Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

11 June 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

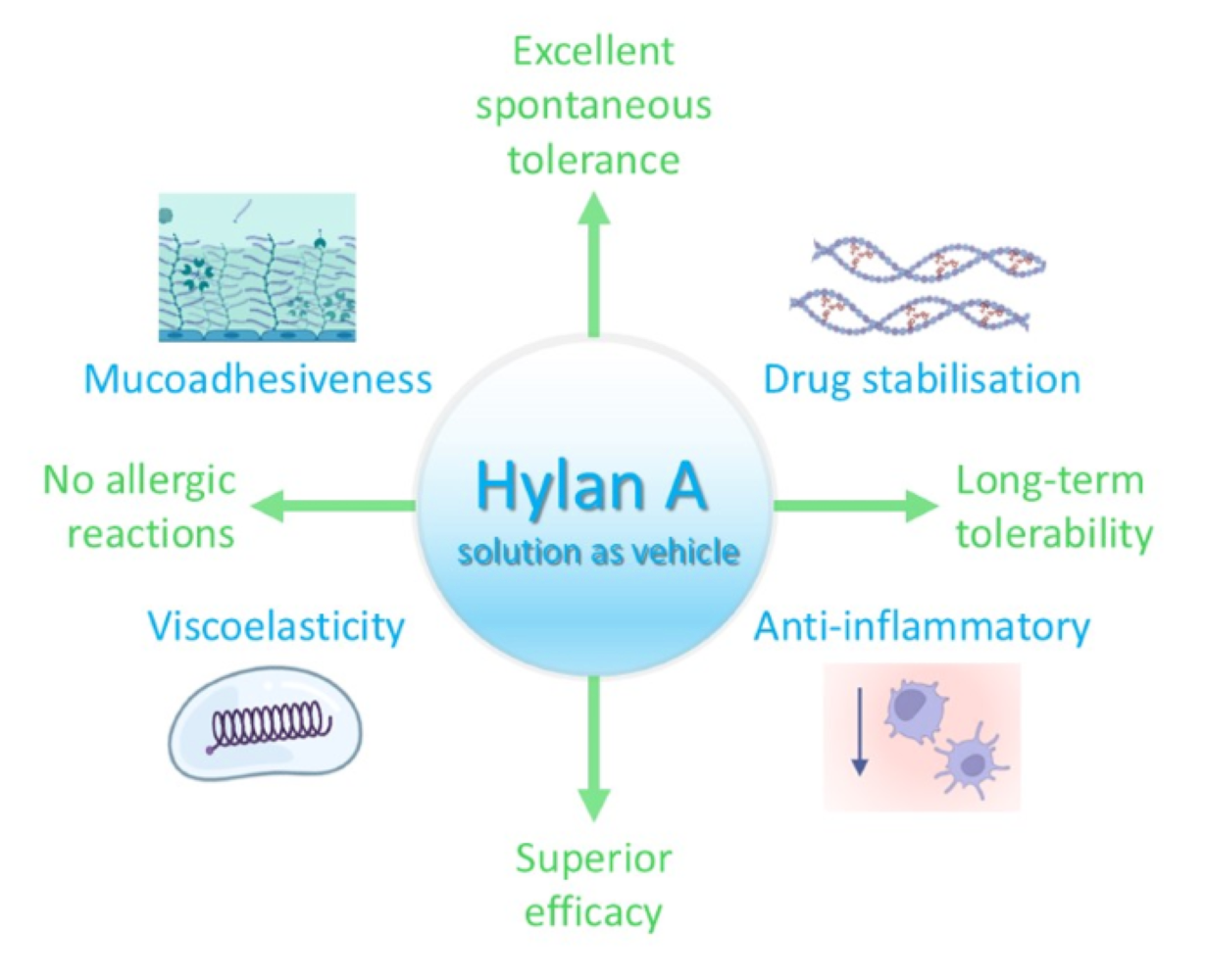

2. Hylan A aqueous Formulation: Enhanced Ocular Surface Retention with Optimal Viscoelastic Properties

3. Improvement of API Solubilization, Stability, and Ocular Transport by Hylan A aqueous Formulation

4. Benefits of Hylan A aqueous Formulation for Ocular Surface Health

5. Hylan A Aqueous Formulation as New Vehicle for Latanoprost in the Management of Elevated Intraocular Pressure

6. Towards a New Generation of Hylan A-Based Eye Drops as API Delivery Vehicles for Ocular Therapeutics

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AHMED, S.; AMIN, M. M.; SAYED, S. Ocular Drug Delivery: a Comprehensive Review. AAPS PharmSciTech 2023, 24, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ALLYN, M. M.; LUO, R. H.; HELLWARTH, E. B.; SWINDLE-REILLY, K. E. Considerations for Polymers Used in Ocular Drug Delivery. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021, 8, 787644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ALMOND, A. Hyaluronan. Cell Mol Life Sci 2007, 64, 1591–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ALSHEIKH, O.; ALZAAIDI, S.; VARGAS, J. M.; AL-SHARIF, E.; ALRAJEH, M.; ALSEMARI, M. A.; ALHOMMADI, A.; ALSAATI, A.; ALJWAISER, N.; ALSHAHWAN, E.; ABDULHAFIZ, M.; ELSAYED, R.; MULLER-LIERHEIM, W. G. K. Effectiveness of 0.15% hylan A eye drops in ameliorating symptoms of severe dry eye patients in Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Ophthalmol 2021, 35, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANDREWS, G. P.; LAVERTY, T. P.; JONES, D. S. Mucoadhesive polymeric platforms for controlled drug delivery. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2009, 71, 505–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARSHINOFF, S.; HOFMANN, I.; NAE, H. Rheological behavior of commercial artificial tear solutions. J Cataract Refract Surg 2021a, 47, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARSHINOFF, S.; HOFMANN, I.; NAE, H. Role of rheology in tears and artificial tears. J Cataract Refract Surg 2021b, 47, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARUFFO, A.; STAMENKOVIC, I.; MELNICK, M.; UNDERHILL, C. B.; SEED, B. CD44 is the principal cell surface receptor for hyaluronate. Cell 1990, 61, 1303–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BAUDOUIN, C.; LABBE, A.; LIANG, H.; PAULY, A.; BRIGNOLE-BAUDOUIN, F. Preservatives in eyedrops: the good, the bad and the ugly. Prog