Submitted:

11 June 2025

Posted:

12 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Chapter 1. Introduction

1.0. Background

1.1. Problem Statement

1.2. Research Objectives

1.2.1. Main Objective

1.2.2. Specific Objectives

- □

- To investigate the impact of crop diversification on crop productivity among smallholder farmers in Malawi.

- □

- To investigate the impact of crop variety on crop productivity among smallholder farmers in Malawi.

- □

- To investigate the effect of fertilizers type on crop productivity among smallholder farmers in Malawi.

1.3. Hypotheses of the Study

- □

- H0: There is no significant impact of crop diversification on crop productivity.

- □

- H0: Crop variety has no significant impact on crop productivity.

- □

- H: Fertilizer type has no significant impact on crop productivity.

1.4. Significance of the Study

Chapter 2. Literature Review

2.0. Introduction

2.1. The Theoretical Review

2.1.1. Human Capital Theory

2.1.2. Diffusion of Innovation Theory

2.1.3. Risk Management Theory

2.1.4. Agricultural Innovation System Theory

2.2. The Empirical Review

Chapter 3. Methodology

3.0. Introduction

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Model Specification

3.3. Logit Model

3.4. Specification

3.5. Descriptive Variables

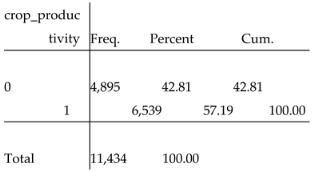

3.5.1. Dependent Variable

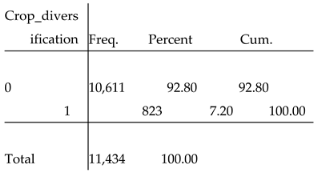

3.5.2. Independent Variables Crop Diversification

Type of Fertilizer

Educational Level

Age of the Household Head

Gender of the Household Head

Residence

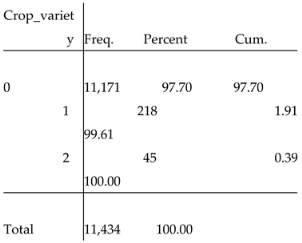

Crop Variety

Farm Asset Ownership

3.6. Summary of Expected Results

| Variables | Parameters | Expected signs |

| Type of fertilizer | Β1 | +/- |

| Crop diversification | Β2 | + |

| Farm asset ownership | Β3 | + |

| Education level | Β4 | +/- |

| Gender | Β5 | +/- |

| Residence | Β6 | +/- |

| Crop variety | Β7 | +/- |

| Age of the household head | Β8 | +/- |

| Household size | Β9 | +/- |

3.7. Diagnostic Test of the Study

3.7.1. Multicollinearity

3.7.2. Goodness of Fit

3.7.3. Specification Error Test

Chapter Four. Presentation and Interpretation of Results

4.0. Introduction

