Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

11 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents, Samples and Materials

2.2. Generation and Characterization of Waveforms

2.3. HS-SPME-GC/MS Procedure

2.3.1. Sample Preparation and Wave Treatment of Wine

2.3.2. Triple SPME Procedure

2.3.3. GC/MS Instrumentation

2.3.4. GC/MS Analysis Procedure

2.3.5. Statistical Treatment of HS-SPME-GC/MS Results

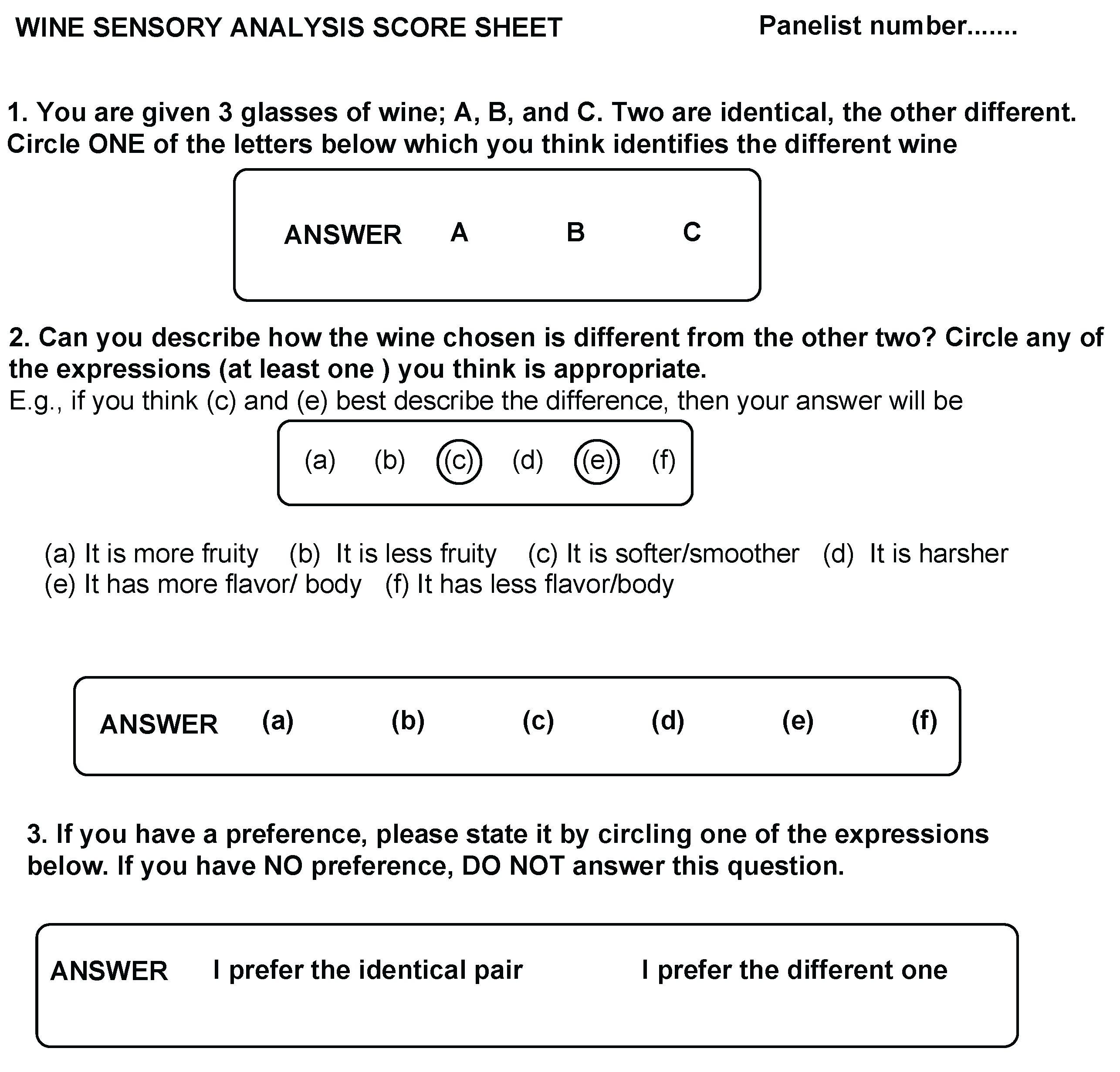

