Submitted:

12 June 2025

Posted:

12 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Problem of Quantum Gate Homogenization

2.1. Quantum Program Analysis

2.2. Quantum Program Synthesis

2.3. Transpilation

2.4. Quantum Hardware Construction and Calibration

2.5. Theoretical Understanding and Generalization

3. Theoretical Foundations: Lie Groups and Representations

3.1. Lie Groups and Their Relevance to Quantum Gates

3.2. Lie Algebras: The Generators of Quantum Gates

- Unitary Condition: If U is unitary, . Taking the derivative with respect to a parameter t of a path with , we get , which simplifies to . This means is anti-Hermitian.

- Infinitesimal Generator: Let be an infinitesimal generator. Since A is anti-Hermitian, we can write where H is Hermitian ().

- Finite Transformation: A finite transformation U can be approximated as . Iterating this, . This is the exponential map from the Lie algebra to the Lie group.

- Determinant Condition: For , we require . The property implies that if , then , which in turn means [24]. Thus, Hermitian and traceless operators are the generators for .

3.3. Representations and the Decomposition of Hilbert Space

Explicit Calculation Example: Single Qubit (Fundamental Representation of SU(2))

Explicit Calculation Example: Two Qubits (Tensor Product and Decomposition)

- Singlet (, dimension 1):

- Triplet (, dimension 3):

3.4. Examples of Important Lie Groups and Representations for Quantum Computing

- : As discussed, this is the fundamental group for single-qubit operations. Its irreducible representations (spin-j multiplets, with dimension ) directly correspond to the states of single qubits (, duplet) and the symmetry properties of multi-qubit systems (singlets, triplets, etc., from spin addition) [5].

- : This is the overarching group for all N-qubit unitary operations. The universal gate set theorems (e.g., Solovay-Kitaev, Section 5.1) essentially state that a finite set of specific gates generates a dense subset of this group, making it accessible for universal quantum computation [24].

- Symplectic Group (): This group is crucial for Continuous Variable Quantum Computing (CVQC). It describes linear canonical transformations in phase space, which correspond to Gaussian operations (like squeezing, displacement, and beam splitters) in CVQC. These operations preserve the Gaussian nature of states, making the natural group for understanding a significant class of CVQC algorithms [22].

- Heisenberg Group: Closely related to the Symplectic group, the Heisenberg group encapsulates the canonical commutation relations between position and momentum operators. Its representations are fundamental for describing the quantum states of bosonic modes and for understanding the quantum mechanics of continuous variables.

- Other Lie Groups: Depending on the physical system or the type of symmetry, other Lie groups may become relevant. For example, for qudits, or specific point groups and space groups for analyzing molecular or condensed matter systems that exhibit discrete spatial symmetries within a larger Lie group framework [4,21].

4. Homogenizing Single-Qubit Gates with SU(2)

4.1. The Single Qubit as the Fundamental Representation of SU(2)

- Pauli-X (X): This is a -rotation about the x-axis. Here, . . Qiskit’s X gate is . This difference is a global phase of i, which is physically irrelevant.

- Pauli-Z (Z): This is a -rotation about the z-axis. Here, . . Qiskit’s Z gate is . Again, a global phase of i.

- Hadamard (H): The Hadamard gate transforms the basis states as and . Its matrix is . This can be expressed as a rotation by around the axis (i.e., the axis bisecting X and Z on the Bloch sphere), or as a sequence of rotations: (up to global phase) [24].

4.2. Geometric Homogenization via the Bloch Sphere and SO(3)

- Vector Space of Hermitian Traceless Matrices: Consider the real vector space . This space is isomorphic to , with a basis given by the Pauli matrices: . Any vector (representing a point on the Bloch sphere) can be mapped to .

- Adjoint Action: For any , define an action on by conjugation: . It can be shown that is also a Hermitian, traceless matrix, so it can be written as for some new vector .

- Orthogonal Transformation: The mapping is a linear transformation that preserves the Euclidean norm , and thus . One can further show that , so .

- Homomorphism and Kernel: The map is a group homomorphism from to . The kernel of this homomorphism, i.e., the elements U for which is the identity rotation, are precisely I and . This establishes the 2-to-1 covering map and the isomorphism [4].

