1. Introduction

Refrigeration plays a vital role in various applications, including the preservation of perishable food products and the control of cooling temperatures in electronic systems [

1]. Conventional domestic refrigerators typically utilize vapor-compression technology. While this technology presents a high coefficient of performance (COP), the refrigerants used in these systems can have adverse environmental effects. In contrast, thermoelectric refrigeration, which is based on the Peltier effect, offers significant advantages over traditional vapor compression technology, even though its COP is not as high [

2,

3]. These benefits include the elimination of refrigerants, a more compact system design, reduced noise and vibration, enhanced temperature control through the variation of their power supply, and minimal maintenance requirements. Moreover, thermoelectric systems can be conveniently powered by direct current (DC) sources, such as photovoltaic cells [

4].

Thermoelectric cooling (TEC) technology is gaining popularity for use in small and portable refrigeration systems, particularly in scientific laboratories where a constant temperature bath is necessary [

5]. This technology effectively cools and maintains the temperature of samples at a specific set point. Thermoelectric cooling devices have found interesting applications in the medical field, serving as the cooling element in the cryoprobes used for cryosurgery, as well as being used for cooling the brain or skin [

6]. Additionally, they are employed in cryotherapy systems where precise control of skin blood flow is required [

7].

The heat generated by a thermoelectric module must be extracted from the cooled environment and expelled to the external surroundings. Achieving the necessary level of heat dissipation requires radiator types with sufficient heat transfer capacity. This process is typically facilitated by forced air cooling with pin–fin heat sinks [

8,

9]. To decrease the thermal resistance of the hot-side heat sink, specific types of heat exchangers, such as heat sinks with phase change materials [

10] and heat pipe cooling [

11] or those using nanofluid liquid cooling [

12] have been employed, offering, in some applications, a very low thermal resistance of 0.02 °C/W. Those heat sink cooling devices proved to increase (by more than 10%) the overall coefficient of performance values of refrigeration systems. This improvement is achieved at higher system costs, accompanied by increased energy consumption.

When selecting an air conditioning system based on thermoelectric devices for a particular application, it is important to evaluate not only the TEC coefficient of performance and the required cooling capacity at the desired temperature. We must take into consideration also the operational characteristics of the cooling system and overall energy consumption, with various types of losses associated with the thermodynamic process of heat transfer at the cold and hot side of TEC. Jurkans and Blums [

13] investigated a practical method to increase the efficiency of thermoelectric cooling. They experimentally validated a simple model that evaluated the induced heat loss and the recovered energy after a dynamic switch of the thermoelectric module between cooling and electrical energy generation modes.

From a thermodynamic point of view, the second law analysis and Entropy Generation Minimization (EGM) method has proved to be very powerful tools in the optimization of TEC systems, with the evaluation of the minimum system irreversibility and maximum exergy contribution at a constant environmental temperature [

14,

15,

16]. Tipsaenporm et al. [

17] analyzed the thermodynamic properties of a compact thermoelectric air conditioner using an exergy analysis approach. They found that the exergy efficiency of the cooling system was relatively low compared to its coefficient of performance. Many TEC-based cooling system studies have been focused on maximising cooling capacity and coefficient of performance for the overall refrigeration system, improving exergy efficiency as the temperature difference between the TEC hot and cold side’s increases. The optimal performance of a single-stage TEC can be achieved by adjusting both the operating current and the TEC's configuration [

18].

The practical purpose of this refrigeration box is to serve as a cooling medium, providing a viable and cost-effective alternative to the expensive thermostatic water bath. We propose enabling the efficient extraction of phenolic compounds from hydroalcoholic mixtures of various fruits and leaves at optimal temperatures of approximately 10°C using the ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) method [

19,

20,

21]. We will modify the upper section of the refrigerated box to accommodate the insertion of an ultrasonic transducer, which will be in direct contact with the liquid sample contained in a 100 ml glass placed inside the box. For the current refrigeration test with a water load, we aim for a liquid cooling point of 12°C inside the refrigeration box.

