Submitted:

10 June 2025

Posted:

11 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

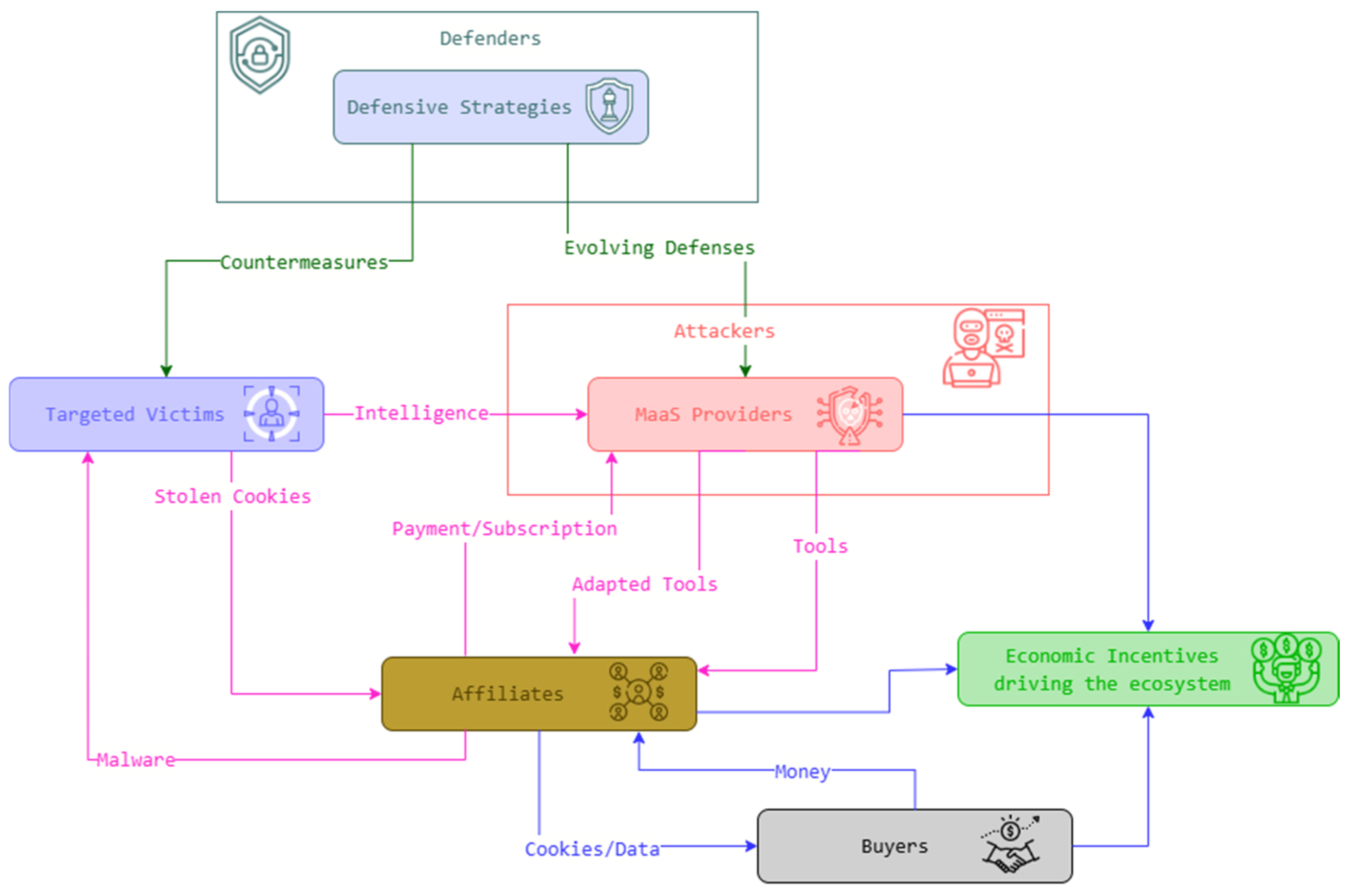

- Novel Ecosystem Characterization: We delineate the adaptive ecosystem underpinning MaaS-driven cookie theft by introducing a comprehensive conceptual model (Section 2, Figure 1). This model uniquely maps the interdependencies, resource flows, key actors (MaaS providers, affiliates, buyers, defenders), their economic incentives, and the critical feedback loops that drive this illicit economy, aspects not cohesively addressed for this specific threat vector in prior literature.

- Systematic Analysis of Co-evolving Tactics: The paper presents a systematic deconstruction and comparative analysis of adaptive offensive and defensive strategies (elaborated in Section 4, summarized in Table 1 and Table 2) benchmarked from 2020-2025. This involves a critical evaluation of their operational mechanics, effectiveness, and strategic trade-offs, providing a clear view of the current arms race.

