1. Introduction

The discovery of Asgard archaea found in deep sea sediment near hydrothermal vents near Loki’s Castle by Spang and colleagues in 2015 [

2] has catalyzed a major shift in evolutionary biology, reconfiguring our foundational understanding of the Tree of Life [

3]. Since their initial discovery, Asgardians have also been found in other extreme environments, such as hot springs in Yellowstone National Park, Aarhus Bay, an aquifer near Colorado River, Radiata Pool, Taketomi Island Vent and the White Oak River Estuary [

3]. Traditionally, life was categorized into three domains—Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya. However, phylogenomic analyses now demonstrate that eukaryotes emerged from within the Archaea, specifically from a clade of complex archaea known as Asgardians [

1,

4,

5]. These organisms exhibit numerous eukaryotic signature proteins (ESPs), cytoskeletal elements, and membrane structures that suggest a continuum from simple prokaryotic forms to more complex eukaryotic cells [

5,

6]. This has led to the proposal of a revised, two-domain model of life, with the origins of Eukarya nested within Archaea [

4,

5].

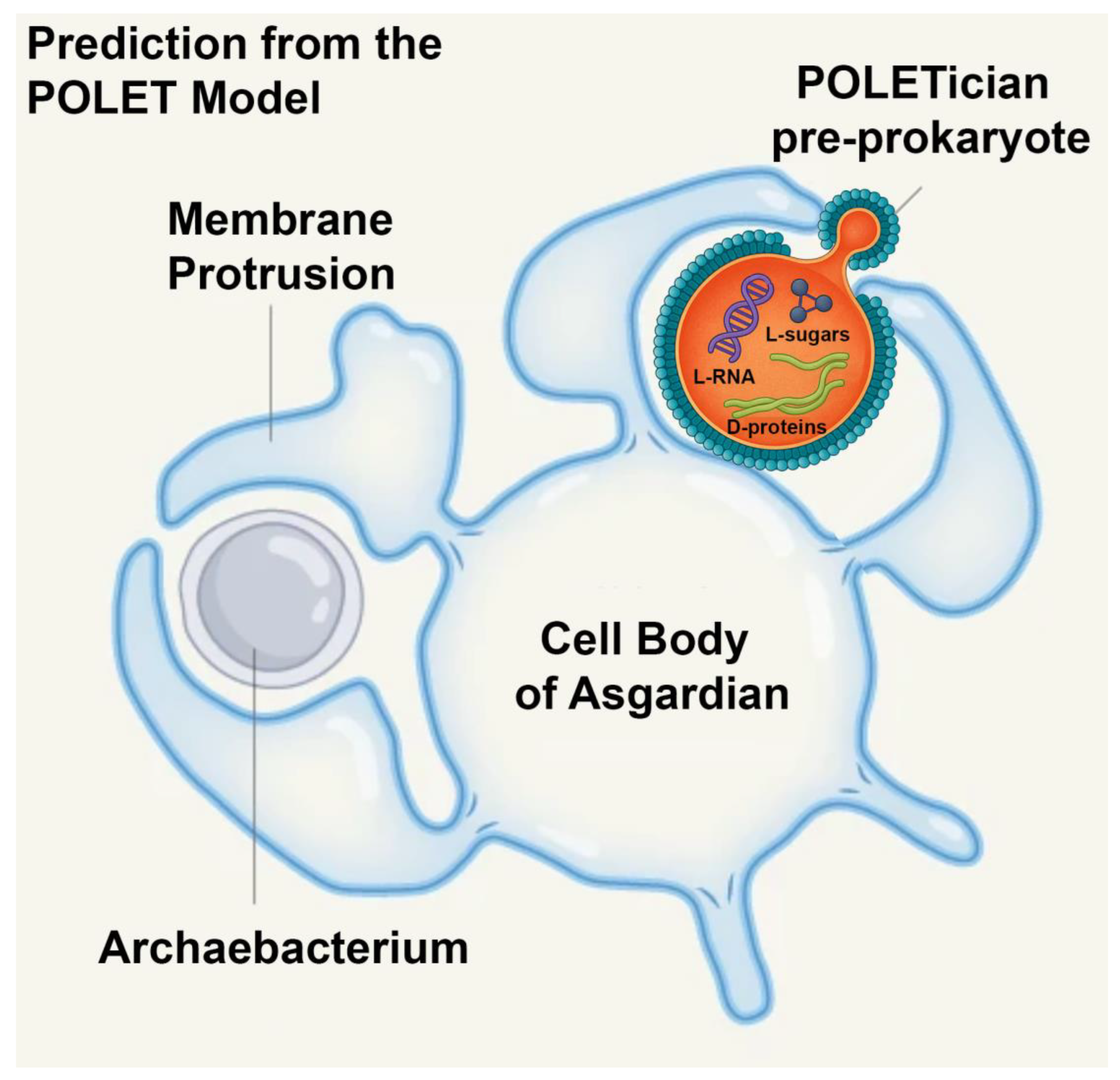

The implications of this discovery go beyond reshaping evolutionary trees. They open the possibility that other transitional forms—organisms bridging even earlier stages of life—might also still persist in Earth’s extreme environments. Building on this idea, we propose the POLET hypothesis (Preprokaryotic Organismal Lifeforms Existing Today), which posits that pre-cellular, membrane-bound entities resembling protocells may have survived the eons, residing undetected in deep anoxic muds and sediments, we call these hypothetical pre-prokaryotic organisms "POLETicians.”

