Introduction

The incidence of Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) estimates at about 3% of all adult soft-tissue sarcomas [

1]. Pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma (PRMS), also known as anaplatic rhabdomyosarcoma represents a subtype of RMS that usually affects ,while it is very rare in children [

2]. PRMS is classified as a high-grade sarcoma with a nonspecific histologic and immunohistochemical profile, often leading to diagnostic difficulties and poor therapeutic outcomes [

3]. According to WHO classification, RMS can be subdivided into four major histologic variants: embryonal, alveolar, pleomorphic, and spindle cell/sclerosing RMS, the pleomorphic type having worse prognosis compared with the others [

3]. The American College of Surgeons presented the anatomic distribution of soft-tissue sarcomas in adults: almost 50% occur on the thigh and buttock, followed by the torso, upper extremity, retroperitoneum, and head and neck [

4]. Major clinical nomograms of survival rate that can estimate the prognosis of patients with soft-tissue sarcomas include stage, histological grade (an independent indicator of the degree of malignancy), tumor size (which is directly proportional to the risk of development as well as local and distant recurrence), age, anatomic site, and histologic subtype [

5,

6]. Unlike pediatric RMS, which has seen improvements in survival due to standardized treatment protocols, adult RMS continues to have a poor prognosis due to delayed diagnosis and limited response to conventional therapies [

7]. National Cancer Institute indicated a worsen five-year survival rate [

8].

Detailed Case Description

We present the case of a 63-year-old male with a known history of papillary thyroid carcinoma (treated in 2013 with total thyroidectomy (pT3mpNx, R1) followed by radioactive iodine therapy and considered in remission) presented in June 2018 with a rapidly enlarging, ulcerated tumor on the posterior thoracic wall. The objective examination revealed a conscious, cooperative, a temporally and spatially oriented patient, with ECOG 2 performance status, chronic respiratory failure, SaO2 at 95%, and blood pressure at 130/80 mmHg. The local examination showed a tumor formation of PRMS, located in the posterior region of the thorax, of impressive dimensions, with the absence of the thoracic wall on ½ of the tumor size, with vegetative, ulcerated and hemorrhagic lesions (

Figure 1), which underwent surgical resection.

The procedure performed was a wide resection. The surgical specimen was reported as PRMS, established by the histopathological and immunohistochemical results, which revealed positive staining for desmin and MyoD1 (myogenic differentiation 1) and negative staining for h-caldesmon and SMA (smooth muscle actin). The number of mitoses was 4–5 at 10× magnification, and the Ki67 proliferation index was 40%(July 2018).

One month after surgery, the patient returned to the clinic for right axillary pain, with palpation of a 5 cm adenopathic block. An imaging workup included evaluation of the primary site as well as sites of potential metastatic spread (CT scan of trunk, head, and neck) and showed local tumor relapse and regional lymph node involvement and lung metastasis. It was decided to follow up with palliative chemotherapy (Gemcitabine 900 mg/mp iv + Docetaxel 35mg/mp iv) for three months.

Four months after surgery and three months after the initiation of palliative chemotherapy, the patient visited our department for a radiotherapy session.

