity, only TMAO was independently linked to adverse outcomes during follow-up. Notably, TMAO levels were highest in patients with heart failure of ischemic origin, highlighting a potential connection with atherosclerosis. Additionally, despite elevated lipopolysaccharides (LPS) levels in heart failure patients compared to healthy individuals, no significant correlation was found between TMAO and LPS levels, implying that factors beyond endotoxemia may be responsible for TMAO accumulation in this setting.

7.2. TMAO: A Prognostic Factor in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF)

Kinugasa et al. [

95] investigated TMAO concentrations in a cohort of 146 patients hospitalized for acute decompensated HFpEF. They observed that individuals with elevated TMAO levels had a higher frequency of prior hospitalizations. Over a mean follow-up period exceeding two years, mortality was significantly greater in the high-TMAO group (46.6%) compared to the low-TMAO group (27.4%). Elevated TMAO levels were independently associated with a higher incidence of the composite primary outcomes. However, the study also identified a significant interaction between TMAO and nutritional status, as measured by the Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index (GNRI): the adverse prognostic impact of elevated TMAO was more pronounced in patients with low nutritional status than in those with preserved nutritional reserves. This complicates the interpretation of the findings, as it remains unclear whether poor outcomes were primarily driven by high TMAO levels or by malnutrition, which is itself a known negative prognostic factor [

96]. Additionally, B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels, a recognized prognostic biomarker in heart failure, did not differ significantly between the high- and low-TMAO groups, limiting the strength of conclusions regarding the predictive value of TMAO alone [

97].

7.3. TMAO, Heart Failure with Reduced and Mildly Reduced Ejection Fraction

In a study published in 2019 by Suzuki et al. [

98], TMAO was found to be associated with a higher incidence of mortality and hospitalization in HF subjects with reduced (HEFrEF) or mildly reduced ejection fraction (HEFmREF). TMAO and natriuretic peptide levels were evaluated based on the response to therapy according to the guidelines available at that time (beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, and diuretics). Although natriuretic peptides decreased after treatment, TMAO remained elevated, suggesting that there is no influence of the treatment on TMAO. This needs to be addressed in a future study, which would use a treatment regimen in accordance with the updated guidelines, including an angiotensin receptor and neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) and a sodium-glucose co-transporter inhibitor (SGLT2-i) [

98,

99].

Although numerous studies have demonstrated that elevated TMAO levels are associated with poorer prognosis, including increased mortality and hospitalization rates, it remains unclear whether this relationship is causative in nature [

93,

100,

101]. Moreover, even if future research clarifies the mechanisms through which TMAO contributes to adverse outcomes, further investigation is needed to assess whether modulating the gut microbiota through probiotic supplementation in patients with stable chronic heart failure could serve as a preventive strategy against decompensation.

