Submitted:

12 June 2025

Posted:

12 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

MGG8 Glioma Stem Cell Line and Spheroid Culture Conditions

Photosensitizers Reagents

Quantification of NPe6 Uptake in MGG8 Cells

Photodynamic Therapy Protocol for MGG8 Cells

Assessment of Relative Mitochondrial Metabolic Activity

Assessment of Secondary Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Production

Quantification of Apoptosis and Necrosis by Flow Cytometry

Statistical Analysis

Results

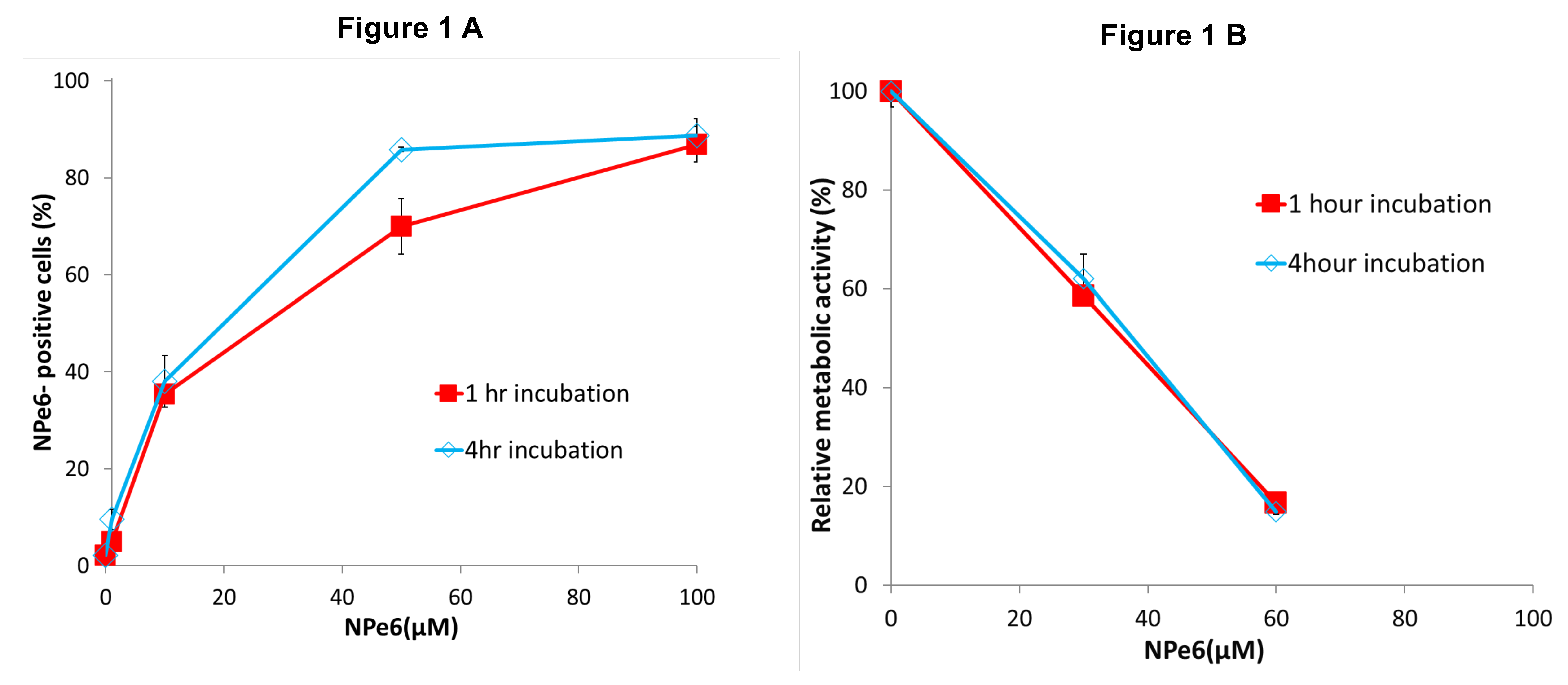

Uptake of NPe6 by MGG8

Effect of NPe6 Incubation Time on Early Metabolic Response in MGG8

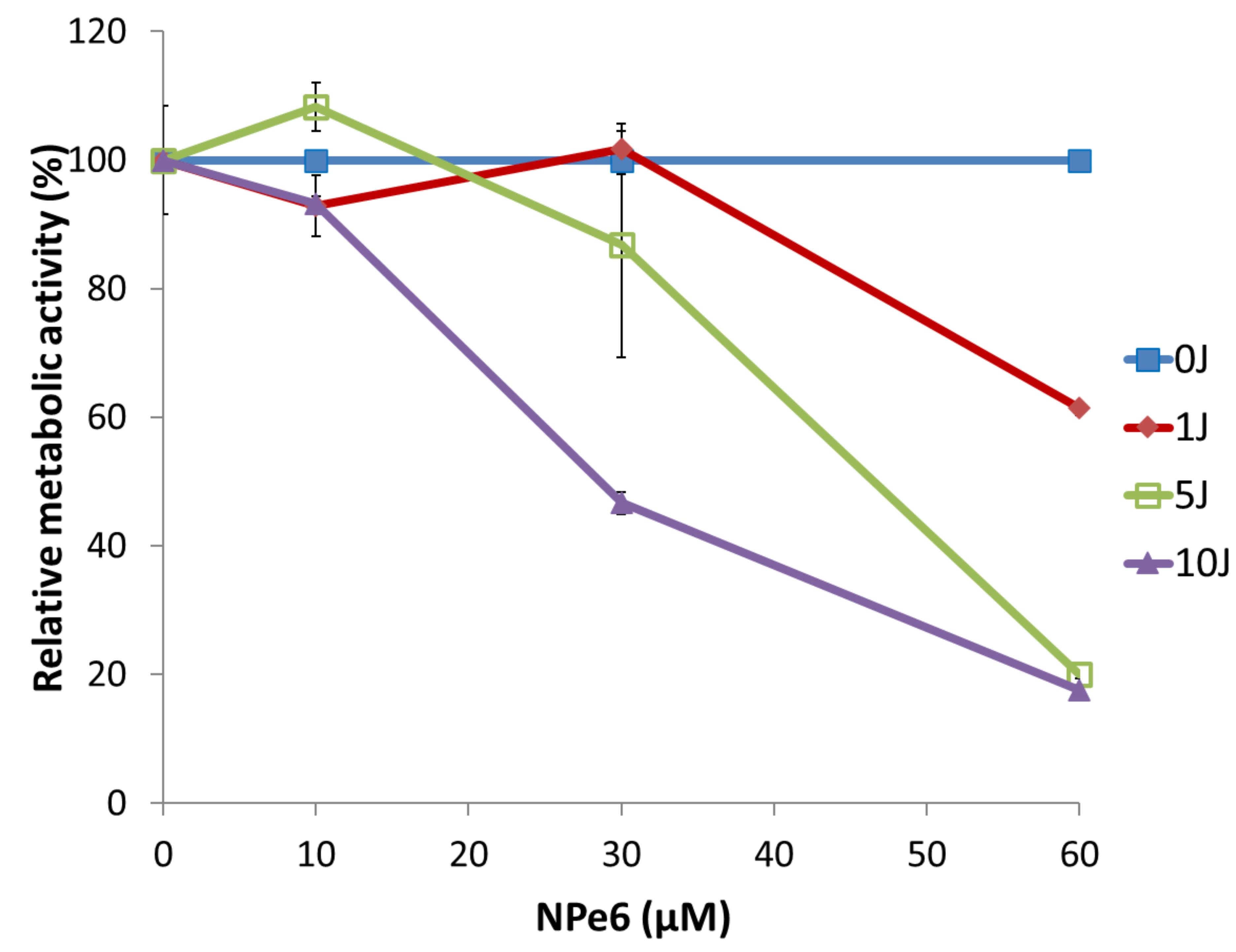

Dose- and Fluence-Dependent Changes in Early Mitochondrial Metabolic Activity in MGG8 Following NPe6-PDT