4.3. Euler Angle Decomposition for Practical Homogenization

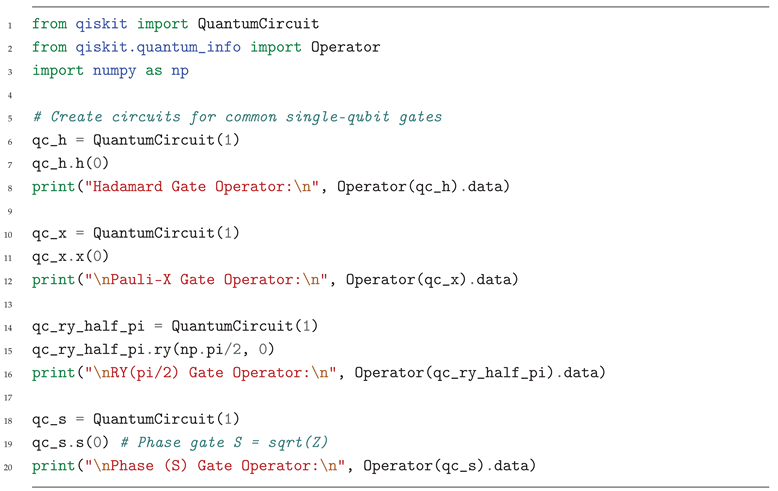

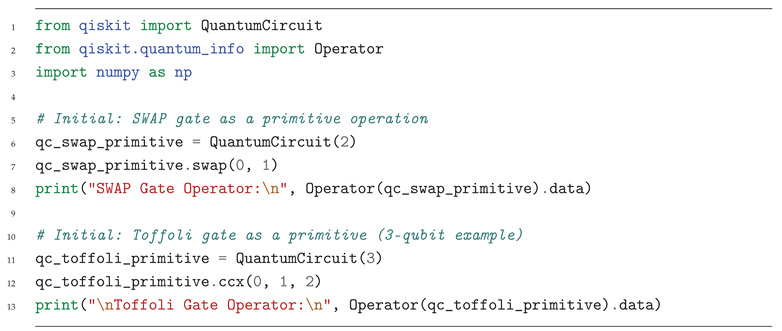

Initial Situation (Common View)

