1. Introduction

Pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB) management in Nigeria faces significant challenges, including low treatment success rates and issues with patient adherence to therapy. The country ranks among the countries with the highest burden of tuberculosis globally [

1]. According to World Health Organization (WHO), Nigeria has a significant number of new TB cases each year, which poses a public health challenge.

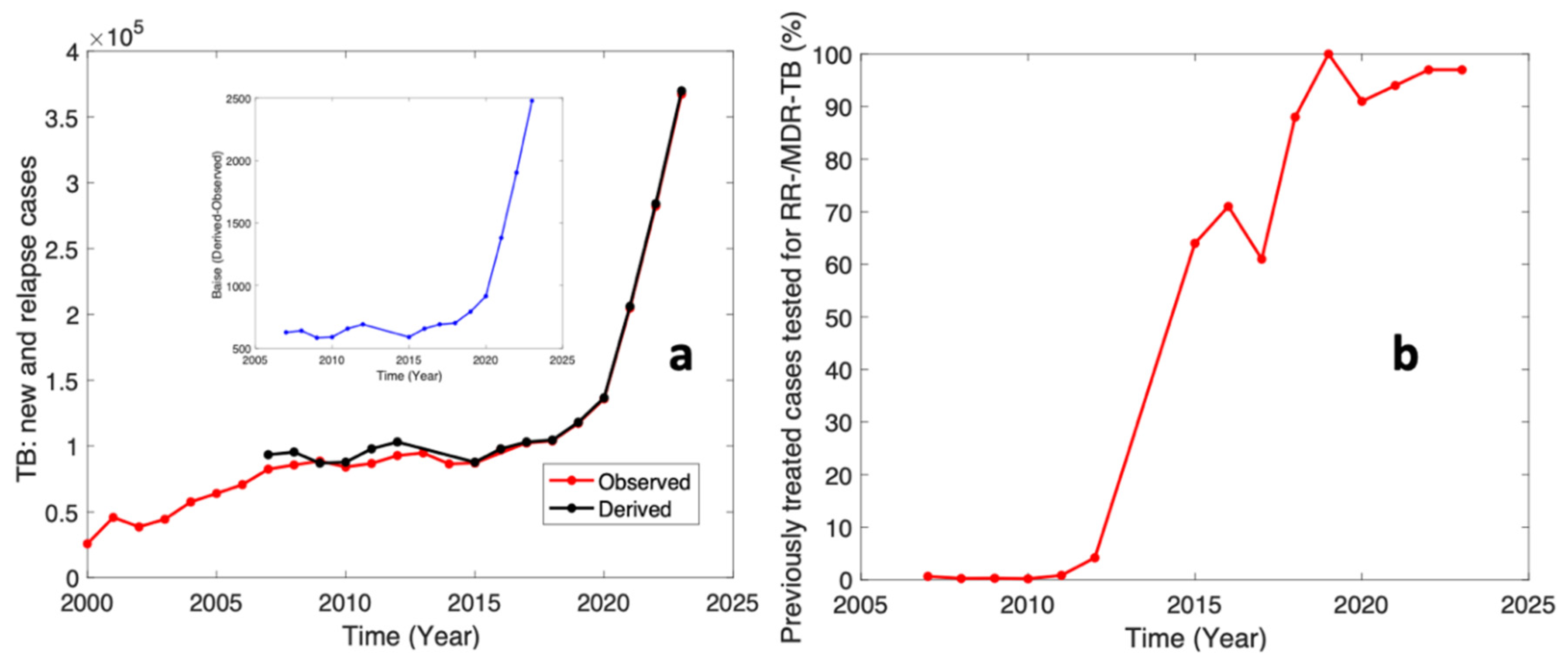

Figure 1 below presents the analysis of the WHO tuberculosis in Nigeria.

Figure 1a presents the cases of new or relapsed tuberculosis. The observed data in

Figure 1a refers to the raw data obtained in the WHO datasets [

2] while the derived data was calculated from the dataset for relapsed cases of tuberculosis that was gotten from the WHO dataset [

3] i.e., previously treated cases tested for RR-/MDR-TB (%). The inset graph in

Figure 1a presents the biases i.e., the difference between the derived and observed datasets. These biases could also refer to new cases on a yearly basis. This analysis shows that new PTB cases are at a maximum of 2500 in 2023 and a relapse of over 10,000 PTB patients.

