1. Introduction

Wetlands have been natural hubs of economic, social, and environmental value, providing services to regulate water and air quality, recycle nutrients, and offer recreational spaces [

1,

2,

3]. Furthermore, lake-wetland ecosystems also provide water resources vital for human civilization [

4,

5]. Their role in climate change mitigation through carbon sequestration is also increasingly recognized, as wetlands store approximately 20–30% of the Earth’s soil carbon while covering only 5–8% of the land surface [

6,

7].

Hence, the sustainable use of wetlands is even more important now as the pressures of anthropogenic activities, climate change, and population growth impose stricter limitations on their existence [

8,

9,

10]. The preservation of the wetlands is crucial as their recovery processes are slow and limited to the environmental and anthropogenic conditions [

11,

12]. Beyond ecological concerns, wetlands also provide crucial services such as groundwater recharge, flood mitigation, water purification, and agricultural support [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Despite these benefits, global wetland areas are declining rapidly, with over 35% lost since 1970 [

17,

18].

In this regard, the planning of water resources management efforts is generally focused on the assessment of the existing state of the water source, and the simulation of the possible future threats, such as future meteorological conditions due to climate change, and potential solutions that the stakeholders of the hydrological system would accept [

19,

20]. The potential solution acceptable for the stakeholders may have different of goals, monitored by economic [

21], environmental [

22], socio-economic [

23] indicators or combinations of these dimensions [

24].

The presented study investigates the case of Lake Marmara, Türkiye, a wetland of national importance and also an important water source of the Gediz River Basin system. A series of water management choices has led the Lake to dry up completely in the present situation. Within the scope of the PRIMA foundation-funded “Mara-Mediterra” project, the hydrological model of the Lake has been developed, and the impacts of climate change, land use change, and initial storage amount of Lake Marmara have been investigated [

25]. In this study, through modelling and scenario analysis, it is revealed that the lateral flows feeding the Lake are insufficient to maintain a minimum ecological volume, namely in each scenario applied for the simulation of monthly water balance of the Lake Marmara resulted a complete dry up condition, without any inflow contribution from Gördes reach.

Hence, this study investigates the possible solutions to restore Lake Marmara, through a water accounting model to ensure the water balance of not just the Lake but also the Gördes Dam and the demand sites related to these water resources. The previous study [

25] has considered the Lake Marmara watershed inclusively, excluding any water allocation from Gördes Dam, the main water source of Lake Marmara, and the demand sites related to the Lake, only focusing on the water balance of the Lake by lateral flows created by precipitation and drainage pattern of irrigated agricultural lands. Therefore, the presented study includes the scenarios covering a water allocation plan from Gördes Dam and Tabaklı reach directly to Lake Marmara. The scenarios are created regarding the combination of values such initial storage amount of Gördes Dam, changes in lateral flows and evaporation under future climate change conditions, irrigation supply priorities, irrigation demand management options, and the option of an investment in water diversion from a nearby reach of the Gediz River, Tabaklı reach, to Lake Marmara, as scenario options.

The results of the study, aside from the specific outcomes for Lake Marmara, highlight the importance of including each element of a hydrological system in an integrated water resources management principle and considering each investment option not only through present but also through future conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

Lake Marmara is located in the west of Turkey within the boundaries of the Gediz River Basin. The lake covers an area of 68 km

2 and is officially announced as a “Wetland of National Importance” with its ecosystem characteristics that host a large number of aquatic birds, various mammals, reptiles, and fish species [

26]. In and around the lake, aside from the extensive agricultural activities, which have a long history [

27], fishing and local tourism used to provide considerable economic advantages to the majority of the residents and communities. The lake water was mostly supplied by the Gördes Reach until the Gördes Dam was completed in 2011, which is primarily intended to contribute to the drinking water supply of Izmir’s urban area [

28]. The dam’s construction created additional rivalry for residential, irrigational, and environmental water demands in the region. The dam’s design and construction caused lower water allocation for the lake, while Gördes Reservoir failed to meet domestic and irrigational water demands due to leakage problems. This situation increased the vulnerability of the Lake, so the renewability of the wetland system has been severely damaged. Furthermore, the lake’s lateral inflows and runoff from precipitation were insufficient to maintain the requisite storage volume for environmental needs during dry periods (i.e., early summer to late fall), which also damaged its resilience. In addition, further irrigation water withdrawals from the lake exacerbated the water shortage, namely recoverability of the system has been lost. As a result, Lake Marmara has steadily dried up from 2019 until the present (

Figure 2) leaving restoration of the system as the only solution. Lake Marmara holds great significance as it plays a crucial role in the water balance of the Gediz River Basin.

The stakeholders of the area, especially the farming community, demand that the Lake be restored to its former self. The interviews conducted with the local farmers within the scope of the “Mara-Mediterra” Project highlight the influence of the Lake on the product quality in the area. As the farmers stated, the humidity, once emitted from the Lake, used to protect their products, which are mostly Sultana grapes and olives, from extreme temperatures, preventing them from wilting and frost, so granting a higher production quality.

Meteorological data for Lake Marmara were gathered by investigating three adjacent meteorological stations, Manisa, Akhisar, and Salihli of the Turkish State Meteorological Services (DMI). Following a Thiessen method analysis, the Salihli meteorology station was determined to be the most suited, accounting for the representation of 97% of the lake drainage area. Thus, a collection of daily meteorological data collected at the Salihli station during a 32-year period (1980-2012) was used as input into the hydrological model.

To depict the terrestrial topography of the model region, ASTER-DEM version 3 data with a spatial resolution of 30 m were used as the basin’s Digital Elevation Model [

29]. The data on basin topography and hydromorphologic parameters were further analysed using the ArcGIS program. Climate change data for RCP 8.5 [

30,

31] were obtained from the Global Climate Model (GCM) Downscaled Data Portal by the Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture, and Food Security [

32].

2.2. Methods

In order to investigate dynamic water allocation options and simulate various conditions and constraints on the study area, a set of models has been used and/or developed. The main mathematical model developed for this study is the water accounting model developed in the WEAP software [

33]. Additionally, the study uses key results of a previous paper by Gunacti et al. (2022) regarding the land use change and hydrological modelling of the Lake Marmara system. The mentioned study investigated the hydrological potential of Lake Marmara under land use and climate change impacts. The land use change was modelled by the TerrSet software’s Land Use Change Modeller (LCM) tool to project the land cover map of 2050 around Lake Marmara. On the other hand, the Hydrologic Modelling System (HEC-HMS) was used to model the hydrological processes of the Lake Marmara system for the baseline period of 1997-2012 and the future projection of 2050.

