1. Introduction

Assessing the quality of care provided to patients remains a significant challenge in the healthcare sector due to the absence of a universally accepted definition of quality. In a broad sense, quality is often described in general terms, such as excellence, the absence of defects, or the achievement of established goals [

1]. This concept can be applied across various contexts and situations [

2]. However, in healthcare, several organizations have attempted to define quality more precisely. For instance, the Institute of Medicine defines quality of care as

"the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge” [

3].

Despite these definitions, there is no single, standardized, and objective scale for measuring quality in healthcare systems [

4]. Instead, various assessment tools designed for service quality evaluation have been adapted to measure healthcare performance. Quality in healthcare is typically assessed through multiple dimensions, including patient care and patient safety. However, defining standards and developing evaluation tools is not merely a technical exercise but a fundamental necessity to ensure that healthcare systems are equitable, efficient, and patient-centered. Without evaluation, improvement is impossible, and without improvement, healthcare systems risk becoming ineffective and inequitable.

This narrative review aims to comprehensively describe and analyze key aspects of quality in patient care, with a specific focus on service quality while excluding patient safety [

5]. The topics in this review follow a structured sequence, beginning with the definition of quality concepts and key elements, followed by an exploration of models, dimensions, improvement strategies, and certification processes.

2. Methodology

This comprehensive narrative literature review employed Scholar, PubMed, Cochrane Library, Scopus, Clarivate, and Clinical Key for academic searches, using keywords and topical research. Initially, broad terms like “quality of care” were used, but, later, they were refined to specific topics such as “quality healthcare improvement, quality models, and strategies of improvement”. Eligible articles included systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials (RCT), observational studies, literature reviews, and discussion articles. Only English language studies published between 2000 and 2024 were considered, with exceptions made for relevant older studies or when recent data were lacking. There were no geographical limitations, so as to ensure a global perspective on quality of care.

The presentation of the topics of this article were selected aiming to clarify conceptual terms, and develop the description of the models used in the clinical approach of quality of care evaluation.

Table 1.

Conceptual design of literature research.

Table 1.

Conceptual design of literature research.

| Search Items |

|---|

Initial terms

Quality of care

Quality healthcare

|

Topical research

Quality healthcare improvement, quality models, service quality, healthcare systems

|

AND

Strategies of improvement, certifications and accreditations |

Academic databases

Google Scholar, PubMed, Cochrane Library, Scopus, Clarivate, and Clinical Key |

Types of research

Systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials (RCT)*, observational studies, literature reviews, and discussion articles. |

Language

English |

Publication year limits

2000-2024 ** |

3. Key Elements of Quality of Care

To better understand how quality in healthcare is assessed, it is essential to consider its core components. According to widely accepted models, there are three key elements of quality of care: structure, process, and outcome [

2,

3,

6].

Structure refers to the physical and organizational infrastructure of healthcare delivery, including available technologies, personnel, financial resources, management systems, and team coordination. Process focuses on the interactions between patients and caregivers, encompassing the recognition of medical needs, clinical decision-making, and the delivery of interventions. Outcome measures the effects of care on a patient’s health, including clinical results, functional status, symptom relief, mobility, mortality rates, and patient satisfaction.

Although these three components are interrelated, it is important to recognize that structure and process heavily influence outcomes. However, this relationship is not always linear or guaranteed. For instance, high-quality infrastructure and advanced technologies do not necessarily translate into improved patient outcomes. Similarly, favorable health outcomes may not always reflect high-quality care if they result from conditions with favorable natural histories. Conversely, in some cases, no health improvement is observed despite the application of high-quality care practices [

2,

3,

6].

To address these complexities, some authors propose a fourth element known as balancing measures [

7,

8]. These are defined as the unintended consequences—either positive or negative—resulting from quality improvement efforts. For example, while an intervention may improve patient satisfaction, it might simultaneously increase staff workload or healthcare costs. Balancing measures help assess whether improvements in one domain compromise other important aspects of care, emphasizing the need for well-aligned and sustainable strategies [

7,

9].

A study conducted in the Netherlands exemplifies the importance of these interrelated elements. Researchers analyzed survey data from patients undergoing different procedures, including hip or knee replacement, cataract surgery, treatment for varicose veins, spinal disc herniation, and rheumatoid arthritis [

10]. They employed instruments such as the Dillman method, the U.S.-based Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS), and the Dutch Consumer Quality Index (CQ-index), both of which incorporate questions related to structure, process, and outcomes.

The study’s regression analysis revealed that process-related factors, particularly communication and shared decision-making, accounted for the largest proportion of variance in patients’ overall care ratings. Structural factors, including waiting times and care coordination, also played a significant role—especially in surgical patients. Interestingly, outcome-related experiences, such as improved physical functioning, had a relatively minor impact on the overall patient ratings.