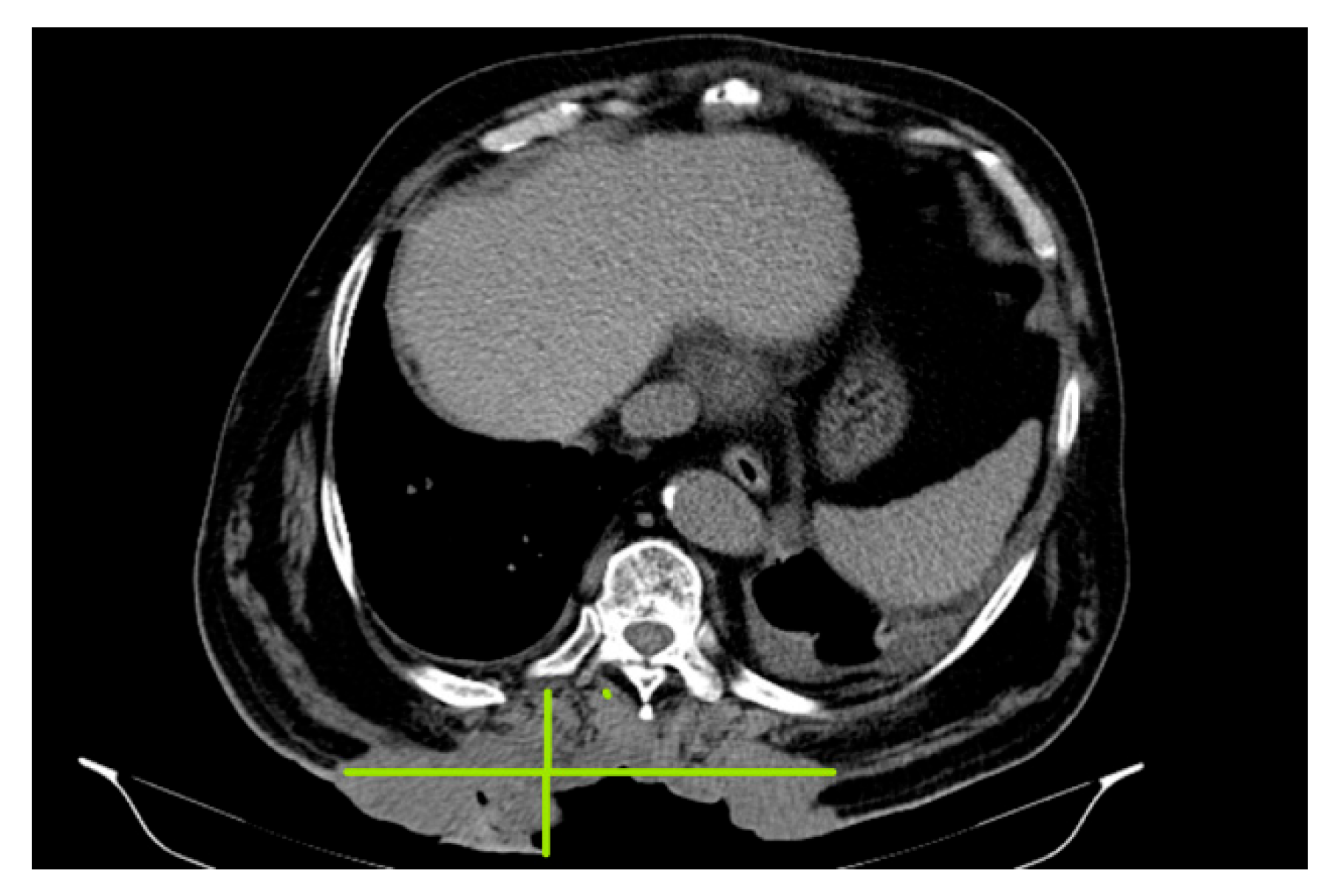

In October 2018, a thoracic

, abdominal-pelvic CT scan was performed with contrast material. The imaging aspect was aggravated from the previous examination (July 2018) by the significant dimensional progression of the mass, with the malignant tumor CT aspect centered at the level of the muscular soft parts corresponding to the posterior thoracic lumbar region (level T7-D2), currently with invasion of the tegument, subcutaneous fat, and embedding of the spinal processes of the T9–T11 vertebral bodies, axial diameters (197/46 mm), and cranio-caudal diameter (212 mm–11/46 anterior); the presence of central necrotic areas at the level of the tumor mass was described (

Figure 2).