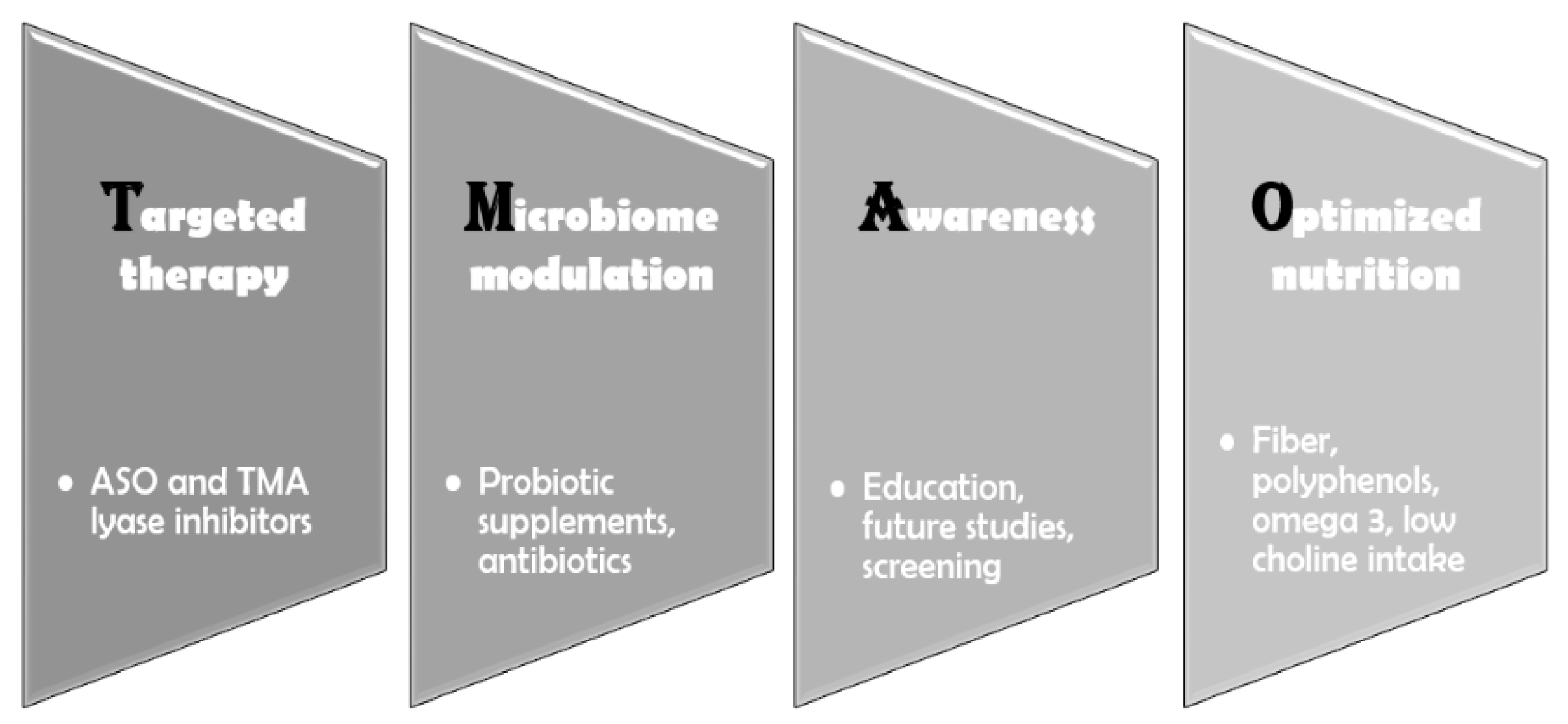

8. Interventions

8.1. Dietary Strategies and Gut Microbiota Modulation

The absence of specific drugs that directly lower TMAO levels requires a focused effort on exploring and optimizing indirect approaches to reduce its concentration and mitigate its impact (

Figure 3). There is a clear link between the gut microbiome, TMAO levels, and both metabolic and CVD. At the root of this chain lies the microbial composition of the gut, which is heavily influenced by diet [

102]. Foods high in choline and carnitine should be minimized—though not eliminated—since choline deficiency can also have adverse effects, like cognitive decline and fatty liver disease [

103]. Animal-based foods, which have long been associated with cardiovascular harm, are also high in choline; therefore, reducing their intake is essential [

102]. Furthermore, harmful gut bacterial strains must be addressed. This can be achieved by consuming foods rich in fiber and polyphenols—such as vegetables, legumes, fruits, nuts, and seeds—as well as through the use of probiotic supplements [

104,

105]. Metabolic diseases such as diabetes and obesity must be prevented and well controlled, as they are linked to alterations in the gut microbiota and elevated TMAO levels [

106]. Finally, cardiovascular conditions like heart failure must also be effectively managed due to the association between intestinal congestion, bacterial translocation, and increased TMAO levels [

99].

8.2. Berberine: Reversing TMAO and AT-II Effects

Wang et al. [

107] conducted a study on a murine model of hypertension induced by AT-II and observed a significant decrease in blood pressure after the administration of berberine, a nutritional supplement that is used in humans as well [

108]. In this study, berberine administration reversed AT-II-induced endothelial-dependent vasodilation, improved gut microbial composition, and lowered TMAO levels. Further studies are needed to clarify whether the improvement in blood pressure applies to humans, and if so, if berberine influences hypertension provoked by other mechanisms, not only by hyperexpression of AT-II. This is especially important because in the same study, choline administration only increased blood pressure in AT-II-dependent hypertension, but not in non-hypertensive rats, meaning that berberine might only influence AT-II-induced hypertension.

8.3. TMA Lyase Inhibitors: Promising Pharmacological Tools

Animal studies show promising results regarding the potential use of TMA lyase inhibitors [

109]. 3,3-Dimethyl-1-butanol (DMB), a choline analog derived from red wine, has been demonstrated in a study by Wang et al. [

110] to inhibit choline trimethylamine-lyase (CutC), a key enzyme in the production of TMA, and therefore lower plasma TMAO levels, inhibit foam cell formation, and reduce aortic plaque progression in mice, all without influencing the levels of circulating cholesterol. Roberts et al. [

111] reported similar findings for iodomethylcholine (IMC) and fluoromethylcholine (FMC), two choline analogs that more potently inhibit TMA formation in the gut compared to DMB. These compounds have minimal systemic absorption and exert their effects locally within the intestines, at the site of TMA production. Furthermore, IMC and FMC administration led to a reduction in platelet activation without affecting bleeding risk, suggesting their potential utility in addressing complications of atherosclerotic disease. TMA lyase inhibitors represent a promising strategy that merits further investigation in human studies to assess their potential cardiovascular benefits.

