1. Introduction

Developmental delay (DD) is a condition that results in difficulties due to disruptions in normal brain development, with delayed motor development being a common feature [

1]. It includes impairments in spontaneous motor activity and deficits in postural reflexes observed during a neurological examination. Vojta therapy plays a significant role in both the diagnostic evaluation and treatment of children with DD [

2]. Rehabilitation of infants with DD enables, through the plasticity of the nervous system, the reprogramming of abnormal postural and locomotor patterns towards more physiological ones [

2].

The literature examines various factors that may influence motor development in one-year-old infants. These factors include the mother's age at the time of delivery [

3,

4], the method of delivery (caesarean section) [

4,

5], the duration of breastfeeding [

6], the child's sex (with male sex being a factor) [

4,

7], birth age (prematurity) [

8], low birth weight [

9], the APGAR score [

10], and the age at which rehabilitation begins [

11]. All of these are unfortunately beyond our control. Therefore, early diagnosis of the disorder, early commencement of therapy, and the selection of appropriate rehabilitation methods are crucial for the child’s future development.

Vojta therapy (ICD-9 93.3806) encompasses both a comprehensive diagnostic component and a therapeutic element. During the diagnostic process, spontaneous mobility, postural reactions, and primary reflexes are assessed [

12]. Vojta’s neurological examination is an effective screening tool that can be applied to all risk infants [

13]. The foundation of Vojta’s techniques lies in the elicitation of a reflex that triggers natural movement patterns, both global and local (hence the term reflex locomotion method). This is achieved by stimulating selected key points on the child's body in strictly defined starting positions [

1,

14]. Vojta therapy has proven to be highly effective in rehabilitating children under the age of 6 months, as such young children are unable to consciously perform correct movements, making reflex locomotion particularly helpful. In a study by Gomez-Conesa et al., Vojta therapy was found to be more effective than other neurodevelopmental methods in preterm children [

15]. Neuromodulation of motor control areas has been confirmed by research examining the neurophysiological mechanisms underlying the therapeutic efficacy of the Vojta method [

16].

The craniosacral therapy (CST) is another therapy used in the rehabilitation of children. In the 1930s, the founder of cranial osteopathy, William Sutherland, noticed that the bones of the cranium exhibit a certain degree of mobility [

17], and the entire craniosacral system has rhythmic activity that is influenced by the respiratory and cardiovascular systems. The movement within the craniosacral system can be modulated through gentle pressure. Although osteopathic techniques are recognized as effective in the therapy of prematurely born children, the data concerning the effectiveness of CST is contradictory. This may be due to the lack of objective assessment methods for these techniques, particularly in small children [

18,

19]. Currently, CST is included in the Benchmarks for Osteopathic Education of the WHO, and in Poland, it is considered a medical procedure with the ICD-9 code 93.3824. However, biological plausibility, assessment reliability, and clinical effectiveness remain subjects of debate, as there is no high-quality evidence suggesting a positive effect of CST. There is controversy regarding whether such a small movement can influence the human body and whether intervention in this mechanism can have a therapeutic effect. The answer to this question is not straightforward, as no conclusive research results have been provided to date. Nevertheless, the normalization of autonomic system activity, the release of musculofascial structures, and the restoration of central nervous system (CNS) plasticity have been observed [

20]. The therapy is considered effective for problems such as chronic pain syndromes or developmental disorders on the autism spectrum [

21,

22]. Due to the subtle form of applied touch, craniosacral therapy is also used in cases of gastrointestinal dysfunctions, postural asymmetry, breastfeeding initiation, and plagiocephaly [

23]. CST includes delicate, cautious, and non-invasive techniques, which do not have negative effects on the development of spontaneous motor skills in healthy infants. Therefore, it can be concluded that it will be safe to apply therapeutically to prematurely born children, who are extremely sensitive to touch [

23]. Given the different effects offered by these two methods, their additive effect in the rehabilitation of children with DD cannot be ruled out. Despite the lack of clear evidence, craniosacral therapy is also part of the rehabilitation program in Poland. This study aims to compare the effectiveness of Vojta therapy used alone and in combination with CST.

2. Materials and Methods

This is an observational, retrospective, preliminary study in which the effectiveness of the procedures used in one rehabilitation center in Poland was analyzed. No intervention was undertaken by the researchers of this study.

Observation period: January 1, 2014 – November 30, 2019. Data collection: January 1, 2022 – July 1, 2022.