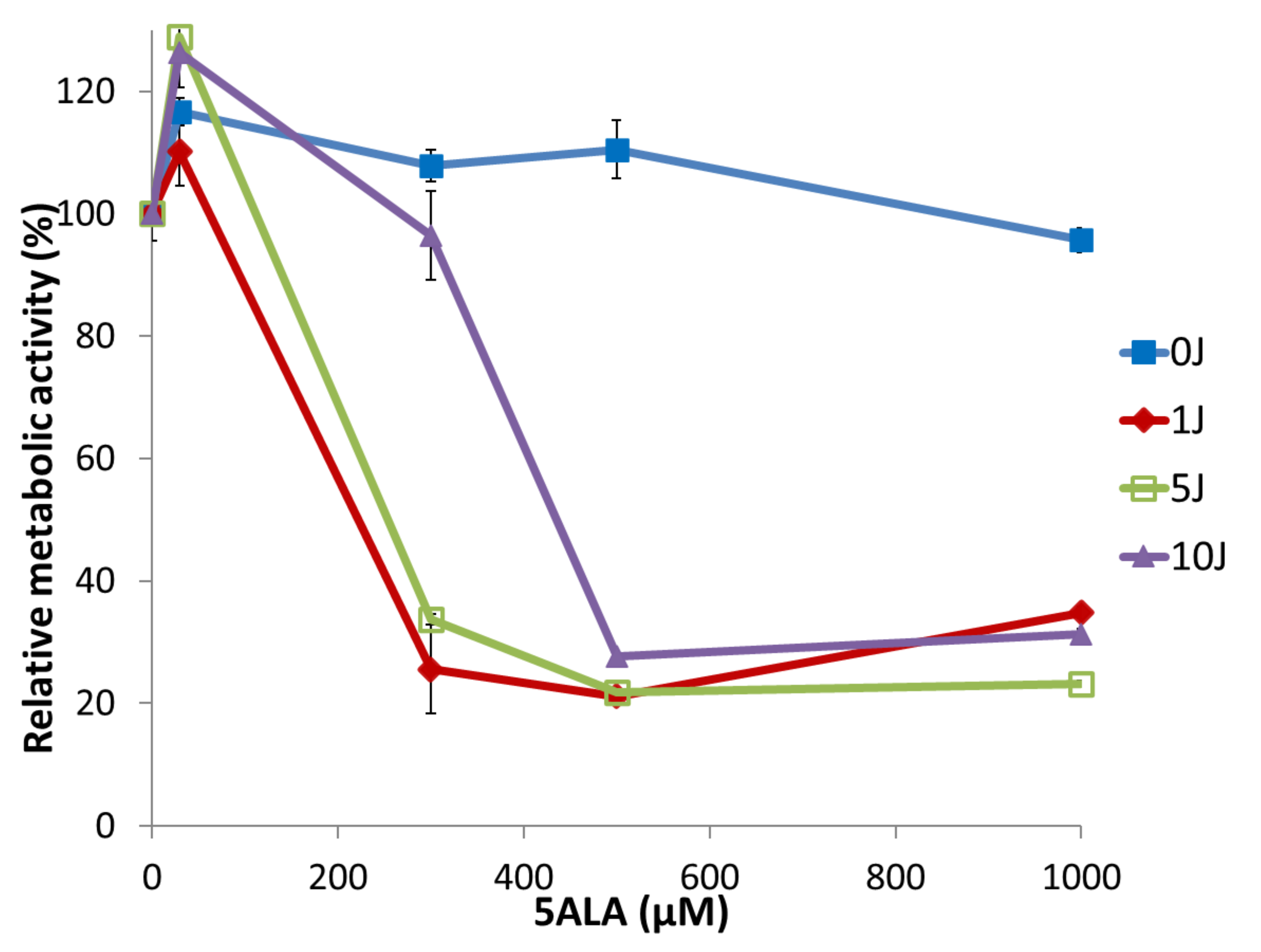

Dose- and Fluence-Dependent Changes in Early Mitochondrial Metabolic Activity in MGG8 Following 5-ALA–PDT