2.4. Sensory (Difference Test, Triangle Version One-Sided, P=1/3) Analysis

3. Results

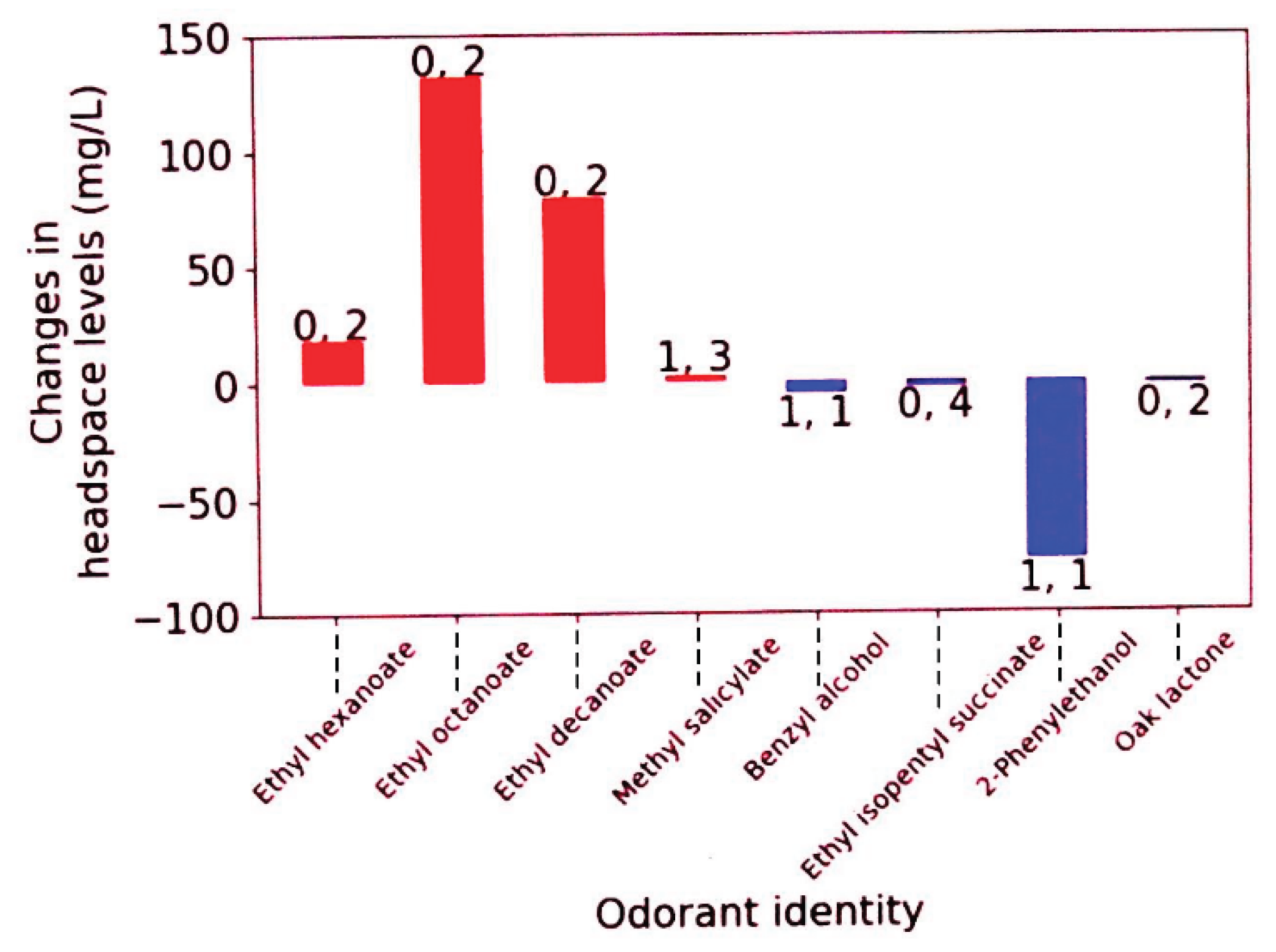

3.1. HS-SPME-GC/MS Analysis

3.2. Sensory Analysis

4. Discussion

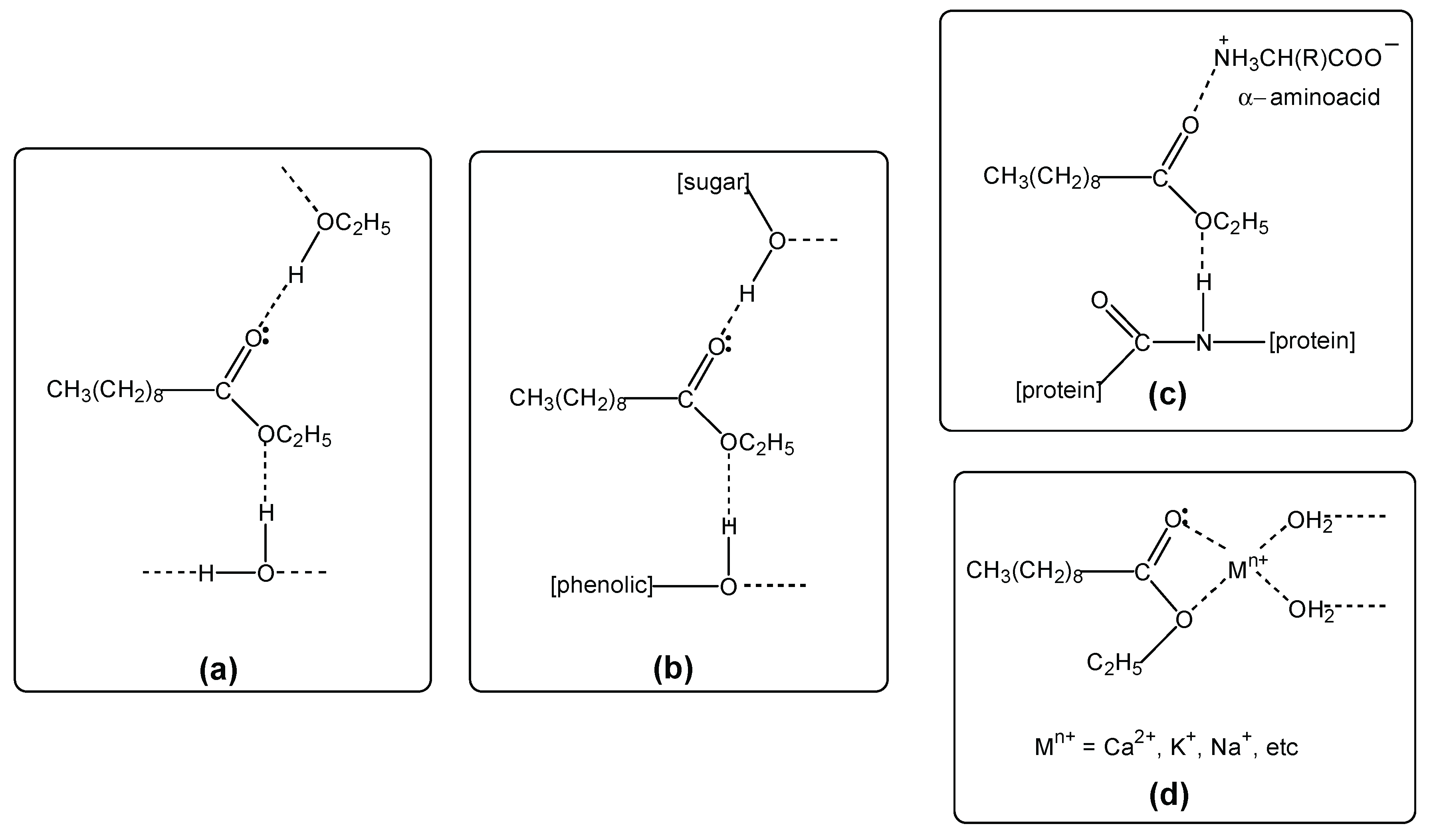

4.1. HS-SPME-GC-MS Results

- (a)