8.4. Gene Silencing Therapy

Subjects with genetic mutations in the

FMO3 gene present abnormally high TMA levels because the conversion rate to TMAO decreases and is clinically manifested as fish malodor syndrome [

112]. Bennet et al. [

113] showed that FMO3 is the most active enzyme from the FMO family with regard to TMA oxidation in mice and that upregulation of this enzyme led to an increase in TMAO levels. The opposite was found when they used gene silencing through antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) to reduce the activity of FMO3. Levels of hepatic FMO mARN was reduced by 90%, while a 2-fold increase in TMA and a 47% decrease in plasma TMAO were observed. These results suggest that potential interventions for the reduction in TMAO levels might exist in the form of ASO, as for other novel biomarkers in atherosclerosis, such as lipoprotein(a), but there are still plenty of questions that are not addressed [

114]. Whether the same reduction is present in humans, if the reduction translates to clinical benefits, and whether the accumulation of TMA will not lead to other side effects, remains to be investigated.

9. Conclusions

This narrative review highlights the need to shift the focus from viewing diet solely through the lens of caloric surplus and to incorporate emerging research that highlights the microbiome’s potential to modulate various pathophysiological processes. The association between TMAO and CVD has consistently provided valuable insights; however, the lack of human studies investigating the causative nature of this relationship, needs to be addressed by future trials. In mice, promising results support the role of TMAO as a potential causative factor, thus laying the groundwork for future human studies that may ultimately lead to its use as a biomarker.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.A. and C.G.; methodology, O.A. and G.G.; software, O.A. and O.L.M.; validation, O.A., C.G. and G.G.; formal analysis, C.G. and G.G.; investigation, O.A. and O.L.M.; resources, O.A. and O.L.M.; data curation, G.G.; writing—original draft preparation, O.A. and O.L.M.; writing—review and editing, O.A. and C.G.; visualization, G.G.; supervision, C.A.D., I.C. and G.G.; project administration, M.N.M. and G.G.; funding acquisition, C.A.D, I.C., M.N.M. and G.G. All authors performed equal work to the first author. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The payment of APC was supported by “Dunarea de Jos” University of Galati.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Di Cesare, M.; Perel, P.; Taylor, S.; Kabudula, C.; Bixby, H.; Gaziano, T.A.; McGhie, D.V.; Mwangi, J.; Pervan, B.; Narula, J.; et al. The Heart of the World. Glob Heart 19, 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kisling, L.A.; Das, J.M. Prevention Strategies. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Tyrovola, D.; Soulaidopoulos, S.; Tsioufis, C.; Lazaros, G. The Role of Nutrition in Cardiovascular Disease: Current Concepts and Trends. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Siopis, G.; Wong, H.Y.; Allman-Farinelli, M. Poor Quality of Dietary Assessment in Randomized Controlled Trials of Nutritional Interventions for Type 2 Diabetes May Affect Outcome Conclusions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrition 2022, 94, 111498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitolins, M.Z.; Case, T.L. What Makes Nutrition Research So Difficult to Conduct and Interpret? Diabetes Spectr 2020, 33, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Impacts of Animal-Based Diets in Cardiovascular Disease Development: A Cellular and Physiological Overview. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2308-3425/10/7/282 (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Teicholz, N. A Short History of Saturated Fat: The Making and Unmaking of a Scientific Consensus. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2023, 30, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietary Cholesterol and the Lack of Evidence in Cardiovascular Disease. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/10/6/780 (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Zhang, X.; Gérard, P. Diet-Gut Microbiota Interactions on Cardiovascular Disease. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2022, 20, 1528–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, D.; Zahra, T.; Kanaan, G.; Khan, M.U.; Mushtaq, K.; Nashwan, A.J.; Hamid, P.F. The Impact of Gut Microbiome Constitution to Reduce Cardiovascular Disease Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Current Problems in Cardiology 2023, 48, 101459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Luo, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, A.; Xia, D.; Sun, X. Causal Relationship between Gut Microbiota and Gastrointestinal Diseases: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Journal of Translational Medicine 2024, 22, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.-X.; Chen, X.-Y.; Wang, J.-Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in Health and Diseases. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel-Fiuza, M.F.; Muller, G.C.; Campos, D.M.S.; do Socorro Silva Costa, P.; Peruzzo, J.; Bonamigo, R.R.; Veit, T.; Vianna, F.S.L. Role of Gut Microbiota in Infectious and Inflammatory Diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yuan, W.; Yang, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Xu, D.; Sun, X.; Sun, W. Emerging Role of Gut Microbiota in Autoimmune Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.A.; Luong, M.K.; Shaw, H.; Nathan, P.; Bataille, V.; Spector, T.D. The Gut Microbiome: What the Oncologist Ought to Know. Br J Cancer 2021, 125, 1197–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesci, A.; Carnuccio, C.; Ruggieri, V.; D’Alessandro, A.; Di Giorgio, A.; Santoro, L.; Gasbarrini, A.; Santoliquido, A.; Ponziani, F.R. Gut Microbiota and Cardiovascular Disease: Evidence on the Metabolic and Inflammatory Background of a Complex Relationship. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 9087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Rubio-Zarapuz, A.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Microbiota Implications in Endocrine-Related Diseases: From Development to Novel Therapeutic Approaches. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, H.; Arbab, S.; Tian, Y.; Liu, C.; Chen, Y.; Qijie, L.; Khan, M.I.U.; Hassan, I.U.; Li, K. The Gut Microbiota–Brain Axis in Neurological Disorder. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, K. Emerging Role of the Host Microbiome in Neuropsychiatric Disorders: Overview and Future Directions. Mol Psychiatry 2023, 28, 3625–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tan, Y.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, D.; Feng, W.; Peng, C. Functions of Gut Microbiota Metabolites, Current Status and Future Perspectives. Aging Dis 2022, 13, 1106–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliphant, K.; Allen-Vercoe, E. Macronutrient Metabolism by the Human Gut Microbiome: Major Fermentation by-Products and Their Impact on Host Health. Microbiome 2019, 7, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hul, M.V.; Cani, P.D.; Petitfils, C.; Vos, W.M.D.; Tilg, H.; El-Omar, E.M. What Defines a Healthy Gut Microbiome? Gut 2024, 73, 1893–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wei, C.; Min, L.; Zhu, L.-Y. Good or Bad: Gut Bacteria in Human Health and Diseases. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment 2018, 32, 1075–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Peng, X.; Liu, J.; Tang, S.; Yang, X.; Wang, J. The Association of Plasma TMAO and Body Composition with the Occurrence of PEW in Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients. Ren Fail 47, 2481202. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, M.; Dai, L.; Avesani, C.M.; Kublickiene, K.; Stenvinkel, P. The Dietary Source of Trimethylamine N-Oxide and Clinical Outcomes: An Unexpected Liaison. Clin Kidney J 2023, 16, 1804–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatarek, P.; Kaluzna-Czaplinska, J. Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) in Human Health. EXCLI J 2021, 20, 301–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velasquez, M.T.; Ramezani, A.; Manal, A.; Raj, D.S. Trimethylamine N-Oxide: The Good, the Bad and the Unknown. Toxins (Basel) 2016, 8, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papandreou, C.; Moré, M.; Bellamine, A. Trimethylamine N-Oxide in Relation to Cardiometabolic Health—Cause or Effect? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworska, K.; Kuś, M.; Ufnal, M. TMAO and Diabetes: From the Gut Feeling to the Heart of the Problem. Nutr. Diabetes 2025, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; O’Connor, A.L.; Becker, S.L.; Patel, R.K.; Martindale, R.G.; Tsikitis, V.L. Gut Microbial Metabolites and Its Impact on Human Health. Ann Gastroenterol 2023, 36, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, H.K.; Pereira, M.; Bosco, J.; George, J.; Jayaraman, V.; Krishna, K.; Wang, T.; Bei, K.; Rajasekaran, J.J. Gut Commensals and Their Metabolites in Health and Disease. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canyelles, M.; Borràs, C.; Rotllan, N.; Tondo, M.; Escolà-Gil, J.C.; Blanco-Vaca, F. Gut Microbiota-Derived TMAO: A Causal Factor Promoting Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease? Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncal, C.; Martínez-Aguilar, E.; Orbe, J.; Ravassa, S.; Fernandez-Montero, A.; Saenz-Pipaon, G.; Ugarte, A.; Estella-Hermoso de Mendoza, A.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Fernández-Alonso, S.; et al. Trimethylamine-N-Oxide (TMAO) Predicts Cardiovascular Mortality in Peripheral Artery Disease. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 15580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olvera Lopez, E.; Ballard, B.D.; Jan, A. Cardiovascular Disease. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Dai, M. Trimethylamine N-Oxide Generated by the Gut Microbiota Is Associated with Vascular Inflammation: New Insights into Atherosclerosis. Mediators Inflamm 2020, 2020, 4634172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantino-Jonapa, L.A.; Espinoza-Palacios, Y.; Escalona-Montaño, A.R.; Hernández-Ruiz, P.; Amezcua-Guerra, L.M.; Amedei, A.; Aguirre-García, M.M. Contribution of Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) to Chronic Inflammatory and Degenerative Diseases. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, C.; Yu, J.; Meng, Z.; Lu, D.; Ding, H.; Sun, H.; Shi, G.; Xue, D.; Meng, X. PCSK9 and APOA4: The Dynamic Duo in TMAO-Induced Cholesterol Metabolism and Cholelithiasis. Journal of Clinical and Translational Hepatology 2025, 13, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- (PDF) Trimethylamine N-Oxide and the Reverse Cholesterol Transport in Cardiovascular Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study. ResearchGate. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Qiu, J.; Lian, J.; Yang, X.; Zhou, J. Gut Metabolite Trimethylamine-N-Oxide in Atherosclerosis: From Mechanism to Therapy. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Yang, C.; Wang, B.; Zhang, X.; Hu, T.; Gu, Y.; Li, J. Trimethylamine N-Oxide Promotes Atherosclerosis via CD36-Dependent MAPK/JNK Pathway. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2018, 97, 941–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.; Kleber, M.E.; Delgado, G.E.; März, W.; Andreas, M.; Hellstern, P.; Marx, N.; Schuett, K.A. Trimethylamine N-Oxide and Adenosine Diphosphate–Induced Platelet Reactivity Are Independent Risk Factors for Cardiovascular and All-Cause Mortality. Circulation Research 2020, 126, 660–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, P.-X.; Tai, T.; Jiang, L.-P.; Ji, J.-Z.; Mi, Q.-Y.; Zhu, T.; Li, Y.-F.; Xie, H.-G. Choline and Trimethylamine N-Oxide Impair Metabolic Activation of and Platelet Response to Clopidogrel through Activation of the NOX/ROS/Nrf2/CES1 Pathway. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2023, 21, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeth, R.A.; Wang, Z.; Levison, B.S.; Buffa, J.A.; Org, E.; Sheehy, B.T.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, L.; et al. Intestinal Microbiota Metabolism of L-Carnitine, a Nutrient in Red Meat, Promotes Atherosclerosis. Nat Med 2013, 19, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatarek, P.; Kaluzna-Czaplinska, J. Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) in Human Health. EXCLI J 2021, 20, 301–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.H.W.; Kitai, T.; Hazen, S.L. Gut Microbiota in Cardiovascular Health and Disease. Circulation Research 2017, 120, 1183–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.H.W.; Hazen, S.L. The Contributory Role of Gut Microbiota in Cardiovascular Disease. J Clin Invest 2014, 124, 4204–4211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Yin, Y.; Deng, J.; Yang, X.; Bai, S.; Yu, R. Unveiling the Causal Effects of Gut Microbiome on Trimethylamine N-Oxide: Evidence from Mendelian Randomization. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.H.W.; Wang, Z.; Levison, B.S.; Koeth, R.A.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Wu, Y.; Hazen, S.L. Intestinal Microbial Metabolism of Phosphatidylcholine and Cardiovascular Risk. New England Journal of Medicine 2013, 368, 1575–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Klipfell, E.; Bennett, B.J.; Koeth, R.; Levison, B.S.; DuGar, B.; Feldstein, A.E.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Chung, Y.-M.; et al. Gut Flora Metabolism of Phosphatidylcholine Promotes Cardiovascular Disease. Nature 2011, 472, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, K.T.; Stefanescu, A.; He, J. The Global Epidemiology of Hypertension. Nat Rev Nephrol 2020, 16, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, M.A.; Gea, A.; Ruiz-Canela, M. The Mediterranean Diet and Cardiovascular Health. Circulation Research 2019, 124, 779–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, A.H.; Appel, L.J.; Vadiveloo, M.; Hu, F.B.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Rebholz, C.M.; Sacks, F.M.; Thorndike, A.N.; Van Horn, L.; Wylie-Rosett, J.; et al. 2021 Dietary Guidance to Improve Cardiovascular Health: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 144, e472–e487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaibinobarian, N.; Danehchin, L.; Mozafarinia, M.; Hekmatdoost, A.; Eghtesad, S.; Masoudi, S.; Mohammadi, Z.; Mard, A.; Paridar, Y.; Abolnezhadian, F.; et al. The Association between DASH Diet Adherence and Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Int J Prev Med 2023, 14, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effects of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Diet on Change in Cardiac Biomarkers Over Time: Results From the DASH-Sodium Trial | Journal of the American Heart Association. Available online: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/JAHA.122.026684 (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Grosso, G.; Godos, J.; Currenti, W.; Micek, A.; Falzone, L.; Libra, M.; Giampieri, F.; Forbes-Hernández, T.Y.; Quiles, J.L.; Battino, M.; et al. The Effect of Dietary Polyphenols on Vascular Health and Hypertension: Current Evidence and Mechanisms of Action. Nutrients 2022, 14, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Relationship Between Dietary Fiber Intake and Blood Pressure Worldwide: A Systematic Review | Cureus. Available online: https://www.cureus.com/articles/188965-the-relationship-between-dietary-fiber-intake-and-blood-pressure-worldwide-a-systematic-review#!/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Zhang, X.; Ritonja, J.A.; Zhou, N.; Chen, B.E.; Li, X. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Intake and Blood Pressure: A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Am Heart Assoc 2022, 11, e025071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, T.; Shao, Y.; Chen, X.; Han, L.; Zhou, R.; Wu, B. Inhibition of Microbiota-Dependent Trimethylamine N-Oxide Production Ameliorates High Salt Diet-Induced Sympathetic Excitation and Hypertension in Rats by Attenuating Central Neuroinflammation and Oxidative Stress. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 856914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, M.; Brandl, B.; Neuhaus, K.; Wudy, S.; Kleigrewe, K.; Hauner, H.; Skurk, T. Dietary Fiber Intervention Modulates the Formation of the Cardiovascular Risk Factor Trimethylamine-N-Oxide after Beef Consumption: MEATMARK – a Randomized Pilot Intervention Study 2024, 2024. 07.08.60 2621.