Comparison of Secondary ROS Accumulation Induced by NPe6-PDT and 5-ALA–PDT

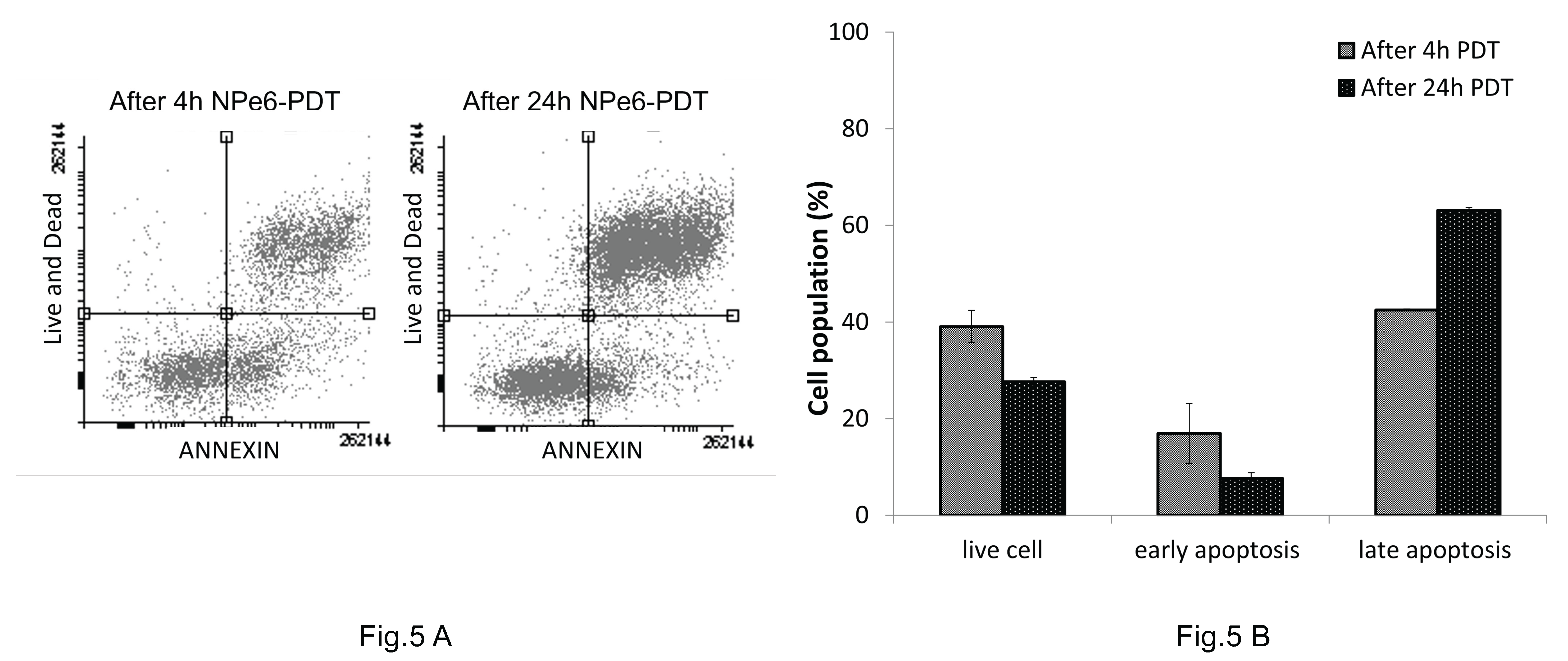

Time-Dependent Apoptosis and Necrosis Induced by NPe6-PDT in MGG8 Cells

Discussion

Conclusion

Ethics Approval

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stupp, R.; Mason, W.P.; van den Bent, M.J.; Weller, M.; Fisher, B.; Taphoorn, M.J.B.; Belanger, K.; Brandes, A.A.; Marosi, C.; Bogdahn, U.; Curschmann, J.; Janzer, R.C.; Ludwin, S.K.; Gorlia, T.; Allgeier, A.; Lacombe, D.; Cairncross, J.G.; Eisenhauer, E.; Mirimanoff, R.O. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. NEJM. 2005, 10, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, A.H.; Beck, J.; Schnell, O.; Fung, C.; Meyer, B.; Gempt, J. Surgical treatment of glioblastoma: state-of-the-art and future trend. J Clin Med. 2022, 11, 5354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jusue-Torres, I.; Lee, J.; Germanwala, A.V.; Burns, T.; Parney, I.F. Effect of extent of resection on survival of patients with glioblastoma, IDH Wild-type, WHO Grade 4 (WHO 2021): systematic review and meta-analysis. World Neurosurg. 2023, 171, e524–e532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keles, G.E.; Lamborn, K.R.; Chang, S.M.; Prados, M.D.; Berger, M.S. Volume of residual disease as a predictor of outcome in adult patients with recurrent supratentorial glioblastomas multiforme who are undergoing chemotherapy. J Neurosurg. 2004, 100, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, M.; Aoyagi, M.; Wakimoto, H.; Ando, N.; Nariai, T.; Tamamoto, M.; Ohno, K. Accumulation of CD133-positive glioma cells after high-dose irradiation by gamma knife surgery plus external beam radiation. J Neurosurg. 2010, 113, 310–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, M.; Aoyagi, M.; Ando, N.; Ogishima, T.; Wakimoto, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Ohno, K. Expansion of CD133-positive glioma stem cells in recurrent de novo glioblastomas after radiotherapy and chemotherapy. J Neurosurg. 2013, 119, 1145–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Hawkins, C.; Clarke, I.D.; Squire, J.A.; Bayani, J.; Hide, T.; Henkelman, R.M.; Cusimano, M.D.; Dirks, P.B. Identification of human brain tumor initiating cells. Nature. 2004, 432, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Clarke, I.D.; Terasaki, M.; Bonn, V.E.; Hawkins, C.; Squire, J.; Dirks, P.B. Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 5821–8. [Google Scholar]

- Altaner, C. Glioblastoma and stem cells. Neoplasma. 2008, 55, 369–74. [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsumi, M.; Miki, Y.; Akimoto, J.; Haraoka, J.; Aizawa, K.; Hirano, K.; Beppu, M. Photodynamic therapy with talaporfin sodium induces dose-dependent apoptotic cell death in human glioma cell lines. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2013, 10, 103–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miki, Y.; Akimoto, J.; Yokoyama, S.; Homma, T.; Tsutsumi, M.; Haraoka, J.; Hirano, K. ; BeppuM Photodynamic therapy in combination with talaporfin sodium induces mitochondrial apoptotic cell death accompanied with necrosis in glioma cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2013, 36, 215–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miki, Y.; Akimoto, J.; Hiranuma, M.; Fujiwara, Y. Effect of talaporfin sodium-mediated photodynamic therapy in cell death modalities in human glioblastoma T98G cells. J Toxicol Sci. 2014, 39, 821–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miki, Y.; Akimoto, J.; Moritake, K.; Hironaka, C.; Fujiwara, Y. Photodynamic therapy using talaporfin sodium induces concentration-dependent programmed necroptosis inhuman glioblastoma T98G cells. Lasers Med Sci. 2015 Aug;30,1739-45. [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa, M.; Akimoto, J.; Miki, Y.; Maeda, J.; Takahashi, T.; Fujiwara, Y.; Kohno, M. Photodynamic therapy with talaporfin sodium induces dose-and time-dependent apoptotic cell death in malignant meningioma HKBMM cells. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2019, 25, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akimoto, J. Photodynamic therapy for malignant brain tumors. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2016, 56, 151–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimoto, J.; Haraoka, J.; Aizawa, K. Preliminary clinical report on safety and efficacy of photodynamic therapy using talaporfin sodium for malignant gliomas. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2012, 9, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muragaki, Y.; Akimoto, J.; Maruyama, T.; Iseki, H.; Ikuta, S.; Nitta, M.; Maebayashi, K.; Saito, T.; Okada, Y.; Kaneko, S.; Matsumura, A.; Kuroiwa, T.; Karasawa, K.; Nakazato, Y.; Kayama, T. Phase II clinical study on intraoperative photodynamic therapy with talaporfin sodium and semiconductor laser in patients with malignant brain tumors. J Neurosurg. 2013, 119, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitta, M.; Muragaki, Y.; Maruyama, T.; Iseki, H.; Komori, T.; Ikuta, S.; Saito, T.; Yasuda, T.; Hosono, J.; Okamoto, S.; Koriyama, S.; Kawamata, T. Role of photodynamic therapyusing ta laporfin sodium and a semiconductor laser in patients with newly diagnosedglioblastoma. J Neurosurg. 2018, 131, 1361–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.H.; Yu, C.C. Photodynamic therapy with 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) impairs tumor initiating and chemo-resistance property in head and neck cancer-derived cancer stem cells. PLos One 2014, 9, e87129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishiro, T.; Nonoguchi, N.; Pavliukov, M.; Ohmura, N.; Kawabata, S.; Park, Y.; Kajimoto, Y.; Ishikawa, T.; Nakano, I.; Kuroiwa, T. 5-Aminolevulinic acid-mediated photodynamic therapy can target human glioma stem-like cells refractory to antineoplastic agent. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2018 Dec;24:58-68. [CrossRef]

