Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

11 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample

2.2. Questionnaire Design

2.3. Data Collection and Processing

3. Results

3.1. Material Choice for Posterior Restorations

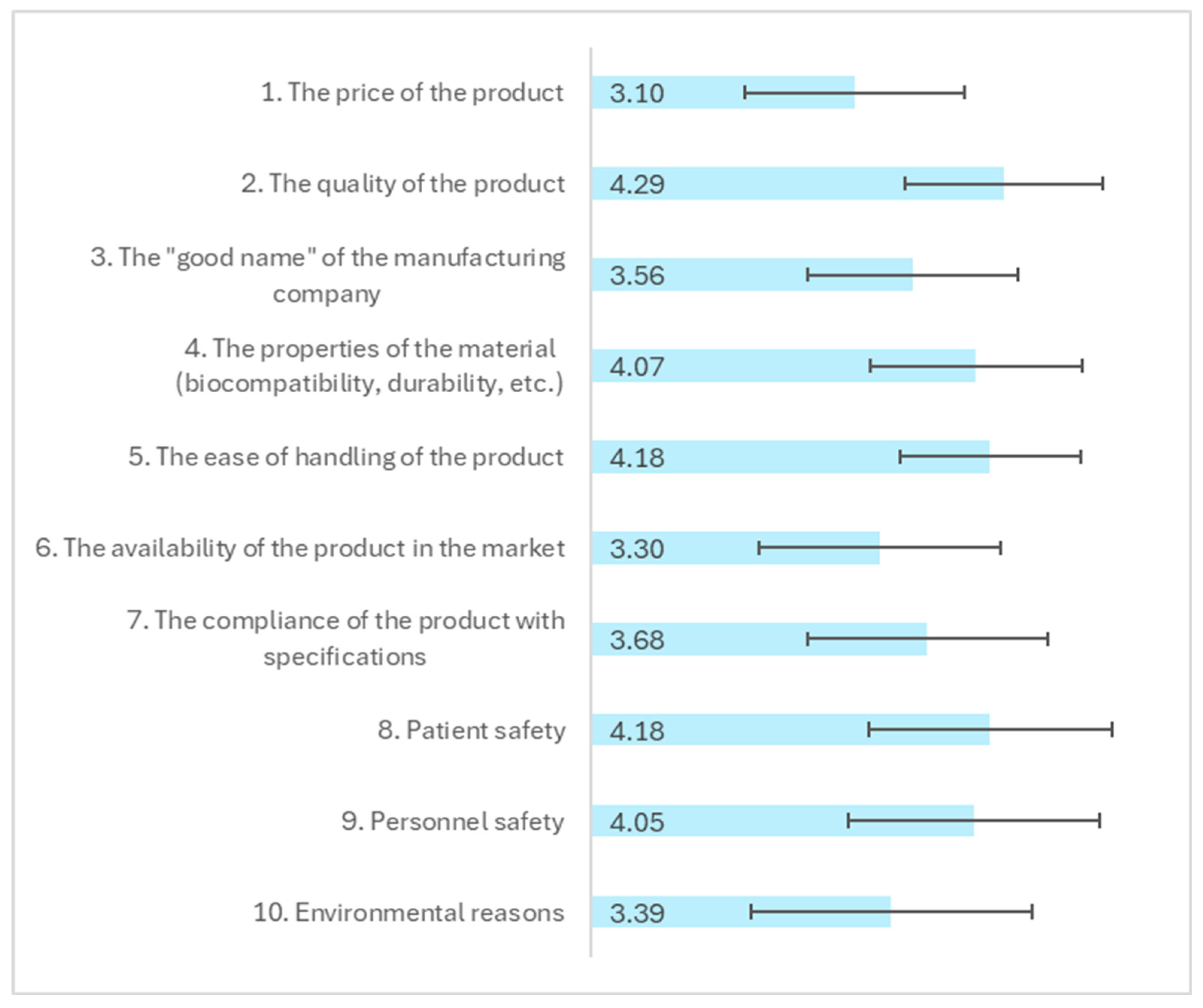

3.2. Selection of Restorative Materials Based on Clinical Properties

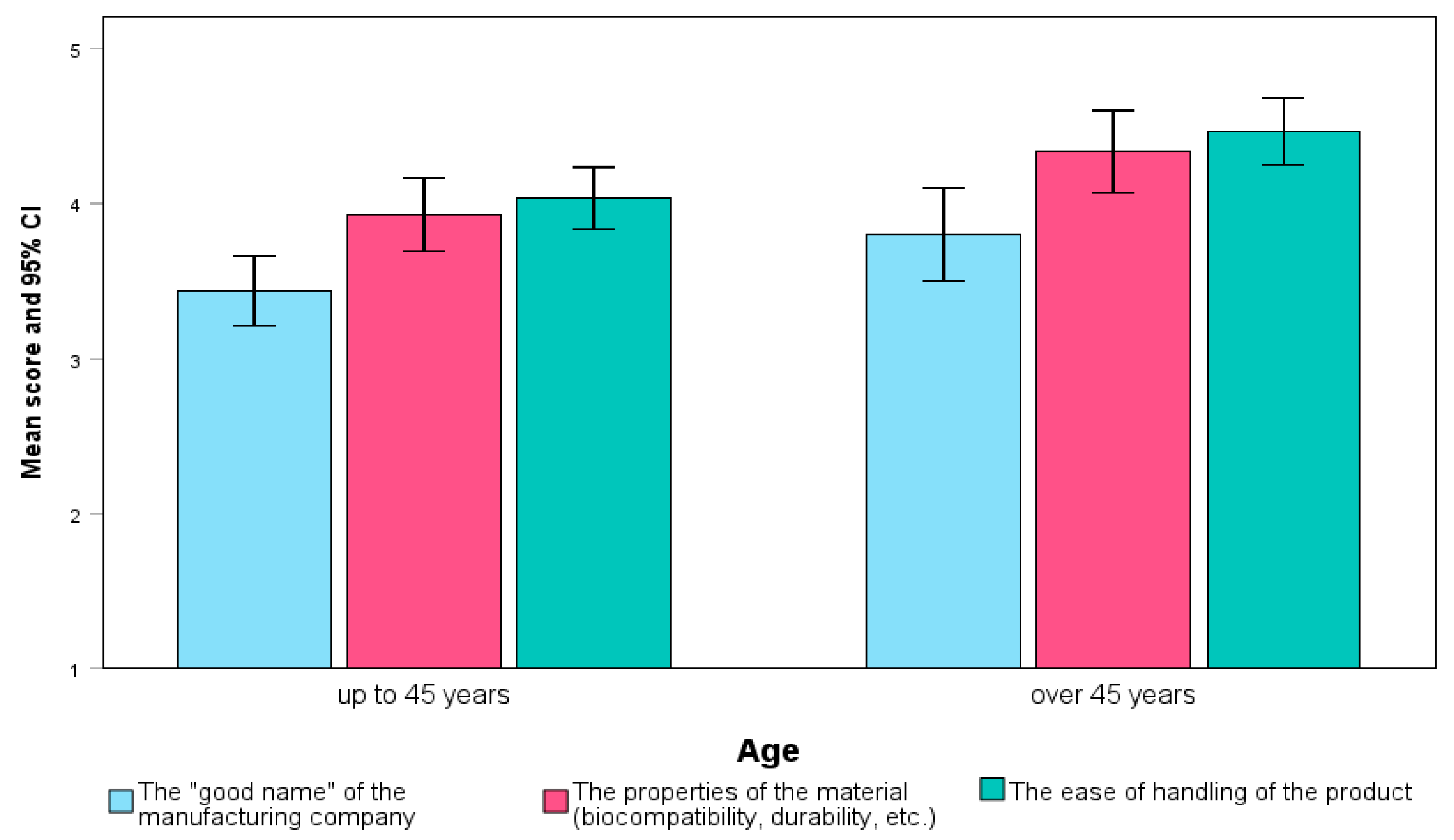

3.3. Impact of Professional Characteristics on Selection Priorities

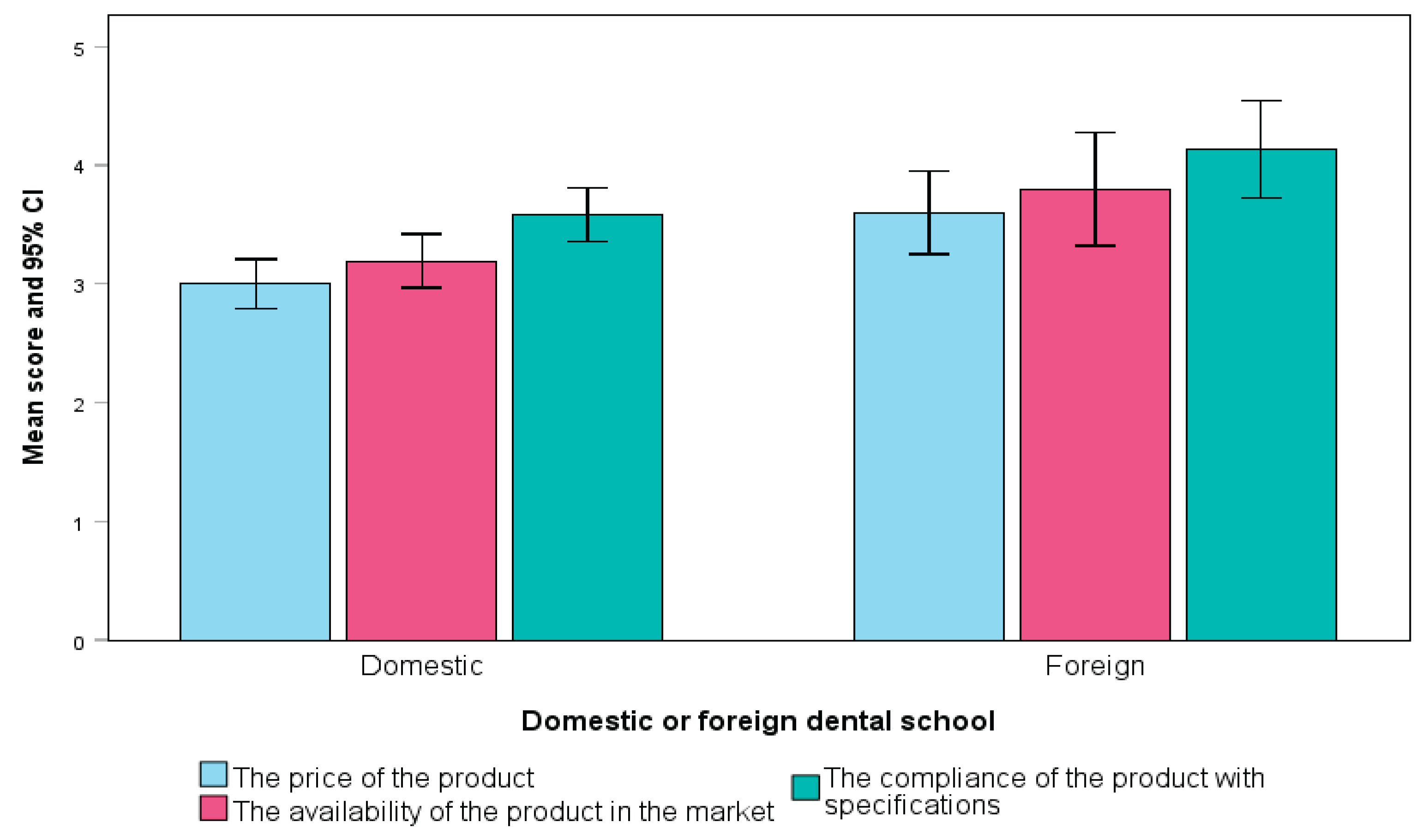

3.4. Influence of Educational Background on Selection Preferences

3.5. Gender-Based Differences in Material Selection Behavior

3.6. Influence of Professional Characteristics on Regulatory and Material Property Priorities

3.7. Influence of Packaging, Usability, and Patient Factors on Material Selection

3.8. Impact of COVID-19 on Material Purchasing Behavior

4. Discussion

4.1. Material Choice for Posterior Restorations

4.2. Selection of Restorative Materials Based on Clinical Properties

4.3. Impact of Professional Characteristics on Selection Priorities

4.4. Product Selection Influences and Environmental Considerations

4.5. Effects of COVID-19 on Purchasing Preferences