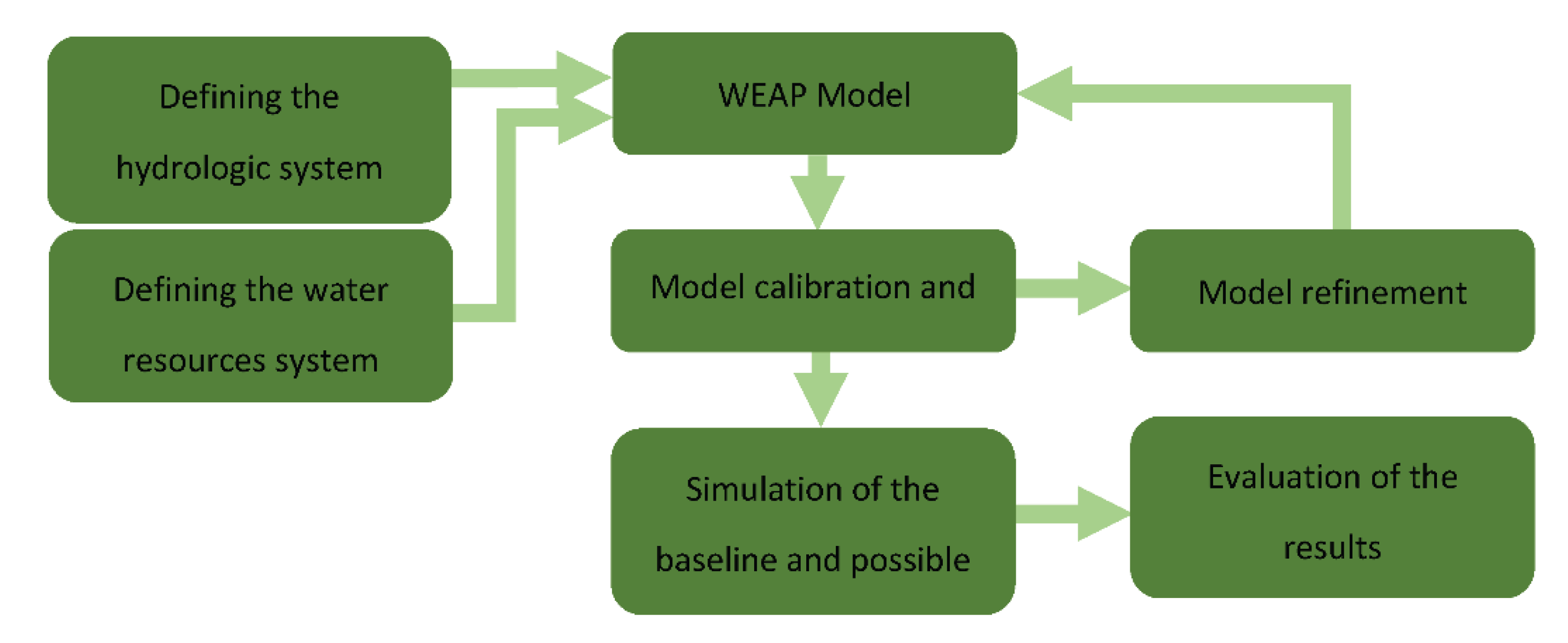

As stated, the water allocation modeling component of the study is conducted by the WEAP software developed by the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI). WEAP is a software tool that is commonly used in studies that are focused on integrated approaches to water resources planning problems. WEAP provides several built-in models for rainfall runoff and infiltration, evapotranspiration, crop requirements and yields, surface water/groundwater interaction, and instream water quality on a monthly time scale. It also serves to identify the variables and equations on the relations between the elements of the basin and the processes involved. WEAP is linked to a GIS interface to build up the topology of the entire basin and the links between demand and supply nodes. The basin system is defined in terms of its supply sources (e.g., rivers, creeks, groundwater, reservoirs, and desalination plants); withdrawal, transmission, and wastewater treatment facilities; water demands; pollution generation; and ecosystem requirements (

Figure 3). The modeling flowchart of a common WEAP Model is given in

Figure 4.

Different allocation patterns lead to different responses to existing water demands. These patterns affect the whole system’s survival in terms of water quantity. The WEAP model relies on scenario analysis to evaluate the effects of policy changes. The scenarios generated in this study are based on climate change and the implementation of demand management actions. Furthermore, the storage time series of Lake Marmara and the unmet demand of the Lake Marmara region have been calculated for each scenario and presented in the results section.

2.3. Scenario Development

In the previously mentioned study by Gunacti et al. (2022), a set of developed scenarios investigated the hydrological potential of Lake Marmara by lake water budget calculations, where the irrigational water demand management, impacts of land use and climate change, and initial reservoir storage were the scenario variables. Unfortunately, in this group of scenarios, Lake Marmara dried out in each one of them.

This brings us to the current study, in which the scope of modelling has been widened to a larger extent, as every demand management scenario under either climate or land use change falls short of sustaining the minimum environmental requirements. Since this section requires much more complex calculations, the WEAP model has been employed in this segment. The scenarios developed in this section involve actions such as allocating water from other branches or considering a sustainably working Gördes Dam.