Building on other theories for the origin of life, we envision POLETicians as ancient, slowly metabolizing membranous vesicles filled with primitive biochemical machinery. Instead of fast-acting enzymes, they may employ RNA–amino acid aptamers—relics of a primordial molecular system that predated the ribosome and even enzymes [

7,

8]. Lacking sophisticated metabolic networks, these entities could still grow and reproduce over extended periods, using blebbing-like mechanisms for division [

9]. Their distinctive biochemical composition—potentially incorporating both L- and D-amino acids as well as L- and D-RNAs due to their pre-enzymatic nature—along with extraordinarily long lifespans that could last centuries, sets them apart from all known forms of life. Energy may be derived from non-traditional sources such as radioactive decay or mineral-catalyzed redox gradients [

10]. The discovery of Asgardians also has ramifications for astrobiology. Panspermia (the origins of life on Earth were hitchhikers on asteroids) has been largely debunked because most present day “primitive” life can’t survive the intense heat and pressure experience when entering the Earth’s atmosphere [

11,

12], but no one has tried with Asgardians or the proposed POLETicians.

I propose that POLETicians could be identified by advanced imaging and analytical techniques such as chiral-sensitive mass spectrometry, fluorescence microscopy using membrane-selective dyes, and proteomics capable of detecting non-standard amino acids and aptamer-based translation. Both mirror L- and standard D-RNAs can be detected possibly by using existing RNA polymerases engineered to recognize non-standard bases [

13], or nanopores that can directly sequence both standard RNAs and modified RNAs [

14]. A mirror version of T7 RNA polymerase, a workhorse for molecular biology, has been constructed which allows direct synthesis of mirror RNAs and allows polymerase chain reaction of mirror RNAs [

15,

16]. Using mirror D-amino acid version of a thermostable DNA polymerase, polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) of mirror L-RNAs has been done [

17]. Generation of a mirror D-amino acid of a reverse transcriptase would allow the synthesis of mirror L-cDNAs which could be used in massively parallel next generation cDNA sequencing experiments to identify large amounts of environmental L-RNAs, should they exist. This is analogous to how Asgaridians were first discovered by sequencing large amounts of environmental DNA (eDNA) from the mud near Loki’s Castle [

3],

If discovered, POLETicians with mirror RNAs and mirror proteins would redefine our assumptions about the boundaries between prebiotic chemistry and life, positioning POLETicians as living fossils from the pre-cellular world. In this review,weexamine the evidence for this hypothesis, discuss potential detection strategies, and explore the implications for our understanding of life’s origins and continuity.

2. Preprokaryotic Organismal Lifeforms Existing Today (POLET) Hypothesis

This section explores the conceptual and hypothetical basis for the POLET hypothesis, which proposes the continued existence of ancient, pre-prokaryotic organisms known as POLETicians. These theoretical life forms may have survived in deep, anoxic environments, and exhibit a range of unique traits that distinguish them from known cellular life. We categorize these hypothetical features in the subsections below.

2.1. Longevity and Metabolic Quiescence

2.1.1. Lifespan Characteristics

POLETicians and other pre-prokaryotes (PPKs), if they exist today, may possess remarkably long lifespans, potentially existing hundreds or even thousands of years. Their longevity is hypothesized to be a consequence of minimal metabolic activity and extremely slow rates of molecular turnover. Unlike modern organisms, which rely on rapid biochemical cycles, POLETicians may persist in a near-static metabolic state, allowing for extraordinary durability under extreme conditions. Since their metabolism is incredibly slow, there would not be the need for modern efficient enzymes to catalyze fast reactions. Rather, formation of membranes and other structures could occur spontaneously, with precursors generated gradually by radioactive decay, redox processes, or catalysis on mineral surfaces [

9,

18,

19]. These processes operate at glacial paces but would suffice over the span of centuries or millennia.