Retin Eye Res 2010, 29, 312–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BAUDOUIN, C.; MYERS, J. S.; VAN TASSEL, S. H.; GOYAL, N. A.; MARTINEZ-DE-LA-CASA, J.; NG, A.; EVANS, J. S. Adherence and Persistence on Prostaglandin Analogues for Glaucoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Ophthalmol 2025, 275, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BAUDOUIN, C.; ROLANDO, M.; BENITEZ DEL CASTILLO, J. M.; MESSMER, E. M.; FIGUEIREDO, F. C.; IRKEC, M.; VAN SETTEN, G.; LABETOULLE, M. Reconsidering the central role of mucins in dry eye and ocular surface diseases. Prog Retin Eye Res 2019, 71, 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BECK, R.; STACHS, O.; KOSCHMIEDER, A.; MUELLER-LIERHEIM, W. G. K.; PESCHEL, S.; VAN SETTEN, G. B. Hyaluronic Acid as an Alternative to Autologous Human Serum Eye Drops: Initial Clinical Results with High-Molecular-Weight Hyaluronic Acid Eye Drops. Case Rep Ophthalmol 2019, 10, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BENITEZ-DEL-CASTILLO, J. M.; ACOSTA, M. C.; WASSFI, M. A.; DIAZ-VALLE, D.; GEGUNDEZ, J. A.; FERNANDEZ, C.; GARCIA-SANCHEZ, J. Relation between corneal innervation with confocal microscopy and corneal sensitivity with noncontact esthesiometry in patients with dry eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2007, 48, 173–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BOHAUMILITZKY, L.; HUBER, A. K.; STORK, E. M.; WENGERT, S.; WOELFL, F.; BOEHM, H. A Trickster in Disguise: Hyaluronan’s Ambivalent Roles in the Matrix. Front Oncol 2017, 7, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BONET, I. J. M.; ARALDI, D.; KHOMULA, E. V.; BOGEN, O.; GREEN, P. G.; LEVINE, J. D. Mechanisms Mediating High-Molecular-Weight Hyaluronan-Induced Antihyperalgesia. J Neurosci 2020, 40, 6477–6488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BONET, I. J. M.; STAURENGO-FERRARI, L.; ARALDI, D.; GREEN, P. G.; LEVINE, J. D. Second messengers mediating high-molecular-weight hyaluronan-induced antihyperalgesia in rats with chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Pain 2022, 163, 1728–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BRON, A. J.; DOGRU, M.; HORWATH-WINTER, J.; KOJIMA, T.; KOVACS, I.; MULLER-LIERHEIM, W. G. K.; VAN SETTEN, G. B.; BELMONTE, C. Reflections on the Ocular Surface: Summary of the Presentations at the 4th Coronis Foundation Ophthalmic Symposium Debate: “A Multifactorial Approach to Ocular Surface Disorders” (August 31 2021). Front Biosci (Landmark Ed); 2022; 27, p. 142. [Google Scholar]

