Submitted:

10 June 2025

Posted:

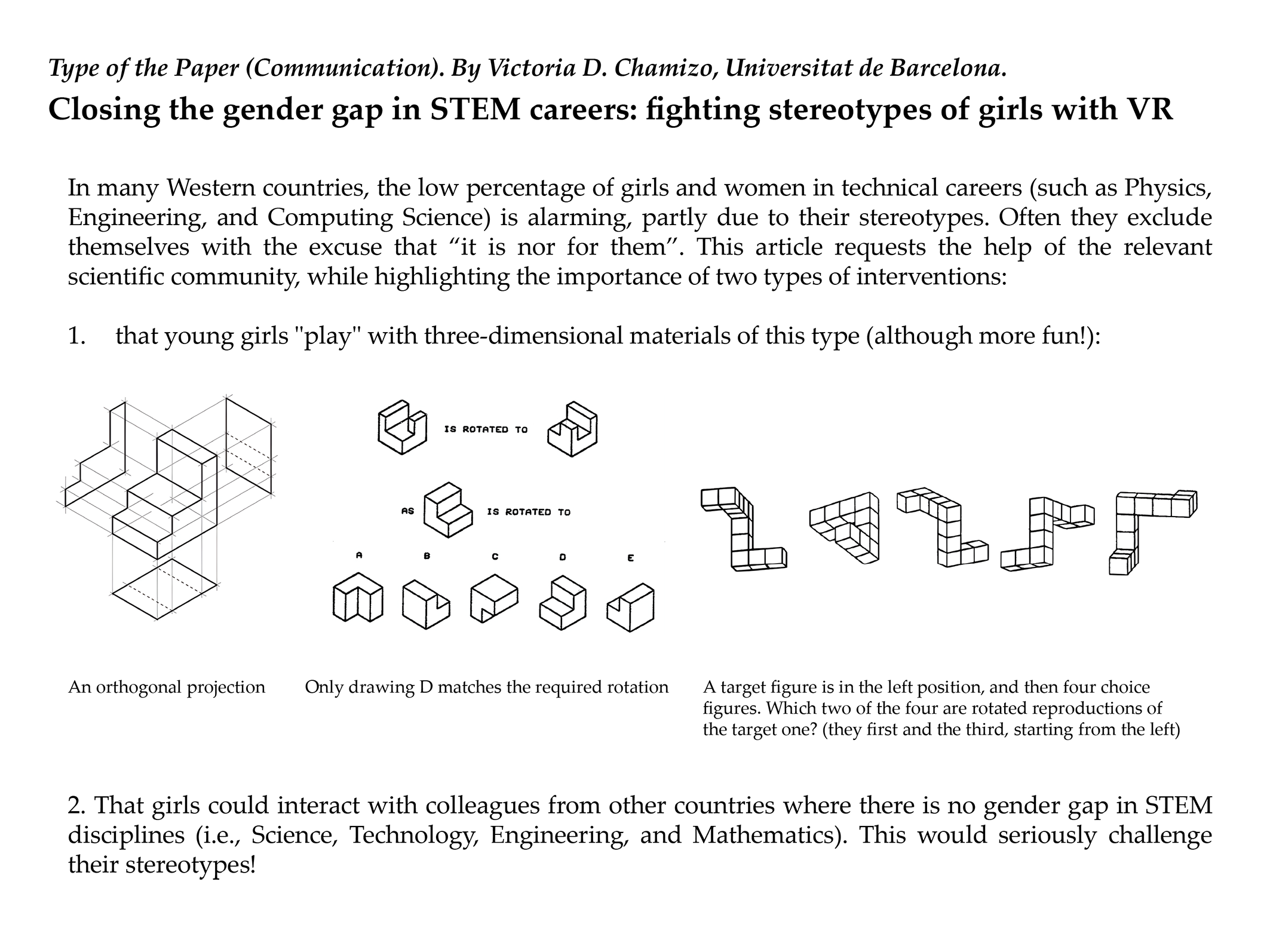