4.6. Study Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yadav R, Lee HH. Ranking and selection of dental restorative composite materials using FAHP-FTOPSIS technique: An application of multi criteria decision making technique. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials. 2022, 132:105298. [CrossRef]

- Aminoroaya A, Neisiany RE, Khorasani SN, Panahi P, Das O, Madry H, et al. A review of dental composites: Challenges, chemistry aspects, filler influences, and future insights. Composites Part B: Engineering. 2021, 216:108852. [CrossRef]

- Cho K, Rajan G, Farrar P, Prusty G. Dental resin composites: A review on materials to product realizations. Composites Part B: Engineering. 2021, 230:109495. [CrossRef]

- Ferracane JL, Hilton TJ, Stansbury JW, Watts DC, Silikas N, Ilie N, et al. Academy of Dental Materials guidance-Resin composites: Part II-Technique sensitivity (handling, polymerization, dimensional changes). Dent Mater. 2017, 33(11):1171–91.

- Chesterman J, Jowett A, Gallacher A, Nixon P. Bulk-fill resin-based composite restorative materials: A review. BDJ. 2017, 222:337–44. [CrossRef]

- Matos JD, Nakano LJ, Scalzer G, Bottino M, Vasconcelos J, Jesus R, et al. Characterization of Bulk-Fill Resin Composites in Terms of Physical, Chemical, Mechanical and Optical Properties and Clinical Behavior. Inter J Odontostomatol. 2021, 15:226–33.

- Pratap B, Gupta RK, Bhardwaj B, Nag M. Resin based restorative dental materials: characteristics and future perspectives. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2019, 55(1):126–38. [CrossRef]

- Sengupta A, Naka O, Mehta SB, Banerji S. The clinical performance of bulk-fill versus the incremental layered application of direct resin composite restorations: a systematic review. Evidence-based dentistry. 2023, 24(3):143. [CrossRef]

- Soni N, Bairwa S, Sumita S, Goyal N, Choudhary S, Gupta M, et al. Mechanical Properties of Dental Resin Composites: A Review. International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews. 2024, 5:7675–83. [CrossRef]

- Huang W, Ren L, Cheng Y, Xu M, Luo W, Zhan D, et al. Evaluation of the Color Stability, Water Sorption, and Solubility of Current Resin Composites. Materials. 2022, 15(19):6710. [CrossRef]

- Yap AU, Eweis AH, Yahya NA. Dynamic and Static Flexural Appraisal of Resin-based Composites: Comparison of the ISO and Mini-flexural Tests. Oper Dent. 2018, 43(5):E223–e31.