- Wakimoto, H.; Kesari, S.; Farrell, C.J.; Curry WTJr Zaupa, C.; Aghi, M.; Kuroda, T.; Stemmer- Rachamimov, A.; Shah, K.; Liu, T.C.; Jeyaretna, D.S.; Debasitis, J.; Pruszak, J.; Martuza, R.L.; Rabkin, S.D. Huma glioblastoma-derived cancer stem cells: establishment of invasive glioma models and treatment with oncolytic virus vectors. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 3472–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakimoto, H.; Mohapatra, G.; Kanai, R.; Curry WTJr Yip, S.; Nitta, M.; Patel, A.P.; Barnard, Z.R.; Stemmer-Rachamimov, A.O.; Louis, D.N.; Martuza, R.L.; Rabkin, S.D. Maintenance of primary tumor phenotype and genotype in glioblastoma stem cells. Neuro Oncol. 2012, 14, 132–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimoto, Y.; Fujita, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Nagashima, H.; Yamanishi, S.; Ikeuchi, Y.; Iwahashi, H.; Sanada, S.; Muragaki, Y.; Sasayama, T. Clinical benefits of photodynamic therapy using talaporfin sodium in patients with isocitrate dehydrogenase-wildtype diagnosed. glioblastoma: A retrospective study of 100 cases. Neurosurg 2024; 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chaichana, K.L.; Kleinberg, L.; Ye, X.; Quinones-Hinojosa, A.; Redmond, K. Glioblastoma recurrence patterns near neural stem cell regions. Radiother Oncol. 2015, 116, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafri, N.F. Relationship of glioblastoma multiforme to the subventricular zone is associated with survival. Neuro Oncol. 2013, 15, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, D.A.; Cha, S.; Mayo, M.C.; Chen, M.H.; Keles, E.; VandenBerg, S.; Berger, M.S. Relationship of glioblastoma multiforme to neural stem cell region predicts invasive and multifocal tumor phenotype. Neuro Oncol. 2007, 9, 424–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, T.; Miyazaki, M.; Sasaki, N.; Yamamuro, S.; Uchida, E.; Kawauchi, D.; Takahashi, M.; Otsuka, Y.; Kumagai, K.; Takeuchi, S.; Toyooka, T.; Otani, N.; Wada, K.; Narita, Y.; Yamaguchi, H.; Muragaki, Y.; Kawamata, T.; Mori, K.; Ichimura, K.; Tomiyama, A. Enhanced malignant phenotypes of glioblastoma cells surviving Npe6-mediated photodynamic therapy are regulated via ERK1/2 activation. Cancers (Basel). 2020, 12, 3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riss, T.L.; et al. Cell viability assays. In: Markossian S, Grossman A, et al., editors. Assay Guidance Manual [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; 2013.

- van Tonder, A.; Joubert, A.M.; Cromarty, A.D. Limitations of the 3-(4,5 dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay when compared to three commonly used cell enumeration assays. BMC Research Notes. 2015, 8, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlin, J.L.; et al. Measurement of cytotoxicity by MTT assay. Cancer Detection and Prevention. 1987, 10, 379–385. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Kader, M.H.; Stepp, H.; Aniogo, E.C.; Abrahamse, H. In vitro study for photodynamic therapy using Fotolon® in glioma cells. Proc SPIE. 2015, 9542, 95420B. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, A.; Stepp, H.; Abdel-Kader, M.H. LD50 determination in glioma cell lines via MTT following PDT. Proc SPIE. 2015, 9542, 95420B. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.; Kim, H.; Lee, H.; Lee, J.; Kim, K.; Hasan, T.; et al. Enhanced efficacy of photodynamic therapy by inhibiting ABCG2 in colon cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2015, 15, 109. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, H.S.; Golub, M. Photodynamic therapy: the development of new photosensitizers. In: Photodynamic Therapy: Methods and Protocols. Humana Press, 2010.