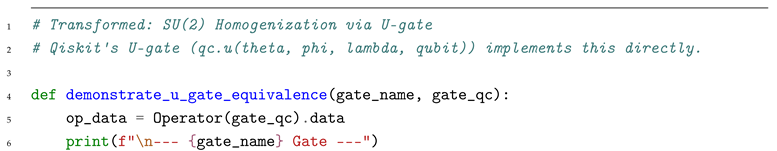

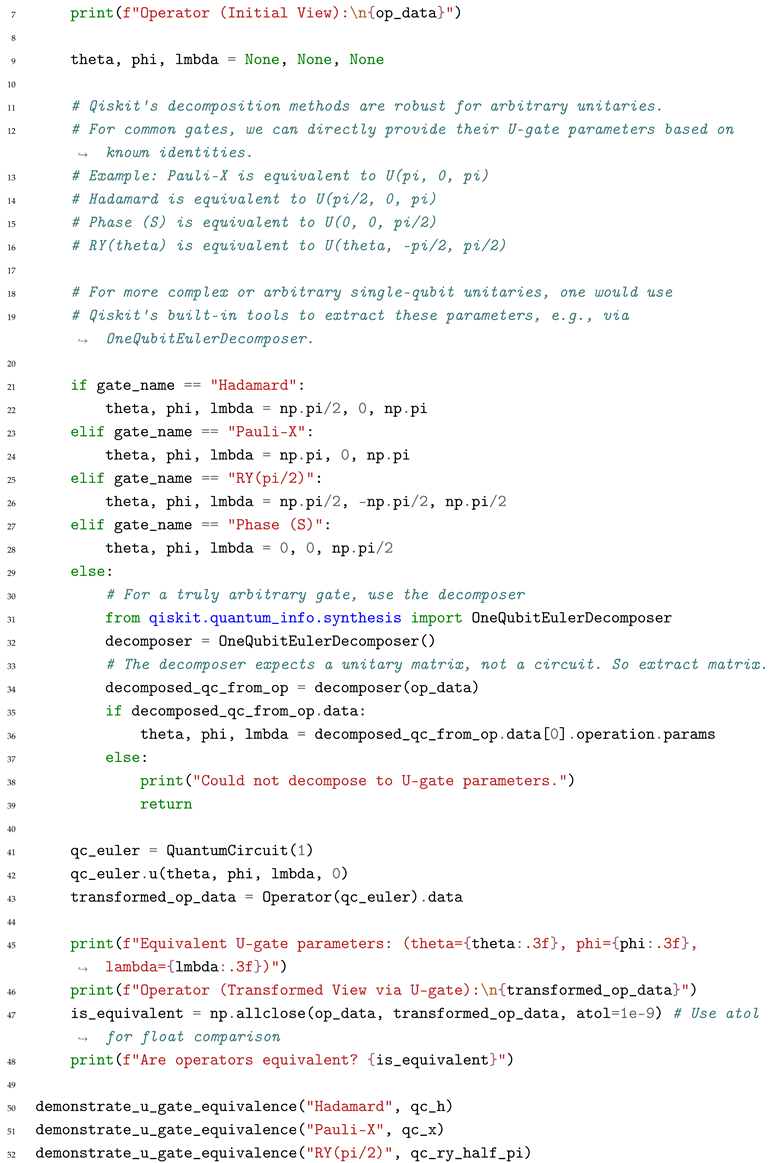

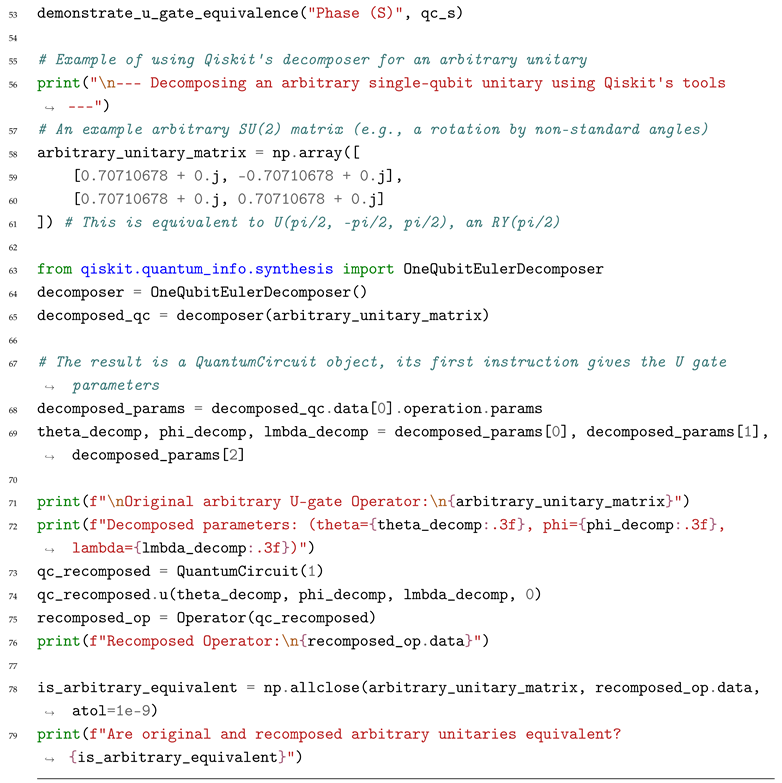

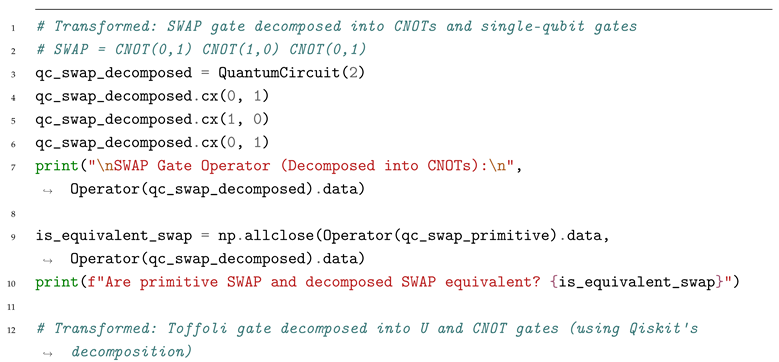

Transformed Situation (SU(2) Homogenization - Euler Angle Decomposition)

5. Homogenizing Multi-Qubit Gates with SU()

5.1. Universal Gate Sets: Homogenization by Approximation and Decomposition

- Density (Lie Algebra Generation): The initial step involves showing that the given universal gate set is "dense" in . This is often achieved by demonstrating that the Lie algebra generated by the infinitesimal forms of the gates in (i.e., their generators) spans the entire Lie algebra . If the generators of a set of gates span the entire Lie algebra, then any element of the Lie group can be approximated by exponentiating elements from this algebra, which translates to composing the gates [24]. For example, the Lie algebra for N qubits is spanned by all tensor products of Pauli matrices and the identity operator. A universal gate set, such as , allows one to effectively generate any element in this Lie algebra through commutators and Lie products (e.g., or ), which then can be exponentiated to form any desired unitary [24]. This establishes the algebraic reachability within the Lie group.

- Recursive Approximation (Group Elements): The core of the Solovay-Kitaev algorithm involves a recursive procedure. If we have an approximation to a target unitary U with error , we aim to find a better approximation with error . This is achieved by finding elements such that their commutator is close to the identity. By carefully selecting and their inverses, one can construct an element that is closer to the identity. The theorem then relies on a "balanced product" technique where one approximates by a product of commutators of elements from , ensuring that the approximation error decreases quadratically at each recursive step, leading to the efficient polylogarithmic scaling [24].

- Complexity Scaling: The logarithmic scaling of the gate sequence length (L) with inverse error () is a remarkable feature, guaranteeing efficient approximation. This is a vast improvement over naive approximation strategies which might scale polynomially or exponentially [27,28]. The Solovay-Kitaev algorithm provides not just the existence but a constructive method for this homogenization, making it a cornerstone for efficient compilation strategies.

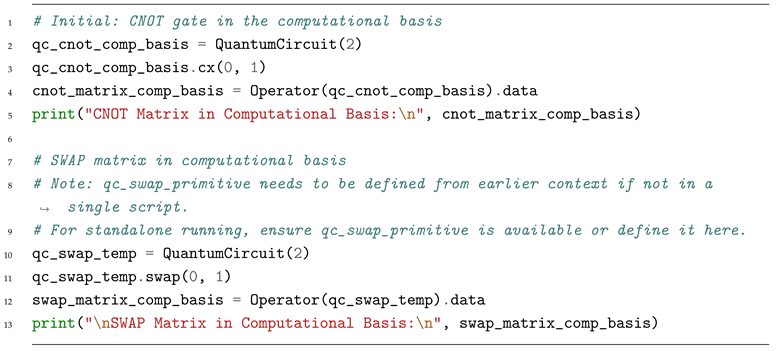

Initial Situation (Common View)

