1. Introduction

The global population is aging but the factors contributing to normal versus pathological aging are still uncertain. Finding a comprehensive definition that fully explains the concept of aging is difficult, considering that this is not a single reductionist phenomenon based on a unidirectional pathway as many try to describe [1].

In recent years, the concept of inflammaging was proposed referring to a basal state of mild inflammation in the elderly population [2], present systemically without clinically relevant manifestations for a long time [3]. This is interesting considering that many diseases typical of elderly share an inflammatory pathogenesis and an asymptomatic stage.

Furthermore, age is considered the primary risk factor for neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson's and Alzheimer’s disease, as shown by their increasing frequency in a world that continues to age.

Among the many alterations that occur with ageing, one concerns the microbiota [4]. An altered balance between beneficial and pro-inflammatory bacteria has been observed in aged mice and it is believed that this may be associated with the degeneration of the enteric nervous system (ENS) during the aging process [5], suggesting the existence of an interaction between commensal microorganisms and neurodegenerative diseases.

Dysbiosis may not only arise as part of the physiological aging process, but it may also result from inflammaging itself, representing an adaptation of the microbiota to the changes induced by this chronic inflammatory state. Adding an additional layer of complexity, there is growing evidence that the pathological condition is associated with changes in the gut microbiota due to lifestyle-related variations. Discriminating the primary cause of dysbiosis among the various hypotheses proposed in affected patients remains a significant challenge for research.

In the literature, several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of microbiota-targeted interventions for various neurological disorders. For instance, treating dysbiosis in patients with multiple sclerosis can reduce inflammation and reactivate the immune system [6]. Similar research is also promising in Alzheimer’s disease [7,8].

Considering these findings and the fact that, in recent years, the prevalence of PD is increasing more rapidly than other neurodegenerative disorders leading to the alarming expression "Parkinson’s pandemic" [9,10], it becomes particularly relevant to explore potential microbiota-targeted therapies for this neurological condition.

In this review, we aimed at performing an analysis of the interactions between the gut microbiota-brain axis and PD, exploring the mechanisms through which these connections may influence the onset and progression of the disease, particularly in the small intestine. Furthermore, we provide an updated overview of current scientific knowledge on the modulation of this axis for therapeutic purposes, highlighting its potential clinical implications and future perspectives in the treatment of PD.

2. Gut Microbiota

The gut microbiota is the collection of bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses that inhabit our gastrointestinal tract [4]. It is estimated that each person has about 3.8x1013 bacterial cells all over the body, the equivalent of the number of human cells, thus meaning that each of us has a ratio of bacteria to human cells closer to 1:1 [11].

In the microbiota of a healthy individual, there are mainly strict anaerobes, and up to 50 different bacterial phyla can be identified, although Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes are mainly dominant [12]. The functions performed by these microorganisms vary, starting from their contribution to metabolism or protection against pathogens. Recently, research has focused on the discovery of the role of the gut microbiota in maintaining health as well as in favoring the development of several diseases including neurodegenerative conditions [12].

The gut microbiome, on the other hand, is the collective genetic information contained within the microbiota [13]. The number of genes encoded by the bacteria residing in the gut is approximately one hundred times that of the host individual, with 3.3 million genes identified compared to the 22,000 genes comprising the entire human genome [14]. These data are even more interesting if interpreted from the viewpoint of interindividual diversity: while each person shares 99.9% of their genetic heritage with others, they differ by 80-90% in terms of the microbiome [14]. Therefore, adopting a different perspective where we consider the human genetic heritage as the sum of human and microbial traits, we understand the importance of characterizing and deepening aspects related to the microbiome, which is one of the main objectives of the Human Microbiome Project (HMP) [15].

For conducting the analyses of the microbial composition, the most common approach is to use the 16S rRNA marker gene. This choice is made not only because this marker is present in all microorganisms but also because it strikes the right balance between a conserved sequence (which allows for accurate alignment) and variation that permits phylogenetic analysis [15]. The information derived from this type of analysis provides a valuable starting point but remains inherently limited. As in other areas of medicine, leveraging omics approaches offers a more comprehensive perspective of the microbiota, not as a collection of individual components but as a complex ecosystem, where interactions are examined not only among microorganisms but also between them and the host. Currently, studies utilizing these technologies are still limited [16,17]; however, as their number increases, they will provide more detailed insights into metabolic pathways and bioactive compounds, contributing to a deeper understanding of the microbiota's role.

Given the complexity of the gut microbiome, it is understood that there are still many steps to take to gain a deeper knowledge, but if research continues in this direction, it is possible to leverage these enormous diversities to develop personalized and targeted therapies for individual patients [14].

2.1. The Effects of Drugs on the Microbiota

Awareness of the interactions between drugs and the microbiota is growing in parallel with the increasing number of studies aimed at exploring these connections.