These findings reinforce the notion that healthcare quality should not be evaluated based on a single element. Institutions striving for high-quality care must consider the dynamic interaction between structure, process, and outcome—and, when applicable, include balancing measures. Ultimately, achieving meaningful improvements requires tailored strategies aligned with the needs of the target population and a balanced approach that considers the trade-offs between different quality elements.

4. Quality Models and Dimensions in Healthcare Systems

Service quality in healthcare is composed of two main components: technical quality and functional quality [

11]. Technical quality focuses on the outcomes of care, while functional quality refers to the internal processes involved in delivering care [

11,

12]. Several quality models implemented in healthcare systems are designed to assess functional quality.

The World Health Organization (WHO) proposes that improvements in healthcare should be made across six dimensions: effectiveness, efficiency, accessibility, acceptability, equitability, and safety (

Table 2) [

13,

14,

15]. These are defined as follows: Effectiveness is the delivery of evidence-based care that improves health outcomes and addresses patient needs. Efficiency involves maximizing the use of resources and minimizing waste. Accessibility refers to the availability of care within a reasonable geographic distance, supported by adequate skills and resources. Acceptability means that care is aligned with the values, preferences, and cultures of individuals. Equitability ensures consistent quality of care regardless of gender, race, or ethnicity. Safety involves reducing risks and harm to patients [

13,

14,

15]. Each dimension contributes to a high-quality healthcare system that is effective, efficient, and responsive to diverse patient populations.

One model widely used in countries such as Turkey, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Romania is the service quality model (SERVQUAL model) [

16]. This model evaluates functional quality through five dimensions: (I) Tangibility – physical facilities, staff appearance, and equipment; (II) Reliability – accurate service delivery; (III) Responsibility – willingness to assist patients; (IV) Assurance – confidence and knowledge demonstrated by staff; and (V) Empathy – individualized attention (

Table 2). SERVQUAL model uses 44 questions, divided equally between expectations and perceptions [

16]. Despite its wide use, the model has limitations, including susceptibility to bias in small samples and challenges in translating the survey to other languages. In Iran, results showed dissatisfaction across all five dimensions, especially in responsibility and reliability. Tangibility and empathy showed the smallest gaps between patient expectations and perceptions [

16]. These findings suggest a misalignment between what patients expect and the care they perceive, which may stem from inadequate attention by staff or difficulties in adapting the survey language. To enhance functional quality, staff education should include regular feedback from supervisors. Additionally, hiring skilled translators for survey adaptation is recommended.

Another model used in healthcare evaluation is the Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) model [

17], originally developed for marketing. This model helps identify service aspects that require more focus or are over utilizing resources. In healthcare, it links the perceived importance of service features with actual performance [

17]. For instance, Kerman Medical Sciences University in Iran applied the IPA model to measure the quality of inpatient services in teaching hospitals [

18]. They assessed eight dimensions: tangibility, reliability, empathy, service delivery, social accountability (the institution’s duty to benefit society), service organization, responsiveness (the system’s capacity to adapt to patient needs), and assurance (

Table 2). Patients rated each dimension using a five-point Likert scale. The results were plotted on a four-quadrant matrix to visualize areas needing improvement. A significant gap was found between expectations and perceptions in nearly all dimensions. Assurance had the highest rating in perceptions, while social accountability was consistently rated the lowest in both expectations and perceptions [

18]. These findings suggest that although educational hospitals inspire patient confidence, they fall short in areas related to societal responsibility. Recommendations include assigning dedicated staff for patient education in smaller groups and reducing their clinical burden. Allocating separate personnel for patient care may also improve attention quality (