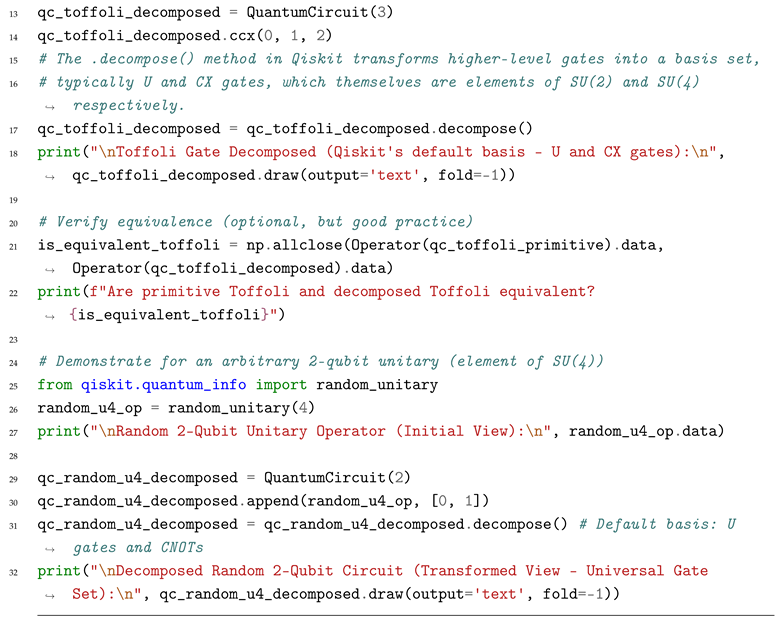

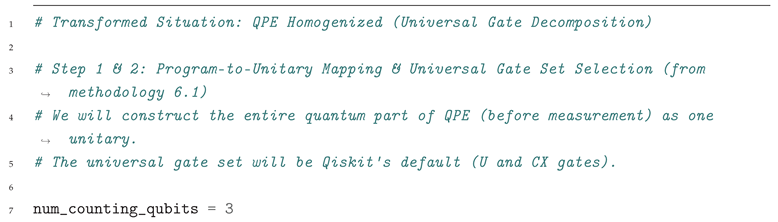

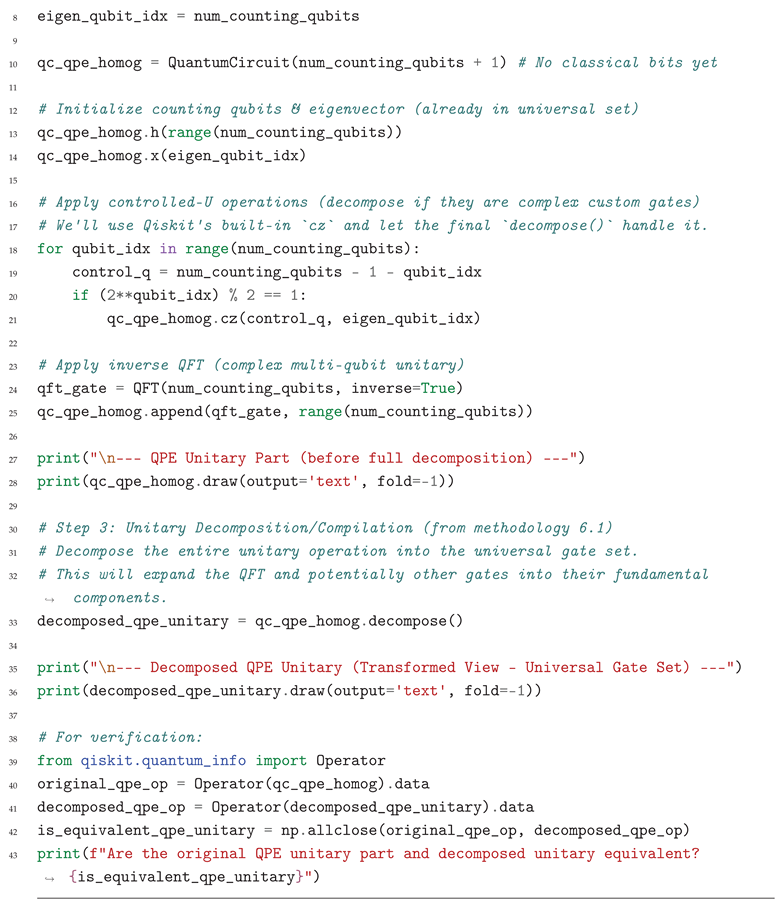

Transformed Situation (SU() Homogenization - Universal Gate Decomposition)

5.2. Multiplets and Symmetry Homogenization (Irreducible Representations)

- Singlet (, dimension 1):

- Triplet (, dimension 3):