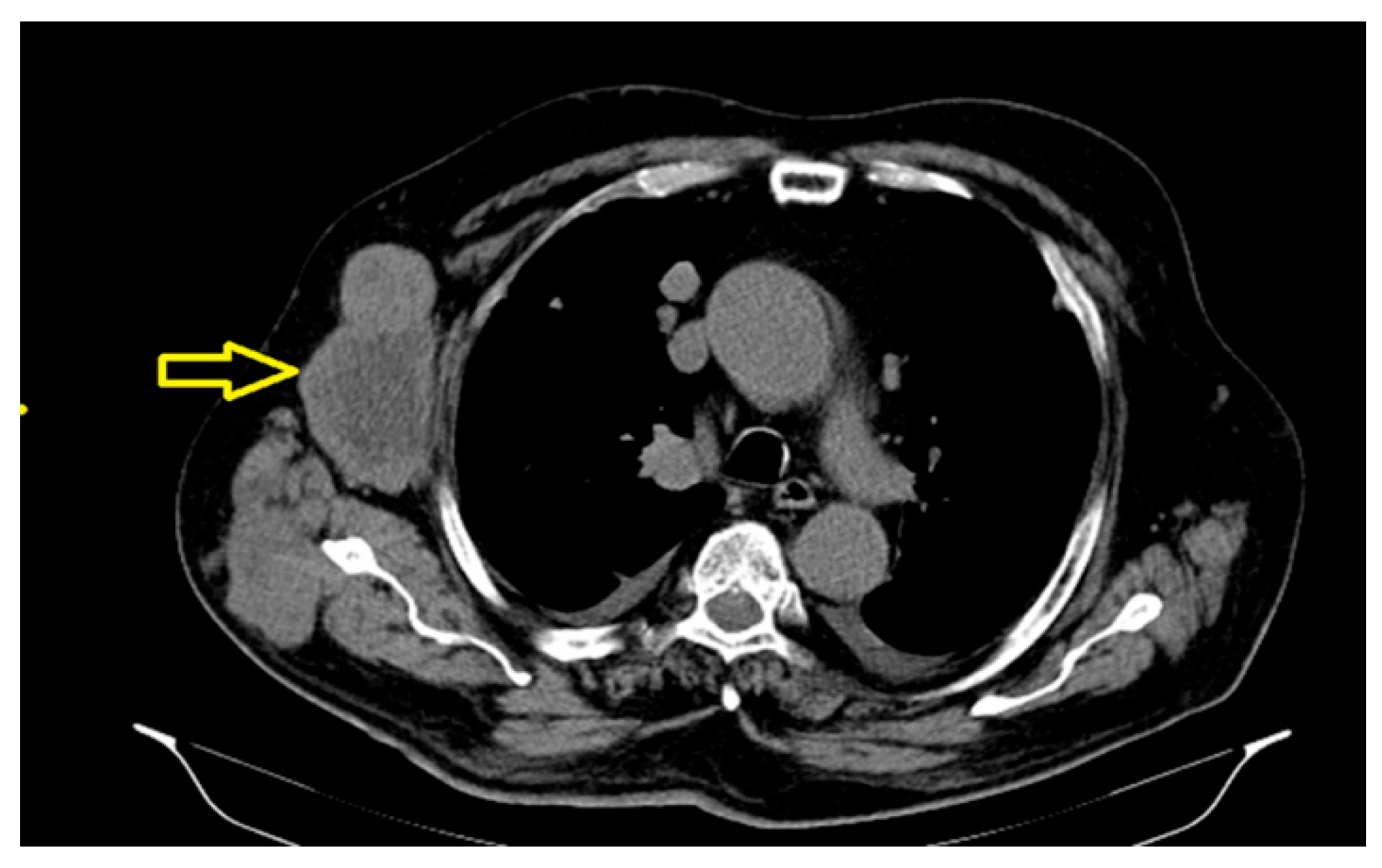

The significant progressions of suggestive lesions for secondary determinations with diffuse distribution in pulmonary parenchyma, pulmonary pleura, and mediastinal pleura were reported, along with the occurrence of pleural fluid in a small quantity bilaterally (

Figure 3).

The significant dimensional progression of the right axillary tumor adenomegaly, currently associated with extensive central necrosis, was also determined (

Figure 4), along with an osteocondensation -focused lesion centered on the left pubic branch with a suspicious aspect for secondary determination.