The long dormancy of the hypothetical POLETicains could be somewhat like Daphnia (water fleas). When environmental conditions are right, Daphnia metabolism reduces down to near-zero and they enter a prolonged diapause. Researchers dig them up from soil cores that formed at the bottom of lakes, determine their age with isotopic analyses (some can be hundreds of years old), and “wake” them, and expose “ancient” genetic variants to present day environmental conditions to see how old genotypes fare in present day environments [

20]. If “ancient” POLETs could be discovered, the laboratory experimental potential is endless.

The hypothesis that POLETicians may possess extraordinarily long lifespans is partly inspired by the limited but intriguing data on the growth dynamics of Asgard archaea. These organisms, named after Norse mythology due to their initial discovery near the Loki's Castle hydrothermal vent [

2], exhibit exceptionally slow growth rates. In a landmark 2020 study, Imachi et al. successfully cultured the Lokiarchaeon strain MK-D1 from methane-seep sediments using a methane-fed continuous-flow bioreactor operated over 2,000 days [

5]. Following inoculation with casamino acids and antibiotics at 20 °C, faint cell turbidity was observed only after approximately one year. Strain MK-D1 displayed an extended lag phase of 30–60 days and required more than three months to reach cell densities of ~10⁵ 16S rRNA gene copies/mL, with a doubling time estimated at 14–25 days [

5]. After six transfers, MK-D1 reached 13% abundance within a tri-culture that also included Halodesulfovibrio (85%) and Methanogenium (2%). Fluorescence in situ hybridization and scanning electron microscopy revealed close physical associations among the three organisms [

5]. Subsequent enrichment steps eventually eliminated Halodesulfovibrio, resulting in a stable co-culture of MK-D1 and Methanogenium—achieved after 12 years of continuous cultivation [

5]. These findings suggest that, under natural conditions, Asgard archaea may grow and divide at extremely slow rates. By analogy, we hypothesize that POLETicians—putative pre-prokaryotic life forms—may exhibit even longer lifespans and slower metabolic activity, consistent with life in stable, low-energy environments such as the deep biosphere or those found in acidic environments in hot springs and geysers [

21].

2.2. Primitive Biochemistry and Genetic Mechanisms

2.2.1. Non-Enzymatic Catalysis

In the absence of modern enzymatic systems, POLETicians might utilize spontaneous chemical reactions or ribozymes to drive their biochemistry. This includes RNA molecules acting as structural templates, catalysts, and binding sites for amino acids [

8]. RNA–amino acid aptamers could represent a relic mechanism predating the ribosome, facilitating primitive forms of translation without full enzymatic machinery. Work by Yarus and colleagues has demonstrated a highly robust connection between certain amino acids and their cognate coding triplets within RNA binding sites, offering a possible mechanism by which the genetic code could have emerged from physicochemical interactions rather than biological evolution (

Table 1) [

8]. POLETicians, if discovered, could help validate or refine these theories. In the absence of enzymes, peptides formed by POLETs may incorporate both L- and D-amino acids and self-assemble into cytoskeletal structures, similar to how prions self-aggregate [

22]. Peptides can also self-assemble and form extracellular-like matrices that can mineralize with hydroxyapatite into structured arrays [

5]. The final two columns of

Table 1 show that many amino acid homopolymers—whose codons or anticodons correspond to their RNA aptamer binding sites—can self-assemble into beta-sheets, fibrils, or nanotubes, potentially serving as primitive cytoskeletal structures in early cellular systems (

Table 1).

2.3. Reproductive Strategy

2.3.1. Blebbing over Binary Fission

Rather than dividing by binary fission, POLETicians may reproduce through a primitive blebbing mechanism. As vesicle-like bodies slowly accumulate molecular components, they grow to a critical size and bud off smaller daughter vesicles. These blebs likely inherit random assortments of biochemical substrates—such as RNA fragments, amino acids, and primitive catalysts—reflecting the stochastic nature of early cellular division. This method bypasses the need for complex cytoskeletal or enzymatic machinery, making it plausible for prebiotic or minimally evolved life forms. Blebbing is increasingly recognized in origin-of-life theories as a potential primitive division strategy. Charras (2008) reviewed the biophysical basis of blebbing and proposed roles in early cellular dynamics [

23]. Fatty acid vesicles have been shown to divide spontaneously under prebiotic conditions, especially in the presence of mineral surfaces [

24]. For instance, Montmorillonite clays can catalyze both the formation of RNA polymers and the assembly of lipid vesicles, providing a dual scaffold for primitive cell-like structures [

24]. Metal sulfides may also stabilize vesicle membranes and facilitate redox-driven energy cycles [

19]. In POLETicians, membranes may incorporate racemic or non-biological lipids and lack modern homochirality. Some blebs may remain connected post-division, forming filamentous chains that support structural integrity and lineage tracking, offering a glimpse into early evolutionary strategies on prebiotic Earth.

