1. Introduction

The genus

Paenibacillus was originally described by Ash et al. based on the 16S rRNA gene analysis [

1], and later emended by Shida et al., who proposed six new species in the genus [

2]. The continuous emergence of new members increased the number of species belonging to

Paenibacillus. At the time of writing (June 2025), the genus contains 323 species with validly published and correct names (

https://lpsn.dsmz.de/genus/paenibacillus). Some members of this genus are rod shaped, aerobic or facultative anaerobic, motile or nonmotile, and endospore-form bacteria [

3,

4,

5].

Paenibacillus species can be found in many ecological niches, such as fish gut [

6], river otter [

7], seashore land [

8], hot spring [

9], salt lake [

10], digestive syrup [

11], plants [

12], and soil [

13]. Among the genus, groups of species play a vital role in agricultural application through nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization, production of ACC deaminase, and IAA secretion [

14,

15,

16], which are regarded as plant growth-promoting bacteria/rhizobacteria (PGPB/PGPR) [

17,

18,

19].

Selenium (Se), an essential trace nutrient, has multiple biological functions, including roles in male reproductive health, the endocrine system, muscle function, the central nervous and cardiovascular systems, and immune syestems [

20]. Research on Se has attracted extensive focus, partly because of selenocysteine, the constitutive part of the 21st amino acid, making it the only trace nutrient incorporated into proteins through genetic coding [

21]. For example, certain Se functional microorganisms, called Se-respiring bacteria, play a pivotal role in the selenium cycle. Some selenate- or selenite-respiring bacteria are capable of producing Se nanoparticles [

22]. Lin et al. [

23] reported that

Priestia sp. LWS1, a Se-resistant PGPR, could promote plant growth by 19% and Se accumulation by 75% in

Oryza sativa.

Therefore, screening and isolating agricultural beneficial Se-resistant microorganisms from various habitats is imperative. In this study, a selenium-resistant PGPR, ES5-4T was isolated from the rhizosphere of Galinsoga parviflora and characterized using polyphasic analysis; the results indicate that it is likely a novel species of the genus Paenibacillus.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Isolation of Bacterial Strain

G. parviflora is the numerous species growing in selenium-rich ore area of Enshi, Hubei Province, China (30°8´43´´N 109°49´32´´E). Therefore, the rhizobacterial soil was collected in October 2020. The selenium (Se) content of the soil is 3.57 mg/kg, higher than 0.4 mg/kg, which was considered selenium-rich soil based on the national standard for soil selenium grade (GB/T 44971-2024). The bacterial isolation was based on the method described by Li et al. [

24]. Briefly, the soil sample was diluted to 10

-3 to 10

-5 with sterile ddH

2O using a 10-fold dilution gradient and then smeared on Trypticase soy broth agar (TSA) medium supplemented with 20 mg/L of Se solution (Na

2SeO

3). After incubation for 3 days at 28 °C in an incubator, the single colony was selected, purified, and incubated on TSA plates with higher Se concentrations successively (50, 100, 200, 500, 1000, and 2000 mg/L). Finally, the strain ES5-4

T was obtained and maintained on TSA and preserved in 30% glycerol suspension at −80°C.

2.2. 16. S rRNA Gene Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis

The strain was cultivated in Trypticase soy broth (TSB) medium for 12 h to the exponential growth stage at 180 rpm in a rotary shaker (ZWY-2101C) at 28 °C. Next, the cell suspensions were used for the extraction of genomic DNA using a DNA isolation kit (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The 16S rRNA gene was amplified by PCR using the universal primers 27F and 1492R [

25]. The PCR products were purified and sequenced by Sangon Biotech. The obtained 16S rRNA gene sequence was analyzed using the EzBioCloud server (

https://www.ezbiocloud.net/) [

26]. Multiple sequence alignments were performed using ClustalW software (

http://www.clustal.org/clustal2/) [

27]. Next, phylogenetic analysis of the 16S rRNA gene of strain ES5-4

T was conducted based on neighbor-joining (NJ), maximum-parsimony (MP), and maximum likelihood (ML) algorithms using MEGA 7 software [

28]. Phylogenetic distances were calculated according to Kimura’s two-parameter model [

29]. The bootstrap values were set as 1000 replications, as described by Felsenstein [

30].

2.3. Genomic Characterization

Strain ES5-4

T was incubated to the exponential growth stage as mentioned above. The cell suspension was then centrifuged at 4 °C at 8000 ×

g, the supernatant was discarded, the mycelium was rinsed three times with sterile deionized water, and the mycelium was collected and used for genome sequencing. A draft genome sequence of strain ES5-4

T was conducted using the Illumina HiSeq X platform (Personalbio, Shanghai, China). Raw sequence reads were filtered and quality controlled using FastQC [

31]. The high-quality reads were

de novo assembled using SPAdes v3.15.3 [

32] in the UGENE software package [

33]. The G+C content of the genomic DNA was directly determined using the draft genome sequence. Values of average nucleotide identity (ANI) based on BLAST (OrthoANIb) between strain ES5-4

T and its close relatives (

Paenibacillus illinoisensis NBRC 15959

T,

Paenibacillus pabuli NBRC 13638

T,

Paenibacillus taichungensis DSM 19942

T, and

Paenibacillus xylanivorans A59

T) was calculated on the EzBioCloud server [

26]. The Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC) online service (

http://ggdc.dsmz.de/distcalc2.php) was used to calculate the digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH) values by applying Formula 2 [

34]. Annotation was performed using the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline [

35] and online eggnog-mapper v2 server (

https://eggnog-mapper.embl.de/) [

36].

To confirm the taxonomic status of the type strain, a genome-based ML phylogenetic tree (bac120 tree) [

37] was constructed based on the protein sequences of the genus

Paenibacillus, along with the outgroup. Generally, genomic information of type strains in the genus

Paenibacillus was collected using scripts (

https://github.com/zdf1987/Usefull_Scripts/GetTypeStrainGenomes) and the proteomes were downloaded using the NCBI software datasets (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/docs/v2/download-and-install/). Other genomic datasets of strains that closely related to strain ES5-4

T were downloaded manually. Gene sequences of each gene cluster were aligned using MUSCLE [

38], and the ML tree was constructed using FastTree 2.1 [

39] based on the common genes in the bac120 set after alignment trimming and concatenation. The bac120 tree was constructed automatically using EasyCGTree v4.2 (

https://github.com/zdf1987/EasyCGTree4) [

40].