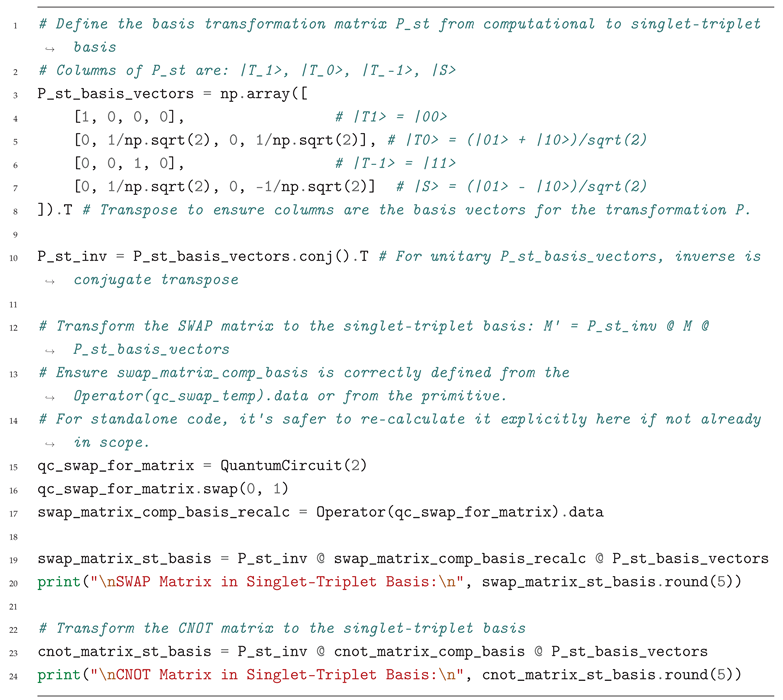

Initial Situation (Common View)

Transformed Situation (Multiplet Homogenization - Block-Diagonalization)

5.3. Reinterpreting Superposition and Entanglement through Irreducible Representations

- Superposition Reinterpreted: For a single qubit, any arbitrary superposition state (where ) is simply an element within the fundamental (spin-1/2, or duplet) irreducible representation of . Geometrically, every pure superposition state maps to a unique point on the Bloch sphere, which is a visual representation of this 2-dimensional irreducible space. The linearity of quantum mechanics naturally means that any superposition of basis states is itself a valid vector within this irreducible representation space. There’s no "mixing" across different irreps in this single-qubit context because the space itself is the fundamental irrep. This provides a homogeneous understanding of all pure single-qubit states, treating them as points in a single, well-defined mathematical space [5].

-

Entanglement Reinterpreted: The true power of this reinterpretation becomes profoundly evident with entanglement, particularly when considering multi-qubit systems. As shown in Section 5.2, the 4-dimensional Hilbert space of two qubits, , decomposes into a 1-dimensional singlet (spin-0) and a 3-dimensional triplet (spin-1) irreducible representation of the total spin . Crucially, the maximally entangled Bell states directly form a basis for these irreducible subspaces (or are elements within them):

- -

- Singlet (Spin-0, total angular momentum ):

- -

-

Triplet (Spin-1, total angular momentum ):

- ()

- ()

- ()

While often presented as "the four Bell states," these are directly the singlet and specific triplet states (note: two of the canonical Bell states are actually the and states, and the other two, and , are linear combinations of and states, or are related via local operations).From this perspective, entanglement is not merely "spooky action at a distance" but rather the manifestation of quantum states belonging to specific irreducible subspaces that cannot be factored into product states. A product state like is an element of the triplet subspace, but a superposition like (if not normalized properly) might span multiple irreps. However, a maximally entangled state like is a pure element of the singlet irrep, meaning no local operation can transform it into a product state. This deep structural property directly leads to entanglement. Product states, conversely, are elements of the composite Hilbert space that can be written as tensor products of individual qubit states; they are typically not pure elements of a single high-dimensional irrep of the total spin group, but rather live in superpositions across multiple irreps or are specific components within them.Entangling gates, like the CNOT, gain a deeper meaning when viewed through this lens. They are operations that take product states (or states easily expressed as products) and transform them into states that reside purely within these irreducible entangled subspaces. For instance, CNOT applied to yields (a triplet state). Applying CNOT to a superposition like then produces the entangled Bell state , which is an element of the triplet subspace. The CNOT matrix’s non-block-diagonal form in the singlet-triplet basis (as seen in the practical example above) directly reflects its ability to mix different components of the Hilbert space that transform differently under total spin symmetry. This mixing capability is precisely what allows CNOT to generate entanglement, creating states that are pure elements of irreducible, inseparable representations of the combined system. This reinterpretation deeply homogenizes our understanding of entanglement, grounding it in the fundamental symmetries of the underlying Lie group and its representation theory.

6. Methodology for Homogenizing Quantum Programs

6.1. Discrete Variable (Qubit/Qudit) Systems

6.2. General Lie Group Systems

7. Examples of Homogenized Quantum Programs

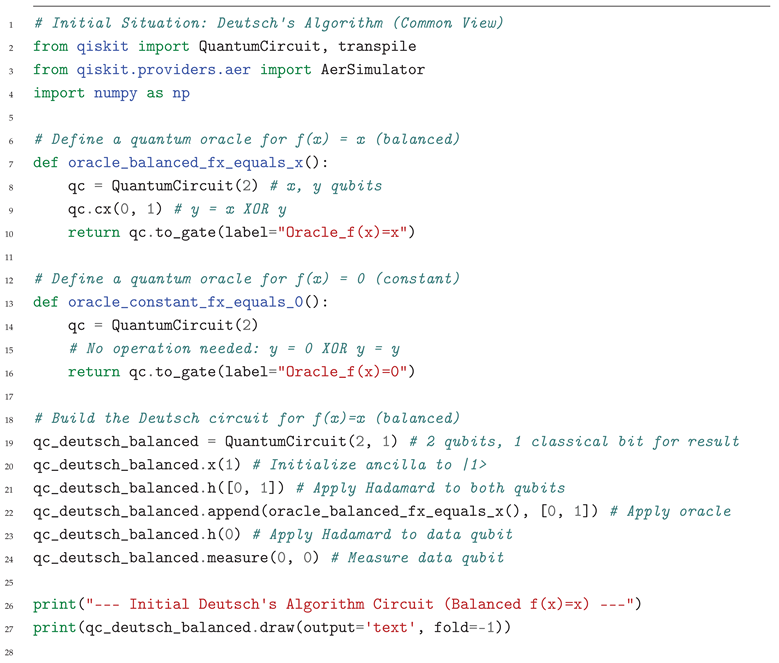

7.1. Example 1: Deutsch’s Algorithm

Initial Situation (Common View - Qiskit Program)