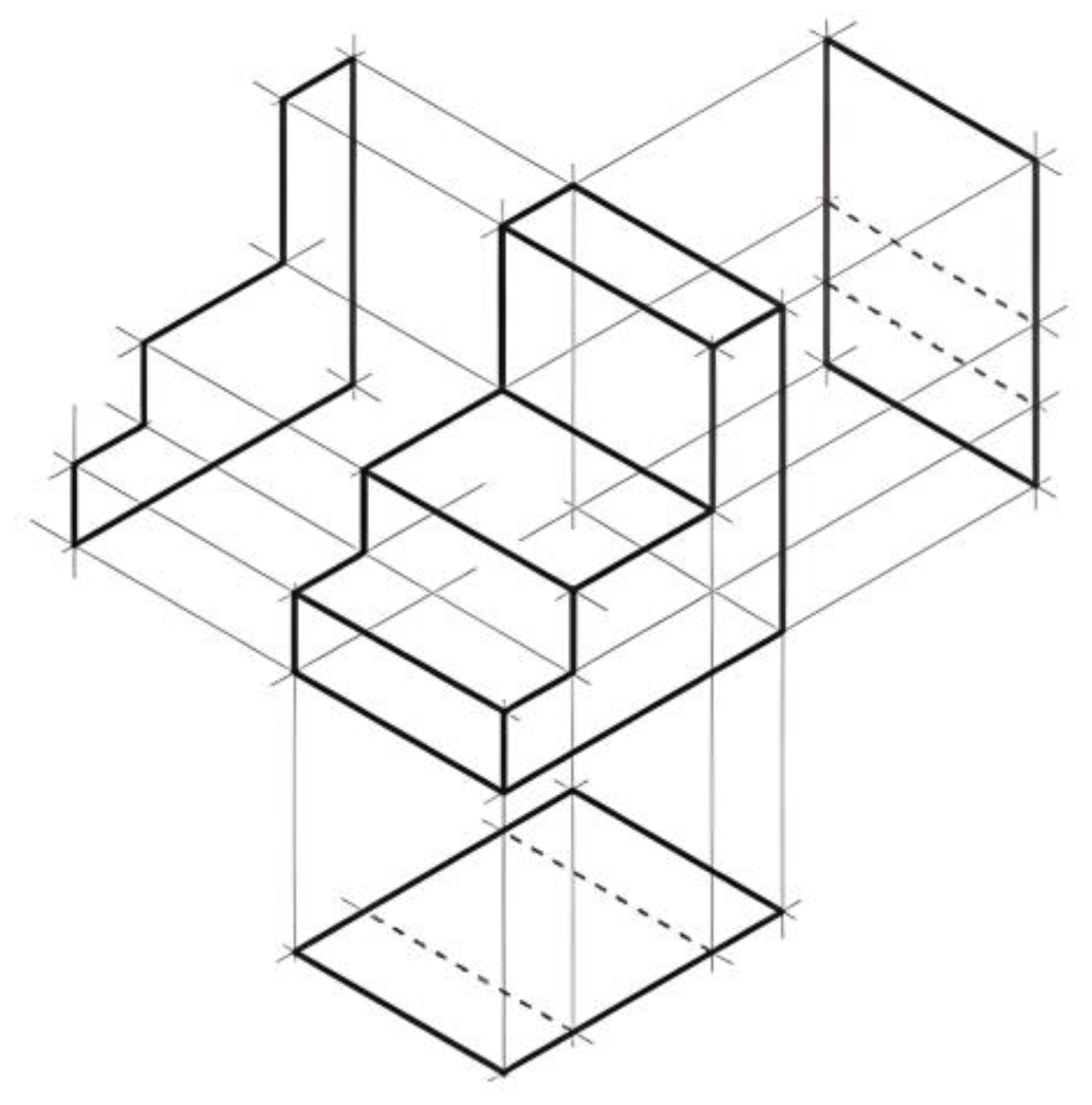

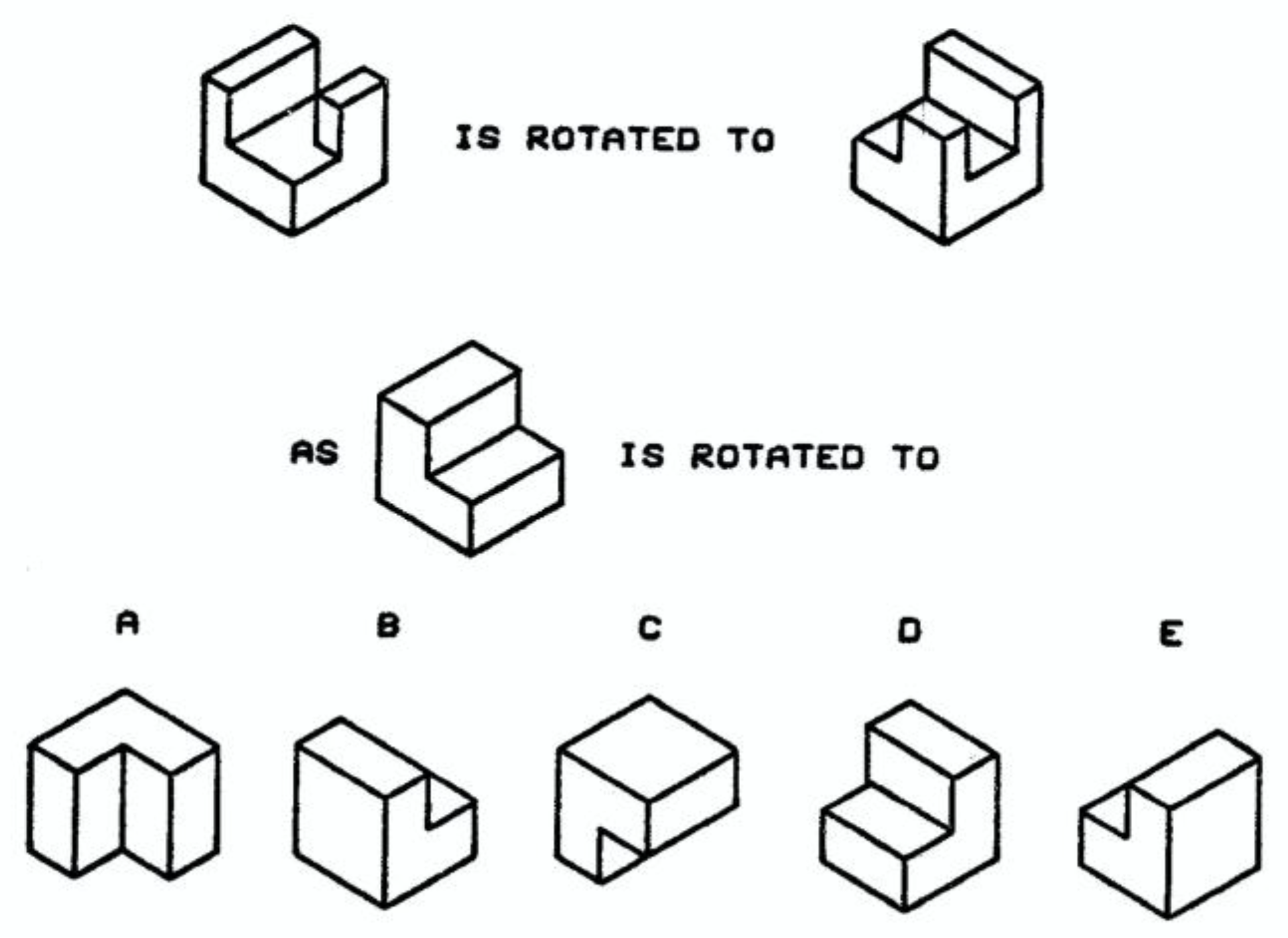

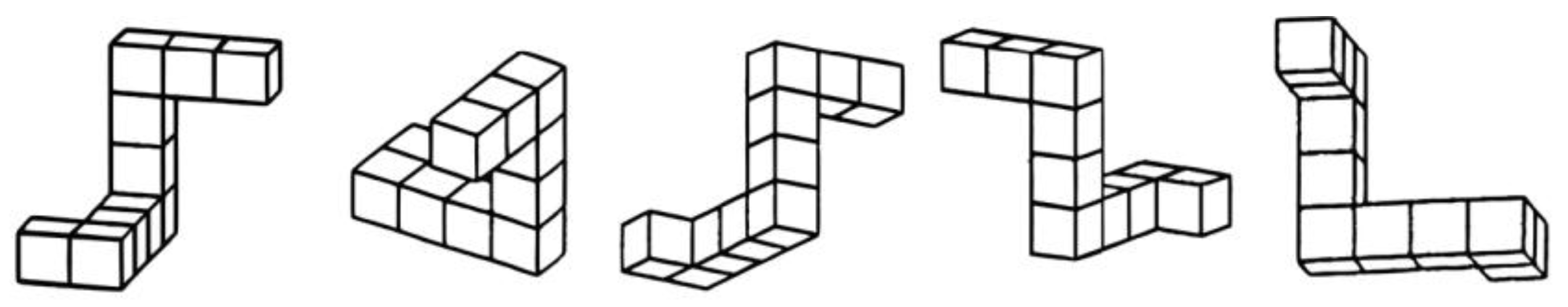

11 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction: The Current Situation

