Submitted:

11 June 2025

Posted:

12 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

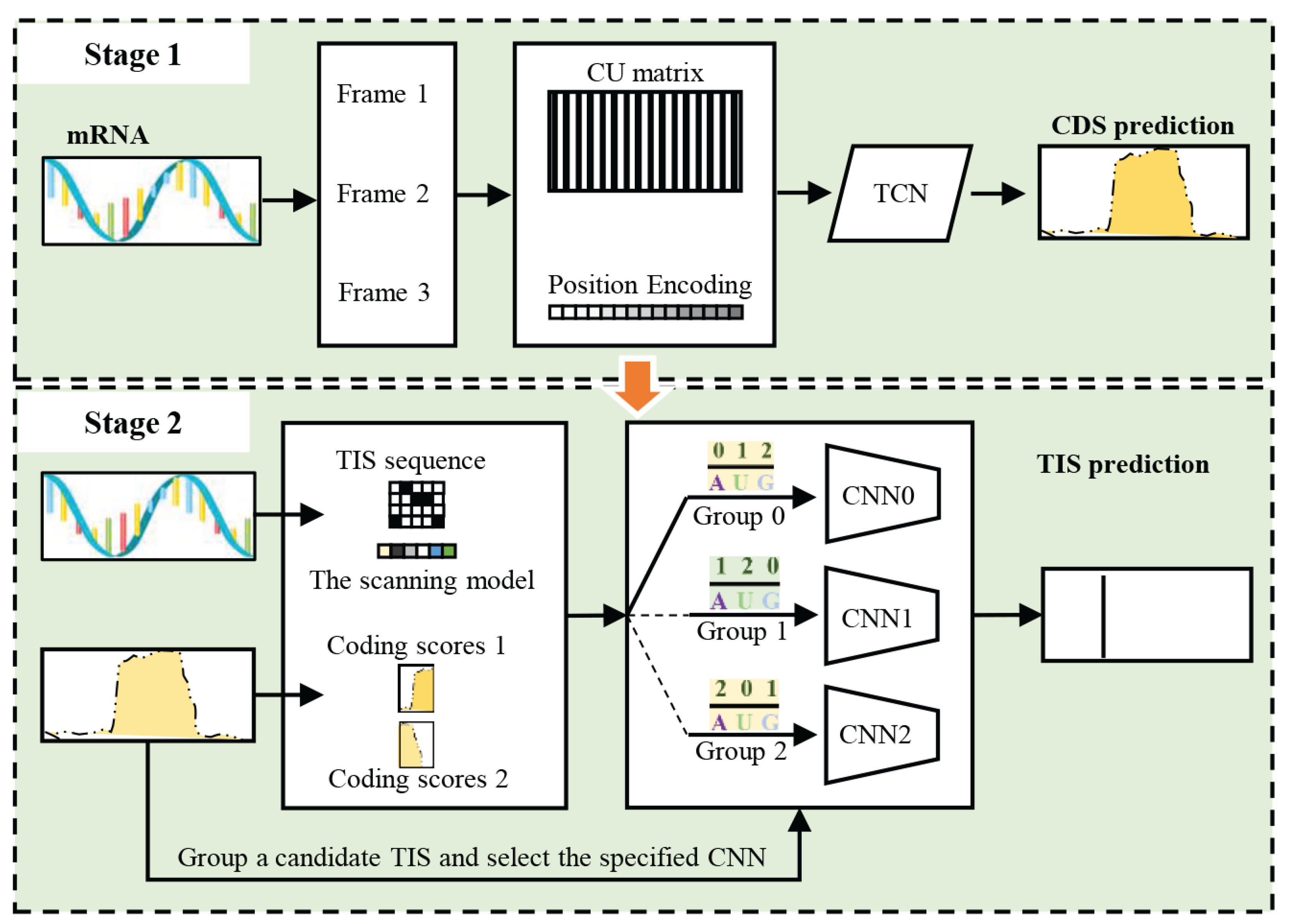

- The proposed method, NeuroTIS+, is an improved version of NeuroTIS, which preserve the basic framework of NeuroTIS, and hence, it inherits the merits of explicitly modeling statistic dependencies among variables and automatical feature learning. Meanwhile, it assumes stronger dependency relationship among codon labels and integrates novel frame information for TIS inference.

