2. Case Report

In June 2023, a 73-year-old man came to our attention during an outpatient visit.

-

a.

Clinical History

In November 2002, after to an episode of buccal deviation and intense headaches, he performed brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast showing an extracerebral neoformation in the right frontal convexity, compatible with meningioma. In March 2003 he underwent surgery; histological examination reported transitional meningioma with aspects of microcystic meningioma, whose presence of focal areas of necrosis and cytological atypia could be an expression of aggressive biological behaviour. There was no residual disease on post-surgery MRI. Thereafter, he was subjected to clinical and radiological follow-up. On January 2004, brain MRI showed residue of the previously removed lesion. Therefore, he underwent surgery and, subsequently, adjuvant radiotherapy (RT). Brain MRI after neurosurgery showed a small meningiomatous residue in the right parasagittal frontal region. Then, he was subjected to instrumental follow-up, first every six months, then annually, confirming the stability of the meningeal residue. In January 2023, due to the onset of persistent and irritable cough episodes unresponsive to medical therapy, a Computed Tomography (CT) scan was performed, which revealed a 20x5 mm nodule in the right upper lobe. Positron emission tomography with 18 F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18-FDG-PET) showed hyperaccumulation of the tracer in the right lung (SUV max 6.2)and in the right frontal lobe (SUV max 15.0). In May 2023, he performed a TRU-CUT needle biopsy of the right lung lesion. The histological examination described frustules of lung parenchyma that were the site of proliferation of epitheliomorphic elements of bland morphology, with a large cytoplasm with clear margins organized in solid nests and sometimes in vorticoid structures. Immunohistochemical analysis showed positivity to CK8/18, CD56 and focally to S100, as observed in case of meningothelial neoplasia. Chromogranin, synaptophysin, TTF1, P40, PGR, EMA, OLIG2, STAT6, GFAP, CEA, CD15 and ESA were all negative, expression of BAP1 retained. The Ki67/MIB1 growth fraction was 3%. The morphological and immunohistochemical picture supported main possibility as the secondary localization of the known encephalic meningiomatous lesion.