Figure 1b shows the previously treated cases tested for RR-/MDR-TB (%) as seen in the WHO dataset [

3]. This graph shows that the efforts for treating PTB are commendable; however, the new and relapsed cases call for a purposeful action.

Many patients face barriers to adhering to their TB treatment regimens. Factors such as poverty, lack of transportation to health facilities, and inadequate health education contribute to poor adherence rates. This is particularly pronounced in rural areas where access to healthcare services is limited. Socioeconomic conditions in Nigeria, including high unemployment rates and limited access to healthcare resources, exacerbate the challenges of managing PTB. Patients may prioritize immediate economic needs over their health, leading to inconsistent medication intake.

In the management of pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB), the sputum smear test is often used for diagnosis and monitoring of response to treatment [

4]. Sputum smear conversion is one of the therapeutic goals for PTB after the intensive phase of anti-TB therapy [

5]. This term is used when the sputum of new smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis (SPPTB) patients has turned negative after receiving extensive anti-TB therapy [

6]. Treatment failure and recurrence are strongly predicted by smear conversion, an important indication of TB care effectiveness [

7].

Sputum conversion remains useful in tracking and evaluating the efficacy of TB medications for the lungs [

8]. Therefore, a patient’s smear sputum test negative shows that they are not contagious. However, if after two months of therapy, a patient’s sputum conversion has failed, the intense phase will be prolonged by one month [

9]. If conversion does not occur after this, the patient is more likely to have developed drug resistance [

10].

A significant percentage of PTB patients remain bacteriologically positive after taking medications in the intensive phase of therapy, despite the expectation that most TB cases would turn smear-negative [

11]. One major factor facilitating sputum smear conversion is good drug adherence [

12]. Despite the adoption of the directly observed therapy short course (DOTs), the rate of failure of sputum conversion has not decreased. The traditional directly observed therapy (DOT) model has limitations in Nigeria, especially in remote regions where patients may not readily be able to access care [

13,

14]. The introduction of telemedicine, specifically ViDOT, can bridge this gap by providing real-time monitoring and support to patients, ensuring they adhere to their treatment plans.

Telemedicine can leverage mobile technology to facilitate communication between healthcare providers and patients. In Nigeria, where mobile phone usage is high, ViDOT can be an effective tool for enhancing patient engagement, providing reminders for medication, and offering educational resources about TB [

13]. Therefore, there is a need to intensify the supervision and the monitoring process especially when these patients are far away from their healthcare providers [

15]. We sought to incorporate telemedicine which has demonstrated improved patient-provider health communication more efficiently [

16], leveraging its wide range of health communication advantages through apps including reduced expenses, increased patient convenience, security, and patients’ satisfaction, as well as digitization of health communication through Web-based services [

17].

Given the unique challenges faced in the Nigerian context in terms of patients’ accessibility to healthcare services, this study is essential in assessing the effectiveness of ViDOT in improving treatment outcomes for PTB patients. Based on the identified issues of new and relapsed cases in the treatment of PTB as seen in the WHO reports on PTB treatment in Nigeria, this study aims to investigate the impact of intensive home monitoring of anti-TB drug adherence on sputum conversion using video directly observed therapy (ViDOT) in resource constrained society like Nigeria [

18,

19]. It aims to provide evidence-based recommendations that can inform policy and practice, ultimately contributing to the reduction of TB burden in Nigeria.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