- Chen, X.; Zhong, Z.; Xu, Z.; Chen, L.; Wang, Y. 2′,7′-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein as a fluorescent probe for reactive oxygen species measurement: forty years of application and controversy. Free Radic Res. 2010, 44, 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrona, M.; Patel, K.B.; Wardman, P. The roles of thiol-derived radicals in the use of 2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein as a probe for oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008, 44, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setsukinai, K.; Urano, Y.; Kakinuma, K.; Majima, H.J.; Nagano, T. Development of novel fluorescence probes that can reliably detect reactive oxygen species and distinguish specific species. J Biol Chem. 3004, 278, 3170–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, D.; Zha, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Hou, S. Improved detection of reactive oxygen species by DCFH-DA: New insight into self-amplification of fluorescence signal by light irradiation. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 2021, 329, 129246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.T.; Chen, Q.; Wang, D.W.; Bai, D.Q. Mitochondrial pathway and endoplasmic reticulum stress participate in the photosensitizing effectiveness of AE-PDT in MG63 cells. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy. 2016, 13, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Fan, Q.; Yang, M.; Cheng, K.; Lu, X.; Zhang, L.; et al. Engineering a ROS-responsive nanoplatform for synergistic photodynamic and chemotherapy. Frontiers in Chemistry. 2018, 6, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, W.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X. Secondary ROS mediate PDT-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in glioma. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2023, 27, 2456–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A.; Kasoju, N.; Bora, U. Fluorescence based detection of intracellular ROS in living cells. Micron. 2020, 101, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, C.; Xu, H.; Sun, J.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; et al. Photodynamic therapy induces secondary oxidative stress in cancer cells. Cancer Letters. 2016, 370, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Xing, D. Cell death via mitochondrial apoptotic pathway due to activation of Bax by lysosomal photodamage. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011, 51, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormond, A.B.; Freeman, H.S. Dye Sensitizers for Photodynamic Therapy. Materials. 2013, 6, 817–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormond, A.B.; Freeman, H.S. Dye Sensitizers for Photodynamic Therapy. Materials. 2013, 6, 817–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heddleston, J.M.; Li, Z.; McLendon, R.E.; Hjelmeland, A.B.; Rich, J.N. The hypoxic microenvironment maintains glioblastoma stem cells and promotes reprogramming towards a cancer stem cell phenotype. Cell Cycle. 2009, 8, 3274–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, T.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, X.; Mao, X. The role of hypoxia and cancer stem cells in development of glioblastoma. Cancers (Basel). 2023, 15, 2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, D.; Prager, B.C.; Gimple, R.C.; Poh, H.X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Qiu, Z.; Kidwell, R.L.; Kim, L.J.Y.; Xie, Q.; Vitting-Seerup, K.; Bhargava, S.; Dong, Z.; Jiang, L.; Hamerlik, P.; Jaffrey, S.R.; Zhao, J.C.; wang, X.; Rich, J.N. The RNA m6A reader YTHDF2 maintains oncogene expression and Is a targetable dependency in glioblastoma stem cells. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 480–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, T.J.; Kreth, F.W.; Beyer, W.; Mehrkens, J.H.; Obermeier, A.; Stepp, H.; Stummer, W.; Baumgartner, R. Interstitial photodynamic therapy of nonresectable malignant glioma recurrence using 5-aminolevulinic acid induced protoporphyrin IX. Laser Surg Med. 2007, 39, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lietke, S.; Schmutzer, M.; Schwartz, C.; Weller, J.; Siller, S.; Aumiller, M.; Heckl, C.; Forbrig, R.; Niyazi, M.; Egensperger, R.; Stepp, H.; Sroka, C.; Tonn, J.C.; Ruhm, A.; Thon, N. Interstitial photodynamic therapy using 5-ALA for malignant glioma recurrence. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlroy, D.R.; Shotwell, M.S.; Lopez, M.G.; Vaughn, M.T.; Olsen, J.S.; Hennessy, C.; Wanderer, J.P.; Semler, M.S.; Rice, T.W.; Kheterpal, S.; Billings, F.T.I.V. Oxygen administration during surgery and postoperative organ injury: observational cohort study. BMJ. 2022, 379, e070941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).