Approval for the study was obtained from the Bioethics Committee of XXXXXX (KB-108/2019).

2.1. How the Center Works

At the Center, children with DD are selected for therapy by pediatricians and then treated by physiotherapists until recovery (i.e., resolution of disease-related disorders; sometimes rehabilitation may continue for many years or even be life-long) or until the parents decide to discontinue treatment. The decision on how to treat the child is made individually each time. Before therapy, the doctor performs functional diagnostics using the Vojta method to assess developmental disorders and, based on the results, refers patients for rehabilitation. For early neurological diagnosis, diagnostic procedures are carried out according to Vojta, including observation of spontaneous motor skills, reflexes, and the 7 postural responses. Evaluation of postural responses is a good tool for monitoring the fundamental functioning of the nervous system during the first months of life, and therefore, therapeutic progress in the study was assessed based on these reactions.

In general, Vojta therapy is used at the center as the primary therapy for all children and it was carried out in this study by one physiotherapist specialized in the Vojta method.

The course of therapy for the children in the study consists of:

Meeting with the physiotherapist to discuss and demonstrate the exercises (lasting 60 minutes). Initially, parents learn one Vojta position with 1 or 2 stimulation zones, and then proceed to the next ones, with a maximum of 2-3 stimulation zones. The meetings take place once a week, during which new exercises are taught, and previously performed exercises are re-educated if parents report any issues. At home, the exercises last 4 minutes at the beginning, and their duration is gradually extended to a maximum of 10 minutes.

The Craniosacral method is also recommended as a complementary procedure. It is performed by one therapist (a certified craniosacral therapy specialist) from the start or added during the rehabilitation process, as there are no specific guidelines or protocols. Both therapies are reimbursed by the state. Craniosacral therapy is performed in 4 times a month.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for the Study

For this study, the patient's status at the beginning of therapy (W0) and 6 months later (W6) was recorded blindly, based on individual records collected earlier for another study.

The following inclusion criteria were applied when choosing participants for the study:

Developmental delay diagnosis based on the pediatrician’s opinion, with a decision that the child requires rehabilitation based on the 7 postural responses from the Vojta method.

A score of 8-10 on the APGAR scale in the first minute of life.

No major birth defects documented that could lead to a diagnosis of genetic disorders.

The child’s age at the time of the eligibility assessment for rehabilitation: 1-6 months (of life), based on completed months of life.

Available information regarding an abnormal result of the Vojta test, defined as at least 6 abnormal postural responses (marked as abnormal [AN] or delayed [OP] in the test report), with abnormal muscle tension, indicating moderate to severe DD.

Available information regarding the first medical examination (during the first visit [W0]) and a follow-up visit after 6 months (W6) on the determined date, maintaining the defined timeframe (5.5-6 months after W0).

Exclusion criteria (medical history was excluded from the analysis even if one of the following exclusion criteria was met):

Children who obtained a score of <8 points on the APGAR scale in the first minute of life.

Suspicion of any major (significant) birth defect, congenital defect syndrome (e.g., Down syndrome, Sotos syndrome), and/or indications for consultation at a Genetics Clinic based on pediatric records.

Age <1 month or >6 months.

<6 abnormal reactions during the Vojta test at the first eligibility visit, indicating mild or very mild DD.

To avoid bias that could result from different skill levels of therapists, only medical records containing information on who was responsible for the Vojta therapy and craniosacral therapy application were used. According to the Vojta therapy protocol, only individuals treated by MA (a team member) were taken into consideration.

2.3. Data Preparation for the Analysis Process

We included 66 infant patients, who were diagnosed with delayed motor development based on the motor functional evaluation scale according to Dr. Vojta V. During the first and control examination in all patients were used the following postural reflexes: Vojta reaction, Head control reaction, Peiper’s Suspension Test, Colli’s suspension test, Collis’ horizontal suspension test, Landau reaction, Axillary suspension test.

Children who had completed six months of therapy and had efficacy results documented in their medical records were divided by the researchers into group A (children treated with Vojta therapy alone) and group B (children treated with Vojta therapy combined with craniosacral therapy).

To describe the groups, information was collected on the following factors: the age at which the children started therapy, the APGAR score at the first minute of life, gestational week at birth, mode of delivery, sex, birth weight, mother's age at delivery and duration of breastfeeding.

To assess effectiveness, improvement was defined as follow: better results in 7 postural responses during W6 (means improvement) were marked when fewer inappropriate tests were detected compared to W0. If the same number (or more) of test results were found at W6 as at W0, “no improvement” was marked.