2. The Importance of Expert Testimony

3. Spatial Abilities and Mental Rotation Tests

4. Fighting STEM Stereotypes in Adolescence

5. Could New Technologies Close Stereotypes and the Gender Gap in STEM Careers?

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reilly, D.; Neumann, D.L.; Andrews, G. Investigating Gender Differences in Mathematics and Science: Results from the 2011 Trends in Mathematics and Science Survey. Res. Sci. Educ. 2019, 49, 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, D. Gender differences in educational achievement and learning outcomes. In International Encyclopedia of Education, 4th ed.; Robert J. Tierney, Fazal Rizvi, Kadriye Ercikan, Eds.; Elsevier Science, 2023; Vol. 6, pp. 399-408. [CrossRef]

- Wai, J. , Lubinski, D.; Benbow, C.P. Spatial ability for STEM domains: Aligning over 50 years of cumulative psychological knowledge solidifies its importance. J. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 101, 817–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, D.L.; Lubinski, D.; Benbow, C.P. Importance of Assessing Spatial Ability in Intellectually Talented Young Adolescents: A 20-Year Longitudinal Study. J. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 93, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uttal, D.H.; Meadow, N.G.; Tipton, E.; Hand, L.L.; Alden, A.R.; Warren, C.; Newcombe, N.S. The Malleability of Spatial Skills: A Meta-Analysis of Training Studies. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 352–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD, PISA 2012 Results: What Students Know and Can Do –Student Performance in Mathematics, Reading and Science. PISA OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2014; Volume I. [CrossRef]

- OECD, PISA 2022 Results: The State of Learning and Equity in Education. PISA OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023; Volume I. [CrossRef]

- Cheryan, S.; Ziegler, S.A.; Montoya, A.K.; Jiang, L. Why Are Some STEM Fields More Gender Balanced than Others? Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, R.; Rounds, J. All STEM fields are not created equal: People and things interests explain gender disparities across STEM fields. Front. Psychol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, D. Sex and cognition. The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [CrossRef]

- Mackintosh, N.J. IQ and human intelligence. Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011 (2nd ed). ISBN: 9780199585595.

- National Research Council. Learning to Think Spatially. The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Bokhove, C.; Redhead, E.S. Building digital cube houses to improve mental rotation skills. IJMEST 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarracín, L.; Hernàndez-Sabaté, A.; Gorgorió, N. Designing levels of a video game to promote spatial thinking. IJMEST 2021, 53, 3138–3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shadiev, R.A. Review of empirical research on game-based digital citizenship education. Educ Inf Technol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haier, R.J.; Karama, S. , Leyba, L.; Jung, R.E. MRI assessment of cortical thickness and functional activity changes in adolescent girls following three months of practice on a visual-spatial task. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terlecki, M.S.; Newcombe, N.S.; Little, M. Durable and Generalized Effects of Spatial Experience on Mental Rotation: Gender Differences in Growth Patterns. Applied Cognitive Psychology 2008, 22, 996–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherney, I.D. Mom, let me play more computer games: They improve my mental rotation skills. Sex Roles, 2008, 59, 776–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Spence, I.; Pratt, J. Playing an action video game reduces gender differences in spatial cognition. Psychological Science 2007, 18, 850–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawes, Z.; Moss, J.; Caswell, B.; Poliszczuk, D. Effects of mental rotation training on children’s spatial and mathematics performance: A randomized controlled study. Trends in Neuroscience and Education 2015, 4, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.; Bell, M. Sex differences on a computerized mental rotation task disappear with computer familiarization. Perceptual and Motor Skills 2000, 91, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Song, Y.; Liu, J. The Development of Spatial Cognition and Its Malleability Assessed in Mass Population via a Mobile Game. Psychological Science 2023, 34, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawietz, C.; Muehlbauer, T. Effects of Physical Exercise Interventions on Spatial Orientation in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Scoping Review. Front. Sports Act. Living 2021, 3, 664640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, P.; Richter, S. Effects of a one-hour creative dance training on mental rotation performance in primary school aged children. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2015, 13, 49–57. e-ISSN: 1694-2116.

- Jansen, P.; Kellner, J.; Rieder, C. The Improvement of Mental Rotation Performance in Second Graders after Creative Dance Training. Creative Education 2013, 4, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tank, K.M.; et al. Engineering in early elementary classrooms through the integration of high-quality Literature, design, and STEM+C content. In Early Engineering Learning, Early Mathematics Learning and Development, L. English; T. Moore, Eds., Springer: Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 2024; pp. 175–201. [CrossRef]

- Georges, C.; Cornu, V.; Schiltz, C. The importance of spatial language for early numerical development in preschool: Going beyond verbal number skills. PLoS One 2023, 29; 18(9), e0292291. [CrossRef]

- WHO, “Guidelines on physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep for children under 5 years of age”, 2019. ISBN: 9789241550536, available in https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550536.