2.4. Phenotypic and Biochemical Characterization

The phenotypic characteristics of strain ES5-4

T were evaluated on TSA. Gram staining was conducted using a Gram-staining kit (DM0015, Leagene, Beijing, China). Cell morphology of the strain was visualized using scanning (Sirion 200) and transmission electron microscopes (SEM, Sirion 200; TEM, Tecnai G2 spirit Bio-Twin) [

41]. The effect of temperature (4, 10, 20, 28, 37, and 45 °C) on bacterial growth was observed on the TSA after 3 days of incubation. The pH in the range of 4.0 to 10.0 with an increment of 1.0 for bacterial growth was also assessed. The pH was adjusted with 1 M HCl or NaOH. Salt tolerance was evaluated using various NaCl concentrations (0%, 0.5%, 1.0%, 2.0%, 3.0%, 5%, 7%, and 10% w/v). The bacterial motility experiment was conducted by observing cell growth in test tubes with semisolid TSB with 0.5% agar after 3 days of incubation in an incubator at 28 °C. Other physiological and biochemical characteristics of the strain were determined using API 50CH (bioMérieux, France) and Biology GEN III micro test systems (Biology, USA). The reference strains (

Paenibacillus oceanisediminis JCM17814

T,

Paenibacillus dongdonensis KCTC 33221

T) used in the study were provided by Marine Culture Collection of China (MCCC). All experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.5. Chemotaxonomic Analysis

Strain ES5-4

T and its reference type strains were cultivated in TSB until to the logarithmic phase at 180 rpm in a rotary shaker (ZWY-2101C) at 28 °C. The cells were collected, washed, and lyophilized in a freeze dryer (Labconco, Kansas City, USA) [

42]. The dried cells were used for cellular fatty acids, respiratory quinones, and polar lipid analysis. Cellular fatty acids were extracted and analyzed using the Sherlock Microbial Identification System (MIDI) following Sasser’s protocol [

43]. Quinones were purified and analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography [

44]. Polar lipids were first extracted based on the method of Minnikin et al. [

45], and identified using two-dimensional thin-layer chromatography, according to Komagata and Suzuki [

46].

2.6. Effects of Se4+ Concentration on the Growth of Strain ES5-4T

To assess the effect of Se4+ (supplied as Na2SeO3) on the cell growth of strain ES5-4T, TSA and TSB media with various Se concentrations (0, 20, 50, 100, 200, 500, 1,000, 2,000, and 5,000 mg/L) were prepared. For the TSB test, 600 μL of overnight cultured cell suspension, equivalent to 3% inoculation volume (v/v), were added to 50-mL sterile Erlenmeyer flasks containing 20 mL of TSB with aforementioned Se4+ concentration and cultured for 2 days in a rotary shaker (ZWY-2101C) at 180 rpm at 28 ℃. Next, the optical density at the 600 nm wavelength (OD600) was measured using a Multiskan Go microplate spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, CA, USA). Cell growth on TSA plates containing equivalent Se4+ concentrations was also performed. Each plate was evenly divided into three compartments, and 0.5 μL of overnight cultured cell suspension was dripped into each compartment, cultured in a biochemical incubator (Xinmiao, Shanghai, China) for 2 days at 28 ℃, and the growth of strain ES5-4T was recorded. The diameter of the colonies of strain ES5-4T was measured using a digital vernier caliper (DWGR-2954, DELIXI, China). All experiments were performed in triplicate.