- Zhang N, Xie C. Polymerization shrinkage, shrinkage stress, and mechanical evaluation of novel prototype dental composite resin. Dental materials journal. 2020, 39(6):1064–71.

- Pizzolotto L, Moraes RR. Resin Composites in Posterior Teeth: Clinical Performance and Direct Restorative Techniques. Dentistry journal. 2022;10(12).

- Zaware PDN. Exploration of market potential towards dental material brands: An assessment with preferences of dentists in India. Available at SSRN 3819251. 2020.

- Lorenz J, Wilhelm C, Urich J, Weigl P, Sader R. Different Esthetic Assessment of Anterior Restorations by Patient and Expert: A Prospective Clinical Study. Journal of esthetic and restorative dentistry : official publication of the American Academy of Esthetic Dentistry [et al]. 2024.

- Scopes -ISO/TC 106 Dentistry Subcommittees 1 and 2. [Internet]. Available from: iso.org/files/live/sites/tc106/files/TC%20106%20and%20SC%20Scopes 2018-11-09.pdf.

- International Organization for Standardization G, Switzerland. ISO 4049:2019. Dentistry-Polymer-based restorative materials. 2019:29.

- Bhaskar AS, Khan A. Comparative analysis of hybrid MCDM methods in material selection for dental applications. Expert Syst Appl. 2022, 209(C):8.

- Demarco FF, Cenci MS, Montagner AF, de Lima VP, Correa MB, Moraes RR, et al. Longevity of composite restorations is definitely not only about materials. Dent Mater. 2023, 39(1):1–12.

- Barnes E, Bullock AD, Bailey SE, Cowpe JG, Karaharju-Suvanto T. A review of continuing professional development for dentists in Europe(*). European journal of dental education. 2013, 17 Suppl 1:5–17.

- Ghoneim A, Yu B, Lawrence H, Glogauer M, Shankardass K, Quiñonez C. What influences the clinical decision-making of dentists? A cross-sectional study. PloS one. 2020 15(6):e0233652.

- Nascimento GG, Correa MB, Opdam N, Demarco FF. Do clinical experience time and postgraduate training influence the choice of materials for posterior restorations? Results of a survey with Brazilian general dentists. Brazilian dental journal. 2013, 24(6):642–6.

- Mallinson DJ, Hatemi PK. The effects of information and social conformity on opinion change. PloS one. 2018;13(5):e0196600.

- Prudnikov Y, Nazarenko A. The role of content marketing in the promotion of medical goods and services. 2021.

- Al-Sbei R, Ataya J, Jamous I, Dashash M. The Impact of a Web-Based Restorative Dentistry Course on the Learning Outcomes of Dental Graduates: Pre-Experimental Study. JMIR formative research. 2024, 8:e51141.

- Anshasi RJ, Alsubahi N, Alhusein AA, Lutfi Khassawneh AA, Alrawad M, Alsyouf A. Evolving perspectives in dental marketing: A study of Jordanian dentists' attitudes towards advertising and practice promotion. Heliyon. 2025, 11(1):e41143.

- Bispo Júnior JP. Social desirability bias in qualitative health research. Revista de saude publica. 2022, 56:101.

- Burke FJ. The evidence base for 'own label' resin-based dental restoratives. Dent Update. 2013;40(1):5–6.

- Shaw K, Martins R, Hadis MA, Burke T, Palin W. 'Own-Label' Versus Branded Commercial Dental Resin Composite Materials: Mechanical And Physical Property Comparisons. Eur J Prosthodont Restor Dent. 2016, 24(3):122–9.

- Barakat B, Milhem M, Naji GM, Alzoraiki M, Muda HB, Ateeq A, et al. Assessing the Impact of Green Training on Sustainable Business Advantage: Exploring the Mediating Role of Green Supply Chain Practices. Sustainability [Internet]. 2023, 15(19).

- Ririn Y, Rahmat STY, Rina A. How packaging, product quality and promotion affect the purchase intention? Russian Journal of Agricultural and Socio-Economic Sciences. 2019;92(8):46–55.

- Rundh B. Linking packaging to marketing: how packaging is influencing the marketing strategy. British Food Journal. 2013, 115(11):1547–63.

- Antoniadou M, Chrysochoou G, Tzanetopoulos R, Riza E. Green Dental Environmentalism among Students and Dentists in Greece. Sustainability [Internet]. 2023, 15(12).