- Khalesi, S.; Sun, J.; Buys, N.; Jayasinghe, R. Effect of Probiotics on Blood Pressure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized, Controlled Trials. Hypertension 2014, 64, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Shui, Y.; Cui, Y.; Tang, C.; Wang, X.; Qiu, X.; Hu, W.; Fei, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; et al. Gut Microbiota Dependent Trimethylamine N-Oxide Aggravates Angiotensin II–Induced Hypertension. Redox Biol 2021, 46, 102115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunt, V.E.; Casso, A.G.; Gioscia-Ryan, R.A.; Sapinsley, Z.J.; Ziemba, B.P.; Clayton, Z.S.; Bazzoni, A.E.; VanDongen, N.S.; Richey, J.J.; Hutton, D.A.; et al. Gut Microbiome-Derived Metabolite Trimethylamine N-Oxide Induces Aortic Stiffening and Increases Systolic Blood Pressure With Aging in Mice and Humans. Hypertension 2021, 78, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, G.F. Arterial Stiffness in Aging: Does It Have a Place in Clinical Practice? Hypertension 2021, 77, 768–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Zheng, L.; Zhuang, R.; Yu, P.; Xu, Z.; Liu, G.; Xi, X.; Zhou, X.; Fan, H. The Gut Microbial Metabolite Trimethylamine N-Oxide and Hypertension Risk: A Systematic Review and Dose–Response Meta-Analysis. Adv Nutr 2020, 11, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Luo, Q.; Ding, X.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Z. Trimethylamine N-Oxide and Its Precursors in Relation to Blood Pressure: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9, 922441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keaton, J.M.; Hellwege, J.N.; Giri, A.; Torstenson, E.S.; Kovesdy, C.P.; Sun, Y.V.; Wilson, P.W.F.; O’Donnell, C.J.; Edwards, T.L.; Hung, A.M.; et al. Associations of Biogeographic Ancestry with Hypertension Traits. J Hypertens 2021, 39, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, D.; Barman, S.; Ranjan, R.; Stone, H. A Systematic Review of Major Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Growing Global Health Concern. Cureus 14, e30119. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoun, A.; Darwish, F.; Hamod, N. The Influence of the Gut Microbiome on Obesity in Adults and the Role of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics for Weight Loss. Prev Nutr Food Sci 2020, 25, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, A.C.; Hoffmann, C.; Mota, J.F. The Human Gut Microbiota: Metabolism and Perspective in Obesity. Gut Microbes 2018, 9, 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, V.F.; Elias-Oliveira, J.; Pereira, Í.S.; Pereira, J.A.; Barbosa, S.C.; Machado, M.S.G.; Carlos, D. Akkermansia Muciniphila and Gut Immune System: A Good Friendship That Attenuates Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Obesity, and Diabetes. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 934695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobe, M.; Agbla, S.C.; Todorcevic, M.; Darboe, B.; Danso, E.; de Barros, J.-P.P.; Lagrost, L.; Karpe, F.; Prentice, A.M. Possible Mediators of Metabolic Endotoxemia in Women with Obesity and Women with Obesity-Diabetes in The Gambia. Int J Obes 2022, 46, 1892–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrea, L.; Annunziata, G.; Muscogiuri, G.; Di Somma, C.; Laudisio, D.; Maisto, M.; de Alteriis, G.; Tenore, G.C.; Colao, A.; Savastano, S. Trimethylamine-N-Oxide (TMAO) as Novel Potential Biomarker of Early Predictors of Metabolic Syndrome. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihuta, M.S.; Paul, C.; Borlea, A.; Roi, C.M.; Pescari, D.; Velea-Barta, O.-A.; Mozos, I.; Stoian, D. Connections between Serum Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO), a Gut-Derived Metabolite, and Vascular Biomarkers Evaluating Arterial Stiffness and Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Children with Obesity. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14, 1253584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescari, D.; Mihuta, M.S.; Bena, A.; Stoian, D. Independent Predictors of Circulating Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) and Resistin Levels in Subjects with Obesity: Associations with Carotid Intima-Media Thickness and Metabolic Parameters. Nutrients 2025, 17, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworska, K.; Kuś, M.; Ufnal, M. TMAO and Diabetes: From the Gut Feeling to the Heart of the Problem. Nutr. Diabetes 2025, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, R.; Ge, X.; Han, L.; Yu, P.; Gong, X.; Meng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, H.; Zheng, L.; Liu, Z.; et al. Gut Microbe-Generated Metabolite Trimethylamine N-Oxide and the Risk of Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Obes Rev 2019, 20, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, S.; Lu, X.; Fang, A.; Chen, Y.; Huang, R.; Lin, X.; Huang, Z.; Ma, J.; Huang, B.; et al. Serum Trimethylamine-N-Oxide Is Associated with Incident Type 2 Diabetes in Middle-Aged and Older Adults: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Transl Med 2022, 20, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, H.; Peng, R.; Ruan, W.; Zhang, Q.; Cai, E.; Ma, M.