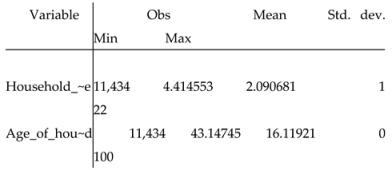

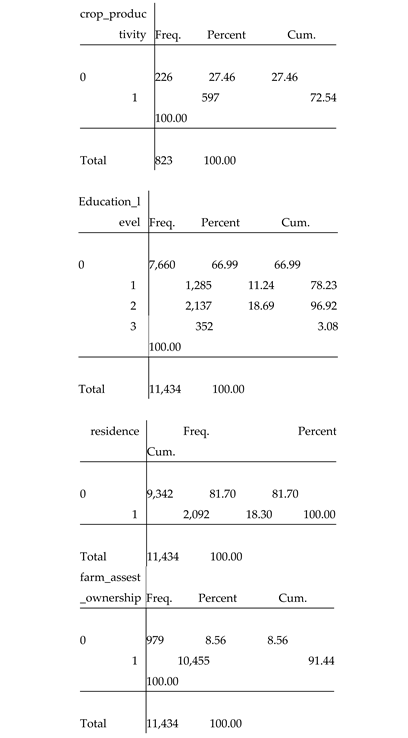

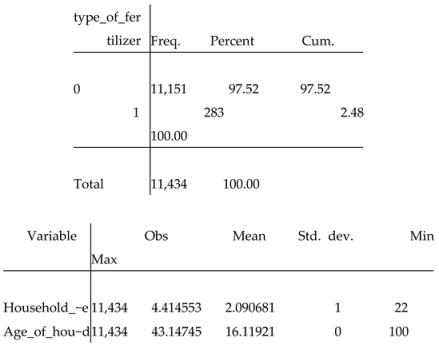

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Interpretation of Diagnostic Test Results

4.2.1. Goodness of Fit

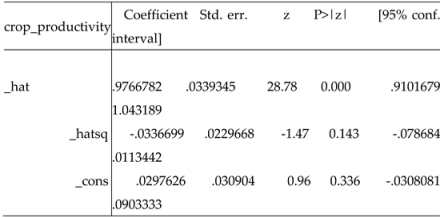

4.2.2. Model Specification (Link Test)

| Crop productivity | Coefficient | St. Err | Z | P > Z |

| _hat | .9766782 | .0339345 | 28.78 | 0.000 |

| _hatsq | -.0336699 | .0229668 | -1.47 | 0.143 |

| _cons | .0297626 | .030904 | 0.96 | 0.336 |

4.2.3. Multicollinearity

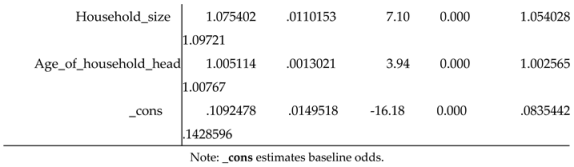

4.2.3. Logistic Regression Results

| VARIABLE NAME | ODDS RATIO | STARDARD ERROR | P >lZl |

| 1.Crop diversification | 1.579899 | 0.1323695 | 0.000 |

| Education level 1 2 3 |

1.201414 1.180082 .6490852 |

.081403 .069531 .090072 |

0.007 0.005 0.002 |

| 1.Residence | 0.2883387 | .0178248 | 0.000 |

| 1.Type of fertilizer | 2.307225 | .3662279 | 0.000 |

| Crop variety 1 2 |

1.118876 .2537731 |

.1724968 .0820529 |

0.466 0.000 |

| 1.Farm asset ownership | 9.087947 | 1.087782 | 0.000 |

| 1.Gender of the household | 1.048592 | .0483432 | 0.303 |

| House size | 1.075402 | .0110153 | 0.000 |

| Age of household head | 1.005114 | .0013021 | 0.000 |

| Constant | .1092478 | .0149518 | 0.000 |

4.3. Statistical Interpretation of Variables

4.3.1. Crop Diversification

4.3.2. Education Level

4.3.3. Residence

4.3.4. Type of Fertilizer

4.3.5. Crop Variety

4.3.6. Farm Asset Ownership

4.3.7. Gender of Household Head

4.3.8. Household Size

4.3.9. Age of Household Head

4.3.10. Constant

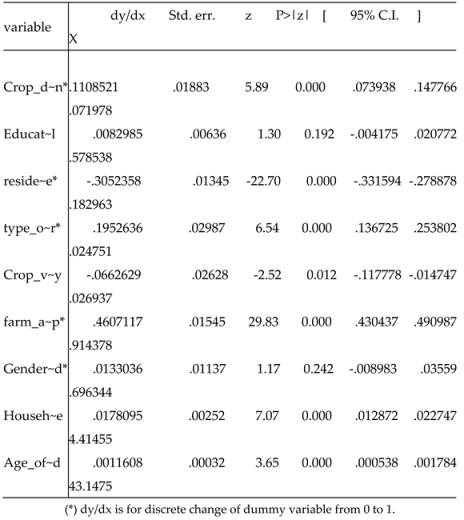

4.4. Marginal Effects After the Logistic Regression

Chapter Five. Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

5.0. Introduction

5.1. Summary and Conclusion

5.2. Policy recommendation

- Guidance on Crop Selection: Extension officers should provide tailored advice to farmers on crop selection, emphasizing high-yielding crops that align with the local agro-ecological conditions. For instance, agriculture scientists should guide smallholder farmers on which crops they should crop with regards to the type of soil, weather conditions and persists of the crop from pests and diseases.