- Figueiredo, M.; Mafalda, R.; Kamensky, A. Virtual Reality as an Educational Tool for Elementary School. In Proceedings of IDEAS 2019, L. Pereira; J. Carvalho; P. Krus; M. Klofsten; V. De Negri, Eds.; Springer Nature, 2021; Volume 198, pp. 261-267. [CrossRef]

- Supli, A.A.; Yan, X. Exploring the effectiveness of augmented reality in enhancing spatial reasoning skills: A study on mental rotation, spatial orientation, and spatial visualization in primary school students. Educ Inf Technol 2024, 29, 351–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walstra, K.A.; Cronje, J.; Vandeyar, T. A Review of Virtual Reality from Primary School Teachers’ Perspectives. EJEL 2023, 22, 01–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Escribá, D.; Pérez Gómez, C.; Puchol Forés, B., Coor. Matildes. Les grans oblidades de la història de la ciència (Matildes. The great forgotten in the history of science). Xarrad/Aps Llibres: Valencia, Spain, 2025. ISBN: 978-84-9133-757-7.

- Miller, D.; Lauer, J.E.; Tanenbaum, C.; Burr, L. The development of children’s gender stereotypes about STEM and verbal abilities: A preregistered meta-analytic review of 98 studies. Psychol. Bull. 2024, 150, 1363–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattila P. Geometry of Sets and Measures in Euclidean Spaces: Fractals and Rectifiability. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. ISBN 0 521 46576 1.

- English, L.; Moore. T., Eds. Early Engineering Learning, Early Mathematics Learning and Development; Springer: Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 2020. ISBN 978-981-10-8620-5.

- Bufasi, E.; Lin, T.J.; Benedicic, U.; Westerhof, M.; Mishra, R.; Namsone, D.; Dudareva, I.; Sorby, S.; Gumaelius, L.; Klapwijk, R.M.; Spandaw, J.; Bowe, B.; O’Kane, C.; Duffy, G.; Pagkratidou, M.; Buckley, J. Addressing the complexity of spatial teaching: a narrative review of barriers and enablers. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1306189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorby, S.; Veurink, N.; Streiner, S. Does spatial skills instruction improve STEM outcomes? The answer is ‘yes’. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2018, 67, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, D.; Sorby, S. Bridging the gap: blending spatial skills instruction into a technology teacher preparation programme. Int J Technol Des Ed. 2022, 32, 2195–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorby, S. A. Educational research in developing 3-d spatial skills for engineering students. IJSE(A) 2009, 31, 459–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorby, S. A.; Baartmans, B. J. The Development and Assessment of a Course for Enhancing the 3-D Spatial Visualization Skills of First Year Engineering Students. JEE 2020, 89, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, G.; Buckley, J; Sorby, S. Editorial: Spatial ability in STEM learning. Front. Educ. 2025, 10, 1602013. [CrossRef]

- Uttal, D.H.; McKee, K.; Simms, N.; Hegarty, M.; Newcombe, N.S. How Can We Best Assess Spatial Skills? Practical and Conceptual Challenges. Journal of Intelligence 2024, 12: 8. [CrossRef]

- Voyer, D.; Voyer, S.; Bryden, M.P. Magnitude of sex differences in spatial abilities: A meta-analysis and consideration of critical variables. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 250–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khine, M.S., Ed. Visual-spatial Ability in STEM Education. Transforming Research into Practice. Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland AG, 2017. ISBN 978-3-319-44385-0.

- Castro-Alonso, J.C., Ed. Visuospatial Processing for Education in Health and Natural Sciences. Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland AG, 2019. ISBN 978-3-030-20968-1.