As a case of PRMS exceeding the therapeutic resources for curative purposes, the patient was recommended for palliative radiotherapy. Palliative electron teleradiotherapy was initiated, for hemostatic purposes, on the target volume: the posterior thoracic tumor (30 Gy, 3 gy/fr). The patient underwent four fractions, up to the total dose DT = 12 Gy, with mediocre tolerance, without clinical response. During this period, the patient’s condition continued to deteriorate gradually, and he required continuous emergency hospitalization for chronic acute respiratory failure (SaO2 at 89%), marked dyspnea, high blood pressure ( 140/100 mmHg), important fatigue, abundant sweating, generalized edema, and acute psychotic episodes with auditory hallucinations, receiving symptomatic, supportive and local hemostatic treatment.

A chest X-ray revealed bilateral diffuse projected alveolite opacities and possibly bilateral mixed pulmonary infiltrates. An interstitial drawing of reticulo-micronodular type accentuated the bilaterally diffuse opacities and small pleural fluid overflow. The medical team continued to offer the patient supportive care, but he deceased four months after the diagnosis. The patient’s prognosis was very poor, with the following evidence: tumor size T4, regional lymph node metastasis N1, distant metastasis M1, unfavorable site (trunk), and histologic grade 3 (poor differentiated, high grade), all leading to the stage IV disease.

The differential diagnosis of soft-tissue sarcoma includes both benign and malign tumors, such as: lipoma, epidermoid cysts, schwannomas, lymphoma and metastatic disease[

9]. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH) (sometimes considered “pleomorphic sarcoma, not otherwise specified”) and pleomorphic leiomyosarcoma (LMS) may also be considered in the differential diagnosis. MFH, although known to occasionally express both desmin and SMA, should not express other specific skeletal muscle markers, such as MyoD1, fast skeletal muscle myosin, myf4 (myogenin),and myoglobin. LMS, a myoid tumor with desmin expression, morphologically has intersecting fascicles, lacks the presence of large polygonal rhabdomyoblasts, and also does not express specific skeletal muscle markers [

10].

Discussion

PRMS is currently defined as a high-grade sarcoma, an aggressive lesion arising in the deep soft tissues of the extremities with a high propensity for metastasis [

11]. Because of its biological and genomic complexity, its clinical behavior and responsiveness to chemotherapy are more similar to those of adult high-grade soft-tissue sarcomas than to those of pediatric RMS [

12,

13].For the great majority of soft-tissue sarcomas, there is no known

etiology, but a number of associated or predisposing factors can be attributed to the following environmental means:

Certain clinical syndromes are associated with a

genetic predisposition for the development of sarcoma (for example: Li–Fraumeni syndrome, Werner syndrome, neurofibromatosis type 1, Garner syndrome, Becwith–Wiedemann syndrome, Costello syndrome)[

15].

PRMS belongs to one of the main types of soft-tissue sarcomas with nonspecific genetic alterations, frequently mutated genes including the TP53 tumor suppressor, type 1 NF1, and alpha-thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome X-linked (ATRX); the latter one correlates with the alternative lengthening of telomeres [

15,

16]. On

histology, PRMS is characterized by pleomorphic rhabdomyoblasts, multinucleated giant cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and atypical mitotic figures [

17]; the nuclear size is threefold larger than that of “typical” tumor cells. Positive nuclear staining for desmin, muscle-specific actin, and myogenin (Myf4) on immunohistochemistry are found in over 95% of tumors [

18].

The American College of Surgeons Patterns of Care Study for adult STS showed that 23% of patients had metastatic disease at presentation; PRMS usually presents as a large deep-seated mass with early metastasis, especially to the lungs [

19], and a complete pulmonary metastasectomy was feasible in ⅓ of the patients [

20]. The United Kingdom Department of Health has published criteria for patients with soft-tissue lesions: a tumor >5 cm; a painful lump that is increasing in size, deep to the muscle fascia and recurrence after previous excision [

21].Our patient met all these criteria.

