1. Introduction

The growth of cities results in various processes of landscape alteration, including physical changes and associated ecosystems. The most influential factors in the physical environment are related to hydrological behavior and soil loss. These factors directly impact the environmental services that can be generated, such as the maintenance of habitats linked to local fauna and flora.

These factors have become common in Amazonian cities over the years. Urbanization along riverbanks has led to the modification of floodplains and the imposition of an impermeable environment marked by the intense removal of vegetation cover [

1,

2]. The direct consequence is observed in both surface and groundwater recharge areas, as well as in their quality patterns, in addition to the advancement of erosive processes characterized by the presence of collapse areas and mass movements [

3]. The landscape conditions that favor this behavior are related to the low marginal slopes of rivers, which promote the emergence of broad floodplains, strong connectivity between surface and groundwater, and thick soil cover resulting from weathering processes [

4].

Historically, this development has consolidated, forming a belt of marginal cities along the rivers of the Amazon River delta-estuary (ADE). Their relationship with climatic seasonality and the consequent variation in water behavior (flow and level) is not harmonious, as problems related to floods and inundations, or the effects of droughts, are reported annually. Several occurrences have been reported only in the last two decades [

5]. Flood extremes marked the years 2009, 2012–2015, 2017, 2019, and 2021–2022, with peaks in 2009, 2012, 2021, and 2022; and minimums in 2010 and 2023 [

6,

7]. The chronology reveals a very high proximity between extremes, highlighting the need to expand studies on future scenarios associated with climate change and existing social and economic vulnerabilities.

The succession of hazardous events demonstrates that risk management is an essential tool for identifying the extent of the affected area, assessing forms of reduction, mitigation, and prevention, aiming to minimize the vulnerability or exposure of the affected population. In the case of mass movements or landslides, using geotechnologies through the configuration of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and coupled statistical methods helps cover large areas and better structure actions for intervention in the affected region [

8,

9].

The strongest barrier in assessing vulnerabilities is the degree of consolidation of the cities, with an urbanization context that varies from the central region to the periphery, marked by a heterogeneous housing pattern but with numerous residents. The cities of the ADE date back to the 17th and 18th centuries [

10], and underwent an urban consolidation process that did not prioritize a sustainable relationship with the waters, with the predominance of landfills and channeling practices, as well as the intense removal of marginal vegetation cover. These activities contributed to the elimination of the floodplain. The first cities founded were Belém, Gurupá, Cametá, Vigia, and Salvaterra, totaling nine cities in the ADE between 1700 and 1800, with the emergence of Ponta de Pedras, Barcarena, Santana, and Oeiras do Pará [

10]. The location prioritized strategic points aimed at promoting defense, trade, state representation, and religious centers [

11]. Thus, problems during flood seasons and the emergence of erosive processes became elements of adaptation for these populations, as environmental issues were not a priority at the time of the cities’ founding and growth.

The growth of the Metropolitan Region of Belém (MRB) went through several phases of expansion until reaching its current configuration. Initially formed by the municipalities of Belém, Ananindeua, Marituba, Benevides, and Santa Bárbara do Pará (1995), it was later expanded with the inclusion of Santa Isabel do Pará (2010), Castanhal (2011), and finally Barcarena in 2023 [

12]. The environmental relationship of this urban expansion demonstrates a reduction in the representation of forested areas and rivers, indicating that these environments are perceived primarily as resource sources rather than being valued for their functional significance or the provision of environmental services [

12].

The cities within the ADE have become vulnerable as they expand into the marginal areas along rivers. This problem becomes more pronounced as the degree of exposure increases. The imposition on the floodplain site has created a variety of urban contexts built either on land or over water, with extensive areas developed according to the typology of human settlements known as “

baixada” (lowland areas) translated as precarious urban settlements or social housing [

13]. This scenario reinforces the need for improved governance and a deeper understanding of the natural processes involved. It is also essential to implement appropriate mitigation actions to protect populations at risk; and the monitoring of the environmental risk conditioning processes evaluated [

14].

In this context, the ADE is framed as the object of investigation, represented by the coastal strip adjacent to the estuary, where an extensive floodplain area is vulnerable to erosive processes and has a high degree of exposure to soil collapse. The proposed objective is to investigate the processes associated with the occurrence of mass movements and their relationship with the behavior of the wetland strip in the region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Structure and Scope of Study

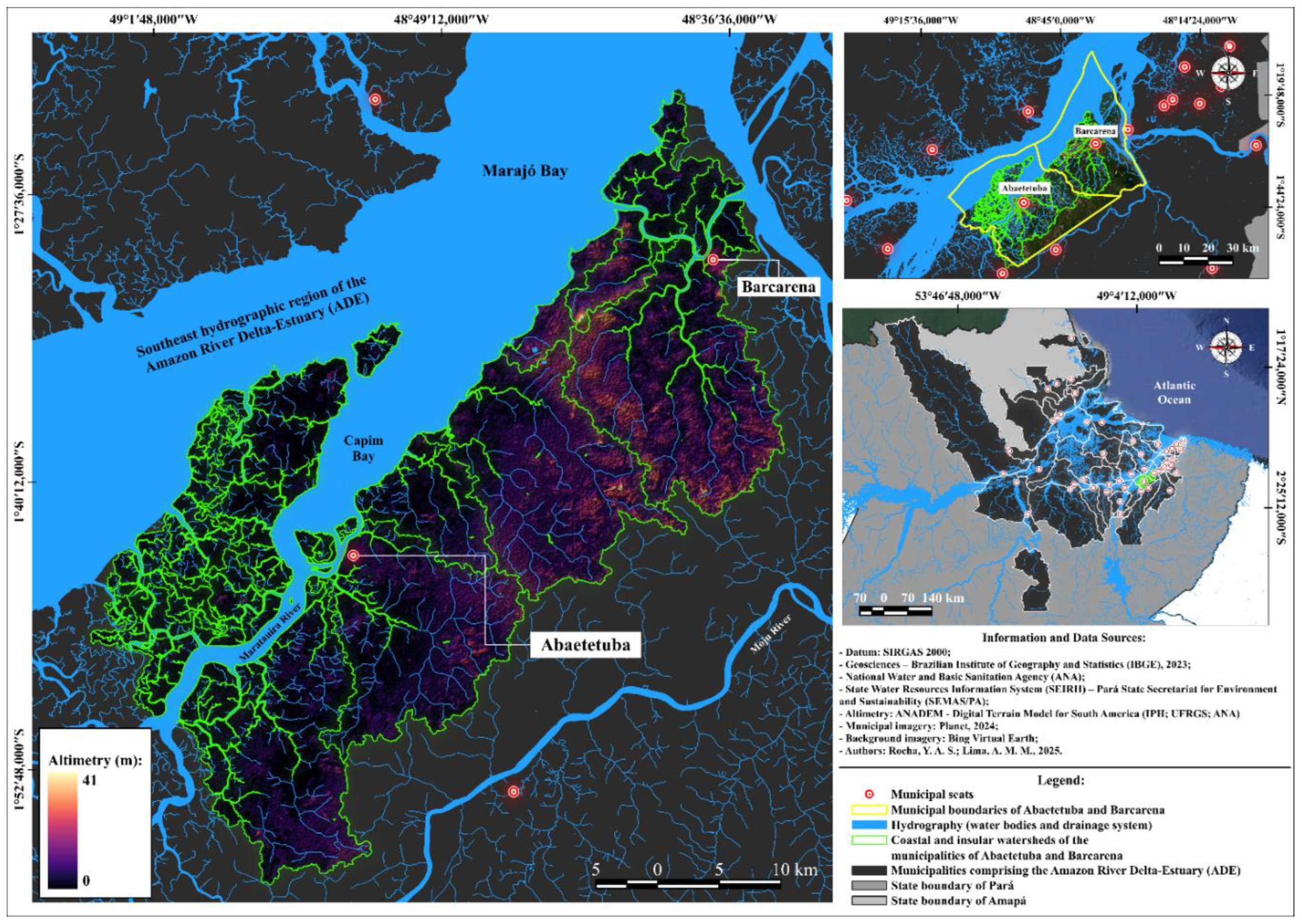

The Amazon River delta-estuary (ADE) [

15,

16] is represented by the municipalities located within a radius of up to 5 km from the Amazon River, including the cities of Barcarena and Abaetetuba in the state of Pará. These are urban centers developed in river deltas, vulnerable to flooding, situated at altimetric levels at sea level or low elevations, prone to the effects of water level variations, and densely populated, with many infrastructure deficiencies. Their inhabitants face the effects of water, soil, and air pollution, in addition to precarious housing infrastructure [

17]. The area of coverage corresponds to the boundaries of the watersheds that flow into the estuary, as the object of analysis is the occupation of marginal areas along watercourses (

Figure 1).