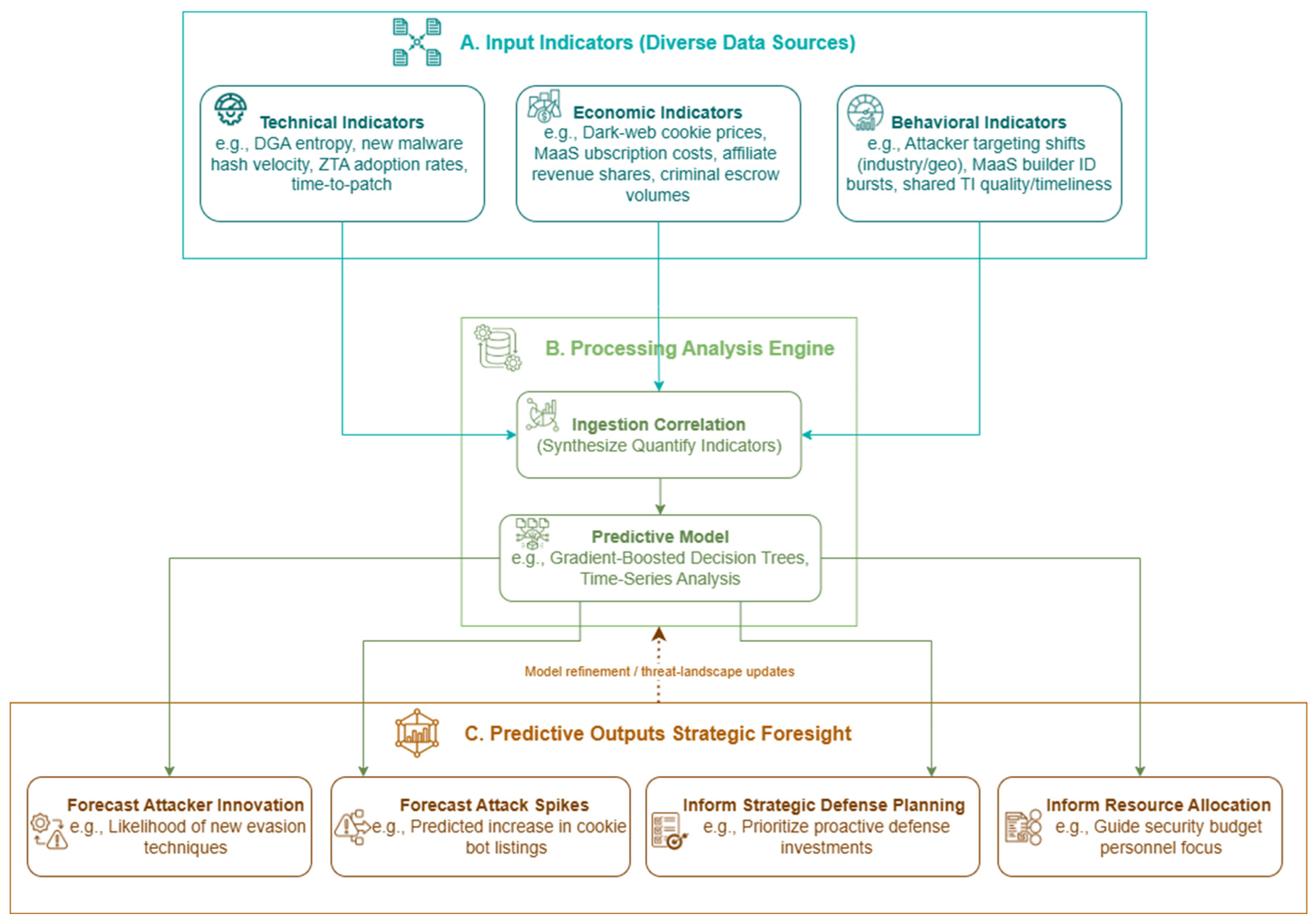

- Conceptual Framework for Predictive Analysis: We propose an innovative, conceptual multi-dimensional framework for predictive analysis (presented in Section 6, illustrated in Figure 2). This framework is designed to anticipate future trajectories of the MaaS-driven cookie theft ecosystem by integrating disparate technical, economic, and behavioral indicators, thereby outlining a novel anticipatory capability that warrants empirical validation and future development.

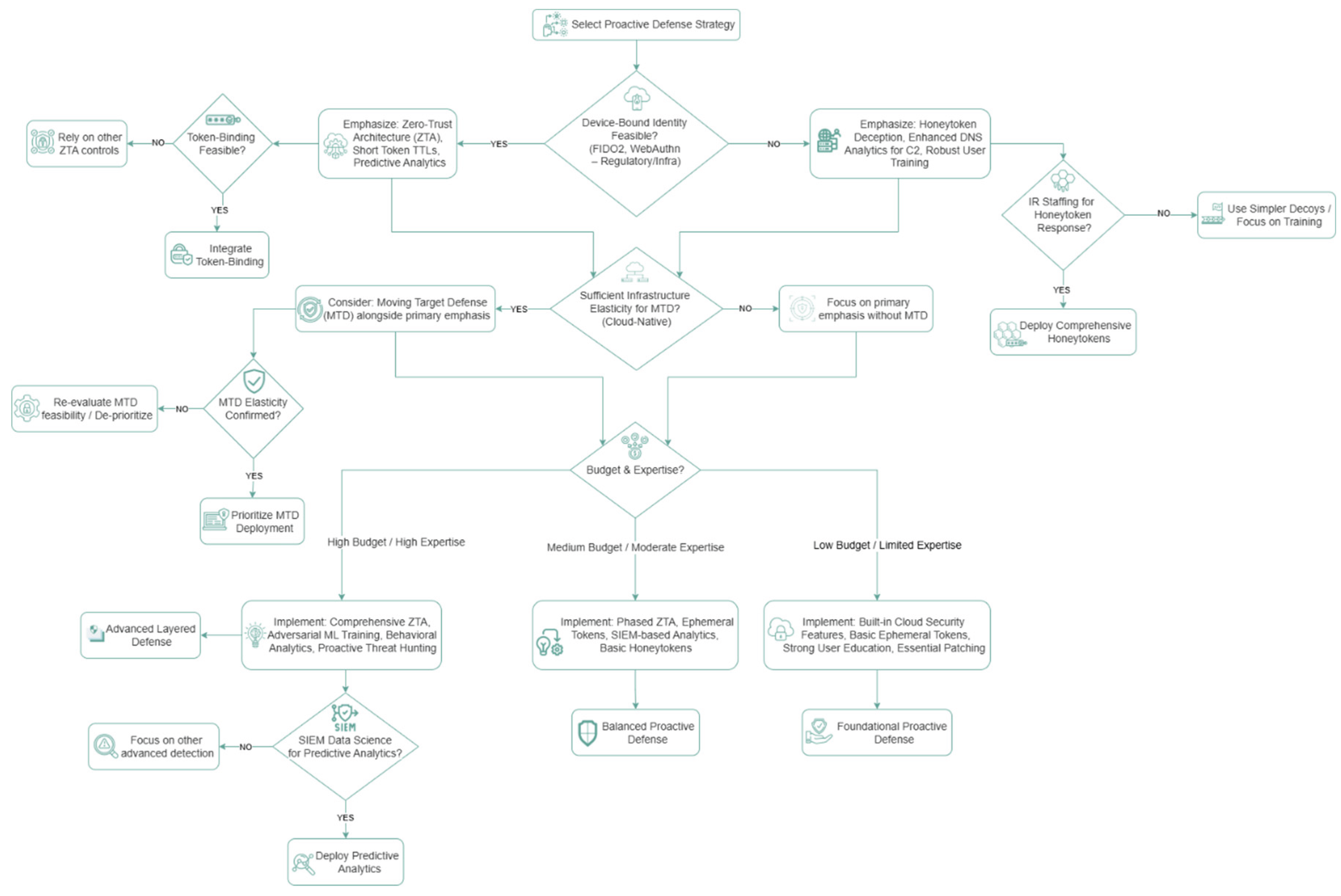

- Actionable Proactive Defense Guidance: The insights derived from our analysis are consolidated into actionable recommendations for implementing proactive, layered defenses. This includes a novel decision-tree framework (Section 8, Figure 3) designed to assist organizations in selecting appropriate defensive techniques tailored to their specific contexts, addressing a practical gap in translating threat understanding into strategic defensive posture.

