Submitted:

14 June 2025

Posted:

16 June 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Events and Time

2.1. Schrödinger’s Question

- ’events’ Unlike non-living matter, living matter is dynamic, changing autonomously by its internal laws; we must think differently about it, including making hypotheses and testing them in the labs (including computing methods). Processes (and not only jumps) happen inside it, and we can observe some characteristic points.

- ’space and time’ Those characteristic points are significant changes resulting from processes that have material carriers, which change their positions with finite speed, so (unlike in classical science) the events also have the characteristics ’time’ in addition to their ’position’. In biology, the spatiotemporal behavior is implemented by slow ion currents. In other words, instead of ’moments’, sometimes we must consider ’periods’, and in the interest of mathematical description, we imitate the slow processes by closely matching ’instant’ processes.

- ’living organism’ To describe its dynamic behavior, we must introduce a dynamic description.

- ’within the spatial boundary’ Laws of physics are usually derived for stand-alone systems, in the sense that the considered system is infinitely far from the rest of the world; also, in the sense that the changes we observe do not significantly change the external world, so its idealized disturbing effect will not change it. In biology, we must consider changing resources.

- ’accounted for by physics’[by extraordinary laws] We are accustomed to abstracting and testing a static attribute, and we derive the ’ordinary’ laws of motion for the ’net’ interactions. In the case of physiology, nature prevents us from testing ’net’ interactions. We must understand that some interactions are non-separable, and we must derive ’non-ordinary’ laws [1,2]. The forces are not unknown, but the known ’ordinary’ laws of motion of physics are about single-speed interactions.

- ’yet tested in the physical laboratory’[including physiological ones] We need to test those ’constructions’ in laboratories, in their actual environment, and in ’working state’. As we did with non-living matter, we need to develop and gradually refine the testing methods and the hypotheses. Moreover, we must not forget that our methods refer to ’states’, and this time, we test ’processes’. Not only in measuring them but also in handling them computationally, we need slightly different algorithms.