- We consider the structural information that CDS is continuous and models codon labels consistency by using a TCN which can easily and naturally implement the process of multiple codon labels information aggregation by convolutional layers. Moreover, a position embedding and a fast codon usage generating strategy for a sequence are also proposed to improve the prediction of coding sequence in mRNA sequence.

- We consider the heterogeneity of negative TIS and develop an adaptive grouping strategy for homogenous feature building, which effectively improve the prediction accuracy of TIS. Moreover, the adaptive grouping strategy stablizes the learning process of CNN.

2. Related Works

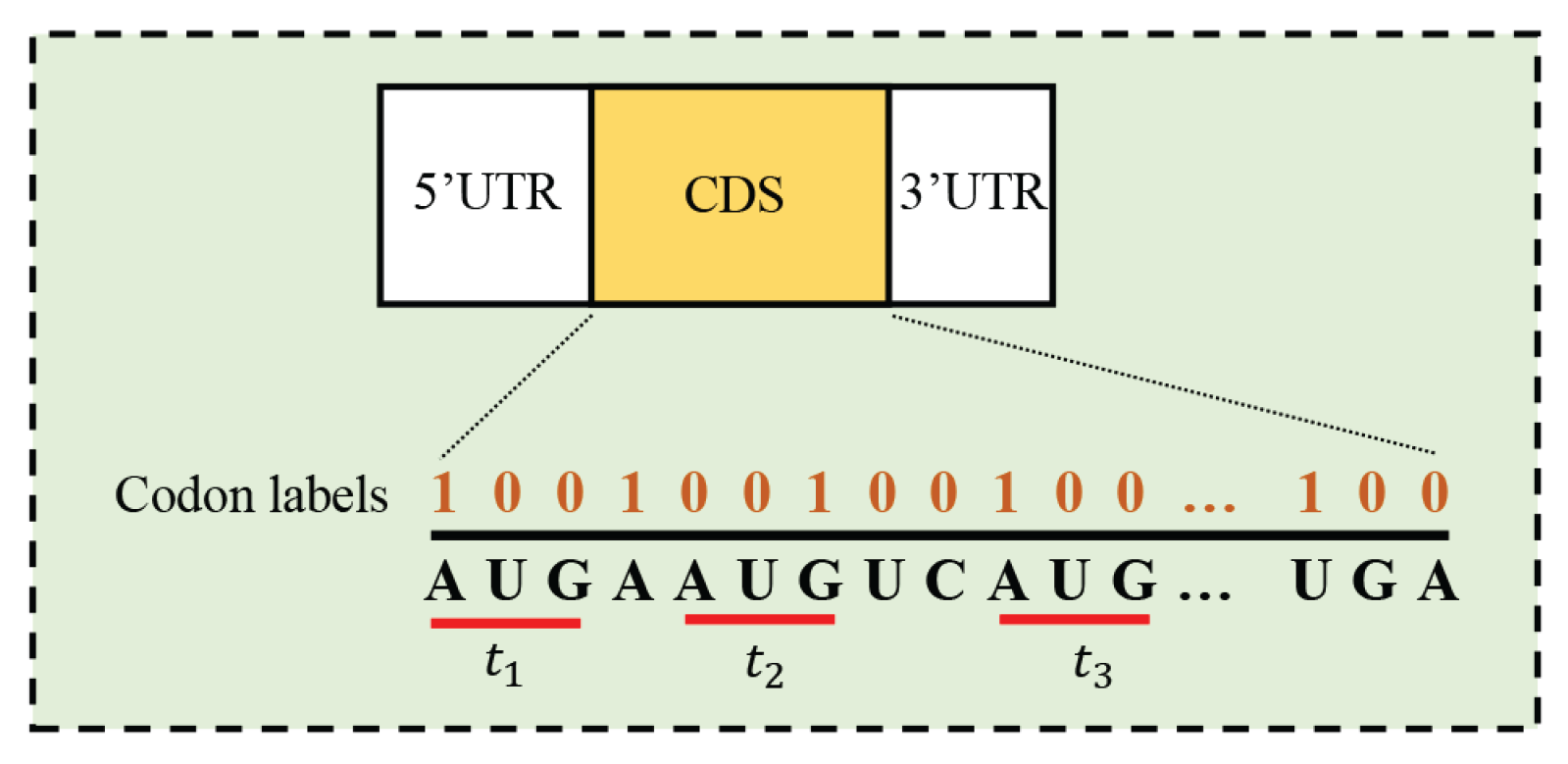

2.1. Codon Labels Consistency

2.2. Non-Homogeneous Negative TIS

3. The Proposed Method

3.1. Preliminaries

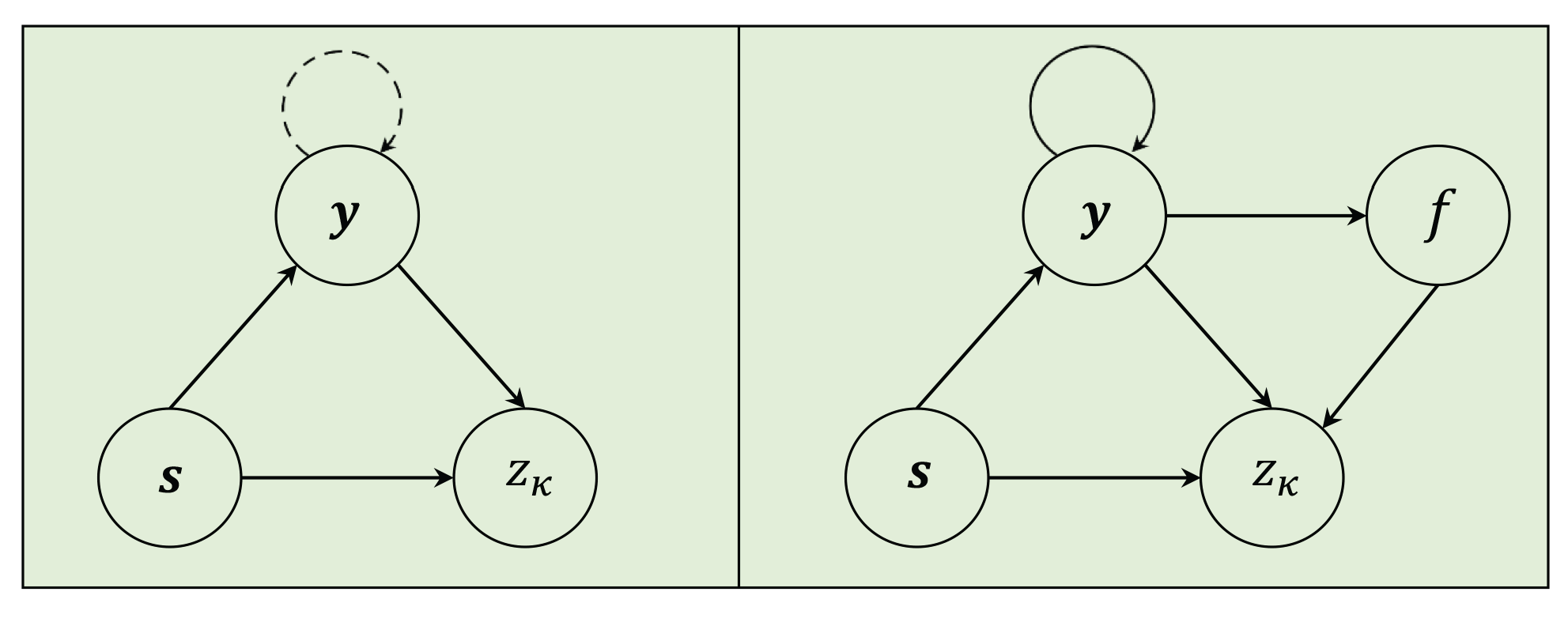

3.2. NeuroTIS

3.3. NeuroTIS+

3.3.1. Dependency Network Representation

3.3.2. Temporal Convolutional Network for CDS Prediction

| Algorithm 1: Fast CU matrix generation strategy |

|

3.3.3. Frame-Specific CNN with Adaptive Grouping Strategy for TIS Prediction

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

4.2. Performance Measurements

4.3. Significance of Adaptive Grouping Strategy

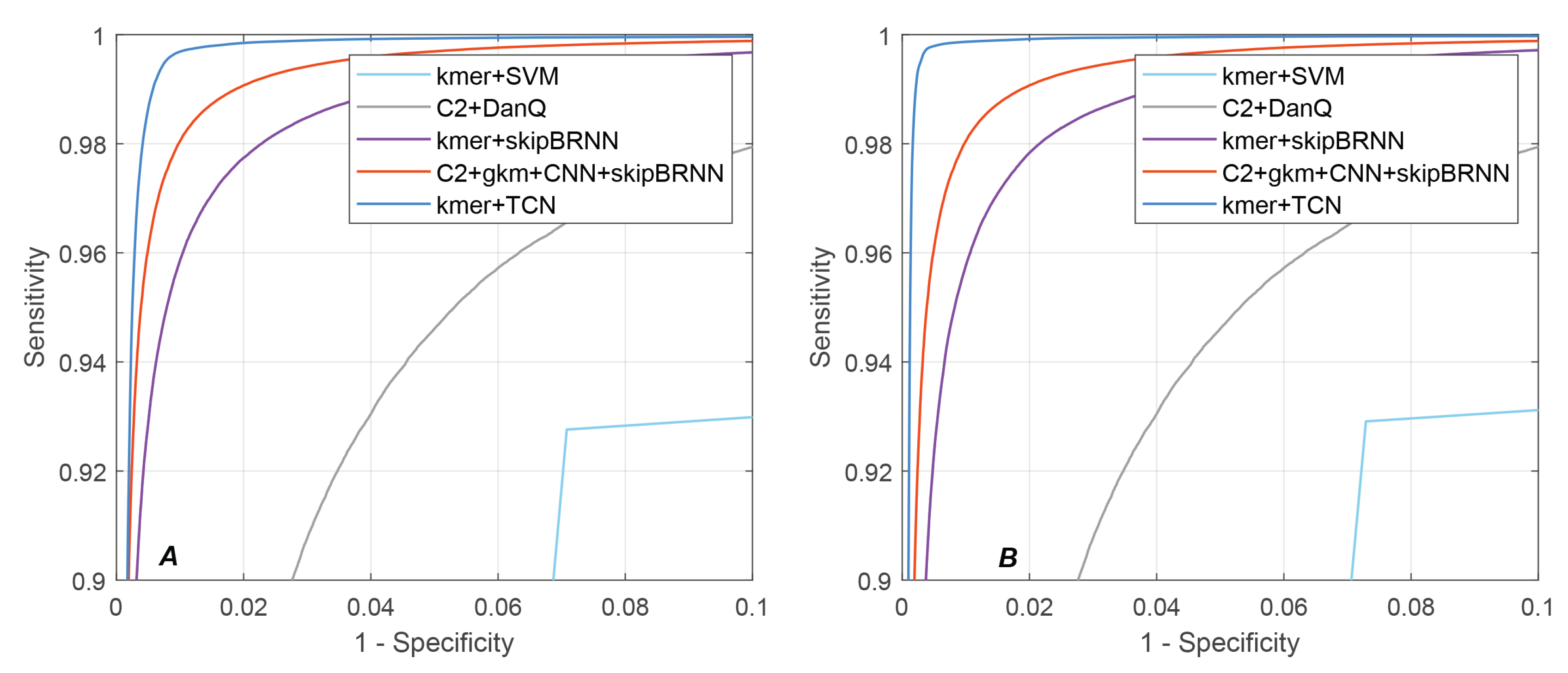

4.4. Performance Comparison for CDS Prediction

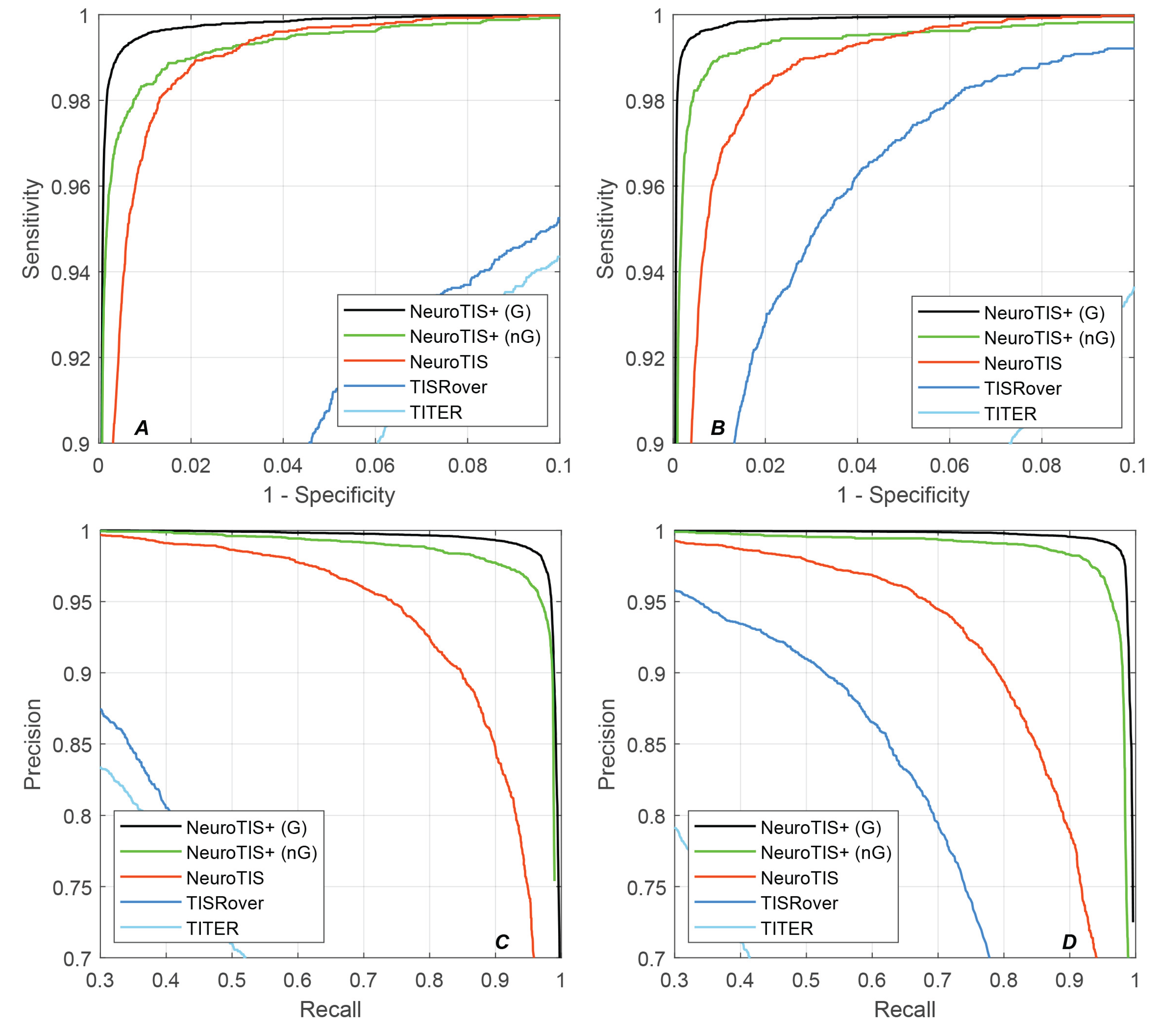

4.5. Performance Comparison for TIS Prediction

4.6. Time Cost of NeuroTIS+

5. Discussions

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sonenberg, N.; Hinnebusch, A.G. Regulation of Translation Initiation in Eukaryotes: Mechanisms and Biological Targets. Cell 2009, 136, 0–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, C.; Peixeiro, I.; Romão, L. Gene expression regulation by upstream open reading frames and human disease. PLoS genetics 2013, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Hu, H.; Jiang, T.; Zhang, L.; Zeng, J. TITER: predicting translation initiation sites by deep learning. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, i234–i242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venket, R.; Louis, K.; Fantin, M.; Linda, R. A simple guide to de novo transcriptome assembly and annotation. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2022, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, M. Translation of insulin-related polypeptides from messenger RNAs with tandemly reiterated copies of the ribosome binding site. Cell 1983, 34, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malys, N. Shine-Dalgarno sequence of bacteriophage T4: GAGG prevails in early genes. Molecular biology reports 2012, 39, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, A.; Crammer, K.; Hatzigeorgiou, A.; Pereira, F. Global discriminative learning for higher-accuracy computational gene prediction. PLoS computational biology 2007, 3, e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinnebusch, A.G.; Ivanov, I.P.; Sonenberg, N. Translational control by 5’-untranslated regions of eukaryotic mRNAs. Science 2016, 352, 1413–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersma, S.; Khuperkar, D.; Verhagen, B.M.; Sonneveld, S.; Grimm, J.B.; Lavis, L.D.; Tanenbaum, M.E. Multi-color single-molecule imaging uncovers extensive heterogeneity in mRNA decoding. Cell 2019, 178, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuperkar, D.; Hoek, T.A.; Sonneveld, S.; Verhagen, B.M.; Boersma, S.; Tanenbaum, M.E. Quantification of mRNA translation in live cells using single-molecule imaging. Nature Protocols 2020, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, A.G.; Nielsen, H. Neural network prediction of translation initiation sites in eukaryotes: perspectives for EST and genome analysis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Systems for Molecular Biology; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rajapakse, J.C.; Ho, L.S. Markov encoding for detecting signals in genomic sequences. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Computational Biology and Bioinformatics 2005, 2, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuallaert, J.; Kim, M.; Soete, A.; Saeys, Y.; Neve, W.D. TISRover: ConvNets learn biologically relevant features for effective translation initiation site prediction. International Journal of Data Mining and Bioinformatics 2018, 20, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zien, A.; Rätsch, G.; Mika, S.; Schölkopf, B.; Lengauer, T.; Müller, K.R. Engineering support vector machine kernels that recognize translation initiation sites. Bioinformatics 2000, 16, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jiang, T. A class of edit kernels for SVMs to predict translation initiation sites in eukaryotic mRNAs. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Resaerch in Computational Molecular Biology; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Feng, P.M.; Deng, E.Z.; Lin, H.; Chou, K.C. iTIS-PseTNC: A sequence-based predictor for identifying translation initiation site in human genes using pseudo trinucleotide composition. Analytical Biochemistry 2014, 462, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamov, A.A. Assessing protein coding region integrity in cDNA sequencing projects. Bioinformatics 1998, 14, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Leong, T.Y.; Zhang, L. Translation Initiation Sites Prediction with Mixture Gaussian Models. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2005, 17, 1152–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, T.; Ota, T.; Isogai, T. Prediction of Fullness of cDNA Fragment sequences by combining Statistical Information and Similarity with Protein Sequences.