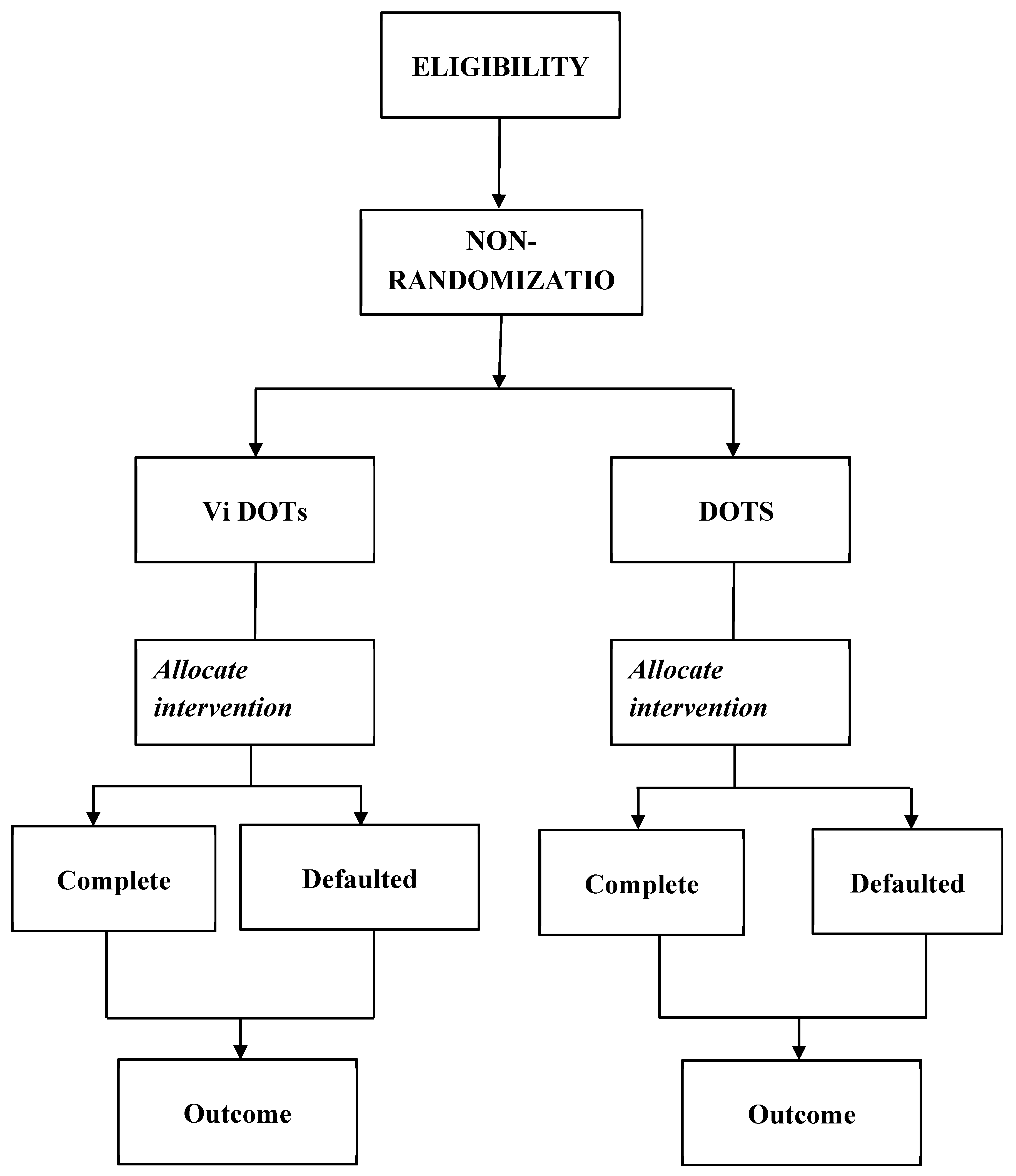

This study utilized a Clinical-Control Trial (CCT) involving 150 patients with pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB), who were assigned to either video-directly observed therapy (ViDOT) or standard directly observed therapy (DOT) in a 1:1 ratio. The outcome variables were assessed at the conclusion of the trial, as depicted in

Figure 2. Participants were consecutively recruited, and the assignment was non-randomized. To prevent contamination, the control group remained unaware of the study and did not have access to the monitoring app.

2.2. Study Setting

The study was conducted in two teaching hospitals located in Ekiti State: Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital in Ado-Ekiti, the state capital, and Federal Teaching Hospital in Ido-Ekiti, a peri-urban area within the state. Both facilities are tertiary hospitals equipped with tuberculosis (TB) referral services and provide comprehensive care for patients with TB.