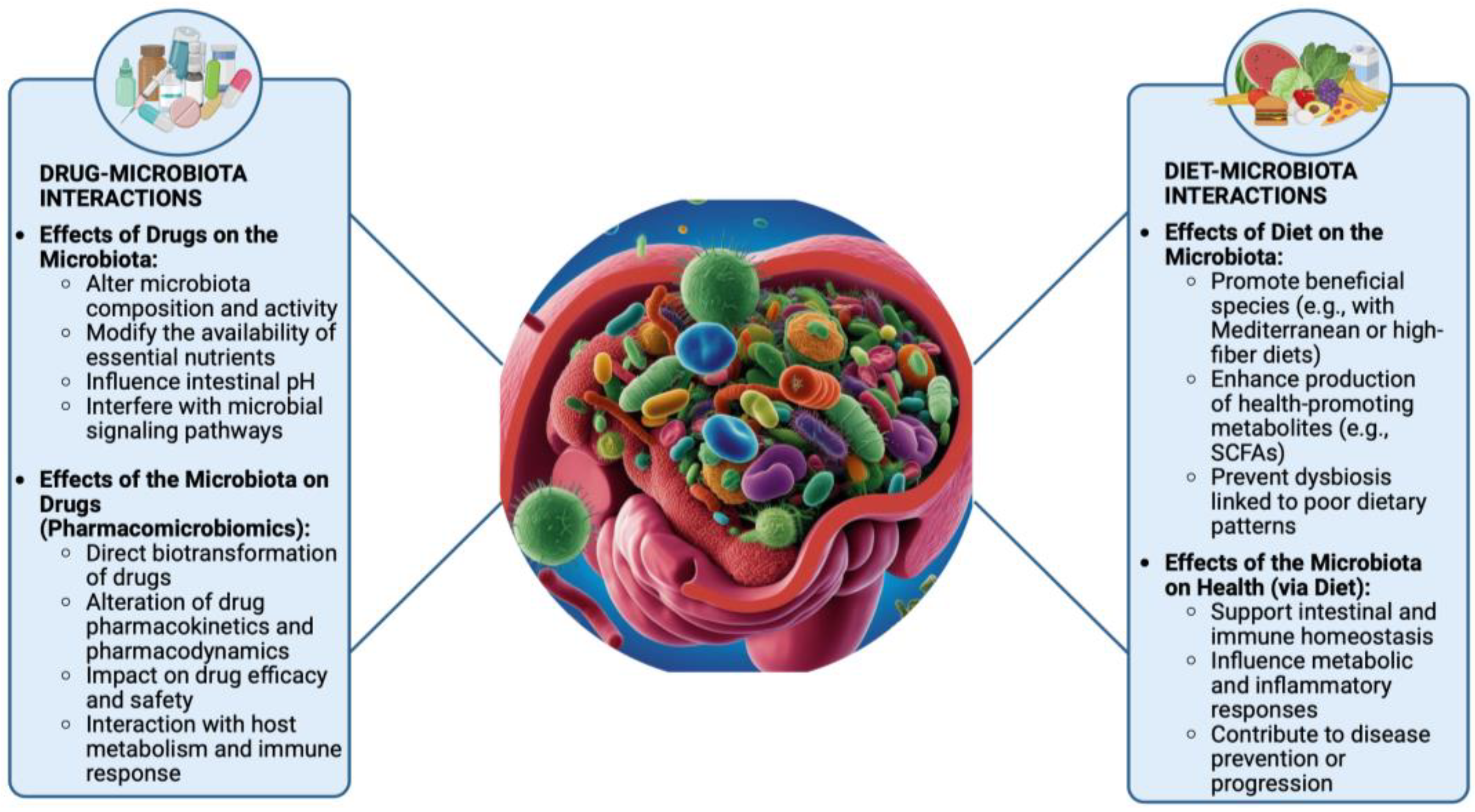

It is now well established that there is a bidirectional communication between these two elements. On one hand, drugs can indirectly influence the composition and activity of the microbiota by modifying microenvironments. A well-known example is the use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), which by increasing the pH of the stomach favors oral microbiota to abnormally travel to the intestine and causes dysbiosis by disrupting the existing specific commensal microbial GI distribution [18]. Another mechanism by which drugs may alter the intestinal microflora involves promoting the growth of specific bacterial species or, conversely, reducing their numbers—an effect observed even with non-antibiotic drugs that exhibit antimicrobial activity [19]. On the other hand, microorganisms can also influence drugs, giving rise to the concept of pharmacomicrobiomics [20,21]. The gut microbiota can modify both the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a drug, potentially altering its efficacy and safety profile, leading to side effects or even adverse reactions. This is achieved either through direct drug transformation or by modulating metabolism and/or the immune system [22,23]. Indeed, gut microorganisms can produce enzymes involved in drug biotransformation reactions, or even generate molecules that compete with the drug for the same substrates [24]. It is intuitive to assume that antibiotics, which directly target bacterial cells, can significantly alter the gut microbiota. The overuse of antibiotics has been observed to cause the development of many disorders associated with intestinal dysbiosis [25]. Since most commercially available antibiotics have broad-spectrum activity, their effects are not limited to pathogens but also impact the healthy gut flora [26]. Consequently, resistant bacteria may develop, further disrupting the microbiota balance [27]. Less obvious is the idea that even non-antibiotic drugs can lead to similar alterations. However, numerous studies have already demonstrated this association [28,29]. Given that an increasing number of patients today undergo polypharmacotherapy, a recent interesting study examined the possible effects of multi-drug therapy and provided evidence for wide changes in metabolic potential, taxonomy and resistome in relation to commonly used drugs, further reinforcing the findings [30]. However, as shown in

Figure 1, pharmacological treatments are just one of the many factors that can impact the gut microbiota.

2.2. The Impact of Diet on the Microbiota

The gut microbiota, thanks to its vast interindividual variability, can be considered our second fingerprint. Given the great diversity within this ecosystem, there is no single configuration that can be defined as a "healthy microbiota" [13]. This implies that different approaches may be pursued to improve it. Well-balanced dietary patterns—such as the Mediterranean diet, a high-fiber diet, or a balanced plant-based diet—can lead to significant differences in microbial composition, and all are potentially associated with improved overall well-being [31]. Conversely, an unbalanced diet leads to various types of dysbiosis, and since the role of the gut microbiota in maintaining health is now widely recognized, it is evident that poor dietary habits can contribute to a wide range of health disorders. To assess the health status of our gut bacterial ecosystem, a reliable indicator appears to be the measurement of alpha diversity [32]. Notably, this measure increases significantly until adulthood, and studies have shown that many diseases—even very different ones—share the common feature of reduced alpha diversity [34]. It has been observed that higher consumption of refined sugars, processed foods, and other key components of the so-called Western diet is associated with a decrease in gut microbiota diversity [35]. Conversely, adopting the Mediterranean diet as a lifestyle choice has been shown to enhance both microbial diversity and richness [36].

Many factors influencing the gut microbiota are established early in life, including the mode of delivery [37] and maternal or early childhood diet [38]. For example, the gut microbiota of children with a normal or high body mass index (BMI) tends to show greater diversity compared to that of underweight children [39]. In contrast, in adults, the pattern appears reversed—overweight or obese individuals, or those with a high BMI, often exhibit reduced alpha diversity [40,41]. These observations highlight that, in order to effectively modulate the gut microbiota to support overall health, it is more beneficial to focus on long-term dietary patterns rather than isolated nutrient interventions, which may be promising but still require further investigation.

3. Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis

Over the past 70 years, numerous studies have examined the interactions between two complex systems—the gut and the brain—introducing and gradually reinforcing the concept of the "gut-brain axis" [42,43,44]. These early findings have been further supported by physiological experiments, advanced experimental techniques [45] and investigations using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) [46]. Together, this body of research has revealed a close interconnection between the central nervous system (CNS) and the ENS. More recently, growing interest in the role of gut microorganisms has led to a broader perspective, culminating in the concept of the "microbiota–gut–brain axis"[47]. These three components—the microbiota, the gut, and the brain—communicate bidirectionally. Microorganisms can influence gut barrier, motility and secretion, which in turn affect brain function. Conversely, the brain can modulate the gut environment and microbiota composition through neural, endocrine, and immune pathways [47]. These new findings allow us to identify various therapeutic applications of the microbiota-gut-brain axis, such as the use of neuromodulators in the treatment of digestive disorders, both to manage pain and address the inflammatory component [48]. Some early observations also suggest the possibility of treating brain disorders with microorganisms. For example, fecal transplantation has been shown to be effective in relieving the symptoms of autistic patients with digestive problems and dysbiosis, leading to a decrease in both neurological and gastrointestinal symptoms [49].

An innovative approach is the use of optogenetic technology. Originally developed to investigate the gut-brain interconnections, it has also been found to enable precise control over gut microbiota metabolism and the regulation of genetically engineered bacteria for therapeutic purposes. [50]. Therefore, the microbiota-gut-brain axis represents a promising therapeutic target for a variety of pathological conditions, including neurological diseases. However, further research is essential to deepen our understanding, enhance the reliability of findings, and enable their translation into routine clinical practice.

4. Involvement of the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Parkinson’s Disease

PD is named after the British physician James Parkinson, who first described its key features in his 1817 work, An Essay on the Shaking Palsy. PD is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder and one of the most disabling conditions affecting the CNS [51,52]. The pathological hallmark of PD is the deposition of aggregated α-synuclein in the neurons, so called Lewy bodies [53] and progressive loss of striatal dopamine nerve terminals in the caudate and putamen resulting in dopamine depletion[53,54]. Manifestations of PD include motor symptoms and non-motor symptoms. The signs that most characterize the pathology are bradykinesia, resting tremor, rigidity and postural instability. In addition to these, patients are subjected to secondary motor function impairments such as gait impairments, micrographia, speech difficulties, dysphagia and dystonia [54]. It has been observed that certain enteric clinical manifestations, leading to bloating, constipation, nausea, or weight loss, occur in PD patients many years before appearance of motor symptoms [55]. There are several risk factors that predispose individuals to the onset of PD, many of which share the ability to influence the gut microbiota, suggesting a possible interaction between them [56]. For the initial evaluation of the involvement of the gut-brain axis in PD, the contribution of preclinical research has been fundamental. It has been shown that germ-free mice exhibit dysregulated dopamine activity in various areas of the brain [57]. Indeed, the gut microbiota can produce various neurotransmitters, including dopamine [47]. Alterations in the gut microbiota may negatively affect the immune response, thereby influencing neuroinflammation. Under conditions of dysbiosis, systemic inflammation can occur, potentially triggering protein aggregation that may propagate to the brain via the vagus nerve. More broadly, it is understood that the microbiota influences brain activity and function through the vagus nerve [58].

In PD, accumulations of phosphorylated α-synuclein are initially found in the ENS and may reach the CNS through the vagus nerve, which itself does not appear to suffer direct damage [59,60]. These observations suggest that the ENS facilitates the spread of the disease [60]. However, further studies are needed to definitively determine whether this represents a key pathogenetic event in PD. Based on current evidence, it is believed that such interactions contribute to disease development, albeit with interindividual variability.

In addition to immune and neural pathways, certain metabolic processes also operate along the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Gut microorganisms can produce trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), a metabolite associated with neuroinflammation and protein misfolding—hallmarks observed in PD patients [58]. Recent studies have investigated the link between TMAO and PD, suggesting that elevated circulating levels of TMAO may play a role in the pathogenesis and progression of the disorder. For instance, increased TMAO levels have been shown to exacerbate motor impairments and promote neuroglial inflammation in MPTP-induced murine models of PD [61]. Other researchers have shown that reduced plasma concentrations of TMAO in patients with early-stage PD are associated with a more rapid escalation of L-DOPA therapy and an increased risk of progression to dementia, suggesting a potential prognostic value of this metabolite [62]. Although these results may appear conflicting, it is important to consider that TMAO is a metabolite whose production depends on the interaction between diet and the gut microbiota. Its formation involves hepatic oxidation of trimethylamine (TMA), which is generated by bacterial fermentation of dietary precursors such as choline. Consequently, such discrepancies among studies may reflect differences in the populations analyzed, particularly in terms of dietary habits, which in turn influence the composition of the gut microbiota. Once the pathophysiological role of TMAO in PD will be clarified, it may be of interest to implement targeted dietary interventions in patients by modulating the intake of foods rich in its precursors such as red meat, egg yolk, and full-fat dietary products [63] in order to influence systemic TMAO levels.