- Duane B, Ramasubbu D, Harford S, Steinbach I, Stancliffe R, Croasdale K, et al. Environmental sustainability and procurement: purchasing products for the dental setting. British dental journal. 2019, 226(6):453–8.

- Mulimani P. Green dentistry: the art and science of sustainable practice. British dental journal. 2017, 222(12):954–61.

- Beske-Janssen P, Johnsen T, Constant F, Wieland A. New competences enhancing Procurement’s contribution to innovation and sustainability. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management. 2023, 29(3):100847.

- Mittal R, Maheshwari R, Tripathi S, Pandey S. Eco-friendly dentistry: Preventing pollution to promoting sustainability. Indian Journal of Dental Sciences. 2020, 12:251.

- Ogiemwonyi O, Alam M, Alshareef R, Alsolamy M, Azizan N, Mat N. Environmental factors affecting green purchase behaviors of the consumers: Mediating role of environmental attitude. Cleaner Environmental Systems. 2023, 100130.

- Țâncu AMC, Imre M, Iosif L, Pițuru SM, Pantea M, Sfeatcu R, et al. Is Sustainability Part of the Drill? Examining Knowledge and Awareness Among Dental Students in Bucharest, Romania. Dentistry journal. 2025, 13(3).

- Farrokhi F, Farrokhi F, Mohebbi SZ, Khami MR. A scoping review of the impact of COVID-19 on dentistry: financial aspects. BMC Oral Health. 2024, 24(1):945.

- Rey-Martínez MS, Rey-Martínez MH, Martínez-Rodríguez N, Meniz-García C, Suárez-Quintanilla JM. Influence of the Sanitary, Economic, and Social Crisis of COVID-19 on the Emotional State of Dentistry in Galicia (Spain). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023, 20(4).

- Al-Asmar AA, Al-Hiyasat AS, Abu-Awwad M, Mousa HN, Salim NA, Almadani W, et al. Reframing Perceptions in Restorative Dentistry: Evidence-Based Dentistry and Clinical Decision-Making. International journal of dentistry. 2021, 2021:4871385.

- Maier C, Thatcher J, Grover V, Dwivedi Y. Cross-sectional research: A critical perspective, use cases, and recommendations for IS research. International Journal of Information Management. 2023;70:102625.

- Klaiman K, Ortega D, Garnache C. Consumer preferences and demand for packaging material and recyclability. Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 2016;115.

- Veleva S, Tsvetanova A. Characteristics of the digital marketing advantages and disadvantages. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 2020, 940:012065.

- Ranganathan P, Caduff C. Designing and validating a research questionnaire - Part 1. Perspectives in clinical research. 2023, 14(3):152–5.

- Khanal B, Chhetri D. A Pilot Study Approach to Assessing the Reliability and Validity of Relevancy and Efficacy Survey Scale. Janabhawana Research Journal. 2024, 3:35–49.

- Brewster J, Roberts HW. 12-Month flexural mechanical properties of conventional and self-adhesive flowable resin composite materials. Dental materials journal. 2023, 42(4):598–609.

- Calabrese L, Fabiano F, Bonaccorsi LM, Fabiano V, Borsellino C. Evaluation of the Clinical Impact of ISO 4049 in Comparison with Miniflexural Test on Mechanical Performances of Resin Based Composite. International journal of biomaterials. 2015, 2015:149798.

- Erickson RL, Barkmeier WW. Comparisons of ISO depth of cure for a resin composite in stainless-steel and natural-tooth molds. European journal of oral sciences. 2019, 127(6):556–63.

- Fan PL, Schumacher RM, Azzolin K, Geary R, Eichmiller FC. Curing-light intensity and depth of cure of resin-based composites tested according to international standards. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939). 2002;133(4):429–34; quiz 91–3.

- Flury S, Hayoz S, Peutzfeldt A, Hüsler J, Lussi A. Depth of cure of resin composites: is the ISO 4049 method suitable for bulk fill materials? Dent Mater. 2012, 28(5):521–8.

- Heintze S, Zimmerli B. Relevance of in-vitro tests of adhesive and composite dental materials. A review in 3 parts. Part 2: non-standardized tests of composite materials. Schweizer Monatsschrift für Zahnmedizin = Revue mensuelle suisse d'odonto-stomatologie = Rivista mensile svizzera di odontologia e stomatologia / SSO. 2011, 121:916–30.

- Heintze SD, Zimmerli B. Relevance of in vitro tests of adhesive and composite dental materials, a review in 3 parts. Part 1: Approval requirements and standardized testing of composite materials according to ISO specifications. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed. 2011, 121(9):804–16.

- Ilie N. ISO 4049 versus NIST 4877: Influence of stress configuration on the outcome of a three-point bending test in resin-based dental materials and interrelation between standards. Journal of dentistry. 2021;110:103682.

- Moore BK, Platt JA, Borges G, Chu TM, Katsilieri I. Depth of cure of dental resin composites: ISO 4049 depth and microhardness of types of materials and shades. Oper Dent. 2008, 33(4):408–12.