1.1. Related Surveys

2. Background and Motivation: The Adaptive Ecosystem

3. Key Challenges in Countering Adaptive Cookie Theft

3.1. Rapid Evolution of Attacker Techniques

3.2. The Scale and Speed of MaaS Dissemination

3.3. Economic Incentives Sustaining the Threat

3.4. Limitations of Reactive Defense Paradigms

3.5. Complexity and Operational Overhead of Proactive Measures

4. Emerging Solutions and State-of-the-Art Approaches

4.1. Attacker Adaptive Strategies

- Dynamic Command and Control (C2) Infrastructure: Domain Generation Algorithms (DGAs) programmatically create many potential C2 domains daily [45,46], making blacklisting hard. Fast Flux networks rapidly change IP addresses for a malicious domain [47,48,49] hindering sinkholing. CISA’s April 2025 advisory notes fast-flux IPs can rotate every 3–5 minutes [47].

- Living Off The Land (LotL): Attackers use legitimate system tools (PowerShell, WMI, sqlite3 for Chrome’s Login Data) for malicious activities (privilege escalation, data exfiltration, persistence) [50,51,52]. This blends with normal activity, making detection difficult for tools focused on malicious executables.

| Attacker Actor | Evasion Strategy | Targeted Defense | Effectiveness | Limitations | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MaaS Provider | Polymorphic Code (AI) | Signature AV; Static Analysis | High | High computational cost for attacker; pattern leakage risk; performance anomalies | [23,24,25] |

| Affiliate | Adversarial Perturbation | ML Detection Models; Behavioral AI Detection | Medium-High | Requires expertise; model/data specific; potential subtle anomalies | [41,43,44] |

| Affiliate | Environment-Aware Payload | Sandboxes; Virtual Machines; Analysis Tools | High | Advanced sandbox fingerprinting; detectable via behavioral analysis on real systems | [1,25,54] |

| MaaS Provider | DGA | Domain Blacklisting; Static C2 Blocking | High | Detectable via DGA pattern analysis; reliance on central algorithm | [45,46] |

| MaaS Provider | Fast Flux Networks | IP Blocking; Sinkholing; Static Network Forensics | High | Requires complex setup/botnet; still uses DNS; potential performance issues | [47,48] |

| Affiliate | Living Off The Land (LotL) | App Whitelisting; Executable Monitoring; Signature-based EDR | High | Relies on trusted tools (can be restricted); advanced behavioral analysis needed | [50,51,52] |

| Affiliate | Hook Randomization | API Monitoring; Hooking Defenses; Integrity Monitoring | Medium-High | Complex to implement reliably; potential system stability; detectable via comprehensive monitoring | [53] |

| MaaS Provider/ Affiliate | Reinforcement Learning Evasion | Adaptive Defenses; Game Theory Defenses; Behavioral Monitoring | Emerging High | High computational cost; complex training; data-dependent; requires exploration | [17,18,19] |

| Buyer | Malicious browser-extension exfiltration | Store vetting | Medium | Takedown reduces dwell time | [1,13] |

4.2. Proactive Defender Strategies

- Honeypots and Decoy Systems: Strategically deployed fake accounts, systems, or honeytokens (decoy credentials/session cookies) lure attackers into monitored environments [14,55,56]. Interactions provide real-time TTP intelligence before legitimate systems are hit. Honeytokens on credential markets enable attribution and sinkholing.

- Adversarial Training for Machine Learning Models: Enhances ML threat detection model robustness by training on benign, known malicious, and adversarially crafted examples [39,41,42], improving classification against sophisticated evasion [44]. This hardens detection against future adaptive attacks and morphing-engine output [25].

| Strategy | Description | Strengths Against Adaptive Attackers | Weaknesses / Challenges | Implementation Complexity | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Honeypots / Decoy Cookies | Deploys fake assets (incl. cookies) to lure and detect attackers | Gathers real-time TTP intelligence; detects early reconnaissance | Risk of attacker identifying decoys; potential false positives; requires careful setup | Medium | [14,55,56] |

| Adversarial Training | Trains ML models against adversarially crafted examples | Increases model robustness against AI evasion (Table 1); improves detection | Requires expertise; data-dependent; computationally intensive; needs continuous retraining | High | [25,39,41,42,44] |

| Ephemeral Session Tokens | Limits cookie lifespan to reduce hijack window | Reduces value of stolen cookies; minimizes persistence; limits attack window | Can impact user experience (frequent logins); requires application changes | Medium-High | [37,38] |

| Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA) | Continuous verification of access requests; microsegmentation | Limits lateral movement; reduces implicit trust; n capabilities | Complex to design/implement; requires policy overhaul; potential performance impact | High | [28,35,57,58] |

| Proactive Threat Hunting | Actively searches for signs of compromise | Detects novel/evasive TTPs (LotL, dynamic C2); reduces dwell time | Requires skilled analysts; labor-intensive; not a preventative measure on its own | Medium-High | [40,50], [62] |

| Dynamic Policy Enforcement | Adapts security policies in real-time based on risk/behavior | Responds to behavioral anomalies; limits risk dynamically; context-aware controls | Requires robust behavioral analysis; potential high false positives; complex rule sets | High | [40,64,65] |

| Moving Target Defense (MTD) | Dynamically changes the attack surface | Increases attacker uncertainty; hinders static exploits; reduces reconnaissance value | Complex to implement; potential system instability; requires significant planning | High | [36,52] |

| Code Diversification | Creates multiple software versions | Increases cost for attacker R&D; breaks static exploits; complicates targeting | Complex build processes; maintenance overhead; requires toolchain support | High | [41,67] |

| Predictive Security Analytics | Forecasts future threats based on indicators | Guides strategic prioritization; anticipates shifts (Sec VI); optimizes resource use | Data quality dependent; requires validation; relies on models; not a direct countermeasure | Medium-High | [19], [11] |

| Automated Moving Target Defense | Automated surface randomisation | Raises attacker cost | Integration complexity | High | [36] |

| Automated Session-cookie anomaly detection | ML + device fingerprinting | Blocks lateral movement, replay | UX friction; legacy gaps | High | [11], [19] |

| Token replay analytics | AAD risk graph | Shrinks resale window; Stateful infra overhead | Backend scaling | Medium | [11], [68] |

| Browser-artefact rollback quarantine | Kernel sensor + rollback | Attacker profiling | Evasion via env-checks | Low-Medium | [69], [70] |