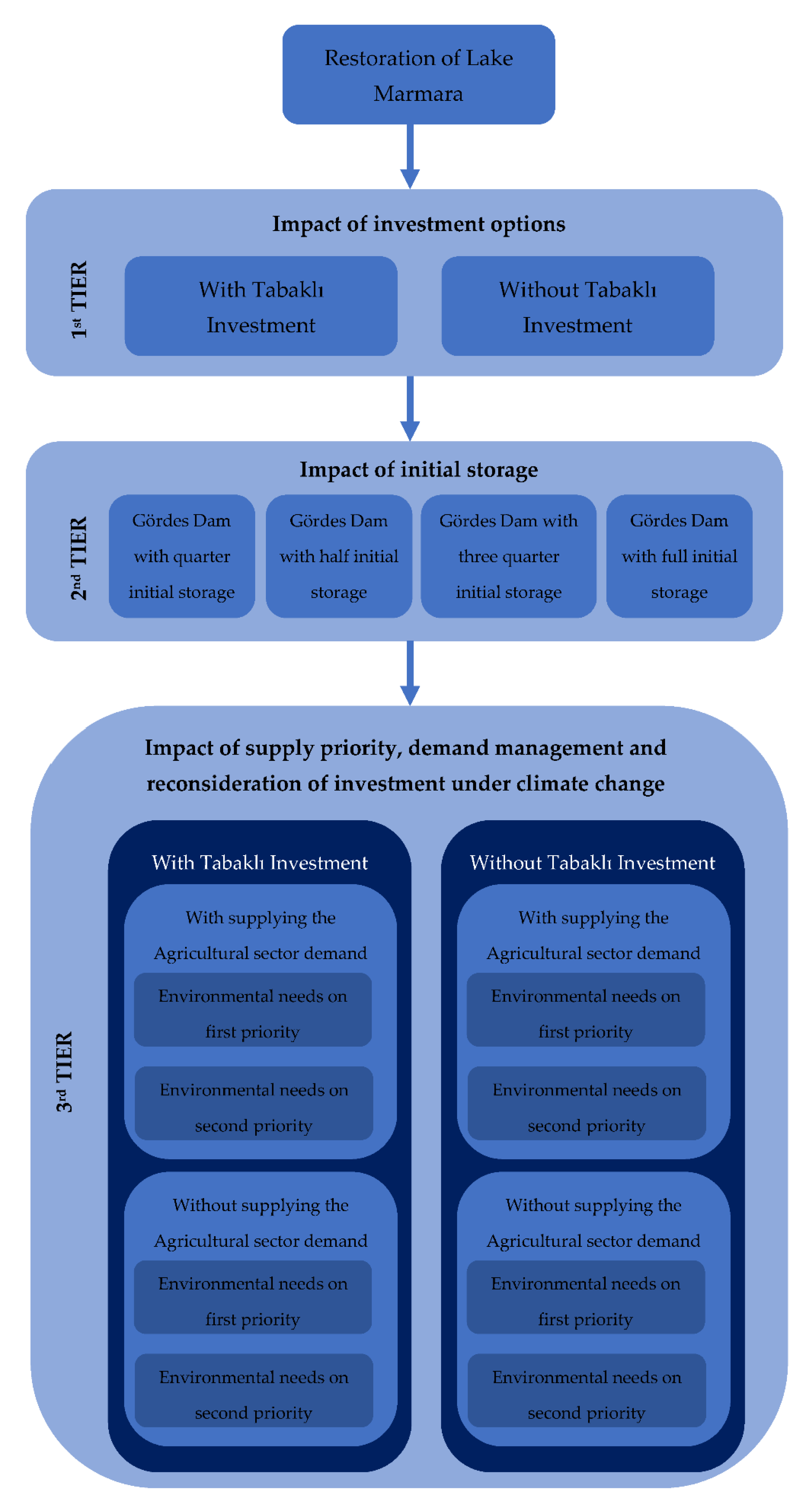

In particular, scenarios first evaluate the necessity of Tabaklı reach investment, which is to allocate 20 hm

3 of water each year from Tabaklı reach to Lake Marmara. Then, if the investment is not necessary, the second level of scenarios investigates the impact of initial storage of Gördes Dam on the storage of Lake Marmara and the total unmet demand of Lake Marmara’s irrigational needs. This is investigated in 4 sub-scenarios where the initial storage of Gördes Dam is the quarter, half, three quarters, and total of its storage capacity. Hence, according to the results of this level of scenarios, another level of scenarios investigates the future conditions in two variations, either with or without allocating irrigational water to the agriculture sector. This tier of scenarios also investigates the satisfaction of the minimum and maximum ecological water needs (

Figure 5 and

Table 1 and

Table 2).

3. Results

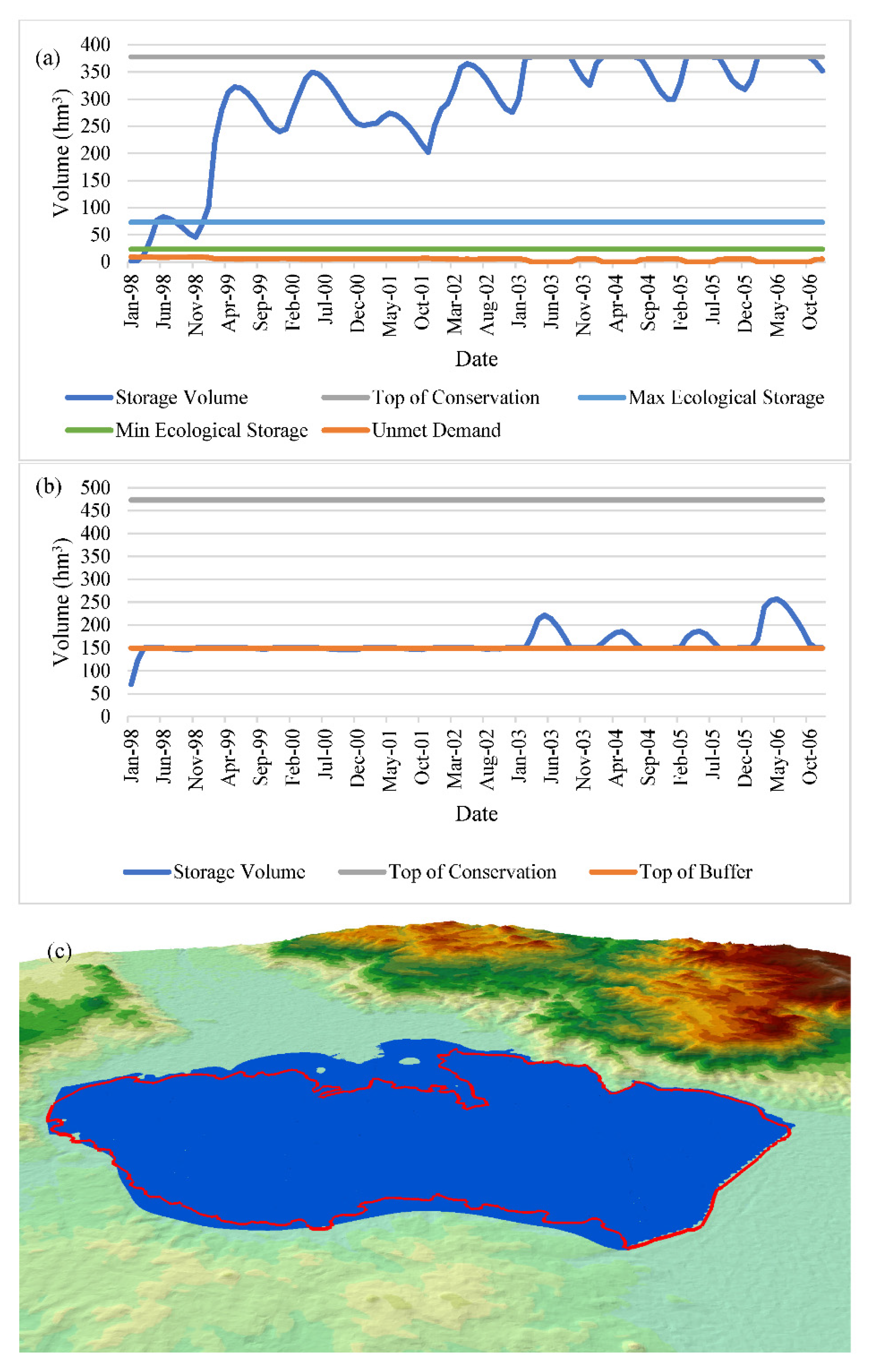

The first tier of scenarios, where the necessity of Tabaklı investment, which is to allocate 20 hm

