1. Introduction

Atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO

2) levels have been converted into an important topic for the scientific community, due to its great contribution to global warming. The levels of CO

2 in the atmosphere have increased significantly in recent decades due to human activities such as burning fossil fuels, deforestation, and industrialization. The average ambient concentration of CO

2 (in fresh air) has rapidly increased and recently fluctuates around 410 ppm [

1]. This increase at atmospheric CO

2 concentration, not only has implications in atmospheric and climatic topics but also on biological systems. CO

2 is the major by-product of cellular metabolism and constitutes the main physiological pH buffer system in eukaryotes. Also, it is necessary for the growth of many microorganisms [

2,

3].

The effects of CO

2 on cell metabolism have been little investigated. Moreover, it has been seen that both, endogenous and exogenous CO

2, alters the kinetics of growth of enteropathogenic

Escherichia coli EPEC and bicarbonate enhance the activity in vitro of kanamycin and gentamicin on EPEC [

4]. While atmospheric CO

2 concentrations are increasing rapidly, these are still low, compared to plasma CO

2 concentrations (50,000 ppm or 5%) [

5]. However, previous studies have shown that an increase in atmospheric concentration of CO

2 (1-10%) affects biochemical reactions at cellular level, that lead to an increase in intracellular oxidative stress in human neutrophils [

6], lung inflammation in mouses [

7] and an increased virulence of different bacterial pathogens [

8,

9].

Oxidative stress is caused by exposure to reactive oxygen species (ROS) as superoxide anion (O

2•-), hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) and hydroxyl radical (HO

•). ROS can be harmful to biomolecules and causes oxidative damage implicated in various pathologies (neurodegenerative diseases, atherosclerosis, cancer, and other disorders). However, they play a crucial role in homeostasis, cellular signaling, regulation of metabolism, or memory formation through DNA methylation [

10]. Currently, a mechanism is proposed in which alteration of the bacterial membrane triggers envelope stress and subsequent disruption of the anaerobic response regulator system, accelerating cellular respiration [

11]. Hyperactivation of the electron transport chain induces the formation of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide, damaging iron-sulfur groups, thereby releasing ferrous iron. This iron can then react with hydrogen peroxide in the Fenton reaction, generating hydroxyl radicals that can directly damage DNA, lipids, and proteins or oxidize the pool of deoxynucleotides, indirectly damaging DNA. However, this theory has recently become the subject of much debate [

12,

13].

Up to 1-2% of the oxygen consumed by a cell can be converted into oxygen radicals, which can lead to ROS production. The main source of ROS in vivo is aerobic respiration. However, ROS are also produced by peroxisomal β-oxidation of fatty acids, microsomal cytochrome P450, xenobiotic compound metabolism, stimulation of phagocytosis by pathogens or lipopolysaccharides, arginine metabolism, and tissue-specific cellular enzymes [

14,

15]. To counteract oxidative stress, cells are able to identify ROS production and transduce signals to increase their enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants defenses, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and reduced glutathione (GSH) [

16,

17]. The generation of intracellular ROS and their local redox state are important for understanding cellular pathophysiology. Some subcellular compartments are more oxidizing (such as the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), lysosomes, or peroxisomes), while others are more reducing (mitochondria, nuclei). Therefore, ROS levels can fluctuate between subcellular compartments and can lead to beneficial effects or pathology [

18]. The superoxide anion and its derivatives, hydrogen peroxide, and the hydroxyl radical, are the main active oxygen-containing chemical species. Although ROS are essential for some cellular processes such as transcription factor activation, gene expression, and protein phosphorylation, their uncontrolled production leads to indiscriminate oxidative attack on the inflammatory response, proteins, lipids, cell death, and organ damage [

19,

20].

The ROS are regularly generated, endogenously, by the respiratory chain at aerobic metabolism of organisms, but also by different exogenous factors, such as exposure to radiation, light, metals, and antibiotics [

21], affecting bacterial genera with different kinds of oxidative metabolism [

22]. This may be of key importance as bacteria leave the relatively low CO

2 levels of the external atmosphere for the higher CO

2 levels found inside most multicellular host organisms. Bacteria may uprear-late virulence factors at host physiologic CO

2 levels (as opposed to atmospheric CO

2 levels) in order to facilitate colonization or infection. examples of these pathways in a selected number of pathogens are given below [

23].

In the last years, some antibiotics have been described as stimulators of oxidative stress, including ciprofloxacin (CIP), which are known by interfering with replication and transcription of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) through the inhibition of DNA gyrase/topoisomerase II and topoisomerase IV [

24]. But nevertheless, this is not the only action mechanism since it had been proved that CIP can induce ROS formation as a cause for the increased O

2•- in

Staphylococcus aureus,

E. coli and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa. It was found that CIP generates ROS increase in susceptible strains of

S. aureus, carrying a state of oxidative stress, while resistant strains do not suffer an increment of ROS [

22,

25,

26].

The aim of this work was to understand if the high CO2 atmospheric concentrations can generate a modification to the oxidative damage generated in the action of CIP in E. coli, to evaluate their possible implications in human health.

2. Materials and Methods

Chemicals and reagents. Luria Bertani (LB) media (MP, USA). Nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT), 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2-DCFDA) and N-(1-naphthyl) ethylenediamine dihydrochloride were all obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Sulfanilamide was obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). CIP was obtained from Todo Droga (Córdoba, Argentina).

Experimental conditions in CO2. Carbon dioxide was purchased commercially by the Indura group AIR PRODUCTS gases company in Buenos Aires, in proportions 50 ppm CO2, 20% O2, balance (BLCE) N2 8 m3; y 50.000 ppm CO2, 20% O2, BLCE N2 8 m3.

CO2 incubation equipment. To carry out the experiments in the presence of CO

2, it was necessary to modify an orbital or reciprocal shaker for culture (Shaker, FERCA), making holes in the upper part of the equipment to allow the entrance of Teflon hoses, which were attached to sterile plastic pipettes (1 mL) and supplied the CO

2 to the culture medium. (

Figure S1, supplementary materials).

Death curves in controlled atmospheres of CO2. This assay was performed by a total incubation time of 8 h.