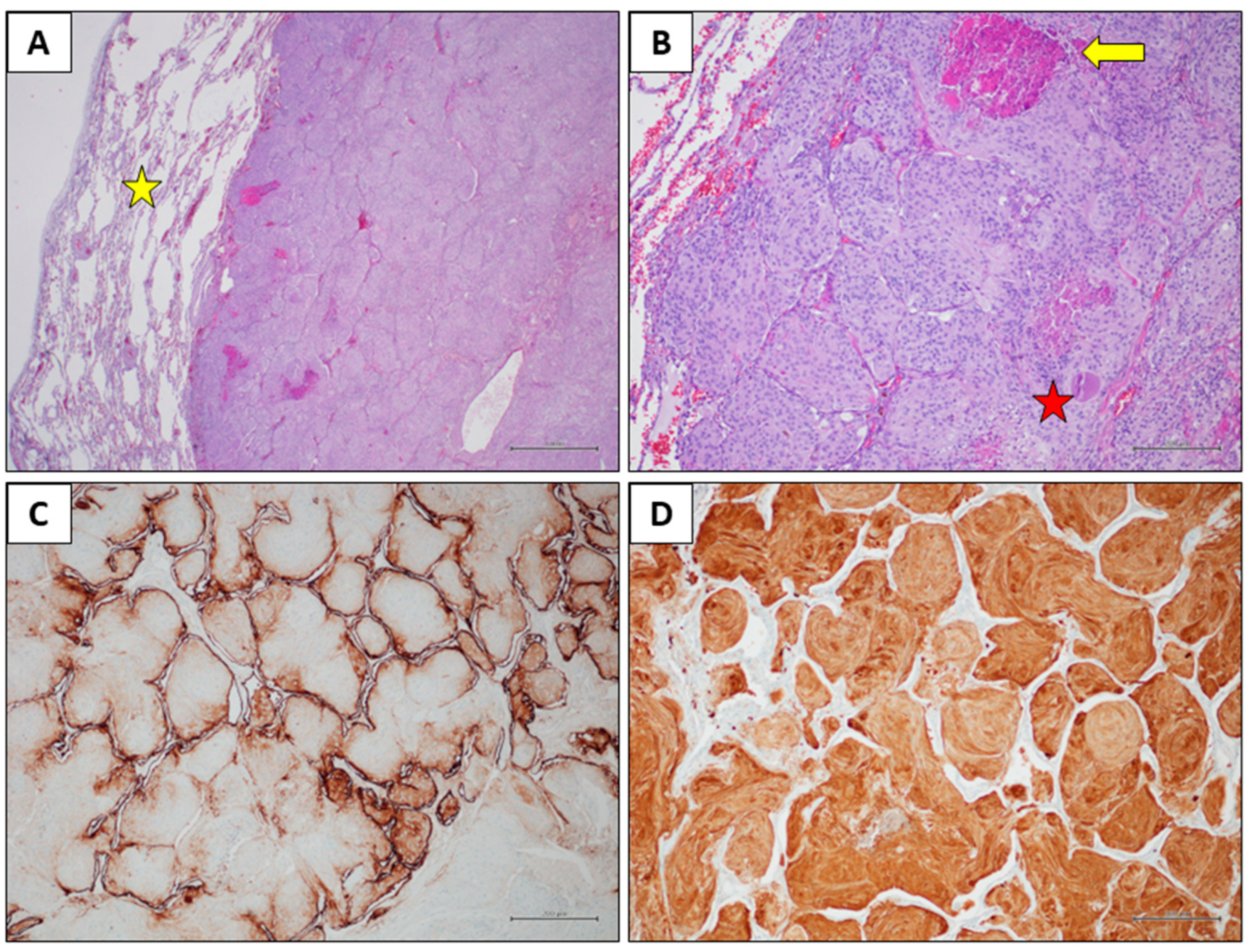

Figure 1.

Histological findings. A) Histological examination reveals a solid neoplastic mass within the lung parenchyma (yellow star), exhibiting a pushing, expansive growth pattern (Hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification 20x). B) The tumour shows a lobular architecture and is composed of elongated cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, oval nuclei, and inconspicuous nucleoli. An eosinophilic globule (red star) and areas of necrosis (yellow star) are observed (Hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification 100x). C) EMA immunohistochemistry showed faint positivity in few neoplastic cells, with strong expression in pneumocytes (immunohistochemical stain, original magnification 100x). D) S100 immunohistochemistry revealed diffuse positivity in the neoplastic cells (immunohistochemical stain, original magnification 100x).

Figure 1.

Histological findings. A) Histological examination reveals a solid neoplastic mass within the lung parenchyma (yellow star), exhibiting a pushing, expansive growth pattern (Hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification 20x). B) The tumour shows a lobular architecture and is composed of elongated cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, oval nuclei, and inconspicuous nucleoli. An eosinophilic globule (red star) and areas of necrosis (yellow star) are observed (Hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification 100x). C) EMA immunohistochemistry showed faint positivity in few neoplastic cells, with strong expression in pneumocytes (immunohistochemical stain, original magnification 100x). D) S100 immunohistochemistry revealed diffuse positivity in the neoplastic cells (immunohistochemical stain, original magnification 100x).

-

b.

Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis and Treatment

At the outpatient visit, the patient presented partial orientation in time and space, sporadic episodes of non-productive cough and absence of neurological symptoms. Therefore, we prescribed histological review of the lung aspiration slides and instrumental re-evaluation. The CT scan confirmed the known right lung lesion, now slightly increased, while the PET scan showed an increase hyperaccumulation in the right lower lobe nodule (SUV max 9.2 vs 6.2) and in the right frontal lobe (SUV max 19.3 vs 15.0). The histological review described a predominantly monomorphic, polygonal epithelioid-type cell population, organized in lobules or in the typical "vortex" appearance. The nuclei, rounded and nucleolated, showed focal and slight atypia; the cytoplasm, abundant and eosinophilic, sometimes appeared vacuolized. Mitoses were rare (2x10 HPF 40X). The morphological and immunohistochemical picture was compatible with a secondary lesion from meningioma with meningothelial-type aspects. The case was discussed collegially in the multidisciplinary lung cancer oncology group in August 2023, and atypical lung resection in Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery (VATS) was performed in October 2023. Histopathological examination revealed medium-sized, monomorphic cell clusters with a syncytial, fasciculated, whorl-like growth pattern, presence of psammomatous bodies, and rare mitoses, all compatible with a secondary lesion from meningioma of the meningothelial type. The patient then started follow-up with total body CT and 18-FDG-PET, brain MRI. Last clinical-instrumental revaluation in October 2024 resulted in absence of disease recurrence.