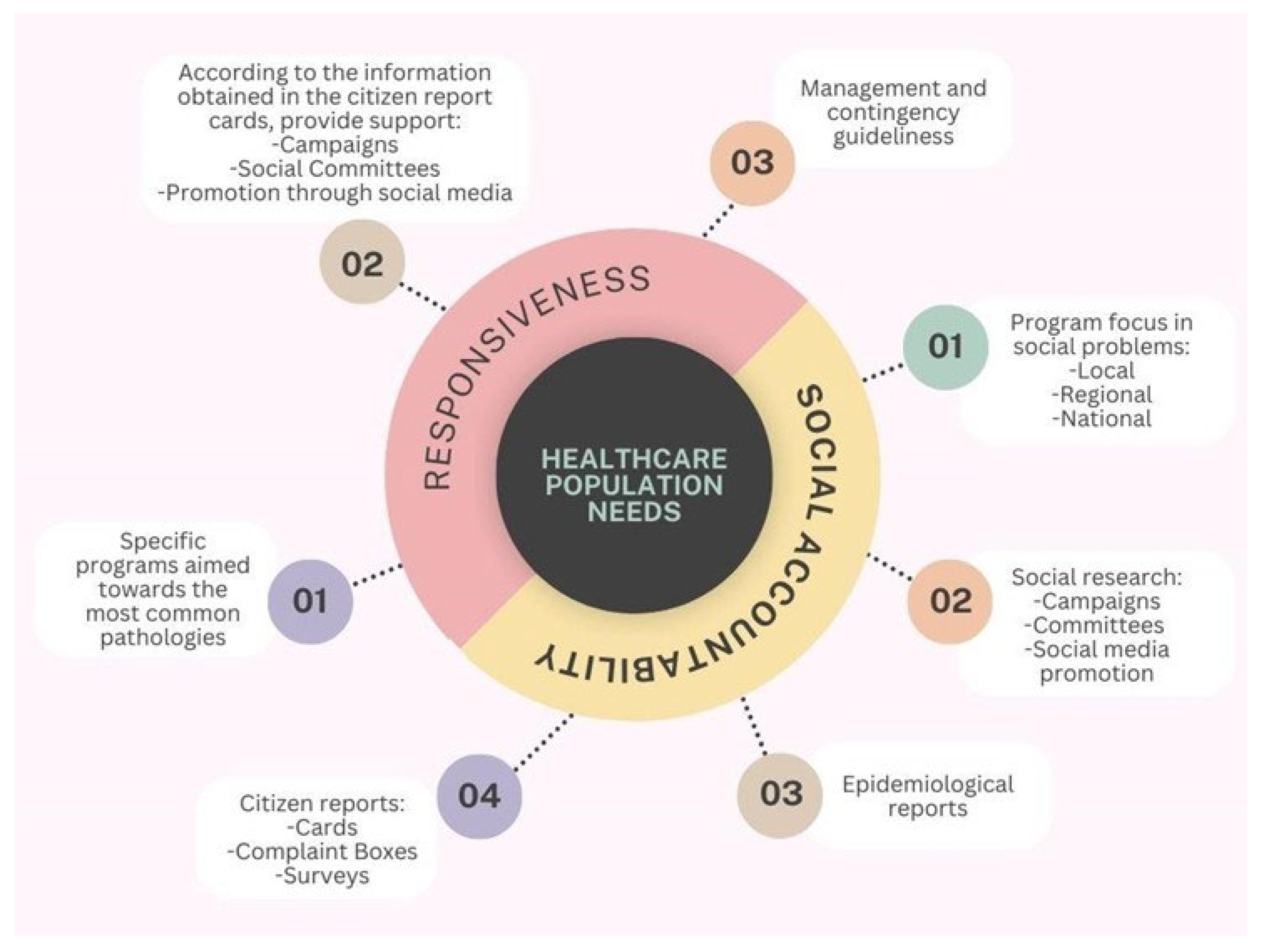

Figure 1).

This figure depicts a concentric conceptual model centered on the core element “Healthcare Population Needs”, which is surrounded by two interrelated dimensions: Responsiveness and Social Accountability. These components are represented as semicircular domains encircling the central concept, symbolizing their shared focus on improving health system alignment with community expectations and demands. From the Responsiveness domain, three key operational elements emerge: (1) the development of specific programs targeted at the most prevalent pathologies within the population; (2) the implementation of actions informed by citizen report cards, including public health campaigns, the involvement of social committees, and outreach through social media; and (3) the formulation of management protocols and contingency plans to address emerging needs and health crises. Conversely, the Social Accountability domain comprises four interconnected elements: (1) the design of programs focused on addressing social problems at local, regional, and national levels; (2) the use of social research methods—including campaigns, committee involvement, and media promotion—to understand public concerns; (3) the utilization of epidemiological data to guide planning; and (4) the integration of community feedback mechanisms, such as report cards, complaint boxes, and satisfaction surveys. The figure underscores the structural and functional linkage between these two dimensions and emphasizes their shared purpose in guiding healthcare systems to become more inclusive, responsive, and aligned with the evolving needs of the populations they serve.

Across these models and studies, patients consistently expect individualized attention and well-equipped, clean facilities. Improvement is needed in social accountability, responsibility (

Figure 1), and reliability—highlighting perceived shortcomings in staff availability, willingness to help, and consistency in service delivery. Among these, reliability stands out as a dimension closely linked to institutional infrastructure and workforce capacity. Addressing it can significantly enhance care quality (