The College of American Pathologists, the 2017 American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)/Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) cancer staging manual, and the French Federation of Cancer Centers Sarcoma Group (FNCLCC) incorporate differentiation, mitotic rate, and extent of necrosis as the following:

The

diagnosis of a suspicious soft-tissue mass includes cross-sectional imaging such as MRI for the evaluation of the extremities, trunk, head and neck, a CT for retroperitoneal and visceral sarcomas and a PET scan for prognostication, grading and determining the response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy [

22].

The

treatment of RMS includes chemotherapy for the primary cytoreduction and eradication of metastatic disease, radiotherapy for local residual disease, and surgery resection [

23].Chemotherapy regimens for high-grade soft-tissue sarcoma include Doxorubicin (25mg/m

2/day), Ifosfamide (2,000–3,000mg/m

2/day) and Mesna (1,200–1,800 mg/m

2/day) for 21 days [

23]. Radiotherapy is recommended to all patients with RMS; the dose for metastatic disease is 50.4 Gy for all sites, according to guidelines [

23]. In almost all cases, appropriate surgical resection is a prerequisite for the curative treatment of soft-tissue sarcoma, with varying levels of success. These procedures include marginal resection or excisional biopsy, wide resection (an intermediate procedure) and radical resection. The chest wall tumors appear to do worse after surgical excision if the margins are positive [

23]. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is individualized in patients with more common adult-type RMS. In those treated with initial surgery and with higher-risk tumors (≥5 cm, grade 2 or 3, tumors located deep to fascia, locally recurrent tumors, positive margins at surgery), undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy (taking into consideration the patient’s performance status) and considering comorbid factors (including age), tumor size and location, histological subtype and toxicity [

24],the evolution is unfavorable. In our case, the patient presented all these risk factors that limited the administration of higher chemotherapeutic doses and stronger combinations.

Many reports have evaluated patient and tumor characteristics to determine the

prognostic factor for disease-free survival (DFS) or overall survival (OS) and local recurrence (LR). The most powerful predictor for DFS and OS is the AJCC TNMG stage of the tumor, highlighting that the stage 4 disease reflects poor prognostic implications [

22]. The overall survival in adults is 18 months; in our case, the patient died approximately six months after the diagnosis.

The five-year survival overall is about 30%, for the localized disease 35%, and for the metastatic disease 11% [

25].

Conclusion

We presented a case of PRMS, which started in the sixth decade of the patient’s life, with rapid post-surgery recurrence and with metastasis to the lungs, lymph nodes, and bone—all these characteristics are specific according to the literature. The peculiarity of the case is represented by the tumor dimensions, their appearance, and the fulminant evolution toward exitus.

Because of the rarity of soft-tissue sarcomas and the numerous forms in which they can present with respect to tumor histology, site, and size, there are many options related to optimal management. Furthermore, the delivery of treatment requires a multimodality team that includes experienced pathologists, radiologists, surgeons, and oncologists. The next generation of molecular genetic testing will represent an important tool in approaching the appropriate treatment and the improved prognosis of all types of soft-tissue sarcomas.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.O and R.E.M; Methodology, B.O.; Software, B.O..; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, B.O; Writing – Review & Editing R.E.M. Validation, B.O and R.E.M.; Resources, B.O.; Data Curation, B.O and R.E.M; Visualization, B.O and R.E.M .; Supervision B.O and R.E.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare they have no financial interests. This manuscript received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- In: Weiss SW, Goldblum J, Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, editors. Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors. 4 th ed., St. Louis: CV Mosby; 2001. p. 785-835.

- Fletcher, C.D.; Gustafson, P.; Rydholm, A.; et al. Clinicopathologic re-evaluation of 100 malignant fibrous histiocytomas: prognostic relevance of subclassification. J Clin Oncol 2001, 19, 3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours, 5th ed, International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2020. Vol 3.