- Ishikawa, T.; Newcombe. N.S. Why spatial is special in education, learning, and everyday activities. Cogn Res Princ Implic. 2021, 23, 6, 20. [CrossRef]

- Chamizo, V.D.; Bourdin, P.; Mendez-Lopez, M.; Santamaria, J.J. Editorial: From paper and pencil tasks to virtual reality interventions: improving spatial abilities in girls and women. Front. Virtual Real. 2023, 4, 1286689. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frvir.2023.1286689/full. [CrossRef]

- Piccardi, L.; Nori, R; Cimadevilla, J.M.; Kozhevnikov, M. The Contribution of Internal and External Factors to Human Spatial Navigation. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 585. [CrossRef]

- Reilly, D.; Hurem, A. Designing equitable STEM education: guidelines for parents, educators, and policy-makers to reduce gender/racial achievement gaps. International Encyclopedia of Education, 4th edition. Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2023; pp. 334-343. [CrossRef]

- Shepard, R.N.; Metzler, J. Mental Rotation of Three-Dimensional Objects. Science 1971, 171, 701–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guay, R. Purdue Spatial Visualization Test; Purdue Research Foundation: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg, S.G.; Kuse, A.R. Mental Rotations, a Group Test of Three-Dimensional Spatial Visualization. Percept. Mot. Skills 1978, 47, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.P.; Moore, D.S. Spatial Thinking in Infancy: Origins and Development of Mental Rotation between 3 and 10 Months of Age. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2020, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegarty, M. Ability and Sex Differences in Spatial Thinking: What Does the Mental Rotation Test Really Measure? Psychon. Rev. 2018, 25, 1212–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voyer, D.; Saint-Aubin, J.; Altman, K.; Doyle, R.A. Sex Differences in Tests of Mental Rotation: Direct Manipulation of Strategies With Eye-Tracking. J Exp Psychol Human 2020, 46, 871–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, M. L.; Meredith, T.; Gray, M. Sex differences in mental rotation ability are a consequence of procedure and artificiality of stimuli. Evolutionary Psychological Science 2018, 4, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNea, M.; Cole, R.; Tanner, D.; Lane, D. Cognitive Perspectives on Perceived Spatial Ability in STEM. In Spatial Cognition XIII. Spatial Cognition 2024. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; M. Živković; J. Buckley; M. Pagkratidou; G. Duffy, Eds; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 14756, pp 66–78. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, K.A.; Camba, J.D. Gender differences in spatial ability: A critical review. Educational Psychology Review 2023, 35, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L.; Silverberg, S. B. The vicissitudes of autonomy in early adolescence. Child Development 1986, 57, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bueno, D. El cerebro del adolescente, 3rd ed. [The adolescent brain]. Grijalbo: Barcelona, Spain, 2022. ISBN: 978-84-253-6135-7.

- Brown, B.B.; Bakken, J.P.; Ameringer, S.W.; Mahon, S.D. A comprehensive conceptualization of the peer influence process in adolescence. In Understanding peer influence in children and adolescence; M. J. Prinstein; K. A. Dodge, eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, US, 2008, pp. 17–44. ISBN: 978-1-59385-397-6.

- Dishion, T.J.; Tipsord, J.M. Peer contagion in child and adolescent social and emotional development. Annu Rev Psychol. 2011, 62, 189–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R.L. Age, sex, and task difficulty as predictors of social conformity. J Gerontol. 1972, 27, 229–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekinbaş, K.S.; Madison, E.T.; Adame, A.; Schueller, S.M.; Khan, F.R. Youth, Mental Health, and the Metaverse: Reviewing the Literature. Connected Learning Alliance: Irvine, CA, US, 2023. https://clalliance.org/publications/youth-mental-health-and-the-metaverse-reviewing-the-literature.