All patient data were analyzed as anonymous and were processed in accordance with the Data Protection Act of 10 May 2018.

As both spontaneous mobility and primary reflexes influence how a child will respond to 7 postural responses on examination, the number of abnormal postural reactions on examination during W6 was assessed and compared with those from W0.

Statistical Analysis

Ten variables were statistically analyzed. Four of them were dichotomous: Type of treatment, Mode of delivery, Sex of the child and W6 score; six of them were variables on the ratio scales: Mother's age at delivery, Duration of breastfeeding, APGAR score, Gestational week at birth, Birth weight and Age of the child.

For variables on the ratio scales, basic descriptive statistics were determined. For variables with a normal distribution, those included: count, mean value, standard deviation and 95% confidence interval; for variables not meeting the condition of normality of distribution, those were: median and range. The normality of the distributions of the variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk W-test. The statistical significance of differences between the mean values of the analyzed parameters in compared groups was assessed according to the result of the Shapiro-Wilk W-test with the parametric Student's t-test for independent samples for variables with a normal distribution or with the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test for variables that did not meet this condition.

We also assessed the global statistical significance of differences between the means in the compared groups for all analyzed variables on the ratio scales at the same time by conducting a meta-analysis. The developed meta-analysis model used OR and 95% CI as the metrics to be tested, and global statistical significance was calculated based on a variable effects model. The results of the meta-analysis were shown in a standard forest plot.

The basis for assessing the statistical significance of the relationships between the variables on the dichotomous scales will be the non-parametric chi2-test and a univariate logistic regression model, the results of which will be used for determining OR values.