- Lawrence, W., Jr.; Donegan, W.L.; Natarajan, N.; et al. Adult soft tissue sarcomas. A pattern of care survey of the American College of Surgeons. Ann Surg 1987, 205, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariani, L.; Miceli, R.; Kattan, M.W.; et al. Validation and adaptation of a nomogram for predicting the survival of patients with extremity soft tissue sarcoma using a three-grade system. Cancer 2005, 103, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, A.; Dileo, P.; Casanova, M.; et al. Rhabdomyosarcoma in adults: a retrospective analysis of 171 patients treated at a single institution. Cancer. 2003, 98, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esnaola, N.F.; Rubin, B.P.; Baldini, E.H.; et al. Response to chemotherapy and predictors of survival in adult rhabdomyosarcoma. Ann Surg. 2001, 234, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultan, I.; Qaddoumi, I.; Yaser, S.; et al. Comparing adult and pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma in the surveillance, epidemiology and end results program, 1973 to 2005: an analysis of 2,600 patients. J Clin Oncol 2009, 27, 3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakya, S.; Banneyake, E.L.; Cholekho, S.; Singh, J.; Zhou, X. Soft tissue sarcoma: clinical recognition and approach to the loneliest cancer. Explor Musculoskeletal Dis. 2024, 2, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Obaid, I.H. Soft tissue Sarcomas: Immunohistochemistry evaluation by Desmin, Myosin, Smooth muscle Actin and Vimentin. JFac Med Baghdad 2020, 62, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shern, J.F.; Chen, L.; Chmielecki, J.; et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis of rhabdomyosarcoma reveals a landscape of alterations affecting a common genetic axis in fusion-positive and fusion-negative tumors. Cancer Discov. 2014, 4, 216–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furlong, M.A.; Mentzel, T.; Fanburg-Smith, J.C. Pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma in adults: a clinicopathologic study of 38 cases with emphasis on morphologic variants and recent skeletal muscle-specific markers. Mod Pathol 2001, 14, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maki, R.G. Pediatric sarcomas occurring in adults. J SurgOncol 2008, 97, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogevinas, M.; Becher, H.; Benn, T.; et al. Cancer mortality in workers exposed to phenoxy herbicides, chlorophenols, and dioxins. An expanded and updated international cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 1997, 145, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elizabeth H Baldini, Jason L Hornick. Pathogenic factors in soft tissue and bone sarcomas. www.uptodate.com. Nov. 2024.

- Liau, J.Y.; Lee, J.C.; Tsai, J.H.; et al. Comprehensive screening of alternative lengthening of telomeres phenotype and loss of ATRX expression in sarcomas. Mod Pathol 2015, 28, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mentzel, T.; Katenkamp, D. Pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma in adults: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 19 cases. Virchows Arch. 1999, 435, 534–539. [Google Scholar]

- M Fatih Okcu, John Hicks, Philip J Lupo. Rhabdomyosarcoma in childhood and adolescence:Epidemiology, pathology and molecular pathogenesis. www.uptodate.com. 2024.

- Lawrence, W., Jr; Donegan, W.L.; Natarajan, N.; Mettlin, C.; Beart, R.; Winchester, D. Adult soft tissue sarcomas. A pattern of care survey of the American College of Surgeons. Ann Surg 1987, 205, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billingsley, K.G.; Burt, M.E.; Jara, E.; et al. Pulmonary metastases from soft tissue sarcoma: analysis of patterns of diseases and postmetastasis survival. Ann Surg 1999, 229, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, S.; Peach, A.H. Diagnosis and management of soft tissue sarcoma. BMJ 2010, 341, c7170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christopher W Ryan, Janelle Meyer. Clinical presentation, diagnostic evaluation and staging of soft tissue sarcoma. www.uptodate.

- M Fatih Okcu, John Hicks. Rhabdomyosarcoma in childhood and adolescence and adulthood: Treatment. www.uptodate.

- Robert G Maki. Adjuvant and neoadjuvant chemotherapy for soft tissue sarcoma of the extremities. www.uptodate.

- Drabbe, C.; Benson, C.; Younger, E.; et al. Embryonal and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma in adults: real-life data from a tertiary sarcoma centre. Clin Oncol. 2020, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).