- Pasupathi, M. Age differences in response to conformity pressure for emotional and nonemotional material. Psychology and Aging 1999, 14, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvers, J.A.; McRae, K.; Gabrieli, J.D.; Gross, J.J.; Remy, K.A.; Ochsner, K.N. Age-related differences in emotional reactivity, regulation, and rejection sensitivity in adolescence. Emotion 2012, 12, 1235-47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eagly, A.H.; Koenig, A.M. The vicious cycle linking stereotypes and social roles. Current Directions 2021, 30, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacoviello, V.; Valsecchi, G.; Vétois, M.; et al. Reducing the gender gap on adolescents’ interest in study fields: The impact of perceived changes in ingroup gender norms and gender prototypicality. Soc Psychol Educ 2024, 27, 1043–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telzer, E.H.; Dai, J.; Capella, J.J.; Sobrino, M.; Garrett, S.L. Challenging stereotypes of teens: Reframing adolescence as window of opportunity. Am Psychol. 2022, 77, 1067–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Y. Stereotypes of adolescence: Cultural differences, consequences, and intervention. Child Dev. Perspect. 2023, 17, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Ren, K.; Newcombe, N.S.; Weinraub, M.; Vandell, D.L.; Gunderson, E.A. Tracing the origins of the STEM gender gap: The contribution of childhood spatial skills. Dev Sci. 2023, 26, e13302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, M.; Majewski, H.M.; Qazi, M.; Rawajfih, Y. Self-efficacy in STEM. In International Encyclopedia of Education, 4th ed.; Robert J. Tierney, Fazal Rizvi, Kadriye Ercikan, Eds.; Elsevier Science, 2023, pp. 388-394. ISBN 9780128186299. [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Rounds, J.; Armstrong, P. I. Men and things, women and people: a meta-analysis of sex differences in interests. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 135, 859–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, R.; Rounds, J. All STEM Fields are Not Created Equal: People and Things Interests Explain Gender Disparities Across STEM Fields. In The underrepresentation of women in science: International and Cross-Disciplinary Evidence and Debate; Frontiers Media: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Valtorta, R.R.; Baldissarri, C.; Raguso, G.; D’Ecclesiis, G.; Volpato, C. Gender stereotypes and sexualization in Italian children’s television advertisements. Sexuality & Culture 2023, 27, 1625–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, C.; Rush, E. “Why does all the girls have to buy pink stuff?” the ethics and science of the gendered toy marketing debate. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 769–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, L.; Leslie, S-J.; Cimpian, A. Gender stereotypes about intelectual ability emerge early and influence children’s interests. Science 2017, 355, 389–391. [CrossRef]

- Moè, A. Mental rotation and mathematics: Gender-stereotyped beliefs and relationships in primary school children. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2018, 61, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girelli, L. What does gender has to do with math? Complex questions require complex answers. J Neurosci Res. 2023, 101, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lennon-Maslin, M.; Quaiser-Pohl, C.; Wickord, L-C. Beyond numbers: the role of mathematics self-concept and spatial anxiety in shaping mental rotation performance and STEM preferences in primary education. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1300598. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Zhang, Y.; Alterman, V.; Zhang, B.; Yu, G. Can math-gender stereotypes be reduced? A theory-based intervention program with adolescent girls. Curr. Psychol. 2018, 37, 612–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinner, L.; Tenenbaum, H. R.; Cameron, L.; Wallinheimo, A-S. A school-based intervention to reduce gender-stereotyping. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2021, 42, 422-449. [CrossRef]

- Cyr, E.N.; Kroeper, K.M.; Bergsieker, H.B.; Dennehy, T.C.; Logel, C.; et al. Girls are good at STEM: Opening minds and providing evidence reduces boys’ stereotyping of girls’ STEM ability. Child Dev. 2024, 95, 636–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvert, S.L.; Putnam, M.M.; Aguiar, N.R.; Ryan, R.M.; Wright, C.A.; Liu, Y.H.A.; Barba, E. Young Children’s Mathematical Learning From Intelligent Characters. Child Dev. 2020, 91, 1491–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvert, J.; Hume, M. Improving student learning outcomes using narrative virtual reality as pre-training. Virtual Reality 2023, 27, 2633–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. Talking with machines: Can conversational technologies serve as children’s social partners? SRCD 2023, 17, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D.; Xie, H.; Kohnke, L. Navigating the Future: Establishing a Framework for Educators’ Pedagogic Artificial Intelligence Competence. EJED 2025, 60, e70117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, M.; Sanchez-Vives, M.V. Enhancing Our Lives with Immersive Virtual Reality. Front. Robot. AI 2016, 3. [CrossRef]

- Marougkas, A.; Troussas, C.; Krouska, A.; et al. How personalized and effective is immersive virtual reality in education? A systematic literature review for the last decade. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 18185–18233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsop, T. (2024) Virtual reality (VR) headset average price in the United States from 2018 to 2028. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/forecasts/1338404/vr-headset-average-price-united-states.

- Kumar, L.; Tanveer, Q.; Kumar, V.; Javaid, M.; Haleem, A. Developing low cost 3 D printer. Int. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Res. 2016, 5, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendón-Medina, M.A.; Andrade-Delgado, L.; Telich-Tarriba, J.E.; Fuente-Del-Campo, A.; Altamirano-Arcos, C.A. Dimensional Error in Rapid Prototyping with Open Source Software and Low-cost 3D-printer. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018, 25, 6, e1646. [CrossRef]