If the enteric accumulation of pathological α-synuclein is replicated in experimental models, it subsequently appears in the brain; conversely, if α-synuclein pathology originates elsewhere, it still spreads to the enteric nervous system, causing damage there [64]. Finally, it has been observed that patients with PD often exhibit dysbiosis, with alterations that are both qualitative and quantitative. Up to 54% of PD patients present with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), which is associated not only with gastrointestinal symptoms but also with more severe motor fluctuations [65]. In light of these observations, it appears plausible that the bidirectional interaction between the gut and the CNS in the pathogenesis of PD is significantly influenced by intestinal dysbiosis, which leads to alterations in the metabolic activity of the gut microbiota. Within this context, the hypothesis that modulating the gut-microbiota-brain axis may contribute to improving the condition of PD patients is gaining increasing relevance.

5. Parkinson’s Therapy and Gut Microbiota

In light of the previously discussed overview of the main pathogenic mechanisms underlying PD, the rationale behind the three principal therapeutic strategies currently employed in its management becomes more evident. These include oral pharmacological treatments based on L-DOPA, dopamine agonists, and monoamine oxidase type B inhibitors (MAO-BIs). Additionally, catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitors are commonly used in clinical practice in combination with L-DOPA, aiming to reduce its peripheral metabolism and thereby prolong its therapeutic efficacy.

Although all of these options are considered valid first-line strategies, L-DOPA is associated with superior therapeutic efficacy in clinical practice [66] and is therefore generally preferred over alternative treatments. This predominant use may account for the relatively greater number of studies investigating the interactions between L-DOPA —a dopamine precursor—and the gut microbiota. By contrast, as highlighted in our analysis, specific experimental evidence exploring the interactions between the gut microbiota and dopamine agonists or monoamine oxidase type B inhibitors (MAO-BIs) remains limited to date.

5.1. Levodopa

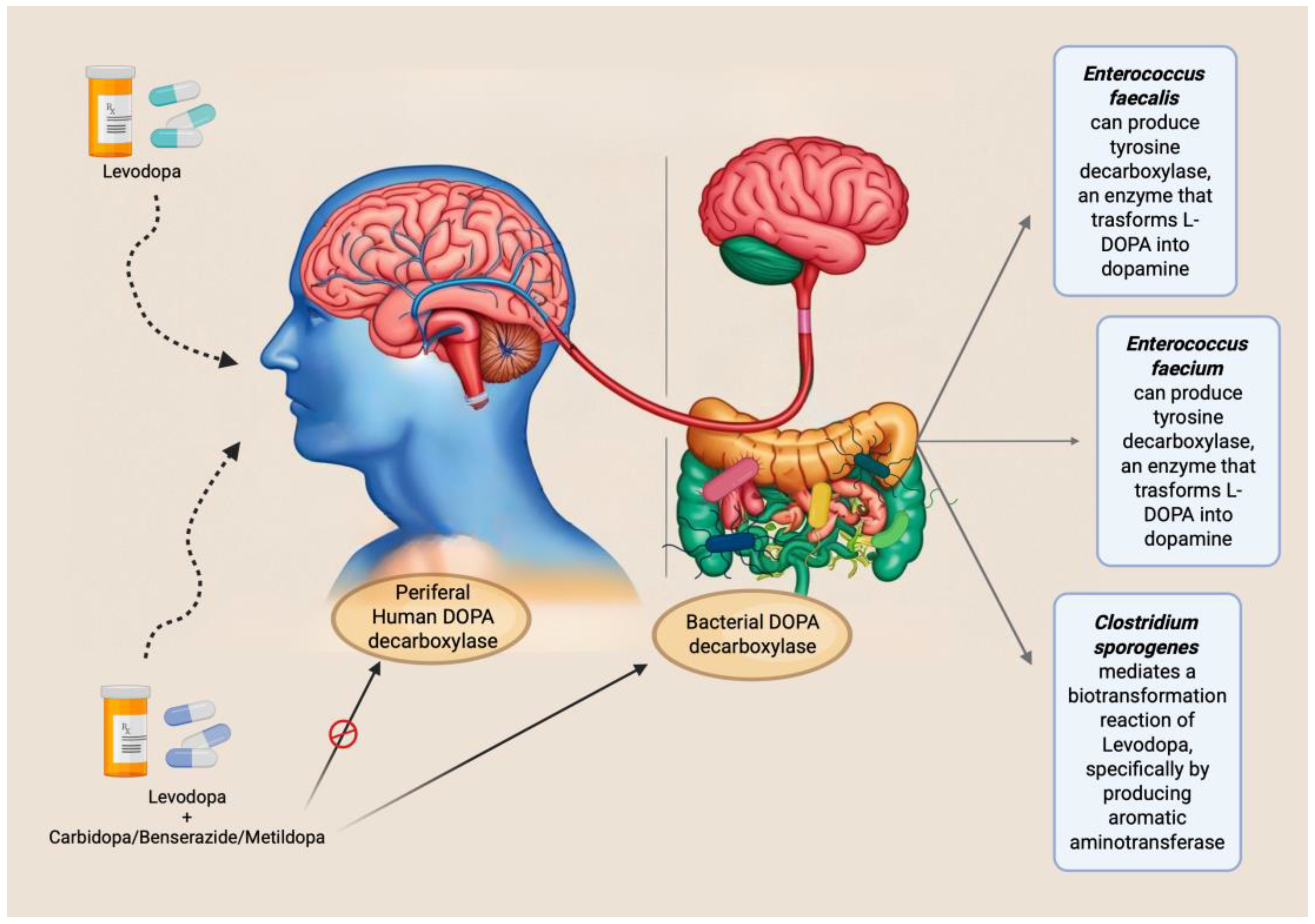

One of the most evident pathogenic alterations in PD is the progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons, which produce the neurotransmitter dopamine, in brain substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc), leading to reduced dopamine concentrations in the striatum [53]. Consequently, a rational therapeutic strategy involves the restoration of appropriate levels of dopamine. However, due to its chemical structure, dopamine is unable to cross the blood–brain barrier, necessitating the use of its precursor, L-DOPA, which remains the gold standard in PD treatment. Despite its clinical efficacy, orally administered L-DOPA presents significant limitations in terms of bioavailability. Owing to extensive first-pass metabolism in the small intestine, particularly the duodenum and proximal jejunum—its primary site of absorption—and subsequent peripheral conversion, only approximately 1–5% of the administered dose effectively reaches the CNS [67]. In addition to reduced therapeutic efficacy, peripheral metabolism of L-DOPA results in the production of metabolites that contribute to adverse effects [68], For this reason, simply increasing the dosage is not a viable strategy for overcoming its limited bioavailability.

Interestingly, these biotransformations are mediated by enzymes that, besides being expressed in enteric mucosa, may be encoded by specific bacterial species within the gut microbiota. For instance, some studies have demonstrated that Enterococcus faecalis expresses tyrosine decarboxylase (TDC), an enzyme capable of converting L-DOPA into dopamine [69,70]. Additionally, the same researchers observed similar activity in Enterococcus faecium [69]. These observations suggest that a higher abundance of gut bacteria expressing TDC in the small intestine may impair the absorption of the levodopa/carbidopa combination. This implies the existence of interindividual variability in drug efficacy, potentially attributable to differences in gut microbiota composition. Indeed, the study by Van Kessel et al. (2019) reported a positive correlation between the relative abundance of the bacterial TDC gene and both the daily L-DOPA dose and disease duration [70]. Supporting this finding, a subsequent study involving PD patients showed that moderate responders to L-DOPA exhibited a higher abundance of the TDC gene and Enterococcus faecalis compared to good responders [71]. However, these and similar studies share a significant methodological limitation: the quantification of the TDC gene was performed on fecal samples. It is well established that L-DOPA absorption primarily occurs in the proximal small intestine [72], and that gut microbiota composition varies markedly along the gastrointestinal tract. Consequently, analyses based solely on fecal samples may not accurately reflect microbial activity at the site of drug absorption, thus limiting the validity of the conclusions drawn from these studies.