- Arandi NZ. Current trends in placing posterior composite restorations: Perspectives from Palestinian general dentists: A questionnair study. Journal of International Society of Preventive & Community Dentistry. 2024, 14(2):112–20.

- Ilie N, Hilton TJ, Heintze SD, Hickel R, Watts DC, Silikas N, et al. Academy of Dental Materials guidance-Resin composites: Part I-Mechanical properties. Dent Mater. 2017, 33(8):880–94.

- Megremis SJ. Assuring the Safety of Dental Materials: The Usefulness and Application of Standards. Dental clinics of North America. 2022, 66(4):673–89.

- Bujang MA, Omar E, Foo D, Hon YK. Sample size determination for conducting a pilot study to assess reliability of a questionnaire. Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics. 2024, 49.

- Hussey I, Alsalti T, Bosco F, Elson M, Arslan R. An Aberrant Abundance of Cronbach’s Alpha Values at .70. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science. 2025, 8(1):25152459241287123.

- Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making Sense of Cronbach's Alpha. Inter J Med Educ. 2011, 2:53–5.

- Agrawal AA, Prakash N, Almagbol M, Alobaid M, Alqarni A, Altamni H. Synoptic review on existing and potential sources for bias in dental research methodology with methods on their prevention and remedies. World J Methodology. 2023, 13(5):426–38.

- Vaidyanathan AK. Controlling bias in research. Journal of Indian Prosthodontic Society. 2022, 22(4):311–3.

- Latkin CA, Edwards C, Davey-Rothwell MA, Tobin KE. The relationship between social desirability bias and self-reports of health, substance use, and social network factors among urban substance users in Baltimore, Maryland. Addictive behaviors. 2017, 73:133–6.

- Guo M, Wang Y, Yang Q, Li R, Zhao Y, Li C, et al. Normal Workflow and Key Strategies for Data Cleaning Toward Real-World Data: Viewpoint. Interactive journal of medical research. 2023, 12:e44310.

- Ranganathan P, Hunsberger S. Handling missing data in research. Perspectives in clinical research. 2024, 15(2):99–101.

- Ahmed I, Ishtiaq S. Reliability and validity: Importance in Medical Research. JPMA The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 2021, 71(10):2401–6.

- Patino CM, Ferreira JC. Inclusion and exclusion criteria in research studies: definitions and why they matter. Jornal brasileiro de pneumologia : publicacao oficial da Sociedade Brasileira de Pneumologia e Tisilogia. 2018, 44(2):84.

- Torgerson DJ, Torgerson CJ. Pilot Randomised Controlled Trials. In: Torgerson DJ, Torgerson CJ, editors. Designing Randomised Trials in Health, Education and the Social Sciences: An Introduction. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK; 2008. p. 119–26.

- Leon AC, Davis LL, Kraemer HC. The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. J Psychiatric Res. 2011, 45(5):626–9.

- Thabane L, Ma J, Chu R, Cheng J, Ismaila A, Rios LP, et al. A tutorial on pilot studies: the what, why and how. BMC Medical Res Methodol. 2010, 10(1):1.

- Hallingberg B, Turley R, Segrott J, Wight D, Craig P, Moore L, et al. Exploratory studies to decide whether and how to proceed with full-scale evaluations of public health interventions: a systematic review of guidance. Pilot and Feasibility Studies. 2018, 4(1):104. [CrossRef]

- Bornstein M, Al-Nawas B, Kuchler U, Tahmaseb A. Consensus Statements and Recommended Clinical Procedures Regarding Contemporary Surgical and Radiographic Techniques in Implant Dentistry. Inter J oral Maxillofacial Implants. 2014, 29:78–82. [CrossRef]

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Would you choose a product with increased water absorption for aesthetic restorations because it is: | ||

| Lower cost | 3 | 3.4% |

| Trusted brand name | 16 | 18.4% |

| With greater ease of handling | 23 | 26.4% |

| With long-term storage of the material | 9 | 10.3% |

| The most important thing for me is that the material complies with ISO specifications | 42 | 48.3% |

| I don't know/don't answer | 23 | 26.4% |

| Would you choose a resin material that has lower flexural strength (i.e., has a lower ability to resist deformation under applied forces) but: | ||

| Has greater color stability | 14 | 16.1% |

| Requires shorter polymerization time and therefore less working time | 8 | 9.2% |

| Has greater radiopacity than dentin and is easier to see on X-rays | 2 | 2.3% |

| I do not consider flexural strength important | 2 | 2.3% |

| I would not choose a material that is inferior in this property for posterior teeth | 52 | 59.8% |

| I would not choose a material that is inferior in physical and mechanical properties | 47 | 54.0% |

| I do not know/do not answer | 5 | 5.7% |

| Total$$(M, SD) | Male$$(M, SD) | Female$$(M, SD) | Mann-Whitney p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For conservative aesthetic restorations with composite resin: | |||||||