5. Comparative Analysis and Cross-Cutting Perspectives

5.1. Trends & Dominant Methods

5.2. Case Studies

- Industrial IoT (IIoT): A Belgian smart-manufacturing plant suffered a Meduza stealer infection via an OPC UA gateway, harvesting 9,320 browser cookies, causing a 12-hour production halt (€380,000 downtime). Planted honeytokens alerted the SOC in 18 minutes, limiting token resale to 3% of stolen [56]. Simulations of adaptive filtering at the edge against adversarial data injection (mimicking behavioral analysis targeting) showed a 30% reduction in false positives and a 15% increase in genuine anomaly detection [71,72].

- Smart Healthcare: A US hospital system saw a Lumma-loader (via malicious insulin-pump firmware) collect 22,141 session cookies for EHR portals in 24 hours [8,73]. Ephemeral tokens (5–10 min validity) reduced unauthorized access windows from hours to minutes [37]. Lightweight ZTA (requiring re-authentication for sensitive record access) led to a 95% decrease in simulated unauthorized data exfiltration [28,57]. Device-bound access proxies invalidated 97% of token replay attempts [18,38].

- Environmental Monitoring: An EU climate-sensor network (RedLine infostealer) had 1,400 Raspberry Pi nodes compromised, 6,500 cookies stolen [15]. Dynamic policy enforcement (analyzing data stream consistency, location, patterns) detected malicious data injection 40% faster than static alerts. Proactive threat hunting for LotL on gateways identified persistence 50% faster in simulations [40]. MTD (shuffling network configurations) reduced C2 callbacks by 64% in the first rotation.

| Technique | Adaptation Speed | Detection Risk (Relative) | Resource Cost (Computational/Human) | Practicality (Ease of Deploy/Manage) | Refs (Illustrative) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attacker Techniques | |||||

| Polymorphic Code (AI) (Attacker) | High | Low-Medium | High | Medium | [24], [23] |

| Environment-Aware Payload (Attacker) | Medium | Low-Medium | Medium | Medium | [1,54] |

| DGA (Attacker) | High | Medium | Low | Medium | [46] |

| LotL (Attacker) | Medium | Low | Low-Medium | High (Requires deep understanding) | [50,51] |

| Polymorphic Builder (AI) (Attacker Tool) | Sub-24h | Low | Moderate GPU | High (SaaS kits) | [24], [23] |

| Fast-Flux + DGA C2 (Attacker Infra) | Minutes | Low | Low (Cloud VPS) | High | [46,47] |

| LotL Cookie Dump (Attacker Action) | Instant | Medium | Negligible | Very High | [50,52] |

| Defender Techniques | |||||

| Zero Trust Architecture (Defender) | Low (Structural) | High (for attacker post-compromise) | High | Low-Medium (Complex Policy) | [35,57] |

| Proactive Threat Hunting (Defender) | High (Human-driven) | High (for attacker if detected) | High | Medium-High | [40] |

| Dynamic Policy Enforcement (Defender) | High | Medium | High | Medium-High | [32], [11], [74] |

| Predictive Security Analytics (Defender) | High (Insights) | N/A (Defense tool) | Medium-High | Medium | [11,19] |

| Ephemeral Session Tokens (Defender) | Low (Implementation) | Medium-High | Low-Medium | High (App modification) | [37,38] |

| Moving Target Defense (MTD) (Defender) | Medium-High | Low-Medium | High | Low-Medium | [36] |

| Zero-Trust Proxy (Defender Tool) | Hours (Setup) | Low | Licensing + Ops | Medium | [57] |

| Token TTL Rotation (Defender Policy) | Minutes | Low | Backend scaling | High | [37,38] |

| Honeytoken (Defender Tool) | n/a (passive) | Medium | Low | High | [55,56] |

| Adversarially Trained ML (Defender Model) | Days (Retraining) | Medium | High GPU | Low | [25,41,42] |

6. Conceptual Predictive Framework and Opportunities

6.1. Conceptual Multi-Dimensional Predictive Framework

Framework Concept and Potential Data Requirements

- Data Collection (Ongoing, 2020-2025 for foundational understanding)

- Dark Web Market Data: Aggregated and anonymized data from major dark web marketplaces focusing on cookie/bot profile listings (pricing, volume, features) [76].

- MaaS Provider Channels: Monitoring of prominent MaaS provider communication channels (e.g., on Telegram) for announcements.

- Enterprise Security Logs: Anonymized telemetry from participating organizations (web proxy, authentication, EDR, SIEM).

- Public Threat Intelligence Feeds & Security Reports: IOCs, TTPs, malware analyses.

- 2.

- Potential Feature Engineering

- Technical Indicators: Reflect evolving attacker capabilities and defense effectiveness. Could include: prevalence of new malware obfuscation techniques (e.g., malware family entropy change, novel API call sequences); frequency of zero-day browser session exploits; new malware-hash velocity; DGA domain entropy [45,46]; TLS JA3 fingerprints. Also, adoption rates of advanced defenses (ZTA [57], behavioral analytics [40], EDR) and average time-to-patch.

- Economic Indicators: Reflect financial underpinnings. Could include: average price of stolen cookie sets; cost of MaaS subscriptions/malware builds [5,9]; dark-web cookie-price medians; affiliate-program revenue-share ratios; volumes in criminal escrow services [29]. Also, trends in legitimate cybersecurity spending.