E. coli ATCC 25922 was cultivated aerobically in LB broth with stirring at 140 rpm for 18 h at 37 °C. Then, the bacterial cells were exposed to different CO

2 concentrations (50 and 50,000 ppm) and AC, in presence of different concentrations of CIP (0, 0.5, 50 µg/mL). Serial dilutions of bacterial suspensions were prepared in phosphate buffer (PBS) 0.05 M, pH 7.2 and plated in LB agar. After 18 h of incubation at 37 °C, there were counted the colony-forming units (CFU) and compared with the initial inoculum. The results were expressed as CFU/mL [

27,

28].

Determination of ROS. The kinetics of ROS generation in

E. coli ATCC 25922 treated with CIP was quantified by spectrofluorometry until 3 h of incubation, using H

2-DCFDA as fluorescent probe (480 nm and 520 nm were used as excitation and emission wavelength, respectively) [

29]. The bacterial cells were exposed to different CO

2 concentrations (50 and 50,000 ppm) and AC, in presence of different concentrations of CIP (0, 0.5 and 50 µg/mL). Then, 20 μl of H

2-DCFDA 20 µM aqueous solution were added. The fluorescence intensity was measured 30 min later with a spectrofluorometer Biotek Synergy HT. These results were expressed as arbitrary fluorescence units (a.u) by CFU/mL [

30]. Non-treated bacterial suspensions were used as the control. The experiments were carried out in triplicate.

Quantification of reactive nitrogen species (RNS). RNS is rapidly converted to nitrite in aqueous solutions and, therefore, the total nitrite can be used as an indicator of nitric oxide (NO) concentration. The generation of nitric oxide was quantified using the Griess reaction according to the methodology described by Guevara

et al. where N-(1-Naphthyl)ethylenediamine and sulfanilamide are used to form a diazonium salt, which is then measured spectrophotometrically [

31,

32] in

E. coli ATCC 25922, by a total time of 3 h. 100 µL of bacterial suspension was incubated with CIP at the CO

2 conditions, previously described and was mixed with 50 μL of 2% sulfanilamide in 5% (v/v) HCl and 50 μL of 0.1% N-(1-naphthyl)ethylenediamine dihydrochloride aqueous solution. The formation of the azo dye was measured 15 min. later by spectrophotometry at 543 nm. The absorbance was directly proportional to the nitrite content of the standard solution. These results were expressed as µM of sodium nitrate per mg of protein (µM NaNO

2/mg of protein).

Ferric reducing assay potency (FRAP). E. coli ATCC 25922 (50 µL) suspension was incubated with 150 µL of a mixture of 3.1 mg/mL 2,4,6-tripyridyl-1,3,5-triazine (TPTZ) in 40 mM HCl, 5.4 mg/mL FeCl

3.6H

2O and 300 mM acetate buffer (pH 3.6). Absorbance was read at 593 nm, at three different times, taking samples at 0, 2 and 4 h. The results were expressed as µM of Fe

2+ per mg protein [

33].

Superoxide dismutase activity. Basal production of the SOD enzyme in

E. coli ATCC 25922 was investigated by a total time of 4 h, taking samples at 0, 2 and 4 h of incubation. An overnight culture of

E. coli was prepared in LB media. 1 mL of bacterial suspension (OD

600=1) was incubated with CIP (0.5 and 50 µg/mL) and without CIP under atmospheric conditions and AC of CO

2 (50 and 50,000 ppm) in 25 mL of LB broth at 37 °C for each condition. The reaction was followed during 4h, taking a sample at each hour. Samples were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 min and the supernatant (extracellular SOD) was removed. Pellet was resuspended in 0.5 mL of PBS (intracellular SOD). The reaction mixture was obtained by incubating 100 µL of the intracellular or extracellular fraction, 100 µL of 75 µM NBT in DMSO, 300 µL of 13 mM methionine, 300 µL of 100 nM EDTA, 300 µL of 2 M riboflavin in 50 mM PBS pH 7.8. Subsequently, the samples were exposed to 20 W fluorescent lights for 6 min to trigger the reaction. The final color obtained was performed spectrophotometrically at 560 nm. These assays were realized for a total time of 4 h, taking samples at three incubation times of 0, 2 and 4 h and the results were expressed as SOD units and it was relative to mg of protein (USOD/mg of protein) [

34,

35].

Catalase determination. CAT activity in

E. coli was determined by a spectrophotometric method, using potassium dichromate in acidic solution. An overnight culture of

E. coli was prepared in LB media. 1 mL of the bacterial suspension (OD

600=1) was incubated with CIP (0.5 and 50 µg/mL) and without CIP under atmospheric conditions and controlled atmospheres of CO

2 (50 and 50,000 ppm) in 25 mL of LB broth at 37 °C for each condition. The reaction was followed during 4 hours, taking a sample at each hour of incubation. 2 mL of 0.2 M H

2O

2 solution and 2.5 mL of PBS pH 7 were added to 1 mL of each sample. From these new mixtures, 1 mL was taken from each one and 2 mL of reagent (2% potassium dichromate in glacial acetic acid) were added. They were incubated at 100 °C for 2 min and then cooled in an ice bath. Then, the absorbance was determined at 570 nm. The results were expressed as UCAT per mg protein. A UCAT unfolds 1 μM H

2O

2 per min at 25 °C to pH 7 [

33,

34].

Assay of GSH. The Ellman reagent (5,5-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid) was used to form a colored compound in presence of GSH, which is read spectrophotometrically at 412 nm. These assays were realized for a total time of 4 h, taking samples at three incubation times of 0, 2 and 4 h. An overnight culture of

E. coli ATCC 25922 in LB broth was prepared. 1 mL of the bacterial suspension (OD

600=1) was incubated with CIP (0.5 and 50 µg/mL) and without CIP for 4 h under atmospheric conditions and controlled atmospheres of CO

2 (50 and 50,000 ppm) in 25 mL of LB broth for each condition. Then, 100 μL of each sample were incubated at room temperature with 20 µL of glutathione reductase (6 U/mL), 50 µL of NADPH (4 mg/mL) and 20 µL of 5,5-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB) 1.5 mg/mL. Results were expressed as mM of GSH per mg protein [

35,

36].