- Volatile hydrogen bonded associations in wine vapor (headspace).

- (b)

- Non-volatile hydrogen bonded associations in wine, involving sugars and phenolics.

- (c)

- Non-volatile hydrogen bonding and ion-dipole associations in wine, involving aminoacids and proteins.

- (d)

- Non-volatile ion-dipole associations in wine, involving metal ions (minerals).

4.2. Sensory Analysis

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feng, Y.; T. Yang; Y. Zhang; A. Zhang; L. Gai and D. Niu. Potential applications of pulsed electric field in the fermented wine industry. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1048632. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, Y.; M. Marangon and C. Mayr Marangon. The Application of Non-Thermal Technologies for Wine Processing, Preservation, and Quality Enhancement. Beverages 2023, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, B. and E. Anli. Pulsed electric fields (PEF) applications on wine production: A review. BIO Web Conf. 2017, 9, 02008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, H.K. and E. Dündar. New techniques for wine aging. BIO Web Conf. 2017, 9, 02012. [Google Scholar]

- García Martín, J.F. and D.-W. Sun. Ultrasound and electric fields as novel techniques for assisting the wine ageing process: The state-of-the-art research. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2013, 33, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; I. Loira; A. Morata; J.A. Suárez-Lepe; M.C. González and D. Rauhut. Shortening the ageing on lees process in wines by using ultrasound and microwave treatments both combined with stirring and abrasion techniques. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2016, 242, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-García, R.; M. C. Díaz-Maroto; M. Arévalo Villena; M.S. Pérez-Coello and M.E. Alañón. Ultrasound and microwave techniques as physical methods to accelerate oak wood aged aroma in red wines. LWT 2023, 179, 114597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natolino, A. ; T. Roman; G. Nicolini and E. Celotti. Innovations on red winemaking process by ultrasound technology. Enoform Web Conference, 2021.

- Natrella, G.; M. Noviello; A. Trani; M. Faccia and G. Gambacorta. The Effect of Ultrasound Treatment in Winemaking on the Volatile Compounds of Aglianico, Nero di Troia, and Primitivo Red Wines. Foods 2023, 12, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Díez, R.; M. Matos; L. Rodrigues; M.R. Bronze; S. Rodríguez-Rojo; M.J. Cocero and A.A. Matias. Microwave and ultrasound pre-treatments to enhance anthocyanins extraction from different wine lees. Food Chem. 2019, 272, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Córdoba, C.; E. Durán-Guerrero and R. Castro. Olfactometric and sensory evaluation of red wines subjected to ultrasound or microwaves during their maceration or ageing stages. LWT 2021, 144, 111228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Q. Li; H. Xue and J. Tang. Ultrasound-assisted enzymatic extraction of anthocyanins from grape skins: optimization, identification, and antitumor activity. J. Food Sci. 2020, 85, 3731–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Q.; Y. Tang; X. Wu; Q. Luo; W. Zhang; H. Liu; Y. Fang; X. Yue and Y. Ju. Combined ultrasound and low temperature pretreatment improve the content of anthocyanins, phenols and volatile substance of Merlot red wine. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023, 100, 106636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Q. Qiu; Y. Xu; J. Zhu; M. Yuan and M. Chen. Fast aging technology of novel kiwifruit wine and dynamic changes of aroma components during storage. FS&T 2023, 43, e98422. [Google Scholar]