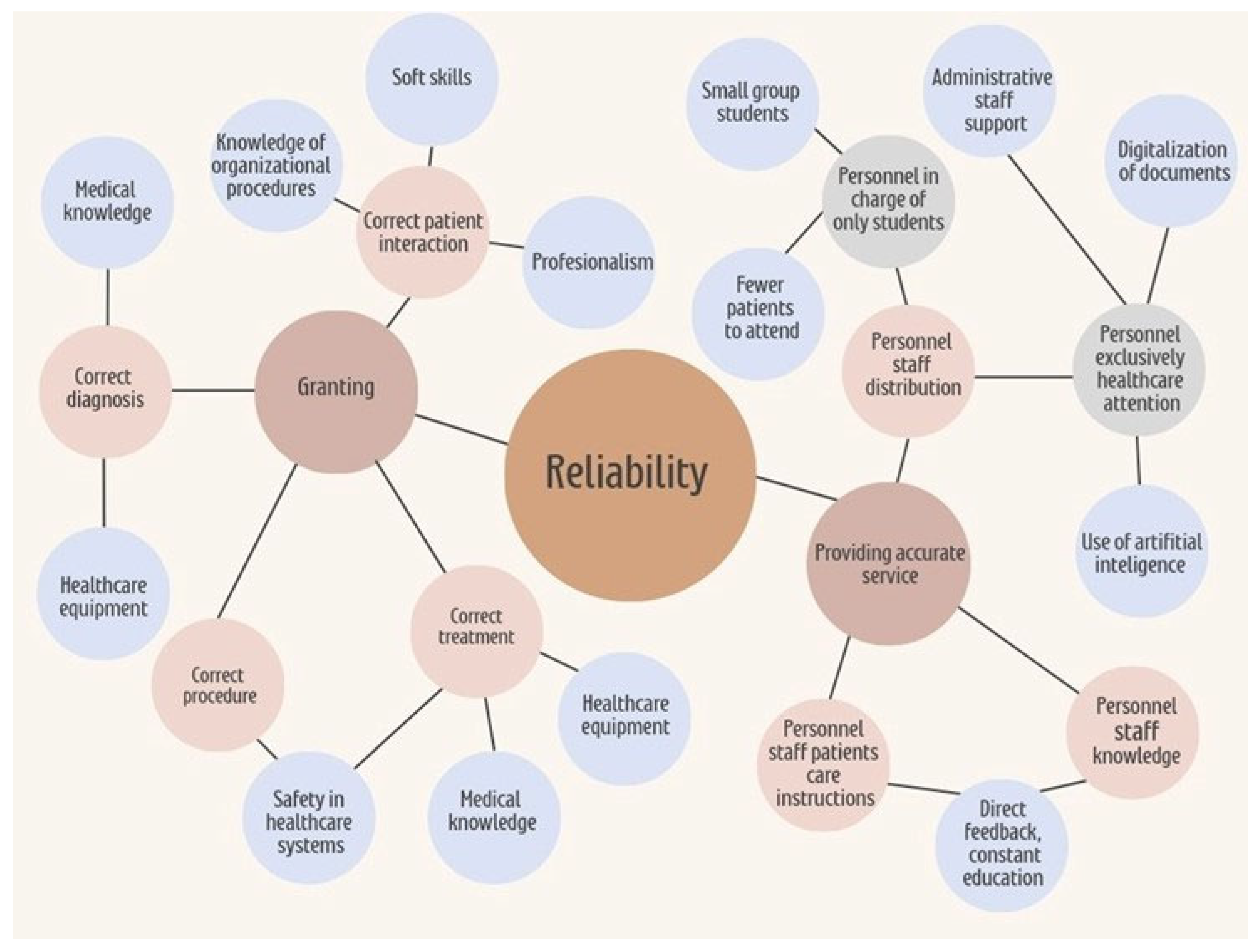

Figure 2).

This figure presents a hierarchical conceptual map outlining the key elements that contribute to reliability in healthcare service delivery. At the center of the model is the concept of reliability, which encompasses both institutional infrastructure and personnel-related factors. On the left side, the dimension of “Granting” is represented, including the provision of correct patient interaction, diagnosis, procedures, and treatment. These processes are supported by elements such as knowledge of organizational procedures, soft skills, professionalism, medical knowledge, healthcare equipment, and adherence to safety protocols. On the right side, the concept of “Providing Accurate Service” is detailed, emphasizing the distribution and organization of healthcare personnel. This includes the assignment of staff exclusively to student education—favoring smaller groups and reduced patient loads—as well as personnel focused solely on patient care, supported by administrative staff, document digitalization, and artificial intelligence tools. Additionally, the model highlights the importance of staff education, direct feedback mechanisms, and continuous professional development in ensuring service accuracy and reliability. Overall, the map illustrates the interdependent relationships among organizational resources and human factors that influence the consistent delivery of high-quality care. Institutions are responsible for investigating, identifying, and addressing deficits in social accountability and responsiveness, as part of their broader mission to promote health awareness and improve healthcare services.

5. Strategies to Improve Quality in Healthcare Systems

Improving quality in healthcare systems requires the implementation of effective Quality Improvement Strategies (QIS). According to Scott’s review “What are the most effective strategies for improving quality and safety of health care?”, several approaches have been categorized based on their relative effectiveness [

19]. The most impactful strategies include: I) Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSS), which provide healthcare professionals with knowledge and patient-specific information to enhance decision-making; II) Clinical Practice Guidelines, which offer systematically developed recommendations for specific clinical situations; III) Audit and Feedback mechanisms that compare current performance against standards to guide improvement; IV) Patient-Mediated Quality Improvement Strategies, which involve patients in their own care processes; Chronic Disease Management programs for long-term illness management; and Specialty Outreach Programs focused on enhancing care in specific clinical areas [

19].