- BUCKLEY, C.; MURPHY, E. J.; MONTGOMERY, T. R.; MAJOR, I. Hyaluronic Acid: A Review of the Drug Delivery Capabilities of This Naturally Occurring Polysaccharide. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CAIRES, R.; LUIS, E.; TABERNER, F. J.; FERNANDEZ-BALLESTER, G.; FERRER-MONTIEL, A.; BALAZS, E. A.; GOMIS, A.; BELMONTE, C.; DE LA PENA, E. Hyaluronan modulates TRPV1 channel opening, reducing peripheral nociceptor activity and pain. Nat Commun 2015, 6, 8095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CRAIG, J. P.; NICHOLS, K. K.; AKPEK, E. K.; CAFFERY, B.; DUA, H. S.; JOO, C. K.; LIU, Z.; NELSON, J. D.; NICHOLS, J. J.; TSUBOTA, K.; STAPLETON, F. TFOS DEWS II Definition and Classification Report. Ocul Surf 2017, 15, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CYPHERT, J. M.; TREMPUS, C. S.; GARANTZIOTIS, S. Size Matters: Molecular Weight Specificity of Hyaluronan Effects in Cell Biology. Int J Cell Biol 2015, 563818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DOGRU, M.; KOJIMA, T.; HIGA, K.; IGARASHI, A.; KUDO, H.; MULLER-LIERHEIM, W. G. K.; TSUBOTA, K.; NEGISHI, K. The Effect of High Molecular Weight Hyaluronic Acid and Latanoprost Eyedrops on Tear Functions and Ocular Surface Status in C57/BL6 Mice. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FALKOWSKI, M.; SCHLEDZEWSKI, K.; HANSEN, B.; GOERDT, S. Expression of stabilin-2, a novel fasciclin-like hyaluronan receptor protein, in murine sinusoidal endothelia, avascular tissues, and at solid/liquid interfaces. Histochem Cell Biol 2003, 120, 361–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FALLACARA, A.; BALDINI, E.; MANFREDINI, S.; VERTUANI, S. Hyaluronic Acid in the Third Millennium. Polymers (Basel) 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FERRARI, L. F.; KHOMULA, E. V.; ARALDI, D.; LEVINE, J. D. CD44 Signaling Mediates High Molecular Weight Hyaluronan-Induced Antihyperalgesia. J Neurosci 2018, 38, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FINEIDE, F.; MAGNO, M.; DAHLO, K.; KOLKO, M.; HEEGAARD, S.; VEHOF, J.; UTHEIM, T. Topical glaucoma medications-Possible implications on the meibomian glands. Acta Ophthalmol 2024, 102, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GALGOCZI, E.; MOLNAR, Z.; KATKO, M.; UJHELYI, B.; STEIBER, Z.; NAGY, E. Cyclosporin A inhibits PDGF-BB induced hyaluronan synthesis in orbital fibroblasts. Chem Biol Interact 2024, 396, 111045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GALOR, A.; GALLAR, J.; ACOSTA, M. C.; MESEGUER, V.; BENITEZ-DEL-CASTILLO, J. M.; STACHS, O.; SZENTMARY, N.; VERSURA, P.; MULLER-LIERHEIM, W. G. K.; BELMONTE, C.; PUJOL-MARTI, J. CORONIS symposium 2023: Scientific and clinical frontiers in ocular surface innervation. Acta Ophthalmol; 2025; 103, pp. e240–e255. [Google Scholar]