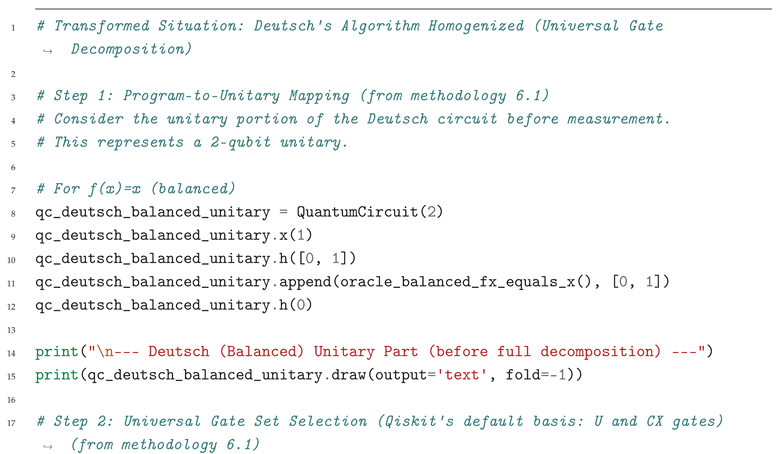

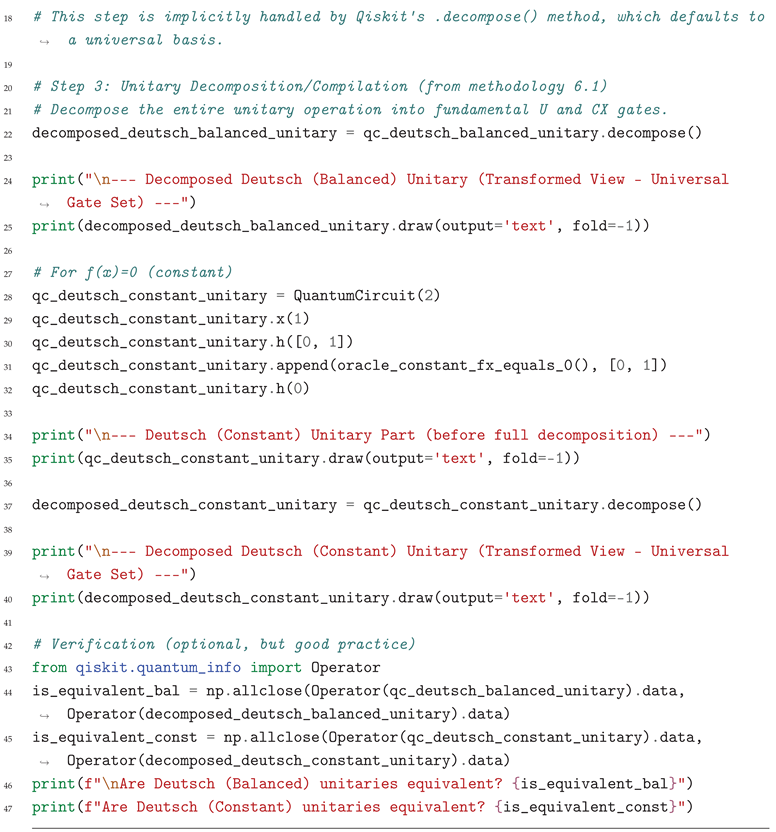

Transformed Situation (SU() Homogenization - Universal Gate Decomposition)