Statistical analysis. Data were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments carried out under identical conditions. They were subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and subsequent Bonferroni test, using Graph Pad Prism 8 statistical software. The confidence limit used was 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Death Curves in Controlled Atmospheres of CO2

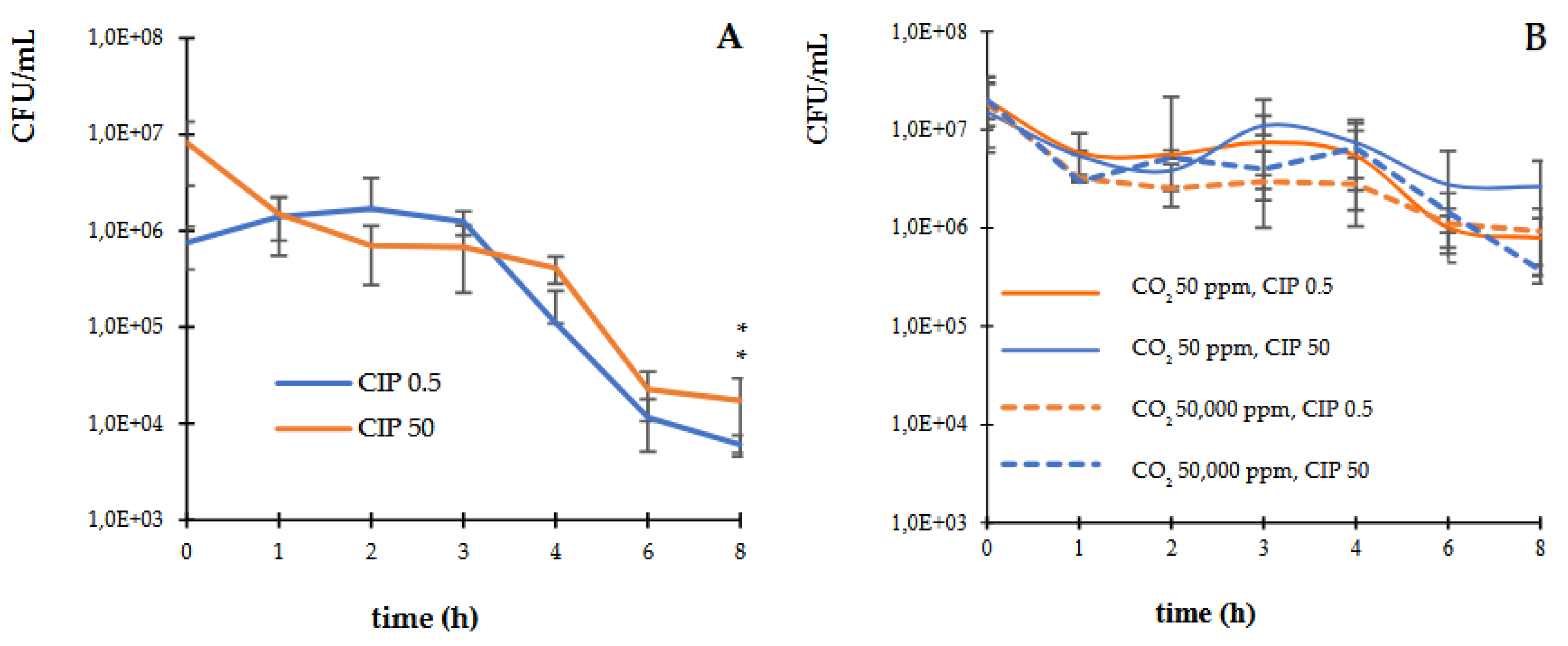

The kinetics of bactericidal activity of CIP into different CO

2 concentrations (50 and 50,000 ppm) on

E. coli ATCC 25922 was examined. The study revealed that CIP at the MIC (0.5 µg/mL) and supra-MIC (50 µg/mL) exerted a bactericidal activity, decreasing by three orders of magnitude the UFC/mL, within 6 h of exposure against

E. coli strain (

Figure 1A). Whereas, in presence of CO

2, the bactericidal effect of CIP was not observed before 8 h of incubation (

Figure 1B).