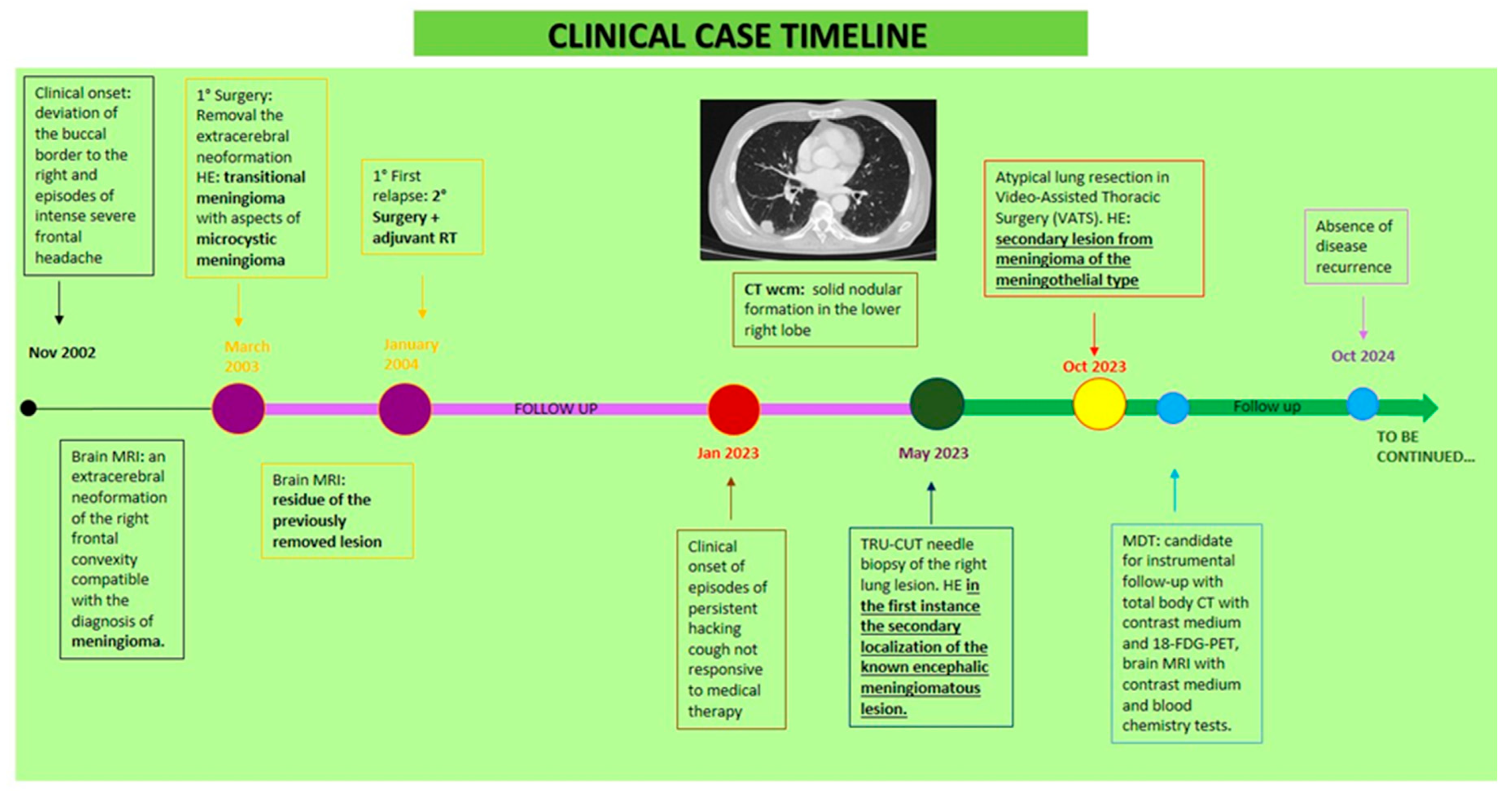

Figure 2.

Clinical case timeline.

Figure 2.

Clinical case timeline.

Abbreviations: RT: radiotherapy; CT: computed Tomography; WCM: with contrast medium; HE: histological examination; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; MDT: multidisciplinary team.

-

c.

Materials and Methods and Results

We performed also Oncomine Comprehensive Assay Plus of the lung metastasis paraffin-embedded tissue in order to find putative genetic alterations of the tumour, explaining, at least in part, the uncommon presentation of the meningioma. The genomic profiling of the meningioma metastasis revealed multiple nucleotide variants (MNV), dominantly truncated variants, caused by Deletion-Insertions (DELINs) at the microsatellite site c.41-48 of Beta-2-Microglobulin (B2M) gene. Reported alterations were all nonsense mutations, leading to a truncated protein, and showed different frequency: c.41_42delCTinsAA variant allele frequency (VAF) 80.3%, c.43_45delCTTinsTAG (VAF 19.46%), c.47_48delCTinsAA (VAF 21.48%). Interestingly, we also found a mutation of Programmed Cell Death 1 Ligand 2 gene (PDCD1LG2) (c.789_791delCAC, VAF 92.97%) of not clear functional significance. Moreover, we found a mutation of Ataxia-Telangiectasia Mutated (ATM) gene affecting its splicing and determining loss of function (c.4777-1G>C, VAF 85.74%). A c.23T>A (VAF 24.53%) mutation of Cadherin 10 (CDH10) was recorded. The AT-Rich Interaction Domain 1B (ARID1B) c.1592_1593insACC mutation was, on the other hand, likely benign and had a low VAF (8.11 %) whereas c.2890delG (VAF 23.08%) determined a frame shift mutation likely affecting the function of the coded protein.

