1. Introduction

GBM is the most common and aggressive primary malignant brain tumour in adults, accounting for approximately 45% of all malignant primary brain tumors. In addition to the direct effects of the tumour, GBM patients are at increased risk of developing systemic complications, one of the most significant being VTE. VTE, which includes both DVT and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a known complication in patients with GBM and other malignancies. The incidence of VTE in GBM patients has been reported to vary widely in the literature, with estimates ranging from as low as 3% to as high as 60% [

1,

2,

3].

Initially, it was believed that the risk of developing VTE was highest during the first few months following diagnosis and surgical intervention [

4]. However, more recent studies have demonstrated that the risk remains elevated throughout the course of the disease [

1]. This complication significantly impacts the quality of life and overall survival of GBM patients, especially when complicated by PE, which is a leading cause of death in cancer patients.

One of the challenges in managing VTE risk in GBM patients is whether to use prophylactic anticoagulation. While anticoagulation can reduce the risk of thromboembolic events, it is not routinely recommended for GBM patients due to the potential risk of intracranial hemorrhage. Therefore, identifying which patients are at the highest risk of developing VTE could help inform clinical decisions regarding the use of prophylactic anticoagulation and closer monitoring to detect VTE, potentially improving outcomes in this vulnerable population.

Unfortunately, there are presently no reliable tools available to accurately identify high-risk individuals for VTE in GBM patients. The only validated risk assessment score for chemotherapy-treated cancer patients with solid tumors, the Khorana score, is not adequately powered for use in patients with brain tumours [

5]. Multiple factors are associated with an elevated risk of thrombosis in GBM patients, including a combination of patient-related, tumour-related, and treatment-related factors. Patient-related risks include older age, obesity, immobility (particularly due to leg paresis), and a history of VTE [

6,

7]. Tumour-related factors include larger tumor size and histologic subtype, with GBM presenting a higher risk compared to lower-grade gliomas [

1,

6]. Treatment-related risks include procedures leaving significant residual tumour, such as tumour biopsy and subtotal resection, and the use of corticosteroids or bevacizumab [

1,

8].

Given the gaps in the current literature, the objective of this study was to examine the incidence of VTE in newly diagnosed GBM patients, with a focus on the associated risk factors. By conducting a retrospective chart review, we sought to provide insights into the timing of VTE occurrence, and the clinical characteristics that may predispose patients to these events, which might give insight to the potential benefits of prophylactic anticoagulation.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a single-centre, retrospective cohort study of newly diagnosed GBM patients, 18 years or older, at the Juravinski Cancer Centre (JCC) in Hamilton, Canada. The JCC is a tertiary care centre, with a catchment area of 2.5 million people, located in southeastern Ontario. All patients diagnosed between January 1, 2013 to December 31, 2020 were reviewed. Patients without a pathological diagnosis at the time of data collection were excluded.

2.1. Disease and Patients’ Characteristics

Data on the the following patient characteristics at diagnosis were collected: age, gender, bodymass index (BMI) , Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) , functional deficits (weakness) , co-morbidities (previous history of VTE or cancer, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, smoking history), along with the disease characteristics, including tumour anatomic location and size, type of treatment, use of bevacizumab, presence of an intravenous catheter or venacaval filter, date of diagnosis, time to progression, and time to death or last follow-up. Laboratory parameters assessed at baseline included leucocyte, hemoglobin and platelet count. The diagnosis of VTE was confirmed by ultrasound or CT scan along with the type of anticoagulants used, and development of bleeding while on treatment. Using the Khorana score [

5], patients were grouped by a score of 2 (intermediate risk) versus

>3 (high risk).

2.2. Statistical Analyses

Demographic, clinical, surgical, pathological, and radiological data and outcomes were analyzed by descriptive statistics. Time to VTE was calculated using cumulative incidence methods, adjusting for the competing risk of death. Competing risk regression was performed to explore the potential prognostic effect of factors on the cumulative incidence of VTE. Forward stepwise selection was used to construct a multivariable model. Two-sided, 95% confidence intervals were constructed for outcomes of interest. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value of 0.05 or less.

2.3. Ethics

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

A total of 528 patients diagnosed with GBM were included in this study. The patient characteristics are summarized in

Table 1. The median age at diagnosis was 65 with 43.6% being female, 56.4% male. 80% of the patients had a KPS of 50 or greater and 80% of the patients underwent surgical resection, either a gross total resection or subtotal resection, with the remainder having only a biopsy. 80.2% of patients received active treatment and 9.7% received bevacizumab at some point during their treatments.