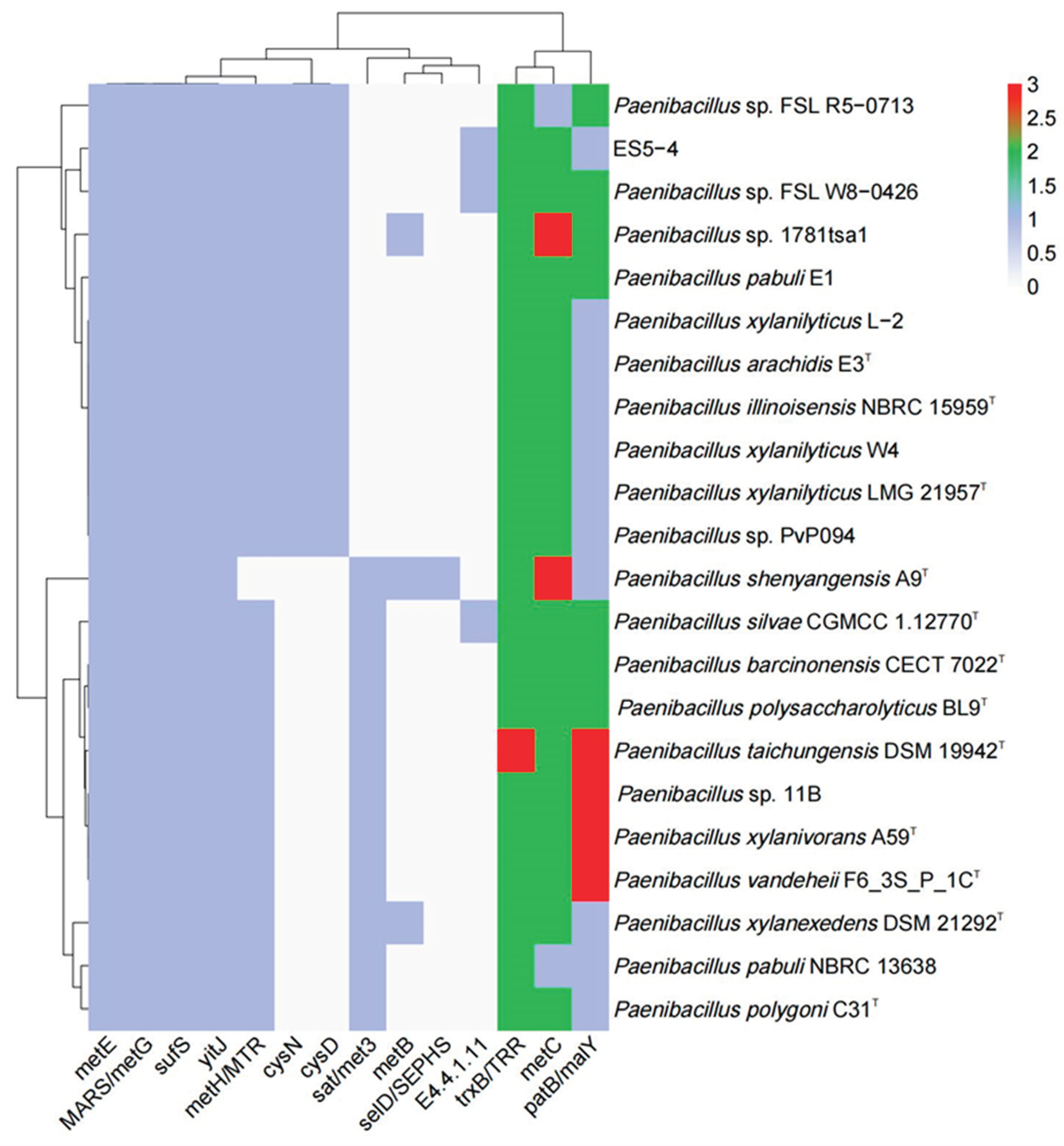

2.7. Identification of the Functional Gene for Selenocompound Metabolism

Twenty-two genes involved in selenocompound metabolism (map00450) in bacteria of the genus

Paenibacillus were identified according to a strategy similar to that previously described [

47]. Briefly, profile hidden Markov models (HMMs) of the 22 relevant genes were retrieved from the KOfam database (

https://www.genome.jp/ftp/db/kofam/) [

48]. These HMMs were merged and adjusted to meet the requirements of the HMMER v3.0 software (

http://hmmer.org), which was used by the analysis pipeline based on EasyCGTree v4.2 (

https://github.com/zdf1987/EasyCGTree4) [

49]. Subsequently, the "Gene_Prevelence.pl" script within the EasyCGTree software package was used to search for homologous genomes using customized HMMs with an e-value cutoff of 1e-80. All candidate genes were further submitted to the online annotation tool KofamKOALA (

https://www.kegg.jp/kofamkoala/) [

48] for homolog verification. Finally, the online tool ImageGP2 (

https://www.bic.ac.cn/BIC/#/) was employed to generate a heatmap of the gene distribution.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA. Pairwise differences among treatments were performed using Duncan’s multiple range test. Data were visualized using SigmaPlot 14.0 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA, USA). All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 20.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), with a significance level set at p < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Phylogenetic Analysis of the 16S rRNA Gene

The 16S rRNA gene sequence of the strain ES5-4

T was 1,403 bp in length, spanning the complete gene sequence (1552 bp; RefSeq accession NZ_JAVYAE020000044) with three mismatches, and has been deposited at GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ (accession number: OR584159). Strain ES5-4

T shared the highest 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity (98.4%) with

P. pabuli NBRC 13638

T based on the results from EzBioCloud server [

26], followed by

P. dongdonensis KUDC 0114

T (98.3%) [

50],

P. taichungensis BCRC 17757

T (98.3%) [

51] and

P. xylanivorans A59

T (98.0%) [

52]. Alignment of the full-length 16S rRNA gene on the genome against the genome database (refseq_genomes and wgs) on NCBI suggested that there were some genomes from uncharacterized bacteria sharing 16S rRNA gene identities of > 98.5% to strain ES5-4

T, including

Paenibacillus sp. FSL W8-0426 (100%, NZ_CP150203.1),

P. pabuli E1 (98.8%, NZ_CP073714.1),

P. xylanilyticus W4 (98.7%, NZ_CP044310.1),

Paenibacillus sp. 11B (98.6%, NZ JAUKNS010000005.1),

P. xylanilyticus L-2 (98.6%, NZ CP182582.1),

Paenibacillus sp. 1781tsa1 (98.58%, NZ JAMYWY010000001.1),

Paenibacillus sp. PvP094 (98.5%, NZ JBEPOM010000001.1), and

Paenibacillus sp. FSL R5-0713 (98.5%, NZ_CP150229.1).

Phylogenetic analysis using ML method indicated that strain ES5-4

T clustered with

P. dongdonensis KUDC 0114

T (

Figure 1). The MP method revealed that the strain clustered with

P. illinoisensis NRRL NRS-1356

T and

P. xylanilyticus XIL 14

T (

Figure S1). The above two topologies could not be reproduced in the trees using the NJ method (

Figure S2). In addition, this phylogeny was not well supported (bootstrap value < 70%) in all three trees. This meant phylogenetic analysis based on the 16S rRNA gene in the genus

Paenibacillus was not reliable.

P. dongdonensis KUDC 0114

T (= KCTC 33221

T) and

P. oceanisediminis L 10

T (= JCM 17814

T) were used as reference strains in the following tests because they have no available genomes for genome-based distinguishing from strain ES5-4

T.

3.2. Genome-Based Characteristics

The whole Genome Shotgun project of strain ES5-4T has been deposited at GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ with the accession number JAVYAE000000000. The whole draft genome contained 58 contigs, with a total length of 7,190,355 bp, and the genome G + C content was 50.5%. A total of 6,300 protein coding genes were predicted, of which 642, 3, 046 and 5, 370 genes were assigned to the Gene Ontology (GO), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), and Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COG) databases, respectively. Further KEGG pathway analysis revealed 34 genes involved in flagellar assembly (ko02040), 3 genes (narI, narJ, and narH) associated with nitrate reduction, 3 genes (cysI, cysJ, and nirB) with sulfite reduction, the nitrogen fixation gene nifU, and 317 ABC transporters; no photosynthesis gene cluster was detected.

According to the taxa of the 16S rRNA gene tree, 205

Paenibacillus genomes (including the seven aforementioned atypical strains together with genomes of strain ES5-4

T and

Staphylococcus aureus NCTC 8325

T (GCA000013425.1, as outgroup) were used to infer a robust tree based on the bac120 gene set (

Figure 2). The bac120 tree was well supported on all branches. Strain ES5-4

T was closely related to

Paenibacillus sp. FSL W8-0426 (GCA_037969725.1) and was subsequently clustered with ten

Paenibacillus species, including

P. pabuli NBRC 13638

T,

P. taichungensis DSM 19942

T, and

P. xylanivorans A59

T. The results of the 16S rRNA gene tree and bac120 tree both demonstrated that the strain was within the genus

Paenibacillus.