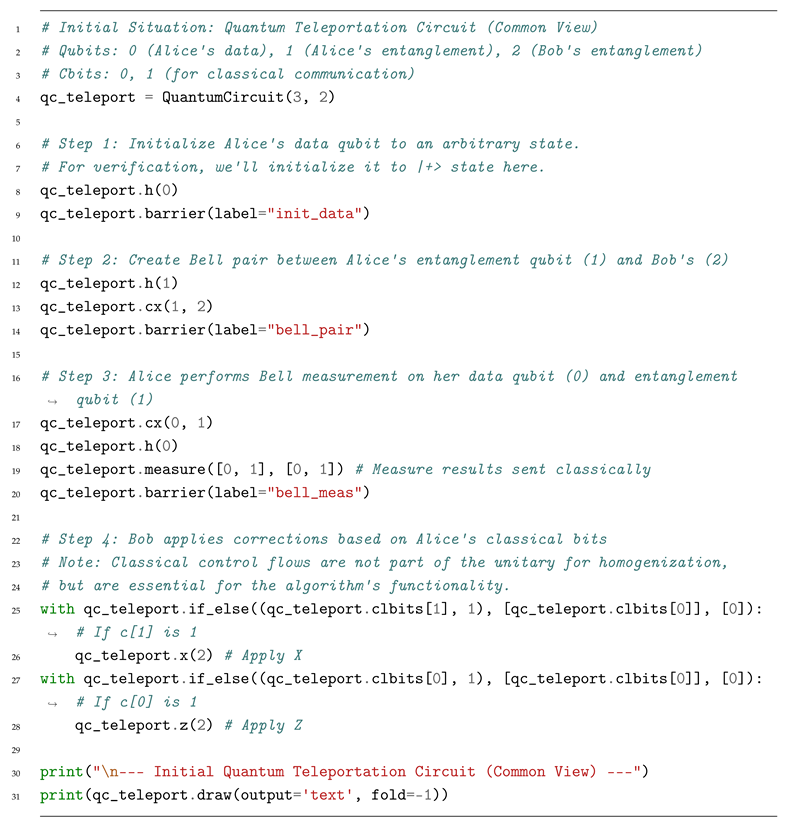

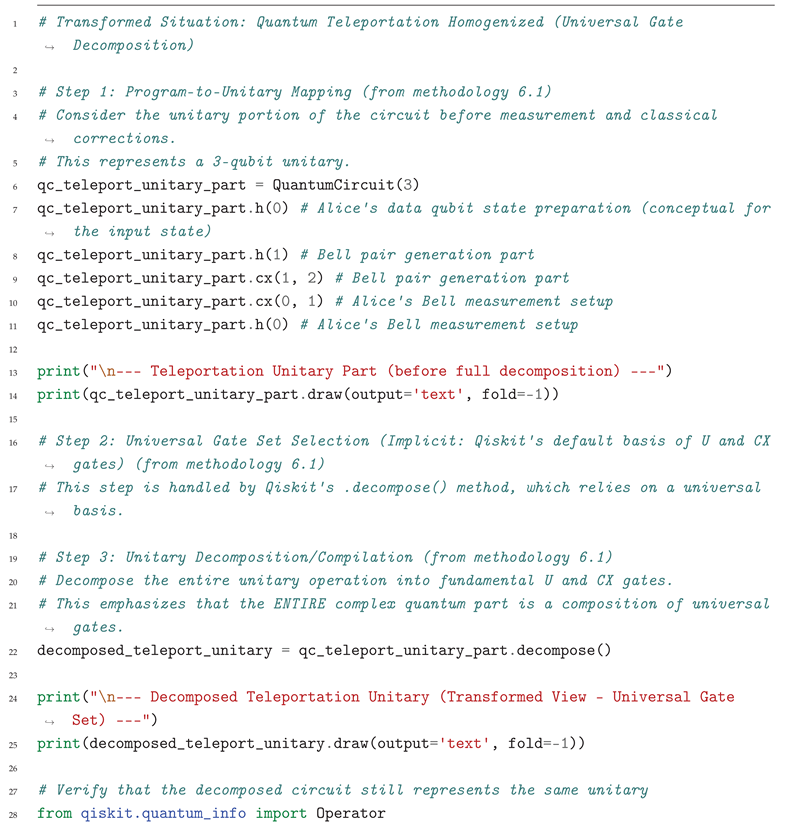

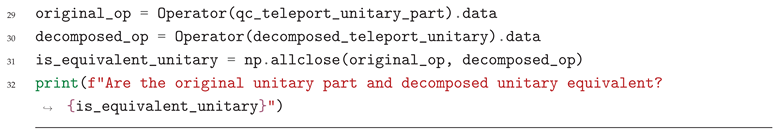

7.2. Example 2: Quantum Teleportation

Initial Situation (Common View - Qiskit Program)

Transformed Situation (SU() Homogenization - Universal Gate Decomposition)