2.4. Membrane Composition and Origin

2.4.1. Mineral-Assisted Membrane Assembly

Membranes in POLETicians may form through interactions with clay particles and metal ions in hydrothermal sediments. This supports models of abiogenesis that highlight the role of catalytic surfaces in early membrane formation. The lipid constituents of these membranes may not be modern phospholipids but instead less complex molecules such as fatty acids, monoglycerides, or fatty alcohols [

9]. Such amphiphiles are capable of self-assembling into micelles or bilayers under appropriate conditions and may offer enhanced stability in acidic or metal-rich environments. Unlike extant life, which exhibits homochirality in sugars (e.g., exclusively D-sugars in nucleotides), POLET membranes might contain both L- and D-sugars due to non-enzymatic, racemic assembly processes. Monnard and Deamer (2002) have discussed the viability of fatty acid vesicles under prebiotic conditions, reinforcing this model [

9].

2.5. Detectability of POLETicians

2.5.1. Analytical and Imaging Approaches

Detection of POLETicians may require advanced analytical tools. Mass spectrometry techniques, such as time-of-flight (TOF) systems capable of resolving chiral molecules, could distinguish unusual amino acid compositions. A MALDI-TOF/TOF (Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization – Time of Flight) approach has been used to demonstrate that D-amino acids can be detected in peptides and proteins [

25]. Fluorescent membrane dyes selective for non-standard lipid assemblies could facilitate microscopic identification of these entities in situ. Techniques like Raman spectroscopy, nanoSIMS (Secondary nanoscale Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry) [

26,

27], or high-resolution cryo-electron microscopy might also reveal subcellular structures or metabolic gradients [

28], helping to differentiate POLETicians from inert organic material or modern microbial life.

Perhaps the most promising strategy for detecting POLETicians—should they exist—would involve the identification of mirror L-RNAs using engineered RNA-directed RNA polymerases or reverse transcriptases. All extant terrestrial life relies exclusively on D-ribose nucleotides in RNA, a universal feature resulting from homochirality imposed by early enzymatic selection pressures [

29,

30]. However, in hypothetical pre-enzymatic systems such as POLETicians, this chiral constraint may not apply. As discussed by Yarus and colleagues, primitive ribozymes or RNA–amino acid aptamers could mediate early translation-like processes without a strict preference for D- or L-nucleotides [

8]. In such a system, mirror L-RNAs could function as informational molecules just as effectively as their D-counterparts. Detecting these alternative chiral forms would therefore provide a powerful marker for the presence of pre-prokaryotic biochemistry (see below).

The Asgard archaea themselves offer a precedent for discovering unusual lineages through non-traditional means. They were first identified not through microscopy or cultivation, but via metagenomic sequencing of environmental DNA extracted from deep-sea hydrothermal sediments near Loki’s Castle near the Artic Mid-Ocean Ridge [

2,

3]. It took over a decade to obtain the first cultured images of a member of this group, strain MK-D1, revealing unprecedented cellular structures and membrane features [

5]. Similarly, the discovery of POLETicians, should they exist, may depend not on direct imaging, but on the development of next-generation sequencing tools tailored to unconventional biomolecules. One promising route would involve adapting Oxford Nanopore Technologies’ (ONT’s) direct RNA sequencing platform to analyze mirror L-RNAs [

31]. The least expensive of the ONT DNA and RNA sequencers, the MINION, is a small hand-held device that you can plug into the thumb drive of a laptop computer, and they can sequence a drop of DNA or RNA in 24 to 48 hours. The major issue would be coverage given there would likely be large excesses of non-mirror D-RNAs that contaminate the sample and potentially interfere with the signals made by mirror L-RNAs, and the downstream bioinformatics would need to be developed for mirror L-RNAs.

This would require the development of novel mirror D-amino acid RNA helicases or RNA helicase adapters capable of recognizing mirror L-RNAs and feeding them through the nanopore—an engineering challenge, but not an insurmountable one given the precedent of other polymerase redesigns [

32,

33]. Specifically, the RNA helicase used in the ONT nanopore sequencer, a mutated version of a Hel308 helicase [

34], can be remade in the mirror form using D-amino acids, as was recently done with T7 RNA polymerase [

16]. The resulting nanopore signals, or “squigglegrams,” would differ from those produced by natural D-RNA due to the reversed backbone polarity and chirality. However, existing AI-based signal interpretation models could be retrained to decode these mirrored signal patterns [

35].

Mirror L-RNAs—also known as "Spiegelmers," from the German word Spiegel (mirror)—are of particular interest because they resist degradation by RNases and other cellular enzymes, making them attractive candidates in drug development [

36,

37]. Their biochemical stability and mirror-image architecture make them ideal molecular fossils if such entities were to persist in modern extreme environments. If POLETicians store or express information via Spiegelmer-like molecules, detecting them could offer not just evidence of a novel domain of life but also a window into prebiotic information systems. The successful identification of mirror L-RNAs in deep sediment samples would revolutionize our understanding of life’s origin and expand the biochemical space considered habitable—on Earth and beyond.