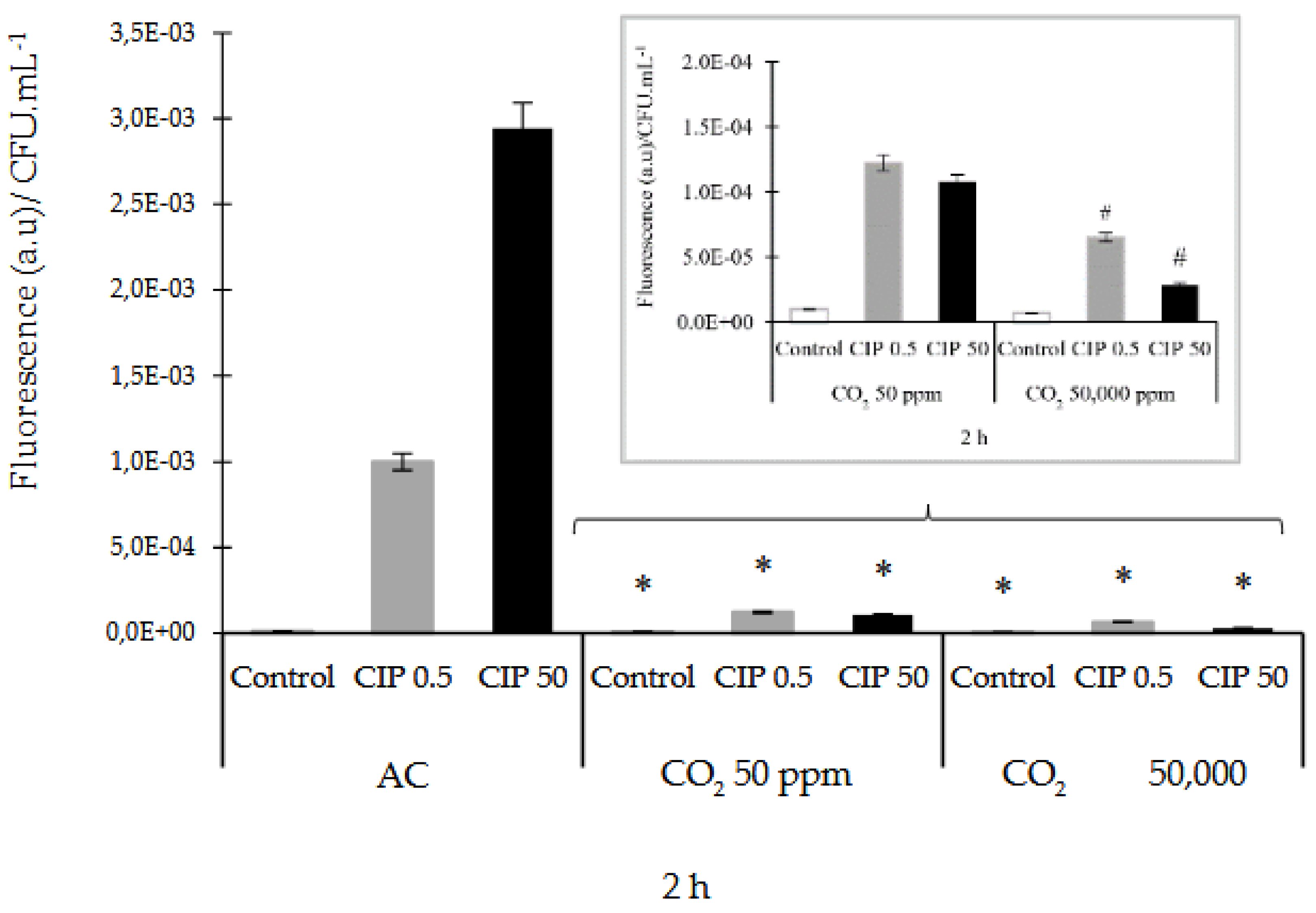

3.2. Determination of ROS and RNS

The ROS production in

E. coli after exposure to CIP was measured using the H

2-DCFDA method. ROS were produced within the first 2 h after the CIP treatment, both in AC and controlled CO

2 concentrations. It was observed that, at AC and CIP presence, the O

2•¯ was the most expressed species at this time. Simultaneously, it was observed a low participation of NO. When the studies were made in the presence of CO

2 and CIP, the HO

• and NO compounds increased their activity (See supplementary materials

Figures S1–S6). For this reason, the results were analyzed at that time. Two CIP concentrations studied in AC enhanced the formation of ROS, while CIP under CO

2 conditions decreased the formation of ROS relative to AC, significantly (

p˂0.05). These ROS decreasing were (6.06 ± 0.10) x10

-5 and (3.00 ± 0.15) x10

-5 (a.u)/CFU.mL

-1, which is equivalent to 93 and 99% with CIP 0.5 and 50 μg/mL, respectively, compared to AC (

Figure 3A). A significant (

p<0.05) decrease in ROS dose dependent on the concentration of CIP and CO

2 was also observed. (

Figure 3A, close up).

As is shown in

Table 1, in AC, CIP does not induce an increment of RNS formation related to its control. However, at 50 ppm of CO

2 and CIP presence, make that RNS formed were greater than AC. A significant increase, compared to its control (

p<0.05) and AC control (

p<0.05), was observed; these increases were approximately 84.985±0.011 and 81.921±0.003 µM NaNO

2/mg of protein for CIP 0.5 and 50 µg/mL, respectively, compared to AC. While at 50,000 ppm of CO

2, only this concentration rises the RNS formation and CIP has no synergic effect as a 50 ppm of CO

2 conditions.