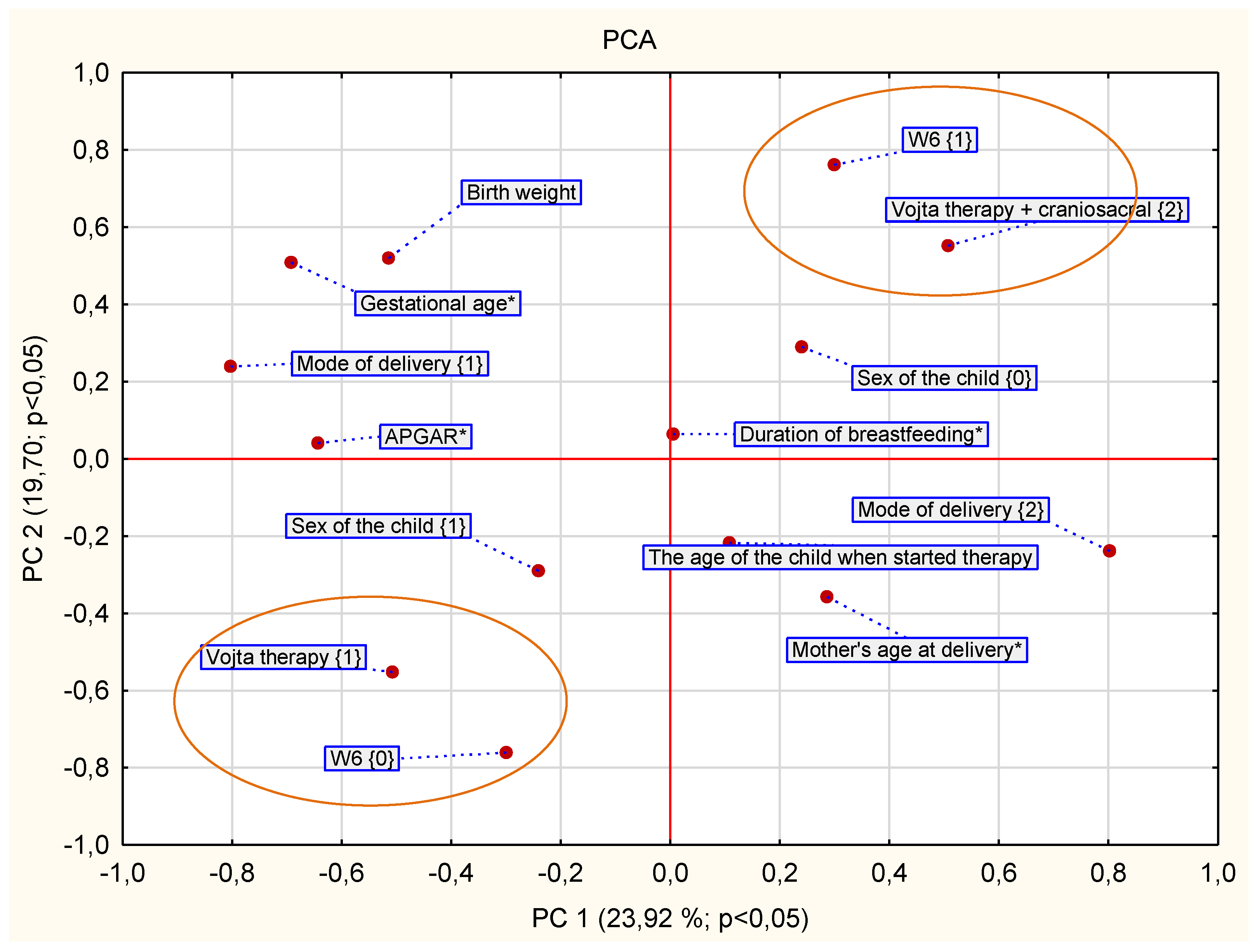

Overall correlations between all analyzed variables were initially assessed using generalized principal component analysis (GPCA). The constructed GPCA model was estimated using the NIPALS iterative algorithm. The convergence criterion was set at 0.00001, with the maximum iteration number of 50. The number of components was determined by setting the maximum predictive capability Q^2 using the five-fold cross-checking method. The resulting optimal GPCA model was reduced to 2 principal components. The GPCA analysis, the results of which are shown in the PC1 vs. PC2 loadings plot, allowed the preliminary selection of variables with the most significant impact on the variability in variance in the analyzed database. Variables selected in this way were then subjected to further statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using the software STATISTICA PL® version 13.3.

Results

During the 7-month data collection period, 66 records with previous consent were analyzed to be eligible for the study. Fifty-one children from this group participated in at least six months of therapy, meeting the follow-up period criterion. The parents of 15 children who participated previously in the rehabilitation process, were find as gave up the therapy for their children from various reasons: i) finding that therapeutic effects are satisfactory, ii) prolonged illness of the parent/guardian or child, iii) change of place of therapy.

None of the variables describing the assessed groups was statistically different (

Table 1).

There were 32 children in group A, including 16 boys (50%) and 16 girls (50%). In group B, there were 19 children including 9 (47.36%) boys and 10 (52.63%) girls. Differences between groups by sex were not statistically significant (chi=0.03; p=0.86) either.

In the group of patients rehabilitated using Vojta therapy (group A), 17 (56.86%) children were born naturally and 15 (46.87%) by caesarean section. In the Vojta + craniosacral group (group B), 5 (26.31%) children were born naturally and 14 (73.68%) by caesarean section. Differences between groups for this variable were not statistically significant (chi=3.49; p=0.06).

In total, for the whole group of children observed (A + B, N=51), improvement after 6 months of rehabilitation was observed in 39 (76.47%) children – 21 ( 65.62 %) patients in group A and 18 (76.47%) in group B, (p=0.017) (

Table 2,

Figure 1), OR= 9.42 (+95%Cl = 0.102; -95%Cl = 4.3855; p=0.04).

Correlations between selected key variables were evaluated using the GPCA method. The GPCA ordered the variables according to how close they were together and thus revealed their relationship. The occurrence of variable W6=1 (improvement after 6 months) in one quadrant with the variable "combined therapy” (Vojta and craniosacral therapy applied together) indicates that better outcomes were observed in children who underwent combined therapy.

4. Discussion

The aforementioned study analyzed differences in terms of rehabilitation outcomes in DD children after two different therapy programs were applied over 6 months. In the group of young patients with additional intervention in the form of CST, there was a significantly higher percentage of children with improvement in motor scores of Vojta postural responses compared to therapy using only Vojta therapy. The addition of CST to rehabilitation significantly increased the chance of improvement, which was 9.42 times higher compared to the group undergoing Vojta therapy alone. This result is also reflected in the GPCA analysis (

Figure 1), which confirms the link between the use of combined therapy and the improvement achieved. It should be noted that the two groups did not differ at baseline in any characteristics that could have influenced the rehabilitation results (see characteristics of study groups), which highlights the strength of the combined therapeutic action of the two methods. As mentioned, the researchers who analyzed the results had no control over the therapeutic decisions of the physiotherapist providing the rehabilitation and the analysis was retrospective. As it can be expected, the decision for combined therapy (Vojta and craniosacral therapy) is mainly made when the prognosis for improvement is worse. Although this is not reflected in the characteristics of the patients, it can be assumed that it was the therapist's experience that resulted in the enrichment of the rehabilitation with CST for children with worse prognoses. In our previous observational, prospective study [