Given the evidence that L-DOPA is inactivated by decarboxylase activity, current commercial formulations co-administer this dopamine precursor with inhibitors such as carbidopa, benserazide, or methyldopa. These compounds are intended to inhibit peripheral decarboxylation and enhance central availability. However, none of these inhibitors has demonstrated a sufficiently effective inhibitory action against the bacterial tyrosine decarboxylase enzyme [70].

Beyond modulating absorption profiles, the gut microbiota also plays a significant role in the interindividual variability of side effects manifestation. For example, Clostridium sporogenes has been shown to mediate a specific biotransformation of L-DOPA by producing aromatic aminotransferase. This enzyme utilizes unabsorbed intestinal L-DOPA as a substrate, leading to the formation of an inactive deaminated metabolite, which has also been implicated in the onset of gastrointestinal side effects.[73].

Identifying potential targets of microbiota-mediated alterations in L-DOPA first-pass metabolism in the small intestine may contribute to the optimization of PD therapy by enhancing L-DOPA bioavailability and, consequently, improving its therapeutic efficacy while minimizing adverse effects. At present, the broader adoption of subcutaneous L-DOPA delivery systems offers a promising strategy to circumvent intestinal metabolic interference [74,75,76]. Such approaches may exert beneficial effects not only on gastrointestinal disturbances but also on the management of motor symptoms.

The main mechanisms and interactions mentioned are summarized in

Figure 2.

5.2. Dopamine Agonists

Although current evidence on the interactions between other classes of drugs used in PD treatment and the gut microbiota remains limited, further investigation in this area is warranted. Drug–microbiota interactions may significantly influence individual responses to therapy, potentially leading to variability in clinical outcomes.

Preclinical studies in animal models have suggested that treatment with dopamine agonists may contribute to reduced intestinal motility and the development of SIBO. According to van Kessel et al. (2022), these alterations were associated with an increased abundance of bacterial genera such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, alongside a reduction in species belonging to the Lachnospiraceae and Prevotellaceae families [77].

It is worth noting that in the aforementioned study, dopamine agonists were administered in combination with L-DOPA–carbidopa. Consequently, disentangling the specific effects of each pharmacological agent on gut microbiota composition and gastrointestinal motility remains an open question and a critical area for future research.

5.3. COMT Inhibitors

As previously mentioned, COMT inhibitors represent one of the most widely used pharmacological classes in the treatment of PD. However, a major limitation of these agents is their potential to induce gastrointestinal side effects.

Over time, several studies have reported dysbiosis in patients undergoing treatment with COMT inhibitors, including an increased abundance of Enterobacteriaceae [78] and Lactobacilluslacteae [79], along with a decrease in Bifidobacteria [80] and Lachnospiraceae [79]. Collectively, these alterations reflect a microbial imbalance marked by an overrepresentation of potentially pathogenic species and a concomitant depletion of commensal bacteria with anti-inflammatory properties. This dysbiotic profile may play a key role in the onset of the gastrointestinal side effects commonly associated with COMT inhibitor therapy.

Notably, the use of entacapone has been found to be inversely associated with fecal levels of butyrate—one of the most abundant short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) produced by the gut microbiota [81]. Given the central role of SCFAs in modulating host physiological functions, including immune regulation and intestinal barrier integrity, further investigation into the implications of entacapone on SCFA metabolism is therefore of considerable interest.

6. Potential Strategies of Microbial Intervention in Parkinson's Disease

6.1. Food (Diet, Prebiotics)

Food represents a vast field of exploration in the realm of well-being, offering numerous opportunities since it is a universal aspect of everyday life. Moreover, making small dietary adjustments is relatively simple and accessible. Evidence indicates that adherence to a healthy dietary pattern in individuals with PD is associated with a reduction in circulating lipopolysaccharide (LPS) levels—pro-inflammatory endotoxins that are typically elevated in affected patients and implicated in neurodegenerative processes [82,83]. The same dietary habits can also increase the abundance of SCFA-producing species, benefiting both the intestine by strengthening the epithelial barrier and the CNS by reducing neuroinflammation [83]. To achieve these effects and support the classification of diet as a health-promoting intervention in PD, an adequate intake of dietary fiber is essential. This can be readily attained through the regular consumption of fiber-rich foods such as vegetables, fruits, legumes, and whole grains.

A strategy consistent with these findings and shown to be beneficial in alleviating symptoms of PD is the use of prebiotics. These compounds selectively promote the growth and activity of beneficial host microorganisms—for instance, through the direct administration of sodium butyrate [84]. A recent clinical study investigated the effects of a four-week high-fiber diet supplemented with the prebiotic lactulose in individuals with PD. The intervention led to a notable increase in Bifidobacteria, which was associated with a significant rise in fecal SCFA production, resulting in improvements in gastrointestinal symptoms, particularly constipation. Furthermore, the study reported an elevation in neuroprotective metabolites, including S-adenosylmethionine, suggesting additional potential benefits beyond the gastrointestinal tract [85].

However, research on prebiotics in PD treatment is progressing much more slowly than that on probiotics and remains limited, despite promising findings on prebiotic-probiotic associations (i.e. symbiotics), as we will discuss later.

Among the bioactive compounds with potential therapeutic relevance in PD through gut microbiota modulation, polyphenols are of particular interest. These molecules, characterized by strong antioxidant properties, are abundant in plant-based foods such as fruits, vegetables, tea, cocoa, extra virgin olive oil, and a variety of spices, and are well known for their neuroprotective effects.

Experimental studies have demonstrated that specific polyphenols—such as epigallocatechin gallate, the main catechin found in green tea, and curcumin—can inhibit α-synuclein aggregation and attenuate neuroinflammatory responses [86]. In addition to their direct antioxidant and anti-inflammatory actions, polyphenols also influence the gut microbiota by modulating its composition and metabolic activity. Notably, regular dietary intake of flavonoids has been associated with an increased production of SCFAs by intestinal microbes, further supporting their role in maintaining gut and brain health. [87].

Dietary supplements also fall within this category. In particular, supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids (omega-3s) has been shown to exert beneficial effects on the CNS by supporting blood–brain barrier integrity, slowing the progression of neurodegeneration, and inhibiting neuroinflammatory processes. Moreover, omega-3s are believed to protect dopaminergic neurotransmission through mechanisms involving the inhibition of NF-κB signaling pathways [88,89]. The gut microbiota may also contribute to these effects by adopting a more anti-inflammatory profile in response to omega-3 supplementation; however, this hypothesis requires further validation through targeted research efforts [90]. A critical analysis of the current literature reveals a scientific gap between the extensive body of preclinical and observational studies and the limited availability of evidence-based dietary guidelines specifically aimed at modulating the development or progression of PD. Interventional studies in this area remain in the early stages and are still insufficient to support formal clinical recommendations.

6.2. Probiotics

Probiotics are defined by the World Health Organization as "the moderate intake of live microorganisms with beneficial effects on the host’s health" [91].

As soon as the scientific community began focusing on the benefits of microbiota modulation through probiotics in PD therapy, promising results quickly emerged regarding the gastrointestinal symptoms of the disease, particularly constipation one of the most frequently occurring signs. The beneficial effects of probiotics are thought to arise from the introduction of specific bacterial strains or modulation of microbial abundance, which in turn leads to the production of metabolites capable of reinforcing the integrity of the intestinal mucosa [92] and inhibiting harmful bacteria [93]. Further evidence supporting the existence and functional relevance of the microbiota–gut–brain axis in PD comes from studies demonstrating that probiotics can exert effects not only at the gastrointestinal level but also within the CNS. In particular, certain probiotic strains have been shown to modulate neurotransmitter activity and exert neuroprotective effects on dopaminergic neurons [94]. Notably, a 2023 meta-analysis reported significant improvements in scores on the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) Part III, indicating that probiotic supplementation may also contribute to attenuating motor symptom severity and, more broadly, influence disease progression [95].

In order to explore the wide range of potential probiotic-based therapies for patients with PD, it is essential to introduce a distinction between the use of single-strain probiotics and multi-strain probiotic formulations. Several preclinical studies have reported promising outcomes with single-strain probiotic interventions. In 2022, Lactobacillus plantarum DP189 was administered for two weeks in an MPTP-induced murine model of PD. This intervention resulted in a significant reduction in neuroinflammation and a decrease in the accumulation of α-synuclein in the brain [96]. The same animal model was used to investigate the effects of Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus E9. Oral administration of this strain produced beneficial outcomes at both the central and intestinal sites, including increased cerebral dopamine levels, attenuation of intestinal barrier damage, and restoration of microbial balance [97].