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Dynamic Changes in Gut Microbiota-Derived Metabolite Trimethylamine-N-Oxide and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Potential for Dietary Changes in Diabetes Prevention. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaitre, R.N.; Jensen, P.N.; Wang, Z.; Fretts, A.M.; McKnight, B.; Nemet, I.; Biggs, M.L.; Sotoodehnia, N.; de Oliveira Otto, M.C.; Psaty, B.M.; et al. Association of Trimethylamine N-Oxide and Related Metabolites in Plasma and Incident Type 2 Diabetes: The Cardiovascular Health Study. JAMA Network Open 2021, 4, e2122844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papandreou, C.; Bulló, M.; Zheng, Y.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Yu, E.; Guasch-Ferré, M.; Toledo, E.; Clish, C.; Corella, D.; Estruch, R.; et al. Plasma Trimethylamine-N-Oxide and Related Metabolites Are Associated with Type 2 Diabetes Risk in the Prevención Con Dieta Mediterránea (PREDIMED) Trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2018, 108, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedkoff, L.; Briffa, T.; Zemedikun, D.; Herrington, S.; Wright, F.L. Global Trends in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Clinical Therapeutics 2023, 45, 1087–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurst, C.; Maixner, F.; Paladin, A.; Mussauer, A.; Valverde, G.; Narula, J.; Thompson, R.; Zink, A. Genetic Predisposition of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in Ancient Human Remains. Annals of Global Health 2024, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, P.; Cui, Z.-Y.; Huang, X.-F.; Zhang, D.-D.; Guo, R.-J.; Han, M. Inflammation and Atherosclerosis: Signaling Pathways and Therapeutic Intervention. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Li, L.; Sun, Z.; Zang, G.; Zhang, L.; Shao, C.; Wang, Z. Gut Microbiota and Atherosclerosis—Focusing on the Plaque Stability. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021, 8, 668532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Klipfell, E.; Bennett, B.J.; Koeth, R.; Levison, B.S.; Dugar, B.; Feldstein, A.E.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Chung, Y.-M.; et al. Gut Flora Metabolism of Phosphatidylcholine Promotes Cardiovascular Disease. Nature 2011, 472, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, M.; Li, H.; Li, J. Circulating Trimethylamine N-Oxide Is Correlated with High Coronary Artery Atherosclerotic Burden in Individuals with Newly Diagnosed Coronary Heart Disease. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 2024, 24, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, K.; Kawakami, R.; Finn, A.V.; Virmani, R. Differences in Stable and Unstable Atherosclerotic Plaque. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 2024, 44, 1474–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atherosclerotic Plaque Stabilization and Regression: A Review of Clinical Evidence | Nature Reviews Cardiology. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41569-023-00979-8 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- You, X.; Gao, B. Association between Intestinal Flora Metabolites and Coronary Artery Vulnerable Plaque Characteristics in Coronary Heart Disease. Br J Hosp Med 2025, 86, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.; Sheng, Z.; Zhou, P.; Liu, C.; Zhao, H.; Song, L.; Li, J.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; et al. Plasma Trimethylamine N-Oxide as a Novel Biomarker for Plaque Rupture in Patients With ST-Segment–Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions 2019, 12, e007281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savarese, G.; Becher, P.M.; Lund, L.H.; Seferovic, P.; Rosano, G.M.C.; Coats, A.J.S. Global Burden of Heart Failure: A Comprehensive and Updated Review of Epidemiology. Cardiovascular Research 2022, 118, 3272–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines | JACC. Available online: https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.12.012 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ke, B.; Du, J. TMAO: How Gut Microbiota Contributes to Heart Failure. Translational Research 2021, 228, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trøseid, M.; Ueland, T.; Hov, J.R.; Svardal, A.; Gregersen, I.; Dahl, C.P.; Aakhus, S.; Gude, E.; Bjørndal, B.; Halvorsen, B.; et al. Microbiota-Dependent Metabolite Trimethylamine-N-Oxide Is Associated with Disease Severity and Survival of Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. Journal of Internal Medicine 2015, 277, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinugasa, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Kamitani, H.; Hirai, M.; Yanagihara, K.; Kato, M.; Yamamoto, K. Trimethylamine N-oxide and Outcomes in Patients Hospitalized with Acute Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction. ESC Heart Fail 2021, 8, 2103–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diagnosis and Management of Malnutrition in Patients with Heart Failure. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/12/9/3320 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Prognostic Value of NT-proBNP in the New Era of Heart Failure Treatment - PMC. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11398679/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Suzuki, T.; Yazaki, Y.; Voors, A.A.; Jones, D.J.L.; Chan, D.C.S.; Anker, S.D.; Cleland, J.G.; Dickstein, K.; Filippatos, G.; Hillege, H.L.; et al. Association with Outcomes and Response to Treatment of Trimethylamine N-Oxide in Heart Failure: Results from BIOSTAT-CHF. European Journal of Heart Failure 2019, 21, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2021 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure. Available online: https://www.escardio.org/Guidelines/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Acute-and-Chronic-Heart-Failure (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Li, X.; Fan, Z.; Cui, J.; Li, D.; Lu, J.; Cui, X.; Xie, L.; Wu, Y.; Lin, Q.; Li, Y. Trimethylamine N-Oxide in Heart Failure: A Meta-Analysis of Prognostic Value. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9, 817396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisci, G.; Israr, M.Z.; Cittadini, A.; Bossone, E.; Suzuki, T.; Salzano, A. Heart Failure and Trimethylamine N-oxide: Time to Transform a ‘Gut Feeling’ in a Fact? ESC Heart Fail 2022, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P. Influence of Foods and Nutrition on the Gut Microbiome and Implications for Intestinal Health. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 9588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeisel, S.H.; da Costa, K.-A. Choline: An Essential Nutrient for Public Health. Nutr Rev 2009, 67, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrasekaran, P.; Weiskirchen, S.; Weiskirchen, R. Effects of Probiotics on Gut Microbiota: An Overview. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 6022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.K.; Chang, H.-W.; Yan, D.; Lee, K.M.; Ucmak, D.; Wong, K.; Abrouk, M.; Farahnik, B.; Nakamura, M.; Zhu, T.H.; et al. Influence of Diet on the Gut Microbiome and Implications for Human Health. Journal of Translational Medicine 2017, 15, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafavi Abdolmaleky, H.; Zhou, J.-R. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis, Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Epigenetic Alterations in Metabolic Diseases. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, F.; Zhou, Q.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tu, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Shao, Y.; Xu, S.; Wang, Y.; et al. Berberine Improves Vascular Dysfunction by Inhibiting Trimethylamine-N-Oxide via Regulating the Gut Microbiota in Angiotensin II-Induced Hypertensive Mice. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 814855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Och, A.; Och, M.; Nowak, R.; Podgórska, D.; Podgórski, R. Berberine, a Herbal Metabolite in the Metabolic Syndrome: The Risk Factors, Course, and Consequences of the Disease. Molecules 2022, 27, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L.; Zhang, H.; Xiang, Q.; Shen, L.; Guo, X.; Zhai, C.; Hu, H. Targeting Trimethylamine N-Oxide: A New Therapeutic Strategy for Alleviating Atherosclerosis. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9, 864600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Roberts, A.B.; Buffa, J.A.; Levison, B.S.; Zhu, W.; Org, E.; Gu, X.; Huang, Y.; Zamanian-Daryoush, M.; Culley, M.K.; et al. Non-Lethal Inhibition of Gut Microbial Trimethylamine Production for the Treatment of Atherosclerosis. Cell 2015, 163, 1585–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.B.; Gu, X.; Buffa, J.A.; Hurd, A.G.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, W.; Gupta, N.; Skye, S.M.; Cody, D.B.; Levison, B.S.; et al. Development of a Gut Microbe-Targeted Non-Lethal Therapeutic to Inhibit Thrombosis Potential. Nat Med 2018, 24, 1407–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.C.; Leroux, J.-C. Treatments of Trimethylaminuria: Where We Are and Where We Might Be Heading. Drug Discovery Today 2020, 25, 1710–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, B.J.; de Aguiar Vallim, T.Q.; Wang, Z.; Shih, D.M.; Meng, Y.; Gregory, J.; Allayee, H.; Lee, R.; Graham, M.; Crooke, R.; et al. Trimethylamine-N-Oxide, a Metabolite Associated with Atherosclerosis, Exhibits Complex Genetic and Dietary Regulation. Cell Metab 2013, 17, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tselepis, A.D. Treatment of Lp(a): Is It the Future or Are We Ready Today? Curr Atheroscler Rep 2023, 25, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).