2. Thermal Analysis of the Heat Sink

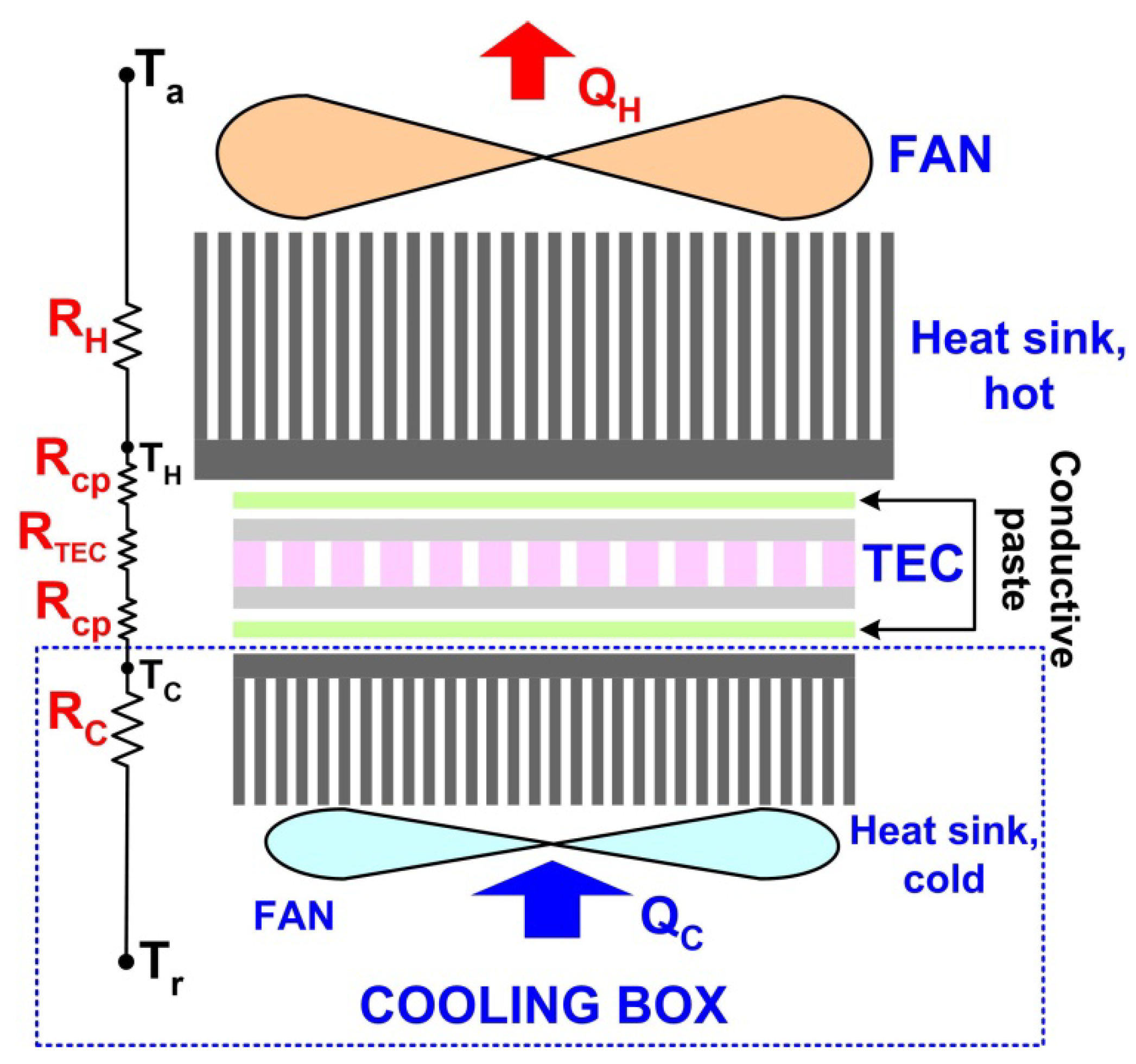

It was considered here the heat transfer by forced air convection through a system of N parallel plates (having a specific thermal conductivity) placed on a horizontal plate in contact with the heat source, having the geometric characteristics shown in

Figure 1.a. The horizontal base plate is considered to be relatively thick compared to the vertical fins and characterized by a high thermal conductivity, so that the plate is treated as isothermal. The bottom surface and edges of the horizontal plate will be considered adiabatic.

The air flux flowing through the channels formed by the fins is considered as uniform, with a constant velocity Ua, without any "leakage" outside the channel edges. The analytical model of the heat sink is based on (N – 1) parallel plate channels, with a single channel defined as seen in

Figure 1.b. Here, the air flux having an inlet velocity Ua , at specific ambient temperature Ta , will flow under forced convection through the channel of wall temperature Tw.

The fluid flow field is considered to be two-dimensional for

b << H. For a uniform temperature

Ts of the base plate (having the thickness

Ht – H), we impose a boundary condition

Tw = Ts for each of the channel walls. Next, we will use the fin dimensions and thermal conductivity to evaluate the rate of heat transfer from this ideal channel (presented in

Figure 1.b), estimating afterwards the actual heat transfer rate of heat sink.

Thermo-physical air properties were evaluated at the

film temperature [

22]:

We define the Reynolds number by considering the channel width

b as the characteristic length [

22]:

were νa (m2/s) represents the air kinematic viscosity.

If we know the volumetric flow rate of air

Va (m

3/s) circulated by a fan through the heat sink fins, we can calculate the average velocity of air flux with the following expression [

23]:

The channel dimensions will be correlated with the Re number defined by relation (2) to express the

Re number for each channel [

22]:

The goal of developing heat sink configurations with

H >> b is to maximize the available fin surface area, a goal that is often achieved by compromising the fin efficiency. When

H >> b, the temperature difference between the fins and the horizontal plate increases due to the increase of the heat conduction resistance, and the performance of the radiator will decrease. During the air forced convection, the heat is removed faster from the fins, comparing with the amount of heat removed from the horizontal plate of the radiator. From this reason, it was considered here a composite solution based on the limit cases of fully developed or under developing air flow between isothermal parallel plates [

22].

An ideal value of the average heat transfer coefficient

hi (W/m2K) will be associated with an ideal Nusselt number value

Nui and with the air thermal conductivity

ka (W/mK) through the relation [

22]:

In expression (6),

Pr represents the Prandl number, calculated with relation:

were

μa (Kg/m∙s) and

Cp,a ( J/KgK) are dynamic viscosity and specific heat of air.

Under this composite model of air forced convection through parallel plates of the heat sink, the fin efficiency can be expressed as [

22]:

were

ks (W/mK) is the fin thermal conductivity, with a value of 220 W/mK for the Aluminium Alloy EN AW-6060 [

22].

We can see in relation (8) that the decrease of the ratio H/b (or H/t) would reduce the thermal resistance through the fins, and η can approach the ideal value of 1.

The real value of the Nusselt number will be defined as [

22]:

According to the composite model, the

real heat transfer coefficient for air under forced convection is calculated as [

22]:

The total heat dissipation rate of the heat sink, denoted as

QHS (W), is determined under the assumption of uniform heat transfer coefficients for both the base plate and the fins, in accordance with the relation provided in [

24]:

with

ΔTsa = Ts - Ta as the surface-to-air temperature gradient.

In relation (11),

M and

N are dimensionless parameters, defined through specific expressions:

The surface area of the base plate is given by

Ab = W∙L, while the perimeter and cross-sectional area of the heat sink fins,

P (m) and

Ac (m

2), respectively, are calculated with relations:

4. Performance Analysis of the Thermoelectric Cooling Unit

The main purpose of this air – cooled thermoelectric refrigeration investigation is to establish the cooling performance of the system with an optimal TEC module in the presence of a cooling load. For this purpose, a 100 ml Berzelius glass was placed inside the cooling box.

The coefficient of performance for the entire refrigeration system was calculated with expression [

35]:

were

We is the total electrical power consumed by the cooling system, and

QT (W) represents the refrigeration load (total heat rate developed inside the cooling box), evaluated with relation [

35]:

In the relation above, Qcb (W) is the heat flux through the cooling box, Qpl (W) is the product load as the heat removed by the water glass in the refrigerator and Wfan (W) is the electrical power consumption of the external and internal system fans.

The product load and heat flow inside the cooling box are calculated as [

35]:

In relation (35), m (g) is the mass of the water product, Cp (J/g∙K) is the specific heat capacity of water product, Tp,i and Tp,f (K) are initial and final temperatures of the water product, respectively, and Δt (s) is time interval for the water cooling from Tp,i to Tp,f .

In expression (36),

A (m

2) is the internal surface area of the cooling box and

U (W/m

2K) is the

overall heat transfer coefficient, defined as [

35]:

with the wall thickness and thermal conductivity of the polystyrene – based cooling box,

dcb = 4cm and

kcb = 0.035 W/mK, respectively.

The heat transfer coefficient at the inner and outer surface of the refrigeration system,

hint and

hout, respectively, are calculated based on relations (5) – (10), with the geometrical parameters for the external and internal heat sinks presented in

Table 2.