5.1. Clinical Decision Support System and Clinical Practice Guidelines

Scott’s review of high-quality randomized trials identified key factors that contribute to the success of CDSS implementation. These include the integration of decision support at the time and location of clinical decision-making, automatic provision as part of the workflow, delivery of actionable recommendations rather than just evidence tables, and the use of computerized systems [

19].

Similarly, Clinical Practice Guidelines are more effective when tailored to local needs, supported by active educational interventions, and reinforced with patient-specific reminders [

19,

20,

21]. Although these strategies are often provided at a national or international level by organizations such as the World Health Organization, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Food and Drug Administration, they are most effective when implemented locally within healthcare institutions by internal consensus, adapting to contextual realities while still following global standards.

5.2. Audit and Feedback. Patient-Mediated Quality Improvement Strategies

Audit and feedback mechanisms have proven especially effective in enhancing test ordering and preventive measures, particularly when initial adherence to guidelines is low or when feedback is intensive and detailed [

22,

23,

24].

Patient-mediated quality improvement strategies are most successful when incorporating self-monitoring tools, patient self-management programs, motivational initiatives, and multifaceted interventions [

19]. These strategies are bidirectional, involving both healthcare professionals and patients. Their success largely depends on mutual receptiveness: healthcare professionals must be open to feedback and well-trained, while patients must be encouraged to adhere to treatments and report adverse effects. Feedback directed at healthcare professionals is typically guided by governmental agencies, while feedback to patients depends on the ability and training of healthcare staff [

24].

Overall, these strategies improve adherence, encourage transparency, and empower patients to participate actively in their care.

5.3. Chronic Disease Management and Specialty Outreach Programmes

Chronic disease management programs are designed to support patients in managing long-term illnesses, improving treatment adherence, alleviating symptoms, preventing disease progression, and enhancing quality of life [

25,

26,

27].

A review of 21 studies highlighted significant benefits of these programs in managing conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, and diabetes mellitus [

19]. Effective implementation of disease management programs can empower patients by helping them identify the most burdensome and persistent symptoms, fostering a holistic understanding and control of their condition.

These programs often include continuous patient education, enabling individuals to track their progress and recognize improvements over time [

28]. The incorporation of such patient-centered strategies reflects the direct link between healthcare system quality and patients’ lived experiences, ultimately contributing to more resilient and responsive healthcare delivery.

6. Certification and Accreditations Models

Once a healthcare institution becomes operational, its various components should seek certification, followed by an evaluation and potential accreditation of the institution as a whole [

25,

29]. Certification is defined as a process in which an external organization evaluates whether an individual, service, or system meets predefined, specific standards [

30]. It typically focuses on specialized aspects of a healthcare process, such as quality in specific services, safety protocols, or the use of technology.

In contrast, accreditation is a broader process through which an external entity evaluates an entire healthcare organization—such as a hospital or clinic—to determine whether it meets institutional-level standards for quality and continuous improvement (

Table 3). Accreditation considers not only specific clinical processes but also the overall organizational performance in areas such as patient safety, care quality, governance, and leadership [

30]. As part of the description of the quality assessment it is necessary to describe the organizations and boards [

29,

31,

32,

33].

6.1. International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 9001 Certification

The ISO 9001 certification program is a globally recognized quality management system used across sectors, including healthcare, to ensure consistent quality improvement and operational efficiency [

34]. This standard outlines general requirements for organizational structure, process management, customer satisfaction, continuous improvement, and effectiveness of quality systems (