- GARANTZIOTIS, S.; SAVANI, R. C. Hyaluronan biology: A complex balancing act of structure, function, location and context. Matrix Biol 2019, 78-79, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GHOSH, P.; HUTADILOK, N.; ADAM, N.; LENTINI, A. Interactions of hyaluronan (hyaluronic acid) with phospholipids as determined by gel permeation chromatography, multi-angle laser-light-scattering photometry and 1H-NMR spectroscopy. Int J Biol Macromol 1994, 16, 237–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GIRI, B. R.; JAKKA, D.; SANDOVAL, M. A.; KULKARNI, V. R.; BAO, Q. Advancements in Ocular Therapy: A Review of Emerging Drug Delivery Approaches and Pharmaceutical Technologies. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOMES, J. A. P.; AZAR, D. T.; BAUDOUIN, C.; EFRON, N.; HIRAYAMA, M.; HORWATH-WINTER, J.; KIM, T.; MEHTA, J. S.; MESSMER, E. M.; PEPOSE, J. S.; SANGWAN, V. S.; WEINER, A. L.; WILSON, S. E.; WOLFFSOHN, J. S. TFOS DEWS II iatrogenic report. Ocul Surf 2017, 15, 511–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOMIS, A.; PAWLAK, M.; BALAZS, E. A.; SCHMIDT, R. F.; BELMONTE, C. Effects of different molecular weight elastoviscous hyaluronan solutions on articular nociceptive afferents. Arthritis Rheum 2004, 50, 314–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GRAESSLEY, W. W. The entanglement concept in polymer rheology. The entanglement concept in polymer rheology 2005, 1–179. [Google Scholar]