2.3. Study Population

The inclusion criteria for the study required that participants be adults with a confirmed diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB) who are attending the DOTS clinic. Additionally, participants must possess a smart mobile phone and reside in an area with mobile network coverage. It was also necessary for participants to be cognitively sound and to provide informed consent to participate in the study.

The exclusion criteria for the study included individuals who do not have access to a smart mobile phone, individuals who lack sufficient literacy to operate a smart mobile phone and those who are unwilling to participate.

2.4. Sampling Procedure

A purposive sampling technique was employed in this study. This non-random sampling method is designed to select participants with specific characteristics from an accessible pool of respondents. Given the technological aspect of the study, it was essential that participants were technology-compliant, meaning they must own and be proficient in using an Android or iOS device. Additionally, the compatibility of these devices with the telemedicine application (miT-DOT) was a key consideration in the selection process. The sample was drawn from tuberculosis referral healthcare centers located in Ekiti State.

2.5. Data Collection Instrument

The Case Report Form (CRF) and questionnaire were the major instruments for data collection. Case report form was administered to the patients each time they used their drug; this was used to determine the level of adherence and compliance with the DOTs.

2.6. ViDOT Mobile Application

ViDOT is a mobile application developed by Emocha for monitoring tuberculosis medication adherence and reporting compliance to healthcare practitioners. For the purposes of this study, the app was reconfigured and adapted with the assistance of an ICT specialist. The app’s significance is immense, as it enables healthcare providers to know precisely when their patients have taken their medication. Patients diagnosed with tuberculosis are typically required to take their medication once a week for an average duration of three to nine months.

The ViDOT smartphone app exemplifies the various tools available to healthcare practitioners for maintaining continuous communication with patients through text and video. It operates using both synchronous and asynchronous methods, allowing healthcare providers to observe patients as they take their medications. Recorded videos can be replayed to confirm the timing of medication intake. Additionally, the app sends reminder messages to patients about when to take their medications. Patients can also use the app’s video functionality to record themselves while taking their medication, which can later be reviewed by their healthcare provider. This enables healthcare practitioners to track their patients’ progress based on the information provided through the app.

2.7. The Clinical Trial Procedure

2.7.1. Pre-Treatment Stage

At this stage, the researcher visited the healthcare facilities to ascertain the eligibility of the patients who were used in the study. Individual patients who received TB care at a hospital where they gave their therapy were the control group. The TB healthcare practitioners in the healthcare facilities serve as the research assistants for the study; they became members of the research team.

The healthcare practitioners who served as research assistants received training from the assigned authors on how to utilize the data collection instrument (CRF) for the study. These research assistants were responsible for recording data while administering both the DOTS and Telemedicine DOT to the participants. Additionally, patients in the experimental group were thoroughly educated on the proper use of their medications and what was expected of them during treatment. They were also instructed on how to use the ViDOT mobile application on their smartphones for the study. The research team regularly enrolled patients and invited all eligible individuals to participate. At each location, the team promoted the study to new patients as they registered for treatment. After assessing a patient’s eligibility, the research assistant explained the study in person and addressed any questions the patient had. Interested patients were required to provide informed consent before completing a baseline survey that included questions about their socio-demographics, behaviors, self-management practices, and understanding of tuberculosis (TB). All participants received standard TB education, which covered information on TB treatment, potential side effects, and the importance of adhering to the treatment regimen. Following this, participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups. This enrollment phase lasted for one month.

2.7.2. Treatment Stage

Patients were followed up throughout the duration of their therapy, which lasted six months, during which observations were made to compare the effectiveness of the telemedicine DOT intervention with standard DOTS. A 6-month treatment regimen for drug-susceptible tuberculosis (TB) consists of a 2-month intensive phase that involves the use of four medications: rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. This is followed by a 4-month continuation phase during which isoniazid and rifampicin are administered daily. When available, these medications are provided in the form of three or four-drug combinations.