2.6. Ecological Niches and Interactions

2.6.1. Symbiotic Roles in Sediment Microbiomes

The discovery of Asgard archaea as obligate symbionts—particularly Lokiarchaeota strain MK-D1 co-cultured with Methanogenium—provides a compelling precedent for seeking POLETicians in similar symbiotic contexts [

5]. These ancient associations, revealed after over a decade of meticulous enrichment, suggest that such partnerships are not transient but deeply rooted in sediment microbiome ecology. POLETicians may occupy analogous niches, acting as ultraslow-growing symbionts within microbial consortia in anoxic sediments. They may interact metabolically with Asgard archaea or methanogens, exchanging small molecules or serving as scaffolds for redox buffering. Their hypothesized roles include stabilizing microenvironments by gradually absorbing and releasing redox-active species, thereby moderating geochemical fluctuations over multi-decade timescales. If POLETs persist at the edge of life, sedimentary ecosystems already known for harboring slow growing, metabolically integrated archaea may be among the most promising places to search.

2.7. Alternative Energy Acquisition

2.7.1. Redox and Radiolytic Metabolism

Energy acquisition in POLETicians likely bypasses photosynthesis and respiration. Instead, they may utilize electrons from radioactive decay, mineral-sourced redox gradients, or reactive radicals. These slow, low-yield energy processes may be sufficient for maintaining basic structural integrity and limited biosynthesis over millennia. Some deep subsurface bacteria have been shown to survive on radiolysis-derived hydrogen and sulfate for millions of years, lending credence to the feasibility of this mode of metabolism for ultra-slow life forms [

38,

39].

2.8. Implications for the Search for Life

2.8.1. A Broader Framework for Life's Emergence

If POLETicians exist, they imply that precursors to life might not be rare, singular events but instead widespread, persistent phenomena that span across compatible planetary environments. The global distribution of POLET-like entities would significantly increase the probability of life's emergence by enabling parallel evolutionary pathways. Their existence on Earth would also support targeted searches in extraterrestrial contexts—such as Mars, Europa, or Enceladus—where similar anoxic, mineral-rich, radiolytic environments may be found.

2.9. Redefining the Hallmarks of Life

2.9.1. Toward a POLET-Compatible Life Definition

Current definitions of life emphasize rapid replication, metabolism, and responsiveness. However, POLETicians would embody a form of life operating on vastly slower timescales and simpler biochemical rules. This necessitates a broader definition of life that includes long-lived, non-enzymatic, and blebbing-based systems. The study of POLETicians may ultimately reshape our taxonomy of living systems and reveal an intermediate domain bridging chemistry and biology.

Collectively, these expanded characteristics and implications reinforce the plausibility and scientific value of the POLET hypothesis. If POLETicians and PPKs are confirmed to exist, they would provide a transformative lens through which to understand the origins of life, both on Earth and potentially across the cosmos [

40].

2.9. Table

Table 1.

Probabilities that cognate coding triplets are unconcentrated in amino acid binding sites and fiber forming potentials of poly-amino acid homopolymers.

Table 1.

Probabilities that cognate coding triplets are unconcentrated in amino acid binding sites and fiber forming potentials of poly-amino acid homopolymers.

| Amino acid |

Codon |

PCodon |

Anticodon |

PAnticodon |

Fiber Forming Potential |

Notes |

Refs. |

| L-Arg |

CGG |

4.0 x 10-3 |

CCG |

1 |

Weakly with PEG-Q11 |

Electrostatic repulsion may prevent stable fiber formation alone |

[41] |

| L-Arg |

CGA |

1 |

UCG |

3.4 x 10-5 |

weak |

See above. |

[41] |

| L-Gln |

CAA |

0.16 |

UUG |

1 |

Amyloid fibers |

PolyQ diseases |

[42] |

| L-His |

CAC |

0.40 |

GUG |

6.4 x 10-8 |

Has cell penetrating properties |

Aggregate under certain pH conditions |

[43] |

| L-Ile |

AUU |

4.8 x 10-109 |

AAU |

1 |

-sheets and amyloids |

Contributes to amyloid-like structures |

[44] |

| L-Leu |

CUA |

1 |

UAG |

0.07 |

-sheets |

hydrophobic |

|

| Phe |

UUU |

1 |

AAA |

0.047 |

Nanotubes/fibers |

Aromatic stacking |

[45] |

| Phe |

UUC |

1 |

GAA |

2.2 x 10-4 |

Nanotubes/fibers |

π–π stacking drives aggregation |

[45] |

| Trp |

UGG |

1 |

CCA |

5.5 x 10-13 |

Forms nanostructured micelles |

π–π stacking drives aggregation |

[46] |

| Tyr |

UAU |

0.10 |

AUA |

2.4 x 10-5

|

Fibrils |

Forms fibrils via aromatic and hydrogen bonding interactions. |

[45] |

| Tyr |

UAC |

0.016 |

GUA |

8.0 x 10-3

|

Fibrils |

See above |

[45] |

3. Discussion

The originally inactive liquid possesses a sensible rotatative power to the left, which increases little by little and reaches a maximum. At this point, fermentation is suspended. There is no longer a trace of right-acid in the liquid. Louis Pasteur (1860) [

47].