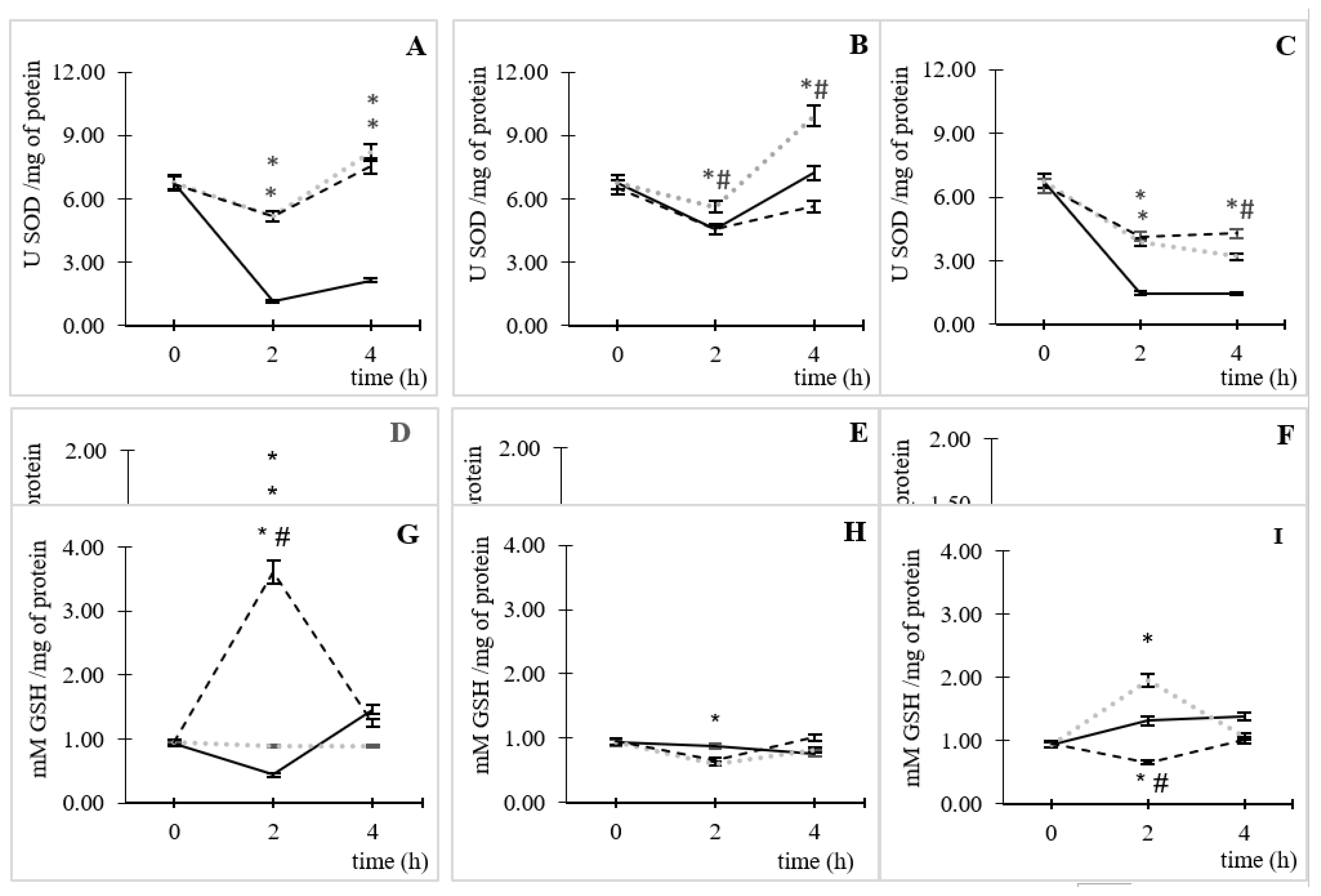

3.3. Enzymatic and Non-Enzymatic Antioxidant Activity

Under AC and without CIP, an increase of enzymatic (

Figure 4A and B) and non-enzymatic antioxidant systems (

Figure 4G) could be observed. The

Figure 4A showed the SOD obtained results at AC and, it could observe that in the lack of CIP (control) there was by enzyme consumption until 2 h of incubation and, from this point, remained relatively constant over time. In the presence of CIP, this effect was inverted; it found an increasing tendency in the enzyme activation from 2 h of incubation for both CIP concentrations (5.17 ± 0.06 U SOD /mg of protein), which it was similar to SOD activation lifting for four times higher than the basal condition (p˂0.05). Later, at 4 h of incubation, it was observed a SOD activation tendency in both CIP concentrations different to basal (p˂0.05).

A similar effect was observed at high CO

2 concentrations (

Figure 4C). Nevertheless, the SOD enzyme activity decreased, over time, in CIP presence (p<0.05). At low CO

2 concentrations (

Figure 4B), there was a reduction of the enzymatic activity, until incubation time of 2 h in the three studied variables. This reduction was very similar to the control conditions without and 50 µg/mL of CIP; then recovery of the activity of the enzyme was observed at 4 h of incubation, which it was significantly different to control conditions only for 0.5 µg/mL of CIP (p˂0.05).

Regarding the enzyme activity of CAT at AC (

Figure 4D), it was observed an enzyme activation of 1.5 ± 0.04 and 1.4 ± 0.02 U CAT /mg of protein respect to the control; equivalent to an activation, at 2 h of incubation, of 143 and 139% for 0.5 and 50 µg/mL of CIP, respectively (p˂0.05). This time coincided with the highest time for ROS formation.

In controlled CO

2 atmospheres, the enzyme activity happened only at 50 ppm and 50 µg/mL of CO

2 and CIP, respectively, at the maximum time of ROS stimulation (

Figure 4E); with an activation of 1.3 ± 0.02 UCAT/mg of protein, where this value corresponds to 10% respect to the control (p˂0.05). While for 50,000 ppm of CO

2, a reduction of enzymatic activity was observed throughout the time of the assay (

Figure 4F). It should be noted that at 4 h of incubation, in all cases, a gradual reduction of the enzymatic activity was observed, which was more marked at high CO

2 concentrations (

Figure 4F, p<0.05).

The GSH antioxidant capacity was different for all the tested conditions. In AC (

Figure 4G), a significant increase in GSH was observed, respect to the control (p<0.05), for 50 µg/mL of CIP at the time of the greatest ROS formation (2 h); while for the lowest CIP concentration, there is no significant change in the time of assay. At 50 ppm of CO

2 (

Figure 4H), it was observed that, at 2 h of incubation, the GSH was consumed (0.13 ± 0.03 mM GSH/mg of protein) in

E. coli by CIP action at a concentration of 50 µg/mL respect to the control without CIP (p<0.05).

Different behaviors were favored at high concentrations of CO

2 (

Figure 4I) by the CIP concentrations. At 0.5 µg/mL of CIP was observed, respect to the control without CIP, an increase of GSH (1.95 ± 0.04 mM GSH/mg of protein) at the 2 h of incubation (p<0.05). whereas that, at 50 µg/mL of CIP was observed a consumption (0.66 ± 0.02 mM GSH/mg of protein) at 2 h, respect to the control (p<0.05). Also, at the 4 h of incubation, there was a gradual reduction in the GSH activity at the AC and CO

2 50 ppm conditions. However, at CO

2 50,000 ppm conditions were observed that the high CIP concentrations enhance the GSH activity while a low CIP concentration (0.5 µg/mL) presented the opposite behavior.

In CO2 conditions, SOD and CAT activation were much lower than in AC. This can be attributed to the diminution of ROS formation due to CIP interaction with CO2, which led to less activation of antioxidant defenses to neutralize these species. Nevertheless, GSH was the specie that had the most significant increase in the presence of CO2; this behavior had a dependence to CIP and CO2 concentration.

At 50 ppm of CO2, the increase in GSH formation was 121% for 0.5 µg/mL of CIP respect to the AC; while at 50 µg/mL of CIP had an opposite behavior (82% consumption). At 50,000 ppm of CO2, both CIP concentration leads to GSH consumption respect to AC (32 and 96% for 0.5 and 50 µg/mL of CIP, respectively). This behavior could be related to the diminution of ROS formation observed in CO2 presence.

The FRAP in

E. coli was studied at a maximum time of 2 h (maximum stimulus of ROS); the results are shown in

Table 2 where it can see as, in AC, there a market decreased of FRAP as a consequence of CIP presence (

Table 2, first column). However, that behavior was modified by CO

2, where only its presence induces a high decrease of FRAP. At CO

2 50 ppm, this specie generated a similar behavior of CIP in this assay (

Table 2, first file) while, at CO

2 50,000 ppm, the decrease is not so market but let see the effect of CIP; the presence of this ATB contributes to stimulate the antioxidant capacity to until reaching the same values as those of AC.