ANIb values between strain ES5-4

T and the closely related strains

P. pabuli NBRC 13638

T (GCA004000925.1),

P. taichungensis DSM 19942

T (GCA013359905.1),

P. xylanivorans A59

T (GCA001280595.1) and

P. illinoisensis NBRC 15959

T (GCA004000925.1) were 76.4%, 76.2%, 76.3% and 76.8%, respectively, whereas the corresponding dDDH values were 21.2%, 20.9%, 20.6% and 21.6%, respectively (

Table 1). These values were lower than the proposed and acceptable species boundaries of 95-96% for ANI and 70% for dDDH [

53,

54]. In addition, strain ES5-4

T showed an ANI value of 98.8% with strain

Paenibacillus sp. FSL W8-0426 (GCA_037969725.1), which had a 16S rRNA gene similarity of 100%. Taken together, these findings imply that the strain ES5-4

T represents a novel

Paenibacillus species.

3.3. Phenotypic and Biochemical Characteristics

Strain ES5-4

T was found to be Gram positive, aerobic, and motile with flagella (

Figure 3A), and the features were consistent with the description of

Paenibacillus flagellatus [

55]. SEM image of strain ES5-4

T cells showed a rod-shaped profile with 0.4–0.6 μm width and 1.0–2.5 μm length (

Figure 3B). Colonies on TSA were white, circle, moist, and smooth after incubation for 72 h at 28 °C. Growth occurred at NaCl concentrations of 0–5.0% (w/v), pH of 5.0–10.0, and temperature of 4–42°C. The optimal growth conditions for strain ES5-4

T were 0.5%–1.0% (w/v) NaCl, pH of 5.0–7.0, and 28 °C; those for

P. dongdonensis KCTC 33221

T were 0.5%–2.0% (w/v) NaCl, pH of 6.0–7.0, 28 °C; and those for for

P. oceanisediminis JCM17814

T were 0.5–1.0% (w/v) NaCl, pH of 7.0–8.0, and 28 °C (

Table 2).

In the API 50CH tests, strain ES5-4

T was only positive for esculin, and negative for L-arabinose, ribose, D-xylose, β- methyl-D-xyloside, galactose, glucose, fructose, rhamnose, mannitol, amygdalin, arbutin, salicin, cellobiose, maltose, lactose, melibiose, saccharose, trehalose, raffinose, and gluconate, unlike reference strain

P. oceanisediminis JCM17814

T and

P. dongdonensis KCTC 33221

T, which displayed positive reactions in these tests. Compared with the reference strain

P. dongdonensis KCTC 33221

T, which was positive for H

2S production, hydrolysis of starch, cellulose, Tween 20, 40, and 60, strain ES5-4

T was positive only for H

2S production and hydrolysis of Tween 40 and 60.

P. oceanisediminis JCM17814

T was positive for hydrolysis of starch, cellulose, and Tween 40 and negative for other relative tests (

Table 2).

In the BIOLOG GEN III tests, strain ES5-4

T was positive for α-D-glucose, D-mannose, D-fructose, D-galactose, D-fucose, L-glutamic acid, L-serine, D-galacturonic acid, L-galactomic acid lactone, D-gluconic acid, D-glucuronic acid, glucuronamide, mucic acid, quinic acid, citric acid, and L-malic acid. In comparion,

P. oceanisediminis JCM17814

T was negative for utilization of D-fucose, L-glutamic acid, L-serine, glucuronamide, mucic acid, and citric acid whereas

P. dongdonensis KCTC 33221

T was negative for L-serine and glucuronamide. These differential characteristics among the three strains are summarized in

Table 2.

3.4. Effects of Se4+ Concentration on the Growth of Strain ES5-4T

The effect of Se

4+ concentration on the growth of strain ES5-4

T was investigated using TSB and TSAs. As Se

4+ concentration increased, the cell suspension color changed from yellow to deep orange red and then to light orange red in the TSB (

Figure S3), indicating that the white Se

4+ was converted to red selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) by strain ES5-4

T [

56]. The optical density values at 600 nm (OD

600) were disturbed by the red color caused by SeNPs except for strain concentration caused by Se

4+ solution. Therefore, the values showed a trend of first decreasing, then increasing, and then decreasing again, reaching their maximum at a Se

4+ concentration of 500 mg/L (

Figure S3). The cell colors changed from white to red when strain ES5-4

T grew on TSA (

Figure S4). In addition, with the increase of Se

4+ concentration, the colony diameter seemed to decrease significantly (

p < 0.05) (

Figure 4).

Bacillus sp. KW3,

Corynebacterium sp. VS5, and

Pseudomonas sp. VW7 have been reported to be resistant to Se

4+ above 200 mM [

57]. The minimal inhibitory concentrations of

Lysinibacillus xylanilyticus and L.

macrolides for Se

4+ were 120 and 220 mM, respectively [

58]. Strain ES5-4

T can be resistant to Se

4+ concentration at least 5,000 mg/L, approximately responding to 30 mM.

Besides strain ES5-4

T, many other

Paenibacillus species could also reduce white Se

4+ to red SeNPs. For example,

Paenibacillus selenitireducens ES3-24

T isolated from a selenium mineral soil was able to reduce Se to red elemental selenium [

59]. Long et al. [

60] reported the same function of

Paenibacillus motobuensis LY5201.

SeNPs are versatile in their application, such as antioxidant [

61], antibacterial [

62], anticancer and immunomodulatory [

63], bioremediation [

64], detoxification of heavy metals, nutraceutical functions, as well as the fortification of selenium dietary especially in selenium deficiency areas [

65]. Strain ES5-4

T might also be applicable in the aforementioned aspects. However, this requires further research.