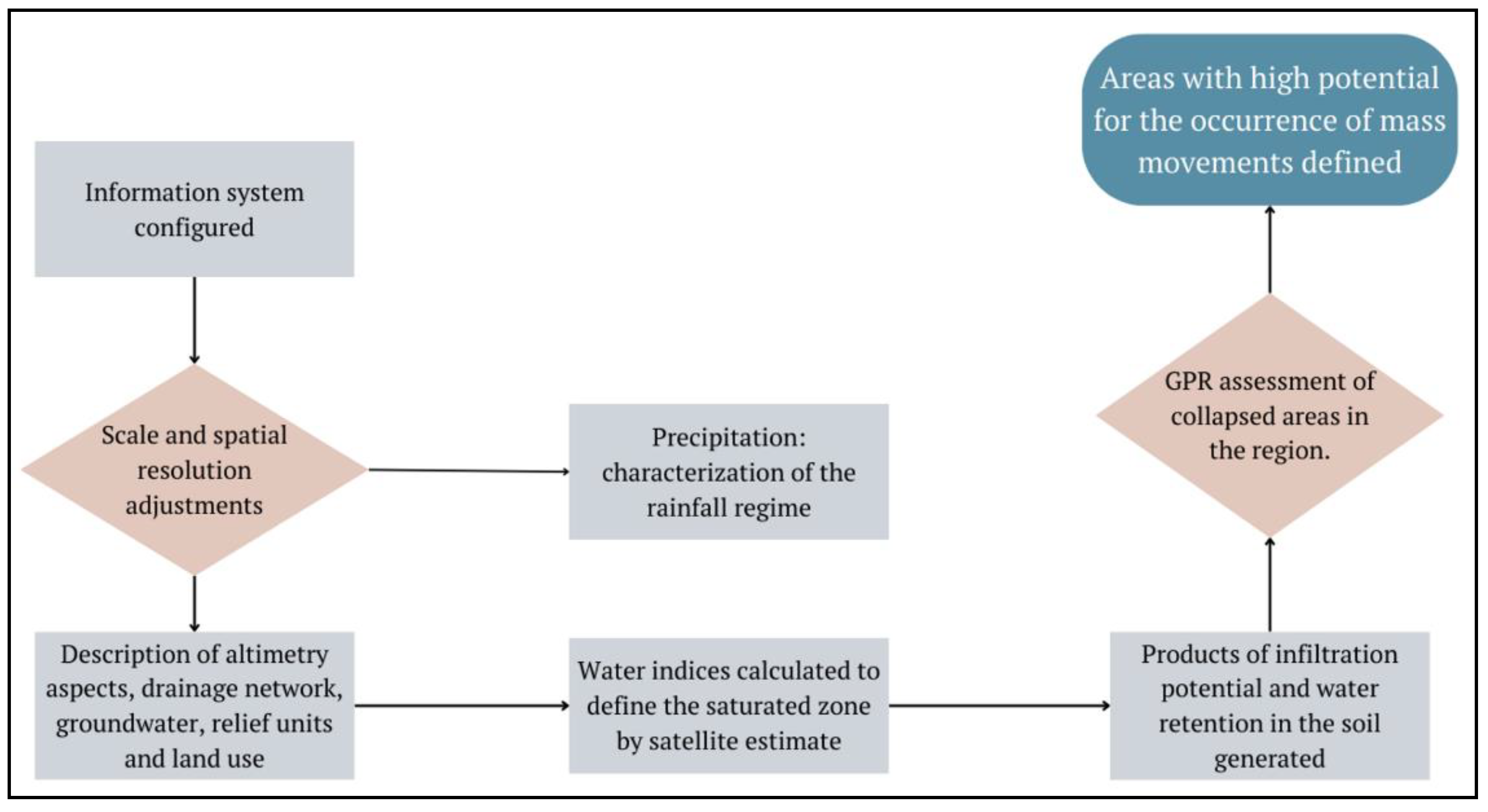

The adopted sequence starts with the diagnosis of the area through the configuration of the base cartography, the characterization of the area affected by mass movements using ground-penetrating radar (GPR), and the identification of the most critical areas associated with soil water saturation and collapse potential.

Figure 2 summarizes the main steps, highlighting the following methodological elements: 1) Configuration of the applied information system and the supporting cartography; 2) Adjustment of geospatial relationships associated with the scale and spatial resolution of the sensors adopted; 3) Evaluation of the main analysis products:

(a) Rainfall precipitation – for characterizing the region’s rainfall regime;

(b) Definition of the regional pattern, with the description of physical aspects associated with altimetry, drainage network, groundwater, and relief units;

4) Application of water indices for characterizing the saturated zone through satellite estimation, as well as evaluation products for the potential of water infiltration and retention in the soil, derived from surface runoff behavior and soil textural characteristics;

5) Zoning according to areas with the highest potential for mass movements due to soil saturation characteristics and land use;

6) In situ evaluation using Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR) of areas that experienced collapse and their relationship with the obtained zoning.

2.2. Diagnosis and Data Base

In the assessment of the region, geological and geomorphological characteristics, altimetry, surface and groundwater conditions, rainfall precipitation, and infiltration potential in the saturated zone were evaluated.

Table 1 and

Table 2 summarize the information bases used, extracted from Google Earth Engine (GEE) and validated by the cited authors, in addition to the parameters calculated for the definition of spectral indices [

18,

19].