4. Discussion

The bactericidal activity of CIP against E. coli was not evident in the presence of CO2 until after 8 h of incubation. These results are opposite to the results showed by Farha et al., where they studied the bicarbonate (HCO3¯) effect as an enhancer of CIP activity on E. coli and probe that, the HCO3- buffer system is effective in favoring its antimicrobial activity (37), indicating that the equilibrium of the buffer system was perturbed in an inverse way. Previous reports showed that pH variation can generate an increase or decrease (at high pHs and low pHs, respectively) of the CIP bactericidal activity (38-40). This, could be related to the protonated/unprotonated CIP structure (41,42) since it is known that the chemical environment generated by ionic carboxylic acid and carbonyl groups in the positions 3 and 4 (Figure 2) in CIP, respectively, is necessary to form strong hydrogen bonds with DNA and/or to coordinate to Mg (II) cation, therefore are essential to antibacterial activity (43).

It is known that CIP induces the accumulation of oxygen species inside bacterial cells as a secondary mechanism of action (44).

Nevertheless, when we studied the HO•, O2•¯ and NO formation pathways, by the use of scavengers like 2,2′-bipyridyl, Tyron and carboxy-PTIO, respectively, these make it possible to identify the radical species, which may be affected by CO2 participation, through a decrease in the ROS or RNS formation (depending on the species being studied) product of the reaction with the scavenger and comparing it with the AC (45).

The results obtained in AC are in agreement with previously published articles, where it showed that, at short times, ROS formation were induced by CIP in Proteus mirabilis and S. aureus. Besides, these results confirm that ROS participation are involved, not only in the toxicity but also in the action mechanism of CIP (33,46); at the same time, Masadeh et al. observed the same behavior in different reference strain (47), however, no one of these studies have been evaluated in CO2 modified atmosphere.

A possible explanation for the diminution of ROS formation, generated by CIP in CO2 presence, could be the RNS formation. These alterations in the RNS formation, in presence of CO2 and CIP, could favor the NO cytoprotective behavior described by Wink and Mitchell, which indicates that NO can neutralize ROS and, in turn, critically alter biomolecules such as enzymes and DNA, depending on both, NO concentrations and the organism under study (48,49). Additionally, Salgo et al. determined that in NO concentrations range of 0.05 and 8 mM favor the ONOO- formation, which could generate the damage in biomolecules mentioned before. Added to this investigation, Salgo et al. determined that in a range of NO concentrations between 0.05 and 8 mM, favor the ONOO•¯ formation which could cause DNA lesions and induce cellular die (50). Nevertheless, the highest NO concentrations obtained in this work were of 85 µM, which were not so high to cause DNA damage and cell death.

These results indicate that CO2 compound exerts changes in the activation of antioxidant defense systems since, in AC, an activation of all antioxidant defenses was found at the time of maximum ROS stimulation. This behavior is similar to that reported by other authors, where they evaluated the CIP capacity to induce the ROS formation through these defenses (GSH, ascorbic acid, SOD and CAT) on E. coli (44). This behavior has also been described for other bacterial genera such as P. aeruginosa, Proteus mirabilis and S. aureus (26,27,45). Goswami et al. showed that GSH reduced the CIP antibacterial effect, counteracting the oxidative stress associated and promoting its exit from the cell (46). This behavior had been reported by other authors, not only in E. coli (46) but also in different bacterial species (26,27,45).

CIP capacity to form ROS was reduced by CO2 against E. coli; therefore, the low concentrations of this reactive species could get neutralized by RNS or GSH and, it is possible that this behavior induces the diminution observed in CIP action on the death curve.

5. Conclusions

The toxicity of CO2 has been investigated for almost a century and its exposure essentially alters the acid/base balance and cellular metabolism. The role of long-term exposure to CO2 has to be studied because it has been proven that this compound, in addition to H2O2 can be responsible for mutagenesis in bacteria (28). According to the results obtained in this work, exogenous CO2 has to be taking into account to evaluate its role in the oxidative stress generation by antibiotics like CIP. In summary, looking at our findings, we can say that the participation of CO2 in oxidative stress, mediated by CIP in bacterial cells, has implications not only in the environment but also in human health.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/doi/s1, Figure S1: Scheme of the experimental setup equipment for the incubation of

E. coli; Figure S2; Tyron effect as ROS scavenger (A); Figure S3: Tyron effect as ROS scavenger (B); Figure S4: 2,2′-bipyridyl effect as ROS scavenger (A); Figure S5: 2,2′-bipyridyl effect as ROS scavenger (B); Figure S6: CPTIO effect as RNI scavenger; Figure S7: Tyron effect as RNI scavenger.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Viviana Cano Aristizábal and Paulina Páez; Data curation, Viviana Cano Aristizábal, Elia Mendoza Ocampo and Melisa Quinteros; Formal analysis, Viviana Cano Aristizábal, Elia Mendoza Ocampo and Paulina Páez; Funding acquisition, Paulina Páez; Investigation, Elia Mendoza Ocampo and Paulina Páez; Methodology, Viviana Cano Aristizábal and Melisa Quinteros; Project administration, Paulina Páez; Resources, Paulina Páez; Supervision, Paulina Páez; Visualization, Viviana Cano Aristizábal, Elia Mendoza Ocampo, Melisa Quinteros and Paulina Páez; Writing – original draft, Viviana Cano Aristizábal and Paulina Páez; Writing – review & editing, Elia Mendoza Ocampo, María Paraje and Paulina Páez.

Funding

This research was funded by ANPCyT PICT 2021-00062 and SeCyT UNC.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AC |

Atmospheric Conditions |

| a.u |

arbitrary fluorescence units |

| CAT |

Catalase |

| CFU |

Colony Forming Units |

| CIP |

Ciprofloxacin |

| CO2

|

Carbon dioxide |

| DNA |

deoxyribonucleic acid |

| FRAP |

Ferric Reducing Assay Potency |

| GSH |

Reduced glutathione |

| HO•

|

Hydroxyl radical |

| H2O2

|

Hydrogen peroxide |

| H2-DCFDA |

2′,7′-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate |

| LB |

Luria Bertani |

| NBT |

NitroBlue Tetrazolium |

| HCO3¯

|

Bicarbonate |

| NO |

Nitric Oxide |

| OD |

Optical Density |

| PBS |

Phosphate Buffer Saline |

| ROS |

Reactive Oxygen Species |

| O2•-

|

Superoxide Anion |

| RNS |

Reactive Nitrogen Species |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| SOD |

Superoxide Dismutase |

| U |

Unit |

References

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO). GREENHOUSE GAS BULLETIN. The State Greenhouse in the Atmosphere Based on Global Observations through 2016. 12 November 2018. Available online: https://library.wmo.int/doc_num.php?explnum_id=4022.