During the treatment phase, the control group received conventional treatment through directly observed therapy (DOTS), where self-administration of medication was the standard practice at the study sites. Patients were provided with a 1 to 2-month supply of medication and were expected to return for monthly follow-up sessions, or sooner if they encountered any issues with their treatment. Routine visits for patients in the control group were conducted in accordance with the National Tuberculosis Program (NTP) recommendations. The study team documented all follow-up visits and procedures.

During the treatment phase, the group was supported and monitored through the viDOT mobile application, which utilized text messages and live video charts. The application facilitated several key functions: it provided patients with information about tuberculosis and its treatment through weekly textual and video communications aimed at educating them throughout their treatment. Additionally, it enabled the monitoring of treatment progress through daily self-reporting and direct metabolite testing, aligned with a treatment calendar and progress indicators. Patients could report any potential adverse effects of therapy, which would prompt follow-up contact from a treatment supporter for further evaluation. The app also allowed for communication via text messaging with a treatment supporter, enabling patients to ask questions and address any issues they encountered. Furthermore, it sent reminders for medication intake and upcoming appointments. Weekly live video interactive sessions were also conducted to enhance patient engagement and support.

The textual, pictorial, and video messages were sent on a broadcast. Messages to remind the patients about drug usage will prompt the patients to respond with “DONE” after taking their drug for that period and anyone without the response will be followed up directly or through the treatment supporter.

The patient supporter was typically a close associate of the patient, often living in the same household. The research team trained the patient supporter on how to use the app, as well as the study objectives and treatment procedures. The primary responsibilities of the patient supporter included overseeing medication intake and assisting patients with any questions or concerns they might have. In the event of any unexpected issues, the patient supporter served as a communication link. This role was designed to provide participants with a sense of companionship and reliable guidance, helping them to adhere more effectively to their treatment commitments.

To facilitate data usage for the app, each participant in the treatment group was provided with 1GB of data per month. This provision continued for a duration of six months.

2.7.3. Post-Treatment Stage

At this stage, tests were conducted to evaluate the outcomes of the trial for both the control and experimental groups. Additionally, questionnaires were administered to participants to identify the challenges associated with telemedicine. Data collected from the CRF, and the questionnaires were then compiled and analyzed.

2.8. Data Management and Analysis

Data collated from the were analyzed with the aid of a Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, IBM version 25). Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyze the data. Descriptive statistics such as frequency count, percentage, bar charts, mean and standard deviation were used. For the inferential statistics, ANOVA was used to test for differences in outcome rates at a 0.05 level of significance.

2.9. Ethical Consideration

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics and Research Committees of both hospitals (Protocol ID: A67/2023/04/008 and ERC/2023/01/892B). Permission was secured to conduct the study and access the Pulmonary Tuberculosis Center. Prior to the commencement of data collection, written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Additionally, respondents were informed of their rights to participate voluntarily and to withdraw from the study at any time without facing any negative consequences. All procedures were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

3. Results and Discussion

A total number of 150 patients were recruited into the study. The age range of patients included in this study was 18 – 60 years with an equal number of cases and controls, and males constituting 54% of cases. New cases of TB were 72%. The highest proportion of PTB was in patients between the ages of 31 and 40 years (39.33%), with the higher degree holders accounting for this (32.67%). (

Table 1).

Among the patients exposed to ViDOTs and DOTs, only the presence of other health conditions and drug adherence significantly influenced sputum conversion. (P < 0.001). (See

Table 2 and

Table 3).

The study found PTB to be more prevalent among males as also found in a previous study in South-South Nigeria [

20]. The observed higher proportion among the educated people, as opposed to the effect of socioeconomic factors [