2.2. Notion and Time of Event

2.3. Time

2.3.1. Time in Technical Computing

2.3.2. Time Scales

2.3.3. Aligning the Time Scales

2.3.4. Time Resolution

2.3.5. Time Stamping

2.3.6. Simulating Time

3. Spiking and Information

3.1. Information Coding

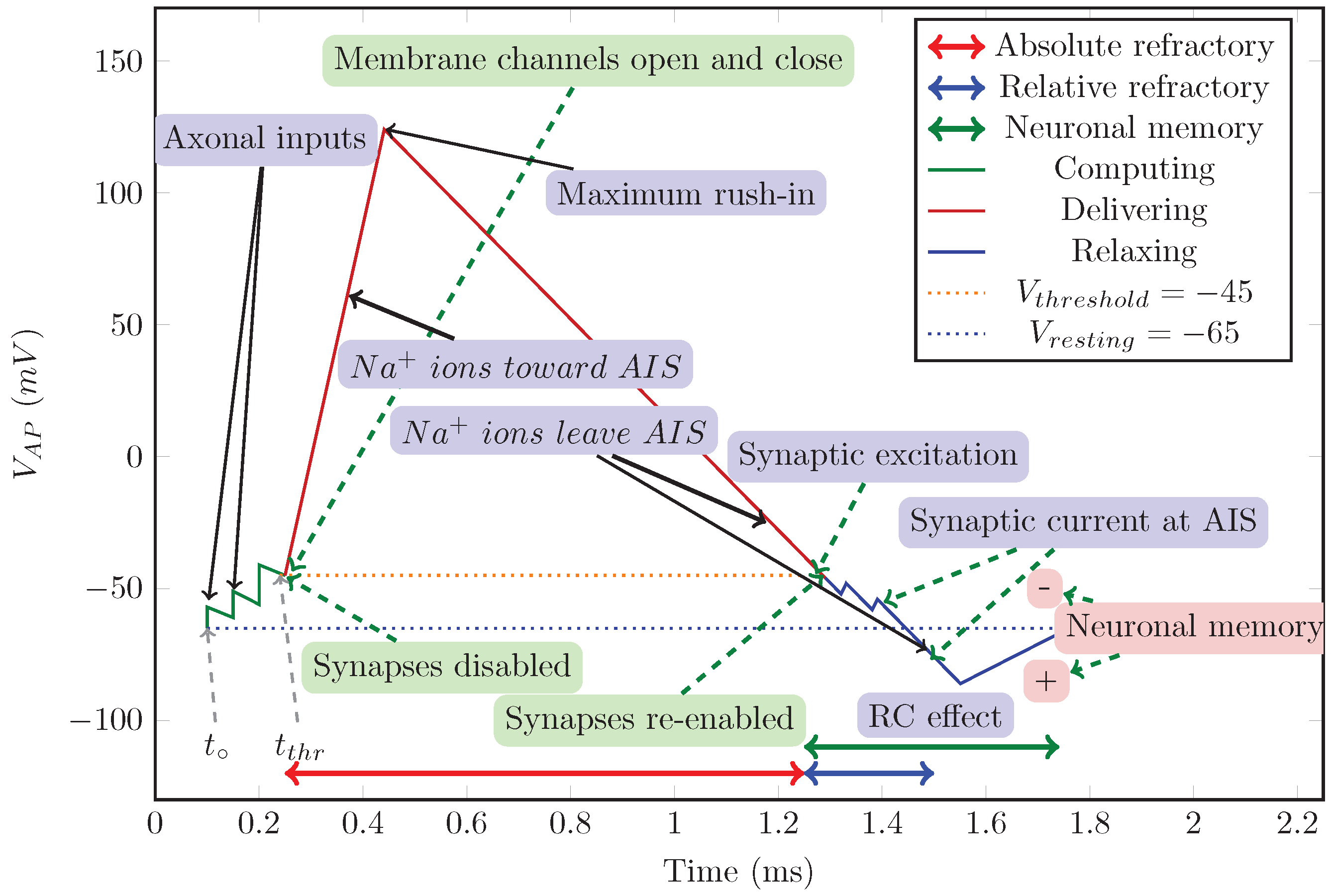

3.2. Spiking

3.3. Neuronal Learning

3.4. Information Density

4. Technical Aspects

4.1. Neural Connectivity

| Algorithm 1 The basic clock-driven algorithm [57], Figure 1 |

|

| Algorithm 2 The basic event-driven algorithm with instantaneous synaptic interactions [57], Figure 2 |

|

4.1.1. Queue Handling

- the two latter algorithms comprise a deadlock, as all neurons expect the others to compute inputs (or work with values calculated in previous cycles, mixing "this" and "previous" values)

- after processing a spike initiation, the membrane potential is reset, excluding the important role of local neuronal memory (also learning)

- the algorithms are optimized to single-thread processing by applying a single event queue

| Algorithm 3 The basic event-driven algorithm with non-instantaneous synaptic interactions [57], Figure 3 |