3 of water to Lake Marmara, is investigated, reveals that in the short-term results, this investment (scenario S1) is not necessary for the environmental needs of the Lake (

Figure 6), when compared to the case without the investment (scenario S2) (

Figure 7). In both cases Gördes Dam retains the minimum volume required to function (150 hm

3), and Lake Marmara satisfies both the annual minimum (23.47 hm

3) and maximum ecological water demand (72.85 hm

3) assumed according to the future dry year scenario and baseline scenario Lake volumes investigated in Gunacti et al. (2022). The ArcScene 3D render visuals of the Lake at the end of the simulation period, with the average Lake boundary comparisons, are also provided in each scenario result for better visual understanding.

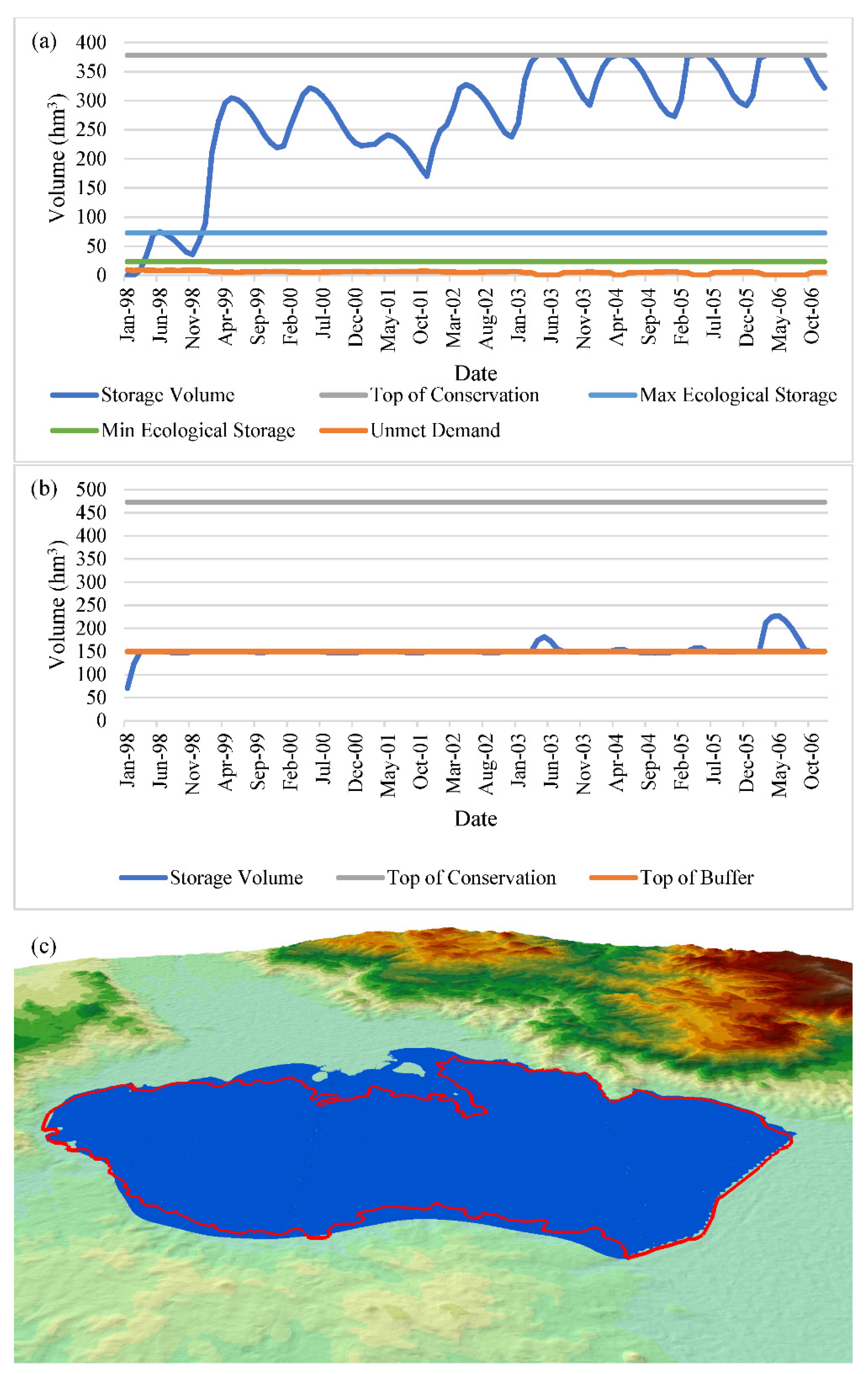

Therefore, the scenarios continue on without the Tabaklı investment into the second tier, where the impact of initial storage in Gördes Dam is investigated. The scenarios S2.1, S2.2, S2.3, and S2.4 indicate the initial storage in Gördes Dam to be a quarter, half, three-quarters, and the total of its storage capacity, respectively. In this tier of scenarios, every scenario has satisfied the annual minimum and maximum ecological water needs and the minimum storage amount in Gördes Dam (

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11). This outcome indicates that there is no need to wait until the Gördes Dam is half, three-quarters, or entirely full to start its operation. The Dam can operate even in lower conditions, which is proven in the first tier of investigation by using the observed initial storage amount (40.2 hm

3), which was lower than a quarter of the total storage capacity (118.25 hm

3).

This brings us to the third tier of scenarios, where the meteorological conditions of 2050 are simulated not only for one year but also for nine years, the same length as the 1998-2006 period. In this section of the scenarios, the calculated 2050 streamflow output of Gunacti et al. (2022) is used as input for Gördes Dam for nine repetitive years to observe its mid-term impacts on the Lake Marmara system. This tier of scenarios also investigates three more conditions: providing irrigational water for agriculture (or not), supply priority of environmental water needs being the first (or the second), and lastly, re-introducing the option of Tabaklı investment, would it be necessary in the future (or not) (

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14,

Figure 15,

Figure 16,

Figure 17,

Figure 18 and

Figure 19).