3.2. Characterization of the VTE Cohort

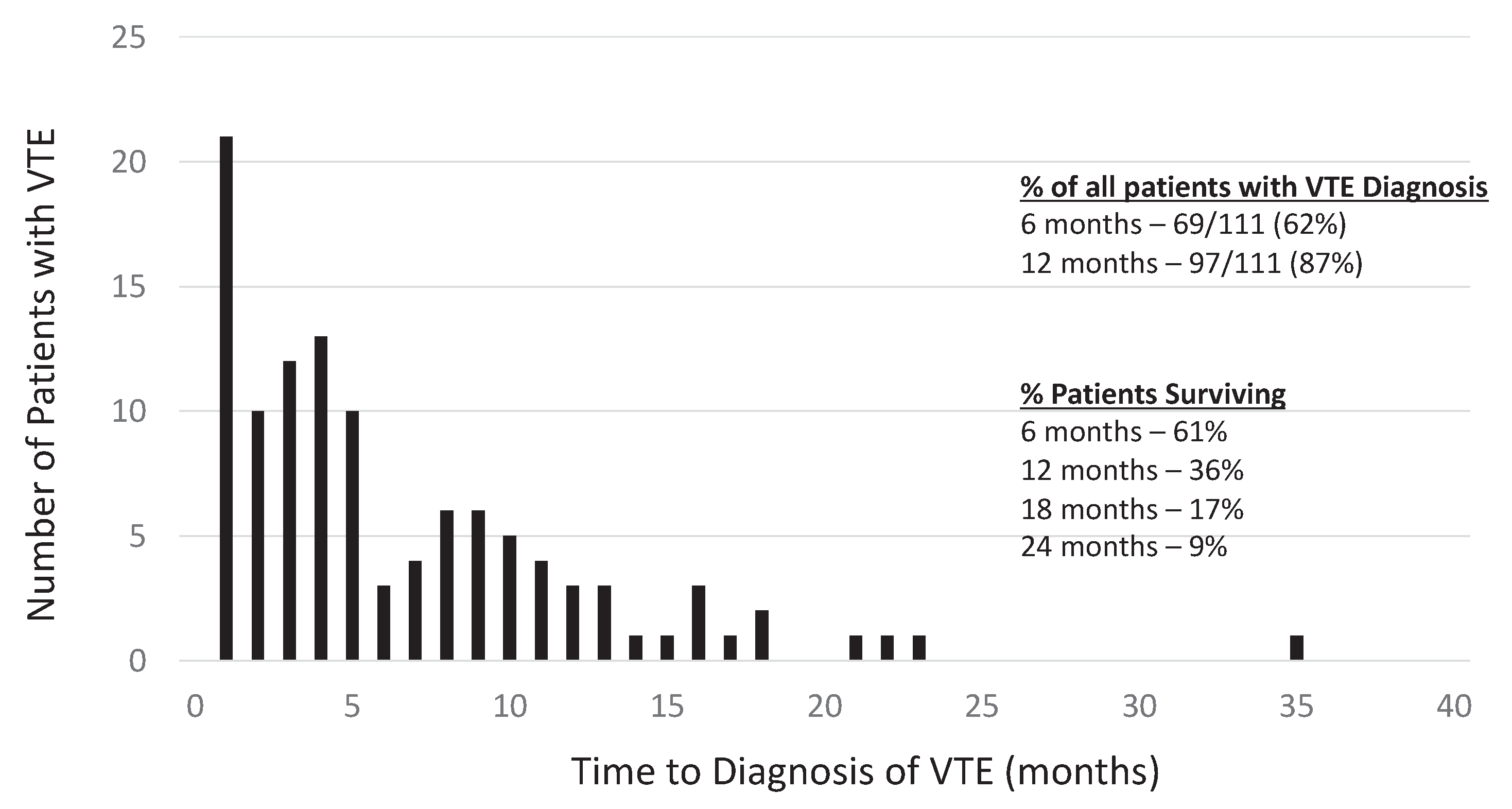

Among the 528 patients studied, 111 patients (21%) were diagnosed with a VTE during the outlined period. Most of the VTE were diagnosed within 12 months of diagnosis of GBM (87%), with 62% being diagnosied in the first 6 months (

Figure 1).