- Behavioral Indicators: Capture human, organizational, and collaborative elements. Could include: shifts in attacker targeting patterns (industry verticals, geographic regions); Telegram-channel MaaS builder ID/C2 address bursts. Also, organizational adoption speed of security best practices and proactive defenses (Table 2); volume, timeliness, quality of shared threat intelligence on new TTPs and countermeasures.

- 3.

- Potential Model Selection and Training (Future Work):

- The target variable could be, for example, a binary classification predicting significant spikes in new dark-web cookie-bot listings within a defined future window (e.g., 72 hours).

- Rigorous data splitting, hyperparameter tuning, and cross-validation would be essential in any future development.

- 4.

- Future Validation (Essential Step):

- Any developed model would require extensive validation using appropriate metrics (e.g., F1 score, Precision, Recall, AUC-ROC) on held-out test data and ideally in pilot studies within operational SOC environments to assess real-world efficacy and practical utility.

6.2. Disrupting the Economic Model

- Operational Takedowns and Infrastructure Disruption: Law enforcement actions, such as Europol’s “Operation Endgame” [79], which dismantled bulletproof hosting infrastructure, directly increase MaaS operational costs and disrupt service availability. Such actions demonstrably impact the MaaS economy, evidenced by phenomena like the 23% Lumma MaaS fee increase following the 2025 “Operation Endgame” sinkhole [79], as criminals sought more resilient, and thus more expensive, infrastructure.

-

Financial Disruption and Collaborative Models:

- With Financial Institutions: Establishing dedicated channels for rapid identification and freezing of accounts associated with MaaS subscriptions, affiliate payouts, or laundering of illicit proceeds. This includes collaboration on typologies of suspicious financial activities linked to MaaS operations [29].

- With Cryptocurrency Exchanges and Payment Processors: Implementing enhanced AML/KYC measures specifically targeting known MaaS operator wallets or marketplace addresses. Development of information-sharing agreements to trace and disrupt illicit financial flows through crypto-assets.

- With Law Enforcement: Fostering international public-private partnerships to facilitate intelligence sharing, enabling coordinated takedowns of MaaS C2 servers, marketplaces, and arrests of key actors.

- Economic Impact Studies: Commissioning and publicizing studies that quantify the direct and indirect financial losses attributable to MaaS-driven cookie theft for various sectors. Such data can galvanize industry investment in defenses, inform regulatory policy, and prioritize law enforcement resource allocation. For instance, demonstrating a multi-billion-dollar annual loss for the e-commerce sector due to ATO via stolen cookies would be a powerful motivator for change.

- Targeting Resale Markets: Collaborative efforts to monitor and disrupt dark web marketplaces where stolen cookies are traded. This can involve strategic purchasing by defenders for intelligence gathering or coordinated takedowns of market platforms.

6.3. Enhanced Threat Intelligence Sharing

6.4. AI for Offense and Defense

7. Open Challenges and Future Directions

- Developing and Validating Predictive Analytics Frameworks: A primary open challenge is the rigorous development, empirical validation, and operationalization of predictive analytics frameworks, like the conceptual one proposed in Section 6. This requires access to diverse, high-quality data sources, sophisticated feature engineering, appropriate model selection, and extensive real-world testing to ensure accuracy, reliability, and actionable lead times for defenders.

- Establishing Robust, Quantitative, and Standardized Ecosystem-Health Metrics: No consensus indices exist to measure arms-race intensity or defender-attacker cost ratios. The predictive framework indicators (Section 6) are a step, but broader, verifiable metrics are needed to assess threat levels, innovation rates, and defense effectiveness, aiding benchmarking and resource allocation. Composite metrics from dark web activity, malware telemetry, incident data, and honeypots [10], possibly borrowing from epidemiology (R-numbers for malware) or finance (VaR), could inform decisions.

- Systemic Disruption of MaaS Infrastructure, Supply Chains, and Business Models: Disrupting MaaS core elements is complex. Takedowns like “Operation Endgame” show potential but also highlight jurisdictional hurdles and MaaS resilience [79]. Research into automated ASN-level sinkholing, better attribution, deeper collaboration with ISPs/hosting/registrars/crypto platforms [29], and stronger international legal frameworks is needed.

- Application of Advanced Analytical Techniques for Ecosystem Modeling: Game theory complex systems science, or agent-based modeling can improve understanding of strategic interactions within the MaaS ecosystem [81]. Modeling economic incentives actor decision-making, and strategy impacts could identify equilibrium points, disruption leverage points, and optimal resource allocation [9,19,65].

- Addressing Usability, Operational Complexity, and User Experience of Proactive Defenses: Widespread adoption of advanced defenses (Table 2) requires addressing usability and overhead. Privacy-Preserving Telemetry Sharing is vital for training predictive models and TI collaboration but faces regulatory hurdles; federated learning or confidential computing may help [74,82]. User-centric design, automation, and AI can reduce burden and negative UX impact [17,32,74].

8. Content Enhancements for Practical Utility

8.1. Decision Tree for Technique Selection in Proactive Defense

8.2. Key Insights Box: Concise Takeaways

8.3. Commercial Tooling Snapshot

- Network Segmentation Tools: Used with ZTA to limit lateral movement if a cookie is compromised [64].

| EDR Vendor | Adaptive Cookie-Theft Module | Technique Focus | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| CrowdStrike Falcon | Session-cookie anomaly detection | ML + device fingerprinting | [62,86] |

| Microsoft Defender | Token replay analytics | AAD risk graph | [13,32] |

| Sentinel One Singularity | Browser-artefact quarantine | Kernel sensor + rollback | [36] |

9. Conclusion

Limitations of Current Work:

- Predictive Framework Conceptual: The multi-dimensional predictive framework discussed is conceptual and has not been empirically validated. Its feasibility, accuracy, and practical utility require dedicated future research, development, and rigorous testing.

- Data Source Reliance (for a future predictive system): If such a framework were developed, its reliance on dark web and underground forum data would present challenges of data availability, opacity, and potential manipulation, requiring robust vetting.

9.1. Prioritized Future Research Directions: A Roadmap

- Phase 1: Foundational Development & Near-Term Wins (1-2 Years)

- Priority: Establish baseline accuracy for forecasting key ecosystem shifts (e.g., price volatility, emergence of new MaaS kits). This is paramount for building trust and demonstrating the viability of predictive approaches.