All the heat sink dimensions were measured using a digital caliper with resolution of 0.01 mm and accuracy of 0.03 mm.

In

Table 1,

N is the number of fins,

W is the sink base width,

L is the sink base length,

t is the fin thickness,

b is the distance between fins,

Ht is the heat sink height and

H is the fin height (see

Figure 1).

5. Experimental Set-Up

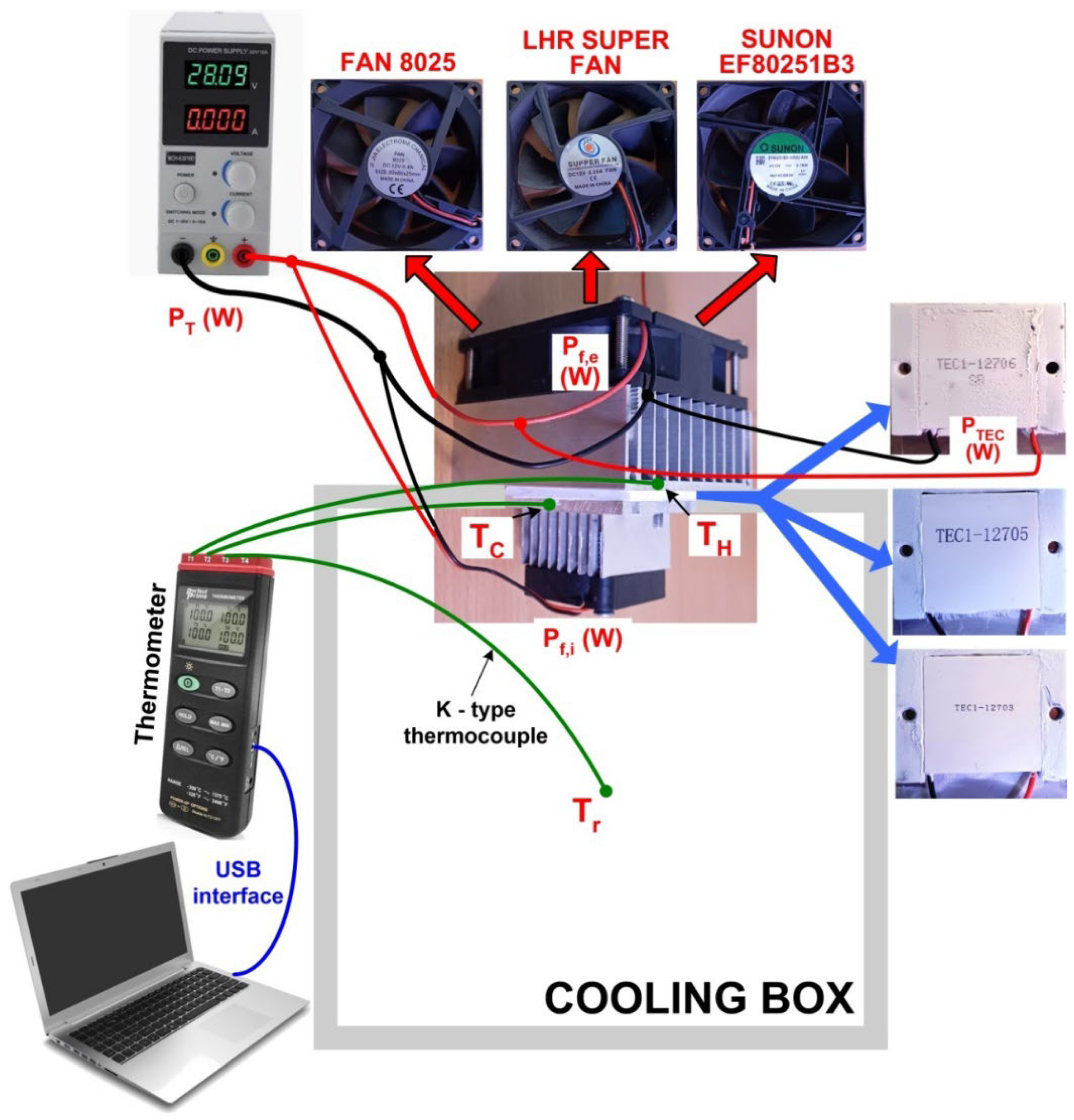

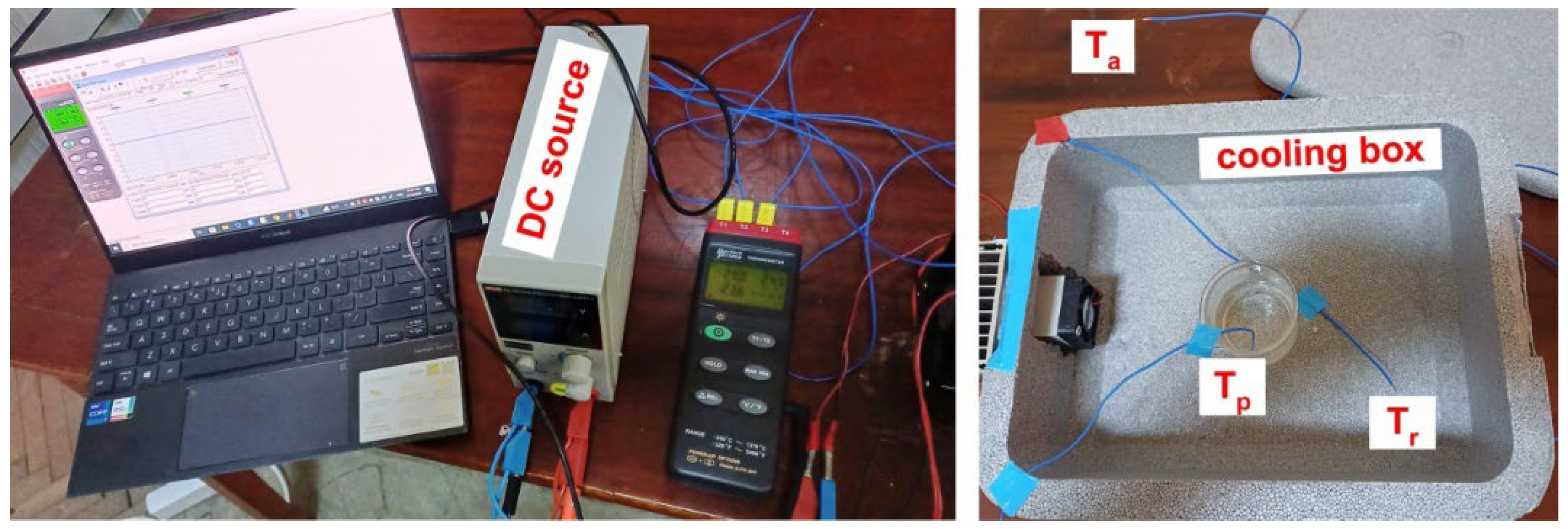

Two different configurations of thermoelectric cooling systems were considered here. The first one, presented in

Figure 3, contained the cooling box with air load and was used for the performance evaluation of three different cooling fans (placed on the external heat sink) and also of three different thermoelectric cooling modules. For the second configuration, presented in

Figure 4, we considered a water glass of 100 ml as a cooling load for the refrigeration box.