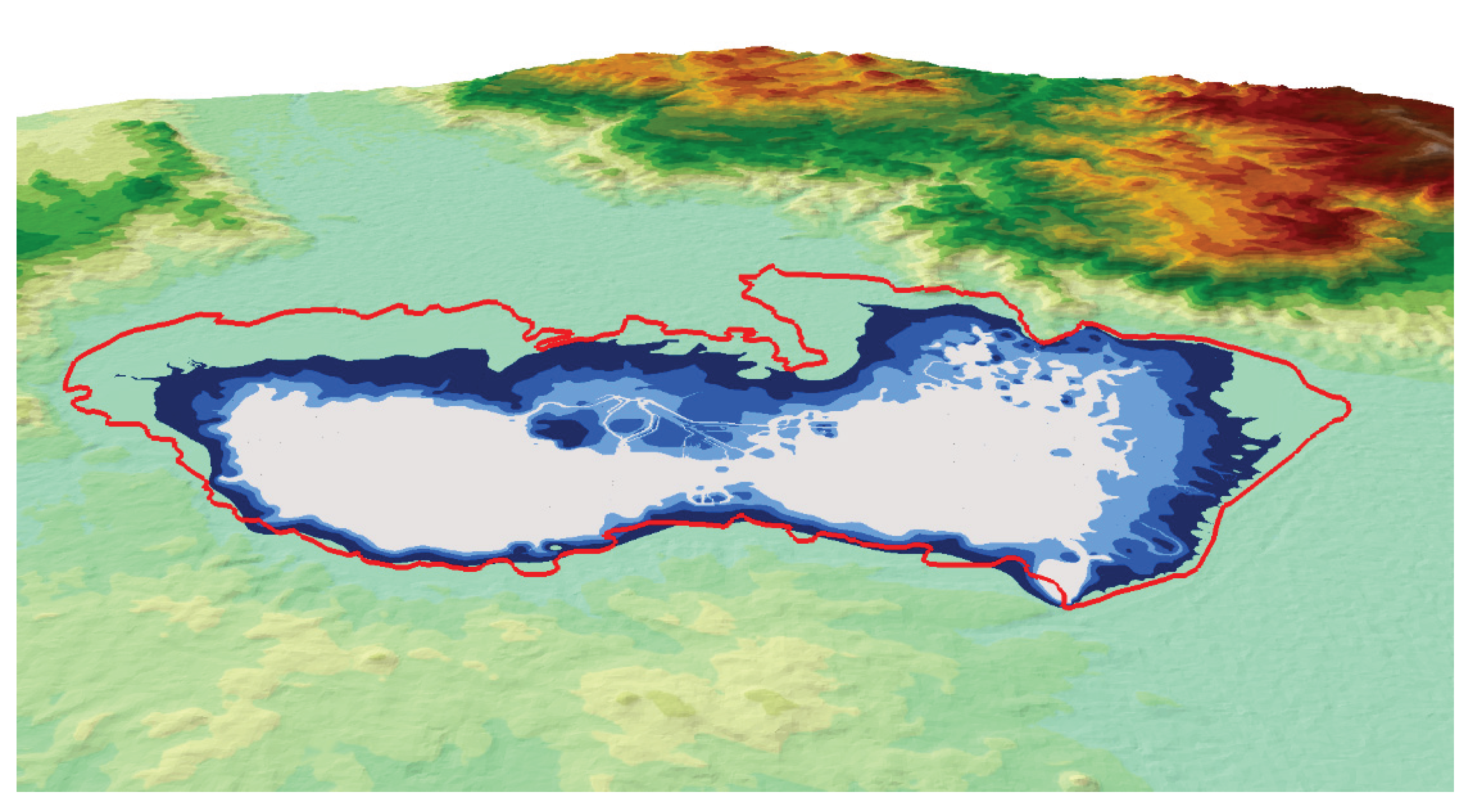

In order to stress the worst-case scenario results, which is the S2.1.1.2, where the 2050 meteorological conditions are in effect without the Tabaklı investment and the supply priority of environmental needs is in second order, the average seasonal storage of Lake Marmara is 3D rendered in

Figure 20.

4. Discussion

The restoration of wetlands under competing water demands and increasing climatic stress represents one of the most pressing challenges in contemporary water resources management. This study provides a case-specific, yet broadly transferable, framework for evaluating the feasibility and effectiveness of dynamic water allocation strategies aimed at wetland recovery. By focusing on Lake Marmara—a degraded yet ecologically significant wetland in western Türkiye—the study contributes to the growing body of literature emphasizing the need for integrative, adaptive approaches to basin-scale water governance [

15,

19].

The findings of this study demonstrate that Lake Marmara’s ecological water needs can be sustained under current hydrological and demand conditions without major infrastructural investments, such as the proposed Tabaklı water diversion. This aligns with previous observations in similar Mediterranean-climate basins where prioritization of environmental flows and operational flexibility in dam management can yield ecological benefits without compromising water supply security [

20,

22]. Importantly, the results challenge the prevailing assumption that large-scale infrastructure is always a prerequisite for environmental flow restoration, instead highlighting the critical role of strategic reallocation within existing supply systems.

However, when future meteorological projections for 2050 are incorporated, the findings reveal a notable shift in system behavior. Under these conditions, scenarios that did not include the Tabaklı investment or deprioritized environmental needs consistently resulted in unsatisfactory outcomes. This suggests that while the lake’s restoration is feasible under present conditions, long-term sustainability will require proactive adaptation—both through strategic investments and policy reforms that institutionalize ecological priorities. These results support the growing consensus that future-ready water management must integrate climate projections into operational planning to avoid maladaptation [

34,

35].

Furthermore, the relatively negligible impact of agricultural water demand on lake recovery under present conditions is notable. It suggests that short-term ecological goals need not come at the expense of agricultural productivity, a finding that may encourage stakeholder alignment in restoration planning. Nevertheless, this balance may not hold under scenarios of intensified land use, population growth, or prolonged drought. Therefore, continuous monitoring and re-evaluation of demand hierarchies will be necessary to ensure adaptive capacity is maintained.

This study also reinforces the utility of scenario-based modeling approaches for evaluating complex hydrological systems. The WEAP model enabled the simulation of multifaceted interactions among storage capacities, supply priorities, and environmental needs across temporal and climatic scales. Such tools are instrumental in translating uncertain futures into actionable planning options—a methodological priority increasingly recognized in wetland conservation literature [

24].