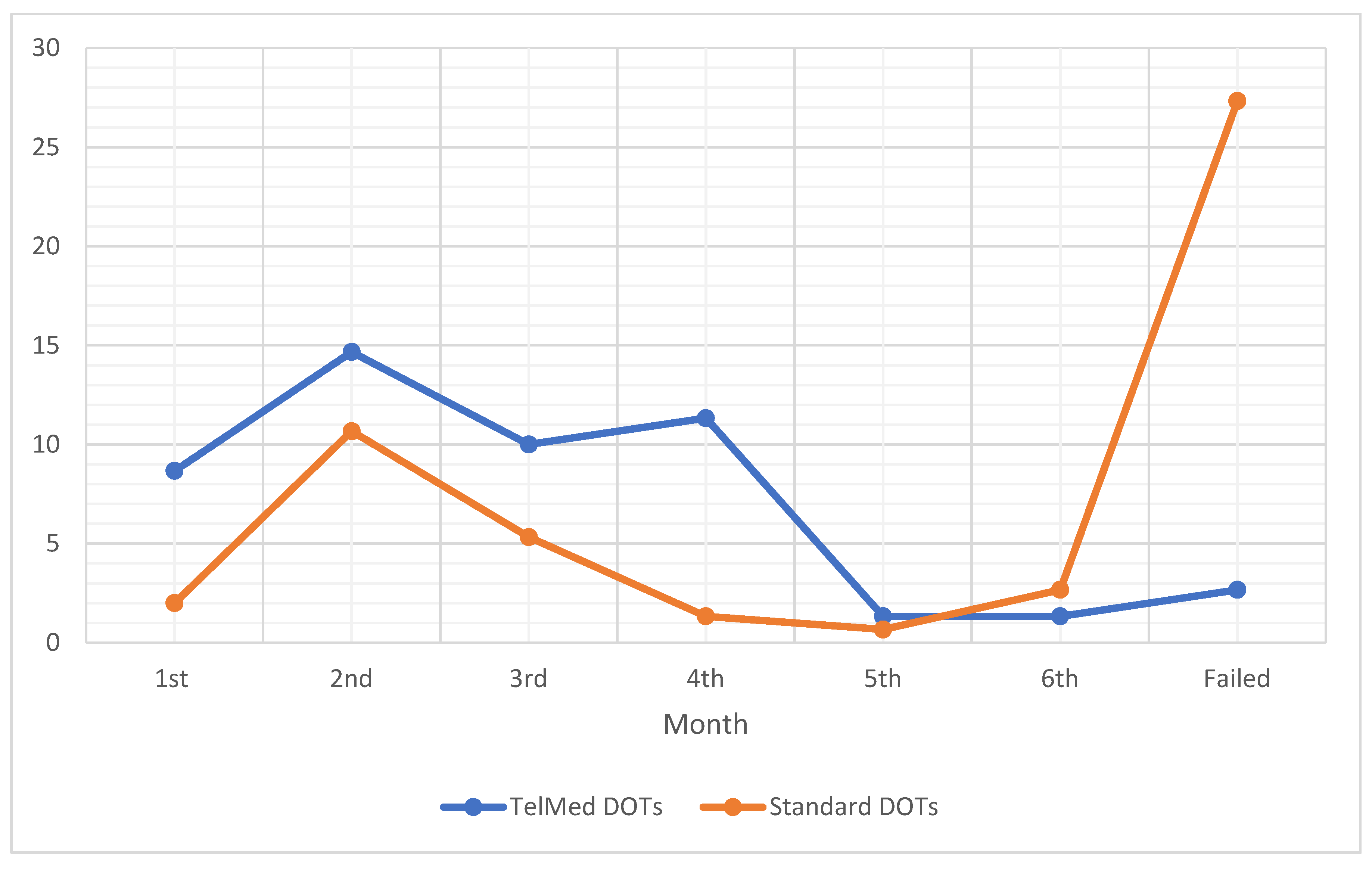

21], in this study, most likely was due to the selection bias on those who possess mobile phones that can support the ViDOTs App. The difference in conversion rates between ViDOT and DOTS is presented in

Figure 3. A progressive downward trend in the number of patients without conversion was observed from the third month. This trend continued to the fifth month, where a drastic turn was observed. This drastic turn fully corroborates a relapse tendency which became visible beyond the sixth month. This relapse affirms the WHO dataset. In this case, the causes of the relapse were inadequate treatment, immunodeficiency and drug resistance. The DOTS had higher relapse because of insufficient or improper treatment regimens due to unmonitored routine [

22]. The shortcoming of the ViDOTS may be traced to underlying conditions of the patients, such as HIV and other comorbidities [

22]. Though there is no evidence of initial drug resistance and adverse reactions to medications, the possibility of buying drugs from different pharmacies may be a major contribution to the drug resistance [

23].