- Butler, J.H.; Montzka, S.A. The NOAA annual greenhouse gas index (AGGI). 12 November 2018. Available online: https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/aggi/aggi.html.

- Walker, H.H. Carbon dioxide as a factor affecting lag in bacterial growth. Science 1932, 76, 602–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezraty, B.; Chabalier, M.; Ducret, A.; Maisonneuve, E.; Dukan, S. CO2 exacerbates oxygen toxicity. EMBO Reports 2011, 12, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, H.; Buhse, T.; Rivera, M.; Parmananda, P.; Ayala, G.; Sánchez, J. Endogenous CO2 may inhibit bacterial growth and induce virulence gene expression in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Microb Pathog 2012, 53, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummins, E.P.; Selfridge, A.C.; Sporn, P.H.; Sznajder, J.I.; Taylor, C.T. Carbon dioxide-sensing in organisms and its implications for human disease. Cell. Mol. Life Sci 2014, 71, 831–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coakley, R.J.; Taggart, C.; Greene, C.; McElvaney, N.G.; O’Neill, S.J. Ambient pCO2 modulates intracellular pH, intracellular oxidant generation, and interleukin-8 secretion in human neutrophils. J. Leukoc. Biol 2002, 71, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolhassani, M.; Guais, A.; Chaumet-Riffaud, P.; Sasco, A.J.; Schwartz, L. Carbon dioxide inhalation causes pulmonary inflammation. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol 2009, 296, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsten, V.; Murray, S.R.; Pike, J.; Troy, K.; Ittensohn, M.; Kondradzhyan, M.K.; et al. msbB deletion confers acute sensitivity to CO2 in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium that can be suppressed by a loss-of-function mutation in zwf. BMC Microbiol 2009, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visca, P.; Fabozzi, G.; Milani, M.; Bolognesi, M.; Ascenzi, P. Nitric oxide and Mycobacterium leprae pathogenicity. IUBMB Life 2002, 54, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storz, G.; Imlay, J.A. Curr Opin Microbiol, 1999; 2, 188–194. [CrossRef]