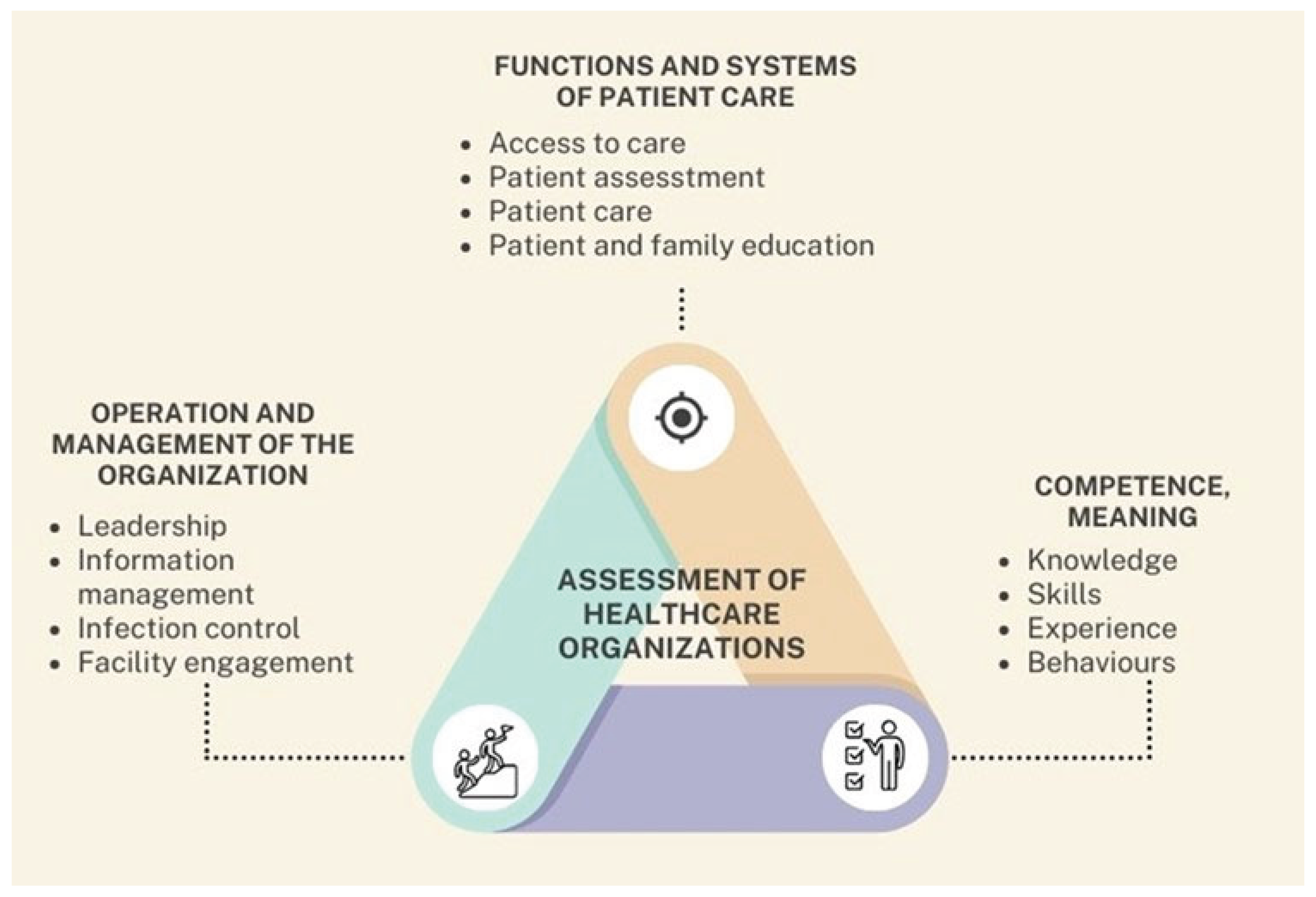

Figure 3). ISO 9001 certification evaluates whether an organization can consistently deliver services that meet both customer and regulatory standards [

34].

This figure illustrates a triangular conceptual model that outlines three fundamental domains involved in the comprehensive assessment of healthcare organizations. At the center lies the unifying concept “Assessment of Healthcare Organizations”, which represents the ongoing and dynamic process through which institutions evaluate their operational performance, identify strengths and weaknesses, and implement strategies for continuous improvement. Each vertex of the triangle corresponds to a critical dimension of institutional evaluation. The upper corner represents Functions and Systems of Patient Care, which encompasses essential components such as access to care, patient assessment, clinical care delivery, and education of both patients and their families. The right corner is dedicated to Competence, defined as the combination of knowledge, skills, experience, and behaviors demonstrated by healthcare personnel—elements that directly influence the quality and safety of patient care. The left corner focuses on the Operation and Management of the Organization, including leadership effectiveness, information management, infection control practices, and engagement with the physical infrastructure. This triangular framework emphasizes that the evaluation of healthcare organizations must be holistic, continuous, and interdependent. By systematically assessing these three domains, institutions can more effectively address performance gaps, reinforce areas of strength, and strategically evolve the quality of their care delivery systems.

This certification gained further significance due to its alignment with national internal control regulations in several countries, highlighting its relevance in regulatory frameworks. ISO 9001 certification confirms adherence to internationally accepted quality management standards and reflects an institution’s commitment to quality enhancement and accountability.

6.2. Joint Commission International

The Joint Commission International (JCI) is a global accreditation program specifically developed for healthcare organizations, particularly hospitals [

25]. Its primary goal is to improve the quality and safety of patient care worldwide through standardized accreditation processes and consultations.

JCI standards are adapted to the social, economic, and legal context of each country and healthcare organization. While institutions are required to conduct internal self-assessments and engage in quality improvement cycles, these results are not directly considered in the final accreditation decision. The accreditation focuses on three primary domains (

Figure 3): reducing risks posed by the facility environment, improving key processes of care, and safeguarding patient dignity and rights [

25].