The efficacy of Bifidobacterium breve has been demonstrated in two different strains tested in PD animal models. The first, strain CCFM1067, exerted neuroprotective effects by suppressing glial activation, while also modulating the gut microbiota by reducing the abundance of pathogenic bacteria such as Escherichia and promoting beneficial genera such as Akkermansia, leading to an increase in SCFAs with anti-inflammatory properties [98]. Similarly, the B. breve Bif11 strain was shown to improve motor function and intestinal permeability [99]. In a clinical context, a study involving 82 patients with PD evaluated the effects of the single-strain probiotic B. lactis Probio-M8 administered for 12 weeks in combination with standard therapy. The results indicated an improvement in both motor and non-motor symptoms (such as sleep quality and bowel regularity), alongside favorable modifications in gut microbiota composition [100].

When considering the administration of multi-strain formulations, a noteworthy clinical study investigated the oral supplementation of a capsule containing L. acidophilus, L. fermentum, L. reuteri, and B. bifidum over a three-month period. This intervention led to a reduction in the total score of the UPDRS, indicating a clinical improvement in patients. Moreover, a decrease in systemic inflammatory markers such as high-sensitivity C-reactive protein was observed [101].

Despite these promising findings, certain limitations of probiotic use must be considered. Most probiotic products available on the market fail to reach their target site the intestine because they are inactivated by stomach acid. To overcome this physical barrier, a more advanced product, Symprove K-1803, has been developed. This orally administered probiotic can deliver live bacteria to the intestinal tract [102]. While probiotics appear to be effective in reducing both motor and non-motor symptoms, further studies are necessary to determine the most appropriate therapeutic interventions and evaluate their long-term effects.

6.3. Synbiotics

The combination of prebiotics and probiotics in a single formulation is referred to as a synbiotic. This dual approach appears to be more effective in supporting gut microbiota balance than the use of either component alone [103]. Current research primarily focuses on evaluating whether synbiotics administration can improve gastrointestinal symptoms associated with CNS disorders, including PD [104,105]. In a murine model of PD, an experimental synbiotic composed of polymannuronate (PM) and Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG demonstrated promising results following a five-week treatment regimen. The intervention preserved dopaminergic neurons and improved motor function, as evidenced by behavioral test outcomes. Notably, the synbiotic exerted greater neuroprotective effects than either component administered individually [106].

The positive outcomes of these studies encourage further exploration of the use of these therapies in such populations.

6.4. Antibiotics

The overarching goal of gut microbiota modulation is to restore a healthy balance between beneficial and potentially harmful bacterial species. Within this framework, an alternative strategy to those previously discussed involves targeting and reducing specific pathogenic taxa.

As noted earlier, PD patients tend to exhibit excessive bacterial proliferation, particularly in the small intestine known as SIBO [107]. Broad-spectrum antibiotics such as rifaximin and tetracyclines have demonstrated efficacy in eradicating SIBO [108,109]. Importantly, SIBO may affect the metabolism of L-DOPA by promoting the overgrowth of gut bacteria expressing the TDC gene, which reduces L-DOPA bioavailability [110]. This raises the hypothesis that eliminating SIBO may enhance L-DOPA absorption and, in turn, improve motor symptoms. However, a clinical study investigating rifaximin for SIBO treatment did not report significant changes in L-DOPA pharmacokinetics [65].

Beyond their antimicrobial activity, certain antibiotics have also shown neuroprotective properties. In a preclinical study, Zhou and colleagues (2021) demonstrated that ceftriaxone exerted anti-inflammatory effects in a murine model of PD, highlighting its potential CNS benefits [111]. Clinically, a combination therapy involving a sodium phosphate enema followed by oral rifaximin and polyethylene glycol was associated with reduced motor fluctuations and a significant improvement in dyskinesia severity and duration in PD patients [112]. An interesting strategy, currently under evaluation (Trial ID: 2024-510629-24-00) is to reduce the gut bacteria that decarboxylate L-DOPA by administering antibiotics, such as rifaximin, for potentially increasing the bioavailability and effectiveness of L-DOPA in PD patients. While these findings are promising, it remains unclear whether the observed benefits stem from microbiota modulation or other mechanisms of action.

Should future studies confirm these effects, careful evaluation of the risk–benefit profile of long-term antibiotic use in this patient population will be essential before considering their implementation as a viable therapeutic strategy.

7. Potential Developments

Even though studies are still in their early stages, the microbiota is already identified as a potential disease biomarker [10].

The presence of analytical microbiota markers that yield objective results would significantly enhance clinical diagnosis even in the prodromal phase of PD which is often characterized by symptoms such as constipation and nausea symptoms which suggest early involvement of the gastrointestinal tract [113]. Early intervention is crucial for ensuring effective, long-lasting treatments, without waiting for the emergence of motor symptoms, which indicate advanced disease stages.

Should these hypotheses be validated, the microbiota could emerge as a therapeutic target (e.g., through the use of probiotics, prebiotics, or fecal transplantation) for symptomatic treatment, disease progression modulation, or adjunctive therapies aimed at mitigating the side effects of CNS-targeted drugs [60].

As reviewed herein, various therapeutic strategies based on microbiota modulation have demonstrated promising potential in PD. However, to establish their efficacy with greater confidence, further clinical studies involving patient cohorts and analysis of small intestine microbiota-mediated influence are necessary. It is also clear that, following an initial phase of exploratory research, there is an urgent need to transition from observational to experimental studies. This shift is essential for drawing more robust conclusions and more precisely defining the impact of these interventions. Ultimately, enhancing our understanding of the microbiome — specifically, the genetic information encoded within the microbiota of small intestine — holds significant promise for advancing our knowledge of PD, where genetic factors play a central role in both predisposition and disease progression.