3.5. Genetic Features of Paenibacillus for Selenocompound Metabolism

Given strain ES5-4

T’s resistance to Se

4+, the distribution of the 22 genes involved in selenocompound metabolism was analyzed in the genus

Paenibacillus and 14 genes were detected (

Figure 5, Dataset S1). Genes

trxB/TRR,

metC,

patB/malY,

metE,

MARS/metG,

sufS,

yitJ, and

metH/MTR were almost universal in these strains, with

metH/MTR absent in

Paenibacillus shenyangensis A9.

selD/SEPHS was only present in

P. shenyangensis A9, which catalyzes selenophosphate synthesis using inorganic selenium and ATP as substrates [

66].

metB, which can catalyze selenocysteine to selenocystathionine [

67], was present only in

P. xylanexedens DSM 21292,

P. shenyangensis A9, and

Paenibacillus sp. 1781tsa1. The gene for the reaction (

E4.4.1.11), capable of producing methaneselenol from selenomethionine [

68], was only found in

Paenibacillus sp. FSL W8−0426,

P. silvae CGMCC 1.12770, and strain ES5-4

T (

Figure 5). The thioredoxin reductase gene

trxB/TRR catalyzed selenite (SeO

32-) to hydrogen selenide (H

2Se), which was spontaneously oxidized by oxygen to become Se (0) and eventually formed SeNPs [

69,

70,

71]. Cystathionine-β-lyase coded by

metC catalyzes selenocystathionine to selenohomocysteine [

72,

73]. Together, the results suggest that species in the genus

Paenibacillus were versatile in selenocompound metabolism. Notably, strain ES5-4

T carries two copies of

metC and

trxB/TRR, which likely confers its selenium resistance (

Figure 5).

3.6. Chemotaxonomic Characteristics

The major cellular fatty acids (> 10%) were

anteiso-C

15:0 (46.5%) and C

16:0 (21.7%) for strain ES5-4

T,

iso-C

14:0 (10.1%),

anteiso-C

15:0 (45.6%), and

iso-C

16:0 (20.0%) for

P. oceanisediminis JCM 17814

T and C

16:0 (18.3%), and

anteiso-C

15:0 (50.3%) for

P. dongdonensis KCTC 33221

T (

Table S1). The polar lipids of strain ES5-4

T mainly comprised diphosphatidylglycerol (DPG), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylglycerol (PG), and unidentified polar lipid (PL), which is similar to that of the closely related strain

P. oceanisediminis JCM17814

T (

Figure S5). The predominant respiratory quinone of strain ES5-4

T was MK-7, in conformity to the genus

Paenibacillus [

74,

75].

4. Conclusions

A strain designated ES5-4T was isolated from rhizosphere (with Se content of 3.57 mg/kg) of G. parviflora growing in the selenium-rich ore area of Enshi, Hubei Province, China. 16S rRNA and bac120 gene trees indicated that strain ES5-4T formed a distinct clade in the genus Paenibacillus. The ANI and dDDH values between ES5-4T and its closely related species were below the boundaries for ANI of 95%–96% and dDDH of 70%. Furthermore, strain ES5-4T differed from the reference strains P. oceanisediminis JCM17814T and P. dongdonensis KCTC 33221T in phenotype and chemotaxonomic characteristics, such as growth conditions, motile, starch and cellulose hydrolysis, utilization of some substrates, polar lipids, and cellular fatty acids. Based on these phenotypic, chemotaxonomic and genotypic features, strain ES5-4T can be considered a novel Paenibacillus species, for which the name Paenibacillus hubeiensis sp. nov. is proposed.

Description of Paenibacillus hubeiensis sp. nov.

Paenibacillus hubeiensis (hu. bei. en’sis. N.L. masc. adj. hubeiensis, pertaining to the province of Hubei, where the selenium-rich ore is located, from which the strain was isolated)

The strain (ES5-4T) is Gram-staining positive, motile, aerobic, and rod shaped. The colonies on TSA are milky, circle, moist and smooth after incubation for 3 days at 28°C. The cells can be grown at 4–42 °C (optimum, 28 °C), pH 5.0–10.0 (optimum, 5.0-7.0) and is tolerated to 5% (optimum, 0.5% – 1.0%) of NaCl. It can tolerate up to 5,000 mg/L Se4+ and can produce SeNPs. It is only positive for esculin in the API 50CH analysis. In the BIOLOG GEN III tests, it is positive for 16 types of organic carbon sources. The major fatty acids are anteiso-C15:0 (46.5%) and C16:0 (21.7%). The predominant respiratory quinone is MK-7. The polar lipids mainly comprise diphosphatidylglycerol (DPG), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylglycerol (PG) and an unidentified phospholipid (PL).

The type strain, ES5-4T (= GDMCC 1.3540T = KCTC 43478T), was isolated from the rhizosphere of G. parviflora, collected from a selenium-rich ore area of Enshi, Hubei Province, China (30°8´43´´N 109°49´32´´E). The genomic G + C content of the strain was 50.5%. The 16S rRNA gene sequence and genome were deposited at GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ with the accession number of OR584159 and JAVYAE000000000, respectively.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Maximum-parsimony phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences showing the position of strain ES5-4T. Bootstrap values (expressed as percentages of 1,000 replications) of > 70 (%) are shown at the branch nodes. Bacillus subtilis NCIB 3610T is used as the out group; Figure S2: Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences showing the position of strain ES5-4T. Bootstrap values (expressed as percentages of 1,000 replications) of > 70 (%) are shown at the branch nodes. Bacillus subtilis NCIB 3610T is used as the out group. Figure S3: Effects of Se4+ concentration (20–5,000 mg/L) on the growth of strain ES5-4T cultured in TSB media at 28 ℃ for 2 days; Figure S4: Effects of Se4+ concentration (20–5,000 mg/L) on the growth of strain ES5-4T cultured on TSA media at 28 ℃ for 2 days; Figure S5: Two-dimensional thin-layer chromatogram of polar lipids. Note: a, Paenibacillus enshiensis ES5-4T; b, Paenibacillus oceanisediminis JCM17814T. DPG, diphosphatidylglycerol; PG, phosphatidylglycerol; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PL, unidentified phospholipid; L, unidentified lipid; APL, Unidentified aminophospholipid; Table S1: Cellular fatty acid profiles (% of the totals) of strain ES5-4T and its closely related type strains of the genus Paenibacillus.; Dataset S1: Annotated selenocompound metabolism gene profiles for the genus Paenibacillus.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K, X.L and D.Z.; methodology, C.J and X.P.; software, D.Z; validation, X.L., Y.G. and Q.X.; investigation, Y.S and Z.Z.; resources, Y.S.; data curation, J.K. and Z.F.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K., Z.F. and Y.L.; writing—review and editing, X.L. and D.Z.; visualization, X.L. and D.Z.; supervision, X.L. and D.Z.; funding acquisition, X. L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was founded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (32260033) and Key Projects of Jiangxi Province College Students' Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program, China (202310417002).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files. The 16S rRNA gene sequence of strain ES5-4T was deposited at NCBI database with the accession numbers of OR584159. The whole genome sequence of strain ES5-4T was deposited at GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ with the accession number of JAVYAE000000000.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Aharon Oren for his excellent help with the Latin names. We are also thankful for the editors and anonymous reviewers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANI |

Average nucleotide identity |

| ANIb |

Average nucleotide identity calculated by the alignment algorithms BLAST + |

| APL |

Unidentified aminophospholipid |

| bp |

Base pairs |

| COG |

Cluster of Orthologous Groups |

| dDDH |

The digital DNA–DNA hybridization |

| DPG |

Diphosphatidylglycerol |

| GGDC |

Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator |

| GO |

Gene ontology |

| ICNP |

International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes |

| KEGG |

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| L |

Unidentified lipid |

| MCCC |

Marine Culture Collection of China |

| ME |

Minimum evolution |

| MIDI |

Microbial identification system |

| ML |

Maximum-likelihood |

| NCBI |

National Center of Biotechnology Information |

| NJ |

Neighbor-joining |

| PCR |

Polymerase chain reaction |

| PE |

Phosphatidylethanolamine |

| PG |

Phosphatidylglycerol |

| PGPB |

Plant growth-promoting bacteria |

| PGPR |

Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria |

| PL |

Unidentified phospholipid |

| Se |

Selenium |

| SEM |

Scanning electron microscopy |

| sp. nov |

Species novum |

| TEM |

Transmission electron microscopy |

| TSA |

Trypticase Soy Agar |

| TSB |

Trypticase Soy Broth |

References

- Ash, C.; Priest, F.G.; Collins, M.D. Molecular identification of rRNA group 3 bacilli (Ash, Farrow, Wallbanks and Collins) using a PCR probe test: proposal for the creation of a new genus Paenibacillus. Anton. Leeuw. Int. J. G. 1993, 64, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shida, O.; Takagi, H.; Kadowaki, K.; Nakamura, L.K.; Komagata, K. Transfer of Bacillus alginolyticus, Bacillus chondroitinus, Bacillus curdlanolyticus, Bacillus glucanolyticus, Bacillus kobensis, and Bacillus thiaminolyticus to the genus Paenibacillus and emended description of the genus Paenibacillus. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1997, 47, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.Y.; Ye, X.P.; Hu, Y.Y.; Tang, Z.X.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, T.; Bai, X.L.; Pi, E.X.; Xie, B.H.; Shi, L.E. Exopolysaccharides of Paenibacillus polymyxa: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 261, 129663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, S. Paenibacillus sinensis sp. nov., a nitrogen-fixing species isolated from plant rhizospheres. Anton. Leeuw. Int. J. G. 2022, 115, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Huang, H.W.; Wang, Y.; Kou, Y.R.; Yin, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.Q.; Zhao, G.F.; Zhu, W.Y.; Tang, S.K. Paenibacillus turpanensis sp. nov., isolated from a salt lake of Turpan city in Xinjiang province, north-west China. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, M.B.F.; Lemos, E.A.; Vollú, R.E.; Abreu, F.; Rosado, A.S.; Seldin, L. Paenibacillus piscarius sp. nov., a novel nitrogen-fixing species isolated from the gut of the armored catfish Parotocinclus maculicauda. Anton. Leeuw. Int. J. G. 2022, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.; Reina, J.C.; Béjar, V.; Llamas, I. Paenibacillus lutrae sp. nov., a chitinolytic species isolated from a river otter in castril natural park, Granada, Spain. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, N.; Huang, H.; Hu, Y.; Wang, X.; Mo, K. Paenibacillus arenilitoris sp. nov., isolated from seashore sand and genome mining revealed the biosynthesis potential as antibiotic producer. Anton. Leeuw. Int. J. G. 2022, 115, 1307–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, M.X.; Yin, M.; Zhang, D.Y.; Wang, J.; Miao, Y.M.; Cai, M.; Zhou, Y.G.; Miao, C.P.; Tang, S.K. Paenibacillus thermotolerans sp. nov., isolated from a hot spring in Yunnan Province, south-west China. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2024, 74, 006336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhang, Z.T.L.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, G.Q.; Yin, M.; Li, Y.; Zhu, W.Y.; Tang, S.K. Paenibacillus alkalitolerans sp. nov., a bacterium isolated from a salt lake of Turpan City in Xinjiang Province, north-west China. Folia. Microbiol. 2023, 68, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorat, V.; Kirdat, K.; Tiwarekar, B.; Dhanavade, P.; Karodi, P.; Shouche, Y.; Sathe, S.; Lodha, T.; Yadav, A. Paenibacillus albicereus sp. nov. and Niallia alba sp. nov., isolated from digestive syrup. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kämpfer, P.; Lipski, A.; Lamothe, L.; Clermont, D.; Criscuolo, A.; Mclnroy, J.A.; Glaeser, S.P. Paenibacillus plantiphilus sp. nov. from the plant environment of Zea mays. Anto. Leeuw. Int. J. G. 2023, 116, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Chaudhary, D.K.; Lim, O.B.; Kim, D.U. Paenibacillus agricola sp. nov., isolated from agricultural soil. Arch. Microbiol. 2023, 205, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixit, R.; Agrawal, L.; Gupta, S.; Kumar, M.; Yadav, S.; Chauhan, P.S.; Nautiyal, C.S. Southern blight disease of tomato control by 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) deaminase producing Paenibacillus lentimorbus B-30488. Plant Signal. Behav. 2016, 11, e1113363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Shi, H.; Du, Z.; Wang, T.; Liu, X.; Chen, S. Comparative genomic and functional analysis reveal conservation of plant growth promoting traits in Paenibacillus polymyxa and its closely related species. Sci. Rep.