- Strengthen Credit Facilities: Establishing farmer-friendly credit systems can enable smallholder farmers to invest in productive inputs, such as fertilizers and machinery. This can be done by introducing sub-group of smallholder farmers in different regions of Malawi to borrow them money that can be used to accommodate farming activities in order to enhance productivity.

- Promote Labor-Saving Technologies: Introducing affordable labour-saving technologies can help smallholder farmers address labour shortages and improve efficiency. For instance, introducing hire purchase on agricultural inputs that will help farmers in enhancing crop productivity.

- Encourage Regional Collaboration: Collaboration between regions can help farmers share knowledge, resources, and best practices to improve productivity across Malawi. This will help farmers to share insight of how they can navigate different farm problem and increase productivity.

5.3. Limitations and Area for Further Study

List of Acronyms Andabbreviations

| ASWAP agriculture Sector Wide Approach |

| CA Conservation Agriculture |

| CDI Crop Diversification Index |

| CPI Crop Productivity Index |

| FAO Food and Agriculture Organization |

| GDP Gross Domestic Product |

| GoM Government of Malawi |

| IFPRI International Food Policy Research Institute |

| IHS5 Fifth Integrated Household Survey |

| IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| MVAC Malawi Vulnerability Assessment Committee |

| NGO Non-Governmental Organization |

| NSO National Statistical Office |

| OECD Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| SADC Southern African Development Community |

| SSA Sub-Saharan Africa |

| UNDP United Nations Development Programme |

APPENDICES

APPENDIX A: Summary Statistics for Categorical and Continuous Variables

APPENDIX B: Correlation Matrix of a Logistic Regression

| crop_p~y Crop_d~n Educat~l reside~e type_o~r Crop_v~y farm_a~p Gender~d Househ~e Age_of~d | |

| crop_produ~y | 1.0000 |

| Crop_diver~n | 0.0864 1.0000 |

| Education_~l | -0.1220 -0.0261 1.0000 |

| residence | -0.2982 -0.0837 0.3699 1.0000 |

| type_of_fe~r | 0.0775 0.0210 -0.0287 -0.0623 1.0000 |

| Crop_variety | 0.0056 0.0089 -0.0355 -0.0507 0.1231 1.0000 |

| farm_asses~p Gender_of_~d | 0.3000 0.0659 -0.2180 -0.3799 0.0447 0.0413 1.0000 -0.0013 0.0242 0.1915 0.0715 0.0440 -0.0056 -0.0396 1.0000 |

| Household_~e | 0.1132 0.0377 -0.0420 -0.0445 0.0648 0.0128 0.1502 0.1582 1.0000 |

| Age_of_hou~d | 0.0915 0.0352 -0.1780 -0.0993 0.0174 0.0245 0.1661 -0.1435 0.0865 1.0000 |

APPENDIX C: Goodness of Fit of the Logistic Regression

APPENDIX D: Model Specification

APPENDIX E: Logistic Regression Results

APPENDIX F: Marginal Effects After Logistic

References

- Asfaw, S., Lipper, L., McCarthy, N., & Cattaneo, A. (2018). Climate-smart agriculture: Enhancing resilience, productivity, and livelihoods. World Development, 108, 149157.

- Bandron, J., Smith, P., & others. (2015). Comparative performance of conservation agriculture and current smallholder farming practices. Journal of Agricultural Systems, 142, 85-97.