We used here a server station cooling FAN 8025 DC 12V – 0.4 A (Jin Li Jia Electromechanical, China) with a rotation frequency of 4200 revolutions per minute (RPM) and a circulated air flow volume of 53 cubic feet per minute (CFM), one LHR SUPPER FAN DC 12V – 0.218 A (Shenzen Linghairui Technology, China) having 3000 RPM and 41.2 CFM and a EF80251B3-1000U-A99 12V – 0.78W cooler (Sunon,Taiwan), having 2600 RPM and 33 CFM. The cooling air inside the box was circulated by a small DC brushless fan (Dongguan HYJ, China) 12V-0.1A, with 6200 RPM and 6.86 CFM, placed on the internal heat sink.

As we can see in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, experimental cooling system contains a cooler box made from expanded polystyrene, with the inner dimensions of 26 x 20 x 9.5 cm and the wall thickness of 4 cm. Temperatures at the surface of TEC hot plate

TH, TEC cold plate

TC, refrigerated air inside the box

Tr, ambient temperature

Ta and water load inside the glass

Tp were measured using a four - channel PerfectPrime TC0304 digital thermometer (resolution of 0.1

oC and accuracy of ± 1

oC), with K-type thermocouples as temperature sensors. The power supply for the TEC module, external and internal fans,

PTEC,

Pf,e and

Pf,i, respectively, was provided by a 300W MCH – K310D DC source (± 0.5% voltage/current display accuracy). Two Kafuter K – 523 thin films of thermally conductive paste with a thermal conductivity of 1.2 W/mK, placed between the hot/cold plate of TEC module and external/internal heat sinks, offered a maximization of heat transfer between the metallic/ceramic surfaces.

Experimental temperature data were recorded through a USB connection between the thermometer and PC using the TestLink TC0309 software.

We tested thermoelectric coolers type TEC1 – 12703, TEC1 – 12705 and TEC1 – 12706, based on 127 bismuth telluride (Bi

2Te

3) semiconductor couples (

n - type and

p – type), with similar dimensions

LxWxH (mm) : 40 x 40 x 3.8 (

0.1) mm, characterized by different thermo - electrical parameters (see

Table 1). In the datasheets, the maximum values of the voltage, DC current and cooling capacity,

Umax,

Imax and

Qc,max, respectively, are specified for a maximum temperature gradient

ΔTmax = 70

oC, at a hot side temperature

Th0 = 27

oC.

Table 3.

Specifications of the thermoelectric modules TEC used in this study [

28,

29,

30].

Table 3.

Specifications of the thermoelectric modules TEC used in this study [

28,

29,

30].