The study found significant differences in sputum conversion rates within six months of treatment between the ViDOTs and DOTs groups, as well as across various age brackets and patient health conditions, including diabetes and HIV. However, smokers in both groups did not exhibit significant differences in sputum conversion rates, while patients without habits and those consuming alcohol did show significant differences. This conforms with the observation of Asemahagn et al. [

11], in their study, that the length of time taken to convert a sputum smear was positively linked with poor TB knowledge, HIV infection, higher smear grades, diabetes mellitus, undernutrition, cigarette smoking, social stigma, and delays in TB treatment. The level of adherence was much higher among the patients exposed to ViDOTs. This contributed significantly to the improved conversion rate as the patients were closely monitored through the video and reminded frequently of the need to take their medications daily. This will also help to prevent multi-drug-resistant PTB [

13].

Overall, there was a significant disparity in sputum conversion rates within six months of treatment between telemedicine (ViDOTs) and DOTs groups, indicating the potential efficacy of telemedicine in tuberculosis treatment.

4. Conclusion

Patients who adhered to telemedicine DOTs demonstrated a higher likelihood of successful conversion by the end of the treatment period, compared to those undergoing DOTs. This, therefore, calls for the use of telemedicine in the management of TB, playing a pivotal role in the prevention of drug-resistant TB and even eradication of TB in general. In conclusion, the integration of telemedicine into PTB management in Nigeria represents a promising approach to overcoming existing barriers to treatment adherence and improving health outcomes for patients. Though the DOTs allow for direct interaction, offering opportunities for the observer to monitor for side effects, provide support, answer questions, and address any challenges the patient might be facing, but the peculiarity of limited healthcare worker at the PTB center, the increasing population of patients, and patients’ inability to meet up with treatment routines are significant challenge. The ViDOT gives the required flexibility and convenience, but the possibility of inadequate treatment, immunodeficiency and drug resistance could possibly reduce the successes of the treatment. While traditional Directly Observed Therapy (DOTS) has been foundational in managing conditions like TB, Video Directly Observed Therapy (VDOT) offers a modern, patient-centered, and often more cost-effective alternative. VDOT is increasingly recognized as an equivalent and valuable tool, particularly given its ability to leverage technology for greater flexibility and reduced burden on both patients and healthcare systems. It is recommended that government established hospitals should have a sustainable drug supply in the pharmacy to reduce the possibility of drug resistance via fake drugs.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the patients who took part in this study.

Conflicts of interest

None declared by the authors.

References

- Oladimeji O, Adepoju V, Anyiam FE, San JE, Odugbemi BA, Hyera FL, Sibiya MN, Yaya S, Zoakah AI, Lawson L. Treatment outcomes of drug-susceptible Tuberculosis in private health facilities in Lagos, South-West Nigeria. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(1):e0244581. [CrossRef]

- WHO (2024). TB: new and relapse cases. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/tuberculosis---new-and-relapse-cases (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- WHO (2024). Previously treated cases tested for RR-/MDR-TB (%). Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/previously-treated-cases-tested-for-rr--mdr-tb-%28-%29 (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Acharya B, Acharya A, Gautam S, et al. Advances in diagnosis of Tuberculosis: an update into molecular diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Molecular biology reports. 2020;47:4065-4075. [CrossRef]

- Atiqah A, Tong SF, Nadirah S. Treatment outcomes of extended versus nonextended intensive phase in pulmonary tuberculosis smear positive patients with delayed sputum smear conversion: A retrospective cohort study at primary care clinics in Kota Kinabalu. Malaysian Family Physician: the Official Journal of the Academy of Family Physicians of Malaysia. 2023;18:2.