2.3. Distribution of Rainfall

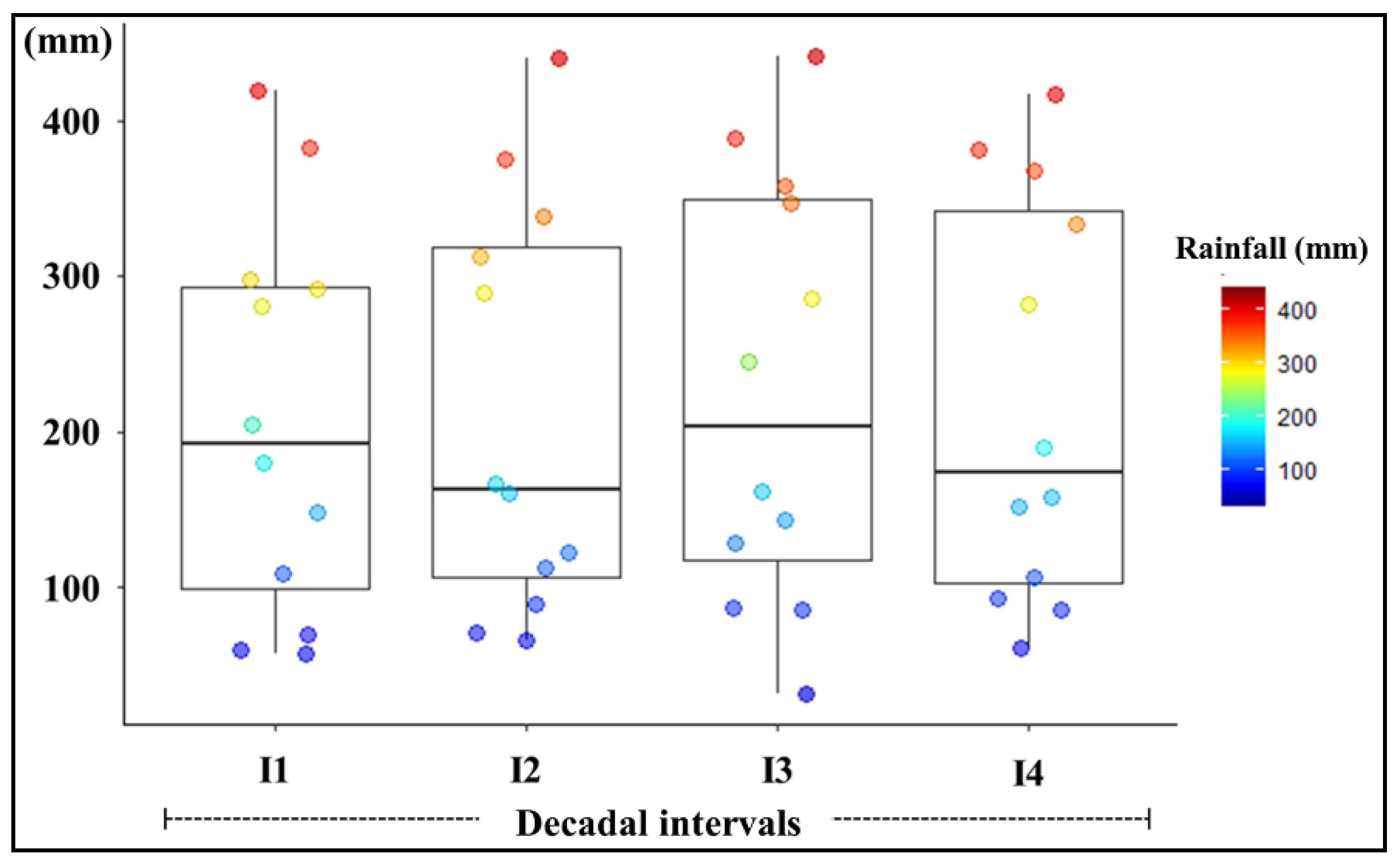

In the assessment of rainfall distribution, four decadal intervals were compared: 1980–1989 (I1), 1990–1999 (I2), 2000–2009 (I3), and 2010–2019 (I4). The data were obtained from the rainfall station 148010 of the National Water and Basic Sanitation Agency (ANA), made available through the HidroWeb platform [

29]. Means, standard deviations, and the normality of the decadal intervals were calculated using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Given the non-normal distribution of the data (

p < 0.05), the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was applied to determine whether there were statistically significant differences (

p < 0.05).

2.4. Assessment of Saturated Zone Behaviour

The composition of water indices for characterizing the saturated zone adopted the works of Landerer and Swenson [

21], Li et al. [

30], Laonamsai et al. [

31], and Liu et al. [

32] as references. April 2021 was used as the baseline month-year, as it represents the rainy season in the region and has the lowest cloud cover. These indices detect changes in relative water content, where values ≥ 0 indicate greater presence, and the opposite indicates lower water content. NDWI and MNDWI range from -1 to 1, while WRI and AWEI can exceed this range, though maintaining the same behavioral pattern (

Table 2).

The use of the GRACE sensor showed a major limitation due to its spatial resolution. However, since it is a product aimed at detecting equivalent water mass anomalies [

21], its importance was recognized in strengthening the identification of a zone with greater groundwater contribution.

The definition of water retention potential in the saturated zone (superficial soil layer) used products for soil textural characterization [

27] and hydrographic density [

23]. These were weighted on a scale from 1 (lowest water retention potential) to 5 (highest water retention potential); subsequently, the matrix product was reclassified into the categories of very high, high, moderate to high, moderate to low, low, and very low potential. The objective was to define the behavior of water stored in the soil, considering aspects related to texture (grain size); layers with contrasting properties in the soil profile; and groundwater close to the surface. The expected pattern is an increase in sandy texture classes up to medium texture as fine fractions (silt plus clay) increase, reaching the maximum limit in silty texture classes. After that, the general trend is a decrease toward texture classes with a predominance of the clay fraction [

28].

In the characterization of wetland areas most favorable for water concentration, an association was adopted between infiltration potential (soil water content (% volume) up to 200 cm) and water retention in the saturated zone, characterizing surface and subsurface retention areas. The use of multiple sensors with different spatial resolutions had its effect reduced by pixel resampling (90 m), aiming for suitability in integrated processing.

The model generated to characterize areas with the highest potential for movement due to water accumulation in the surface soil layers used the product of infiltration potential distribution (where the closer to 1, the greater the concentration) and water saturation, based on the soil’s textural characteristics. The resulting categorization took into account the increased effect of the degree of intensification of existing land use. This method is based on the principle of the ecological cooling service function of soil cover [

33], reflecting the greater water content and slower evaporation in the presence of vegetation (shading effect), and the intense evaporation that occurs in its absence.

In the comparative analysis between the indices, a regular grid of points (1050) distributed across the area was adopted, using the Euclidean distance between them as a reference. The objective was to identify the zones with the highest characterization of water retention in the soil, as well as to evaluate the effect of the resulting dispersion.

2.5. Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) Survey

Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) is a high-resolution geophysical method that uses the emission of high-frequency electromagnetic pulses to image dielectric discontinuities in the subsurface [

34]. The waves are transmitted by a transmitting antenna and reflected by interfaces where there is a contrast in the dielectric properties of the materials. These reflections are captured by a receiving antenna. The frequency range used in GPR generally varies between 10 MHz and 2.5 GHz. Higher frequencies allow for greater resolution but with shallower investigation depth, while lower frequencies favor deeper penetration at the cost of resolution loss [

35].

In the field acquisitions, the GSSI SIR-3000 system was used, coupled with a 200 MHz monostatic antenna, operating in continuous acquisition mode by distance. This configuration was selected to offer a balance between resolution and depth, suitable for the geological characteristics and the study’s objectives. The raw data were processed using the ReflexW software, applying conventional preprocessing procedures, including gain correction, background noise removal, frequency filtering, and migration, aiming to enhance the reflections of interest and facilitate the stratigraphic and structural interpretation of the radar profiles.

The data acquisition focused on obtaining twelve radargram sections in an area affected by mass movements in the municipality of Abaetetuba (PA). Between the sections surveyed, seven were conducted along public roads oriented parallel to the coastal line adjacent to the estuary, with a predominant NE–SW direction. The remaining five sections were arranged perpendicularly, following a NW–SE direction. Topographic correction was not applied, as the investigated area presented an almost flat terrain, without significant altimetric variations that would justify this procedure.

3. Results

3.1. Wetland Profile: Influence of Rainfall

The results showed that rainfall follows a well-defined pattern, with a rainy season (P+) (December to May) and a less rainy season (P-) (June to November) over the 40 years studied. The accumulated annual precipitation ranged from 70.07 ± 55.35 mm·month⁻¹ to 413.34 ± 127.51 mm·month⁻¹ (

Figure 3).

No statistically significant differences were found between the decadal intervals (p < 0.05). There was an increase of 1.76% in rainfall from I2 compared to I1, a 6.30% increase in I3 compared to I2, and a reduction of 2.76% in I4 compared to I3. During the I2 and I3 intervals, there was an increase in rainfall in both P+ and P-, ranging from 0.12% to 8.51% compared to I1 and I2, respectively.

The intensification of rainfall observed during I3 may be associated with the higher frequency of La Niña events, which promote the cooling of equatorial Pacific waters, reinforcing the Walker circulation and favoring the displacement of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) southward, increasing rainfall in Eastern Amazonia. Meanwhile, in I4, the predominance of El Niño events, characterized by Pacific warming, tends to weaken atmospheric circulation and shift the ITCZ northward, reducing rainfall in the region [

36,

37,

38].

3.2. Wetland Profile: Altimetry and Landforms

The region presents the greatest amplitudes in the east-northeast, decreasing towards the riverbanks, with the predominance of low slopes (

Figure 4). The classification by Landforms indicated gentle amplitudes (Unit 1), usually associated with low-slope hillsides (less than 2%, Unit 2), with an alternation of well-defined valleys (Unit 3) and more open ones (Unit 4). The marginal areas along the rivers are consistent with fluvial deposits, while the others correspond to the sediments of the Barreiras Group, which define the “Tabuleiros da Zona Bragantina”. The dominant structure is the prevalence of Fluvial Plains with low relief amplitude (less than 30 m), underlain by sedimentary rocks of Tertiary or Tertiary-Quaternary age from the Barreiras Group and post-Barreiras sediments, frequently covered by detrital-lateritic layers. The dissection forms exhibit rounded reliefs, similar to broad and smooth hills. The landscape also includes the Alluvial Plain (

várzea), with meandering river channels, floodplains, and marginal levees, as well as the Estuarine Plain, featuring estuarine channels, muddy tidal plains. The resulting soil cover consists of well-drained levels with low natural fertility, thick and leached, typically characterized by Dystrophic Yellow Oxisols, Gleysols, Red-Yellow Argisols, and Quartzarenic Neosols [

39,

40,

41].