- GRASSIRI, B.; ZAMBITO, Y.; BERNKOP-SCHNURCH, A. Strategies to prolong the residence time of drug delivery systems on ocular surface. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 2021, 288, 102342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GUARISE, C.; ACQUASALIENTE, L.; PASUT, G.; PAVAN, M.; SOATO, M.; GAROFOLIN, G.; BENINATTO, R.; GIACOMEL, E.; SARTORI, E.; GALESSO, D. The role of high molecular weight hyaluronic acid in mucoadhesion on an ocular surface model. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2023, 143, 105908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUTER, M.; BREUNIG, M. Hyaluronan as a promising excipient for ocular drug delivery. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2017, 113, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HALDER, A.; KHOPADE, A. J. Physiochemical Properties and Cytotoxicity of a Benzalkonium Chloride-Free, Micellar Emulsion Ophthalmic Formulation of Latanoprost. Clin Ophthalmol 2020, 14, 3057–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HANSEN, I. M.; EBBESEN, M. F.; KASPERSEN, L.; THOMSEN, T.; BIENK, K.; CAI, Y.; MALLE, B. M.; HOWARD, K. A. Hyaluronic Acid Molecular Weight-Dependent Modulation of Mucin Nanostructure for Potential Mucosal Therapeutic Applications. Mol Pharm 2017, 14, 2359–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HANSEN, M. E.; IBRAHIM, Y.; DESAI, T. A.; KOVAL, M. Nanostructure-Mediated Transport of Therapeutics through Epithelial Barriers. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HARRIS, E. N.; BAKER, E. Role of the Hyaluronan Receptor, Stabilin-2/HARE, in Health and Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HEDENGRAN, A.; KOLKO, M. The molecular aspect of anti-glaucomatous eye drops-are we harming our patients? Mol Aspects Med 2023, 93, 101195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HIGA, K.; KIMOTO, R.; KOJIMA, T.; DOGRU, M.; MULLER-LIERHEIM, W. G. K.; SHIMAZAKI, J. Therapeutic Aqueous Humor Concentrations of Latanoprost Attained in Rats by Administration in a Very-High-Molecular-Weight Hyaluronic Acid Eye Drop. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HOLLO, G.; KATSANOS, A.; BOBORIDIS, K. G.; IRKEC, M.; KONSTAS, A. G. P. Preservative-Free Prostaglandin Analogs and Prostaglandin/Timolol Fixed Combinations in the Treatment of Glaucoma: Efficacy, Safety and Potential Advantages. Drugs 2018, 78, 39–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JAYARAM, H.; KOLKO, M.; FRIEDMAN, D. S.; GAZZARD, G. Glaucoma: now and beyond. Lancet 2023, 402, 1788–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JIANG, H.; XU, Z. Hyaluronic acid-based nanoparticles to deliver drugs to the ocular posterior segment. Drug Deliv 2023, 30, 2204206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KAHOOK, M. Y.; RAPUANO, C. J.; MESSMER, E. M.; RADCLIFFE, N. M.; GALOR, A.; BAUDOUIN, C. Preservatives and ocular surface disease: A review. Ocul Surf 2024, 34, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KIM, J. M.; PARK, S. W.; SEONG, M.; HA, S. J.; LEE, J. W.; RHO, S.; LEE, C. E.; KIM, K. N.; KIM, T. W.; SUNG, K. R.; KIM, C. Y. Comparison of the Safety and Efficacy between Preserved and Preservative-Free Latanoprost and Preservative-Free Tafluprost. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KNUDSON, W.; CHOW, G.; KNUDSON, C. B. CD44-mediated uptake and degradation of hyaluronan. Matrix Biol 2002, 21, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KOJIMA, T.; NAGATA, T.; KUDO, H.; MULLER-LIERHEIM, W. G. K.; VAN SETTEN, G. B.; DOGRU, M.; TSUBOTA, K. The Effects of High Molecular Weight Hyaluronic Acid Eye Drop Application in Environmental Dry Eye Stress Model Mice. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KOLKO, M.; GAZZARD, G.; BAUDOUIN, C.; BEIER, S.; BRIGNOLE-BAUDOUIN, F.; CVENKEL, B.; FINEIDE, F.; HEDENGRAN, A.; HOMMER, A.; JESPERSEN, E.; MESSMER, E. M.; MURTHY, R.; SULLIVAN, A. G.; TATHAM, A. J.; UTHEIM, T. P.; VITTRUP, M.; SULLIVAN, D. A. Impact of glaucoma medications on the ocular surface and how ocular surface disease can influence glaucoma treatment. Ocul Surf 2023, 29, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KONSTAS, A. G.; LABBE, A.; KATSANOS, A.; MEIER-GIBBONS, F.; IRKEC, M.; BOBORIDIS, K. G.; HOLLO, G.; GARCIA-FEIJOO, J.; DUTTON, G. N.; BAUDOUIN, C. The treatment of glaucoma using topical preservative-free agents: an evaluation of safety and tolerability. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2021, 20, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LARDNER, E.; VAN SETTEN, G. B. Detection of TSG-6-like protein in human corneal epithelium. Simultaneous presence with CD44 and hyaluronic acid. J Fr Ophtalmol 2020, 43, 879–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LEE-SAYER, S. S.; DONG, Y.; ARIF, A. A.; OLSSON, M.; BROWN, K. L.; JOHNSON, P. The where, when, how, and why of hyaluronan binding by immune cells. Front Immunol 2015, 6, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LERNER, L. E.; SCHWARTZ, D. M.; HWANG, D. G.; HOWES, E. L.; STERN, R. Hyaluronan and CD44 in the human cornea and limbal conjunctiva. Exp Eye Res 1998, 67, 481–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LI, T.; LINDSLEY, K.; ROUSE, B.; HONG, H.; SHI, Q.; FRIEDMAN, D. S.; WORMALD, R.; DICKERSIN, K. Comparative Effectiveness of First-Line Medications for Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 129–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEDIC, N.; BOLDIN, I.; BERISHA, B.; MATIJAK-KRONSCHACHNER, B.; AMINFAR, H.; SCHWANTZER, G.; MULLER-LIERHEIM, W. G. K.; VAN SETTEN, G. B.; HORWATH-WINTER, J. Application frequency-key indicator for the efficiency of severe dry eye disease treatment-evidence for the importance of molecular weight of hyaluronan in lubricating agents. Acta Ophthalmol 2024, 102, e663–e671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MOISEEV, R. V.; MORRISON, P. W. J.; STEELE, F.; KHUTORYANSKIY, V. V. Penetration Enhancers in Ocular Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MONSLOW, J.; GOVINDARAJU, P.; PURE, E. Hyaluronan-a functional and structural sweet spot in the tissue microenvironment. Front Immunol 2015, 6, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MÜLLER-LIERHEIM, W. G. Hylan a: a novel transporter for Latanoprost in the treatment of ocular hypertension. Biomedical Journal of Scientific & Technical Research 2021, 37. [Google Scholar]