The cumulative incidence of VTE adjusted for the competing risk of death was 13.5% (95% CI=10.7% to 16.6%) at 6 months, 18.8% (15.5% to 22.4%) at 12 months and 23.2% (19.5% to 27.1%) at 24 months.

The location of VTE was as follows: 39 patients (35%) unilateral lower extremity, 8 (7%) unilateral upper extremity, 8 (7%) bilateral lower extremity, 30 (27%) PE, and 25 (23%) DVT and PE. Among these patients, less than 4% of the cases were thought to be catheter related. Intracerebral bleeding developed in 8.3% and other bleeding in 9.5% of the cases while on anticoagulants (see

Table 2).

Results of the competing risk regression are shown in

Table 3. Having a history of cancer (HR=1.33, 95% CI=1.01 to 1.75, p-value=0.045) and recurrence/progression (RP) (HR=1.61, 95% CI=1.11 to 2.36, p-value=0.013) were the only statistically significant prognostic factors, however, weakness at baseline (HR=0.72 for 7 vs <7, 0.49 to 1.04, p-value=0.080) and platelet count (HR=0.35 for

>350 vs <350, 0.11 to 1.13, p-value=0.079) both approached significance. Using stepwise selection, after RP entered the model, no other factor was statistically significant.

4. Discussion

The development of VTE is a common event in patients with GBM. Survival and quality of life are negatively impacted by the development of VTE, particularly if it is complicated by PE. It associated with a 30% increase in the risk of death within 2 years. The risk of developing VTE is reported to be up to 20% in patients with a brain tumor [

1,

9].

This retrospective cohort study of 528 GBM patients investigated the incidence and clinical characteristics of patients with VTE, providing valuable insights into its occurrence and the associated risk factors in this population. Approximately 21% of newly diagnosed GBM patients developed VTE, with 2-year cumulative incidence rates of 23.2%, aligning with rates reported in previous studies[

1,

2,

3,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Notably, VTE incidence was highest within the first year of diagnosis, with 62% of cases occurring in the first six months.

In the current study, we examined multiple parameters previously reported as risk factors for VTE in patients with GBM. Brandes et al. identified limb paresis and advanced age as significant predictors of VTE in high-grade glioma patients, attributing the increased risk to venous stasis resulting from immobility associated with paresis [

6]. Similarly, Marras et al. reported advanced age, extended surgical duration, and larger tumor size as contributors to VTE risk, noting that prolonged surgery may exacerbate blood flow disruption and immobility [

1]. Additionally, recent studies have highlighted the role of inflammatory and metabolic markers, such as elevated tissue factor and podoplanin levels in IDH wild-type gliomas, in promoting a hypercoagulable state [

13]. Elevated white blood cell counts and body mass index have also been associated with increased VTE risk, implicating systemic inflammation and metabolic dysregulation as contributing factors [

7]. Despite these findings in the literature, our analysis identified only RP and history of previous cancer as significant prognostic variables for the risk of VTE. The correlation between VTE development and prognosis for survival remains ambiguous [

10,

14].

Despite the high incidence of thrombosis, routine prophylactic anticoagulation to all patients with GBM has not been recommended due to the potential risk of intracranial bleeding or insufficient evidence about its influence on survival. A meta-analysis of ten randomized controlled studies, including 1263 patients with primary brain tumors undergoing craniotomy, analysed the benefit–risk ratio of several prophylactic VTE measures [

15]. It was found that prophylactic VTE measures lead to a significantly lower risk of VTE while not causing a major increase in bleeding. Patients receiving unfractionated heparin alone had a stronger risk reduction in VTE than patients receiving placebo (RR = 0.27; 95% CI 0.1–0.73) and low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) with mechanical prophylaxis together showed a lower VTE risk than mechanical prophylaxis alone (RR = 0.61; 95% CI 0.46–0.82).

The PRODIGE trial, a phase III randomized, placebo-controlled trial, evaluated the efficacy and safety of dalteparin for preventing VTE in patients with newly diagnosed malignant glioma [

16]. It revealed that primary prophylaxis with LMWH showed a trend toward reduced VTE and increased intracranial bleeding without affecting survival. Unfortunately, the trial was terminated early due to poor accrual and the expiration of the patent on the study medication. The AVERT study examined the preventive benefit of administering a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) to cancer patients, including those with GBM, at high risk of developing VTE [

17]. The study, which included 574 patients, compared apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily versus placebo for long-term prophylaxis of VTE in cancer patients. In this study, a significant reduction of VTE in the apixaban group compared to placebo (4.2% versus 10.2%) was found. Of the patients included in the apixaban group, 4.8% had a brain tumor compared to 3.5% of the patients in the placebo group. During the treatment period, major bleeding occurred in 6 patients (2.1%) in the apixaban group and in 3 patients (1.1%) in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 1.89; 95% CI, 0.39 to 9.24). However, patients with GBM as a subgroup were not analyzed.