The above quotation is from Louis Pasteur in a book published in 1860 describing his earlier discovery in the 1820s, which he made only a few years after receiving his two PhDs [

47]. He noticed that a racemic mixture of ammonium tartrate underwent fermentation by yeast until only D-ammonium tartrate remained. In other words, yeast was only able to metabolize L-ammonium tartrate and not D-ammonium tartrate. For this and other work, such as the L-chirality of the protein albumin, Louis Pasture has been called the Father of Molecular Chirality” [

48]. The POLET hypothesis proposes Pasteur might have missed the existence of life with mirror chiral preferences because he did not study organisms in extreme environments that might produce mirror D-amino acid proteins and metabolism mirror metabolites such as D-ammonium tartrate.

The POLET hypothesis also builds on recent discoveries of Asgard archaea, which themselves have redefined our understanding of eukaryotic origins by linking eukaryotes more directly to the archaeal domain [

5]. If such evolutionary intermediates are extant, it is plausible to hypothesize that even more ancient precursors—preprokaryotic forms like POLETicians—may also persist in isolated, anoxic environments. These hypothetical organisms provide an intriguing new angle in the study of life’s origin, shifting focus from reconstituting early life solely through laboratory synthesis or fossil records to potentially identifying extant, relic life forms. We acknowledge that extant POLETicians, should they exist, may different from ancient ones. We also acknowledge that extant preprokaryotes (PPKs) may have moved beyond that achiral stage and that only chiral organisms with non-mirror D-RNAs and L-amino acids exist today. Nevertheless, the search for achiral POLETicians we feel is worth it given the high risk and even higher rewards of proving this hypothesis.

The proposed characteristics of POLETicians are consistent with long-standing theories in origin-of-life research. For instance, the use of mineral-assisted membrane assembly echoes early work on the catalytic role of clays and metal ions in abiogenesis [

9]. Similarly, the concept of RNA-based catalysis predates modern enzymology and aligns with the RNA World hypothesis [

8]. What distinguishes POLET is the suggestion that these systems are not only ancient but still active, albeit at geologically slow timescales.

Emerging technologies in mass spectrometry and fluorescence imaging open new possibilities for empirical investigation. Techniques capable of resolving chirality and detecting non-standard lipid structures could offer unprecedented insight into these potential life forms. Moreover, deep-sea sediment cores and hydrothermal vent environments provide accessible natural laboratories where POLETicians might be discovered.

The global distribution of POLETs would significantly increase the probability of life's origin on Earth. Rather than requiring a singular, unique location for abiogenesis, a widespread network of POLET-like entities would represent parallel experiments in life's emergence. This broader distribution supports a statistical advantage for life initiating multiple times or sustaining itself in various prebiotic niches.

Furthermore, if POLETicians are discovered and characterized, their biochemical and structural signatures could be sought in extraterrestrial samples. Mars, Europa, Enceladus, and other icy moons with subsurface oceans and geochemical energy sources are ideal candidates for future investigations. If POLET-like markers are detected, it would lend strong support to the universality of certain prebiotic processes.

Importantly, the proposed extreme longevity of POLETicians means that conventional definitions of life—such as growth and reproduction within short timescales—may need revision. Enzyme-free metabolic processes, decades-long division cycles, and near-metabolic stasis fall outside current biological paradigms. This challenges researchers to redefine the hallmarks of life to include such ancient and slow-evolving forms.

Due to their proposed exceptionally long lifespans and rare division events, culturing POLETicians in laboratory conditions may prove impractical. Instead, studying them in situ or through indirect lineage tracing—by analyzing age gradients or molecular changes in daughter vesicles—could provide critical insights into their life cycle and molecular evolution.

4. Conclusions

The POLET hypothesis posits that precursors to the origin of life may still exist today in the form of POLETicians—hypothetical, slow-dividing, membrane-bound entities predating prokaryotic cells. These life forms may hold critical clues to understanding how life transitioned from chemistry to biology. Their proposed characteristics, such as non-enzymatic catalysis, blebbing reproduction, radiolytic energy use, and ultra-long lifespans, not only align with prebiotic models but also suggest novel forms of life that challenge current biological definitions.