3.3. Wetland Profile: Hydrographic Density and Infiltration Potential

Surface runoff (

Figure 5A) and infiltration (

Figure 5B) show a relationship conditioned by the topography and texture of the soil-rock alteration profile. Where sandy and medium clayey-to-sandy textures predominated, the behavior was favorable to soil percolation and storage in the saturated zone, indicating the highest potentials (values close to 1) for infiltration behavior. Sandy soils vary in terms of grain size, clay content, and natural processes (e.g., biological activities); they frequently exhibit high hydraulic conductivity, gas permeability, and specific heat capacity, but low field capacity, organic carbon concentration, and cation exchange capacity [

42]. In areas dominated by clayey to very clayey profiles, water would have more difficulty percolating through the soil profile, making surface runoff more likely (indicating surface retention and less percolation toward the saturated zone), characterizing a saturation level very close to the surface [

43].

The resulting product (

Figure 5C) reflects what is expected for the region based on the characteristics of the relief units, with the predominance of fluvial plains (with low relief amplitude), alluvial (

várzea), and estuarine plains influenced by tides and muddy textures, indicating good drainage.

Forest areas, including riparian zones, play a fundamental role in soil drainage conditions; however, there are limitations due to current land use practices and soil textural and management characteristics [

44].

3.4. Spectral Indices: Water and Land Cover

The analysis using spectral indices strengthens the observed results, with the concentration of areas with lower response potential as wetlands in the east and southeast, in the topographically higher region. The area adjacent to the estuary is the most dynamic, with the spectral indices demonstrating good responsiveness to the presence of water. GRACE showed the greatest limitation, mainly due to its spatial resolution, but it still indicated a strong hydric influence near the surface (

Figure 6E).

Spectral indices that include NIR and SWIR bands help enhance the soil/water contrast [

45]; however, there are response differences among the water indices. The non-uniformity of response is related to the processes of formation, coverage, and spatial distribution of soil types. These soils exhibit an increase in reflectance from the visible to the near-infrared spectrum, where the 1.4 µm and 1.9 µm bands are related to soil water content, influenced by the types and amounts of minerals, organic matter content, and the surface texture of the soil [

46].

Considering values closer to 1 as hydric indicator, NDWI and MNDWI (

Figure 6A, 6B) recorded behavior similar to that identified for wetlands and vegetated areas [

31,

47], including WRI (higher values and farther from zero) and AWEI (values ranging from zero to 1) (

Figure 6C, 6D). The same pattern of response similarity was detected across different sensors, with an accuracy greater than 90% for NDWI, MNDWI, and AWEI for the same targets [

48]. The paired analysis of the indices through linear regression obtained

p < 0.0001 for all compositions and highlighted an R² value (0.87) and a Pearson correlation (0.936) for the MNDWI × AWEI relationship, a behavior previously discussed for other regions [

31,

49]. However, it is important to recognize the extent of landscape alteration (

Figure 6F), including urbanization (soil impermeability) and the expansion of exposed soil areas due to the removal of forest cover and its replacement with other forms of land cover, such as those intended for agricultural use.

The comparison with the data from

Figure 5, regarding infiltration potential and saturation, and

Figure 7 (A, B) shows that the indices concentrate their response in zones with above 30% infiltration capacity and areas with low to moderately low saturation potential. NDVI was the index that showed the least variation around the mean, while the other indices displayed similar behavior in terms of mean, median, and standard deviation (

Figure 7C), with all 0.75 quartiles approaching values that represent the presence of water.