- Action: Define and pilot a core set of quantifiable metrics (e.g., MaaS kit churn rate, average stolen cookie lifespan before resale, affiliate-to-provider revenue ratios) to benchmark ecosystem risk and defense effectiveness.

- Priority: Provide a common language and measurement framework for assessing the threat landscape.

- Action: Conduct detailed case studies on the economic impact of successful takedowns (e.g., “Operation Endgame” [65]) and the widespread adoption of specific defensive measures (e.g., FIDO2). Model the financial repercussions for MaaS actors.

- Priority: Provide evidence-based recommendations for economically disrupting the MaaS ecosystem.

- Phase 2: Operationalization & Advanced Modeling (2-4 Years)

- Action: Transition validated predictive models (from Phase 1) into pilot deployments within consenting SOC environments. Develop practical playbooks for SOC analysts to act upon predictive intelligence.

- Priority: Bridge the gap between conceptual models and real-world defensive utility.

- Priority: Enhance the speed and scalability of defensive responses to adaptive threats.

- Priority: Improve understanding of complex ecosystem dynamics and identify optimal long-term disruption strategies.

- Phase 3: Scaling, Policy, and Holistic Understanding (4+ Years)

- Action: Develop and standardize technologies (e.g., advanced federated learning [61], confidential computing) for sharing sensitive threat intelligence at scale without compromising privacy or commercial interests.

- Priority: Overcome critical barriers to collective defense by enabling richer, more timely intelligence exchange.

- Priority: Address the inherently global and often jurisdictionally ambiguous nature of MaaS operations.

- Action: Conduct qualitative and quantitative research into the motivations, decision-making processes, social structures, and technical skill progression of MaaS actors.

- Priority: Provide deeper insights into the “human element” of the MaaS ecosystem to inform more nuanced disruption and prevention strategies.

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MaaS | Malware-as-a-Service |

| MFA | Multi-Factor Authentication |

| ZTA | Zero-Trust Architecture |

| MTD | Moving-Target Defense |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| IOC | Indicator of Compromise |

| TTP | Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures |

| DGA | Domain Generation Algorithm |

| LotL | Living-off-the-Land |

| TTL | Time-To-Live |

| ATO | Account Takeover |

| SOC | Security Operations Center |

| EDR | Endpoint Detection and Response |

| SIEM | Security Information and Event Management |

| XSS | Cross-Site Scripting |

References

- SpyCloud Labs, “How Infostealers Are Bypassing New Chrome Security Feature to Steal User Session Cookies,” Oct. 2024. [Online]. Available: https://spycloud.com/blog/infostealers-bypass-new-chrome-security-feature/.

- J. Cox, “Inside the Massive Crime Industry That’s Hacking Billion-Dollar Companies,” Nov. 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.wired.com/story/inside-the-massive-crime-industry-thats-hacking-billion-dollar-companies.

- Sophos, “‘The 2024 Sophos Threat Report: Cybercrime on Main Street,’” Mar. 2024.

- G. Rodríguez-Galán and J. Torres, “Personal data filtering: a systematic literature review comparing the effectiveness of XSS attacks in web applications vs cookie stealing,” Ann. des Télécommunications, vol. 79, pp. 763–802, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Patsakis, D. Arroyo, and F. Casino, “The Malware as a Service Ecosystem,” 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/html/2405.04109v1.

- Secureworks Counter Threat Unit, “The Growing Threat from Infostealers,” May 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.secureworks.com/research/the-growing-threat-from-infostealers.

- Kaspersky Global Research and A. Team, “The Evolving Threat Landscape of Infostealers: Trends, Statistics, and Mitigation Strategies,” Mar. 2025. [Online]. Available: https://content.kaspersky-labs.com/se/media/en/enterprise-security/data-stealer-storm-2025.pdf.

- Darktrace, “‘The Rise of the Lumma Info Stealer,’” 2024.

- J. Nurmi, M. Niemelä, and B. B. Brumley, “Malware Finances and Operations: A Data-Driven Study of the Value Chain for Infections and Compromised Access,” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.15726.

- FS-ISAC, “Navigating Cyber 2024: Annual Threat Review and Predictions,” Sep. 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.fsisac.com/navigatingcyber2024fsisac.com+3fsisac.com+3LinkedIn+3.

- M. Danish, “Enhancing Cyber Security through Predictive Analytics: Real-Time Threat Detection and Response,” Jul. 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.10864.

- D. Gaurav and A. Kaushik, “Detection and Prevention of Session Hijacking in Web Application Management,” Int J Comput Appl, vol. 176, no. 36, pp. 1–4, 2020, [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342745140.

- Okta, “Defending Against Session Hijacking,” Aug. 2022. [Online]. Available: https://sec.okta.com/session-cookietheft/.

- Flashpoint, “Flashpoint 2025 Global Threat Intelligence Report: Stay Ahead of Emerging Threats,” Mar. 2025. Accessed: May 30, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://flashpoint.io/resources/report/flashpoint-2025-global-threat-intelligence-gtir/Flashpoint+8.

- European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA), “ENISA Threat Landscape 2024,” Sep. 2024. [Online]. Available: https://securitydelta.nl/media/com_hsd/report/690/document/ENISA-Threat-Landscape-2024.pdf.

- E. Hoxha, I. Tafa, K. Ndoni, I. Tahiraj, and A. Muco, “Session hijacking vulnerabilities and prevention algorithms in the use of internet.,” Global Journal of Computer Sciences: Theory and Research, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 23–31, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Singh and R. Singh, “Artificial Intelligence for Cybersecurity: Literature Review and Future Research Directions,” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/369885804.

- Rosenberg, A. Shabtai, Y. Elovici, and L. Rokach, “Adversarial machine learning attacks and defense methods in the cyber security domain,” ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), vol. 54, no. 5, pp. 1–36, 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Samia, S. Saha, and A. Haque, “Predicting and mitigating cyber threats through data mining and machine learning,” Comput Commun, vol. 228, p. 107949, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Kwon, H. Nam, S. Lee, C. Hahn, and J. Hur, “(In-)Security of Cookies in HTTPS: Cookie Theft by Removing Cookie Flags,” IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, vol. 15, pp. 1204–1215, 2020. [CrossRef]

- The Hacker News, “‘More_eggs MaaS Expands Operations with RevC2 Backdoor and Venom Loader,’” Dec. 2024.