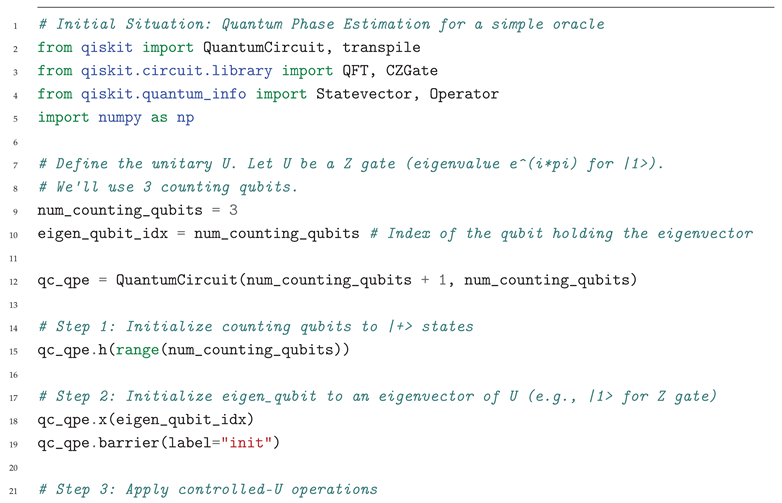

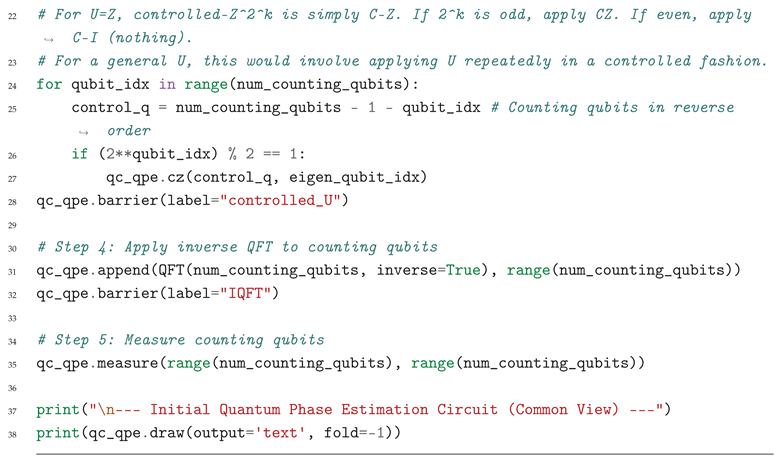

7.3. Example 3: Quantum Phase Estimation

Initial Situation (Common View - Qiskit Program)

Transformed Situation (SU() Homogenization - Universal Gate Decomposition)

8. Conclusions

References

- Preskill, J. Quantum computing in the NISQ era and beyond. Quantum 2018, 2, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Mitra, D.; Ray, S.; Koley, S.; Rakshit, A. A Comprehensive Review of Quantum Circuit Optimization: Current Trends and Future Directions. Entropy 2023, 25, 1450. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui, S.R.; Singh, A.; Gupta, A. A Comprehensive Survey on Quantum Circuit Compilation and Optimization. Journal of Computer Science and Technology 2022, 37, 1335–1358. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore, R. Lie Groups, Lie Algebras, and Some of Their Applications; Dover Publications, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, B.C. Lie Groups, Lie Algebras, and Representations: An Elementary Introduction; Springer, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, B. Formal Verification of Quantum Circuits: A Survey. arXiv preprint, 2022; arXiv:2204.03212. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Li, G.; Lin, C. Efficient Quantum Circuit Synthesis with Genetic Algorithms. arXiv preprint, 2023; arXiv:2302.04018. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Hu, S.; Deng, J.; Xia, J. Adaptive Quantum Circuit Compilation with Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems (ASPLOS ’23); 2023; pp. 1269–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Y.; Ma, Z.; Li, S.; Wang, K.; Zhang, C. High-Fidelity Quantum Gate Control for Superconducting Qubits. Physical Review Applied 2023, 19, 014002. [Google Scholar]

- Kou, Z.; Song, S.; Yu, X.; Lv, H. Recent Progress in Optimal Quantum Control. Physics Reports 2023, 1032, 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor, T.J.; Magesan, E.; Gambetta, J.B. Measuring the quality of quantum operations. PRX Quantum 2022, 3, 010344. [Google Scholar]

- Magesan, E.; Gambetta, J.M.; Merkel, S.T. Quantum computational benchmarking. Physics Reports 2022, 950, 1–84. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.; Cao, C.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Y. A Survey on Quantum Circuit Static Analysis. arXiv preprint, 2023; arXiv:2308.06408. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Lu, S.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, J. Quantum Neural Network Architectures for Variational Quantum Algorithms: A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Quantum Engineering 2023, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Sun, Z.; Gao, K. Reinforcement Learning for Quantum Circuit Design: Using Matrix Representations. arXiv preprint, 2022; arXiv:2201.07765. [Google Scholar]

- Moussa, H.; Jaber, M.; Kouro, S. Exact Quantum Circuit Synthesis Using Satisfiability Modulo Theories. Journal of Quantum Computing 2023, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Y.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, P. Compiling Two-Qubit Gates to Any-to-Any Connectivity with Optimal Depth. IEEE Transactions on Quantum Engineering 2022, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, L.; Ding, Y.; Sun, Z.; Yang, B. Q-Transpiler: An Efficient Quantum Circuit Transpiler with Machine Learning-based Routing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 27th Asia and South Pacific Design Automation Conference (ASPDAC ’22); 2022; pp. 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Gambetta, J.M.; Magesan, E.; McKay, D.C. Benchmarking Quantum Processor Performance at Scale. arXiv preprint, 2023; arXiv:2311.05933. [Google Scholar]

- Gidney, C.; Fowler, A.G. Benchmarking a 106-qubit fault-tolerant quantum computer. Quantum 2022, 6, 735. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Song, Z.; Wang, L. Progress in Qudit Quantum Computing. Quantum Science and Technology 2023, 8, 035028. [Google Scholar]

- Weedbrook, C.; Pirandola, S.; García-Patrón, R.; Cerf, N.J.; Ralph, T.C.; Shapiro, J.H.; Lloyd, S. Gaussian quantum information. Reviews of Modern Physics 2012, 84, 621–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgi, H. Lie Algebras in Particle Physics: From Isospin to Unified Theories; Westview Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, M.A.; Chuang, I.L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Qiskit Development Team. Qiskit: An open-source framework for quantum computing. IBM, 2023a. Retrieved from https://qiskit.org/documentation/.

- Qiskit Development Team. Qiskit Documentation: OneQubitEulerDecomposer. IBM, 2023b.

- Kitaev, A.Y. Quantum computations: algorithms and error correction. Russian Mathematical Surveys 1997, 52, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovay, R. Lie Groups and Universal Sets of Quantum Gates. Technical report, Unpublished technical report, 1995.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).