3.5. Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR) Application

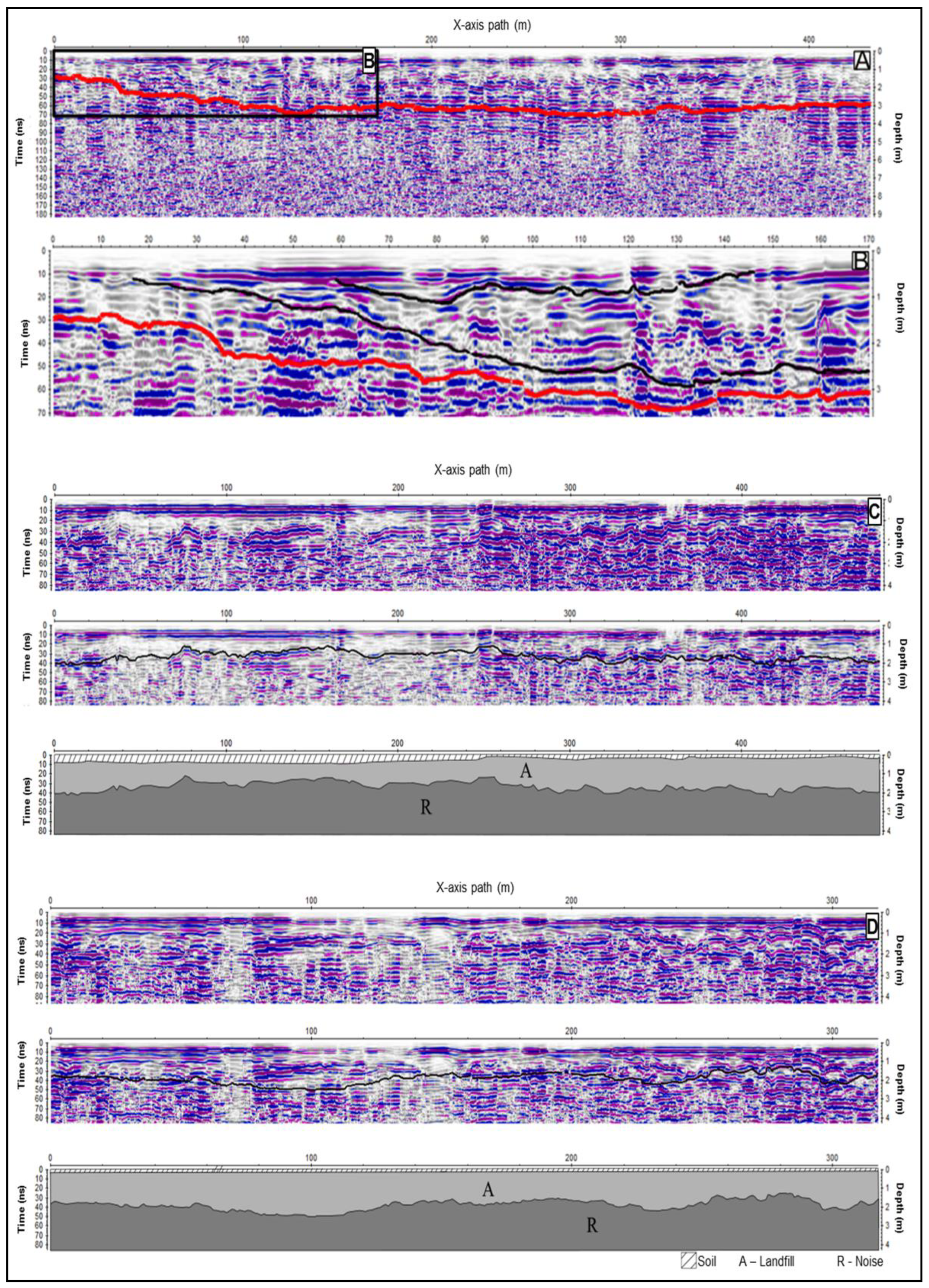

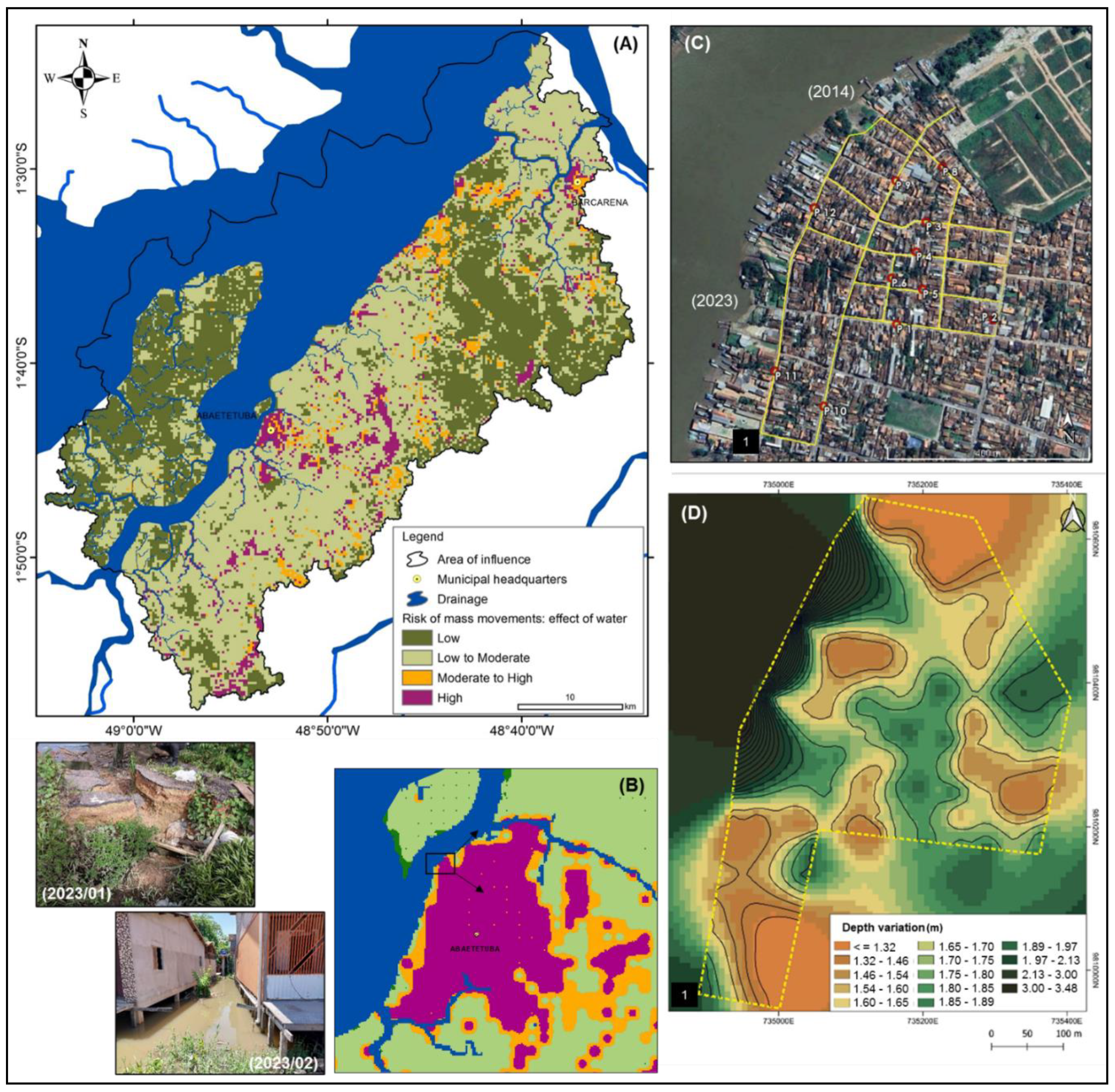

In a region of Abaetetuba (PA) that experienced two documented mass movement events, in 2014 and 2023, subsurface characterization was carried out using Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) (

Figure 8).

The data obtained reveal the presence of reflectors with variations in amplitude and continuity, indicating zones with different dielectric responses, associated with material heterogeneity and moisture presence. The propagation of electromagnetic waves was limited to a depth of approximately 4 meters, consistent with the high electrical conductivity of materials near the surface, influenced by factors such as moisture content, porosity, the presence of clays, and conductive minerals. The estimated propagation speed for the medium was 0.9 m/ns, compatible with saturated soils of fine texture.

In

Figure 8A, a significant thickening of the landfill layer is observed, with greater depth compared to the other profiles.

Figure 8B shows the radargram obtained near the collapse area recorded in 2023, where irregular reflection patterns are identified, suggesting changes in soil compaction or composition, possibly associated with the observed instability (see location in

Figure 9C).

The profile represented in

Figure 8C, oriented perpendicularly to the estuary, shows the landfill layer with a thickness variation between 1 and 2 meters. Meanwhile,

Figure 8D, obtained in the direction perpendicular to the 2014 collapse site, presents strong reflection associated with high dielectric contrast, highlighting a concave feature, consistent with moisture accumulation and sedimentary characteristics of a floodplain. The occurrence of intense and continuous reflections suggests a siliciclastic environment dominated by fine and saturated sediments.

The integrated analysis with risk and land use data shows that the areas affected by the collapses coincide with zones of high susceptibility to mass movements induced by water action (

Figure 9A). The interaction between infiltration, water saturation, and anthropogenic alteration of the land—particularly through the replacement of forest cover—indicates that these areas function as wetlands with unstable dynamics.

Figure 9D, derived from the interpolation of GPR data, reveals variations in the thicknesses of surface layers, with shallow contacts and discontinuities in the sectors adjacent to the estuary, especially near the areas affected in 2014 and 2023. These features suggest the presence of unconsolidated substrates of different natures, conditioning the local vulnerability to soil collapse.

4. Discussion

The methodological contribution presented for the study of mass movements associated with soil water saturation aims to assist and complement other studies already developed, with the addition of variables such as precipitation intensity—including duration and cumulative amount [

53]; remote sensing assessments with high-resolution images and direct extraction of movement indicators [

54]; and indicators of geological structure and resulting terrain morphology [

55].

In the evaluated region, the research contributes to risk management, where previous studies have already indicated the existing natural vulnerability [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56] and the need for risk minimization strategies. These include expanding detailed studies, such as those carried out with GPR, in several other points of the city to characterize the subsurface, along with complementary drilling to identify the thicknesses of the existing soil-rock alteration profile [

57]. Moreover, it is essential to characterize the thicknesses of the landfill material (various grain sizes, including solid waste) present in many parts of the city, which promotes the formation of instability zones.

The integrated mapping using sensors and its association with local surveys with geophysical data proves to be an important strategy for managing potential risk areas. The applications are diverse, involving the assessment of soil deformation processes, subsidence mechanisms, spatial variability of deformation, and displacement rates [

50,

51]. In this context, the use of products from platforms like Google Earth Engine also stands out, offering important advantages due to its architecture with updated data, dynamic geospatial processing, and the possibility of internal (within the platform) or external integration with other databases [

52].

The occupation of areas bordering rivers is common in the Amazon region, so it is necessary to establish a monitoring routine to identify the growth of cities and the natural and human-induced vulnerabilities associated with the removal of forest cover and the direct exposure of soil to rainwater and rivers [

15,

16].

The ADE is a region where intense natural, social and economic dynamics are exhibited, with water being strongly involved in food production, human supply and navigation [

10]. Given this, governance actions by the government must seek to reduce the social vulnerability of populations living in risk zones [

12] by seeking technological proposals [

25,

30,

44] for preventive and corrective management in the most critical areas. One such area is the sector encompassing the right bank of the ADE, which includes the cities of Barcarena and Abaetetuba.

5. Conclusions

The occupation of marginal areas along rivers in the Amazon region is a traditional practice resulting from the historical settlement marked by rivers serving as an alternative for transportation. Consequently, many cities were established and continue to develop along the banks of watercourses, altering the floodplain or wetland landscape. Landfilling became a common practice, generating a heterogeneous profile that is vulnerable to movement and removal by erosive processes, both due to rainfall and fluvial system action.

The analysis methodology developed aimed to address this scenario with the systematic mapping of water-saturated areas with movement potential. Remote sensing was the alternative to the lack of geological and geotechnical data, while in situ GPR evaluation was proposed as a method to detail a previously observed movement condition to investigate the associated causes.

The work was considered successful in doing a mapping process that can be systematically and continuously monitored, also supported by the development of annual water index maps. However, it is recognized that it is necessary to complement this with data from in situ surveys to identify the thickness of the landfill material applied in various areas, as well as specific tests for porosity and permeability of the region’s substrate, at least up to the range of 1.5 to 2 meters, which proved to be the most dynamic.