- Hatzigeorgiou, A.; Mache, N.; Reczko, M. Functional site prediction on the DNA sequence by artificial neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings IEEE International Joint Symposia on Intelligence and Systems. IEEE; 1996; pp. 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzigeorgiou, A.G. Translation initiation start prediction in human cDNAs with high accuracy. Bioinformatics 2002, 18, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzanis, G.; Berberidis, C.; Vlahavas, I. MANTIS: a data mining methodology for effective translation initiation site prediction. In Proceedings of the International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tzanis, G.; Berberidis, C.; Vlahavas, I. StackTIS: A stacked generalization approach for effective prediction of translation initiation sites. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2012, 42, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovyev, V.; Umarov, R. Prediction of prokaryotic and eukaryotic promoters using convolutional deep learning neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1610.00121, arXiv:1610.00121 2016.

- Min, X.; Zeng, W.; Chen, S.; Chen, N.; Chen, T.; Jiang, R. Predicting enhancers with deep convolutional neural networks. BMC bioinformatics 2017, 18, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Liu, X.; Macleod, J.N.; Liu, J. DeepSplice: Deep classification of novel splice junctions revealed by RNA-seq. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Du, X.; Yao, Y.; Diao, Y.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S. DeepSS: Exploring Splice Site Motif Through Convolutional Neural Network Directly From DNA Sequence. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 32958–32978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuallaert, J.; Godin, F.; Kim, M.; Soete, A.; Saeys, Y.; De Neve, W. SpliceRover: interpretable convolutional neural networks for improved splice site prediction. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 4180–4188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, X.; He, Z.; Liu, G.; Wu, J. Neurotis: Enhancing the prediction of translation initiation sites in mrna sequences via a hybrid dependency network and deep learning framework. Knowledge-Based Systems 2021, 212, 106459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, J.; Pascanu, R.; Rabinowitz, N.; Veness, J.; Desjardins, G.; Rusu, A.A.; Milan, K.; Quan, J.; Ramalho, T.; Grabska-Barwinska, A.; et al. Overcoming catastrophic forgetting in neural networks. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences 2017, 114, 3521–3526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lea, C.; Flynn, M.D.; Vidal, R.; Reiter, A.; Hager, G.D. Temporal convolutional networks for action segmentation and detection. In Proceedings of the proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2017; pp. 156–165. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Gu, S. Multi-Label Classification Using Conditional Dependency Networks. In Proceedings of the IJCAI 2011, Proceedings of the 22nd International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain, 16-22 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Farha, Y.A.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, M.M.; Gall, J. Ms-tcn++: Multi-stage temporal convolutional network for action segmentation. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2020, 45, 6647–6658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collobert, R.; Weston, J.; Bottou, L.; Karlen, M.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Kuksa, P. Natural language processing (almost) from scratch. Journal of machine learning research 2011, 12, 2493–2537. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Fan, Y.; Tse, M.; Lin, K.Y. A review of applications in federated learning. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2020, 149, 106854. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.; Ye, M.; Du, B. Learn from others and be yourself in heterogeneous federated learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022, pp. 10143–10153.