- Comuzzo, P.; S. Voce; C. Grazioli; F. Tubaro; M. Marconi; G. Zanella and M. Querzè. Pulsed Electric Field Processing of Red Grapes (cv. Rondinella): Modifications of Phenolic Fraction and Effects on Wine Evolution. Foods 2020, 9, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delso, C.; A. Berzosa; J. Sanz; I. Álvarez and J. Raso. Pulsed electric field processing as an alternative to sulfites (SO2) for controlling saccharomyces cerevisiae involved in the fermentation of Chardonnay white wine. Food Res. Int. 2023, 165, 112525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delso, C.; A. Berzosa; J. Sanz and I. Álvarez. Microbial Decontamination of Red Wine by Pulsed Electric Fields (PEF) after Alcoholic and Malolactic Fermentation: Effect on Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Oenococcus oeni, and Oenological Parameters during Storage. Foods 2023, 12, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Darra, N.; H. N. Rajha; M.-A. Ducasse; M.F. Turk; N. Grimi; R.G. Maroun; N. Louka and E. Vorobiev. Effect of pulsed electric field treatment during cold maceration and alcoholic fermentation on major red wine qualitative and quantitative parameters. Food Chem. 2016, 213, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evrendilek, A.G. Pulsed Electric Field Processing of Red Wine: Effect on Wine Quality and Microbial Inactivation. Beverages 2022, 8, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galązka-Czarnecka, I.; E. Korzeniewska and A. Czarnecki. Influence of pulsed electric field on the content of polyphenolic compounds in wine. Korzeniewska and A. Czarnecki. Influence of pulsed electric field on the content of polyphenolic compounds in wine. PTZE 2018, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Puértolas, E.; G. Saldaña; S. Condón; I. Álvarez and J. Raso. A Comparison of the Effect of Macerating Enzymes and Pulsed Electric Fields Technology on Phenolic Content and Color of Red Wine. J. Food Sci. 2009, 74, C647–C652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.V.; R. Borgo; A. Guanziroli; J.M. Ricardo-da-Silva; M. Aguiar-Macedo and L.M. Redondo. Pilot Scale Continuous Pulsed Electric Fields Treatments for Vinification and Stabilization of Arinto and Moscatel Graúdo (Vitis vinifera L.) White Grape Varieties: Effects on Sensory and Physico-Chemical Quality of Wines. Beverages 2024, 10, 6. [Google Scholar]

- van Wyk, S.; F. V.M. Silva and M.M. Farid. Pulsed electric field treatment of red wine: Inactivation of Brettanomyces and potential hazard caused by metal ion dissolution. IFSET 2019, 52, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Casassa, L.F.; M. L. Fanzone and S.E. Sari. Comparative phenolic, chromatic, and sensory composition of five monovarietal wines processed with microwave technology. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-García, R.; M. C. Díaz-Maroto; M.A. Villena; M.S. Pérez-Coello and M.E. Alañón. Effect of Microwave Maceration and SO2 Free Vinification on Volatile Composition of Red Wines. LWT 2023, 179, 114597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J-F. ; T-T. Wang; Z-Y. Chen; D-H. Wong; M-G. Gong and P-Y. Li. Microwave irradiation: impacts on physicochemical properties of red wine. CYTA J. Food 2020, 18, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; H. J. Jung and J.H. Lee. Changes in the levels of headspace volatiles, including acetaldehyde and formaldehyde, in red and white wine following light irradiation. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, X.; G. Matinfar; R. Mandal; A. Singh; G. Fiutak; D.D. Kitts and A. Pratap Singh. Kinetics of anthocyanin condensation reaction in model wine solution under pulsed light treatment. Food Chem. 2023, 405, 134600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, X.; D. D. Kitts; A. Singh; A. Amiri; G. Matinfar and A. Pratap-Singh. Pulsed light treatment helps reduce sulfur dioxide required to preserve Malbec wines. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-López, A.J.; M. I. Rodríguez-López; F. Burló; Á.A. Carbonell-Barrachina; J.A. Gabaldón and V.M. Gómez-López. Evaluation of Pulsed Light to Inactivate Brettanomyces bruxellensis in White Wine and Assessment of Its Effects on Color and Aromatic Profile. Foods 2020, 9, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamera, A.; C. Escott; I. Loira; J.M. del Fresno; C. González and A. Morata. Pulsed Light: Challenges of a Non-Thermal Sanitation Technology in the Winemaking Industry. Beverages 2020, 6, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; L. Wang; H. Su; Y. Liang; P. Ji; X. Wang and Z. Xi. Effects of ultraviolet and infrared radiation absence or presence on the aroma volatile compounds in winegrape during veraison. Food Res. Int. 2023, 167, 112662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Y. Lee; J.-G. Lee and A.J. Buglass. Development of a simultaneous multiple solid-phase microextraction-single shot-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry method and application to aroma profile analysis of commercial coffee. J. Chromatogr. A 2013, 1295, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leffingwell. Odor detection thresholds. Available from: Leffingwell.com.