| 1. I like to try new materials frequently to see which one works best. | 3.06 | 1.03 | 3.10 | .97 | 3.02 | 1.08 | 0.827 |

| 2. I look for published studies on efficacy and longevity before trying a new material. | 2.86 | 1.15 | 2.69 | 1.26 | 3.00 | 1.05 | 0.254 |

| 3. I look for material to have a long history of clinical success before adopting it into my practice. | 3.54 | 1.03 | 3.28 | 1.00 | 3.75 | 1.02 | 0.027 |

| 4. I rarely try new aesthetic materials. | 2.47 | 1.05 | 2.23 | .90 | 2.67 | 1.14 | 0.089 |

| 5. I am interested in trying new generations of materials I already trust. | 3.59 | .96 | 3.54 | .91 | 3.63 | 1.00 | 0.631 |

| 6. I rarely change the aesthetic resin materials I use unless they are no longer available on the market. | 2.72 | 1.18 | 2.72 | 1.02 | 2.73 | 1.30 | 0.888 |

| 7. I trust the resin materials I learned to use in school during my studies. | 2.08 | 1.11 | 2.00 | .95 | 2.15 | 1.24 | 0.826 |

| 8. I generally trust the one that provides the longest working time. | 2.49 | 1.07 | 2.41 | 1.02 | 2.56 | 1.11 | 0.550 |

| 9. I trust the resin materials that I often hear colleagues speak positively about. | 3.16 | 1.10 | 3.03 | 1.04 | 3.27 | 1.14 | 0.235 |

| 10. I trust the material whose printed advertising has convinced me. | 1.93 | .95 | 1.67 | .70 | 2.15 | 1.07 | 0.038 |

| 11. I trust the material whose advertising in digital media has convinced me. | 1.93 | .94 | 1.67 | .74 | 2.15 | 1.03 | 0.027 |

| 12. I have not observed any conscious behavior on my part when choosing aesthetic materials for immediate restorations. | 2.33 | 1.12 | 2.21 | .98 | 2.44 | 1.22 | 0.487 |

| Seeking information before purchasing resin restorative material | |||||||

| 1. The ISO specifications that it must include. | 3.02 | 1.07 | 3.05 | 1.19 | 3.00 | .97 | .712 |

| 2. The opinion of a trusted partner/colleague regarding the product. | 3.25 | .88 | 3.18 | .88 | 3.31 | .88 | .476 |

| 3. Any discount offer that my supplier may have. | 2.74 | .98 | 2.64 | .93 | 2.81 | 1.02 | .610 |

| 4. The lifespan of the material. | 3.22 | .97 | 3.08 | .90 | 3.33 | 1.02 | .269 |

| 5. The carbon footprint it leaves in the environment. | 2.22 | 1.03 | 1.82 | .97 | 2.54 | .97 | <.001 |

| 6. The longevity of clinical restorations with this material. | 4.22 | .97 | 4.10 | .97 | 4.31 | .97 | .194 |

| Gender (Female vs Male) | Age (over 45 years) | Dental school (foreign vs domestic) | Post-grad studies in dentistry | Clinical experience (over 5 years) | Employment (private clinic vs other) | Purchasing resin restorations over 2 times/year | Not responsible for supply of resin restorations | Performing over 20 restorations/ week | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Would you choose a product with increased water absorption for aesthetic restorations because it is: | |||||||||

| Lower cost | 0.044 | 0.128 | -0.086 | 0.112 | 0.065 | -0.083 | 0.009 | 0.146 | -0.011 |

| Trusted brand name | -0.049 | .217* | 0.019 | 0.179 | 0.124 | -0.049 | 0.066 | 0.066 | -0.138 |

| With greater ease of handling | -0.141 | -0.106 | 0.209 | 0.015 | -0.071 | -0.036 | 0.049 | -0.008 | 0.060 |

| With long-term storage of the material | .230* | 0.071 | -0.055 | 0.123 | -0.034 | 0.003 | -0.065 | -0.065 | 0.094 |

| The most important thing for me is that the material complies with ISO specifications | 0.085 | -0.072 | -0.076 | 0.145 | 0.011 | -0.100 | 0.197 | -0.201 | -0.009 |

| Would you choose a resin material that has lower flexural strength (i.e., has a lower ability to resist deformation under applied forces) but: | |||||||||

| Has greater color stability | -0.171 | -0.120 | -0.117 | 0.109 | -0.058 | -0.046 | -0.091 | .247* | -0.117 |

| Requires shorter polymerization time and therefore less working time | -0.033 | -0.063 | 0.171 | -0.003 | 0.083 | -0.033 | -0.127 | -0.042 | 0.094 |

| It has greater radiopacity than dentin and is easier to see on X-rays | -0.016 | -0.111 | -0.070 | 0.038 | 0.002 | -0.016 | -0.103 | -0.103 | 0.045 |