-UK 2016, 6, 21329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, H.; Song, Y.; Wang, M.; Hua, C.; Li, Y.; Chen, S.; Dixon, R.; Li, J. Alanine synthesized by alanine dehydrogenase enables ammonium-tolerant nitrogen fixation in Paenibacillus sabinae T27. P. Natl. ACAD Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2215855119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Choi, SK.; Ryu, C.M.; Park, S.H. Chronicle of a soil bacterium: Paenibacillus polymyxa E681 as a tiny guardian of plant and human health. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.J.; Zhou, D.; Wang, Q.M.; Wang, X.H.; Zhang, W.J.; Zhuang, L.; Wang, X.J.; Yan, L.; Lv, J.; Sheng, J. Paenibacillus puerhi sp. nov., isolated from the rhizosphere soil of Pu-erh tea plants (Camellia sinensis var. assamica). Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 1375–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Tu, Y.; Ma, T.; Jiang, N.; Piao, C.; Li, Y. Taxonomic study of three novel Paenibacillus species with cold-adapted plant growth-promoting capacities isolated from root of Larix gmelinii. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, M.; Jitaru, P.; Barbante, C. Selenium biochemistry and its role for human health. Metallomics 2014, 6, 25–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genchi, G.; Lauria, G.; Catalano, A.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Carocci, A. Biological activity of selenium and its impact on human health. Inter. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2633.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nancharaiah, Y.V.; Lens, P.N.L. Ecology and biotechnology of selenium-respiring bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2015, 79, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.R.; Chen, H.B.; Li, Y.X.; Zhou, Z.H.; Li, J.B.; Wang, Y.Q.; Zhang, H.; Han, Y.H.; Wang, S.S. Priestia sp. LWS1 is a selenium-resistant plant growth-promoting bacterium that can enhance plant growth and selenium accumulation in Oryza sativa L. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yan, Z.; Gu, D.; Li, D.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, D.; Su, L.; Ao, Y. Characterization of cadmium-resistant rhizobacteria and their promotion effects on Brassica napus growth and cadmium uptake. J. Basic Microbiol. 2019, 59, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, J.A.; Reich, C.I.; Sharma, S.; Weisbaum, J.S.; Wilson, B.A.; Olsen, G.J. Critical evaluation of two primers commonly used for amplification of bacterial 16S rRNA genes. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2008, 74, 2461–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.H.; Ha, S.M.; Kwon, S.; Lim, J.; Kim, Y.; Seo, H.; Chun, J. Introducing EzBioCloud: a taxonomically united database of 16S rRNA gene sequences and whole-genome assemblies. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 1613–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, M.A.; Blackshields, G.; Brown, N.P.; Chenna, R.; McGettigan, P.A.; McWilliam, H.; Valentin, F.; Wallace, I.M.; Wilm, A.; Lopez, R.; Thompson, J.D.; Gibson, T.J.; Higgins, D.G. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 2947–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 1980, 16, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felsenstein, J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985, 39, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J. Spongiibacter thalassae sp. nov., a marine gammaproteobacterium isolated from seawater. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurk, S.; Bankevich, A.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Korobeynikov, A.; Lapidus, A.; Prjibelski, A.D.; Pyshkin, A.; Sirotkin, A.; Sirotkin, Y.; Stepanauskas, R.; Clingenpeel, S.R.; Woyke, T.; Mclean, J.S.; Lasken, R.; Tesler, G.; Alekseyev, M.A.; Pevzner, P.A. Assembling single-cell genomes and mini-metagenomes from chimeric MDA products. J. Comput. Biol. 2013, 20, 714–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonechnikov, K.; Golosova, O.; Fursov, M.; Team, U. Unipro UGENE: a unified bioinformatics toolkit. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1166–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Auch, A.F.; Klenk, H.P.; Goker, M. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatusova, T.; DiCuccio, M.; Badretdin, A.; Chetvernin, V.; Nawrocki, E.P.; Zaslavsky, L.; Lomsadze, A.; Pruitt, K.D.; Borodovsky, M.; Ostell, J. NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic. Acids Res. 2016, 44, 6614–6624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantalapiedra, C.P.; Hernández-Plaza, A.; Letunic, I.; Bork, P.; Huerta-Cepas, J. eggNOG-mapper v2: functional annotation, orthology assignments, and domain prediction at the metagenomic scale. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 5825–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, D.H.; Chuvochina, M.; Waite, D.W.; Rinke, C.; Skarshewski, A.; Chaumeil, P.A.; Hugenholtz, P. A standardized bacterial taxonomy based on genome phylogeny substantially revises the tree of life. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 996–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE v5 enables improved estimates of phylogenetic tree confidence by ensemble bootstrapping. BioRxiv 2021, 2021–06. [Google Scholar]