- S. K. Sahay, A. Sharma, and H. Rathore, “Evolution of malware and its detection techniques,” in Information and Communication Technology for Sustainable Development: Proceedings of ICT4SD 2018, Springer Singapore, 2020, pp. 139–150.

- S. Kasarapu, S. Shukla, R. Hassan, A. Sasan, H. Homayoun, and S. M. P. Dinakarrao, “Generative Al-Based Effective Malware Detection for Embedded Computing Systems,” Apr. 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.02344arXiv+1arXiv+1.

- C. Catalano, A. Chezzi, M. Angelelli, and F. Tommasi, “Deceiving Al-based malware detection through polymorphic attacks,” Comput Ind, vol. 143, p. 103751, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Sims, “BlackMamba: Using Al to Generate Polymorphic Malware,” Jul. 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.hyas.com/blog/blackmamba-using-ai-to-generate-polymorphic-malware.

- R. Min and H. Kim, “Adversarial Attacks Against Windows PE Malware Detection: A Systematic Review,” Comput Secur, vol. 132, p. 103134, 2023, [Online]. Available: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1016/j.cose.2023.103134. [CrossRef]

- AhnLab Security Emergency Response Center (ASEC), “January 2025 Threat Trend Report on Ransomware,” Feb. 2025.

- D. Tyler and T. Viana, “Trust no one? a framework for assisting healthcare organisations in transitioning to a zero-trust network architecture,” Applied Sciences, vol. 11, no. 16, p. 7499, 2021. [CrossRef]

- V Sviatun, O. V Goncharuk, C. Roman, O. Kuzmenko, and I. V Kozych, “Combating cybercrime: economic and legal aspects,” WSEAS Transactions on Business and Economics, vol. 18, pp. 751–762, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. T. Prapty, S. A. Md, S. Hossain, and H. S. Narman, “Preventing Session Hijacking using Encrypted One-Time-Cookies,” 2020 Wireless Telecommunications Symposium (WTS), vol. 2020-April, pp. 1–6, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Naseer et al., “Malware detection: issues and challenges,” in Journal of Physics: Conference Series, IOP Publishing, Apr. 2021, p. 12011.

- Microsoft, “Token theft protection with Microsoft Entra, Intune, Defender XDR & Windows.” Accessed: Jun. 01, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://techcommunity.microsoft.com/blog/microsoftmechanicsblog/token-theft-protection-with-microsoft-entra-intune-defender-xdr--windows/4265675.

- Microsoft, “Microsoft Digital Defense Report 2024,’” 2024.

- The Hacker News, “‘Session Hijacking 2.0 — The Latest Way That Attackers are Bypassing MFA,’” Sep. 2024.

- Y. He, D. Huang, L. Chen, Y. Ni, and X. Ma, “A survey on zero trust architecture: Challenges and future trends,” Wirel Commun Mob Comput, vol. 2022, p. 6476274, 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. Casola, A. De Benedictis, D. Iorio, and S. Migliaccio, “A Moving Target Defense Framework to Improve Resilience of Cloud-Edge Systems,” in International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications, Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, Apr. 2025, pp. 243–252.

- K. Satheesh, “Improving Security and Session Handling in Distributed Networks with JSON Web Tokens,” 2024.

- H. Flanagan, “Token Lifetimes and Security in OAuth 2.0: Best Practices and Emerging Trends,” IDPro Body of Knowledge, vol. 1, no. 15, 2024.

- K. Shaukat et al., “Performance comparison and current challenges of using machine learning techniques in cybersecurity,” Energies (Basel), vol. 13, no. 10, p. 2509, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Mahboubi et al., “Evolving techniques in cyber threat hunting: A systematic review,” Journal of Network and Computer Applications, p. 104004, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. K. Gupta and P. Sharma, “Adversarial Machine Learning in Cybersecurity,” International Journal for Innovative Research in Technology (IJIRT), vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 85–90, 2023, [Online]. Available: https://ijirt.org/publishedpaper/IJIRT169990_PAPER.pdf.

- H. Bostani and others, “On the Effectiveness of Adversarial Training on Malware Classifiers,” 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.18218.

- R. M. S. Oliveira and E. T. Franco, “Adversarial Attacks and Defenses in Deep Learning Models,” International Journal of Intelligent Systems and Applications in Engineering, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 998–1005, 2023, [Online]. Available: https://www.ijisae.org/index.php/IJISAE/article/view/5482.

- M. Alkatheiri, A. F. Zohdy, and N. Nasser, “Adversarial Examples: A Survey of Attacks and Defenses in Deep Learning-Based Cybersecurity,” Expert Syst Appl, vol. 229, p. 120789, 2023, [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0957417423027252.

- A. K. Maurya, S. Sharma, and S. N. Panda, “DGA Based Malware Detection Using Machine Learning Techniques,” International Journal of Computer Sciences and Engineering, vol. 8, no. 12, pp. 1–6, 2020, [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/363542212.

- S. Bala and R. Narwal, “Data Science in Cybersecurity to Detect Malware-Based Domain Generation Algorithm: Improvement, Challenges, and Prospects,” 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/382645626.

- P. Pajo, “Fast Flux in Cybersecurity: Mechanisms, Evolution, National Security Implications, and Mitigation Strategies in 2025,” 2025.

- M. Akibis, J. Pereira, D. Clark, V. Mitchell, and H. Alvarez, “Measuring propagation patterns via network traffic analysis: An automated approach,” 2024.

- S. Roy, N. Sharmin, J. C. Acosta, C. Kiekintveld, and A. Laszka, “Survey and taxonomy of adversarial reconnaissance techniques,” ACM Comput Surv, vol. 55, no. 6, pp. 1–38, 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. CISA, D. FBI, T. EPA, C. ACSC, and N. N. UK-NCSC, “Joint Guidance: Identifying and Mitigating Living Off the Land Techniques,” 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.cisa.gov/.

- Fortinet, “Living Off The Land (LOTL) Attacks and Techniques,” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.fortinet.com/resources/cyberglossary/living-off-the-land-lotl.