- García, M.; B. Esteve-Zarzoso; J. Crespo; J.M. Cabellos and T. Arroyo. Influence of Native Saccharomyces cerevisiae Strains from D.O. “Vinos de Madrid” in the Volatile Profile of White Wines. Ferment. 2019, 5, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.-Z.; P. -F. Gong; R.-R. Lu; B. Zhang; A. Morata and S.-Y. Han. Effect of Different Clarification Treatments on the Volatile Composition and Aromatic Attributes of ‘Italian Riesling’ Icewine. Mol. 2020, 25, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.C.; M. A. Sefton; D.K. Taylor and G.M. Elsey. An odour detection threshold determination of all four possible stereoisomers of oak lactone in a white and a red wine. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2006, 12, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero, A.; E. Campo; L. Fariña; J. Cacho and V. Ferreira. Analytical Characterization of the Aroma of Five Premium Red Wines. Insights into the Role of Odor Families and the Concept of Fruitiness of Wines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 4501–4510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáenz-Navajas, M.-P.; E. Campo; L. Culleré; P. Fernández-Zurbano; D. Valentin and V. Ferreira. Effects of the Nonvolatile Matrix on the Aroma Perception of Wine. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 5574–5585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsachaki, M.; A. -L. Gady; M. Kalopesas; R.S.T. Linforth; V. Athès; M. Marin and A.J. Taylor. Effect of Ethanol, Temperature, and Gas Flow Rate on Volatile Release from Aqueous Solutions under Dynamic Headspace Dilution Conditions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 5308–5315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsachaki, M.; R. S.T. Linforth and A.J. Taylor. Aroma Release from Wines under Dynamic Conditions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 6976–6981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, J.P.; K.G. Davis; T.H. Lilley and E. Haslam. The association of proteins with polyphenols. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1981, 309b-311.

- Soares, S.I.; R. M. Gonçalves; I. Fernandes; N. Mateus and V. de Freitas. Mechanistic Approach by Which Polysaccharides Inhibit α-Amylase/Procyanidin Aggregation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 4352–4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentová, H.; S. Skrovánková; Z. Panovská and J. Pokorný. Time–intensity studies of astringent taste. Food Chem. 2002, 78, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Retention time/mina | Semi-quantitative concentration/mg/Lb (SD, %RSD)c |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Treated | ||

| 2-Methyl-1-propanol (isobutyl alcohol) | 19.738 | 161 (42, 26) | 183 (66, 36) |