Local governments need to invest in remote sensor monitoring and drilling surveys to track the development of mass movement features, as well as to understand their relationship with local hydrodynamics, assessing potential groundwater recharge areas that contribute to water circulation in the more subsurface layers. In this way, it would be possible to respond to the local society, which has already experienced material losses associated with mass movement events and the intensification of erosive processes, leading to soil loss and, consequently, the need for intervention in cities and their growth patterns.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.M.L, V.G.Q.N. and S.S.M.; methodology, A.M.M.L, V.G.Q.N. and S.S.M.; formal analysis, A.M.M.L and V.G.Q.N.; investigation and field work, A.M.M.L, V.G.Q.N., S.S.M., A.C.S.O. and Y.A.S.R.; resources, A.M.M.L; writing-original draft preparation, A.M.M.L; writing-review and editing, A.M.M.L, S.S.M. and Y.A.S.R.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) and the Federal University of Pará (UFPA).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this work would like to thank the State of Pará’s Civil Defense and the Hydroenvironmental Studies and Modeling Laboratory at the Federal University of Pará’s Institute of Geosciences.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mansur, A. V.; Brondízio, E. S.; Roy, S.; Hetrick, S.; Vogt, N. D.; Newton, A. An assessment of urban vulnerability in the Amazon Delta and Estuary: a multi-criterion index of flood exposure, socio-economic conditions and infrastructure. Sustainability Science 2016, 11, 625–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, R. M.; Amaral, S.; Monteiro, A. M. V.; Dal’Asta, A. P. “Cities in the forest” and “cities of the forest”: an environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) spatial approach to analyzing the urbanization–deforestation relationship in a Brazilian Amazon state. Ecology and Society 2022, 27, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riquetti, N. B.; Beskow, S.; Guo, L.; Mello, C. R. Soil erosion assessment in the Amazon basin in the last 60 years of deforestation. Environmental Research 2023, 236, 116846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleischmann, A. S.; Papa, F.; Hamilton, S. K.; Fassoni-Andrade, A.; Wongchuig, S.; Espinoza, J. C.; Paiva, R. C. D.; Melack, J. M.; Fluet-Chouinard, E.; Castello, L.; Almeida, R. M.; Bonnet, M. P.; Alves, L. G.; Moreira, D.; Yamazaki, D.; Revel, M.; Collischonn, W. Increased floodplain inundation in the Amazon since 1980. Environmental Research Letters 2023, 18, 034024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staal, A.; Flores, B. M.; Aguiar, A. P. D.; Bosmans, J. H.; Fetzer, I.; Tuinenburg, O. A. Feedback between drought and deforestation in the Amazon. Environmental Research Letters 2020, 15, 044024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, J. C.; Marengo, J. A.; Schongart, J.; Jimenez, J. C. The new historical flood of 2021 in the Amazon River compared to major floods of the 21st century: Atmospheric features in the context of the intensification of floods. Weather and Climate Extremes 2022, 35, 100406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, J. C.; Jimenez, J. C.; Marengo, J. A.; Schongart, J.; Ronchail, J.; Lavado-Casimiro, W.; Ribeiro, J. V. M. The new record of drought and warmth in the Amazon in 2023 related to regional and global climatic features. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 8107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuzied, S. M.; Pradhan, B. Hydro-geomorphic assessment of erosion intensity and sediment yield initiated debris-flow hazards at Wadi Dahab Watershed, Egypt. Georisk 2021, 15, 221–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malka, A. GIS-Based Landslide Susceptibility Modelling in Urbanized Areas: A Case Study of the Tri-City Area of Poland. GeoHazards 2022, 3, 508–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S. M. F.; Rosa, N. C. O processo de urbanização na Amazônia e suas peculiaridades: uma análise do delta do rio Amazonas. Revista Políticas Públicas & Cidades 2017, 5, 81–105. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, J. A. Tempo e espaço urbano na Amazônia no período da borracha. Scripta Nova. Revista Electrónica de Geografía y Ciencias Sociales 2006, 10, 218. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, R. M.; Ferreira, A. E. D. M.; Cardoso, A. C. D.; Monteiro, A. M. V.; Dal’Asta, A. P.; Carmo, M. B. S.; Amaral, S. A trama urbana amazônica: proposta metodológica para reconhecimento de um território de possibilidades. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Urbanos e Regionais 2024, 26, e202433pt. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, A. C. D.; Lima, J. J. F.; Ponte, J. P. X.; Ventura, R. D. S.; Rodrigues, R. M. Morfologia urbana das cidades amazônicas: a experiência do Grupo de Pesquisa Cidades na Amazônia da Universidade Federal do Pará. URBE - Revista Brasileira de Gestão Urbana 2020, 12, e20190275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milana, J. P.; Geisler, P. Forensic Geology Applied to Decipher the Landslide Dam Collapse and Outburst Flood of the Santa Cruz River, San Juan, Argentina. GeoHazards 2022, 3, 252–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brondizio, E. S.; Vogt, N.; Mansur, A. V.; Anthony, E. J.; Costa, S. M. F.; Hetrick, S. A conceptual framework for analyzing deltas as coupled social-ecological systems: an example from the Amazon River Delta. Sustainability Science 2016, 11, 591–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, Y. A. D. S.; Lima, A. M. M. D.; Silva, C. M. S. E.; Franco, V. D. S.; Raiol, L. L.; Oliveira, I. S. D.; Dias, M. L. M.; Beltrão Júnior, P. R. E. Hydro-meteorological dynamics of rainfall erosivity risk in the Amazon River Delta-Estuary. Journal of Water and Climate Change 2025, jwc2025544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, D. A.; Caldwell, R. L.; Brondizio, E. S.; Siani, S. M. O. Coastal flooding will disproportionately impact people on river deltas. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 4741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L. E.; Amorim, G.; Grigio, A. M.; Paranhos Filho, A. C. Análise Comparativa entre Métodos de Índice de Água por Diferença Normalizada (NDWI) em Área Úmida Continental. Anuário do Instituto de Geociências 2018, 41, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Lin, N.; Liu, Z. Comparing Water Indices for Landsat Data for Automated Surface Water Body Extraction under Complex Ground Background: A Case Study in Jilin Province. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LP DAAC. Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center; U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), Earth Observing System Data and Information System (EOSDIS)/National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), 2024; Available online: https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/data/data-citations-and-guidelines/.

- Landerer, F. W.; Swenson, S. C. Accuracy of scaled GRACE terrestrial water storage estimates. Water Resources Research 2012, 48, W04531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, T. G.; Rosen, P. A.; Caro, E.; Crippen, R.; Duren, R.; Hensley, S.; Kobrick, M.; Paller, M.; Rodriguez, E.; Roth, L.; Seal, D.; Shaffer, S.; Shimada, J.; Umland, J.; Werner, M.; Oskin, M.; Burbank, D.; Alsdorf, D. E. The shuttle radar topography mission. Reviews of Geophysics 2007, 45, RG2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, B.; Verdin, K.; Jarvis, A. New global hydrography derived from spaceborne elevation data. Eos, Transactions 2008, 89, 93–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengl, T.; Gupta, S. Soil water content (volumetric%) for 33kPa and 1500kPa suctions predicted at 6 standard depths (0, 10, 30, 60, 100 and 200 cm) at 250 m resolution (Version v01). Zenodo 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Papritz, A.; Lehmann, P.; Hengl, T.; Bonetti, S.; Or, D. Global Mapping of Soil Water Characteristics Parameters-Fusing Curated Data with Machine Learning and Environmental Covariates. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M. C.; Potapov, P. V.; Moore, R.; Hancher, M.; Turubanova, S. A.; Tyukavina, A.; Thau, D.; Stehman, S. V.; Goetz, S. J.; Loveland, T. R.; Kommareddy, A.; Egorov, A.; Chini, L.; Justice, C. O.; Townshend, J. R. G. High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. Science 2013, 342, 850–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SGB. Estimativa de água disponível nos solos do Brasil; Serviço Geológico do Brasil - SGB, Catálogo PRONASOLOS, 2024; Escala: 1:500.000; Available online: https://geosgb.sgb.gov.br/geosgb/pronasolos.html.