From a broader perspective, the case of Lake Marmara exemplifies a common challenge in semi-arid regions where wetlands are situated downstream of intensively managed water infrastructure. These systems often suffer from ecological marginalization, and their restoration is frequently impeded by institutional inertia or lack of integrated basin-wide planning. This study demonstrates that integrated and adaptive allocation strategies, grounded in robust modeling and scenario planning, can offer a viable pathway toward wetland sustainability—even in resource-constrained contexts.

Future research should focus on expanding the spatial and temporal scope of modeling to include groundwater interactions, economic cost-benefit analyses of restoration investments, and ecosystem service valuation. Moreover, participatory modeling frameworks that incorporate stakeholder input and local ecological knowledge may enhance model legitimacy and implementation feasibility. Finally, cross-basin comparative studies could provide further insights into the generalizability of the presented approach and help refine best practices for wetland restoration in other vulnerable hydrological systems.

5. Conclusions

This study has explored a range of water resource management strategies and meteorological scenarios to identify viable pathways for the restoration of Lake Marmara—a nationally significant wetland and an ecological hotspot within the Gediz River Basin of Türkiye. Once a thriving aquatic ecosystem supporting biodiversity, agriculture, and local livelihoods, Lake Marmara has suffered severe hydrological stress in recent years due to the combined effects of upstream dam operations, insufficient lateral inflows, irrigation withdrawals, and prolonged dry conditions. The modeling conducted within the scope of the PRIMA-funded “Mara-Mediterra” project sought to determine the feasibility of alternative water allocation strategies under current and future climate and land use conditions.

The analysis was structured around a multi-tiered scenario framework. The first tier assessed the necessity of the Tabaklı reach investment—an infrastructural intervention designed to divert 20 hm³ of water annually to the lake. Results from this tier revealed that under current hydrological and demand conditions, the ecological requirements of Lake Marmara could be satisfied without the Tabaklı investment, thus deeming it unnecessary in the short term. In the second tier, the role of Gördes Dam’s initial storage capacity was examined across several thresholds. It was shown that even at one-quarter of its total capacity, the dam could allocate sufficient water to sustain the lake’s minimum ecological water needs, thus offering operational flexibility in storage-constrained conditions.

The third tier introduced projected 2050 meteorological conditions to stress-test the robustness of previous findings. Under these scenarios, the sustainability of the lake became increasingly dependent on strategic planning decisions. Notably, when ecological water needs were assigned lower priority relative to domestic or agricultural uses, or when the Tabaklı investment was excluded, the lake failed to meet its minimum environmental thresholds in most years. Conversely, scenarios that prioritized environmental demands and incorporated the Tabaklı investment yielded significantly more favourable outcomes for lake restoration. These findings underline the necessity of initiative-taking water policy planning that anticipates future variability and integrates ecological priorities explicitly into allocation hierarchies.

Furthermore, the study demonstrated that current levels of agricultural water demand did not significantly hinder the restoration of the lake, suggesting that near-term ecological goals can be met without compromising irrigational use—provided that dam operations are optimized. However, this equilibrium is fragile and may not hold under increased climatic stress or population growth, reinforcing the need for adaptive management mechanisms.

On a broader level, the research emphasizes the importance of using integrated, case-specific hydrological modeling tools—such as WEAP—to support sustainable water governance in complex basin systems. It advocates for a paradigm shift in water management where environmental flow requirements are no longer residual considerations but are embedded as central constraints in planning processes. By demonstrating that Lake Marmara’s restoration is not only theoretically feasible but also operationally attainable under carefully designed allocation schemes, the study offers a replicable framework for the rehabilitation of degraded wetlands in other semi-arid regions facing similar water scarcity challenges.

In conclusion, while the degradation of Lake Marmara reflects the cumulative impact of long-standing mismanagement and climatic stress, its future need not be defined by further decline. Through strategic planning, prioritized ecological investments, and adaptive governance, the lake’s hydrological and ecological functions can be revitalized. However, the window of opportunity is narrow, and timely action will be crucial to avoid irreversible ecological loss and to secure the resilience of both natural ecosystems and the communities that depend on them.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.G. and C.P.C.; Methodology and formal analysis, M.C.G. and C.P.C.; Writing—original draft and review and editing, M.C.G. and C.P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and APC were funded by the EU PRIMA Foundation project entitled “Mara-Mediterra”, grant number 2121.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA). Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Wetlands and Water Synthesis; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mitsch, W.J.; Gosselink, J.G. Wetlands, 5th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, N.C.; Fluet-Chouinard, E.; Finlayson, C.M. Global extent and distribution of wetlands: Trends and issues. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2018, 69, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlayson, C.M.; Davies, G.T.; Moomaw, W.R. . The Second Warning to Humanity – Providing a Context for Wetland Management and Policy. Wetlands 2019, 39, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Zang, Y.; Wu, C.; Zhao, Z. Spatiotemporal dynamics of wetlands and their future multi-scenario simulation in the Yellow River Delta, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 353, 120193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgham, S.D.; Megonigal, J.P.; Keller, J.K.; Bliss, N.B.; Trettin, C. The carbon balance of North American wetlands. Wetlands 2006, 26, 889–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahlik, A.M.; Fennessy, M.S. Carbon storage in US wetlands. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudgeon, D.; Arthington, A.H.; Gessner, M.O.; Kawabata, Z.I.; Knowler, D.J.; Lévêque, C.; Naiman, R.J.; Prieur-Richard, A.H.; Soto, D.; Stiassny, M.L.J.; Sullivan, C.A. Freshwater biodiversity: Importance, threats, status and conservation challenges. Biol. Rev. 2006, 81, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vörösmarty, C.J.; McIntyre, P.B.; Gessner, M.O.; Dudgeon, D.; Prusevich, A.; Green, P.; Glidden, S.; Bunn, S.E.; Sullivan, C.A.; Reidy Liermann, C.; Davies, P.M. Global threats to human water security and river biodiversity. Nature 2010, 467, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, R.R.; Barchiesi, S.; Beltrame, C.; Finlayson, M.; Galewski, T.; Harrison, I.; ...; Walpole, M. State of the world’s wetlands and their services to people: A compilation of recent analyses; Secretaría de la Convención de Ramsar, 2015.