| I do not consider flexural strength important | 0.138 | .211* | -0.070 | 0.038 | 0.155 | 0.138 | 0.063 | -0.103 | 0.045 |

| I would not choose a material that is inferior to this property for posterior teeth | 0.109 | -0.046 | 0.126 | 0.013 | -0.080 | 0.015 | -0.007 | -0.007 | -0.004 |

| I would not choose a material that is inferior in physical and mechanical properties | 0.050 | -0.010 | 0.055 | -0.039 | 0.036 | 0.050 | 0.120 | -0.029 | .306** |

| Total$$(M, SD) | Male$$(M, SD) | Female$$(M, SD) | Mann-Whitney p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For conservative aesthetic restorations with composite resin: | |||||||

| 1. The appearance of the product packaging. | 1.38 | .74 | 1.26 | .59 | 1.48 | .82 | 0.203 |

| 2. The environmental footprint of the packaging. | 2.14 | 1.00 | 1.74 | .97 | 2.46 | .92 | <.001 |

| 3. The increased advertising and promotional activities that have been carried out. | 1.74 | .87 | 1.46 | .64 | 1.96 | .97 | 0.005 |

| 4. Its ease of supply. | 2.69 | 1.04 | 2.64 | 1.06 | 2.73 | 1.03 | 0.446 |

| 5. The volume of packaging materials (waste). | 2.09 | 1.01 | 1.79 | .98 | 2.33 | .97 | 0.006 |

| 6. Its compliance with specifications. | 3.70 | 1.16 | 3.69 | 1.13 | 3.71 | 1.20 | 0.869 |

| Factors influencing resin restorative material selection | |||||||

| 1. The visual appeal of the packaging | 1.75 | .87 | 1.46 | .72 | 1.98 | .91 | 0.003 |

| 2. The practical and easy way of dosing | 2.90 | .99 | 2.82 | .91 | 2.96 | 1.05 | 0.577 |

| 3. The simple design of the packaging | 2.53 | 1.08 | 2.33 | 1.08 | 2.69 | 1.06 | 0.155 |

| 4. Detailed instructions for use | 3.29 | 1.00 | 3.38 | 1.04 | 3.21 | .97 | 0.446 |

| 5. The reduced time to learn the application technique | 3.44 | 1.00 | 3.38 | .99 | 3.48 | 1.01 | 0.545 |

| 6. The reduced time to apply it clinically | 3.49 | .95 | 3.54 | .91 | 3.46 | .99 | 0.837 |

| 7. The simple application technique | 3.70 | .90 | 3.74 | .82 | 3.67 | .97 | 0.885 |

| 8. The wide range of applications of the material | 3.77 | .92 | 3.72 | .89 | 3.81 | .96 | 0.464 |

| 9. The long shelf life of the packaging | 3.43 | 1.04 | 3.41 | 1.09 | 3.44 | 1.01 | 0.862 |

| 10. Its storage in non-specific conditions | 3.18 | 1.08 | 3.13 | 1.10 | 3.23 | 1.08 | 0.546 |

| 11. Its compatibility with different adhesive systems or techniques | 3.87 | .90 | 4.03 | .81 | 3.75 | .96 | 0.189 |

| 12. Its price | 3.55 | .94 | 3.49 | .97 | 3.60 | .92 | 0.655 |

| 13. The patient's preferences | 2.37 | 1.13 | 2.33 | 1.08 | 2.40 | 1.18 | 0.849 |

| 14. The patient's medical history | 3.03 | 1.14 | 3.08 | 1.13 | 3.00 | 1.15 | 0.808 |

| 15. The patient's age | 2.86 | 1.17 | 2.82 | 1.12 | 2.90 | 1.22 | 0.694 |

| 16. The patient's financial situation | 2.71 | 1.19 | 2.85 | 1.18 | 2.60 | 1.20 | 0.330 |

| Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the approach to resin restorative materials | Total sample (N = 87) |

Clinical experience (in years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| up to 5 years (N = 44) |

over 5 years (N = 43) |

|||||

| Ν | % | Ν | % | Ν | % | |

| My orders for resin restorative materials have increased | 10 | 11.5% | 3 | 6.8% | 7 | 16.3% |

| My orders for restorative resin materials have decreased | 4 | 4.6% | 2 | 4.5% | 2 | 4.7% |

| My interest in purchasing materials with an easy and fast workflow has increased | 17 | 19.5% | 4 | 9.1% | 13 | 30.2% |

| My interest in trying new materials has increased | 22 | 25.3% | 7 | 15.9% | 15 | 34.9% |

| My interest in trying new materials has decreased | 3 | 3.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 7.0% |

| There has been no significant change in my preferences | 36 | 41.4% | 17 | 38.6% | 19 | 44.2% |

| I don't know / no answer | 18 | 20.7% | 16 | 36.4% | 2 | 4.7% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).