- MÜLLER-LIERHEIM, W. G. K. Why Chain Length of Hyaluronan in Eye Drops Matters. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NAGAI, N.; OTAKE, H. Novel drug delivery systems for the management of dry eye. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2022, 191, 114582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ÖZKAN, G.; TURHAN, S. A.; TOKER, E. Effect of high and low molecular weight sodium hyaluronic acid eye drops on corneal recovery after crosslinking in keratoconus patients. BMJ Open Ophthalmol 2025, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PATIL, S.; SAWALE, G.; GHUGE, S.; SATHAYE, S. Quintessence of currently approved and upcoming treatments for dry eye disease. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2025, 263, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PERIMAN, L. M.; MAH, F. S.; KARPECKI, P. M. A Review of the Mechanism of Action of Cyclosporine A: The Role of Cyclosporine A in Dry Eye Disease and Recent Formulation Developments. Clin Ophthalmol 2020, 14, 4187–4200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ROUSE, J. J.; WHATELEY, T. L.; THOMAS, M.; ECCLESTON, G. M. Controlled drug delivery to the lung: Influence of hyaluronic acid solution conformation on its adsorption to hydrophobic drug particles. Int J Pharm 2007, 330, 175–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RUPPERT, S. M.; HAWN, T. R.; ARRIGONI, A.; WIGHT, T. N.; BOLLYKY, P. L. Tissue integrity signals communicated by high-molecular weight hyaluronan and the resolution of inflammation. Immunol Res 2014, 58, 186–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SHETTY, R.; DUA, H. S.; TONG, L.; KUNDU, G.; KHAMAR, P.; GORIMANIPALLI, B.; D’SOUZA, S. Role of in vivo confocal microscopy in dry eye disease and eye pain. Indian J Ophthalmol 2023, 71, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SMART, J. D. The basics and underlying mechanisms of mucoadhesion. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2005, 57, 1556–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TIFFANY, J. M. Viscoelastic properties of human tears and polymer solutions. Adv Exp Med Biol 1994, 350, 267–70. [Google Scholar]

- VAN SETTEN, G. B.; BAUDOUIN, C.; HORWATH-WINTER, J.; BOHRINGER, D.; STACHS, O.; TOKER, E.; AL-ZAAIDI, S.; BENITEZ-DEL-CASTILLO, J. M.; BECK, R.; AL-SHEIKH, O.; SEITZ, B.; BARABINO, S.; REITSAMER, H. A.; MULLER-LIERHEIM, W. G. K. The HYLAN M Study: Efficacy of 0.15% High Molecular Weight Hyaluronan Fluid in the Treatment of Severe Dry Eye Disease in a Multicenter Randomized Trial. J Clin Med 2020a, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VAN SETTEN, G. B.; STACHS, O.; DUPAS, B.; TURHAN, S. A.; SEITZ, B.; REITSAMER, H.; WINTER, K.; HORWATH-WINTER, J.; GUTHOFF, R. F.; MULLER-LIERHEIM, W. G. K. High Molecular Weight Hyaluronan Promotes Corneal Nerve Growth in Severe Dry Eyes. J Clin Med 2020b, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VILLANI, E.; SACCHI, M.; MAGNANI, F.; NICODEMO, A.; WILLIAMS, S. E.; ROSSI, A.; RATIGLIA, R.; DE CILLA, S.; NUCCI, P. The Ocular Surface in Medically Controlled Glaucoma: An In Vivo Confocal Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2016, 57, 1003–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WANG, X.; LIU, X.; LI, C.; LI, J.; QIU, M.; WANG, Y.; HAN, W. Effects of molecular weights on the bioactivity of hyaluronic acid: A review. Carbohydr Res 2025, 552, 109472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WANG, Y.; WANG, C. Novel Eye Drop Delivery Systems: Advance on Formulation Design Strategies Targeting Anterior and Posterior Segments of the Eye. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WEINREB, R. N.; AUNG, T.; MEDEIROS, F. A. The pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma: a review. JAMA 2014, 311, 1901–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YANG, Y.; HUANG, C.; LIN, X.; WU, Y.; OUYANG, W.; TANG, L.; YE, S.; WANG, Y.; LI, W.; ZHANG, X.; LIU, Z. 0.005% Preservative-Free Latanoprost Induces Dry Eye-Like Ocular Surface Damage via Promotion of Inflammation in Mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2018, 59, 3375–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZEPPIERI, M.; GAGLIANO, C.; TOGNETTO, D.; MUSA, M.; ROSSI, F. B.; GREGGIO, A.; GUALANDI, G.; GALAN, A.; BABIGHIAN, S. Unraveling the Mechanisms, Clinical Impact, Comparisons, and Safety Profiles of Slow-Release Therapies in Glaucoma. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZHANG, C.; HUANG, Q.; FORD, N. C.; LIMJUNYAWONG, N.; LIN, Q.; YANG, F.; CUI, X.; UNIYAL, A.; LIU, J.; MAHABOLE, M.; HE, H.; WANG, X.; DUFF, I.; WANG, Y.; WAN, J.; ZHU, G.; RAJA, S. N.; JIA, H.; YANG, D.; DONG, X.; CAO, X.; TSENG, S. C.; HE, S.; GUAN, Y. Human birth tissue products as a non-opioid medicine to inhibit post-surgical pain. Elife 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZHANG, Y.; SUN, T.; JIANG, C. Biomacromolecules as carriers in drug delivery and tissue engineering. Acta Pharm Sin B 2018, 8, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZHOU, B.; WEIGEL, J. A.; FAUSS, L.; WEIGEL, P. H. Identification of the hyaluronan receptor for endocytosis (HARE). J Biol Chem 2000, 275, 37733–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZHU, S. N.; NOLLE, B.; DUNCKER, G. Expression of adhesion molecule CD44 on human corneas. Br J Ophthalmol 1997, 81, 80–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Study type | Model / Patients | Comparators | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kojima et al., 2020 | Preclinical | Mice model of environmental dry eye disease | Low molecular weight HA eye drops, secretagogue eye drops |