| 1-Butanol | 22.360 | 8 (1.8, 22) | 9 (4.3, 47) |

| 1-Pentanol | 24.889 | 24.5 (5.3, 22)# | 29.5 (6, 20)# |

| Ethyl hexanoate | 25.906 | 31.3 (6.5 20.8)* | 49.8 (3.5, 7)* |

| Ethyl octanoate | 35.257 | 173.3 (44, 25.4)* | 304.8 (43, 14)* |

| Acetic acid | 36.354 | 290 (85.8, 29) | 290.3 (119, 41) |

| Furfural | 37.084 | 30 (6.3, 21)# | 36 (5.3, 15)# |

| Vitispirane | 39.297 | 10 (2.5, 25) | 11.3 (1.3, 11) |

| 2,3-Butanediol | 40.079 | 183 (45.5, 25) | 162 (129.5, 80) |

| 1-Octanol | 40.546 | 20.5 (8, 39) | 17.8 (5.5, 31) |

| b-Caryophyllene | 42.059 | 21.8 (11.3, 52) | 12.8 (3, 24) |

| Ethyl decanoate | 43.721 | 175.3 (40.8, 23)* | 255 (21.6, 8.5)* |

| Menthol | 43.946 | 419 (79, 19)# | 287.3 (59.8, 21)# |

| g-Butyrolactone | 44.158 | 8.5 (2.5, 29) | 9 (11, 2.8) |

| Diethyl succinate | 45.462 | 541 (77, 14)# | 436 (54, 12.4)# |

| a-Terpineol | 46.242 | 19.8 (2, 10)# | 21.5 (1, 4.6)# |

| 1-Decanol (ISTD) | 49.482 | - | - |

| Methyl 2-hydroxybenzoate (salicylate) | 49.490 | 17 (0.1, 0.6)* | 20 (0.3, 1.5)* |

| p-anethole (p-propenylanisole) | 51.225 | 10 (2.4, 24) | 7.8 (0.8, 10) |

| Heptanoic acid | 51.628 | 29.3 (5, 17)# | 22 (2.3, 10.5)# |

| Butyl O-butyryllactate | 52.731 | 38 (21, 55) | 39.5 (8.3, 21) |

| Benzyl alcohol | 52.977 | 20.3 (0.7, 3.4)* | 15.3 (3.8, 25)* |

| Ethyl isopentyl succinate (Ethyl 3-methylbutyl succinate) | 53.666 | 14.8 (0.4, 2.7)* | 12.8 (0.9, 7)* |

| 2-Phenylethanol | 54.199 | 320.5 (20.8, 6.4)* | 243.5 (52.8, 21.7)* |

| 1-Dodecanol | 55.682 | 9.3 (0.7, 7.5) | 11.3 (1.9, 16.8) |

| Oak, Quercus or Whiskey lactone ( cis or trans-5-Butyl-4-methyl dihydro-2(3H)-furanone) | 55.964 | 7.3 (0.2, 2.7)* | 5.5 (1, 18)* |

| Octanoic acid | 59.149 | 87 (2.6, 3)# | 74.3 (19.3, 26)# |

| Decanoic acid | 70.564 | 39.3 (6.3, 16) | 41 (8.3, 20) |

| Compound (CAS reg, no.) | Increased ▲ or decreased ▼level on wave treatment* | Common aroma descriptors | OTV‡/mg/L (media) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethyl hexanoate (123-66-0) |

▲ | Apple, pineapple | 0.001 (in water)a; 0.014b |

| Ethyl octanoate (106-32-1) |

▲ | Orange, pineapple, brandy-like | 0.015 (in water)a; 0.24c |

| Ethyl decanoate (110-38-3) |

▲ | Fruity, oily, brandy-like | 0.001 (in water)a; 0.510 (in wine)a |

| Methyl salicylate (119-36-8) | ▲ | Fruity, root beer, mint | 0.04 (in water)a |

| Benzyl alcohol (100-51-6) |

▼ | Floral-rose, toasted | 10 (in water)a |

| Ethyl isopentyl succinate (28024-16-0) 2-Phenylethanol (60-12-8) |

▼ ▼ |

Fatty, pungent, fruity Rose, woody |

Unknown 0.75-1.1 (in water)a |

| Oak lactone (unknown isomer) 55013-32-6 (cis) or 39638-67-0 (trans) |

▼ | Coconut, woody$ | 0.024 (cis-isomer); 0.054 (trans-isomer) (both in wine)d |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).