|

4.1.2. Limiting Computing Time

4.1.3. Sharing Processing Units

4.1.4. Pruning Connections

4.2. Hardware/Software Limitations

5. Biological Computing

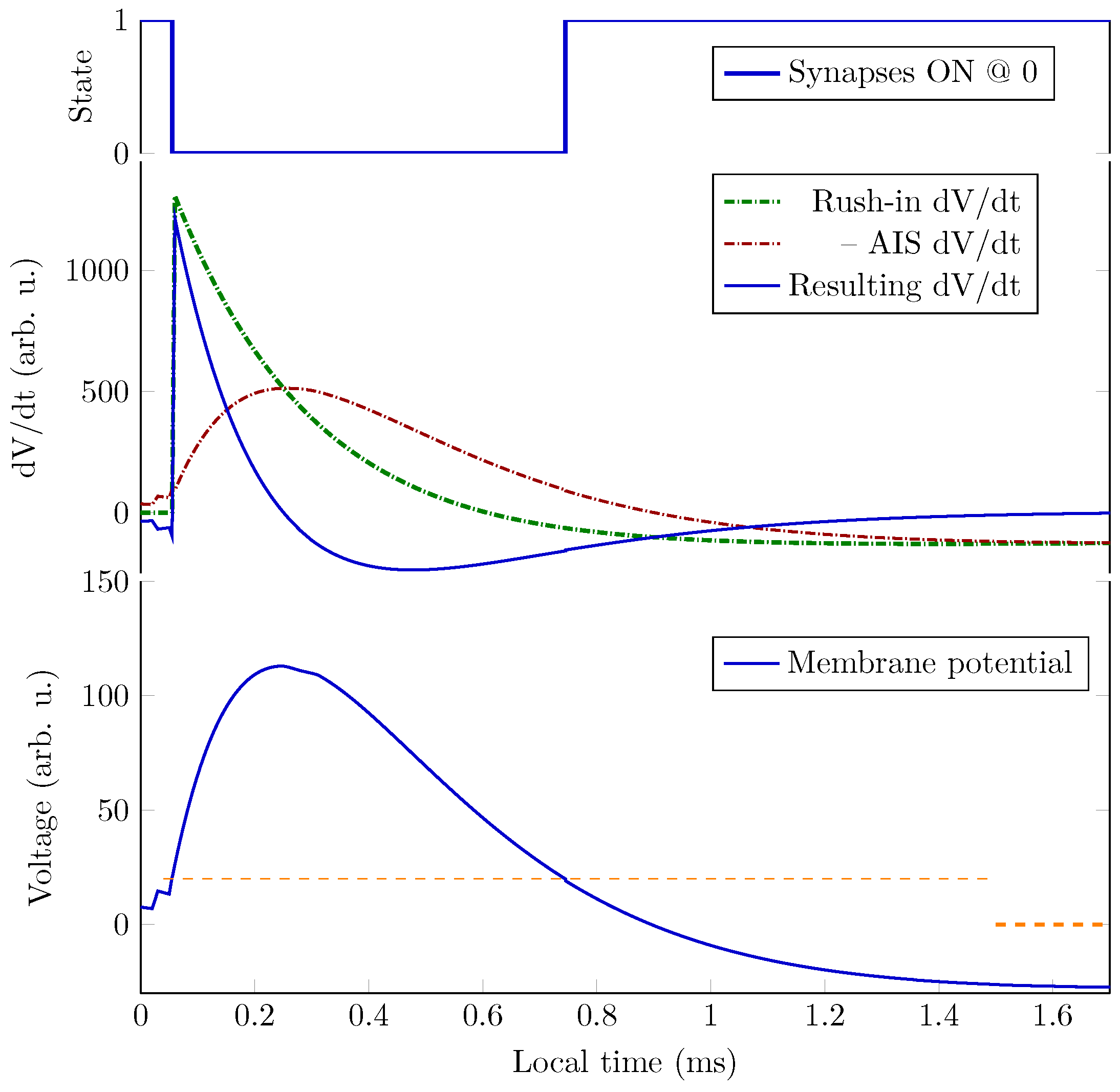

5.1. Conceptual operation

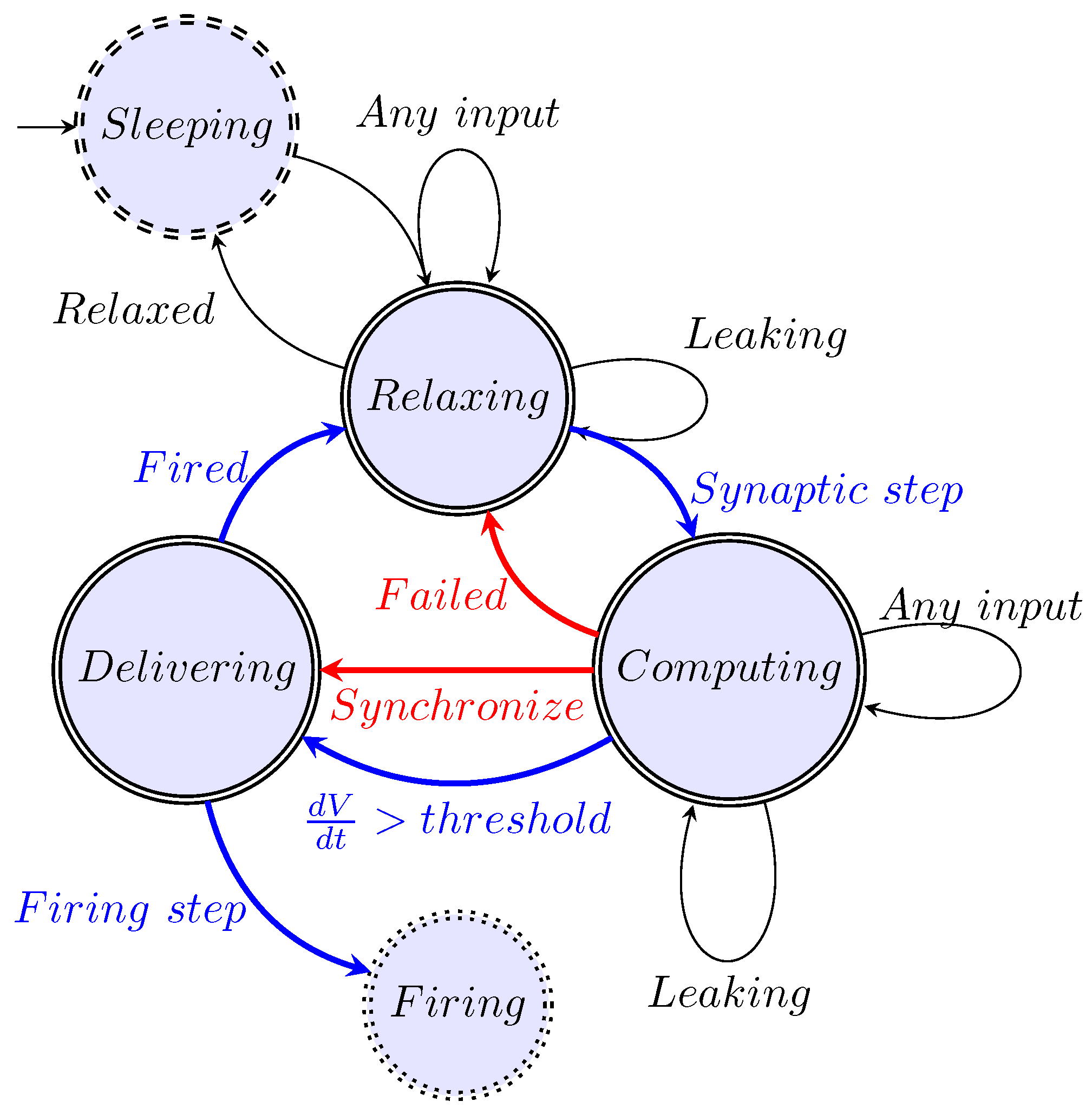

5.2. Stage Machine

5.2.1. Stage ’Relaxing’

5.2.2. Stage ’Computing’

5.2.3. Stage ’Delivering’

5.2.4. Extra Stages

5.2.5. Synaptic Control

5.2.6. Timed Cooperation of Neurons

5.3. Classic Stages

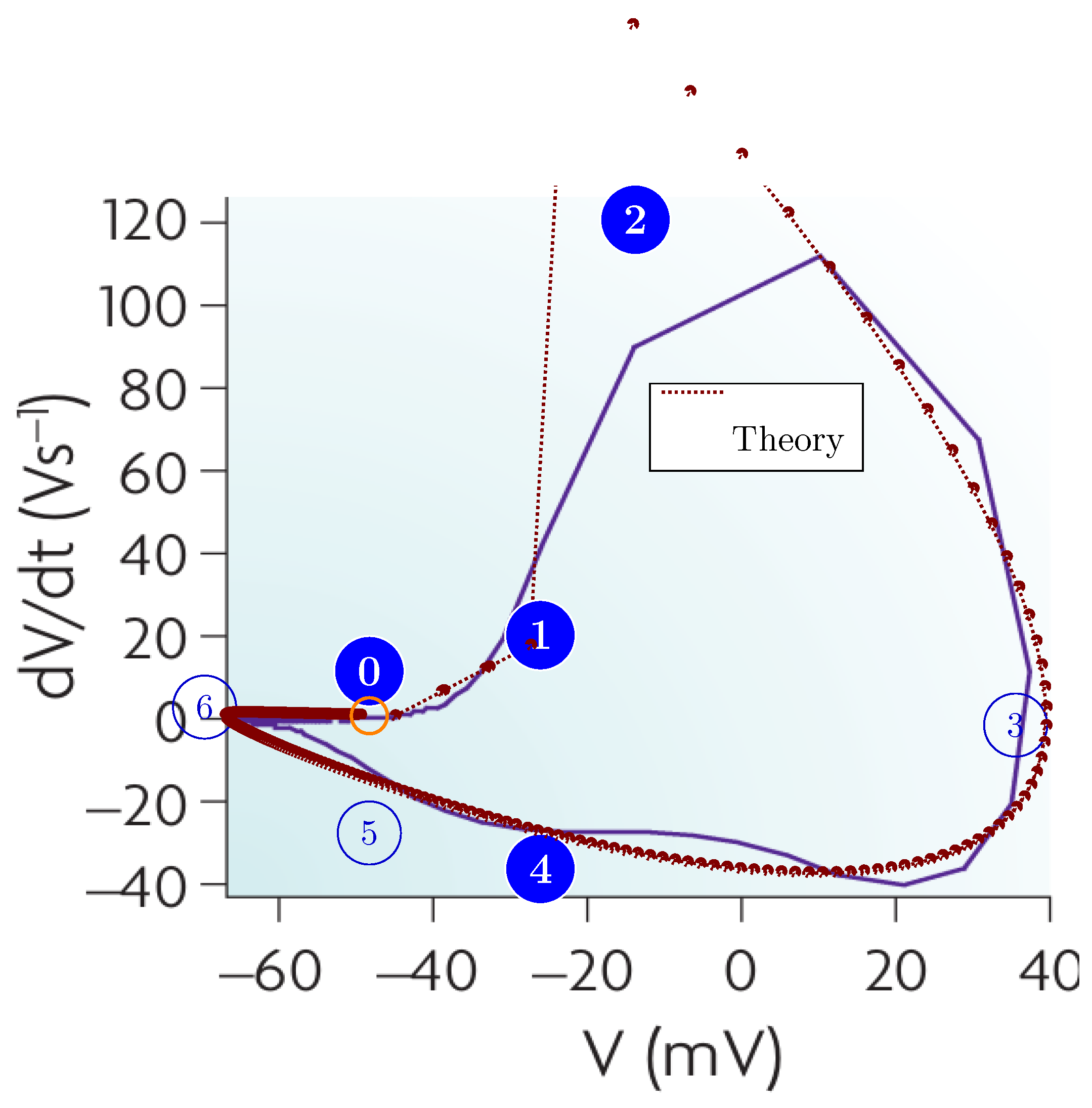

5.4. Mathematics of Spiking

5.5. Algorithm for the operation

| Algorithm 4 The main computation |

|

| Algorithm 5 The heartbeat computation |

|

5.6. Operating Diagrams

6. Summary

References

- Schrödinger, E. IS LIFE BASED ON THE LAWS OF PHYSICS? In What is Life?: With Mind and Matter and Autobiographical Sketches; Cambridge University Press: Canto, 1992; pp. 76–85. [Google Scholar]

- Végh, J. The non-ordinary laws of physics describing life. Physics A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2025, 1, in review. [CrossRef]