| TEC model |

Umax (V) |

Imax (A) |

Qc,max (W) |

| TEC1 - 12703 |

15.8 |

4 |

39.8 |

| TEC1 - 12705 |

16 |

5.4 |

54.1 |

| TEC1 - 12706 |

16 |

6.1 |

61.4 |

6. Results and Discussions

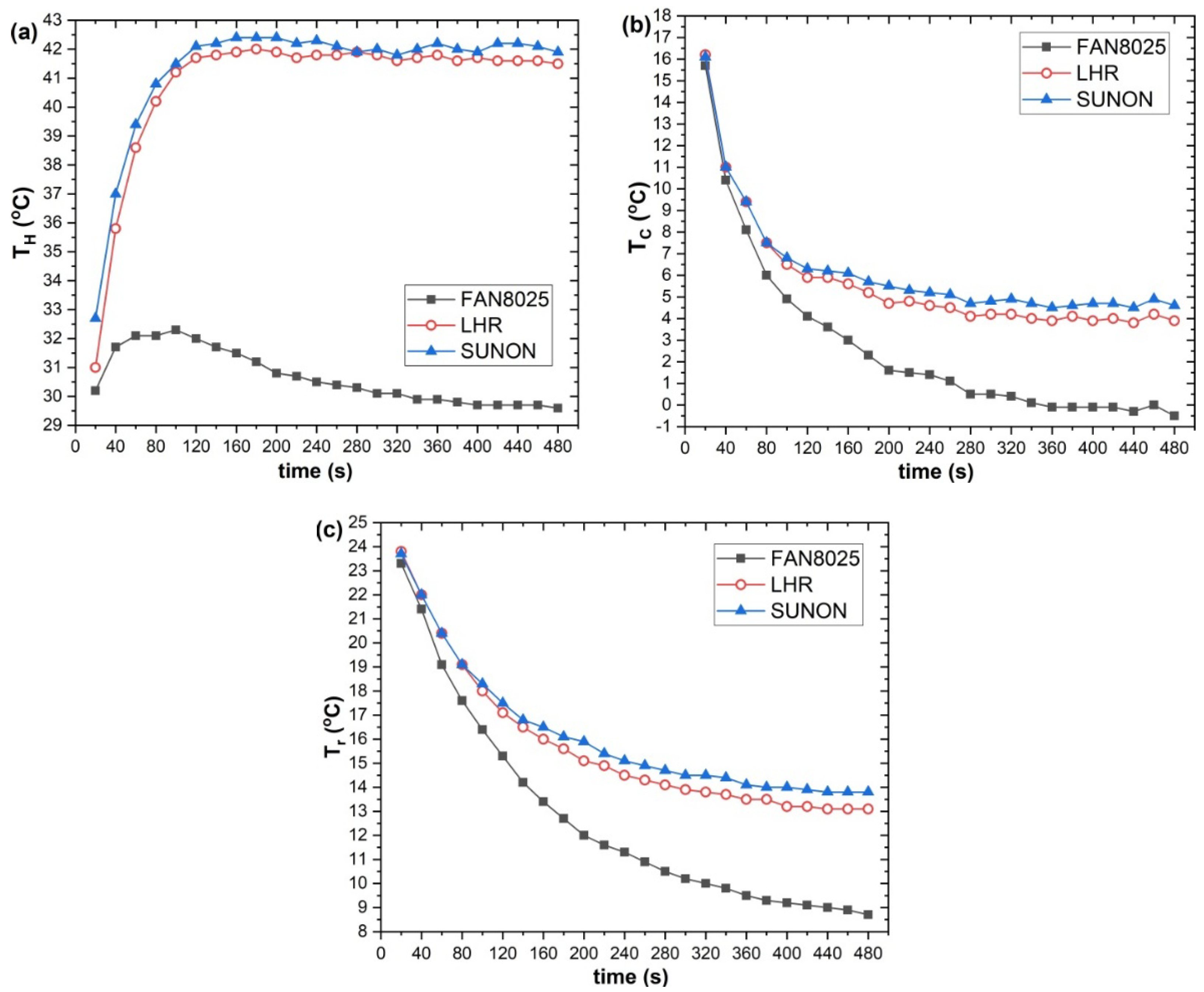

In the first part of this study, we conducted cooling tests of 8 minutes duration using a commonly used TEC module for commercial freezing boxes, TEC1 -12706 and three different fans for air ventilation of the external heat sink. During all the investigations presented here, DC power supply of the entire refrigeration system was set to a voltage of 12 V.

The average electrical power consumption (Pf,e) for the three external cooling fans: FAN 8025, LHR, and SUNON was measured at 4.56 W, 2.59 W, and 0.85 W, respectively. For the internal fan, the average power consumption was Pf,i = 0.661 W.

Table 4 below presents the mean values (± standard deviation) for the main thermo-hydraulic parameters evaluated during the tests of the external heat sink under various forced air convection conditions.

Increasing the Reynolds number Re inside the turbulent flow regime (at values over 4000) will reduce the junction temperature between the heat sink and the TEC module. This way, we can improve the heat transfer rate by reducing the thermal resistance at the heat sink/TEC interface. From

Table 3, we can see that the mean Re value registered during the SUNON cooler testing was close to the lower limit of the turbulent flow region. Therefore, this type of cooler is not a good choice for the present refrigeration application.

The Nusselt number (

Nu) quantifies the convective to conductive heat transfer ratio. So, the highest

Nu value registered in the case of FAN 8025 cooler testing indicates the most decisive influence of convective mechanisms within the heat exchange process. A higher Reynolds number is one of the primary factors contributing to an increase in

Nu, which intensifies the convective heat transfer between the airflow and the heat sink [

36].

We measured the cooling system temperatures

TH,

TC, and

Tr during three different tests of 8 minutes duration at an average external air temperature

Ta of 24

oC. The results are presented in

Figure 5. In the case of FAN 8025 cooler testing, for the last measurement point, the TEC hot side temperatures

TH decreased by about 40 %, along with a decrease of refrigerated air temperature

Tr by over 33 % by comparing with LHR cooler testing. Consequently, the heat transfer coefficient

hb was about 12 % higher (see

Table 4).

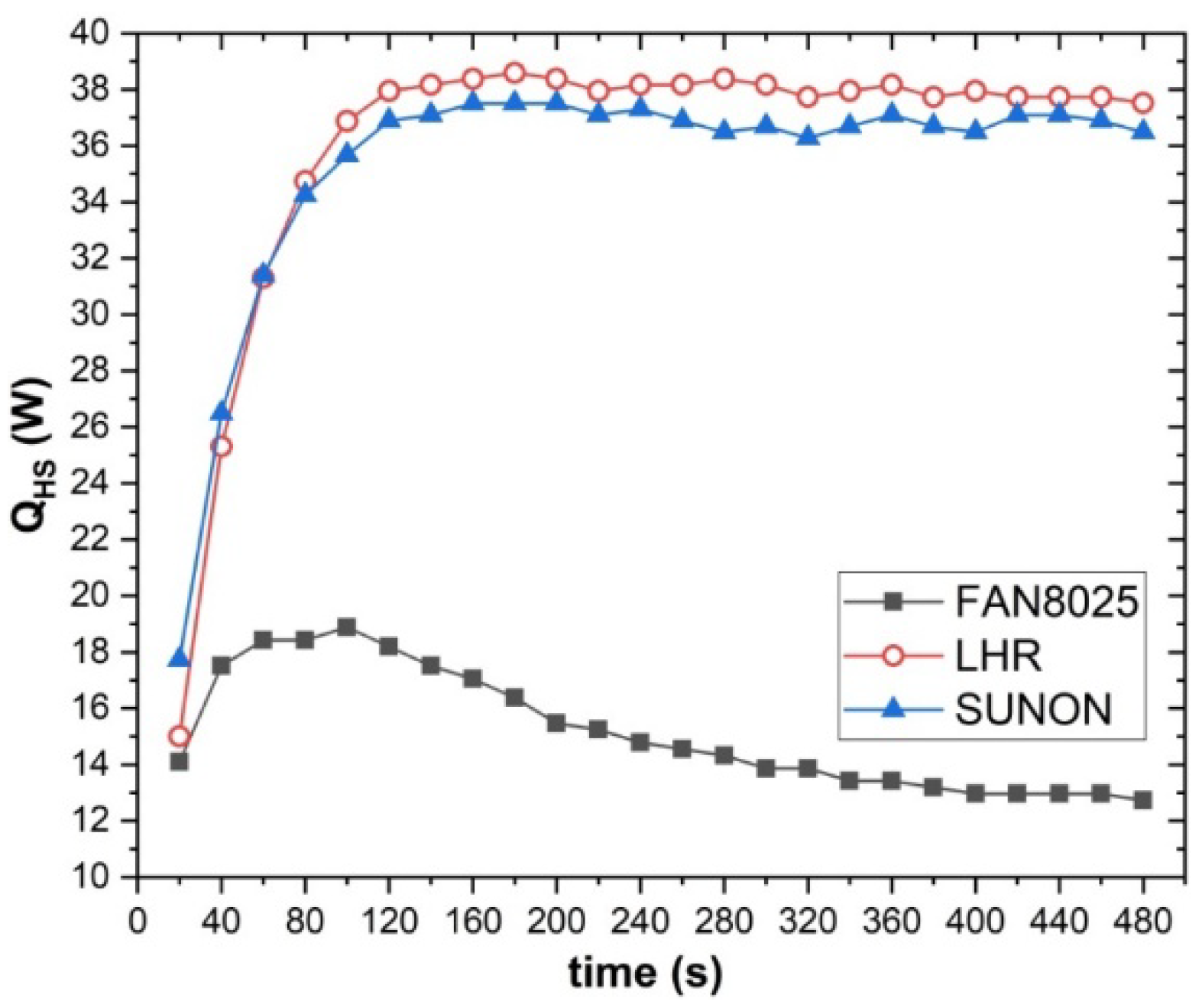

In

Figure 6, we present the variations in the heat dissipation rate of the external heat sink equipped with the different cooling fans. Under similar surface-to-air temperature gradients,

ΔTsa = TH - Ta, recorded during the LHR and SUNON tests (see

Figure 5), the heat sink using the LHR cooler showed the highest Q

HS values. This behavior can be attributed to slightly increased heat transfer coefficients

(hb values), as detailed in

Table 4. Conversely, the heat sink test with FAN 8025, which had the highest

hb values but much lower

ΔTsa values, resulted in the lowest

QHS values, offering the most efficient air cooling inside the refrigeration system.