- Lundin, R.M.; Yeap, Y.; Menkes, D.B. Adverse effects of virtual and augmented reality interventions in psychiatry: systematic review, JMIR Ment. Health 2023, 10, e43240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Marín, D.A. Review of the Practical Applications of Pedagogic Conversational Agents to Be Used in School and University Classrooms. Digital 2021, 1, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon-Jones, E.; Mills, J. An introduction to cognitive dissonance theory and an overview of current perspectives on the theory. In Cognitive dissonance: Reexamining a pivotal theory in psychology, 2nd ed.; E. Harmon-Jones, Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, US, 2019, pp. 3–24. [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, S.; Blum-Ross, A. Parents’ Role in Supporting, Brokering or Impeding Their Children’s Connected Learning and Media Literacy. Cultural Science Journal 2019, 11, pp. 68–77. [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Zhang, Y.B. Warranting theory, stereotypes, and intercultural communication: US Americans’ perceptions of a target Chinese on Facebook. IJIR 2020, 77, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ip, H.H.S.; Wong, Y.M.; Lam, W. S. An empirical study on using virtual reality for enhancing the youth’s intercultural sensitivity in Hong Kong. JCAL 2020, 36, 625–635. https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/jcal.12432. [CrossRef]

- Shadiev, R.; Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Gayevskaya, E.; Borisov, N. Research on the impact of the learning activity supported by 360-degree video and translation technologies on cross-cultural knowledge and attitudes development. Educ Inf Technol 2024, 29, 7759–7791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadiev, R.; Chen, X.; Reynolds, B.L.; Song, Y.; Altinay, F. Facilitating cognitive development and addressing stereotypes with a cross-cultural learning activity supported by interactive 360-degree video technology. BJET 2024, 55, 2668–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadiev, R.; Dang, C.; Sintawati, W.; Yi, S.; Huang, Y. M. Facilitating information literacy and intercultural competence development through the VR Tour production learning activity. ETR&D 2023, 71, 2507–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Shadiev, R.; Li, C. College students’ use behavior of generative AI and its influencing factors under the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology model. Educ Inf Technol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, H.C.; Tseng, S.S.; Heng, L. Enhancing EFL students’ intracultural learning through virtual reality. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 30, 1609–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, D. F. Sex differences in cognitive abilities, 4ª ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum: NJ, US. 2012. ISBN 978-I-84872-940-7.

- Chamizo, V.D.; Rodrigo, T. Spatial orientation. In Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior; J. Vonk, T. K. Shackelford, Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland AG. [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, N.; et al. The malleable brain: plasticity of neural circuits and behavior - a review from students to students. J Neurochem. 2017, 142, 790–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweatt, J.D. Neural plasticity and behavior - sixty years of conceptual advances. J Neurochem. 2016, 139, 2, 179-199. [CrossRef]

- Cantor, P.; Osher, D.; Berg, J.; Steyer,; L. Rose, T. Malleability, plasticity, and individuality: How children learn and develop in context. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2019, 23, 307-337. [CrossRef]

- Laube, C.; van den Bos, W.; Fandakova, Y. The relationship between pubertal hormones and brain plasticity: Implications for cognitive training in adolescence. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2020, 42, 100753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Singh, M. Sex differences in cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neuroendocrynol. 2014, 35, 3, 385-403. [CrossRef]

- Bourzac, K. Why women experience Alzheimer’s disease differently from men. Nature 2025, 640, S14–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moutinho, S. Women twice as likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease as men —but scientists do not know why. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 704–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramaniapillai, S.; Almey, A.; Rajah, M. N.; Einstein, G. Sex and gender differences in cognitive and brain reserve: Implications for Alzheimer’s disease in women. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2021, 60, 100879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahmani, L.; Bohbot, V.D. Dissociable contributions of the prefrontal cortex to hippocampus- and caudate nucleus-dependent virtual navigation strategies. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2015, 117, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sodums, D.J.; Bohbot, V.D. Negative correlation between grey matter in the hippocampus and caudate nucleus in healthy aging. Hippocampus 2020, 30, 892–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmani, L.; Idriss, M.; Konishi, K.; West, G.L.; Bohbot, V.D. Considering environmental factors, navigation strategies, and age. Front. Virtual Real. 2023, 4, 1166364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnamnia, N.; Kamsin, A.; Hayati, S. Impact of Digital Game-Based Learning on STEM education in Primary Schools: A meta-analysis of learning approaches. Innoeduca 2024, 10, 113–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.H.; Chen, B.; Hwang, G.J.; Guan, J.Q.; Wang, Y.Q. Effects of digital game-based STEM education on students’ learning achievement: a meta-analysis. IJ STEM Ed. 2022, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).