- Végh, J.; Berki, Á.J. Towards generalizing the information theory for neural communication. Entropy 2022, 24, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drukarch, B.; Wilhelmus, M. Thinking about the nerve impulse: A critical analysis of the electricity-centered conception of nerve excitability. Progress in Neurobiology 2018, 169, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drukarch, B.; Wilhelmus, M. Thinking about the action potential: the nerve signal as a window to the physical principles guiding neuronal excitability. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngai, J. BRAIN @ 10: A decade of innovation. Neuron 2024, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Brain Project. A closer look at scientific advances, 2023.

- Human Brain Project. New HBP-book: A user’s guide to the tools of digital neuroscience, 2023.

- Feynman, R.P. Feynman Lectures on Computation; CRC Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- von Neumann, J. The Computer and the Brain; Yale University Press: New Haven, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, L.; Sejnowski, T.J. Neural Codes and Distributed Representations; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, D.; Prokopenko, M.; Ray, J.C. Computation by natural systems. Interface Focus 2018, 8, 2025-03–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Végh, J.; Berki, A.J. Do we know the operating principles of our computers better than those of our brain? In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI); 2020; pp. 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehonic, A.; Kenyon, A.J. Brain-inspired computing needs a master plan. Nature 2022, 604, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Végh, J. On implementing technomorph biology for inefficient computing. Applied Sciences 2025, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, D.; Mizrahi, A.; Querlioz, D.; Grollier, J. Physics for neuromorphic computing. Nature Reviews Physics 2020, 2, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, D.; Wu, S.M.S. Foundations of Cellular Neurophysiology; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England, 1995.

- Kandel, E.R.; Schwartz, J.H.; Jessell, T.M.; Siegelbaum, S.A.; Hudspeth, A.J. Principles of Neural Science, 5 ed.; The McGraw-Hill Medical: New York Chicago etc., 2013.