- Imlay, J.A. Cellular defenses against superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. Annu Rev Biochem 2008, 77, 755–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochgrafe, F.; Wolf, C.; Fuchs, S.; Liebeke, M.; Lalk, M.; Engelmann, S.; et al. Nitric oxide stress induces different responses but mediates comparable protein thiol protection in Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus. J. bacteriol 2008, 190, 4997–5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overton, T.W.; Justino, M.C.; Li, Y.; Baptista, J.M.; Melo, A.M.P.; Cole, J.A.; et al. Widespread distribution in pathogenic bacteria of Di-Iron proteins that repair oxidative and nitrosative damage to Iron-Sulfur centers. J Bacteriol 2008, 190, 2004–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storz, G.; Zheng, M. Oxidative stress. In Bacterial Stress Responses; Storz, G., Hengge-Aronis, R., Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, 2000; pp. 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Albesa, I.; Becerra, M.C.; Battán, P.C.; Páez, P.L. Oxidative stress involved in the antibacterial action of different antibiotics. Biochem Bioph Res Commun 2004, 317, 605–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustaev, A.; Malik, M.; Zhao, X.; Kurepina, N.; Luan, G.; Oppegard, L.M.; et al. Fluoroquinolone-gyrase-DNA complexes TWO MODES OF DRUG BINDING. J. Biol. Chem 2014, 289, 12300–12312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becerra, M.C.; Sarmiento, M.; Páez, P.L.; Arguello, G.; Albesa, I. Light effect and reactive oxygen species in the action of ciprofloxacin on Staphylococcus aureus. J. Photochem. Photobiol B 2004, 76, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becerra, M.C.; Páez, P.L.; Larovere, L.E.; Albesa, I. Lipids and DNA oxidation in Staphylococcus aureus as a consequence of oxidative stress generated by ciprofloxacin. Mol Cell Biochem 2006, 285, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinteros, M.A.; Aiassa Martínez, I.M.; Paraje, M.G.; Dalmasso, P.R.; Páez, P.L. Silver nanoparticles: Biosynthesis using an ATCC reference strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and activity as broad spectrum clinical antibacterial agents. Int. J. Biomat 2016, 5971047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, S.R.; Miana, G.E.; Albesa, I.; Mazzieri, M.R.; Becerra, M.C. Evaluation of antibacterial activity and reactive species generation of n-benzenesulfonyl derivatives of heterocycles. Chem. Pharm. Bull 2016, 64, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhong, Z.; Xu, Z.; Chen, L.; Wang, Y. 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein as a fluorescent probe for reactive oxygen species measurement: Forty years of application and controversy. Free Radic. Res 2010, 44, 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinteros, M.A.; Cano Aristizábal, V.; Dalmasso, P.R.; Paraje, M.G.; Páez, P.L. Oxidative stress generation of silver nanoparticles in three bacterial genera and its relationship with the antimicrobial activity. Toxicology in Vitro 2016, 36, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, S.R.; Aiassa, V.; Becerra, M.C. Oxidative stress response in reference and clinical Staphylococcus aureus strains under Linezolid exposure. J Glob Antimicrob Re 2020, 22, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, M.A.; da Silva, M.A.; Ortega, M.G.; Cabrera, J.L.; Paraje, M.G. Usnic acid activity on oxidative and nitrosative stress of azole-resistant Candida albicans biofilm. Planta Med. 2017, 83, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Páez, P.L.; Becerra, M.C.; Albesa, I. Antioxidative mechanisms protect resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus against ciprofloxacin oxidative damage. Fundamental & clinical pharmacology 2009, 24, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiassa, V.; Barnes, A.I.; Albesa, I. Resistance to ciprofloxacin by enhancement of antioxidant defenses in biofilm and planktonic Proteus mirabilis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 393, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Páez, P.L.; Becerra, M.C.; Albesa, I. Chloramphenicol induced oxidative stress in Human neutrophils. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol 2008, 103, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Páez, P.L.; Becerra, M.C.; Albesa, I. Effect of the association of reduced glutathione and ciprofloxacin on the antimicrobial activity in Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2010, 303, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farha., M.A.; French, S.; Stokes, J.M.; Brown, E.D. Bicarbonate alters bacterial susceptibility to antibiotics by targeting the proton motive force. ACS Infect. Dis 2018, 4, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauernfeind, A.; Petermtiller, C. In Vitro activity of ciprofloxaein, norfloxacin and nalidixic acid. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol 1983, 2, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiler, H.J.; Grohe, K. The In Vitro and In Vivo activity of ciprofloxacin. In Ciprofloxacin; Neu, H.C., Reeves, D.S., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Hesse, Alemania, 1986; pp. 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Aagaard, J.; Gasser, T.; Rhodes, E.; Madsen, E.O. MICs of Ciprofloxacin and Trimethoprim for Escherichia coli: Influence of pH, lnoculum Size and Various Body Fluids. Infection 1991, 19, S167–S169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrell, J.H.; Montero, M.T. Calculating Microspecies Concentration of Zwitterion Amphoteric Compounds: Ciprofloxacin as Example. Journal of Chemical Education 1997, 74, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bel, E.; Dewulf, J.; De Witte, B.; Van Langenhove, H.; Janssen, C. Influence of pH on the sonolysis of ciprofloxacin: Biodegradability, ecotoxicity and antibiotic activity of its degradation products. Chemosphere 2009, 77, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitscher, L.A. , Z. Structure-activity relationships of quinolones. In Fluoroquinolone Antibiotics: Milestones in Drug Therapy; Ronald, A.R., Low, D.E., Eds.; Birkhäuser: Basel, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Páez, P.L.; Becerra, M.C.; Albesa, I. Comparison of macromolecular oxidation by reactive oxygen species in three bacterial genera exposed to different antibiotics. Cell Biochem Biophys 2011, 61, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinteros, M.A.; Cano Aristizabal, V.; Onnainty, R.; Mary, V.S.; Theumer, M.G.; Granero, G.E.; Paraje, M.G.; Páez, P.L. Biosynthesized silver nanoparticles: Decoding their mechanism of action in Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2018, 104, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiassa, V.; Barnes, A.I.; Albesa, I. Macromolecular oxidation in planktonic population and biofilms of Proteus mirabilis exposed to ciprofloxacin. Cell Biochem. Biophys 2014, 68, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masadeh, M.; Alzoubi, K.; Al-azzam, S.; Khabour, O.; Al-buhairan, A. Ciprofloxacin induced antibacterial activity is atteneuated by pretreatment with antioxidant agents. Pathogens 2016, 5, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wink, D.A.; Mitchell, J.B. Chemical biology of nitric oxide: Insights into regulatory, cytotoxic, and cytoprotective mechanisms of nitric oxide. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1998, 25, 434–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, P.A.; Anderson, V.E.; Edwards, J.O.; Gustafson, G.; Plumb, R.C.; Suggs, J.W. A stable solid that generates hydroxyl radical upon dissolution in aqueous solutions: Reaction with proteins and nucleic acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 5430–5432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgo, M.G.; Stone, K.; Squadrito, G.L.; Battista, J.R.; Pryor, W.A. Peroxynitrite causes DNA nicks in plasmid pBR322. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 210, 1025–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, M. , Mangoli, S.H.; Jawali, N. Involvement of reactive oxygen species in the action of ciprofloxacin against Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 949–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, M.C.; Albesa, I. Oxidative stress induced by ciprofloxacin in Staphylococcus aureus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 297, 1003–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, M.; Subramanian, M.; Kumar, R.; Jass, J.; Jawali, N. Involvement of antibiotic efflux machinery in Glutathione-mediated decreased ciprofloxacin activity in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 4369–4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyachenko, V.; Rueckschloss, U.; Isenberg, G. Modulation of cardiac mechanosensitive ion channels involves superoxide, nitric oxide and peroxynitrite. Cell Calcium 2009, 45, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcén, M.; Ruiz, V.; Serrano, M.J.; Condón, S.; Mañas, P. Oxidative stress in E. coli cells upon exposure to heat treatments. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 241, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Alencar, T.A.M.; Wilmart-Gonçalves, T.C.; Vidal, L.S.; Fortunato, R.S.; Leitão, A.C.; Lage, C. Bipyridine (2,2′-dipyridyl) potentiates Escherichia coli lethality induced by nitrogen mustard mechlorethamine. Mutat. Res. - Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2014, 765, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Q.; Zhang, B.; Li, J.; Zhang, B.; Wang, H.; Li, M. Endoplasmic reticulum-derived reactive oxygen species (ROS) is involved in toxicity of cell wall stress to Candida albicans. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 99, 572–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz-Tohid, V.; Taheri, P.; Taghavi, S.M.; Tarighi, S. The role of nitric oxide in basal and induced resistance in relation with hydrogen peroxide and antioxidant enzymes. J. Plant Physiol. 2016, 199, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galera, I.L.D.; Paraje, M.G.; Páez, P.L. Relationship between oxidative and nitrosative stress induced by gentamicin and ciprofloxacin in bacteria. J. Biol. Nat. 2016, 5, 122–130. [Google Scholar]

- Augusto, O.; Bonini, M.G.; Amanso, A.M.; Linares, E.; Santos, C.C.X.; De Menezes, S.L. Nitrogen dioxide and carbonate radical anion: Two emerging radicals in biology. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002, 32, 841–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, S.; Czapski, G. Formation of peroxynitrate from the reaction of peroxynitrite with CO2: Evidence for carbonate radical production. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1998, 120, 3458–3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonini, M.G.; Radi, R.; Ferrer-Sueta, G.; Ferreira, A.M.D.C.; Augusto, O. Direct EPR detection of the carbonate radical anion produced from peroxynitrite and carbon dioxide. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 10802–10806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwahara, H.; Miyamoto, Y.; Akaike, T.; Kubota, T.; Sawa, T.; Okamoto, S.; Maeda, H. Helicobacter pylori urease suppresses bactericidal activity of peroxynitrite via carbon dioxide production. Infect. Immun 2000, 68, 4378–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).