We anticipate that this represents the beginning of a broader journey. As scientific evidence continues to accumulate, it is conceivable that the research community will recognize a fundamental shift in perspectives regarding neurodegenerative diseases. The gut-brain axis is not merely an intriguing area of investigation; it is a pivotal element, especially in PD. Here, gastrointestinal alterations are not secondary manifestations but integral components of the pathological process, with profound implications for both disease progression and clinical management.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fulop, T.; Larbi, A.; Pawelec, G.; Khalil, A.; Cohen, A.A.; Hirokawa, K.; Witkowski, J.M.; Franceschi, C. Immunology of Aging: The Birth of Inflammaging. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2023, 64, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschi, C.; Bonafè, M.; Valensin, S.; Olivieri, F.; De Luca, M.; Ottaviani, E.; De Benedictis, G. Inflamm-Aging. An Evolutionary Perspective on Immunosenescence. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2000, 908, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulop, T.; Witkowski, J.M.; Olivieri, F.; Larbi, A. The Integration of Inflammaging in Age-Related Diseases. Semin. Immunol. 2018, 40, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresci, G.A.; Bawden, E. Gut Microbiome: What We Do and Don’t Know. Nutr. Clin. Pract. Off. Publ. Am. Soc. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2015, 30, 734–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodogai, M.; O’Connell, J.; Kim, K.; Kim, Y.; Moritoh, K.; Chen, C.; Gusev, F.; Vaughan, K.; Shulzhenko, N.; Mattison, J.A.; et al. Commensal Bacteria Contribute to Insulin Resistance in Aging by Activating Innate B1a Cells. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018, 10, eaat4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepici, G.; Silvestro, S.; Bramanti, P.; Mazzon, E. The Gut Microbiota in Multiple Sclerosis: An Overview of Clinical Trials. Cell Transplant. 2019, 28, 1507–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naomi, R.; Embong, H.; Othman, F.; Ghazi, H.F.; Maruthey, N.; Bahari, H. Probiotics for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2021, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Gao, G.; Kwok, L.-Y.; Sun, Z. Gut Microbiome-Targeted Therapies for Alzheimer’s Disease. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2271613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsey, E.R.; Sherer, T.; Okun, M.S.; Bloem, B.R. The Emerging Evidence of the Parkinson Pandemic. J. Park. Dis. 2018, 8, S3–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolosa, E.; Garrido, A.; Scholz, S.W.; Poewe, W. Challenges in the Diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sender, R.; Fuchs, S.; Milo, R. Are We Really Vastly Outnumbered? Revisiting the Ratio of Bacterial to Host Cells in Humans. Cell 2016, 164, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, M.J.; Plummer, N.T. Part 1: The Human Gut Microbiome in Health and Disease. Integr. Med. Encinitas Calif 2014, 13, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan, F.; Ghosh, T.S.; O’Toole, P.W. The Healthy Microbiome-What Is the Definition of a Healthy Gut Microbiome? Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursell, L.K.; Metcalf, J.L.; Parfrey, L.W.; Knight, R. Defining the Human Microbiome. Nutr. Rev. 2012, 70 Suppl 1, S38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Ley, R.E.; Hamady, M.; Fraser-Liggett, C.M.; Knight, R.; Gordon, J.I. The Human Microbiome Project. Nature 2007, 449, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vascellari, S.; Palmas, V.; Melis, M.; Pisanu, S.; Cusano, R.; Uva, P.; Perra, D.; Madau, V.; Sarchioto, M.; Oppo, V.; et al. Gut Microbiota and Metabolome Alterations Associated with Parkinson’s Disease. mSystems 2020, 5, e00561–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.H.; Chong, C.W.; Lim, S.-Y.; Yap, I.K.S.; Teh, C.S.J.; Loke, M.F.; Song, S.-L.; Tan, J.Y.; Ang, B.H.; Tan, Y.Q.; et al. Gut Microbial Ecosystem in Parkinson Disease: New Clinicobiological Insights from Multi-Omics. Ann. Neurol. 2021, 89, 546–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedberg, D.E.; Toussaint, N.C.; Chen, S.P.; Ratner, A.J.; Whittier, S.; Wang, T.C.; Wang, H.H.; Abrams, J.A. Proton Pump Inhibitors Alter Specific Taxa in the Human Gastrointestinal Microbiome: A Crossover Trial. Gastroenterology 2015, 149, 883–885.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, L.; Pruteanu, M.; Kuhn, M.; Zeller, G.; Telzerow, A.; Anderson, E.E.; Brochado, A.R.; Fernandez, K.C.; Dose, H.; Mori, H.; et al. Extensive Impact of Non-Antibiotic Drugs on Human Gut Bacteria. Nature 2018, 555, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, R.; Rizkallah, M.R.; Aziz, R.K. Gut Pharmacomicrobiomics: The Tip of an Iceberg of Complex Interactions between Drugs and Gut-Associated Microbes. Gut Pathog. 2012, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Buschmann, M.M.; Gilbert, J.A. Pharmacomicrobiomics: The Holy Grail to Variability in Drug Response? Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 106, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javdan, B.; Lopez, J.G.; Chankhamjon, P.; Lee, Y.-C.J.; Hull, R.; Wu, Q.; Wang, X.; Chatterjee, S.; Donia, M.S. Personalized Mapping of Drug Metabolism by the Human Gut Microbiome. Cell 2020, 181, 1661–1679.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weersma, R.K.; Zhernakova, A.; Fu, J. Interaction between Drugs and the Gut Microbiome. Gut 2020, 69, 1510–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppel, N.; Maini Rekdal, V.; Balskus, E.P. Chemical Transformation of Xenobiotics by the Human Gut Microbiota. Science 2017, 356, eaag2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaser, M.J. Antibiotic Use and Its Consequences for the Normal Microbiome. Science 2016, 352, 544–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ianiro, G.; Tilg, H.; Gasbarrini, A. Antibiotics as Deep Modulators of Gut Microbiota: Between Good and Evil. Gut 2016, 65, 1906–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgun, A.; Dzutsev, A.; Dong, X.; Greer, R.L.; Sexton, D.J.; Ravel, J.; Schuster, M.; Hsiao, W.; Matzinger, P.; Shulzhenko, N. Uncovering Effects of Antibiotics on the Host and Microbiota Using Transkingdom Gene Networks. Gut 2015, 64, 1732–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonder, M.J.; Tigchelaar, E.F.; Cai, X.; Trynka, G.; Cenit, M.C.; Hrdlickova, B.; Zhong, H.; Vatanen, T.; Gevers, D.; Wijmenga, C.; et al. The Influence of a Short-Term Gluten-Free Diet on the Human Gut Microbiome. Genome Med. 2016, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.A.; Verdi, S.; Maxan, M.-E.; Shin, C.M.; Zierer, J.; Bowyer, R.C.E.; Martin, T.; Williams, F.M.K.; Menni, C.; Bell, J.T.; et al. Gut Microbiota Associations with Common Diseases and Prescription Medications in a Population-Based Cohort. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vich Vila, A.; Collij, V.; Sanna, S.; Sinha, T.; Imhann, F.; Bourgonje, A.R.; Mujagic, Z.; Jonkers, D.M.A.E.; Masclee, A.A.M.; Fu, J.; et al. Impact of Commonly Used Drugs on the Composition and Metabolic Function of the Gut Microbiota. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, F.C.; Patangia, D.; Grimaud, G.; Lavelle, A.; Dempsey, E.M.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C. The Interplay between Diet and the Gut Microbiome: Implications for Health and Disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 671–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozupone, C.A.; Stombaugh, J.I.; Gordon, J.I.; Jansson, J.K.; Knight, R. Diversity, Stability and Resilience of the Human Gut Microbiota. Nature 2012, 489, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, J.E.; Spor, A.; Scalfone, N.; Fricker, A.D.; Stombaugh, J.; Knight, R.; Angenent, L.T.; Ley, R.E. Succession of Microbial Consortia in the Developing Infant Gut Microbiome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108 Suppl 1, 4578–4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdes, A.M.; Walter, J.; Segal, E.; Spector, T.D. Role of the Gut Microbiota in Nutrition and Health. BMJ 2018, 361, k2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, M.K.; Boudry, G.; Lemay, D.G.; Raybould, H.E. Changes in Intestinal Barrier Function and Gut Microbiota in High-Fat Diet-Fed Rats Are Dynamic and Region Dependent. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2015, 308, G840–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsou, E.K.; Kakali, A.; Antonopoulou, S.; Mountzouris, K.C.; Yannakoulia, M.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Kyriacou, A. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Is Associated with the Gut Microbiota Pattern and Gastrointestinal Characteristics in an Adult Population. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 117, 1645–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linehan, K.; Dempsey, E.M.; Ryan, C.A.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C. First Encounters of the Microbial Kind: Perinatal Factors Direct Infant Gut Microbiome Establishment. Microbiome Res. Rep. 2022, 1, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatanen, T.; Jabbar, K.S.; Ruohtula, T.; Honkanen, J.; Avila-Pacheco, J.; Siljander, H.; Stražar, M.; Oikarinen, S.; Hyöty, H.; Ilonen, J.; et al. Mobile Genetic Elements from the Maternal Microbiome Shape Infant Gut Microbial Assembly and Metabolism. Cell 2022, 185, 4921–4936.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, C.L.J.; Onnerfält, J.; Xu, J.; Molin, G.; Ahrné, S.; Thorngren-Jerneck, K. The Microbiota of the Gut in Preschool Children with Normal and Excessive Body Weight. Obes. Silver Spring Md 2012, 20, 2257–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aversa, F.; Tortora, A.; Ianiro, G.; Ponziani, F.R.; Annicchiarico, B.E.; Gasbarrini, A. Gut Microbiota and Metabolic Syndrome. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2013, 8 Suppl 1, S11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanislawski, M.A.; Dabelea, D.; Lange, L.A.; Wagner, B.D.; Lozupone, C.A. Gut Microbiota Phenotypes of Obesity. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2019, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaumont, W. Nutrition Classics. Experiments and Observations on the Gastric Juice and the Physiology of Digestion. By William Beaumont. Plattsburgh. Printed by F. P. Allen. 1833. Nutr. Rev. 1977, 35, 144–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almy, T.P. Experimental Studies on the Irritable Colon. Am. J. Med. 1951, 10, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drossman, D.A. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: History, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology, 0016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mönnikes, H.; Tebbe, J.J.; Hildebrandt, M.; Arck, P.; Osmanoglou, E.; Rose, M.; Klapp, B.; Wiedenmann, B.; Heymann-Mönnikes, I. Role of Stress in Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Evidence for Stress-Induced Alterations in Gastrointestinal Motility and Sensitivity. Dig. Dis. Basel Switz. 