- Hebb, D. The Organization of Behavior; Wiley and Sons: New York, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Caporale, N.; Dan, Y. Spike Timing–Dependent Plasticity: A Hebbian Learning Rule. Annual Review of Neuroscience 2008, 31, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Végh, J.; Berki, Á.J. On the Role of Speed in Technological and Biological Information Transfer for Computations. Acta Biotheoretica 2022, 70, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Végh, J. Introducing Temporal Behavior to Computing Science. In Proceedings of the Advances in Software Engineering, Education, and e-Learning; Arabnia, H.R., Deligiannidis, L., Tinetti, F.G., Tran, Q.N., Eds.; Springer International Publishing, 2021; pp. 471–491. [Google Scholar]

- Végh, J. Revising the Classic Computing Paradigm and Its Technological Implementations. Informatics 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, D.M.; McCulloch, W.S. The limiting information capacity of a neuronal link. The bulletin of mathematical biophysics 1952, 14, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sejnowski, J.T. The Computer and the Brain Revisited. Annals Hist Comput 1989, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Neumann, J. First draft of a report on the EDVAC. IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 1993, 15, 27–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nature. Documentary follows implosion of billion-euro brain project. Nature 2020, 588, 215–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemenman, I.; Lewen, G.D.; Bialek, W.; de Ruyter van Steveninck, R.R. Neural Coding of Natural Stimuli: Information at Sub-Millisecond Resolution. PLOS Computational Biology 2008, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backus, J. Can Programming Languages Be liberated from the von Neumann Style? A Functional Style and its Algebra of Programs. Communications of the ACM 1978, 21, 613–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, C.D.; Donovan, J.; Bunton, B.; Keist, A. SystemC: From the Ground Up, second ed.; Springer: New York, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Végh, J. Which scaling rule applies to Artificial Neural Networks. Neural Computing and Applications 2021, 33, 16847–16864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Végh, J. Finally, how many efficiencies the supercomputers have? The Journal of Supercomputing 2020, 76, 9430–9455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Végh, J. How Amdahl’s Law limits performance of large artificial neural networks. Brain Informatics 2019, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, G.; Rampone, S. Towards a HPC-oriented parallel implementation of a learning algorithm for bioinformatics applications. BMC Bioinformatics 2014, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, G.; Palmieri, F. Network traffic classification using deep convolutional recurrent autoencoder neural networks for spatial–temporal features extraction. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2021, 173, 102890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Végh, J. Why do we need to Introduce Temporal Behavior in both Modern Science and Modern Computing. Global Journal of Computer Science and Technology: Hardware & Computation 2020, 20/1, 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Végh, J. von Neumann’s missing "Second Draft": what it should contain. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI’20: December 16-18, 2020, Las Vegas, Nevada, USA. IEEE Computer Society, 2020, pp. 1260–1264. [CrossRef]

- hpcwire.com. TOP500: Exascale Is Officially Here with Debut of Frontier. Available online: https://www.hpcwire.com/2022/05/30/top500-exascale-is-officially-here-with-debut-of-frontier/ (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- van Albada, S.J.; Rowley, A.G.; Senk, J.; Hopkins, M.; Schmidt, M.; Stokes, A.B.; Lester, D.R.; Diesmann, M.; Furber, S.B. Performance Comparison of the Digital Neuromorphic Hardware SpiNNaker and the Neural Network Simulation Software NEST for a Full-Scale Cortical Microcircuit Model. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2018, 12, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Macedo Mourelle, L.; Nedjah, N.; Pessanha, F.G. Reconfigurable and Adaptive Computing: Theory and Applications; CRC press, 2016; chapter 5: Interprocess Communication via Crossbar for Shared Memory Systems-on-chip. [CrossRef]

- IEEE/Accellera. Systems initiative. 2017. Available online: http://www.accellera.org/downloads/standards/systemc.

- Brette, R. Is coding a relevant metaphor for the brain? The Behavioral and brain sciences 2018, 42, e215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somjen, G. SENSORY CODING in the mammalian nervous system; New York, MEREDITH CORPORATION, 1972. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. The Bell System Technical Journal 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizami, L. Information theory is abused in neuroscience. Cybernetics & Human Knowing 2019, 26, 47–97. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C.E. The Bandwagon. IRE Transactions in Information Theory 1956, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.R.; Dean, M.E.; Plank, J.S.; S. Rose, G. A Review of Spiking Neuromorphic Hardware Communication Systems. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 135606–135620. [CrossRef]