If confirmed, the existence of POLETicians would represent one of the most significant biological discoveries of the century, with profound implications for evolutionary biology, astrobiology, and the search for extraterrestrial life. While currently speculative, the POLET hypothesis provides a testable framework for identifying ancient life forms that may still persist in the shadows of modern biospheres. Their discovery, or the discovery of other ancient bacteria, could expand the tree of life backward, providing a missing link to life’s earliest roots and potentially uncovering similar systems beyond Earth.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, grant numbers 5UG3OD023285, 5P42ES030991, and 1P30ES036084.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author used ChatGPT4 for the purposes of increasing the clarity of the text. The author has reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| POLET |

Precursors to the origin of life exist today |

| PPK |

Pre-prokaryrotes |

| ESP |

Eukaryotic Signature Proteins |

References

- MacLeod, F., et al., Asgard archaea: Diversity, function, and evolutionary implications in a range of microbiomes. AIMS Microbiol, 2019. 5(1): p. 48-61. [CrossRef]

- Spang, A., et al., Complex archaea that bridge the gap between prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Nature, 2015. 521(7551): p. 173-179. [CrossRef]

- Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka, K., et al., Asgard archaea illuminate the origin of eukaryotic cellular complexity. Nature, 2017. 541(7637): p. 353-358. [CrossRef]

- Fournier, G.P. and A.M. Poole, A Briefly Argued Case That Asgard Archaea Are Part of the Eukaryote Tree. Front Microbiol, 2018. 9: p. 1896. [CrossRef]

- Imachi, H., et al., Isolation of an archaeon at the prokaryote-eukaryote interface. Nature, 2020. 577(7791): p. 519-525. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., et al., Expanded diversity of Asgard archaea and their relationships with eukaryotes. Nature, 2021. 593(7860): p. 553-557. [CrossRef]

- Koonin, E.V. and A.S. Novozhilov, Origin and Evolution of the Universal Genetic Code. Annu Rev Genet, 2017. 51: p. 45-62. [CrossRef]

- Yarus, M., J.J. Widmann, and R. Knight, RNA-amino acid binding: a stereochemical era for the genetic code. J Mol Evol, 2009. 69(5): p. 406-29. [CrossRef]

- Monnard, P.A. and D.W. Deamer, Membrane self-assembly processes: steps toward the first cellular life. Anat Rec, 2002. 268(3): p. 196-207. [CrossRef]

- Schafer, G., M. Engelhard, and V. Muller, Bioenergetics of the Archaea. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev, 1999. 63(3): p. 570-620. [CrossRef]

- Cockell, C.S., et al., Interplanetary transfer of photosynthesis: an experimental demonstration of a selective dispersal filter in planetary island biogeography. Astrobiology, 2007. 7(1): p. 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, Y., et al., The possible interplanetary transfer of microbes: assessing the viability of Deinococcus spp. under the ISS Environmental conditions for performing exposure experiments of microbes in the Tanpopo mission. Orig Life Evol Biosph, 2013. 43(4-5): p. 411-28. [CrossRef]

- Oh, J., et al., Structural basis of transcription recognition of a hydrophobic unnatural base pair by T7 RNA polymerase. Nat Commun, 2023. 14(1): p. 195.

- Wu, Y., et al., Transfer learning enables identification of multiple types of RNA modifications using nanopore direct RNA sequencing. Nat Commun, 2024. 15(1): p. 4049.

- Service, R.F., A big step toward mirror-image ribosomes. Science, 2022. 378(6618): p. 345-346.

- Xu, Y. and T.F. Zhu, Mirror-image T7 transcription of chirally inverted ribosomal and functional RNAs. Science, 2022. 378(6618): p. 405-412.

- Pech, A., et al., A thermostable d-polymerase for mirror-image PCR. Nucleic Acids Res, 2017. 45(7): p. 3997-4005.

- Lopez-Garcia, P. and D. Moreira, The Syntrophy hypothesis for the origin of eukaryotes revisited. Nat Microbiol, 2020. 5(5): p. 655-667.

- Wachtershauser, G., Before enzymes and templates: theory of surface metabolism. Microbiol Rev, 1988. 52(4): p. 452-84.

- Yousey, A.M., et al., Resurrected 'ancient' Daphnia genotypes show reduced thermal stress tolerance compared to modern descendants. R Soc Open Sci, 2018. 5(3): p. 172193. [CrossRef]

- Tamarit, D., et al., A closed Candidatus Odinarchaeum chromosome exposes Asgard archaeal viruses. Nat Microbiol, 2022. 7(7): p. 948-952. [CrossRef]

- Jaunmuktane, Z. and S. Brandner, Invited Review: The role of prion-like mechanisms in neurodegenerative diseases. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol, 2020. 46(6): p. 522-545.