A distinguishing feature of JCI accreditation is the opportunity for international benchmarking. Institutions accredited by JCI can compare their performance with peer organizations globally, fostering the adoption of evidence-based practices adaptable across different regulatory systems. JCI accreditation affirms that a healthcare center has achieved a level of performance aligned with international best practices [

25].

6.3. Canadian Healthcare Council

The Canadian Healthcare Council is an independent accrediting organization with presence in five countries, supported by healthcare institutions across Europe, the Americas, and Canada. Its accreditation framework includes four developmental stages [

35]: (i) proactive engagement in building a culture of patient safety, (ii) establishment of essential quality infrastructure, (iii) standardization and implementation of care processes, and (iv) consolidation of the quality infrastructure.

What differentiates this model is that its programs are designed by healthcare professionals who have firsthand experience in implementing national and international quality certification programs. The Canadian Healthcare Council’s model is based on a maturity-level approach that provides institutions with a structured roadmap to progressively improve care quality and develop a strong culture of patient safety [

35].

Through this process, the Council accredits healthcare institutions that meet established standards in quality and safety. This model not only aims to improve patient outcomes but also enhances operational efficiency and process optimization across healthcare systems both within and beyond Canada.

7. Perspectives and Conclusions

Although defining “quality of care” within healthcare systems remains a challenge—given that each system interprets quality based on its unique infrastructure, needs, and available resources—there is a shared consensus that the patient must remain the central focus. In this article, we propose a conceptualization of healthcare quality that integrates insights from previous literature with practical clinical applications. Our objective is to contribute to the development of more effective evaluation methodologies and models, ultimately fostering improvements in healthcare delivery and outcomes.

While a universally accepted model of quality care does not yet exist, several scales have proven valuable in assessing and improving healthcare systems. These tools evaluate various dimensions of service, such as tangibility (physical facilities and equipment), reliability (consistency and accuracy in service delivery), responsiveness (promptness and willingness to assist patients), assurance (staff knowledge and courtesy), and empathy (personalized and compassionate care). By measuring patients’ expectations and their actual experiences, these tools have provided healthcare administrators and practitioners with a better understanding of areas requiring improvement.

Nevertheless, a significant gap remains in the universal applicability of these tools. Most existing scales are designed for specific settings or populations, which leads to variability in data and limits their generalizability (

Figure 4). This underscores the need to develop a comprehensive and adaptable measurement scale capable of capturing the complexity of healthcare delivery across different contexts—ranging from small local clinics to large hospital systems, and encompassing a wide variety of patient-centered care in diverse cultural and economic contexts.

This figure presents a comprehensive, multi-layered conceptual model that synthesizes the key components involved in improving healthcare quality, as discussed throughout this article. At its core lies the central objective: “Improving Quality in Healthcare Systems”, which is surrounded by two major domains—Dimensions and Variables—represented in a concentric structure. The Dimensions domain includes fundamental aspects of care quality such as service delivery, social accountability, assurance, responsiveness, tangibility, reliability, and empathy. These elements represent the qualitative attributes that define patient-centered, efficient, and equitable healthcare. The Variables domain encompasses three distinct yet interconnected categories: variables dependent on personal attention (e.g., staff interaction and training), infrastructure-dependent variables (e.g., equipment and facility readiness), and patient-dependent variables (e.g., adherence, perception, and health literacy). These components reflect the dynamic inputs that influence how quality is implemented and experienced. Encircling these domains is a third layer that highlights the mechanisms for external evaluation: Certifications and Accreditations. These processes validate that healthcare institutions adhere to recognized quality standards and continuously strive for improvement. Together, the model encapsulates the interplay between internal organizational factors and external evaluative frameworks, offering a unified view of the path toward enhanced healthcare quality. It serves as a visual summary of the article’s conceptual foundation and emphasizes the need for an integrated, systems-based approach to quality improvement.

Creating such a scale would enable more consistent benchmarking, facilitate quality improvements across healthcare systems globally, and provide clearer insights into how well services align with patient expectations. Ultimately, this would enhance both clinical outcomes and the overall patient experience, contributing to higher standards of care worldwide.

Funding

This research did not received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Harteloh PP. The meaning of quality in health care: a conceptual analysis. Health Care Anal. 2003;11(3):259-67. [CrossRef]

- Campbell SM, Roland MO, Buetow SA. Defining quality of care. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(11):1611-25. [CrossRef]

- Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2001.

- Endeshaw B. Healthcare service quality-measurement models: a review. J Health Res. 2021;35(2):106-17. Available from: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JHR-07-2019-0152/full/html.

- Cheon O, Song M, McCrea AM, Meier KJ. Health care in America: The relationship between subjective and objective assessments of hospitals. Int Public Manag J. 2021;24(5):596-622. [CrossRef]

- Tauiwalo M, Robalino D, Frenk J. Improving the quality of care in developing countries. DCP70. 2004;:1292-307.