- Moradi, S.; Manohar, R. The impact of on-chip communication on memory technologies for neuromorphic systems. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics 2018, 52, 014003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, J.V. Principles of Neural Information Theory; Sebtel Press: Sheffield, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ruyter van Steveninck, R.R.; Lewen, G.D.; Strong, S.P.; Koberle, R.; Bialek, W. Reproducibility and Variability in Neural Spike Trains. Science 1997, 275, 1805–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, B.; Laughlin, S.; Niven, J. Consequences of Converting Graded to Action Potentials upon Neural Information Coding and Energy Efficiency. PLoS Comput Biol 2014, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, S.P.; Koberle, R.; de Ruyter van Steveninck, R.R.; Bialek, W. Entropy and Information in Neural Spike Trains. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 80, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sejnowski, T.J. The Computer and the Brain Revisited. IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 1989, 11, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, S., Ed. The Synaptic Organization of the Brain, 5 ed.; Oxford Academic, New York, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Berger, T.; Levy, W.B. A Mathematical Theory of Energy Efficient Neural Computation and Communication. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 2010, 56, 852–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brette, R. Simulation of networks of spiking neurons: a review of tools and strategies. J Comput. Neurosci., 23, 349–98. [CrossRef]

- Keuper, J.; Pfreundt, F.J. Distributed Training of Deep Neural Networks: Theoretical and Practical Limits of Parallel Scalability. In Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Machine Learning in HPC Environments (MLHPC). IEEE; 2016; pp. 1469–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsafrir, D. The Context-switch Overhead Inflicted by Hardware Interrupts (and the Enigma of Do-nothing Loops). In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2007 Workshop on Experimental Computer Science, San Diego, California, New York, NY, USA, 2007.

- David, F.M.; Carlyle, J.C.; Campbell, R.H. Context Switch Overheads for Linux on ARM Platforms. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2007 Workshop on Experimental Computer Science, San Diego, California, New York, NY, USA, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Bengio, E.; Bacon, P.L.; Pineau, J.; Precu, D. Conditional Computation in Neural Networks for faster models. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1511.06297 (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Xie, S.; Sun, C.; Huang, J.; Tu, Z.; Murphy, K. Rethinking Spatiotemporal Feature Learning: Speed-Accuracy Trade-offs in Video Classification. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision – ECCV 2018; Ferrari, V., Hebert, M., Sminchisescu, C., Weiss, Y., Eds.; 2018; pp. 318–335. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K.; Qin, M.; Sun, F.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.K.; Ren, F. Learning in the Frequency Domain. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Kunkel, S.; Schmidt, M.; Eppler, J.M.; Plesser, H.E.; Masumoto, G.; Igarashi, J.; Ishii, S.; Fukai, T.; Morrison, A.; Diesmann, M.; et al. Spiking network simulation code for petascale computers. Frontiers in Neuroinformatics 2014, 8, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.P.; Hennessy, J.L.; Gupta, A. Scaling Parallel Programs for Multiprocessors: Methodology and Examples. Computer 1993, 26, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowel, S.; Singer, W. Selection of intrinsic horizontal connections in the visual cortex by correlated neuronal activity. Science 1992, 255, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranmehr, E.; Shouraki, S.B.; Faraji, M.M.; Bagheri, N.; Linares-Barranco, B. Bio-Inspired Evolutionary Model of Spiking Neural Networks in Ionic Liquid Space. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2019, 13, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furber, S.B.; Lester, D.R.; Plana, L.A.; Garside, J.D.; Painkras, E.; Temple, S.; Brown, A.D. Overview of the SpiNNaker System Architecture. IEEE Transactions on Computers 2013, 62, 2454–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ousterhout, J.K. Why Aren’t Operating Systems Getting Faster As Fast As Hardware? 1990. Available online: http://www.stanford.edu/~ouster/cgi-bin/papers/osfaster.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Kendall, J.D.; Kumar, S. The building blocks of a brain-inspired computer. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2020, 7, 011305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TOP500. Top500 list of supercomputers. 2021. Available online: https://www.top500.org/lists/top500/ (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Han, S.; Pool, J.; Tran, J.; Dally, W.J. Learning both Weights and Connections for Efficient Neural Networks. 2015. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1506.02626.pdf.