- Zedler, J.B.; Kercher, S. Wetland resources: Status, trends, ecosystem services, and restorability. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 39–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Mateos, D.; Power, M.E.; Comín, F.A.; Yockteng, R. Structural and functional loss in restored wetland ecosystems. PLoS Biol. 2012, 10, e1001247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junk, W.J.; An, S.; Finlayson, C.M.; Gopal, B.; Květ, J.; Mitchell, S.A.; Mitsch, W.J.; Robarts, R.D. Current state of knowledge regarding the world’s wetlands and their future under global climate change: A synthesis. Aquat. Sci. 2013, 75, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keddy, P.A.; Fraser, L.H.; Solomeshch, A.I.; Junk, W.J.; Campbell, D.R.; Arroyo, M.T.K.; Alho, C.J.R. Wet and wonderful: The world’s largest wetlands are conservation priorities. Bioscience 2009, 59(1), 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acreman, M.; Holden, J. How wetlands affect floods. Wetlands 2013, 33, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, S.; Qimeng, N.; Zhigang, L. Impacts of the land use transition on ecosystem services in the Dongting Lake area. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1422989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.C.; Finlayson, C.M. Global wetland outlook: State of the world’s wetlands and their services to people. In Proceedings of the Ramsar Convention Secretariat; Ramsar Convention Secretariat: Gland, Switzerland, October, 2018; pp. 2020–5. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, N.C.; van Dam, A.A.; Finlayson, C.M.; McInnes, R.J. Worth of wetlands: Revised global monetary values of coastal and inland wetland ecosystem services. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2019, 70, 1189–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthington, A.H.; Kennen, J.G.; Stein, E.D.; Webb, J.A. Recent advances in environmental flows science and water management—Innovation in the Anthropocene. Freshw. Biol. 2018, 63, 1022–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, J.A.; Watts, R.J.; Allan, C.; et al. Adaptive management of environmental flows. Environ. Manag. 2018, 61, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatamkhani, A.; Moridi, A.; Asadzadeh, M. Water allocation using ecological and agricultural value of water. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 33, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Yang, B.; Li, Y. Study of artificial water replenishment for wetland restoration. Water Environ. J. 2022, 36(1), 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hou, Y.; Xue, Y. Water resources carrying capacity of wetlands in Beijing: Analysis of policy optimization for urban wetland water resources management. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 161, 1180–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ayllón, S. New Strategies to Improve Co-Management in Enclosed Coastal Seas and Wetlands Subjected to Complex Environments: Socio-Economic Analysis Applied to an International Recovery Success Case Study after an Environmental Crisis. Sustainability. 2019, 11, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunacti, M.C.; Gul, G.O.; Cetinkaya, C.P.; Gul, A.; Barbaros, F. Evaluating Impact of Land Use and Land Cover Change Under Climate Change on the Lake Marmara System. Water Resour Manage 2022, 37, 2643–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, H. Surface Water. In Water resources of Turkey, 1st ed.; Harmancıoğlu, N.B., Altınbilek, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2020; pp. 127–158. [Google Scholar]

- Kılıç, N.; Dağdeviren, R.; Fural, Ş.; Kükrer, S.; Makaroğlu, Ö. Vegetation History of Lake Marmara (W. Türkiye) and Surrounding Area during the Last 700 Years. C. R. Acad. Bulg. Sci. 2023, 76, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmancıoğlu, N.B.; Cetinkaya, C.P.; Barbaros, F. Sustainability Issues in Water Management in the Context of Water Security. In Water resources of Turkey, 1st ed.; Harmancıoğlu, N.B., Altınbilek, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2020; pp. 517–533. [Google Scholar]

- ASTER (2021) ASTER Global Digital Elevation Model (GDEM) V03. Available online: https://search.earthdata.nasa.gov/ (accessed on November 2021).

- Moss, R.H.; Edmonds, J.A.; Hibbard, K.A.; et al. The next generation of scenarios for climate change research and assessment. Nature 2010, 463, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Vuuren, D.P.; Edmonds, J.; et al. The representative concentration pathways: An overview. Clim. Change 2011, 109, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Downscaled GCM data portal. Available online: https://ccafs.cgiar.org (accessed on April 2024).

- Sieber, J. WEAP: Water Evaluation and Planning System User Guide; Stockholm Environment Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl-Wostl, C.; Kabat, P.; Möltgen, J. Adaptive and Integrated Water Management: Coping with Complexity and Uncertainty; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gain, A.K.; Giupponi, C.; Wada, Y. Measuring global water security towards sustainable development goals. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 124015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 3.

WEAP model of the Gediz River Basin.

Figure 3.

WEAP model of the Gediz River Basin.

Figure 4.

Modeling process of a common WEAP model.

Figure 4.

Modeling process of a common WEAP model.

Figure 5.

Developed scenario flowchart.

Figure 5.

Developed scenario flowchart.

Figure 6.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (352.18 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S1 scenario.

Figure 6.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (352.18 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S1 scenario.

Figure 7.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (321.96 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2 scenario.

Figure 7.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (321.96 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2 scenario.

Figure 8.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (322.49 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2.1 scenario.

Figure 8.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (322.49 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2.1 scenario.

Figure 9.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (323.51 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2.2 scenario.

Figure 9.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (323.51 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2.2 scenario.

Figure 10.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (325.89 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2.3 scenario.

Figure 10.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (325.89 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2.3 scenario.

Figure 11.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (326.91 hm3) 3D ArcScene render compared to the average Lake boundary under the S2.4 scenario.

Figure 11.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (326.91 hm3) 3D ArcScene render compared to the average Lake boundary under the S2.4 scenario.

Figure 12.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (99.15 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2.1.1.1 scenario.

Figure 12.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (99.15 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2.1.1.1 scenario.

Figure 13.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (10.99 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2.1.1.2 scenario.

Figure 13.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (10.99 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2.1.1.2 scenario.

Figure 14.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (99.15 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2.1.2.1 scenario.

Figure 14.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (99.15 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2.1.2.1 scenario.

Figure 15.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (11.29 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2.1.2.2 scenario.

Figure 15.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (11.29 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2.1.2.2 scenario.

Figure 16.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (99.15 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2.2.1.1 scenario.

Figure 16.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (99.15 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2.2.1.1 scenario.

Figure 17.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (23.27 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2.2.1.2 scenario.

Figure 17.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (23.27 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2.2.1.2 scenario.

Figure 18.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (150.03 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2.2.2.1 scenario.

Figure 18.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (150.03 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2.2.2.1 scenario.

Figure 19.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (24.29 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2.2.2.2 scenario.

Figure 19.

Storage curves of (a) Lake Marmara, and (b) Gördes Dam, and (c) Lake Marmara end of simulation period (24.29 hm3) 3D ArcScene render (blue) compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2.2.2.2 scenario.