As the role of prophylactic anticoagulation for all patients is debatable, identifying those at high risk of developing VTE would potentially allow for the targeted use of preventive anticoagulation to lower the risk of thrombosis. Lim et al [

10], performed a retrospective study aimed at formulating a practical scoring system to predict the risk of VTE in GBM patients undergoing chemoradiotherapy. The scoring system included the parameters of age, KPS, smoking history and hypertension. Patients with a cumulative score of more than 2 points were identified as having a significantly increased risk of symptomatic VTE, with a fivefold higher likelihood compared to those scoring 2 or fewer points. However, since only 115 patients were evaluated in this study, this scoring system requires further validation in larger prospective cohorts to confirm its utility and accuracy in clinical practice.

Newer DOACs, such as rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban, offer the advantage of oral administration without the need for frequent monitoring. These agents have demonstrated efficacy comparable to LMWH in the treatment and prophylaxis of VTE in cancer patients [

18,

19]. However, the risk of significant bleeding is slightly higher with DOACs [

18,

19,

20]. This has led to cautious exploration of DOACs in GBM, a population at heightened risk for intra-cranial hemorrhage (ICH). Dubinski et al. conducted a retrospective analysis and found no significant difference in the incidence of major ICH, re-thrombosis, or re-embolism between GBM patients treated with DOACs and those treated with LMWH [

21]. Additionally, apixaban showed promising safety as a prophylactic agent for VTE in a small cohort of newly diagnosed patients with malignant glioma, with no treatment-related adverse events reported [

22].

Despite being one of the largest retrospective studies with 528 patients evaluated and a 21% incidence of VTE, we were unable to identify a distinct population at diagnosis of an elevated risk for thrombosis development. Consequently, our findings do not support the routine implementation of primary VTE prophylaxis. However, given the high risk of VTE during the first six months after diagnosis, primary prevention could be beneficial during this critical period. A prospective randomized trial would be appropriate to evaluate the efficacy and safety of targeted primary prevention strategies in this high-risk timeframe.

5. Conclusions

Newly diagnosed patients with GBM have been shown to have a significant risk of developing VTE. Our study is one of the largest retrospective studies assessing the risk of VTE in GBM, with 528 patients included. A previous cancer diagnosis and RP were the only factors identified as predictive of a higher risk for development thrombosis. Given their risk/benefit ratio, consideration should be given to consider primary prevention of VTE during the first six months after diagnosis with a DOAC. The benefit of preventive treatment would need to be balanced against the risk of bleeding in these patients.

Author Contributions

All authors (N.A., D.B., G.P. and H.H.) contributed to the study conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation and visualization. The first draft of the manuscript was prepared by N.A. and D.B. and N.A., D.B., G.P. and H.H. contributed to review and editing of the manuscript. H.H. provided supervision, project administration and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (Project Number:13238-C approved on April 11, 2022)

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the following justification presented to the ethics board: “We are seeking a waiver of consent for this study as we feel it is best conducted through a retrospective design. Our sample size and need for patient follow-up makes a prospective design unfeasible. We do not feel it would possible to reach every former patient for consent as many patients may have changed their contact information since their medical presentation, or may have passed away. As the data collection will be done in a way to ensure confidentiality, it is expected to have an extremely low risk of privacy breach. As such, the risk of privacy breach would appear to be outweighed by the benefits to understanding the progression of this disease and gaining more information to guide possible modifications to our current surveillance paradigm.”

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

N. Al Majarafi: No Relationships to Disclose; D. Binjabal: No Relationships to Disclose; G.R.Pond: Stock and Other Ownership Interests - Roche Canada, Honoraria – AstraZeneca, Consulting or Advisory Role - Profound Medical; Takeda; H.W. Hirte: Honoraria – Novocure, Consulting or Advisory Role - Novocure

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GBM |

Glioblastoma multiforme |

| JCC |

Juravinski Cancer Centre |

| VTE |

Venous thromboembolism |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| DVT |

Deep venous thrombosis |

| PE |

Pulmonary embolism |

| KPS |

Karnofsky Performance Status |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| RP |

Recurrence/progression |

| HR |

Hazard ratio |

| LMWH |

ow molecular weight heparin |

| DOAC |

Direct oral anti-coagulant |

| ICH |

Intra-cranial hemorrhage |

References

- Marras LC, Geerts WH, Perry JR et al. The risk of venous thromboembolism is increased throughout the course of malignant glioma: an evidence based review. Cancer 2000, 89(3),640–6.