Improved tear film stability, reduced ocular surface damage, and less inflammation with 0.15% hylan A eye drops |

|

Beck et al., 2019 |

Clinical |

11 patients on treatment with autologous serum eye drops |

Autologous serum eye drops |

0.15% hylan A eye drops are effective for severe ocular severe disease and may even replace autologous serum eye drops |

|

van Setten et al., 2020a |

Clinical HYLAN M study |

84 patients with severe dry eye disease |

Optimized artificial tear treatments |

Switching from optimized artificial tear treatments to 0.15% hylan A eye drops significantly improved symptoms, including visual stability, discomfort and pain, already after 4 weeks |

|

van Setten et al., 2020b |

Clinical Subgroup analysis from the HYLAN M study |

16 patients |

Optimized artificial tear treatments |

Switching from optimized artificial tear treatments to 0.15% hylan A eye drops promoted corneal nerve growth after 8 weeks |

|

Medic et al., 2024 |

Clinical Subgroup analysis from the HYLAN M study |

47 patients |

HA-containing artificial tears (15 commercial brands with diverse HA molecular weight) |

0.15% hylan A eye drops have a superior clinical effect as compared to other eye drops containing HA with a lower molecular weight, both in terms of dropping frequency and symptoms |

|

Özkan et al., 2025 |

Clinical |

63 eyes of 55 patients with keratoconus following corneal crosslinking (CXL) |

Low molecular weight HA eye drops |

Faster regeneration of corneal nerves and sensitivity after CXL with 0.15% hylan A eye drops and improvement of ocular symptoms Three months after CXL, the group treated with 0.15% hylan A eye drops showed a lower presence of inflammation-related immune cells compared to the group receiving low molecular weight HA eye drops |

|

Study |

Study type |

Model / Patients |

Comparators |

Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Müller-Lierheim, 2021 |

Formulation solubility and stability |

N/A |

N/A |

A preservative-free 0.15% hylan A solution in isotonic phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) provides a stable vehicle for 20 μg/mL latanoprost, enhancing latanoprost solubility by 75% |

|

Dogru et al., 2023 |

Preclinical |

Standard strain mice |

Commercial eye drops with 50μg/mL latanoprost |

Unlike the commercial latanoprost eye drops, a hylan A-based eye drop formulation with 14 μg/mL latanoprost preserved ocular surface parameters comparable to untreated controls, while achieving a similar IOP-lowering effect as the commercial product |

|

Higa et al., 2024 |

Preclinical |

Standard strain rat |

Commercial eye drops with 50μg/mL latanoprost |

A hylan A-based eye drop formulation with 14 μg/mL latanoprost achieved therapeutic levels of latanoprost in the animal’s aqueous humour comparable to the 50 μg/mL commercial formulation |

|

Müller-Lierheim, 2021 |

Proof-of-concept |

One subject with ocular hypertension |

Commercial eye drops with 50μg/mL latanoprost |

A hylan A-based eye drop formulation with 20 μg/mL latanoprost showed a superior IOP-lowering effect compared to a commercial latanoprost eye drop, despite the latter having a higher API concentration |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).