All tumor samples isolated from FFPE blocks were reviewed by a pathologist in order to estimate the tumoral area for dissection and nucleic acid extraction (more than 80%). DNA and RNA were isolated using the MagMAX™ FFPE DNA/RNA Ultra Kit (Applied BiosystemsTM, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in a semi automatic mode on a KingFisher™ Duo Prime magnetic particle processor (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). DNA and RNA were quantitated using a Qubit Fluorometer with Qubit dsDNA HS Assay kit (InvitrogenTM, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and Qubit RNA HS Assay kit (InvitrogenTM, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA.). 20 ng of DNA and RNA were used as input and DNA sample was subjected to deamination reaction using Uracil-DNA Glycosylase-heat labile (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). OCA+ primer pools were used for library preparation on Ion Chef (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) liquid handler and sequencing was performed using Ion 550™ Chips in the Ion S5™ Sequencer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Data analysis was performed on Ion Reporter™ Software 5.2.20 version. The results are summarized in

Table 1.

3. Discussion

Meningiomas are among the most frequent tumors of the intracranial central nervous system with an incidence of approximately 13-26% [

15], far exceeding glioma [

16].

Grade 1 tumors represent 80% of all meningiomas [

7] and are most often slow-growing tumors that have a benign course and a lower risk of post-operative recurrence compared to the other two grades [

3]. Transitional meningiomas are among the most common subtypes of grade 1 meningioma [

17]; also known as mixed ones [

18] due to the characteristic of being transitional between the meningothelial and fibrous ones [

7].

In the case of grade 1 meningiomas, only complete excision is performed, [

15] while in the case of subtotal resection or aggressive histology and for grade 2 and 3 tumors, adjuvant radiotherapy usually follows surgical treatment [

19].

Extracranial metastases are very rare, occurring only in approximately 0.1% of cases [

6]. This greatly worsens the prognosis, reducing survival from 88.3% to 66.5% at 5 years [

11].

Due to the rarity of this event, full knowledge of the risk factors of extracranial metastases is not yet understood [

11]. Often, before the appearance of extracranial metastases, intracranial recurrences occur several times, thus being the only recognized risk factor [

10,

16]. Local recurrence rates, after total surgery, range from 9 to 32% [

19] and, as observed in our case, the reported recurrence rate of transitional meningioma is surprisingly high [

7]. The presence of metastases does not represent a criterion for the WHO classification [

14], as they can occur in both grade 1 and higher grade meningioma [

10]. Different studies with heterogenous results have been performed to define the association between extracranial metastatization and histological grade. Kessler et al. reported a higher association with grade II, while Surov et al. with grade III meningiomas [

20]. Therefore, the propensity to metastasize cannot be predicted upon grading [

10,

14].

The average interval between the primary meningioma and first metastases is approximately 6 years [

6]. More precisely, Enomoto et al. performed a metanalysis of 35 articles, highlighting that the average time to the appearance of metastases was 11.0, 5.4 and 2.0 years for grades I, II and III [

21].

Lung represents the most common site (60%), followed by abdomen and liver (34%), cervical lymph nodes (18%), long bones, pelvis and skull (11%), pleura (9%), vertebrae (7%), central nervous system (7%) and mediastinum (5%) [

22].

It seems that the site of origin of primary meningiomas influences the formation of metastases, as parasagittal and falx localizations are most commonly associated to metastatization [

6].

Repeated surgical interventions would represent another risk factor [

23], due to damage to the blood brain barrier, favoring the release of tumor cells into the bloodstream [

7,

24]. In fact, approximately 90% of extracranial metastases described in various studies occur following surgical resection or shunt surgery; in this way, tumour cells flow into the extra-meningeal blood and lymphatic vessels, giving systemic dissemination [

7,

16,

24].