- EMBRAPA. Avaliação, predição e mapeamento de água disponível em solos do Brasil. Boletim de pesquisa e desenvolvimento 2022, 146p. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil. Agência Nacional de Águas e Saneamento Básico - ANA. HidroWeb: Sistema de Informações Hidrológicas. 2024. Available online: https://www.snirh.gov.br/hidroweb.

- Li, Q.; Lu, L.; Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Sui, Y.; Guo, H. MODIS-derived spatiotemporal changes of major lake surface areas in arid Xinjiang, China, 2000–2014. Water 2015, 7, 5731–5751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laonamsai, J.; Julphunthong, P.; Saprathet, T.; Kimmany, B.; Ganchanasuragit, T.; Chomcheawchan, P.; Tomun, N. Utilizing NDWI, MNDWI, SAVI, WRI, and AWEI for Estimating Erosion and Deposition in Ping River in Thailand. Hydrology 2023, 10, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Lin, N.; Liu, Z. Comparing Water Indices for Landsat Data for Automated Surface Water Body Extraction under Complex Ground Background: A Case Study in Jilin Province. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, A. D.; Vulova, S.; Meier, F.; Förster, M.; Kleinschmit, B. Mapping evapotranspirative and radiative cooling services in an urban environment. Sustainable Cities and Society 2022, 85, 104051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizos, A.; Plati, C. Accuracy of pavement thickness estimation using different ground penetrating radar analysis approaches. NDT & E International 2007, 40, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annan, A. P. Electromagnetic Principles of Ground Penetrating Radar. In Ground Penetrating Radar: Theory and Applications; Jol, H. M., Ed.; Elsevier, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, J. H.; Zeng, N. An Atlantic influence on Amazon rainfall. Climate Dynamics 2010, 34, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limberger, L.; Silva, M. E. S. Precipitação na bacia amazônica e sua associação à variabilidade da temperatura da superfície dos oceanos Pacífico e Atlântico: uma revisão. GEOUSP: Espaço e Tempo 2016, 20, 3, 657–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cai, W.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, X.; Li, Z. Near-term projection of Amazon rainfall dominated by phase transition of the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation. Climate and Atmospheric Science 2024, 7, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- João, X. S. J.; Teixeira, S. G.; Fonseca, D. D. F. Geodiversidade do estado do Pará. Belém, CPRM, 2013, 256 p.

- Folha SA.22 Belém. Carta Hidrogeológica, Escala 1:1.000.000. Programa Geologia do Brasil – Cartografia Hidrogeológica. 2016; Serviço Geológico do Brasil (SGB/CPRM).

- El-Robrini, M.; Silva, P. V.; Magno, C.; Rodrigues, M. V. Morfodinâmica e transporte de sedimentos em praias amazônicas de meso-marés: o caso da Vila do Conde (Barcarena/Pará). Caderno de Geografia 2023, 33, 1300–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Hartemink, A. E. Soil and environmental issues in sandy soils. Earth-Science Reviews 2020, 208, 103295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronswijk, J. J. B. Modeling of water balance, cracking and subsidence of clay soils. Journal of Hydrology 1988, 97, 3–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, C.; Creamer, R. E.; Schulte, R. P.; O’Sullivan, L.; Jordan, P. A functional land management conceptual framework under soil drainage and land use scenarios. Environmental Science & Policy 2016, 56, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, A.; Cheng, Q.; Peng, H.; Altan, O.; Li, Y.; Ara, I.; Huq, E.; Ali, Y.; Saleem, N. Review of spectral indices for urban remote sensing. Photogrammetric Engineering & Remote Sensing 2021, 87, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Zhou, Y.; Gowda, P. H.; Dong, J.; Zhang, G.; Kakani, V. G.; Wagle, P.; Chen, L.; Flynn, C.; Jiang, W. Application of the water-related spectral reflectance indices: A review. Ecological Indicators 2019, 98, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wei, H.; Feyisa, G. L.; Castro Tayer, T.; Ma, G.; Wu, H.; Pan, Y. Evaluating spectral indices for water extraction: limitations and contextual usage recommendations. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2025, 139, 104510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Dong, J.; Xiao, X.; Xiao, T.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, G.; Zou, Z.; Qin, Y. Open surface water mapping algorithms: A comparison of water-related spectral indices and sensors. Water 2017, 9, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gümüş, M.G. Performance Analysis of Water Extraction Indices with Geospatial and Statistical Techniques Using Google Earth Engine Platform: A Case Study of Ramsar Wetlands in Türkiye. J Indian Soc Remote Sens 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevil, J.; Gutiérrez, F.; Carnicer, C.; Carbonel, D.; Desir, G.; García-Arnay, Á.; Guerrero, J. Characterizing and monitoring a high-risk sinkhole in an urban area underlain by salt through non-invasive methods: Detailed mapping, high-precision leveling and GPR. Engineering Geology 2020, 272, 105641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago, A. L.; Borges, W. R.; Barros, J. S.; Sousa Amaral, E. GPR application for the characterization of sinkholes in Teresina, Brazil. Environmental Earth Sciences 2022, 81, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheip, C. M.; Wegmann, K. W. HazMapper: a global open-source natural hazard mapping application in Google Earth Engine. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences Discussions 2020, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. W.; Hung, C.; Lin, G. W.; Liou, J. J.; Lin, S. Y.; Li, H. C.; Chen, Y. M.; Chen, H. Preliminary establishment of a mass movement warning system for Taiwan using the soil water index. Landslides 2022, 19, 1779–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assis, L. E.; Marques, E. A. G. , Lima, C. A., Menezes, S. J. M. C., & Roque, L. A. Mapping of Geological-Geotechnical Risk of Mass Movement in an Urban Area in Rio Piracicaba, MG, Brazil. Soils and Rocks 2020, 43, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malka, A. GIS-Based Landslide Susceptibility Modelling in Urbanized Areas: A Case Study of the Tri-City Area of Poland. GeoHazards 2022, 3, 508–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandeira, I. C. N.; Adamy, A.; Andretta, E. R.; Costa da Conceição, R. A.; Andrade, M. M. N. Terras caídas: Fluvial erosion or distinct phenomenon in the Amazon? Environmental Earth Sciences 2018, 77, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, A.; Galvão, P.; Sousa, J.; Silva, I.; Carneiro, R. N. Relations of the groundwater quality and disorderly occupation in an Amazon low-income neighborhood developed over a former dump area, Santarém/PA, Brazil. Environment, development and sustainability 2019, 21, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Amazon River Delta-Estuary (ADE): Coastal and island river basins of the municipalities of Abaetetuba and Barcarena.

Figure 1.

Amazon River Delta-Estuary (ADE): Coastal and island river basins of the municipalities of Abaetetuba and Barcarena.

Figure 2.

Survey framework developed.

Figure 2.

Survey framework developed.

Figure 3.

Decadal distribution of precipitation: 1980-1989 (I1), 1990-1999 (I2), 2000-2009 (I3) and 2010-2019 (I4).

Figure 3.

Decadal distribution of precipitation: 1980-1989 (I1), 1990-1999 (I2), 2000-2009 (I3) and 2010-2019 (I4).

Figure 4.

(a) Hydrogeological units, (b) altimetric levels and (c) landforms: geological and geomorphological evaluation.

Figure 4.

(a) Hydrogeological units, (b) altimetric levels and (c) landforms: geological and geomorphological evaluation.

Figure 5.

(a) Drainage density, (b) infiltration potential (up to 200 cm) and (c) saturation potential in water: the behavior of water in the soil profile.

Figure 5.

(a) Drainage density, (b) infiltration potential (up to 200 cm) and (c) saturation potential in water: the behavior of water in the soil profile.

Figure 6.

(a) Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI), (b) Modification of Normalized Difference Water Index (MNDWI), (c) Water Ratio Index (WRI), (d) Automated Water Extraction Index (AWEI), (e) Water Mass Equivalent (GRACE) and (f) Degree of land use intensification: land use and presence of wetlands. Correlation sample: NDWI x MNDWI, Person = 0.170; NDWI x WRI, Person = 0.209; NDWI x AWEI, Person = 0.222; MNDWI x WRI, Person = 0.287; MNDWI x AWEI, Person = 0.936; WRI x AWEI, Person = 0.195.