In the second stage of the study, we investigated the cooling performances of three different commercial TEC devices inside the same cooling box with an air load and an optimal air ventilator for the external heat sink (FAN 8025 cooler). The average electrical power consumption (PTEC) of the three thermoelectric module modules, TEC1 - 2703, TEC1 - 12705 and TEC1 - 12706, indicated by the power supply at the beginning of each test was 28.18 W, 34.65 W and 53.19 W, respectively.

Figure 7 presents the variations in time for the hot side – cold side temperature gradient of the TEC modules,

ΔTHC = TH – TC. We could observe a slight increase with about 1

oC of

ΔTHC in the case of TEC1- 12705 testing by comparing it with TEC1- 12706 testing during the last 3 minutes.

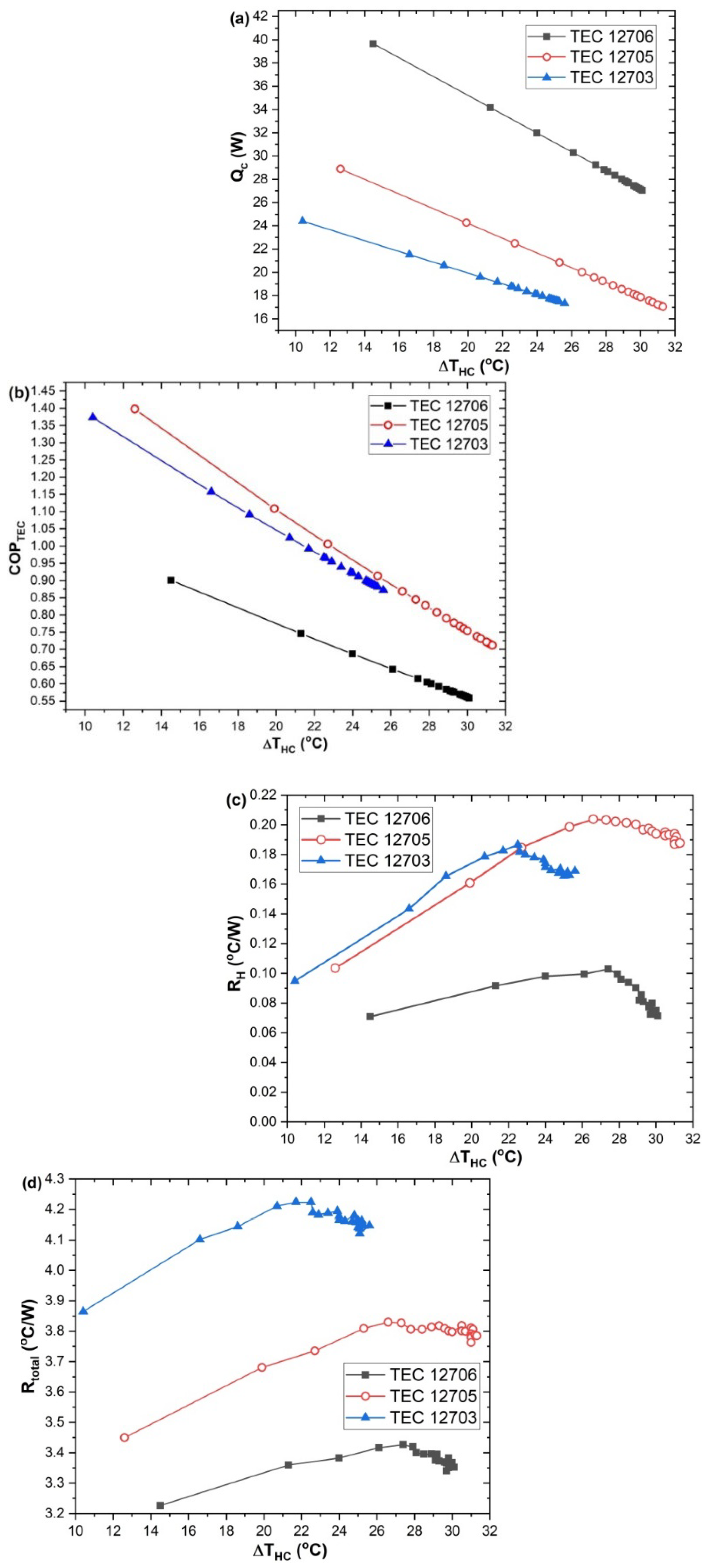

Figure 8 shows the cooling performance of the TEC1 - 12706, TEC1 - 12705 and TEC1 - 12703 modules and also the variation of the thermal resistances inside the refrigeration system at different temperature gradients between the hot and cold side of thermoelectric modules.

Under a much higher current absorbed from the power supply

It, TEC1 - 12706 offered an enhanced cooling capacity for the refrigeration system compared with TEC1 - 12705, presenting this way

QC values about 10 W higher (see

Figure 8.a). Instead, the increased Joule power losses registered for TEC1 - 12706 generated a power consumption with about 24 W higher than for TEC1 - 12705, so his corresponding COP cooling parameter decreased with 27 % after 8 minutes of testing. Although TEC1 - 12703 presented the lowest cooling capacity, this module showed also the lowest power losses through Joule effect and the COP values were closer to the TEC1 - 12705 module (see

Figure 8.b).

Chang Y. W. et al. [

37] showed that a thermoelectric air-cooling module presents a lower performance compared to a conventional heat sink without a TEC when the thermal resistance of the heat sink exceeds 0.385

oC/W.

Figure 8.c revealed a proper performance of the heat sink under forced air convection, coupled with all the three TEC modules. Due to the high amount of heat transferred between the TEC1-12706 hot side and the heat sink, the R

H value was the lowest for this system configuration. For example, at

ΔTHC = 30°C, R

H was only 0.072 °C/W.