The metastatic sites depend upon the route of dissemination [

16]. It is described that 75% of patients with extracranial metastases of meningioma present invasion of the venous sinus [

21], giving mainly lung metastases [

25]. Another route is the cerebrospinal fluid being meningiomas naturally exposed to this fluid for anatomic reasons, reachingthe less common metastatization sites [

16].

The pathogenesis of meningioma metastases is currently unknown, but it has been observed that a probable predictor of multiple pulmonary metastases is the loss of heterozygosity at 9p, 1p and 22q [

6] [

16,

24]. It has also been reported that CD90 is highly expressed in lung metastasis from meningioma [

21].

Meningiomas harboring the NF2 mutation, recorded in numerous cases of metastatic meningioma, appear to have greater genetic instability [

7,

11].

TRAF7, SMO, AKT1, and KLF4 mutations, termed “non-NF2” tend to be found in lower grade meningiomas, with fewer chromosomal abnormalities, and with generally better clinical outcomes [

26].

In our case, no mutations in these genes were found, but alterations in the beta-2-microglobulin (B2M) gene sequence were recorded suggesting a loss-of-function (likely germinal). B2M gene, located on chromosome 15 (15q21.1), encodes a non glycosylated protein, that shares structural similarities with the immunoglobulin (Ig) constant region and the α3 domain of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecule [

27]. B2M is found both in free form and attached to the cell membrane, and the free from is a significant prognostic factor and predictor of survival in various cancers. It is a crucial component of MHC class I molecules and its alterations can lead to a null or lower expression of MHC class I complex which can compromise the mechanism of antigen presentation to immune cell system [

27]. Moreover, B2M shows significant alterations in cancer tissues, particularly in tumors characterized by microsatellite instability (MSI) and mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR) [

28]. Interestingly, the human B2M has dinucleotide repeats regions which are hotspots for frameshift indels that could alter or silence B2M and so the antigen-presentation process [

28]. Additional studies are warranted to define the real function of this protein. The programmed Cell Death 1 Ligand 2 (PDCD1LG2) gene encodes the surface receptor [

29], belonging to the B7 protein family [

30], expressed on antigen-presenting cells [

31], performing a main function in immune tolerance and autoimmunity [

32]. Wang reported that PD-L2 in gliomas was closely related to inflammation and immune response and better survival [

33].

A mutation in the Ataxia-Telangiectasia Mutated (ATM) gene that affects its splicing and causes loss of function [

34] has been also found (c.4777-1G>C, VAF 85.74%). This variant has been classified as probable pathogenic [

35]. This gene encodes a protein kinase that is recruited upon DNA damage, and phosphorylates many proteins involved in DNA repair, cell cycle checkpoints, and apoptosis [

36]. Missense mutation of Cadherin 10 (CDH10) gene was also recorded withno previous association with cancer. Somatic mutations in CDH10,expressed predominantly in the brain and involved in synaptic adhesions and axon growth and guidance [

37], are associated with colorectal, gastric, and lung cancer and are considered a driver mutation in pancreatic cancer [

38]. The AT-Rich Interaction Domain 1B (ARID1B) c.1592_1593insACC mutation was likely benign and had a low VAF (8.11 %) whereas c.2890delG (VAF 23.08%) determined a frame shift mutation likely affecting the function of the coded protein. ARID1B is a DNA-binding subunit of the Brahma-associated factor chromatin remodelling complexes, engaged in the regulation of gene activity. Its mutation has been found in neurodevelopmental disorders [

39]. This mutation, too, was never previously associated to cancer development. Then, excluding B2M and ATM, regarding the other mutations found in the other genes no definitive conclusions on their role in the development of meningioma can be driven based upon the lack of previous evidence.

An important support for neuropathologists in determining aggressiveness is the nuclear antigen expressed during active phases of the cell cycle called Ki67 [

14]. Previous research has reported a high proliferative index of Ki-67 (MIB-1) among the factors which also increase the risk of metastasis [

7]. Usually, the proliferative index tends to increase in correlation with the grade and, more precisely, benign meningiomas have an average proliferative index of 4% while anaplastic ones of approximately 14.7% [

7]. In our case the Ki67/MIB1 growth fraction of the metastatic lesion was equal to 3%. This finding makes our case even more peculiar.

Nowadays, there is no standard protocol for the management of meningioma metastases [

26]. Surgical or stereotactic radiosurgical resection improves survival, although the literature is very limited [

26]. Chemotherapy with hydroxyurea, temozolomide and trabectedin has limited efficacy and is not recommended, as it has achieved poor results in terms of both disease control and survival [

40]. There are several ongoing clinical trials on systemic therapies with immunotherapy, 177Lu-DOTATATE, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, abemaciclib, capivasertib and vismodegib [

41].