12] conducted on the same group of children, we did not show that after 3 months the effects of therapy were different for Vojta vs. Vojta + craniosacral therapy groups. The changes shown between the groups after the 6-month follow-up may be due to both the length of application and the fact that the therapist added additional therapy (CST) for children who did not achieve results during the first three months. In conclusion, CST could be combined with the standard Vojta therapy at any stage of rehabilitation and its addition depends on several factors: the child's health status, the availability of a therapist, parental consent (this therapy, unlike Vojta therapy, is only performed by a therapist). CST is performed once a week in a therapy session independent of Vojta therapy. However, this seemingly chaotic and unregulated way of managing children with DD allows the therapist to intervene in the therapy at every stage aiming to improve the health of the young patients, without the need to discuss it again with the pediatrician.

The mechanism of action of CST has not been fully understood despite its widespread and long-standing use in physiotherapy practice. This therapy is based on the application of gentle touch to the structures of the nervous system in the head and spine, making it a safe method, which also makes it suitable for even the youngest children. This method addresses abnormalities in the atlas-occipital region and influences both the craniosacral rhythm and the autonomic system [

24]. Consequently, it has a wide range of applications, such as adjunctive therapy for migraines, where it has shown great effectiveness [

25]. In the case of children, the application of very gentle touch may be particularly relevant (in addition to the dedicated technique). In the study by Leon-Bravo et al. (2025), it was shown that adding CST to balance and coordination training in children with neurodevelopmental dysfunctions accelerates and improves the effects of therapy [

26]. Toning with CST after Vojta therapy can enhance the therapeutic effect of the treatment. Oparsky's study found an increase in heart rate after Vojta therapy and the impact of the therapy on the autonomic system in relation to unpleasant stimulation in adults [

27]. Similarly, in Martinek's study, there was an increase in the activity of the secondary sensory cortex that activates in response to pressure and the associated occurrence of discomfort or pain [

28]. Moreover, activation of this area of the brain correlates with changes in salivary cortisol levels in Vojta-treated infants, which may also be related to unpleasant sensations during therapy [

29]. The application of CST may be significant in toning excessive activity of the sympathetic nervous system and may help lower heart rate frequency, as proven by studies by Cook et al. (2024), where the decrease in high-frequency heart rate was interpreted as an increase in parasympathetic system activity after CST [

31]. Studies by Wójcik et al. (2023) showed that CST significantly affects cortisol levels in the blood (5 sessions, once a week) in male firefighter cadets [

31].

Based on the above, it can be concluded that CST, through its balancing of the autonomic nervous system, will reduce the stimulation of the autonomic and endocrine systems and, by acting as a toning technique, may influence better coordination and consolidation of correct movement patterns developed during Vojta therapy.

The results of this study significantly contribute to the current knowledge of the effectiveness of methods used for the rehabilitation of infants, for which there are currently no large randomized clinical trials (RCTs). Given the difficulties in organizing and conducting such trials, we believe that any article on this subject is an important contribution to science, especially as the results contribute to new practical possibilities. From a clinical perspective, we suggest considering the addition of craniosacral therapy to the therapeutic regimen in children undergoing rehabilitation because of DD. However, it is undoubtedly advisable to conduct further studies on this subject, including long-term follow-ups and recording the duration of therapy applied (frequency, length of sessions, and duration of rehabilitation with this method) to optimize recommendations.

Limitations

This study has limitations due to the small number of analysed medical-records. Additionally, some children do not fully cooperate during therapy. The same applies to their participation in the physical therapy program and how they respond to the physical therapy tasks. An important limitation is the involvement of parents in carrying out the therapy at home, as well as the lack of monitoring of the therapy performed by the parents. All these problems were mentioned in the analysed medical-records.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S. and M.A.; methodology, E.S., N.K.; software, N.K. and D.M; validation, M.A., E.S. and D.M.; formal analysis, D.M.; N.K., J.M. investigation, M.A.; resources, N.K., K.B. data curation, M.A., N.K.; writing—original draft preparation, N.K., E.S., K.B., J.M.; writing—review and editing, E.S., D.M.; supervision, E.S.; project administration, N.K., E.S., All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.