- Price, M.N.; Dehal, P.S.; Arkin, A.P. FastTree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2009, 26, 1641–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.F.; He, W.; Shao, Z.; Ahmed, I.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.J.; Zhao, Z. EasyCGTree: a pipeline for prokaryotic phylogenomic analysis based on core gene sets. BMC bioinformatics 2023, 24, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, D.; Yan, Z.; Ao, Y. Biosorption and bioaccumulation characteristics of cadmium by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 30902–30911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhao, Z.; Xiao, Q.; He, N.; Kong, J.; Zhang, D.; Li, R.; Shao, Q. Potential application of Curtobacterium sp. GX_31 for efficient biosorption of Cadmium: Isotherm and kinetic evaluation. Environ. Technol. Inno. 2023, 30, 103122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasser, M. Identification of bacteria by gas chromatography of cellular fatty acids: MIDI technical Note 1990, 101. MIDI inc, Newark, DE.

- Collins, M.D.; Jones, D. Distribution of isoprenoid quinone structural types in bacteria and their taxonomic implication. Microbiol. Rev. 1981, 45, 316–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minnikin, D.E.; O'donnell, A.G.; Goodfellow, M.; Alderson, G.; Athalye, M.; Schaal, A.; Parlett, J.H. An integrated procedure for the extraction of bacterial isoprenoid quinones and polar lipids. J. Microbiol. Meth. 1984, 2, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komagata, K.; Suzuki, K.I. 4 Lipid and cell-wall analysis in bacterial systematics. Method. Microbiol. 1988, 19, 161–207. [Google Scholar]

- He, W.; Xue, H.P.; Liu, C.; Zhang, A.H.; Huang, J.K.; Zhang, D.F. Biomineralization of struvite induced by indigenous marine bacteria of the genus Alteromonas. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1085345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramaki, T.; Blanc-Mathieu, R.; Endo, H.; Ohkubo, K.; Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S.; Ogata, H. Kofam KOALA: KEGG Ortholog assignment based on profile HMM and adaptive score threshold. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 2251–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.F.; He, W.; Shao, Z.; Ahmed, I.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.J.; Zhao, Z. EasyCGTree: a pipeline for prokaryotic phylogenomic analysis based on core gene sets. BMC Bioinformatics 2023, 24, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.S.; Kang, H.U.; Ghim, S.Y. Paenibacillus dongdonensis sp. nov., isolated from rhizospheric soil of Elymus tsukushiensis. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 2865–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, F.L.; Tien, C.J.; Tai, C.J.; Wang, L.T.; Liu, Y.C.; Chern, L.L. Paenibacillus taichungensis sp. nov., from soil in Taiwan. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2008, 58, 2640–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghio, S.; Sauka, D.H.; Ferrari, A.E.; Piccini, F.E.; Ontañon, O.M.; Campos, E. Paenibacillus xylanivorans sp. nov., a xylan-degrading bacterium isolated from decaying forest soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2019, 69, 3818–3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, M.; Rosselló-Móra, R. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 19126–19131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goris, J.; Konstantinidis, K.T.; Klappenbach, J.A.; Coenye, T.; Vandamme, P.; Tiedje, J.M. DNA-DNA hybridization values and their relationship to whole-genome sequence similarities. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Shi, K.; Wang, X.; Fan, J.; Wang, R.; Zheng, S.; Wang, G. Paenibacillus flagellatus sp. nov., isolated from selenium mineral soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2019, 69, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Llamosas, H.; Castro, L.; Blazquez, M.L.; Diaz, E.; Carmona, M. Biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles by Azoarcus sp. CIB. Microb. Cell Fact. 2016, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton Jr, G.A.; Giddings, T.H.; DeBrine, P.; Fall, R. High incidence of selenite-resistant bacteria from a site polluted with selenium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1987, 53, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Shao, Z.; Li, J.; Zan, S.; Zhou, S.; Yang, R. Two selenium tolerant Lysinibacillus sp. strains are capable of reducing selenite to elemental Se efficiently under aerobic conditions. J. Environ. Sci. 2019, 77, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R.; Wang, R.; Wang, D.; Su, J.; Zheng, S.; Wang, G. Paenibacillus selenitireducens sp. nov., a selenite-reducing bacterium isolated from a selenium mineral soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol 2014, 64(Pt_3), 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Q.; Cui, L.K.; He, S.B.; Sun, J.; Chen, Q.Z.; Bao, H.D.; Liang, T.Y.; Liang, B.Y.; Cui, L.Y. Preparation, characteristics and cytotoxicity of green synthesized selenium nanoparticles using Paenibacillus motobuensis LY5201 isolated from the local specialty food of longevity area. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Qiao, L.; Ma, L.; Yan, S.; Guo, Y.; Dou, X.; Zhang, B.H.; Roman, A. Biosynthesis of polysaccharides-capped selenium nanoparticles using Lactococcus lactis NZ9000 and their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvi, G.B.; Iqbal, M.S.; Ghaith, M.M.S.; Haseeb, A.; Ahmed, B.; Qadir, M.I. Biogenic selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) from citrus fruit have anti-bacterial activities. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khurana, A.; Tekula, S.; Saifi, M.A.; Venkatesh, P.; Godugu, C. Therapeutic applications of selenium nanoparticles. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 111, 802–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.; Tan, J.; Li, M.; Yuan, Z.; Zhou, H. The mechanism of Se(IV) multisystem resistance in Stenotrophomonas sp. EGS12 and its prospect in selenium-contaminated environment remediation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 452, 131358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Yao, P.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Xin, N.; Wei, H.; Zhang, T.H.; Zhao, C. Selenium nanoparticles: Enhanced nutrition and beyond. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 12360–12371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, J.; Kang, D.; Jung, J.; Yoo, T.J.; Shim, M.S.; Gladyshev, V.N.; Tsuji, P.A.; Hatfield, D.L.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, B.J. SEPHS1: Its evolution, function and roles in development and diseases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2022, 730, 109426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shen, P.; Lan, Q.; Deng, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wei, W.; Wang, Y.; Su, N.; He, F.; Xie, Q.; Lyu, Z.; Yang, D.; Xu, P. High-coverage proteomics reveals methionine auxotrophy in Deinococcus radiodurans. Proteomics 2017, 17, 1700072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipp, T.M.; Gemoth, L.; Will, A.; Schwarz, M.; Ohse, V.A.; Kipp, A.P.; Steinbrenner, H.; Klotz, L.O. Selenium-binding protein 1 (SELENBP1) is a copper-dependent thiol oxidase. Redox Biol. 2023, 65, 102807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustacich, D.; Powis, G. Thioredoxin reductase. Bioch. J. 2000, 346, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarze, A.; Dauplais, M.; Grigoras, I.; Lazard, M.; Ha-Duong, N.T.; Barbier, F.; Blanquet, S.; Plateau, P. Extracellular production of hydrogen selenide accounts for thiol-assisted toxicity of selenite against Saccharomyces cerevisiae . J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 8759–8767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Li, T.; Huang, X.; Zhu, K.; Li, Z.; Dong, Y.; Wang, L.; Huang, J. Advances in the study of selenium-enriched probiotics: from the inorganic Se into Se nanoparticles. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2023, 67, 2300432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, M.; van Doesburg, W.; Rutten, G.A.; Marugg, J.D.; Alting, A.C.; van Kranenburg, R.; Kuipers, O.P. Molecular and functional analyses of the metC gene of Lactococcus lactis, encoding cystathionine β-lyase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou Seeda, M.A.; Abou El-Nour, A.A.; El-Bassiouny, M.S.; Abdallah, M.S.; El-Monem, A.A.S. Middle East J. Agric. Res. 2025, 14, 213–283.

- Lee, H.J.; Shin, S.Y.; Whang, K.S. Paenibacillus pinistramenti sp. nov., isolated from pine litter. Anton. Leeuw. Int. J. G. 2020, 113, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Chaudhary, D.K.; Kim, D.U. Paenibacillus gyeongsangnamensis sp. nov., isolated from soil. J. Microbiol. Biotechn. 2024, 34, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).