Figure 6.

(a) Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI), (b) Modification of Normalized Difference Water Index (MNDWI), (c) Water Ratio Index (WRI), (d) Automated Water Extraction Index (AWEI), (e) Water Mass Equivalent (GRACE) and (f) Degree of land use intensification: land use and presence of wetlands. Correlation sample: NDWI x MNDWI, Person = 0.170; NDWI x WRI, Person = 0.209; NDWI x AWEI, Person = 0.222; MNDWI x WRI, Person = 0.287; MNDWI x AWEI, Person = 0.936; WRI x AWEI, Person = 0.195.

Figure 7.

(A) Saturation potential in water (SAT). (B) Infiltration potential (INF) Histogram distribution. Normalised Difference Water Index (NDWI), Modified Normalised Difference Water Index (MNDWI), Automated Water Extraction Index (AWEI) and Water Ratio Index (WRI): boxplot distribution. NDWI: Mean: 0.010; median: 0.003, standard deviation: 0.054; quartiles (0.25, 0.5, 0.75) = -0.009/0.003/0.022. MNDWI: mean -0.397, median -0.412, standard deviation 0.054. -0.412; standard deviation: 0.128; quartiles (25th, 50th, 75th) = -0.485, -0.412, -0.327. WRI: Mean: 0.384; median: 0.383, standard deviation: 0.130; quartiles (0.25, 0.5, 0.75): 0.310, 0.383, 0.467. AWEI: Mean: -0.549; Median: -0.585, standard deviation: 0.170; quartiles (0.25, 0.5, 0.75) = -0.663, -0.585, -0.467.

Figure 7.

(A) Saturation potential in water (SAT). (B) Infiltration potential (INF) Histogram distribution. Normalised Difference Water Index (NDWI), Modified Normalised Difference Water Index (MNDWI), Automated Water Extraction Index (AWEI) and Water Ratio Index (WRI): boxplot distribution. NDWI: Mean: 0.010; median: 0.003, standard deviation: 0.054; quartiles (0.25, 0.5, 0.75) = -0.009/0.003/0.022. MNDWI: mean -0.397, median -0.412, standard deviation 0.054. -0.412; standard deviation: 0.128; quartiles (25th, 50th, 75th) = -0.485, -0.412, -0.327. WRI: Mean: 0.384; median: 0.383, standard deviation: 0.130; quartiles (0.25, 0.5, 0.75): 0.310, 0.383, 0.467. AWEI: Mean: -0.549; Median: -0.585, standard deviation: 0.170; quartiles (0.25, 0.5, 0.75) = -0.663, -0.585, -0.467.

Figure 8.

Investigation profiles of an area affected by mass movements in Abaetetuba (PA), obtained by ground-penetrating radar (GPR). (A) Profile P12 shows a thicker landfill layer with a depth of over 2 metres. (B) A detailed view of Profile P12 in the area that collapsed in 2023 shows discontinuous reflections and irregular patterns associated with soil instability. (C) Profile P1, which is perpendicular to the estuary and shows variations in the thickness of the landfill layer between 1 and 2 metres. (D) Profile P8 is transverse to the area of collapse recorded in 2014 and is characterized by a strong electromagnetic signal and a concave feature, which are possibly associated with greater water saturation and the presence of fine sediments.

Figure 8.

Investigation profiles of an area affected by mass movements in Abaetetuba (PA), obtained by ground-penetrating radar (GPR). (A) Profile P12 shows a thicker landfill layer with a depth of over 2 metres. (B) A detailed view of Profile P12 in the area that collapsed in 2023 shows discontinuous reflections and irregular patterns associated with soil instability. (C) Profile P1, which is perpendicular to the estuary and shows variations in the thickness of the landfill layer between 1 and 2 metres. (D) Profile P8 is transverse to the area of collapse recorded in 2014 and is characterized by a strong electromagnetic signal and a concave feature, which are possibly associated with greater water saturation and the presence of fine sediments.

Figure 9.

Integrated landslide risk information and GPR data in the Abaetetuba urban area (PA). (A) Regional map of landslide risk due to water action, with highlighting of areas of high susceptibility. (B) Local risk map in the central area of Abaetetuba, overlayed with the urban boundaries. (C) Satellite image of the study area with the location of the GPR profiles (P1 to P12) and the marking of the affected areas in 2014 and 2023. (D) Digital model of the subsoil obtained by interpolation of the GPR data. It shows variations in thickness and shallow discontinuities in the areas adjacent to the estuary, compatible with zones of instability. 2023/01 and 2023/02: Photographs illustrating the effects of the collapse event that occurred in 2023.

Figure 9.

Integrated landslide risk information and GPR data in the Abaetetuba urban area (PA). (A) Regional map of landslide risk due to water action, with highlighting of areas of high susceptibility. (B) Local risk map in the central area of Abaetetuba, overlayed with the urban boundaries. (C) Satellite image of the study area with the location of the GPR profiles (P1 to P12) and the marking of the affected areas in 2014 and 2023. (D) Digital model of the subsoil obtained by interpolation of the GPR data. It shows variations in thickness and shallow discontinuities in the areas adjacent to the estuary, compatible with zones of instability. 2023/01 and 2023/02: Photographs illustrating the effects of the collapse event that occurred in 2023.

Table 1.

Assumed information base and associated sensors. Grace (PG), The Normalised Difference Water Index (NDWI), the Modified Normalised Difference Water Index (MNDWI), the Water Ratio Index (WRI) and the Automated Water Extraction Index (AWEI).

Table 1.

Assumed information base and associated sensors. Grace (PG), The Normalised Difference Water Index (NDWI), the Modified Normalised Difference Water Index (MNDWI), the Water Ratio Index (WRI) and the Automated Water Extraction Index (AWEI).

| Product |

Description |

Source |

Indicator (*) |

| (1) |

MODIS Ground, Bands 1-7, 500 m resolution. |

[20] |

MNDWI, WRI, AWEI |

| (2) |

MODIS Ground, water content response, 500 m resolution. |

[20] |

NDWI |

| (3) |

GRACE, water mass equivalent (water thickness) anomalies, derived from time-varying gravity observations, 111 km resolution. |

[21] |

PG |

| (4) |

Shuttle Radar Topography Mission. The SRTM V3 (SRTM Plus) product is provided by NASA JPL at 1 arcsecond (~30m) resolution. |

[22] |

Digital Elevation Model and landform |

| (5) |

The datasets at 3 arc-seconds (~90m) are the Void-Filled DEM, Hydrologically Conditioned DEM, and Drainage (Flow) Direction. |

[23] |

Hydrographic density |

| (6) |

Soil water content (% vol.) for 33kPa and 1500kPa suctions predicted at 6 standard depths (200 cm) at 250 m resolution. |

[24,25] |

Infiltration potential |

| (7) |

Hansen Global Forest Change v1.11 (2000-2023), 30.92 m resolution. Time-series analysis of Landsat images - global forest extent and change. |

[26] |

Land cover change |

| (8) |

The volume of water stored in the soil and accessible to plants is a parameter used in the modeling of agroclimatic risk in Brazil. |

[27,28] |

Soil available water |

Table 2.

Parameters evaluated: The Normalised Difference Water Index (NDWI), the Modified Normalised Difference Water Index (MNDWI), the Water Ratio Index (WRI) and the Automated Water Extraction Index (AWEI).

Table 2.

Parameters evaluated: The Normalised Difference Water Index (NDWI), the Modified Normalised Difference Water Index (MNDWI), the Water Ratio Index (WRI) and the Automated Water Extraction Index (AWEI).

| |

Parameters |

Source |

| |

|

[18,19] |

|

|

|

| |

| |

Spectral Range - MODIS Sensor Bands Product MOD09A1 |

|

| |

Band 3 |

B |

Blue |

459 - 479 nm |

|

| |

Band 4 |

G |

Green |

545 - 565 nm |

|

| |

Band 1 |

R |

Red |

620 - 670 nm |

|

| |

Band 2 |

IVP |

Near Infrared |

841 - 875 nm |

|

| |

Band 5 |

SWIR1 |

Shortwave Infrared |

1230 - 1250 nm |

|

| |

Band 6 |

SWIR2 |

Shortwave Infrared |

1628 - 1652 nm |

|

| |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).