- Gerber DE, Grossman SA, Streiff MD. Management of venous thromboembolism in patients with primary and metastatic brain tumors. J Clin Oncol 2006, 24(8),1310-8.

- Edwin NC, Khoury MN, Sohal D, et al. Recurrent venous thromboembolism in glioblastoma. Thrombosis Res 2016, 137,184–8.

- Semrad TJ, O’Donnell R, Wun T, et al. Epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in 9489 patients with malignant glioma. J Neurosurg 2007, 106(4),601–8.

- Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, Culakova E, et al. Development and validation of a predictive model for chemotherapy-associated thrombosis. Blood 2008, 111(10),4902-7.

- Brandes AA, Scelzi E, Salmistraro G et al. Incidence and risk of thromboembolism during treatment of high-grade gliomas: a prospective study. European J Cancer 1997, 33(10),1592-6.

- Burdett KB, Unruh D, Drumm M, et al. Determining venous thromboembolism risk in patients with adult-type diffuse glioma. Blood 2023, 141(11),1322–36.

- Riedl R, Ay C. Venous Thromboembolism in Brain Tumors: Risk Factors, Molecular Mechanisms, and Clinical Challenges. Semin Thromb Hemost 2019, 45(4),334–41.

- Portillo J, de la Roche IV, Font L, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with glioblastoma multiforme: Findings of the RIETE registry. Thromb Res 2015, 136(6),1195-203.

- Lim G, Ho C, Roldan UG, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in glioblastoma patients. Cureus 2018, 10(5),e2678.

- Perry JR. Thromboembolic disease in patients with high-grade glioma. Neuro-Oncol 2012, 14 (suppl_4),iv73–iv80.

- Natsumeda M, Uzuka T, Watanabe J, et al. High incidence of deep vein thrombosis in the perioperative period of neurosurgical patients. World Neurosurg 2018, 112,e103-e112.

- Jo J,Diaz M, Horbinski C, et al. Epidemiology, biology, and management of venous thromboembolism in gliomas: An interdisciplinary review. Neuro-Oncol 2023, 25(8),1381-94.

- Simanek R, Vormittag R, Hassler M, et al. Venous thromboembolism and survival in patients with high-grade glioma. Neuro-Oncol 2022, 9(2),89–95.

- Alshehri N, Cote D, Hulou MM, et al. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in brain tumor patients undergoing craniotomy: A meta-analysis. J Neurooncol 2016, 130(3),561–70.

- Perry JR, Julian JA, Laperriere, NJ, et al. PRODIGE: a randomized placebo-controlled trial of dalteparin low-molecular-weight heparin thromboprophylaxis in patients with newly diagnosed malignant glioma. J Thromb Haemost 2010, 8(9),1959–65.

- Carrier M, Abour-Nassar K, Mallick R, et al. Apixaban to Prevent Venous Thromboembolism in Patients with Cancer. N Engl J Med 2019, 380(8),711-9.

- Raskob GE, van Es N, Verhamme P, et al. Edoxaban for the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2018, 378(7),615-24.

- Young AM, Marshall A, Thirwell J, et al. Comparison of an oral factor Xa inhibitor with low molecular weight heparin in patients with cancer with venous thromboembolism: Results of a randomized trial (SELECT-D). J Clin Oncol 2018, 36(20),2017-23.

- Khorana AA, McNamara MG, Kakkar AK, et al. Assessing full benefit of rivaroxaban prophylaxis in high-risk ambulatory patients with cancer: Thromboembolic events in the randomized CASSINI Trial. TH Open 2020, 4(2),e107–e112.

- Dubinski D, Won S-Y, Voss M, et al. Direct oral anticoagulants versus low-molecular-weight heparin for pulmonary embolism in patients with glioblastoma. Neurosurg Rev 2022, 45(1),451–7.

- Thomas AA, Wright H, Chan K, et al. Safety of apixaban for venous thromboembolic primary prophylaxis in patients with newly diagnosed malignant glioma. Journal of Thromb Thrombolysis 2022, 53(2),479–84.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).