As we can see in

Figure 8.d, the total thermal resistance of the cooling system with TEC1 - 12706 presented the lowest values, under a lowest individual thermal resistance

RTEC and also the lowest heat sink thermal resistances at the hot and cold junction of TEC module.

The coefficient of performance (COP) of a complete cooling system, which includes both heat supply and heat dissipation subsystems, is influenced by temperature drop losses across the system thermal resistances [

38]. Consequently, the COP of the entire thermoelectric cooling unit should be lower than that of an individual TEC module operating under the same

ΔTHC conditions.

Under those circumstances, the exergy analysis became necessary to take into account all the losses and inefficiencies registered during the energy conversion process developed inside the refrigeration system.

The total entropy generation rate

Sgen inside the cooling system is directly correlated with the internal and external irreversibilities. Internal irreversibilities arise from Joule heating losses due to electrical resistance and heat conduction losses within the thermoelectric couples. External irreversibilities result from irreversible heat transfer between the TEC and the heat source's hot junction and between the TEC cold junction and the heat sink reservoirs [

39].

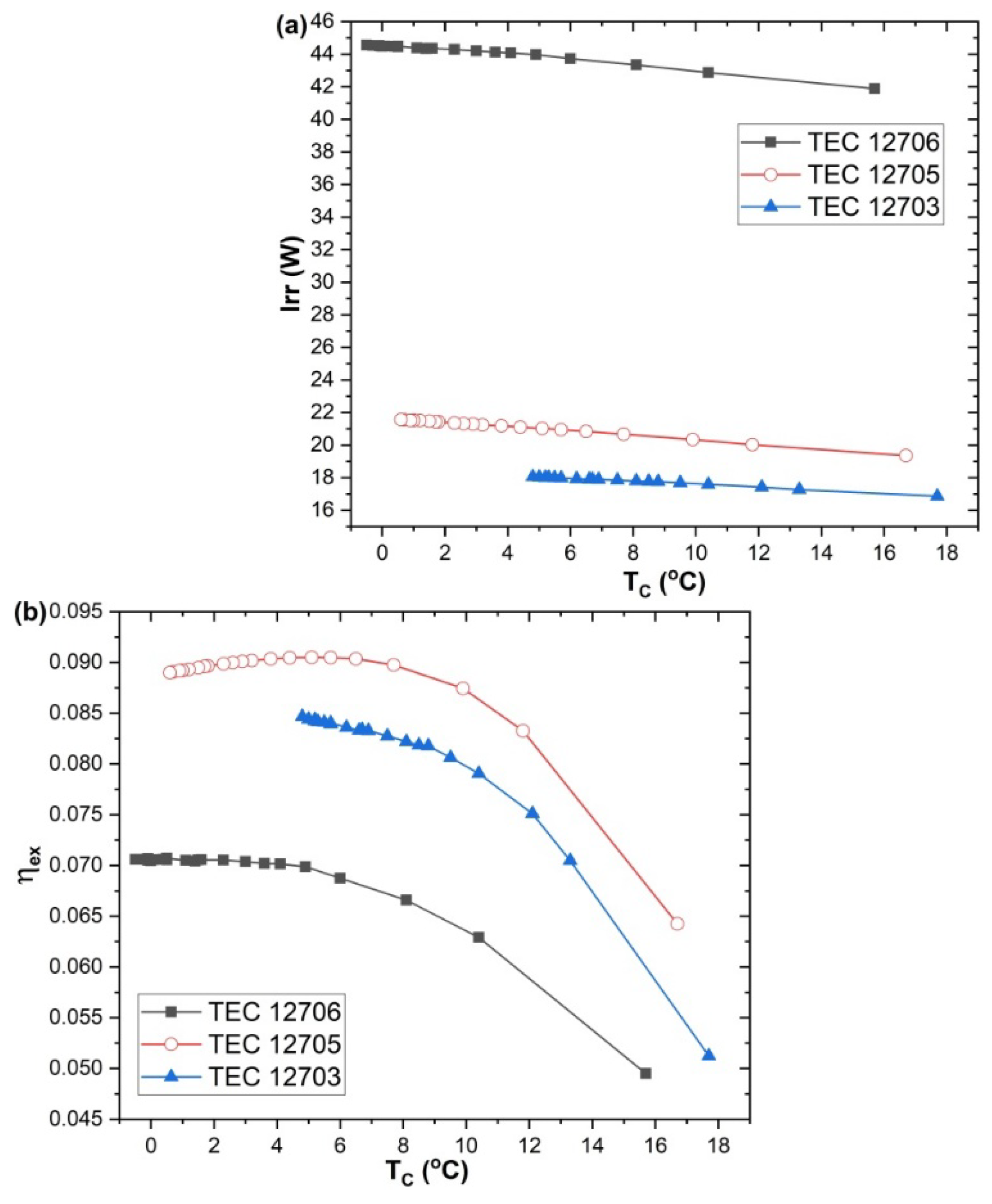

The required refrigeration temperature and a specific cooling capacity play crucial roles in determining the practical applications of thermoelectric cooling systems. Therefore, we present in

Figure 9 the variations in the thermoelectric module's exergy efficiency (

ηex) and irreversibility (

Irr) measured at different cooling temperatures throughout the entire testing period.

During the air cooling test, TEC1- 12705 and TEC1 - 12706 exhibited similar values for

TC and

TH. However, the

QC value recorded for TEC 12706 was significantly higher, with the

QH value being 71% to 86% greater. As a result, the entropy generation rate (

Sgen) during the testing of TEC1 - 12706 was 0.076 W/K higher than that of TEC1 - 12705. Consequently, as illustrated in

Figure 9.a, the irreversibility rate for TEC1 - 12706 was twice as high as that for TEC1 - 12705.

Equation (32) shows that a key factor affecting the exergy efficiency coefficient is the ratio of cooling efficiency to the power consumption of the TEC module. During testing, we found that the Qc/Pt ratios for TEC1 - 12706, TEC1 - 12705, and TEC1 - 12703 were 0.71, 0.91, and 0.92, respectively. Consequently, the exergy efficiency of TEC 12705 was approximately 7.3% higher than that of TEC1 - 12706 at a temperature TC = 5°C.

Tipsaenporm et al. [

17] investigated a compact thermoelectric–based refrigeration system containing three TEC1–12708 modules and a rectangular fin heat sink under forced convection cooling. They observed a similar behaviour of system irreversibility, with a linear increase in value from approximately 38 W at an electric current supply of 2 A to 55 W at a current of 3 A. The maximum exergy efficiency achieved by their cooling system was 0.088 at Q

C = 28.6 W, which is almost identical to the values presented by TEC1-12705 during the cooling test with an air load at T

C values of 8–10 °C.