- Becker, G. S. (1964). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. University of Chicago Press. [CrossRef]

- Boehlje, M., & Lins, D. (1998). Risk and risk management in agriculture. Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics, 30(2), 367-383.

- DFID. (1999). Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets. Department for International Development.

- FAO. (2018). Agricultural Development Economics Policy Brief 2. Rome, Italy: FAO.

- FAO. (2021). The State of Food and Agriculture. Food and Agriculture Organization.

- Fisher, M., & Kandiwa, V. (2014). Can agricultural input subsidies reduce the gender gap in modern maize adoption? Evidence from Malawi. Food Policy, 45, 101-111. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, C. (1987). Technology policy and economic performance: Lessons from Japan. Pinter.

- Hall, A., Sulaiman, R. V., Clark, N., & Yoganand, B. (2006). From measuring impact to learning institutional lessons: An innovation systems perspective on improving the management of international agricultural research. Agricultural Systems, 78(2), 213241. [CrossRef]

- Hardaker, J. B., Huirne, R. B. M., Anderson, J. R., & Lien, G. (2004). Coping with risk in agriculture. CABI Publishing.

- IPCC. (2020). Climate change and land: An IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems.

- Kilelu, C. W., Klerkx, L., Leeuwis, C., & Hall, A. (2013). Beyond knowledge brokerage: An exploratory study of innovation intermediaries in an evolving smallholder agricultural system in Kenya. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 19(6), 437-453.

- Klerkx, L., Van Mierlo, B., & Leeuwis, C. (2012). Evolution of systems approaches to agricultural innovation: Concepts, analysis and interventions. In Darnhofer, I., Gibbon, D., & Dedieu, B. (Eds.), Farming systems research into the 21st century: The new dynamic (pp. 457-483). Springer.

- Lin, B. B. (2011). Resilience in agriculture through crop diversification: Adaptive management for environmental change. Bioscience, 61(3), 183-193. [CrossRef]

- Lundvall, B.-Å. (1992). National systems of innovation: Towards a theory of innovation and interactive learning. Pinter.

- Makate, C., Wang, R., Makate, M., & Mango, N. (2016). Crop diversification and livelihoods of smallholder farmers in Zimbabwe: Adaptive management for environmental change. SpringerPlus, 5(1), 1135. [CrossRef]

- Manda, J., Alene, A. D., Gardebroek, C., Kassie, M., & Tembo, G. (2016). Adoption and impacts of sustainable agricultural practices on maize yields and incomes: Evidence from rural Zambia. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 67(1), 130-153. [CrossRef]

- Minot, N., Smale, M., Eicher, C., Jayne, T. S., & Maredia, M. (2020). Seed and fertilizer technology. In Agriculture and rural development in Malawi (pp. 101-129). World Bank Group.

- Ministry of Agriculture Malawi. (2020). Annual Agriculture Production Estimate Survey (APES) report 2020.

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press.

- Rogers, E. M. (1962). Diffusion of innovations. Free Press.

- Saraswati, P., & Bhat, A. (2011). Crop diversification in Karnataka: An economic analysis. Agricultural Economics Research Review, 24(2), 351-357.

- Schultz, T. W. (1961). Investment in human capital. American Economic Review, 51(1), 1-17.

- Southern African Development Community (SADC). (2012). Agriculture and food security. Gaborone, Botswana.

- Spielman, D. J., Ekboir, J., & Davis, K. (2011). The art and science of innovation systems inquiry: Applications to Sub-Saharan African agriculture. Technology in Society, 33(4), 399-410. [CrossRef]

- Thapa, G., & Gaiha, R. (2014). Smallholder farming in developing countries: A global perspective. European Journal of Development Research, 26(1), 10- 28.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2009). Human development report Malawi. Lilongwe: UNDP.

- World Bank. (2012). Agricultural innovation systems: An investment sourcebook. World Bank.

- World Bank. (2020). Employment in agriculture.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).