2001, 19, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kano, M.; Dupont, P.; Aziz, Q.; Fukudo, S. Understanding Neurogastroenterology From Neuroimaging Perspective: A Comprehensive Review of Functional and Structural Brain Imaging in Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2018, 24, 512–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Lee, J.Y.; Jung, S.W.; Shin, S.Y.; Ryu, H.S.; Jang, S.-H.; Kwon, J.G.; Kim, Y.S. [Brain-Gut-Microbiota Axis]. Korean J. Gastroenterol. Taehan Sohwagi Hakhoe Chi 2023, 81, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drossman, D.A.; Tack, J.; Ford, A.C.; Szigethy, E.; Törnblom, H.; Van Oudenhove, L. Neuromodulators for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction): A Rome Foundation Working Team Report. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 1140–1171.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Chen, H.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, F.; Ruan, G.; Ying, S.; Tang, W.; Chen, L.; Chen, M.; Lv, L.; et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Relieves Gastrointestinal and Autism Symptoms by Improving the Gut Microbiota in an Open-Label Study. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 759435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartsough, L.A.; Park, M.; Kotlajich, M.V.; Lazar, J.T.; Han, B.; Lin, C.-C.J.; Musteata, E.; Gambill, L.; Wang, M.C.; Tabor, J.J. Optogenetic Control of Gut Bacterial Metabolism to Promote Longevity. eLife 2020, 9, e56849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opara, J.; Małecki, A.; Małecka, E.; Socha, T. Motor Assessment in Parkinson`s Disease. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. AAEM 2017, 24, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, M.T. Parkinson’s Disease and Parkinsonism. Am. J. Med. 2019, 132, 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibb, W.R.; Lees, A.J. The Relevance of the Lewy Body to the Pathogenesis of Idiopathic Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1988, 51, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stocchi, F.; Bravi, D.; Emmi, A.; Antonini, A. Parkinson Disease Therapy: Current Strategies and Future Research Priorities. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2024, 20, 695–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cloud, L.J.; Greene, J.G. Gastrointestinal Features of Parkinson’s Disease. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2011, 11, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Han, D.; Cheng, Q.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, C.; Min, J.; Wang, F. Association of Levels of Physical Activity With Risk of Parkinson Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e182421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz Heijtz, R.; Wang, S.; Anuar, F.; Qian, Y.; Björkholm, B.; Samuelsson, A.; Hibberd, M.L.; Forssberg, H.; Pettersson, S. Normal Gut Microbiota Modulates Brain Development and Behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108, 3047–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caradonna, E.; Nemni, R.; Bifone, A.; Gandolfo, P.; Costantino, L.; Giordano, L.; Mormone, E.; Macula, A.; Cuomo, M.; Difruscolo, R.; et al. The Brain-Gut Axis, an Important Player in Alzheimer and Parkinson Disease: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braak, H.; Rüb, U.; Gai, W.P.; Del Tredici, K. Idiopathic Parkinson’s Disease: Possible Routes by Which Vulnerable Neuronal Types May Be Subject to Neuroinvasion by an Unknown Pathogen. J. Neural Transm. Vienna Austria 1996 2003, 110, 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socała, K.; Doboszewska, U.; Szopa, A.; Serefko, A.; Włodarczyk, M.; Zielińska, A.; Poleszak, E.; Fichna, J.; Wlaź, P. The Role of Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Neuropsychiatric and Neurological Disorders. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 172, 105840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, W.; Qiao, C.-M.; Niu, G.-Y.; Wu, J.; Zhao, L.-P.; Cui, C.; Zhao, W.-J.; Shen, Y.-Q. Trimethylamine N-Oxide Exacerbates Neuroinflammation and Motor Dysfunction in an Acute MPTP Mice Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xie, F.; Deng, C.; Zheng, W.; Zhu, S.; Wang, Q. Causal Effect of Gut-Microbiota-Derived Metabolite Trimethylamine N-Oxide on Parkinson’s Disease: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Eur. J. Neurol. 2023, 30, 3451–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, M.; Dai, L.; Avesani, C.M.; Kublickiene, K.; Stenvinkel, P. The Dietary Source of Trimethylamine N-Oxide and Clinical Outcomes: An Unexpected Liaison. Clin. Kidney J. 2023, 16, 1804–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkes, C.H.; Del Tredici, K.; Braak, H. Parkinson’s Disease: A Dual-Hit Hypothesis. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2007, 33, 599–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasano, A.; Bove, F.; Gabrielli, M.; Petracca, M.; Zocco, M.A.; Ragazzoni, E.; Barbaro, F.; Piano, C.; Fortuna, S.; Tortora, A.; et al. The Role of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2013, 28, 1241–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foltynie, T.; Bruno, V.; Fox, S.; Kühn, A.A.; Lindop, F.; Lees, A.J. Medical, Surgical, and Physical Treatments for Parkinson’s Disease. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2024, 403, 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J.P.; Bianchine, J.R.; Spiegel, H.E.; Rivera-Calimlim, L.; Hersey, R.M. Metabolism of Levodopa in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Radioactive and Fluorometric Assays. Arch. Neurol. 1971, 25, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyholm, D.; Lennernäs, H. Irregular Gastrointestinal Drug Absorption in Parkinson’s Disease. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2008, 4, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maini Rekdal, V.; Bess, E.N.; Bisanz, J.E.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Balskus, E.P. Discovery and Inhibition of an Interspecies Gut Bacterial Pathway for Levodopa Metabolism. Science 2019, 364, eaau6323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kessel, S.P.; Frye, A.K.; El-Gendy, A.O.; Castejon, M.; Keshavarzian, A.; van Dijk, G.; El Aidy, S. Gut Bacterial Tyrosine Decarboxylases Restrict Levels of Levodopa in the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, X.; Mo, C.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Yan, Z.; Qian, Y.; Lai, Y.; Xu, S.; Yang, X.; et al. Association Between Microbial Tyrosine Decarboxylase Gene and Levodopa Responsiveness in Patients With Parkinson Disease. Neurology 2022, 99, e2443–e2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, S.M.R.; Vuille-dit-Bille, R.N.; Mariotta, L.; Ramadan, T.; Huggel, K.; Singer, D.; Götze, O.; Verrey, F. The Molecular Mechanism of Intestinal Levodopa Absorption and Its Possible Implications for the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2014, 351, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Kessel, S.P.; de Jong, H.R.; Winkel, S.L.; van Leeuwen, S.S.; Nelemans, S.A.; Permentier, H.; Keshavarzian, A.; El Aidy, S. Gut Bacterial Deamination of Residual Levodopa Medication for Parkinson’s Disease. BMC Biol. 2020, 18, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosebraugh, M.; Voight, E.A.; Moussa, E.M.; Jameel, F.; Lou, X.; Zhang, G.G.Z.; Mayer, P.T.; Stolarik, D.; Carr, R.A.; Enright, B.P.; et al. Foslevodopa/Foscarbidopa: A New Subcutaneous Treatment for Parkinson’s Disease. Ann. Neurol. 2021, 90, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lees, A.; Tolosa, E.; Stocchi, F.; Ferreira, J.J.; Rascol, O.; Antonini, A.; Poewe, W. Optimizing Levodopa Therapy, When and How? Perspectives on the Importance of Delivery and the Potential for an Early Combination Approach. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2023, 23, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeWitt, P.A.; Hauser, R.A.; Pahwa, R.; Isaacson, S.H.; Fernandez, H.H.; Lew, M.; Saint-Hilaire, M.; Pourcher, E.; Lopez-Manzanares, L.; Waters, C.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of CVT-301 (Levodopa Inhalation Powder) on Motor Function during off Periods in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kessel, S.P.; Bullock, A.; van Dijk, G.; El Aidy, S. Parkinson’s Disease Medication Alters Small Intestinal Motility and Microbiota Composition in Healthy Rats. mSystems 2022, 7, e0119121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheperjans, F.; Aho, V.; Pereira, P.A.B.; Koskinen, K.; Paulin, L.; Pekkonen, E.; Haapaniemi, E.; Kaakkola, S.; Eerola-Rautio, J.; Pohja, M.; et al. Gut Microbiota Are Related to Parkinson’s Disease and Clinical Phenotype. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2015, 30, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barichella, M.; Severgnini, M.; Cilia, R.; Cassani, E.; Bolliri, C.; Caronni, S.; Ferri, V.; Cancello, R.; Ceccarani, C.; Faierman, S.; et al. Unraveling Gut Microbiota in Parkinson’s Disease and Atypical Parkinsonism. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2019, 34, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill-Burns, E.M.; Debelius, J.W.; Morton, J.T.; Wissemann, W.T.; Lewis, M.R.; Wallen, Z.D.; Peddada, S.D.; Factor, S.A.; Molho, E.; Zabetian, C.P.; et al. Parkinson’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease Medications Have Distinct Signatures of the Gut Microbiome. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2017, 32, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grün, D.; Zimmer, V.C.; Kauffmann, J.; Spiegel, J.; Dillmann, U.; Schwiertz, A.; Faßbender, K.; Fousse, M.; Unger, M.M. Impact of Oral COMT-Inhibitors on Gut Microbiota and Short Chain Fatty Acids in Parkinson’s Disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2020, 70, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrucci, D.; Cerroni, R.; Unida, V.; Farcomeni, A.; Pierantozzi, M.; Mercuri, N.B.; Biocca, S.; Stefani, A.; Desideri, A. Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota in a Selected Population of Parkinson’s Patients. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2019, 65, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, D.; Zhang, K.; Paul, K.C.; Folle, A.D.; Del Rosario, I.; Jacobs, J.P.; Keener, A.M.; Bronstein, J.M.; Ritz, B. Diet and the Gut Microbiome in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. NPJ Park. Dis. 2024, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantu-Jungles, T.M.; Rasmussen, H.E.; Hamaker, B.R. Potential of Prebiotic Butyrogenic Fibers in Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedarf, J.R.; Romano, S.; Heinzmann, S.S.; Duncan, A.; Traka, M.H.; Ng, D.; Segovia-Lizano, D.; Simon, M.-C.; Narbad, A.; Wüllner, U.; et al. A Prebiotic Diet Intervention Can Restore Faecal Short Chain Fatty Acids in Parkinson’s Disease yet Fails to Restore the Gut Microbiome Homeostasis 2024, 2024. 09.09.2431 3184.