- Liu, C.; Bellec, G.; Vogginger, B.; Kappel, D.; Partzsch, J.; Neumärker, F.; Höppner, S.; Maass, W.; Furber, S.B.; Legenstein, R.; et al. Memory-Efficient Deep Learning on a SpiNNaker 2 Prototype. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2018, 12, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.H., Information theory and neuroscience: Why is the intersection so small? In 2008 IEEE Information Theory Workshop; IEEE, 2008; pp. 104–108. [CrossRef]

- Leterrier, C. The Axon Initial Segment: An Updated Viewpoint. Journal of Neuroscience 2018, 38, 2135–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzsáki, G. Neural syntax: cell assemblies, synapsembles, and readers. Neuron 2010, 68, 362–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Végh, J. Why does the membrane potential of biological neuron develop and remain stable? The Journal of Membrane Biology 2025, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Levenstein, D.; Girardeau, G.; Gornet, J.; Grosmark, A.; Huszar, R.; Peyrache, A.; Senzai, Y.; Watson, B.; Rinzel, J.; Buzsáki, G. Distinct ground state and activated state modes of spiking in forebrain neurons. bioRxiv. 2021. Available online: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.09.20.461152v3.full.pdf.

- Hodgkin, A.L.; Huxley, A.F. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. J. Physiol. 1952, 117, 500–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschanz, J.W.; Narendra, S.; Ye, Y.; Bloechel, B.; Borkar, S.; De, V. Dynamic sleep transistor and body bias for active leakage power control of microprocessors. IEEE Journal of Solid State Circuits 2003, 38, 1838–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susi, G.; Garcés, P.; Paracone, E.; Cristini, A.; Salerno, M.; Maestú, F.; Pereda, E. FNS allows efficient event-driven spiking neural network simulations based on a neuron model supporting spike latency. Nature Scientific Reports 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onen, M.; Emond, N.; Wang, B.; Zhang, D.; Ross, F.M.; Li, J.; Yildiz, B.; del Alamo, J.A. Nanosecond protonic programmable resistors for analog deep learning. Science 2022, 377, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losonczy, A.; Magee, J. Integrative properties of radial oblique dendrites in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Neuron 2006, 50, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzsáki, G.; Mizuseki, K. The log-dynamic brain: how skewed distributions affect network operations. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2014, 15, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Végh, J. Physics-based electric operation and control of biological neurons. Biological Cybernetics 2025, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Végh, J. Dynamic Abstract Neural Computing with Electronic Simulation. 2025. Available online: https://jvegh.github.io/DANCES/ (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Kole, M.H.P.; Ilschner, S.U.; Kampa, B.M.; Williams, S.R.; Ruben, P.C.; Stuart, G.J. Action potential generation requires a high sodium channel density in the axon initial segment. Nature Neuroscience 2008, 11, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasband, M. The axon initial segment and the maintenance of neuronal polarity. Nat Rev Neurosci 2010, 11, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kole, M.; Stuart, G. Signal Processing in the Axon Initial Segment. Neuron 2012, 73, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.Y.M.; Rasband, M.N. Axon initial segments: structure, function, and disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2018, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Végh, J.; Berki, A.J. Revisiting neural information, computing and linking capacity. Mathematical Biology and Engineering 2023, 20, 12380–12403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antolini, A.; Lico, A.; Zavalloni, F.; Scarselli, E.F.; Gnudi, A.; Torres, M.L.; Canegallo, R.; Pasotti, M. A Readout Scheme for PCM-Based Analog In-Memory Computing With Drift Compensation Through Reference Conductance Tracking. IEEE Open Journal of the Solid-State Circuits Society 2024, 4, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso1, L.M.; Magnasco, M.O. Complex spatiotemporal behavior and coherent excitations in critically-coupled chains of neural circuits. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science 2018, 28, 093102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Tsien, J.Z. Neural Code-Neural Self-information Theory on How Cell-Assembly Code Rises from Spike Time and Neuronal Variability. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2017, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kneip, A.; Lefebvre, M.; Verecken, J.; Bol, D. IMPACT: A 1-to-4b 813-TOPS/W 22-nm FD-SOI Compute-in-Memory CNN Accelerator Featuring a 4.2-POPS/W 146-TOPS/mm2 CIM-SRAM With Multi-Bit Analog Batch-Normalization. IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circuits 2023, 58, 1871–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goikolea-Vives, A.; Stolp, H. Connecting the Neurobiology of Developmental Brain Injury: Neuronal Arborisation as a Regulator of Dysfunction and Potential Therapeutic Target. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa, K.; ichiro Kuwako, K. Molecular mechanisms regulating the spatial configuration of neurites. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 2022, 129, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, B. The action potential in mammalian central neurons. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2007, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).