- Hu, G.Q.; Zheng, X.; Zhu, H.Q.; She, Z.S. Prediction of translation initiation site for microbial genomes with TriTISA. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rodríguez, J.; Arroyo-Peña, A.G.; García-Pedrajas, N. Improving translation initiation site and stop codon recognition by using more than two classes. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2702–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schum, D.A. The Evidential Foundations of Probabilistic Reasoning by David A. Schum; 1994.

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep learning; MIT press, 2016.

- Li, W.; Godzik, A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 1658–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T.M.; Carbonell, J.G.; Michalski, R.S. Machine Learning; 1997.

- Davis, J.; Goadrich, M. The relationship between Precision-Recall and ROC curves. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 23rd international conference on Machine learning, 2006, pp. 233–240.

- Srivastava, N.; Hinton, G.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2014, 15, 1929–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Treadgold, N.K.; Gedeon, T.D. Exploring constructive cascade networks. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 1999, 10, 1335–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Human | SN(%) | SP(%) | PRE(%) | ACC(%) | F1-score | auROC | auPRC | MCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TITER | 0.02 | 100 | - | 98.31 | - | 0.9788 | 0.6186 | - |

| TISRover | 92.52 | 93.77 | 20.26 | 93.75 | 0.3324 | 0.9760 | 0.3998 | 0.4167 |

| NeuroTIS | 98.19 | 98.54 | 56.29 | 98.53 | 0.7156 | 0.9985 | 0.9150 | 0.7377 |

| NeuroTIS+ (nG) | 98.38 | 98.94 | 84.29 | 98.91 | 0.9079 | 0.9989 | 0.9266 | 0.9052 |

| NeuroTIS+ (G) | 99.08 | 99.56 | 92.87 | 99.53 | 0.9588 | 0.9996 | 0.9385 | 0.9569 |

| Mouse | SN(%) | SP(%) | PRE(%) | ACC(%) | F1-score | auROC | auPRC | MCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TITER | 0.03 | 100 | - | 98.36 | - | 0.9766 | 0.5879 | - |

| TISRover | 95.29 | 96.74 | 32.52 | 96.72 | 0.4849 | 0.9936 | 0.7399 | 0.5463 |

| NeuroTIS | 98.12 | 98.31 | 48.90 | 98.30 | 0.6527 | 0.9982 | 0.9036 | 0.6865 |

| NeuroTIS+ (nG) | 98.63 | 99.26 | 86.96 | 99.23 | 0.9243 | 0.9991 | 0.9363 | 0.9223 |

| NeuroTIS+ (G) | 99.26 | 99.73 | 94.85 | 99.71 | 0.9701 | 0.9997 | 0.9460 | 0.9688 |

| Methods | Human | Mouse | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SN(%) | SP(%) | auROC | SN(%) | SP(%) | auROC | |

| kmer+SVM | 92.76 | 92.92 | - | 92.91 | 92.71 | - |

| C2+DanQ | 95.47 | 94.27 | 0.9889 | 95.32 | 94.37 | 0.9884 |

| kmer+skipBRNN | 98.25 | 97.39 | 0.9975 | 97.93 | 97.91 | 0.9973 |

| C2+gkm+CNN+skipBRNN | 99.08 | 97.97 | 0.9986 | 99.10 | 98.14 | 0.9985 |

| kmer+TCN | 99.64 | 99.67 | 0.9995 | 99.76 | 98.74 | 0.9988 |

| Dataset | Coding Number | TISs Number | Time cost (min) | |

| kmer+TCN | frame-specific CNN | |||

| Human | 9,545,915 | 32780 | 20 | 0.8 |

| Mouse | 7,883,216 | 17420 | 15 | 0.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).