X. Li et al. [

40] reported also a similar range of exergy values for a thermoelectric cooler module type TEC1 – 12708 powered by a 12V supply voltage within a TEC–TEG system.

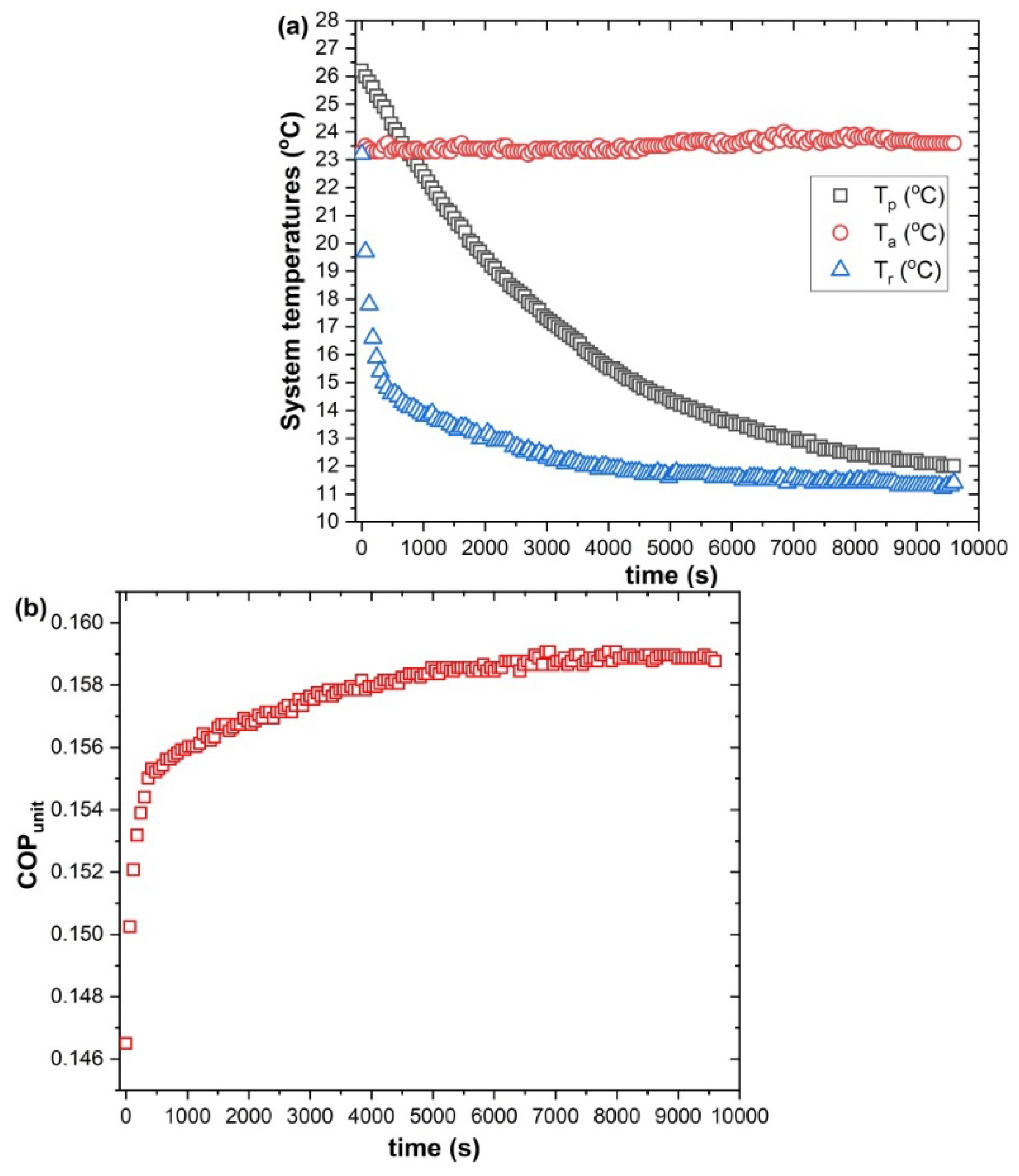

In the last part of this study, a water glass of 100 ml was considered as a cooling load for the refrigeration box. We could evaluated this way the coefficient of performance of the overall refrigeration system, containing the TEC module and external ventilation fan with optimal cooling behavior.

In

Figure 10.a, we present the temperature variations of ambient air, refrigerated air, and water load inside the refrigeration box during a 160-minute cooling test. After 3000 seconds of testing, we observed a rapid decrease in the internal refrigeration temperature (

Tr) to 12.3 °C, corresponding to a water load temperature (

Tp) of 17.3 °C. This behaviour indicates that the internal pin-fin heat sink effectively cools the air.

Min and Rowe [

41] defined the

cooling-down period (CDP) of a refrigerator as the time required for the refrigeration temperature to drop from the surrounding ambient temperature (

Ta) to a value that is 20% above the system's designated cooling set point. We set the cooling point at 12 °C for our current refrigerator configuration. As shown in

Figure 10. a, the CDP value was 660 seconds, consistent with the expected duration for the small refrigeration volume of the cooling box (0.00494 m³).

Figure 10b shows that after only 6 minutes of testing, the refrigeration unit's COP attained a value of 0.155 and remained almost constant (2.5% maximum deviation) throughout the remaining testing time.

M. Miramanto et al. [

42] investigated also a thermoelectric cooling system formed by TEC1 – 12706 module (P

TEC =38.08 W), a polyurethane cooler box with dimensions of 21.5 cm x 17.5 cm x 13 cm, an external heat sink - fan and inner heat sink, using a 380 ml bottle of water as the cooling load. Without an internal fan for the cooling air circulation, they reported a temperature gradient between the outer and inner cooler box

ΔTar = Ta – Tr of only 6

oC after 10.000 s of testing, half the value registered in our case under the same testing conditions. Using an identical cooler box, a TEC 1 – 12710 working at

PTEC = 42W, a fan – based inner heat sink with a vapor chamber plate for the cooling of external heat sink and 500 ml of water as the cooling load, A. Winarta et al. [

43] reported an improved cooling of the water load from 26

oC to 9

oC after 200 minutes of testing for a thermoelectric refrigeration system with vapor chamber heat sink.

Gökçek and Şahin [

35] performed an experimental test of a thermoelectric refrigerator box with a water cooling system for the external heat sinks and a TEC1 – 12709 module working at P

TEC = 60W. They reported a COP value of 0.23 after 25 minutes of testing, but after only 50 minutes of operation, the COP decreased to 0.13.