- Macdonald JS, Wolcott D. Quality Care, Outcome, Cost… A Complex Balance for Hospitals. Oncol Issues. 2007;22(2):32-6. [CrossRef]

- Jazieh AR. Quality measures: types, selection, and application in health care quality improvement projects. Glob J Qual Saf Healthc. 2020;3(4):144. [CrossRef]

- Meena K, Thakkar J. Development of balanced scorecard for healthcare using interpretive structural modeling and analytic network process. J Adv Manag Res. 2014;11(3):232-56. [CrossRef]

- Rademakers J, Delnoij D, de Boer D. Structure, process or outcome: which contributes most to patients’ overall assessment of healthcare quality?. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(4):326-31. [CrossRef]

- Kang GD. The hierarchical structure of service quality: integration of technical and functional quality. Manag Serv Qual. 2006;16(1):37-50. [CrossRef]

- Kang GD, James J. Service quality dimensions: an examination of Grönroos’s service quality model. Manag Serv Qual. 2004;14(4):266-77. [CrossRef]

- Murray CJ, Frenk J, World Health Organization. A WHO framework for health system performance assessment. 1999. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/66267/a68870.pdf.

- Papanicolas I, Rajan D, Karanikolos M, Soucat A, Figueras J. Health system performance assessment. 2022. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK590192.

- World Health Organization. Quality of care: a process for making strategic choices in health systems. Geneva: WHO; 2006. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/43470.

- Teshnizi SH, Aghamolaei T, Kahnouji K, Teshnizi SMH, Ghani J. Assessing quality of health services with the SERVQUAL model in Iran. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018;30(2):82-9. [CrossRef]

- Martilla JA, James JC. Importance-performance analysis. J Mark. 1977;41(1):77-9. [CrossRef]

- Izadi A, Jahani Y, Rafiei S, Masoud A, Vali L. Evaluating health service quality: using importance performance analysis. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2017;30(7):656-63. [CrossRef]

- Scott I. What are the most effective strategies for improving quality and safety of health care?. Intern Med J. 2009;39(6):389-400. [CrossRef]

- Fox J, Patkar V, Chronakis I, Begent R. From practice guidelines to clinical decision support: closing the loop. J R Soc Med. 2009;102(11):464-73. [CrossRef]

- Musen MA, Middleton B, Greenes RA. Clinical decision-support systems. In: Biomedical informatics: computer applications in health care and biomedicine. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 795-840. [CrossRef]

- Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Young JM, Odgaard-Jensen J, French SD, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(6):CD000259. [CrossRef]

- Ivers MN. Optimizing Audit and Feedback to Improve Quality in Primary Care [dissertation]. Toronto: University of Toronto; 2014. Available from: https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/68344.

- Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Ivers N. Audit and feedback as a quality strategy. In: Improving healthcare quality in Europe. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2019. p. 265. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549284/.

- Donahue KT, VanOstenberg P. Joint Commission International accreditation: relationship to four models of evaluation. Int J Qual Health Care. 2000;12(3):243-6. [CrossRef]

- Singh D, World Health Organization. How can chronic disease management programmes operate across care settings and providers?. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2008. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/107976.

- Wagner EH. The role of patient care teams in chronic disease management. BMJ. 2000;320(7234):569-72. [CrossRef]

- Rothman AA, Wagner EH. Chronic illness management: what is the role of primary care?. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):256-61. [CrossRef]

- Alkhenizan A, Shaw C. Impact of accreditation on the quality of healthcare services: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Saudi Med. 2011;31(4):407-16. [CrossRef]

- Hansche S. Official (ISC)2 Guide to the CISSP-ISSEP CBK. Boca Raton: Auerbach Publications; 2005. [CrossRef]

- Brooks M, Beauvais BM, Kruse CS, Fulton L, Mileski M, Ramamonjiarivelo Z, et al. Accreditation and certification: do they improve hospital financial and quality performance?. Healthc (Basel). 2021;9(7):887. [CrossRef]

- Greenfield D, Braithwaite J. Health sector accreditation research: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2008;20(3):172-83. [CrossRef]

- Devkaran S, O’Farrell PN. The impact of hospital accreditation on clinical documentation compliance: a life cycle explanation using interrupted time series analysis. BMJ Open. 2014;4(8):e005240. [CrossRef]

- Johannesen DTS. Certification for quality in hospitals. Exploring adoption, approaches and processes of ISO 9001 quality management system certification [master’s thesis]. Stavanger: University of Stavanger; 2020. Available from: https://uis.brage.unit.no/uis-xmlui/handle/11250/2682458.

- Canadian Healthcare Council [Internet]. Canada: Certification standards; [cited 2024 Oct 26]. Available from: https://canadianhealthcarec.ca/certification-standards/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).