- Riegelman, E.; Xue, K.S.; Wang, J.-S.; Tang, L. Gut–Brain Axis in Focus: Polyphenols, Microbiota, and Their Influence on α-Synuclein in Parkinson’s Disease. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A.; Forsyth, C.B.; Shaikh, M.; Voigt, R.M.; Engen, P.A.; Ramirez, V.; Keshavarzian, A. Diet in Parkinson’s Disease: Critical Role for the Microbiome. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avallone, R.; Vitale, G.; Bertolotti, M. Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Neurodegenerative Diseases: New Evidence in Clinical Trials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernando, S.; Requejo, C.; Herran, E.; Ruiz-Ortega, J.A.; Morera-Herreras, T.; Lafuente, J.V.; Ugedo, L.; Gainza, E.; Pedraz, J.L.; Igartua, M.; et al. Beneficial Effects of N-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Administration in a Partial Lesion Model of Parkinson’s Disease: The Role of Glia and NRf2 Regulation. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 121, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Pardo, P.; Dodiya, H.B.; Broersen, L.M.; Douna, H.; van Wijk, N.; Lopes da Silva, S.; Garssen, J.; Keshavarzian, A.; Kraneveld, A.D. Gut–Brain and Brain–Gut Axis in Parkinson’s Disease Models: Effects of a Uridine and Fish Oil Diet. Nutr. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. Expert Consensus Document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics Consensus Statement on the Scope and Appropriate Use of the Term Probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Dong, W.; Chang, K.; Yan, Y.; Liu, X. Efficacy of Probiotic Supplements on Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Complement. Ther. Med. 2024, 82, 103045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X. Microbial Treatment: The Potential Application for Parkinson’s Disease. Neurol. Sci. Off. J. Ital. Neurol. Soc. Ital. Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2019, 40, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgescu, D.; Ancusa, O.E.; Georgescu, L.A.; Ionita, I.; Reisz, D. Nonmotor Gastrointestinal Disorders in Older Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: Is There Hope? Clin. Interv. Aging 2016, 11, 1601–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.M.; Lee, S.C.; Ham, C.; Kim, Y.W. Effect of Probiotic Supplementation on Gastrointestinal Motility, Inflammation, Motor, Non-Motor Symptoms and Mental Health in Parkinson’s Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Gut Pathog. 2023, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, G.; Wang, C.; Gao, L.; Niu, C.; Li, S. Lactobacillus Plantarum DP189 Reduces α-SYN Aggravation in MPTP-Induced Parkinson’s Disease Mice via Regulating Oxidative Damage, Inflammation, and Gut Microbiota Disorder. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 1163–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktas, B.; Aslim, B.; Ozdemir, D.A. A Neurotherapeutic Approach with Lacticaseibacillus Rhamnosus E9 on Gut Microbiota and Intestinal Barrier in MPTP-Induced Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Chu, C.; Yu, L.; Zhai, Q.; Wang, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Tian, F. Neuroprotective Effects of Bifidobacterium Breve CCFM1067 in MPTP-Induced Mouse Models of Parkinson’s Disease. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valvaikar, S.; Vaidya, B.; Sharma, S.; Bishnoi, M.; Kondepudi, K.K.; Sharma, S.S. Supplementation of Probiotic Bifidobacterium Breve Bif11 Reverses Neurobehavioural Deficits, Inflammatory Changes and Oxidative Stress in Parkinson’s Disease Model. Neurochem. Int. 2024, 174, 105691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhao, F.; Liu, Y.; Ma, T.; Jin, H.; Quan, K.; Leng, B.; Zhao, J.; Yuan, X.; Li, Z.; et al. Probiotics Synergized with Conventional Regimen in Managing Parkinson’s Disease. NPJ Park. Dis. 2022, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamtaji, O.R.; Taghizadeh, M.; Daneshvar Kakhaki, R.; Kouchaki, E.; Bahmani, F.; Borzabadi, S.; Oryan, S.; Mafi, A.; Asemi, Z. Clinical and Metabolic Response to Probiotic Administration in People with Parkinson’s Disease: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Clin. Nutr. Edinb. Scotl. 2019, 38, 1031–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazerani, P. Probiotics for Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barathikannan, K.; Chelliah, R.; Rubab, M.; Daliri, E.B.-M.; Elahi, F.; Kim, D.-H.; Agastian, P.; Oh, S.-Y.; Oh, D.H. Gut Microbiome Modulation Based on Probiotic Application for Anti-Obesity: A Review on Efficacy and Validation. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barichella, M.; Pacchetti, C.; Bolliri, C.; Cassani, E.; Iorio, L.; Pusani, C.; Pinelli, G.; Privitera, G.; Cesari, I.; Faierman, S.A.; et al. Probiotics and Prebiotic Fiber for Constipation Associated with Parkinson Disease: An RCT. Neurology 2016, 87, 1274–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanctuary, M.R.; Kain, J.N.; Chen, S.Y.; Kalanetra, K.; Lemay, D.G.; Rose, D.R.; Yang, H.T.; Tancredi, D.J.; German, J.B.; Slupsky, C.M.; et al. Pilot Study of Probiotic/Colostrum Supplementation on Gut Function in Children with Autism and Gastrointestinal Symptoms. PloS One 2019, 14, e0210064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Du, Z.R.; Wang, X.; Sun, X.R.; Zhao, Q.; Zhao, F.; Wong, W.T.; Wong, K.H.; Dong, X.-L. Polymannuronic Acid Prebiotic plus Lacticaseibacillus Rhamnosus GG Probiotic as a Novel Synbiotic Promoted Their Separate Neuroprotection against Parkinson’s Disease. Food Res. Int. Ott. Ont 2022, 155, 111067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielli, M.; Bonazzi, P.; Scarpellini, E.; Bendia, E.; Lauritano, E.C.; Fasano, A.; Ceravolo, M.G.; Capecci, M.; Rita Bentivoglio, A.; Provinciali, L.; et al. Prevalence of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2011, 26, 889–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, M.; Malservisi, S.; Veneto, G.; Ferrieri, A.; Corazza, G.R. Rifaximin versus Chlortetracycline in the Short-Term Treatment of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000, 14, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimentel, M. Review of Rifaximin as Treatment for SIBO and IBS. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2009, 18, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kessel, S.P.; El Aidy, S. Contributions of Gut Bacteria and Diet to Drug Pharmacokinetics in the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Lu, J.; Wei, K.; Wei, J.; Tian, P.; Yue, M.; Wang, Y.; Hong, D.; Li, F.; Wang, B.; et al. Neuroprotective Effect of Ceftriaxone on MPTP-Induced Parkinson’s Disease Mouse Model by Regulating Inflammation and Intestinal Microbiota. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 9424582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baizabal-Carvallo, J.F.; Alonso-Juarez, M.; Fekete, R. Intestinal Decontamination Therapy for Dyskinesia and Motor Fluctuations in Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 729961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, G.W.; Abbott, R.D.; Petrovitch, H.; Tanner, C.M.; White, L.R. Pre-Motor Features of Parkinson’s Disease: The Honolulu-Asia Aging Study Experience. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2012, 18 Suppl 1, S199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).