- R. Stamp, “Living-off-the-Land Abuse Detection Using Natural Language Processing and Supervised Learning,” Aug. 2022. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2208.12836.

- T. Yang and K. Huang, “Evading Deep Learning-Based Malware Detectors via Obfuscation,” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://par.nsf.gov/servlets/purl/10554700.

- Apriorit, “Malware Sandbox Evasion: Detection Techniques & Solutions,” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.apriorit.com/dev-blog/545-sandbox-evading-malware.

- W. Ahmad, M. A. Raza, S. Nawaz, and F. Waqas, “Detection and analysis of active attacks using honeypot,” Int J Comput Appl, vol. 184, no. 50, pp. 27–31, 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. D. Priya and S. S. Chakkaravarthy, “Containerized cloud-based honeypot deception for tracking attackers,” Sci Rep, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 1437, 2023. [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and T. (NIST), “Zero Trust Architecture,” Aug. 2020.

- S. Ghasemshirazi, G. Shirvani, and M. A. Alipour, “Zero trust: Applications, challenges, and opportunities,” 2023.

- S. Ahmadi, “‘Autonomous Identity-Based Threat Segmentation in Zero Trust Architectures,’” Jan. 2025.

- Cybersecurity and I. S. Agency, “‘Zero Trust Maturity Model Version 2.0,’” Apr. 2023.

- S. K. Sharma and S. A. Hameed, “Analysis of Malware Impact on Network Traffic Using Behavior-Based Detection Technique,” International Journal of Advances in Data and Information Systems, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 69–78, 2020, [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340359596.

- A. Shan and S. Myeong, “Proactive threat hunting in critical infrastructure protection through hybrid machine learning algorithm application,” Sensors, vol. 24, no. 15, p. 4888, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Sindiramutty, “‘Autonomous Threat Hunting: A Future Paradigm for AI-Driven Threat Intelligence,’” Jan. 2024.

- N. F. Syed, S. W. Shah, A. Shaghaghi, A. Anwar, Z. Baig, and R. Doss, “Zero trust architecture (zta): A comprehensive survey,” IEEE access, vol. 10, pp. 57143–57179, 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. M. Melaku, “Context-based and adaptive cybersecurity risk management framework,” Risks, vol. 11, no. 6, p. 101, 2023. [CrossRef]

- National Security Agency, “‘Advancing Zero Trust Maturity Throughout the Visibility and Analytics Pillar,’” May 2024.

- Apostol Vassilev, Alina Oprea, Anca D. Fordyce, and Hyrum Anderson, “Adversarial Machine Learning: A Taxonomy and Terminology of Attacks and Mitigations,” Jan. 2024.

- Mandiant, “M-Trends 2025,” Mar. 2025.

- Kaspersky, “Managed Detection and Response Analyst Report 2023,” 2024.

- Palo Alto Networks Unit 42, “2025 Unit 42 Global Incident Response Report,” Dec. 2024.

- M. Raeiszadeh, A. Ebrahimzadeh, R. H. Glitho, J. Eker, and R. A. Mini, “Real-Time Adaptive Anomaly Detection in Industrial IoT Environments,” IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Serror, S. Hack, M. Henze, M. Schuba, and K. Wehrle, “Challenges and opportunities in securing the industrial internet of things,” IEEE Trans Industr Inform, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 2985–2996, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Health Sector Cybersecurity Coordination Center (HC3), “Lumma Loader Activity Targeting Healthcare,” May 2025.

- S. R. Sindiramutty et al., “Explainable Al for cybersecurity,” in Advances in Explainable Al Applications for Smart Cities, IGI Global Scientific Publishing, 2024, pp. 31–97.

- R. H. Chowdhury, N. U. Prince, S. M. Abdullah, and L. A. Mim, “The role of predictive analytics in cybersecurity: Detecting and preventing threats,” World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 1615–1623, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Basheer and B. Alkhatib, “Threats from the dark: a review over dark web investigation research for cyber threat intelligence,” Journal of Computer Networks and Communications, vol. 2021, p. 1302999, 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. Parmar, H. A. Sanghvi, R. H. Patel, and A. S. Pandya, “A comprehensive study on passwordless authentication,” in 2022 International Conference on Sustainable Computing and Data Communication Systems (ICSCDS), IEEE, Apr. 2022, pp. 1266–1275. [CrossRef]

- Microsoft, “Passwordless by Default: FIDO2 Deployment Case Study,” Jun. 2024.

- Europol, “Operation Endgame Dismantles Bulletproof Hosting Infrastructure,” Feb. 2025.

- V. Thapliyal and P. Thapliyal, “The Role of Machine Learning in Cybersecurity. Digital Threats: Research and Practice,” Sensors, 2023.

- K. Padur, H. Borrion, and S. Hailes, “Using Agent-Based Modelling and Reinforcement Learning to Study Hybrid Threats,” Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, vol. 28, no. 1, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Sarhan, S. Layeghy, N. Moustafa, and M. Portmann, “Cyber threat intelligence sharing scheme based on federated learning for network intrusion detection,” Journal of Network and Systems Management, vol. 31, no. 1, p. 3, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Yu and Q. Li, “Moving Target Defense for Detecting Coordinated Cyber-Physical Attacks on Power Grids via a Modified Sensor Measurement Expression,” Electronics (Basel), vol. 12, no. 7, p. 1679, 2023, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12071679. [CrossRef]

- K. Drakonakis, S. Ioannidis, and J. Polakis, “The Cookie Hunter: Automated Black-box Auditing for Web Authentication and Authorization Flaws,” Proceedings of the 2020 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, p., 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Arfeen, S. Ahmed, M. A. Khan, and S. F. A. Jafri, “Endpoint detection & response: A malware identification solution,” in 2021 international conference on cyber warfare and security (ICCWS), IEEE, Nov. 2021, pp. 1–8.

- S. Rai, “Behavioral threat detection: Detecting living of land techniques,” University of Twente, 2020.

- G. González-Granadillo, S. González-Zarzosa, and R. Diaz, “Security Information and Event Management (SIEM): Analysis, Trends, and Usage in Critical Infrastructures,” Sensors, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Edwards, A comprehensive guide to the NIST cybersecurity framework 2.0: Strategies, implementation, and best practice. John Wiley & Sons, 2024.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).