- Charras, G.T., A short history of blebbing. J Microsc, 2008. 231(3): p. 466-78.

- Hanczyc, M.M., S.M. Fujikawa, and J.W. Szostak, Experimental models of primitive cellular compartments: encapsulation, growth, and division. Science, 2003. 302(5645): p. 618-22.

- Koehbach, J., et al., MALDI TOF/TOF-Based Approach for the Identification of d- Amino Acids in Biologically Active Peptides and Proteins. J Proteome Res, 2016. 15(5): p. 1487-96. [CrossRef]

- Schaible, G.A., et al., Comparing Raman and NanoSIMS for heavy water labeling of single cells. bioRxiv, 2025.

- Weber, P.K., et al., The NanoSIMS-HR: The Next Generation of High Spatial Resolution Dynamic SIMS. Anal Chem, 2024. 96(49): p. 19321-19329. [CrossRef]

- Chari, A. and H. Stark, Prospects and Limitations of High-Resolution Single-Particle Cryo-Electron Microscopy. Annu Rev Biophys, 2023. 52: p. 391-411.

- Blackmond, D.G., The origin of biological homochirality. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2010. 2(5): p. a002147. [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, S.F., et al., Origin of biological homochirality by crystallization of an RNA precursor on a magnetic surface. Sci Adv, 2023. 9(23): p. eadg8274.

- Jain, M., et al., Advances in nanopore direct RNA sequencing. Nat Methods, 2022. 19(10): p. 1160-1164. [CrossRef]

- Ellefson, J.W., et al., Synthetic evolutionary origin of a proofreading reverse transcriptase. Science, 2016. 352(6293): p. 1590-3.

- Nikoomanzar, A., et al., Engineering polymerases for applications in synthetic biology. Q Rev Biophys, 2020. 53: p. e8.

- Wang, Y., et al., Nanopore sequencing technology, bioinformatics and applications. Nat Biotechnol, 2021. 39(11): p. 1348-1365.

- Rang, F.J., W.P. Kloosterman, and J. de Ridder, From squiggle to basepair: computational approaches for improving nanopore sequencing read accuracy. Genome Biol, 2018. 19(1): p. 90.

- Bethge, L. and S. Vonhoff, Pegylation of RNA Spiegelmers by a Novel Widely Applicable Two-Step Process for the Conjugation of Carboxylic Acids to Amino-Modified Oligonucleotides. Curr Protoc Nucleic Acid Chem, 2020. 81(1): p. e109.

- Vater, A. and S. Klussmann, Toward third-generation aptamers: Spiegelmers and their therapeutic prospects. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel, 2003. 6(2): p. 253-61.

- Blair, C.C., et al., Radiolytic hydrogen and microbial respiration in subsurface sediments. Astrobiology, 2007. 7(6): p. 951-70. [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, A.A., et al., Radiolytic Effects on Biological and Abiotic Amino Acids in Shallow Subsurface Ices on Europa and Enceladus. Astrobiology, 2024. 24(7): p. 698-709.

- Tarnas, J.D., et al., Earth-like Habitable Environments in the Subsurface of Mars. Astrobiology, 2021. 21(6): p. 741-756.

- Kelly, S.H., et al., Titrating Polyarginine into Nanofibers Enhances Cyclic-Dinucleotide Adjuvanticity in Vitro and after Sublingual Immunization. ACS Biomater Sci Eng, 2021. 7(5): p. 1876-1888. [CrossRef]

- Chiti, F. and C.M. Dobson, Protein misfolding, functional amyloid, and human disease. Annu Rev Biochem, 2006. 75: p. 333-66.

- Lee, H.J., et al., Polyhistidine facilitates direct membrane translocation of cell-penetrating peptides into cells. Sci Rep, 2019. 9(1): p. 9398.

- Maury, C.P., Self-propagating beta-sheet polypeptide structures as prebiotic informational molecular entities: the amyloid world. Orig Life Evol Biosph, 2009. 39(2): p. 141-50.

- Parween, S., et al., Self-assembled dipeptide nanotubes constituted by flexible beta-phenylalanine and conformationally constrained alpha,beta-dehydrophenylalanine residues as drug delivery system. J Mater Chem B, 2014. 2(20): p. 3096-3106.

- Chou, S., et al., Synthetic peptides that form nanostructured micelles have potent antibiotic and antibiofilm activity against polymicrobial infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2023. 120(4): p. e2219679120. [CrossRef]

- Pasteur, L., Researches on the molecular asymmetry of natural organic products. Alembic club reprints. 1906, Edinburgh: The Alembic Club ; Chicago : University of Chicago Press. 46 p.

- Vantomme, G. and J. Crassous, Pasteur and chirality: A story of how serendipity favors the prepared minds. Chirality, 2021. 33(10): p. 597-601. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).