- Wardani D, Pramesona BA, Septiana T, Soemarwoto RAS. Risk factors for delayed sputum conversion: A qualitative case study from the person-in-charge of TB program’s perspectives. J Public Health Res. Oct 2023;12(4):22799036231208355. [CrossRef]

- Izudi J, Tamwesigire IK, Bajunirwe F. Sputum smear non-conversion among adult persons with bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary tuberculosis in rural eastern Uganda. Journal of Clinical Tuberculosis and Other Mycobacterial Diseases. 2020;20:100168. [CrossRef]

- Günther G, Heyckendorf J, Zellweger JP, et al. Defining outcomes of tuberculosis (treatment): from the past to the future. Respiration. 2021;100(9):843-852. [CrossRef]

- Rekha VB, Balasubramanian R, Swaminathan S, et al. Sputum conversion at the end of intensive phase of Category-1 regimen in the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis patients with diabetes mellitus or HIV infection: An analysis of risk factors. Indian Journal of Medical Research. 2007;126(5):452-458.

- Iqbal Z, Khan MA, Aziz A, Nasir SM. Time for culture conversion and its associated factors in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients at a tertiary level hospital in Peshawar, Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences. 2022;38(4Part-II):1009. [CrossRef]

- Asemahagn MA. Sputum smear conversion and associated factors among smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients in East Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia: a longitudinal study. BMC pulmonary medicine. 2021;21:1-10. [CrossRef]

- Parwati NM, Bakta IM, Januraga PP, Wirawan IMA. A health belief model-based motivational interviewing for medication adherence and treatment success in pulmonary tuberculosis patients. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(24):13238. [CrossRef]

- Olowoyo KS, Esan DT, Adeyanju BT, Olawade DB, Oyinloye BE, Olowoyo P. Telemedicine as a tool to prevent multi-drug resistant tuberculosis in poor resource settings: Lessons from Nigeria. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2024;35:100423. [CrossRef]

- Olowoyo KS, Esan DT, Olowoyo P, Oyinloye BE, Fawole IO, Aderibigbe S, Adigun MO, Olawade DB, Esan TO, Adeyanju BT. Treatment Adherence and Outcomes in Patients with Tuberculosis Treated with Telemedicine: A Scoping Review. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2025;10(3):78. [CrossRef]

- Pradipta IS, Houtsma D, van Boven JF, Alffenaar J-WC, Hak E. Interventions to improve medication adherence in tuberculosis patients: a systematic review of randomized controlled studies. NPJ primary care respiratory medicine. 2020;30(1):21. [CrossRef]

- Sekandi JN, Buregyeya E, Zalwango S, et al. Video directly observed therapy for supporting and monitoring adherence to tuberculosis treatment in Uganda: a pilot cohort study. ERJ Open Research. 2020;6(1). [CrossRef]

- Su Z, Li C, Fu H, Wang L, Wu M, Feng X. Development and prospect of telemedicine. Intelligent Medicine. 2024;4(1):1-9.

- Donahue ML, Eberly MD, Rajnik M. Tele-TB: using telemedicine to increase access to directly observed therapy for latent tuberculosis infection. Military medicine. 2021;186(Supplement_1):25-31. [CrossRef]

- Guo P, Qiao W, Sun Y, Liu F, Wang C. Telemedicine technologies and tuberculosis management: a randomized controlled trial. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2020;26(9):1150-1156. [CrossRef]

- Emorinken A, Ugheoke AJ, Agbadaola OR, et al. Prevalence and clinical profile of tuberculosis patients in a rural teaching hospital in South-South Nigeria: A ten-year retrospective study. Int J Trop Dis Health. 2023;44(8):33-42. [CrossRef]

- Ejemot-Nwadiaro RI, Nja GM, Itam EH, Ezedinachi EN. Socio-demographic and nutritional status correlates in pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Calabar, Nigeria. Asian Journal of Medicine and Health. 2020;18(10):85-98. [CrossRef]

- O. Novozhylova, Andriy Prykhodko, I.V. Bushura (2023). Causes of pulmonary tuberculosis relapses Ukraïnsʹkij pulʹmonologìčnij žurnal, 2, 44-49. [CrossRef]

- Gulrez Shah Azhar (2012). DOTS for TB relapse in India: A systematic review, Lung India, 29(2):p 147-153. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).