Figure 20.

3D ArcScene render of the average seasonal storage of Lake Marmara from darkest shade of blue to lightest representing Spring, Summer, Winter, and Autumn, respectively, compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2.1.1.2 scenario.

Figure 20.

3D ArcScene render of the average seasonal storage of Lake Marmara from darkest shade of blue to lightest representing Spring, Summer, Winter, and Autumn, respectively, compared to the average Lake boundary (red) under the S2.1.1.2 scenario.

Table 1.

Developed scenario descriptions for 1998-2006 meteorological conditions.

Table 1.

Developed scenario descriptions for 1998-2006 meteorological conditions.

| Scenario No. |

Scenario Descriptions |

|

S1 (with Tabaklı investment) |

Gördes Dam is considered to be active, allocating water with the demand priorities of (1) Domestic Use, (2) Environmental needs (Lake Marmara), (3) Agriculture, (Gördes Dam initial storage is 40.2 hm3 (observed value)), Tabak Reach allocates 20 hm3 of water to Lake Marmara annually, Lake Marmara’s top operational priority is to store water; spill water is allocated to the rest of the Gediz River Basin system |

|

S2 (without Tabaklı investment) |

Gördes Dam is considered to be active, allocating water with the demand priorities of (1) Domestic Use, (2) Environmental needs (Lake Marmara), (3) Agriculture, (Gördes Dam initial storage is 40.2 hm3 (observed value)), Lake Marmara’s top operational priority is to store water; spill water is allocated to the rest of the Gediz River Basin system |

|

S2.1 (without Tabaklı investment, initial storage = ¼ of storage cap.) |

Gördes Dam is considered to be active, allocating water with the demand priorities of (1) Domestic Use, (2) Environmental needs (Lake Marmara), (3) Agriculture, (Gördes Dam initial storage is 118.25 hm3 (¼ of storage capacity)), Lake Marmara’s top operational priority is to store water; spill water is allocated to the rest of the Gediz River Basin system |

|

S2.2 (without Tabaklı investment, initial storage = ½ of storage cap.) |

Gördes Dam is considered to be active, allocating water with the demand priorities of (1) Domestic Use, (2) Environmental needs (Lake Marmara), (3) Agriculture, (Gördes Dam initial storage is 236.50 hm3 (1/2 of storage capacity)) Lake Marmara’s top operational priority is to store water; spill water is allocated to the rest of the Gediz River Basin system |

|

S2.3 (without Tabaklı investment, initial storage = ¾ of storage cap.) |

Gördes Dam is considered to be active, allocating water with the demand priorities of (1) Domestic Use, (2) Environmental needs (Lake Marmara), (3) Agriculture, (Gördes Dam initial storage is 354.75 hm3 (3/4 of storage capacity)), Lake Marmara’s top operational priority is to store water; spill water is allocated to the rest of the Gediz River Basin system |

|

S2.4 (without Tabaklı investment, initial storage = Total of storage cap.) |

Gördes Dam is considered to be active, allocating water with the demand priorities of (1) Domestic Use, (2) Environmental needs (Lake Marmara), (3) Agriculture, (Gördes Dam initial storage is 377 hm3 (Total of storage capacity)), Lake Marmara’s top operational priority is to store water; spill water is allocated to the rest of the Gediz River Basin system |

Table 2.

Developed scenario descriptions for 2050 meteorological conditions.

Table 2.

Developed scenario descriptions for 2050 meteorological conditions.

| Scenario No. |

Scenario Descriptions |

|

S2.1.1 (without Tabaklı investment, initial storage = ¼ of storage cap., with 2050 meteorologic conditions) |

S2.1.1.1 (environmental needs are first priority) |

Gördes Dam is considered to be active, allocating water with the demand priorities of (1) Domestic Use, (2) Environmental needs (Lake Marmara), (3) Agriculture, (Gördes Dam initial storage is 118.25 hm3 (¼ of storage capacity)), Lake Marmara’s top operational priority is to store water; spill water is allocated to the rest of the Gediz River Basin system The lateral flow results of Gunacti et al. (2022) hydrological model have been used as inflow data in the WEAP model |

|

S2.1.1.2 (environmental needs are second priority) |

|

S2.1.2 (without Tabaklı investment, initial storage = ¼ of storage cap., with 2050 meteorological conditions, no water allocation to agriculture) |

S2.1.2.1 (environmental needs are first priority) |

Gördes Dam is considered to be active, allocating water with the demand priorities of (1) Domestic Use, (2) Environmental needs (Lake Marmara), (3) Agriculture, (Gördes Dam initial storage is 118.25 hm3 (¼ of storage capacity)), Lake Marmara’s top operational priority is to store water; spill water is allocated to the rest of the Gediz River Basin system The lateral flow results of Gunacti et al. (2022) hydrological model have been used as inflow data in the WEAP model No water is allocated to the agricultural sector |

|

S2.1.2.2 (environmental needs are second priority) |

|

S2.2.1 (with Tabaklı investment, initial storage = ¼ of storage cap., with 2050 meteorologic conditions) |

S2.2.1.1 (environmental needs are first priority) |

Gördes Dam is considered to be active, allocating water with the demand priorities of (1) Domestic Use, (2) Environmental needs (Lake Marmara), (3) Agriculture, (Gördes Dam initial storage is 118.25 hm3 (¼ of storage capacity)), Lake Marmara’s top operational priority is to store water; spill water is allocated to the rest of the Gediz River Basin system Tabak Reach allocates 20 hm3 of water to Lake Marmara annually, The lateral flow results of Gunacti et al. (2022) hydrological model have been used as inflow data in the WEAP model |

|

S2.2.1.2 (environmental needs are second priority) |

|

S2.2.2 (with Tabaklı investment, initial storage = ¼ of storage cap., with 2050 meteorological conditions, no water allocation to agriculture) |

S2.2.2.1 (environmental needs are first priority) |

Gördes Dam is considered to be active, allocating water with the demand priorities of (1) Domestic Use, (2) Environmental needs (Lake Marmara), (3) Agriculture, (Gördes Dam initial storage is 118.25 hm3 (¼ of storage capacity)), Lake Marmara’s top operational priority is to store water; spill water is allocated to the rest of the Gediz River Basin system Tabak Reach allocates 20 hm3 of water to Lake Marmara annually, The lateral flow results of Gunacti et al. (2022) hydrological model have been used as inflow data in the WEAP model No water is allocated to the agricultural sector |

|

S2.2.2.2 (environmental needs are second priority) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).